Abstract

Objective:

To assess the pharmacokinetics (PK) of levonorgestrel after 1.5 mg oral doses (LNGEC) in women with normal, obese and extremely obese body mass index (BMI).

Study Design:

The 1.5 mg LNG dose was given to healthy, reproductive-age, ovulatory women with normal BMI (mean 22.0), obese (mean 34.4), and extremely obese (mean 46.6 kg/m2) BMI. Total serum LNG was measured over 0 to 96 hours by radioimmunoassay while free and bioavailable LNG were calculated. The maximum concentration (Cmax), time to maximum concentration (Tmax), and area under the curve (AUC) of LNG were assessed. Pharmacokinetic parameters calculated included half-life (t1/2), clearance (CL) and volume of distribution (Vss).

Results:

Ten normal-BMI, 11 obese-BMI, 5 extremely obese-BMI women were studied. After LNG-EC, mean total LNG metrics were lower in the obese and extremely obese groups compared to normal (Cmax 10.5 and 10.5 versus 16.2 ng/mL, both p <.01; AUC 208 and 197 versus 360 h× ng/mL, both p<.05). Mean bioavailable LNG Cmax was lower in obese (7.03 ng/mL, p<.05) and extremely obese (7.53 ng/ml, p=0.198) compared to normal BMI (9.39 ng/mL). Mean bioavailable LNG AUC values were lower in obese and extremely obese compared to normal (131.6 and 127.5 vs 185.0 h×ng/mL, p<.05 for both).

Conclusions:

Obese and extremely obese women were exposed to lower total and bioavailable LNG than normal BMI women.

Implications:

Lower ‘bioavailable’ (free plus albumin bound) LNG AUC in obese women may play a role in the purported reduced efficacy of LNG-EC in obese users.

Keywords: levonorgestrel, emergency contraception, obesity, pharmacokinetics, BMI, BAI

1. Introduction

Obesity has been identified as a risk factor for emergency contraceptive (EC) failure. Pooled analyses of prior randomized controlled studies designed to assess levonorgestrel (LNG) efficacy have shown a decrease in efficacy of LNG-EC with increasing body weight and body mass index (BMI)[1–3]. Gemzell-Danielsson contended that there was no evidence to support the hypothesis of loss of EC efficacy in subjects with high BMI or bodyweights [4].

Two studies have examined the pharmacokinetics of 1.5 mg doses of LNG in relation to obesity. Praditpan et al assessed the PK of 1.5 mg doses of LNG in 16 normal and 16 obese women and found that the Cmax and AUC of LNG were nearly half the normal values in the obese women [5]. Calculated values of free LNG were also lower. Edelman et al found similar differences for Cmax in obesity, but a curtailed PK sampling over 2.5 h was performed and thus other PK parameters could not be calculated [6]. While the FDA has numerous Guidances that provide advice on performing PK and PD studies in subjects with altered physiology, there is no Guidance for obesity and thus no indication of what changes in PK and efficacy would be clinically important.

We assessed the pharmacokinetics of levonorgestrel (LNG) after 1.5 mg oral doses in women with normal, obese and extremely obese BMI using comprehensive pharmacometric methodology. The primary objective was to compare various exposure metrics and PK parameters of LNG in relation to BMI. Our hypothesis is obese BMI users of LNG-EC have PK profiles that are consistent with reduced plasma protein binding of LNG and that these alterations affect the primary mechanism of action of LNG-EC, which is inhibition of ovulation.

Methods

Study Subjects

A prospective cohort study was conducted at the University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles, CA, from March 2013 to May 2016 after IRB approval with listing in ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT02104609). We enrolled English- and Spanish-speaking women aged 18–35 years with regular menstrual cycles (24–35 days) and with either normal (BMI 18.5–24.9 kg/m2), obese (BMI = 30–39.9 kg/m2), or extremely obese (BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2) BMIs. Women were excluded if they were seeking pregnancy, using hormonal contraception, smokers, taking medication that might interact with LNG-EC (http://drug-interactions.medicine.iu.edu), or had pre-existing renal or liver disease and thyroid, pituitary, adrenal or ovarian disorders.

We scheduled a screening visit during the mid-luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, and obtained informed consent. Subject height, weight, and hip circumference were measured while wearing nonrestrictive undergarments, and calculated BMI. The scale was regularly maintained by our hospital’s biomedical engineering department. A comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) and mid-luteal progesterone (P4) serum sample were obtained. The participant was enrolled into the study if the CMP did not indicate evidence of renal or liver disease and if the mid-luteal P4 was > 3 ng/ml, an indication of presumptive ovulation.

On day 8 (+/− 1 d) of the menstrual cycle, participants presented to the USC Clinical Trials Unit after an overnight fast for venous catheter placement. A single dose of levonorgestrel 1.5 mg (Plan B One Step™, Teva, North Wales; Next Choice One Dose™, Activis Pharma, Parsippany, NJ, USA) was given with 200 mL water at time 0, before venous sampling. Blood samples were drawn at 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16 hours. The catheter was removed and participants returned at 24, 48, 72, and 96 hours for additional blood. Albumin and SHBG were measured at time 0, 24, 48, 72, 96 hours.

The body size measurements used were total body weight (BW), body adiposity index (BAI, [7]), body surface area (BSA, [8]), and body mass index (BMI, [9]) according to:

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

Sample Size

The difference in LNG concentration between normal and obese subjects observed by Edelman et al [10] was 0.6 ng/ml. However, with three groups planned, a more conservative difference was used. We expected 80% power to detect a difference of 0.36 ng/ml in LNG Cmax within the three groups assuming an alpha level of 0.05 and 10 subjects per group.

Bioanalytical Methods

Serum LNG was quantified in serum by a specific and sensitive radioimmunoassay (RIA) [10, 11]. Prior to RIA, LNG was extracted with hexane:ethyl acetate (3:2) to remove potential interfering conjugated steroids. Highly specific antisera was used in conjunction with an iodinated radioligand. Separation of free from antiserum-bound LNG was achieved by use of a second antibody. The sensitivity of the LNG RIA is 0.05 ng/mL. Intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation (CV%) were 4.4% and 8.9%.

Serum SHBG and progesterone were measured by a solid-phase, two-site chemiluminescent immunometric assay on the Immulite analyzer (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Deerfield, IL). The analytical sensitivity for SHBG was 0.02 nmol/L and inter-assay CV% was <8%. Assay sensitivity for progesterone was 0.1 ng/ml and inter-assay CV% was <11%.

Calculation of Free and Bioavailable LNG Concentrations

The measured concentrations of sex hormone binding globulin (SHBG) and albumin (Alb) in each subject and each time were used to calculate the free and bioavailable LNG concentrations for the measured LNG concentrations using the Vermeulen method as described in the Supplemental Materials [12–14].

Pharmacokinetics

Noncompartmental Analysis (NCA) was used for assessment of the serum LNG concentration versus time profiles. The individual maximum concentration (Cmax) and the time to Cmax (Tmax) were observed values. The area under the concentration versus time curve (AUC), half-life (t1/2), clearance (), mean residence time (MRT), and volume of distribution at steady-state () were obtained using the Phoenix WinNonlin version 7.0 (Certara - Pharsight, St. Louis, MO). The linear-up log-down method was used for AUC values with extrapolations based on terminal half-lives. The software R was applied for ANOVA if the data were parametric; otherwise the Kruskal-Wallis method was used to assess differences between weight groups. The Tukey test was used for pairwise assessments following ANOVA and the Dunn test was used after Kruskal-Wallis analyses.

2. Results

The demographic characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants by BMI group

| Normal BMI (n=10) | Obese BMI (n=11) | Extremely obese BMI (n=5) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 26.3 (18.0–34.0) | 24.4 (18.0–31.0) | 30.0 (23.0–34.0) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic | 2 (20%) | 7 (63.6%) | 2 (40%) |

| African-American | 3 (30%) | 4 (36.4%) | 3 (60%) |

| Asian | 3 (30%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Caucasian | 2 (20%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Weight (kg) | 54.9 (45.6–61.7) | 93.0 (81.8–108.6) | 120.7 (103.6–151.3) |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) (kg/m2) | 22.0 (18.5–24.9) | 34.4 (30.0–37.2) | 46.6 (40.5–55.2) |

| Hip circumference (cm) | 89.60 (82.00–96.00) | 116.7 (107.5–124.0) | 141.6 (135.0–158.5) |

| Body Adiposity Index (BAI) (%) | 27.2 (19.6–31.1) | 37.5 (33.2–44.3) | 51.6 (42.4–57.0) |

| Body Surface Area (BSA) (m2) | 1.55 (1.37–1.65) | 1.99 (1.79–2.19) | 2.19 (1.97–2.46) |

Normal BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), obese BMI (30–39.9 kg/m2), extremely obese BMI (≥ 40 kg/m2)

Values are reported as mean and total range

Ethnicity is self-reported, presented as n(%)

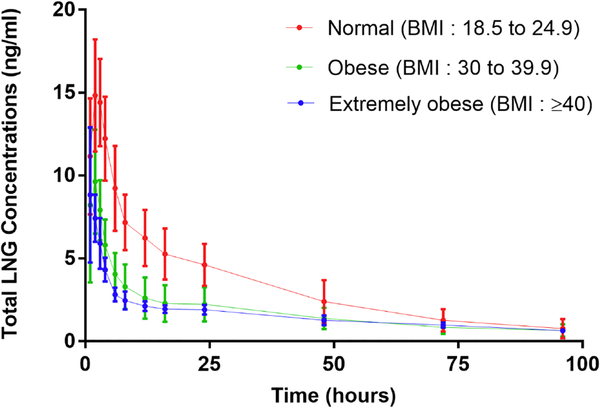

Figure 1 provides the mean concentrations of total LNG versus time for the three groups of women who received 1.5 mg tablets. Serum LNG concentrations are consistently higher in the women of normal BMI and lowest in the extremely obese group. Absorption occurred rapidly producing a sharp peak at about 2 hours followed by a biexponential decline with a long terminal half-life typically averaging 30 to 46 hours over the 96-hour sampling period.

Figure 1.

Mean Concentration-time profiles of LNG for in all BMI groups.

The descriptive and NCA pharmacokinetic parameters for both total and free LNG are shown in Figure 2 for the three groups. The arithmetic mean (SD) values of PK parameters are listed in Table 2. Both arithmetic and geometric means were calculated and were very similar (not shown). For total LNG, the Cmax in both obese groups were significantly lower than in normal as can also be seen in Figures 1 and 2. The AUC values were also lower in the obese groups when compared to normal. However, these exposure parameters as calculated for free LNG were actually much closer in the three groups. The non-normalized Vss (in L) was significantly larger in the obese groups (405 and 466 vs. 162 L, both p<.0001) when calculated for total LNG and also much larger in the obese groups for free LNG. The half-life values were significantly longer for obese subjects when based on both total (41 and 46 vs. 30 h, NS and p<.05) and free LNG (59 and 70 vs 37 h, both p<.05). The MRT values differed similarly.

Figure 2.

Comparison of the noncompartmental pharmacokinetic parameters in the three groups. Horizontal bars depict statistical comparisons. (ns – not significant; *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001; ****p<0.0001; N: normal-weight, O: obese weight, E: extremely obese-weight)

Table 2.

Summary of Total and Free LNG PK parameters for each BMI group

| Parameters (units) | Normal BMI n=10 | Obese BMI n=11 | Extremely Obese BMI n=5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total LNG | |||

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 16.2 (2.8) | 10.5 (2.8) | 10.5 (1.9) |

| Tmax (h) | 2.5 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) |

| AUC (h×ng/mL) | 360.1 (109.3) | 208.1 (87.0) | 197.8 (26.5) |

| t1/2 (h) | 29.7 (10.6) | 41.0 (13.6) | 46.4 (6.6) |

| Vss (L) | 162.2 (54.6) | 404.7 (140.2) | 466.4 (39.6) |

| MRT (h) | 39.0 (13.4) | 52.5 (17.9) | 62.3 (9.6) |

| CL (L/h) | 4.48 (1.19) | 8.51 (3.71) | 7.70 (1.09) |

| Calculated Free LNG | |||

| Cmax (ng/mL) | 0.337 (0.079) | 0.255 (0.061) | 0.281 (0.084) |

| Tmax (h) | 2.5 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.0) | 1.0 (1.0–2.0) |

| AUC (h×ng/mL) | 8.07 (3.29) | 6.81 (2.92) | 6.51 (1.79) |

| t1/2 (h) | 36.8 (20.2) | 59.0 (22.3) | 69.6 (30.1) |

| Vss (L) | 8664 (2511) | 18013 (4907) | 20844 (4597) |

| MRT (h) | 49.0 (27.8) | 79.9 (32.3) | 94.1 (43.4) |

| CL (L/h) | 206.9 (64.6) | 258.9 (110.8) | 245.7 (71.7) |

Normal BMI (18.5–24.9 kg/m2), obese BMI (30–39.9 kg/m2), extremely obese BMI (≥ 40 kg/m2)

Pk parameters include maximum concentration (Cmax), the time to Cmax (Tmax), the area under the concentration versus time curve (AUC), half-life (t1/2), clearance (CL), mean residence time (MRT), and volume of distribution at steady-state (Vss)

Values are reported as arithmetic mean (SD); Tmax is reported at median (Q1-Q3)

Serum Protein Concentrations

The initial and day-4 SHBG and albumin concentrations are shown in Figure 3 in the three groups. At initial dosing, significantly lower concentrations of SHBG were found for extremely obese compared to normal-BMI individuals (27.6 vs. 55.4 nmol/L, p=0.037). Differences in SHBG were also seen at times 24, 48 and 72 h between the groups. The SHBG concentrations were similar for obese and extremely obese subjects.

Figure 3.

Changes is SHBG and albumin concentrations over time by BMI groups and corresponding changes in mean free and bioavailable LNG percentage and AUC in relation to BMI

The SHBG and albumin concentrations decreased after the dose of LNG. After 4 days, the mean decline from pre-LNG values of SHBG was 27.6% for normal weight, 30.8% for obese, and 25.9% for extremely obese subjects (with exclusion of one outlier who had an increase in SHBG) for subjects who had values on days 1 and 4. Corresponding changes for albumin were 35.2%, 34.5%, and 34.7%. Paired t-tests showed that the overall concentrations at 96 hours were lower than at 0 hours for SHBG (p = 0.0174) and albumin (p <0.001).

Use of the Vermeulen computational method, our measured concentrations of LNG, SHBG and albumin, and the assumptions about binding values for the two proteins yielded free fractions of LNG of about 2.10% in normal weight, 2.66% in obese, and 2.65% in extremely obese subjects. As shown in Figure 3, with the decrease of SHBG with body weight, there was an increase in the free fraction of LNG. The AUC of free LNG was fairly constant with weight, but the bioavailable AUC decreased significantly.

Additional comparisons of the individual PK parameters for total and free LNG for the three groups are shown in Figure 2. The increases (or lack thereof) in most parameters with body weights were confirmed. The values of CL differed for total LNG but were similar for free LNG in the three weight groups.

3. Discussion

Our study found serum concentration versus time profiles of total and bioavailable LNG with smaller Cmax and AUC values in women with BMI >30. However, the calculated free LNG Cmax and AUC were very close in the three groups. Interestingly, BMI did not impact the Tmax for total or free LNG. The larger Vss seen in the obese groups for both total and free LNG are consistent with the greater tissue mass for distribution of the drug. Accordingly, longer t1/2 and MRT values in these groups were observed as the larger distribution space results in longer retention of LNG in the obese women. Although CL was increased for total LNG, it was not affected for free LNG PK. The women with BMI >30 exhibited lower SHBG concentrations that accounted for differences in CL based on total versus free LNG.

For total LNG, a lower Cmax for obese subjects was also found by Edelman et al [6] and by Praditpan et al [5] where the same 1.5 mg dose of LNG was given. For free LNG, our Cmax was slightly lower in obese subjects (p = 0.0446), while Edelman et al showed no difference in relation to body weight. A lower AUC of total LNG was also reported in obese subjects by Praditpan et al [5] with sampling to 48 h, but the Edelman et al [6] study was limited to the time frame of 0 to 2.5 h. Edelman et al [6] included direct measurements of free LNG, which were greater in obese women owing to their lower SHBG concentrations with values in agreement with our calculations. The Praditpan and Edelman studies used LC/MS/MS for analyses, while our study employed a sensitive and specific RIA method.

Lower SHBG concentrations occur in obesity [6, 15]. Additionally, decreases in SHBG after LNG exposure are well-known [16, 17]. The mechanism of reduced SHBG with LNG is assumed to be decreased hepatic production. However, another factor may be internalization of the SHBG-LNG complex in target cells [18]. After implantation of LNG via Norplant there was a reduction of 19% in SHBG at day 3 and 60% at day 7 [16]. After placement of an intrauterine device containing LNG, there was an initial decline and then SHBG was stable over the ensuing 36-months [19]. With a single-dose of 1.5 mg LNG-EC, SHBG concentrations fell by 36% after 5 days [17]. Our findings were similar with about 30% decreases in both SHBG and albumin after 4 days. Kuhnz et al [20] also described reductions in SHBG during daily oral dosing of 0.15 mg LNG.

Both SHBG and albumin concentrations decreased in all LNG study groups (Figure 3). There appear to be no previous reports of changes in plasma albumin during use of LNG alone. While Amatayakul et al showed decreased albumin after OC use, the estrogen is a complication [21]. Kuhnz et al [20] originally described increases in free LNG during daily dosing with 0.15 mg and demonstrated the shared binding of LNG to both SHBG and albumin.

Several contraceptive progestins given by various routes of administration exhibit modestly (about 30%) lower total serum concentrations in obesity [22].

LNG has a low hepatic extraction ratio of 0.12–0.14 (Table I from Kuhnz [23]) indicating that, like most drugs, uptake and metabolism of the drug by the liver is likely governed by free drug in plasma. Thus, the free drug clearance primarily controls the exposure, or AUC, of free drug. However, metabolism of LNG by adipose tissue is possible as indicated by numerous genes for drug metabolizing enzymes found in fat [24, 25].

The changes in distribution kinetics of LNG in obesity are quite interesting. The logP of LNG is between 3.25 and 3.8, indicative of a moderately lipophilic drug. Nilsson et al [26] measured LNG in fat tissue and found a fat to plasma ratio of 7.9. Most lipophilic drugs are distributed preferentially into adipose tissue resulting in increased volumes of distribution [24]. Moreover, with the lower SHBG concentration and higher free fraction in obesity, LNG is readily able to diffuse out of blood. The increased tissue mass and access of free drug accounts for the much larger VT and Vss and longer half-life in the obese subjects. This behavior was similar for thiopental, which has a logP of about 3 [27]. Cardiac output [28] and blood flow to adipose tissue [29] also increase in obesity.

A variant of SHBG exists that decreases the affinity to testosterone causing an increase in the free fraction [30]. Perhaps the higher LNG clearances found for two individuals in this study was due to this factor. Studies of the PK of a larger number of obese women are needed to determine if these two subjects were either outliers or a subgroup with genetic differences.

The strengths of this study include the extensive LNG venous sampling which allowed for more accurate calculation of drug exposure. We included extremely obese women in whom we would expect the additional adipose tissue would induce greater distribution and metabolic changes.

There were some limitations in this study. Values of free LNG were obtained by calculation rather than measurement. However, our calculated values of free LNG for normal women are consistent with directly measured values previously published (Table S-1) and found recently by Edelman et al [6].

The bioavailability was assumed to be complete (F = 1) and similar in all groups. Studies of the PK of various drugs in obesity have not reported any problems with drug absorption [24].

How do these results relate to the concerns that use of 1.5 mg doses of LNG for EC may be less efficacious in obese women? There is no clear consensus on this issue [3, 4]. The interpretation of our findings is somewhat dependent on whether the “free hormone hypothesis” is relevant in relation to PK and efficacy. This hypothesis poses that only free drug in plasma is available for both clearance and uptake into tissues. There is support for this [14], but there are also cell and preclinical studies that suggest an uptake mechanism for the SHBGLNG complex into target cells via megalin [31]. If the free hormone hypothesis operates, then the similarities in free CL and free Cmax and AUC suggests that obese women should not have impaired contraception efficacy. However, recent considerations in regard to measuring total versus free testosterone have led to preference for the free ‘bioavailable’ hormone as the active moiety [14] that is available to target sites. Notably, we found that the AUC of ‘bioavailable’ (free plus albumin-bound) LNG is significantly lower in obese women (Figure 3). If target tissue uptake is controlled by the bioavailable LNG concentrations, this would explain the possible reduced efficacy of LNG in obese women. Our subsequent report will describe the ovulation rates and other clinical aspects of this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the University of Southern California Reproductive Research Clinic, Clinical Trials Unit and SC-CTSI project coordinators and staff, especially Angelica Mora, Blanca Ovalle and Emily Silverstein.

We thank Dr. Penina Segall-Gutierrez for her contribution to study design.

Funding Source: The Society of Family Planning funded this project, and was not involved in the design, conduct, analysis, interpretation of results, writing of the report or decision to submit the article for publication. The project also received support from the Southern California Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NIH/NCRR/NCATS) Grant # UL1TR000130 and NIH Grant No. GM 24211

Financial Disclosures: Anita L. Nelson receives Grants/Research support through Agile Pharmaceutical, ContraMed, Estetra SPRL, Evofem Inc, FHI (MonaLisa), Merck; receives Honoraria and serves on Speakers Bureau for Allergan, Bayer, Merck; serves as a Consultant/Advisory Board member for Agile, AMAG Pharma, Bayer, ContraMed, Merck PharmaNest. William J. Jusko has been a recent consultant for Novartis, Boehringer Ingelheim, Reveragen, and Bayer Healthcare Products. Frank Z. Stanczyk serves as a consultant for Agile Therapeutics, TherapeuticsMD, Pantarhei Bioscience, and Mithra Pharmaceuticals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84(4):363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Kapp N, Abitbol JL, Mathe H, et al. Effect of body weight and BMI on the efficacy of levonorgestrel emergency contraception. Contraception. 2015;91(2):97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Festin MP, Peregoudov A, Seuc A, Kiarie J, Temmerman M. Effect of BMI and body weight on pregnancy rates with LNG as emergency contraception: analysis of four WHO HRP studies. Contraception. 2017;95(1):50–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Gemzell-Danielsson K, Kardos L, von Hertzen H. Impact of bodyweight/body mass index on the effectiveness of emergency contraception with levonorgestrel: a pooled-analysis of three randomized controlled trials. Curr Med Res Opin. 2015;31(12):2241–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Praditpan P, Hamouie A, Basaraba CN, et al. Pharmacokinetics of levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate emergency contraception in women with normal and obese body mass index. Contraception. 2017;95(5):464–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Edelman AB, Cherala G, Blue SW, Erikson DW, Jensen JT. Impact of obesity on the pharmacokinetics of levonorgestrel-based emergency contraception: single and double dosing. Contraception. 2016;94(1):52–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bergman RN, Stefanovski D, Buchanan TA, et al. A better index of body adiposity Obesity (Silver Spring: ). 2011;19:1083–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].DuBois D, DuBois E. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. Arch Intern Med. 1916;17(6_2):863–71. [Google Scholar]

- [9].WHO. Body mass index - BMI. World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Edelman AB, Carlson NE, Cherala G, et al. Impact of obesity on oral contraceptive pharmacokinetics and hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian activity. Contraception. 2009;80(2):119–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Stanczyk FZ, Hiroi M, Goebelsmann U, Brenner PF, Lumkin ME, Mishell DR Jr. Radioimmunoassay of serum d-norgestrel in women following oral and intravaginal administration. Contraception. 1975;12(3):279–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Vermeulen A, Verdonck L, Kaufman JM. A critical evaluation of simple methods for the estimation of free testosterone in serum. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 1999;84(10):3666–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Nilsson B, von Schoultz B. Binding of levonorgestrel, norethisterone and desogestrel to human sex hormone binding globulin and influence on free testosterone levels. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation. 1989;27(3):151–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Goldman AL, Bhasin S, Wu FCW, Krishna M, Matsumoto AM, Jasuja R. A Reappraisal of testosterone’s binding in circulation: physiological and clinical implications. Endocrine Reviews. 2017;38(4):302–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Hautanen A Synthesis and regulation of sex hormone-binding globulin in obesity. International Journal of Obesity. 2000(Suppl 2);24:S64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Alvarez F, Brache V, Tejada A- S, Cochon L, Faundes A. Sex hormone binding globulin and free levonorgestrel index in the first week after insertion of Norplant® implants. Contraception. 1998;58(4):211–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gainer E, Massai R, Lillo S, et al. Levonorgestrel pharmacokinetics in plasma and milk of lactating women who take 1.5 mg for emergency contraception. Human Reproduction. 2007;22(6):1578–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Rosner W, Hryb DJ, Kahn SM, Nakhla AM, Romas NA. Interactions of sex hormone-binding globulin with target cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Apter D, Gemzell-Danielsson K, Hauck B, Rosen K, Zurth C. Pharmacokinetics of two low-dose levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine systems and effects on ovulation rate and cervical function: pooled analyses of phase II and III studies. Fertil Steril. 2014;101:1656–62 e1–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kuhnz W, Al-Yacoub G, Fuhrmeister A. Pharmacokinetics of levonorgestrel in 12 women who received a single oral dose of 0.15 mg levonorgestrel and, after a washout phase, the same dose during one treatment cycle. Contraception. 1992;46:443–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Amatayakul K, Laokuldilok T, Koottathep S, et al. The effect of oral contraceptives on protein metabolism. J Med Assoc Thai. 1994;77:509–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Jusko WJ. Clarification of contraceptive drug pharmacokinetics in obesity. Contraception. 2017;95:10–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Kuhnz W, Gieschen H. Predicting the oral bioavailability of 19-nortestosterone progestins in vivo from their metabolic stability in human liver microsomal preparations in vitro. Drug metabolism and disposition. 1998;26:1120–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Edelman AB, Cherala G, Stanczyk FZ. Metabolism and pharmacokinetics of contraceptive steroids in obese women: a review. Contraception. 2010;82:314–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ellero S, Chakhtoura G, Barreau C, et al. Xenobiotic-metabolizing cytochromes p450 in human white adipose tissue: expression and induction. Drug Metab Dispos. 2010;38:679–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Nilsson CG, Haukkamaa M, Vierola H, Luukkainen T. Tissue concentrations of levonorgestrel in women using a levonorgestrel-releasing IUD. Clin Endocrinol. 1982;17:529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Jung D, Mayersohn M, Perrier D, Calkins J, Saunders R. Thiopental disposition in lean and obese patients undergoing surgery. Anesthesiology Clinics of North America. 04/1982;56:269–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vasan RS. Cardiac function and obesity. Heart. 2003;89:1127–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Lesser GT, Deutsch S. Measurement of adipose tissue blood flow and perfusion in man by uptake of 85Kr. J Appl Physiol. 1967;23:621–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Ohlsson C, Wallaschofski H, Lunetta KL, et al. Genetic determinants of serum testosterone concentrations in men. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Willnow TE, Nykjaer A. Cellular uptake of steroid carrier proteins--mechanisms and implications. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:93–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.