Abstract

Purpose:

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis on the effect of drug holidays (discontinuation) on bone mineral density (BMD) and fracture risk.

Methods:

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases to locate controlled clinical trials and cohort studies evaluating the effect of drug holidays/discontinuation versus osteoporosis treatment continuation. We performed random-effects meta-analyses of hazard ratios of hip and any clinical osteoporotic fracture for individuals who discontinued bisphosphonates compared to persistent users.

Results:

Thirteen records reporting results from 8 different studies met inclusion criteria. The FLEX study found a reduced clinical vertebral fracture risk with 10 years of alendronate therapy compared to 5 (RR 0.45, 95%CI 0.24–0.85), and the HORIZON extension studies found a reduced risk of morphometric vertebral fracture with 6 years of zoledronic acid therapy compared to 3 (OR=0.51, 95%CI 0.26–0.95); subgroup analyses showed that women with low hip BMD T-scores after the initial treatment period benefitted from continued treatment in terms of reduced vertebral fracture risk. Meta-analysis of adjusted hazard ratios of hip and any clinical osteoporotic fracture for women who discontinued bisphosphonates revealed no significant differences in the risk of hip fracture (summary estimate of HR 1.09, 95%CI 0.87–1.37) or any clinical fracture (summary estimate of HR 1.13, 95%CI 0.75–1.70) compared to persistent users.

Conclusions:

Bisphosphonate discontinuation may be considered for women who do not have low hip BMD after 3 to 5 years of initial treatment, while women who have low hip BMD may benefit from treatment continuation.

Keywords: osteoporosis, bisphosphonates, drug holiday, systematic review, meta-analysis

Summary

We performed a systematic review on the effect of drug holidays (discontinuation) on BMD and fracture risk. Bisphosphonate discontinuation may be considered for women who do not have low hip BMD after 3–5 years of initial treatment, while women who have low hip BMD may benefit from treatment continuation.

Introduction

Osteoporosis affects 10 million people in the United States [1] and approximately half of postmenopausal women and one in five white men will experience an osteoporotic fracture [2], which are associated with significant morbidity, mortality, and costs [1–6]. Bisphosphonates are commonly used medications for osteoporosis treatment to reduce risk of fracture, but they should not be continued indefinitely due to limited efficacy data beyond 5 years and increased risk of rare serious adverse events such as atypical femur fractures and osteonecrosis of the jaw with increased treatment durations [7]. Thus drug holidays/discontinuation, or periods of time treatment is stopped, are an important consideration to reduce potential risks of treatment.

Currently various recommendations call for treatment decisions with respect to bisphosphonate discontinuation to be individualized [7, 8]. The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) recommends that after an initial 3 to 5 year treatment period with bisphosphonates a comprehensive risk assessment should be performed, and those who are at high risk for fracture should continue treatment with a bisphosphonate or alternative therapy, while it is reasonable to discontinue bisphosphonates in people at modest risk of fracture [7]. The American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR) recommends that after 5 years of oral bisphosphonate therapy or 3 years of intravenous bisphosphonate therapy reassessment of risk should be considered, and women at high risk, such as those with a low hip T-score, high fracture risk score, those with previous major osteoporotic fracture or fracture on therapy, or older women, bisphosphonate continuation for up to 10 years with oral therapy or 6 years with intravenous therapy, with periodic evaluation, should be considered [8]. For patients who stop treatment, the optimal duration of discontinuation before restarting treatment is unknown.

We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to summarize the evidence on the effect of osteoporosis treatment drug holidays/discontinuation on bone mineral density and/or fracture risk, to help guide decisions on when to discontinue therapy.

Methods

Data sources and search strategies

We searched PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane Library databases to locate clinical studies evaluating the effect of discontinuation from osteoporosis treatment on bone mineral density and/or fracture risk. We developed broad search strategies to have high sensitivity for locating relevant studies, and included a variety of search terms for osteoporosis, bone mineral density (BMD), fracture, drug holiday/discontinuation, osteoporosis medications, controlled clinical trials [9], and cohort studies. We performed the database searches on 1/24/18 for PubMed and Embase, and 1/25/18 for the Cochrane Library. Supplemental Table 1 shows the PubMed search strategy; the Cochrane Library and Embase strategies are available upon inquiry. The reference lists of included studies identified with the database search strategies were reviewed to locate additional relevant studies.

Study selection

We applied inclusion and exclusion criteria to the literature retrieved with the search strategies to choose relevant studies. We included studies that were controlled clinical trials or cohort studies; included patients with osteoporosis or osteopenia who had received osteoporosis treatment for at least three years; had at least two patient groups, one which continued on treatment and one which discontinued treatment (drug holiday); and reported the effect of drug discontinuation versus continuing on treatment on BMD and/or fracture risk. For studies whose results were reported in multiple publications, we excluded publications presenting duplicate data and included the publications reporting the most complete data from any study. No exclusion criteria were applied for any patient sociodemographic criteria, language of publication, or country where study was performed. We reviewed studies for inclusion versus exclusion in two stages – titles and abstracts were reviewed first, and studies determined to be possibly relevant after title and abstract screening underwent full-text review.

Data extraction

Relevant information was extracted from included studies, including sociodemographic characteristics of participants; number of participants; publication year; location/setting of study; osteoporosis medication(s) evaluated; sources of study funding; duration of treatment and duration of drug discontinuation; BMD and/or fracture outcomes data; adverse events data; and information about possible sources of bias.

Data analysis

We qualitatively described the characteristics of included studies and their findings on the impact of drug discontinuation on fracture outcomes and BMD, and also assessed study quality/risk of bias. For clinical trials, we assessed risk of bias in domains of selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, and reporting bias using the Cochrane Collaboration’s risk of bias tool [10]. For cohort studies, we assessed quality using the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale for cohort studies [11].

When two or more studies evaluated similar bisphosphonate(s), treatment durations, and discontinuation durations and reported the same fracture outcomes measures or sufficient information to calculate the same fracture outcomes measures (2 × 2 table values – the number of individuals who did and did not experience the outcome in the continued treatment and discontinuation groups), we conducted random effects meta-analysis with the DerSimonian and Laird method [12] to calculate summary effect size estimates. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed in each meta-analysis with I2 values. We performed all meta-analyses using Stata version 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Literature search and study selection

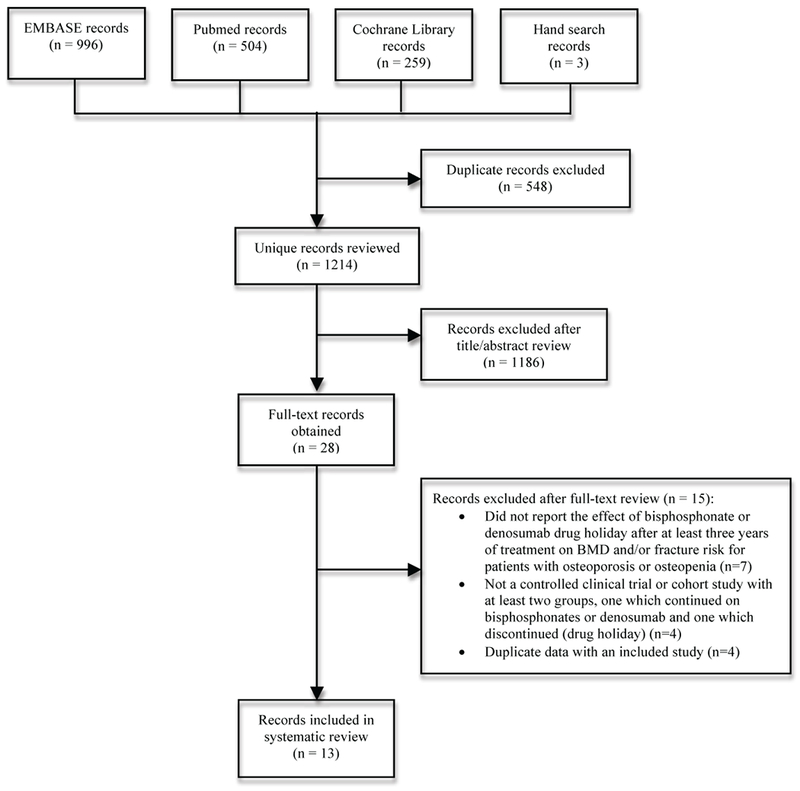

The literature search identified 1214 unique records (references); 28 records underwent full-text review, and 13 records reporting results from 8 different studies met inclusion criteria [13–25]. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the literature search and study selection process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of literature search and study selection

Study characteristics

Table 1 shows the characteristics of included studies. The studies were published between 1997 and 2018, all studies included women only, all but one study was performed in the United States, and number of patients for which data was evaluated ranged from 166 to 156,236. All included studies evaluated continued usage versus discontinuation of bisphosphonates. Data from 13 papers reporting results of 8 different studies were included. Of the 8 included studies, 4 were randomized controlled trials and 4 were retrospective cohort studies. Of the randomized controlled trials, two evaluated alendronate, one evaluated zoledronic acid, and one evaluated etidronate. All 4 cohort studies evaluated cohorts that had taken bisphosphonates, with alendronate predominating in all of the cohort studies. The included clinical trials all reported BMD as well as fracture outcomes, and all included cohort studies reported fracture outcomes only. All included clinical trials reported adverse event rates, but none of the included cohort studies reported adverse event rates. All 4 clinical trials and 1 of the cohort studies [19] reported pharmaceutical company funding.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Study | Study description | Relevant outcome results |

|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trials | ||

| HORIZON extension studies – Black, 2012 [14]; Black, 2015 [15]; Cosman, 2014 [18] | Health Outcomes and Reduced Incidence with Zoledronic acid Once Yearly-Pivotal Fracture Trial (HORIZON-PFT) was extended to 6 years (E1) and 9 years (E2). Postmenopausal women who received zoledronic acid for 3 years in the core study were randomized to 3 additional years of zoledronic acid or placebo (6 year extension, E1); and women on zoledronic acid for 6 years in E1 were randomized to 3 more years of zoledronic acid or placebo (9 year extension, E2). Number of participants: Z3P3 – 617; Z6 – 616; Z9 – 95; Z6P3 – 95 |

BMD percentage change from randomization (intention-to-treat (ITT) population) Femoral neck (FN): E1: +0.24% (Z6), −0.80% (Z3P3), difference 1.04%; p=0.0009 E2: −1.11% (Z9), −1.17% (Z6P3), difference 0.06%; p=0.935 Total hip (TH): E1: −0.36% (Z6), −1.58% (Z3P3), difference 1.22%; p<0.0001 E2: −0.54% (Z9), −1.31% (Z6P3), difference 0.78%; p=0.183 Lumbar spine: E1: +3.20% (Z6), +1.18% (Z3P3), difference 2.03%; p=0.002 Distal radius: E1: −0.12% (Z6), −0.49% (Z3P3), difference 0.37%; p=0.50 Fractures Morphometric vertebral fracture risk: E1: Z6 – 3.0% (n=14), Z3P3 – 6.2% (n=30), OR=0.51, 95% CI 0.26–0.95, p=0.035 E2: Z9 – 3.2% (n=3), Z6P3 – 5.3% (n=5), OR=0.58, 95% CI 0.13–2.55, p=0.461 Morphometric vertebral fracture incidence and OR in E1 for Z3P3 vs. Z6 by T-score at extension baseline and prior fracture subgroups: FN T-score ≤ −2.5: Z3P3 – 9.2% (23/250), Z6 – 3.5% (9/257), OR=0.36, 95% CI 0.15–0.77, p=0.01 FN T-score > −2.5: Z3P3 – 3.0% (7/235), Z6 – 2.4% (5/210), OR=0.79, 95% CI 0.23–2.53, p=0.70 TH T-score ≤ −2.5: Z3P3 – 14.3% (16/112), Z6 – 4.2% (5/120), OR=0.26, 95% CI 0.08–0.69, p=0.0113 TH T-score > −2.5: Z3P3 – 3.8% (14/373), Z6 – 2.6% (9/347), OR=0.68, 95% CI 0.28–1.58, p=0.3793 Incident MorphVertFx during Core: Z3P3 – 25% (4/16), Z6 – NA (0/11), p=0.12 No Incident MorphVertFx during Core: Z3P3 – 5.6% (26/467), Z6 – 2.6% (12/454), OR=0.46, 95% CI 0.22–0.90, p=0.03 Nonvertebral fracture incidence: E1: Z6 (estimated event rate – 8.2%) vs. Z3P3 (estimated event rate – 7.6%), HR 0.99, 95% CI 0.7–1.5 In E1 subgroup analyses based on TH BMD, prevalent vertebral fracture at baseline, and incident NVF in Core, there were no significant treatment effects (no significant differences between discontinuation and continuation groups). Clinical vertebral fracture incidence: E1: Z6 vs. Z3P3, HR 1.81, 95% CI 0.53–6.2 Hip fracture incidence: E1: Z6 (estimated event rate – 1.3%) vs. Z3P3 (estimated event rate – 1.4%), HR 0.9, 95% CI 0.33–2.49 All clinical fracture incidence: E1: Z6 vs. Z3P3, HR 1.04, 95% CI 0.71–1.54 E2: Z9 (estimate event rate – 12.2%) vs. Z6P3 (estimated event rate – 9.5%), HR 1.11, 95% CI 0.45–2.73, p=0.821 |

| FLEX extension studies – Black, 2006 [16]; Ensrud, 2004 [21]; Schwartz, 2010 [24] | The Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT) was extended to 10 years – the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX). Postmenopausal women who received alendronate for a mean of 5 years in FIT were re-randomized to 5 additional years of alendronate or placebo. Number of participants: 1099 (329 alendronate 5mg/day, 333 alendronate 10mg/day, 437 placebo) | Results from duration of FLEX: BMD mean percentage change Total hip: −1.02% (alendronate combined group); −3.38% (placebo); mean difference 2.36%, 95%CI 1.81% – 2.90%, p<0.001 Femoral neck: +0.46% (alendronate combined group); −1.48% (placebo); mean difference 1.94%, 95%CI 1.20% – 2.68%, p<0.001 Trochanter: −0.08% (alendronate combined group); −3.25% (placebo); mean difference 3.17%, 95%CI 2.49% – 3.84%, p<0.001 Lumbar spine: +5.26% (alendronate combined group); +1.52% (placebo); mean difference 3.74%, 95%CI 3.03% – 4.45%, p<0.001 Total body: +1.01% (alendronate combined group); −0.27% (placebo); mean difference 1.28%, 95%CI 0.70% – 1.86%, p<0.001 Forearm: −1.19% (alendronate combined group); −3.21% (placebo); mean difference 2.01%, 95%CI 1.35% – 2.68%, p<0.001 Fractures Clinical vertebral fracture risk: Continuing alendronate – 2.4% (16/662) vs. discontinuing – 5.3% (23/437), RR 0.45, 95%CI 0.24–0.85 Morphometric vertebral fracture risk: Continuing alendronate – 9.8% (60/662) vs. discontinuing – 11.3% (46/437), RR 0.86, 95%CI 0.60–1.22 Any clinical fracture risk: Continuing alendronate – 19.9% (132/662) vs. discontinuing – 21.3% (93/437), RR 0.93, 95%CI 0.71–1.21 Nonvertebral fracture risk: Continuing alendronate – 18.9% (125/662) vs. discontinuing – 19.0% (83/437), RR 1.00, 95%CI 0.76–1.32 Hip fracture risk: Continuing alendronate – 3.0% (20/662) vs. discontinuing 3.0% (13/437), RR 1.02, 95%CI 0.51–2.10 Forearm fracture risk: Continuing alendronate – 4.7% (31/662) vs. discontinuing 4.3% (19/437), RR 1.09, 95%CI 0.62–1.96 Nonvertebral fracture risk for alendronate group vs. placebo by T-score and prior fracture categories at FLEX baseline: FN T-score ≤ −2.5: Continuing alendronate – 22.6% vs. discontinuing 29.5%, RR 0.77, 95%CI 0.50–1.2 FN T-score > −2.5 to ≤ −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 20.5% vs. discontinuing 20.6%, RR 1.0, 95%CI 0.63–1.7 FN T-score > −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 14.9% vs. discontinuing 10.1%, RR 1.5, 95%CI 0.86–2.6 Prevalent vertebral fracture: Continuing alendronate – 27.7% vs. discontinuing 23.3%, RR 1.20, 95%CI 0.80–1.8 No prevalent vertebral fracture: Continuing alendronate – 14.1% vs. discontinuing 16.7%, RR 0.86, 95%CI 0.59–1.3 Clinical vertebral fracture risk for alendronate group vs. placebo by T-score and prior fracture categories at FLEX baseline: FN T-score ≤ −2.5: Continuing alendronate – 4.7% vs. discontinuing 8.3%, RR 0.57, 95%CI 0.23–1.40 FN T-score > −2.5 to ≤ −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 1.6% vs. discontinuing 7.1%, RR 0.22, 95%CI 0.05–0.74 FN T-score > −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 1.4% vs. discontinuing 1.7%, RR 0.84, 95%CI 0.18–4.2 Prevalent vertebral fracture: Continuing alendronate – 4.0% vs. discontinuing 8.0%, RR 0.47, 95%CI 0.19–1.1 No prevalent vertebral fracture: Continuing alendronate – 1.6% vs. discontinuing 3.8%, RR 0.42, 95%CI 0.16–1.1 Nonvertebral fracture risk for alendronate group vs. placebo for women without a vertebral fracture at FLEX baseline by T-score categories: FN T-score ≤ −2.5: Continuing alendronate – 14.7% vs. discontinuing 28.0%, RR 0.50, 95%CI 0.26–0.96, RD −13.32%, 95%CI −25.46 to −1.18 FN T-score > −2.5 to ≤ −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 12.4% vs. discontinuing 15.9%, RR 0.79, 95%CI 0.37–1.66 FN T-score > −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 14.8% vs. discontinuing 10.8%, RR 1.41, 95%CI 0.75–2.66 LS T-score ≤ −2.5: RR 0.64, 95%CI 0.28–1.49 LS T-score > −2.5 to ≤ −2.0: RR 0.65, 95%CI 0.27–1.61 LS T-score > −2.0: RR 1.00, 95%CI 0.62–1.62 Nonvertebral fracture risk for alendronate group vs. placebo for women with a vertebral fracture at FLEX baseline by T-score categories: FN T-score ≤ −2.5: Continuing alendronate – 33.3% vs. discontinuing 31.6%, RR 1.11, 95%CI 0.61–2.02 FN T-score > −2.5 to ≤ −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 35.9% vs. discontinuing 29.5%, RR 1.32, 95%CI 0.67–2.61 FN T-score > −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 15.2% vs. discontinuing 8.2%, RR 1.68, 95%CI 0.54–5.21 Morphometric vertebral fracture risk for alendronate group vs. placebo for women without a vertebral fracture at FLEX baseline by T-score categories: FN T-score ≤ −2.5: Continuing alendronate – 7.7% vs. discontinuing 11.0%, RR 0.68, 95%CI 0.24–1.90 FN T-score > −2.5 to ≤ −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 5.4% vs. discontinuing 7.6%, RR 0.69, 95%CI 0.21–2.22 FN T-score > −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 4.8% vs. discontinuing 5.7%, RR 0.84, 95%CI 0.30–2.31 Morphometric vertebral fracture risk for alendronate group vs. placebo for women with a vertebral fracture at FLEX baseline by T-score categories: FN T-score ≤ −2.5: Continuing alendronate – 25.4% vs. discontinuing 27.5%, RR 0.90, 95%CI 0.39–2.05 FN T-score > −2.5 to ≤ −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 17.7% vs. discontinuing 23.1%, RR 0.72, 95%CI 0.27–1.93 FN T-score > −2.0: Continuing alendronate – 11.5% vs. discontinuing 4.7%, RR 2.67, 95%CI 0.55–12.98 Results from interim analysis (3 years into FLEX): BMD mean percentage change (95%CI) Total hip: −0.34% (−0.64 – −0.05), alendronate combined group; −2.38% (−2.74 – −2.03), placebo group; mean difference 2.0%, p<0.001 Femoral neck: +0.57% (0.15 – 0.99), alendronate combined group; −1.10% (−1.61 – −0.60), placebo group; mean difference 1.7%, p<0.001 Trochanter: +0.71% (0.35 – 1.07), alendronate combined group; −1.90% (−2.34 – −1.46), placebo group; mean difference 2.6%, p<0.001 Lumbar spine: +3.50% (3.10 – 3.89), alendronate combined group; +0.97% (0.50 – 1.45), placebo group; mean difference 2.5%, p<0.001 Total body: +0.62% (0.35 – 0.90), alendronate combined group; −0.31% (−0.64 – 0.02), placebo group; mean difference 0.9%, p<0.001 Forearm: −0.90% (−1.31 – −0.49), alendronate combined group; −2.13% (−2.62 – −1.64), placebo group; mean difference 1.2%, p<0.001 |

| Extensions to Alendronate Phase III osteoporosis clinical trials – Bone, 2004 [17]; Tonino, 2000 [25] | Alendronate Phase III osteoporosis clinical trials were extended to 10 years, with randomized group assignments and blinding maintained. Women in the original active-treatment groups continued receiving alendronate during the first extension (years 4 and 5). In two subsequent extensions (years 6–7 and 8–10), women who had received alendronate 5mg or 10mg daily continued on same treatment. Women who had received 20mg of alendronate daily for first two years of the study followed by 5mg daily in years 3–5 subsequently received 5 years of placebo in years 6–10. Number of participants: 2nd extension (years 6–7) – 115 discontinuation group, 113 alendronate 5mg group, 122 alendronate 10mg group; 3rd extension (years 8–10) – 83 discontinuation group, 78 alendronate 5mg group, 86 alendronate 10mg group |

BMD mean percent change (95%CI) Lumbar spine: Years 6–7: Discontinuation group 0.20 (−0.51 to 0.91); alendronate 5mg group 1.45 (0.71 to 2.19); alendronate 10mg group 1.60 (0.92 to 2.28) Years 6–10: Discontinuation group 0.3 (−0.8 to 1.5); alendronate 5mg group 2.5 (1.3 to 3.6); alendronate 10mg group 3.7 (2.6 to 4.8) Years 8–10: Discontinuation group 0.2 (−0.7 to 1.1); alendronate 5mg group 1.2 (0.2 to 2.1); alendronate 10mg group 2.3 (1.4 to 3.1) Femoral neck: Years 6–7: Discontinuation group −0.46 (−1.54 to 0.62); alendronate 5mg group 0.32 (−0.77 to 1.41); alendronate 10mg group 0.49 (−0.53 to 1.51) Years 6–10: Discontinuation group −2.2 (−3.9 to −0.5); alendronate 5mg group 1.0 (−0.8 to 2.7); alendronate 10mg group 0.9 (−0.8 to 2.6) Years 8–10: Discontinuation group −1.7 (−3.0 to −0.3); alendronate 5mg group 0.3 (−1.2 to 1.7); alendronate 10mg group 1.0 (−0.3 to 2.4) Trochanter: Years 6–7: Discontinuation group −0.47 (−1.48 to 0.53); alendronate 5mg group 0.04 (−0.98 to 1.05); alendronate 10mg group 0.20 (−0.75 to 1.15) Years 6–10: Discontinuation group −1.0 (−2.7 to 0.6); alendronate 5mg group 0.0 (−1.7 to 1.7); alendronate 10mg group 1.0 (−0.7 to 2.6) Years 8–10: Discontinuation group −1.0 (−2.4 to 0.4); alendronate 5mg group 0.3 (−1.2 to 1.8); alendronate 10mg group 0.9 (−0.5 to 2.4) Total hip: Years 6–10: Discontinuation group −1.8 (−3.5 to −0.1); alendronate 5mg group 0.7 (−0.9 to 2.3); alendronate 10mg group 0.8 (−0.9 to 2.4) Years 8–10: Discontinuation group −1.6 (−2.8 to −0.4); alendronate 5mg group −0.2 (−1.4 to 1.0); alendronate 10mg group 0.1 (−1.1 to 1.3) Total body: Years 6–7: Discontinuation group −0.50 (−0.95 to −0.04); alendronate 5mg group −0.29 (−0.76 to 0.17); alendronate 10mg group 0.35 (−0.08 to 0.78) Years 6–10: Discontinuation group −0.6 (−1.7 to 0.4); alendronate 5mg group −0.7 (−1.8 to 0.3); alendronate 10mg group 0.4 (−0.6 to 1.4) Years 8–10: Discontinuation group −0.4 (−1.1 to 0.4); alendronate 5mg group −0.2 (−0.9 to 0.6); alendronate 10mg group −0.3 (−1.0 to 0.4) Distal 1/3 of forearm: Years 6–7: Discontinuation group −0.84 (−1.53 to −0.15); alendronate 5mg group 0.06 (−0.61 to 0.72); alendronate 10mg group 0.31 (−0.35 to 0.97) Years 6–10: Discontinuation group −2.3 (−3.8 to −0.8); alendronate 5mg group −0.4 (−1.8 to 1.0); alendronate 10mg group −0.1 (−1.6 to 1.3) Years 8–10: Discontinuation group −2.1 (−3.2 to −1.1); alendronate 5mg group −1.1 (−2.1 to −0.1); alendronate 10mg group −1.0 (−2.0 to 0.1) Fractures New morphometric vertebral fractures: Years 6–10: Discontinuation group 6.6%, alendronate 5mg group 13.9%, alendronate 10mg group 5.0% (differences among groups non-significant; p values not provided) First nonvertebral fractures: Years 8–10: Discontinuation group 12.0%, alendronate 5mg group 11.5%, alendronate 10mg group 8.1% Nonvertebral fractures: Years 6–7: Discontinuation group 7.8% (n=9), alendronate 5mg group 7.1% (n=8), alendronate 10mg group 6.6% (n=8) Clinical vertebral fractures: Years 6–7: Discontinuation group 7.0% (n=8), alendronate 5mg group 6.2% (n=7), alendronate 10mg group 6.6% (n=8) |

| Miller, 1997 [23] | In original study, women with postmenopausal osteoporosis randomized to cyclical etidronate or placebo for 2 years (etidronate 400mg/day or placebo for 14 days, followed by 76 days of calcium; cycle repeated 4 times each year), which most patients continued for 3rd year. Then, patients enrolled into open-label study for years 4–5 in which all patients received cyclical etidronate. Then, patients rerandomized to placebo or cyclical etidronate for years 6–7. Outcomes of interest included BMD and fractures. Number of participants: 193 (including 51 in 7-year group and 46 in 5-year group) |

BMD mean percent change (95%CI) Results for 7-year group (7 years of treatment) and 5-year group (5 years of treatment followed by 2 years of placebo) from baseline (beginning of year 6) to week 52 (end of year 6) and from baseline to week 104 (end of year 7): Spine: 52 weeks: 7-year group 0.5 (−0.44 to 1.44); 5-year group −0.6 (−1.72 to 0.52) 104 weeks: 7-year group 1.8 (0.41 to 3.19); 5-year group 1.4 (−0.78 to 3.58) Femoral neck: 52 weeks: 7-year group −0.5 (−1.77 to 1.07); 5-year group −0.3 (−1.97 to 1.37) 104 weeks: 7-year group 0.5 (−1.11 to 2.11); 5-year group −0.9 (−2.78 to 0.98) Trochanter: 52 weeks: 7-year group −0.3 (−1.50 to 0.90); 5-year group −1.30 (−2.44 to −0.16) 104 weeks: 7-year group 0.4 (−1.09 to 1.89); 5-year group −0.6 (−2.38 to 1.18) Distal Radius: 52 weeks: 7-year group 0.0 (−2.00 to 2.00); 5-year group 0.5 (−1.66 to 2.66) 104 weeks: 7-year group −1.1 (−3.61 to 1.41); 5-year group 0.2 (−1.64 to 2.04) Fractures Morphometric vertebral fractures during years 6 and 7: 7-year group: 2.4% (1/42); 5-year group: 10.2% |

| Cohort studies | ||

| Adams, 2018 [13] | Retrospective cohort study of women age ≥ 45 with ≥ 3 years bisphosphonate exposure (98.8% used alendronate) with ≥ 50% adherence. Participants with bisphosphonate holiday (≥ 12 months with no use) were compared to persistent users (≥ 50% adherence) and non-persistent users (<50% adherence) for outcome of incident osteoporosis-related fractures. Average BP holiday length was 3.1 +/− 1.6 years and occurred after 5.2 +/− 1.8 years of bisphosphonate use. Average individual length of follow-up was 4.0 +/− 2.4 person-years for persistent users, 4.1 +/− 2.4 for non-persistent users, and 4.9 +/− 2.5 person-years for women who had a bisphosphonate holiday. Number of participants: 39,502 (17,123 persistent users, 10,882 non-persistent users, 11,497 bisphosphonate holiday) |

Fractures Hazard ratios (adjusted) of fracture risk for bisphosphonate holiday group compared to persistent use group: Overall clinical osteoporosis-related fracture: HR 0.92, 95%CI 0.84-0.99 Hip fracture: HR 0.95, 95%CI 0.83-1.10 Vertebral fracture (clinical): HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.74-0.95 Hazard ratios (adjusted) of fracture risk for bisphosphonate holiday group compared to persistent use group stratified by lowest T-score, prior fracture, and fracture risk: Lowest T-score ≤ −2.5: Any osteoporotic fracture: HR 0.89, 95%CI 0.79-1.01 Hip fracture: HR 0.99, 95%CI 0.81-1.22 Vertebral fracture (clinical): HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.68-1.00 Lowest T-score −2 to −2.5: Any osteoporotic fracture: HR 0.86, 95%CI 0.71-1.05 Vertebral fracture (clinical): HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.60-1.14 Lowest T-score −1 to −2: Any osteoporotic fracture: HR 0.93, 95%CI 0.72-1.22 Hip fracture: HR 1.09, 95%CI 0.81-1.45 Lowest T-score ≥ −1: Any osteoporotic fracture: HR 1.00, 95%CI 0.56-1.79 Vertebral fracture (clinical): HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.58-1.23 Prior fracture: Any osteoporotic fracture: HR 0.79, 95%CI 0.67-0.94 Hip fracture: HR 0.81, 95%CI 0.52-1.28 Vertebral fracture (clinical): HR 0.74, 95% CI 0.52-1.05 No prior fracture: Any osteoporotic fracture: HR 0.94, 95%CI 0.86-1.03 Hip fracture: HR 0.97, 95%CI 0.83-1.14 Vertebral fracture (clinical): HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.75-0.98 High fracture risk: Any osteoporotic fracture: HR 0.88, 95%CI 0.78-0.99 Hip fracture: HR 1.00, 95%CI 0.81-1.22 Vertebral fracture (clinical): HR 0.85, 95% CI 0.71-1.02 Medium fracture risk: Any osteoporotic fracture: HR 0.93, 95%CI 0.75-1.15 Hip fracture: HR 1.15, 95%CI 0.79-1.67 Vertebral fracture (clinical): HR 0.78, 95% CI 0.54-1.11 Low fracture risk: Any osteoporotic fracture: HR 0.99, 95%CI 0.78-1.25 Hip fracture: HR 0.95, 95%CI 0.56-1.59 Vertebral fracture (clinical): HR 0.84, 95% CI 0.58-1.23 |

| Curtis, 2008 [19] | Retrospective cohort study of women ages 60–78 years at the beginning of study with ≥ 2 years compliance with bisphosphonate therapy (Medication Possession Ratio (MPR) ≥ 66%), with initial therapy with alendronate (77%) or risedronate (23%). Participants who discontinued bisphosphonates (MPR < 50%) were compared to those who remained on therapy for outcome of hip fracture. Number of participants with 3 years of prior bisphosphonate therapy: 4556 MPR ≥ 66%, 3715 MPR ≥ 80%. Number who continued/ discontinued therapy not provided. |

Fractures Hip fracture incidence rates among women who discontinued bisphosphonates versus those who did not after 3 years of prior bisphosphonate therapy: MPR ≥ 66%: 7.11 vs. 4.79 per 1000 person-years (p value not significant but not provided) MPR ≥ 80%: 6.34 vs. 5.11 per 1000 person-years (p value not significant but not provided) Adjusted hazard ratio of hip fracture per 90 days following discontinuation: MPR ≥ 66% at 3 years: 1.1 (0.9–1.4) MPR ≥ 80% at 3 years: 1.1 (0.8–1.5) Adjusted hazard ratio of hip fracture following discontinuation with time since discontinuation examined in discrete intervals: Time since discontinuation 0–9 months: MPR ≥ 66% at 3 years: 0.9 (0.3–2.5) MPR ≥ 80% at 3 years: 0.7 (0.2–2.4) Time since discontinuation >9 months: MPR ≥ 66% at 3 years: 2.7 (0.7–9.8) MPR ≥ 80% at 3 years: 2.0 (0.4–9.3) |

| Curtis, 2017 [20] | Retrospective cohort study of women with Medicare benefits who initiated a bisphosphonate (alendronate 71.7%, zoledronic acid 16.2%) and were at least 80% adherent for ≥ 3 years (“baseline”); then, “follow-up” began. Patients who continued vs. discontinued treatment were compared for the outcome of hip fracture. Median follow-up time of 2.1 years (interquartile range 1.0–3.3 years). Number of participants: 156,236 total (62,676 of whom stopped bisphosphonates ≥ 6 months) |

Fractures Hip fracture rate by duration of BP drug holiday (time since bisphosphonate discontinuation), adjusted for competing risk of death: 0 (i.e, current use): crude incidence rate per 1,000 person-years 9.6 (9.2, 10.1); adjusted hazard ratio 1.0 (reference) >0 to ≤ 3 months: crude incidence rate per 1,000 person-years 13.1 (12.0, 14.3); adjusted hazard ratio 1.29 (1.17, 1.42) >3 months to ≤ 1 year: crude incidence rate per 1,000 person-years 12.0 (11.0, 13.1); adjusted hazard ratio 1.12 (1.02,1.24) >1 to ≤ 2 years: crude incidence rate per 1,000 person-years 13.3 (12.0, 14.6); adjusted hazard ratio 1.21 (1.09, 1.35) >2 to ≤ 3 years: crude incidence rate per 1,000 person-years 15.7 (13.7, 17.8); adjusted hazard ratio 1.39 (1.21,1.59) |

| Mignot, 2017 [22] | Retrospective cohort study of postmenopausal women who continued or discontinued bisphosphonates (44% alendronate, 40% risderonate, 11% zoledronic acid, 5% ibandronate) after first-line therapy for 3 to 5 years, with outcome of interest of new clinical fractures. Number of participants: 183; six to 36-month follow-up data were available for 166 patients, of which 135 (81.3%) continued treatment and 31 (18.7%) discontinued (drug holiday) |

Fractures Percentage of patients with clinical fractures during follow-up: Continuation group: 11.9% (16/135) Drug holiday group: 16.1% (5/31) Number of patients with clinical fragility fractures during follow-up: Vertebral: drug holiday group 1/31; continuation group 6/135 Pelvic: drug holiday group 1/31; continuation group 3/135 Hip: drug holiday group 0/31; continuation group 2/135 Wrist: drug holiday group 0/31; continuation group 3/135 Foot: drug holiday group 1/31; continuation group 1/135 Rib: drug holiday group 0/31; continuation group 2/135 Fibula: drug holiday group 1/31; continuation group 0/135 Clavicle: drug holiday group 1/31; continuation group 0/135 Adjusted hazard ratio (HR) of new clinical fractures in drug-holiday patients compared to continuation group: 1.40, 95%CI 1.12-1.60; p=0.0095 |

Study quality and potential sources of bias

Study quality assessment evaluations are shown in Supplemental Tables 2 and 3. All 4 clinical trials received a summary assessment of unclear risk of bias, as a consequence of each study having at least one bias domain category in which they were assessed as having unclear risk of bias. With respect to the cohort studies, Adams et. al 2018 [13] was scored as receiving 9 out of 9 points on the Newcastle-Ottawa quality assessment scale, Curtis et al. 2008 [19] was scored as receiving 8 points, and Curtis et al. 2017 [20] and Mignot et al. 2017 [22] were each assessed as receiving 7 points. We considered a score of 7 and higher on the Newcastle-Ottawa scale to be indicative of a high-quality study, although universal standards for categorizing scores on this scale are not established.

Qualitative summary of clinical trial findings

Of the four included clinical trials, the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX) study and extensions to Alendronate Phase III Osteoporosis clinical trials evaluated alendronate discontinuation versus continuation [16, 17, 21, 24, 25], the Health Outcomes and Reduced Incidence with Zoledronic acid Once Yearly–Pivotal Fracture Trial (HORIZON–PFT) extension studies evaluated zoledronic acid discontinuation versus continuation [14, 15, 18], and a study by Miller et al. evaluated etidronate discontinuation versus continuation [23]. Data reported for the two alendronate studies were not sufficiently similar to permit meta-analysis for any fracture outcomes.

In the FLEX study, 1099 postmenopausal women who received alendronate for a mean of 5 years in the Fracture Intervention Trial (FIT) were re-randomized to 5 additional years of alendronate or placebo [16, 21, 24]. There were significant differences in favor of individuals who continued alendronate in terms of maintaining or increasing BMD at the total hip, femoral neck, trochanter, lumbar spine, total body, and forearm (Table 1). With respect to fracture outcomes, individuals who continued alendronate had significantly reduced relative risk of clinical vertebral fractures (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.24–0.85), but not other fracture categories compared to individuals who discontinued alendronate. In subgroup analyses, relative risk of clinical vertebral fracture was significantly reduced for women with FN T-scores between −2.5 and −2.0 at FLEX baseline who continued alendronate compared to those who discontinued, but there were no significant differences in relative risk of clinical vertebral fracture for women in other T-score categories or based on prior vertebral fracture status. For women without a vertebral fracture at FLEX baseline nonvertebral fracture risk was significantly reduced for individuals with FN T-scores ≤ −2.5 who continued alendronate compared to those who discontinued (RR 0.50, 95%CI 0.26–0.96, risk difference (RD) −13.32%, 95%CI −25.46% to −1.18%), but there were no significant differences in nonvertebral fracture risk for individuals in other FN or LS T-score categories. For women with a vertebral fracture at FLEX baseline, there were no FN T-score categories for which there were significant differences in risk of nonvertebral fracture. There were no significant differences in serious adverse events between groups.

In the extensions to Alendronate Phase III osteoporosis clinical trials, women who had received alendronate 5mg or 10mg daily in the original trial (years 1–3) plus first extension (years 4–5) continued on the same treatment in the second extension (years 6–7) and third extension (years 8–10), while women who had received 20mg of alendronate daily for the first two years of the study followed by 5mg daily in years 3–5 subsequently received 5 years of placebo in years 6–10 [17, 25]. A total of 247 individuals participated in the third extension. Both alendronate continuation groups experienced continued gains in BMD at the lumbar spine in years 6 to 10, whereas the discontinuation group did not have a significant change in lumbar spine BMD after year 5. Furthermore, both alendronate continuation groups did not experience a significant change in BMD at the femoral neck, total hip, or distal forearm, while the discontinuation group experienced significant decreases at those sites. With respect to fractures, in years 6–10 there were no significant differences among the groups with respect to new morphometric vertebral fractures. The safety profiles (adverse event rates) were similar among all three groups.

In the HORIZON-PFT extension studies, 1233 postmenopausal women who had received zoledronic acid for 3 years in the core study were randomized to 3 addition years of zoledronic acid (Z6) or placebo (Z3P3) in the 6 year extension (E1), and 190 women on zoledronic acid for 6 years in EI were randomized to 3 more years of zoledronic acid (Z9) or placebo (Z6P3) in the 9 year extension (E2) [14, 15, 18]. There were significant differences between the Z6 and Z3P3 groups in favor of the Z6 group better maintaining or increasing BMD at the femoral neck, total hip, and lumbar spine (Table 1); however, there were no significant differences between the Z9 and Z6P3 groups in terms of BMD percentage change at the femoral neck or total hip (Table 1). In terms of fracture outcomes, there were significantly fewer morphometric vertebral fractures in the Z6 group versus the Z3P3 group (OR=0.51, 95% CI 0.26–0.95), but no significant difference between the Z6 group and Z3P3 group in rates of other fracture categories. For the Z9 group compared to the Z6P3 group, there were no significant differences in morphometric vertebral fracture or all clinical fracture outcomes. In subgroup analyses, there was a significant reduction in odds of morphometric vertebral fracture for Z6 versus Z3P3 for individuals with femoral neck (FN) or total hip (TH) T-score ≤ −2.5 at extension baseline, but no significant reduction in odds of morphometric vertebral fracture for individuals with FN or TH T-scores > −2.5 at extension baseline (Table 1). There were no statistically significant differences in serious adverse events in the Z6 group compared to the Z3P3 group; there was a small increase in cardiac arrhythmias in the Z9 group compared to the Z6P3 group, but no significant difference in other safety parameters.

In a study published by Miller et al. in 1997, results of interest for this systematic review were presented for a group of 51 women that received cyclical etidronate for 7 years and a group of 46 women that received 5 years of cyclical etidronate followed by 2 years of placebo [23]. The group receiving cyclical etidronate for 7 years had a statistically significant increase in lumbar spine BMD in years 6–7, but the group receiving cyclical etidronate for 5 years did not (Table 1). Neither the 7-year group nor the 5-year group had statistically significant changes in BMD at the femoral neck, trochanter, or distal radius during years 6–7 of the study. With respect to incident morphometric vertebral fractures in years 6–7, a smaller percentage of individual in the 7-year group sustained new morphometric vertebral fractures compared to the 5-year group (2.4% vs. 10.2%), but no statistical significance was provided. Serious adverse events were described as comparable between the groups.

Qualitative summary of cohort study findings

All four included cohort studies evaluated the impact of continuing versus discontinuing bisphosphonates on fracture outcomes. Adams et al. published a retrospective cohort study of 39,502 women age 45 years and older who had 3 or more years of bisphosphonate exposure (almost all used alendronate), with at least 50% adherence [13]. Women who took a bisphosphonate holiday (at least 12 months with no use) were compared to persistent users (at least 50% adherence) and non-persistent users (less than 50% adherence) for outcomes of incident osteoporosis-related fractures. Average bisphosphonate holiday length was 3.1 +/− 1.6 years and occurred after 5.2 +/− 1.8 years of bisphosphonate use. Adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) of fracture for the bisphosphonate holiday group compared to the persistent use group were lower for overall clinical osteoporosis-related fracture (HR 0.92, 95%CI 0.84–0.99) and clinical vertebral fracture (HR 0.83, 95%CI 0.74–0.95); there was no significant difference in risk of hip fracture. In subgroup analyses for individuals with a history of prior fracture, the risk of any osteoporotic fracture was reduced for the bisphosphonate holiday group compared to the persistent user group (HR 0.79, 95%CI 0.67–0.94); there were no significant differences in the risk of hip or clinical vertebral fracture. In subgroup analyses for individuals with no prior history of fracture, the risk of clinical vertebral fracture was reduced for the bisphosphonate holiday group compared to the persistent user group (HR 0.85, 95%CI 0.75–0.98); there were no significant differences in the risk of any osteoporotic or hip fracture. In subgroup analyses stratified by fracture risk group, within the high risk subset individuals in the bisphosphonate holiday group were at reduced risk of any osteoporotic fracture compared to the persistent user group (HR 0.88, 95%CI 0.78–0.99); there were no significant differences in the risk of hip or clinical vertebral fracture.

A retrospective cohort study by Curtis et al. published in 2008 included women ages 60–78 years at the beginning of the study with at least 2 years compliance with bisphosphonate therapy (medication possession ratio (MPR) ≥ 66%); 77% had initial therapy with alendronate, 23% with risedronate [19]. Individuals who discontinued bisphosphonates (MPR < 50%) were compared to those who stayed on therapy for the outcome of hip fracture. The number of participants in the study who had 3 years of prior bisphosphonate therapy with a MPR ≥ 80% was 3715. They found no significant difference in hip fracture incidence rates or adjusted hazard ratios among women who discontinued bisphosphonates versus those who did not after 3 years of prior therapy (Table 1).

Another retrospective cohort study by Curtis et al. published as an abstract in 2017 included 156,236 women with Medicare benefits who initiated a bisphosphonate (71.7% alendronate, 16.2% zoledronic acid) and had at least 80% adherence for at least 3 years, after which follow-up began [20]. Over a median follow-up time of 2.1 years Curtis et al. found an increased risk of hip fracture for individuals who took drug holidays, with adjusted hazard ratios of 1.21 (95% CI 1.09 – 1.35) for individuals who had discontinued bisphosphonates for >1 to ≤ 2 years, and 1.39 (95% CI 1.21 –1.59) for individuals who had discontinued bisphosphonates for >2 to ≤ 3 years.

A small retrospective cohort study by Mignot et al. published in 2017 included 183 postmenopausal women who either continued or discontinued bisphosphonates after first-line therapy for 3 to 5 years [22]. Six to thirty-six month follow-up data were available for 166 patients of which 135 (81.3%) continued treatment and 31 (18.7%) discontinued. For the outcome of new clinical fractures, the adjusted hazard ratio for drug-holiday patients compared to the continuation group was 1.40 (95%CI 1.12–1.60).

Meta-analyses

We performed meta-analyses for the outcome measures of adjusted hazard ratios of hip fracture and any clinical osteoporotic fracture that included data from the cohort studies that reported these outcome measures. Meta-analysis results are shown in Table 2. There was no significant difference in the risk of hip fracture (summary estimate of HR 1.09, 95% CI 0.87–1.37) or any clinical fracture (summary estimate of HR 1.13, 95% CI 0.75–1.70) for individuals who discontinued bisphosphonates compared to persistent users of bisphosphonates.

Table 2.

Meta-Analysis Results

| Fracture outcome | Included cohort studies | Summary estimate of hazard ratio (HR)a (95%CI; I2 valueb) |

|---|---|---|

| Hip fracture | Adams, 2018 [13]; Curtis, 2008c [19]; Curtis, 2017d [20] | 1.09 (0.87–1.37; I2=74.1%) |

| Any clinical osteoporotic fracture | Adams, 2018 [13]; Mignot, 2017 [22] | 1.13 (0.75–1.70; I2=94.3%) |

Random-effects meta-analysis using DerSimonian and Laird method; results for bisphosphonate discontinuation group compared to persistent user group. Hazard ratios from included studies were all adjusted estimates presented in the studies.

Percentage of variation across studies attributable to heterogeneity

For Curtis et al. 2008 study [19], results for adjusted hazard ratio of hip fracture for individuals who had a time since bisphosphonate discontinuation of > 9 months compared to those who continued with a MPR of ≥ 80% were used for meta-analysis

For Curtis et al. 2017 study [20], results for adjusted hazard ratio of hip fracture for individuals who had a time since bisphosphonate discontinuation of > 1 to ≤ 2 years compared to those who continued were used for meta-analysis

Discussion

This systematic review identified 13 publications reporting results from 8 different studies (4 clinical trials, 4 cohort studies) that evaluated the impact of continued usage versus discontinuation of bisphosphonates after at least three years of prior treatment on BMD and fracture risk. With respect to the clinical trial findings for fracture outcomes, the FLEX study found that individuals who continued alendronate for 5 additional years after an initial 5-year treatment period had a significantly reduced relative risk of clinical vertebral fractures (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.24–0.85), but not any other fracture category, compared to those who discontinued treatment for 5 years [16]. The FLEX study also found that for women without a vertebral fracture at FLEX baseline (but not for women with a vertebral fracture at baseline) nonvertebral fracture risk was significantly reduced for individuals with FN T-scores ≤ −2.5 who continued alendronate compared to those who discontinued (RR 0.50, 95%CI 0.26–0.96, risk difference (RD) −13.32%, 95%CI −25.46% to −1.18%) [24]. The extensions to Alendronate Phase III osteoporosis clinical trials found no significant difference between individuals who continued alendronate for 5 additional years after an initial 5-year treatment period compared to those who discontinued treatment with respect to new morphometric vertebral fractures [17]. The HORIZON-PFT extension studies that evaluated zoledronic acid continuation or discontinuation after an initial treatment period of 3 or 6 years found that the Z6 group had significantly fewer morphometric vertebral fractures than the Z3P3 group (OR=0.51, 95% CI 0.26–0.95), but there were no significant differences between the Z6 group and Z3P3 group in rates of other types of fracture [14], and no significant differences between the Z9 group and the Z6P3 group in morphometric vertebral fracture or all clinical fracture outcomes [15]. Subgroup analysis by T-score categories at extension baseline showed a significant reduction in odds of morphometric vertebral fracture for Z6 versus Z3P3 for individuals with femoral neck (FN) or total hip (TH) T-score ≤ −2.5, but not for individuals with FN or TH T-scores > −2.5 at extension baseline [18]. With respect to the cohort study findings, meta-analysis of adjusted hazard ratios of hip fractures and any clinical osteoporotic fracture for individuals who discontinued bisphosphonates after an initial treatment period of at least 3 years compared to persistent users of bisphosphonates revealed no significant differences in the risk of hip fracture (summary estimate of HR 1.09, 95% CI 0.87–1.37) or any clinical fracture (summary estimate of HR 1.13, 95% CI 0.75–1.70).

Our systematic review findings were limited by a small number of included studies; relatively small sample sizes of several studies, particularly the included clinical trials; half of the included studies being cohort studies, with the associated methodological limitations; and all of the included clinical trials being assessed as having unclear risk of bias. Furthermore, we could only perform meta-analyses for fracture outcomes including data from the cohort studies; the clinical trial characteristics and reported data were not similar enough to enable meta-analysis. Moreover, alendronate was the predominant bisphosphonate evaluated in the majority of included studies; few studies assessed other bisphosphonates. Additionally, none of the included studies evaluated drug holidays/discontinuation for osteoporosis treatments other than bisphosphonates such as denosumab or included male study participants, and thus our findings are specific for bisphosphonates and female patients. Finally, it is possible that our literature search strategy may not have identified all relevant studies that exist, even though the search strategy was designed to be sensitive.

Despite these limitations, our findings suggest that it is likely reasonable to discontinue bisphosphonates after 3–5 years of initial treatment, particularly for women who do not have low hip BMD T-scores (e.g., ≤ −2.5) after the initial treatment period. The evidence suggests a reduced risk of clinical vertebral fracture for 10 years of alendronate therapy compared to 5, and a reduced risk of morphometric vertebral fracture with 6 years of zoledronic acid therapy instead of 3, with subgroup analyses suggesting that the individuals who benefit in terms of reduced vertebral fracture risk from continued treatment beyond the initial 3–5 year period are those with low hip BMD T-scores after the initial treatment period. There is not sufficient overall evidence at this time to support a benefit in terms of nonvertebral fracture risk reduction for continuing bisphosphonate treatment after an initial 3–5 year treatment period; however, one large cohort study of Medicare beneficiaries did find a lower risk of hip fracture for individuals who continued bisphosphonates after an initial treatment period of at least 3 years compared to those who discontinued [20], and thus further studies looking at the impact of bisphosphonate discontinuation on hip and/or other nonvertebral fractures may be worthwhile. On the basis of the current body of evidence, a reasonable approach may be to recommend bisphosphonate discontinuation for women who do not have low hip BMD after initial treatment (e.g., those with T-scores >−2.5) after 5 years of initial alendronate treatment or 3 years of initial zoledronic acid treatment, while considering discussion with patients who do have low hip BMD after the initial treatment period whether to continue bisphosphonate treatment for another 5 years (alendronate) or 3 years (zoledronic acid) to potentially reduce risk of clinical vertebral fractures and morphometric vertebral fractures, respectively. Data are limited on discontinuation studies using risedronate or ibandronate so further guidance on holidays with these bisphosphonates await additional studies. With respect to the duration of bisphosphonate discontinuation, further research would be useful to help clarify the period of time individuals who are on a drug holiday should stop bisphosphonates for and the parameters for restarting. The ideal length of the discontinuation period may likely vary based on the particular bisphosphonate and factors that affect fracture risk, such as T-scores and age. Other factors that may add to continuation of therapy include risk factors not included in FRAX but that are important to older adults such as fall risk, frailty, multiple comorbid conditions, and medications that contribute to falls and fractures. Future studies should include these factors when considering decisions about discontinuation of therapy and the duration of discontinuation.

Several organizations have published guidelines for osteoporosis care including recommendations with respect to bisphosphonate drug holidays/discontinuation. A report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR) published in 2016 recommended that after 5 years of oral bisphosphonate therapy or 3 years of intravenous bisphosphonate therapy reassessment of risk should be considered, and women at high risk, such as those with a low hip T-score, high fracture risk score, those with previous major osteoporotic fracture or fracture on therapy, or older women, bisphosphonate continuation for up to 10 years with oral therapy or 6 years with intravenous therapy, with periodic evaluation, should be considered [8]. The National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) published the Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis in 2014 that recommended that after an initial 3 to 5 year treatment period with bisphosphonates a comprehensive risk assessment should be performed, and those who are at high risk for fracture should continue treatment with a bisphosphonate or alternative therapy, while it is reasonable to discontinue bisphosphonates in people at modest risk of fracture [7]. Our study findings generally support the ASBMR and NOF guidelines, with the qualification that our findings suggest that the key factor that should be considered when deciding whether to discuss continuing bisphosphonate treatment beyond the initial 3 to 5 year treatment period is low hip BMD. Since osteoporosis is a chronic disease, bisphosphonate discontinuation will still require lifelong management and appropriate follow-up with the patients who may need therapy for osteoporosis, bone loss, or fractures at a later date.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that it would be reasonable to recommend bisphosphonate discontinuation for women who do not have low hip BMD after 3 to 5 years of initial treatment, while discussing possible continuation of therapy with a bisphosphonate for another 5 years (alendronate) or 3 years (zoledronic acid) for those who do have low hip BMD (e.g., those with T-scores ≤ −2.5) after the initial treatment period. Additional research would be useful to help clarify optimal durations of bisphosphonate discontinuation and the parameters for restarting.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Sources of funding:

Drs. Nayak and Greenspan were supported by grant R21AR072930 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Greenspan was also supported by NIH grants P30AG024827 and K07AG052668 from the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

Smita Nayak and Susan L. Greenspan declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Wright NC, Looker AC, Saag KG, Curtis JR, Delzell ES, Randall S, Dawson-Hughes B (2014) The recent prevalence of osteoporosis and low bone mass in the United States based on bone mineral density at the femoral neck or lumbar spine. J Bone Miner Res 29:2520–2526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Bone Health and Osteoporosis: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of the Surgeon General, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Osteoporosis prevention, diagnosis, and therapy. NIH Consens Statement. 2000;17(1):1–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lin JT, Lane JM (2004) Osteoporosis: a review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 126–134 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nguyen ND, Ahlborg HG, Center JR, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV (2007) Residual lifetime risk of fractures in women and men. J Bone Miner Res 22:781–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blume SW, Curtis JR (2011) Medical costs of osteoporosis in the elderly Medicare population. Osteoporos Int 22:1835–1844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, Lewiecki EM, Tanner B, Randall S, Lindsay R, National Osteoporosis F (2014) Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporos Int 25:2359–2381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adler RA, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Bauer DC, et al. (2016) Managing Osteoporosis in Patients on Long-Term Bisphosphonate Treatment: Report of a Task Force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res 31:16–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Higgins JPT, Green S (editors). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] Box 6.4.b: Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy for identifying randomized trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity- and precision-maximizing version (2008 revision); PubMed format. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. Available from www.handbook.cochrane.org. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. (2011) The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wells GASB, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 12.DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials 7:177–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adams AL, Adams JL, Raebel MA, Tang BT, Kuntz JL, Vijayadeva V, McGlynn EA, Gozansky WS (2018) Bisphosphonate Drug Holiday and Fracture Risk: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J Bone Miner Res 33:1252–1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Black D, Reid I, Boonen S, et al. (2012) The effect of 3 versus 6 years of zoledronic acid treatment of osteoporosis: a randomized extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res 27:243–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Black D, Reid I, Cauley J, et al. (2015) The effect of 6 versus 9 years of zoledronic acid treatment in osteoporosis: a randomized second extension to the HORIZON-Pivotal Fracture Trial (PFT). J Bone Miner Res 30:934–944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Black D, Schwartz A, Ensrud K, et al. (2006) Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA 296:2927–2938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bone H, Hosking D, Devogelaer J, et al. (2004) Ten years’ experience with alendronate for osteoporosis in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 350:1189–1199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cosman F, Cauley J, Eastell R, Boonen S, Palermo L, Reid I, Cummings S, Black D (2014) Reassessment of fracture risk in women after 3 years of treatment with zoledronic acid: when is it reasonable to discontinue treatment? J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99:4546–4554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Delzell E, Saag KG (2008) Risk of hip fracture after bisphosphonate discontinuation: implications for a drug holiday. Osteoporos Int 19:1613–1620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Curtis JR, Chen R, Li Z, Arora T, Saag K, Wright NC, Daigle S, Kilgore M, Delzell E (2017) The impact of the duration of bisphosphonate drug holidays on hip fracture rates [abstract]. Arthritis Rheumatol 69(suppl 10) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ensrud K, Barrett-Connor E, Schwartz A, et al. (2004) Randomized trial of effect of alendronate continuation versus discontinuation in women with low BMD: results from the Fracture Intervention Trial long-term extension. J Bone Miner Res 19:1259–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mignot MA, Taisne N, Legroux I, Cortet B, Paccou J (2017) Bisphosphonate drug holidays in postmenopausal osteoporosis: effect on clinical fracture risk. Osteoporos Int 28:3431–3438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller PD, Watts NB, Licata AA, et al. (1997) Cyclical etidronate in the treatment of postmenopausal osteoporosis: efficacy and safety after seven years of treatment. Am J Med 103:468–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schwartz A, Bauer D, Cummings S, et al. (2010) Efficacy of continued alendronate for fractures in women with and without prevalent vertebral fracture: the FLEX trial. J Bone Miner Res 25:976–982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tonino R, Meunier P, Emkey R, et al. (2000) Skeletal benefits of alendronate: 7-year treatment of postmenopausal osteoporotic women. Phase III Osteoporosis Treatment Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85:3109–3115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.