Abstract

Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) are an effective means to orchestrate the intricate biological processes required to sustain life. Approximately 650,000 PPIs underlie the human interactome, underscoring its complexity and the manifold signaling outputs altered in response to changes in specific PPIs. Our mini-review illustrates the growing arsenal of PPI-assemblies and offers insights into how these varied PPI-regulatory modalities are relevant to customized drug discovery, with a focus on cancer. We first categorize the known and emerging PPIs and PPI-targeted drugs of both natural and synthetic origin. Building on these conclusions, we discuss the merits of PPI-guided therapeutics over traditional drug design. Finally, we provide a compare-and-contrast section for different PPI blockers, with gain-of-function PPI interventions such as PROTACS.

Keywords: Protein-protein interactions (PPIs), quaternary associations, anti-cancer drugs, inhibitors, gain-of-function inducers

Introduction:

Better together?

Estimates of the human interactome indicate that there are around 650,000 protein-protein interactions (PPIs) in human cells.[1] Nevertheless, this number is only 0.2% of the total possible pairwise interactions in human cells. Furthermore, this number may not take into account that some proteins have multiple independent or partially-independent interactions with the same protein,[2] gain-of-function interactions induced by transformation/genetic instability[3] or administration of ectopic small molecules,[4] and modification-dependent switches among others.[5] Many PPIs occur with high affinity (Kd < 1 nM) and are relatively simple to detect by classical affinity methods, yet others have relatively low affinity (Kd > 1 µM to perhaps as high as 100, or more, µM[6]). Thus, deconvolution/identification of such PPIs is a complex, and overall unsolved problem.

Fortunately, many PPIs directly or indirectly orchestrate catalysis: e.g., the 19S-subunit of the proteasome recognizes K48-linked ubiquitinated proteins and ushers them to the proteasome core.[7] There are many other similar examples, such as formation of a pore complex from its constituent parts[8] or antizyme binding to ornithine decarboxylase (ODC), which ushers ubiquitin(Ub)-independent ODC degradation.[9] Indeed, PPIs that turn on activity are relatively simple to verify, because such PPIs obligatorily lead to a chemical change that can be read out analytically, and often occur in the absence of external stimuli. Furthermore, these activities can often be recapitulated in vitro to validate the interaction and that such association is sufficient to elicit a phenotype.

PPIs that positively or negatively modulate enzymatic activity can also be readily detected. For instance, Ub-conjugation activity of an E2-enzyme (Ube2N) is upregulated by the binding of a catalytically-defunct partner, Ube2V2.[10] Inhibitory PPIs are also established from in vitro and whole organism studies in the form of protease inhibitors, such as serpins.[11] Other examples include RAF-kinase-inhibitor protein,[12] and Sml1/Spd1 and IRBIT that downregulate the activity of the enzyme ribonucleotide reductase (RNR) from yeast and mammals, respectively,[13] both in their respective cells and in live organisms.

But some PPIs absolutely require context given by the cell, and in many of these cases independent enzymes are active in the absence of the complex. In many instances, these mechanisms serve an additional regulatory function, or seek to preserve valuable resources during times of stress. An early and extreme example of this phenomenon is the association of glycolytic enzymes.[14] This context-dependent association is believed to provide protection against stressed conditions,[15] to conserve resources. This association also prevents side reactions caused by the release of reactive metabolites from the active sites of glycolytic enzymes.[16] Another example is the purinosome, a 6-protein conglomerate involved in purine biosynthesis, which forms in a cell cycle- and resource-controlled manner.[17] Crucially, in vitro evidence supporting the purinosome assembly remains limited to date. Modern methods to investigate similar weak and/or context-dependent interactions thus seek to use cell-based experiments, where native associations are preserved.

Harvesting PPIs for drug development

It was initially believed that small, drug-like molecules would be unable to break PPIs.[18] This is because PPIs often occur across a large interaction surface area (ca. 1000–3000 Å2),[19] whereas drug-binding pockets tend to be smaller, e.g. <140 Å2 polar surface area, for most kinase inhibitors.[20] However, we now know that a PPI can be broken by a drug provided the drug targets a key interacting region (or ‘hot spot’) within the overall PPI interface (Fig. 1).[6a,21] An alternative approach to facilitate drug design is to target weaker, and easier-to-break, PPIs. The Cheng-Prussov relationship[22] shows that for a competitive ligand, the Ki of a drug will be affected by the competitor in the following way:

Thus, it could be argued that although harder to identify, weaker PPIs are more easily regulated and potentially more amenable to inhibitor design.[23] Non-competitive binders are not subject to such constraints (Ki (plus competitor) = Ki), and thus they constitute a general route to effective PPI inhibitors. Several non-competitive PPI modulators have been described and show some promise in disease models,[24] although none have so far reached the clinic for cancer therapy to the best of our knowledge.

Figure 1.

Different modes of protein regulation and pharmacologic interventions. (a) Enzyme–Substrate Interaction (applicable to only enzymes). (b) Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) (applicable to proteins whose function requires an interaction with another protein). (Left) PPIs can be stabilizing or blocking, and can also occur at the interaction site (orthosteric) or away from the interacting site (allosteric). (Right) PROTACs, a sub-set of PPI-modulators, promote an interaction between the target protein (P2) and an E2- or E3/E2-complex, leading to P2-ubiquitination and degradation. Note: a generic PROTAC mechanism involving recruitment of an E2/E3 complex is shown, exemplified by E3-ligase(PROTAC) binding to and recruitment of P2. Inset (lower right) illustrates proteome-level connectomics, wherein each sphere designates a protein and dark lines indicate specific PPIs, blunt-end and standard arrows designate inhibitory and stimulatory associations, respectively. The inset conveys the general possibility that perturbing the association between the two proteins (magenta and aqua-blue) impacts a wider interactome network than targeting/modulating a specific activity/function. Abbreviations in (a) and (b): E, enzyme; S, substrate; Pd, product; A, agonist; AA, allosteric-activator; I, inhibitor; M, PPI-modulator; P1, P2, interacting proteins.

PPI inducers

Although far less common than PPI-breakers, small molecules can also stabilize a PPI, leading to up/downregulation of enzymatic activity (Fig. 1b). Tafamidis (Fig. 2), approved in Europe and Japan, functions through activation/orthosteric stabilization of a PPI that is weakened in transthyretin-related hereditary amyloidosis.[25] Tafamidis binds to the dimer interface and stabilizes transthyretin dimers, which are destabilized in this disease.[26] Other examples of drugs proposed to proceed through this mechanism include lenalidomide, a thalidomide analog approved to treat myelodisplasic syndromes.[27] On the flip side, downregulation can also be induced. Cyclosporine is an approved immunosuppressant used to reduce rejection rate of transplants. This molecule binds to cyclophilin. The cyclosporine-cyclophilin complex is then able to interact with calcineurin A[28] and to inhibit its phosphatase activity. Calcineurin A phosphatase activity is required to activate NFAT family members that are involved in T-cell activation, thus suppressing immune response. A similar abortive ternary complex has been reported for the allosteric PPI-stabilizer CC0651 that targets CDC34A, a protein that promotes transition from G1- to S-phase and hence can be upregulated in cancer. The currently-accepted mechanism for this inhibitor is mixed allosteric/orthosteric stabilization of the CDC34A/ubiquitin complex.[29] This molecule has not appeared in clinical trials.

Figure 2.

Structure of small molecules relevant to the review. (a) Classical inhibitors (note: ClF, FlU, ClA have PPI-modulatory roles that may contribute to their clinical efficacies.[72–73,76–77]) (b) PPI-blockers. (c) PPI-stabilizers. (d) PPI-stabilizers that induce gain-of-function (e.g., PROTACs) or amplification of function following post-translational modifications (e.g., HNEylation[83]).

However, more complex outputs are possible; for example, mechanism-based formation of an abortive complex. An example of this mechanism is the NEDD8-E1-enzyme inhibitor (MLN4924) (Fig. 2), which is in clinical trials[30] for treatment of chronic myelomonocytic leukemia and acute myeloid leukemia. This molecule forms a covalent complex with Nedd8, which has high affinity for a NEDD8-specific activating enzyme, UBA3[31] (Fig. 3). Alternatively, PPI-inducers can stimulate gain-of-function behavior. One example of this behavior is the approved acute-promyelocytic-leukemia drug, arsenic trioxide. This molecule can bind directly to cysteine residues within the oncoprotein PML-RARA, inducing PML-RARA oligomerization.[32] These oligomers have high affinity for the SUMO-conjugating enzyme, UBC9, eliciting SUMOylation of PML-RARA, which then promotes PML-RARA degradation through the ubiquitin-proteasome system. We discuss the ramification of gain-of-function mechanisms and compare them to loss of function behaviors at the end of the manuscript.

Figure 3.

Ectopic PPI brought about by mechanistic inhibition. NEDD8 is a ubiquitin-like analog that is principally involved in activation of several Cullin E3s. MLN4924 can undergo a UBA3-catalyzed conjugation to NEDD8. The resulting modified protein is a potent inhibitor of UBA3, forming a stable modified NEDD8-UBA3 complex.[30–31,46] Note: UBA3 is typically complexed to the regulatory factor, NEDD8-activating enzyme E1 regulatory subunit (NAE1). However, NAE1 is omitted here for clarity.

Approved PPI blockers

Recent years have witnessed therapeutic PPI-modulators that function via targeted interference of specific PPI-interfaces (orthosteric binding).

Tirofiban (Fig. 2)—approved in 2000 for the treatment of cardiovascular thrombosis—inhibits the interaction between fibrinogen and platelet integrin receptor GP-IIb/IIIa.[33] Numerous other PPI-targeting drugs operate similarly to tirofiban, including eptifibatide (a disulphide-linked peptide macrocycle that functions through an orthosteric mechanism, Fig. 2).[34] Abciximab (an antibody fragment) has a similar effect to tirofiban and eptifibatide but functions through an allosteric inhibition mechanism.[35] The protein targets of these drugs reside in the blood, and thus cell permeability is not required. These drugs are also administered intravenously. We will later discuss that cell permeability and bioavailability can be an issue for some PPI-targeted drug candidates.

Venetoclax (Fig. 2) was approved in 2016 for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia that has a specific chromosomal deletion and has undergone one previous treatment.[36] Venetoclax is administered orally and targets BCL2-oncogenic protein (a specific member of the BCL2-family).[37] BCL2-family proteins suppress apoptosis by binding the proapoptotic proteins, BAX and BAK, and preventing their oligomerization. Oligomerization of BAX/BAD leads to permeabilization of the mitochondrial outer membrane, a key step in apoptosis. BH3-only proteins (natural inhibitors of the BCL2-family of proteins) compete with BAX/BAK binding to BCL2, and thereby promote apoptosis. After a screen for BH3-mimicking small molecules, venetoclax emerged as an efficient apoptosis inducer that is specific to BCL2.[38] Recently other candidates have emerged targeting other BCL2-family members. For instance, the BCLXL-specific inhibitor A-1331852 has been the subject of several studies, but has not yet reached clinical trials.

Allosteric examples of small molecule-PPI blockers are less common. MLN8237,[39] which reached Phase-III clinical trials for patients with relapsed T-Cell Lymphoma,[40] is a dual-functional Aurora-A-kinase inhibitor and allosteric-breaker of interaction between Aurora-A kinase and N-MYC. Since Aurora-A kinase/N-MYC-association is required for stabilization of N-MYC, treatment of cells with MLN8237 leads to degradation of N-Myc. This dual function allows MLN8237 to not only inhibit Aurora-A, a key driver of mitosis that is upregulated in aggressive cancers,[41] especially those with misregulated p53. This modality also allows inhibition of MYC-N, a key protooncogenic transcription factor that correlates with aggressiveness in numerous cancers.[42]

Targeting obligatory interactions

Several posttranslational modifications (PTMs) proceed by way of a PPI between a specific modifier enzyme and the target protein.[43] Such PPIs are obligate steps in ubiquitination, a process which provides a proofreading/recycling function via Ub-conjugation and Ub-deconjugation pathways, are PPI-orchestrated processes. We use the Ub-machinery as an example, although similar arguments hold for other processes, such as phosphorylation/dephosphorylation. Ub-conjugation involves E1, E2, and E3, respectively for, Ub-activation, Ub-conjugation, and Ub-ligation.[44] There are ~500–1000 human E3-ligases, ~50 E2-enzymes, and a handful of E1-enzymes.[45] Because of this hierarchy, attachment of Ub is a highly-specific process, wherein a ligase can have a few or even a single client. Thus, targeted inhibitors of an E3-ligase can engender selective inhibition of ubiquitination. However, most E3s—including RING-E3s (the largest class of E3s)—are scaffolds to direct E2-enzymes to a target protein. Because E2s (and especially E1s) have a much broader repertoire than E3s, inhibiting E1 and E2 steps of the Ub-chemical machinery is likely poorly tolerated: although some E2 inhibitors have been released, these have not entered the clinic; and indeed E1 inhibitors have not progressed beyond Phase I clinical trials, except MLN4924 (Fig. 2), which is in phase II. However, MLN4924 specifically targets a Ub-like protein activation pathway, specifically NEDD8, and hence is more focused than targeting Ub-specific E1 enzymes.[46] Thus, PPI-blocking of a specific E3 is considered an alternative selective strategy.[47] Compared to ubiquitination, removal of Ub is a much less enzyme-rich process: there are only ~100 deubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs) in humans.[48] Thus, DUBs tend to show promiscuity, although some specialized DUBs interact with a small number of clients, rendering PPI-based or activity-based inhibition of DUBs possible. By considering several examples of the specific arms of the ubiquitination machinery and other key emerging examples, we illustrate below the differences and subtleties of specific strategies.

• p53/MDM2

p53 is a tumor suppressor that is among the most-commonly mutated genes in cancer.[49] Although mutation/deletion/silencing of p53 is common in cancer, downregulation of wild-type (wt)-p53 also occurs frequently, e.g. in neuroblastoma.[50] One way to downregulate wt-p53 expression is overexpression of MDM2, an E3-ligase responsible for p53’s ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (Fig. 4).[51] In cancers reliant on MDM2 for wt-p53-suppression, MDM2-knockdown upregulates p53, causing apoptosis.[52] Thus, the p53/MDM2-PPI is considered druggable. Several candidates are in clinical trials, all of which appear to target p53-binding site on MDM2:[53] Nutlin-3a (Fig. 2) shows interesting synergism with other anti-cancer treatments,[54] and analogs have reached clinical trials; AMG-232 (Fig. 2) is orally available and is currently in Phase-IIa against metastatic melanoma.[55]

Figure 4.

The ubiquitination-dependent regulation of wt-p53: interplay between MDM2 and USP7.[50–53]

• MDM2/USP7

Like many E3s, MDM2 catalyzes its own ubiquitination as well as that of other clients.[56] To stabilize MDM2, a DUB (USP7) associates with MDM2. Knockdown or inhibition of USP7, in cancers manifesting MDM2-overexpression that suppresses wt-p53, results in MDM2 degradation and upregulation of p53-induced apoptosis (Fig. 4).[57] Interesting small-molecule inhibitors of USP7 have been developed.[58] Breaking the MDM2/USP7-PPI may be expected to lead to p53-upregulation in cancers that suppress wt-p53.[58]

• RAS

Roughly a third of all tumors harbor gain-of-function mutations in one of the RAS-proteins (H-, N- and K-).[59] RAS functions mainly as a scaffold. Thus, despite its privileged position in cancer etiology, the majority of disease-causing alleles are not directly targetable by classical enzyme-inhibitors, although there has been some significant interest concerning the K-RASG12C-mutant, housing an acquired cysteine.[60] Several covalent inhibitors, e.g., ARS-1620, target this reactive cysteine, although none has reached the clinic.

As a peripheral membrane protein, all RAS proteins undergo a series of enzyme-assisted PTMs on their C-terminal CAAX-motifs (Fig. 5a). Farnesylation allows recruitment of RCE1, which cleaves the RAS CAAX-motif, liberating a new C-terminus, which is methylated by ICMT1. There are also subsequent prenylation steps. For many years, all these processes were mined for druggability. However, owing to degeneracy in the lipidation step, farnesylation is now considered to be not a hugely-viable druggable event.[61] Although inhibition of RCE1 and other CAAX-processing strategies are still under investigation, these steps also appear to be dispensable.[62] Success has been found targeting kinases downstream of RAS (Fig. 5b): over the past two years, two MEK1/2 inhibitors (e.g., binimetinib, Fig. 2) have been approved. Such strategies are less general than RAS targeting, and upstream rerouting could potentially bypass MEK.[63] For these reasons, RAS is ideal for PPI-targeting drugs. Several RAS-binders have been disclosed, and the latest includes rigosertib (Fig. 2), a small molecule in phase-III trials against myelodysplasic syndromes after failure of methylating agents. Rigosertib binds the RAS-binding domain of RAS-effector proteins, blocking RAS-signaling.[64] This strategy does not directly target RAS and hence can in principal retain RAS-function while preventing disease-specific RAS signaling.

Figure 5.

Potential strategies to target RAS: post-translational modifications (PTMs) of RAS (a), and RAS-mediated signaling (b).[61–64] (a) PTMs—prerequisites for RAS activation/signaling—are directed by the conserved C-terminal CAAX motif (C, Cys; A, usually an aliphatic amino acid; X, any amino acid). Modification starts with Cys-farnesylation in the CAAX motif catalyzed by farnesyltransferase (FTase), then proteolytic cleavage of AAX, and carboxymethylation of the new C-terminus by RAS-converting CAAX endopeptidase 1 (RCE1) and isoprenyl Cys carboxyl methyltransferase 1 (ICMT1), respectively. Ras can be further modified by palmitoylation by palmitoyltransferase (PTase). Finally, RAS-escort proteins, such as phosphodiesterase 6 delta (PDEδ) and Galectin (not shown), recruit RAS to the plasma membrane. (b) Canonical RAS activation can begin when an extracellular, soluble growth factor (red), stimulates a receptor tyrosine kinase (illustrated as “Y” within the membrane), which in turn can activate guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) to convert RAS to an active GTP-bound state: RAS is inactivated by GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), which enhance the intrinsic GTPase activity of RAS to form GDP. Outlined afterwards are some of the most well-understood RAS signaling pathways. Direct RAS regulatory proteins are shown in green; kinases are shown in grey; transcription factors are shown in blue; apoptosis regulatory proteins are shown in peach.

• WDR5/MLL1

Given the need to compete against high-affinity PPIs, some PPI-blockers are of larger size than traditional small-molecule therapeutics. Such large sized molecules can have poor cell-permeability.[65] This issue was encountered for the small molecule MM401 (Fig. 2), which breaks the interaction between WDR5 (a scaffolding protein that is involved in histone regulation) and MLL1 (a histone methyl transferase, that positively regulates transcription).[66] The WDR5/MLL1-PPI drives acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) with mixed linear leukemic gene (Fig. 6).[67] MM401 is a peptide mimetic of MLL1, underscoring that PPI-breakers can be derived from rational design based on known PPI-interfaces.[68] Unfortunately, the bioavailability of MM401 is poor, restricting its use in complex models, and consequently limiting proof-of-concept studies of WDR5-targeting. A monobody(Mb)(S4) targeting the WDR5/MLL1 interaction has recently emerged.[69] Mb(S4) expression in a bone-marrow transplantation model of leukemia showed that Mb(S4) was more efficacious than a similar monobody that was unable to block the MLL1/WDR5 interaction.[67]

Figure 6.

MLL1/WDR5-complex promotes methylation of H3K4, promoting transformation[66–70]. Blocking MLL1/WDR5 interaction inhibits H3K4-methyltransferase activity of MLL1. MLL1, mixed lineage leukemia protein 1; WDR5, WD-repeat-containing protein 5; H3K4, histone-H3 lysine-4; me denotes methylation. HOXA9 and MEIS1 are leukemia-associated genes.

Critically, both MM401 and Mb(S4) display some excellent benefits of PPI-inhibition strategies over conventional activity-inhibition, or by extension, protein-degradation strategies. WDR5 is involved in critical cellular processes, including osteoblast differentiation.[70] WDR5 coordinates many of these processes through recruitment of different ligands to different binding sites.[70] MLL1 binding site on WDR5 is specific to MLL1, and so a small-molecule- or peptide-derived site-blocker can modulate MLL1-activity without affecting WDR5’s other cellular functions. Both small-molecule and monobody approaches demonstrate selective toxicity of MLL1-dependent lines, consistent with such selectivity stemming from PPI-interference.

Novel PPIs: novel drug targets

Many new PPIs and PPI-regulators are reported each year. We cannot do justice to all that great work in this review. We highlight two interesting findings from our laboratory that may help to illustrate how PPI-discovery can be applied to novel drug design, and also how discovery of new PPIs can open new avenues to drug actions.

ZRANB3/RNR-α

RNR-α—the larger subunit of the dual-subunit reductase RNR—is a paradigm of allosteric regulation.[71] This regulation is essential for RNR-activity-dependent dNTP pool maintenance and thus genome integrity (Fig. 7). dATP is an allosteric-feedback downregulator of RNR-reductase-activity. In humans, dATP-binding to RNR-α shifts its poorly defined reductase-active dimeric/hexameric states to a series of reduced-activity states in which all RNR-α’s are hexameric.[72] These hexamers are polymorphic,[73] indicating that the hexameric RNR-α could gain more than one function.[74] We hypothesized that dATP-binding to RNR-α elicits a gain-of-function event that triggers process(es) protecting the cell from hyper-elevated dATP/deoxynucleotide levels, which are mutagenic.[75] We further posited that this could be a means to access the previously-unexplained growth-suppressive role of RNR-α, which remained enigmatic, given the canonical RNR-reductase activity that by contrast positively correlates with tumor proliferation.[71] Yeast-2-hybrid analysis identified that RNR-α interacts with ZRANB3,[76] a poorly-characterized nuclear protein that is involved in DNA-damage repair, specifically, regulation of homologous recombination vs. lesion bypass. The nuclear-localization of ZRANB3 was intriguing because RNR-α is almost exclusively cytosolic.[77] But, our genetic and biochemical data established that hexameric RNR-α partially translocates into the nucleus through association with importin.[76] This study also found that ZRANB3 is a positive regulator of DNA synthesis, and RNR-α in the nucleus directly binds and inhibits ZRANB3, leading to DNA-synthesis suppression. Thus, we defined a PPI-mediated downregulation of DNA-synthesis that requires RNR-α-hexamerization-promoted partial nuclear import. Consistent with the multiple gain-of-function concept, we found that RNR-α nuclear translocation was suppressed by IRBIT, a known negative regulator of RNR in mammals,[13b] which also interacts selectively with hexameric RNR-α (Fig. 5).[76]

Figure 7.

Targeting ribonucleotide reductase large subunit (RNR-α). (a) Canonical enzymatic role of RNR-α.[71] (b) Non-enzymatic nuclear signaling role of RNR-α.[76] See text for discussion. RNR-β, RNR small subunit; ZRANB3, Zinc finger Ran-binding domain-containing protein 3; PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; IRBIT, inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) receptor-binding protein; NDPs, ribonucleoside diphosphates; dND(T)Ps, deoxyribonucleoside di(tri)phosphates; dATP, deoxyadenosine triphosphate; ClF/CLA/FLUD(T)P, di or triphosphate of clofarabine (ClF), cladribine (CLA), and fludarabine (FLU). See Figure 2 for corresponding chemical structures.

Although the full ramifications of ZRANB3 inhibition have not yet been mapped out, the ZRANB3/RNR-α DNA-synthesis inhibition axis likely serves to protect the cell during instances where elevated dNTP-levels render DNA synthesis deleterious/error prone.[78] ZRANB3-dependent DNA-synthesis promotion seems a good candidate for drug discovery because cancer cells are in a hyper-proliferative state and also have hyperactive RNR.[79] Thus, transformed cells are likely more susceptible to misregulation of dNTP pools. Hence, cancers may be more dependent on ZRANB3 to balance dNTPs than non-transformed cells. Indeed, we have provided some evidence that ZRANB3-promoted DNA synthesis is inhibited by rise in dATP flux on a similar time frame to which RNR-α translocates to the nucleus. Remarkably, DNA synthesis restart occurs concomitantly with RNR-α retro-translocation. Intriguingly, several nucleotide antimetabolites can elicit RNR-α hexamerization. One example is clofarabine, ClF, that is approved for treatment of various cancers including childhood leukemia.[80] Thus it is possible that ZRANB3 interference is also an aspect of some approved drug mechanisms, although clearly RNR-α inhibition is a key step in the action of these drugs.

PPI-targeting: broadening the therapeutic landscape

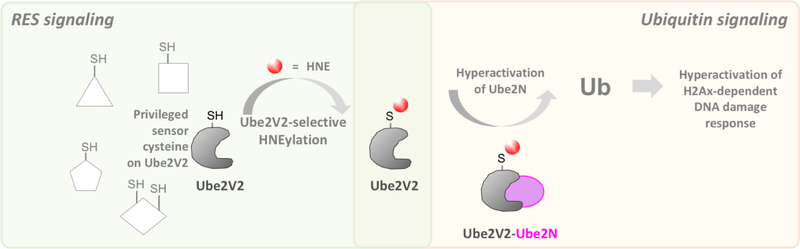

All anti-cancer interventions approved in 2017 and 2018 constitute inhibitors of one or a group of enzymes. Indeed, the majority of small-molecule interventions continue to be enzyme inhibitors.[81] Although some agonists have been approved, they are much fewer in number. As discussed above, PPIs serve numerous purposes and targeting a PPI can open new avenues to modulate cellular pathways not open to traditional small molecules. One simple means by which such a process could occur is through PPI stabilization.[82] More complex modalities are also possible. For instance, we recently discovered that a native reactive lipid-derived electrophile, 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE), can modify Ube2V2, the allosteric activator of Ube2N E2-ligase.[83] Ube2N is involved in both the DNA damage response (DDR) and NFκΒ-signaling.[10,84] HNEylation of Ube2V2 allosterically upregulated Ube2N’s DDR-regulatory axis, without affecting NFκΒ-signaling[83] (Fig. 8). Critically, significant DDR-upregulation occurred at low-occupancy HNEylation of Ube2V2, highlighting how signal-amplification—even at fractional ligand-occupancy—can have significant effects on pathway rewiring. These results indicate, that through PPIs, mining of novel targets functioning through novel mechanisms is achievable. Those targets can be accessed indirectly or allosterically (i.e., without the need to compete against high-occupancy/affinity binders). With such new activity modulation pathways, we can now regulate pathway flux in both directions, e.g., through downregulation of Ube2N-activity, or through homoallosteric/PPI-mediated upregulation using HNE-mimetics. Most notably, through PPI-modulation, we can selectively perturb a specific catalytic function of Ube2N (here, DDR regulation) without affecting Ube2N’s other activities. Such modes are not available to inhibitors, unless non-cannonical modalities are targeted.

Figure 8.

The E2-conjugation activity of the enzyme Ube2N is upregulated by HNEylation of privileged RES-sensing cysteine residue on Ube2V2, an allosteric binding-partner of Ube2N. This functional crosstalk between RES-regulation and ubiquitin signaling controls DNA damage response in zebrafish and cultured human cells.[83] Ub, ubiquitin; RES, reactive electrophile species; HNE, 4-hydroxynonenal.

Gain-of-function PPI drugs

As the usage of chemical biology-driven techniques are increasing, the scope for drug design is likewise broadening beyond the realms of simple protein-inhibition/blocking. One area where such a strategy has been highly successful is therapeutic antibody design, specifically bi-specific T-cell engagers, like the approved drugs blinatumomab and solitomab, approved for the treatment of acute lymphatic leukemia and gastrointestinal cancers, respectively.[54,85] Both antibodies bind to a cancer-specific surface marker and CD3-receptor, a specific marker of T-cells. Thus, immune cells are ushered to the tumor, selectively targeting cancerous cells. An analogous all-small-molecule approach has been reported.[86]

Forcing PPIs between a protein and the proteasome can lead to targeted destruction. Similar artificial PPIs can also be used to stimulate transcription and nuclear import/export.[87] The most advanced small-molecule example of this approach is PROTACS (Fig. 1b).[88] PROTACs, such as ARV-825 (Fig. 2), are bifunctional molecules that force novel PPIs by bringing an E3-ligase and a target-protein in close proximity, leading to proteasomal degradation of the target-protein. No PROTACS are approved yet, but there is significant excitement around these bifunctional-compounds.[89] PROTACs share some properties with other PPI-modulators as we outline below. However, as PROTACS function through a gain-of-function mechanism, they have their own specific traits that we also discuss.

Finally, we raise a note of caution about the employment of gain-of-function inducers that, as outlined below, has only been begun to be addressed (mainly in cell culture models of disease). It is known that many drugs were removed due to unintended off-target effects and some theory has been provided to explain tolerance of off-target effects of inhibitors in terms of targeting essential genes, and centrality of the networks targeted.[90] However, it is unknown whether gain-of-function ligands adhere to such caveats; it is unknown if off-target binding events for gain-of-function molecules can even be fairly compared to loss-of-function drivers. One such example is thalidomide, a molecule that modulates the activity of the E3 ligase, cereblon. This compound was withdrawn from usage as an anti-emetic due to teratogenic effects (that are not manifest in mouse models[91]), but has recently re-entered the market as an anti-plasma cell myeloma drug.[92] Thus, preclinical evaluation of compounds with new and interesting mechanisms should be treated with caution, and we will only get a picture of how novel drugs with novel mechanisms behave in clinical systems when such molecules move into complex models and ultimately clinical trials.

Comparison

Below we compare traditional inhibition with PPI-interference, and gain-of-function methodologies exemplified by PROTACs. This discussion is general, and each instance must be considered independently, but we hope to provide some framework for further consideration. PPI-interference can, in principal, target one specific sub-activity of a specific protein, be it chemical/enzymatic, ligand recruitment or structural. Furthermore, PPI-interference is applicable to almost any protein, regardless of whether the protein is chemically active. In addition, assuming a situation where an enzyme/scaffolding protein interacts with multiple substrates, PPI-interference can either block the enzyme/scaffold’s binding site (global turn off), or bind a specific substrate site (single binder blocking). PROTACs, as a subset of PPI-modulators, are also applicable to most proteins, provided the target cells express the relevant E3- or E2-ligase, and ideally, if the target protein has a relatively long half-life. Yet, PROTAC-engagement mandates loss of all activities of the target-protein. Thus, PROTACs share similarities with traditional inhibitors, which block all chemical activities that occur at a specific active site. However, traditional inhibitors (likely) leave other behaviours unaffected. Whether a complete shutdown or a local disruption of function is required, is context dependent.

For scaffolding proteins, it is clear that traditional inhibitors are ineffective, in all but a few gain-of-function scenarios, one of which, K-RASG12C, we exemplify above. Accordingly, PPI-mediated strategies are essential. However, total shutdown of some scaffolding proteins could be deleterious. Thus, a PPI-blocking strategy is likely to be more efficacious than a protein-degradation approach. For instance, RAS-degradation through PROTAC-like small molecules is possible and shows reduction of RAS-characteristic phenotypes in RAS-transformed cells.[93] An oncogenic-RAS-targeting siRNA is also in clinical trials against solid tumors driven by K-RAS.[94] Yet, since RAS has multiple functions essential for normal and transformed cells (e.g., K-RAS is an essential gene[95]), degrading RAS may bring additional/unforeseen issues. Similar conclusions can be drawn from the early clinical data on MDM2 inhibition.[96] Of course, such issues can be surmounted through allele-specific inhibition, although this strategy has not been shown for PROTACS, and is rare—but not-unprecedented—for traditional inhibitors.[97]

On the other hand, some oncoproteins have multiple disease-associated functions occurring at multiple sites.[98] The different isoforms of the oncoprotein BCR-ABL, p210 and p190, are most associated with causing chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) and some ALLs respectively. The p210 isoform possesses various domains, such as plekstrin-homology, GEF[99] and double homology domains, in addition to the kinase domain that are not present in p190 BCR-ABL.[54] Since the different isoforms of BCR-ABL can give rise to different disease outputs, it is likely that these non-kinase domains contribute to the oncogenic activity. These non-kinase domains may also be particularly important for drug resistance/persistence of stem cells post treatment with BCR-ABL-inhibitor, since in CML stem cells, the kinase activity of BCR-ABL is not necessary.[100] Ultimately, BCR-ABL degradation may be more efficacious than kinase inhibition or PPI-blocking alone to elicit a “cure”, rather than disease suppression (which is observed with “most” current treatments). Several strategies to degrade BCR-ABL are in development.[57,101]

Recently a pound-for-pound comparison of a targeted, reversible kinase inhibitor, Quizartinib [which has received breakthrough approval for relapsed/refractory FLT3-internal tandem duplication-(FTL-3-ITD)-positive AML] and the corresponding PROTAC, was released.[102] Critically, FLT3-ITD is difficult to inhibit over a sustained period and also is known to have scaffolding activities that can contribute to resistance. The consequential increase in FLT3-ITD upon inhibition contributes to non-kinase-related signaling roles. Given the preamble, it is unsurprising that the PROTAC was significantly more efficacious than Quizaritnib in cell culture. Intriguingly, the PROTAC also transpired to have unexpected benefits over Quizartinib, including that the PROTAC was considerably more selective for FLT3-ITD than Quizartinib. Importantly, the PROTAC did not cause degradation of the off-target binding proteins detected. A similar comparison with a similar conclusion was made for Defectinib, a FAK kinase inhibitor, versus a Defectinib-PROTAC analog.[103]

Despite these points, inhibition of enzyme activity is still an efficacious route to drug discovery. It is relatively simple to perform high-throughput screens for inhibitors of activity, and putative off-target effects can also often be counter screened. Furthermore, so long as drug engagement with target is possible, inhibition is highly likely. This aspect contrasts with PROTACs, where ancillary factors, e.g., E3- or E2-enzymes are also required for activity. Hijacking conserved chemistry or ligand binding can also allow development of semi-promiscuous drugs that target enzymes with overlapping functions. Several recently-approved drugs were deliberately designed to target two or more specific proteins. For instance, ribociclib (Fig. 2)—a dual, ATP-competitive inhibitor of CDK4/CDK6—approved for the treatment of metastatic breast cancer, and a multi-kinase inhibitor, midostaurin (Fig. 2), has also been approved.[104] Similarly, poly-pharmocologic DUB-inhibitors are being investigated.[43,57] Given the diversity and size of PPI-interfaces, it is harder to imagine how a PPI-intervention strategy could lead to targeting several clients of a scaffolding protein, unless the scaffold itself is blocked. But as we have seen above, this strategy can be too general and cause damage. Furthermore, as we have seen with Quizartinib above, PROTACs may be intrinsically limited in their applicability to multi-target (polypharmacological) approaches. This limitation is because there can be an inherent bias/proclivity to degrade a (or a subset) of binders to the PROTAC. It further remains not particularly well-understood how variable cell-to-cell such biases are, and how occupancy correlates to potency of the PROTAC. Only time can tell how these issues will be resolved.

Finally, it is noteworthy that comparisons of small-molecule efficacy are fraught with issues. These issues principally arise because of the complexity of biology, the variability of cell lines, and the varying models and approaches used by different researchers. Furthermore, few comparisons such as the PROTAC versus Quizartinib study discussed above actually exist. Critically, even the well-controlled PROTAC versus Quizartinib study was undertaken in cell culture, and hence would fail to recapitulate real drug-relevant scenarios and could ultimately produce confounding data, due to metabolism, permeation, unexpected toxicity, etc.

Outlook

The use of genotyping and our improved understanding of cancer etiology has opened doors to personalized therapies that in many instances have been highly successful. Examples range from the early successes of imatinib (Fig. 2) targeting BCR-ABL in CML, to more recent successes like selective estrogen-receptor destabilizers, e.g., fulvestrant (Fig. 2) in breast cancer therapy and beyond.[105] However, such strategies can be short-lived (less than 1 year).[106] In these instances, physicians and patients face an ever-evolving foe. This enemy—like the ancient goddess Thetis—responds to efforts to be tamed and reinvents itself to confound her pursuer. Whether solution to this problem is that we need better drugs, better drug targets, or that we use combination therapies; we ultimately need more drugs, ideally with new mechanisms targeting new proteins. PPI-inhibitors have the properties required to meet this demand. Furthermore, the cell is ripe with known and unknown emerging PPIs and endogenous small-molecule regulatory mechanisms. We suggest that identifying/understanding such regulatory mechanisms could be a resource to derive drugs targeting unconventional targets and/or with unconventional mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

Novartis Foundation for Medical-Biological Research (Switzerland); National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR): Chemical Biology (Swiss National Science Foundation), NIH innovator award (1DP2GM114850), and Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Lausanne (EPFL) are acknowledged for research support. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- [1].Stumpf MPH, Thorne T, Silva E. d., Stewart R, An HJ, Lappe M, Wiuf C, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105, 6959–6964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].a) Asmara H, Minobe E, Saud ZA, Kameyama M, Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 2010, 112, 397–404; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sebesta M, Cooper CDO, Ariza A, Carnie CJ, Ahel D, Nat Commun 2017, 8, 15847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].a) Alekseyenko AA, Walsh EM, Zee BM, Pakozdi T, Hsi P, Lemieux ME, Dal Cin P, Ince TA, Kharchenko PV, Kuroda MI, French CA, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, E4184–E4192; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Blevitt JM, Hack MD, Herman KL, Jackson PF, Krawczuk PJ, Lebsack AD, Liu AX, Mirzadegan T, Nelen MI, Patrick AN, Steinbacher S, Milla ME, Lumb KJ, J Med Chem 2017, 60, 3511–3517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Burslem GM, Crews CM, Chem Rev 2017, 117, 11269–11301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].a) Hunter T, Mol Cell 2007, 28, 730–738; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Parvez S, Long MJC, Poganik JR, Aye Y, Chem Rev 2018, 118, 8798–8888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].a) Chen J, Sawyer N, Regan L, Protein Science: A Publication of the Protein Society 2013, 22, 510–515; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Liu Q, Zheng J, Sun W, Huo Y, Zhang L, Hao P, Wang H, Zhuang M, Nat Methods 2018, 15, 715–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Saeki Y, The Journal of Biochemistry 2017, 161, 113–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bernis C, Forbes DJ, Methods in Cell Biology 2014, 122, 165–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hayashi S, Murakami Y, Matsufuji S, Trends in Biochemical Sciences 1996, 21, 27–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Eddins MJ, Carlile CM, Gomez KM, Pickart CM, Wolberger C, Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2006, 13, 915–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Law RHP, Zhang Q, McGowan S, Buckle AM, Silverman GA, Wong W, Rosado CJ, Langendorf CG, Pike RN, Bird PI, Whisstock JC, Genome Biology 2006, 7, 216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Escara-Wilke J, Yeung K, Keller ET, Cancer Metastasis Reviews 2012, 31, 615–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].a) Håkansson P, Dahl L, Chilkova O, Domkin V, Thelander L, The Journal of Biological Chemistry 2006, 281, 1778–1783; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Arnaoutov A, Dasso M, Science 2014, 345, 1512–1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Tian Y, Zhang H, Proteomics 2013, 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [15].Araiza-Olivera D, Sampedro JG, Mujica A, Pena A, Uribe-Carvajal S, FEMS Yeast Res 2010, 10, 282–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Menard L, Maughan D, Vigoreaux J, Biology (Basel) 2014, 3, 623–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].a) An S, Kumar R, Sheets ED, Benkovic SJ, Science (New York, N.Y.) 2008, 320, 103–106; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Chan CY, Zhao H, Pugh RJ, Pedley AM, French J, Jones SA, Zhuang X, Jinnah H, Huang TJ, Benkovic SJ, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 1368–1373; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Kyoung M, Russell SJ, Kohnhorst CL, Esemoto NN, An S, Biochemistry 2015, 54, 870–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].a) Benet LZ, Hosey CM, Ursu O, Oprea TI, Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 2016, 101, 89–98; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Arkin MR, Tang Y, Wells JA, Chem Biol 2014, 21, 1102–1114; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Arkin MR, Whitty A, Curr Opin Chem Biol 2009, 13, 284–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].a) Jin L, Wang W, Fang G, Annual Review of Pharmacology and Toxicology 2014, 54, 435–456; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Hwang H, Vreven T, Janin J, Weng Z, Proteins 2010, 78, 3111–3114; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Guo W, Wisniewski JA, Ji H, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters 2014, 24, 2546–2554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].a) Kinch MS, Surovtseva Y, Hoyer D, Drug Discovery Today 2016, 21, 1–4; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Veber DF, Johnson SR, Cheng H-Y, Smith BR, Ward KW, Kopple KD, Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 2002, 45, 2615–2623; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Fuller JC, Burgoyne NJ, Jackson RM, Drug Discovery Today 2009, 14, 155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].a) Vajda S, Beglov D, Wakefield AE, Egbert M, Whitty A, Curr Opin Chem Biol 2018, 44, 1–8; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fang Y, French J, Zhao H, Benkovic S, Biotechnology & Genetic Engineering Reviews 2013, 29, 31–48; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ferreira LG, Oliva G, Andricopulo AD, Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2016, 11, 957–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Craig DA, Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 1993, 14, 89–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Thompson AD, Dugan A, Gestwicki JE, Mapp AK, ACS Chem Biol 2012, 7, 1311–1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].a) Fischer G, Rossmann M, Hyvönen M, Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2015, 35, 78–85; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sondermann H, Soisson SM, Boykevisch S, Yang S-S, Bar-Sagi D, Kuriyan J, Cell 2004, 119, 393–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Maurer MS, Schwartz JH, Gundapaneni B, Elliott PM, Merlini G, Waddington-Cruz M, Kristen AV, Grogan M, Witteles R, Damy T, Drachman BM, Shah SJ, Hanna M, Judge DP, Barsdorf AI, Huber P, Patterson TA, Riley S, Schumacher J, Stewart M, Sultan MB, Rapezzi C, Investigators A-AS, The New England Journal of Medicine 2018, 379, 1007–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Ruberg FL, Berk JL, Circulation 2012, 126, 1286–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Fink EC, Ebert BL, Blood 2015, 126, 2366–2369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Huai Q, Kim HY, Liu Y, Zhao Y, Mondragon A, Liu JO, Ke H, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2002, 99, 12037–12042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Huang H, Ceccarelli DF, Orlicky S, St-Cyr DJ, Ziemba A, Garg P, Plamondon S, Auer M, Sidhu S, Marinier A, Kleiger G, Tyers M, Sicheri F, Nat Chem Biol 2014, 10, 156–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mavis C, Czuczman NM, Frys S, Klener P, Czuczman MS, Hernandez-Ilizaliturri F, Blood 2013, 122, 647–647. [Google Scholar]

- [31].a) Swords RT, Coutre S, Maris MB, Zeidner JF, Foran JM, Cruz J, Erba HP, Berdeja JG, Tam W, Vardhanabhuti S, Pawlikowska-Dobler I, Faessel HM, Dash AB, Sedarati F, Dezube BJ, Faller DV, Savona MR, Blood 2018, blood-2017–2009-805895; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; b) Brownell JE, Sintchak MD, Gavin JM, Liao H, Bruzzese FJ, Bump NJ, Soucy TA, Milhollen MA, Yang X, Burkhardt AL, Ma J, Loke H-K, Lingaraj T, Wu D, Hamman KB, Spelman JJ, Cullis CA, Langston SP, Vyskocil S, Sells TB, Mallender WD, Visiers I, Li P, Claiborne CF, Rolfe M, Bolen JB, Dick LR, Molecular Cell 2010, 37, 102–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhang X-W, Yan X-J, Zhou Z-R, Yang F-F, Wu Z-Y, Sun H-B, Liang W-X, Song A-X, Lallemand-Breitenbach V, Jeanne M, Zhang Q-Y, Yang H-Y, Huang Q-H, Zhou G-B, Tong J-H, Zhang Y, Wu J-H, Hu H-Y, de Thé H, Chen S-J, Chen Z, 2010, 328, 240–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].King S, Short M, Harmon C, Vascular Pharmacology 2016, 78, 10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Bhatia N, Sawyer RD, Ikram S, Methodist DeBakey Cardiovascular Journal 2017, 13, 248–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].de Belder MA, Sutton AG, Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 1998, 7, 1701–1717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].a) Deeks ED, Drugs 2016, 76, 979–987; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jones JA, Mato AR, Wierda WG, Davids MS, Choi M, Cheson BD, Furman RR, Lamanna N, Barr PM, Zhou L, Chyla B, Salem AH, Verdugo M, Humerickhouse RA, Potluri J, Coutre S, Woyach J, Byrd JC, The Lancet. Oncology 2018, 19, 65–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Roberts AW, Davids MS, Pagel JM, Kahl BS, Puvvada SD, Gerecitano JF, Kipps TJ, Anderson MA, Brown JR, Gressick L, Wong S, Dunbar M, Zhu M, Desai MB, Cerri E, Heitner Enschede S, Humerickhouse RA, Wierda WG, Seymour JF, The New England Journal of Medicine 2016, 374, 311–322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].a) Anderson MA, Deng J, Seymour JF, Tam C, Kim SY, Fein J, Yu L, Brown JR, Westerman D, Si EG, Majewski IJ, Segal D, Heitner Enschede SL, Huang DCS, Davids MS, Letai A, Roberts AW, Blood 2016, 127, 3215–3224; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Roberts AW, Huang DCS, Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2017, 101, 89–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].a) Dickson MA, Mahoney MR, Tap WD, D’Angelo SP, Keohan ML, Van Tine BA, Agulnik M, Horvath LE, Nair JS, Schwartz GK, Ann Oncol 2016, 27, 1855–1860; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Nassari S, Duprez D, Fournier-Thibault C, Front Cell Dev Biol 2017, 5, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].O’Connor OA, Özcan M, Jacobsen ED, Roncero Vidal JM, Trotman J, Demeter J, Masszi T, Pereira J, Ramchandren R, d’Amore FA, Foss F, Kim W-S, Leonard JP, Chiattone CS, Zinzani PL, Liu H, Jung J, Zhou X, Leonard EJ, Dansky Ullmann C, Shustov AR, 2015, 126, 341–341. [Google Scholar]

- [41].a) Nouri M, Ratther E, Stylianou N, Nelson CC, Hollier BG, Williams ED, Front Oncol 2014, 4, 370; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Crane R, Gadea B, Littlepage L, Wu H, Ruderman JV, Biol Cell 2004, 96, 215–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Brodeur G, Seeger R, Schwab M, Varmus H, Bishop J, Science 1984, 224, 1121–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Farshi P, Deshmukh RR, Nwankwo JO, Arkwright RT, Cvek B, Liu J, Dou QP, Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Patents 2015, 25, 1191–1208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Swatek KN, Komander D, Cell Research 2016, 26, 399–422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhao B, Bhuripanyo K, Schneider J, Zhang K, Schindelin H, Boone D, Yin J, ACS chemical biology 2012, 7, 2027–2035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].a) Cohen P, Tcherpakov M, Cell 2010, 143, 686–693; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ceccarelli DF, Tang X, Pelletier B, Orlicky S, Xie W, Plantevin V, Neculai D, Chou Y-C, Ogunjimi A, Al-Hakim A, Varelas X, Koszela J, Wasney GA, Vedadi M, Dhe-Paganon S, Cox S, Xu S, Lopez-Girona A, Mercurio F, Wrana J, Durocher D, Meloche S, Webb DR, Tyers M, Sicheri F, Cell 2011, 145, 1075–1087; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Malhab LJB, Descamps S, Delaval B, Xirodimas DP, Scientific Reports 2016, 6, 37775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Galdeano C, Future Medicinal Chemistry 2017, 9, 347–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Luise C, Capra M, Donzelli M, Mazzarol G, Jodice MG, Nuciforo P, Viale G, Fiore PPD, Confalonieri S, PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e15891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P, Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2010, 2, a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Chen L, Malcolm AJ, Wood KM, Cole M, Variend S, Cullinane C, Pearson ADJ, Lunec J, Tweddle DA, Cell Cycle 2007, 6, 2685–2696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Shi D, Gu W, Genes & Cancer 2012, 3, 240–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Inoue T, Geyer RK, Yu ZK, Maki CG, FEBS letters 2001, 490, 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Tisato V, Voltan R, Gonelli A, Secchiero P, Zauli G, Journal of Hematology & Oncology 2017, 10, 133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Secchiero P, Bosco R, Celeghini C, Zauli G, Current Pharmaceutical Design 2011, 17, 569–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].a) Canon J, Osgood T, Olson SH, Saiki AY, Robertson R, Yu D, Eksterowicz J, Ye Q, Jin L, Chen A, Zhou J, Cordover D, Kaufman S, Kendall R, Oliner JD, Coxon A, Radinsky R, Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2015, 14, 649–658; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Andreeff M, Kelly KR, Yee K, Assouline S, Strair R, Popplewell L, Bowen D Martinelli G, Drummond MW, Vyas P, Kirschbaum M, Iyer SP, Ruvolo V, González GMN, Huang X, Chen G, Graves B, Blotner S, Bridge P, Jukofsky L, Middleton S, Reckner M, Rueger R, Zhi J, Nichols G, Kojima K, Clinical Cancer Research: An Official Journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2016, 22, 868–876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Lim JH, Shin HW, Chung K-S, Kim N-S, Kim JH, Jung H-R, Im D-S, Jung C-R, PLOS ONE 2016, 11, e0163710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Lawson AP, Long MJC, Coffey RT, Qian Y, Weerapana E, El Oualid F, Hedstrom L, Cancer Research 2015, 75, 5130–5142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Lizbeth KH, Marcus JL, Ann L, 2016. Inhibitors of deubiquitinating proteases (WO/2016/014522)

- [59].Dang CV, Reddy EP, Shokat KM, Soucek L, Nature Reviews. Cancer 2017, 17, 502–508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Janes MR, Zhang J, Li L-S, Hansen R, Peters U, Guo X, Chen Y, Babbar A, Firdaus SJ, Darjania L, Feng J, Chen JH, Li S, Li S, Long YO, Thach C, Liu Y, Zarieh A, Ely T, Kucharski JM, Kessler LV, Wu T, Yu K, Wang Y, Yao Y, Deng X, Zarrinkar PP, Brehmer D, Dhanak D, Lorenzi MV, Hu-Lowe D, Patricelli MP, Ren P, Liu Y, Cell 2018, 172, 578–589.e517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].a) Mattingly RR, ISRN Oncology 2013, 2013; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Sousa SF, Fernandes PA, Ramos MJ, Current Medicinal Chemistry 2008, 15, 1478–1492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Mohammed I, Hampton SE, Ashall L, Hildebrandt ER, Kutlik RA, Manandhar SP, Floyd BJ, Smith HE, Dozier JK, Distefano MD, Schmidt WK, Dore TM, Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 2016, 24, 160–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Brighton HE, Angus SP, Bo T, Roques J, Tagliatela AC, Darr D, Karagoz K, Sciaky N, Gatza M, Sharpless NE, Johnson GL, Bear JE, Cancer Research 2017, canres.1653.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [64].Athuluri-Divakar SK, Vasquez-Del Carpio R, Dutta K, Baker SJ, Cosenza SC, Basu I, Gupta YK, Reddy MVR, Ueno L, Hart JR, Vogt PK, Mulholland D, Guha C, Aggarwal AK, Reddy EP, Cell 2016, 165, 643–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Qian Z, Dougherty PG, Pei D, Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 2017, 38, 80–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Xu J, Li L, Xiong J, denDekker A, Ye A, Karatas H, Liu L, Wang H, Qin ZS, Wang S, Dou Y, Cell Discovery 2016, 2, 16008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Cao F, Townsend Elizabeth C., Karatas H, Xu J, Li L, Lee S, Liu L, Chen Y, Ouillette P, Zhu J, Hess Jay L., Atadja P, Lei M, Qin Zhaohui S., Malek S, Wang S, Dou Y, Molecular Cell 2014, 53, 247–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Karatas H, Townsend EC, Cao F, Chen Y, Bernard D, Liu L, Lei M, Dou Y, Wang S, Journal of the American Chemical Society 2013, 135, 669–682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Gupta A, Xu J, Lee S, Tsai ST, Zhou B, Kurosawa K, Werner MS, Koide A, Ruthenburg AJ, Dou Y, Koide S, Nature Chemical Biology 2018, 14, 895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Zhu ED, Demay MB, Gori F, Journal of Biological Chemistry 2008, 283, 7361–7367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Aye Y, Li M, Long MJC, Weiss RS, Oncogene 2015, 34, 2011–2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].a) Aye Y, Stubbe J, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108, 9815–9820; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Fairman JW, Wijerathna SR, Ahmad MF, Xu H, Nakano R, Jha S, Prendergast J, Welin RM, Flodin S, Roos A, Nordlund P, Li Z, Walz T, Dealwis CG, Nat Struct Mol Biol 2011, 18, 316–322; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Hofer A, Crona M, Logan DT, Sjoberg BM, Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 2012, 47, 50–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].a) Wisitpitthaya S, Zhao Y, Long MJC, Li M, Fletcher EA, Blessing WA, Weiss RS, Aye Y, ACS Chemical Biology 2016, 11, 2021–2032; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Brignole EJ, Tsai KL, Chittuluru J, Li H, Aye Y, Penczek PA, Stubbe J, Drennan CL, Asturias F, Elife 2018, 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- [74].a) Jeffery CJ, Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2018, 373; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Jaffe EK, Trends Biochem Sci 2005, 30, 490–497; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Ali MH, Imperiali B, Bioorg Med Chem 2005, 13, 5013–5020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Chabes A, Thelander L, Cell Cycle 2003, 2, 172–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Fu Y, Long MJC, Wisitpitthaya S, Inayat H, Pierpont TM, Elsaid IM, Bloom JC, Ortega J, Weiss RS, Aye Y, Nature Chemical Biology 2018, 14, 943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Aye Y, Brignole EJ, Long MJC, Chittuluru J, Drennan CL, Asturias FJ, Stubbe J, Chemistry & Biology 2012, 19, 799–805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Chabes A, Stillman B, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 1183–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Evan GI, Vousden KH, Nature 2001, 411, 342–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Pession A, Masetti R, Kleinschmidt K, Martoni A, Biologics : targets & therapy 2010, 4, 111–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Kaczanowska S, Joseph AM, Davila E, Journal of Leukocyte Biology 2013, 93, 847–863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Andrei SA, Sijbesma E, Hann M, Davis J, O’Mahony G, Perry MWD, Karawajczyk A, Eickhoff J, Brunsveld L, Doveston RG, Milroy L-G, Ottmann C, Expert Opinion on Drug Discovery 2017, 12, 925–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Zhao Y, Long MJC, Wang Y, Zhang S, Aye Y, ACS Central Science 2018, 4, 246–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Deng L, Wang C, Spencer E, Yang L, Braun A, You J, Slaughter C, Pickart C, Chen ZJ, Cell 2000, 103, 351–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Brown P, Blood 2018, 131, 1497–1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].McEnaney PJ, Fitzgerald KJ, Zhang AX, Douglass EF, Shan W, Balog A, Kolesnikova MD, Spiegel DA, Journal of the American Chemical Society 2014, 136, 18034–18043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Stanton BZ, Chory EJ, Crabtree GR, Science 2018, 359, eaao5902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].a) Toure M, Crews CM, Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2016, 55, 1966–1973; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Ohoka N, Okuhira K, Ito M, Nagai K, Shibata N, Hattori T, Ujikawa O, Shimokawa K, Sano O, Koyama R, Fujita H, Teratani M, Matsumoto H, Imaeda Y, Nara H, Cho N, Naito M, Journal of Biological Chemistry 2017, jbc.M116.768853; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; c) Shi Y, Long MJC, Rosenberg MM, Li S, Kobjack A, Lessans P, Coffey RT, Hedstrom L, ACS Chemical Biology 2016, 11, 3328–3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Cancer Discovery 2018, 8, 377–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Wang X, Thijssen B, Yu H, PLOS Computational Biology 2013, 9, e1003119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Vargesson N, Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today 2015, 105, 140–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Rehman W, Arfons LM, Lazarus HM, Ther Adv Hematol 2011, 2, 291–308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Neklesa TK, Tae HS, Schneekloth AR, Stulberg MJ, Corson TW, Sundberg TB, Raina K, Holley SA, Crews CM, Nature Chemical Biology 2011, 7, 538–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Golan T, Khvalevsky EZ, Hubert A, Gabai RM, Hen N, Segal A, Domb A, Harari G, David EB, Raskin S, Goldes Y, Goldin E, Eliakim R, Lahav M, Kopleman Y, Dancour A, Shemi A, Galun E, Oncotarget 2015, 6, 24560–24570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Johnson L, Greenbaum D, Cichowski K, Mercer K, Murphy E, Schmitt E, Bronson RT, Umanoff H, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R, Jacks T, Genes & Development 1997, 11, 2468–2481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Riley MF, Lozano G, Genes & Cancer 2012, 3, 226–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Liao B-C, Lin C-C, Lee J-H, Yang JC-H, Journal of Biomedical Science 2016, 23, 86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Hardwick JM, Soane L, Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology 2013, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Tala I, Chen R, Hu T, Fitzpatrick ER, Williams DA, Whitehead IP, Leukemia 2013, 27, 1080–1089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Perl A, Carroll M, The Journal of Clinical Investigation 2011, 121, 22–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].a) Lai AC Toure M, Hellerschmied D, Salami J, Jaime‐Figueroa S, Ko E, Hines J, Crews CM, Angewandte Chemie International Edition 2016, 55, 807–810; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Khajapeer KV, Baskaran R, Leukemia Research and Treatment 2015, 2015, 757694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Burslem GM, Song J, Chen X, Hines J, Crews CM, J Am Chem Soc 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [103].Cromm PM, Samarasinghe KTG, Hines J, Crews CM, J Am Chem Soc 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- [104].Knudsen ES, Witkiewicz AK, Trends in Cancer 2017, 3, 39–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Nathan MR, Schmid P, Oncology and Therapy 2017, 5, 17–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Mansoori B, Mohammadi A, Davudian S, Shirjang S, Baradaran B, Advanced Pharmaceutical Bulletin 2017, 7, 339–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]