Abstract

People with serious mental illness (SMI) have mortality rates 2–3 times higher than the general population, mostly driven by physical health conditions. Behavioral health homes (BHHs) integrate primary care into specialty mental health care settings with the goal of improving management of physical health conditions among people with SMI. Implementation and evaluation of BHH models is increasing in the U.S. In this comprehensive review, we summarized the available evidence on the effects of BHHs on physical health care delivery and outcomes and identified perceived barriers and facilitators that have arisen during implementation to-date. We found 11 studies reporting outcomes data on utilization, screening/monitoring, health promotion, patient-reported outcomes, physical health, and/or costs of BHHs. The results of our review suggest that BHHs have resulted in improved primary care access and screening and monitoring for cardiovascular-related conditions among consumers with SMI. No significant effect of BHHs was reported for outcomes on diabetes control, weight management, or smoking cessation. Overall, the physical health outcomes data is limited and mixed, and implementation of BHHs is variable.

Keywords: serious mental illness, behavioral health home, physical health, outcomes, implementation

Introduction

People with serious mental illnesses (SMIs) such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder have mortality rates 2–3 times higher compared with that of general United States population (Brown, 1997; Colton & Manderscheid, 2006; Olfson, Gerhard, Huang, Crystal, & Stroup, 2015; Saha, Chant, & McGrath, 2007; Walker, McGee, & Druss, 2015). The primary leading cause of mortality in this population is cardiovascular disease, followed by cancer, cerebrovascular disease, and respiratory disease (Colton & Manderscheid, 2006; Newcomer & Hennekens, 2007; Olfson et al., 2015). Contributory to this premature mortality is the high prevalence of the cardiovascular risk factors obesity, poor diet, tobacco smoking, dyslipidemia, diabetes, and physical inactivity in the SMI population compared to the general population (Daumit et al., 2010; Mangurian, Newcomer, Modlin, & Schillinger, 2016; Newcomer & Hennekens, 2007; Osborn et al., 2008; Walker et al., 2015). Moreover, some antipsychotic medications contribute to weight gain, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia (De Hert, Detraux, van Winkel, Yu, & Correll, 2011; Tschoner et al., 2007), thereby increasing risk of physical health conditions.

Despite knowledge of the burden of somatic conditions within the SMI population, delivery of physical health care services to the SMI population has been limited in access and quality (Horvitz-Lennon, Kilbourne, & Pincus, 2006; McGinty, Baller, Azrin, Juliano-Bult, & Daumit, 2015). Traditionally, physical health services have been delivered in separate systems from mental health care (Davis, Reedy, & Little, 2013; Druss & Goldman, 2018; Horvitz-Lennon et al., 2006). This distinct separation has led to difficulties with provider communication and fragmentation of care (Horvitz-Lennon et al., 2006; Mechanic & Olfson, 2016).

Recently, interest has focused on integrated models of care to bridge the gap between physical and mental health services (Bao, Casalino, & Pincus, 2013; Druss & Goldman, 2018; Mechanic & Olfson, 2016). Patient-centered medical homes (PCMHs) are a primary-care transformation model designed to promote team-based care and to improve coordination of care (Jackson et al., 2013). They have been shown to improve access to primary care and behavioral health services (Domino, Wells, & Morrissey, 2015; Jackson et al., 2013), reduce emergency room services (Domino et al., 2015; Jackson et al., 2013), increase medication adherence (Beadles et al., 2015; Domino et al., 2015), and improve mental health outcomes (Sklar, Aarons, O’Connell, Davidson, & Groessl, 2015) among people with serious mental illness.

However, many people with SMI primarily access the health care system through their mental health care provider (Horvitz-Lennon et al., 2006). Therefore, behavioral health homes (BHHs) that integrate primary health care services into specialty mental health care settings have proliferated in recent years (Bao et al., 2013; McGinty et al., 2018; Smith & Sederer, 2009). In 2009, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) funded integration of primary care into community mental health settings through Primary and Behavioral Health Care Integration (PBHCI) grants (Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014). Similarly, under section 2703 of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), state Medicaid programs were incentivized to establish health homes integrating physical and mental health care for high-need, high-cost Medicaid beneficiaries such as those with SMI (Golembieweski, Askelson, & Bentler, 2015; Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014). Since that time, 16 states and the District of Columbia have implemented BHHs with a focus on SMI through the Affordable Care Act health home waiver (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2018).

Addressing premature mortality through provision of high quality primary care and improved physical health outcomes for the SMI population are public health priorities. While an increasing number of evaluations of individual BHH models have been published in recent years, there is no comprehensive review of the evidence on the effects of BHHs. The goal of this comprehensive review is two-fold: to summarize (1) the evidence on the effects of BHH programs on utilization, screening and monitoring, wellness and healthly lifestyle promotion, patient-reported outcomes, physical health outcomes, and costs, and (2) the facilitators and barriers that have arisen during implementation of BHH programs.

Methods

We conducted a comprehensive review of (1) studies evaluating the effects of BHHs on physical healthcare utilization, screening and monitoring, wellness and healthly lifestyle promotion, patient-centered care, physical health, and cost outcomes among consumers with SMI and (2) studies examining the barriers and facilitators of implementing BHHs.

Inclusion Criteria

We included both studies published in the peer-reviewed literature and non-peer-reviewed reports from the gray literature, e.g. evaluations of BHHs published by state Medicaid programs, as long as they met all other inclusion criteria. Both outcome evaluations and implementation studies were required to focus on a BHH, broadly defined as a specialty behavioral or mental health setting that coordinated and/or delivered clinical physical health care services for people with SMI. BHHs may also coordinate and/or deliver non-clinical services, for example behavioral weight loss programs, but coordination and/or delivery of clinical physical health services is the key defining component of the BHH. This definition was based on (1) the 2010 Affordable Care Act (Section 2703/1945 of the Social Security Act), which required a health home to integrate physical and behavioral health and long-term care services/supports for individuals with chronic disease, as guided by the Chronic Care Model, (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2018) and (2) SAMHSA’s definition which highlighted BHH as a delivery system design aimed at consumers with mental health or substance use disorder and at least one chronic condition (Alexander & Druss, 2012). Physical health care services reflect general medical care that is related to physical health status and not directly linked to behavioral health services, including primary care, preventative services, chronic disease management, and somatic subspecialist care. We included English-language studies published between January 2000 and August 2018, a timeframe that encompasses studies prior to and after the passage of the ACA, which supported the creation of health homes.

Outcome evaluations were required to have at least one pre- and one post- BHH physical health-related outcome measurement. Eligible outcome measurements included measures in five categories: physical health utilization (emergency department, inpatient, outpatient), physical health screening and monitoring (diabetes, dyslipidemia, blood pressure, weight, other), wellness and healthy lifestyle promotion (nutrition, weight management, physical activity, smoking cessation, other), patient-reported outcomes (patient satisfaction, patient activation), physical health outcomes (self-assessment, diabetes control or lowering, cholesterol lowering or control, blood pressure control or lowering, weight loss, Framingham risk score), and physical healthcare costs.

Implementation studies were required to have qualitative or quantitative data describing the barriers and/or facilitators to implementing a BHH. Barriers were defined as challenges or negatively-associated characteristics and/or circumstances that BHHs faced during health home implementation. Facilitators were defined as positively associated characteristics and/or circumstances that aided implementation of BHHs.

Search Strategy

Studies that met inclusion criteria were identified through searches of EMBASE, PsychInfo, and PubMed. Search strategies are fully detailed in Appendix A. Titles and abstracts were reviewed by the authors to determine if met inclusion criteria. If it was unclear from the title and abstract, the full article was reviewed. Additional studies were identified upon review of reference lists from included articles. States with Medicaid BHHs were reviewed and state-published reports were included if available and if they met inclusion criteria.

Data Abstraction

For all studies, the lead author systematically abstracted the following information using a standardized abstraction protocol: study publication year, data collection year(s), a description of the study population including demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the population served by the BHH, when available; and a description of the study setting.

For outcome evaluation studies, abstracted information also included physical health outcome measures; study design (randomized control trial, case-control, cohort), description of how the intervention and comparison group (if available) were defined, category of measure (utilization, screening and monitoring, quality of care, health outcomes, and cost), and presence or absence of statistical significance and directionality.

For implementation studies abstracted information on mental health and physical health partnerships (with descriptions of key team members), data sources (interviews, surveys, site visits, and reports), and perceived barriers and facilitators.

Results

Outcome Evaluations

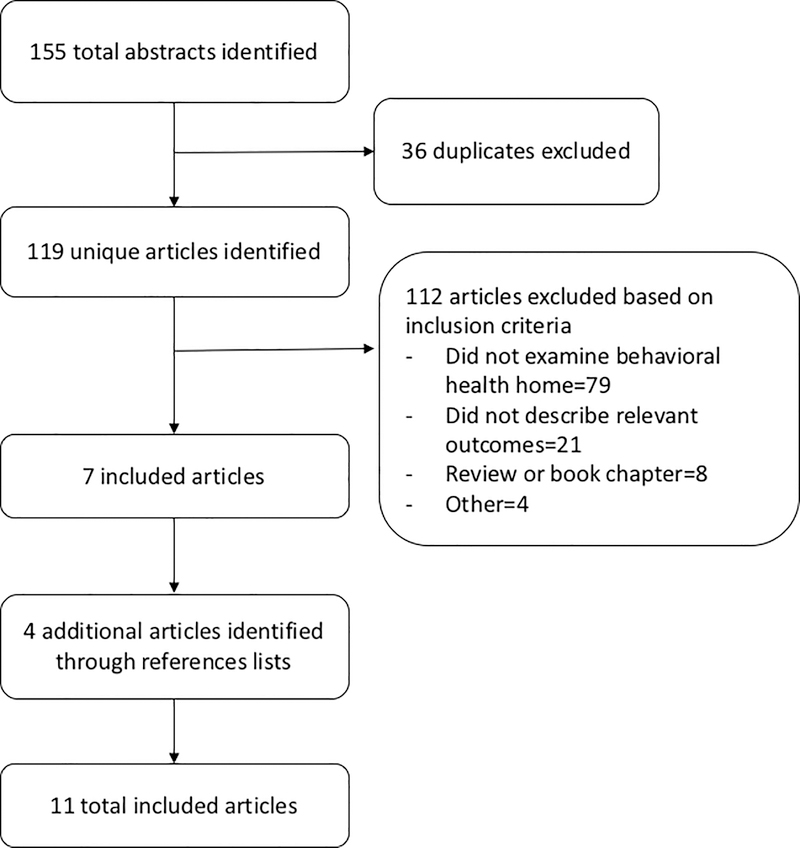

Our search resulted in 119 unique articles, of which 112 did not meet inclusion criteria. The main reasons for study exclusion were that the study did not evaluate a BHH (n=79), did not include physical health outcomes (n=21), or was a review article (n=8) (Figure 1). Four studies were the identified through review of included studies’ reference lists, for a final total of 11 studies. Of these, nine were peer-reviewed studies and two were gray literature reports.

Figure 1:

Literature flow diagram of studies reporting outcomes in behavioral health homes.

Evaluation characteristics

Among the nine peer-reviewed studies, two were randomized controlled trials, of which one occurred in the Veteran’s Administration Health System and one in a community mental health center (Druss, Rohrbaugh, Levinson, & Rosenheck, 2001; Druss et al., 2017) (Table 1). Both studies randomized participants to a BHH versus referral to a primary care clinic. The other seven peer-reviewed studies used an observational design with different comparison groups. Of these, five studies compared consumers at a BHH with consumers at a community mental health center that did not provide integrated health services (Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Han, et al., 2018; Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Yu, et al., 2018; Krupski et al., 2016; Scharf et al., 2016; Tepper et al., 2017). A sixth observational study compared outcomes of programs that were ranked as having a high level of integration of primary care into specialty mental health centers versus less well integrated programs, as assessed by the Integrated Treatment Tool, a scale developed by SAMHSA to assess integration and program improvement in BHHs (Gilmer, Henwood, Goode, Sarkin, & Innes-Gomberg, 2016). Finally, a seventh observational study examined physical health outcomes between SMI consumers who interfaced directly with a BHH provider compared with those who were given access to a web-based portal with electronic reminders and educational material (Schuster et al., 2018).

Table 1.

Evaluation designs and categories of outcomes measured in articles on behavioural health homes.

| Study | Study Design | Intervention group and comparison group | Study Population with SMI | Duration of Study (years) | Outcomes Measured | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Healthcare Utilization | Screening, Monitoring | Wellness and Healthy Lifestyle Promotion | Patient Centered Care | Physical Health Outcome | Costs | |||||

| Breslau 2018a | Retrospective cohort | Primary Care and Behavioral Health Integration (PBHCI) clinic grantees vs community mental health clinics that did not provide primary care services | 7893 consumers enrolled in Medicaid and PBHCI-awarded mental health clinic or community mental health clinics between February 2009 and February 2015 | 2–4 | X | |||||

| Breslau 2018b | Retrospective cohort | PBHCI grantees vs community mental health clinics that did not provide primary care services | 7893 consumers enrolled in Medicaid and PBHCI-awarded mental health clinic or community mental health clinics between February 2009 and February 2015 | 2–4 | X | X | ||||

| Druss 2001 | RCT | Integrated primary care vs referral to general medicine clinic | 120 consumers enrolled in Veterans Affairs mental health clinic who did not previously have a primary care provider | 1 | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| Druss 2017 | RCT | Community mental health center integrated with a Federally Qualified Health Clinic (FQH) vs usual care with a community provider | 447 consumers enrolled in community mental health and ≥1 cardio-metabolic risk factor | 1 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Gilmer 2016 | Prospective cohort | High vs low integration of care | 1941 consumers enrolled in integrated care program (Assertive Community Treatment (ACT)+ FQHC partnership or community mental health center +FQHC) | 1 | X | X | ||||

| Kruspki 2016 | Retrospective cohort | 762 consumers receiving mental health services at PBHCI or control mental health clinics in King County, Washington between February 2011 and September 2014 | 762 consumers rece422iving mental health services at PBHCI or control mental health clinics in King County, Washington between February 2011 and September 2014 | 1 | X | X | ||||

| Missouri 2017 | Retrospective pre/post | 24,065 consumers enrolled in Missouri Medicaid health home program beginning January 1, 2012 | 24,065 consumers enrolled in Missouri Medicaid health home program beginning January 1, 2012 | 1–5 | X | X | X | X | X | |

| Ohio 2015 | Retrospective cohort | 350 consumers enrolled in behavioral health home between January 2013 | 350 consumers enrolled in behavioral health home between January 2013 | 1 | X | X | X | X | ||

| Scharf 2016 | Prospective Case-control | 322 consumers enrolled in PBHCI program or control clinic, enrolled in August 2010 or August 2011 | 322 consumers enrolled in PBHCI program or control clinic, enrolled in August 2010 or August 2011 | 1 | X | |||||

| Schuster 2018 | Cluster randomized | 1229 consumers enrolled in community mental health clinic in Pennsylvania between October 2013-January 2014 | 1229 consumers enrolled in community mental health clinic in Pennsylvania between October 2013-January 2014 | 2–3 | X | X | X | |||

| Tepper 2017 | Retrospective cohort | 422 consumers enrolled in behavioral health program in September 2015 or received outpatient mental health care within urban safety-net academic medical system | 422 consumers enrolled in behavioral health program in September 2015 or received outpatient mental health care within urban safety-net academic medical system | 2 | X | X | X | |||

Both of the two gray literature evaluations, published by Ohio and Missouri state Medicaid programs, used observational designs (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017). The report from Ohio compared consumers at a BHH with consumers living in the same county but were not enrolled in a BHH (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015). The report from Missouri compared baseline health of a population prior to enrollment in BHHs versus health characteristics of the same population after enrollment and implementation of BHHs (Missouri HealthNet, 2017).

The studies also varied by geography and setting. One study was set across multiple states and multiple BHH sites (Scharf et al., 2016). Five studies were set across single states with multiple BHH locations (Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Han, et al., 2018; Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Yu, et al., 2018; Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Schuster et al., 2018). Two studies were set in single counties across multiple sites (Gilmer et al., 2016; Krupski et al., 2016), while one study was set in one health care system with multiple health home sites (Tepper et al., 2017). Four studies specifically looked at PBHCI grantees (Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Han, et al., 2018; Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Yu, et al., 2018; Krupski et al., 2016; Scharf et al., 2016).

Study Outcomes

Utilization

Emergency Department:

Of the seven studies examining ED utilization for physical health reasons, two studies reported total number of ED visits significantly decrease for consumers in BHHs (Druss et al., 2001; Tepper et al., 2017), while three evaluations saw no significant difference in utilization (Druss et al., 2017; Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Krupski et al., 2016) (Table 2). Similarly, one study found a significant decrease in ED utilization with one set of clinics but not at a second set of clinics studied (Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Han, et al., 2018). One study reported the decrease in utilization was driven by consumers with one or more ED visits (Tepper et al., 2017). While Missouri reported a decrease from 39% to 26% of BHH consumers who visited the ED for a medical issue over the course of 6 years (Missouri HealthNet, 2017), it is unclear whether this difference is statistically significant.

Table 2.

Outcomes reported in behavioural health home studies.

| Outcomes measured | Results (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Utilization | ED visits | Significant increase (0) |

| Significant decrease (3) (Druss 2001, Tepper 2017, Breslau 2018a- wave1) | ||

| Not significant (4) (Ohio 2015, Kruspski 2016, Druss 2017, Breslau 2018a- wave2) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

| Inpatient stays for medical conditions | Significant increase (1) (Breslau 2018b) | |

| Significant decrease (1) (Krupski 2016- one clinic) | ||

| Not significant (4) (Ohio 2015, Tepper 2016, Kruspki, 2016- one clinic, Druss 2017) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

| Outpatient primary care visits | Significant increase (3) (Druss 2001, Krupski 2016, Druss 2017) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (2) (Breslau 2018b, Schuster 2018) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Ohio 2015) | ||

| Outpatient specialty visits | Significant increase (0) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (2) (Druss 2017, Schuster 2018) | ||

| Indeterminate (0) | ||

| Screening and Monitoring | Diabetes screening (A1c or glucose) | Significant increase (5) (Druss 2001, Gilmer 2016, Druss 2017, Tepper 2017, Breslau 2018b- wave1) |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| No change (1) (Breslau 2018b- wave 2) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

| Diabetes monitoring (for consumers with existing diabetes diagnosis) | Significant increase (1) (Druss 2017) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (1) (Breslau 2018b) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

| Dyslipidemia screening | Significant increase (3) (Druss 2001, Gilmer 2016, Breslau 2018b- wave 1) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (3) (Druss 2017, Tepper 2017, Breslau 2018b- wave 2) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

| Blood pressure monitoring | Significant increase (3) (Druss 2001, Gilmer 2016, Druss 2017) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (0) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

| Other preventative screening (hepatitis, tuberculosis, vaccination, colon cancer screening) | Significant increase (2) (Druss 2001, Druss 2017) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (0) | ||

| Indeterminate (0) | ||

| Wellness and Healthy Lifestyle Promotion | Nutrition | Significant increase (1) (Druss 2001) |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (0) | ||

| Indeterminate (3) (Druss 2017, Missouri 2017, Ohio 2015) | ||

| Weight management | Significant increase (1) (Druss 2001) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (0) | ||

| Indeterminate (3) (Druss 2017, Missouri 2017, Ohio 2015) | ||

| Physical activity | Significant increase (1) (Druss 2001) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (0) | ||

| Indeterminate (3) (Druss 2017, Missouri 2017, Ohio 2015) | ||

| Smoking cessation | Significant increase (1) (Druss 2001) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (1) Scharf 2016) | ||

| Indeterminate (3) (Druss 2017, Missouri 2017, Ohio 2015) | ||

| Other (advanced directive, STI counseling) | Significant increase (Druss 2001) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (0) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Druss 2017) | ||

| Patient Reported Outcomes | Patient satisfaction | Significant increase (1) (Druss 2001) |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (0) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Ohio 2015) | ||

| Patient activation | Significant increase (1) (Schuster 2018) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (1) (Druss 2017) | ||

| Indeterminate (0) | ||

| Physical Health Outcomes | Self-assessment of physical health (SF36, SF 12v2) | Significant increase (2) (Druss 2001, Gilmer 2016) |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (2) (Druss 2017, Schuster 2018) | ||

| Indeterminate (0) | ||

| Diabetes control (A1c or glucose lowering, % control) | Significant increase (0) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (3) (Scharf 2016, Druss 2017, Tepper 2017) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

| Cholesterol (lowering or % control) | Significant increase (1) (Scharf 2016) | |

| Significant decrease (00 | ||

| Not significant (2) (Druss 2017, Tepper 2017) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

| Blood pressure (lowering, % control) | Significant increase (1) (Druss 2017) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (1) (Scharf 2016) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

| Weight Loss (lowering weight, BMI) | Significant increase (0) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (1) (Scharf 2016) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

| Framingham CHD risk score | Significant increase (0) | |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (1) (Druss 2017) | ||

| Indeterminate (0) | ||

| Costs | Includes direct, indirect costs, utilization | Significant increase (Ohio) |

| Significant decrease (0) | ||

| Not significant (2) (Druss 2001, Krupski 2016) | ||

| Indeterminate (1) (Missouri 2017) | ||

Inpatient:

For inpatient stays for medical conditions, heterogeneous results were observed. Two observational studies that each used propensity matched controls found opposing results. One found a significant increase in number of stays (Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Han, et al., 2018), while the other found a significant decrease in percentage of consumers with an inpatient stay at one site (Krupski et al., 2016). Three evaluations found no difference in inpatient utilization (Druss et al., 2017; Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Tepper et al., 2017) and a fourth study found no difference at one out of two sites studied (Krupski et al., 2016). In its annual state report, Missouri reported a decrease from 21% to 13% of behavioral health consumers who were hospitalized for medical reasons over a 6 year period (Missouri HealthNet, 2017), a trend that also could not be determined if it reached statistical significance.

Outpatient:

In regards to primary care utilization, both RCT studies and one observational study found a significant increase after implementation of a BHH (Druss et al., 2001; Druss et al., 2017; Krupski et al., 2016). Two observational studies found no difference in primary care utilization (Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Yu, et al., 2018; Schuster et al., 2018). No change in outpatient subspecialty clinic visits were noted in both studies that looked at this outcome (Druss et al., 2017; Schuster et al., 2018).

Screening and Monitoring

Diabetes:

Five studies demonstrated a statistical increase in frequency of screening for hyperglycemia and/or presence of diabetes (Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Yu, et al., 2018; Druss et al., 2001; Druss et al., 2017; Gilmer et al., 2016; Tepper et al., 2017) associated with BHH implementation. One study also showed a significant increase in screening rates at one group of clinics but not at a second group of clinics studied (Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Yu, et al., 2018). In the three studies that reported on monitoring glycemic control in consumers with diabetes, one study found a statistically significant increase in monitoring (Druss et al., 2017) and one study found no statistical difference (Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Yu, et al., 2018). One state evaluation reported an increase in diabetes screening and monitoring but did not report level of statistical significance (Missouri HealthNet, 2017).

Dyslipidemia:

Two studies demonstrated a statistically significant increase in screening rates for dyslipidemia (by measurement of total cholesterol and/or LDL) (Druss et al., 2001; Gilmer et al., 2016), while two studies demonstrated no change (Druss et al., 2017; Tepper et al., 2017). Similarly, one study demonstrated mixed results at two different groups of clinics studied (Breslau, Leckman-Westin, Yu, et al., 2018). One state evaluation of BHHs demonstrated an increase in cholesterol screening and monitoring but did not report level of statistical significance (Missouri HealthNet, 2017).

Blood Pressure:

Both RCTs demonstrated a significant increase in monitoring of blood pressure in consumers randomized to a BHH versus usual care (Druss et al., 2001; Druss et al., 2017). Similarly, a third study that looked at highly integrated care programs versus less integrated programs found a statistically significant increase in blood pressure monitoring in the highly integrated programs (Gilmer et al., 2016). A state evaluation reported an increase in percentage of consumers who have achieved blood pressure control but did not report level of statistical significance (Missouri HealthNet, 2017)

Other Preventative Services:

Screening rates for hepatitis and tuberculosis and receipt of preventative vaccinations (influenza, pneumococcal) were higher amongst consumers enrolled in BHHs compared with those randomized to usual care in one study (Druss et al., 2001). A significant increase in colon cancer screening was also seen in this group (Druss et al., 2001). One study reported a significant increase in number of BHH consumers receiving preventative services which included cancer screening and HIV screening, but did not provide specific breakdown by category (Druss et al., 2017).

Wellness and Healthy Lifestyle Promotion

Nutrition:

One study reported that consumers randomized to a BHH were more likely to receive education on nutrition compared with consumers randomized to usual care (Druss et al., 2001). A second RCT reported a significant improvement in delivery of preventative services, which included nutritional counseling related to hypertension and diabetes, but did not provide further detail (Druss et al., 2017). Finally, two state evaluations reported provision of nutritional education, but did not provide data to assess statistical significance (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017).

Weight management:

Weight management was addressed in significantly more consumers enrolled in a BHH compared with non-BHH consumers in one RCT (Druss et al., 2001). A second RCT included obesity screening as part of a preventative care bundle whose usage increased, but they did not provide further detail if obesity screening itself increased (Druss et al., 2017). Finally, two state evaluation reported an increase in weight/obesity counseling but did not report level of statistical significance (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017).

Physical activity:

Consumers randomized to a BHH were more likely to receive education related to exercise than consumers randomized to usual care (Druss et al., 2001). Similarly, consumers in a second RCT who were randomized to a BHH (versus usual care) were more likely to receive physical activity counseling as part of a preventative care bundle (Druss et al., 2017). Two state also reported an increase in education and wellness groups on physical activity for consumers enrolled in a BHH, but did not provide supporting data to assess statistical significance (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017).

Smoking Cessation:

One RCT found that consumers randomized to a BHH were more likely to receive education on smoking cessation than consumers randomized to usual care (Druss et al., 2001). Consumers in a second RCT were also more likely to receive smoking cessation as part of a preventative care bundle if they were randomized to a BHH versus usual care (Druss et al., 2017); however the statistical significance of this individual component could not be determined by available data. However, another observational study found no difference in the percentage of consumers who reported tobacco use between enrolled vs not-enrolled in a PBHCI program (Scharf et al., 2016). States reported increased education for tobacco cessation in BHH consumers compared with non-BHH consumers, but further data was not available for review (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017).

Other:

One RCT reported a significant increase in education surrounding advanced directives in consumers randomized to a BHH compared to usual care (Druss et al., 2001). A second RCT reported that consumers randomized to a BHH (versus usual care) were more likely to receive STI counseling, but did not report it as separate outcome (Druss et al., 2017).

Patient Reported Outcomes

Patient Satisfaction:

For consumers enrolled in a BHH compared with those not enrolled, patient satisfaction with overall medical care was significantly increased in one study (Druss et al., 2001). Patient satisfaction was also higher for those enrolled in a BHH compared with general medical patients in the same state, but statistical significance could not be determined (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015).

Patient Activation:

Two studies used the short-form Patient Activation Measure survey, a well-validated survey tool for evaluating a patient’s ability to self-manage chronic disease, through self-assessment of knowledge, skills, confidence, and motivation (Hibbard, Mahoney, Stockard, & Tusler, 2005). One study found a statistically significant increase in patient activation between patients randomized to a provider-supported care model versus a web-supported care model (Schuster et al., 2018). A second study found no difference between patients randomized to a BHH versus usual care (Druss et al., 2017).

Physical Health Outcomes

Self-Assessment of Physical Health:

Two studies reported a significant increase in perceived self-assessment of physical health with the BHH (Druss et al., 2001; Gilmer et al., 2016), and two studies reported no significant difference (Druss et al., 2017; Schuster et al., 2018). Three of these studies used either the physical health component summary score (Druss et al., 2001; Druss et al., 2017) or the abbreviated 12 item form (Schuster et al., 2018) of the Short-Form Health Survey, a validated measure of perceived health status (J. Ware, Jr., Kosinski, & Keller, 1996; J. E. Ware, Jr. et al., 1995). The fourth study used the Global Health Scale of the Patient Reported Outcome Measurement (Gilmer et al., 2016), an assessment system for self-reported health that encompasses physical, mental, and social health (Cella et al., 2010).

Diabetes:

No significant change in glycemic control (as measured by hemoglobin A1c, blood glucose) was seen in three studies (Druss et al., 2017; Scharf et al., 2016; Tepper et al., 2017). All three studies compared consumers enrolled in BHHs to usual care over the course of 1–3 years. At the population health level, Missouri BHHs increased the percentage of consumers with hemoglobin a1c values <8% from 18% in 2012 to 60% in 2017 (Missouri HealthNet, 2017)

Cholesterol:

One observational study reported a mean decrease by 35 mg/dL in total cholesterol, mean decrease by 35 mg/dL for LDL cholesterol, and mean increase by 3 mg/dL for HDL cholesterol in consumers at PBHCI clinics compared with usual care (Scharf et al., 2016). Importantly, these figures reflect group mean changes, as opposed to individual consumer changes, and it is unclear what the influence of loss to follow up had on the data. One state evaluation from the gray literature also reported a rise from 22% of enrolled consumers in February 2012 to 52% of enrolled consumers in December 2017 who have an LDL <100 mg/dL (Missouri HealthNet, 2017). One RCT and one observational study reported no significant change in cholesterol values (Druss et al., 2017; Tepper et al., 2017).

Blood Pressure:

One study demonstrated a statistically significant decrease by mean 5 mmHg in systolic blood pressure reading in consumers randomized to BHH versus usual care (Druss et al., 2017). Another study reported a mean 14 mm Hg decrease in systolic blood pressure, a change that was not statistically significant when compared to the control arm (Scharf et al., 2016). Diastolic blood pressure decreased by non-statistically significant changes in both studies (Druss et al., 2017; Scharf et al., 2016). Missouri BHHs reported 66% of enrolled consumers with blood pressure < 140/90 in 2017, compared with 27% in 2012. Details of how those blood pressure measurements were standardized were not available for review.

Weight Management:

No significant change in body mass index (BMI) was observed in consumers enrolled in a BHH versus usual care over 1 year (Scharf et al., 2016). However, in overweight or obese adult consumers enrolled in Missouri BHHs between 1–5 years, health home sites reported that 38% of their consumers lost weight from their first recorded weight to their most recent weight recording (Missouri HealthNet, 2017). Further detail of how these measurements were ascertained and standardized were not available for review.

Framingham Coronary Heart Disease Risk Score:

One study reported no difference in Framingham risk score between consumers randomized to BHH versus usual care after 12 months (Druss et al., 2017).

Costs

The state of Ohio reported an overall cost increase of $512 per member per month in their health home program, with much of the total cost of care (per member per month) being driven by pharmacy costs (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015). In contrast, the state of Missouri reported an average of $200 total cost of care savings per member per month after implementation of BHH (Missouri HealthNet, 2017). We note that Ohio data was calculated from a difference-in-difference analysis with populations matched by propensity score, while Missouri data was calculated pre and post-BHH at the individual consumer level. No significant difference was seen in cost per member per month for emergency room, inpatient, or outpatient utilization for consumers enrolled in a BHH compared to usual care (Krupski et al., 2016). Likewise, there was no significant difference in total cost of care per consumer for participants randomized to an integrated care versus usual care (Druss et al., 2001).

Implementation Barriers and Facilitators

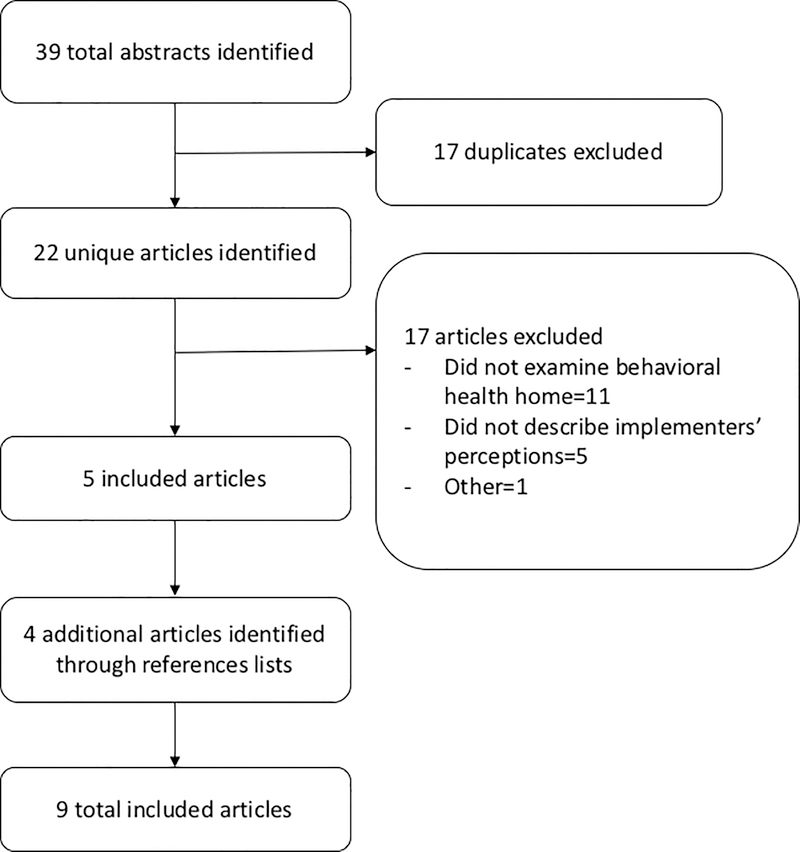

Our search strategy on implementation of BHHs yielded 9 unique articles. Of the 17 articles that did not meet inclusion criteria, most did not examine a BHH setting (n=11) or did not describe the perceptions of those in charge of implementation process (n=5) (Figure 2). In addition to the 5 unique articles identified in the initial search strategy, 4 additional studies were identified through reference lists. Of the nine articles, 4 were peer-reviewed studies (Annamalai, Tek, Sernyak, Cole, & Steiner, 2016; Maragakis & RachBeisel, 2015; McGinty et al., 2018; Scharf et al., 2013), 3 were gray literature reports from non-profit public policy research organizations (Golembieweski et al., 2015; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014), and 2 were gray literature reports from state Medicaid programs (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017).

Figure 2:

Literature flow diagram of implementation studies in behavioral health homes.

Study characteristics

Seven studies examined implementation of BHHs at multiple sites, of which two occurred across multiple states (Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013) and five occurred in single states (Golembieweski et al., 2015; Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; McGinty et al., 2018; Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014) (Table 3). Two studies looked at implementation at single sites (Annamalai et al., 2016; Maragakis & RachBeisel, 2015). Five out of nine implementation studies reported on BHH programs who had available outcome data described in the first section of this review (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013).

Table 3.

Designs of studies examining implementation of and partnerships formed within behavioural health homes.

| Study | Study Population | Partnerships | Information Source | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mental Health | Physical Health | |||

| Annamalai 2018 | Single site | Public urban community mental health center awarded Primary and Behavioral Health Care Integration (PBHCI) grant | Co-located primary and mental health care at a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) with 2 peer health navigators, nurse care manager, medical assistant, part-time nurse practitioner | First-person reports of medical directors and chief financial officer involved in the program. |

| Golembiewski 2015 | Single state, multi-site | Community mental health centers | Nurse care manager, care coordinator, peer support specialist, director | Interviews with site administrators and practice transformation coaches |

| Maragakis 2015 | Single site | University-based psychiatric clinic | Nurse practitioner, care manager | First-person perspective of the medical director of integrated clinic |

| McGinty 2018 | Single state, multi-site | Psychiatric rehabilitation programs (PRP) | Director, nurse care manager, primary care physician or nurse practitioner consultant (15% co-located) | Interviews with nurse care managers, PRP directors; survey with nurse care managers, PRP staff (e.g., care manager, counselors, peer leaders) |

| Missouri 2017 | Single state, multi-site | Community mental health clinics/agencies | Director, nurse care manager, care coordinator, primary care consultant (MD, PA, advanced practice nurse) | State-wide health home progress report, with interviews from 2013 and 2016 |

| Ohio 2015 | Single state, multi-site | Community behavioral health centers | Care manager, care management assistant, primary care provider (either full-time or part time primary care physician and/or nurse-practitioner | Interviews with internal and external stakeholders and health home providers |

| Scharf 2013 | Multi-state, Multi-site | Suburban or urban behavioral health centers with PBHCI grant | FQHC nurses, nurse practitioners, primary care physicians, case managers, and peer-specialists | Grant proposals, quarterly reports, interviews with core agency staff, iincluding program managers |

| Scharf 2014a | Multi-state, Multi-site | Behavioral health clinics and agencies awarded PBHCI grant | Co-located primary care delivered by MD overseeing NP or PA or RN; nurse care coordinators, non-nurse care coordinator, case manager, peer-specialists, wellness specialists | Surveys with administrators, primary care providers, mental health providers, care coordinators, peer mentors; quarterly reports from program sites, and site visits |

| Scharf 2014b | Single state, multi-site | Urban/rural community mental health centers, of which 23% had PBHCI grant | Co-located primary care with partnership with FQHC delivered by MD, NP/PA, RN, care managers | Site visits with interviews with staff, consumer; surveys of clinic administrators and providers |

By definition, all BHH programs were grounded in a mental health center. Co-location of mental health and primary care was directly described by four studies, although not every clinic within each study had this model (Annamalai et al., 2016; McGinty et al., 2018; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014). For sites without co-location of services, distance ranged from 1–9 miles in New York State (Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014) or not reported in all other studies.

The care providers who participated in the physical health partnership side within BHHs differed between studies and sites. Primary care was most often delivered by mid-level practitioner (nurse practitioner or physician assistant), followed by a physician. Care coordination was provided by care managers with a nursing background, ranging from 71–100% of the time (Annamalai et al., 2016; Golembieweski et al., 2015; McGinty et al., 2018; Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). All nine implementation studies discussed incorporation of wellness services and healthy lifestyle promotion and education into BHHs. This counseling was delivered to individuals and/or group settings by nurses, nurse practitioners, wellness specialists, peer navigators, and/or care managers (Annamalai et al., 2016; Golembieweski et al., 2015; Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Maragakis & RachBeisel, 2015; McGinty et al., 2018; Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013)

Perceived barriers and facilitators of BHH implementation were obtained from key stakeholders within the BHHs. Data was obtained from interviews (n=6), surveys (n=3), site visits (n=2), and first person perspectives (n=2). Interviews and surveys were conducted with clinic administrators, care managers, and staff.

Perceived Barriers and Facilitators of Behavioral Health Home Implementation

Administrative:

Communication with external administrative bodies were cited as a barrier by three studies (Table 4) (Golembieweski et al., 2015; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). Two studies cited frustration with governmental licensing issues and delays in approval to update billing capabilities (Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). The third study reported delays in communication and lack of program support between BHHs and a state-contracted health management company (Golembieweski et al., 2015). This lack of support was also thought to contribute to increased administrative workload (Golembieweski et al., 2015)

Table 4.

Perceived behavioural health home implementation barriers and facilitators.

| Perceived Facilitators (n studies) | Perceived Barriers (n studies) | |

|---|---|---|

| Administrative | Obtaining of licensing and approvals (2) (Scharf 2013, Scharf 2014b) Lack of support from health management company (1) (Golembiewski 2015) Upfront administrative load increase (1) (Golembiewski 2015) |

|

| Financial | Existing payment structures (1) (Maragakis 2015) | Inadequate insurance reimbursement (4) (Scharf 2013, Scharf 2014a, Scharf 2014b, Ohio 2015) Lack of affordability to consumers (1) (Annamalai 2018) Lack of short and long-term financial viability of behavioral health home programs (4) (Annamalai 2018, Scharf 2014a, Scharf 2014b, Ohio 2015) |

| External partners | Identification of existing community resources (3) (Annamalai 2018, Golembiewski 2015, Scharf 2014b) Prior experience with integrated care (1) Annamalai 2018) Shared vision for provision of care (1) (Annamalai 2018) Shared infrastructure(1) (Scharf 2014a) |

Challenges obtaining access to external providers (2) (Scharf 2013, Scharf 2014b) Lack of awareness of programs by external providers (1) (Ohio 2015) Challenges oordinating care with external providers (4) (Golembiewski 2015, McGinty 2018, Missouri 2017, Scharf 2014b) |

| Consumers | Identification of consumers by community partners (1) (Golembiewski) | Challenges with consumer recruitment (5) (Maragakis 2015, Golembiewski 2015, Ohio 2015, Scharf 2013, Scharf 2014a) Poor rates of participation and retention in program (6) (Annamalai, Scharf 2013, Maragakis, Golembiewski, Scharf 2014a, Scharf 2014b) |

| Staff | Updated trainings in response to feedback (Annamalai 2018, Ohio 2015) | Difficulty with recruitment/retention of staff (3) (Missouri 2017, Scharf 2013, Scharf 2014a) Unclear and shifting staff roles and responsibilities (2) (McGinty, Scharf 2014b) Insufficient training (4) (Golembiewski, Scharf 2013, Missouri 2015, Scharf 2014b) |

| Organizational factors | Geographical proximity of providers (2) (McGinty 2018, Scharf 2014a) Shared mission and values (4) (Annamalai 2018, Golembiewski 2015, McGinty 2018, Scharf 2014a) Institutional champions (1) (Scharf 2014b) |

Lack of physical program space (3) (Scharf 2013, Scharf 2014a, Scharf 2014b) Required change in organization mission (Golembiewski 2015) Limited capacity to deliver services (4) (Annamalai 2018, Golembiewski 2015, Scharf 2013, Scharf 2014a) |

| Information technology infrastructure | Shared databases and existing health information exchanges (HIEs) (3) (Maragakis 2015, McGinty 2018, Scharf 2014b) – | Challenges with data collection (1) (Scharf 2013) Challenges with implementing and usability of electronic health record (McGinty 2018, Scharf 2013) Challenges merging primary care and behavioral health protocols (1) (Scharf 2013) Lack of information sharing (5) (Golembiewski 2015, McGinty 2018, Missouri 2017, Ohio 2015, Scharf 2014b) Lack of ability to track outcomes (3) (Annamalai, Golembiewski, Scharf 2014a) |

Financial:

Financial barriers were discussed at the consumer and BHH level. At the consumer level, four programs discussed the need to ensure appropriate insurance reimbursement for care delivered and an efficient system to track this reimbursement across multiple states, payers, and consumers (Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). Another program also noted a desire to provide low cost, high quality care to patients for ancillary services, such as laboratory testing and screening tests. They worked to address these costs when developing their budget (Annamalai et al., 2016).

The overall viability of the BHH programs, particularly after initial grant funding ended, was of concern for many programs (Annamalai et al., 2016; Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014). One single-site program predicted its economic viability based on an estimated number of enrolled consumers who engaged in at least two health home services and expected state reimbursement (Maragakis & RachBeisel, 2015). One state-wide program tracked its potential cost savings pre and post-implementation (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015). BHH implementers were also mindful of changes in consumers’ insurance status and state-wide insurance regulations (Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014).

External Partners:

Studies reported that identification and use of existing community partnerships facilitated stronger relationships when implementing a BHH (Annamalai et al., 2016; Golembieweski et al., 2015; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014). Community partners that had prior experience with integrated care models, shared vision of how to provide care, or shared existing infrastructure were also viewed favorably (Annamalai et al., 2016; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014). For those BHHs without existing relationships, establishing new relationships, particularly with subspecialists, was viewed as challenging (Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). External awareness of behavioral health programs was viewed as low and this was thought to be an additional barrier (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015). Once partnerships were established, continued communication and coordination of care were identified as a consistent barrier (Golembieweski et al., 2015; McGinty et al., 2018; Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014).

Consumers:

Consumer engagement was viewed as a barrier to implementation of health homes in several cases. Consumer recruitment challenges were identified by five studies (Golembieweski et al., 2015; Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Maragakis & RachBeisel, 2015; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). Identification of potential consumers who might be a good fit for BHH participation by community partners was viewed as helpful to this process (Golembieweski et al., 2015). The results of one study suggested that consumers were unsure what integrated care models provided and may have therefore been reluctant to enroll (Golembieweski et al., 2015).

Retention of consumers in programs was identified as a key barrier in five studies (Annamalai et al., 2016; Golembieweski et al., 2015; Maragakis & RachBeisel, 2015; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). Two studies described scenarios of enrolled consumers who did not show up or were not reachable by phone (Maragakis & RachBeisel, 2015; Scharf et al., 2013). Lack of reliable transportation was also described as an explanation for low consumer retention (Annamalai et al., 2016; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014).

Staffing:

Difficulties surrounding recruitment and retention of BHH staff were described by three studies (Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013).. Qualitative work reported that staff members sometimes felt that their roles and responsibilities were unclear or inconsistent (McGinty et al., 2018; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014). They also were concerned for lack of leadership support, particularly during transition periods, leading to low morale (Golembieweski et al., 2015; Scharf et al., 2013).

Four programs noted insufficient training for staff as a barrier (Golembieweski et al., 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). Two studies described the ability to provide updated staff trainings in response to feedback or unexpected challenges and felt that this was beneficial (Annamalai et al., 2016; Health Services Advisory Group, 2015). Training with a focus on consumer-centered approaches and how best to serve the mental and physical health needs of consumers were also well received (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015)

Organizational Factors:

Two studies reported that availability of space for providers and maximizing existing space was an initial challenge (Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). However, space related issues often were able to be resolved within the first year (Scharf et al., 2013). When the BHH was co-located with primary care and/or providers were located near one another, this was viewed favorably (McGinty et al., 2018; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014). Co-location was perceived as facilitating greater communication between providers, but not necessarily guaranteeing effective coordination (McGinty et al., 2018).

In addition, the values, mission and existing capacity of the BHH influenced the perceptions of how well implementation was being performed. Having mutual values and shared sense of ownership amongst administrators and staff was reported to facilitate implementation (Annamalai et al., 2016; McGinty et al., 2018; Scharf et al., 2013). Institutional champions were cited as helpful in one study (Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014). When the mission of an existing organization fit the mission and actions of the BHH, this was viewed positively (Golembieweski et al., 2015; McGinty et al., 2018). However, when the mission changed or was unclear, this was reflected in frustration by staff (Golembieweski et al., 2015). Finally, BHH programs expressed concerns that their organization lacked the capacity to fulfill its mission and to deliver the services to its consumers (Annamalai et al., 2016; Golembieweski et al., 2015; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013). These concerns included insufficient space, lack of staff, changing of business model, and clinic workflow.

Information Technology Infrastructure:

Finally, all nine studies described barriers and facilitators for data management implementation, either at the consumer and/or program levels. Specific data management problems included meeting data collection requirements of grants (Scharf et al., 2013), implementing and working with an electronic health records (EHR) system (McGinty et al., 2018; Scharf et al., 2013), merging existing protocols between mental health and primary care (Scharf et al., 2013), and tracking consumer outcomes (Annamalai et al., 2016; Golembieweski et al., 2015; Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014). Information sharing across settings of care was a concern (Golembieweski et al., 2015; Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; McGinty et al., 2018; Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014). In some cases, presence of shared databases and existing health information exchanges were viewed as facilitators of implementation (Maragakis & RachBeisel, 2015; McGinty et al., 2018; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014).

Discussion

In our review of studies published between 2000 to 2018, the data on the effects of BHHs on utilization, screening and monitoring, wellness and healthy lifestyle promotion, patient-reported outcomes, physical health outcomes, and costs among consumers with SMI is limited and mixed. Studies varied in quality, inclusion criteria, rigor of comparison group, data collection procedures and outcomes measures. Importantly, two of the included studies (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; Missouri HealthNet, 2017) were not peer reviewed, but were instead reports published by the agency implementing the BHH program. Studies examining implementation showed wide variation in setting, care providers, and partnerships within BHHs. Despite variation in organizational structure, several common barriers and facilitators emerged across studies examining BHH implementation, including financing, information technology, organizational factors, and community partnerships.

Overall, the results of outcome evaluations to date suggest that BHHs are facilitating consumers to be seen more frequently in primary care and to be screened and monitored for cardiovascular-related conditions. This is likely a good first step to improving physical health in people with SMI, though results of our review suggest that these improvements in access, screening and monitoring have not resulted in significant improvements in physical health outcomes. While not all outcome evaluation studies specifically reported on wellness and lifestyle counseling, all implementation studies reported that education on wellness and healthy lifestyles is being incorporated into BHH implementation. However, it is not known to what degree evidence-based interventions are being used for healthy lifestyles (e.g., weight management). We were also unable to ascertain whether guideline-specific care processes were being used for management of dyslipidemia, hypertension or diabetes (American Diabetes Association, 2018; Stone et al., 2014; Whelton et al., 2018). Importantly, some BHH models are structured where a BHH nurse care manager coordinates care with external primary care providers in the community (McGinty et al., 2018). In this model, the BHH nurse does not have full autonomy to deliver the guideline-concordant care themselves, but rather depends upon the primary care provider to lead this process. This lack of control may impede delivery of guideline-concordant care (McGinty et al., 2018). Greater future understanding of BHHs’ effects on adherence to these established care metrics is necessary as it may help elucidate the limited and mixed physical health outcome results that have been reported to-date.

Other possible explanations for lack of significant improvement in physical health outcomes could be related to perceived barriers recognized during implementation: insufficient education (for staff or consumer) and poor health information technology infrastructure to support population health management. It is possible that outcomes improve as BHH implementation scales up over time. Missouri reports steady improvement over the past 5 years for percentage of BHH consumers who have reached target goals for cholesterol, glycemic, and blood pressure (Missouri HealthNet, 2017), but these improvements have been reported in evaluations lacking a comparison group.

Our review also identified gaps in outcomes related to the provision of preventative care. We note that only the two RCT studies reported BHHs’ effects on vaccination rates and cancer screening, despite the fact that cancer is among the leading cause of death in the SMI population after heart disease (Colton & Manderscheid, 2006; Daumit et al., 2010). We also found minimal evaluation of BHHs’ effects on health behavior change, e.g. smoking cessation, and patient-reported outcomes. Future studies are needed to address these gaps.

The generally mixed effects that we observed for physical health outcomes is not surprising given the variation in how BHHs are being implemented. Our results from the implementation studies demonstrated that some BHHs have mental health and primary care co-localized at the same site, while others did not. Similarly, primary care providers and care coordinators differed in roles and responsibilities across BHHs. No standardized format or protocols for implementation exist; health homes have different financing mechanisms, staffing structures, partnerships, and services provided, e.g. some BHHs focus primarily on care coordination (Gilmer et al., 2016; McGinty et al., 2018; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014) and others focus on primary care delivery in the BHH setting (Scharf et al., 2013; Scharf et al., 2016). For example, health homes funded under the ACA through state Medicaid programs created a Medicaid reimbursement mechanism for primary care coordination with existing community-based mental health organizations and did not include infrastructure funding, while BHHs funded from SAMHSA-sponsored PBHCI grants and were not tied to reimbursement and could be used to develop infrastructure (Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2016). While multiple studies have evaluated the PBHCI funded programs (Scharf, Eberhart, et al., 2014; Scharf et al., 2013; Scharf et al., 2016), rigorous evaluation is also needed of the BHH models implemented through the ACA health home waiver.

Similarly, we found that the clinical background (including nurse, nurse practitioner, physician) and training given to providers and front-line staff members in BHHs differed across BHH programs. For example, PBHCI grants included specific funding for trainings to support and expand staff in expanded roles within the clinic, while other funding sources were less explicit in what was included for staff training (Health Services Advisory Group, 2015; McGinty et al., 2018; Missouri HealthNet, 2017; Scharf, Breslau, et al., 2014). Evidence is lacking as to what constitutes an optimal skill set to achieve care coordination and ultimately, improved physical health outcomes in the SMI population.

Our review has important limitations. First, we did not systematically assess study quality. While we attempted to highlight differences in study design, observational outcome evaluations varied in quality of data reported, strength of comparator group, and whether a comparator group was included. Second, many studies reported population-level data. Thus, we are unable to draw conclusions about BHHs’ effects on outcomes of interest at the individual level. Finally, studies were set in geographically diverse locations and lessons learned may not be transferrable to all locations.

Taken together, this review underscores the diverse ways in which BHHs are being implemented and the potential of BHHs to improve physical health care delivery and outcomes for the SMI population. Limited data suggests that screening and monitoring is improving within BHHs; however, there is insufficient evidence regarding BHHs’ effects on delivery of guideline-concordant physical health care, and evidence is mixed regarding such programs’ effects on physical health outcomes. More research is needed to understand how BHHs implement guideline-concordant care and how they are affecting physical health outcomes in consumers with SMI.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

References

- Alexander L, & Druss B (2012). Behavioral Health Homes for People with Mental Health & Substance Use Conditions: the Core Clinical Features. Retrieved from https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/cihs_health_homes_core_clinical_features.pdf.

- American Diabetes Association. (2018). 5. Prevention or Delay of Type 2 Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2018. Diabetes Care, 41(Suppl 1), S51–s54. doi: 10.2337/dc18-S005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annamalai A, Tek C, Sernyak MJ, Cole R, & Steiner JL (2016). Integrated health care In Jacobs SC, Steiner JL, Jacobs SC, & Steiner JL (Eds.), Yale textbook of public psychiatry. (pp. 63–79). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Casalino LP, & Pincus HA (2013). Behavioral health and health care reform models: patient-centered medical home, health home, and accountable care organization. J Behav Health Serv Res, 40(1), 121–132. doi: 10.1007/s11414-012-9306-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadles CA, Farley JF, Ellis AR, Lichstein JC, Morrissey JP, DuBard CA, & Domino ME (2015). Do medical homes increase medication adherence for persons with multiple chronic conditions? Med Care, 53(2), 168–176. doi: 10.1097/mlr.0000000000000292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Leckman-Westin E, Han B, Pritam R, Guarasi D, Horvitz-Lennon M, Yu H (2018). Impact of a mental health based primary care program on emergency department visits and inpatient stays. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 52, 8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Leckman-Westin E, Yu H, Han B, Pritam R, Guarasi D, Finnerty MT (2018). Impact of a Mental Health Based Primary Care Program on Quality of Physical Health Care. Adm Policy Ment Health, 45(2), 276–285. doi: 10.1007/s10488-017-0822-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S (1997). Excess mortality of schizophrenia. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry, 171, 502–508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, Hays R (2010). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. J Clin Epidemiol, 63(11), 1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2018). Medical Health Homes: SPA Overview. Health Home Information Resource Center. Retrieved from https://www.medicaid.gov/state-resource-center/medicaid-state-technical-assistance/health-home-information-resource-center/downloads/hhs-spa-overview.pdf

- Colton CW, & Manderscheid RW (2006). Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis, 3(2), A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daumit GL, Anthony CB, Ford DE, Fahey M, Skinner EA, Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM (2010). Pattern of mortality in a sample of Maryland residents with severe mental illness. Psychiatry Res, 176(2–3), 242–245. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis K, Reedy W, & Little N (2013). Integrated illness management and recovery for older adults with serious mental illness. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 21(3), S20–S21. [Google Scholar]

- De Hert M, Detraux J, van Winkel R, Yu W, & Correll CU (2011). Metabolic and cardiovascular adverse effects associated with antipsychotic drugs. Nat Rev Endocrinol, 8(2), 114–126. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domino ME, Wells R, & Morrissey JP (2015). Serving persons with severe mental illness in primary care-based medical homes. Psychiatr Serv, 66(5), 477–483. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201300546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, & Goldman HH (2018). Integrating Health and Mental Health Services: A Past and Future History. Am J Psychiatry, appiajp201818020169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.18020169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, & Rosenheck RA (2001). Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry, 58(9), 861–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druss BG, von Esenwein SA, Glick GE, Deubler E, Lally C, Ward MC, & Rask KJ (2017). Randomized Trial of an Integrated Behavioral Health Home: The Health Outcomes Management and Evaluation (HOME) Study. Am J Psychiatry, 174(3), 246–255. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16050507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer TP, Henwood BF, Goode M, Sarkin AJ, & Innes-Gomberg D (2016). Implementation of integrated health homes and health outcomes for persons with serious mental illness in Los Angeles County. Psychiatric Services, 67(10), 1062–1067. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golembieweski E, Askelson NM, & Bentler SE (2015). Evaulation of the Integrated Health Home (IHH) program in Iowa: Qualitative interviews with site administrators. Iowa Research Online, 23. [Google Scholar]

- Health Services Advisory Group. (2015). Health Homes Performance Measures: Comprehensive Evaluation Report. Ohio. [Google Scholar]

- Hibbard JH, Mahoney ER, Stockard J, & Tusler M (2005). Development and testing of a short form of the patient activation measure. Health Serv Res, 40(6 Pt 1), 1918–1930. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00438.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz-Lennon M, Kilbourne AM, & Pincus HA (2006). From silos to bridges: meeting the general health care needs of adults with severe mental illnesses. Health Aff (Millwood), 25(3), 659–669. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.3.659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, Bettger JP, Kemper AR, Hasselblad V, Williams JW (2013). Improving patient care. The patient centered medical home. A Systematic Review. Ann Intern Med, 158(3), 169–178. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krupski A, West II, Scharf DM, Hopfenbeck J, Andrus G, Joesch JM, & Snowden M (2016). Integrating Primary Care Into Community Mental Health Centers: Impact on Utilization and Costs of Health Care. Psychiatr Serv, 67(11), 1233–1239. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangurian C, Newcomer JW, Modlin C, & Schillinger D (2016). Diabetes and Cardiovascular Care Among People with Severe Mental Illness: A Literature Review. J Gen Intern Med, 31(9), 1083–1091. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3712-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maragakis A, & RachBeisel J (2015). Integrated Care and the Behavioral Health Home: A New Program to Help Improve Somatic Health Outcomes for Those with Serious Mental Illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(12), 891–895. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Baller J, Azrin ST, Juliano-Bult D, & Daumit GL (2015). Quality of medical care for persons with serious mental illness: A comprehensive review. Schizophr Res, 165(2–3), 227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Kennedy-Hendricks A, Linden S, Choksy S, Stone E, & Daumit GL (2018). An innovative model to coordinate healthcare and social services for people with serious mental illness: A mixed-methods case study of Maryland’s Medicaid health home program. Gen Hosp Psychiatry, 51, 54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2017.12.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, & Olfson M (2016). The Relevance of the Affordable Care Act for Improving Mental Health Care. Annu Rev Clin Psychol, 12, 515–542. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-092936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missouri HealthNet. (2017). Missouri CMHC Healthcare Homes Progress Report. Missouri. [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer JW, & Hennekens CH (2007). Severe mental illness and risk of cardiovascular disease. Jama, 298(15), 1794–1796. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.15.1794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Gerhard T, Huang C, Crystal S, & Stroup TS (2015). Premature Mortality Among Adults With Schizophrenia in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(12), 1172–1181. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osborn DP, Wright CA, Levy G, King MB, Deo R, & Nazareth I (2008). Relative risk of diabetes, dyslipidaemia, hypertension and the metabolic syndrome in people with severe mental illnesses: systematic review and metaanalysis. BMC Psychiatry, 8, 84. doi: 10.1186/1471-244x-8-84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Chant D, & McGrath J (2007). A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry, 64(10), 1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf DM, Breslau J, Hackbarth NS, Kusuke D, Staplefoote BL, & Pincus HA (2014). An Examination of New York State’s Integrated Primary and Mental Health Care Services for Adults with Serious Mental Illness. Rand Health Q, 4(3), 13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf DM, Eberhart NK, Hackbarth NS, Horvitz-Lennon M, Beckman R, Han B, Burnam MA (2014). Evaluation of the SAMHSA Primary and Behavioral Health Care Integration (PBHCI) Grant Program: Final Report. Rand Health Q, 4(3), 6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf DM, Eberhart NK, Schmidt N, Vaughan CA, Dutta T, Pincus HA, & Burnam MA (2013). Integrating primary care into community behavioral health settings: programs and early implementation experiences. Psychiatr Serv, 64(7), 660–665. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharf DM, Schmidt Hackbarth N, Eberhart NK, Horvitz-Lennon M, Beckman R, Han B, Burnam MA (2016). General Medical Outcomes From the Primary and Behavioral Health Care Integration Grant Program. Psychiatr Serv, 67(11), 1226–1232. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster J, Nikolajski C, Kogan J, Kang C, Schake P, Carney T, Reynolds CF (2018). A payer-guided approach to widespread diffusion of behavioral health homes in real-world settings. Health Affairs, 37(2), 248–256. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.1115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar M, Aarons GA, O’Connell M, Davidson L, & Groessl EJ (2015). Mental Health Recovery in the Patient-Centered Medical Home. Am J Public Health, 105(9), 1926–1934. doi: 10.2105/ajph.2015.302683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TE, & Sederer LI (2009). A new kind of homelessness for individuals with serious mental illness? The need for a “mental health home”. Psychiatr Serv, 60(4), 528–533. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.4.52810.1176/ps.2009.60.4.528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, Wilson PW (2014). 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol, 63(25 Pt B), 2889–2934. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tepper MC, Cohen AM, Progovac AM, Ault-Brutus A, Leff HS, Mullin B, B LC (2017). Mind the gap: Developing an integrated behavioral health home to address health disparities in serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services, 68(12), 1217–1224. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201700063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschoner A, Engl J, Laimer M, Kaser S, Rettenbacher M, Fleischhacker WW, Ebenbichler CF (2007). Metabolic side effects of antipsychotic medication. Int J Clin Pract, 61(8), 1356–1370. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2007.01416.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker ER, McGee RE, & Druss BG (2015). Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(4), 334–341. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J Jr., Kosinski M, & Keller SD (1996). A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care, 34(3), 220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr., Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, & Raczek A (1995). Comparison of methods for the scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care, 33(4 Suppl), As264–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, Casey DE Jr., Collins KJ, Dennison Himmelfarb C, . . . Wright JT Jr. (2018). 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: Executive Summary: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Hypertension, 71(6), 1269–1324. doi: 10.1161/hyp.0000000000000066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.