Patients with depression are most commonly treated in primary care settings (Linde et al., 2015). However, most primary care patients referred for therapy do not actually initiate treatment (Mohr et al., 2006). Indeed, multiple barriers to initiating or maintaining face-to-face interventions prevent many with depression from receiving care (Gonzalez et al., 2010). Therefore, alternative delivery mechanisms are increasingly being explored as a means to deliver care to patients with depression.

Smartphone apps are being developed and deployed as an avenue for delivering psychological interventions to those with depression (Shen et al., 2015). Apps show promise as a delivery mechanism for a number of reasons. Their presence within a mobile device ensures that users tend to have access throughout the day. This accessibility provides opportunities for real-time monitoring, assessment, and interventions in the real-world conditions of an individual with depression (Proudfoot, 2013). Additionally, about three-quarters of all Americans own a smartphone (Smith, 2017), increasing the possible reach of interventions delivered via apps. This reach also extends to groups which are more likely to experience stigma-related or practical barriers to traditional treatment delivery (e.g., minorities and low income users; Gonzalez et al., 2010). Apps for depression therefore have the potential to increase the accessibility and reach of psychological interventions for primary care patients with depression.

The majority of currently available apps for depression that provide an intervention (as opposed to solely monitoring or providing psychoeducation) are informed by behavioral and cognitive intervention strategies (Shen et al., 2015). Behavioral and cognitive interventions carry the strongest body of evidence in the face-to-face administration of treatments for depression (Cuijpers et al., 2013), and are generally believed to have equivalent efficacy when delivered face-to-face (Richards et al., 2016). However, this efficacy cannot be assumed to remain consistent when delivered through the new medium of apps.

Complicating the unknown efficacy of behavioral and cognitive interventions when delivered via apps is typically low app use. Even when prescribed by a healthcare provider, mental health apps have the lowest sustained rate of use after 30 days, compared to any other health and wellness apps (IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics, 2015). Further, the modal use of apps in a publicly-available group of behavioral and cognitive intervention apps was one use (Lattie et al., 2016). However, the relationship between use and symptom outcome has not been fully defined (Donker et al., 2013). Evaluating the use of apps for depression may provide insights into subsequent outcomes for this delivery mechanism.

The aim of the current study is to evaluate the feasibility of a larger trial of apps for depression. Specifically, the current study pilots: 1) recruitment procedures, 2) assessment procedures, 3) app usage, 4) coaching, and 5) efficacy evaluation.

Method

Participants

Recruitment of participants occurred from September 2015 to January 2016 from online ads posted in major American cities on Craigslist. Craigslist was used as the only online recruitment platform, as it is: 1) free, 2) reaches major American cities, and 3) ensured that recruitment reflected the growing number of people who seek help through the Internet. Participants were eligible if they: 1) had a minimum score of 10 on the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002), a widely held cut-off utilized in primary care settings; 2) had a minimum score of 11 on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptoms (QIDS; Rush et al., 2003), the cutoff for moderate depression; 3) were able to speak and read English; 4) were at least 18 years old; 5) owned an Android phone (as Android comprises the largest percent of the market); 6) had no visual, hearing, voice, or motor impairment; 7) were not diagnosed with a comorbid diagnosis for which participation in this trial was either inappropriate or dangerous (e.g., psychotic, bipolar, or dissociative disorders, substance dependence); 8) were not severely suicidal (i.e., ideation, plan, and intent); 9) were not receiving psychotherapy; and 10) were on a stable dose of an antidepressant medication (i.e., no dose changes for four weeks and did not intend to change the dose) or were not currently on an antidepressant medication.

In compliance with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, those found eligible following screening (i.e., an online survey assessing if potential participants were >17 years old, owned an Android phone, and were not diagnosed with a diagnosis of exclusion, such as Bipolar Disorder) were invited to participate in a baseline eligibility phone assessment. Prior to the phone interview, participants were emailed a link to the detailed digital version of the study consent form. Subjects agreed to participate in the study by checking a “yes” box and typing in their name. After the study consent form was signed online, and before completing the phone assessment, detailed information regarding the consent was reviewed with the participant by study staff.

Treatments

Randomization was created using PROC PLAN in SASv9.2, with participants randomly assigned in randomization blocks of six to either Boost Me (n = 10), Thought Challenger (n = 10), or waitlist control (n = 10). The randomized block design was used to ensure equal numbers were randomized to each group at a given time, should the study end early, or if there were seasonal effects. Once generated, this list was uploaded to Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), where study personnel were blinded to allocation prior to randomization, and participants would be randomized once eligibility was determined. The apps were developed by the Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies (CBITs; Lattie et al., 2016), and unlike other apps on the market, were selected for being free of cost, and complying with empirically-supported behavioral and cognitive intervention strategies. Boost Me and Thought Challenger participants received six weeks of weekly coaching sessions, didactic content delivery (one lesson per week), and use of the app (emailed to participants via an attachment they downloaded directly to their phones). The waitlist control group did not receive any intervention until the passage of 10 weeks occurred, to account for both the intervention period (six weeks) and follow-up period (four weeks). Following their completion of the final assessment, waitlist control participants were given access to both apps.

Boost Me

Boost Me is an Android app based upon activity scheduling, a core strategy of BA, which aims to increase rewarding activities and monitoring of mood in relation to behavior (J. S. Beck, 2011). Boost Me included a persistent notification (i.e., a small box in the Android notification tray that would remain visible throughout the day) to prompt users to reflect if they “Need a Boost?”. Boost Me is currently publicly available without cost.

Thought Challenger

Thought Challenger is an Android app based upon thought restructuring, the core strategy in Cognitive Therapy (CT) that involves identifying and appraising maladaptive thoughts and creating adaptive counter thoughts (J. S. Beck, 2011). Thought Challenger has demonstrated efficacy in improving CT knowledge and skills following initial use, as established through previous usability testing (Stiles-Shields et al., 2017). Unlike Boost Me, Thought Challenger was not designed to have a persistent notification in the Android notification tray. Thought Challenger is currently publicly available without cost.

Coaching

Participants randomized to Boost Me or Thought Challenger received weekly coaching via phone or email. Email was utilized as a means of contact if: 1) the participant was unable to be reached via phone, or 2) the participant requested email contact for a given week. Coaching was based on the supportive accountability model, which proposes that coaches increase adherence to apps by providing accountability in the context of a supportive relationship (Mohr, Cuijpers, & Lehman, 2011). The first coaching call involved asking the participant to open the app during the call to discuss the app features. All coaching calls were brief (i.e., typically five minutes or less) and were aimed at maintaining engagement with the app, and not in providing therapeutic intervention (e.g., “How could you use the app this week to help your mood?” “What would be a good goal for using the app this week?”). The same master’s level licensed clinician provided coaching to all participants in the trial.

Assessment

The baseline assessment interview was conducted via telephone. To maximize blinding, only self-report measures were administered beyond the baseline assessment. Self-report assessments occurred at baseline, weeks 3 and 6 (mid- and end-of-treatment), and at week 10 (one-month post-treatment follow-up) via REDCap, electronic data capture tools hosted at the University (Harris et al., 2009). Assessments were spaced in this way to minimize possible assessment burden for participants. Participants were compensated $15 and $10 for the baseline and follow-up assessments, respectively.

Measures of Psychological Characteristics

The PHQ-9 is a self-report instrument measuring depressive symptomology (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002), administered at all time points. The PHQ-9 was selected as the primary outcome measure due to its frequent use in primary care to screen for and monitor depression, enhancing generalizability to primary care settings.

The QIDS is a 16-item interview intended to evaluate objective, evaluator-rated symptom severity (Rush et al., 2003). The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) is a structured diagnostic interview to diagnose Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV (DSM-IV) and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) psychiatric disorders (Sheehan et al., 1997). The QIDS and MINI were administered at baseline to assess whether the depressive symptoms had been present for at least two weeks and determine eligibility based upon possible comorbid conditions that would make participation in the trial inappropriate, respectively.

Measure of Usability

The System Usability Scale (SUS) is a self-report instrument measuring a user’s rating of a product’s usability (Brooke, 1996) and was administered at weeks 3 and 6 for the Boost Me and Thought Challenger participants.

Safety Protocol

To ensure participant safety, any participant rating higher than “1: Several Days,” on item 9 of the PHQ-9 (i.e., “Thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself”) was prompted to also answer the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), item 9 (i.e., “Suicidal Thoughts or Wishes”; A. T. Beck, Ward, Mendelson, Mock, & Erbaugh, 1961). Participants then received a notification that the response would be reviewed within one business day and that s/he should go to the nearest emergency department or call 911 in the case of an emergency. If a participant rated a “2” or higher on the BDI item, study staff were notified by REDCap to trigger an administration of the Columbia-Suicide Risk Assessment via telephone (Posner et al., 2011). Any participants with severe suicidality (i.e., ideation, plan, and intent) were excluded.

Data Analysis

Baseline demographic variables were compared across treatment arms using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and chi-square tests of association. A repeated measures ANOVA was conducted to examine depressive symptoms over time and across treatment groups. Participants with missing data were eliminated casewise. t-Tests were conducted to compare usage and perceptions of usability across apps. Any participants without usage (e.g., launch of the app) or engagement with the coach were included in the analyses, as that is a representation of their total usage of these services. To examine the relationship between usage and change in depressive symptoms, bivariate correlations were run between the usage variables and change in depression between baseline and end of treatment. Bivariate correlations were run among the number of coaching sessions and duration of calls, usage variables, and change in depression between baseline and end of treatment (week 6). All analyses were run in IBM SPSS Statistics (v23), at the nominal 0.05 type I error rate. Post hoc tests were run using a Bonferroni correction to prevent inflation of the overall type I error rate.

Results

Participants

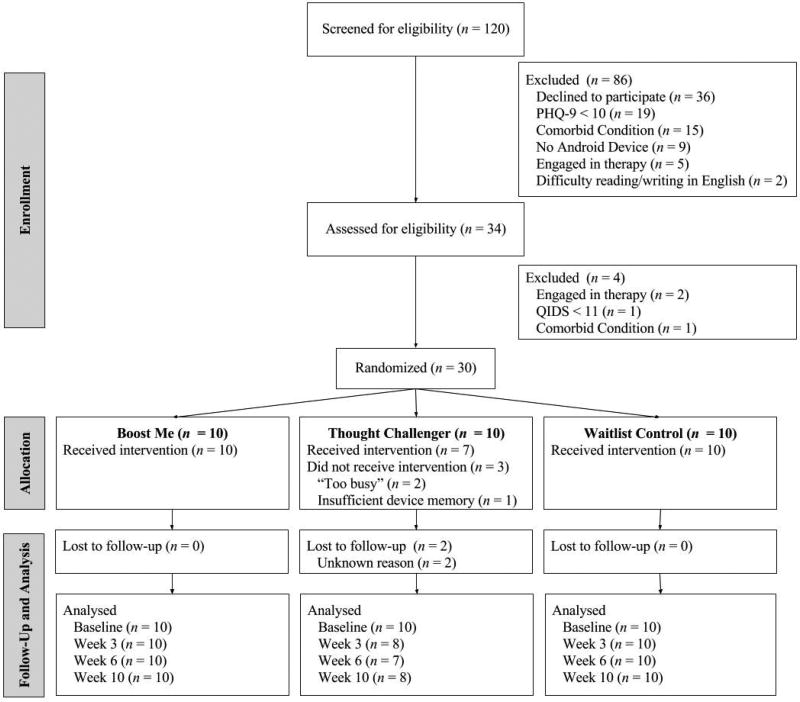

The flow of participants through this study is displayed in Figure 1. There were no significant differences in demographics across treatment groups at baseline. All Boost Me participants received the intervention. Three Thought Challenger participants did not receive the intervention; one reported not having enough device memory to download the app, and two were unresponsive to contact following randomization. There were no adverse events (e.g., severe suicidality).

Figure 1. Flow of Participants Through the Trial.

Note. PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire-9; QIDS = Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomology.

Depression Scores

Table 1 displays depression scores over time and across groups. The results of a repeated-measures ANOVA indicated that PHQ-9 scores changed significantly over time (F(3) = 31.83, p < .001, η2 = .19), and were significantly different based upon group assignment (F(6) = 2.78, p = .02, η2 = .18).

Table 1.

Depression Scores Over Time Across Groups, M(SD)

| Baseline | Week 3 (Mid) | Week 6 (EOT) | Week 10 (FU) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boost Me | 15.20 (5.49) | 9.60 (4.86) | 6.60 (3.95) | 8.90 (5.88) |

| Thought Challenger | 17.00 (4.62) | 6.14 (3.02) | 3.43 (3.82) | 5.29 (4.46) |

| Waitlist Control | 16.10 (3.76) | 13.60 (5.91) | 11.30 (5.58) | 11.50 (4.25) |

Note. M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation; EOT = End of treatment; FU = Follow-up.

Time

Baseline PHQ-9 scores were significantly higher than any other time point (ps < .001). Mid-treatment (week 3) and end of treatment (week 6) PHQ-9 scores demonstrated a decrease in severity over time, with significant differences emerging between these time points (p = .02). Follow-up (week 10) PHQ-9 scores showed an increase in symptoms, with no evidence to suggest differences between scores at follow-up, compared to mid and end of treatment (ps > .9).

Group

Post hoc analyses with a Bonferroni correction indicated significant differences in PHQ-9 scores over time between Thought Challenger and waitlist control participants (p = .03). There was no evidence to suggest differences in PHQ-9 scores among Boost Me participants and the other two groups (ps > .2).

Usage

Boost Me was launched significantly more than Thought Challenger (97.7 vs. 33.5, t(18) = 2.59, p = .02, d = 1.16). No significant differences emerged in the number of events (Boost Me; 14.7 ± 10.1) and thoughts (Thought Challenger; 8.5 ± 11.6) logged overall (p = .22, d = .57), nor in event (7.5 ± 7.3) or thought (5.4 ± 4.5) reviews (p = .45, d = .35).

Usage and Depression

App usage was not significantly correlated with changes in depression scores, either within the entire sample (i.e., Boost Me and Thought Challenger totals) or by group (e.g., only Boost Me totals; ps > .05).

Usability

Mid-treatment (week 3) mean SUS scores indicated that Thought Challenger (84.10 ± 10.43) was rated significantly higher than Boost Me (70.00 ± 14.31; t(15) = −2.29, p = .04, d = 1.12). However, at end of treatment (week 6), there was no significant difference in mean SUS scores between Thought Challenger (88.57 ± 5.56) and Boost Me (78.33 ± 15.10; t(14) = −1.70, p = .11, d = .90).

Coaching

Use of phone and email contact did not significantly differ between Boost Me and Thought Challenger participants, with the exception of week 5 in which Boost Me had a higher percentage of phone contact (70.0% vs. 11.1%, χ2(1,19) = 6.74, p = .009, ϕ = .60). There was no evidence to suggest a difference in the number or duration of coaching calls (Boost Me = 6.20 ± 3.30 minutes; Thought Challenger = 4.27 ± .83 minutes), and the length and number of coaching calls were not significantly correlated with app usage (ps > .05).

Discussion

The present study piloted an evaluation of the employment of apps as delivery mechanisms for behavioral and cognitive intervention skills. The current study supported the feasibility of conducting a randomized controlled trial evaluating mobile apps for depression, including online recruitment, retention, and engagement with apps and coaching. Thought Challenger showed a significantly greater impact on depressive symptoms, whereas Boost Me produced significantly greater usage. Of note, depressive scores increased during follow-up, but these differences were not significant. These finding should be interpreted cautiously, however, given the small sample size, which can increase the likelihood of spurious outcome findings.

The high usage of Boost Me, with an average number of app launches of nearly 100 over six weeks, stands in contrast to much lower usage patterns of Thought Challenger, and open access apps without human support (Lattie et al., 2016). There are multiple possible explanations for this amount of use that may be considered to promote usage in similar apps. First, users are encouraged to use the app twice: 1) to schedule the activity and 2) to rate how the activity actually impacted their mood. This promotion of two uses is in contrast to Thought Challenger’s single use when restructuring a thought. However, while this design may explain some increase in use, actual use indicates that about half of the planned boosts only resulted in one use of the app. Second, Boost Me had a persistent notification, which may have prompted increased use. Finally, Boost Me was designed to promote positive behaviors, with the aim of providing an immediate improvement in mood. These behaviors include self-generated and auto-generated suggestions. In contrast to Thought Challenger, the design of Boost Me may promote reliance upon the app to select rewarding behaviors to engage in when in a lowered mood state, promoting frequent and ongoing use of the app. There are multiple aspects of the design of Boost Me that may have influenced higher usage patterns than Thought Challenger, or similar publicly-available intervention apps.

Limitations of the current work should be considered in the interpretation of these findings. First, as a pilot trial, the sample size was small. Small samples are typically underpowered to identify significant effects, and can also introduce potential sampling biases. However, the effect sizes associated with the findings were generally medium to large. Attrition was also low (≤10% at all time points), demonstrating the feasibility of executing a larger trial evaluating apps for depression. However, all of the missing data occurred in one treatment arm, Thought Challenger. Second, the same person performed the roles of investigator, assessor, and coach, increasing the likelihood of investigator bias impacting the evaluation of clinical symptoms. While all follow-up assessment time points were conducted via self-report questionnaires to limit investigator bias, these findings were not cross-validated through objective assessment. Third, Craigslist was the sole recruitment method, necessitating 120 participant screens over four months’ time to achieve the sample size of 30. It is likely that other methodologies may be more effective in timely recruitment for mental health app research. Finally, it should be emphasized that these were coached interventions; the findings likely would not generalize to use without human support. While coaching may be expected in deployment through healthcare settings, it would be unusual for public deployment through app stores.

The findings of the present study indicate that intervention strategies for depression delivered via apps may impact symptomology and promote continued use over six weeks. The current study demonstrates the feasibility of future research regarding the delivery of intervention strategies via apps, and how this delivery mechanism may overcome barriers to care for primary care patients with depression.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health R01 MH100482 (PI: Mohr) and F31 MH106321 (PI: Stiles-Shields). This project was also supported by NIH/NCRR Colorado CTSI Grant Number UL1 RR025780. Its contents are the authors’ sole responsibility and do not necessarily represent official NIH views. Dr. Mohr also receives honoraria from Optum Behavioral Health and has an ownership interest in Actualize Therapy Ltd.

Contributor Information

Colleen Stiles-Shields, Department of Psychology, Loyola University Chicago and Department of Preventive Medicine and Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Enid Montague, College of Computing and Digital Media, DePaul University and Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Mary J. Kwasny, Department of Preventive Medicine and Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

David C. Mohr, Department of Preventive Medicine and Center for Behavioral Intervention Technologies, Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine

References

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck JS. Cognitive behavior therapy. Second. New York: Guilford Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Brooke J. SUS: A "quick and dirty" usability scale. In: Jordan PW, Thomas B, Weerdmeester BA, editors. Usability evaluation in industry. London, UK: Taylor & Francis; 1996. pp. 189–194. [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers P, Berking M, Andersson G, Quigley L, Kleiboer A, Dobson KS. A meta-analysis of cognitive-behavioural therapy for adult depression, alone and in comparison with other treatments. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;58(7):376–385. doi: 10.1177/070674371305800702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donker T, Petrie K, Proudfoot J, Clarke J, Birch MR, Christensen H. Smartphones for smarter delivery of mental health programs: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2013;15(11):e247. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez HM, Vega WA, Williams DR, Tarraf W, West BT, Neighbors HW. Depression care in the United States: Too little for too few. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):37–46. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMS Institute for Healthcare Informatics. Patient adoption of mHealth: Use, evidence and remaining barriers to mainstream acceptance. Parisppany, NJ: 2015. Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatric Annals. 2002;32(9):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Lattie EG, Schueller SM, Sargent E, Stiles-Shields C, Tomasino KN, Corden ME, Mohr DC. Uptake and usage of Intellicare: A publicly available suite of mental health and well-being apps. Internet Interventions. 2016;4(2):152–158. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linde K, Sigterman K, Kriston L, Rucker G, Jamil S, Meissner K, Schneider A. Effectiveness of psychological treatments for depressive disorders in primary care: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Family Medicine. 2015;13(1):56–68. doi: 10.1370/afm.1719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Cuijpers P, Lehman K. Supportive accountability: A model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2011;13(1):e30. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr DC, Hart SL, Howard I, Julian L, Vella L, Catledge C, Feldman MD. Barriers to psychotherapy among depressed and nondepressed primary care patients. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2006;32(3):254–258. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3203_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, Brent DA, Yershova KV, Oquendo MA, Shen S. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot J. The future is in our hands: The role of mobile phones in the prevention and management of mental disorders. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;47(2):111–113. doi: 10.1177/0004867412471441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards DA, Ekers D, McMillan D, Taylor RS, Byford S, Warren FC, Finning K. Cost and Outcome of Behavioural Activation versus Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Depression (COBRA): a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2016;388(10047):871–880. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31140-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Ibrahim HM, Carmody TJ, Arnow B, Klein DN, Keller MB. The 16-Item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), clinician rating (QIDS-C), and self-report (QIDS-SR): A psychometric evaluation in patients with chronic major depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2003;54(5):573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Janavs J, Weiller E, Keskiner A, Dunbar GC. The validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI) according to the SCID-P and its reliability. European Psychiatry. 1997;12(5):232–241. [Google Scholar]

- Shen N, Levitan MJ, Johnson A, Bender JL, Hamilton-Page M, Jadad AA, Wiljer D. Finding a depression app: A review and content analysis of the depression app marketplace. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2015;3(1):e16. doi: 10.2196/mhealth.3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. Record shares of Americans now own smartphones, have home broadband. Washington, D.C.: 2017. Retrieved from : http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/01/12/evolution-of-technology/ [Google Scholar]

- Stiles-Shields C, Montague E, Lattie EG, Schueller SM, Kwasny MJ, Mohr DC. Exploring user learnability and learning performance in an app for depression: Usability study. JMIR Human Factors. 2017 doi: 10.2196/humanfactors.7951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]