Abstract

Associations between parent critical attitudes (a component of the Expressed Emotion construct) and behavior problems have been relatively well established in adolescents and young adults with ASD, but use of systems adapted for children with ASD and additional investigations with younger samples are needed. The current study examined parental criticism, derived from a population-specific coding system, as related to behavior problems in children with ASD between the ages of 4 and 11 years, and considered parental warmth and children’s psychophysiological reactivity as statistical moderators of these associations. Forty children with ASD and their primary caregivers attended a visit involving collection of child electrodermal activity (EDA), parent-child interaction, a parent interview from which critical attitudes and warmth were coded, and parent report of child behavior problems. Criticism was directly related to higher child externalizing but not internalizing problems. Parental criticism interacted with warmth in the prediction of internalizing problems such that criticism was only associated with more problems in the context of moderate but not high warmth. Criticism was positively associated with externalizing problems under conditions of moderate and high, but not low, child EDA reactivity. Implications for conceptualizations of parental criticism in ASD, for understanding comorbid behavior problems in this population, and for intervention are discussed.

Keywords: autism spectrum disorder (ASD), expressed emotion, criticism, electrodermal activity, behavior problems

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder involving significant challenges in social communication and the presence of restricted and/or repetitive behaviors (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). It is generally agreed that the early social environment in-and-of-itself is not the cause of, or even necessarily a contributor to, the development of ASD (Dawson, 2008), and few substantial differences have been identified in the parenting of children with and without ASD (e.g., Baker et al., 2010b, Campbell et al., 2015). There is, however, evidence that certain aspects of parent-child interaction may predict beneficial outcomes in children with or at-risk for ASD, including those closely aligned with ASD criteria such as language ability and empathy (Baker et al., 2010b; McDonald et al., 2016).

In addition to significant variation in the degree and manifestation of core symptomatology, associated difficulties are common in children with ASD (Simonoff et al., 2008), including externalizing problems such as aggression, non-compliance, and disruptiveness (McClintock et al., 2003; Tonge et al., 1999), and internalizing problems including anxiety and depression (Kim et al., 2000; White et al., 2009). These difficulties may combine with ASD symptoms in an additive or even interactive manner to impede functioning and cause distress (Matson and Nebel-Schwalm, 2007; White et al., 2009). Theory in developmental psychopathology and research to date involving children with neurotypical development (McLeod et al., 2007; Rothbaum and Weisz, 1994) and those with disabilities other than ASD (Baker et al., 2010a; Fenning et al., 2014) have supported the notion that parenting can contribute to behavior problems, either directly or in combination with certain child characteristics. While several studies have examined specific parenting behaviors (Baker et al., 2010b, 2018; Campbell et al., 2015) and the larger family system (Baker et al., 2011a; Cridland et al., 2014) in relation to behavior problems in ASD, there has also been a particular interest in capturing certain parent attitudes and the emotional quality of the parent-child relationship.

Parent Emotional Attitudes

The construct of Expressed Emotion (EE) has a long history in the study of the caregivers of individuals with increased needs, initially focusing on caregivers of adults with schizophrenia and then expanding to other high-stress caregiving situations (Hooley, 1998; Peris and Miklowitz, 2015, Romero-Gonzalez et al., 2018, Sher-Censor, 2015). To assess EE, a caregiver is interviewed (Vaughn and Leff, 1976), or now more commonly asked to provide an uninterrupted Five Minute Speech Sample (FMSS; Magaña et al., 1986), about the child and his or her relationship with the child, in order to code for attitudes reflecting criticism and emotional over-involvement. The latter component has demonstrated poor validity when extending this research to the caregiving of children in general and those with disabilities specifically (Baker et al., 2011b; Peris and Miklowitz, 2015, Romero-Gonzalez et al., 2018; Sher-Censor, 2015). In constrast, criticism does seem to relate to behavior problems in ASD (see Romero-Gonzalez et al., 2018), with findings rendered especially compelling by longitudinal research designs involving careful controls. Utilizing cross-lagged panel and growth-curve analyses over time in a single sample of families of adolescents and adults with ASD (ages 11 to 48 years), Greenberg et al. (2006) and Baker, et al. (2011b) demonstrated not only consistent concurrent associations between these factors, but evidence of directionality as well, with caregiver criticism appearing to lead to behavior problems at this point in the family lifespan rather than vice-versa. Findings supporting the causal role of criticism in relation to behavior problems have been replicated with older children and adolescents with ASD (mean age 13 years; Bader and Barry, 2014); however, Hastings et al. (2006) did not find longitudinal associations between criticism and behavior problems in their mixed sample of children ages 3 to 19 years that also included children without ASD. Additional research is needed to clarify this relation in younger children with ASD.

Early EE rating systems (Vaughn and Leff, 1976) incorporated an additional component, parental warmth toward the child, which has not typically been included in more recent research. Existing work in ASD focused on warmth derived from EE codes has largely been completed by Mailick, Greenberg, and colleagues. Using a sample of families of adolescents and adults with ASD, significant prediction to behavior problems over time was not initially observed through cross-lagged designs (Smith et al., 2008); however, subsequent latent-class analyses suggested that warmth may be important in promoting physical and mental health in individuals with ASD (Bishop-Fitzpatrick et al., 2016), and may relate to healthier trajectories of internalizing and externalizing symptoms over time (Woodman et al., 2016).

While many researchers have addressed issues related to the relevance and validity of EE in ASD by examining certain components such as criticism or warmth in isolation, Benson and colleagues (Benson et al., 2011; Daley and Benson, 2008) adapted the original FMSS system (Magaña et al., 1986) and the related version for preschool-aged children (Daley et al., 2003), for use specifically with caregivers of children with ASD. The resulting Autism Five-Minute Speech Sample system (AFMSS; Daley and Benson, 2008) demonstrates many similarities with the original FMSS, but includes certain considerations related to the expression of criticism, and the addition of an explicit global code for warmth. Benson et al. (2011) presented initial psychometric support for the AFMSS, including good to excellent test-rest and inter-rater reliabilities, and concurrent validity with several indices of child functioning and with family cohesion. Subsequent studies have examined components of the AFMSS as they relate to additional child social factors (Benson, 2013) and as an outcome of intervention (Maughan & Weiss, 2017), and the AFMSS has been discussed in recent reviews focused on EE and psychopathology in ASD (Romero-Gonzales et al., 2018), the FMSS in developmental research (Sher-Censor, 2015), and measures of family functioning in ASD (Wainer et al., 2017).

The current study utilized the AFMSS, but remained focused on the subcomponents of criticism and warmth, given existing evidence of relatively powerful associations for these subcomponents against the background of continued debate about the utility of the overall EE construct for families of children with ASD (see Baker et al., 2011b). Indeed, Benson et al. (2011), reported no association between overall EE and problem behavior in their sample of families of children with ASD, whereas the relevant correlation with the subcomponent of warmth was significant. Interestingly, this study did not find the expected association between critical comments and parent-reported child behavior problems, requiring further study of the AFMSS in an additional sample and with an alternate measure of behavior problems.

Criticism-Parent Behavior Links

Although criticism is coded indirectly through parent narrative, scores derived from the original EE systems correspond with behavioral observations of criticism and interactive negativity in families (see Hooley, 1998; McCarty et al., 2004), leading some to conclude that EE-based criticism is a reasonable index of problematic family interaction (McCarty et al., 2004). To our knowledge, however, no study has established links between the AFMSS and parent-child interactive behaviors, which would lend additional construct validity to this system. The current study examined the association between AFMSS-based criticism and observed parent-child attunement as measured during a laboratory free-play. Attunement is a dyadic construct, driven significantly by child behavior, thus we expected a modest but significant association between AFMSS critical attitudes and this parent-child interaction factor.

Moderators of Criticism-Behavior Problem Links

The current study examined associations between parental criticism and behavior problems in children with ASD (4 to 11 years, mean: 6 years) utilizing the recently developed AFMSS. In addition to examining direct associations, we also considered the possibility that criticism may be differentially associated with child outcomes based on other parent or child factors. First, although many studies have considered the individual components of EE, or combined them into broad EE categories, specific interactions between criticism and warmth have not been investigated. These factors are inversely correlated in the AFMSS, but the association is not large (e.g., r = −.31 in Benson et al., 2011), and positive and negative emotional elements of parenting are often considered independently (see Fenning et al., 2007). It has been argued that increased criticism may be an understandable reaction to the high degree of challenge presented in the parenting of a child with significant disability, but that elevated levels of criticism may nonetheless remain detrimental to child functioning and outcomes (Hastings and Lloyd, 2007). Baker et al. (2011b) further argued that criticism, which is typically expressed in order to coerce a child into changing his or her behavior, may in some cases correlate with higher parental expectations for children with ASD.

Although we are not aware of any studies on the potential for positive family factors to buffer the effects of EE-based criticism specifically, theory and research in child development suggest that the effects of certain control strategies may be moderated by positive aspects of parenting. Findings are inconsistent (Landsford et al., 2014), but there is some evidence that parental warmth may buffer children from certain negative effects of harsh discipline (e.g., Deater-Deckard et al., 2006). Well-known categories of generally beneficial and less beneficial parenting styles both involve high demands for behavioral compliance, but differ in that only the former is accompanied by high responsiveness toward the child (Maccoby and Martin, 1983). Indeed, identical parenting practices can have different socialization effects depending upon the broader emotional context in which they are delivered (Darling and Steinberg, 1993). The current study attempted to draw upon these related ideas to inform our understanding of the nature of criticism in families of children with ASD by testing the hypothesis that high levels of accompanying parental warmth could potentially buffer associations between criticism and children’s behavior problems.

Studies have suggested that the effects of criticism may also depend upon certain characteristics of the child, such as negative cognitive styles or genetic profiles associated with socioemotional risk (Gibb et al., 2009; Narayan et al., 2015; Sher-Carson, 2015). In a recent review, Peris and Miklowitz (2015) proposed a model for the effects of high EE on children that posits that high EE creates a “toxic stress environment” that can increase physiological stress in the child that may, in turn, exacerbate clinical symptoms. A few studies have documented higher child physiological stress in relation to high EE, including heightened activation of emotion-related brain regions (Hooley et al., 2009), skin conductance activity (Hibbs et al., 1992), and cortisol reactivity (Christiansen et al., 2010). Higher child physiological reactivity may not only be a potential outcome of high EE, but may also make certain children more vulnerable to (i.e., moderate) the negative effects of EE. Indeed, a recent study found that negative symptoms in adults with schizophrenia were particularly elevated when higher EE environments were paired with greater electrodermal reactivity (EDA) in the individual (Subotnik et al., 2012).

EDA is a marker of the sympathetic nervous system and the behavioral inhibition system (BIS), neurophysiological motivational systems involved in what is often referred to as the “fight or flight” response. Reactions in these systems involve increased arousal and attention to support risk assessment and to inhibit impulsive behaviors in situations that involve threat, potential negative consequences, or conflicting approach and avoidance motivations (Beauchaine, 2001; Fowles, Kochanska, & Murray, 2000, McNaughton & Corr, 2004). EDA is being increasingly studied in children with autism (see Lydon et al., 2015 for a review) and has been linked to autism symptom severity (Fenning et al., 2017) and externalizing behavior problems (Baker et al., 2018). Moreover, EDA appears to interact with the caregiving environment to predict important child outcomes in both children with typical development (e.g., Erath et al., 2011) and children with ASD (Baker et al., 2018). The current study examined interactions between EE-based criticism and children’s EDA reactivity, and hypothesized that criticism may be more strongly related to child problems in the context of higher child emotional reactivity.

Another novel contribution of the current study was the inclusion of a relatively diverse sample with regard to child developmental functioning and race/ethnicity. Regarding the latter, the majority of investigations involving EE in ASD have focused on Caucasian, non-Hispanic families, prompting calls for studies to include more diverse families (see Romero-Gonzalez et al., 2018, and Sher-Carson, 2015).

Method

Participants

Participants included 46 children with ASD between the ages of 4 and 11 years (M = 6.48) and their primary caregivers (see Table 1). Only one child was 11 years old. The sample was diverse with regard to race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, intellectual ability, and ASD symptom levels. Children with an existing diagnosis of ASD provided by a physician or psychologist were recruited from areas in Southern California through flyers provided to local service providers and through community events. Exclusionary criteria for the child included measured IQ below 40 (to ensure understanding of the regulation tasks) and motor impairment that would prevent independent ambulation.

Table 1.

Sample Demographic Information (n=40).

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Child | |

| Male (percent) | 78 % |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian, Non-Hispanic | 48 % |

| Caucasian, Hispanic | 23 % |

| Asian American | 13 % |

| African American | 5 % |

| “Other” | 13% |

| Primary caregiver | |

| Married (percent) | 85 % |

| Father was primary caregiver (percent) | 5 % |

| Median annual family income | US $50,000 – $70,000 |

Procedures

All procedures were approved by our institutional review board and written informed consent was obtained for all participants. The visit took place in a large room at a university laboratory that was set at 74 degrees Fahrenheit. The primary wireless EDA sensors were placed on the outer right wrist of each child, as recommended by Picard and colleagues (2016). The families then engaged in a series of established laboratory tasks. The five tasks were grouped into three conceptual categories: parent-child compliance tasks, goal-oriented problem-solving/regulatory tasks, and parent-child free play. The current study utilized EDA data from the child during the two regulatory tasks, as these data have demonstrated the most sensitivity to statistical interaction with social factors (Baker et al., 2018). The free-play was used to code parent-child attunement. The parents completed the AFMSS in a separate room during the child-alone tasks. The visit concluded with direct assessment of intellectual functioning and ASD symptoms performed by a licensed clinical psychologist with expertise in ASD.

Dyadic Problem-Solving Task (Baker et al., 2007; Fenning et al., 2017).

The dyad was positioned at the corner of a table, and provided with 32 colorful block tiles and a small photo of a completed fish puzzle. The child was instructed to make the difficult structure depicted in the photo. The parent was asked to let the child try it on his or her own, and then to provide any help that the parent deemed necessary. The experimenter returned after five minutes.

Frustration Task (Fenning et al., 2017; Jahromi et al., 2012).

Children participated in a five-minute “locked box” regulatory task alone. The child was asked to select a favorite item from a selection of prizes and it was placed in a translucent hard-plastic box, which was then locked with a padlock. The child was given a keychain with 15 visually similar, non-functional keys and instructed to try to find a key that would open the box. After five minutes, the experimenter returned and informed the child that he/she was given incorrect keys. The child was then provided with a set of appropriate keys and an opportunity to retrieve the prize.

Each of the above problem-solving tasks has been used to elicit EDA responses in children with ASD within this age and developmental range (Baker et al., 2018; Fenning et al., 2017, 2018). Further, evidence for the validity of these tasks has been presented through relations with EDA measured in other types of tasks (Fenning et al., 2017), through associations with certain child outcomes (Baker et al., 2018; Fenning et al., 2017), and with similar relations between EDA and observed emotional responses during these tasks identified across varying child age and IQ (Fenning et al., 2018).

Parent-child free play (Baker et al., 2007; Fenning et al., 2017; McDonald et al., 2016).

Parents and children were given a set of toys and asked to play as they typically would at home. The dyad was given four minutes to play.

Autism Five-Minute Speech Sample (AFMSS).

The AFMSS was completed in accordance with the instructions for this system and the original FMSS (Daley and Benson, 2008; Magaña et al., 1986). The experimenter asked the parent to speak uninterrupted for five minutes about the child and their relationship with the child. Interviews were audiotaped for later coding.

Measures

Child IQ.

An estimate of child IQ was obtained using the Stanford-Binet 5 Abbreviated Battery IQ (ABIQ; Roid, 2003). The ABIQ is comprised of two subscales with high loading on g: a Matrix Reasoning task that assesses non-verbal fluid reasoning and a Vocabulary task that evaluates expressive word knowledge. The Stanford-Binet 5 has sound psychometric properties and has been used previously for children with ASD (Fenning et al., 2017; Matthews et al., 2015; Roid, 2003).

ASD symptoms.

Level of ASD symptoms was assessed through direct testing by a clinician with formal training in the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule-2 (ADOS-2; Lord et al., 2012), a semi-structured assessment that facilitates observation and recording of child behaviors related to language, social communication, play, repetitive behaviors, and restricted interests. The ADOS-2 comparison score was used to characterize the sample according to overall ASD symptom severity, and for consideration as a covariate in final regressions, due to an established association between the comparison score and EDA in this sample (Fenning et al., 2017). Three children did not meet current criteria for ASD on the ADOS-2 but were retained due to established diagnoses by local developmental pediatricians with expertise in ASD, and having met criteria on the Social Responsiveness Scale (Constantino & Gruber, 2012), a widely-used parent report measure of ASD symptoms.1

Criticism and Warmth

Parental critical comments and warmth were coded in accordance with the AFMSS guidelines (Benson et al., 2011; Daley and Benson, 2008), wherein a full description of each code can be found. Critical comments were measured through a frequency count of statements that criticize or find fault with the child. These comments include a present-tense negative description of the child’s personality (e.g., “Jack is a nightmare”) or an account of problematic behavior delivered with a harsh tone or an indication of strong dislike or dissatisfaction (e.g., “Tom’s obsession with trains really bothers me” said with a negative tone; Daley and Benson, 2008, pp 20–21). Warmth was indexed by the intensity of the feeling expressed by the parent about the child as represented by a positive and enthusiastic tone, spontaneous expressions of affection, love, appreciation, etc., and signs of concern and empathy, and was coded 1 (low), 2 (moderate) or 3 (high) (Daley and Benson, 2008). Training followed the recommended guidelines from the creators of the system (Benson, personal communication, 2016) and involved a graduate student and a B.A.-level research associate studying the manual (Daley and Benson, 2008) with guidance from the creators. Once this pair obtained reliability, the graduate student then coded all cases with a third trained B.A.-level research associate. The AFMSS coders were blind to children’s EDA, ADOS, and behavior problem scores and were not the administrators of the AFMSS for this study. Reliability for the system based upon 35% cases was ICC = .95 for critical comments, and kappa=.70 for warmth.

Electrodermal activity (EDA).

EDA was recorded in microsiemens (us) at 8 hertz during the two regulation tasks using wireless wrist Affectiva Q-Sensors (Picard et al., 2016). The sensors measured minute changes in sweating via the electrical conductance between two 12mm Ag/AgCl dry disc electrodes and data were recorded and stored within the sensor itself. The sensors also recorded movement data, which were summed for each task and considered as a potential covariate. Skin conductance responses are instances in which there is a significant increase in sympathetic nervous system activity and can be considered either in response to a particular controlled stimulus, or summed as a measure of individual differences in general sympathetic reactivity or variability. The latter, non-specific skin conductance responses (NSCRs; Beauchaine et al., 2015; Dawson et al., 2000) were considered in the current study. Procedures for data cleaning and for deriving NSCRs have been explained in depth in several of our previous publications (see Fenning et al., 2017) and included an algorithm that determined the number of increases of at least .03us over a period of three seconds and identification and omission of any responses that would be unlikely to represent the target construct. Previous analyses of these data established psychometric support for this method, demonstrating high reliability across tasks and sensor sites, and validity with alternative indices of EDA variability, and with clinical symptoms (Fenning et al., 2017). Data from the dyadic problem-solving task and the frustration task (r = .75, p <.001) were combined to generate the composite of EDA during the regulation tasks. EDA composite scores for children missing data for the dyadic task but who had data from the locked box task (n =2) were represented by the latter. Due to high reliability across measurement sites, left hand data were used for one child for whom the right sensor malfunctioned, and data from one child who wore the sensor on the right ankle were utilized (as in Fenning et al., 2017).

Parent-child attunement.

Parent-child attunement was coded from videotapes of the free play, using the Affective Mutuality Scale of the NICHD Early Child Care Research Network Scales (e.g. 2003; McElwain et al. 2008). Dyads were rated from video on a seven-point scale (1 = very low to 7 = very high ) for behaviors indicative of affective attunement, comfort of emotional exchange, and positive responsiveness to one another. Inter-rater reliability for the current study, as performed on 33% of tapes, was very high, ICC = 0.93, and validity within this sample has been supported through links to parent-child EDA synchrony during the free-play (Baker et al., 2015).

Behavior problems.

Externalizing and internalizing behavior problems were indexed by primary caregiver report using the standardized T-score from the age-appropriate version of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 2009), a widely-used measure with demonstrated validity in children with ASD (e.g., Pandolfi, Magyar, & Dill, 2009; 2012).

Data analysis

Correlations among the variables of interest were initially considered. Four hierarchical regressions were then performed in accordance with common guidelines for testing interactions (Aiken & West, 1991: Roisman et al., 2012). Given considerations related to sample size and multicollinearity, each of the interactions (criticism × warmth and criticism × EDA) was tested separately, as was each behavior-problem outcome (internalizing and externalizing).2 ASD symptom level, criticism and warmth, and EDA were included on the first step of each regression, with the relevant interaction terms for criticism-warmth and criticism-EDA entered on the second step. Significant interactions were probed in accordance with recommendations.

Results

Of the 46 participants who began the study, one family did not complete the outcome measure of behavior problems, one was missing EDA, and four were missing the AFMSS due to running out of time (n = 2) or technical malfunctions (n = 2). Given our focus specifically on the AFMSS and behavior problems, we chose to omit these cases rather than to estimate critical data, resulting in a final sample size of 40 children. The families who were missing data did not differ significantly from those who provided full data on any demographic variable considered, or on any of the available key variables of interest.

The sample means for internalizing and externalizing problems fell within the clinical and borderline-clinical ranges, respectively (Table 2). This suggests a high level of behavior problems for this sample, consistent with previous studies in ASD (Stoppelbein et al., 2016). Research utilizing the AFMSS has suggested low rates of “low” parental warmth (20% for Benson et al. 2011; 4% in Maughan and Weiss, 2017) and, indeed, every family in the current sample scored either “moderate” or “high” in warmth. Although the mean and SD of critical comments for our sample (Table 2) was larger than that reported in the initial investigation by Benson et al. (2011; M = 1.20, SD = 1.90) our range was identical (0–9). Mean parent-child attunement fell in the “moderate” to “moderately high” range (4.59, SD = 1.44; range 1–7). Neither sensor movement, child IQ, nor any demographic variable considered was significantly related to the outcome variables, so these factors were not included in the final regressions.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among Variables of Interest.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | Mean (SD) | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child Age | -- | 6.78 (1.97) | 4 – 11 | ||||||

| 2. ASD Symptom Level | .07 | -- | 7.10 (2.25) | 1 – 10 | |||||

| 3. IQ | −.05 | −.24 | -- | 85.83 (22.83) | 47 – 139 | ||||

| 4. Criticism | .06 | −.01 | .16 | -- | 2.07 (2.09) | 0 – 9 | |||

| 5. Warmth | .12 | .04 | .01 | −.32* | -- | 2.45 (.50)a | 2 – 3 | ||

| 6. Child EDA | −.10 | .12 | .05 | −.15 | −.03 | -- | .95 (.36)b | 0.74 – 2.15 | |

| 7. Internalizing Problems | .03 | −.16 | .17 | .25 | −.07 | −.01 | -- | 64.50 (10.51) | 34 – 86 |

| 8. Externalizing Problems | −.14 | −.24 | .20 | .48** | −.36* | −.10 | .60*** | 62.55 (11.08) | 33 – 95 |

Note: ASD = Autism spectrum disorder; EDA = Electrodermal activity

The distribution of warmth was dichotomous: 55% Moderate, 45% High

This composite was constructed by averaging standardized scores, adding a constant (1), and normalizing by square root.

p<.001

p<.01

p<.05

Concurrent Validity with Observed Parent-Child Interaction

Child IQ and ASD symptom levels were each significantly related to observed parent-child attunement (.33 and −.32, p < .05, respectively). These factors were controlled due to these relations but also in order to minimize the effects of child contributions to this dyadic construct given our focus on concurrent relations with parent attitudes. Partial correlations revealed a small to moderate association between AFMSS-derived criticism and observed parent-child attunement, partial r = −.35, p = .03. This association was in the expected direction but not significant for warmth, partial r = .12, p = .47.

Relations between Criticism and Child Behavior Problems

As seen in Table 2, criticism and warmth demonstrated a moderate inverse correlation (almost identical to that reported by Benson et al., 2011), supporting the notion that these are two related but somewhat independent constructs. Both criticism and warmth were correlated with externalizing problems, and neither was significantly associated with internalizing problems, although a moderate, non-significant positive correlation was present for criticism. The two child problem behavior scales were highly positively related, but some independent variance remained. Child EDA was not significantly correlated with criticism or warmth.

Due to significant skew, criticism and EDA data were normalized for the regressions using the common square-root transformation. Warmth was recoded as 0 (moderate) and 1 (high), and all other variables were mean-centered. The first step of the hierarchical regressions essentially replicated the correlational findings with regard to internalizing problems, with neither criticism nor warmth emerging as a significant predictor (Table 3). Although both AFMSS variables were correlated with externalizing problems, only criticism emerged as a significant predictor in the regression, with warmth predicting only at the level of a trend. Together, the predictors accounted for 29% of the variance in externalizing problems.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Linear Regressions Predicting Behavior Problems.

| Internalizing Problems |

Externalizing Problems |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | SE | ß | T | p | R2∆ | B | SE | ß | t | p | R2∆ | |

| Step 1: | ||||||||||||

| ASD Symptoms | −0.99 | 0.77 | −.21 | −1.30 | .201 | .08 | −1.27 | 0.71 | −.26 | −1.80+ | .081 | .29 |

| Criticism | 2.18 | 2.16 | .17 | 1.01 | .319 | 4.34 | .99 | .32 | 2.18* | .036 | ||

| Warmth | 0.01 | 3.51 | .00 | 0.00 | .999 | −5.76 | 3.23 | −.26 | −1.78+ | .083 | ||

| EDA | 2.15 | 4.93 | .07 | 0.44 | .666 | 0.14 | 5.54 | .01 | 0.03 | .975 | ||

| Step 2a: | ||||||||||||

| ASD Symptoms | −1.46 | 0.77 | −.32 | −1.90+ | .066 | .10 | −1.67 | 0.71 | −.34 | −2.35* | .025 | .07 |

| Criticism | 5.08 | 2.50 | .40 | 2.03+ | .050 | 6.88 | 2.32 | .51 | 2.97** | .005 | ||

| Warmth | −0.98 | 3.39 | −.05 | −0.29 | .774 | −6.63 | 3.14 | −.30 | −2.11* | .042 | ||

| EDA | 2.13 | 4.72 | .07 | 0.45 | .655 | 0.12 | 4.37 | .00 | 0.03 | .978 | ||

| Criticism × Warmth | −9.49 | 4.62 | −.42 | −2.06* | .048 | −8.32 | 4.28 | −.35 | −1.94+ | .060 | ||

| Step 2b: | ||||||||||||

| ASD Symptoms | −0.97 | 0.76 | −.21 | −1.27+ | .212 | .04 | −1.22 | 0.68 | −.25 | −1.81+ | .079 | .08 |

| Criticism | 2.43 | 2.15 | .19 | 1.13 | .265 | 4.69 | 1.91 | .35 | 2.46* | .019 | ||

| Warmth | −0.00 | 3.47 | .00 | 0.00 | .999 | −5.76 | 3.09 | −.26 | −1.87+ | .071 | ||

| EDA | 4.03 | 5.09 | .14 | 0.79 | .433 | 2.79 | 4.53 | .09 | 0.62 | .542 | ||

| Criticism × EDA | 9.19 | 7.02 | .22 | 1.31 | .200 | 12.91 | 6.25 | .29 | 2.07* | .047 | ||

Note: ASD = Autism Spectrum Disorder; EDA = Elctrodermal activity; CIs for the significant interactions were −18.88 to −0.11 for internalizing problems and 0.21to 25.61 for externalizing problems.

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10.

The second step of the regressions revealed a significant interaction between criticism and warmth in the prediction of internalizing problems, with a similar interaction for externalizing problems at the level of a trend. A significant interaction between criticism and EDA was present in the prediction to externalizing problems. The significant interactions accounted for an additional 10% of the variance for internalizing problems, and 8% for externalizing problems.3

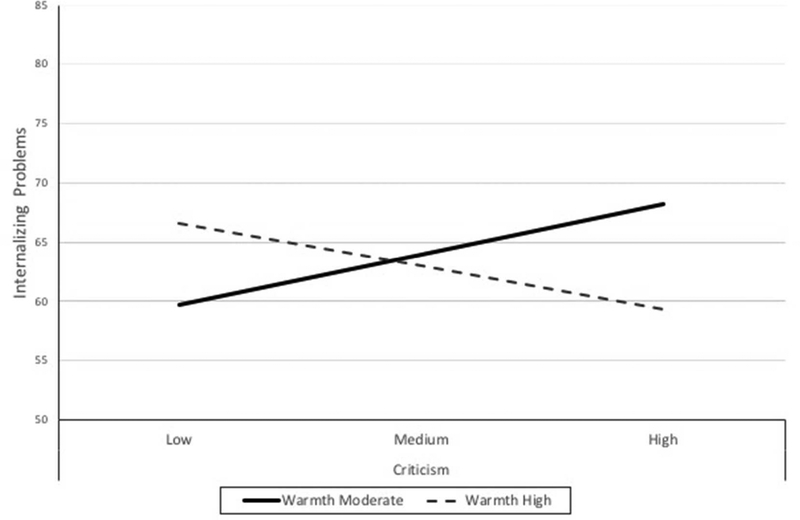

Significant interactions were probed in accordance with recommendations from Roisman et al. (2012). First, criticism-internalizing slopes were estimated for moderate and high values of warmth using Modgraph-I (Jose, 2013). Simple slope computations determined that criticism positively predicted internalizing behavior problems in the context of moderate warmth, t = 2.03, p < .05, with a “medium” effect size, d = 0.65 (Cohen, 1988), but not high warmth, t = −1.16, p = .26, d = −0.37. Figure 1 illustrates the interaction for internalizing problems. Although the interaction did not reach significance for externalizing problems, follow-up analyses revealed a similar pattern to that found for internalizing problems.

Figure 1.

Warmth as a moderator for the association between parental criticism and children’s internalizing behavior problems.

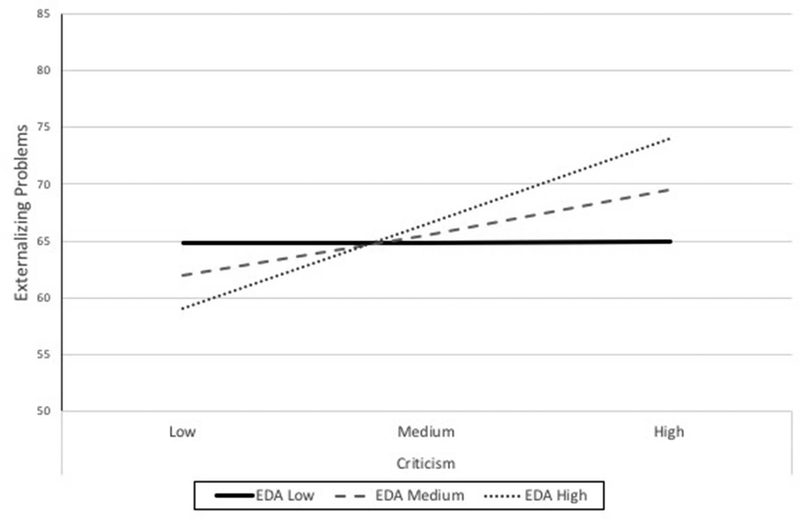

Criticism-externalizing slopes were estimated at the mean for EDA, as well as 1 SD above and 1 SD below the mean (see Figure 2). Simple slope computations determined that criticism positively predicted externalizing problems under conditions of average EDA, t = 2.45, p = .02, d = .78 (“medium” effect; Cohen, 1988), and high EDA, t = 3.03, p < .01, d = .97 (“large” effect), but not when the children exhibited low EDA, t = 0.02, p = .98, d = 0.01.

Figure 2.

Electrodermal activity (EDA) as a moderator for the association between parental criticism and children’s externalizing behavior problems.

Discussion

Findings provide further support for concurrent associations between EE-based parental criticism and externalizing behavior problems in children with ASD, and extend this literature by focusing on younger children with ASD and by utilizing a population-specific measure that has previously produced mixed findings in this area (Benson et al., 2011). Although warmth was correlated with child externalizing problems, it was less uniquely related to behavior problems above and beyond its association with criticism. Moderation findings revealed that criticism was only associated with increased internalizing behavior problems in the context of moderate (and not high) accompanying warmth, and that criticism only related to externalizing problems when children exhibited moderate or high sympathetic nervous system reactivity. The current study also provided the first empirical evidence for links between AFMSS-derived criticism and observed parent-child interaction, further supporting the validity of the system and related theories regarding mechanisms of effects.

Because criticism may drive child behavior problems—particularly in adolescents and adults with ASD—moreso than vice-versa (Baker et al., 2011b), understanding the initial onset of this association is of vital importance, requiring further investigation at younger ages (Sher-Censor, 2015). More traditional coding systems have identified associations between criticism and behavior problems in a sample of children with ASD with a mean age of 13 years (Bader and Barry, 2014). However, utilizing the Autism FMSS, Benson and colleagues (2011) did not find this association in a sample of children with a mean age of 8 years. Given evidence of associations between criticism and problem behavior in individuals with ASD across a wide age range, it is unlikely that the discrepancy between current findings and those of Benson and colleagues is due to child age. Further, although our sample was considerably more ethnically diverse than that of Benson and colleagues, available evidence from populations without ASD suggests that the ethnic composition of our sample would have likely reduced rather than increased the role of criticism (Aguilera et al., 2010). The most likely reason for the discrepant findings is the use of two different measures to assess behavior problems; however, these scales have many similarities and further research utilizing multiple assessments of child behavioral functioning is necessary.

Early EE systems omitted warmth due to doubts about whether this construct provided additional information beyond other components such as criticism (Brown et al., 1972; Sher-Carson, 2015). Although the original work with the AFMSS revealed an association with behavior problems for warmth and not critical comments (Benson et al., 2011), the current findings are consistent with the notion that criticism may be more strongly linked to both child behavior problems and parent-child interaction. Although few studies have examined criticism and warmth simultaneously, it is even more surprising that interactions between these factors have not been examined, given evidence for the buffering effects of positivity on negative attitudes in other family relationships (e.g., Gottman and Levenson, 1999). While it is true that various systems may simultaneously consider positive and negative aspects of EE when generating overall scores (e.g., ratios of negative and positive comments, Benson et al., 2011), our investigation into the specific criticism-warmth interaction suggested that high levels of warmth may buffer children with ASD against certain negative effects of criticism.

It is possible that parental criticism delivered in the context of high warmth may be experienced differently by the child. As noted, children with ASD will often evidence improved outcomes in treatment contexts involving high expectations for behavioral control and compliance, and clear contingencies for meeting or failing to meet these expectations (Lovaas, 1981). Indeed, these interventions often involve parent training aimed at embedding similar dynamics in family interaction (Lovaas, 1981; Sallows and Graupner, 2005). Some parents who adopt these potentially more directive and demanding interaction styles may attempt to balance such attitudes with high levels of warmth. The current findings suggest the potential benefit of such a balance in the parenting of children with ASD.

Given that several different types of expressions can be coded as criticism, an alternative explanation for the criticism-warmth interaction findings is that the specific forms of criticism expressed by high-warmth parents may be different than those found in parents with lower warmth. Qualitative studies or those that further deconstruct the criticism codes in families of children with ASD are needed.

The final set of findings suggest that certain children with ASD may be more vulnerable to parental criticism than others based upon their psychophysiological reactivity. Our findings are somewhat consistent with the notion of a “toxic stress environment” (Peris and Miklowitz, 2015) and fully in line with evidence from families of individuals with schizophrenia (Subotnik et al., 2012), suggesting that children who are more constitutionally reactive in their physiological arousal may be more sensitive to the effects of criticism. This notion is also consistent with developmental theory and findings regarding interactions between child temperament and parenting. For example, seminal work by Kochanska and colleagues (1997) found different paths to moral internalization for temperamentally inhibited/reactive children as contrasted with fearless children in that only the former appeared to benefit from mothers’ ability to be gentle in their guidance and discipline.

Because findings for children with moderate EDA were similar to those with higher EDA, it is perhaps more accurate to posit that children with low reactivity may be more resilient than others against critical family attitudes. Indeed, fearlessness theory (Raine, 1993) proposes that children with lower sympathetic arousal may be less susceptible to socialization efforts due to a reduced reactivity to parent directives and potential consequences for non-compliance. A host of evidence supports this theory in that children with lower sympathetic responding appear to be at risk for externalizing problems (e.g., Beauchaine, 2001; El-Sheikh and Erath, 2011) and this phenomenon has recently been replicated in the current sample utilizing EDA obtained during tasks more specifically designed to elicit compliance/non-compliance than those utilized in the current study (Baker et al., 2018). Theory, research, and the current findings collectively suggest that lower sympathetic reactivity may predispose children with ASD to risk for externalizing problems, but may buffer these children against certain negative aspects of the parenting environment to which they may be less attuned. This is not to suggest that children with lower EDA are not susceptible to the environment. Studies involving populations without neurodevelopmental disorders have consistently found that harsh discipline may exacerbate risk for externalizing problems in children with low EDA (Erath et al., 2011), and our previous work with the current sample found that parental co-regulatory support may buffer this psychophysiological risk (Baker et al., 2018). One possible explanation for this apparent contradiction is that children with low EDA may be less susceptible to more subtle or distal family factors (e.g., emotional climate or attitudes) but may depend more highly upon aspects of parent-child interaction that actively engage the child (such as harsh discipline or scaffolding).

Contrary to the toxic stress environment theory, no significant direct association was identified between criticism and children’s EDA. Although our previous work found moderate to high consistency in NSCRs across various laboratory tasks (Fenning et al., 2017), the degree to which certain indices of EDA represent more trait- vs. state-like tendencies is currently unknown (Beauchaine et al., 2015); thus it is possible that our children may have exhibited higher EDA responding during instances of criticism, but that these critical environments have not yet translated into higher general sympathetic arousal tendencies. Alternatively, it is possible that high EDA may be a more salient moderator than outcome of criticism in ASD.

Implications for Intervention

It is tempting in studies of EE to conclude that family intervention efforts are warranted, aimed at increasing warmth and reducing criticism. While this conclusion may still be appropriate, our findings also suggest more complexity. First, as with previous studies in ASD (Benson et al., 2011; Maughan and Weiss, 2017), low parental warmth was essentially nonexistent in our sample, suggesting an ability in this population to maintain positive parenting in the context of a stressful caregiving situation. It is the case, however, that high levels of warmth may be beneficial in balancing any increases in criticism, suggesting the merit of increasing this facet of parenting, but with an understanding that warmth is not lacking in these parents as a group.

The current findings and those of our previous work with this sample (Baker et al., 2018) suggest the potential utility of tailoring intervention efforts, particularly with parents, to address heterogeneity in ASD. For example, efforts for children lower in arousal reactivity could perhaps focus on training parents in direct co-regulatory behaviors that may reduce the children’s physiological risk (Baker et al., 2018). For children with higher reactivity, interventions may focus more on addressing the emotional tone of the parenting environment, reducing harsh criticism in families with high levels, and perhaps working to balance demands for change with accompanying warmth.

A major limitation of the current study is the sample size, which was generally appropriate for our regression analyses but modest for investigating interactive effects. Indeed, a key consideration would be to explore potential three-way interactions among criticism, warmth, and children’s EDA. The current study was designed to understand heterogeneity among children with ASD; however, the inclusion of a comparison group of children without ASD would considerably inform the present findings, given that our exploration extended beyond that which is currently known about EE or criticism in general. Given the relatively consistent association observed between criticism and externalizing problems in children with ASD, longitudinal studies involving the current age group, or even younger children, would provide important information about the early or initial development of this association. Furthermore, the cross-sectional nature of the current study can only identify associations, whereas a longitudinal design could provide more evidence for causal effects. As with most EE studies, child outcomes were measured through parent report, so the use of observational child data would remove any potential report bias.

As mentioned, certain aspects of the original EE systems (e.g., over-involvement) do not appear valid for families of children with ASD; however, criticism codes derived from these systems have been reliably used in ASD and have identified several of the effects discussed. Although the notion of a population-specific system is appealing, the degree to which the AFMSS is necessarily more or as useful for this population requires further empirical investigation. Studies including both the original FMSS and the AFMSS could more clearly speak this issue.

Although our study was far more inclusive of diversity in developmental profiles (indeed, no interested family was excluded based upon the relevant criterion), investigations with children with measured IQ under 40 would be beneficial. Finally, our study focused on primary caregivers, a few of whom were fathers; however, inclusion of both parents in two-parent families would provide a more robust index of the family and parenting environment. Many parents of children with ASD struggle with determining which interactive styles will maximally benefit their children, and more research aimed at understanding this unique parenting context will likely provide valuable guidance for these families.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by intramural funds awarded by the California State University, Fullerton and by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R15HD087877). We wish to thank the families who made this work possible. We also thank Jacquelyn Moffitt, Chloe Frith, Alyssa Bailey, Arielle Garcia, and Marison Lee for their contributions to data processing and coding.

Footnotes

Final analyses were performed with and without these children and are reported.

Analyses were also conducted with both interactions in the same regression (for a total of two regressions); results are reported.

Analyses including both interaction terms in the same regression resulted in similar findings with identical patterns of significance for key variables with the exception that the trend for criticism × warmth in the prediction of externalizing problems became statistically significant. Analyses omitting the three children who did not meet criteria on the ADOS-2 were also very similar, with the exception of the emergence of the criticism × warmth interaction as significant for externalizing problems.

Contributor Information

Jason K. Baker, California State University, Fullerton

Rachel M. Fenning, California State University, Fullerton

Mariann A. Howland, University of California, Irvine

David Huynh, California State University, Fullerton.

References

- Achenbach TM (2009). The Achenbach System of Empirically Based Assessment (ASEBA): Development, Findings, Theory, and Applications. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera A, López SR, Breitborde NK et al. (2010). Expressed emotion and sociocultural moderation in the course of schizophrenia. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology 119(4): 875–885. doi: 10.1037/a0020908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aiken L, & West S (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Bader SH, & Barry TD (2014). A longitudinal examination of the relation between parental expressed emotion and externalizing behaviors in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 44(11): 2820–2831. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker BL, Neece CL, Fenning RM et al. (2010a). Mental disorders in five year old children with or without developmental delay: Focus on ADHD. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 39: 492–505. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2010.486321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JK, Fenning RM, Crnic KA et al. (2007). Prediction of social skills in 6-year-old children with and without developmental delays: Contributions of early regulation and maternal scaffolding. American Journal On Mental Retardation 112: 375–391. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[0375:POSSIY]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JK, Fenning RM, Erath SA et al. (2018). Sympathetic under-arousal and externalizing behavior problems in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46, 895–906. doi: 10.1007/s10802-017-0332-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JK, Messinger DS, Lyons KK et al. (2010b). A pilot study of maternal sensitivity in the context of emergent autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 40: 988–999. doi: 10.1007/s10803-010-0948-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JK, Seltzer MM, & Greenberg JS (2011a). Longitudinal effects of adaptability on behavior problems and maternal depression in families of adolescents with autism. Journal of Family Psychology 25: 601–609. doi 10.1037/a0024409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker JK, Smith LE, Greenberg et al. (2011b). Change in maternal criticism and behavior problems in adolescents and adults with autism across a seven-year period. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 120: 465–475. doi: 10.1037/a0021900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP (2001). Vagal tone, development, and Gray’s motivational theory: Toward an integrated model of autonomic nervous system functioning in psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology 13(2): 183–214. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beauchaine TP, Neuhaus E, Gatzke-Kopp LM et al. (2015). Electrodermal responding predicts responses to, and may be altered by, preschool intervention for ADHD. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 83: 293–303. doi: 10.1037/a0038405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson PR (2013). Family influences on social and play outcomes among children with ASD during middle childhood. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders 7: 1129–1141. [Google Scholar]

- Benson PR, Daley D, Karlof KL et al. (2011). Assessing expressed emotion in mothers of children with autism: The Autism-Specific Five Minute Speech Sample. Autism 15: 65–82. doi: 10.1177/1362361309352777 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop-Fitzpatrick L, Hong J, Smith LE et al. (2016). Characterizing objective quality of life and normative outcomes in adults with autism spectrum disorder: An exploratory latent class analysis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 46(8): 2707–2719. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2816-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Birley JLT, & Wing JK (1972). Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic disorders: A replication. British Journal of Psychiatry 121: 241–258. doi: 10.1192/bjp.121.3.241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Leezenbaum NB, Mahoney AS et al. (2015). Social engagement with parents in 11-month-old siblings at high and low genetic risk for autism spectrum disorder. Autism 19(8): 915–924. doi: 10.1177/1362361314555146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen H, Oades RD, Psychogiou L et al. (2010) Does the cortisol response to stress mediate the link between expressed emotion and oppositional defiant disorder in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behavioral and Brain Functions 6:45. doi: 10.1186/1744-9081-645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino JN & Gruber CP (2012). Social Responsiveness Scale, Second Edition (SRS-2). Manual. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Cridland EK, Jones SC, Magee CA et al. (2014). Family-focused autism spectrum disorder research: A review of the utility of family system approaches. Autism 18(3): 213–222. doi: 10.1177/1362361312472261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley D, & Benson PR (2008). Manual for coding expressed emotion in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: The autism-specific five minute speech sample. Boston: Center for Social Development and Education, University of Massachusetts Boston. [Google Scholar]

- Daley D, Sonuga-Barke EJS, & Thompson M (2003). Assessing expressed emotion in mothers of preschool AD/HD children: Psychometric properties of a modified speech sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology 42: 53–67. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.1.1.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, & Steinberg L (1993). Parenting style as context: An integrative model. Psychological Bulletin 113(3): 487–496. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.3.487 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G (2008). Early behavioral intervention, brain plasticity, and the prevention of autism spectrum disorder. Development and Psychopathology 20: 775–803. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson M, Schell A, & Filion D (2000). The electrodermal system In, Cacioppo J, Tassinary L, & Berntson G (Eds.), Handbook of psychophysiology, 2nd ed. Cambridge University Press; pp. 200–223. [Google Scholar]

- Deater-Deckard K, Ivy L, & Petrill SA (2006). Maternal warmth moderates the link between physical punishment and child externalizing problems: A parent-offspring behavior genetic analysis. Parenting: Science And Practice 6(1): 59–78. doi: 10.1207/s15327922par0601_3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh M & Erath SA (2011). Family conflict, autonomic nervous system functioning, and child adaptation: State of the science and future directions. Development and Psychopathology 23: 703–721. doi: 10.1017/S0954579411000034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erath SA, El-Sheikh M, Hinnant JB et al. (2011). Skin conductance level reactivity moderates the association between harsh parenting and growth in child externalizing behavior. Developmental Psychology, 47, 693–706. doi: 10.1037/a0021909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenning RM, Baker JK, Baker BL et al. (2014). Parent-child interaction over time in families of young children with borderline intellectual functioning. Journal of Family Psychology 28: 326–353. doi: 10.1037/a0036537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenning RM, Baker JK, Baker BL, et al. (2007). Parenting children with borderline intellectual functioning: A unique risk population. American Journal on Mental Retardation 112: 107–121. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2007)112[107:PCWBIF]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenning RM, Baker JK, Baucom BR et al. (2017). Electrodermal activity and symptom severity in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 47: 1062–1072. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-3021-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenning RM, Baker JK, & Moffitt J (2018). Instrinsic and extrinsic predictors of emotion regulation in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Online ahead of print. doi: 10.1007/s10803-018-3647-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogler JM, Thompson MC, Steketee G, et al. (2007). Influence of expressed emotion and perceived criticism on cognitive-behavioral therapy for social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy 45: 235–249. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowles DC, Kochanska G, & Murray K (2000). Electrodermal activity and temperament in preschool children. Psychophysiology, 37(6), 777–787. doi: 10.1017/S0048577200981836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibb BE, Uhrlass DJ, Grassia M et al. (2009). Children’s inferential styles, 5-HTTLPR genotype, and maternal expressed emotion-criticism: An integrated model for the intergenerational transmission of depression. Journal Of Abnormal Psychology 118(4): 734–745. doi: 10.1037/a0016765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, & Levenson RW (1999). What predicts change in marital interaction over time? A study of alternative medicine. Family Process 38(2): 143–158. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1999.00143.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Hong J et al. (2006). Bidirectional effects of expressed emotion and behavior problems and symptoms in adolescents and adults with autism. American Journal on Mental Retardation 111: 229–249. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[229:BEOEEA]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, Daley D, Burns C et al. (2006). Maternal distress and expressed emotion: Cross-sectional and longitudinal relationships with behavior problems of children with intellectual disabilities. American Journal on Mental Retardation 111: 48–61. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2006)111[48:MDAEEC]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings RP, & Lloyd T (2007). Expressed emotion in families of children and adults with intellectual disabilities. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews 13: 339–345. doi: 10.1002/mrdd.20173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibbs ED, Zahn TP, Hamburger SD et al. (1992) Parental expressed emotion and psychophysiological reactivity in disturbed and normal children. British Journal of Psychiatry 160: 504–510. doi: 10.1192/bjp.160.4.504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM (1998). Expressed emotion and psychiatric illness: From empirical data to clinical practice. Behavior Therapy 29: 631–646. doi: 10.1016/S0005-7894(98)80022-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Gruber SA, Parker HA et al. (2009) Cortico-limbic response to personally challenging emotional stimuli after complete recovery from depression. Psychiatry Research 28(171): 106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jahromi L, Meek S, & Ober-Reynolds S (2012). Emotion regulation in the context of frustration in children with high functioning autism and their typical peers. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 53(12): 1250–1258. doi: 10.1002/aur.1366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jose PE (2013). ModGraph-I: A programme to compute cell means for the graphical display of moderational analyses (Version 3.0). Wellington, New Zealand: Victoria University of Wellington; Retrieved from http://pavlov.psyc.vuw.ac.nz/paul-jose/modgraph/ [Google Scholar]

- Kim JA, Szatmari P, Bryson SE et al. (2000). The prevalence of anxiety and mood problems among children with autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism 4(2): 117–132. doi: 10.1177/1362361300004002002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kochanska G (1997). Multiple pathways to conscience for children with different temperaments: from toddlerhood to age five. Developmental Psychology 33: 228–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore P et al. (2012). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2). Manual. Torrance, CA: WPS. [Google Scholar]

- Lovaas OI (1981). Teaching developmentally disabled children: The me book. University Park Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lydon S, Healy O, Reed P, Mulhern T, Hughes BM, & Goodwin MS (2015). A systematic review of physiological reactivity to stimuli in autism. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 19, 1–21. doi: 10.3109/17518423.2014.971975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarty C, Lau A, Valeri S, & Weisz J (2004). Parent–child interactions in relation to critical and emotionally overinvolved expressed emotion (EE): Is EE a proxy for behavior? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 83–93. doi: 10.1023/B:JACP.0000007582.61879.6f [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McClintock K, Hall S, & Oliver C (2003). Risk markers associated with challenging behaviours in people with intellectual disabilities: A meta‐analytic study. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research 47(6): 405–416. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2788.2003.00517.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccoby EE, & Martin JA (1983). Socialization in the context of the family: parent-child interaction In Mussen PH (Series Ed.) & Hetherington EM (Vol. Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, personality, and social development (4th ed., pp. 1–101) New York: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- McDonald NM, Baker JK, & Messinger DS (2016). Oxytocin and parent-child interaction in the development of empathy among children at risk for autism. Developmental Psychology 25(5): 735–745. doi: 10.1037/dev0000104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElwain NL, Booth-LaForce C, Lansford JE, Wu XY, & Dyer WJ (2008). A process model of attachment-friend linkages: Hostile attribution biases, language ability, and mother–child affective mutuality as intervening mechanisms. Child Development 79: 1891–1906. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01232.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod BD, Wood JJ, & Weisz JR (2007). Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 27(2): 155–172. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNaughton N, & Corr PJ (2004). A two-dimensional neuropsychology of defense: fear/anxiety and defensive distance. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 28, 285–305. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2004.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaña AB, Goldstein MJ, Karno M et al. (1986). A brief method for assessing expressed emotion in relatives of psychiatric patients. Psychiatry Research 17: 203–212. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(86)90049-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matson JL, & Nebel-Schwalm MS (2007). Comorbid psychopathology with autism spectrum disorder in children: An overview. Research in Developmental Disabilities 28(4): 41–352. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2005.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews NL, Pollard E, Ober-Reynolds S et al. (2015). Revisiting cognitive and adaptive functioning in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disabilities 45(1): 138–156. doi: 10.1007/s10803-014-2200-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan AL, & Weiss JA (2017). Parental outcomes following participation in cognitive behavior therapy for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders 47(10): 3166–3179. doi: 10.1007/s10803-017-3224-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan A, Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA et al. (2015). Interrelations of maternal Expressed Emotion, maltreatment, and separation/divorce and links to family conflict and children’s externalizing behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 43: 217–228. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9911-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICHD Early Child Care Research Network. (2003). Early child care and mother-child interaction from 36 months through first grade. Infant Behavior and Development 26: 345–370. doi: 10.1016/S0163-6383(03)00035-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi V, Magyar CI, & Dill CA (2009). Confirmatory factor analysis of the Child Behavior Checklist 1.5 – 5 in a sample of children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 39, 986–995. doi: 10.1007/s/10803-009-0716-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandolfi V, Magyar CI, & Dill CA (2012). An initial psychometric evaluation of the CBCL 6 – 18 in a sample of youth with autism spectrum disorders. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 6, 96–108. doi: 10.1016/j.rasd.2011.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peris TS, & Miklowitz DJ (2015). Parental expressed emotion and youth psychopathology: New directions for an old construct. Child Psychiatry and Human Development 46(6): 863–873. doi: 10.1007/s10578-014-0526-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picard RW, Fedor S, & Ayzenberg Y (2016). Multiple arousal theory and daily-life electrodermal activity asymmetry. Emotion Review 8: 62–75. doi: 10.1177/1754073914565517 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raine A (1993). The psychopathology of crime: Criminal behavior as a clinical disorder. San Diego: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Roid GH (2003). Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, Fifth Edition. Itasca, IL: Riverside. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roisman GI, Newman DA, Fraley RC, Haltigan JD, Groh AM, & Haydon KC (2012). Distinguishing differential susceptibility from diathesis-stress: Recommendations for evaluating interaction effects. Development and Psychopathology, 24, 389–409. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Gonzalez M, Chandler S, & Simonoff E (2018). The relationship of parental expressed emotion to co-occurring psychopathology in individuals with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Research in Developmental Disabilities 72: 152–165. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2017.10.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, & Weisz JR (1994). Parental caregiving and child externalizing behavior in nonclinical samples: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 116(1): 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sallows GO, & Graupner TD (2005). Intensive behavioral treatment for children with autism: Four-year outcome and predictors. American Journal on Mental Retardation 110(6): 417–438. doi: 10.1352/0895-8017(2005)110[417:IBTFCW]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher-Censor E (2015). Five Minute Speech Sample in developmental research: A review. Developmental Review 36: 127–155. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2015.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simonoff E, Pickles A, Charman T et al. (2008). Psychiatric disorders in children with autism spectrum disorders: prevalence, comorbidity, and associated factors in a population-derived sample. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 47: 921–929. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318179964f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LE, Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM et al. (2008). Symptoms and behavior problems of adolescents and adults with autism: Effects of mother–child relationship quality, warmth, and praise. American Journal on Mental Retardation 113: 387–402. doi: 10.1352/2008.113:387-402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoppelbein L, Biasini F, Pennick M et al. (2016). Predicting internalizing and externalizing symptoms among children diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child & Family Studies 25: 251–261. doi: 10.1007/s10826-015-0218-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Subotnik KL, Schell AM, Chilingar MS et al. (2012). The interaction of electrodermal activity and expressed emotion in predicting symptoms in recent‐onset schizophrenia. Psychophysiology 49(8): 1035–1038. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01383.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonge BJ, Brereton AV, Gray KM et al. (1999). Behavioural and emotional disturbance in high-functioning autism and Asperger syndrome. Autism 3(2): 117–130. doi: 10.1177/1362361399003002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughn C, & Leff J (1976) The measurement of expressed emotion in the families of psychiatric patients. British Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology 15(2): 157–165. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1976.tb00021.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wainer AL, Hepburn S, & McMahon Griffith E (2017). Remembering parents in parent- mediated intervention: An approach to examining impact on parents and families. Autism 21: 5–17. doi: 10.1177/1362361315622411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White SW, Oswald D, Ollendick T et al. (2009). Anxiety in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Clinical Psychology Review 29(3): 216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.01.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodman AC, Mailick MR, & Greenberg JS (2016). Trajectories of internalizing and externalizing symptoms among adults with autism spectrum disorders. Development and Psychopathology 28(2): 565–581. doi: 10.1017/S095457941500108X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]