Abstract

Bacillus megaterium TRQ8 was isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) rhizosphere in commercial fields in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico. Here, we report the draft genome of strain TRQ8, with a size of ~ 5.6 Mbp and a G + C content of 38%. Based on the cutoff values on species delimitation established for average nucleotide identity (> 95–96%), genome-to-genome distance calculator (> 70%), and the reference sequence alignment-based phylogeny (REALPHY) builder method, TRQ8 was strongly affiliated to Bacillus megaterium. The rapid annotation using subsystem technology server revealed that TRQ8 contains 153 RNA genes, and 6113 coding DNA sequences, including those related to plant growth promotion traits, i.e. auxin biosynthesis, phosphate metabolism, siderophores production, and osmotic and oxidative stress response. The function of those putative annotated genes was validated at metabolic level, observing that strain TRQ8 was able to produce 12.0 ± 1.9 µg/mL indoles, phosphate solubilization of 38.7 ± 4.2%, siderophore production of 8.1 ± 0.2%, and tolerance to saline (80.0 ± 5.3%), and water (110.0 ± 4.2%) stress conditions. This genomic and metabolic background was in vivo corroborated by the inoculation of TRQ8 to wheat plants (30 days, under axenic conditions), observing a significant (p = 0.05) increment (compared to un-inoculated plants) of shoot height (16.4%), root length (68.4%), total plant length (30.9%), stem diameter (26.7%), stem circumference (34.8%), shoot dry weight (60.0%), root dry weight (55.6%). Those results provide insights for future agricultural studies and potential applications of this strain, as a plant growth-promoting bacterium.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13205-019-1726-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Rhizosphere, Draft genome, Bacillus megaterium TRQ8

The genus Bacillus was isolated by Cohn (1872), who described it as a rod-shaped, heat-resistant, endospore-forming Gram-positive bacterium. At present, this genus is one of the largest bacterial genera in the world, comprising around 377 species (Parte 2018). Bacillus megaterium is a Gram-positive, aerobic, and endospore-forming bacterium described in 1884 by Anton De Bary (Cabañas and García 2015; Villarreal-Delgado et al. 2018; Villa-Rodriguez et al. 2018). The term “megat(h)erium” was designed due to its large size, which literal meaning is “big animal” in Greek; being considered as the largest bacterium among the genus Bacillus (Eppinger et al. 2011). This species has been widely studied and characterized for its potential as a plant growth-promoting bacterium, as well as its industrial applications, including phytohormones production, phosphate solubilization, sporulation capacity, antimicrobial activity, and recombinant protein production (Ortíz et al. 2008; Malanicheva et al. 2012; Cabañas and García 2015; Aslam et al. 2016; Ruiz-Aguirre et al. 2017; Sharaf et al. 2018).

Strain TRQ8 was isolated from wheat (Triticum turgidum subsp. durum) rhizosphere in commercial fields in the Yaqui Valley, Mexico. At present, this strain is preserved in Colección de Microorganismos Edáficos y Endófitos Nativos del Instituto Tecnológico de Sonora (Mexico) (http://www.itson.mx/COLMENA) (de los Santos-Villalobos et al. 2018). Based on the strong interaction of TRQ8 with wheat plants in the field, its unknown taxonomic classification, and genomic background associated to wheat growth promotion, the genome of this strain was sequenced.

High-quality extraction of genomic DNA was prepared from a stationary culture of strain TRQ8 grown in nutrient broth (24 h at 32 °C, using an orbital shaker at 121 rpm), and following the protocol described by Valenzuela-Aragon et al. (2018). Then, the genome sequence of strain TRQ8 was performed by Genomic Services Laboratory (LANGEBIO, Irapuato, Guanajuato, Mexico) using the Illumina MiSeq platform. A total of 1,103,862 paired-end reads (2 × 300 bp) were generated. The quality control of the reads was conducted with a FastQC analysis version 0.11.5 (Andrews 2010). Trimmomatic version 0.32 (Bolger et al. 2014) was used to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases. De novo assembly was performed using SPAdes version 3.10.1 (Bankevich et al. 2012), using the “–careful” parameter for reads error correction. The draft genome consists of 247 contigs (> 200 bp), 5,572,365 bp, with a G + C content of 38%, a N50 value of 571,610 bp, and a L50 value of 4. The assembled contigs were ordered by Mauve contig Mover (MCM) (Rissman et al. 2009), using the reference genome of Bacillus megaterium 15308 (NCBI project accession PRJNA224116). Additionally, PLACNETw was used to determinate the presence of plasmids in the genome (Vielva et al. 2017). It was found that the TRQ8 genome contains seven plasmids, and this finding has been previously observed for this bacterial species due to many strains of B. megaterium carry four to ten plasmids (Kunnimalaiyaan and Vary 2005).

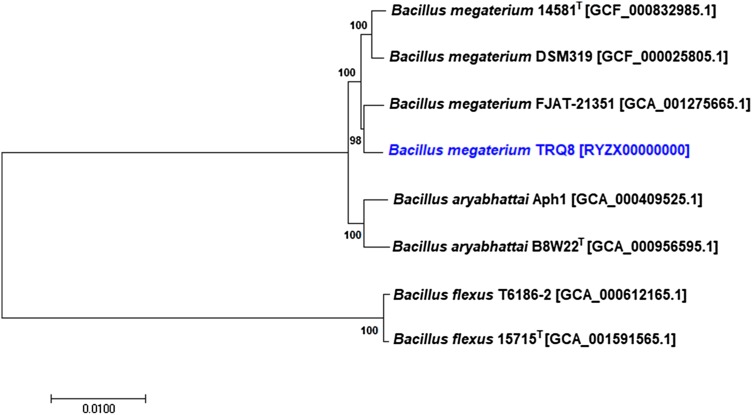

To clarify the taxonomic classification of strain TRQ8, its 16S rRNA gene sequence was first submitted to the EzBiocloud database (Yoon et al. 2017a, b), using the identify tool for similarity comparison, to determinate its more closely related strains (> 98.7%; Chun et al. 2018). It was found that Bacillus megaterium 14581(T), Bacillus aryabhattai B8W22 (T), and Bacillus flexus 15715(T) shared the highest similarity values obtaining 100, 99.86, and 98.98%, respectively. Thus, these species were compared to strain TRQ8 at a genome-based approach, using average nucleotide identity (ANI), by the OrthoANI algorithm (Yoon et al. 2017a, b); and genome-to-genome distance calculator (GGDC) 2.1 (also known as in silico DNA–DNA hybridization), by BLAST (Meier et al. 2013) (Table 1). Based on the cutoff values on species delimitation established for ANI (> 95–96%; Varghese et al. 2015) and GGDC (> 70%; Espariz et al. 2016), TRQ8 was strongly affiliated to Bacillus megaterium.

Table 1.

ANI and GGDC values obtained from the comparison of strain TRQ8 and its more closely related species (16S rRNA > 98.7%)

| Bacillus megaterium TRQ8 vs | Ortho ANI (%) | GGDC (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Bacillus megaterium DSM319 | 96.92 | 73.40 |

| Bacillus megaterium FJAT-21351 | 96.90 | 73.30 |

| Bacillus megaterium 14581T | 96.65 | 71.90 |

| Bacillus aryabhattai B8W22T | 95.61 | 64.40 |

| Bacillus aryabhattai Aph1 | 95.76 | 65.30 |

| Bacillus flexus 15715T | 74.52 | 19.80 |

| Bacillus flexus T6186-2 | 74.27 | 20.10 |

In addition, with the aim to determinate the phylogenetic relationship between strain TRQ8 and its closely related species, their genomes sequences were aligned using the reference sequence alignment-based phylogeny (REALPHY) builder method (Bertels et al. 2014). The genome-based phylogenetic tree was constructed by MEGA 7 (Kumar et al. 2016), using the neighbor-joining method, with a bootstrap support of 1000 replications (Fig. 1). The forming clade of strain TRQ8 with the most related strains supports its affiliation as Bacillus megaterium.

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic relationship among strain TRQ8 and its close related species: B. megaterium 14581T [GCF_000832985.1], B. megaterium DSM319 [GCF_000025805.1], B. megaterium FJAT-21351 [GCA_001275665.1], B. aryabhattai Aph1 [GCA_000409525.1], B. aryabhattai B8W22T [GCA_000956595.1], B. flexus T6186-2 [GCA_000612165.1], and B. flexus 15715T [GCA_001591565.1]. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the REALPHY builder method and MEGA 7, using the neighbor-joining algorithm (based on 1000 bootstrap replications). Scale bar (0.0100) represents the number of nucleotide substitutions per site

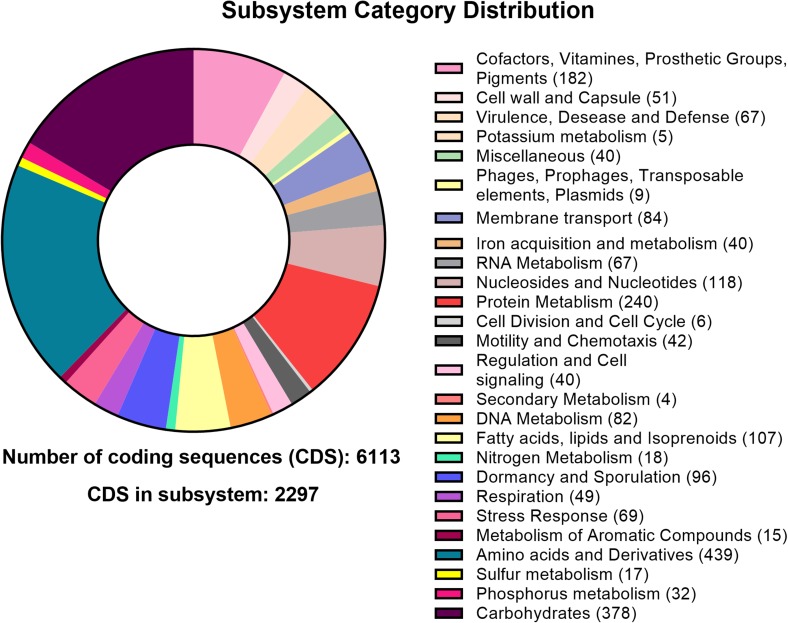

The gene annotation of B. megaterium TRQ8 was carried out by the rapid annotation using subsystem technology (RAST) server (http://rast.nmpdr.org) (Aziz et al. 2008), using the RASTtk pipeline. For strain TRQ8, a total of 153 RNAs were predicted, and 6113 coding DNA sequences (CDSs) were assigned into 367 subsystems. The most abundant subsystem was amino acids and derivates (439 genes), followed by carbohydrates (378 genes), protein metabolism (240 genes), cofactors, vitamins, prosthetic groups, and pigments (182 genes), nucleosides and nucleotides (118 genes), fatty acids, lipids, and isoprenoids (107 genes), and dormancy and sporulation (96 genes) (Fig. 2). The genome of TRQ8 showed the presence of genes involved in interaction and tolerance to biotic and abiotic factors in agro-systems, as well as to stablish bacteria–plant interactions, i.e., auxin biosynthesis (indoles), phosphate metabolism, siderophores production, and osmotic and oxidative stress response (Table S1).

Fig. 2.

Subsystem category distribution of CDS from strain TRQ8, following RAST pipeline

To validate the function of those putative annotated genes associated with plant growth promotion traits, strain TRQ8 was metabolically characterized according to Valenzuela-Aragon et al. (2018), based on its ability to biosynthesize indoles (Salkowsky method), solubilize phosphates (Pikovskaya method), produce siderophores (Chromo Azurol S method), and tolerate saline (sodium chloride assay), and water (polyethylene glycol 6000 assay) stress conditions. It was found that strain TRQ8 was able to produce 12.0 ± 1.9 µg/mL indoles, phosphate solubilization of 38.7 ± 4.2%, siderophore production of 8.1 ± 0.2%, and tolerance of saline (80.0 ± 5.3%), and water (110.0 ± 4.2%) stress conditions, confirming the functionality of putative annotated genes in the TRQ8 genome. Thus, to evaluate the potential of strain TRQ8 as a plant growth-promoting bacterium (PGPB), an axenic in vivo plant–bacterium interaction assay was performed. The bacterium was cultured in nutrient broth (24 h at 28 °C, using an orbital shaker at 120 rpm). The obtained inoculum was centrifuged at 3500 rpm, and the pellet was re-suspended in sterile (121 °C and 15 psi for 15 min) distilled water, adjusting to 1 × 108 colony-forming Units (CFU)/mL. Wheat plants Var. CIRNO C2008 [washed three times with sterile distilled water, soaked in 70% (v/v) ethanol for 1 min, followed by a wash with 3% (v/v) sodium hypochlorite for 10 min, and five washes with sterile distilled water] were inoculated with 1 mL of this cell suspension (at 0 and 15 days), and un-inoculated plants were sprayed with sterile distilled water, as negative control. Each treatment consisted of two replicates with 15 plants. A sterilized soil-perlite (70:30) mix was used as substrate. This assay was carried out under controlled and axenic conditions in a growth chamber BJPX-A450-BIOBASE [relative humidity of 70%, photoperiod of 12 h light/12 h darkness, temperature of 25 °C (day)/15 °C (night) for 30 days]. Then, plant biometrics parameters were studied according to Thilagar et al. (2016). The inoculation of B. megaterium TRQ8 to wheat plants showed a significant (Tukey–Kramer test, p = 0.05) increment (compared to un-inoculated plants) of shoot height (16.4%), root length (68.4%), total plant length (30.9%), stem diameter (26.7%), stem circumference (34.8%), shoot dry weight (60.0%), and root dry weight (55.6%) (Table 2), confirming the function of putative annotated genes and its related metabolic traits in the TRQ8 genome.

Table 2.

Wheat growth promotion by the inoculation of B. megaterium TRQ8 (in a growth chamber assay)

| Variable | Control | Bacillus megaterium TRQ8 |

|---|---|---|

| Shoot height | 18.59 ± 5.41a | 21.63 ± 2.64b |

| Root length | 7.41 ± 2.24a | 12.48 ± 0.97b |

| Total plant length | 26.01 ± 6.79a | 34.07 ± 3.13b |

| Stem diameter | 0.15 ± 0.04a | 0.19 ± 0.02b |

| Stem circumference | 0.46 ± 0.13a | 0.62 ± 0.10b |

| Shoot dry weight | 0.05 ± 0.02a | 0.08 ± 0.02b |

| Root dry weight | 0.09 ± 0.02a | 0.14 ± 0.04b |

Means (2 × n = 15) with the same letter are not significantly different, according to Tukey–Kramer test (p = 0.05)

The obtained results confirm that strain TRQ8 belongs to Bacillus megaterium. Its genome contains putative annotated genes involved in plant growth promotion traits, which were validated by metabolic assays. In addition, the genomic/metabolic background, and the positive interaction of this strain to wheat plants, suggests to TRQ8 as a promising PGPB, which needs to be studied for providing complementary information for its application in agro-systems.

The assembled contigs were deposited in the DDBJ/ENA/GenBank and published with the accession number RYZX00000000. The version described in this paper is the first version of the genome sequence deposited.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Cátedras CONACyT Program through Project 1774 “Alternativas agrobiotecnológicas para incrementar la competitividad del cultivo de trigo en el Valle del Yaqui: desde su ecología microbiana hasta su adaptabilidad al cambio climático”, the CONACyT Project 257246 “Interacción trigo x microorganismos promotores del crecimiento vegetal: identificando genes con potencial agro-biotecnológico”, and The Instituto Tecnológico de Sonora (ITSON) Project PROFAPI 2018_0012 “Secuenciación del genoma de Bacillus megaterium TRQ8 para la identificación de mecanismos de promoción del crecimiento vegetal”. In addition, we thank Abraham Chaparro Encinas for his support in the bacterial DNA extraction. Rosa Icela Robles Montoya was supported by CONACYT fellowship 627262.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Andrews S (2010) FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc. Accessed 11 Jan 2019

- Aslam S, Hussain A, Iqbal J. Dual action of chromium-reducing and nitrogen-fixing Bacillus megaterium-ASNF3 for improved agro-rehabilitation of chromium-stressed soils. 3Biotech. 2016;6:2190–5738. doi: 10.1007/s13205-016-0443-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best A, et al. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genom. 2008;9:1–15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertels F, Silander OK, Pachkov M, Rainey PB, Van Nimwegen E. Automated reconstruction of whole-genome phylogenies from short-sequence reads. Mol Biol Evol. 2014;31:1077–1088. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msu088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–2120. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabañas K, García A. Producción de proteínas recombinantes en Bacillus megaterium: estado del arte. Icidca. 2015;49(1):22–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chun J, Oren A, Ventosa A, et al. Proposed minimal standards for the use of genome data for the taxonomy of prokaryotes. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:461–466. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn F. Untersuchungen Über Bakterien. Beitrage zur Biologie Pflanz. 1872;1:127–1224. [Google Scholar]

- de los Santos-Villalobos S, Parra-Cota FI, Herrera-Sepúlveda A, Valenzuela-Aragon B, Estrada-Mora JC. Colección de microorganismos edáficos y endófitos nativos para contribuir a la seguridad alimentaria nacional. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas. 2018;9:191–202. doi: 10.29312/remexca.v9i1.858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eppinger M, Bunk B, Johns MA, et al. Genome sequences of the biotechnologically important Bacillus megaterium strains QM B1551 and DSM319. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:4199–4213. doi: 10.1128/JB.00449-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espariz M, Zuljan FA, Esteban L, Magni C. Taxonomic identity resolution of highly phylogenetically related strains and selection of phylogenetic markers by using genome-scale methods: the Bacillus pumilus group case. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:1–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunnimalaiyaan M, Vary PS. Molecular characterization of plasmid pBM300 from Bacillus megaterium QM B1551. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71(6):3068–3076. doi: 10.1128/aem.71.6.3068-3076.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malanicheva IA, Kozlov DG, Sumarukova IG, et al. Antimicrobial activity of Bacillus megaterium strains. Microbiology. 2012;81:178–185. doi: 10.1134/S0026261712020063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier J, Auch A, Klenk H, Göker M. Genome sequence-based species delimitation with confidence intervals and improved distance functions. BMC Bioinform. 2013;14:1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-14-60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortíz R, Valencia E, López J. Plant growth promotion by Bacillus megaterium involves cytokinin signaling. Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3:263–265. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-2-0207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parte AC. LPSN—list of prokaryotic names with standing in nomenclature (bacterio.net), 20 years on. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2018;68:1825–1829. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.002786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissman AI, Mau B, Biehl BS, Darling AE, Glasner JD, Perna NT. Reordering contigs of draft genomes using the Mauve aligner. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2071–2073. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Aguirre JB, Oliver-Gómez LZ, de los Santos-Villalobos S, Sánchez ML. Production of polyhydroxybutyrate from milk whey fermentation by Bacillus megaterium TRQ8. Revista Latinoamericana de Recursos Naturales. 2017;13(1):24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Sharaf A, Oborník M, Hammad A, El-afifi S. Characterization and comparative genomic analysis of virulent and temperate Bacillus megaterium bacteriophages. PeerJ. 2018;6:1–24. doi: 10.7717/peerj.5687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thilagar G, Bagyaraj DJ, Podile AR, Vaikuntapu PR. Bacillus sonorensis, a novel plant growth promoting rhizobacterium in improving growth, nutrition and yield of chilly (Capsicum annuum L.) Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;88:813–818. doi: 10.1007/s40011-016-0822-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Valenzuela-Aragon B, Parra-Cota F, Santoyo G, Arellano G, de los Santos-Villalobos S. Plant-assisted selection: a promising alternative for in vivo identification of wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. Durum) growth promoting bacteria. Plant Soil. 2018;435:367–384. doi: 10.1007/s11104-018-03901-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese NJ, Mukherjee S, Ivanova N, Konstantinidis KT, Mavrommatis K, Kyrpides NC, Pati A. Microbial species delineation using whole genome sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6761–6771. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vielva L, de Toro M, Lanza V, de la Cruz F. PLACNETw: a web-based tool for plasmid reconstruction from bacterial genomes. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3796–3798. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villa-Rodriguez E, Ibarra C, de los Santos-Villalobos S. Extraction of high-quality RNA from Bacillus subtilis with a lysozyme pre-treatment followed by the Trizol method. J Microbiol Methods. 2018;147:14–16. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2018.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarreal-Delgado M, Villa E, Cira L, Estrada M, Parra F, de los Santos-Villalobos S. The genus Bacillus as a biological control agent and its implications in the agricultural biosecurity. Revista Mexicana de Fitopatología. 2018;36:95–130. doi: 10.18781/R.MEX.FIT.1706-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SH, Ha SM, Kwon S, Lim J, Kim Y, Seo H, Chun J. Introducing EzBioCloud: a taxonomically united database of 16S rRNA gene sequences and whole-genome assemblies. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2017;67:1613–1617. doi: 10.1099/ijsem.0.001755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SH, Ha S, Lim J, Kwon S, Chun J. A large-scale evaluation of algorithms to calculate average nucleotide identity. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2017;110:1281–1286. doi: 10.1007/s10482-017-0844-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.