Abstract

Sex differences in immunity are well described in the literature and thought to be mainly driven by sex hormones and sex-linked immune response genes. The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is one of the largest immune organs in the body and contains multiple immune cells in the GIT-associated lymphoid tissue, Peyer’s patches and elsewhere, which together have profound effects on local and systemic inflammation. The GIT is colonised with microbial communities composed of bacteria, fungi and viruses, collectively known as the GIT microbiota. The GIT microbiota drives multiple interactions locally with immune cells that regulate the homeostatic environment and systemically in diverse tissues. It is becoming evident that the microbiota differs between the sexes, both in animal models and in humans, and these sex differences often lead to sex-dependent changes in local GIT inflammation, systemic immunity and susceptibility to a range of inflammatory diseases. The sexually dimorphic microbiome has been termed the ‘microgenderome’. Herein, we review the evidence for the microgenderome and contemplate the role it plays in driving sex differences in immunity and disease susceptibility. We further consider the impact that biological sex might play in the response to treatments aimed at manipulating the GIT microbiota, such as prebiotics, live biotherapeutics, (probiotics, synbiotics and bacteriotherapies) and faecal microbial transplant. These alternative therapies hold potential in the treatment of both psychological (e.g., anxiety, depression) and physiological (e.g., irritable bowel disease) disorders differentially affecting males and females.

Keywords: Adaptive immunity, Innate immunity, Sex differences, Sex hormones, Probiotics, Faecal microbiota transplant, Bacteriotherapy

The healthy microbiota and its role in immune homeostasis

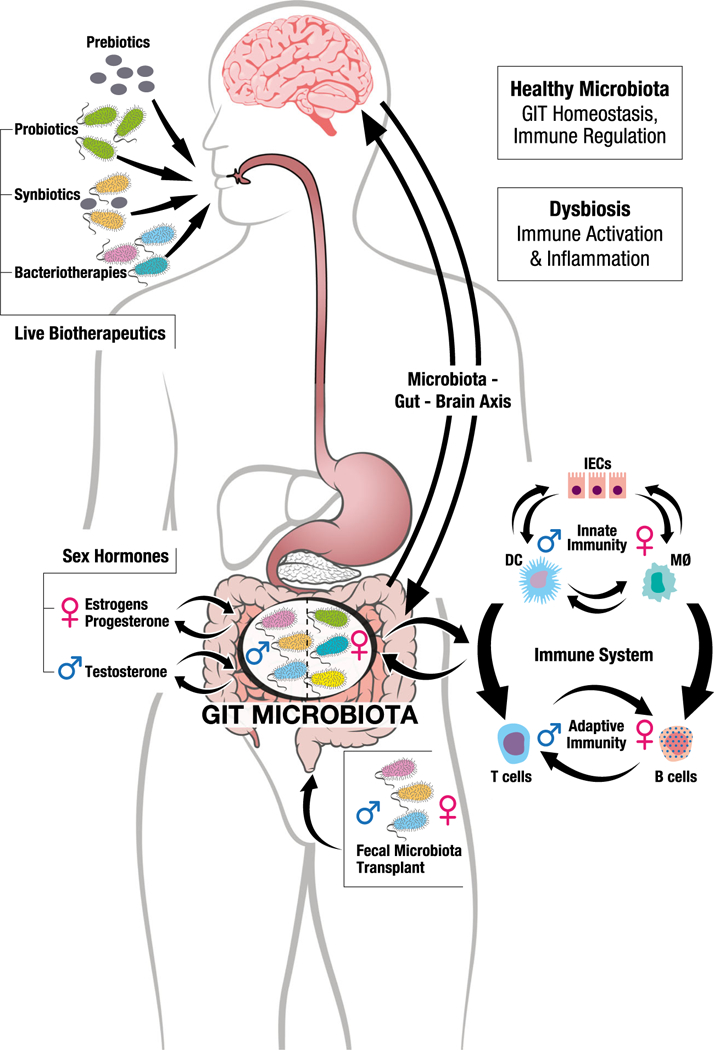

The intestinal mucosal interface is a site of intense immune homeostasis whereby antigens from food are surveyed and processed, and the balance between adverse inflammation and pathogen surveillance is maintained. The microbiota consists of commensal, symbiotic and pathogenic bacteria, as well as fungi and viruses, and the microbial genome of these microorganisms is termed the microbiome. The body contains at least an equal number of microbes as there are cells in the human body [1], with the majority of these microbes occurring in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT). The GIT is the largest immune organ in the body, and multiple studies have shown that these resident microbial communities, termed the GIT microbiota, can educate immune development and modulate host inflammatory status. This occurs via microbiota effects on both innate and adaptive immunity (Table 1; Fig. 1) [2–12, 15–29]. The microbiota differs depending on the region of the GIT (oesophagus, stomach, upper and lower intestine, colon), but this review will focus on the colonic microbiota where an estimated 70% of the GIT microbiota reside [4].

Table 1.

Effect of the GIT microbiota on innate and adaptive immunity

| Immune factor | How it is affected by the GIT microbiota | Refs |

|---|---|---|

| Innate immunity | ||

| Dendritic cells (DCs), macrophages in gut associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) |

Microbiota expression of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) stimulate pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) on DCs and macrophages including toll-like receptors (TLRs), nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing protein (NOD) receptors, retinoic acid-inducible gene-I-like (RIG-I-like) receptors, leading to downstream signalling events. Many GIT microbiota-induced innate responses are anti-inflammatory leading to homeostasis via the production of suppressive cytokines, such as IL-10 and TGF-β. |

[1–9] |

| Type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) | RORγt+ type 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILCs) are stimulated directly and indirectly by the GIT microbiota. |

[4, 10] |

| Invariant natural killer T cells (iNKT cells) | Induced by GIT microbiota to produce pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines, regulate neutrophil recruitment and function, important in GIT immune homeostasis |

[11] |

| Intestinal epithelial cells (IECs) | Microbiota PAMP-induced stimulation of PRRs leading to production of antimicrobial peptides, such as defensins, C-type lectins, and cathelicidins. |

[12] |

| Endocrine cells | Secrete serotonin and neuropeptides allowing crosstalk with the immune system | [12] |

| Adaptive immunity | ||

| Th1, Th2, Th17 immunity | GIT microbiota directly induces T helper 1 (Th1), Th2 and Th17 cells. | [13–17] |

| Regulatory T cells (Tregs) | Microbiota cause the generation of GIT and thymic-derived Tregs thereby maintaining tolerance. Bacterial-derived short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) induce Tregs. |

[18–24] |

| B cells and secretory IgA | GIT microbiota directly stimulates B cell development and regulates the generation of secretory IgA by plasma cells. |

[7, 25–28] |

| Regulatory B cells | GIT microbiota can induce CD5+ regulatory B cells in mice. | [29] |

Fig. 1.

The microgenderome revealed. The gastrointestinal tract (GIT) is a site of intense immune homeostasis in which the microbiota plays a pivotal role. Many studies show that the GIT microbiota differs in males and females. Likely causes include differing sex hormone levels in males and females, in part driven by sex differences in systemic sex hormone concentrations, but also influenced by the microbiota themselves. Sex differences in the microbiota composition drive sex differences in both innate and adaptive immunity, and the sex-differential innate and adaptive immune systems in turn drive sex differences in the microbiota composition. A normal, healthy microbiota allows immune homeostasis to be maintained, but loss of the healthy microbiota (dysbiosis) can drive inflammation and susceptibility to inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. Moreover, the GIT microbiota communicates with the brain and vice versa in what has been termed the microbiota-gut-brain axis, likely contributing to sex differences in susceptibility to a number of neuropsychiatric conditions. The response to therapeutic alteration of the microbiota using prebiotics, live biotherapeutics (probiotics, synbiotics and bacteriotherapies) or FMT is also likely to be different in males and females, although this has not been specifically studied to date. DC = dendritic cell, MØ = macrophage, IECs = intestinal epithelial cells

Healthy microbiota versus dysbiosis

Colonisation of the GIT commences at birth and early colonisation events (e.g., vaginal birth, antibiotics) are thought to have profound influences on GIT development, immune system function and metabolic homeostasis, thereby influencing long-term health and disease susceptibility [30]. For the purposes of this review, dysbiosis is an imbalanced or maladapted microbiota that can occur at any time in life and is often associated with localised or systemic inflammation (Fig. 1). A person’s healthy microbiota rarely leads to excessive local or systemic inflammation, and often, certain microbial communities are considered healthier than others, though this is not the same for each individual [31]. The mammalian GIT microbiota consists of three major phyla, namely the Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes and Actinobacteria [4]. The diversity of Bacteroidetes is limited, thus individual species are typically the dominant species by abundance. Bacteroidetes are thought to play an important role in degradation of complex sugars and proteins [32]. The Firmicutes, in contrast, contain the most diversity but typically occur at lower levels than Bacteroides [33]. The Actinobacteria are early colonisers associated with breast milk that persist and are detectable in most healthy people [34]. The most prevalent members of the Actinobacteria phyla are from the Bifidobacterium genus and include Prevotella and Faecalibacteria, which are typically associated with health in humans. On the other hand, Lactobacilliaceae (Firmicutes) are absent or occur at low levels in the healthy human GIT but are highly prevalent in the murine GIT. Indeed, while Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes dominate in the microbiota of many laboratory rodents (e.g., mice, rats, hamsters) [35–37], marked differences between the rodent and human GIT microbiota at the genus level indicate that rodent studies may not be generalizable to humans [38]. Furthermore, individual rodents may vary greatly in their microbiota even when co-housed; thus, rigorous experimental techniques are required to ensure consistency in experiments [39].

Importantly, certain bacteria, such as Bifidobacteriaceae (Actinobacteria), are thought to have anti-inflammatory effects [40]. By contrast, others including many members of the Lactobacilliaceae, such as Lactobacilus acidophilus [41], and Proteobacteria including Enterobacteriaceae [12] are highly pro-inflammatory. However, the picture is highly complex and it remains unclear whether the Proteobacteria drive inflammation or merely survive better in a pro-inflammatory environment than Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes [42]. Further, this greatly oversimplified view does not consider that the community of microbes (including viruses and fungi) interact in a cohesive way to maintain host homeostasis, a description of which is beyond the scope of this review.

Sex differences in the GIT microbiota and immunity—rodent studies

Sex differences in GIT microbiota

Many studies have shown that the GIT microbiota composition differs in adult male and female rodents [39, 43–46]. For example, while the pro-inflammatory Lactobacillaceae are more abundant in females, the highly pro-inflammatory Ruminococcaceae and Rikenellaceae are more prevalent in males [43]. Sex differences in composition, however, also depend on the species and strain being studied. For example, B6 females have greater Lactobacillaceae and Bacteroides than B6 males, whereas BALB/c females have greater Bifidobacteriaceae than BALB/c males [44]. These sex differences in the microbiota have been shown to correlate with sex differences in GIT expression of multiple genes controlling immunological function, including genes affecting inflammation and leukocyte migration [44]. For instance, in a study examining differential gene expression in the GIT mucosa, males had greater transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) signalling, and type 1 interferon (IFN) pathway regulation than females [43], further suggesting the important role sex plays in the microbiota-immunity interface.

Sex differences in the immunological effects of microbiota transfer

While the GIT microbiota shapes both innate and adaptive immune responses (Table 1), the reciprocal is also true in that the innate and adaptive immune systems can alter the composition of the local microbiota [47]. Thus, sex differences in systemic immunity are likely to contribute to sex differences in GIT microbiota and vice versa. A recent study addressed this reciprocal relationship by performing GIT microbiota transfer experiments from conventional [i.e., specific pathogen free (SPF)] to germ-free (GF) mice of the same or opposite sex, and examining effects on weight loss, organ-specific T and B cell immunity and gene expression in the GIT [43]. Female mice receiving female transplants maintained their normal body mass, whereas females receiving male microbiota or male recipients of either male or female microbiota lost weight, suggesting the female microbiota may be less pro-inflammatory, further confirmed by the analysis of local genes and pathways affected in these experiments [43]. The microbiota first adapts to the sex of the recipient, but by 4 weeks, some donor-specific sex differences become apparent [43]. Mice receiving female microbiota had higher levels of double-negative T cell precursors compared to mice receiving male microbiota, suggesting a sex-dependent effect of the GIT microbiota on T cell development [43]. However, there were no sex differences in T helper (Th) types Th1, Th2 or Th17 cell subsets in PP, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLNs) or spleens [43]. In another study, transfer ofmale microbiota to GF males led to greater RORγt+ Foxp3+ T cells (i.e. those that inhibit Th2 mediated pathology) in PP and MLN compared to male recipients of female microbiota [48], which may explain the greater propensity of females to food allergies.

The above transfer study also investigated the effect of the microbiota on antibody levels [43]. Notably, GF females had higher baseline antibodies (i.e. titers of IgM and IgE) compared to GF males, but similar levels to conventional females, suggesting that the microbiota may not influence specific aspects of immunity in females [43]. In contrast, GF males have lower baseline antibody titers (i.e. IgG2a and IgG2b) than conventional males, and the transfer of female microbiota significantly lowers IgA levels compared to male microbiota transfer, all supporting a microbiota-induced effect on antibodies in males [43]. However, these data do not confirm whether the microbiota influence how the immune system may respond to a true infection.

Sex differences prior to puberty

Most studies examining the role of sex in GIT microbiota have generally investigated adult animals. However, investigations of the GIT microbiota in young animals suggest that these microbial sex differences do not appear until after puberty [37]. For example, deep sequencing of the colonic luminal contents from pre-pubescent C57BL/6 mice show no effect of sex on colonic bacterial community composition [37]. In this study, however, whole-genome profiling of colonic and small intestinal tissue from pre-pubertal mice revealed multiple genes that exhibit sexually dimorphic expression, many of which were autosomal and involved in infection, immunity and inflammatory pathways, particularly in the small intestine [37]. Thus, even in the absence of high levels of circulating sex hormones, mice with identical microbiota have intrinsic sex-specific gene regulation in the GIT.

In summary, there are multiple descriptions of sex differences in the adult rodent microbiota, which in turn influence local and systemic immunity in a sex-specific manner. These include effects on innate and adaptive immunity generally that drive an anti-inflammatory GIT in females and a more inflammatory environment in males. How profound this effect is in contributing to sex differences in systemic immunity is not known at present but is likely to be considerable given the major contribution of the GIT microenvironment to immune homeostasis (Table 1).

Effect of the microbiota on sex-specific behaviour in rodents

Changes in the GIT microbiota can influence behaviour in sex-dependent ways, and many studies have supported the microbiota’s role in behavioural abnormalities (e.g., anxiety-like behaviour). For example, in Siberian hamsters, treatment with a broad-spectrum antibiotic not only affects faecal microbial communities in both sexes, but there is a strong sex difference in the behavioural response to treatment. Specifically, two, but not one, antibiotic treatment is associated with marked decreases in aggressive behaviour in males, but in females, there is a decrease in aggression after only a single treatment [36]. Further, Neufeld and colleagues showed that GF Swiss Webster mice exhibit decreased anxiety-like behaviour in the Elevated Plus Maze (EPM) (e.g., increased time spent in the open arm), which was accompanied by increased brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) expression and decreased serotonin receptor 1A (5HT1A) expression in the hippocampus compared to SPF mice [49]. In a separate study, male and female Swiss Webster mice spent less time near a conspecific, as well as less time investigating a novel conspecific, when compared with a familiar one, suggesting increased anxiety-like behaviour [50]. These contradictory data suggest that normal GIT microbial communities may modulate important neurotransmitters that can greatly influence behavioural responses in sex-dependent ways, yet the precise role of the microbiota in modulating these responses is not completely understood.

Sex hormones drive microbiota differences in rodent models

The lack of sex differences in pre-pubertal mice supports a role for sex hormones in driving sex differences in the microbiota. Sex hormones are known to have many immunological effects with estrogens generally being considered pro-inflammatory and androgens anti-inflammatory [51]. The GIT microbiota modulate the enterohepatic circulation of non-ovarian estrogens in men and post-menopausal women thereby affecting local and systemic sex hormone levels and likely act in the same manner across animal models [52].

Oestrogen receptors are expressed by murine intestinal macrophages and nerve cells as well, the former of which can be activated by exogenous oestrogen administration [53, 54]. Oestrogen therefore acts at multiple levels of the GIT and plays an important role in maintaining health or causing disease. Estrogens are implicated in driving experimental colitis in mouse models [55], although certain murine colitis models are not affected by estrogens [56].

Rodent studies further suggest that GIT bacteria regulate local production of testosterone leading to protection against the development of type 1 diabetes in male mice via altered IFN-γ and IL-1β-mediated signalling [57, 58]. Oral gavage of type 1 diabetes prone non-obese diabetic (NOD) females with male caecal contents increases testosterone levels in females and reduces insulinitis, insulin antibodies and disease incidence, an effect reversed by the anti-androgen drug flutamide [57]. A metabolomics analysis in this study showed that the sex of the microbiota differentially affected metabolic outcomes such as serum long-chain fatty acid levels. Again, these effects were abrogated by androgen receptor blockade suggesting that increased testosterone following male microbiota transfer was a key factor in the metabolomic effects. This provides direct evidence for a role for the GIT microbiota in influencing male sex hormone levels and altering autoimmune disease susceptibility. Androgens may similarly influence GIT microbial composition in lupus-susceptible mice and protect males against the development of lupus [47].

Sex differences in the GIT microbiota—human studies

Human studies have similarly shown that sex influences the GIT microbial composition, with the female microbiome having lower abundance of the Bacteroidetes phylum than males [59, 60]. A recent study showed sex differences in the GIT microbiome in a Japanese population; however, this was confounded by stool consistency, making it difficult to determine if this represents a biologically relevant difference or a sampling bias [61]. In conflict with these latter studies, a study investigating geographical variation in the microbiome among 1020 healthy individuals from 23 different populations across four continents found a similar abundance of Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes in males and females [62]. This study compiled data from six studies, and thus methodology and population differences may have masked a sex effect.

Healthy females reportedly have increased relative abundance of species in the Bacteroides genus than males in the GIT [63, 64]. In contrast, higher relative abundance of Escherichia [64] and Veillonella genera and lower relative abundance of the Bilophila genus have all been described in males [63]. However, another study showed increased Bacteroides in males compared to females [59]. B. fragilis, a member of the Bacteroides genus that is rarely prevalent in healthy individuals, activates T cell-dependent immune homeostatic mechanisms via the production of polysaccharide A, leading to Treg activation and suppression of Th17 responses and could therefore contribute to sex differences in immunity [13].

Generally, females have more robust innate and adaptive immune responses than males [51], but the role that the GIT microbiota plays in this effect is not known. Healthy adult females have greater immune activation and inflammation-associated gene expression in small intestine mucosal biopsy samples compared with males, in conjunction with higher peripheral blood T cell activation and proliferation and upregulated CD4 T cell IL-1β and Th17 pathway genes [14]. This suggests that gut inflammation drives systemic inflammation in a sex-specific manner even in healthy asymptomatic individuals and likely contributes to the superior immune systems of females.

Further, oestrogen levels in men and post-menopausal women directly correlate with GIT microbiome richness and diversity, whereas there is no correlation in pre-menopausal women who are at varying stages of the menstrual cycle [52]. In particular, Clostridia taxa and several Ruminococcaceae family members are affected, suggesting that GIT microbes influence levels of non-ovarian oestrogens via the enterohepatic circulation [52]. The human microbiota changes throughout the various stages of pregnancy further implicating a modulatory role for sex steroids [65]. Diversity appears to decrease throughout pregnancy while certain bacteria such as Proteobacteria and Actinobacteria increase in the majority of women, the former known to be associated with inflammatory mediated dysbiosis [66]. A study of diverse human populations (Venezuela, Malawi, USA) across the lifespan showed distinct changes in the microbiota at puberty further implicating a role for sex hormones [67]. In an investigation of American twins, no significant sex differences in microbiota relatedness among infant twin pairs of the same sex compared to the opposite sex were found. However, there was greater faecal microbiota dissimilarity in opposite sex teenage (13–17 years) twin pairs compared to same sex pairs, supporting microbiota sex differences in older individuals [67].

Additionally, microbial fermentation in the GIT leads to the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as buty-rate, propionate and acetate. These have a myriad of anti-inflammatory effects including induction of Tregs (Table 1), inhibition of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) activation and suppression of tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-α and IL-6 release [12]. Males have been shown to have higher serum SCFA levels compared to females [68], which may account for higher Tregs in males [51] and contribute to the lower systemic inflammatory status among males as compared to females [21–24].

The human microbiota-gut-brain axis and sex differences in behaviour

Changes in the GIT microbiota may also contribute to sex-specific behavioural abnormalities across clinical populations. For example, subsets of autism spectrum disorder patients (mostly male) show both changes in GIT microbial composition, as well as gastrointestinal symptoms [69]. Another study found that while the microbiota compositions were similar between the sexes, there were sex-specific interactions between the Firmicutes and myalgic encephalomyelitis (also known as chronic fatigue syndrome) symptoms, suggesting sex-specific functional effects of GIT microbiota [70]. This bidirectional crosstalk between the GIT and brain via neural, hormonal and immunological pathways, called the ‘microbiota-gut-brain axis’ (Fig. 1), has received considerable attention in recent years and may be associated with sex differences in a number of psychological and neurological conditions [69]. This gut-brain axis also provides the link between certain sexually dimorphic GIT disorders, such as the greater female susceptibility to irritable bowel syndrome and the behavioural comorbidities that occur with this disorder [71].

Diet, GIT transit and adiposity have sex-differential effects on GIT microbiota

A study specifically investigating the sex*diet interaction in four vertebrate species including fish, mice and humans confirmed that diet has a sex-specific effect on the GIT microbiome in humans and two species of fish, but no such interactions were apparent in laboratory mice fed a standard controlled diet [72]. Interestingly, dietary effects were not observed in fish if the statistical models failed to account for sex, illustrating the importance of taking sex into account in studies of GIT microbiota. The impact of dietary fibre intake on the microbiome composition also appears sexually dimorphic [60], possibly via the effects of fibre on oestrogen levels [73] Furthermore, adipose tissue is a source of sex hormones [74] and several studies suggest that adipose tissue contributes to sex differences in the GIT microbiota [32, 75]. Importantly, focusing on sex differences, particularly estradiol and testosterone, can provide information on the regulation and motor function (e.g. transit time) in the GIT and ultimately the normal function of the GIT microbiome. Indeed, faster GIT transit in females as compared to males is thought to contribute to sex differences in the GIT microbiota [76, 77].

Dysbiosis triggers diseases that manifest differently in the sexes

Increasing evidence suggests that GIT dysbiosis can lead to a preferential skewing towards effector T cell development and trigger inflammatory and autoimmune diseases [47]. In some cases, the same bacteria may provide protection against certain conditions and predisposition to others. For example, segmented filamentous bacteria may predispose individuals to Th17-mediated diseases and asthma in murine studies [78, 79] but can protect against type 1 diabetes in NOD mice [80]. Intestinal dysbiosis has also been linked to systemic lupus erythematosis [81, 82], and it is speculated that sex differences in the GIT microbiota play a role in the greater female susceptibility to autoimmune diseases [57, 58, 83].

The GIT microbiota can also affect sites distant to the GIT. For instance, Clostridium leptum can induce protection against allergic airways disease via the induction and/ or activation of Tregs [84]. Changes in the GIT microbiota composition, specifically altered anaerobes and facultative anaerobes, can be linked to the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in female but not male mice, including increased abundances of Allobaculum, Erysipelotrichaceae, Neisseriaceae, Sutterella, Burkholderiales and Prevotella species [85]. The microbiota has been linked to sex differences in susceptibility to cardiometabolic syndromes as well [86].

Treatments for dysbiosis should consider the sex of the recipient

Prebiotic, probiotic and symbiotic therapy

There is increasing interest in manipulating the host microbiota to treat diseases that result from dysbiosis [1], but few studies have taken recipient sex into account. Administration of a probiotic mixture of five Lactobacillus strains to lupusprone mice improved renal function and had anti-inflammatory effects by lowering IL-6, IgG2a and IgA and increasing the levels of IL-10 in female and castrated male mice, but not in gonadally intact males [82]. Another probiotic mixture has been used to prevent cortical bone loss in female mice [87], and a different probiotic prevented bone loss in oestrogen-deficient mice after ovariectomy via anti-TNF factors [88]. Interestingly, supplementation of aged obese mice with the probiotic L. reuteri helped restore testosterone levels and decreased IL-17 levels in males [89], suggesting the important role that age plays in the response to shifts in microbial communities. Understanding host metabolism will be vital to treatment success. Male and female rodents, for example, metabolise a diet supplemented with the prebiotic oligofructose (OF) differently, with females having higher levels of Bacteroidetes compared to males [90]. Faecal buty-rate levels are also increased in males, and liver IgA, IL-6 and caecal IL-6 levels are higher in males, while anti-inflammatory IL-10 levels are higher in females [90]. Further, mice given an oral anti-ageing oil treatment show sex-based differences in GIT microbiota modulation [46]. Collectively, these studies point to sex differences in the immunological effects of pre- and probiotic treatments and may hold great potential in the treatment of microbiota-associated disease (Fig. 1).

In a study specifically designed to examine the effect of sex on host immunity following Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis (MAP) challenge in mice either fed the probiotic Lactobacillus animalis or control fed, circulating cytokines (e.g. IL-1α/β, IL-6, IFN-γ) differed between the sexes [91]. This suggests that Th1, Th2, Th17 and Tregs may all be regulated by sex-linked factors in the mouse GIT. Furthermore, females show an increase in Firmicutes, including Staphylococcus and Roseburia, in all groups except controls [91] indicating that male and female microbiota respond differently to certain dietary organisms, and that the female microbiota may be more susceptible to dietary manipulation than males. In an extension of these studies, the same authors examined cytokine transcription levels and found that males have greater expression of Th2 and B cell factors, while females have decreased pro-inflammatory cytokine expression after MAP infection [91]. Further, male mice show increased Tgf-β, Il-10 and Foxp3 expression (indicative of Treg induction) and Il-17 and Il-23A (typical of Th17 responses). Presumably, these sex differences in gene transcription modulate T cell function via cytokine-dependent mechanisms.

FMT and bacteriotherapies

Faecal microbial transplant (FMT) is becoming of increasing interest as a treatment for multiple conditions associated with GIT dysbiosis in humans (Fig. 1). In particular, FMT has been used for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated colitis [88], but studies indicate that it may also be used to treat inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, obesity, diabetes, depression and anxiety [92–95]. As described above, all these conditions can be sex-dependent and associated with sex differences in the GIT microbiota. One study showed sex differences in mouse GIT microbiota colonisation after receiving FMTs from a male on a short-term vegetarian and inulin-supplemented diet, demonstrating that males and females utilise the same microbiota differently [96]. Murine FMT was also reported to protect against radiation-induced toxicity in a sex-specific manner thereby improving the prognosis of tumour patients after radiotherapy [97]. To our knowledge, no one has suggested that the sex of the donor should be considered when screening for suitability as an FMT donor, but the studies in this paper indicate that this could be an important consideration. Indeed, a recent human study found that female sex was associated with failure of FMT to cure C. difficile infection [98]. Advances in methods of cultivation, measurement and preparation of gastrointestinal bacteria are now progressing research from FMT to the development of rationally selected mixtures of bacteria with proven therapeutic efficacy, termed bacteriotherapies. This approach overcomes the issues of disease risk, patient acceptability and ease of delivery associated with FMT; however, consideration of sex differences may also prove essential in the design of these therapeutic options.

Concluding remarks

Flak and colleagues introduced the concept of the microgenderome in 2013 to define the interaction between the microbiota, sex hormones and immunity [99], but since that time, the concept has not been widely adopted. Indeed, because gender is a social construct, and sex is a biological construct, the term ‘microgenderome’ may not be accurate because most of the factors driving male-female differences in the microbiota are determined by biological sex rather than gender. Whatever term is used moving forward, there is no doubt that there are sex differences in GIT microbial composition and function, in part driven by sex hormones, and these in turn contribute to sex differences in immunity and susceptibility to a multitude of infections and chronic diseases. Understanding the role of the GIT microbiota in the development of chronic inflammatory diseases may have major therapeutic implications in the future. This therefore leaves little doubt that studies of the microbiota should take sex into consideration, as should therapeutic manipulation of the microbiota with pre-, pro-, syn- and post-biotics, since it is likely the sexes will respond differently to these treatments.

It should be borne in mind that the majority of these studies used 16s rRNA profiling to determine the microbiota composition. This approach is unable to provide the species and strain resolution generally required for detailed understanding of bacterial diversity [100]. With the wider adoption of metagenomic sequencing, standardised data reporting and more sophisticated bioinformatics tools alongside novel culture techniques, we should get a far better picture of the nature of sex differences in microbial communities [33, 100–102].

The studies reviewed herein support sex differences in microbiota, as well as sex-specific responses to the same microbiota. These data show that the microbiota can influence the immune, endocrine and metabolic systems in hosts. Further, the microbiota can affect susceptibility to autoimmune, psychiatric and neuro-inflammatory conditions in a sex-specific manner, likely contributing to male/female disparities in susceptibility to these conditions. The relationship between the microbiota, hormones, metabolism and immunity appears multi-directional, with dysbiosis causing systemic imbalance in these factors and systemic imbalance leading to dysbiosis. Collectively, these studies provide evidence that future investigations into the composition and function of the microbiota must continue partitioning data for sex-differential interactions to understand these intricate relationships more fully.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Claudio Rosa for designing the figure.

Funding KES was supported by the NIH/NIAID Center of Excellence in Influenza Research and Surveillance contracts HHS N272201400007C; SCF is supported by NHMRC CJ Martin Fellowship (1091097) and the Victorian Government’s Operational Infrastructure Support Program; MP is supported by a NHMRC Senior Research Fellowship. RE and KLF are recipients of a grant from the Clifford Craig Foundation for microbiota research.

Abbreviations

- DC

dendritic cell

- MØ

macrophage

- IECs

intestinal epithelial cells

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Tran J, Wilson K, Plebanski M, Flanagan KL (2017) Manipulating the microbiota to improve human health throughout life. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 111:379–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weng M, Walker WA (2013) The role of gut microbiota in programming the immune phenotype. J Dev Orig Health Dis 4:203–214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fawkner-Corbett D, Simmons A, Parikh K (2017) Microbiome, pattern recognition receptor function in health and inflammation. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 31:683–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jandhyala SM, Talukdar R, Subramanyam C, Vuyyuru H, Sasikala M, Nageshwar Reddy D (2015) Role of the normal gut microbiota. World J Gastroenterol 21:8787–8803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swiatczak B, Rescigno M (2012) How the interplay between antigen presenting cells and microbiota tunes host immune responses in the gut. Semin Immunol 24:43–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rakoff-Nahoum S, Paglino J, Eslami-Varzaneh F, Edberg S, Medzhitov R (2004) Recognition of commensal microflora by toll-like receptors is required for intestinal homeostasis. Cell 118:229–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sjogren YM, Tomicic S, Lundberg A, Bottcher MF, Bjorksten B, Sverremark-Ekstrom E, Jenmalm MC (2009) Influence of early gut microbiota on the maturation of childhood mucosal and systemic immune responses. Clin Exp Allergy 39:1842–1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeuthen LH, Fink LN, Frokiaer H (2008) Epithelial cells prime the immune response to an array of gut-derived commensals towards a tolerogenic phenotype through distinct actions of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and transforming growth factor-beta. Immunology 123:197–208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghorpade DS, Kaveri SV, Bayry J, Balaji KN (2011) Cooperative regulation of NOTCH1 protein-phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling by NOD1, NOD2, and TLR2 receptors renders enhanced refractoriness to transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta)- or cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4)-mediated impairment of human dendritic cell maturation. J Biol Chem 286:31347–31360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 10.Mao K, Baptista AP, Tamoutounour S, Zhuang L, Bouladoux N, Martins AJ, Huang Y, Gerner MY, Belkaid Y, Germain RN (2018) Innate and adaptive lymphocytes sequentially shape the gut microbiota and lipid metabolism. Nature 554:255–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen S, Prame Kumar K, Stanley D, Moore RJ, Van TTH, Wen SW, Hickey MJ, Wong CHY (2018) Invariant natural killer T cells shape the gut microbiota and regulate neutrophil recruitment and function during intestinal inflammation. Front Immunol 9:999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiippala K, Jouhten H, Ronkainen A, Hartikainen A, Kainulainen V, Jalanka J, Satokari R (2018) The potential of gut commensals in reinforcing intestinal barrier function and alleviating inflammation. Nutrients 10(8) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Round JL, Lee SM, Li J, Tran G, Jabri B, Chatila TA, Mazmanian SK (2011) The toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiota. Science 332:974–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sankaran-Walters S, Macal M, Grishina I, Nagy L, Goulart L, Coolidge K, Li J, Fenton A, Williams T, Miller MK, Flamm J, Prindiville T, George M, Dandekar S (2013) Sex differences matter in the gut: effect on mucosal immune activation and inflammation. Biol Sex Differ 4:10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Rakotobe S, Lecuyer E, Mulder I, Lan A, Bridonneau C, Rochet V, Pisi A, De Paepe M, Brandi G, Eberl G, Snel J, Kelly D, Cerf-Bensussan N (2009) The key role of segmented filamentous bacteria in the coordinated maturation of gut helper T cell responses. Immunity 31:677–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ivanov II, Atarashi K, Manel N, Brodie EL, Shima T, Karaoz U, Wei D, Goldfarb KC, Santee CA, Lynch SV, Tanoue T, Imaoka A, Itoh K, Takeda K, Umesaki Y, Honda K, Littman DR (2009) Induction of intestinal Th17 cells by segmented filamentous bacteria. Cell 139:485–498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Shima T, Imaoka A, Kuwahara T, Momose Y, Cheng G, Yamasaki S, Saito T, Ohba Y, Taniguchi T, Takeda K, Hori S, Ivanov II, Umesaki Y, Itoh K, Honda K (2011) Induction of colonic regulatory T cells by indigenous Clostridium species. Science 331:337–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lathrop SK, Bloom SM, Rao SM, Nutsch K, Lio CW, Santacruz N, Peterson DA, Stappenbeck TS, Hsieh CS (2011) Peripheral education of the immune system by colonic commensal microbiota. Nature 478:250–254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cebula A, Seweryn M, Rempala GA, Pabla SS, Mclndoe RA, Denning TL, Bry L, Kraj P, Kisielow P, Ignatowicz L (2013) Thymus-derived regulatory T cells contribute to tolerance to commensal microbiota. Nature 497:258–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sefik E, Geva-Zatorsky N, Oh S, Konnikova L, Zemmour D, McGuire AM, Burzyn D, Ortiz-Lopez A, Lobera M, Yang J, Ghosh S, Earl A, Snapper SB, Jupp R, Kasper D, Mathis D, Benoist C (2015) MUCOSAL IMMUNOLOGY. Individual intestinal symbionts induce a distinct population of RORgamma(+) regulatory T cells. Science 349:993–997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arpaia N, Campbell C, Fan X, Dikiy S, van der Veeken J, deRoos P, H L CJR, Pfeffer K, Coffer PJ, Rudensky AY (2013) Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature 504:451–455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, Endo TA, Nakato G, Takahashi D, Nakanishi Y, Uetake C, Kato K, Kato T, Takahashi M, Fukuda NN, Murakami S, Miyauchi E, Hino S, Atarashi K, Onawa S, Fujimura Y, Lockett T, Clarke JM, Topping DL, Tomita M, Hori S, Ohara O, Morita T, Koseki H, Kikuchi J, Honda K, Hase K, Ohno H (2013) Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature 504:446–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith PM, Howitt MR, Panikov N, Michaud M, Gallini CA, Bohlooly YM, Glickman JN, Garrett WS (2013) The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science 341:569–573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh N, Gurav A, Sivaprakasam S, Brady E, Padia R, Shi H, Thangaraju M, Prasad PD, Manicassamy S, Munn DH, Lee JR, Offermanns S, Ganapathy V (2014) Activation of Gpr109a, receptor for niacin and the commensal metabolite butyrate, suppresses colonic inflammation and carcinogenesis. Immunity 40:128–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Suzuki K, Ha SA, Tsuji M, Fagarasan S (2007) Intestinal IgA synthesis: a primitive form of adaptive immunity that regulates microbial communities in the gut. Semin Immunol 19:127–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith K, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ (2007) Use of axenic animals in studying the adaptation of mammals to their commensal intestinal microbiota. Semin Immunol 19:59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ibnou-Zekri N, Blum S, Schiffrin EJ, von der Weid T (2003) Divergent patterns of colonization and immune response elicited from two intestinal Lactobacillus strains that display similar properties in vitro. Infect Immun 71:428–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gronlund MMAH, Kero P, Lehtonen OP, Isolauri E (2000) Importance ofintestinal colonisation in the maturation ofhumoral immunity in early infancy: a prospective follow up study of healthy infants aged 0–6 months. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 83:186–192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ochoa-Reparaz J, Mielcarz DW, Haque-Begum S, Kasper LH (2010) Induction of a regulatory B cell population in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by alteration of the gut commensal microflora. Gut Microbes 1:103–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nash MJ, Frank DN, Friedman JE (2017) Early microbes modify immune system development and metabolic homeostasis—the “restaurant” hypothesis revisited. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 8:349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Valdes AM, Walter J, Segal E, Spector TD (2018) Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. Brit Med J 361:k2179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI (2006) Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature 444: 1022–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Browne HP, Forster SC, Anonye BO, Kumar N, Neville BA, Stares MD, Goulding D, Lawley TD (2016) Culturing of ‘unculturable’ human microbiota reveals novel taxa and extensive sporulation. Nature 533(7604):543–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Scholtens PA, Oozeer R, Martin R, Amor KB, Knol J (2012) The early settlers: intestinal microbiology in early life. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol 3:425–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Condliffe SB, Doolan CM, Harvey BJ (2001) 17beta-oestradiol acutely regulates Cl- secretion in rat distal colonic epithelium. J Physiol 530(Pt 1):47–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sylvia KE, Jewell CP, Rendon NM, St John EA, Demas GE (2017) Sex-specific modulation of the gut microbiome and behavior in Siberian hamsters. Brain Behav Immun 60:51–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steegenga WT, Mischke M, Lute C, Boekschoten MV, Pruis MG, Lendvai A, Verkade HJ, Boekhorst J, Timmerman HM, Plösch T, Müller M (2014) Sexually dimorphic characteristics of the small intestine and colon of prepubescent C57BL/6 mice. Biol Sex Differ 5:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiao L, Feng Q, Liang S, Sonne SB, Xia Z, Qiu X, Li X, Long H, Zhang J, Zhang D, Liu C, Fang Z, Chou J, Glanville J, Hao Q, Kotowska D, Colding C, Licht TR, Wu D, Yu J, Sung JJ, Liang Q, Li J, Jia H, Lan Z, Tremaroli V, Dworzynski P, Nielsen HB, Backhed F, Dore J, Le Chatelier E, Ehrlich SD, Lin JC, Arumugam M, Wang J, Madsen L, Kristiansen K (2015) A catalog of the mouse gut metagenome. Nat Biotechnol 33:1103–1108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miyoshi J, Leone V, Nobutani K, Musch MW, Martinez-Guryn K, Wang Y, Miyoshi S, Bobe AM, Eren AM, Chang EB (2018) Minimizing confounders and increasing data quality in murine models for studies of the gut microbiome. Peer J 6:e5166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martino DJ, Currie H, Taylor A, Conway P, Prescott SL (2008) Relationship between early intestinal colonization, mucosal immunoglobulin A production and systemic immune development. Clin Exp Allergy 38:69–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiss G, Forster S, Irving A, Tate M, Ferrero RL, Hertzog P, Frokiaer H, Kaparakis-Liaskos M (2013) Helicobacter pylori VacA suppresses Lactobacillus acidophilus-induced interferon beta signaling in macrophages via alterations in the endocytic pathway. MBio 4:e00609–e00612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shin NR, Whon TW, Bae JW (2015) Proteobacteria: microbial signature of dysbiosis in gut microbiota. Trends Biotechnol 33: 496–503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fransen F, van Beek AA, Borghuis T, Meijer B, Hugenholtz F, van der Gaast-de Jongh C, Savelkoul HF, de Jonge MI, Faas MM, Boekschoten MV, Smidt H, El Aidy S, de Vos P (2017) The impact of gut microbiota on gender-specific differences in immunity. Front Immunol 8:754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elderman M, Hugenholtz F, Belzer C, Boekschoten M, van Beek de Haan B, Savelkoul H, de Vos P, Faas M (2018) Sex and strain dependent differences in mucosal immunology and microbiota composition in mice. Biol Sex Differ 9:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maurice CF, Knowles SC, Ladau J, Pollard KS, Fenton A, Pedersen AB, Turnbaugh PJ (2015) Marked seasonal variation in the wild mouse gut microbiota. ISME J 9:2423–2434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang H, Wang Z, Li Y, Han J, Cui C, Lu C, Zhou J, Cheong L, Li Y, Sun T, Zhang D, Su X (2018) Sex-based differences in gut microbiota composition in response to tuna oil and algae oil supplementation in a D-galactose-induced aging mouse model. Front Aging Neurosci 10:187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kosiewicz MM, Dryden GW, Chhabra A, Alard P (2014) Relationship between gut microbiota and development of T cell associated disease. FEBS Lett 588:4195–4206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohnmacht C, Park J-H, Cording S, Wing JB, Atarashi K, Obata Y, Gaboriau-Routhiau V, Marques R, Dulauroy S, Fedoseeva M, Busslinger M, Cerf-Bensussan N, Boneca IG, Voehringer D, Hase K, Honda K, Sakaguchi S, Eberl G (2015) Mucosal immunology. The microbiota regulates type 2 immunity through RORγt+ T cells. Science 349:989–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Neufeld KM, Kang N, Bienenstock J, Foster JA (2011) Reduced anxiety-like behavior and central neurochemical change in germ-free mice. Neurogastroenterol Motil 23(255–64):e119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Desbonnet L, Clarke G, Shanahan F, Dinan TG, Cryan JF (2014) Microbiota is essential for social development in the mouse. Mol Psychiatry 19:146–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Klein SL, Flanagan KL (2016) Sex differences in immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol 16:626–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Flores R, Shi J, Fuhrman B, Xu X, Veenstra TD, Gail MH, Gajer P, Ravel J, Goedert JJ (2012) Fecal microbial determinants of fecal and systemic estrogens and estrogen metabolites: a cross-sectional study. J Transl Med 10:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kawano N, Koji T, Hishikawa Y, Murase K, Murata I, Kohno S (2004) Identification and localization of estrogen receptor alpha- and beta-positive cells in adult male and female mouse intestine at various estrogen levels. Histochem Cell Biol 121:399–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hogan AM, Collins D, Baird AW, Winter DC (2009) Estrogen and its role in gastrointestinal health and disease. Int J Color Dis 24: 1367–1375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bábíčková J, Tóthová E, Lengyelová E, Bartoňová A, Hodosy J, Gardlík R, Celec P (2015) Sex differences in experimentally induced colitis in mice: a role for estrogens. Inflammation 38:1996–2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verdú EF, Deng Y, Bercik P, Collins SM (2002) Modulatory effects of estrogen in two murine models of experimental colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 283:G27–G36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Markle JGM, Frank DN, Mortin-Toth S, Robertson CE, Feazel LM, Rolle-Kampczyk U, von Bergen M, McCoy KD, Macpherson AJ, Danska JS (2013) Sex differences in the gut microbiome drive hormone-dependent regulation of autoimmunity. Science 339:1084–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yurkovetskiy L, Burrows M, Khan AA, Graham L, Volchkov P, Becker L, Antonopoulos D, Umesaki Y, Chervonsky AV (2013) Gender bias in autoimmunity is influenced by microbiota. Immunity 39:400–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mueller S, Saunier K, Hanisch C, Norin E, Alm L, Midtvedt T, Cresci A, Silvi S, Orpianesi C, Verdenelli MC, Clavel T, Koebnick C, Zunft HJ, Dore J, Blaut M (2006) Differences in fecal microbiota in different European study populations in relation to age, gender, and country: a cross-sectional study. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:1027–1033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dominianni C, Sinha R, Goedert JJ, Pei Z, Yang L, Hayes RB, Ahn J (2015) Sex, body mass index, and dietary fiber intake influence the human gut microbiome. PLoS One 10:e0124599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Takagi T, Naito Y, Inoue R, Kashiwagi S, Uchiyama K, Mizushima K, Tsuchiya S, Dohi O, Yoshida N, Kamada K, Ishikawa T, Handa O, Konishi H, Okuda K, Tsujimoto Y, Ohnogi H, Itoh Y (2018) Differences in gut microbiota associated with age, sex, and stool consistency in healthy Japanese subjects. J Gastroenterol Epub ahead of print [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suzuki TA, Worobey M (2014) Geographical variation of human gut microbial composition. Biol Lett 10:20131037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Haro C, Rangel-Zúñiga O, Alcalá-Díaz J, Gómez-Delgado F, Pérez-Martínez P, Delgado-Lista J, Quintana-Navarro GM, Landa BB, Navas-Cortés JA, Tena-Sempere M, Clemente JC, López-Miranda J, Pérez-Jiménez F, Camargo A (2016) Intestinal microbiota is influenced by gender and body mass index. PLoS One 11:e0154090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Singh P, Manning SD (2016) Impact of age and sex on the composition and abundance of the intestinal microbiota in individuals with and without enteric infections. Ann Epidemiol 26:380–385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Koren O, Goodrich JK, Cullender TC, Spor A, Laitinen K, Bäckhed HK, Gonzalez A, Werner JJ, Angenent LT, Knight R, Bäckhed F, Isolauri E, Salminen S, Ley RE (2012) Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy. Cell 150:470–480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mukhopadhya I, Hansen R, El-Omar EM, Hold GL (2012) IBD— what role do Proteobacteria play? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9:219–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yatsunenko T, Rey FE, Manary MJ, Trehan I, Dominguez-Bello MG, Contreras M, Magris M, Hidalgo G, Baldassano RN, Anokhin AP, Heath AC, Warner B, Reeder J, Kuczynski J, Caporaso JG, Lozupone CA, Lauber C, Clemente JC, Knights D, Knight R, Gordon JI (2012) Human gut microbiome viewed across age and geography. Nature 486:222–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Jakobsdottir G, Bjerregaard JH, Skovbjerg H, Nyman M (2013) Fasting serum concentration of short-chain fatty acids in subjects with microscopic colitis and celiac disease: no difference compared with controls, but between genders. Scand J Gastroenterol 48:696–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mulle JG, Sharp WG, Cubells JF (2013) The gut microbiome: a new frontier in autism research. Curr Psychiatry Rep 15:337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wallis A, Butt H, Ball M, Lewis DP, Bruck D (2016) Support for the microgenderome: associations in a human clinical population. Sci Rep 6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pigrau M, Rodino-Janeiro BK, Casado-Bedmar M, Lobo B, Vicario M, Santos J, Alonso-Cotoner C (2016) The joint power of sex and stress to modulate brain-gut-microbiota axis and intestinal barrier homeostasis: implications for irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil 28:463–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bolnick DI, Snowberg LK, Hirsch PE, Lauber CL, Org E, Parks Lusis AJ, Knight R, Caporaso JG, Svanback R (2014) Individual diet has sex-dependent effects on vertebrate gut microbiota. Nat Commun 5:4500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gaskins AJ, Mumford SL, Zhang C, Wactawski-Wende J, Hovey KM, Whitcomb BW, Howards PP, Perkins NJ, Yeung E, Schisterman EF, BioCycle Study G (2009) Effect of daily fiber intake on reproductive function: the BioCycle study. Am J Clin Nutr 90:1061–1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bulun SE, Chen D, Moy I, Brooks DC, Zhao H (2012) Aromatase, breast cancer and obesity: a complex interaction. Trends Endocrinol Metab 23:83–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Turnbaugh PJ, Hamady M, Yatsunenko T, Cantarel BL, Duncan A, Ley RE, Sogin ML, Jones WJ, Roe BA, Affourtit JP, Egholm M, Henrissat B, Heath AC, Knight R, Gordon JI (2009) A core gut microbiome in obese and lean twins. Nature 457:480–484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lampe JW, Fredstrom SB, Slavin JL, Potter JD (1993) Sex differences in colonic function: a randomised trial. Gut 34:531–536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Degen LP, Phillips SF (1996) Variability of gastrointestinal transit in healthy women and men. Gut 39:299–305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stepankova R, Powrie F, Kofronova O, Kozakova H, Hudcovic T, Hrncir T, Uhlig H, Read S, Rehakova Z, Benada O, Heczko P, Strus M, Bland P, Tlaskalova-Hogenova H (2007) Segmented filamentous bacteria in a defined bacterial cocktail induce intestinal inflammation in SCID mice reconstituted with CD45RBhigh CD4+ T cells. Inflamm Bowel Dis 13:1202–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu HJ, Ivanov II, Darce J, Hattori K, Shima T, Umesaki Y, Littman DR, Benoist C, Mathis D (2010) Gut-residing segmented filamentous bacteria drive autoimmune arthritis via T helper 17 cells. Immunity 32:815–827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kriegel MA, Sefik E, Hill JA, Wu HJ, Benoist C, Mathis D (2011) Naturally transmitted segmented filamentous bacteria segregate with diabetes protection in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci US A 108:11548–11553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hevia A, Milani C, Lopez P, Cuervo A, Arboleya S, Duranti S, Turroni F, González S, Suárez A, Gueimonde M, Ventura M, Sánchez B, Margolles A (2014) Intestinal dysbiosis associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. MBio 5:e01548–e01514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mu Q, Zhang H, Liao X, Lin K, Liu H, Edwards MR, Ahmed SA, Yuan R, Li L, Cecere TE, Branson DB (2017) Control of lupus nephritis by changes of gut microbiota. Microbiome 5:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Gomez A, Luckey D, Taneja V (2015) The gut microbiome in autoimmunity: sex matters. Clin Immunol 159:154–162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Li YN, Huang F, Liu L, Qiao HM, Li Y, Cheng HJ (2012) Effect of oral feeding with Clostridium leptum on regulatory T-cell responses and allergic airway inflammation in mice. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 109:201–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Huang R, Li T, Ni J, Bai X, Gao Y, Li Y, Zhang P, Gong Y (2018) Different sex-based responses of gut microbiota during the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in liver-specific Tscl-knock-out mice. Front Microbiol 9:1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Cross TL, Kasahara K, Rey FE (2018) Sexual dimorphism of cardiometabolic dysfunction: gut microbiome in the play? Mol Metab 5:e01548–e01514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ohlsson C, Engdahl C, Fåk F, Andersson A, Windahl SH, Farman HH, Movérare-Skrtic S, Islander U, Sjögren K (2014) Probiotics protect mice from ovariectomy-induced cortical bone loss. PLoS One 9:e92368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Britton RA, Irwin R, Quach D, Schaefer L, Zhang J, Lee T, Parameswaran N, McCabe LR (2014) Probiotic L. reuteri treatment prevents bone loss in a menopausal ovariectomized mouse model. J Cell Physiol 229:1822–1830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Poutahidis T, Springer A, Levkovich T, Qi P, Varian BJ, Lakritz JR Ibrahim YM, Chatzigiagkos A, Alm EJ, Erdman SE (2014) Probiotic microbes sustain youthful serum testosterone levels and testicular size in aging mice. PLoS One 9:e84877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Shastri P, McCarville J, Kalmokoff M, Brooks SP, Green-Johnson JM (2015) Sex differences in gut fermentation and immune parameters in rats fed an oligofructose-supplemented diet. Biol Sex Differ 6:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Karunasena E, McMahon KW, Chang D, Brashears MM (2014) Host responses to the pathogen Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis and beneficial microbes exhibit host sex specificity. Appl Environ Microbiol 80:4481–4490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bakker GJ, Nieuwdorp M (2017) Fecal microbiota transplantation: therapeutic potential for a multitude of diseases beyond Clostridium difficile. Microbiol Spectr 5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.de Groot PF, Frissen MN, de Clercq NC, Nieuwdorp M (2017) Fecal microbiota transplantation in metabolic syndrome: history, present and future. Gut Microbes 8:253–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Singh B, Qin N, Reid G (2015) Microbiome regulation of autoimmune, gut and liver associated diseases. Inflamm Allergy Drug Targets 14:84–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kurokawa S, Kishimoto T, Mizuno S, Masaoka T, Naganuma M, Liang KC, Kitazawa M, Nakashima M, Shindo C, Suda W, Hattori M, Kanai T, Mimura M (2018) The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhea and functional constipation: an open-label observational study J Affect Disord 235: 506–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang JJ, Wang J, Pang XY, Zhao LP, Tian L, Wang XP (2016) Sex differences in colonization of gut microbiota from a man with short-term vegetarian and inulin-supplemented diet in germ-free mice. Sci Rep 6:36137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Cui M, Xiao H, Li Y, Zhou L, Zhao S, Luo D, Zheng Q, Dong J, Zhao Y, Zhang X, Zhang J (2017) Faecal microbiota transplantation protects against radiation-induced toxicity. EMBO Mol Med 9:448–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Duarte-Chavez R, Wojda TR, Zanders TB, Geme B, Fioravanti G, Stawicki SP (2018) Early results of fecal microbial transplantation protocol implementation at a community-based university hospital. J Glob Infect Dis 10:47–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Flak MB, Neves JF, Blumberg RS (2013) Welcome to the microgenderome. Science 339:1044–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Neville BA, Forster SC, Lawley TD (2018) Commensal Koch’s postulates: establishing causation in human microbiota research. Curr Opin Microbiol 42:47–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Forster SC, Browne HP, Kumar N, Hunt M, Denise H, Mitchell A, Finn RD, Lawley TD (2016) HPMCD: the database of human microbial communities from metagenomic datasets and microbial reference genomes. Nucleic Acids Res 44:D604–D609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mitchell AL, Scheremetjew M, Denise H, Potter S, Tarkowska A, Qureshi M, Salazar GA, Pesseat S, Boland MA, Hunter FMI, Ten Hoopen P, Alako B, Amid C, Wilkinson DJ, Curtis TP, Cochrane G, Finn RD (2018) EBI metagenomics in 2017: enriching the analysis of microbial communities, from sequence reads to assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res 46:D726–DD35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]