Abstract

Objectives

We examined the effect of a telemedical coaching (TMC) programme accompanied with or without telemonitoring on weight loss in an occupational healthcare setting with a three-armed randomised controlled trial (NCT01837134 ’Pre-results').

Methods

Overweight employees (n=104, body mass index [BMI] ≥25 kg/m2) were invited by their medical corporate department and randomised into either a TMC group (n=34) or in one of the two control groups (C1, n=34; C2, n=36). TMC and C1 were equipped with telemonitoring devices (scales and pedometers) at baseline, and C2 after 6 months. Telemonitoring devices automatically transferred data into a personalised online portal. TMC was coached with weekly care calls in months 3–6 and monthly calls from months 7 to 12. C2 had a short coaching phase in months 6–9. C1 received no further support. After the 12-month intervention phase, participants could take advantage of further company health promotion offers. Follow-up data were determined after 12 months of intervention and per-protocol (PP) and intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses were performed. Weight change was followed up after 36 months. Estimated treatment difference (ETD) was calculated for weight reduction.

Results

ETD from TMC to C1 (−3.6 kg 95% CI −7.40 to −0.1, p=0.047) and to C2 (−4.2 kg [−7.90 to −0.5], p=0.026) was significantly different at the 12 months follow-up in the PP-analysis, but lost significance in the ITT analysis. All groups reduced weight after 12 months (−3.3 to −8.4 kg [5.5–10.3 kg], all p<0.01) and sustained it during the 36 months follow-up (−4.8 to −7.8 kg [5.6–12.8 kg], all p<0.01). ETD analyses revealed no difference between all groups neither in the PP nor in the ITT analysis at the 3 years follow-up. All groups reduced BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure and improved eating behaviour in the PP or ITT analyses.

Conclusions

TMC and/or telemonitoring support long-term weight reduction in overweight employees. The combination of both interventions points towards an additional effect.

Trial registration number

Keywords: telemedicine, preventive medicine, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Study investigates the effect of telemonitoring and telemedical coaching in a randomised controlled trial.

Study focuses on a working population cohort of one company over 3 years.

Body weight and telemetric data were recorded over 3 years.

Besides body weight reduction, anthropometric, laboratory and behavioural parameters were measured at baseline and after 12 months of intervention.

Data concerning education level, income, race and occupation type had not been collected due to legal regulations.

Introduction

Positive energy balance and reduced physical activity are main reasons for weight gain.1 Overweight not only increases the risk for several cardiometabolic diseases such as type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease,1 it is also associated with sick leave days as well as direct and indirect disease costs.2 Therefore, a weight reduction of 5%–7% is generally recommended for overweight people to prevent the development of type 2 diabetes.3–5 An analysis of the German socio-economic panel data estimated additional costs of €2.5–5.4 billion due to overweight-related and obesity-related sick leave days.2 In light of this background, companies should have an essential interest in effective healthcare programmes for weight management of their employees. Several worksite behavioural lifestyle interventions have shown to be feasible and effective in improving risk factors such as overweight or increased HbA1c values.6 7 However, occupational health settings have not been extensively investigated.7 8 In this context, telemedical and technology-based lifestyle interventions comprise several advantages over traditional clinical settings such as convenience, costs, and the ability to tailor plans and feedback to a participant’s individual needs. However, telemedical lifestyle interventions are facing certain problems such as absence of face-to-face interaction and technological dependencies.9 Furthermore, the present scientific discussion concerns the added value of telemedical coaching (TMC, self-monitoring of weight as well as physical activity plus continuous care calls) on pure telemonitoring (self-monitoring of weight and physical activity).10 11 In a previously published study, it has been shown that additional continuous human support via face-to-face or telephone interviews during a lifestyle intervention is essential and more effective in reducing weight than without human encouragement.12 A continuous human-based health coaching not only offers participants an additional contact person for questions regarding a healthy diet (ie, low-carb diet for weight reduction), physical activity or medical issues, but also supports and motivates participants to focus on their goals.13 However, there is still the question whether there is a combined effect of TMC and telemonitoring in an occupational healthcare setting in long-term effects on weight control compared with telemonitoring alone. To examine this issue, we performed a three-armed randomised controlled trial with a cohort of overweight employees who self-monitored their weight and physical activity over 3 years. In this cohort we examined the effect of long-term TMC on weight loss in comparison to short-term TMC or telemonitoring alone.

Materials and methods

Study population

Overweight employees of the company Boehringer Ingelheim (BI) were invited by their medical corporate department at the location Ingelheim, Rhineland-Palatinate, for a voluntary participation in the study. All participants received no compensation for their study participation. Details of the open-label BI employee cohort have been described previously.14 15 Inclusion criteria for the present study were a (1) BMI ≥25 kg/m2 and/or a (2) waist circumference >94 cm in men or >80 cm in women. Exclusion criteria comprised: (1) severe illness with inpatient treatment during the last 3 months, (2) weight reduction >2 kg/week during the last month, (3) smoking cessation during the last 3 months, (4) medication for active weight reduction, (5) pregnancy and breastfeeding. The first participant was enrolled on 18 May 2013 and the last participant finished the 36 months follow-up on 01 June2016.

Randomisation and masking

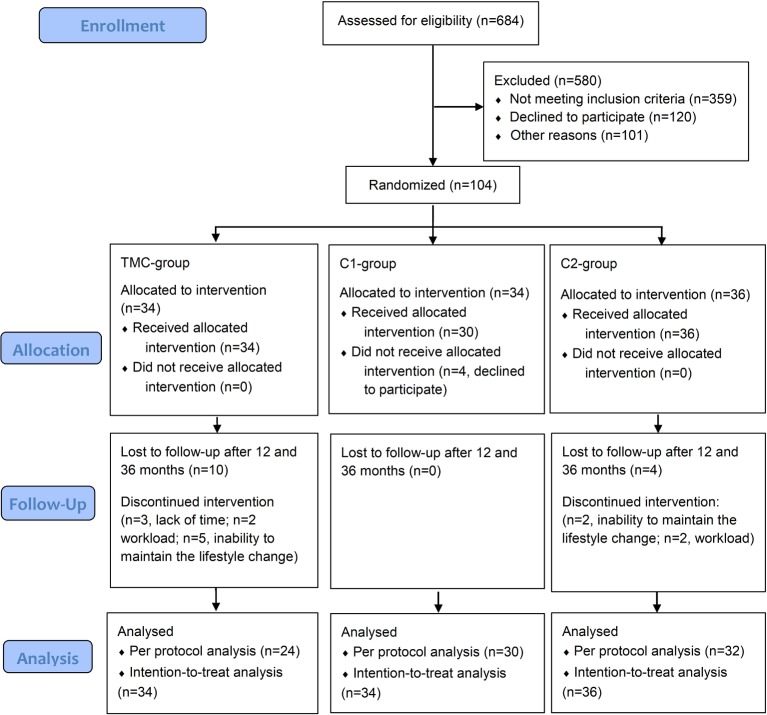

Participants (n=104) were randomised with a 1:1:1 ratio into three parallel groups (TMC-group, n=34; first control group [C1], n=34; second control group [C2], n=36) using an electronically generated random list (SAS PROC SURVEYSELECT) as shown in figure 1. In detail, each participant was assigned a serial study identification (ID) number. For each ID number, there was a closed envelope with the group assignment. The allocation sequence was concealed from the participants, the study physician, and the outcome assessor. The data analyst was blinded after assignment to the interventions.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram. TMC, telemedical coaching.

Study design

Employees of BI were invited by their medical corporate department for the determination of anthropometric, clinical and behavioural data. The parameters age, sex, weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, pulse, triglycerides, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, haemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), fasting blood glucose (FBG), adiponectin and C reactive protein (CRP), eating behaviour, physical activity and quality of life were determined at baseline and after 12 months of intervention. Additionally, body weight was measured after 3, 6, 9, 12 and 36 months. Blood pressure and pulse were measured after a 5 min rest in a sitting position on both arms. Venous blood was collected by inserting an intravenous cannula into the forearm vein and laboratory parameters were analysed at the local laboratory of BI as described elsewhere.15 Validated self-reporting questionnaires were used to assess quality of life (Short Form [SF] 12 Questionnaire),16 physical activity17 and eating behaviour (German version of the ’Three-factor Eating Questionnaire' [TFEQ]).18

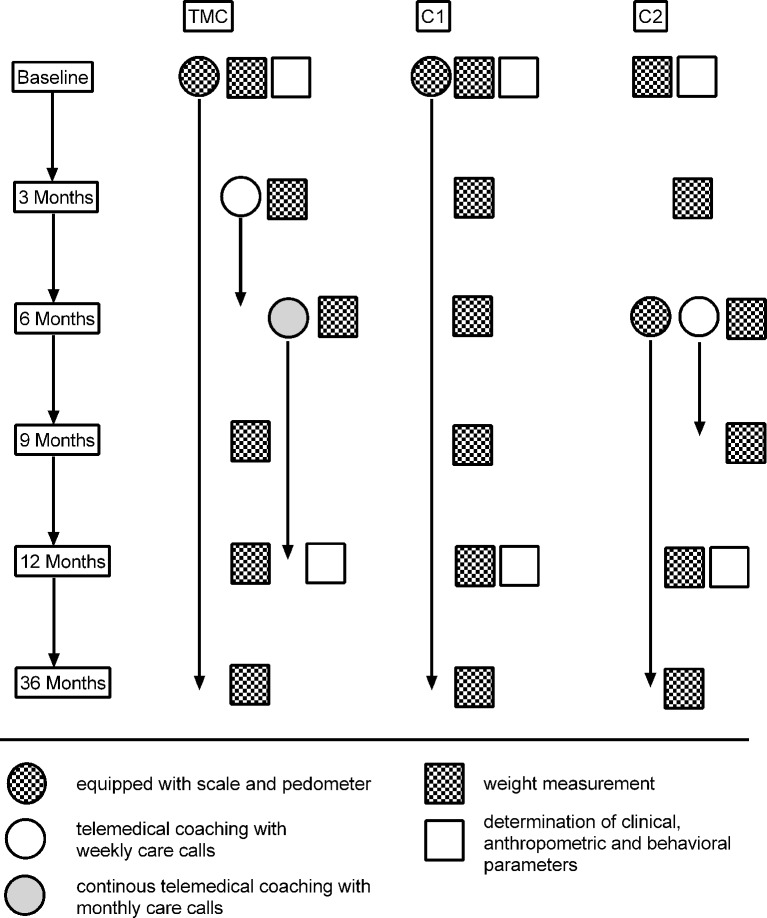

Participants of the TMC-group were equipped with telemonitoring devices (scale and pedometer; Fitbit, Boston, Massachusetts, USA) at baseline, and were coached with weekly care calls in months 3–6 and after that with monthly calls from months 7 to 12. Volunteers of the C1-group were also equipped with scales and pedometers at baseline but received no further support during the study phase. TMC and C1-group were instructed to monitor their body weight and physical activity (step counter) during the whole 12 months intervention phase (figure 2). The C2-group had only a short-term coaching phase in months 6–9 and was also equipped with pedometers and scales at the 6. month. C2-group participants were also instructed to monitor their body weight and physical activity. The telemonitoring devices automatically transferred recorded data into a personalised online portal, which could be monitored from the participants and the coaches in the study centre (West-German Centre of Diabetes and Health, Düsseldorf Catholic Hospital Group, Düsseldorf, Germany). Following the 12-month intervention phase, participants were offered further company health promotion offers like seminars for a healthy lifestyle (topics: smoking cessation, healthy eating or physical activity), as described in detail elsewhere.14 15 The coaching was performed by diabetes nurses trained in mental and motivational coaching who used a standard protocol for each call (online supplementary material). Each coaching should last for 30 min and results were discussed with the responsible study physician. The TMC contained a ’medical mental motivation programme' which was previously described19 20 and included information about healthy diet, physical activity, subjective possibilities for lifestyle change, data discussion and target agreements. The aim was to achieve at least a 5% weight reduction within 12 months. The present study was designed to identify whether TMC with or without telemonitoring devices can contribute to a reduction in body weight and whether one of those alone or the combination of both is more effective in reducing weight.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for the design of the study. At baseline, the TMC-group and C1-group were equipped with telemonitoring devices (scales and pedometers), and the C2-group 6 months later as well. TMC-group was coached with weekly care calls in months 3–6 and monthly calls from month 7 to 12. C2-group had only a short coaching phase with care calls in months 6–9. TMC, telemedical coaching.

bmjopen-2018-022242supp001.pdf (50.5KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient involvement regarding the research question, the outcome measures, the design, the recruitment and the conduction of the study as well as for the assessment of the burden of the intervention. The participants of the study will not be provided with the results of the study.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint of the study was the difference in body weight reduction after 12 months of intervention between all of the groups. Secondary endpoints comprised (1) the difference of weight loss after 6 months in order to analyse the effect of TMC with or without telemonitoring devices versus no treatment (TMC vs C1 and TMC vs C2) and (2) the long-term weight reducing effect of all intervention arms over 3 years. Tertiary endpoints comprised changes in BMI, waist circumference, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, triglycerides, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HbA1c, FBG, adiponectin, CRP, eating behaviour, physical activity and quality of life after 12 months of follow-up.

Statistical analysis

Our sample size has been calculated (software: G*Power V.3.1) assuming that TMC leads to reduction of 3.7 kg (2.5 SD) in body weight in the TMC group. For the C1 group as well as the C2 group reductions of 1.6 kg (2.5) and 2.4 kg (2.5) were estimated. With a power of 80%, a significance level of 5%, and a dropout rate of 25% at least 35 datasets per group were calculated, that is, a total of 105 persons. Per-protocol (PP) analyses as well as intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses were performed. Missing values were substituted by the ‘last-observation-carried-forward’ (LOCF) principle. Shown are means with SD (mean [SD]) or means with 95% CI (mean [95% CI]) as well as percentages, as appropriate. ETD was analysed to determine differences in weight reduction between TMC and the control groups and ETD was adjusted to baseline values. Dichotomous variables were analysed by using the χ2 test. Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test was used to calculate within-group differences between time points. Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons correction was applied for group comparisons. Level of significance was set at α=0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism V.6.04 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California, USA) and SAS statistical package V.9.3.

Results

Study population

One hundred and four volunteers were included into the study and randomly assigned into three groups. After beginning of the study, four participants decided not to take part anymore and n=14 dropped out during the first 3 months. Reasons for dropout were workload (n=4), lack of time (n=3) and inability to maintain the lifestyle change (n=7). However, all dropouts came to the study visits at the 36 months follow-up as a part of their general health check-ups. All volunteers (n=104) were used for ITT analyses, additionally, we performed also PP analyses with those participants who completed the 12-month intervention. Fourteen per cent of the data were missing and replaced by the LOCF approach. No side effects or harms were reported. Baseline data did not differ between all of the three groups (table 1). However, there was a difference in age between the TMC-group and the C2-group in regard to the dropouts as shown in the online supplementary table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| TMC group (n=34) | Control group C1 (n=30) | Control group C2 (n=36) | |

| Anthropometrics | |||

| Sex (n) (male/female in %) | 29 (85)/5 (15) | 25 (84)/5 (16) | 30 (83)/6 (17) |

| Age (years) | 51 (6) | 48 (5) | 51 (5) |

| Weight (kg) | 100 (18) | 98 (15) | 97 (18) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 32 (7) | 30 (4) | 31 (4) |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 107 (13) | 103 (10) | 105 (13) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 139 (14) | 146 (14) | 145 (16) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | 90 (10) | 89 (12) | 89 (8) |

| Laboratory parameters | |||

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 154 (85) | 178 (102) | 176 (94) |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 209 (35) | 206 (30) | 203 (34) |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 49 (11) | 46 (14) | 49 (13) |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dL) | 141 (33) | 137 (29) | 134 (34) |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.7 (0.4) | 5.6 (0.3) | 5.9 (0.6) |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | 100 (16) | 97 (24) | 100 (30) |

| Adiponectin (µg/mL) | 5.9 (3.5) | 5.6 (5.8) | 5.5 (4.4) |

| C reactive protein (mg/dL) | 2.5 (3.9) | 2.5 (2.4) | 2.1 (1.3) |

| Eating behaviour | |||

| TFEQ—Cognitive control (au) | 8.4 (3.5) | 7.7 (3.2) | 9.0 (3.8) |

| TFEQ—Suggestibility (au) | 6.4 (3.3) | 5.3 (2.5) | 5.6 (2.7) |

| TFEQ—Hunger (au) | 4.8 (3.1) | 4.0 (2.6) | 4.0 (2.5) |

| Quality of life | |||

| SF12—Physical health (au) | 50 (10) | 51 (8) | 52 (7) |

| SF12—Mental health (au) | 37 (6) | 37 (6) | 37 (5) |

| Physical activity | |||

| FFkA—Sports per week (h) | 1.2 (1.5) | 1.2 (1.6) | 2.4 (2.7) |

| FFkA—Physically active per week (h) | 7.8 (7.6) | 7.8 (5.8) | 8.8 (7.0) |

Data are shown as mean (SD) or %; baseline data were compared between groups by using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test.

There no differences between groups at baseline.

FFkA, Freiburger Questionnaire for physical activity; HbA1c, haemoglobin A1c; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; SF12, Short Form 12 Questionnaire; TFEQ, Three-factor Eating Questionnaire; TMC, telemedical coaching.

Weight difference after 12 months of intervention between groups (primary endpoint)

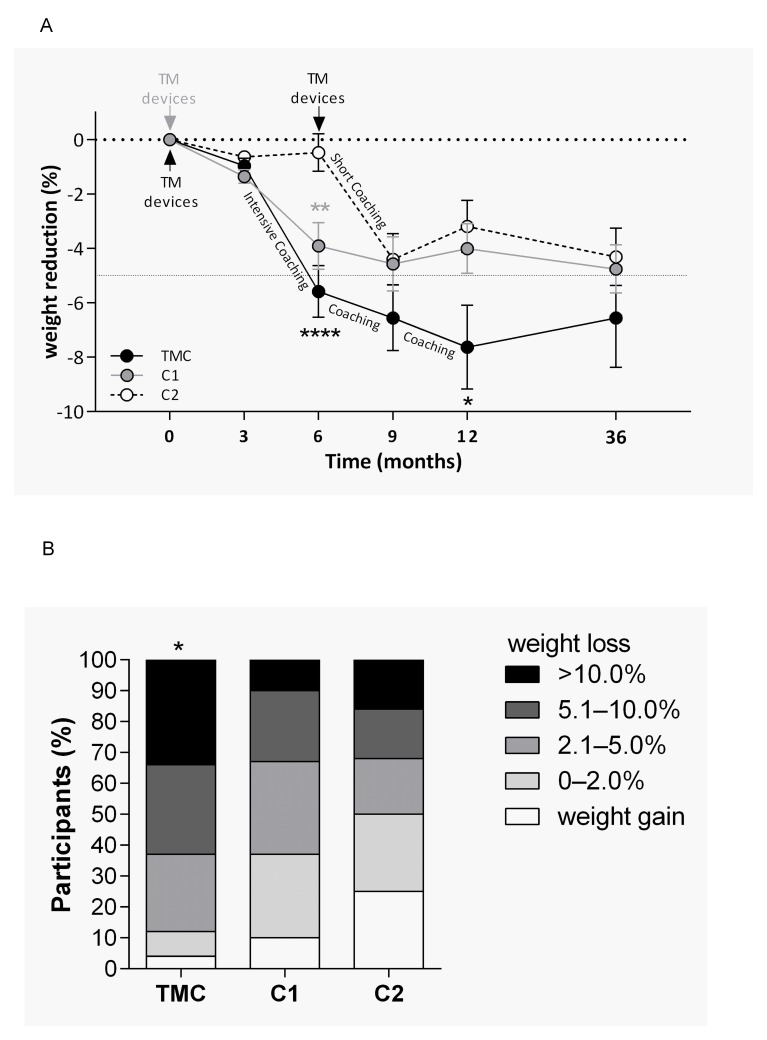

Calculation of ETD for TMC to C1 revealed a significant difference of −3.6 kg (−7.4; −0.1) (p=0.047) after 12 months of intervention in favour of TMC in the PP analysis (figure 3A). This significance was lost after performing an ITT analyses. Furthermore, there was also a significant difference from TMC to C2 with −4.2 kg (−7.9; −0.5) (p=0.026) at the 12 months follow-up in the PP analysis. However, this difference was also lost after performing ITT analysis. In addition, significantly more participants of the TMC-group (63%; n=15; p=0.037) achieved a weight loss of at least 5% during the 12 months of intervention compared with the control groups (33% (n=10) of C1 and 31% [n=10] of C2; figure 3B) in the PP analysis.

Figure 3.

Reduction of body weight. (A) Differences in weight changes between groups were analysed using χ2 test (*p<0.05). (B) Differences of weight loss between all groups were analysed using Kruskal-Wallis test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ****p<0.0001). TM, telemedical; TMC, telemedical coaching.

Changes of weight until the 36 months follow-up (secondary endpoints)

Weight reduction was already significant after 6 months of intervention in those both groups, which had been equipped with telemonitoring devices at baseline (TMC and C1; table 2) (PP analysis). C2-group could not significantly reduce weight. The ETD after 6 months from the TMC-group to C1-group was −2.0 kg (−4.7; 0.7) (p=0.142) and to the C2-group −5.3 kg (−8.0; −2.8) (p<0.001). This result was still significant in the ITT analysis (TMC vs C1: −0.5 kg [−2.9; 1.9] [p=0.675]; TMC vs C2: −3.9 [−6.1;

Table 2.

Course of weight reduction during the intervention

|

Time (months) Weight loss in kg |

3 | 6 | 9 | 12 | 36 |

| TMC group | |||||

| Per protocol (n=24) | −1.0 (−1.6; −0.5) | −6.1 (−8.1; −4.1) | −7.2 (−9.8; −4.6) | −8.4 (−11.3; −5.4) | −7.8 (−11.3; −4.3) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −8.4 (-11.3; −5.4) | <0.001 |

| Intention-to-treat (n=34) | −0.8 (−1.3; −0.4) | −4.4 (−6.1; −2.8) | −5.1 (−7.2; −2.9) | −5.8 (−8.3; −3.3) | −5.7 (−8.6; −2.9) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Control group C1 | |||||

| Per protocol (n=30) | −1.3 (−1.8; −0.8) | −3.8 (−5.6; −2.0) | −4.5 (−6.9; −2.2) | −4.0 (−6.6; −1.8) | −4.9 (−8.1; −1.8) |

| P value | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.003 | 0.003 |

| Intention-to-treat (n=34) | −0.7 (−1.5; −0.2) | −3.7 (−5.4; 2.2) | −4.5 (−6.8; −2.9) | −4.0 (−6.7; −1.3) | −4.9 (−7.9; −1.9) |

| P value | 0.002 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.004 | 0.002 |

| Control group C2 | |||||

| Per protocol (n=32) | −0.6 (−1.1; −0.2) | −0.4 (−2.2; 1.3) | −4.5 (−6.7; −2.2) | −3.3 (−5.8; −0.8) | −4.8 (−7.9; −1.8) |

| P value | 0.010 | 0.619 | <0.001 | 0.012 | 0.002 |

| Intention-to-treat (n=36) | −0.6 (−1.0; −0.1) | −0.4 (−2.0; 1.2) | −4.0 (−6.1; −1.8) | −2.5 (−4.9; −0.1) | −4.2 (−7.0; −1.5) |

| P value | 0.010 | 0.607 | < 0.001 | 0.044 | 0.003 |

Differences at different time points compared with baseline are shown as mean (95% CI). Differences in weight loss within groups were compared with baseline and were analysed by using Friedman test with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. The overall frequency of missing data was 3%, 13%, 9%, 17% and 0% at the 3, 6, 9, 12 and 36-months follow-up.

TMC, telemedical coaching.

−1.4] [p=0.001]). Weight loss achieved after 12 months of intervention could be maintained until the 36 months follow-up in all of the groups. In detail, all three groups significantly reduced weight (TMC: −8.4 [−11.3; −5.4] kg; C1: −4.0 [−6.6; −1.8] kg; C2: −3.3 [−5.8; −0.8] kg). ETD analyses revealed no difference between all the groups neither in the PP nor in the ITT analysis at the 3 years follow-up.

Changes in clinical and behavioural parameters after 12 months of intervention (tertiary endpoints)

All groups significantly reduced BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure and achieved improvements in aspects of eating behaviour as determined by PP and ITT analyses (online supplementary table 2). Changes in the remaining parameters did not reach statistical significance neither in PP nor in ITT analyses.

bmjopen-2018-022242supp002.pdf (143.6KB, pdf)

Discussion

In the present study overweight employees of the company BI, equipped with telemonitoring devices (scale and pedometer) and/or supported by mental coaches, demonstrated large reductions of body weight after 12 months of lifestyle intervention. In this three-armed randomised controlled trial, we could show that TMC and/or permanent telemonitoring lead to long-term reductions in body weight, even after 2 years of follow-up. These weight changes were not significantly different in the ITT analysis between the groups. However, the results of the PP analysis point towards a possible treatment superiority of the TMC-group regarding a long-term weight reduction. Other studies with different populations have also shown that TMC or telemonitoring can contribute to meaningful reductions of body weight of more than 5%.21 22 In particular, monitoring of physical activity (measured by accelerometers), weight (daily recording of weight) and daily calorie intake seems to be crucial for weight management programmes, which is in line with our results.23

In the present study, TMC with telemonitoring compared with telemonitoring alone led to no significant difference in weight reduction at the 6 months follow-up. However, the within-group analysis with the PP approach revealed a larger reduction in body weight for the intervention with the combination of TMC and telemonitoring. There could be several reasons for the non-significance in the between-group analysis at the 6 months follow-up. One reason could be that the circumstance of being observed and treated by its own company have led to an increased short-term healthy behaviour. Therefore, this subtle effect was lost after the 9 months or 12 months follow-up. On the other hand, with respect to the 12 months follow-up, long-term coaching/support seems to be more important and crucial than short-term coaching.24 This fact is also supported by the significant difference in the ETD analysis with the PP approach between the TMC-group with long-term coaching in comparison to the C2-group with short-term coaching. There were significant differences in weight reduction at the 9 or 12 months follow-up. However, these differences should be interpreted with caution as the ITT analysis revealed no statistical difference between both groups.

Another study examined the effects of in-person support (face-to-face) in comparison to TMC during a weight-loss intervention programme.22 Both lifestyle intervention approaches achieved a clinically relevant weight loss over a period of 24 months in obese patients. These results confirm our findings regarding the efficacy of TMC and underpin the potential of personal remote support. Therefore, TMC offers an effective solution for weight management support in the primary care, even without face-to-face contact,22 as it was shown in our study as well.

The increasing prevalence of type 2 diabetes, which is accompanied with an increase in pharmaceutical costs, represents a concerning burden for national healthcare systems.25 Accordingly, there is a strong need for alternative and cost-effective lifestyle-based approaches. The participants of the BI cohort had an HbA1c near to or in the pre-diabetic range and were obese (BMI >30) as well. A weight reduction of 5%–7% is generally recommended for these people based on the success of lifestyle interventions to prevent the development of type 2 diabetes.3–5 In the present study, particularly, the TMC group achieved this target, even after 2 years of follow-up (−6.6% weight reduction).

A web-based weight management programme demonstrated that particularly the combination of automated web-based monitoring and basic nurse support can provide an effective solution for weight management. In this study, it has been shown that additional human support is essential and more effective in reducing weight than without human encouragement. This relationship elucidates the necessity of external experts and coaching in telemedical interventions.12 However, it has been shown that telephone calls alone, without TMC and monitoring, are not enough to sustainably influence behaviour and reduce weight.10 11

Besides the reduction of body weight in all of the three groups, there were further relevant improvements in cardiovascular risk factors such as BMI and blood pressure. Moreover, TMC led to significant improvements in different aspects of eating behaviour. In line with other studies with similar circumstances (web-based, app-based or SMS-based lifestyle interventions), external motivation, electronical reminders or personalised coaching can contribute to clinically relevant effects in cardiovascular risk factors.22

The present study, as part of the prevention and healthcare programme of BI,15 was well tolerated. The overall dropout rate during the 12-month intervention was 14%, and no adverse events were reported. This low rate was also reported in patients with heart diseases during their cardiac rehabilitation (<10%) which was characterised by using telemedical devices (pedometers) and telephone coaching.26 Possible explanations for this low dropout rate could be the flexible and simple contact with health experts as well as the motivational support for lifestyle changes. Another explanation could be an enhanced compliance due to the subtle feeling of being observed.

The present study has certain strengths and limitations. One limitation is the high dropout rate in the TMC-group of 29% (10/34). In contrast, short-term coaching (C2-group) or no coaching (C1) led to only little dropout rates of 11% or 0% in the control groups (C2-group: 4/36; C1-group: 0/30). This imbalance between the groups regarding the dropout rate could have affected the results as maybe only highly motivated participants remained in the TMC-group. Reasons for dropout were workload, lack of time and inability to stand the lifestyle change. However, the overall dropout rate of all three intervention groups was low (14%) and in line with other studies with comparable study durations.26 27 A possible explanation could be that the overweight employees had been invited by their medical corporate department for participation in this study. Therefore, there is the possibility for a selection bias if only motivated employees volunteered. However, the randomisation procedure into one of the three parallel groups should have abolished any potential effect at the beginning of the study, particularly, because baseline characteristics of the three groups were not different. According to the study size with 104 participants, the results of the present study might not be generalisable or transferable to other non-occupational cohorts. However, the study of Luley et al demonstrated comparable dropout rates of 9%–12% during a 1-year lifestyle telemonitoring and coaching programme for weight loss in obese patients with metabolic syndrome in a non-occupational setting.23 Furthermore, the influencing factor age should be considered when discussing the results of the TMC programme. In the present study, a middle-aged employee cohort took part at the intervention study. To investigate the impact of the factor age on the weight reducing effect of TMC, linear regression analyses were performed and showed no effect of age on the primary outcome (data not shown). Especially older people could have problems with this modern healthcare approach,28 but a recently published work by us demonstrated that even older persons (59±9 years) can benefit from a telemedical programme.13

Statistical adjustments to socioeconomic status, previous obesity treatment programmes or ethnicity were not performed since data concerning education level, income, race and occupation type had not been collected due to legal regulations. Therefore, there is the possibility that differences in outcomes between treatment groups may be due to participants’ unknown characteristics rather than to differences in the intervention.

Furthermore, missing values might have led to some reporting bias, but the conservative LOCF approach for imputation of missing data was applied. This LOCF procedure is a conservative method to estimate treatment effects of an intervention. Therefore, our results might have been underestimated by this approach, which should be considered when interpreting the data of the ITT analyses. Another limitation is that there was the possibility following the 12-month intervention phase for the study participants to take advantage of further company health promotion offers. This could have affected the results of the within-group analysis as it might have led to an additional intervention effect.

The strengths of our study comprise that we (1) focused on a working population cohort of one company over 3 years, (2) that we performed a randomised and controlled trial with different combinations of TMC and monitoring, as well as (3) that we conducted a comprehensive metabolic characterisation.

The present study shows that personal remote support by TMC and/or telemonitoring can significantly support body weight reduction in overweight employees in an occupational health setting. This weight reduction could be maintained over 3 years. Although not supported by the ITT analysis, the PP analysis points towards a possible treatment superiority of TMC in combination with telemonitoring compared with coaching or telemonitoring alone. To confirm the tendency of our results, future studies need to be performed with larger sample sizes and should be controlled for different influences as described in the limitations. However, accompanied improvements in blood pressure, anthropometric parameters and aspects of eating behaviour indicate that TMC, especially in combination with telemonitoring, could be a promising tool for other companies to increase health, prevent weight gain and improve company affiliation of their employees.

bmjopen-2018-022242supp003.pdf (121.2KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: KK, MS and SM are responsible for the conception and design of the study. MS collected data. KK, MR and SM analyzed and interpreted data. KK and MR drafted the manuscript. KK, MR, MS and SM approved the final version of the manuscript. KK and SM are the guarantors of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Funding: The study was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH and by Gesellschaft von Freunden und Förderern der Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf e.V.

Competing interests: KK and SM received research support from Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH & Co. KG. MS is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG. SM is a member of the Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma GmbH & Co. KG advisory board. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article are existent. The funders had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the manuscript.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Knowler WC, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, et al. 10-year follow-up of diabetes incidence and weight loss in the diabetes prevention program outcomes study. Lancet 2009;374:1677–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61457-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lehnert T, Stuhldreher N, Streltchenia P, et al. Sick leave days and costs associated with overweight and obesity in Germany. J Occup Environ Med 2014;56:20–7. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. American Diabetes Association. Executive summary: Standards of medical care in diabetes--2014. Diabetes Care 2014;37 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S5–13. 10.2337/dc14-S005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Long-term effects of lifestyle intervention or metformin on diabetes development and microvascular complications over 15-year follow-up: the Diabetes Prevention Program Outcomes Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2015;3:866–75. 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00291-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lindström J, Peltonen M, Eriksson JG, et al. Improved lifestyle and decreased diabetes risk over 13 years: long-term follow-up of the randomised Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study (DPS). Diabetologia 2013;56:284–93. 10.1007/s00125-012-2752-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kramer MK, Molenaar DM, Arena VC, et al. Improving employee health: evaluation of a worksite lifestyle change program to decrease risk factors for diabetes and cardiovascular disease. J Occup Environ Med 2015;57:284–91. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dallam GM, Foust CP. A comparative approach to using the diabetes prevention program to reduce diabetes risk in a worksite setting. Health Promot Pract 2013;14:199–204. 10.1177/1524839912437786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Giese KK, Cook PF. Reducing obesity among employees of a manufacturing plant: translating the Diabetes Prevention Program to the workplace. Workplace Health Saf 2014;62:136–41. 10.1177/216507991406200402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Webb VL, Wadden TA. Intensive Lifestyle Intervention for Obesity: Principles, Practices, and Results. Gastroenterology 2017;152:1752–64. 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.01.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. O’Connor PJ, Schmittdiel JA, Pathak RD, et al. Randomized trial of telephone outreach to improve medication adherence and metabolic control in adults with diabetes. Diabetes Care 2014;37:3317–24. 10.2337/dc14-0596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stuart KL, Wyld B, Bastiaans K, et al. A telephone-supported cardiovascular lifestyle programme (CLIP) for lipid reduction and weight loss in general practice patients: a randomised controlled pilot trial. Public Health Nutr 2014;17:640–7. 10.1017/S1368980013000220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yardley L, Ware LJ, Smith ER, et al. Randomised controlled feasibility trial of a web-based weight management intervention with nurse support for obese patients in primary care. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014;11:67 10.1186/1479-5868-11-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kempf K, Altpeter B, Berger J, et al. A Randomized Controlled Trial. Diabetes Care 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kempf K, Martin S, Döhring C, et al. The Boehringer Ingelheim employee study (Part 2): 10-year cardiovascular diseases risk estimation. Occup Med 2016;66:543–50. 10.1093/occmed/kqw084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kempf K, Martin S, Döhring C, et al. The epidemiological Boehringer Ingelheim Employee study--part I: impact of overweight and obesity on cardiometabolic risk. J Obes 2013;2013:1–10. 10.1155/2013/159123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gandek B, Ware JE, Aaronson NK, et al. Cross-validation of item selection and scoring for the SF-12 Health Survey in nine countries: results from the IQOLA Project. International Quality of Life Assessment. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1171–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Eckert K. Impact of physical activity and bodyweight on health-related quality of life in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Syndr Obes 2012;5:303–11. 10.2147/DMSO.S34835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Stunkard AJ, Messick S. The three-factor eating questionnaire to measure dietary restraint, disinhibition and hunger. J Psychosom Res 1985;29:71–83. 10.1016/0022-3999(85)90010-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kempf K, Dirk M, Kolb H, et al. [The Da Vinci Medical-mental motivation program for supporting lifestyle changes in patients with type 2 diabetes]. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 2012;137:362–7. 10.1055/s-0031-1298888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Martin S, Kempf K, Dirk M, et al. Kognitive Verhaltenstherapie bei Typ-2-Diabetes: Ergebnisse einer Pilotstudie mit dem strukturierten Programm Da Vinci Diabetes®. Diabetologie und Stoffwechsel 2009;4:370–3. 10.1055/s-0029-1224686 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Temmingh H, Claassen A, van Zyl S, et al. The evaluation of a telephonic wellness coaching intervention for weight reduction and wellness improvement in a community-based cohort of persons with serious mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis 2013;201:977–86. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Appel LJ, Clark JM, Yeh H-C, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of Weight-Loss Interventions in Clinical Practice. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2011;365:1959–68. 10.1056/NEJMoa1108660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Luley C, Blaik A, Götz A, et al. Weight loss by telemonitoring of nutrition and physical activity in patients with metabolic syndrome for 1 year. J Am Coll Nutr 2014;33:363–74. 10.1080/07315724.2013.875437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Venditti EM, Wylie-Rosett J, Delahanty LM, et al. Short and long-term lifestyle coaching approaches used to address diverse participant barriers to weight loss and physical activity adherence. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2014;11:16 10.1186/1479-5868-11-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. American Diabetes Association. Economic costs of diabetes in the U.S. in 2012. Diabetes Care 2013;36:1033–46. 10.2337/dc12-2625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sangster J, Furber S, Allman-Farinelli M, et al. Effectiveness of a pedometer-based telephone coaching program on weight and physical activity for people referred to a cardiac rehabilitation program: a randomized controlled trial. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2015;35:124–9. 10.1097/HCR.0000000000000082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Michaelides A, Raby C, Wood M, et al. Weight loss efficacy of a novel mobile Diabetes Prevention Program delivery platform with human coaching. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2016;4:e000264 10.1136/bmjdrc-2016-000264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Terschüren C, Mensing M, Mekel OC. Is telemonitoring an option against shortage of physicians in rural regions? Attitude towards telemedical devices in the North Rhine-Westphalian health survey, Germany. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:95 10.1186/1472-6963-12-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022242supp001.pdf (50.5KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022242supp002.pdf (143.6KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-022242supp003.pdf (121.2KB, pdf)