Abstract

Objective

This study was aimed to evaluate epidemiological and clinical relationship between Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MP) infection and childhood recurrent wheezing episode (RWE).

Design

Retrospective case note review.

Setting

Paediatric department at a single Korean institution.

Participants

Consecutive admitted patients with MP pneumonia and RWE (0–15 years of age) between 2003 and 2014.

Methods

The retrospective medical records of patients with (MP) pneumonia (n=793 for epidemiological analysis and n=501 for clinical analysis) and those with RWE (n=384) from 2003 to 2014 were analysed. Diagnosis of MP pneumonia was made based on two-times titration of IgM antibody during hospitalisation. An RWE patient was defined as one with expiratory wheezing with at least one or more wheezing episodes based on medical records.

Results

During three MP pneumonia epidemics, there were no corresponding increases of patients with RWE in the epidemic years. In the 501 MP pneumonia patients, 52 (10.4%) had wheezing at presentation and 15 (3%) had RWE. The MP pneumonia patients with wheezing at presentation (n=52) were younger and were more likely to have an allergic disease history than those without wheezing (n=449). Among wheezing patients at presentation, 10 patients had previously RWE history. In a follow-up study, 13 patients (including 5 RWE) with initial wheezing and 25 patients (including 2 RWE) without wheezing had wheezy episodes after discharge. Among the total 501 patients, it was estimated that at least 31 MP pneumonia patients (6.2%) showed recurrent wheezing after initial MP infection.

Conclusions

A small part of children with MP pneumonia showed recurrent wheezing after MP pneumonia, and patients with RWE had a greater likelihood of experiencing wheezing when they had an initial MP infection. However, there were no increased admitted patients with RWE in MP pneumonia epidemic periods because of rarity of MP reinfection in children including patients with RWE or asthma.

Keywords: asthma, children, epidemiology, Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia, recurrent wheezing

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This may be the first long-term epidemiological study regarding relationship between Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MP) infection and recurrent wheezing episode (RWE).

Two-times examination of anti-MP IgM for diagnosis of MP pneumonia strengthened accuracy for patient selection.

We discussed unsolved issues regarding MP infection and childhood asthma.

There were limitations in this study in regard to the following: retrospective analysis, data collected from a single centre and patient selection under our definition of RWE (or childhood asthma).

Introduction

Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MP) is one of the major pathogens in respiratory tract infections in children and young adults, manifesting from asymptomatic infection to potential fatal pneumonia. MP pneumonia is an endemic disease in large communities, but it occurs in nationwide cyclic epidemics of 3–7-year intervals. Also, MP is associated with a wide spectrum of other organ-specific diseases including neurological, dermatological, hepatic, cardiac, musculoskeletal, haematological diseases and possibly bronchial asthma.1 2

Childhood asthma is a complex disease process that can be classified into heterogeneous clinical phenotypes.3 The diverse phenotypes of childhood asthma may be associated with host factors, including the developing immune and respiratory systems and individual genetic variations. Childhood asthma is also influenced by environmental factors such as socioeconomic and/or cultural differences across populations.3 4 Therefore, diagnosis of asthma in children, especially in children under 5 years of age, could not be defined definitely, and the phenotypes of childhood asthma, such as the prevalence of asthma and frequency of severe asthma, could differ among populations.5 6 It has been suggested that initiation of asthma and acute exacerbation of asthma are associated with a variety of respiratory pathogens, including respiratory syncytial viruses (RSVs), rhinoviruses and MP, although the exact reasons are still not fully understood.7–9 In addition, it has been suggested that chronic MP infection is related to persistent bronchial hyper-responsiveness, chronic inflammation and acute exacerbation in children and adults with asthma.10–13

In Korea, MP pneumonia epidemics have been observed every 3–4 years from the mid-1980s to present. We recently found that during 2003–2012, there were three nationwide MP pneumonia epidemics, all of which had similar epidemiological patterns including age distribution and seasonal pattern.14 In this study, we evaluated the epidemiological and clinical characteristics of patients with MP pneumonia and those with recurrent wheezing episode (RWE) admitted during the 2003–2014 period, and we compared the data in both diseases. Also, we discussed the relationship between MP infection and childhood asthma.

Methods

Study design and setting

This study was a retrospective study conducted at Department of Paediatrics, The Catholic University of Korea Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital, a secondary referral hospital performing primary care for patients with MP pneumonia or RWE.

Patients and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved in the study due to its retrospective nature.

Patients and data collection

We performed a retrospective analysis of medical records of patients with MP pneumonia or RWE who were admitted to our institution from January 2003 to December 2014. In this study, diagnosis of MP pneumonia was based on chest radiographic findings and two-times titration of IgM antibody (Serodia-Myco II, Fujirebio Inc., Tokyo, Japan; positive cut-off value ≥1:40) at presentation and before discharge. Briefly, diagnoses of MP pneumonia were made when patients showed seroconversion (negative to positive), fourfold or greater increase in IgM titres, or high titres of >1:640 in initial and follow-up examinations during the disease course. Patients who received the test once or those who did not increase or decreased titres were excluded when initial titres were <1:320.14 15

The subjects with RWE were collected through the diagnostic code number J459 (asthma, asthma nature, bronchial asthma and infantile asthma). However, we used the term RWE in this study, because majority of patients were under 5 years of age and some patients over 6 years of age did not perform confirmative study for asthma such as pulmonary function test. An RWE patient was defined as one with expiratory wheezing at admission with at least one or more wheezing episodes within 6 months before admission, regardless of patient’s age based on the medical records. Patients with first wheezing at admission for any respiratory tract infection, including MP pneumonia, were excluded from the RWE group. Readmitted patients with RWE in the same year or different year were included in this series (35 episodes). Clinical and laboratory parameters were evaluated and compared between the groups. After discharge, wheezing episodes were evaluated through the medical records in both patient groups who revisited the outpatient clinic or had readmission at least two or more times from the date of discharge to December 2014.

Statistical analysis

All calculations were performed with SPSS V.14.0 (SPSS Inc.). Comparisons between groups were performed using the Student’s t-test, χ2 test and Fisher’s exact test, and the data were expressed as mean±SD for continuous variables. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

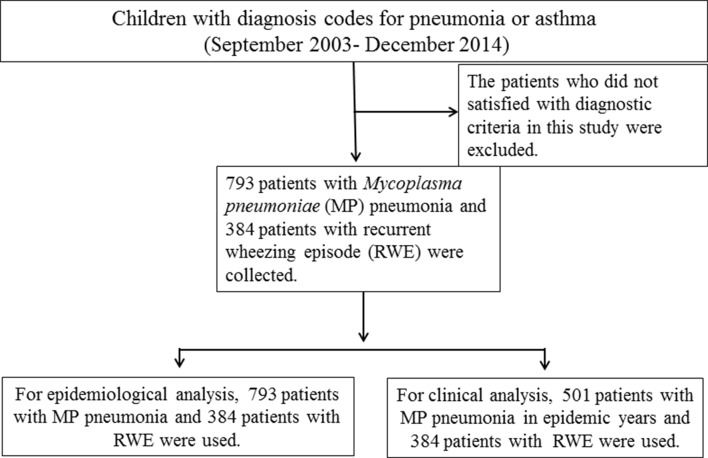

The subjects in the present study were 793 patients with MP pneumonia and 384 patients with RWE during the study period. For epidemiological comparison, a total 793 patients were used, as shown in previously published article.14 For clinical comparison between the groups, a total of 501 MP pneumonia patients that were admitted during the recent epidemics (241 cases in 2007–2006, and 260 cases in 2011), and 384 patients with RWE were analysed (figure 1). During the study period, the total number of admitted patients at our department was a total 25 911 (except nursery patients). There were approximately 2100 admitted patients per year with some variations in each year.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the patient selection in this study.

Most of MP pneumonia patients had follow-up period at least 3 years from last epidemic year of 2011, but the follow-up subjects satisfied with our selection criteria were 180 among 501 cases in the MP pneumonia group and 206 among 384 cases in the RWE group.

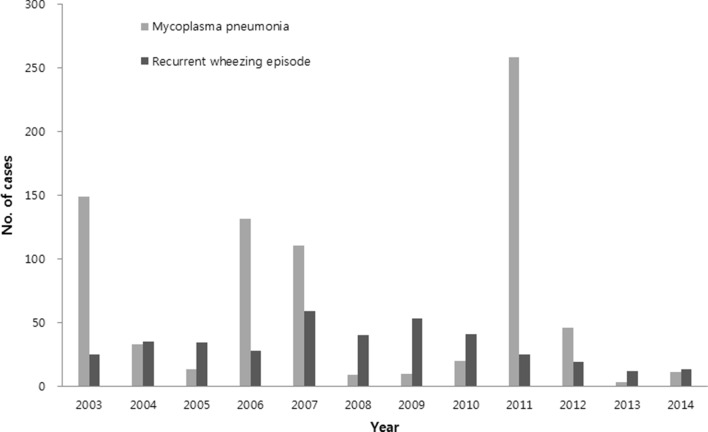

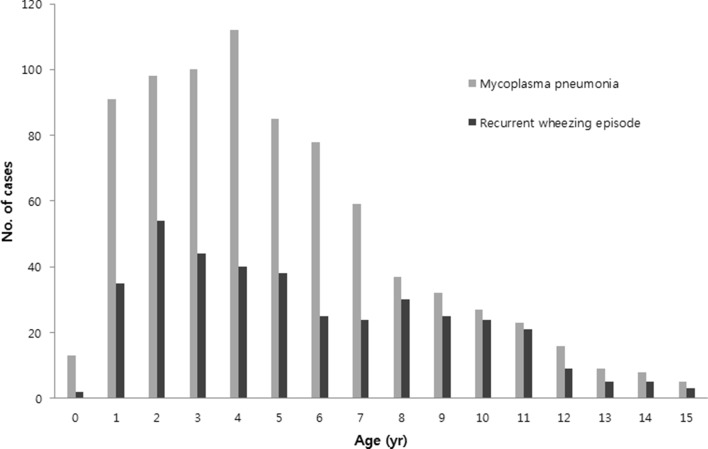

Epidemiological data of MP pneumonia and RWE from 2003 to 2014

In MP pneumonia patients, there were clear outbreaks of cases in 2003, 2006–2007 and 2011, with a few cases occurring in the interepidemic periods. There were relatively steady numbers of RWE cases every year during the study period. There were no corresponding increased cases in MP pneumonia epidemic years except in 2007 (figure 2). No MP pneumonia patient who was readmitted due to MP reinfection across the epidemics was observed during study period. The mean age and age distribution were similar, and the peak age groups were 2–5 years of age in both groups (figure 3). In seasonality of both groups, MP pneumonia was prevalent in decreasing order of autumn, summer, winter and spring, while patients with RWE were most prevalent in autumn, followed by spring, winter and summer (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Annual cases of MP pneumonia and recurrent wheezing episode during 2003–2014.

Figure 3.

Age distribution in MP pneumonia and recurrent wheezing episode groups.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of MP pneumonia and RWE groups

Demographic, clinical and laboratory data in both groups are shown in table 1. The mean age and age distribution were similar in both groups as shown in figure 3 (5.4 years vs 5.6 years, p=0.312). Both groups had male predominance, and there were more males in the RWE group. As expected, cases with wheezing at presentation, the proportion of patients with history or family history of allergic diseases, and history of wheezing were higher in the RWE group. Recurrent wheezing after discharge was observed in 38 of 180 patients with MP pneumonia and 141 of the 206 patients with RWE (p<0.001).

Table 1.

Clinical and laboratory findings of the patients with Mycoplasma pneumoniae (MP) pneumonia or recurrent wheezing episode (RWE)

| MP pneumonia (n=501) |

RWE (n=384) |

P value | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 5.4±3.4 | 5.6±3.5 | 0.31 |

| Male: female | 255/246 | 256/128 | <0.001 |

| Wheeze at presentation, n (%) | 52 (10.4) | 384 (100) | <0.001 |

| History of allergy*, n (%) | 72 (14.4) | 379 (98.7) | <0.001 |

| History of wheeze, n (%) | 15 (3.0) | 384 (100) | <0.001 |

| Family history of allergy, n (%) | 40 (8.0) | 134 (34.9) | <0.001 |

| Wheeze after discharge, n (%) | 38/180 (21.1) | 141/206 (68.4) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Leucocyte (x109/L) | 8800±4500 | 11100±4200 | <0.001 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 2.2±2.9 | 3.8±3.9 | <0.001 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 899±235 | 946±232 | <0.001 |

| IgE (IU/mL) | 267±391 | 617±673 | <0.001 |

*Number of patients who had history to be diagnosed as having asthma, allergic rhinitis and/or atopic dermatitis.

In MP pneumonia patients, 52 of the total 501 patients (10.4%) had wheezing at presentation, 72 (14.4%) had a history of allergic diseases, 15 (3%) had RWE according to our definition and 40 (8%) had a family history of allergic diseases. When we divided the MP pneumonia patients into two groups of patients with wheezing (n=52) and without wheezing (n=449), the patients with wheezing were younger (3.7 years vs 5.6 years, p<0.001) and had higher proportions of history allergic diseases and wheezing history and higher values of leucocyte count and eosinophil differential (table 2). Among the 52 MP pneumonia patients with wheezing at admission, 10 were patient with RWE, while 42 had no previous RWE history. Thus, in this study, 66% (10 of 15) of patients with RWE history presented with wheezing, while 8.6% of patients without RWE history (42 of 486) had wheezing at presentation. In a follow-up study of patients who visited two or more times after discharge, 13 (including 5 cases of RWE) of 21 MP pneumonia patients with initial wheezing and 25 (including 2 cases of RWE) of 159 MP pneumonia patients without wheezing had at least one wheezing episode after discharge (table 2). Although not all patients were followed-up, it was estimated that at least 31 of the total MP pneumonia patients (n=501, 6.2%) showed a recurrent wheezing after initial MP infection.

Table 2.

Clinical and laboratory findings of MP pneumonia patients with wheezing and without wheezing

| Wheezing (n=52) |

No wheezing (n=449) |

P value | |

| Clinical characteristics | |||

| Age (years) | 3.7±3.0 | 5.6±3.4 | <0.001 |

| Male: female | 32/20 | 223/226 | 0.11 |

| History of allergy*, n (%) | 16 (30.8) | 56 (12.5) | 0.01 |

| History of wheeze, n (%) | 10 (19.2) | 5 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Family history of allergy, n (%) | 8 (15.4) | 32 (7.1) | 0.05 |

| Wheeze after discharge, n (%) | 13/21 (61.9) | 25/159 (15.7) | <0.001 |

| Laboratory findings | |||

| Leucocyte (x109/L) | 10 400±5400 | 8700±4.3 | 0.03 |

| Eosinophil (%) | 3.0±3.2 | 2.1±2.9 | 0.08 |

| IgG | 873±219 | 903±238 | 0.43 |

| IgE | 407±609 | 249±350 | 0.11 |

*Number of patients who had history to be diagnosed as having asthma, allergic rhinitis and/or atopic dermatitis.

Discussion

In this study, we found that patients with MP pneumonia and patients with RWE had a similar mean age and age distribution during the past decade. However, the annual number of cases in the two groups was quite different; there were relatively stable number of annual cases in patients with RWE, without a corresponding increase in cases during or after MP pneumonia epidemic years. Although reinfection with MP reported to be not uncommon in other studies based on PCR or single serologic test-based studies,16 we found that there were no serologically confirmed reinfected MP pneumonia patients among 793 patients during study period, except a few readmitted patients with complications of initial MP infection in each epidemic. It suggests that reattack of MP pneumonia in children is extremely rare, and once infected children seem to have immunity to other MP strains in future epidemics including macrolide-resistant MP strains.14 During an MP epidemic, the majority of susceptible children are asymptomatic or have mild symptoms such as fever and sore throat, and only a small part of MP infected patients may affect pneumonia.1 2 Moreover, since MP reinfection is also rare in asthmatics of all age, our epidemiological data might not be associated with the situations where asthmatics have reasons for increase of admission such as exacerbation or initiation of RWE or asthma.

MP pneumonia patients in this study showed a similar prevalence of allergic diseases compared with data from previous nationwide questionnaire-based studies in Korea: 3% (15/501) and 14.4% (72/501) of MP pneumonia patients had a history of RWE (asthma) and a history of allergic diseases, respectively. Whereas 5.8% of school children aged 6–7 years had asthma history in 2000, and 13.5% of children reported a diagnosis of atopic dermatitis in 2008–2011 in Korea.17 18 In this study, among 52 MP pneumonia patients with initial wheezing, 10 were patients with RWE, while 42 had no previous wheezing history. Therefore, 66.6% (10 of 15) of patients with RWE, and 8.6% (42 of 486) of patients without RWE history were wheezing, and it suggests that patients with RWE or asthma with first-time MP infection might be prone to a wheezing episode as well as other respiratory virus infections as compounding factors of asthma exacerbation. Also, we found that after MP infection, at least 6% of MP pneumonia patients showed subsequent wheezing during at least over 3 years after initial MP infection. A large proportion of patients who experienced lower respiratory infections caused by RSV and rhinoviruses were reported to show recurrent wheezing after initial infection, especially when they were infected with other respiratory agents.19 20 A study reported that approximately 50% of children affected with severe RSV bronchiolitis had a subsequent asthma diagnosis.19 In Korea, since the majority of children might affect RSV during infancy and early childhood period as well as in other populations, it is possible that majority of MP infected patients experience RSV infection prior to MP infection. On the other hand, other authors reported that some patients with severe MP pneumonia had prolonged anatomical abnormalities, suggestive of small airway obstruction,21 and some patients had reduced pulmonary function after MP infection.8 Thus, patients with severe lung injury caused by any respiratory pathogens may be prone to recurrent wheezing and subsequent diagnosis of asthma.

We found that white blood cell count, eosinophil differential, IgG and IgE values were higher in the RWE group than those in the MP pneumonia group which had similar mean age. It could in part be explained that different activation of immune system of the host against the insults from RWE which induces chronic or repeated inflammation may be reflected in these laboratory findings.

Previous studies have reported that asthma patients are more likely to be infected or colonised with MP compared with healthy controls, and MP infection in chronic asthmatics might be associated with persistent bronchial hyper-responsiveness and exacerbation.10–13 MP pneumonia epidemics are cyclic in 3–4 year intervals, and the duration of an epidemic is generally limited to 1 year or occasionally 2 years, and during the interepidemic period of the 2–3 years there are a few patients as observed in this study.14 There are many asymptomatic healthy MP carriers during the epidemic periods, especially young children, who may serve as reservoirs for the spread of MP infection.22–24 It is natural that colonisation of MP during MP pneumonia epidemics can occur in asthma patients and old persons as well as in healthy young children and adults since colonisation does not mean the ‘infection’. The prevalent rates of MP colonisation between the asthma group and the control groups could be influenced by the MP epidemic year during the study period. Thus, patient selection bias could be considered if a study period is long and different in both groups. Wood et al 13 reported that the rates of MP colonisation in asthmatics and healthy children during the same study period were similar using a sensitive PCR method, suggesting that colonisation occurs equally in the two groups. One study reported that the status of asthma control and the lung function tests were not different between asthmatic patients with chronic MP infection and those without, indicating the similar severity of asthma between the group.25

In this study, the numbers of patient with RWE during a recent decade did not change with a rather decreasing trend in recent years. Moreover, we have experienced that asthma severity might change to a milder phenotype in Korea over time. A recent population-based study in Korea also indicated that the prevalence of asthma was reduced in recent years.26 Changing epidemiology in infectious diseases and infection-related immune-mediated diseases, including scarlet fever, pandemic influenza, acute rheumatic fever, acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and Kawasaki disease, has been well documented in Korea; initially severe disease phenotypes have changed to milder phenotypes over time.27–30 Because allergic diseases, including asthma, may be associated with various pathogen infections and environmental factors,31 32 it is possible that the changing epidemiology of childhood asthma occurs over time in the populations.

There are some limitations to this retrospective study. We evaluated only admitted patient groups with a part of the follow-up subjects at a single hospital. History of allergic diseases was not as precise as in International Study of Asthma and Allergies in Childhood studies. In our definition of RWE in the present study, the pneumonia patients with first wheezing, regardless of severity of respiratory symptoms, were not included in the asthma group. Considering the age distribution of patients, larger part of patients might be the transient recurrent wheezers and small part of true asthma patients who experience and progress recurrent wheezing into adulthood might be included in the RWE group. Further multicentre studies with prospective designs are needed for exact epidemiological relationship between MP infection and childhood asthma.

In conclusions, a small part of MP pneumonia patients had a subsequent wheezing after initial MP infection as well as those observed in other respiratory pathogen infections. Patients with RWE have a greater likelihood of experiencing wheezing than non-asthmatics when they had an initial MP infection, suggesting that MP infection is one of exacerbation factors in childhood asthma. However, we found no corresponding increase in the number of patients with RWE in MP pneumonia epidemic periods, and this finding may in part be explained that MP reinfection are very rare in children including patients with RWE or asthma as shown in this study.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs Eun-Kyung Kim, Sung-Churl Lee and other colleagues for help in

data collection during study period.

Footnotes

Contributors: KYL designed and conceptualised the study, and drafted the manuscript. JWR participated in preliminary data collection and wrote the initial manuscript. HMK and EAY analysed data and revised the manuscript for critical content. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The Catholic University of Korea Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital (DC17RESI0053).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data available from the Dryad Digital Repository: https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.3kt7fc2.

Patient consent for publication: Parental/Guardian consent obtained.

References

- 1. Atkinson TP, Balish MF, Waites KB. Epidemiology, clinical manifestations, pathogenesis and laboratory detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infections. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2008;32:956–73. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2008.00129.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lee KY. Pediatric respiratory infections by Mycoplasma pneumoniae . Expert Rev Anti Infect Ther 2008;6:509–21. 10.1586/14787210.6.4.509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stein RT, Martinez FD. Asthma phenotypes in childhood: lessons from an epidemiological approach. Paediatr Respir Rev 2004;5:155–61. 10.1016/j.prrv.2004.01.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Strina A, Barreto ML, Cooper PJ, et al. . Risk factors for non-atopic asthma/wheeze in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2014;11:5 10.1186/1742-7622-11-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beasley R. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet 1998;351:1225–32. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07302-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. . Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet 2006;368:733–43. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnston SL, Pattemore PK, Sanderson G, et al. . Community study of role of viral infections in exacerbations of asthma in 9-11 year old children. BMJ 1995;310:1225–9. 10.1136/bmj.310.6989.1225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Biscardi S, Lorrot M, Marc E, et al. . Mycoplasma pneumoniae and asthma in children. Clin Infect Dis 2004;38:1341–6. 10.1086/392498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guilbert TW, Denlinger LC. Role of infection in the development and exacerbation of asthma. Expert Rev Respir Med 2010;4:71–83. 10.1586/ers.09.60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kraft M, Cassell GH, Henson JE, et al. . Detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the airways of adults with chronic asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1998;158:998–1001. 10.1164/ajrccm.158.3.9711092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sutherland ER, King TS, Icitovic N, et al. . National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute’s Asthma Clinical Research Network. A trial of clarithromycin for the treatment of suboptimally controlled asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;126:747–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Varshney AK, Chaudhry R, Saharan S, et al. . Association of Mycoplasma pneumoniae and asthma among Indian children. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol 2009;56:25–31. 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00543.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wood PR, Hill VL, Burks ML, et al. . Mycoplasma pneumoniae in children with acute and refractory asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2013;110:328–34. 10.1016/j.anai.2013.01.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kim EK, Youn YS, Rhim JW, et al. . Epidemiological comparison of three Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia epidemics in a single hospital over 10 years. Korean J Pediatr 2015;58:172–7. 10.3345/kjp.2015.58.5.172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee SC, Youn YS, Rhim JW, et al. . Early serologic diagnosis of Mycoplasma pneumoniae pneumonia: an observational study on changes in titers of specific-IgM antibodies and cold agglutinins. Medicine 2016;95:e3605 10.1097/MD.0000000000003605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Papaetis GS, Anastasakou E, Tselou T, et al. . Serological evidence of Mycoplasma pneumoniae infection in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD: analysis of 100 hospitalizations. Adv Med Sci 2010;55:235–41. 10.2478/v10039-010-0031-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lee SI. Prevalence of childhood asthma in Korea: international study of asthma and allergies in childhood. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2010;2:61–4. 10.4168/aair.2010.2.2.61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee JH, Han KD, Kim KM, et al. . Prevalence of atopic dermatitis in Korean children based on data from the 2008-2011 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res 2016;8:79–83. 10.4168/aair.2016.8.1.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bacharier LB, Cohen R, Schweiger T, et al. . Determinants of asthma after severe respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2012;130:91–100. 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jackson DJ, Gangnon RE, Evans MD, et al. . Wheezing rhinovirus illnesses in early life predict asthma development in high-risk children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:667–72. 10.1164/rccm.200802-309OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kim CK, Chung CY, Kim JS, et al. . Late abnormal findings on high-resolution computed tomography after Mycoplasma pneumonia. Pediatrics 2000;105:372–8. 10.1542/peds.105.2.372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gnarpe J, Lundbäck A, Sundelöf B, et al. . Prevalence of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in subjectively healthy individuals. Scand J Infect Dis 1992;24:161–4. 10.3109/00365549209052607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dorigo-Zetsma JW, Wilbrink B, van der Nat H, et al. . Results of molecular detection of Mycoplasma pneumoniae among patients with acute respiratory infection and in their household contacts reveals children as human reservoirs. J Infect Dis 2001;183:675–8. 10.1086/318529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Spuesens EB, Fraaij PL, Visser EG, et al. . Carriage of Mycoplasma pneumoniae in the upper respiratory tract of symptomatic and asymptomatic children: an observational study. PLoS Med 2013;10:e1001444 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ansarin K, Abedi S, Ghotaslou R, et al. . Infection with Mycoplasma pneumoniae is not related to asthma control, asthma severity, and location of airway obstruction. Int J Gen Med 2010;4:1–4. 10.2147/IJGM.S15867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Kim BK, Kim JY, Kang MK, et al. . Allergies are still on the rise? A 6-year nationwide population-based study in Korea. Allergol Int 2016;65:186–91. 10.1016/j.alit.2015.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Quinn RW. Comprehensive review of morbidity and mortality trends for rheumatic fever, streptococcal disease, and scarlet fever: the decline of rheumatic fever. Rev Infect Dis 1989;11:928–53. 10.1093/clinids/11.6.928 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rhim JW, Go EJ, Lee KY, et al. . Pandemic 2009 H1N1 virus infection in children and adults: A cohort study at a single hospital throughout the epidemic. Int Arch Med 2012;5:13 10.1186/1755-7682-5-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kuem SW, Hur SM, Youn YS, et al. . Changes in acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis: an observation study at a single Korean hospital over two decades. Child Kidney Dis 2015;19:112–7. 10.3339/chikd.2015.19.2.112 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kil HR, Yu JW, Lee SC, et al. . Changes in clinical and laboratory features of Kawasaki disease noted over time in Daejeon, Korea. Pediatric Rheumatology 2017;15:60 10.1186/s12969-017-0192-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Atkinson TP. Is asthma an infectious disease? New evidence. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep 2013;13:702–9. 10.1007/s11882-013-0390-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hossaini RF, Ghaffari J, Ranjbar A, et al. . Infections in children with asthma. J Pediatr Rev 2013;1:25–36. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.