Abstract

Objective

To determine time to opioid cessation post discharge from hospital in persons who had been admitted to hospital for a surgical procedure and were previously naïve to opioids.

Design, setting and participants

Retrospective cohort study using administrative health claims database from the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA). DVA gold card holders aged between 18 and 100 years who were admitted to hospital for a surgical admission between 1 January 2014 and 30 December 2015 and naïve to opioid therapy prior to admission were included in the study. Gold card holders are eligible for all health services that DVA funds.

Main outcome measures

The outcome of interest was time to cessation of opioids, with follow-up occurring over 12 months. Cessation was defined as a period without an opioid prescription that was equivalent to three times the estimated supply duration. The proportion who became chronic opioid users was defined as those who continued taking opioids for greater than 90 days post discharge. Cumulative incidence function with death as a competing event was used to determine time to cessation of opioids post discharge.

Results

In 2014–2015, 24 854 persons were admitted for a surgical admission. In total 3907 (15.7%) were discharged on opioids. In total 3.9% of those discharged on opioids became chronic users of opioids. The opioid that the patients were most frequently discharged with was oxycodone; oxycodone alone accounted for 43%, while oxycodone with naloxone accounted for 8%.

Conclusions

Opioid initiation post-surgical hospital admission leads to chronic use of opioids in a small percentage of the population. However, given the frequency at which surgical procedures occur, this means that a large number of people in the population may be affected. Post-discharge assessment and follow-up of at-risk patients is important, particularly where psychosocial elements such as anxiety and catastrophising are identified.

Keywords: cessation of treatment, chronic pain, hospitalisation, opioid

Strengths and limitations of this study.

In Australia, it is unclear whether initial opioid use to manage acute post-surgical pain leads to chronic opioid use.

Using the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs database, we determined proportion of patients admitted for surgical procedures who went on to become chronic users.

Our study was limited to patients who were naïve to opioid therapy on admission to hospital.

Many surgical interventions, particularly orthopaedic interventions, are implemented to relieve pain and improve function in the patients already in pain and dispensed opioids; further research should identify the proportion of the patients who continue to persist with opioid use in these patients.

Introduction

Consistent with global trends,1 2 opioid use in Australia has risen significantly in the last 15 years.3 An Australian population-based study reported a fifteen-fold increase in opioid dispensings from 500 000 in 1992 to 7.5 million in 2012.4 In the International Narcotics Control Board 2015 report, Australia ranked eighth out of the 173 countries on the 2012 to 2014 opioid consumption as measured by defined daily doses for statistical purposes-.5 The escalation in opioid use coincided with the introduction of tramadol in 1998,6 7 followed by the relaxation of restrictions on subsidised opioid prescribing in 2005 to allow general practitioners to prescribe opioids for chronic, non-cancer pain.7 8 The rise in opioid use has also been accompanied by an increase in opioid deaths.3 4 9 An Australian study, using the National Coronial Information System database, reported a seven-fold increase in death associated with the use of the opioid oxycodone between 2001 and 2011, with the majority of deaths being accidental deaths where opioids were prescribed for an appropriate indication.9

With newer evidence available, it is now recognised that long-term opioid use for chronic, non-cancer pain is associated with significant harms and offers limited benefit, with people who take opioids for longer duration showing less improvement in pain scores and worsening function.10–12 Due to the limited evidence of the benefits of opioid use, the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners recommend intermittent opioid use for chronic, non-cancer pain.13 Efforts are now under way to minimise long-term opioid use for chronic, non-cancer pain, with guidelines supporting a range of strategies to minimise risk, including upper dosage limits, lowering doses when switching therapies, using risk assessment tools and developing agreed treatment plans.14 Treating psychosocial factors, including anxiety and catastrophising, are also important as these are associated with increased opioid misuse.15

There is potential for inadvertent transition of initial opioid use for acute pain to chronic use, such as in cases of injury or surgery where opioids are initiated for short-term pain relief only. Studies examining opioid use post discharge from surgical hospital admissions have found between 3% and 10% of people who were opioid naïve prior to surgery were still taking opioids at 1 year follow-up.16–18 The majority of the data on the extent of chronic opioid use as a result of prescription to manage acute post-surgical pain is from North America.16–18 The extent to which this pattern is observed in Australia is less clear. In a small Australian study involving 970 opioid-naïve patients prior to surgical intervention, 10% were using opioids more than 90 days post surgery. Using the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs database, the aim of this study was to determine the time to opioid cessation post discharge from hospital in persons who had been admitted to hospital for a surgical procedure who were previously naïve to opioids.

Method

This research was approved by the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA) Human Research Ethics Committee and the University of South Australia Human Research Ethics Committee.

Data source

The data for this study were sourced from the DVA administrative health claims database. The database contains details of all prescription medicines, medical, allied health services and hospitalisations (both public and private) provided to veterans and their dependents for which DVA pay a subsidy. The DVA treatment population in 2014 was approximately 220 000 veterans. DVA maintain a client file, which includes data on gender, date of birth, date of death and family status. Medicines are coded in the data set according to the WHO anatomical and therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification16 and the Schedule of Pharmaceutical Benefits item codes.17 Hospitalisations are coded according to the WHO International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition, Australian Modification.18

Study cohort

The study period was 1 January 2014 to 30 December 2015. The study cohort included veterans who were admitted to hospital in 2014 for a surgical admission, were eligible for full subsidy of all DVA subsidised health services (gold card holders) and were aged between 18 and 100 years. Gold card holders have full lifetime access to both public and private healthcare services. Surgical admissions were identified based on a variable in the DVA administrative health claims data indicating the type of hospitalisation; medical, surgical, not stated, other or unknown. Only the first surgical admission for a person in the calendar year was included. Persons who had been dispensed an opioid in the 6 months prior to the hospital admission for surgery were excluded, as were those who died during the hospital admission.

Opioid prescriptions

In Australia, medicines subsidised under the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme are captured in the data set if they are for community use, private hospital use (inpatient and discharge) or for discharge or outpatient use in public hospitals (all states and territories except New South Wales [NSW] and the Australian Capital Territory [ACT], thus NSW and ACT public hospitals were excluded). Inpatient use in public hospitals in Australia is not captured in the data set. Supply of opioids at discharge was defined to have occurred where the opioid was dispensed anywhere between 2 days prior to discharge and up to 7 days post discharge. All opioids listed under the Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Schedule were included (identified by ATC code N02A) except injectable products and oral solutions, as the latter were considered to be for inpatient use or for breakthrough pain. The opioids included a dispensing of any of the following codeine, hydromorphone, morphine, oxycodone, oxycodone with naloxone, fentanyl, buprenorphine, paracetamol with codeine, tapentadol and tramadol. All strengths of the products were included apart from paracetamol and codeine where only the strength with the codeine content of 30 mg was included.

Subsidised opioids are supplied in pack sizes sufficient for short-term use. As we could not account for actual consumption for products intended for short-term use, we used recommended dosing to estimate supply duration. On average, this was sufficient supply for up 2 weeks, dependent of pack size and dosing, for the most commonly used products. Cessation was defined as a period without a prescription that was equivalent to three times the estimated supply duration. In Australia, it is possible to obtain larger supplies under a prior authorisation policy. In these instances, sufficient supply is provided for up to 1 month of treatment; a 90-day period was used to determine cessation if a prescription had been supplied under authority with larger quantities.

Statistical analysis

The outcome of interest was time to cessation of opioids, with follow-up occurring over 12 months. Conversely, the proportion who became chronic opioid users was defined as those who continued taking opioids for greater than 90 days post discharge.

Descriptive statistics of the proportion of users ceasing opioid use at 90 days are reported. The cumulative incidence function was used to determine time to cessation of opioids post discharge, with death treated as a competing event. Subjects were censored at end of follow-up or where a subsequent hospital admission occurred. Cessation at 90 days was stratified by age (18 to 74 years, 75 to 84 years and 85 to 95 years), type of hospital (public or private) and ICD 10 chapter heading for the primary diagnosis of the admission. All analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4.

Patient and public involvement statement

There was no direct patient involvement in this study. We used the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs data set to perform the study analysis.

Results

In 2014–2015, 24 854 persons were admitted to hospital for a surgical admission. The majority were private hospital admissions (93%) as all veterans with gold card status are eligible for subsidised private services. Of these, 3907 (15.7%) were discharged on opioids. The proportion discharged on opioids was similar across the private and public sector, with 15.8% of patients in the private sector discharged on opioids compared with 15.3% in the public sector (p=0.60). Of those discharged on opioids, 31% were women and 69% were men and their median age was 71 years (IQR 66, 84 years) (table 1). When considering the type of surgery, opioid use at discharge was most frequent where the primary diagnosis related to the admission was within the musculoskeletal system (50.7%), digestive system (28.4%), nervous system (26.7%) or due to injury (24.0%) (table 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients admitted to hospital for surgical procedures who were discharged on opioids

| Chronic users n=90 |

Ceased n=3817 |

||

| Male | 51% | 70% | p=0.0001 |

| Age (median and IQR) | 81 years (68, 89) |

71 years (66, 84) |

p=0.0001 |

| Private hospital discharges | 79% | 93% | p<0.0001 |

| Public hospital discharges | 21% | 7% |

Table 2.

Opioid cessation rates at 90 days by primary diagnosis of admission

| Type of Admission | Total number discharged alive | Percentage discharged on opioids | Percent who ceased opioids at 90 days |

| Neoplasms (C/D) | 6548 | 10.2 | 99.2% |

| Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases (E) | 218 | 11.5 | 98.6% |

| Diseases of the nervous system (G) | 483 | 26.7 | 99.8% |

| Diseases of the eye and adnexa (H) | 5736 | 2.4 | 99.6% |

| Diseases of the circulatory system (I) | 2422 | 6.1 | 95.3% |

| Diseases of the respiratory system (J) | 292 | 38.7 | 99.7% |

| Diseases of the digestive system (K) | 1635 | 28.4 | 99.1% |

| Diseases of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (L) | 605 | 8.3 | 98.6% |

| Diseases of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue (M) | 3168 | 50.7 | 95.3% |

| Diseases of the genitourinary system (N) | 1190 | 9.2 | 99.1% |

| Symptoms, signs and abnormal clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (R) | 344 | 8.4 | 97.8% |

| Injury, poisoning and certain other consequences of external causes (S and T) | 1570 | 24.0 | 85.6% |

| Factors influencing health status and contact with health services (Z) | 581 | 7.1 | 98.0% |

| Other (A,B,F,O,Q) | 62 | 16.1 | 96.4% |

The opioid that the patients were most frequently discharged with was oxycodone; oxycodone alone accounted for 43% (predominantly the 5 mg strength in packs of 20), while oxycodone with naloxone accounted for 8% (mostly frequently in the formulation with 10 mg oxycodone in a pack of 28 tablets and oxycodone 5 mg in a pack of 28 tablets). Codeine with paracetamol was the opioid dispensed on discharge for 37% (most frequently in a pack of 20 tablets), while tramadol accounted for 10% (most frequently in a pack of 20 tablets).

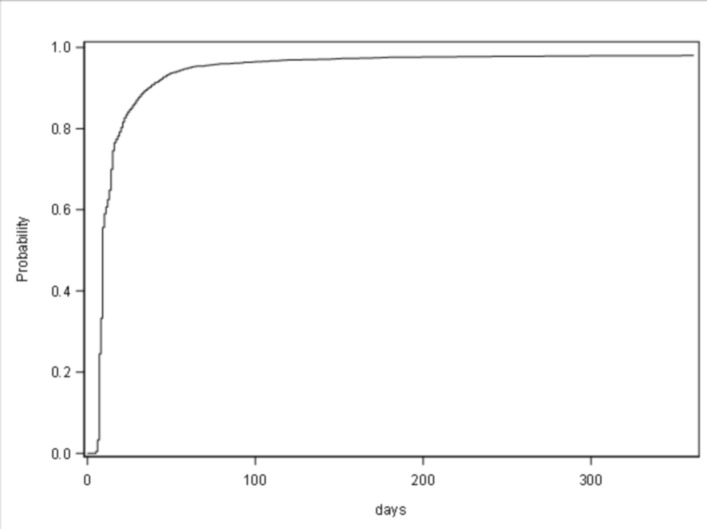

As presented in figure 1, at 14 days, 70% of the patients had ceased opioids. At 90 days 96.1% had ceased opioids and therefore, 3.9% were classified as chronic opioid users (figure 1). Opioid cessation rates at 90 days stratified by ICD 10 chapter heading for the primary diagnosis of the admission are shown in table 2. When stratified by the body system under which the primary diagnosis of the admission was classified, admissions for injury and other consequences of external causes (ICD 10 types S and T), had the highest proportion of chronic opioid users at 90 days, 14.4% chronic users or conversely 85.6% had ceased by this time (figure 2). Less than 1% of patients initiated on opioids and discharged from admissions with a primary diagnosis code in the G, H, J, K or N body class went on to become chronic users of opioids (figure 2).

Figure 1.

Time to cessation of opioids post discharge from hospital.

Figure 2.

Proportion of chronic opioids users at 90 days stratified by primary diagnosis of admission.

Discussion

Our results from this cohort of older Australians show approximately 96.1% had ceased opioid use by 90 days. Therefore, 3.9% of patients previously naïve to opioids went on to become chronic users, defined as more than 90 days of continuous therapy. Over half of the patients who had a surgery relating to musculoskeletal system and connective tissue were discharged on opioids, and 5% went on to become persistent users. About two in five patients admitted for surgery relating to diseases of respiratory system and about a quarter of patients admitted for surgery for diseases of the nervous system or diseases of the digestive system were discharged on opioids; however, less than 1% of the patients went on to become persistent opioid users.

Our results showed a lower prevalence of chronic opioid use at 90 days when compared with an Australian observational study involving nearly 1000 opioid-naïve patients awaiting surgical intervention.19 The study reported an overall prevalence of 10%; however, the prevalence varied between zero and up to a quarter depending on surgery type.19 Similarly to our results, a higher percentage of the patients who had orthopaedic or spinal surgery became chronic users when compared with the patients who had other types of surgical procedures. Previous research has shown that the biggest risk factors for persistent post-surgical opioid use were having orthopaedic (OR 4.6, 95% CI 2.0 to 10.8, p<0.001) or spinal surgery (OR 4.0, 95% CI 1.7 to 9.2, p<0.001).19 This is unsurprising given that orthopaedic surgeries are often the most painful procedures.20 The prevalence was much higher than that observed in our study cohort; 14% orthopaedic surgery patients became persistent opioid users 90 days after surgery while about one in four spinal surgery patients became persistent opioid users at 90 days after surgery. Because the study was conducted at a single private hospital in Sydney, there were only a few cases of other types of surgery including cardiothoracic, neurosurgery and ophthalmology. Orthopaedic and spinal surgery patients accounted for 55% of the study cohort and made up to 90% of the persistent opioid users.19 Thus, the high overall prevalence in the study is unlikely to reflect national prevalence data on persistent opioid users post discharge from hospitalisation for elective surgery. In Australia, approximately 15% of elective surgical admissions involve diseases of the musculoskeletal system.21

Our results are similar to international studies that suggest between 3% and 6% of the patients become chronic opioid users as a result of elective surgery.22 23 A population-based cohort study conducted in the US (n=36 177) showed that 6% of adults aged 18 to 64 years previously naïve to opioids continued to use opioids 90 days after elective surgery.24 Another population-based cohort study conducted in Canada (n=39 140) reported that 3.1% of patients aged over 65, previously naïve to opioids became persistent opioid users at 90 days after elective surgery.23 The study included different surgical procedures including intrathoracic, intra-abdominal, urological and gynaecological surgeries, but did not include musculoskeletal surgery.23 Our results show that the patients with surgery where the primary diagnosis was for a musculoskeletal condition were most likely to be discharged on opioids. Another Australian study,19the patients previously naïve to opioids who had musculoskeletal surgery were more likely to become chronic opioid users than those who had other types of surgery. In our study, admissions where the primary diagnosis was associated with injury and other consequences due to external causes were the group with the highest proportion continuing opioids beyond 90 days. Possible reasons could include injury due to trauma where prolonged recovery might occur, however, our results do highlight that this is a group for whom follow-up assessment of opioid use may be required.

While the overall percentage of persistent opioids users in Australia may seem low, the large number of persons who receive surgery each year means significant numbers of people are at risk of becoming chronic opioid users post surgery. Approximately 2.2 million elective surgeries are performed in Australia annually.5 Our data shows that about 4% of the patients discharged on opioids went on to become chronic opioid users. This suggests that more than 13 000 people may transition to become persistent opioid users following elective surgery each year. The estimated number does not take into account the patients who had emergency surgery or the patients who were exposed to opioid prior to surgery. Further, the number of surgical procedures performed every year is increasing.5

Strategies to reduce the likelihood of long-term opioid use post discharge need to be implemented.25 Risk assessment tools for opioid use are available,26–28 and while the majority have been developed for use in chronic pain clinics, consideration could be given to including assessments of this type either in pre-admission clinics or as part of discharge planning. The establishment of agreed treatment plans, that include discontinuation plans is also recommended.10 Anxiety and catastrophising have both been associated with increased risk of opioid misuse15 and so addressing these psychosocial elements is also an important need with opioid management interventions.

Our study was limited to the patients who were naïve to opioid therapy on admission to hospital. It should be remembered that many surgical interventions, particularly orthopaedic interventions, are implemented to relieve pain and improve function in the patients already in pain and also on opioids prior to surgery. An Australian study of the patients undergoing total hip replacement surgery found that 5% of the patients were chronic users after surgery, of which 60% had been chronic users prior to surgery, while 40% were new chronic users.29 Users of opioids prior to surgery also require post-surgical analgesic management plans with strategies for dose tapering and discontinuation.

Our study was limited by its reliance on administrative health claims data. We were not able to determine the severity of the pain. Further, while our data set captured supply of opioids to the patients, data on consumption of opioids was not available and whether all the opioids supplied were consumed is unknown. We stratified our results based on primary diagnosis of admission and not by procedure type. For each hospital admission, we could identify a primary diagnosis for admission, however all procedures that occurred during the admission are included with no determination made as to which was the primary procedure. This means that veterans have multiple procedure codes and we could not identify which was the primary procedure type. We also did not assess whether people re-started therapy after breaks longer than 6 to 12 weeks. Our data are limited to an older Australian population, and while this population is likely to be representative of other older Australians, the generalisability to younger populations groups is not known. We did not evaluate the risk factors for transitioning to chronic opioid use. We have previously published a paper that identified risk factors for developing persistent opioid use in a cohort of 9525 Australian veterans after total hip arthroplasty.29 The identification of risk factors for all surgery types is an area we are currently investigating.

In conclusion, opioid initiation in the hospital setting for post-surgical pain leads to chronic use of opioids in a small proportion of the population; however, the frequency of surgical procedures means many people are affected. Hospital analgesic policies should include strategies to support post-discharge assessment and follow-up of the patients at risk of becoming chronic opioid users.

Footnotes

Contributors: EER conceived of and designed the study, participated in data analysis and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. RL participated in data analysis and drafted the manuscript. ER and AM performed the data and statistical analyses and assisted in study design. NP conceived of and designed the study, and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was funded by DVA as part of the Veterans’ Medicines Advice and Therapeutics Education Services (Veterans’ MATES) program. DVA reviewed this manuscript before submission but played no role in study design, execution, analysis or interpretation of data, writing of manuscript or decision to submit the paper for publication.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the Australian Government Department of Veterans’ Affairs but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Helmerhorst GT, Teunis T, Janssen SJ, et al. An epidemic of the use, misuse and overdose of opioids and deaths due to overdose, in the United States and Canada: is Europe next? Bone Joint J 2017;99-B:856–64. 10.1302/0301-620X.99B7.BJJ-2016-1350.R1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rudd RA, Aleshire N, Zibbell JE, et al. Increases in drug and opioid overdose deaths--United States, 2000-2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;64:1378–82. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6450a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Roxburgh A, Bruno R, Larance B, et al. Prescription of opioid analgesics and related harms in Australia. Med J Aust 2011;195:280–4. 10.5694/mja10.11450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Blanch B, Pearson SA, Haber PS. An overview of the patterns of prescription opioid use, costs and related harms in Australia. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2014;78:1159–66. 10.1111/bcp.12446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. International Narcotics Control Board (INCB). Report 2015 – Narcotic drugs: estimated world requirements for 2016; statistics for 2014. New York: United Nations, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing. Pharmaceutical benefits scheme - PBS. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Karanges EA, Blanch B, Buckley NA, et al. Twenty-five years of prescription opioid use in Australia: a whole-of-population analysis using pharmaceutical claims. Br J Clin Pharmacol 2016;82:255–67. 10.1111/bcp.12937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing. Pharmaceutical benefits scheme - PBS. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Pilgrim JL, Yafistham SP, Gaya S, et al. An update on oxycodone: lessons for death investigators in Australia. Forensic Sci Med Pathol 2015;11:3–12. 10.1007/s12024-014-9624-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Frieden TR, Houry D. Reducing the risks of relief--The CDC opioid-prescribing guideline. N Engl J Med 2016;374:1501–4. 10.1056/NEJMp1515917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Braden JB, Young A, Sullivan MD, et al. Predictors of change in pain and physical functioning among post-menopausal women with recurrent pain conditions in the women’s health initiative observational cohort. J Pain 2012;13:64–72. 10.1016/j.jpain.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, et al. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:276–86. 10.7326/M14-2559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Prescribing drugs of dependence in general practice, Part C2: the role of opioids in pain management, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nuckols TK, Anderson L, Popescu I, et al. Opioid prescribing: a systematic review and critical appraisal of guidelines for chronic pain. Ann Intern Med 2014;160:38-47–47. 10.7326/0003-4819-160-1-201401070-00732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Arteta J, Cobos B, Hu Y, et al. Evaluation of how depression and anxiety mediate the relationship between pain catastrophizing and prescription opioid misuse in a chronic pain population. Pain Med 2016;17:295–303. 10.1111/pme.12886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Calcaterra SL, Yamashita TE, Min SJ, et al. Opioid prescribing at hospital discharge contributes to chronic opioid use. J Gen Intern Med 2016;31:478–85. 10.1007/s11606-015-3539-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Macintyre PE, Huxtable CA, Flint SL, et al. Costs and consequences: a review of discharge opioid prescribing for ongoing management of acute pain. Anaesth Intensive Care 2014;42:558–74. 10.1177/0310057X1404200504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lindestrand AG, Christiansen ML, Jantzen C, et al. Opioids in hip fracture patients: an analysis of mortality and post hospital opioid use. Injury 2015;46:1341–5. 10.1016/j.injury.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Stark N, Kerr S, Stevens J. Prevalence and predictors of persistent post-surgical opioid use: a prospective observational cohort study. Anaesth Intensive Care 2017;45:700–6. 10.1177/0310057X1704500609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gerbershagen HJ, Aduckathil S, van Wijck AJ, et al. Pain intensity on the first day after surgery: a prospective cohort study comparing 179 surgical procedures. Anesthesiology 2013;118:934–44. 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31828866b3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Admitted patient care 2015-2016: Australian hospital statistics. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brummett CM, Waljee JF, Goesling J, et al. New persistent opioid use after minor and major surgical procedures in us adults. JAMA Surg 2017;152:e170504 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clarke H, Soneji N, Ko DT, Dt K, et al. Rates and risk factors for prolonged opioid use after major surgery: population based cohort study. BMJ 2014;348:g1251 10.1136/bmj.g1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. International Narcotics Control Board (INCB). Report 2007 – Narcotic drugs: estimated world requirements for 2018; statistics for 2006. New York: United Nations, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sehgal N, Manchikanti L, Smith HS. Prescription opioid abuse in chronic pain: a review of opioid abuse predictors and strategies to curb opioid abuse. Pain Physician 2012;15:ES67–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Akbik H, Butler SF, Budman SH, et al. Validation and clinical application of the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP). J Pain Symptom Manage 2006;32:287–93. 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jones T, Moore T. Preliminary data on a new opioid risk assessment measure: the brief risk Interview. J Opioid Manag 2013;9:19–27. 10.5055/jom.2013.0143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jones T, Moore T, Levy JL, et al. A comparison of various risk screening methods in predicting discharge from opioid treatment. Clin J Pain 2012;28:93–100. 10.1097/AJP.0b013e318225da9e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Inacio MC, Hansen C, Pratt NL, et al. Risk factors for persistent and new chronic opioid use in patients undergoing total hip arthroplasty: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010664 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010664 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]