Abstract

Objectives

Health and social care systems, organisations and providers are under pressure to organise care around patients’ needs with constrained resources. To implement patient-centred care (PCC) successfully, barriers must be addressed. Up to now, there has been a lack of comprehensive investigations on possible determinants of PCC across various health and social care organisations (HSCOs). Our qualitative study examines determinants of PCC implementation from decision makers’ perspectives across diverse HSCOs.

Design

Qualitative study of n=24 participants in n=20 semistructured face-to-face interviews conducted from August 2017 to May 2018.

Setting and participants

Decision makers were recruited from multiple HSCOs in the region of the city of Cologne, Germany, based on a maximum variation sampling strategy varying by HSCOs types.

Outcomes

The qualitative interviews were analysed using an inductive and deductive approach according to qualitative content analysis. The Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research was used to conceptualise determinants of PCC.

Results

Decision makers identified similar determinants facilitating or obstructing the implementation of PCC in their organisational contexts. Several determinants at the HSCO’s inner setting and the individual level (eg, communication among staff and well-being of employees) were identified as crucial to overcome constrained financial, human and material resources in order to deliver PCC.

Conclusions

The results can help to foster the implementation of PCC in various HSCOs contexts. We identified possible starting points for initiating the tailoring of interventions and implementation strategies and the redesign of HSCOs towards more patient-centredness.

Trial registration number

DRKS00011925.

Keywords: patient-centered care, implementation, qualitative research, decision-maker, health and social care organizations, quality In health care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Based on purposeful sampling, we interviewed decision makers and addressed varying conditions and availabilities of resources across types of health and social care organisations to implement patient-centred care (PCC).

Our sample might suffer from selection bias as participants might have had a higher intrinsic motivation and interest in the research topic than non-participants. Interviews were only conducted with decision makers in leading positions so that differences in perspectives across hierarchies cannot be identified through this study.

Future research should investigate whether the identified determinants are similar in other regions, especially rural areas, as our explorations are geographically restricted to the city of Cologne, Germany.

Further analyses should apply a more fine-grained view on determinants located outside the sphere of individuals or organisations and may provide policy implications to foster PCC implementation in organisations.

Introduction

Patient-centred care (PCC), defined as ‘providing care that is respectful of, and responsive to, individual patient preferences, needs and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions’ (ref 1 p. 40), has become a guiding principle in health and social care. While concepts such as the Chronic Care Model2 or the Integrative Model of PCC3 further specify PCC, a common understanding of PCC is lacking in research and practice.4 Overall, PCC is conceived as a multidimensional concept that includes principles regarding perspectives of patients’ psychological, psychosocial and physical needs. The concept also suggests concrete activities for implementing PCC such as patient information, patient involvement in care, involvement of family and friends and patient empowerment.3 5 6 The implementation of these activities have been shown to be associated with more positive health outcomes.7 8 The understanding of PCC elements often depends on definitions of professionals and the context of health and social care. Nevertheless, there is a consensus about core elements of PCC across professional groups (eg, psychological needs and patient involvement), but the focus and emphasis differ.4 9

While the need and public attention for PCC have increased,10 health and social care organisations (HSCOs) face scarce resources (eg, financial, personnel and material) due to a shift from acute illnesses towards chronic illnesses and more complex treatment processes in an ageing society. Ultimately, such developments can increase economic pressures and require organisations to maintain, accumulate and preserve their resources, which is defined as resource-orientation11 and obstructs PCC.12 Therefore, health and social care systems, organisations and individual caregivers are constantly challenged to organise care according to the tenets of PCC under constrained resources.13

To ensure successful implementation of PCC, determinants that facilitate and obstruct PCC must be investigated and addressed at all levels and types of care.3 4 6 14 Research locates determinants of implementation success in health and social care at three levels: (1) the individual level (eg, personality traits and skills15 16 or attitudes17), (2) the organisational level (eg, goal setting,18 participating management,16 19 20 resources,18 infrastructure16 21 and culture22) and (3) the healthcare system level (eg, regulations and patients’ rights or climate of politics14). The organisational level is a mediator between the individual and the system level and combined with the individual level it plays a major role here, since at these levels specific activities for implementing PCC need to be carried out to fulfil patient needs.

Previous research has contributed to the understanding of determinants of PCC implementation. However, this partly results from the experiences of best-practice examples or organisations that have a great deal of knowledge on PCC (eg, refs 18 22). Moreover, due to varying conditions for different HSCOs types (eg, differences in financing structures between ambulatory and inpatient care organisations), availabilities of resources may differ across types of HSCOs. Within the German healthcare system, health and social care services are delivered at home (eg, from long-term outpatient nursing or palliative care facilities), in outpatient HSCOs (eg, offices for general and specialist medical care or psychotherapeutic care,) in inpatient HSCOs (eg, hospitals for acute medical care, rehabilitation clinics for restorative rehabilitating care or hospice care) or semi-inpatient HSCOs (day-care facility).23 These different contexts might be associated with different determinants for PCC implementation and strategies to deal with resource scarcities.

Our study aims to address these gaps and advance research on determinants for PCC implementation and strategies to address determinants across HSCOs. Implementation of PCC is here defined as decision makers’ perspectives about PCC activities related to patient’s needs that are or should be implemented in their organisational contexts and routine care. We aim to identify determinants of PCC implementation on the organisational and individual level using a conceptual framework.24 Moreover, coping strategies through which HSCOs may reconcile strained resources with an increasing pressure to implement PCC are explored. The study provides a general overview of determinants for PCC implementation across different HSCO contexts and identified possible starting points for initiating the tailoring of interventions and implementation strategies and the redesign of HSCOs towards more patient-centredness.

Methods

Study design

The data used in this article stem from the research project OrgValue (Characteristics of Value-Based Health and Social Care from Organizations’ Perspectives). OrgValue is embedded within the Cologne Care Research and Development Network (CoRe-Net) towards value-based care for vulnerable patients in Cologne, Germany,25 which currently includes three subprojects. The subproject OrgValue analyses the implementation of patient-centredness while considering the HCSOs’ resource orientation in the model region of the city of Cologne. The implementation of patient-centredness was assessed through face-to-face interviews with decision makers in various HSCOs contexts.11 This study presents results of the qualitative interviews with decision makers in HSCOs.

Sampling

The HSCOs included in the sample reflect all types of organisations in the city of Cologne, which are involved in the care of patients in their last year of life or patients with coronary heart disease and a mental or psychological comorbidity (patient groups studied within CoRe-Net).25 These included general practitioners (GPs) and private practice specialists (delivering symptom-oriented diagnostics and acute treatment), psychotherapists (delivering psychotherapeutic care), long-term outpatient care (delivering nursing and or palliative care), outpatient rehabilitation services and rehabilitation clinics (delivering restorative rehabilitating care), long-term inpatient care, including hospices, (delivering nursing or palliative care for severely ill patients) and hospitals (delivering acute medical care).

Participants of the interview study were clinical and managerial decision makers as key informants of these HSCOs caring for the selected vulnerable patient groups. Selecting key informants is a valuable approach, which is frequently used in order to assess the knowledge of employees who generally have decision-making authority.26–28 A preliminary panel discussion with practice partners from these HSCOs revealed that key informants have the most extensive knowledge about their organisation in terms of processes, structures, culture, resource allocation and deficiencies, strategies and organisational behaviour, for which we wanted to collect information in our study. It was important that the participants are or were involved in patient care or are in constant exchange with patients or care providers in the organisation. Depending on the type of HSCO, clinical and managerial decision makers can be different persons within an organisation (eg, hospital CEO and chief physician) or one person fulfilling two functions (eg, GP in private practice). By interviewing multiple representatives per HSCO type, information from multiple perspectives and different degrees of involvement in patient care or managerial processes could be obtained. Clinical and managerial decision makers were recruited via networks of practice partners and cold calling. Based on purposeful sampling,29 semistructured face-to-face narrative interviews were conducted.

Data collection

The semistructured qualitative interview guide29 revolved around three main questions:

How do decision makers define PCC?

What obstructs or facilitates the implementation of PCC in their organisations?

How do organisations deal with their resources and what resources are needed or lacking to implement PCC?

Each topic was operationalised by core questions facilitating story-telling and narrative-generating subquestions. The interview guide was flexibly adapted to the decision maker’s type of care organisation, the position or background, or the course of the conversation. The first step was to assess decision maker’s understanding about PCC according to Scholl et al 3 in order to ensure that there was a consensus on core elements of PCC (key questions were: ‘What characterizes PCC in your organization?’; ‘Do you remember a case where PCC was delivered at its best/not at all?’ [needs and activities]) (see online supplementary appendix 1). The discussion about the understanding of PCC was the basis to derive determinants of PCC implementation and strategies to address determinants across HSCOs in a second step (key questions were: ‘What were possible reasons that care was (not at all) delivered in a patient-centered fashion?’; ‘What are strategies in your organization to create the conditions necessary for PCC?’). Interviews were conducted face to face with one interviewee. In three cases, group interviews (with a maximum of three people) were conducted when decision makers brought in other organisational members who they felt were important to include when talking about the topics outlined in the study invitation.

bmjopen-2018-027591supp001.pdf (57.7KB, pdf)

All interviews were conducted by two researchers trained in interviewing with one leading and one assisting in varying combination. The interviews took place at the interviewee’s office or in an adjoining room (eg, a conference room) and lasted on average of 65 min (min: 29 min, max: 148 min). Interviews were audiotaped, transcribed verbatim and anonymised by an external professional typist. Interviewees provided written informed consent before the interviews.

Patient and public involvement

There was no patient involvement in this study. For the purposes of participatory research, representatives from the health and social care practice were involved in the development of the design of the overall research project (OrgValue) at the outset of the study. Representatives were contacted through the CoRe-Net. In a collaborative meeting, participants discussed in terms of the qualitative study how to gain access to the study participants, the extent of interviews and who should be the appropriate contact person as decision maker in the respective type of organisation. All results of the overall study will be disseminated to the participants.

Data analysis

All transcripts were entered into MAXQDA software (VERBI GmbH, Berlin, Germany). Qualitative content analysis was chosen to explore the participants’ unique perspectives in order to extract on the descriptive level of content and not to provide a deep level of interpretation and underlying meaning.29 The analysis of the interview content was conducted independently by two multidisciplinary researchers (KIH, HAH and VV in varying combination) to ensure the validity of the data interpretation by minimising subjectivity of data interpretation.29 A coding frame including core elements of PCC and determinants for implementing PCC was developed by combining deductive and inductive approaches. First, content-related codes were constructed by descriptive coding/subcoding and provisional coding/subcoding.29 The conceptual model of Scholl et al 3 was used to identify codes that denoted the decision maker’s understanding about PCC activities related to patient’s needs (see online supplementary appendix 1). Several dimensions of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)24 were used to structure and combine the identified codes that denoted determinants of PCC implementation. The CFIR is a well-established framework that combines existing theories for determinants of effective implementation and divides five categories of determinants: intervention characteristics, outer setting, inner setting, characteristics of individuals and processes.24 We used the categories ‘inner setting’ and ‘characteristics of individuals’ of the CFIR to capture and categorise the determinants of PCC implementation.

The inner setting relates to the HSCOs’ inner arrangements of strategies, structures, processes and culture. Characteristics of individuals focus on the employees within the HSCOs. As described above, determinants for PCC implementation that relate to the healthcare system and interactions between HSCOs settings (outer setting) were gathered but were not part of this study. Finally, in our case, PCC was not one specific formalised intervention, and therefore our study did not intend to explore processes of actual implementation but rather determinants of PCC implementation.

The coding frame was repeatedly discussed and recoded among the researchers and a group of qualitative research experts to ensure its consistency and validity.29 Online supplementary appendix table 1 provides an overview of the considered categories including a short description for each code. The results are presented as textual fragments of the participants’ narratives to illustrate the relationship between the theoretical concepts and the data. Relevant passages were translated into English for this article.

bmjopen-2018-027591supp002.pdf (52.6KB, pdf)

Results

In total, 20 interviews were held with 24 decision makers on 20 different dates. The 24 interviewed decision makers divided into private practice GPs and specialists (n=3), psychotherapists (n=3), long-term outpatient care (n=4), outpatient rehabilitation services and rehabilitation clinics (n=4), long-term inpatient care (n=5) and hospitals (n=5). Online supplementary appendix table 2 provides an overview of interviewee characteristics in the full sample (n=24).

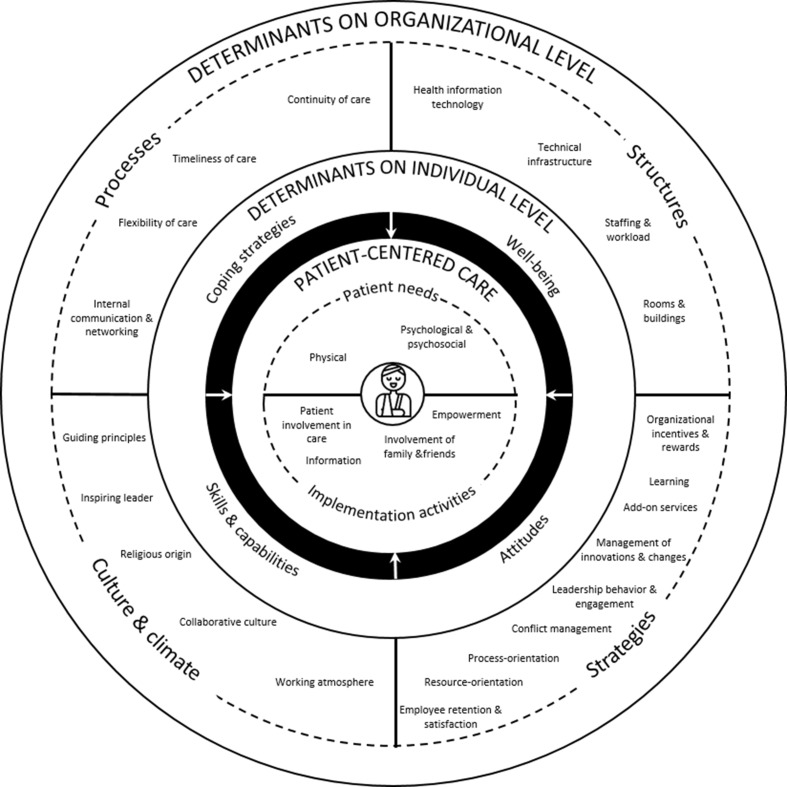

The remainder of the results section is structured along our research questions (figure 1) and according to the CFIR scheme (online supplementary appendix table 1). Determinants of PCC implementation related to the organisational (inner setting) (table 1) and individual level (characteristics of the individual) (table 2) are described with emphasis on organisational strategies to maintain, accumulate and preserve resources under increasing demands for PCC (resource orientation).

Figure 1.

Determinants of PCC implementation at the organisational and individual level. PCC, patient-centred care.

Table 1.

Determinants of PCC implementation related to the organisational level (inner setting)

| Inner setting | Quotes |

| Strategies | |

| Organisational incentives and rewards | ‘We have introduced idea management in which all employees can participate. [description of innovation] is then acknowledged and the employee then receives […] a goodie for participation; it is then assessed in our QM steering committee, the idea and the employee, or if a team participates, they then receive a […] financial compensation’. ‘I mean, we also have some things go wrong, of course, someone or other makes a mistake sometimes here as well; you then go there and say, we made this mistake; we try to limit the consequences, but we handle it openly. […] Then the covering up, denying, etc., starts. I mean, I also used to have employees that exhibited those behaviors, but as I said, I used to have them’. ‘What we cannot do, we cannot evaluate whether the implementation has been successful. We can’t do that. So we can, I say, rather only give incentives and motivate and be supportive in the sense of as long as voluntariness… So if I am person-centered…. As long as they allow this in the organization’. |

| Learning | ‘But the starting point are the cases, and in every quality circle, so every quarter of a year, the patient feedback – this includes not only complaints but positive things as well – it is then presented to us by the complaints officer […]. So they are specific patient assessments’. ‘Again, the patient is ultimately unable to assess that [medical treatment quality]. Rather, it tends to be the softer things. So, were you friendly to people; did the food taste good? Of course, those are also all things that play a much greater role for the patient because the patient can also assess them. So I always kind of claim that a hospital that has great food is popular with patients because the patient then says, well, if they can cook well, the rest will surely work well too’. ‘If an organization has longstanding employees who have not been permanently in learning status or have undergone changes, then they are rigid organizations, then it is difficult to break them open by new employees. They won’t stay either’. |

| Management of innovations and change | ‘So I see the health care sector or the hospital sector as a very conservative sector, so the willingness to do things anew is not very pronounced. So because medicine is certainly also, I say, an experiential science, perhaps it is also connected with it. […] since so many people interact like gears in a machine, it is of course also extremely difficult to turn any adjusting screw without completely getting the overall system out of step. Well, that is. . as an executive director, you have to a little bit resist the temptation of saying, we will just do that now’. ‘[…] this works very well when an innovation promises advantages. So that’s the crucial thing you have to show the employees. have to prove to employees that what you bring to the market is an innovation that ultimately makes everyday life easier’. ‘And that is why change, of course, must be well managed. And it is also quite clear, probably just like in all other professions that young employees are better able to engage in change […]. And there you just have to convince in a completely different way and bring along some solutions so that these people can also be engaged’. ‘My problem is the team members, because they say “you don’t change anything, too”’. |

| Leadership behaviour and engagement | ‘[…] then we are back to the management system again; how do I place people in certain functions and how do I design the tasks so that they can practice person-centeredness as well. Or can do so in their work’. ‘[…] And I find it very important, regardless of vacancy and personnel need, I find the application procedure extremely important. Very, very important. And only because I need someone does not mean that I will take anyone […]. And so I do that in every interview; I tell everyone, think about what is important to you. How would you want to be treated, or what if it was your mother? And to really stay alert with everyone and look’. ‘So because there are very different interests […]. This means that the nursing staff is subject to nursing services. And the doctors to the medical service. This means that the doctor is medically authorized to give instructions, but not with regard to the organization, which makes many processes inefficient. This has now become possible […] so here the head physician also conducts staff interviews with all non-medical staff. And we see ourselves as a team. All in all, this works very well’. |

| Conflict management | ‘When there are conflicts, they must be discussed, but outside of patient care. And of course not in the presence of the patient. We really do not do that here’. ‘The fact is, we of course have to ensure here that we have our heads clear for our work. And that means that we all [.] are very attentive in dealing with each other, that we do not allow any conflicts to drag on but think in terms of solutions in that area as well. In rapid solutions, that is’. |

| Process orientation | ‘Of course, there are exceptions, but it should also be the case, I think, that this is already a little QM-orientated, of course, the procedures are controlled. Which we also monitor, help guide, and then again evaluate after the fact’. ‘[…] Here […] the issue is to efficiently care for routine patients, consistently at maximum medical quality’. ‘[…] we [doctors and nurses] feel we need more staff. […] the management always says “you must first try this by restructuring”, then also partly foreign management consultancies are brought in […] as an independent company, yes, they look at the processes, then make suggestions to the management as to how they see the moaning at our level is justified, yes or no’. ‘What is relatively rigidly specified, for example, is to keep to certain times. […] but with which elements […] that is then with us’. ‘But the perfect care is going wrong right now. Because we have far too many institutions around the patient that can no longer look at the actual core at all. Too many organizational structures’. ‘You can’t have a checklist on the patient. Because every patient comes completely different. The checklist is a great unit around structures and perfect management of a practice, structure in the case work, […] the structures that are not patient structures are right. So the whole thing around is perfectly organized’. |

| Resource orientation | ‘[…] We have a good rate of skilled employees; we are at, I think, [>65] percent right now […]. That is good. Nevertheless, if I advertise a nursing assistant position because I cannot only hire specialists, because then I do not have enough people because they are more expensive than the assistants. Sure, I have to find a good mix’. ‘Well, here, we always tend to choose medical quality over money here. But if I wanted to run it that profitably, then I could not maintain the medical quality’. ‘Patients are at the center, as well as I understand it now, and everything else is orientated around them. It really isn’t such a small effort, if you consider how many not very inexpensive people then virtually take care of a patient. […] And the whole thing then works where you also focus on certain things, yes, centered or concentrated. And does not claim to treat almost all clinical pictures in the same way with such a complex and complete treatment or to treat patients with these many clinical pictures in this way. […] Beds in the hallways. Yeah? But then you cannot provide adequate care at all with the same resources. That is the same way. Yeah? Then we have to say, either we stop taking more patients’. |

| Employee retention and satisfaction | ‘And to that extent […] you have to also […] consider, well, working conditions you create for employees. And that, too, I would say, leads to, when employees feel comfortable, when they are not rushed, them ideally being able to be patient-oriented in their work or communicating differently with patients’. ‘Anyway, I believe that patient centeredness does not work without employee centeredness. Because especially in a job where you work so closely with people […]. When people are not well, they cannot take good care of patients. And we try to manage that somehow through numerous small and medium-sized measures, whatever we can afford (grins). […] [E]very Monday, there is a fruit basket, for instance. […] And that is a little measure, that does not cost a whole lot, but as far as the responses we get, it is pretty well received’. ‘Of course, the salary is part of that, but this is actually no longer the decisive factor. [.] It is really the team, the reliable off-duty time, can I have that or not? And the less or the more vacancies I have, the harder it becomes to ensure reliable off-duty time, weekends off’. |

| Add-on services | ‘Well, working with family and friends, that simply happens. And this work is important to us, but it is nowhere to be found in the expert opinion to determine the long-term care dependency level; it does not ask whether you constantly have to talk with the wife or whether you have a friend or family member […] all that does not exist at all. But lots of friends and family members do need to talk with us. Whether because of a bad conscience or worries or whatever. That is not reflected anywhere’. ‘In the rooms area, I will say, or everything that has to do with the quality of lodging, all the way to entertainment, well, those are really the hotel components that play a great role too. […] But the patients clearly have hotel-like expectations from the hospital. […] And particularly when patients are feeling better, when the level of suffering recedes, the hotel-like expectations are there, and that I believe is something that patients would clearly perceive as patient orientation too because these topics, if you look at [Hospital assessments website] or things like that, very often are, well. . [the] medicine is assumed to be OK’. |

| Structures | |

| Staffing and workload | ‘[…] we are always fully staffed to our nurse-to-patient ratios. And it is still always tight. A week like this, where five are sick, that is extremely high; we do not have a high illness rate. […] Then I am truly almost at my wit’s end […] As long as no staff is added, no new clients, no new individuals in need of care can be admitted’. ‘That gives you an idea of how many residents are being cared for by one caregiver. And this inevitably often already really leads to an assembly line care’. ‘This means that the number of employees depends on the number of patients. And there is just a staff index, if it is overfilled it is nice for the patient, bad for us, because we don’t get paid’. |

| Technical infrastructure | |

| Equipment | ‘Or someone comes in from the hospital and suddenly requires oxygen. And stands here without an oxygen unit. But I don’t have something like that sitting in the basement’. ‘I also work with flip charts, still. Gladly. Because I noticed that what you can see is quite different to what is merely said. Patients take pictures of it, or sometimes, they take the flip chart paper with them. Yeah. So there are quite a few things. I work with chairs or with postcards, with cuddly toys, with drawing, with stones. So with everything that makes it more tangible. And somehow helps to translate the words and make them palpable’. |

| (Health) Information technology |

‘When referring a patient from A to B […], well, when someone comes from the outside […], I would say, we physicians in Germany mostly communicate by letter or by fax. The fax is truly still the standard. And I find that so creepy’. ‘When we have generated the nursing plan, this standardized nursing plan, which we of course individually complete with the needs of the guest, we add measures here […]. [W]e use IT-supported documentation here so that we can go to the various levels at any time […], in each shift, whether the early shift, late shift, or night shift, ultimately to have reminders of what is to be done now’. |

| Rooms and buildings | ‘It is a little cramped here (laughing) for some exercises I do. But I am lucky in that my colleague toward the front of the building has a larger room. Right? Right. So there are solutions for that’. ‘We then tried by means of the TVs you saw in the waiting rooms, by offering drinks […] To try, although you cannot directly reduce the waiting time, to make it as tolerable as possible. That works to some extent, and to some extent it does not’. ‘We mostly have double-occupancy rooms. We do not have bathrooms in the rooms but have to take the respective measures […] across the hallways to the showers and such. So in terms of the […] environment, this is really not ideal’. |

| Processes | |

| Continuity of care | ‘This means that we try to manage in terms of the duty roster in such a way that the next days of the same shift, the same staff member always sees the resident. So that the resident does not constantly…. he already has to get used to the early shift, late shift, night shift, to different faces. But to ensure that, if possible, the same staff member goes in’. ‘[…] most of them […] know that they get all-round care here […] that we take care of patients even after discharge; they then come to us again for outpatient wound checks, for consultations. Of course, that is very time-intensive, and it costs the management more than if they were sent away immediately afterward, but that is what patients applaud here and why they like to come here’. ‘I believe that many patients benefit from having someone to look after them over a longer period of time. Especially since many patients also have many psychosomatic problems. I think it is important to stay in touch and not always cover all sorts of things directly with examinations’. |

| Timeliness of care | ‘Professional competencies [have] specified that within 24 hours, a corresponding, adequate medical device must be available […]. That means you have to submit an application to get this alternating pressure mattress. Then the person responsible for the budget has to check if that is in the budget or not, OK? Then I might have to ask the management board. In the meantime, the user who actually needs it has developed a skin injury’. ‘This means that we are pleased that we have visits twice a week and that the laws ensure that if you have SAPV, cooperation, you can reach a doctor 24 hours a day. And that is of course also the case here. And the residents benefit from this because as soon as the condition or symptoms change, we can react immediately and very quickly’. ‘It is simply illogical for me, if there is an insurance card, why not let the card be given and send the patient directly to a treatment room. […] And then you can say “thank you for the card, you get it right back, now go to the treatment room”, it doesn’t matter whether he is Roman Catholic and whether he signs the treatment contract […] at the moment. We want the patient to be well. The patient, he is in pain’. |

| Flexibility | ‘We have a very young man with [neurodegenerative disease]. […] Very advanced already. For him, I need completely different services than for an 85-year-old who was a wife and mother […]. They are worlds apart. And I find that totally important, and it is our job to see who needs what’. ‘[…] what else is really important is that depending on the way the individual feels that day, you can also respond to changing needs, right? That you don’t say, well, you get a partial bath five times a week and a complete bath once a week, and on that one day, the person does not want to or cannot get into the bathtub or shower, and, well, how do you respond then, right?’ |

| Formal communication | ‘We do case conferences regarding the residents. We say, there is a problem, or a resident has a wish, how can we respond to it? The social support service participates in team discussions’. ‘And the aim is basically to present pretty much every patient to the tumor board once […] to obtain a recommendation that is based not on the opinion of only one physician but on the opinion of many’. ‘The one in the back must know what the one in front is doing. Either through continuous communication, or as we have just done, through communication via computer. It says: the patient is there, you have to call there immediately, please pay attention to this or if someone is in a bad way. And also on call. Some kind of emergency. A pick-up and drop-off service is organized. The patient is […] transferred to the ward. In my time, […] we went down to the intensive care unit as a team of doctors and nurses, […], the doctor spoke with the doctor, the nurses with the nurse, we exchanged, we exchanged crosswise […]. […] a transport service […] has no exchange at all. This means that one must orientate oneself according to the file situation, documented file situation. How much more work, how much more time and how much more insufficient is this?’ |

| Informal communication | ‘[…] those are actually short paths […] [Y]ou talk to each other a lot, you do a lot unofficially too, that can have advantages and disadvantages […]. You just call your colleague; well, for QM, a lot of what we do may not be official enough, but (laughing) on the other hand, it is also very effective, rather than always sticking to these, well, otherwise regulated pathways’. ‘Well another obstacle is certainly, of course, the hierarchy at the hospital, which is, of course, extremely pronounced in comparison with other sectors. That is changing to some extent. But it certainly through […] separate departmental structures […] and the collaboration between the three professional groups in the hospital’. |

| Culture and climate | ‘The patient feels whether it harmonizes and functions in a practice or not immediately. These are looks, this is the tension, this is the vibration in a practice, the patient immediately notices this. […] And the moment he opens the door, the radar is on, “is everything is okay here, can I stay here, am I really in a good care here”. And when the patient feels tension, in a hospital, in a practice, and realizes that they are already grumbling at each other, the fear is actually already there for the patient, well, if they are already yelling at each other here, “where am I? I hope I get out of here all right”’. ‘Well, for me, that has a lot to do with values as well. And I think that due to the fact that we are an enterprise serving ideological ends and are affiliated with enterprises purely serving ideological ends, we do encounter different attitudes, among staff members too […] I do experience great willingness too. In the general setting, to really commit to focusing on the patient’. ‘And the rest is really cultivated and also lived corporate culture, simply to say that there is a good spirit here’. ‘Because here in a manageably large house a relatively good togetherness prevails, this usually also succeeds, I say, to get people into this mainstream somewhere’. |

PCC, patient-centred care.

Table 2.

Determinants of PCC implementation related to the individual level (characteristics of individuals)

| Characteristics of individuals |

Quotes |

| Coping strategies | ‘But still, sometimes it is just a fact that such a topic really touches you. I would say for myself, yes, that makes it easier for me, when I do sometimes have short pathways somehow. And I think there is a difference whether you call somewhere and say, listen, I just had an extreme case. Or whether you meet and talk in the kitchen’. ‘It might be something very personal, just here, where someone reminds me of things that I have a problem with myself. Or I’m in trouble and I’m struggling. […] Then I can’t be helpful, because I am always affected by it then, right? For example. Or that the patient thinks himself “no, I can’t do that with him either”. Like this. Or do I not want to or am I afraid of whatever […]. And then it doesn’t fit and then you can also end the therapy… Should you end it. Then. Or say, you’d better find someone else. Absolutely’. ‘You can have the highest salary, but if you cannot apply what you have learned, you will become worn out after some time; then you will not want to do it any longer either’. |

| Physical and emotional well-being | ‘[…] well, residents can only do as well as the staff members are doing. That is very, very important to me when managing a facility; the residents are important, but so are the staff members. When the staff members are not doing well because I am an unfair boss, I have created really bad working conditions, then it is impossible for the residents to do well’. ‘And also try to suppress any emotional fluctuations on my part, right? So not to carry them outside, because that must be. he [the patient] is supposed to be comfortable here. And then somehow not somehow affected by our sensitivities’. ‘And that also means that when I care, I say, in the sense of person-centeredness, I must also recognize where my limits are. So where I can no longer deal with certain person-centeredness. But I have to be able to say that. This includes a value framework’. |

| Skills and capabilities | |

| Psychological traits | ‘If you work with people, you need empathy’. ‘But a staff member can also say, wow, Ms. X, I really have a problem with her, or I do not like her. I think that is human, and in the team, you have to then see to it that you organize it differently. And not put two people together who dislike each other’. |

| Professional qualifications and development | ‘And if a temporary employment agency tells me, this one has lots of experience, and then I have someone standing here and he does not even know at all how to bathe someone or how to dress someone’. ‘Since we […] particularly have employees with lots of experience, not just continued education’. ‘[…] we benefit a lot from the fact that we all have the additional training as a palliative specialist so’. ‘The patient also sees a pick-up and drop-off service. […] That’s someone who says, “yes, I have to move a bed”. That’s why the bed gets stuck here and sometimes bangs there. Patient may have a thigh fracture, the patient bangs against the elevator wall, the patient cries out, classical picture, because the carrier knows nothing at all to deal with it’. |

| Communication (verbal) | ‘I always try to package that well. Because I have been doing that for [>10 years]. And I have noticed that when you throw survival statistics, etc., at patients, particularly patients with a poor prognosis, patients are very quickly shocked and demoralized. I am always open with my patients. I do not lie to my patients. Out of principle. So I do not lie to make things easier for them either’. ‘You […] can have the best medicine on the one hand if […] no reasonable communication [takes place] with the patient, the patient will not experience it as patient-oriented. Then the patient will go home and say, I do not know what is going on with me’. |

| Attitudes towards PCC | ‘They all bend backwards here […] that the people here feel very comfortable. And that they feel dignity’. ‘[…] and then, it is typically the mobile nursing service, particularly when there are no friends or family, who then morally, ultimately, and ethically feels obligated to really jump in and organize and do and whatever’. ‘Then, I think, if we did not have such good staff members who are so committed, it really could hardly be done’. |

PCC, patient-centred care.

Determinants of PCC implementation related to the organisational level: strategies, structures, processes and culture

Strategies

Organisational incentives and rewards

In single cases, interviewees described informal (eg, appreciation) and formal rewarding systems (eg, remuneration for innovative ideas relating to care improvements or problem-solving within the organisation). In contrast, showing non-patient-centred behaviour was considered inappropriate and could ultimately threaten continuation of employment. Cancellation of contracts was described as one organisational policy to deal with deficiencies in PCC provision.

Learning

Interviewees described the importance of gaining information on the organisation’s level of patient-centredness, but the form and extent of collecting such data varied among care providers. Formalised learning measures included quality circles with regular quality surveys, key indicator analyses, risk profiles, supervision, checklists, patient surveys and case reviews within the team. These were reported rather by inpatient, larger HSCOs. Less formal forms of gathering information covered complaints by patients, relatives or staff members. The value of information of these data was evaluated differently across decision makers. For example, the extent to which patients could make a meaningful judgement about quality features—especially concerning the medical treatment—was questioned.

Management of innovations and changes

Some interviewees perceived the German healthcare system and the organisation they were working in as rigid and reluctant to change. The implementation of innovations in these contexts was therefore perceived as a complex management task, because it requires comprehensive adaptation processes, even with less complex innovations. Decision makers described their dependency on the readiness (willingness and competency) of the middle-level management and the front-line staff for successful implementation of innovations throughout the organisation. Both levels need to accept the value of the innovation and implement it in their daily actions. To increase readiness, it requires conviction about the innovation as well as participation and communication in the implementation process. Particularly opinion leaders should be addressed. Medical care centres were described as more innovative than others in terms of structures, that is, care structure and processes.

Leadership behaviour and engagement

Decision makers described it as important to set an example and to define expectations for a patient-oriented attitude or a ‘good spirit’. To support PCC, control was exerted, for example, by considering the applicant’s attitudes towards patient orientation as decision criteria in the hiring process of employees and management staff. Another strategy mentioned was to demand and encourage for implementation and also to monitor it. Leaders who were not directly involved in patient care felt committed to fostering an environment in which front-line caregivers can do their job with the patient. It was also mentioned that employees need to be able to make decisions independently of their supervisor, to have flat hierarchies and to formulate clear responsibilities.

Conflict management

In general, leaders perceived it as a duty and strategy to ensure smooth processes and to manage conflicts. Conflicts within the team were named as one reason for a negative working atmosphere. Patients were described as sensitive to negative moods among team members and as affected by these, particularly in terms of satisfaction and well-being. Therefore, one provider stated that conflicts should never be dealt in front of a patient and that care provision should always be prioritised.

Process orientation

Clear-cut definitions and processes helped to warrant adequate care of patients. Time management was seen as an important component for efficient care. Still, a certain degree of flexibility within the processes was important to tailor processes to the specific needs of a patient (see: flexibility of care). For example, a high workload (eg, too many patients; insufficient number of staff) disrupted a smooth flow of processes and provision of care by increasing waiting times and decreasing the time devoted to the individual patient. Interruptions in the process must be resolved, (eg, using strategy meetings and quality management evaluations). The importance of interdisciplinarity within process flows and planning was emphasised. Standardised guidelines (eg, clinical practice guidelines) were considered as a recommendation for objective patient needs but not as a strict guideline for specific patient care. It was reported that process steps were defined in inpatient nursing using the Plan–Do–Check–Act Cycle to adapt guidelines to the needs of the residents. Checklists were occasionally used to ensure compliance with process steps, especially when the patient is admitted. The relevance of effective process design seemed particularly high in centres (eg, breast care centres and medical care centres).

Resource orientation

Interviewees mostly linked PCC to the availability of various resources. Scarcities of personnel resources, which were described as strongly related to a lack of financial resources, were mentioned most often. For example, organisations had to draw on (more affordable) ancillary staff. This issue was exacerbated by the limited availability of adequately skilled staff and professional staff facing a high workload during their shifts. Often, decision makers perceived difficulties in striking the right balance between PCC and quality demands, on the one hand, and scarce resources and rigid guidelines, on the other. Compared with other organisations, outpatient and inpatient nursing facilities particularly highlighted the problem of scarce resources.

Interviewees described different strategies to maximise PCC under scarce resources. For example, fostering personnel development (eg, skills and competencies) was identified as supportive to PCC. Collaboration in networks of different providers was another strategy to manage lacking resources for fulfilling patient needs. It became clear that larger organisations (eg, hospitals) possess broader financial leeway to overcome scarcities or to invest in staff. Moreover, interviewees assumed that non-profit HSCOs tend more to use financial resources for the benefit of PCC (eg, staff number or quality) which, according to the interviewees, might be handled differently in organisations under for-profit ownership. Another strategy mentioned as a vision was the organisation’s focus on a limited range of healthcare services (eg, with regard to the complexity and of care needs).

Employee retention and satisfaction

According to the interviewees, caregivers cannot make patients healthy and satisfied if they do not feel equally valued. Therefore, employee satisfaction emerged as one determinant for PCC that is related to resource orientation. Various strategies were mentioned to strengthen or preserve the employee’s resources, foster staff satisfaction and ultimately tie professional staff to the organisation. Those included, for example, adequate payment, occupational health management, a good working climate, work–life balance (eg, time for leisure and recreation), opportunities for further training, job autonomy and supportive technical equipment.

Add-on services

Organisations offered additional (eg, non-reimbursed) services for patients, which primarily targeted the dimensions of psychosocial needs and continuity of care. Specific activities concerned, for example, services for relatives and care outside consulting hours or beyond the treatment period. Although these activities were often not reimbursed, decision makers perceived them as crucial for patients and the care process. Another incentive for providing additional services was peer pressure, meaning that organisations offered additional services (eg, entertainment) to gain a competitive advantage for their organisation or increase business development.

Structures

Staffing and workload

Interviewees described that the number of staff available, the ratio of professional to ancillary staff and the workload influenced PCC. Staff-related factors (eg, availability) and the staff–patient ratio were described as a precondition for the provision of patient-centred nursing. Moreover, these factors determined flexibility of the organisation in times with high sick leave. Particularly in long-term inpatient care, temporary employment was described as inevitable yet undesirable (see: professional qualification). Organisational strategies to strengthen personnel resources included the reinvestment of financial surpluses into the body of personnel.

Technical infrastructure

Across organisational boundaries, several interviewees saw available equipment as a precondition for adequate patient treatment. Mostly, the term was automatically referred to as medical or technical equipment. One outpatient caregiver described that patient communication was complemented by use of non-technical equipment (eg, flip charts) to increase patient involvement in care.

Health information technology was generally confirmed as increasingly relevant during the care process. Different examples for the application of information technology (IT) in healthcare practice were mentioned, ranging from the integration of individual patient preferences by electronic care planning to the use of tablet PCs to assess patient-related information. Sometimes, insufficient or fragmented IT structures were described as a challenge in everyday practice, for example, by hampering cooperation with other care providers or by consuming too much time.

Rooms and buildings

Interviewees described that the arrangement or design of rooms and buildings should ideally match the care processes and meet patient needs. Hospitals and other inpatient providers faced historically developed architectural structures that could hardly be changed. Strategies to deal with physical barriers included a redesign or interior change of rooms and buildings to the fullest possible extent (eg, media entertainment). Outpatient care providers mentioned the possibility of shifting from one room to another on demand.

Processes

Continuity of care

The importance of continuity in the care process was highlighted. Organisations strived to ensure care provision by the same person throughout the treatment process. Thereby, care providers were assumed to be better able to familiarise with the specific patient, observe and address health state changes. Temporary employment in case of understaffing was regarded as a hindrance to the provision of continuous care and therefore to PCC, since these employees are usually not familiar with the processes and structures in the particular care organisation. Moreover, in case of readmission, retreatment or follow-up visits, the opportunity to contact the same HSCOs as previously was considered desirable. The use of guides (eg, a case manager) was mentioned as a strategy to ensure continuity.

Timeliness of care

Next to continuity, the timeliness of care was stressed as important for PCC. Timeliness means that a patient’s access to treatments matches the urgency of that patient’s physical or psychological needs. In order to be able to assess the urgency of a situation, according to the interviewees, this requires guidelines and skills (eg, to recognise such situations or capacity to act) of those who have the first contact with the patient (eg, reception staff). The extent of bureaucracy proved to influence timeliness of treatment, including, for example, approval and reimbursement of therapies, the purchase of special home care equipment and anamnesis of non-relevant information for care needs.

Flexibility of care

In any care situation, the flexibility of care was considered necessary for delivering PCC implying that processes and individuals allow for adjustments in care that value a patient’s day-to-day needs and preferences. This may include, for example, altering standardised care plans when patients prefer to shower on a different day. However, interviewees also reported a lack of flexibility in structures and processes, especially in hospitals. If regular processes and responsibilities are maintained in emergency cases, although immediate action including deviation from the usual procedures is required, this might threaten the patient’s health.

Internal communication and networking

Communication processes were separated into formal communication or informal communication. Formal communication covered regular events, such as case meetings, team meetings or tumour boards. Interviewees described the involvement of various disciplines in formal cooperation, sometimes depending on the specific patient’s needs and background, as ways to ensure PCC. The integration of different knowledge bases for medical treatment decisions and the involvement of additional non-medical (eg, social-service) perspectives in the care process were described as advantages of formal cooperation structures.

Informal communication channels were mentioned as a complementary, yet faster, way to network and cooperate internally. Possibilities for internal communication were sometimes described by providers of inpatient care as restricted when hierarchies, demarcated departmental structures or activities, and professional boundaries (eg, between nurses and physicians) existed.

Culture and climate

Decision makers described the communication and mutual consideration within an organisation as a key determinant for a good atmosphere for patients and staff members. Interviewees stated that with the help of good cooperation and a good working atmosphere, all employees are able to follow a patient-oriented attitude and action without the need for specific hierarchies, strategies or training.

Fostering an active collaborative culture within neighbourhoods and with other HSCOs was also mentioned as a strategy to improve patient care. Decision makers considered non-profit HSCOs better able to work in the interest of the patient since making profit does not need to be balanced against patient needs. Also, decision makers named specific guiding principles, usually with a religious origin, which shape their organisation’s culture. The implementation of these principles was assumed to be supported, for example, by signing a mission statement form or having an inspiring leader who actively represents the culture and values of the organisation.

Determinants of PCC implementation related to the individual level: characteristics of individuals

Coping strategies

Finding a position in which employees are able to provide care according to their qualification and beliefs was considered necessary for being able to cope with the challenging task of providing care. Interviewees named the attendance of mentoring meetings, exchange with colleagues or the development of joint practices as opportunities to better cope with challenging situations. In very problematic situations related to personal conflicts with patients, interviewees considered referral to another care provider as necessary.

Physical and emotional well-being

Interviewees described a direct link between the physical and emotional well-being of caregivers and the provision of PCC, since only those employees who experience well-being can also provide good care in the long run. Moreover, employees who experience well-being in a care organisation were considered more likely to remain employed for a longer time and therefore support the provision of continuous care (see: Continuity of care). Interviewees considered a reduction of working hours or job-sharing strategies to leave room for sufficient recovery from the demanding task of care provision.

Skills and capabilities

Interviewees mentioned psychological traits, professional qualifications and development, and communication skills as important factors at the individual level to determine the provision of PCC. Staff members who are motivated, empathic, respectful, patient, open, flexible, active listeners and who have good problem-solving skills were considered to be better able to provide PCC than those lacking these traits. Moreover, orientation towards the patient is supported when care provider and patient get along well with each other. Interviewees highlighted the importance of looking at psychological traits when recruiting new staff members in order to create a functioning team. Additionally, sufficient qualification and willingness of staff members for professional development was considered a prerequisite for PCC provision. Being able to communicate in the patients’ mother tongue was considered as relevant as the educational background of the care provider. A high level of, for example, registered nurses instead of nursing assistants, facilitates care coordination since each staff member can take over all tasks. Staff members who are trained for the treatment of particular patient groups (eg, breast cancer, dementia and palliative care) can take over more specialised tasks and relieve general nurses from several duties. Communication skills including withstanding difficult and unpleasant conversations were considered particularly important competences. Having a plan in mind for communicating bad news, such as diagnoses, and being honest were both considered necessary for managing such situations without overwhelming patients. Interviewees stated that the best medical care could even be endangered if it was not accompanied by adequate communication and easily understandable explanation of the disease and treatment process.

Attitudes towards PCC

Interviewees stated that PCC largely depends on the employee’s engagement and feeling of responsibility for care. Intrinsically motivated staff had a feeling of responsibility and compensated for disruptions during the care process. Care providers need to have a positive attitude towards the patient, but this should also be supported by the care team and supervisors, for example, by acting as role models, placing high value on patient-centred behaviours during employment probation or allowing enough time for the care of each patient.

Discussion

Providers of health and social care services face increasing pressure to implement PCC into their daily practice. This study explored potential determinants that facilitate or obstruct PCC implementation and strategies to reconcile PCC with resource scarcity. The determinants of PCC in the inner setting of HSCOs and at the individual level are influenced by factors at the outer setting (system level) in the provision of PCC. These interactions are addressed in the discussion of the results, although the results on the determinants at the outer setting and their influences on PCC are not presented in this article. When describing optimal care for patients, the interviewees usually addressed all core elements of PCC, as described in established concepts on PCC,3 reflecting a general agreement regarding the dimensions of PCC (see online supplementary appendix 1).

So far, no structures or incentive systems for organisations and providers exist on a national level in Germany to implement PCC. A few initiatives have been launched, such as training programmes on shared decision making as part of healthcare professional education.30 However, our preliminary results on the analysis of PCC determinants at the system level so far indicate that such training programmes are not sufficient. Rather, HSCOs and providers need to manage the implementation of PCC themselves. Therefore, the discussion of organisational strategies for implementing PCC is becoming particularly important. Interviewees described organisations’ strategies towards maintaining, accumulating and preserving their resources as they perceived difficulties in striking the right balance between PCC, quality demands, scarce resources and rigid guidelines. Indications of the interviewees regarding the challenges at the system level (outer setting) emphasise that financing conditions such as contribution rate stability, the separation between revenues from statutory or private health insurance or an avoidance of financial responsibility at the system level hinder organisations from meeting the needs of a growing number of patients with an increased need for care. As a result, HSCOs are hindered from investing in health innovations in order to ensure care that is in line with healthcare advancements. Human resources were therefore perceived as the most important resources because they are linked to other resources (eg, time or money) and can be influenced by the organisation. Fostering personnel qualifications and development as well as the concept of care for caregivers18 were therefore identified as main strategies to preserve different kinds of resources (personnel, financial and time) to support PCC. All interviewees stated that only healthy and satisfied caregivers are able to provide PCC on an ongoing basis. This corresponds to the finding that patient satisfaction is lower in hospitals with more burned-out, dissatisfied and frustrated nursing staff.31 Accordingly, strategies to maintain or improve the emotional and physical well-being of staff were described across different types of organisations. While individuals need to be qualified for their job, it is the organisations’ task to foster staff well-being and provide sufficient opportunities for continuous education.16

Individual characteristics that determined the provision of PCC, for example, empathy or the individual attitudes towards the uniqueness of patients and their needs, can only partly be influenced directly by the organisations. In line with this, the recruitment of adequate staff was highlighted as a main challenge by decision makers. Another important determinant for PCC at the individual level was the professional expertise of the employees. Our preliminary results on the analysis of determinants from the outer setting point out that decision makers wished for a more academic education of health professionals that, however, has not yet been integrated into current legal reforms. It was generally perceived as difficult to recruit staff with both professional expertise and soft skills. Soft skills such as empathy were also not learnt through previous educational structures. Instead, the organisations try to convey these skills through the culture of the organisation or through the example of leadership.

On the organisational level, the general commitment towards PCC with an emphasis on leadership behaviour and support as well as an organisational culture of learning emerged as key determinants for PCC implementation (eg, refs 14 16 19 20). These aspects closely relate to other determinants, since our interviews suggested that patient-oriented behaviour needs to be valued, rewarded or, if not achieved, reacted to appropriately by organisational leaders. Another key facilitator that emerged was continuity of patient care within and across organisations, which is consistent with previous work on PCC (eg, refs 21 32 33). While continuity in appointments or in people providing care cannot always be ensured due to work schedules, IT infrastructure was considered as one option to reduce problems with fragmented care. A complete and fast exchange of patient information should facilitate care within and across organisations, since a complete personal and disease history is available and does not need to be elicited at each new visit. Policy makers should therefore discuss more intensively opportunities of improved IT structures in HSCOs.1

According to some decision makers, especially in inpatient care, an external incentive for PCC would be to compete with other HSCOs. This perceived peer pressure, a PCC determinant in the outer setting, encourages HSCOs to develop strategies for more PCC. They spend extra resources and offer add-on services that enable PCC as consequence of the peer pressure effects and a lack of sufficient reimbursement by the healthcare system.

The definition of standardised processes (internal, eg, standard operating procedures) and care procedures (external, eg, clinical practice guidelines) was considered important in order to effectively control processes and to provide care adherent to standards of care. However, interviewees stated that guidelines would only give orientation and processes and standards must be flexibly adaptable to the individual needs of patients. An individualised standardisation within HSCOs can therefore be concluded as a yardstick for PCC.34 35

As a strategy to increase patient value in care with equal resource consumption36 and to organise care around the patient,37 it was proposed to concentrate care within the HSCOs. This corresponds to Christensen et al’s38 idea to reorganise HSCOs towards types of organisations related to the complexity of the patient’s problem of care. For example, in the case of hospitals, they suggest that managerial control could be regained if general hospitals were replaced by two types of organisations. One type, called a ‘value-adding process clinic’, delivers standardised, routine treatments for patients with well-diagnosed conditions at predictably high quality. The other type, called a ‘solution shop’, organises care for more complex and ill-diagnosed patients.38

Limitations

Our results need to be seen in light of several limitations of this study. First, interviews were only conducted with decision makers in leading positions. The perspective of staff members in lower positions was not considered. Therefore, any differences in perspective cannot be identified through this study. However, people in lower positions would not have provided us with information about management-related, personnel-related or resource-related information and strategies in the organisation, which was also an aim of this study. Second, we only included representatives in the city of Cologne, which implies that we did not capture PCC determinants related to more rural areas. Third, our sample might suffer from selection bias. We assume that participants had a higher intrinsic motivation and interest in the particular research topic and might also be more likely to engage in activities that foster PCC. Finally, the understanding of PCC, its implementation in organisations and associated determinants often depend on individual definitions and the context of care. It requires an in-depth analysis to find commonalities and refined understandings of higher order meanings. However, the aim of this study was to provide an overview of determinants of PCC implementation considering various contexts. To complement our findings, additional analyses focusing on determinants of PCC in the outer setting will be published separately.

To conclude, as reflected by the wide range of determinants identified, PCC implementation requires performance measures that evaluate multiple dimensions.39 Some of those dimensions may be influenced by short-acting strategies (eg, equipment; design of rooms and buildings), while others require certain midterm or long-term strategies (eg, building networks or a culture). One particular pillar for the success of PCC seems to be the active involvement and engagement of management and decision makers. These persons are particularly positioned to relay the high importance for PCC,18 thereby supporting an atmosphere that values PCC6 and implementation efforts.20

Future research should investigate whether the identified determinants are similar in other regions, especially rural areas. Moreover, quantitative data on systematic differences between types or ownership of HSCOs are needed to validate the explorations of this work. Finally, future research should apply a more fine-grained view on conditions and regulations of the health and social care system, such as reimbursement regulations, and their association with PCC implementation.10 These determinants are located outside the sphere of individuals or organisations and may provide policy implications to foster PCC implementation in organisations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the participating decision makers for their contribution to the project. We could not have done it without you. We gratefully acknowledge the support and cooperation within the CoRe-Net research group.

Footnotes

Contributors: All members designed the study. KIH, HAH and VV designed and conducted data collection, critically reviewed by LA. KIH drafted and revised the paper in close collaboration with VV and HAH. KIH is guarantor. LA, SS, LK and HP critically revised the paper.

Funding: This work was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (grant no. 01GY1606).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the University of Cologne approved the study (reference number: 17–210).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Collaborators: Christian Albus, Lena Ansmann, Frank Jessen, Ute Karbach, Ludwig Kuntz, Holger Pfaff, Christian Rietz, Ingrid Schubert, Frank Schulz-Nieswandt, Stephanie Stock, Julia Strupp, Raymond Voltz, Nadine Scholten.

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published online. The Collaborator group and Trial Registration number have been added.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Washington(DC): Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, et al. Improving chronic illness care: translating evidence into action. Health Aff 2001;20:64–78. 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Scholl I, Zill JM, Härter M, et al. An integrative model of patient-centeredness - a systematic review and concept analysis. PLoS One 2014;9:e107828 10.1371/journal.pone.0107828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kitson A, Marshall A, Bassett K, et al. What are the core elements of patient-centred care? A narrative review and synthesis of the literature from health policy, medicine and nursing. J Adv Nurs 2013;69:4–15. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.06064.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mead N, Bower P. Patient-centredness: a conceptual framework and review of the empirical literature. Soc Sci Med 2000;51:1087–110. 10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00098-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fix GM, VanDeusen Lukas C, Bolton RE, et al. Patient-centred care is a way of doing things: how healthcare employees conceptualize patient-centred care. Health Expect 2018;21:300–7. 10.1111/hex.12615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ 2001;323:908–11. 10.1136/bmj.323.7318.908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 2013;70:351–79. 10.1177/1077558712465774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Matthews EB, Stanhope V, Choy-Brown M, et al. Do providers know what they do not know? A correlational study of knowledge acquisition and person-centered care. Community Ment Health J 2018;54:514–20. 10.1007/s10597-017-0216-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization. People-centred health care: a policy framework: World Health Organization, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ansmann L, Hillen HA, Kuntz L, et al. Characteristics of value-based health and social care from organisations' perspectives (OrgValue): a mixed-methods study protocol. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022635 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022635 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World Health Organization. Global strategy on human resources for health: workforce 2030: World Health Organization, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 13. West E, Barron DN, Reeves R. Overcoming the barriers to patient-centred care: time, tools and training. J Clin Nurs 2005;14:435–43. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Taylor A, Groene O. European hospital managers' perceptions of patient-centred care. J Health Organ Manag 2015;29:711–28. 10.1108/JHOM-11-2013-0261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Charlton CR, Dearing KS, Berry JA, et al. Nurse practitioners' communication styles and their impact on patient outcomes: an integrated literature review. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2008;20:382–8. 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00336.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patel V, Buchanan H, Hui M, et al. How do specialist trainee doctors acquire skills to practice patient-centred care? A qualitative exploration. BMJ Open 2018;8:e022054 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gluyas H. Patient-centred care: improving healthcare outcomes. Nurs Stand 2015;30:50–9. 10.7748/ns.30.4.50.e10186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Shaller D. Patient-centered care: what does it take? New York 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Moore L, Britten N, Lydahl D, et al. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of person-centred care in different healthcare contexts. Scand J Caring Sci 2017;31:662–73. 10.1111/scs.12376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rosemond CA, Hanson LC, Ennett ST, et al. Implementing person-centered care in nursing homes. Health Care Manage Rev 2012;37:257–66. 10.1097/HMR.0b013e318235ed17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Santana MJ, Manalili K, Jolley RJ, et al. How to practice person-centred care: A conceptual framework. Health Expect 2018;21:429–40. 10.1111/hex.12640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Luxford K, Safran DG, Delbanco T. Promoting patient-centered care: a qualitative study of facilitators and barriers in healthcare organizations with a reputation for improving the patient experience. Int J Qual Health Care 2011;23:510–5. 10.1093/intqhc/mzr024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. The German health care system. Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). Health care in Germany: The German health care system, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci 2009;4:50 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Karbach U, Ansmann L, Scholten N, et al. Bericht aus einem laufenden forschungsprojekt: coRe-Net, das Kölner kompetenznetzwerk aus versorgungspraxis und versorgungsforschung, und der value-based healthcare-ansatz. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen 2018;130:21–6. 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rousseau DM. Assessing organizational culture: The case of multiple methods Schneider B, edn Organizational climate and culture. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1990:153–92. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Poggie J. Toward quality control in key informant data. Hum Organ 1972;31:23–30. 10.17730/humo.31.1.6k6346820382578r [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Marshall MN. The key informant technique. Fam Pract 1996;13:92–7. 10.1093/fampra/13.1.92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications, Inc, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Härter M, Dirmaier J, Scholl I, et al. The long way of implementing patient-centered care and shared decision making in Germany. Z Evid Fortbild Qual Gesundhwes 2017;123-124:46–51. 10.1016/j.zefq.2017.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McHugh MD, Kutney-Lee A, Cimiotti JP, et al. Nurses' widespread job dissatisfaction, burnout, and frustration with health benefits signal problems for patient care. Health Aff 2011;30:202–10. 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Greene SM, Tuzzio L, Cherkin D. A framework for making patient-centered care front and center. Perm J 2012;16:49–53. 10.7812/TPP/12-025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Zill JM, Scholl I, Härter M, et al. Which dimensions of patient-centeredness matter? - Results of a web-based expert delphi survey. PLoS One 2015;10:e0141978 10.1371/journal.pone.0141978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ansmann L, Pfaff H. Providers and patients caught between standardization and individualization: individualized standardization as a solution comment on "(Re) making the procrustean bed? standardization and customization as competing logics in healthcare". Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;7:349–52. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mannion R, Exworthy M. (Re) Making the procrustean bed? Standardization and customization as competing logics in healthcare. Int J Health Policy Manag 2017;6:301–4. 10.15171/ijhpm.2017.35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]