Abstract

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) remains one of the most common chronic diseases of adulthood which creates high degrees of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The incidence of T2DM continues to rise and recently, mHealth interventions have been increasingly used in the prevention, monitoring and management of T2DM. The aim of this study is to systematically review the published evidence on cost and cost-effectiveness of mHealth interventions for T2DM, as well as assess the quality of reporting of the evidence.

Methods and analysis

A comprehensive review of PubMed, EMBASE, Science Direct and Web of Science of articles published until January 2019 will be conducted. Included studies will be partial or full economic evaluations which provide cost or cost-effectiveness results for mHealth interventions targeting individuals diagnosed with, or at risk of, T2DM. The quality of reporting evidence will be assessed using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist. Results will be presented using a flowchart following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines. Graphical and tabulated representations of the results will be created for both descriptive and numerical results. The cost and cost-effectiveness values will be presented as reported by the original studies as well as converted into international dollars to allow comparability. As we are predicting heterogenous results, we will conduct a narrative and interpretive analysis of the data.

Ethics and dissemination

No formal approval or review of ethics is required for this systematic review as it will involve the collection and analysis of secondary data. This protocol follows the current PRISMA-P guidelines. The review will provide information on the cost and cost-effectiveness of mHealth interventions targeting T2DM. These results will be disseminated through publication and submission to conferences for presentations and posters.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42019123476

Keywords: general diabetes, health economics, telemedicine

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This review will address a gap in the literature regarding the cost and cost-effectiveness of mHealth interventions for individuals with or at risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus.

The protocol follows the latest Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols guidelines and we will use a Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards checklist to assess the quality of reporting evidence by the included studies.

The validity and quality of the results will depend on the quality of the identified studies.

The heterogenicity of the identified studies may complicate the narrative analysis of the results.

Introduction

Description of the condition

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a chronic disease where the patient becomes progressively resistant to insulin causing a tendency to develop high blood sugars and symptomatic cardiovascular disease.1 In poorly controlled patients, diabetes can cause a substantial number of morbidity and mortality due to cardiovascular, ocular and nephrogenic complications.2 The prevalence of diabetes is increasing with 425 million adults thought to be living with the condition in 2018, that is, around 8.5% of the adult population.1 3 In 2015, diabetes was the sixth highest cause for disability worldwide.4 The loss of productivity due to diabetes and its health consequences causes an economic burden to patients, healthcare providers and country’s economy, mounting to 1.8% of the global gross domestic product (GDP) and 12% of the global health expenditure in 2018.3 5 Moreover, more than 80% of yearly deaths due to diabetes occur in developing countries where the economic consequences are greater than in developed counterparts.6

The prevention and management of the diabetes consists of lifestyle modifications (including weight, exercise and nutritional changes) and, if unsuccessful, the pharmacological control of hyperglycaemia.7 For many patients, the diagnosis and management of the condition challenges their lifestyle habits including exercise and diet. Therefore, many patients still demonstrate low willingness to change their unhealthy lifestyle habits.8 9 To overcome these barriers, technology has demonstrated encouraging potential in supporting patients’ behavioural changes by providing an empowering, portable every-day reminder of their diabetes management plan.10

Description of the intervention

It is estimated that 96.8% of adults worldwide have access to a mobile phone, while, 43.4% of individuals are using the internet,11 this increases to 94.4% if solely describing high-income countries.12 The large growth of wireless connection has created a platform for technology-based opportunities in healthcare combining patient empowerment with the convenience of mobile devices. mHealth can be defined as the integration of mobile devices, personal digital assistants and other technological wireless systems to improve the health of individuals.13 Importantly, it can help to equilibrate the disparities in healthcare access and quality by diminishing barriers for patients to access healthcare advice and monitoring.14 The use of mHealth has increased exponentially throughout the last two decades with early research consisting mostly of small pilot studies, while, current research is increasingly structured and evidence based.15 16

Diabetes and mHealth

Studies evaluating the clinical effectiveness of mHealth interventions targeting diabetes have demonstrated clinical usefulness in the prevention and control of diabetes utilising lifestyle modification and blood glucose monitoring applications.17–19 A meta-analysis review demonstrated that there is a statistically significant reduction in blood glucose levels among patients using mobile phone interventions.20 Additionally, a systematic review found that glycaemic control results are amplified when two different methods are used in conjunction with one another, such as text reminders and blood glucose record keeping.21 mHealth interventions have been shown to be low cost and cost-effective across medical specialties, such as cardiovascular and renal medicine, however, there are significant gaps in the economic literature addressing mHealth interventions targeted at individuals with or at risk of T2DM.14

Why do this review?

mHealth for diabetes shows clinical promise, however, there is a lack of cost and cost-effectiveness evidence in regard to mHealth interventions. A systematic review evaluating the cost and cost-effectiveness of mHealth interventions targeting T2DM is required to close a gap in the literature.

Aim

The aim of this study is to systematically review the published evidence on the cost and cost-effectiveness of mHealth interventions for T2DM.

Specific objectives

To identify and summarise the cost and cost-effectiveness evidence for mHealth interventions targeting T2DM.

To evaluate the quality of reporting of the evidence.

To identify the main drivers of the cost and cost-effectiveness results among these interventions.

Methods

Types of studies

All partial and full economic evaluation studies presenting data for mHealth interventions directed at patients diagnosed or at risk of T2DM will be included. Partial economic evaluations are defined as evaluations that provide the cost of the intervention but do not, however, compare the costs with an alternative intervention or to the outcomes of the intervention.22 All studies that report cost of the intervention, either from provider (eg, design and implementation costs), patients (eg, subscription fee, cost of changing behaviour) or societal perspectives, will be included in the review. Full economic evaluations compare the costs of the intervention with one or more alternative interventions (ie, comparators) and relate these to the outcomes. Full economic evaluations include cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), cost-utility analysis (CUA), cost–benefit analysis (CBA), cost-minimisation analysis and cost-consequence analysis.22

Types of participants

Included mHealth interventions will be targeted at individuals who are diagnosed with or are at risk of developing T2DM due to impaired glucose tolerance. This review will include mHealth interventions implemented in both low- and middle- and high-income settings.

Types of interventions

All mHealth interventions targeting patients at risk of or with diagnosed T2DM that involve the use of the internet, mobile devices or computer-based interventions will be included in the review. We recognise that mHealth is a vast subject area and, therefore, we will attempt to categorise included mHealth interventions into relevant subgroups to facilitate comparability.

Outcome measures

The common outcome measures such as incremental cost-effectiveness ratios, average cost-effectiveness ratio, benefit–cost ratio and unit costs will be extracted from the selected studies. We will report outcome measures as presented in the original studies and, for comparison, we will convert the original values to 2017 international dollars using purchasing power parity for the country where the study is conducted.

Exclusion criteria

Studies will be excluded from our analysis if they are:

Not published in a peer reviewed journal.

Not available in the English language.

Not addressing mHealth based interventions.

Not reporting any cost or cost-effectiveness data on the interventions.

Locating studies

Electronic searches

We will conduct a literature search on the following online databases from inception to end of January 2019 for studies published in English on:

MEDLINE (PubMed).

EMBASE.

Web of Science.

Science Direct.

Other searches

We will additionally review the reference lists of identified studies for any further relevant studies.

Search strategy

We will use the search strategy with the key words specified in box 1 for all four online databases. We will modify the search strategy to suit all four databases.

Box 1. Search strategy key words.

((((((((((m-health) OR ehealth) OR mhealth) OR MeSH) OR mobile health) OR telemedicine) OR e-health) OR application) OR app) OR electronic health)).

AND (((((((((diabetes) OR Type 2 Diabetes) OR Diabetes Mellitus) OR T2DM) OR DM2) OR impaired glucose tolerance) OR insulin resistance) OR pre-diabet*) OR impaired fasting tolerance).

AND (((((((((((cost effectiv*) OR cost-effetiv*) OR cost benefit) OR cost-benefit) OR cost-utility) OR cost utility) OR cost analysis) OR cost-analysis) OR economic evaluation) OR cost*) OR cost outcome)).

AND ((((((((((((((monitor*) OR control*) OR management) OR prevention) OR risk reduction) OR lifestyle modification) OR exercis*) OR physical fitness) OR bariatric surgery) OR metformin) OR diet) OR weight loss) OR food) OR obesity) OR BMI.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

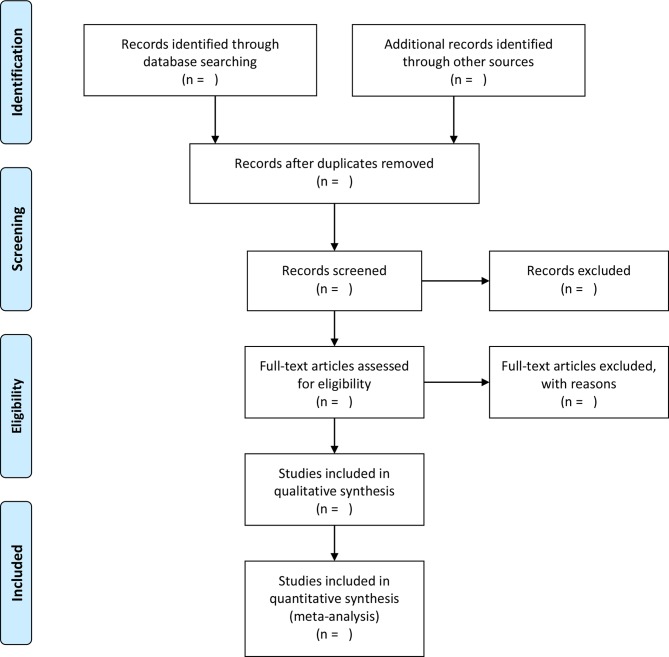

Relevant papers will be selected in two steps: in the first step, two authors (GR and AH) will independently review the titles and abstracts of the studies resulting from the above search and, in the second step, the full text of the selected papers in the first step will be screened. The search will be managed in Endnote X7 to facilitate the organisation and management of the selection process. Any disagreements among the authors will be discussed until an agreement is reached with consultation of another experienced author (HH-B). The outline of the study selection procedure will be shown in a preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocol (PRISMA-P) flowchart (figure 1).23 After the consensus on the final studies for inclusion, the authors will analyse the full publications data extraction.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols flowchart of the study selection process.

Data extraction

General information and economic features will be collected from all the selected studies including date of publication, study design, type of intervention (ie, type of mHealth), objective of the intervention, duration of the intervention, setting of the intervention (ie, based on income level and geographical region), platform of the intervention and demographics of the participants. Furthermore, economic evaluation details such as type of analysis (ie, CEA, CUA, CBA and so on), perspective of analysis, type of outcome measured, time horizon, type of data used (primary, secondary or mixed), type of sensitivity analysis and measures of uncertainty will be recorded. These data will be recorded and extracted using a data extraction tool designed for this purposed (online additional file 1) based on existing guidelines and other economic evaluation articles.22 24 25

bmjopen-2018-027490supp001.pdf (53.3KB, pdf)

In addition, we will evaluate the main drivers of the costs and cost-effectiveness results based on the findings from sensitivity analyses conducted by the included studies.

Quality of reporting evidence

We will assess the quality of reporting the economic evidence presented in the selected full economic evaluation studies using the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist.26 For partial economic evaluations, we developed a tool using the relevant criteria in the CHEERS checklist, some modified and the tools used by previous researchers.27 Two authors (GR and AH) will use these checklists independently and any discrepancies will be discussed among them until a consensus is reached. If discrepancies continue then third author (HH-B) will be involved to resolve these. The CHEERS checklist includes 24 items which are divided into five subheadings: title and abstract, introduction, methods, results and discussion (online additional file 2). The checklist for partial economic evaluations or costing studies is a 16-item checklist with similar subheadings as the CHEERS (online additional file 3). The quality of reporting of the included papers will be presented using the checklists in both table and graph format to ensure a numerical and visual representation of the quality limitations of the studies.

bmjopen-2018-027490supp002.pdf (77.7KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

As this is a protocol for a systematic review, we did not have patient or public involvement throughout the design, recruitment and conduct of this protocol.

Analysis

Summarising results

Results will be summarised using appropriate tables and figures to ensure a complete and objective account of our findings. We will include a general summary table quantifying the main characteristics of the included studies such as study design (randomised control trial, before-after, modelling and so on), type of mHealth intervention, time horizon, country income setting and outcome measure used (refer to online additional file 1). A more detailed account of the outcome measures will be presented and categorised via mHealth intervention type allowing the subdivision and ranking of the cost and cost-effectiveness of different mHealth interventions. To facilitate comparability of the results across countries and years, costs will be converted to 2017 international dollars using purchasing power parity conversion factors for each study setting. To evaluate cost-effectiveness, results will also be compared against the WHO’s cost-effectiveness threshold,28 as well as, an alternative threshold by Woods et al’s,29 using the setting’s GDP per capita.

Addressing bias

We will critically analyse the results of our review for possible bias. Particularly, we are aware of publication bias; often published studies demonstrate positive results and research demonstrating negative results may be lacking.30 Additionally, we will exclude studies that are not available in the English language and which are not published in a peer-reviewed journal, therefore, we acknowledge the bias that this may introduce.

Subgroup analysis

If sufficient studies are included, we plan on carrying out analysis among subgroups. For example, one stratification method will be the subdivision of interventions by mHealth category, such as mobile phone applications or computer-based interventions. Second, subdividing the interventions according to their objective, for example, diabetes prevention versus diabetes control, may allow a greater generalisability of results. Other potential sub-analyses we may include is the evaluation of cost and cost-effectiveness results according to the study design (eg, randomised control trial, modelling), the countries’ income level (low, middle or high) or geographical region.

Discussion

Although there is some evidence on the effectiveness of mHealth interventions in non-communicable disease such as diabetes and cardiology, evidence on cost and cost-effectiveness evidence of these interventions is limited. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that will systematically review the cost and cost-effectiveness of mHealth interventions targeting T2DM. Where sufficient data are available, we will also conduct subgroup analyses and explore the main drivers of costs and cost-effectiveness results.

The limitations of our study regard the quality and the heterogeneity of the selected studies. To address these limitations, we will use the CHEERS checklist and a modified CHEERS checklist to evaluate the quality of the all the included cost-effectiveness and costing studies, respectively. We anticipate heterogeneous results and predict limited scope for a meta-analysis, therefore, we will perform a narrative analysis. To contextualise and compare the heterogeneous results, we will convert the results into 2017 international dollars. Another possible limitation of this study, is its susceptibility to publication and small sample biases, which, will be considered when interpreting the results.

Conclusion

This systematic review will provide evidence to close a significant gap in the literature addressing the costs and cost-effectiveness of mHealth interventions targeted at T2DM. Conclusions will be based on the results from both full and partial economic evaluations. Summarising the cost and cost-effectiveness of mHealth interventions will provide useful information for policy makers when designing and implementing these interventions.

Ethics and dissemination

No formal ethical review or approval is needed as there will be no primary collection of data involved in this review. The results of this review will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal for publication. The findings will also be shared at international conferences. This review will address the gap in the literature concentrating on the cost and cost-effectiveness of mHealth interventions for T2DM. We predict that this information will help to influence the decision-making surrounding mHealth interventions targeting people at risk of or diagnosed with T2DM.

bmjopen-2018-027490supp003.pdf (58KB, pdf)

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: GR and HH-B equally contributed in conception and design of the protocol and preparation of the first draft. GR developed the search strategy. GR and HH-B developed the data extraction and quality assessment tool for partial economic evaluation studies. AH reviewed and amended the draft of the protocol. GR, HH-B and AH all reviewed and approved of the final version of the manuscript submitted for publication.

Funding: This study was funded by UCL Institute for Global Health, University College London.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. WHO. Global Report on Diabetes. 2016.

- 2. Bhutani J, Bhutani S. Worldwide burden of diabetes. Indian J Endocrinol Metab 2014;18:868–70. 10.4103/2230-8210.141388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. International Diabetes Federation. International Diabetes Federation Atlas. 2017. http://www.diabetesatlas.org.

- 4. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1545–602. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang P, Gregg E. Global economic burden of diabetes and its implications. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2017;5:404–5. 10.1016/S2213-8587(17)30100-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Khuwaja AK, Khowaja LA, Cosgrove P. The economic costs of diabetes in developing countries: some concerns and recommendations. Diabetologia 2010;53:389–90. 10.1007/s00125-009-1581-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Olokoba AB, Obateru OA, Olokoba LB. Type 2 diabetes mellitus: a review of current trends. Oman Med J 2012;27:269–73. 10.5001/omj.2012.68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dellasega C, Gabbay R, Durdock K, et al. MI) to Change Type 2DM Self care behaviors: a nursing intervention. J diabetes Nurs 2010;14:112–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Linmans JJ, Knottnerus JA, Spigt M. How motivated are patients with type 2 diabetes to change their lifestyle? A survey among patients and healthcare professionals. Prim Care Diabetes 2015;9:439–45. 10.1016/j.pcd.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Istepanian RSH, Al-Anzi TM. m-Health interventions for diabetes remote monitoring and self management: clinical and compliance issues. Mhealth 2018;4:4 10.21037/mhealth.2018.01.02 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. ITU. ICU Facts and Figures the World in 2015. 2015.

- 12. ITU. ICT Facts and Figures 2017. 2017.

- 13. WHO. mHealth New Horizons for health through mobile technologies. 2011.

- 14. Iribarren SJ, Cato K, Falzon L, et al. What is the economic evidence for mHealth? A systematic review of economic evaluations of mHealth solutions. PLoS One 2017;12:e0170581 10.1371/journal.pone.0170581 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ali EE, Chew L, Yap KY-L. Evolution and current status of mhealth research: a systematic review. BMJ Innov 2016;2:33–40. 10.1136/bmjinnov-2015-000096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fiordelli M, Diviani N, Schulz PJ. Mapping mHealth research: a decade of evolution. J Med Internet Res 2013;15:e95 10.2196/jmir.2430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Klonoff DC. Diabetes and telemedicine: is the technology sound, effective, cost-effective, and practical? D.C. Klonoff, Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics, D. L./J. E. Frank Diabet. Res. Inst., Mills-Peninsula Health Services, 100 South San Mateo Dr., San Mateo, CA 94401, United States. E-mail: klonoff@compuserve.com, United States: American Diabetes Association Inc. (1701 North Beauregard St., Alexandria VA 22311, United States). 2003.

- 18. Wu Y, Yao X, Vespasiani G, et al. Mobile app-based interventions to support diabetes self-management: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials to identify functions associated with glycemic efficacy. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2017;5:e35 10.2196/mhealth.6522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Block G, Azar KM, Block TJ, et al. A fully automated diabetes prevention program, alive-PD: program design and randomized controlled trial protocol. JMIR Res Protoc 2015;4:4 10.2196/resprot.4046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liang X, Wang Q, Yang X, et al. Effect of mobile phone intervention for diabetes on glycaemic control: a meta-analysis. Diabet Med 2011;28:455–63. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2010.03180.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saffari M, Ghanizadeh G, Koenig HG. Health education via mobile text messaging for glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Prim Care Diabetes 2014;8:275–85. 10.1016/j.pcd.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Drummond MF, Sculpher MJ, Claxton K, et al. Methods for the Economic Evaluation of Health Care Programmes. 4th edn: Oxford University Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev 2015;4:1 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, et al. Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: Consensus on Health Economic Criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2005;21:240–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Haghparast-Bidgoli H, Kiadaliri AA, Skordis-Worrall J. Do economic evaluation studies inform effective healthcare resource allocation in Iran? A critical review of the literature. Cost Eff Resour Alloc 2014;12:15 10.1186/1478-7547-12-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Husereau D, Drummond M, Petrou S, et al. Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2013;29:117–22. 10.1017/S0266462313000160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Banke-Thomas A, Wilson-Jones M, Madaj B, et al. Economic evaluation of emergency obstetric care training: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:403 10.1186/s12884-017-1586-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. WHO. Making choices in health: WHO guide to cost-effectiveness analysis. 2003.

- 29. Woods B, Revill P, Sculpher M, et al. Country-level cost-effectiveness thresholds: initial estimates and the need for further research. Value Health 2016;19:929–35. 10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Easterbrook PJ, Berlin JA, Gopalan R, et al. Publication bias in clinical research. Lancet 1991;337:867–72. 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90201-Y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027490supp001.pdf (53.3KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-027490supp002.pdf (77.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-027490supp003.pdf (58KB, pdf)