Abstract

Objectives

The objective was to investigate trends in the incidence of recognized and suspected cases of occupational diseases in Finland from 1975 to 2013, including variations by industry – and describe and recognize factors affecting variations in incidence.

Design

A register study.

Setting

The data consisted of recognized and suspected cases of occupational diseases recorded in the Finnish Registry of Occupational Diseases (FROD) in 1975–2013.

Participants

Altogether 240 000 cases of suspected and recognized ODs were analysed.

Primary and secondary outcome measures

From the annual workforce statistics and FROD data, we calculated the incidence of ODs and suspected ODs per 10 000 employees. For time trends by industrial sector, we used a 5-year moving average and a Poisson regression analysis.

Results

Annual average rates of ODs have varied from year to year. The total number was 25.0/10 000 employees in 1975 and 20.1/10 000 employees in 2013. Screening campaigns and legislative changes have caused temporary increases. When the financial sector was the reference (1.0), the highest incidence rates according to industrial sector were in mining and quarrying (9.87; 95% CI 8.65 to 11.30), construction (9.11; 95% CI 9.98 to 10.43), manufacturing (9.04; 95% CI 7.93 to 10.36) and agriculture (8.78; 95% CI 7.69 to 10.06). There is a distinct decreasing trend from 2005 onwards: the average annual change in incidence was, for example, −9.2% in agriculture, −10.3% in transportation and −4.7% in construction. The average annual decline was greatest in upper limb strain injuries (−11.1%).

Conclusion

This study provides a useful overview of the status of ODs in Finland over several decades. These data are a valuable resource for determining which occupations are at an increased risk and where preventive actions should be targeted. It is important to study long-term trends in the statistics of ODs to see beyond the year-to-year fluctuations.

Keywords: statistical trend, occupational diseases register, register study

Strengths and limitations of this study.

National statistics on occupational diseases (ODs) and short follow-ups have been published; however, year-to-year fluctuations make it difficult to discover the real long-term trends. A follow-up of almost 40 years provides a useful overview of the status of ODs.

The Finnish surveillance system has been considered as comprehensive. Because the register is based on compensation system, the under-reporting is not a major problem.

Every physician is obligated to notify diagnosed and suspected cases of ODs, but not all physicians have training in occupational medicine, and may thus fail to connect diseases with working conditions.

This overview is a valuable resource for determining which occupations are at an increased risk and where preventive actions should be targeted.

A limitation of this study is that based on the data on the incidence of the ODs, we can only give suggestions for the factors behind the changes of trends.

Introduction

According to the WHO, an occupational disease (OD) is any disease contracted primarily as the result of an exposure to risk factors arising from work activity. Work-related diseases (WRDs) have multiple causes, and factors in the work environment may play a role, together with other risk factors, in the development or worsening of such diseases. ODs are an important part of WRDs. All WRDs indicate defects in working conditions or the working environment, but only ODs are reported, and their exact numbers are recorded in registries. The number of ODs can be considered an indicator of efficient preventive actions in the workplace.

The European Union’s (EU) occupational safety and health strategy for 2014–2020 emphasises the prevention of occupational and other WRDs.1 The Ministry of Social Affairs and Health in Finland has set a goal to reduce the number of ODs.2 The reliable statistical data collection of ODs is important to enable evidence-based policy-making. It is equally important to know the factors behind the numbers of ODs. Changes in the incidence of ODs reflect changes in the conditions and processes of workplaces, but also a greater awareness of health risks among workers, employers and physicians; improved investments by occupational health and safety (OSH) organisations; better education and national preventive campaigns; and changes in legislation. We need to have up-to-date data of ODs, and we must analyse the effects of working conditions, legislation and, for example, screening campaigns on ODs. Of course, given the wide range of influential factors, it is very difficult to differentiate the effect of each simultaneous factor on OD incidence.

An OD that entitles the sufferer to compensation in accordance with Finnish legislation is a disease caused by any physical factor, chemical substance or biological agent encountered in the course of work carried out under a contract of employment, in public service or office, or as an agricultural entrepreneur, as prescribed in the Occupational Accidents, Injuries and Diseases Act (459/2015) and the Governmental Decree on the Ordinance on Occupational Diseases (769/2016). The decree contains a list of physical, chemical and biological factors and the diseases that may be caused by these factors, which are mostly based on epidemiological or clinical evidence. This list is updated from time to time; for example, carpal tunnel syndrome (2003) and retroperitoneal fibrosis caused by asbestos (2015) were added to the list. The list is not exhaustive, however: factors or diseases not on the list can also be suspected and recognised as causing or being an OD if a causal relationship between the exposure and the disease can be proved in an individual case, as in many respiratory and skin allergies determined by provocation or skin tests, for example. The Finnish Register of Occupational Diseases (FROD) enables the follow-up of trends in the incidence of ODs from 1964 onwards.

The aim of this study was to investigate trends in the incidence of recognised and suspected cases of ODs in Finland from 1975 to 2013—including variations by industry—and to describe and recognise factors affecting variations in incidence.

Material and methods

The FROD kept by the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health (FIOH) was established in 1964, and it was consolidated as a research register by Finnish legislation in 1993. The objectives of the FROD are to serve as a source of statistics on ODs, and to promote research and preventive measures in occupational health. Insurance companies send information on ODs suspected or diagnosed by Finnish physicians to the Finnish Workers’ Compensation Centre (TVK). The FROD is compiled from information from the TVK and the Farmers’ Social Insurance Institution (Mela). According to the Act on the Supervision of Labour Protection (44/2006), physicians are obligated to report cases of ODs and work-related illnesses to the Regional State Administrative Agencies, which then send forward reports to the FIOH. Information from this source can be used to augment and improve data in the FROD.

The Register’s unit of observation is a filed claim of an OD, either recognised or suspected. Since 2005, the FROD has gathered cases recognised by insurance companies and those that remain as suspicions of ODs separately. Recognition means that the insurance company has received sufficient data and decided to officially recognise a person’s condition as an OD in accordance with Finnish legislation. A recorded case (of an OD or its suspicion) contains detailed information on the timing, the patient’s identification data (personal identity number, sex, age, occupation), information on the employer (field of industry, location of workplace), diagnosis and the causes (exposures) and severity of the disease. The FROD is described in more detail in the report ‘Occupational diseases in Finland in 2012’.3

The data for this study consisted of 240 000 recognised and suspected cases of ODs registered in the FROD between 1975 and 2013. The early years of the FROD (1964–1974) were excluded, as the number of cases on record was small. For our study, we extracted from the registry all cases and suspected cases of ODs and their registration year. We obtained the workforce data by field of industry from sources published by Statistics Finland.4 Over the years, the field of industry categories have undergone several changes. The results of the study are presented according to the latest classification system from 2008 (TOL 2008), which is identical with NACE Rev. 2.5

Statistical methods

The variables presented here are the disease category, industry and year of registration of the OD or its suspicion. Using annual workforce statistics and cases and suspected cases of ODs, we calculated the incidence of ODs and suspected ODs per 10 000 employees. For identifying longer term time trends, we used a 5-year moving average.

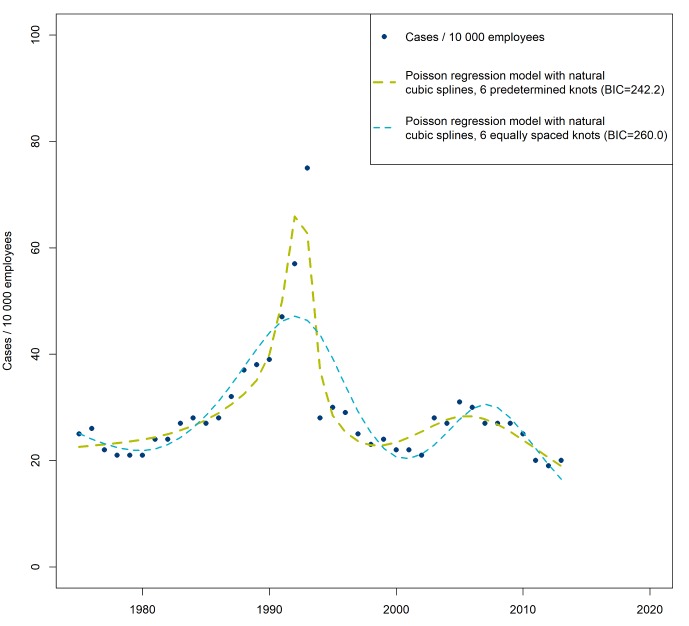

To model the incidence of OD trends between 1975 and 2013, we used a Poisson regression model with natural cubic splines using the splines package with the ns function in R statistical software.6 With the natural cubic spline, we were able to detect the peak in incidence that occurred in 1993. We evaluated two different models, one with equally spaced knots and one with six predetermined knots. We used the Bayesian information criterion to choose the best fitting model, which was the one with six predetermined knots (see figure 1). The rate ratios (RR) and the 95% CIs for the incidence of ODs for each industry were calculated using a Poisson regression model with cubic splines.

Figure 1.

Fitting the cases of occupational diseases (ODs) and suspected cases of ODs/10 000 employees for 1975–2013 in the Poisson regression model. BIC, Bayesian information criterion.

Patient and public involvement

We analysed register data and did not seek information from individuals. In other words, there was no patients or public involvement in the study.

Classification of ODs

In the statistics, ODs are classified into the following disease groups according to diagnosis and cause (for a detailed classification see Oksa et al 3).

Hearing loss

Noise-induced hearing loss refers to the deterioration of hearing due to prolonged exposure to noise or occasionally due to momentary impulse noise.

Repetitive strain injury of upper limbs

A repetitive strain injury is a musculoskeletal disease caused by non-physiological stress at work (repetitive and monotonous work, unusual working postures). The group includes tenosynovitis, peritendinitis, epicondylitis, bursitis and mononeuropathy (eg, carpal tunnel syndrome) of the upper limbs.

Allergic respiratory diseases

Allergic respiratory diseases include asthma, allergic rhinitis, allergic alveolitis and chronic laryngitis.

Skin diseases

Occupational skin diseases are caused by chemical agents or micro-organisms in the work environment; the most significant diseases in this group are irritant contact dermatitis and allergic contact dermatitis.

Asbestos-induced diseases

The group includes all ODs caused by asbestos—pleural plaques, adhesions and calcifications being the most frequent. Lung cancer and asbestosis are the most severe diseases in this group.

Others

The group includes, for example, infectious diseases, conjunctivitis, hand–arm vibration syndrome and various types of poisoning, including solvent-induced encephalopathy.

Results

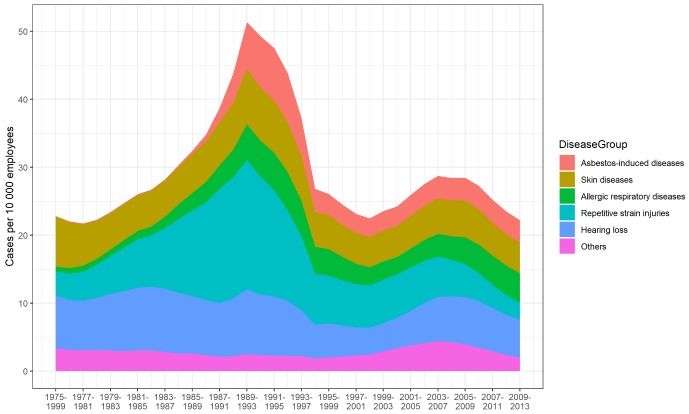

Altogether, 240 000 cases of suspected and recognised ODs were analysed. Annual average rates varied from year to year. The total number was 25.0/10 000 employees in 1975 and 20.1/10 000 employees in 2013. From 1975 to 2013, the Finnish workforce increased from 2.1 million to 2.6 million. Figure 2 presents the time trends of different disease groups from 1975 to 2014. The arrows indicate important incidents/events that have had an influence on incidence rates.

Figure 2.

Recognised and suspected occupational diseases in Finland. The 5-year moving average from 1975 to 2013.

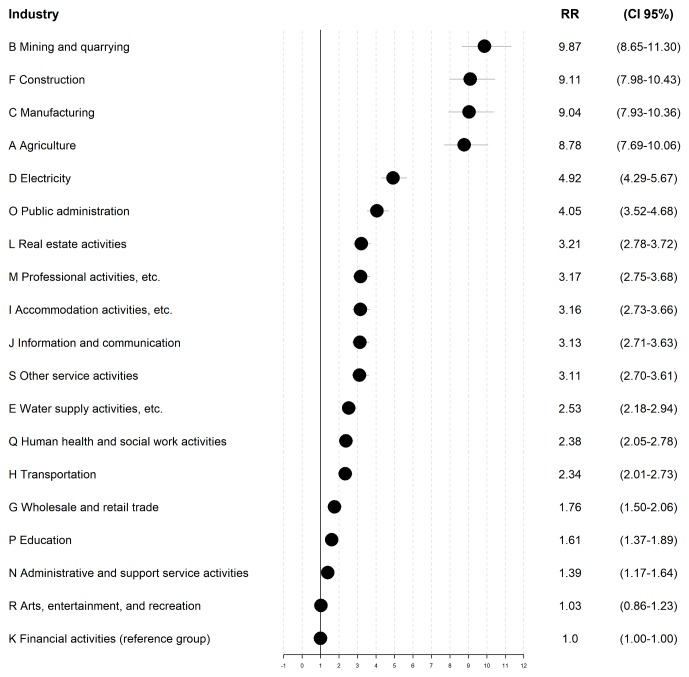

Figure 3 presents the RR of ODs in different fields of industry for 1975–2013. The highest RR was in mining and quarrying (9.87; 95% CI 8.65 to 11.30) and construction (9.11; 95% CI 7.98 to 10.43), when the reference group was financial and insurance activities (RR=1.00).

Figure 3.

Rate ratios of recognised and suspected occupational diseases by field of industry in Finland in 1975–2013. The reference group is financial and insurance activities (K), RR=1.00.

There is a distinct decreasing trend in ODs from 2005 onwards: the average annual change in incidence was, for example, −9.2% in agriculture, −10.3% in transportation and −4.7% in construction (see table 1).

Table 1.

Annual number and average incidence rate (95 % CI) per 10 000 employees, and average percentage change and 95% CI in incidence of occupational disease in Finland for 2015–2013 by field of industry

| Field of industry | Recognised ODs (2005–2013) | Suspected ODs (2005–2013) | ||

| Annual average incidence rate (95% CI) per 10 000 employees |

Annual average percentage change in incidence (95% CIs) | Annual average incidence rate (95% CI) per 10 000 employees |

Annual average percentage change in incidence (95% CIs) | |

| A Agriculture | 39.5 (30.8 to 48.1) | −9.2 (−10.2 to − 8.2) | 31.2 (24.5 to 37.9) | −9.8 (−11.0 to − 8.6) |

| B Mining | 35.4 (29.8 to 41.0) | −4.8 (−8.1 to − 1.5) | 22.2 (18.3 to 26.0) | −10.2 (−4.2 to − 16.1) |

| C Manufacturing | 26.0 (22.6 to 29.3) | −4.5 (−4.9 to − 4.1) | 24.6 (23.2 to 26.0) | −0.7 (−0.9 to − 0.5) |

| F Construction | 29.9 (26.4 to 33.3) | −4.7 (−5.4 to − 4.0) | 19.8 (17.6 to 22.0) | −0.3 (−0.5 to − 0.09) |

| Others | 7.0 (6.0 to 7.9) | −5.7 (−6.2 to − 5.2) | 9.6 (8.9 to 10.3) | −2.6 (−3.2 to − 2.0) |

| Total | 11.7 (9.8 to 13.6) | −6.7 (−7.0 to − 6.4) | 13.5 (12.5 to 14.6) | −2.8 (−3.0 to − 2.6) |

The annual incidence rate of all notified cases declined from 31/10 000 employees in 2005 to 20/10 000 employees in 2013. The reduction in the incidence rate of recognised ODs is more distinct than that of suspected cases: the annual incidence of recognised cases declined from 16/10 000 employees to 8/10 000 employees, while the annual incidence of suspected cases dropped from 16/10 000 employees to 12/10 000 employees. The average annual decline was greatest in upper limb strain injuries (−11.1%; see table 2).

Table 2.

Annual number and average incidence rate (95 % CI) per 10 000 employees, and percentage change and 95% CI of recognised and suspected occupational diseases in Finland for 2005–2013

| Occupational disease | Recognised ODs (2005–2013) | Suspected ODs (2005–2013) | ||||

| Number of cases | Annual average incidence rate (95% CI) per 10 000 employees | Annual average percentage change in incidence (95% CIs) | Number of cases | Annual average incidence rate (95% CI) per 10 000 employees |

Annual average percentage change in incidence (95% CIs) | |

| Hearing loss | 8299 | 4.0 (3.2 to 4.8) | −8.1 (−8.7 to − 7.5) | 4542 | 2.2 (2.0 to 2.4) | 1.2 (0.9 to 1.5) |

| Repetitive strain injuries | 3093 | 1.5 (1.1 to 1.9) | −11.1 (−12.2 to − 10.0) | 4648 | 2.2 (1.6 to 2.9) | −13.2 (−14.2 to − 12.2) |

| Allergic respiratory diseases | 1896 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | −7.8 (−9.0 to − 6.6) | 6556 | 3.1 (2.8 to 3.5) | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.2) |

| Skin diseases | 4295 | 2.1 (1.7 to 2.4) | −6.5 (−7.2 to − 5.8) | 5988 | 2.9 (2.7 to 3.0) | −0.1 (−0.2, to − 0.02) |

| Asbestos-induced diseases | 5330 | 2.5 (2.4 to 2.7) | −1.7 (−2.0 to − 1.4) | 1640 | 0.8 (0.7 to 0.9) | 0.0 (0 to 0) |

| Others | 1530 | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | −11.1 (−12.7 to − 9.5) | 4752 | 2.3 (1.6 to 2.9) | −7.9 (−8.7 to − 7.1) |

Discussion

Our results indicate that there has been a remarkable year-to-year fluctuation in the incidence of ODs due to various causes; the analysis of long-term trends is needed to understand the overall direction of the changes. In-depth analysis of the trends in different branches reveals the areas where more preventive efforts are needed.

1970s

The increase in the incidence of ODs in the 1970s coincided with the establishment of the six regional offices of the FIOH. The purpose of the regional offices was to support local workplaces and to educate OSH personnel. This became possible as the FIOH was granted judicial status in the 1970s and it started to receive annual funding from the state. The first act on FIOH action was passed in 1978 (159/1978).

Furthermore, the former voluntary occupational healthcare system became mandatory in Finland in 1978 (Act 743/1978). The increasing number of professionals in occupational healthcare is supposedly related to the increasing number of notifications of ODs, and thus the increasing incidence of ODs in the register. Gradually, over 3 years, all private and public organisations with at least one employee had to arrange occupational health services for their workers. Mandatory services included, for example, workplace surveys and medical health examinations for workers. The number of workers covered by occupational health services increased remarkably, from approximately 1.1 million in 1978 (60% of all employees) to 1.6 million (80%) in 1983, and to 1.9 million (87%) in 2013.7 In addition, the number of health examinations increased, revealing more ODs, which consequently resulted in the increase in the incidence of ODs.

1980s

Since 1978, farmers’ pension insurance has included mandatory accident insurance (MATA), which provides compensation for ODs caused by agricultural work. Guidelines for farmers’ occupational healthcare were provided to municipal health centres in 1984, and farm visits were fully compensated by the state (Act 859/1984). Several campaigns were launched to encourage farmers to use occupational healthcare services.

The Governmental Decree on the Ordinance on Occupational Diseases contains a list of physical, chemical and biological factors and the diseases caused by these factors. Updates to this list have resulted in the recognition of new ODs. A substantial increase in strain-related upper extremity musculoskeletal disorders was brought about by the changes in Decree 67/1987. With this decree, epicondylitis and tendinitis of the forearm became compensatory if the condition resulted from repetitive and one-sided movement or movement that was unfamiliar to the worker.

1990s

Screening for asbestos-induced diseases in Finland was carried out from 1990 to 1992 as part of the FIOH’s Asbestos Programme. Altogether, 18 900 employees were examined, and 3500 new asbestos-related ODs were diagnosed. Most of them were benign pleural changes/plaques, but there were also 800 cases of asbestosis. The number of asbestos-related diseases reported to the register multiplied for years after the campaign.8

The founding of a National Centre for Agricultural Health in 1999 was a further push to develop working conditions in farming and to encourage more farmers to use occupational healthcare.

2000s

From 2003, insurance institutions have sent data on new ODs and suspected ODs to the Workers’ Compensation Centre (TVK). The FROD obtains its information from the TVK and the Farmers’ Social Insurance Institution, Mela. Before 2003, insurance institutions sent data directly to the FROD. Information from Regional State Administrative Agencies (given by physicians) can be used to complete the data on diseases in the FROD.

In Finland, insurance companies pay for the examinations of both suspected and recognised ODs. The insurance institutions’ payment system changed in 2003, however; medical units could claim examination costs directly from insurance institutions. Prior to 2003, insurance companies paid yearly a sum of money to the state as compensation for the medical examinations of ODs conducted at municipal medical centres and hospitals.

In Finland, manufacturing, mining and quarrying, construction, agriculture, forestry and fishing have clearly had the highest incidence rates of ODs over the decades, although there has been a decreasing trend since 2005. They are all branches involving manual, physically demanding work, and several possible occupational exposures are common. Construction work is a good example, because it includes various health hazards, such as exposure to physical stress, dust, noise and vibration. Construction workers have been shown to be at an increased risk of work-related ill health and injury both in Europe and globally.9 They have an increased risk of cancer, respiratory diseases, musculoskeletal disorders and injuries compared with the general population.10 The incidence of skin neoplasia, contact dermatitis, musculoskeletal disorders, mesothelioma, lung cancer, pneumoconiosis and other benign pleural diseases is also increased among construction workers compared with the rest of the working population.11 The trends of ODs in the construction sector are not decreasing everywhere: significantly increasing trends in noise-induced hearing loss and work-related contact dermatitis were observed in the construction sector in the Netherlands in 2010–2014.12 An examination of trends and patterns in occupational illnesses among construction workers from 1992 to 2014 in the USA showed that construction workers continue to face a higher risk of work-related musculoskeletal disorders.13

The Finnish surveillance system has been considered comprehensive. In an evaluation of OD surveillance in six EU countries, FROD was rated as one of the best ones.14 Every physician is obligated to report diagnosed and suspected cases of ODs. FROD offers data on the incidence of ODs from 1964 onwards. Because the register is based on a compensation system, under-reporting is not a major problem. Nevertheless, some physicians may neglect to report ODs. Moreover, not all physicians are trained in occupational medicine, and some may thus fail to connect diseases with working conditions. For these reasons, some ODs may remain either undiagnosed or unrecorded. The period of interest was almost 40 years, so it impossible to take into account all variables, which have affected incidences of ODs. Some factors may be missing although we systematically have gone through all potential influential ones. The data are based on the numbers of ODs obtained from the insurance companies and they may contain some errors in classifications of diseases or occupations, which are not possible to correct afterwards. However, these are supposed to be rare exceptions in the large entity of data. No systematic information bias is likely, because the data of each year have been analysed and reported previously in annual reports. A limitation of this study is the fact that the data are mostly limited to the notifications of ODs to the insurance companies and thus they do not give a picture of all work-related diseases.

Registries and ODs differ considerably in various countries in terms of the criteria for registration and notification, statistical data provided and legal context.14 15 Therefore, figures on ODs are not necessarily comparable between countries. The ability to compare would be beneficial for improving occupational health policies and facilitating coordinated research. A comparison of OD surveillance systems in the EU countries has been recently published in order to facilitate this work in the future.16

The direct comparison of trends in OD within Europe showed that reports of contact dermatitis and asthma were declining in most countries, which is consistent with the positive impact of European initiatives addressing the relevant exposures.17 This finding is consistent with the results of the present study, although the largest decline we noted was in the numbers of upper limb musculoskeletal disorders.

The main reasons for the fluctuation of OD incidence rates in Finland include changes in legislation—such as the addition of new diseases to the list of ODs—screening campaigns and developments in technology and occupational safety and health.

The decline in the incidence of ODs in 2005–2013 has occurred at the same time as changes in fields of industry have continued. The number of workplaces in manufacturing has declined as the number of service workplaces has grown. Some 48.3% of men were employed in manual work in 2005; by 2013, the percentage had dropped to 45.5%. For women, the numbers were 22% and 17.5%, respectively.18 These changes influence the annual number and incidence rate of ODs (table 2), but the reduction is also true in most other fields of industry (table 1). Both the number of people leaving the workforce on disability pensions and the frequency of occupational accidents have decreased. The largest reduction was seen in 2006–2014, when the annual number of new disability pensions diminished by 26%.19 The total number of occupational accidents declined by 27% in 2006–2013.20 We assume that these three phenomena can be connected to the improvement of working conditions and activities of occupational health services.

There is evidence that technical improvements and innovations in processes may decrease the number of ODs. For example, passivating chromate by adding iron (II) sulfate to cement markedly reduced the allergic contact dermatitis incidence among construction workers.21 In addition, the end of the practice of using latex gloves resulted in a reduction in allergic contact dermatitis in healthcare workers.22 23 In the UK, a significant reduction in the incidence of short latency respiratory disease and asthma attributed to glutaraldehyde or latex coincided with changes in legislation, mandatory advice from the Medical Devices Agency, new exposure limits and the removal of glutaraldehyde-based disinfectants from the market.24 25

This study provides a useful overview of the status of ODs in Finland over several decades. These data are a valuable resource for determining which occupations are at an increased risk and where preventive actions should be targeted. It is important to study the long-term trends in the statistics of ODs to see the bigger picture beyond the year-to-year fluctuations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the many experts at the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health for their fruitful comments on this study. In particular, we wish to express our gratitude to our colleagues at the Finnish Register of Occupational Diseases, especially Lea Palo (long-term Research Secretary) and Ilpo Mäkinen for their proficiency in maintaining the high quality and reliability of the Registry.

Footnotes

Contributors: PO: primary investigator involved in the study design, study conduct and reporting. RS and JU: coprimary investigators involved in the study design, data collecting and reporting. NT and JN: coinvestigators involved in statistical planning, data processing and reporting. SV and AS: coinvestigators involved in planning, data collecting, data processing and reporting.

Funding: The Finnish Work Environment Fund funded the study (Project number 115142).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Information of published data from Finnish Registry of Occupational Diseases is available on website of Finnish Institute of Occupational Health. No unpublished data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. European Commission. Communication from the commission to the european parliament, the council, the european economic and social committee and the committee of regions on an EU strategic framework on health and safety at work 2014-2020. 2014. Brussels, 6.6.2014 COM 332 final.

- 2. Policies for the work environment and well-being at work until 2020. Publications of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. 2011:14.

- 3. Oksa P, Palo L, Saalo A, et al. Occupational diseases in Finland in 2012. New cases of recognized and suspected occupational diseases. FIOH Helsinki 2014:79. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Statistics Finland, Population 2005:4. [Suomen Virallinen Tilasto, Väestö 2005:4; Tilastokeskuksen PX-Web -tietojärjestelmästä, Työssäkäynti,”010 – Väestö alueen pääasiallisen toiminnan, sukupuolen, iän ja vuoden mukaan”]. http://pxnet2.stat.fi/PXWeb/pxweb/fi/StatFin/StatFin__vrm__tyokay/010_tyokay_tau_101.px/?rxid=e20431bb-9577-4ef1-9a1d-479c299dffe6 (accessed 1 Feb 2018).

- 5. NACE Rev.2 http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5902521/KS-RA-07-015-EN.PDF (accessed 1 Feb 2018)

- 6. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: http://www.R-project.org/. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Annual statistics. The Social Insurance Institution of Finland. Kela Statistics.

- 8. Koskinen K, Rinne JP, Zitting A, et al. Screening for asbestos-induced diseases in Finland. Am J Ind Med 1996;30:241–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Watterson A. Global construction health and safety-what works, what does not, and why?. Int J Occup Environ Health 2007;13:1–4. 10.1179/oeh.2007.13.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arndt V, Rothenbacher D, Daniel U, et al. Construction work and risk of occupational disability: a ten year follow up of 14,474 male workers. Occup Environ Med 2005;62:559–66. 10.1136/oem.2004.018135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stocks SJ, McNamee R, Carder M, et al. The incidence of medically reported work-related ill health in the UK construction industry. Occup Environ Med 2010;67:574–6. 10.1136/oem.2009.053595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van der Molen HF, de Vries SC, Stocks SJ, et al. Incidence rates of occupational diseases in the Dutch construction sector, 2010-2014. Occup Environ Med 2016;73:350–2. 10.1136/oemed-2015-103429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wang X, Dong XS, Choi SD, et al. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders among construction workers in the United States from 1992 to 2014. Occup Environ Med 2017;74:374–80. 10.1136/oemed-2016-103943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Spreeuwers D, de Boer AG, Verbeek JH, et al. Evaluation of occupational disease surveillance in six EU countries. Occup Med 2010;60:509–16. 10.1093/occmed/kqq133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. European Commission. Communication from the commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of Regions. Safer and Healthier Work for All - Modernisation of the EU Occupational Safety and Health Legislation and Policy. Brussels: COM(2017) 12 Final, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Carder M, Bensefa-Colas L, Mattioli S, et al. A review of occupational disease surveillance systems in Modernet countries. Occup Med 2015;65:615–25. 10.1093/occmed/kqv081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stocks SJ, McNamee R, van der Molen HF, et al. Trends in incidence of occupational asthma, contact dermatitis, noise-induced hearing loss, carpal tunnel syndrome and upper limb musculoskeletal disorders in European countries from 2000 to 2012. Occup Environ Med 2015;72:294–303. 10.1136/oemed-2014-102534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Leinonen T, Viikari-Juntura E, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K, et al. Labour market segregation and gender differences in sickness absence: trends in 2005-2013 in finland. Ann Work Expo Health 2018;62:438–49. 10.1093/annweh/wxx107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sauni R, Kivekäs J, Uitti J. Uudet työkyvyttömyyseläkkeet ovat vähentyneet neljänneksen. Suom Laakaril 2015;70:3056–7. [Finnish, no English Summary]. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Statistics Finland. Occupational accidents statistics. Appendix table 3 [Liitetaulukko 3. Palkansaajien työpaikkatapaturmat 1976–2013]. http://www.stat.fi/til/ttap/2013/index.html; (accessed 1 Feb 2018).

- 21. Roto P, Sainio H, Reunala T, et al. Addition of ferrous sulfate to cement and risk of chromium dermatitis among construction workers. Contact Dermatitis 1996;34:43–50. 10.1111/j.1600-0536.1996.tb02111.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Turjanmaa K, Alenius H, Reunala T, et al. Recent developments in latex allergy. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 2002;2:407–12. 10.1097/00130832-200210000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Turner S, McNamee R, Agius R, et al. Evaluating interventions aimed at reducing occupational exposure to latex and rubber glove allergens. Occup Environ Med 2012;69:925–31. 10.1136/oemed-2012-100754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Stocks SJ, McNamee R, Turner S, et al. Assessing the impact of national level interventions on workplace respiratory disease in the UK: part 1--changes in workplace exposure legislation and market forces. Occup Environ Med 2013;70:476–82. 10.1136/oemed-2012-101123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Stocks SJ, McNamee R, Turner S, et al. Assessing the impact of national level interventions on workplace respiratory disease in the UK: part 2--regulatory activity by the Health and Safety Executive. Occup Environ Med 2013;70:483–90. 10.1136/oemed-2012-101124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.