Abstract

Introduction

Health, well-being and health service needs of asylum seekers have emerged as urgent topics following the arrival of 2.5 million asylum seekers to the European Union (EU) between 2015 and 2016. However, representative information on the health, well-being and service needs of asylum seekers is scarce. The Asylum Seekers Health and Wellbeing (TERTTU) Survey aims to: (1) gather population-based representative information; (2) identify key indicators for systematic monitoring; (3) produce the evidence base for development of systematic screening of asylum seekers’ health, well-being and health service needs.

Methods and analysis

TERTTU Survey is a population-based prospective study with a total population sample of newly arrived asylum seekers to Finland, including adults and children. Baseline data collection is carried out in reception centres in 2018 and consists of a face-to-face interview, self-administered questionnaire and a health examination following a standardised protocol. Altogether 1000 asylum seekers will be included into the study. Baseline data will be followed up with national electronic health record data encompassing the entire asylum process and later with national register data among persons who receive residency permits.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval has been granted by the Coordinating Ethics Committee of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District. Participation is voluntary and based on written informed consent. Results will be widely disseminated on a national and international level to inform health and welfare policy as well as development of services for asylum seekers. Results of the study will constitute the evidence base for development and implementation of the initial health assessment for asylum seekers on a national level.

Keywords: organization of health services, health policy, protocols and guidelines, epidemiology, asylum seeker and refugee health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first population-based face-to-face interview and health examination survey producing extensive information on the health and service needs of newly arrived asylum seekers in Finland.

Total population sampling and inclusion of both adults and children into the survey allows for analysis of family units.

The prospective study design allows for examining trajectories of health of asylum seekers from the early point of arrival to Finland throughout the course of the asylum process and, if feasible, also after receiving a residence permit in Finland.

Pragmatic factors restricting the sample size of the study may lead to less precise estimates and requires conduct of analysis using groupings by region, rather than by country of origin.

Introduction

The peak in asylum applications to Europe between 2015 and 2016 highlighted the need for developing more effective policies for meeting both urgent and long-term healthcare needs of asylum seekers.1 2 An asylum seeker is defined based on their legal status as a person who has applied for international protection and is waiting for a decision on legal asylum, as opposed to a refugee who has already been granted legal asylum.3 Representative population-based information on the health and well-being of asylum seekers is needed to guide decision making and planning of healthcare services for asylum seekers.1 Such information is, however, limited in Europe.

Previous studies have focused mainly on one area of health or well-being among asylum seekers, for example, on infectious diseases,4–6 mental health,7 8 access to healthcare services9 10 and human capital.11 Asylum seekers have been reported to be disproportionally burdened by communicable and non-communicable diseases, including a high prevalence of respiratory, gastrointestinal, dermatological and sexually transmitted diseases,5 6 12 poor dental health5 and physical limitations.10 Prevalence of clinically significant symptoms of depression, anxiety and risk for post-traumatic stress disorder have also been reported to be significantly higher among asylum seekers compared with the general population in receiving countries.7 8 Asylum seekers have also been reported to have a higher prevalence of unmet needs for care, hospital admissions and visits to a psychotherapist but less visits to a general physician compared with the general German population.10

Previous studies on the health and well-being of asylum seekers are generally limited in generalisability to the entire asylum seeker population in the given country due to sample size restrictions and sampling methodology. A further common limitation in previous studies is that asylum seekers and refugees are examined as one group. No previous studies among newly arrived asylum seekers including a nationally representative population-based sample and with standardised objective health examination measures have been identified. In Finland, current information on the health and well-being of asylum seekers is limited mainly to infectious disease screening13 and access to healthcare and social services.14 According to a recent healthcare register-based study, the most common reasons for healthcare visits among asylum seekers in Finland were dental and musculoskeletal problems and mental health symptoms.15 More information is available on the health and well-being of persons of refugee origin that have a permanent residence status in Finland. Based on these studies, persons of refugee background have been found to be at a particular disadvantage with respect to a number of health outcomes, including a high incidence of chronic disease risk factors,16 mobility limitations17 and poor mental health.18

The main objective of the Asylum Seekers Health and Wellbeing (TERTTU) Survey is to gather systematic and representative interview and health examination data on the health, well-being and health service needs of newly arrived asylum seekers in Finland. Participants in the baseline TERTTU Survey will be followed up using register-based data, providing a unique opportunity to examine trajectories of health of asylum seekers from the very early stages of arrival to Finland. The TERTTU Survey data will be used for identification of key indicators for systematic monitoring of asylum seekers health at a national level. The study will also generate data that can be used for designing health promotion measures in reception centres. Correct and timely identification of vulnerable populations and persons in need of services is likely to have significant impact on the immediate and long-term health of asylum seekers.19 Furthermore, it facilitates optimising of existing resources in healthcare provision.20

Methods and analysis

The TERTTU Survey is coordinated by the Equality and Inclusion Unit of the National Institute for Health and Welfare, Finland. The study is conducted in collaboration with the Finnish Immigration Service and the reception centres as a part of an EU Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund project aiming at developing evidence-based health examination protocol for newly arrived asylum seekers.21 The Finnish Immigration Service under the Ministry of Interior is responsible for regulation, organisation, steering, supervision and funding of sheltering and health services for asylum seekers, whereas the reception centres are the main providers of healthcare services.22 Close collaboration with stakeholders provides with a unique opportunity for direct implementation of research findings into practice. Evidence-based development of the health examination protocol will promote equality in the access and quality of services provided for asylum seekers. Stages of the TERTTU Survey are outlined in table 1.

Table 1.

Stages of the TERTTU Survey

| Baseline data collection | |

| 3–10/2017 | Planning the data collection of the baseline TERTTU Survey. |

| 9/2017–1/2018 | Receiving Coordinating Ethics Committee of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District permission for implementing baseline and follow-up studies. |

| 11/2017 | Piloting the TERTTU Survey among volunteers with asylum seeker background. |

| 12/2017–1/2018 | Recruitment of the research nurses. |

| 2/2018 | Training of the research nurses. |

| 3/2018–12/2018 | Baseline data collection. |

| 2/2019–4/2019 | Data management, data quality assessment and analysis. |

| 5-6/2019 | Reporting basic findings. |

| 7/2019– | Data available for research purposes to other researchers on an accepted study proposal by the National Institute for Health and Welfare. |

| 7–12/2019 | Dissemination of the main findings of the baseline TERTTU Survey and use for evidence-based development of the national health examination protocol for newly arrived asylum seekers. |

| 1. Follow-up of TERTTU Survey participants | |

| 2020 onwards | Linkage of reception centre electronic health records to baseline TERTTU Survey data based on unique asylum process identification number. |

| 2. Follow-up of baseline TERTTU Survey participants | |

| 2020 onwards | Feasibility of linking national register data to baseline TERTTU Survey data among persons granted asylum will be evaluated. |

TERTTU, The Asylum Seekers Health and Wellbeing

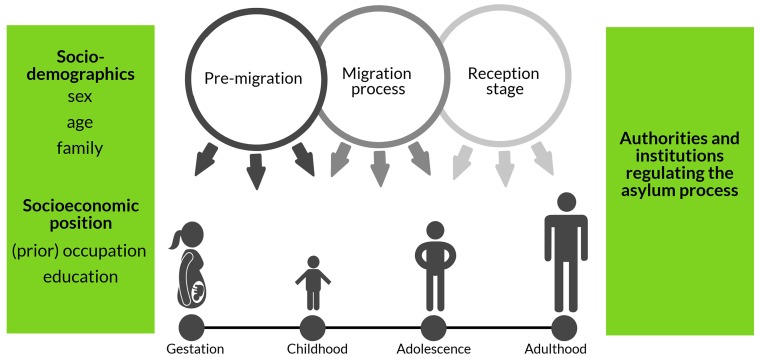

A multidisciplinary consortium was formed at the planning stage of the survey consisting of experts from different departments and units of the National Institute for Health and Welfare as well as from other collaborating bodies such as regional authorities, universities, non-governmental organisations and experts working in clinical practice. Conceptual framework of the TERTTU Survey is presented in figure 1. Asylum seekers may arrive at any life stage and their health and well-being are influenced by premigration, migration process-related and postmigration experiences. Sociodemographic and socioeconomic factors mediate the influence of migration-related factors and other exposures throughout the life course.23 Authorities and institutions regulating the asylum process have a central impact on health outcomes of asylum seekers through defining the rights for services and quality criteria for the services provided to asylum seekers.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework of the Asylum Seekers Health and Wellbeing (TERTTU) Survey.

Data collection of the TERTTU Survey is implemented by eight trained multilingual research nurses. In addition to having a good command of Finnish, languages spoken by research nurses include English, Arabic, Somali, Persian, Dari, Sorani dialect of Kurdish, Urdu, Russian, Portuguese and French. All of the study material given to the participants (including information leaflets and consent forms) have been translated into the most common languages spoken by asylum seekers, which are English, Arabic, Somali, Persian, Sorani dialect of Kurdish and Russian. Material is translated into additional languages over the course of the survey if needed. If the study participant speaks another language than the ones spoken by research nurses, a professional interpreter is used. Professional interpreters are used from accredited companies and are briefed concerning the importance of standardised protocol.

Study population

The study population includes all newly arrived asylum seekers who have applied for asylum for the first time in Finland. Exclusion criteria are persons who: (1) reside in a detention centre; (2) have applied for asylum in another country and are transferred to Finland based on international agreements (internal transfer); (3) have been returned to Finland according to the Dublin regulation; (4) have previously had a residence permit in Finland; (5) and children born in Finland. The number of asylum applications varies on a weekly basis. Participants are recruited into the study approximately 2 weeks following registration of their asylum application in Finland. Such sampling frame requires continuous sampling of study participants compared with retrospective sampling that is generally used in health interview and health examination surveys. There are approximately 40–60 new asylum applications a week fitting the selection criteria of the study, which enables inclusion of the total population sample into the study.

Both adults and children are invited to participate in the study. This enables to link family members. The population-based sample is drawn on a weekly basis from an electronic database containing data on all asylum seekers in Finland and maintained by the Finnish Immigration Services. Each asylum seeker receives a unique identity number that is used throughout the asylum seeking process. Additional registered information includes date of the asylum application, name, sex, date and country of birth, nationality, mother tongue and desired language of the interpreter services.

Recruitment of study participants

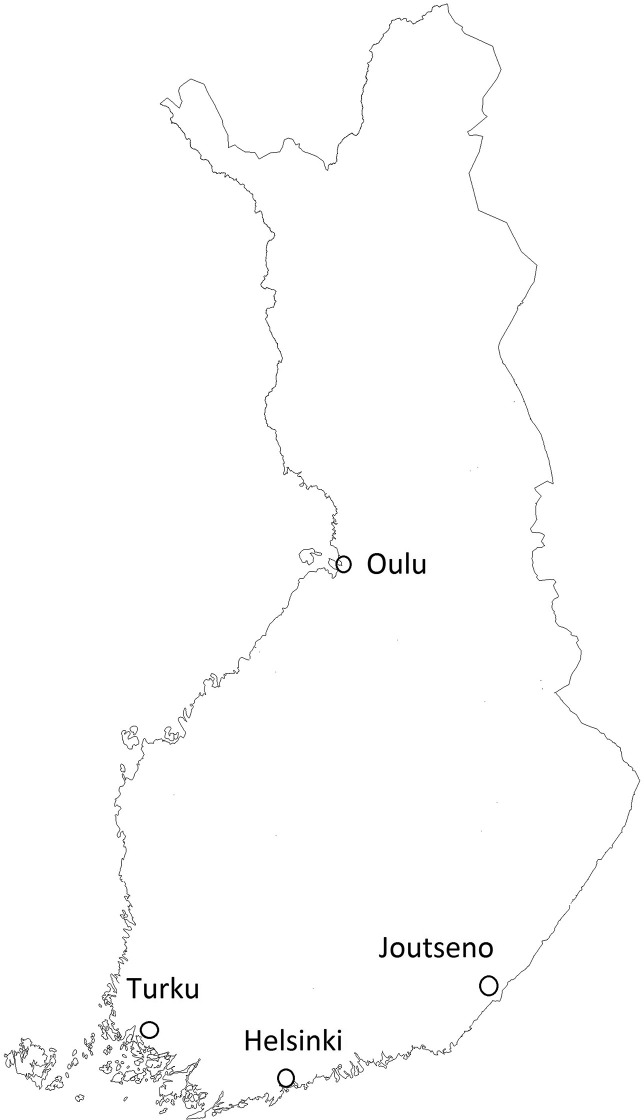

Currently (2018), there are altogether 49 reception centres in Finland, out of which 43 are for adults and families and 6 are for unaccompanied minors. The number of reception centres varies depending on the number of asylum applications and the speed of the decision processes. A substantial majority of adults and families are initially directed to transit reception centres, where they wait for the asylum interview. Transit reception centres are located in Helsinki (capital of Finland), Turku, Joutseno and Oulu (figure 2). Some newly arrived asylum seekers arrange private housing for themselves. In such case, they are allocated to the geographically closest reception centre for provision of health and social services throughout the asylum process. Unaccompanied minors are usually directed to units for minors, where they remain throughout the entire asylum process. Participants of the TERTTU Survey are recruited at an early stage of the asylum process, therefore permanent study sites have been set up at the transit reception centres. Since the TERTTU Survey is based on a total population sample, the survey is also conducted in any other national reception centres where the persons included into the study sample are situated.

Figure 2.

Permanent study locations in transit reception centres.

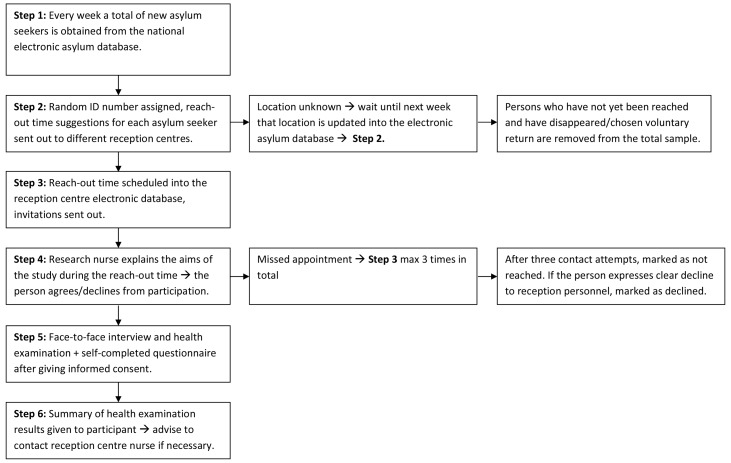

Recruitment of study participants in transit reception centres is outlined in figure 3. Recruitment is the responsibility of the research nurse. However, reception centre personnel have a central role in facilitating the initial contact between the research nurse and persons belonging to the study sample. An invitation with a set time for a reach-out appointment with the research nurse and a brief information leaflet are delivered to asylum seekers by reception centre personnel. The information leaflet is available in the study languages and is designed to be understandable even with limited language or literacy skills (see online supplementary figure 1).

Figure 3.

Flow chart of the baseline Asylum Seekers Health and Wellbeing (TERTTU) Survey.

bmjopen-2018-027917supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

The purpose of the reach-out appointment is that the research nurse makes personal contact with the persons invited to participate in the study. By providing information on the aims and content of the study, the research nurse ensures that the person invited to participate has sufficient information to give informed consent for participation. Booking a reach-out time is the only possibility for personal contact as no telephone numbers are available for newly arrived asylum seekers and research nurses do not have access to the living areas of the reception centres due to security regulations. If the asylum seeker does not arrive to their reach-out appointment, the research nurse requests the reception centre’s social counsellors to see if the person is in their dorm. If the person is on the premises of the reception centre, they are asked to come to the reception desk and talk with the research nurse. Otherwise, a new reach-out appointment is booked up to three times, unless the person expresses explicit decline from participation to reception centre personnel.

Asylum seekers living in other reception centres or in private housing are also approached through the reception centre as no personal contact information is initially available. The research nurse or the project coordinator contact the reception centre director via email and explain the purpose of the study. Following this, the research nurse contacts the reception centre for specific arrangements. Telephone contact information is usually available for persons living in private housing and in such case the research nurse contacts persons invited to participate directly by telephone. In case of unaccompanied minors, the initial contact is with the reception centre to enquire for contact details of the legal guardian who is approached by email or by telephone by the research coordinator. If the legal guardian gives consent, the unaccompanied minor is contacted and invited to participate in the study.

Two hours are booked in the research nurses’ schedule for each reach out time, which allows for conduct of the study straight away if the person agrees to participate. Alternatively, another time is agreed on. Prior to starting the interview and the health examination, the research nurse confirms the identity of the participant by checking their personal identification card. Participants are provided with detailed written information about the study, including the purpose of the study, how the collected information will be used, data protection, the rights of participants and who is responsible for conduct of the study. If written information is not available in the language spoken by the asylum seeker or the person is illiterate, the research nurse goes through written information with assistance of the professional interpreter. The purpose of the study is explained to minors in an age-appropriate manner.

Participants are asked to sign written informed consent. Separate consent is acquired for: (1) the use of the data for research and development purposes within the National Institute for Health and Welfare; (2) sharing anonymised data with researchers outside the institute; (3) record linkage of electronic patient register data to survey data; and (4) record linkage of national register data to survey data if asylum is granted in Finland. Guardians of minors sign informed consent. Additionally, children aged 7 years and older also give written informed consent. The consent form is designed in an age-appropriate manner.

Data collection

The study consists of a standardised face-to-face interview and a health examination. Duration of the study is approximately 1 hour if conducted in the mother tongue of the participant and approximately 2 hours if an interpreter is used. Some of the questions concerning mental health as well as sexual and reproductive health can be completed as self-administered questionnaires during the interview. The research nurse records whether these were interviewed or self-completed by the participants. Interviews and health examinations have been tailored for four age groups: (1) adults; (2) 13–17 year-olds; (3) 7–12 year-olds; and (4) 0–6 years. Adults and 13–17 year-olds provide their own answers for the interview, whereas the guardians of 0–12 year-olds answer to the interview questions concerning children. Minors aged 0–12 years participate only in the health examination. Research nurses received extensive training over the course of 8 days on research methods, purpose and content of the study, interview techniques as well as on conduct of standardised interview and health examination. Quality control of data collection is also monitored at different stages of data collection following the European Health Examination Survey (EHES) fieldwork quality control guidelines.24

Face-to-face interview

The face-to-face interview consists of measures used for assessment of the health, well-being, service needs of asylum seekers as well as for identification of vulnerable populations. Use of simple language was taken into account. When appropriate, selected measures are comparable with those used in other population-based surveys conducted among the general population as well as among populations of migrant origin permanently living in Finland. The content of the interview by age group is outlined in table 2. The themes covered in the interview for adults include sociodemographics, asylum seeking journey, literacy, previous socioeconomic status, health status, sexual and reproductive health, traumatic events, mental health, health behaviour and social networks. The interview for children under the age of 18 covers similar themes when relevant. Additionally, early childhood and development are also covered.

Table 2.

Content of the interview of the Asylum Seekers Health and Wellbeing Survey

| Themes | Variable/measure | Questionnaire instrument/measures | Age group |

| Sociodemographics | Age, sex, year of birth, mother tongue and prior country of permanent residence. | – | Adults. 0–17 year-olds. |

| Asylum seeking journey | Year when left permanent residence and route to Finland. | Countries, types of housing and duration of stay in these locations during the asylum journey. | Adults. 0–17 year-olds. |

| Literacy | Language skills, reading and writing skills. | Mastery of languages other than mother tongue, ability to read and write (7+ year-olds). | Adults. 0–17 year-olds. |

| Previous socioeconomic status | Education and occupation. | International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-2011)30 and prior occupation. | Adults. |

| Health status | Self-rated health and presence of long-term conditions. | Minimum European Health Module.31 | Adults. 0–17 year-olds. |

| Chronic and infectious diseases, medications and current physical symptoms. | Various health conditions diagnosed by a physician, need for regular medication, current medication, various somatic symptoms, tuberculosis symptoms, prior infectious diseases and vaccination history. | Adults. 0–17 year-olds. |

|

| Functional capacity. | Adapted from Washington Group Module.32 | Adults. | |

| Adapted from Unicef/Washington Group Module.33 | 0–17 year-olds. | ||

| Early childhood and development | Gestation and early life development. | Gestation week at birth, complications during birth, birth weight, height and early life development milestones. | 0–12 year-olds. |

| Growth and development. | Previously identified problems in growth and development. | 0–17 year-olds. | |

| Sexual and reproductive health | Sexual behaviour. | Questions related to risk behaviour predisposing to sexually transmitted diseases. | Adults. 13–17 year-olds. |

| Male circumcision/female genital mutilation. | Age of circumcision (if circumcised) and problems associated with female genital mutilation. | Adults. 0–17 year-olds. |

|

| Pregnancies and births. | Number of pregnancies, miscarriages, abortions and parity. | Adults. 13–17 year-olds. |

|

| Traumatic events | Physical trauma due to accident/violence. | Types of injuries before/during asylum journey. | Adults. 0-17 year-olds. |

| Potentially traumatic life events. | Various traumatic life events, adapted from Harvard Trauma Questionnaire.34 | Adults. | |

| Potentially traumatic events, adapted from University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) Reaction Index for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV).32 | 0–17 year-olds. | ||

| Mental health | Mental health symptoms. | Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25)35 36 and Process of Recognition and Orientation of Torture Victims in European Countries to Facilitate Care and Treatment (PROTECT-able) Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). |

Adults. 2–17 year-olds. |

| Health behaviour | Smoking. | Frequency of smoking and use of different types of tobacco products. | Adults. 13–17 year-olds. |

| Alcohol use. | Alcohol use Disorders Identification Test(AUDIT-C).37 | Adults. | |

| Alcohol use, adapted from the European School Survey Project on Alcol and Other Drugs (ESPAD) questionnaire.38 | 13–17 year-olds. | ||

| Drugs. | Use of intravenous and other drugs. | Adults. 13–17 year-old. |

|

| Diet. | Intake of selected food items. Breast-feeding (0-3 year-olds) | Adults. 0–17 year-olds. |

|

| Dental health. | Frequency of brushing teeth and latest visit to a dentist. | Adults. 0–17 year-olds |

|

| Social networks | Family members and contact with close ones. | Whereabouts of close family members and being able to be in touch with close ones. | Adults. 0–17 year-olds |

AUDIT-C, AUDIT Alcohol Consumption Questionnaire; ESPAD, The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs; PROTECT, Process of recognition and Orientation of Torture Victims in European Countries to Facilitate Care and Treatment.

Health examination

Health examination measurements are carried out following the EHES protocol.24 The content of the health examination is outlined in table 3. The health examination of adults and 13–17 year-olds consists of standardised measurements of weight, height, waist circumference, upper arm circumference, blood pressure and a dental examination. For children belonging to the 7–12 years age group, health examination consists of measurements of weight and height, dental examination and evaluation of condition of the skin. The health examination of children aged 0–6 years consists of evaluation of the condition of the skin and examination for BCG scar.

Table 3.

Content of the health examination of the Asylum Seekers Health and Well-being Survey

| Variable | Measurement tool | Measurement method | Age group |

| Weight | Seca 877. | Measured wearing no shoes and only light clothing, with no heavy objects in the pockets. If the participant is pregnant, self-reported weight before pregnancy is recorded.24 | Adults. 7–17 year-olds. |

| Height | Stand-alone stadiometer, Seca 213. | Measured wearing no shoes and standing upright, looking straight ahead.24 | Adults. 7–17 year-olds. |

| Waist circumference | Soft measuring tape, Hoechstmast. | Measurement taken on bare skin on top of light clothing, half-way between the lowest rib and the top of iliac crest.24 | Adults. 13–17 year-olds. |

| Upper arm circumference | Soft measuring tape, Hoechstmast | Measurement taken on bare skin, with the elbow resting comfortably on the surface of the table at a 90° angle. | Adults. 13–17 year-olds. |

| Blood pressure | Omron i-C10/M6 digital blood pressure monitor. | Measurement taken three times with a 1 min interval on bare skin.24 | Adults. 13–17 year-olds. |

| Pulse | Manually, with a stopwatch. | Each pulse beat is counted for 60 s.24 | Adults. 13–17 year-olds. |

| Dental examination | – | Existence of removable teeth prosthesis, number of teeth (without removable teeth prosthesis) and standardised evaluation of dental health. | Adults. 7–17 year-olds. |

| Skin condition | – | Standardised evaluation of skin condition (identification of bruises and rash). | 0–17 year-olds. |

| BCG scar | – | Standardised evaluation of the presence of BCG scar. | 0–6 year-olds. |

Linkage with register-based data

On separate consent, data collected during the TERTTU Survey can be supplemented with unified national electronic health record data of the reception centres on the basis of the unique personal identity number. This allows for following the health of asylum seekers from the initial point of arrival to Finland throughout the entire reception processes. On a separate consent, data collected during the TERTTU Survey can be supplemented with data from the national registers on the health, well-being and health service use of those who have been granted an asylum (table 4). Feasibility of this record linkage will be evaluated after a follow-up period. Record linkage with national registers provides with a unique opportunity to examine how the health of asylum seekers evolves throughout their life course.

Table 4.

Potential register linkages in the TERTTU Survey

| National register | Type of information |

| Population Register Centre | Place of residence, marital status and nationality. |

| Ministry of Employment and the Economy | Use of employment services and participation in activities for promoting employment. |

| Social Insurance Institution of Finland | Social benefits and reimbursements for medical costs. |

| National Institute for Health and Welfare | Number and reasons for healthcare visits and hospital care, procedures and treatments. |

| Statistics Finland | Socioeconomic position, education and causes of death. |

Linkage with biological data from the immunity against vaccine preventable diseases study

Parallel to the TERTTU Survey, a cross-sectional Immunity Against Vaccine Preventable Diseases Study is conducted between 2018 and 2019. The aim of the Immunity Against Vaccine Preventable Diseases Study is to assess previous immunity against measles, mumps, rubella, diphtheria, tetanus and polio among asylum seekers coming from countries with higher incidence of vaccine preventable diseases.25 The study recruits all asylum seekers from Afganistan, Iraq, Russia and Somalia who have not yet received vaccines in Finland, with the aim of gathering a minimum 100 samples per each study group. Blood samples are drawn in connection with the voluntary multiphasic screening for blood-borne and sexually transmitted infections currently offered to all asylum seekers during the initial health assessment. Nurses working in transit centres are responsible for recruitment of study participants. Participants provide written informed consent. On a separate consent, results from the Immunity Against Vaccine Preventable Diseases Study can be linked with information on sociodemographics and self-reported history of vaccinations collected during the TERTTU Survey. The Immunity Against Vaccine Preventable Diseases Study is coordinated by the National Institute for Health and Welfare and funded by the National Vaccination Program.

Power and data analysis

The aim is to gather data on a minimum of 1000 newly arrived asylum seekers. The minimum sample size for the study was calculated manually. Limited project time frame and resources restrict gathering a larger sample. The formula for calculations is enclosed as supplementary material (see online supplementary figure 2). Based on register data on the numbers, country of origin and age of first-time asylum applicants between the years of 2014 and 2016, it is projected that a sample of 1000 participants would constitute of 700 for adults and 100 minors for each of the minor age groups (0–6 years, 7–12 years and 13–17 years). This estimation was calculated assuming simple random sampling. In practice, however, with total population sampling, participation in the study will be influenced by family clusters. Members of the same family are likely to either all participate in the study or decline from participation. Calculation of estimates assuming cluster sampling was, however, not possible at the planning stage of the study because the available register data on asylum applicants from the previous years does not include information on how many families have arrived, nor on the composition of these families.

bmjopen-2018-027917supp002.pdf (85.8KB, pdf)

Using simple random sampling, an estimate of 700 adults would have a CI of roughly ±3.5%, and ±5% when examined by sex (n=350). A sample of 100 for each minor age group would result in CIs of ±10% or less. Thus, projected CIs will produce estimates of adequate accuracy if simple random sampling were applied.26 It should be, however, stressed that the CIs presented above were calculated using simple random sampling, whereas in practice cluster sampling (from family units) will be done. This is an acknowledged limitation in this study’s power calculations. Therefore, the provided CIs should be viewed as initial estimates only, and wider CIs than these are expected. This issue will be counteracted by using finite population correction,27 the formula for which is presented in the online supplementary figure 2. After finite population correction is applied, it is expected that despite cluster sampling, data on a minimum of 1000 persons will nonetheless produce estimates of adequate accuracy. Family clusters will be taken into account in all of the data analyses following the end of data collection.

The main findings of the study will be reported as a report focusing on basic findings as mean and median values, as well as proportions and their CIs. These will be presented separately for adults, 13–17 year-olds, 7–12 year-olds and 0–6 year-olds and by regions of origin. The categories for regions of origin will depend on the final number of participants from different regions. Groupings will be made according to established regional categories, for example, according to the United Nations Statistics Division groupings28 or the World Bank regional groupings.29 The effect of non-response will be assessed based on age, sex and country of origin of all asylum seekers registered in the national electronic asylum database maintained by the Finnish Immigration Service. Based on these analyses, sample weights will be calculated, if necessary, to correct for the effect of non-response.

Following the publication of the basic report, data will be made available to researchers for in-depth analyses. Total population sampling allows to examine family units. This provides with a unique opportunity to examine how the health, well-being and health service needs of, for example, parents influence those of their children in later in-depth analyses. These regression analyses will be carried out using a mixed model that includes family unit as a random effect.

Patient and public involvement

The purpose of the strudy is to fill the gap in knowledge on the health, well-being and health service use among asylum seekers. The study was designed consulting a consortium of experts on the topic of the health and well-being of asylum seekers. Persons with asylum seeker background were included into the steering committee and have provided their insights on the content of the study. No patients were directly involved in recruitment or conduct of the study. Results of the study benefit participants in that they receive information on their health and are consulted to seek further medical advice if a need for such is identified over the course of the study. Results will be disseminated in the reception centres, through media and publicly available reports on a national and international level.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical aspects

Participation in the TERTTU Survey is based on voluntary informed written consent. Participants are informed concerning personal data protection, sovereignty of the study in terms of the person’s asylum seeking process and confidentiality of the answers. It is made clear that the TERTTU Survey does not substitute the initial health assessment provided by the reception centres. Furthermore, participants are informed that they are fully entitled to decline from participation or interrupt participation at any moment without the need for providing a reason and that they are also entitled to request deletion of their data. Participants are also informed that they are entitled to leave some questions unanswered and that they may refuse any measurement.

All of the data are collected during a one-on-one research appointment. None of the data collected during the study is shared with a third person (eg, spouse, parent of 13–17 year-olds who participate independently, or reception centre personnel). Research nurses are bound by a confidentiality clause and have been trained in key principles of research ethics. Professional interpreters provide their services via the telephone, which provides a higher degree of confidentiality for the participant.

Participants are given oral and written feedback on their health examination measures. If a need for further healthcare services arises over the course of the survey visit, research nurses recommend participants to contact the reception centre nurse. All of the TERTTU Survey data are managed following the National Institute for Health and Welfare’s protocol for handling sensitive data. Each study participant is given a random study ID number, and data iare handled without personal identification information.

Incentives (eg, bus cards and toy packages for children) valued at approximately €10 are given to all participants.

Dissemination of information about the TERTTU Survey

Information about the TERTTU Survey is broadly disseminated both at national and international levels at all stages of the study. Since the TERTTU Survey has been specifically designed to bridge the gap in knowledge on the health and well-being of asylum seekers in Finland, Ministry of Interior, Ministry of Social Welfare and Health and Ministry of Economic Affairs and Employment are regularly updated on the progress of the study, and these updates are transferred into various country reports compiled by the ministries. The TERTTU Survey has been presented to a number of international collaborators and at several international congresses. Possibilities for research collaboration with international partners will be explored.

The main findings of the baseline TERTTU Survey will be reported by the end of summer 2019, and they will be widely disseminated at both national and international level. Following this, TERTTU Survey data will be available for research purposes on an accepted study proposal. Evidence-based health examination protocol will be developed and disseminated across reception centres on a national level by the end of 2019.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge experts at the Finnish Immigration Service and all of the personnel of collaborating reception centres for their substantial efforts in facilitating implementation of the study. All of the participants in the study, the research nurses involved in baseline data collection, the multidisciplinary consortium of experts from the National Institute for Health and Welfare and collaborating bodies as well as the steering committee of the Developing the Health Examination Protocol for Asylum Seekers in Finland Project also need to be acknowledged. Finally, the authors would like to acknowledge Sinikka Kytö and Kaaren Erhola for the graphical visualisation of the TERTTU Survey material.

Footnotes

Contributors: AC and OS conceptualised the initial idea for the national-level project aiming at developing the health examination protocol for asylum seekers in Finland within which the TERTTU Survey is implemented. AC developed the original grant proposal. NS, AC, PK, K-LM and EL have been involved in planning and coordination of the study. OS has been the main contact on the behalf of the collaborating partner (Finnish Immigration Service). PT has been involved in the design and coordination of the Immunity Against Vaccine Preventable Diseases Study. NS prepared the first draft of the manuscript. All authors have provided critical feedback and contributed to revision of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: TERTTU Survey is implemented as a part of the Developing the Health Examination Protocol for Asylum Seekers in Finland: A National Development Project funded by the EU Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund, grant number SMDno-2016-1541.

Disclaimer: The depiction of boundaries on the map(s) in this article do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of BMJ (or any member of its group) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, jurisdiction or area or of its authorities. The map(s) are provided without any warranty of any kind, either express or implied.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study has been approved by the Coordinating Ethics Committee of the Helsinki and Uusimaa Hospital District (HUS/3330/2017).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Bozorgmehr K, Goosen S, Mohsenpour A, et al. How Do Countries' Health Information Systems Perform in Assessing Asylum Seekers' Health Situation? Developing a Health Information Assessment Tool on Asylum Seekers (HIATUS) and Piloting It in Two European Countries. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:894 10.3390/ijerph14080894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bozorgmehr K, Razum O. Forced Migration and Global Responsibility for Health Comment on "Defining and Acting on Global Health: The Case of Japan and the Refugee Crisis". Int J Health Policy Manag 2016;6:415–8. 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. European Union. Who qualifies for international protection. 2018. Available https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/policies/asylum/refugee-status_en (accessed 1 Jun 2018).

- 4. Alberer M, Malinowski S, Sanftenberg L, et al. Notifiable infectious diseases in refugees and asylum seekers: experience from a major reception center in Munich, Germany. Infection 2018;46:375–83. 10.1007/s15010-018-1134-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Berlaer G, Bohle Carbonell F, Manantsoa S, et al. A refugee camp in the centre of Europe: clinical characteristics of asylum seekers arriving in Brussels. BMJ Open 2016;6:e013963 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013963 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bloch-Infanger C, Bättig V, Kremo J, et al. Increasing prevalence of infectious diseases in asylum seekers at a tertiary care hospital in Switzerland. PLoS One 2017;12:e0179537 10.1371/journal.pone.0179537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Leiler A, Bjärtå A, Ekdahl J, et al. Mental health and quality of life among asylum seekers and refugees living in refugee housing facilities in Sweden. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2018. 10.1007/s00127-018-1651-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Georgiadou E, Morawa E, Erim Y. High Manifestations of Mental Distress in Arabic Asylum Seekers Accommodated in Collective Centers for Refugees in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14 10.3390/ijerph14060612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bozorgmehr K, Schneider C, Joos S. Equity in access to health care among asylum seekers in Germany: evidence from an exploratory population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res 2015;15:502 10.1186/s12913-015-1156-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schneider C, Joos S, Bozorgmehr K. Disparities in health and access to healthcare between asylum seekers and residents in Germany: a population-based cross-sectional feasibility study. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008784 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Buber-Ennser I, Kohlenberger J, Rengs B, et al. Human Capital, Values, and Attitudes of Persons Seeking Refuge in Austria in 2015. PLoS One 2016;11:e0163481 10.1371/journal.pone.0163481 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pavli A, Maltezou H. Health problems of newly arrived migrants and refugees in Europe. J Travel Med 2017;24 10.1093/jtm/tax016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tiittala P, Tuomisto K, Puumalainen T, et al. Public health response to large influx of asylum seekers: implementation and timing of infectious disease screening. BMC Public Health 2018;18:1139 10.1186/s12889-018-6038-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tiittala PSE. Asylum seekers’ access to mental health and dental health services, and prevention of infection disease problems in Finland in 2017. Research brief 10 National Institute for Health and Welfare. Helsinki, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tiittala P, Räisänen P, Lilja E, et al. Healthcare service use and health concerns among asylum seekers in Finland in 2015–2016. Data brief 29, National Institute for Health and Welfare. Helsinki, Finland, 2018. Available http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-343-187-4 (accessed 19 Jan 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16. Skogberg N, Laatikainen T, Jula A, et al. Contribution of sociodemographic and lifestyle-related factors to the differences in metabolic syndrome among Russian, Somali and Kurdish migrants compared with Finns. Int J Cardiol 2017;232:63–9. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.01.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rask S, Sainio P, Castaneda AE, et al. The ethnic gap in mobility: a comparison of Russian, Somali and Kurdish origin migrants and the general Finnish population. BMC Public Health 2016;16:340 10.1186/s12889-016-2993-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rask S, Suvisaari J, Koskinen S, et al. The ethnic gap in mental health: a population-based study of Russian, Somali and Kurdish origin migrants in Finland. Scand J Public Health 2016;44:281–90. 10.1177/1403494815619256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bozorgmehr K, Razum O. Effect of Restricting Access to Health Care on Health Expenditures among Asylum-Seekers and Refugees: A Quasi-Experimental Study in Germany, 1994-2013. PLoS One 2015;10:e0131483 10.1371/journal.pone.0131483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bozorgmehr K, Wenner J, Razum O. Restricted access to health care for asylum-seekers: applying a human rights lens to the argument of resource constraints. Eur J Public Health 2017;27:592–3. 10.1093/eurpub/ckx086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. National Institute for Health and Welfare. Developing the health examination protocol for asylum seekers in Finland: A national development project (TERTTU), 2018. Available: https://thl.fi/en/web/thlfi-en/research-and-expertwork/projects-and-programmes/developing-the-health-examination-protocol-for-asylum-seekers-in-finland-a-national-development-project-terttu- (accessed 1 Nov 2018).

- 22. Helve O, Tuomisto K, Tiittala P, et al. Asylum seekers’ health care in Finland in 2015–2016. Report on a survey of reception centres. Helsinki, Finland: National Institute for Health and Welfare, 2016;19 ISBN 978-952-302-774-9 (printed); ISBN 978-952-302-775-6 (pdf) Available: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-302-775-6 (accessed 15 Jan 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Abubakar I, Aldridge RW, Devakumar D, et al. The UCL-Lancet Commission on Migration and Health: the health of a world on the move. Lancet 2018;392:2606–54. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32114-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Tolonen H. Part B, Fieldwork Procedures. Directions 2016_14, 2016. Available: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-302-701-5 (accessed 1 Jul 2018).

- 25. Mipatrini D, Stefanelli P, Severoni S, et al. Vaccinations in migrants and refugees: a challenge for European health systems. A systematic review of current scientific evidence. Pathog Glob Health 2017;111:59–68. 10.1080/20477724.2017.1281374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lwanga SK, Lemeshow S. Sample size determination in health studies: a practical manual. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1991. Available: http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/40062 (accessed 1 Jul 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lehtinen RPE. Practical Methods for Design and Analysis of Complex Surveys. 2nd edn: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28. United Nations Statistics Division. Methodology: Standard country or area codes for statistical use, 2019. Available: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/methodology/m49/ (accessed 23 Jan 2019).

- 29. The World Bank. Data: World Bank Country and Lending Groups, 2019. Available: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups (accessed 23 Jan 2019).

- 30. UNESCO Institute of Statistics. International Standard Classification of Education ISCED 2011. 2012, 2018. Available: http://uis.unesco.org/sites/default/files/documents/international-standard-classification-of-education-isced-2011-en.pdf (accessed 20 Oct 2018).

- 31. Eurostat. European Health Interview Survey (EHIS Wave 3). Methodological manual. Luxembourg: Publications office of the European Union, 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/8762193/KS-02-18-240-EN-N.pdf/5fa53ed4-4367-41c4-b3f5-260ced9ff2f6. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pynoos R, Rodriguez N, Steinberg A, et al. UCLA PTSD Index for DSM-IV, 1998. Available https://www.mc.vanderbilt.edu/coe/tfcbt/workbook/Assessment/UCLA%20PTSD%20Index-%20Parent.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2018).

- 33. Loeb M, Cappa C, Crialesi R, et al. Measuring child functioning: the Unicef/ Washington Group Module. Salud Publica Mex 2017;59:485–7. 10.21149/8962 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mollica RF, Caspi-Yavin Y, Bollini P, et al. The Harvard Trauma Questionnaire. Validating a cross-cultural instrument for measuring torture, trauma, and posttraumatic stress disorder in Indochinese refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis 1992;180:111–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, et al. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci 1974;19:1–15. 10.1002/bs.3830190102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Dimitrova M, Gologanova K, Friele B, et al. PROTECT - Process of recognition and Orientation of Torture Victims in European Countries to Facilitate Care and Treatment. http://protect-able.eu/wp-content/uploads/2013/01/protect-global-eng.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2018).

- 37. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, et al. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1789–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. ESPAD. Questionnaire of Substance Use. The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs, 2011. Available: http://www.espad.org/sites/espad.org/files/ESPAD_Questionnaire_2011.pdf (accessed 1 Jul 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027917supp001.pdf (1.4MB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-027917supp002.pdf (85.8KB, pdf)