Abstract

Introduction

Physical activity (PA) during first 20 weeks of pregnancy may lower risks of gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and gestational hypertension (GH), though evidence of association remains inconclusive. Current studies rely heavily on subjective assessment of PA levels. Wearable activity trackers provide a convenient and objective surrogate index for PA validated by evidence-based steps/day categorisation along a physical inactivity/activity continuum. I-ACT primarily aims to examine objectively measured PA levels and patterns in first and second trimesters of pregnancy and the association with GDM and/or GH in Singapore, a multiethnic Asian population. Secondary aims include investigating the bio-socio-demographic factors associated with sedentary behaviour, and association of early pregnancy PA level with maternal weight at 6 weeks postdelivery. Results may facilitate identification of high-risk mothers-to-be and formulation of interventional strategies.

Methods and analysis

Prospective cohort study that will recruit 408 women at first antenatal visit at <12 weeks’ gestation. Baseline bio-socio-demographic factors and PA levels assessed by participant characteristics form and the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ), respectively. An activity tracker (Fitbit) will be provided to be worn daily from date of recruitment to end of 20 weeks’ gestation. Tracker-recorded data will be synchronised with an application on participant’s smartphone. Compliance will be reinforced with fortnightly reminders. After 20 weeks, a second IPAQ and a feedback form will be administered. GDM screened at 24–28 weeks’ gestation. GH diagnosed after 20-weeks gestation. Maternal weight assessed at 6 weeks postdelivery. Appropriate statistical tests will be used to compare continuous and categorical PA measurements between first and second trimesters. Logistic regression will be used to analyse associations.

Ethics and dissemination

Ethical approval obtained from the Centralised Institutional Review Board of SingHealth (reference 2017/2836). Dissemination of results will be via peer-reviewed research publications both online and in print, conference presentations, posters and medical forums.

Keywords: diabetes in pregnancy, maternal medicine, preventive medicine, primary care

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Prospective cohort study of a multiethnic Asian population.

Objective measurement of physical activity levels and patterns in early pregnancy.

Data collection designed to minimise recall bias.

Participant non-compliance despite reinforcement measures.

Participants’ unfamiliarity with wearable activity tracker and mobile application despite education at recruitment.

Introduction

Physical activity (PA) is defined as any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure.1 Current recommendations encourage women with uncomplicated pregnancies to continue or initiate safe physical activities in pregnancy.2 More specifically, the CDC recommends 30 min/day for 5 days each week of moderate-intensity aerobic activity, which can be met by walking.3 Concerns about safety have been refuted by literature demonstrating that moderate exercise in low-risk pregnancy improves maternal well-being without associated risks of birth weight reduction or preterm birth.4

Physical inactivity or sedentary behaviour in early pregnancy (<20 weeks’ gestation) is a potential modifiable risk factor for two common obstetric complications, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and gestational hypertension (GH). GDM is defined as carbohydrate intolerance that develops during pregnancy.5 It complicates 1.8%–25.1% of pregnancies worldwide depending on country and definition, with Southeast Asia having the second highest prevalence at 8.1–18.36. Approximately 8%–20% of pregnancies are affected in Singapore.7 Overall prevalence of GH, otherwise known as pregnancy-induced hypertension, is estimated at 10%–12%,8 9 though the local incidence has not been established. Perinatal sequelae of GDM and GH include macrosomia, neonatal hypoglycaemia, preterm birth, intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), and low Apgar scores. Both metabolic disorders are also proven risk factors of future type 2 diabetes.10

Current literature investigating the association between PA in early pregnancy and the development of GDM has shown a significant risk reduction of up to 24%,11–14 though a few other studies have found a null association or insufficient evidence.15–17 The association with GH is even less clear from the limited literature available.18–21 All these studies used questionnaires as a measurement of PA. Studies that incorporate an objective means of measurement have been scarce,22 23 which may partially explain the inconclusive evidence of association thus far. A Norway-based study investigating objectively recorded PA in early pregnancy and GDM reported that the adjusted OR for GDM decreased 19% with every 3159 step-increase per day.22 Based on these existing studies, physical inactivity in early pregnancy is a modifiable risk factor worth targeting.

This is especially so in the Asian population. PA during first half of pregnancy has been shown to be low in an Asian urban setting,24 and similarly lower when compared with non-Asian counterparts.23 25 In Singapore, no published study on objectively measured PA levels in pregnancy could be found, and studies on association of subjectively measured early pregnancy PA levels with both obstetric complications are rare. Padmapriya et al investigated the change in PA levels from a prepregnancy to pregnancy state using a structured self-constructed questionnaire administered at 26–28 weeks’ gestation scored based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ) short form.26 The same study group further reported that a higher PA during the first 6 months of pregnancy was associated with lower prevalence of GDM, especially among overweight/obese women.27 However, the use of a questionnaire at 26–28 weeks’ gestation that relied on recall of PA levels during first 6 months of pregnancy and the year before subjected the results to a high level of recall bias. Therefore, the paucity of local research on objectively measured PA levels in early pregnancy and association with obstetric metabolic outcomes warrants additional prospective studies.

As evident from existing studies, current assessment of pregnancy PA levels relies heavily on subjective, self-reporting questionnaires deemed to be the most feasible method with the absence of a gold standard and clear guidelines.28 The inclusion of more objective measurements is being advocated.29 Consumer wearable activity trackers operate through a three-axis accelerometer, providing an alternative convenient and objective means of assessing PA levels during pregnancy. The accuracy, reliability and efficacy of wearable activity trackers in various health programmes have been validated,30–33 although a systematic review has found the research-grade accelerometer or pedometer to be superior in terms of accuracy.34 Steps per day categorisation along a physical inactivity/activity continuum based on CDC recommendation has also been elucidated, with 5000 (sedentary) and 10 000 (active) being the primary anchor points.35 The correlation between steps per day and activity counts per day, from which activity intensity and duration were derived, was proven to be positive and strong, thus validating its use as an index for PA.36 Step count estimated by Fitbit activity trackers among healthy adults has also been validated in a separate study.37 Furthermore, various measured parameters such as step count and moderate-to-vigorous PA of different Fitbit activity trackers models have also been validated in the particular population of pregnant women in free living conditions.38

Through the use of both Fitbit activity trackers and the IPAQ, this prospective multiethnic cohort study primarily aims to investigate the PA levels and patterns in early pregnancy (first trimester and second trimester up to 20 weeks’ gestation), as well as the effect of PA in early pregnancy on development of GDM and/or GH. Secondary aims include assessing the bio-socio-demographic factors associated with sedentary behaviour, and examining the association between early pregnancy PA level and maternal weight at 6 weeks postdelivery.

Methods and analysis

Study design

In this prospective cohort study, pregnant women will be recruited at outpatient clinics in KK Women’s and Children’s Hospital, a major public hospital in Singapore that sees a high volume of obstetrics and gynaecology consultations. Recruitment started in June 2018 and is expected to end in 2019. This study will follow the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology reporting guideline for cohort studies.

Recruitment and eligibility criteria

All obstetricians running outpatient general obstetrics and gynaecology clinics will refer suitable candidates for recruitment. All recruitment will be done via face-to-face contact by the research team.

Inclusion criteria are singleton pregnancy, first antenatal visit less than 12 weeks’ gestation and ages between 21 and 50 years inclusive. Exclusion criteria are severe medical and/or psychological comorbidity (including New York Heart Association class IV heart failure, end-stage renal disease, assistive device-dependent for mobility, cognitive impairment and loss of rational thinking) and skin conditions (including contact dermatitis, pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid) precluding the wearing of activity trackers.

Power analysis

Given that prevalence of GH has not been investigated in Singapore, GDM prevalence is used instead. Assuming that GDM proportion is 17.6%39 and that PA can reduce risk of GDM by 30%, a sample of 367 mothers will be required at 80% power and 5% level of significance. Assuming a dropout rate of 10%, a sample of 408 mothers will be recruited into the study.

Participant timeline

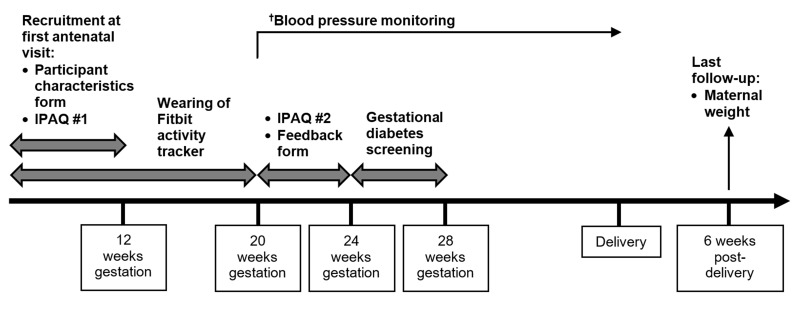

Recruitment is at first antenatal visit less than 12 weeks’ gestation, during which Fitbit education, IPAQ and participant characteristics form are done (figure 1). PA level monitoring occurs henceforth until end of 20 weeks’ gestation inclusive. The standard 4-weekly antenatal visits will continue during this period. After 20 weeks’ gestation, a second IPAQ and a feedback form are administered either at regular antenatal visits before 24 weeks’ gestation, or over the phone/email. Routine GDM screening takes place between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation. The final follow-up occurs at the 6th week after delivery to obtain participants’ weight.

Figure 1.

Timeline of the I-ACT prospective cohort study. †Participants will continue to attend routine antenatal visits throughout the study period during which blood pressure monitoring will be done. IPAQ, International Physical Activity Questionnaire.

Ensuring compliance

Approaches to enhance compliance include reinforcing the importance of commitment to wearing the activity trackers daily at the time of recruitment, and making fortnightly follow-up calls up until 20 weeks’ gestation. Compliance will also be recorded as part of Fitbit use assessment in the participant feedback form at the end of 20 weeks’ gestation.

Outcome measures

Primary outcomes include the following:

GDM: diagnosed if the following threshold value at any time point is exceeded after a 75 g oral glucose tolerance test between 24 and 28 weeks’ gestation based on the International Association of Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Groups (IADPSG) criteria: fasting venous plasma glucose of ≥5.1 mmol/L, 1-hour venous plasma glucose of ≥10.0 mmol/L, and 2-hour venous plasma glucose ≥8.5 mmol/L40.

GH: diagnosed as new onset hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140 mm Hg and/or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mm Hg) measured on two occasions at least 4 hours apart after 20 weeks’ gestation in the absence of proteinuria or new signs of end-organ dysfunction.41

Secondary outcomes include the following:

Weight at 6 weeks postdelivery.

Weight gain in pregnancy.

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).

Preterm birth (gestational age <37 weeks).

Macrosomia (birth weight >90th percentile or >4.0 kg).

Neonatal hypoglycaemia (glucose <2.5 mmol/L).

Pre-eclampsia.

Apgar scores.

Data collection

Research participant characteristics form

Sociodemographic data to be assessed include marital status, educational level, household income, type of housing, working status during pregnancy, smoking status and alcohol consumption. Medical history including prepregnancy height and weight, parity, history of infertility treatment, existing chronic illnesses, history of GDM and/or GH, family history of DM and reasons behind potential PA restriction during early pregnancy will also be collected.

Fitbit activity tracker and mobile application

At recruitment, each participant is given a wristband activity tracker (Fitbit) that will be connected via Bluetooth to a Fitbit application downloaded onto her smartphone. Education on device and application will be carried out. The tracker is worn daily from recruitment to end of 20 weeks’ gestation inclusive, except during bathing or water activities. Participants are advised to synchronise the tracker data at least once a week. For data to be valid, wear-time must be at least 4 days per week (including 1 weekend day) and at least 10 hours/day.

Steps per day will be recorded by the tracker. Data will be reported as continuous and categorical variables. Continuous variables include mean weekday and weekend steps per day and mean steps per day in first and second trimesters. Categorical variables include classification into a CDC recommendation-based steps per day physical inactivity/activity continuum defined as follows: (1) <5000 (sedentary); (2) 5000–7499 (low active); (3) 7500–9999 (somewhat active); (4) 10 000–12,499 (active); and (5) ≥12 500 (highly active).35

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

The IPAQ long version will be self-administered during the first visit at less than 12 weeks’ gestation in the first trimester and again between 20 and 24 weeks’ gestation in the second trimester. It is a set of four questionnaires assessing five activity domains (occupation, transportation, household, leisure and sedentary) independently in the past 7 days, and may be administered via self or telephone.42 Well-established and validated in adults aged 15–69 years, it is available in both English and Chinese.43 44 It has been used in studies involving pregnant women.29 45

Data will be reported as continuous and categorical variables. Continuous variables include median met abolic equivalent (MET)-minutes per week (MET-min/week) and IQRs computed for each domain, subdomain (walking, moderate-intensity PA and vigorous-intensity PA) and overall total PA. MET or metabolic equivalent is a unit that measures energy expenditure in multiples of the resting metabolic rate.46 Categorical variables include classification into low, moderate, high levels of PA according to the IPAQ scoring protocol.

Medical record data

Additional data to be collected include ethnicity, weight changes during pregnancy, weight at 6 weeks postdelivery, obstetric outcomes of GDM, GH, pre-eclampsia and IUGR, and neonatal outcomes comprising Apgar scores, preterm birth, macrosomia and neonatal hypoglycaemia.

Participant feedback form

After the end of 20 weeks’ gestation, experience with the activity tracker and mobile application in terms of usability and troubleshooting will be evaluated. Compliance level will be quantified by number of days per week.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics of PA levels in the first and early second trimester will be presented. Categorical variables will be presented as n (%) while continuous variables will be presented as mean (SD) or median (IQR). Mean steps per day and median MET-minutes per week between semesters will be compared using paired Student’s t-test and Wilcoxon signed-rank test, respectively. McNemar’s test will be used to compare sedentary behaviour between semesters. Similar tests will be employed to assess for a difference in PA levels between weekdays and weekends.

Binary logistic regression will be used to evaluate the association of early pregnancy PA with GDM and/or GH. Crude (unadjusted) and adjusted regression models will be included. Potential confounders will be identified a priori based on literature review and controlled for in the regression analyses. Potential interactions between covariates and early pregnancy PA will be tested using cross-product terms. Secondary analyses on the bio-socio-demographic factors associated with sedentary behaviour, as well as the association between early pregnancy PA level and maternal weight at 6 weeks postdelivery, will follow the methods of the primary analyses, but are exploratory having not been powered to formally test the hypotheses. All regression analyses will be presented as ORs with 95% CIs.

Statistical analyses will be performed using IBM SPSS Statistics V.23.0. P values of <0.05 will be considered statistically significant.

Safety parameters

Adverse effects and device monitoring will be carried out at the subsequent 4-weekly routine prenatal visits. Any adverse skin reaction to the wristband will be recorded. Participation will be stopped at any time the Principal Investigator decides that continuing on could be harmful to the participant.

Data management

All data will be coded for confidentiality. Hardcopy data will be stored at the research site under lock and key. Electronic data can only be accessed and retrieved from the secured website by the participant and research team. Electronic data will be exported on a fortnightly basis. All data obtained will be entered into and stored on the institution Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) system, a centralised secured data management server with password access. Data integrity monitoring will be carried out monthly by the principal investigator and coinvestigators if deemed necessary.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the development of the research question and outcome measures.

Ethics and dissemination

Informed written consent will be sought from all participants.

Results from this study will be submitted to the funding organisation and peer-reviewed journals for consideration of publication both online and in print. Results will also be presented at relevant meetings, conferences and medical forums in either oral or poster formats.

Conclusion

The I-ACT study aims to be the first comprehensive study objectively evaluating the PA levels and patterns in early pregnancy, and their association with GDM and/or GH in the multiethnic population of Singapore. In addition to addressing these important scientific knowledge gaps, from a clinical perspective, the study itself may increase awareness of PA during early pregnancy while demonstrating the potential of wearable activity trackers as an objective measure of PA in health research. More importantly, we hope the results of the study facilitate the identification of high-risk mothers-to-be for targeted intervention, and help formulate strategies for interventional efforts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Satvinder Singh Dhaliwal for providing statistical advice during the conception of this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: MC was involved in all aspects of the study from conception, design, recruitment and manuscript writing. KHT and SBA provided critical review of the design and writing. As Principle Investigator, SBA takes overall responsibility for the work. All authors agree to be accountable for their work.

Funding: This work is supported by the AM-ETHOS Duke-NUS Medical Student Fellowship (AM-ETHOS01/FY2017/01-A01). In addition, the primary author is supported by the Integrated Platform for Research in Advancing Metabolic Health Outcomes in Women and Children (IPRAMHO).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the Centralised Institutional Review Board of SingHealth (reference 2017/2836).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep 1985;100:126–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Anon. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 650: Physical Activity and Exercise During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Obstet Gynecol 2015;126:e135–42. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention. Physical Activity Basics. https://www.cdc.gov/physicalactivity/basics/pregnancy/index.htm (Accessed 10 Jul 2017).

- 4. Nascimento SL, Surita FG, Cecatti JG. Physical exercise during pregnancy: a systematic review. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2012;24:387–94. 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328359f131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational Diabetes Mellitus. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:e49–e64. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zhu Y, Zhang C. Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes and Risk of Progression to Type 2 Diabetes: a Global Perspective. Curr Diab Rep 2016;16:7 10.1007/s11892-015-0699-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yew TW, Khoo CM, Thai AC, et al. . The Prevalence of Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Among Asian Females is Lower Using the New 2013 World Health Organization Diagnostic Criteria. Endocr Pract 2014;20:1064–9. 10.4158/EP14028.OR [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lim WY, Saw SM, Tan KH, et al. . A cohort evaluation on arterial stiffness and hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2012;12:160 10.1186/1471-2393-12-160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nelson-Piercy C. Handbook of obstetric medicine. 5th edn Boca Raton: CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Group, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rayanagoudar G, Hashi AA, Zamora J, et al. . Quantification of the type 2 diabetes risk in women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 95,750 women. Diabetologia 2016;59:1403–11. 10.1007/s00125-016-3927-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nasiri-Amiri F, Bakhtiari A, Faramarzi M, et al. . The association between physical activity during pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus: a case-control study. Int J Endocrinol Metab 2016;14:e37123 10.5812/ijem.37123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tobias DK, Zhang C, van Dam RM, et al. . Physical activity before and during pregnancy and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 2011;34:223–9. 10.2337/dc10-1368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dempsey JC, Sorensen TK, Williams MA, et al. . Prospective study of gestational diabetes mellitus risk in relation to maternal recreational physical activity before and during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol 2004;159:663–70. 10.1093/aje/kwh091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dempsey JC, Butler CL, Sorensen TK, et al. . A case-control study of maternal recreational physical activity and risk of gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 2004;66:203–15. 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oken E, Ning Y, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. . Associations of physical activity and inactivity before and during pregnancy with glucose tolerance. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:1200–7. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000241088.60745.70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chasan-Taber L, Schmidt MD, Pekow P, et al. . Physical activity and gestational diabetes mellitus among Hispanic women. J Womens Health 2008;17:999–1008. 10.1089/jwh.2007.0560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yin YN, Li XL, Tao TJ, et al. . Physical activity during pregnancy and the risk of gestational diabetes mellitus: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:290–5. 10.1136/bjsports-2013-092596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Marcoux S, Brisson J, Fabia J. The effect of leisure time physical activity on the risk of pre-eclampsia and gestational hypertension. J Epidemiol Community Health 1989;43:147–52. 10.1136/jech.43.2.147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vollebregt KC, Wolf H, Boer K, et al. . Does physical activity in leisure time early in pregnancy reduce the incidence of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension? Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2010;89:261–7. 10.3109/00016340903433982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Spracklen CN, Ryckman KK, Triche EW, et al. . Physical Activity During Pregnancy and Subsequent Risk of Preeclampsia and Gestational Hypertension: A Case Control Study. Matern Child Health J 2016;20:1193–202. 10.1007/s10995-016-1919-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Saftlas AF, Logsden-Sackett N, Wang W, et al. . Work, leisure-time physical activity, and risk of preeclampsia and gestational hypertension. Am J Epidemiol 2004;160:758–65. 10.1093/aje/kwh277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Richardsen KR, Mdala I, Berntsen S, et al. . Objectively recorded physical activity in pregnancy and postpartum in a multi-ethnic cohort: association with access to recreational areas in the neighbourhood. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2016;13:78 10.1186/s12966-016-0401-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mørkrid K, Jenum AK, Berntsen S, et al. . Objectively recorded physical activity and the association with gestational diabetes. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2014;24:e389–e397. 10.1111/sms.12183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang Y, Dong S, Zuo J, et al. . Physical activity level of urban pregnant women in Tianjin, China: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2014;9:e109624 10.1371/journal.pone.0109624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guelfi KJ, Wang C, Dimmock JA, et al. . A comparison of beliefs about exercise during pregnancy between Chinese and Australian pregnant women. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2015;15:345 10.1186/s12884-015-0734-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Padmapriya N, Shen L, Soh SE, et al. . Physical activity and sedentary behavior patterns before and during pregnancy in a multi-ethnic sample of Asian Women in Singapore. Matern Child Health J 2015;19:2523–35. 10.1007/s10995-015-1773-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Padmapriya N, Bernard JY, Liang S, et al. . Associations of physical activity and sedentary behavior during pregnancy with gestational diabetes mellitus among Asian women in Singapore. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017;17:364 10.1186/s12884-017-1537-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Strath SJ, Kaminsky LA, Ainsworth BE, et al. . Guide to the assessment of physical activity: Clinical and research applications: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2013;128:2259–79. 10.1161/01.cir.0000435708.67487.da [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Harrison CL, Thompson RG, Teede HJ, et al. . Measuring physical activity during pregnancy. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2011;8:19 10.1186/1479-5868-8-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Evenson KR, Goto MM, Furberg RD. Systematic review of the validity and reliability of consumer-wearable activity trackers. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:159 10.1186/s12966-015-0314-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lee JM, Kim Y, Welk GJ. Validity of consumer-based physical activity monitors. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:1840–8. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ferguson T, Rowlands AV, Olds T, et al. . The validity of consumer-level, activity monitors in healthy adults worn in free-living conditions: a cross-sectional study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 2015;12:42 10.1186/s12966-015-0201-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Cheatham SW, Stull KR, Fantigrassi M, et al. . The efficacy of wearable activity tracking technology as part of a weight loss program: a systematic review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2018;58:534–48. 10.23736/S0022-4707.17.07437-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Feehan LM, Geldman J, Sayre EC, et al. . Accuracy of fitbit devices: systematic review and narrative syntheses of quantitative data. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 2018;6:e10527 10.2196/10527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Tudor-Locke C, Hatano Y, Pangrazi RP, et al. . Revisiting "how many steps are enough?". Med Sci Sports Exerc 2008;40(7 Suppl):S537–S543. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31817c7133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tudor-Locke C, Johnson WD, Katzmarzyk PT. Relationship between accelerometer-determined steps/day and other accelerometer outputs in US adults. J Phys Act Health 2011;8:410–9. 10.1123/jpah.8.3.410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Diaz KM, Krupka DJ, Chang MJ, et al. . Fitbit®: An accurate and reliable device for wireless physical activity tracking. Int J Cardiol 2015;185:138–40. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.03.038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. St-Laurent A, Mony MM, Mathieu MÈ, et al. . Validation of the Fitbit Zip and Fitbit Flex with pregnant women in free-living conditions. J Med Eng Technol 2018;42:259–64. 10.1080/03091902.2018.1472822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. de Seymour J, Chia A, Colega M, et al. . Maternal Dietary Patterns and Gestational Diabetes Mellitus in a Multi-Ethnic Asian Cohort: The GUSTO Study. Nutrients 2016;8:574 10.3390/nu8090574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Metzger BE, Gabbe SG, Persson B, et al. . International association of diabetes and pregnancy study groups recommendations on the diagnosis and classification of hyperglycemia in pregnancy. Diabetes Care 2010;33:e98–682. 10.2337/dc10-0719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 2013;122:1122–31. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000437382.03963.88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Downloadable questionnaires. https://sites.google.com/site/theipaq/questionnaire_links.

- 43. Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjöström M, et al. . International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2003;35:1381–95. 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Macfarlane D, Chan A, Cerin E. Examining the validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the International Physical Activity Questionnaire, long form (IPAQ-LC). Public Health Nutr 2011;14:443–50. 10.1017/S1368980010002806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kinnunen TI, Pasanen M, Aittasalo M, et al. . Preventing excessive weight gain during pregnancy - a controlled trial in primary health care. Eur J Clin Nutr 2007;61:884–91. 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Jetté M, Sidney K, Blümchen G. Metabolic equivalents (METS) in exercise testing, exercise prescription, and evaluation of functional capacity. Clin Cardiol 1990;13:555–65. 10.1002/clc.4960130809 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.