Abstract

Objectives

Worldwide, emergency healthcare systems are under intense pressure from ever-increasing demand and evidence is urgently needed to understand how this can be safely managed. An estimated 10%–43% of emergency department patients could be treated by primary care services. In England, this has led to a policy proposal and £100 million of funding (US$130 million), for emergency departments to stream appropriate patients to a co-located primary care facility so they are ‘free to care for the sickest patients’. However, the research evidence to support this initiative is weak.

Design

Rapid realist literature review.

Setting

Emergency departments.

Inclusion criteria

Articles describing general practitioners working in or alongside emergency departments.

Aim

To develop context-specific theories that explain how and why general practitioners working in or alongside emergency departments affect: patient flow; patient experience; patient safety and the wider healthcare system.

Results

Ninety-six articles contributed data to theory development sourced from earlier systematic reviews, updated database searches (Medline, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane DSR & CRCT, DARE, HTA Database, BSC, PsycINFO and SCOPUS) and citation tracking. We developed theories to explain: how staff interpret the streaming system; different roles general practitioners adopt in the emergency department setting (traditional, extended, gatekeeper or emergency clinician) and how these factors influence patient (experience and safety) and organisational (demand and cost-effectiveness) outcomes.

Conclusions

Multiple factors influence the effectiveness of emergency department streaming to general practitioners; caution is needed in embedding the policy until further research and evaluation are available. Service models that encourage the traditional general practitioner approach may have shorter process times for non-urgent patients; however, there is little evidence that this frees up emergency department staff to care for the sickest patients. Distinct primary care services offering increased patient choice may result in provider-induced demand. Economic evaluation and safety requires further research.

PROSPERO registration number

CRD42017069741.

Keywords: emergency service, hospital; primary health care; general practitioners; health services research

Strengths and limitations of this study.

A realist approach to evidence synthesis leads to theory development that explains how and why context links to outcome; contextual factors can then be incorporated into the evidence base to inform healthcare management and policy-making.

We used experts and stakeholders to facilitate the process, help confirm findings and produce a context-specific document in response to emerging issues.

Some studies did not describe how general practitioners worked in adequate depth to identify key mechanisms that led to the outcomes.

We have focused on general practitioners treating patients in emergency department settings relevant to the UK healthcare system; patient demographics and other healthcare professionals working in primary care services may vary and influence the effectiveness of these services.

Background

Worldwide, emergency healthcare systems are under intense pressure from ever-increasing demand.1 Evidence is urgently needed to understand how best to manage this demand while safely achieving the highest standards of care.2 An estimated 10%–43% of patients attending hospital emergency departments could be treated in primary care settings.3–9 In England, this has led to a policy proposal, supported by £100 million of funding (US$130 million), that all emergency departments have a co-located primary care facility, so they are ‘free to care for the sickest patients’.10–12

The UK has a universal healthcare system, the National Health Service (NHS), funded though taxation.13 Primary care is led by general practitioners, community-based doctors with generalist training. General practitioners are described as working in or alongside emergency departments in three main ways: treating patients identified as having primary care type problems in a unit alongside the emergency department including walk-in centres, urgent care centres or out-of-hours services; treating patients inside the emergency department, which may include patients presenting with a wider range of conditions; or working at the front door of the emergency department, redirecting patients with primary care type problems to an alternative primary care service off-site (including pharmacists, opticians or back to their own general practitioner).14 There is little research evidence to guide decisions about how general practitioners most effectively work within these service models. The risk of provider-induced demand, potential patient safety issues and how to recruit a workforce for this initiative are also unclear.15–19 Due to this uncertainty, the main standard-setting body of the NHS (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) does not currently recommend general practitioners work in emergency department settings.20

Research studies addressing these questions are heterogeneous and few are conducted at scale.15–17 This limits the results of traditional synthesis methods to shape practice or policy. Realist methods offer an alternative approach, generating theories to explain why a particular intervention is likely to work, how, for whom, in what circumstances and why.21 These methods identify the important contextual factors that facilitate or inhibit desired intervention outcomes to inform healthcare management and policy-making.22 Urgent and emergency care settings vary in geographical location, the type of patients, the presenting conditions and the experience and disciplines of the healthcare professionals that treat them. We decided that a realist approach, aiming to explain how general practitioners work in or alongside different emergency department settings and why the resultant successes or failures occur, would be more informative than a traditional review approach.

Our research question was, ‘Why and how do general practitioners working in or alongside emergency departments affect: patient attendance and flow; patient experience; patient safety; and the wider healthcare system?’

Method

We followed the realist review methodology to identify mechanisms (M) that explain how or why contexts (C) relate to outcomes (O), to generate theories described as context–mechanism–outcome configurations.21 (Specific terminology is defined in table 1.) Our focus was specifically on general practitioners working in or alongside emergency departments. We used the rapid realist review approach described by Saul et al., which uses experts and stakeholders, to streamline the process and to produce a context-specific product that is useful to policy-makers and responsive to emerging issues; providing evidence and making explicit what is known on the given topic, also articulating the current research gaps.23 We registered our protocol on the PROSPERO database (http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.php?ID=CRD42017069741) and followed RAMESES publication standards for realist reviews.24 The period of study was April to November 2017.

Table 1.

Glossary of terms

| Primary care type problem | A condition that a typical general practitioner in a typical general practice would be expected to manage. |

| Streaming | A system, following brief clinical assessment, to allocate patients to the most appropriate healthcare provider within the emergency department setting.122 |

| Triage | Identifying acuity and prioritising patients on that basis.122 |

| Redirection | ‘Sending people away’ to an appropriate off-site or separately managed service.122 |

| Context (C) | Pre-existing conditions which influence the success or failure of different interventions or programmes.21 123 |

| Mechanism (M) | The intervention and people’s reaction to it; how does it influence their reasoning?21 123 |

| Outcome (O) | Intended and unintended results as a result of a mechanism operating within a context.21 123 |

| Initial theory | An early theory informed by available evidence describing why, how and for whom the intervention is thought to work using a context–mechanism–outcome configuration.21 123 |

| Refined theory | An initial theory that has been refined using primary or secondary evidence.21 123 |

Three reviewers (AC, FD and ME) conducted a scoping exercise with the four UK papers identified in the review by Ramlakhan et al 4 17 25–27 and two policy documents,14 28 to generate initial theories. We then developed and piloted data extraction forms. Our theories were developed at the micro-level (the reasoning processes of general practitioners, emergency department staff and patients), meso-level (staff interactions resulting in department level outcomes) and macro-level (the impact on the wider system).29

We discussed these initial theories with the wider study team of 18 collaborators, including emergency department clinicians, policy-makers, general practitioners, members of the public and methodologists at a study meeting in May 2017. We used them as an expert reference group, to contribute ideas for other possible initial theories and to identify further research papers in peer-reviewed journals and relevant reports in the grey literature. Six members of this group (AP, PA, BAE, BH, JD and ACS) met via teleconference every 6 weeks to discuss findings and guide priority search areas.

We used papers referenced in three previous systematic reviews as a starting point,15–17 and to identify papers published since, we combined search terms used previously.16 17 A combination of free text and Medical Subject Headings terms was used (see online supplementary file 1 for Medline strategy which was adapted for other databases). AC ran the searches on the following databases from 15 June to 4 July 2017: Medline via OVID, Embase, CINAHL, Cochrane DSR & CRCT, DARE, HTA Database, Business Source Complete, PsycINFO and SCOPUS and used EndNote X8 (Clarivate analytics) to export citations from the database searches and identify duplicates. AC screened the titles and abstracts of all identified papers using a checklist, developed and tested in collaboration with FD, which ranked abstracts according to relevance.

bmjopen-2018-024501supp001.pdf (491.8KB, pdf)

We selected studies if they could contribute to the process of theory development at the level of individual data extracts rather than assessing the full text against a set checklist.24 30 We excluded papers that lacked relevance or explanatory power, or were unavailable in English. AC and FD imported data extracts into NVivo V.11 (QRS international) that evidenced how mechanisms (M), influenced by local contexts (C), related to outcomes (O). Quantitative, qualitative or contextual data were extracted from any part of a paper. We continually considered the relevance and rigour of each included piece of evidence during the data extraction and synthesis phases.30 We discussed weekly within the team (AC, FD, ME and AE) how individual data extracts should be used to ensure appropriate inferences were made.30 A quarter of all included articles was read by both reviewers, and the coding process was discussed in detail, to ensure consistency of approach.

We used snowballing techniques (such as searching companion papers and citation tracking) for all included articles. We also searched to identify additional relevant grey literature (including policy documents and opinion pieces) from a variety of sources. The search process was iterative, overlapping with data extraction and analysis, and was directed towards the evidence gaps and finding explanatory information.

We applied Pawson’s reasoning processes,21 to synthesise the evidence and develop our theories. We presented these context-specific developing theories to our expert reference group in November 2017. At this stage, the group recognised that although the review had been useful in theory development, there were limited opportunities for theory testing and refinement due to evidence gaps. Rather than continuing to search the literature, we decided that gathering primary data from our evaluation case study sites in the next phase of our wider ongoing study,31 would give an opportunity for more meaningful testing to derive refined theories.21

Patient and public involvement

Three public contributors (BAE, BH and JH) were co-applicants for the funded research and contributed to the conceptualisation of our wider study, including theory generation through the review.31 They contributed in both meetings described above to ensure that the patient’s perspective was acknowledged and at a stakeholder dissemination event in February 2018.

Results

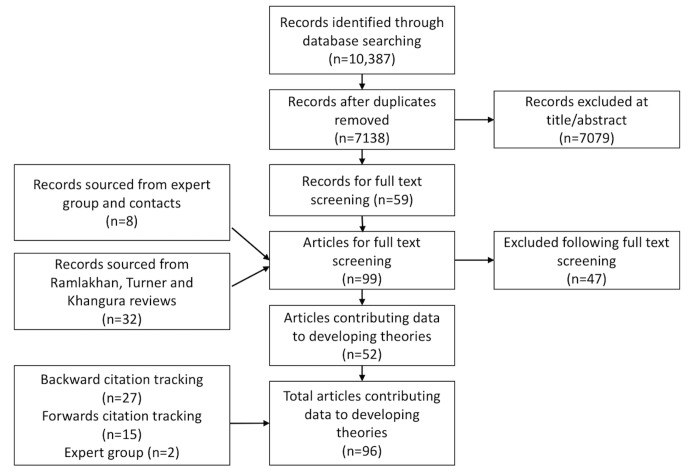

Figure 1 shows the search strategy and results. A total of 96 articles contributed to the developing theories. The articles were largely primary research studies, most from the UK (n=44 articles), with a large contribution from the Netherlands (n=17). Others were from Ireland, Belgium, Switzerland, Sweden, Italy, Finland, Australia, USA, Canada, Singapore and New Zealand. Most described patients identified by the emergency department as having primary care type problems, appropriate for treatment by a general practitioner.

Figure 1.

Search strategy and results.

We synthesised data to develop theories, described using Context (C)–Mechanism (M)–Outcome (O) configurations, to explain: how or why emergency department staff and general practitioners react to guidance to determine which patients are streamed to general practitioners; the role general practitioners may adopt in the emergency department setting (traditional general practitioner, extended general practitioner, gatekeeper or emergency clinician); and how these factors influence patient (experience and safety) and organisational (risk of provider-induced demand and cost-effectiveness) outcomes. These theories are summarised in table 2 with an indication of supporting data. Full details of included articles are listed in online supplementary file 2.

Table 2.

Summary of developing theories and supporting evidence

| Theory | Context (C)–Mechanism (M)–Outcome (O) configuration | Example of supporting extract | Evidence base |

| 1. Effectiveness of the streaming system | General practitioners (GPs) and emergency department (ED) staff use their own personal experience and expectation (C) when interpreting streaming guidance (M) to influence which patients are streamed to GPs (O). | ‘It seems that patients are difficult to classify (for A&E (ED) or walk-in centre GPs or nurse practitioners) on limited information for several reasons: serious conditions can sound minor, and vice versa; conditions can present in various ways; and complaints can have several underlying causes.’ 35 | Data to support theory. 4 14 25 32–40 |

| 2a. Traditional general practitioner (GP) role versus emergency clinician role | When GPs working in the ED maintain a ‘traditional role’ using the same approach taken in the primary care setting (M) to treat patients with primary care problems (C), investigations, admissions and process times will reduce (O). However, if GPs adopt an ‘emergency clinician role’ working as another pair of hands (‘going native’) because of their personal interest or experience or because they feel this is the correct way to work in this setting (M), there will be no difference in the rate of investigations and admissions (O). | ‘I guess our emergency medicine approach is we’re looking for something dreadful and a GP approach is very different in that most of the time they know it’s minor stuff or … moderate stuff that is self-limiting and so … they’re looking to find symptomatic relief and how can we get this patient home and away from hospital.’ (Consultant)38

‘Once they start becoming like everyone else then they stop being like a GP and they don’t necessarily work quickly and effectively which is supposed to be the whole benefit of having them there.’ (Consultant)38 |

Data to support traditional GP role theory 4 5 25 26 38 39 45–52 Limited data to support ED clinician role theory.38 41 |

| 2b. Extended GP role |

GPs in EDs can work in an ‘extended role’ where their skills are directed at specific patient groups including non-urgent paediatric or elderly patients (C), to treat using the usual primary care approach (M), to reduce the use of hospital resources and admissions in these patient groups (O). | ‘During a 6-month pilot scheme which co-located a primary care GP service in a busy paediatric ED, patients seen during the hours when the GP was available were significantly less likely to be admitted, exceed the 4 hours waiting target or leave before being seen, but more likely to receive antibiotics.’5 | Data to support theory for paediatric patients only. 5 28 43 53 66 |

| 2c. Gatekeeper role | GPs can use their generalist skills and knowledge of community resources (M) to redirect patients presenting with primary care problems (C) out of the ED to alternative primary care services off-site for treatment thereby reducing ED attendances (O). | ‘GPs and nurses based in triage identify patients who could be managed more appropriately in primary care as soon as they enter the ED, and redirect them back to primary care services.’ 70 | Limited data to support theory. 70 71 |

| 3. Patient satisfaction | Patients with primary care problems that present to EDs (C) and are seen by GPs, are more satisfied with the care they receive (O) if the experience exceeds expectation (M), but if they do not perceive any difference in the care they received compared with what they expected (M), there is no difference in satisfaction (O). | ‘There were no significant differences in (patient) satisfaction ratings between the three groups of doctors (GPs, Senior House Officers or Registrars).’ 39 | Limited data to support theory. 26 39 45 47 86–90 |

| 4. Safety implications | In EDs where there are delayed patient transfers to wards or inadequate staffing (C) GPs seeing patients with primary care type problems (M), may not free up ED staff to care for the sickest patients (O). | ‘The attribution of overcrowding in ED to attendance by GP-type patients is simplistic; it does not address how patients are processed within ED or how they are transferred to wards later if required.’ 46 | Limited data to support theory. 46 93–99 |

| 5. Risk of provider- induced demand | If patients with primary care type problems present to EDs (C) and are streamed to indistinct primary care services, without patient awareness or choice (M), there is no provider-induced demand (O). However, distinct urgent primary care services may offer convenient access to primary care (M), resulting in provider-induced demand (O). | ‘A&E (ED) has not seen any reduction in their patients. If there is a service, patients will use it. You could have three walk-in centres in the city and all three would be used and you may still not see any dropping in A&E (ED) counts.’ (Manager)102 | Data to support theory. 4 27 54–56 80 102–109 |

| 6. Cost-effectiveness | If there is demand for patients with primary care problems presenting to EDs (C), and they are streamed to on-site GPs and managed using a traditional GP approach (M), the service is cost-effective due to fewer referrals, admissions, investigations and better outcomes compared with usual services (O). | ‘Management of patients with primary care needs in the A&E department by GPs reduced costs with no apparent detrimental effect on outcome.’26 | Limited data to support theory. 26 45 51 |

Theory 1: Effectiveness of the streaming system

General practitioners and emergency department staff use their own personal experience and expectation (C) when interpreting streaming guidance (M) to influence which patients are streamed to general practitioners (O).4 14 25 32–40

Twelve articles supported this theory and indicated how the streaming process itself directly influenced the effectiveness of the general practitioner service in the department. Variable streaming rates were described due to differences in guidelines and also how the guidance was interpreted by emergency department clinical and non-clinical staff of varying experience.32 37 38 40 41 The (streaming) nurse was sometimes described as being unclear which patients general practitioners could deal with,4 25 34–38 or being more familiar with emergency department work so favouring emergency department referral,14 33 35 37–39 even overruling the guidelines if he/she felt that the patient would require specific investigations,35 or admission.33 General practitioners were also noted to over-ride nurse decisions to select patients that suited their own interests or perceived skills.42 Increased general practitioner streaming rates were reported when there was a good relationship between the general practitioners and emergency department nurses,40 and when the general practitioners were directly involved in the streaming process.43 44 The influence of commissioning or leadership was not described.

Theory 2a: Traditional general practitioner role versus emergency clinician role

When general practitioners working in the emergency department maintain a ‘traditional role’ using the same approach taken in the primary care setting (M) to treat patients with primary care problems (C), 38 39 45–48 investigations, admissions and process times will reduce (O). 4 5 25 26 45 47–52 However, if general practitioners adopt an ‘emergency clinician role’ working as another pair of hands (‘going native’) because of their personal interest or experience or because they feel this is the correct way to work in this setting (M), there will be no difference in the rate of investigations and admissions (O). 38 41

The traditional general practitioner approach was described by many authors as a different approach to risk management and diagnostic uncertainty, with less reliance on acute investigations.38 39 46–48 This approach was maintained in a variety of different settings despite full access to investigations—when general practitioners were allocated a separate consulting room mimicking usual general practice,4 25 and also when general practitioners worked in a more fully integrated model, alongside emergency department clinicians.45 47 48 Other articles reported general practitioners managing non-urgent patients in this way to divert attendances from emergency department staff.32 36 37 43 44 53–65

There were limited qualitative data to support the ‘emergency clinician role’ theory.38 An Irish study described an ‘unstructured receptionist-based triage system’ for all patients attending the department (including referrals from primary care) which may have influenced relatively inexperienced general practitioners to adopt a ‘diagnosis driven’ emergency clinician approach.41 The influence of general practitioners’ special interests, experience in emergency medicine or the effect of staff shortages were not described in the literature to affect this potential role shift.

Theory 2b: Extended general practitioner role

General practitioners in emergency departments can work in an ‘extended role’ where their skills are directed at specific patient groups including non-urgent paediatric or elderly patients (C) to treat using the usual primary care approach (M) to reduce the use of hospital resources and admissions in these patient groups (O).5 28 43 53 66

Several paediatric primary studies supported general practitioners treating children triaged as ‘non-urgent’ to divert attendances from the emergency department,43 53 and reduce hospital admissions.5 66 None of the included primary studies described general practitioners specifically treating care home residents or the elderly, as suggested in a policy document.28

Smith et al reported an increase in antibiotic prescribing for children by general practitioners,5 which could potentially be an unintended consequence of the ‘traditional role’ approach; relying on clinical acumen and treating a suspected source of infection rather than admitting, investigating and observing the patient to confirm the diagnosis. An increase in prescribing by general practitioners was not described in other UK studies,4 25 but was reported (but not the drugs involved) in both Irish studies that involved more junior general practitioners.41 45

There was evidence that general practitioners working in or alongside emergency departments see a different cohort of patients to that in usual general practice, with more acutely unwell patients,38 67 and minor injuries,4 6 35–38 68 69 which could also be described as an ‘extended role.’ There was no evidence in the included studies for the implications of this on their skillset, learning needs, cognition processes or risk management behaviour.

Theory 2c: Gatekeeper role

General practitioners can use their generalist skills and knowledge of community resources (M) to redirect patientspresenting with primary care problems (C) out of the emergency department to alternative primary care services off-site for treatment thereby reducing emergency department attendances (O). 70 71

There were limited data to support this theory with two London case study reports identified in an ‘accident and emergency avoidance scheme' document, describing 228 patients in total.70 72 There was evidence that general practitioners were more likely to redirect patients after an initial assessment than senior emergency department nurses, but only from a sample of 384 patients that self-presented to a London emergency department.71

Due to a lack of evidence for general practitioners performing a redirection role, following realist methodology, we also included studies involving redirection of patients from the emergency department by a senior emergency department clinician or nurse to gain understanding about how and why the system worked. Many of these articles described reduced emergency department attendances.73–79 Previous UK guidance has cautioned against redirecting patients from emergency departments due to the risk of delayed assessment and treatment, especially in vulnerable patient groups including the homeless or those with mental health problems who may not go on to receive the care they need.14 28 Studies from Scotland, Sweden and the USA that described a comprehensive assessment process, including measurement of vital signs and a focused history, reported that their redirection policies were safe and worked well to reduce attendances.74 76 78–80 Other US studies, that did not describe the assessment process, reported adverse events when children were redirected without treatment.81 82 The low sensitivity of triage criteria to identify those that needed urgent care,83 especially infants84 and failure to validate a predictive model for refusal of care,85 were highlighted in other studies. The influence of governance processes restricting redirection of patients by some staff to services off-site was not described in these articles.

Theory 3: Patient satisfaction

Patients with primary care problems that present to emergency departments (C) and are seen by general practitioners, are more satisfied with the care they receive (O) if the experience exceeds expectation (M), but if they do not perceive any difference in the care they received compared with what they expected (M), there is no difference in satisfaction (O).26 39 45 47 86–90

Data to support this theory were limited, with an increase in satisfaction by patients seen by general practitioners generally associated with shorter waiting times,47 86 rather than expectation of investigation and treatment.39 The general practitioners were sometimes supernumerary which may have contributed towards this.26 47 Other studies demonstrated that general practitioners focused more on patient education and counselling than emergency department clinicians with some improvement in satisfaction rates.91 92 In more fully integrated models, the patient was often unaware that they had seen a general practitioner rather than an emergency department clinician and there was no difference in patient satisfaction.26 39 45 87

Theory 4: Safety implications

In emergency departments where there are delayed patienttransfers to wards or inadequate staffing (C) general practitioners seeing patients with primary care type problems (M), may not free up emergency department staff to care for the sickest patients (O). 46 93–99

There was a lack of evidence that general practitioners working in or alongside emergency departments directly or indirectly improved care and safety for the sickest patients. A reduction in time spent in the department for patients requiring emergency department level care was suggested in a UK simulation and modelling study,93 and an Australian study also reported a reduced mean time taken to see more seriously ill patients but this was not seen on sites that described provider-induced demand.94 A Canadian study of over 4 million patient visits reported that low complexity emergency department patients did not increase time to first physician contact for high-complexity patients.95 Other studies also described how diverting non-urgent patients did not improve the high-level care required by others, and that influences such as delayed transfer of patients to the ward were more likely to contribute to overcrowding.46 96–98 Staffing levels, staff attitude and the time of day were independent factors described to affect emergency department flow.99

There were minimal data on the safety implications of general practitioners working in emergency department settings. Several studies used emergency department re-attendance as a marker of safety, with no increase among patients seen by general practitioners compared with usual emergency department staff.26 27 45 100 101 Annual death rates were used as another crude marker in a Dutch study, with no significant increase following the introduction of an out-of-hours primary care physician cooperative.55 Shared or separate governance systems between general practitioners and the emergency department were rarely described in the primary studies, providing no evidence for best practice. For general practitioners working inside the emergency department good communication and integration were described in some studies,4 26 38 67 with anecdotal reports of poor communication negatively affecting care quality in others.32

Theory 5: Risk of provider-induced demand

If patients with primary care type problems present to emergency departments (C) and are streamed to indistinct primary care services, without patient awareness or choice (M), there is no provider-induced demand (O). 4 27 54 55 However, distinct urgent primary care services may offer convenient access to primary care (M), resulting in provider-induced demand (O).56 80 102–109

Four articles described fully integrated models, where non-urgent patients were streamed directly to general practitioners inside the emergency department without provider-induced demand.4 27 54 55 Here, there was no patient choice offered and often a lack of patient awareness. Another 10 articles described distinct urgent primary care services, often in separate buildings outside the emergency departments, as duplicating services and creating their own demand, increasing patient presentation rates directly or at nearby services, rather than relieving pressure on the emergency department.80 102–112

Theory 6: Cost-effectiveness

If there is demand for patients with primary care problems presenting to emergency departments (C), and they are streamed to on-site general practitioners and managed using a traditional general practitioner approach (M), the service is cost-effective due to fewer referrals, admissions, investigations and better outcomes compared with usual services (O).26 45 51

Data to support this theory were limited, but supported by three economic evaluations (UK, Ireland and the Netherlands) where non-urgent patients were streamed to general practitioners during normal daytime hours.26 45 51 The comparator was ‘business as usual’ with no general practitioner service. The UK and Irish studies were published in 1996 and may not represent current emergency department staffing models. No articles were identified that studied the relative cost-effectiveness of general practitioners redirecting patients from the emergency department for care elsewhere. A 5-year US redirection study calculated cost-effectiveness from the perspective of the institution but did not include costs for treatment incurred elsewhere,76 while another US study calculated that marginal costs for non-urgent visits to the emergency department were low and that cost savings from diverting visits may be less than widely believed.113 However the USA has a complex health system, with a significant majority of the population covered by private health insurance alongside state-funded Medicare, Medicaid, the federally funded Veterans Health Administration, and a substantial uninsured population—all factors which could influence access to emergency departments and the type of care needed and delivered.

Three other studies of ‘out-of-hours’ patients did not find the addition of a primary care service to be cost saving. One Dutch study, with an off-site general practitioner cooperative, reported parents refusing to take their children to a different location, or the (streaming) nurse overruling the policy.33 Another 12-year-old Dutch study showed no change in costs, despite a substantial reduction in emergency department attendances, due to regulations dictating minimum staffing levels to cope with major trauma.65 The Dutch healthcare system has a complex funding structure with a mix of social and private insurance and this may influence incentives and disincentives to access emergency departments. An Australian primary care out-of-hours service closed because patients chose to attend an equally accessible general practice service that existed nearby.40

Wider system implications

Limited evidence from the included studies prevented us from developing theories on wider system implications. There were no reports of emergency department clinicians being encouraged to adopt a more conservative approach, as a result of working alongside general practitioners, but some reports of general practitioners in management positions influencing system changes.114 115 The potential reduction in learning opportunities for junior doctors was highlighted in two articles.52 67 There was limited evidence that working in an emergency department setting led to increased job satisfaction for some UK general practitioners with a special interest in emergency care.38 115 However, reduced satisfaction was also described because the job was outside the scope of usual general practice,38 50 possibly contributing towards recruitment problems.38 116

Discussion

Principal findings

We developed theories using data from 96 articles to describe the mechanisms by which general practitioner services are linked to outcomes: about the streaming process itself; the role general practitioners may adopt in the emergency department setting; and the effects of these on the patient (experience and safety) and the organisation (risk of provider-induced demand and costs). There was little evidence that general practitioners in emergency departments directly or indirectly affected the care and throughput of the sickest patients. Distinct units, advertising these services, may offer an attractive alternative to primary care and result in provider-induced demand. The literature describing economic impacts of general practitioners in emergency departments comes from different countries, with different funding systems and spans over 20 years, limiting conclusions.

Strengths and limitations

Heterogeneous studies involving general practitioners working in or alongside emergency departments do not suit traditional systematic review methods. We have conducted the first realist review in this area, using methods that are gaining prominence in healthcare research.117 118 The rapid realist review approach is appropriate in relation to the rapidly evolving NHS policy on emergency department use of general practitioners,10–12 showing where such policies may be reinforced or refuted by the evidence available.23 A weakness of our study was the time constraint on our project but the expert group mitigated this, and enabled us to focus and direct our research.23 Some studies did not describe the intervention in adequate depth to help facilitate the identification of key mechanisms. Single-site heterogeneous studies and the nature of different healthcare and funding systems limited international comparability.21

The wide estimates of patients presenting with primary care type problems to emergency departments highlight the difficulty in defining and identifying this target patient group and therefore the effectiveness of these services in different local contexts. We have focused on general practitioners working in or alongside emergency departments but in the UK this role has evolved to include nurses and advanced care practitioners from other disciplines, often due to staffing and recruitment challenges. These challenges may be mirrored in emergency department-based services, affecting variation between services and need to be considered in further research.

Comparison with other reviews

Before our review, the largest review to date by Ramlakhan et al. 17 included 20 papers and described provider-induced demand, poor evidence for improved emergency department throughput and minimal economic impact.17 The Goncalves-Bradley et al. Cochrane review of four studies, published in 2018, highlighted inconsistent results and a lack of evidence on safety.18 We also found evidence of provider-induced demand in distinct primary care units but less so in more fully integrated service models where patients lacked awareness that they had been directed to primary care services.4 54 55 We found that patients with primary care problems may have reduced process times if treated by general practitioners adopting a traditional role but there was a lack of evidence for an improvement in overall throughput for patients in the department. There was also a lack of evidence on the impact on general practitioners’ cognition processes and risk-taking behaviour when treating a different group of patients to that seen in usual general practice and the safety implications of this.

Policy implications

The global health priority recently given to Universal Health Coverage,119 and the attention being given to the 40th anniversary of the Alma-Ata declaration,120 moves to centre stage the design of primary healthcare systems, particularly their capacity and capability to respond to urgent care needs. Internationally, emergency departments are exploring options on how to run more efficiently and safely. Our theories, informed by literature from 13 countries, allow policy-makers to make more considered judgements about their relevance to their own contexts for service provision. The UK has already commissioned further research in this area, funded by the National Institute for Health Research (HS&DR Projects: 15/145/0431 and 15/145/06121), the former collecting primary data to further test and refine these theories.

Conclusion

The effectiveness of emergency department streaming to primary care services may be influenced by how staff interpret the streaming system and the roles general practitioners adopt. Caution is needed in embedding the policy until further research and evaluation are available. Service models that encourage the traditional general practitioner approach may have shorter process times for non-urgent patients; however, there is little evidence that this frees up emergency department staff to care for the sickest patients. Distinct primary care services offering increased patient choice may result in provider-induced demand. Economic evaluation and safety requires further research.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to our public contributors, Barbara Harrington and Julie Hepburn and to Damon Berridge for contributing to discussions. Also to Faris Hussain for assisting with citation tracking.

Footnotes

Contributors: AC, FD, PA, ACS, MWC, LD, JD, BAE, PDH, TCH, AP, TR, AS, HS and AE are co-applicants on the wider project and were involved in the conceptualisation of the study. AC, FD, ME, PA, ACS, MWC, JD, BAE, PDH, TCH, AP, TR, AS, HS and AE contributed as part of the expert group in team meetings in May and/or November 2017. AC and FD planned the synthesis approach with input from AE. ME contributed to data analysis and interpretation in the pilot work and weekly team meetings. The core review team (AP, PA, BAE, JD and ACS) met via teleconference every 6 weeks to discuss findings and guide further searches. AC conducted the database searches. AC and FD extracted data extracts and were involved in the synthesis process, meeting weekly with AE and ME to discuss findings. AC prepared the first draft of the manuscript which was reviewed and critically appraised by all authors, who approved the final version and agree to be accountable for this work.

Funding: This study is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HS&DR Project 15/145/04.

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional unpublished data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. What’s going on with a&e waiting times? The king’s fund. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/projects/urgent-emergency-care/urgent-and-emergency-care-mythbusters.

- 2. Keogh B. Transforming urgent and emergency services in England: Urgent and emergecy care review. 2013. http://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/keogh-review/Pages/urgent-and-emergency-care-review.aspx.

- 3. Emergency departments: More useful than the official data suggests The College of Emergency Medicine. 2014. http://www.kingstoned.org/uploads/2/4/0/2/24023085/ca_past_paper.pdf.

- 4. Ward P, Huddy J, Hargreaves S, et al. Primary care in London: an evaluation of general practitioners working in an inner city accident and emergency department. J Accid Emerg Med 1996;13:11–15. 10.1136/emj.13.1.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Smith L, Narang Y, Ibarz Pavon AB, et al. To GP or not to GP: a natural experiment in children triaged to see a GP in a tertiary paediatric emergency department (ED). BMJ Qual Saf 2018;27:521–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Dale J, Green J, Reid F, et al. Primary care in the accident and emergency department: I. Prospective identification of patients. BMJ 1995;311:423–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Coleman P, Irons R, Nicholl J. Will alternative immediate care services reduce demands for non-urgent treatment at accident and emergency? Emerg Med J 2001;18:482–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nagree Y, Camarda V, Fatovich D, et al. Quantifying the proportion of general practice and low-acuity patients in the emergency department. 2013;198:612–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Thompson MI, Lasserson D, McCann L, et al. Suitability of emergency department attenders to be assessed in primary care: survey of general practitioner agreement in a random sample of triage records analysed in a service evaluation project. BMJ open 2013;3:e003612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Acute and emergency care: prescribing the remedy. 2014https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/news/acute-and-emergency-care-prescribing-remedy.

- 11. A&E departments to get more funding - GOV.UK. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/ae-departments-to-get-more-funding.

- 12. Next steps on the NHS five year forward view. 2017. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/NEXT-STEPS-ON-THE-NHS-FIVE-YEAR-FORWARD-VIEW.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13. The principles and values of the NHS in England Department of Health. https://www.nhs.uk/NHSEngland/thenhs/about/Pages/nhscoreprinciples.aspx.

- 14. Carson D, Clay H, Stern R. Primary care and emergency departments. Primary Care Foundation 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Khangura JK, Flodgren G, Perera R, et al. Primary care professionals providing non-urgent care in hospital emergency departments. The Cochrane Library 2012;53:1689–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Turner J, Coster J, Chambers D, et al. What evidence is there on the effectiveness of different models of delivering urgent care? A rapid review. Heal Serv Deliv Res 2015;3:1–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ramlakhan S, Mason S, O’Keeffe C, et al. Primary care services located with EDs: a review of effectiveness. Emerg Med J 2016;33:495–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Goncalves-Bradley D, Khangura JK, Flodgren G, et al. Primary care professionals providing non-urgent care in hospital emergency departments. The Cochrane Library 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Baird B, Charles A, Honeyman M, et al. Understanding pressures in general practice The King’s Fund. 2016. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/files/kf/field/field_publication_file/Understanding-GP-pressures-Kings-Fund-May-2016.pdf.

- 20. NICE guideline GPs within or on the same site as emergency departments, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pawson R, Tilley N. Realistic evaluation: SAGE Publications, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lavis J, Davies H, Oxman A, et al. Towards systematic reviews that inform health care management and policy-making. J Health Serv Res Policy 2005;10 Suppl 1:35–48. 10.1258/1355819054308549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Saul JE, Willis CD, Bitz J, et al. A time-responsive tool for informing policy making: rapid realist review. Implement Sci 2013;8:103 10.1186/1748-5908-8-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, et al. RAMESES publication standards: realist syntheses. BMC medicine 2013;11:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dale J, Green J, Reid F, et al. Primary care in the accident and emergency department: II. Comparison of general practitioners and hospital doctors. BMJ 1995;311:427–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Dale J, Lang H, Roberts JA, et al. Cost effectiveness of treating primary care patients in accident and emergency: a comparison between general practitioners, senior house officers, and registrars. BMJ 1996;312:1340–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Salisbury C, Hollinghurst S, Montgomery A, et al. The impact of co-located NHS walk-in centres on emergency departments. Emerg Med J 2007;24:265–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Primary Care in Emergency Departments A guide to good practice. NHS Interim Mangement and Support. 2015. http://www.nhsimas.nhs.uk/fileadmin/Files/IST/Emergency_care_conference_2014/Primary_Care_in_A_E_Guidance_Feb_2015.pdf.

- 29. Barach P, Johnson JK. Understanding the complexity of redesigning care around the clinical microsystem. Qual Saf Health Care 2006;15 Suppl 1:10–16. 10.1136/qshc.2005.015859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pawson R. Evidence-based policy. SAGE Publications, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Edwards A. Evaluating effectiveness, safety, patient experience and system implications of different models of using GPs in or alongside Emergency Departments. https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1514504/#/

- 32. Thijssen WA, Wijnen-van Houts M, Koetsenruijter J, et al. The impact on emergency department utilization and patient flows after integrating with a general practitioner cooperative: an observational study. Emerg Med Int 2013;2013:1–8 http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=3814098&tool=pmcentrez&rendertype=abstract 10.1155/2013/364659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Veen M, ten Wolde F, Poley MJ, et al. Referral of nonurgent children from the emergency department to general practice: compliance and cost savings. Eur J Emerg Med 2012;19:14–19. 10.1097/MEJ.0b013e32834727d4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bickerton J, Dewan V, Allan T. Streaming A&E patients to walk-in centre services. Emerg Nurse 2005;13:20–4. 10.7748/en2005.06.13.3.20.c1047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van der Straten LM, van Stel HF, Spee FJ, et al. Safety and efficiency of triaging low urgent self-referred patients to a general practitioner at an acute care post: an observational study. Emerg Med J 2012;29:877–81. 10.1136/emermed-2011-200539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chmiel C, Wang M, Sidler P, et al. Implementation of a hospital-integrated general practice-a successful way to reduce the burden of inappropriate emergency-department use. Swiss Med Wkly 2016;146:w14284 10.4414/smw.2016.14284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. van Gils-van Rooij ESJ, Meijboom BR, Broekman SM, et al. Is patient flow more efficient in Urgent Care Collaborations?. Eur J Emerg Med 2018;25:58–64. 10.1097/MEJ.0000000000000412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ablard S, O’Keeffe C, Ramlakhan S, et al. Primary care services co-located with Emergency Departments across a UK region: early views on their development. Emerg Med J 2017;34:672–6. 10.1136/emermed-2016-206539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Dale J. Primary care in accident and emergency departments : The cost effectiveness and applicability of a new model of care. 1998:1–242.

- 40. Bolton P, Thompson L. The reasons for, and lessons learned from, the closure of the Canterbury GP After-Hours Service. Aust Health Rev 2001;24:66–73. 10.1071/AH010066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Gibney D, Murphy AW, Barton D, et al. Randomized controlled trial of general practitioner versus usual medical care in a suburban accident and emergency department using an informal triage system. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:43–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Freeman GK, Meakin RP, Lawrenson RA, et al. Primary care units in A&E departments in North Thames in the 1990s: initial experience and future implications. Br J Gen Pract 1999;49:107–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Gnani S, Morton S, Ramzan F, et al. Healthcare use among preschool children attending GP-led urgent care centres: a descriptive, observational study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010672 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Cowling TE, Ramzan F, Ladbrooke T, et al. Referral outcomes of attendances at general practitioner led urgent care centres in London, England: retrospective analysis of hospital administrative data. Emerg Med J 2016;33:200–7. 10.1136/emermed-2014-204603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Murphy AW, Bury G, Plunkett PK, et al. Randomised controlled trial of general practitioner versus usual medical care in an urban accident and emergency department: process, outcome, and comparative cost. BMJ 1996;312:1135–42. 10.1136/bmj.312.7039.1135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wilson H. Co-locating primary care facilities within emergency departments: brilliant innovation or unwelcome intervention into clinical care? N Z Med J 2005;118:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Boeke AJ, van Randwijck-Jacobze ME, de Lange-Klerk EM, et al. Effectiveness of GPs in accident and emergency departments. Br J Gen Pract 2010;60:e378–e384. 10.3399/bjgp10X532369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang M, Wild S, Hilfiker G, et al. Hospital-integrated general practice: a promising way to manage walk-in patients in emergency departments. J Eval Clin Pract 2014;20:20–6. 10.1111/jep.12074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Huibers L, Thijssen W, Koetsenruijter J, et al. GP cooperative and emergency department: an exploration of patient flows. J Eval Clin Pract 2013;19:243–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01806.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kool RB, Homberg DJ, Kamphuis HC. Towards integration of general practitioner posts and accident and emergency departments: a case study of two integrated emergency posts in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:225 10.1186/1472-6963-8-225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Bosmans JE, Boeke AJ, van Randwijck-Jacobze ME, et al. Addition of a general practitioner to the accident and emergency department: a cost-effective innovation in emergency care. Emerg Med J 2012;29:192–6. 10.1136/emj.2010.101949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hess S, Sidler P, Chmiel C, et al. Satisfaction of health professionals after implementation of a primary care hospital emergency centre in Switzerland: A prospective before-after study. Int Emerg Nurs 2015;23:286–93. 10.1016/j.ienj.2015.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Clancy E, Mayo A. Launching a social enterprise see-and-treat service. Emerg Nurse 2009;17:22–4. 10.7748/en2009.06.17.3.22.c7088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. van Uden CJ, Crebolder HF. Does setting up out of hours primary care cooperatives outside a hospital reduce demand for emergency care? Emerg Med J 2004;21:722–3. 10.1136/emj.2004.016071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. van Uden CJ, Winkens RA, Wesseling G, et al. The impact of a primary care physician cooperative on the caseload of an emergency department: the Maastricht integrated out-of-hours service. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:612–7. 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0091.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. O’Kelly FD, Teljeur C, Carter I, et al. Impact of a GP cooperative on lower acuity emergency department attendances. Emerg Med J 2010;27:770–3. 10.1136/emj.2009.072686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. van Gils-van Rooij ES, Yzermans CJ, Broekman SM, et al. Out-of-hours care collaboration between general practitioners and hospital emergency departments in the Netherlands. J Am Board Fam Med 2015;28:807–15. 10.3122/jabfm.2015.06.140261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. van Veelen MJ, van den Brand CL, Reijnen R, et al. Effects of a general practitioner cooperative co-located with an emergency department on patient throughput. World J Emerg Med 2016;7:270–3. 10.5847/wjem.j.1920-8642.2016.04.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Arain M, Campbell MJ, Nicholl JP. Impact of a GP-led walk-in centre on NHS emergency departments. Emerg Med J 2015;32:295–300. 10.1136/emermed-2013-202410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. van Uden CJT, Winkens RAG, Wesseling GJ, et al. Use of out of hours services: a comparison between two organisations. Emerg Med J 2003;20:184–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Johnson SJ. Evidence for primary care services at A&E. BMJ 2015;350:h3352 10.1136/bmj.h3352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Grant C, Nicholas R, Moore L, et al. An observational study comparing quality of care in walk-in centres with general practice and NHS Direct using standardised patients. BMJ 2002;324:1556 10.1136/bmj.324.7353.1556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Schols AM, Stevens F, Zeijen CG, et al. Access to diagnostic tests during GP out-of-hours care: A cross-sectional study of all GP out-of-hours services in the Netherlands. Eur J Gen Pract 2016;22:176–81. 10.1080/13814788.2016.1189528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Posocco A, Scapinello MP, De Ronch I, et al. Role of out of hours primary care service in limiting inappropriate access to emergency department. Intern Emerg Med 2018;13:549–55. 10.1007/s11739-017-1679-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. van Uden CJ, Ament AJ, Voss GB, et al. Out-of-hours primary care. Implications of organisation on costs. BMC Fam Pract 2006;7:29 10.1186/1471-2296-7-29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Gritz A, Sen A, Hiles S, et al. More under-fives now seen in urgent care centre than a&e-should we shift our focus? Archives of Disease in Childhood. (Annual Conference of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health, RCPCH. United Kingdom, 2016. 101; http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=emed18&NEWS=N&AN=612211417. [Google Scholar]

- 67. Morton S, Ignatowicz A, Gnani S, et al. Describing team development within a novel GP-led urgent care centre model: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e010224 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Giesen P, Franssen E, Mokkink H, et al. Patients either contacting a general practice cooperative or accident and emergency department out of hours: a comparison. Emerg Med J 2006;23:731–4. 10.1136/emj.2005.032359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chmiel C, Huber CA, Rosemann T, et al. Walk-ins seeking treatment at an emergency department or general practitioner out-of-hours service: a cross-sectional comparison. BMC Health Serv Res 2011;11:94 10.1186/1472-6963-11-94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Proctor N, Woodward M, Partnership HL. A & E Avoidance Schemes across London A rapid review of good practice examples. 2016.

- 71. Harris T, McDonald K. How do clinicians with different training backgrounds manage walk-in patients in the ED setting?. Emerg Med J 2014;31:975–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Begum F, Khan H, Moss P. Solving the A & E crisis using GP lead triage and redirection Evaluation of GP-lead service to identify and re-direct patients from A & E to primary care services83. 2016. Solving the A%26E crisis using GP lead triage and redirection_0.pdf https://www.myhealth.london.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/30.

- 73. Hansagi H, Carlsson B, Olsson M, et al. Trial of a method of reducing inappropriate demands on a hospital emergency department. Public Health 1987;101:99–105. 10.1016/S0033-3506(87)80046-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Rivara F, Wall H, Worley P, et al. Pediatric nurse triage: it’s efficacy, safety and implications for care. J Pediatr Heal Care 1991;5:291–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Derlet RW, Nishio D, Cole LM, et al. Triage of patients out of the emergency department: three-year experience. Am J Emerg Med 1992;10:195–9. 10.1016/0735-6757(92)90207-E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Derlet RW, Kinser D, Ray L, et al. Prospective identification and triage of nonemergency patients out of an emergency department: a 5-year study. Ann Emerg Med 1995;25:215–23. 10.1016/S0196-0644(95)70327-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. McGugan EA, Morrison W. Primary care or A&E? A study of patients redirected from an accident & emergency department. Scott Med J 2000;45:144–6. 10.1177/003693300004500505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Ellbrant J, Åkeson J, Åkeson PK. Pediatric emergency department management benefits from appropriate early redirection of nonurgent visits. Pediatr Emerg Care 2015;31:1–100. 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Bentley JA, Thakore S, Morrison W, et al. Emergency Department redirection to primary care: a prospective evaluation of practice. Scott Med J 2017;62:2–10. 10.1177/0036933017691675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Anantharaman V. Impact of health care system interventions on emergency department utilization and overcrowding in Singapore. Int J Emerg Med 2008;1:11–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Shaw KN, Selbst SM, Gill FM. Indigent children who are denied care in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 1990;19:59–62. 10.1016/S0196-0644(05)82144-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Gadomski AM, Perkis V, Horton L, et al. Diverting managed care Medicaid patients from pediatric emergency department use. Pediatrics 1995;95:170–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Lowe RA, Bindman AB, Ulrich SK, et al. Refusing care to emergency department of patients: evaluation of published triage guidelines. Ann Emerg Med 1994;23:286–93. 10.1016/S0196-0644(94)70042-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. van Veen M, Steyerberg EW, Lettinga L, et al. Safety of the Manchester Triage System to identify less urgent patients in paediatric emergence care: a prospective observational study. Arch Dis Child 2011;96:513–8. 10.1136/adc.2010.199018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Birnbaum A, Gallagher J, Utkewicz M, et al. Failure to validate a predictive model for refusal of care to emergency-department patients. Acad Emerg Med 1994;1:213–7. 10.1111/j.1553-2712.1994.tb02434.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Arain M, Nicholl J, Campbell M. Patients’ experience and satisfaction with GP led walk-in centres in the UK; a cross sectional study. BMC health services research 2013;13:142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Chalder M, Montgomery A, Hollinghurst S, et al. Comparing care at walk-in centres and at accident and emergency departments: an exploration of patient choice, preference and satisfaction. Emerg Med J 2007;24:260–4. 10.1136/emj.2006.042499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Hunter C, Chew-Graham C, Langer S, et al. A qualitative study of patient choices in using emergency health care for long-term conditions: the importance of candidacy and recursivity. Patient Educ Couns 2013;93:335–41. 10.1016/j.pec.2013.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Rajpar SF, Smith MA, Cooke MW. Study of choice between accident and emergency departments and general practice centres for out of hours primary care problems. J Accid Emerg Med 2000;17:18–21. 10.1136/emj.17.1.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Hutchison B, Østbye T, Barnsley J, et al. Patient satisfaction and quality of care in walk-in clinics, family practices and emergency departments: the Ontario Walk-In Clinic Study. CMAJ 2003;168:977–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Dale J, Sandhu H, Lall R, et al. The patient, the doctor and the emergency department: a cross-sectional study of patient-centredness in 1990 and 2005. Patient Educ Couns 2008;72:320–9. 10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Sandhu H, Dale J, Stallard N, et al. Emergency nurse practitioners and doctors consulting with patients in an emergency department: a comparison of communication skills and satisfaction. Emerg Med J 2009;26:400–4. 10.1136/emj.2008.058917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Lengu D, Kobbacy K, Sapountzis S, et al. Application of simulation And Modelling In Managing Unplanned Healthcare Demand Conference paper University of salford, manchester. 2012. http://usir.salford.ac.uk/29360/1/D_Lengu_et_al_-_Application_of_simulation_and_modelling_in_managing_unplanned_healthcare_demand.pdf.

- 94. Sharma A, Inder B. Impact of co-located general practitioner (GP) clinics and patient choice on duration of wait in the emergency department. Emerg Med J 2011;28:658–61. 10.1136/emj.2009.086512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Schull MJ, Kiss A, Szalai JP. The effect of low-complexity patients on emergency department waiting times. Ann Emerg Med 2007;49:257–64. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.06.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Vertesi L. Does the Canadian Emergency Department Triage and Acuity Scale identify non-urgent patients who can be triaged away from the emergency department?. CJEM 2004;6:337–42. 10.1017/S1481803500009611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Richardson DB, Mountain D. Myths versus facts in emergency department overcrowding and hospital access block. Med J Aust 2009;190:369–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Allen P, Cheek C, Foster S, et al. Low acuity and general practice-type presentations to emergency departments: a rural perspective. Emerg Med Australas 2015;27:113–8. 10.1111/1742-6723.12366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. O’Cathain A, Knowles E, Turner J, et al. Variation in avoidable emergency admissions: multiple case studies of emergency and urgent care systems. J Health Serv Res Policy 2016;21:5–14. 10.1177/1355819615596543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Murphy AW, Plunkett PK, Bury G, et al. Effect of patients seeing a general practitioner in accident and emergency on their subsequent reattendance: cohort study. BMJ 2000;320:903–4. 10.1136/bmj.320.7239.903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Doran KM, Colucci AC, Hessler RA, et al. An intervention connecting low-acuity emergency department patients with primary care: effect on future primary care linkage. Ann Emerg Med 2013;61:312–21. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2012.10.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Arain M, Baxter S, Nicholl JP. Perceptions of healthcare professionals and managers regarding the effectiveness of GP-led walk-in centres in the UK. BMJ Open 2015;5:e008286 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Kork A-A, Vakkuri J. Improving access and managing healthcare demand with walk-in clinic. International Journal of Public Sector Management 2016;29:148–63. 10.1108/IJPSM-07-2015-0137 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Greenfield G, Ignatowicz A, Gnani S, et al. Staff perceptions on patient motives for attending GP-led urgent care centres in London: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2016;6:e007683 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Tammes P, Morris RW, Brangan E, et al. Exploring the relationship between general practice characteristics, and attendance at walk-in centres, minor injuries units and EDs in England 2012/2013: a cross-sectional study. Emerg Med J 2016;33:702–8. 10.1136/emermed-2015-205339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Colliers A, Remmen R, Streffer ML, et al. Implementation of a general practitioner cooperative adjacent to the emergency department of a hospital increases the caseload for the GPC but not for the emergency department. Acta Clin Belg 2017;72:49–54. 10.1080/17843286.2016.1245936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Krakau I, Hassler E. Provision for clinic patients in the ED produces more nonemergency visits. Am J Emerg Med 1999;17:18–20. 10.1016/S0735-6757(99)90006-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Hsu RT, Lambert PC, Dixon-Woods M, et al. Effect of NHS walk-in centre on local primary healthcare services: before and after observational study. BMJ 2003;326:530 10.1136/bmj.326.7388.530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Maheswaran R, Pearson T, Jiwa M. Repeat attenders at National Health Service walk-in centres - a descriptive study using routine data. Public Health 2009;123:506–10. 10.1016/j.puhe.2009.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Salisbury C, Chalder M, Scott TM, et al. What is the role of walk-in centres in the NHS?. BMJ 2002;324:399–402. 10.1136/bmj.324.7334.399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Desborough J, Parker R, Forrest L. Development and implementation of a nurse-led walk-in centre: evidence lost in translation?. J Health Serv Res Policy 2013;18:174–8. 10.1177/1355819613488574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Pope C, Chalder M, Moore L, et al. What do other local providers think of NHS walk-in centres? Results of a postal survey. Public Health 2005;119:39–44. 10.1016/j.puhe.2003.12.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Williams RM. The costs of visits to emergency departments. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 1996;334:642–6. 10.1056/NEJM199603073341007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Chew-Graham C, Rogers A, May C, et al. A new role for the general practitioner? Reframing ’inappropriate attenders' to inappropriate services. Primary Health Care Research and Development 2004;5:60–7. 10.1191/1463423604pc188oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Dale J, Russell R, Harkness F, et al. Extended training to prepare GPs for future workforce needs: a qualitative investigation of a 1-year fellowship in urgent care. Br J Gen Pract 2017;67:e659–e667. 10.3399/bjgp17X691853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Van den Heede K, Quentin W, Dubois C, et al. The 2016 proposal for the reorganisation of urgent care provision in Belgium: A political struggle to co-locate primary care providers and emergency departments. Health Policy 2017;121:339–45. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2017.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Greenhalgh T, Humphrey C, Hughes J, et al. How do you modernize a health service? A realist evaluation of whole-scale transformation in london. Milbank Q 2009;87:391–416. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00562.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Gillespie BM, Marshall A. Implementation of safety checklists in surgery: a realist synthesis of evidence. Implement Sci 2015;10:137 10.1186/s13012-015-0319-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Report of the Expert Consultation on Primary Care Systems Profiles & Performance (Primasys). The Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research 2015:0–34. [Google Scholar]

- 120.Declaration of Alma-Ata. 1978. http://www.who.int/publications/almaata_declaration_en.pdf

- 121. Benger J. General Practitioners and Emergency Departments (GPED): Efficient Models of Care. https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1514506/#/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 122. RCEM: Initial Assessment of Emergency Department Patients. 2017. Intial Assessment (Feb 2017).pdf https://www.rcem.ac.uk/docs/SDDC.

- 123. Rycroft-Malone J, Burton CR, Williams L, et al. Improving skills and care standards in the support workforce for older people: a realist synthesis of workforce development interventions NIHR HS&DR. 2016. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK355884/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK355884.pdf. [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024501supp001.pdf (491.8KB, pdf)