Abstract

Objectives

The interaction between positive and negative social support as well as each domain of social support and income on depressive symptom has not been much explored. We aimed to examine the associations of positive and negative social support with the risk of depressive symptoms among urban-dwelling adults in Korea, focusing on those interaction effects.

Design

We used the first wave of a large-scale cohort study called The Health Examinees-Gem Study. Positive and negative support scores ranged between 0 and 6; the variables were then categorised into low, medium, and high groups. A two-level random intercept linear regression model was used, where the first level is individual and the second is the community. We further tested for interactions between each domain of social supports and household income.

Setting

A survey conducted at 38 health examination centres and training hospitals in major Korean cities and metropolitan areas during 2009–2010.

Participants

21 208 adult men and women aged between 40 and 69 in Korea (mean age: 52.6, SD: 8.0).

Outcome measures

Depressive symptoms score measured by Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale, with scores ranging from 0 to 60.

Results

Level of positive and negative social support showed a negative and positive association with depressive symptom score with statistical significance at p<0.05, respectively. When the interaction terms among household income and social supports were examined, a negative association between level of positive social support and depressive symptom score was more pronounced as income was lower and level of negative social support was higher. Similarly, positive association between level of negative social support and depressive symptom score was more pronounced as income was lower and level of positive social support was lower.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that strategies for encouraging positive social support and discouraging negative social support for disadvantaged individuals might be effective in reducing depression in Korea.

Keywords: depressive symptom, multi-level regression, social capital, social support

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to explore the difference in the association between positive and negative social support and depressive symptom according to a different level of social support and economic status.

The article is based on a large study involving 21 208 Korean adults.

The study design is cross sectional and hence can only reveal associations between social support and depressive symptom.

We used health examination centres where respondents were recruited as a proxy for the community, which is not an accurate geographical classification.

Introduction

Depression has been proven to be associated with adverse health outcomes including increased susceptibility to disease through multiple mechanisms, such as disrupted immune functioning1–3 and altered health-related behavioural patterns (eg, excessive alcohol use, smoking, poor diet).4 5 In addition, depression is linked to suicide. Suicide ideation studies and psychological autopsy studies have proved the strong association between depression and suicide.6 7

Positive social support has been shown to be protective against risk of depression by buffering the effects of stress.4 8–11 Specifically, instrumental support, such as tangible assistance (labour, in kind) and financial support (eg, cash loans), has been demonstrated to lower the risk of depression by assisting individuals in coping with everyday hardships and facilitating their socioeconomic mobility.12 13 Emotional support such as companionship and intimacy can also buffer the individual from the harmful effects of stress.14 15 On the other hand, social support does not always give rise to positive experiences, however well meaning the intentions of the support giver may be. Social support can be negative when it is unwanted, at odds with the needs of the recipient, or when it makes the recipient uncomfortable, which could unintentionally serve as a potential source of stress.16–19 Thus, positive and negative supports represent two separate domains of social experience and may have independent effects on depression via different mechanisms.16 20 21

In addition, these two domains of social supports might interfere in the effect on psychological depression each other when they coexist. According to the ‘buffering effect model’, those with a high level of negative support may receive more benefit from the positive support in reducing depressive symptom. Conversely, high level of positive support may cushion the adverse effect of the stressor from negative supports on mental health.22 Only a handful of studies have explored on this and have not been updated for a long time.23–25

Socioeconomically disadvantaged people disproportionately experience conditions that elevate the risk of depression, such as precarious work, job loss, financial insecurity or disadvantaged living environment.26–29 In addition, urban dwellers, especially those in developed countries such as Canada and the UK, are usually more vulnerable to depression than those living in rural areas, owing to stresses from more frequent encounters with uneven distribution of socioeconomic status (SES), competitive work environment, higher rate of separated or divorced marital status, high rate of suffering from crime and poor social cohesion.30–33 These findings give rise to the question of whether positive or negative social support might benefit or harm more in financially distressed people living in an urban area. For example, better-off people may have the capacity to obtain information for coping with depressive moods from various sources other than their social networks. Similarly, they can afford to hire people or purchase things that can help them avoid depressive situations. However, to our knowledge, there was no study that has investigated on this to date. Most studies have focused only on the relationships between financial deprivation and depressive symptoms34–36 or on the protective influence of social support on depression.8–11

Korea is facing a continuous increase in depression. One-year prevalence of depression, the proportion of adults who had experienced depressive disorder more than once during the recent 12 months from the survey time, increased from 1.8% in 2001 to 3.1% in 2011.37

The current study sought to address the following research questions in Korean context while addressing the research gaps that exist in previous studies. The first, are positive and negative support independently associated with depressive symptoms? Second, do positive social support moderate the effect of negative social support on depressive symptom or vice versa? Finally, are the effects of positive and negative support more pronounced for less affluent individuals?

Methods

Data source

Our data came from a large-scale genomic cohort study called The Health Examinees-Gem (HEXA-G), which was established to investigate the epidemiological characteristics of major chronic diseases in Korean adults living in urban areas. Target participants, who are adult men and women aged 40–69, were recruited prospectively at 38 health examination centres or training hospitals located in eight regions in Korea (Seoul/Incheon/Gyeonggi-do, Gangwon-Do, Daejeon/Chungcheongnam-do, Chungcheongbuk-do, Daegu/Gyeongsangbuk do, Busan/Gyeongsangnam do, Jeollabuk-do, Gwangju/Jeollanam do) when they visited for their government-subsidised health examinations provided for free by the National Health Insurance Service biennially to all Korean adults aged over 40 for the purpose of effective health promotion and disease prevention. This way of recruiting can provide the advantages of longitudinal repeated measurements, and a pool of subjects that are representative of the majority of the Korean population.

The baseline survey was conducted by trained research staff using a standardised questionnaire, which included information on sociodemographic characteristics, medical history, medication usage, lifestyles, dietary habits and social capital. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Although the recruitment occurred in two phases (first-phase survey: 2004–2008, second-phase survey: 2009–2013), this study used data collected between March 2009 and March 2010, because of availability of information on depressive symptoms. More detailed information about the study design can be found elsewhere.38

Outcome variable

Depressive symptoms were measured using the 20-item version of the Centers for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D) which was developed for use in the epidemiological studies of depressive symptom in the general population.39 CES-D has been proved to be reliable in previous studies with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.84–0.90 depending on the ethnic groups.39 40 Respondents were asked to rate how often, over the preceding week, they experienced symptoms associated with depression, such as restless sleep, poor appetite and feelings of loneliness. Possible scores ranged between 0 and 3 for each item (0=less than 1 day per week, 1=1–2 days per week, 2=3–4 days per week and 3=more than 6 days per week). The overall score, obtained by summation of the individual items, has a possible range of 0–60, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms (online supplementary table 1).

bmjopen-2018-023036supp001.pdf (330.1KB, pdf)

Social support

Positive and negative social supports were measured by six items each. Whereas most previous studies have investigated the functional characteristics of social support based on the Social Experiences Checklist which measures positive and negative experiences of social supports (such as appreciation of relationships with others), the HEXA-G study investigated structural characteristics of social support, such as the presence of people around the respondent who provide certain kinds of positive or negative support in certain situations. Questions about positive social support in our study include both instrumental (eg, giving or lending it when I need something) and emotional dimensions (eg, caring or worrying about me). Questions about negative support also have two dimensions: aggressive type of negative support (eg, causing active harm to the respondent) and passive type of negative support (eg, indifference and neglect) (online supplementary table 2).

Respondents were asked to answer ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to each question. We referred to a previous study in operating social support variables where structural social support was coded into absolute levels of social capital (for example, number of individuals or groups respondents received support from) and then categorised into groups.41 We avoided using social support variable as continuous one because our interest is a relationship between the overall level of social support and depressive symptom rather than focusing on how much effect having one more people who can give social support would have on the depressive symptom.

To construct the variable reflecting level of positive and negative social support, the number of ‘yes’ responses to each of the six questions was summed first to create three ordinal groups. Since there is no objective or agreed-upon criteria used for determining level of social support, we chose the cut-off values considering frequency distribution: low positive/negative support (scores of 0–2 for positive support and 0–1 for negative support), medium positive/negative support (scores of 3–4 for positive support and 2–3 for negative support) and high positive/negative support (scores of 5–6 for positive support and 4–6 for negative support).

Other explanatory factors

Marital status was categorised into five categories: married or cohabiting, never married, divorced or separated, widowed and others. Age was divided into 10-year interval groups, starting at 40 years old. The SES factors included occupational status, education level and household income level. Specifically, respondents were asked to provide their occupational status by choosing among 14 kinds of job categorised by the Korean Standard Classification of Occupation. We grouped these into seven categories: non-manual (legislators, senior officials, managers, professionals, technicians and associate professionals, clerical support workers), service and sales workers, manual (skilled agricultural, forestry and fishery workers, craft and related trades workers, plant and machine operators and assemblers, elementary occupations), armed forces, housewives, unemployed and others. Educational attainment was grouped into four levels: primary school or below, high school graduate or below, college degree and graduate school or higher. Household monthly income was asked into four levels (unit: 10 000 Korean Won):<100 (≒ US$887), 100 to <300 (≒ US$2660), 300 to <600 (≒ US$5319) and ≥600.

We controlled for several community-level SES variables such as average income, average educational level and the employment rate in the community, which were created from the aggregation of their individual-level analogues. The purpose of this was to adjust for the SES-contextual effect of people living together in the community based on assumption that people may feel a different level of depressive symptom depending on the level of SES of their neighbourhood even if their individual SES is equal.

Patient and public involvement

This study did not involve patients. Participants were urban dwellers aged 40–69 who visited hospitals for their government-subsidised health examinations. The findings from this study will be disseminated to the wider public via local media and civil society organisations.

Statistical analyses

We constructed linear random intercept multilevel models to estimate the association between negative and positive social support and the risk of depressive symptoms while accounting for the clustering of observations at the community level. Because there is no residential address information in our dataset, we used the 38 health examination centres or training hospitals where survey population was recruited as a proxy for communities, assuming that people would visit the nearest centres to their residence for their medical check-ups.

We started by including positive and negative social supports alternately in the model with adjustment only for individual-level demographic variables: marital status, age and gender (models 1 and 2). From checking the correlation, we found a weak negative correlation between positive and negative social support (refer to the online supplementary table 3 for phi coefficients from χ2 analyses). Testing of variance inflation factor (VIF) revealed no multicollinearity between two (VIF=1.06 and 1.5 for the level of positive social support and negative social support, respectively). Therefore, we tried to run a model including both domains of social supports simultaneously with adjustment for only demographic characteristics first (model 3), and then additional adjustment for SES variables: occupational status, educational level and monthly income (model 4). This will enable us to test whether the association between one domain of social support and depressive symptom is not due to the confounding effect of the other domain of support. The reason for sequential entering of groups of demographic and SES variables was that we wanted to explore whether adjusting for SES would attenuate the association between positive or negative social supports and the outcome variable, assuming that SES might confound the association between social support and depressive symptoms. All potential two-way and three-way interaction terms between income and each domain of supports were explored (model 5). Finally, we tried to control for community-level SES variables (model 6). All statistical tests were two sided, and statistical significance was determined at p<0.05. Data were analysed using SAS V.9.3 software package.

Results

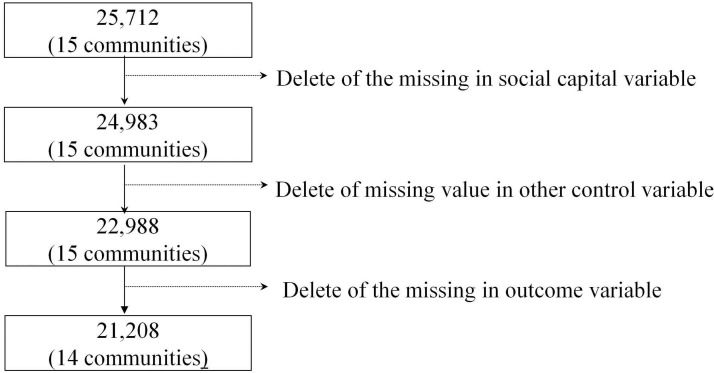

The total number of respondents who participated in the survey between March 2009 and March 2010 was 25 712 in 15 communities. After listwise deletion of participants with missing data in the independent and outcome variables, the final number of respondents for analysis was 21 208 in 14 communities (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Derivation process of the study sample.

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics of the sample. The married or cohabiting group, which accounted for almost 90% of the sample, showed the lowest level of depressive symptoms, whereas the separated or divorced category showed the highest level, ranging from 4.25 to 8.07. The difference in depressive symptom scores across age groups was less than 0.3. Men scored lower on depressive symptoms compared with women, on average. Depressive symptoms diminished as education level and monthly income level increased. Among occupations, the group working in the armed forces had the lowest average depressive symptoms score. There was a large difference in average depressive symptom scores across low, medium and high levels of positive and negative social support groups in the study sample.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics of a study sample of urban adults in Korea

| n | Proportion (%) | Mean depressive symptom score | |

| Marriage | |||

| Currently married/cohabiting | 19 037 | 89.76 | 4.25 |

| Never married | 514 | 2.42 | 5.11 |

| Separated/divorced | 671 | 3.16 | 8.07 |

| Widowed | 957 | 4.51 | 6.20 |

| Others | 29 | 0.14 | 5.59 |

| Age (yrs) | |||

| 40≤age<50 | 8387 | 39.55 | 4.44 |

| 50≤age<60 | 8098 | 38.18 | 4.61 |

| 60≤age<70 | 4723 | 22.27 | 4.34 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 7978 | 37.62 | 3.62 |

| Female | 13 230 | 62.38 | 5.01 |

| Education | |||

| Primary school or below | 3242 | 15.29 | 5.67 |

| High school graduate | 12 830 | 60.50 | 4.46 |

| College degree | 4277 | 20.17 | 3.90 |

| Graduate school or higher | 859 | 4.05 | 3.31 |

| Job | |||

| Non-manual | 3776 | 17.80 | 3.72 |

| Service and sales workers | 3983 | 18.78 | 4.22 |

| Manual | 4324 | 20.39 | 4.21 |

| Armed forces occupation | 24 | 0.11 | 2.21 |

| Housewives | 7106 | 33.51 | 5.33 |

| Unemployed | 1895 | 8.94 | 4.00 |

| Others | 100 | 0.47 | 5.37 |

| Income (Korean 10 000 Won)* | |||

| <100 | 2636 | 12.43 | 7.08 |

| 100≤income <300 | 9715 | 45.81 | 4.42 |

| 300≤income <600 | 7285 | 34.35 | 3.86 |

| 600<income | 1572 | 7.41 | 3.40 |

| Level of positive social support | |||

| Low | 833 | 3.93 | 11.51 |

| Medium | 1778 | 8.38 | 9.07 |

| High | 18 597 | 87.69 | 3.73 |

| Level of negative social support | |||

| Low | 18 856 | 88.91 | 3.66 |

| Medium | 1724 | 8.13 | 10.00 |

| High | 628 | 2.96 | 14.16 |

*US$1 ≒ 1128 Korea Won.

Models 1 and 2 in table 2 show the linear coefficients and 95% CIs for depressive symptoms according to the level of positive and negative social support, respectively, when only individual-level demographic variables were controlled. We found clear inverse gradient of positive social support and positive gradient of negative social support with depressive symptom (for positive social support, b=−2.73, p<0.001 in medium group; b=−6.69, p<0.001 in high group/for negative social supports, b=5.14, p<0.001 in medium group; b=9.29, p<0.001 in high group). When two domains of social support were run together in one model (model 3), negative support (or positive support) did not cancel out the benefits of positive support (or harm of negative support), indicating each domain of social support may operate independently (for positive social support, b=−2.38, p<0.001 in medium group; b=−5.54, p<0.001 in high group/for negative social supports, b=4.67, p<0.001 in medium group; b=8.18, p<0.001 in high group). Adjusting for SES variables did not attenuate the strength of association between social support and depressive symptom as shown in models 4 (for positive social support, b=−2.18, p<0.001 in medium group; b=−5.21, p<0.001 in high group/for negative social supports, b=4.63, p<0.001 in medium group; b=8.03, p<0.001 in high group).

Table 2.

Results from multilevel regression of positive and negative social supports and income on depressive symptom score in Korean urban adults

| Null | Model 1† | Model 2† | Model 3† | Model 4‡ | Model 5‡ | Model 6‡ | ||||||||

| Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | |

| Individual-level variables | ||||||||||||||

| <100 (Korean 10 000 Won)§ | ||||||||||||||

| 100≤income <300 | −1.46*** | 0.15 | −2.25*** | 0.35 | −2.26*** | 0.40 | ||||||||

| 300≤income <600 | −1.98*** | 0.17 | −3.69*** | 0.68 | −3.70*** | 0.78 | ||||||||

| 600<income | −2.40*** | 0.23 | −5.04*** | 1.02 | −5.05*** | 1.18 | ||||||||

| Positive social support (low level) | ||||||||||||||

| Medium | −2.73*** | 0.28 | −2.38*** | 0.27 | −2.18*** | 0.26 | −1.72*** | 0.35 | −1.72*** | 0.41 | ||||

| High | −6.69*** | 0.23 | −5.54*** | 0.23 | −5.21*** | 0.23 | −4.66*** | 0.54 | −4.66*** | 0.67 | ||||

| Negative social support (low level) | ||||||||||||||

| Medium | 5.14*** | 0.17 | 4.67*** | 0.16 | 4.63*** | 0.16 | 8.02*** | 0.16 | 8.02*** | 0.51 | ||||

| High | 9.29*** | 0.26 | 8.18*** | 0.26 | 8.04*** | 0.26 | 14.03*** | 0.26 | 14.03*** | 0.94 | ||||

| Positive social support × negative social support | −0.92*** | 0.15 | −0.92*** | 0.15 | ||||||||||

| Positive social support × income | 0.47*** | 0.12 | 0.47*** | 0.12 | ||||||||||

| Negative social support × income | −0.38** | 0.13 | −0.38** | 0.13 | ||||||||||

| Community-level variables | ||||||||||||||

| The share of the employed | 7.19 | 4.07 | ||||||||||||

| Mean income level | −4.73 | 4.61 | ||||||||||||

| Mean education level | 6.98 | 6.39 | ||||||||||||

| Community-level variance | 4.84*** | 3.48** | 1.33 | 3.00** | 1.15 | 2.45** | 0.93 | 2.61** | 0.10 | 2.59** | 1.03 | 1.90** | 0.73 | |

| Intraclass Correlation (ICC) | 0.09* | 0.08* | 0.07* | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.06* | 0.05* | |||||||

| R-squared¶ (level 1/level 2) | – | 0.09/0.23 | 0.13/0.33 | 0.17/0.46 | 0.18/0.42 | 0.18/0.40 | 0.19/0.58 | |||||||

Number of observations are 21 208 in all models.

*P<0.05.

**P<0.01.

***P<0.001.

†Adjusted for only demographic variables including marital status, age and gender.

‡Adjusted for both demographic and socioeconomic status variables including marital status, age, gender, job status and education level.

§US$1 ≒ 1128 Korea Won.

¶R-squared proposed by Snijders and Bosker.

Since the level of income, level of positive and negative social support were linearly related with depressive symptom in the main effect of model 4, interaction terms were constructed by multiplying each of these variables as a continuous one to simplify the model.

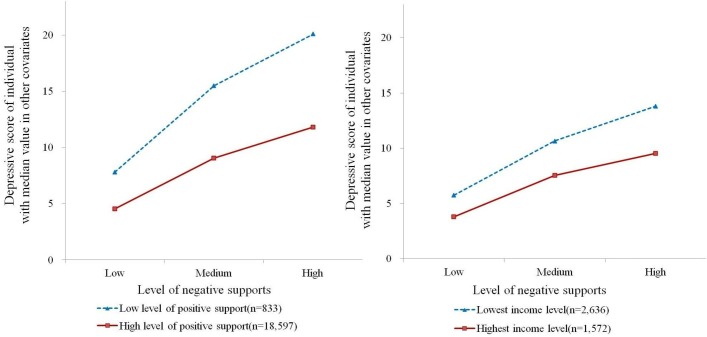

All the two-way interactions were found to be significant (model 5). Association between positive social support and the depressive symptom was different according to the level of negative social support as well as income level. Specifically, the negative association between the level of positive support and depressive symptoms score was stronger for individuals with a higher level of negative support and lower income level as shown in figure 2. Equivalently, the association between negative social support and depressive symptom depended on the level of positive social support and income. Negative social support had a stronger positive association with depressive symptom score in a group with a lower level of positive social support or lower income (figure 3). That is, high level of negative support had a similar effect as low income while a high level of positive support had a similar effect as high income in moderating associations with the depressive symptoms. In figures 2 and 3, we presented only the highest and lowest groups in the level of social support and in the level of income to show the differential effect in a maximised way. A three-way interaction term between positive, negative social support and income level was not significant (not presented). None of the community-level SES variable was significant (model 6).

Figure 2.

Differential effect of positive support according to the level of negative support and income level on depressive symptom.

Figure 3.

Differential effect of negative support according to the level of positive support and income level on depressive symptom.

Regarding the relevance of the other independent variables, marital status of being separated or divorced and being widowed, female gender and occupational status of housewife were associated with higher depressive symptom scores compared with their counterparts while older groups and people with higher education level were likely to have lower depressive symptom score (online supplemental table 4).

Discussion

This study, conducted among a sample of urban dwellers in South Korea, showed that low level of positive and high-level negative supports at the individual level were significantly associated with higher depressive symptom scores holding the effect of the negative and positive social support constant, respectively, meaning that positive and negative supports have their own independent effect. We also found that negative association of positive social support and positive association of negative social support with depressive symptom were magnified when the level of the other domain of social support was unfavourable or income level was low.

Our results on the association between positive social support and depressive symptoms are consistent with many previous findings, although there are slight differences in target groups and the definition of social support across studies.8–10 22 42 43 Generally, a low level of positive social support is associated with higher prevalence and incidence of the depressive symptom (or depressive disorder) in previous studies.

Although the exact pathways through which positive social support acts on mental health outcomes remain unclear, it has been posited generally to occur through two different processes that are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Stated briefly, positive social support may influence psychological well-being by buffering the adverse effects of emotional or financial stress (termed the ‘buffering effect model’); or it may have a ‘direct or main’ effect on mental health by fulfilling a person’s need for respect, social recognition, affection or nurturance, irrespective of stress status (termed the ‘main effect model’).44

The effect of negative social support on mental health in adults has been less explored in previous studies than that of positive social support. However, finding related to negative social support from the present study are also in line with finding in the previous study performed in Netherland that reported that negatively experienced supports are significantly associated with higher prevalence and incidence of poor mental health in men and women aged 26–65 years.45

Most previous articles focused on only positive or negative social support without considering the other and studies which have examined the simultaneous effect of two domains of social supports are rare and outdated. Among them, Ingersoll-Dayton (1997) has identified four models framing the effect of each domain of social exchange: ‘positivity effect model’ meaning that only positive exchange affects health outcome whether it is positive or negative outcomes; ‘negativity effect model’ arguing that only negative exchange affects outcome, again whether positive or not; ‘domain-specific effect model’ meaning that positive and negative exchange affects only positive and negative outcome, respectively; and lastly, ‘combined positivity and negativity effects model’ arguing that positive exchange and negative exchange affect both positive and negative outcome simultaneously.46 The result from our study supports the combined positivity and negativity effect model. A few other existing studies also support this model. For example, Golding and Burnam (1990) demonstrated that both social support and social conflict were significant predictors of depression among Mexican American adults when they were run together in a model.47 More recently, Croezen et al (2012) showed that low level of positive support and high level of negative support were associated with high odds of poor mental health at the same time in Dutch men and women.45

More notable findings from the present study are significant interactions among positive, negative social support and income on the depressive symptom. Those with a lower income and a higher level of negative support may receive greater benefits from positive social support and those with lower income and lower level of positive support may have greater damage from negative social supports compared with their counterparts. These findings may suggest that social supports play a similar role to income. Specifically, a high level of negative supports operated in the same way as low income in moderating the association between positive social support and depressive symptom as depicted in figure 2. Similarly, low level of positive supports operated in the same manner as low income in moderating the association between negative social support and depressive symptoms as shown in figure 3.

Low economic capacity can be linked to stress, low self-esteem, stigma, feelings of helplessness and hopelessness,43 and risk for marginalisation and social exclusion.22 However, these can be counterbalanced by positive social support. Negative social support serves as a type of stressor similar to low income, for which positive social support also can compensate for.48 Thus, the effect of positive support on reducing depressive symptom was stronger in a group with lower income and a higher level of negative social support. Emotional positive support, such as understanding, dialogue, appreciation or getting assistance with problem solving, can provide marginalised poor or people hurt by negative social support with the feeling that they are cared for, esteemed and valued. Tangible benefits bestowed by another aspect of positive support, named ‘instrumental supports’ such as help in housework or exchange of material resources, may also assist in coping with materially deprived circumstances or feeling of being unprotected or being isolated caused by negative social support.22 Conversely, negative supports such as perception of arguing, being criticised, feelings of undue demand or too much intervention may serve as an additional source of stress for poor people who are already psychologically vulnerable due to financial stress.40 While people with a high level of positive support have the capacity to buffer the harmful effect of negative support on the depressive symptoms, those without positive support may suffer from damage from negative support.

There are several studies which examined the interaction of positive and negative social support. While some have not found any evidence of interaction,25 36 others have observed a buffering effect of positive social support on the association between negative social support and mental health across different outcomes and population group.23 24 No previous studies have examined the interaction between social supports and income on mental health to our knowledge.

The result of the current study may provide important implications in the Korean context. Since the country’s economic crisis in late 1990, socioeconomic inequality has deepened, resulting in worsening social polarisation, which, in turn, caused a rising prevalence of depression.49 Suicide rate, for which depression has been blamed as a strong driver in Korea,50 51 also increased continuously from 8.4 in 1991 to 28.5 in 2013 (per 100 000 persons), ranking South Korea as the first in suicide rate among Organization for Economy Cooperation and Development countries since 2002.52 Despite these concerning trends, only a minority of people with depressive symptoms seek professional consultation, for fear of the cultural stigma attached to mental illness.53 Because economic disadvantage has been well recognised as a determinant of depression in Korea,54 the results of our study provide supporting evidence for interventions encouraging positive social support or discouraging negative social support in underprivileged populations.

Although the poor are more affected by social support than the better off, they also tend to have more limited capacity to control social support on their own by generating positive support or avoiding negative support. For example, people with economic capacity have more access to receive positive emotional support because they can afford private psychologists or clinical counsellors. Similarly, they have more access to instrumental positive support by hiring private caregivers or housekeepers when they cannot find those supports among close people around them. Therefore, interventions to mobilise positive social support or prevent negative support for those with limited economic means might be effective for lowering depressive symptoms in society.

Strength and limitations

Although this study is unique in separately analysing the effects of positive and negative social support on depressive symptoms according to income level in a large sample, it also has a few limitations to be noted when interpreting the results. First, there is a possibility of reverse causation, given the cross-sectional nature of the study. For example, people with depressive symptoms may become less sociable and less engaged in social networks, thereby eventually reducing social support.55 Second, we used the 38 health examination centres or training hospitals where target populations were recruited as a proxy for communities. Although this is not a geographical classification based on respondents’ residential address, equating it with a community is assumed to be reasonable; most people are likely to go to the hospitals nearest to their residence for their government-subsidised medical check-ups because there is no much difference in quality between hospitals designated for government-subsidised health examination. Third, because no agreed-upon cut-off points for high or low levels of social support were available, we classified sum scores into three ordinal groups considering the number of people belonging to each group. To test the sensitivity of the result to the categorisation of social support level, we reran the analyses using the score as a continuous variable. These different ways of categorisation produced the almost same results.

Conclusion

The present study showed that, at the individual level, both positive and negative social supports were associated with depressive symptoms, and these associations were found to be stronger in economically disadvantaged people when adjusting for various control variables at multiple levels. In addition, positive and negative social support moderated the association of negative and positive social support with depressive symptoms, respectively. Reducing inequality is always challenging, although most pursue social equality as an ideal. The results of this study suggest that strategies for adjusting positive and negative support among low-income populations might be effective in reducing depressive symptoms in those populations.

Further study is required to reveal the mechanisms by which different types of individual social support operate on depressive symptoms in each economic group in the context of South Korea.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ellen Daldoss from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: HYL and JO conceived the study. HYL led the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. JO provided supervision throughout the data analysis and interpretation. IK provided overall guidance and helped to edit language. JH, SK, J-KL and DK helped to interpret the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a Research Program funded by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2004-E71004-00, 2005-E71011-00, 2005-E71009-00, 2006-E71001-00, 2006-E71004-00, 2006-E71010-00, 2006-E71003-00, 2007-E71004-00, 2007-E71006-00, 2008-E71006-00, 2008-E71008-00, 2009-E71009-00, 2010-E71006-00, 2011-E71006-00, 2012-E71001-00 and 2013-E71009-00).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The HEXA-G study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Korean Health and Genomic Study of the Korean National Institute of Health as well as by the institutional review boards of all participating hospitals.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Data are available from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for researchers who meet the criteria for access to the data. Researchers may contact Yeonjung Kim, Division of Epidemiology and Health Index, Center for Genome Science, Korea.

Patient and public involvement: Not required.

References

- 1. Irwin M, Daniels M, Bloom ET, et al. . Life events, depressive symptoms, and immune function. Am J Psychiatry 1987;144:437–41. 10.1176/ajp.144.4.437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Schleifer SJ, Keller SE, Siris SG, et al. . Depression and immunity. Lymphocyte function in ambulatory depressed patients, hospitalized schizophrenic patients, and patients hospitalized for herniorrhaphy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1985;42:129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schleifer SJ, Keller SE, Bartlett JA. Depression and immunity: clinical factors and therapeutic course. Psychiatry Res 1999;85:63–9. 10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00133-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cohen S, Wills TA. Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychol Bull 1985;98:310–57. 10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Morris PL, Raphael B, Robinson RG. Clinical depression is associated with impaired recovery from stroke. Med J Aust 1992;157:239–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. De Leo D, San Too L. Suicide and depression. Essentials of Global Mental Health 2014:367. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yoshimasu K, Kiyohara C, Miyashita K. Stress Research Group of the Japanese Society for Hygiene. Suicidal risk factors and completed suicide: meta-analyses based on psychological autopsy studies. Environ Health Prev Med 2008;13:243–56. 10.1007/s12199-008-0037-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wade TD, Kendler KS. The relationship between social support and major depression: cross-sectional, longitudinal, and genetic perspectives. J Nerv Ment Dis 2000;188:251–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Stice E, Ragan J, Randall P. Prospective relations between social support and depression: differential direction of effects for parent and peer support? J Abnorm Psychol 2004;113:155–9. 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moak ZB, Agrawal A. The association between perceived interpersonal social support and physical and mental health: results from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Public Health 2010;32:fdp093 10.1093/pubmed/fdp093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Israel BA, Farquhar SA, Schulz AJ, et al. . The relationship between social support, stress, and health among women on Detroit’s East Side. Health Educ Behav 2002;29:342–60. 10.1177/109019810202900306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Henly JR, Danziger SK, Offer S. The contribution of social support to the material well-being of low-income families. J Marriage Fam 2005;67:122–40. 10.1111/j.0022-2445.2005.00010.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13. de Souza Briggs X, Briggs deS X. Brown kids in white suburbs: Housing mobility and the many faces of social capital. Hous Policy Debate 1998;9:177–221. 10.1080/10511482.1998.9521290 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cooper PJ, Tomlinson M, Swartz L, et al. . Improving quality of mother-infant relationship and infant attachment in socioeconomically deprived community in South Africa: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2009;338:b974 10.1136/bmj.b974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Campbell SB, Morgan-Lopez AA, Cox MJ, et al. . A latent class analysis of maternal depressive symptoms over 12 years and offspring adjustment in adolescence. J Abnorm Psychol 2009;118:479–93. 10.1037/a0015923 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Croezen S, Haveman-Nies A, Picavet HS, et al. . Positive and negative experiences of social support and long-term mortality among middle-aged Dutch people. Am J Epidemiol 2010;172:173–9. 10.1093/aje/kwq095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Oxman TE, Hull JG. Social support, depression, and activities of daily living in older heart surgery patients. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997;52B:P1–P14. 10.1093/geronb/52B.1.P1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Oxman TE, Berkman LF, Kasl S, et al. . Social support and depressive symptoms in the elderly. Am J Epidemiol 1992;135:356–68. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hays JC, Krishnan KR, George LK, et al. . Psychosocial and physical correlates of chronic depression. Psychiatry Res 1997;72:149–59. 10.1016/S0165-1781(97)00105-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Newsom JT, Rook KS, Nishishiba M, et al. . Understanding the relative importance of positive and negative social exchanges: examining specific domains and appraisals. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2005;60:P304–12. 10.1093/geronb/60.6.P304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pagel MD, Erdly WW, Becker J. Social networks: we get by with (and in spite of) a little help from our friends. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987;53:793–804. 10.1037/0022-3514.53.4.793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aneshensel CS, Frerichs RR. Stress, support, and depression: a longitudinal causal model. J Community Psychol 1982;10:363–76. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Revenson TA, Schiaffino KM, Majerovitz SD, et al. . Social support as a double-edged sword: the relation of positive and problematic support to depression among rheumatoid arthritis patients. Soc Sci Med 1991;33:807–13. 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90385-P [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rhodes JE, Woods M. Comfort and conflict in the relationships of pregnant, minority adolescents: Social support as a moderator of social strain. Journal of Conununuy Psychology 1995:23. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Okun MA, Keith VM. Effects of positive and negative social exchanges with various sources on depressive symptoms in younger and older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1998;53:P4–P20. 10.1093/geronb/53B.1.P4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Takeuchi DT, Williams DR. Race, ethnicity and mental health: introduction to the special issue. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 2003;44:233–6. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Smedley BD, Syme SL. Committee on Capitalizing on Social Science and Behavioral Research to Improve the Public’s Health. Promoting health: intervention strategies from social and behavioral research. Am J Health Promot 2001;15:149–66. 10.4278/0890-1171-15.3.149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pickett KE, Pearl M. Multilevel analyses of neighbourhood socioeconomic context and health outcomes: a critical review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2001;55:111–22. 10.1136/jech.55.2.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Silver E, Mulvey EP, Swanson JW. Neighborhood structural characteristics and mental disorder: Faris and Dunham revisited. Soc Sci Med 2002;55:1457–70. 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00266-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wang JL. Rural-urban differences in the prevalence of major depression and associated impairment. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2004;39:19–25. 10.1007/s00127-004-0698-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Paykel ES, Abbott R, Jenkins R, et al. . Urban-rural mental health differences in great Britain: findings from the national morbidity survey. Psychol Med 2000;30:269–80. 10.1017/S003329179900183X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Andrade L, Caraveo-Anduaga JJ, Berglund P, et al. . The epidemiology of major depressive episodes: results from the International Consortium of Psychiatric Epidemiology (ICPE) Surveys. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 2003;12:3–21. 10.1002/mpr.138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Weich S, Twigg L, Lewis G. Rural/non-rural differences in rates of common mental disorders in Britain. British Journal of Psychiatry 2006;188:51–7. 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.008714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lorant V, Croux C, Weich S, et al. . Depression and socio-economic risk factors: 7-year longitudinal population study. Br J Psychiatry 2007;190:293–8. 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Belle D, Doucet J. Poverty, inequality, and discrimination as sources of depression among U.S. Women. Psychol Women Q 2003;27:101–13. 10.1111/1471-6402.00090 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rhodes JE, Ebert L, Fischer K. Natural mentors: an overlooked resource in the social networks of young, African American mothers. Am J Community Psychol 1992;20:445–61. 10.1007/BF00937754 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hong DL JP, Ham BJ, Lee SH, et al. . The survye of mental disorders in Korea. Seoul, Korea: Samsung Medical Center, 2017:1–502. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Group HES. The Health Examinees (HEXA) study: rationale, study design and baseline characteristics. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2015;16:1591–7. 10.7314/APJCP.2015.16.4.1591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied psychological measurement 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Roberts RE. Reliability of the CES-D Scale in different ethnic contexts. Psychiatry Res 1980;2:125–34. 10.1016/0165-1781(80)90069-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. De Silva MJ, Harpham T. Maternal social capital and child nutritional status in four developing countries. Health Place 2007;13:341–55. 10.1016/j.healthplace.2006.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Manuel JI, Martinson ML, Bledsoe-Mansori SE, et al. . The influence of stress and social support on depressive symptoms in mothers with young children. Soc Sci Med 2012;75:2013–20. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Neugebauer A, Katz PP. Impact of social support on valued activity disability and depressive symptoms in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004;51:586–92. 10.1002/art.20532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Aneshensel CS, Stone JD. Stress and depression: a test of the buffering model of social support. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1982;39:1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Croezen S, Picavet HS, Haveman-Nies A, et al. . Do positive or negative experiences of social support relate to current and future health? Results from the Doetinchem Cohort Study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:65 10.1186/1471-2458-12-65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ingersoll-Dayton B, Morgan D, Antonucci T. The effects of positive and negative social exchanges on aging adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1997;52:S190–9. 10.1093/geronb/52B.4.S190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Golding JM, Burnam MA. Immigration, stress, and depressive symptoms in a Mexican-American community. J Nerv Ment Dis 1990;178:161–71. 10.1097/00005053-199003000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lepore SJ. Social conflict, social support, and psychological distress: evidence of cross-domain buffering effects. J Pers Soc Psychol 1992;63:857–67. 10.1037/0022-3514.63.5.857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Cho MJ, Kim JK, Jeon HJ, et al. . Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-IV psychiatric disorders among Korean adults. J Nerv Ment Dis 2007;195:203–10. 10.1097/01.nmd.0000243826.40732.45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kim SW, Kim SJ, Mun JW, et al. . Psychosocial factors contributing to suicidal ideation in hospitalized schizophrenia patients in Korea. Psychiatry Investig 2010;7:79–85. 10.4306/pi.2010.7.2.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kim SW, Yoon JS. Suicide, an urgent health issue in Korea. J Korean Med Sci 2013;28:345–7. 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.3.345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Economic O. Environmental and Social Statistics. France: OECD Publication Service, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cho SJ, Lee JY, Hong JP, et al. . Mental health service use in a nationwide sample of Korean adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2009;44:943–51. 10.1007/s00127-009-0015-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Park JH, Kim KW, Kim MH, et al. . A nationwide survey on the prevalence and risk factors of late life depression in South Korea. J Affect Disord 2012;138:34–40. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.12.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Monroe SM, Steiner SC. Social support and psychopathology: interrelations with preexisting disorder, stress, and personality. J Abnorm Psychol 1986;95:29–39. 10.1037/0021-843X.95.1.29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023036supp001.pdf (330.1KB, pdf)