Abstract

Objectives

To determine the short-term impact of a soft opt-out organ donation system on consent rates and donor numbers.

Design

Before and after observational study using bespoke routinely collected data.

Setting

National Health Service Blood and Transplant.

Participants

205 potential organ donor cases in Wales.

Interventions

The Act and implementation strategy.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Consent rates at 18 months post implementation compared with 3 previous years, and organ donor numbers 21 months before and after implementation. Changes in organ donor register activity post implementation for 18 months.

Results

The consent rate for all modes of consent was 61.0% (125/205), showing a recovery from the dip to 45.8% in 2014/2015. 22.4% (46/205) were deemed consented donors: consent rate 60.8% (28/46). Compared with the 3 years before the switch there was a significant difference in Welsh consent rates (χ2 p value=0.009). Over the same time period, rest of the UK consent rates also significantly increased from 58.6% (5256/8969) to 63.1% (2913/4614) (χ2 p value<0.0001), therefore the Wales increase cannot be attributed to the Welsh legislation change. Deceased donors did not increase: 101 compared with 104. Organ donation registration increased from 34% to 38% with 6% registering to opt-out.

Conclusion

This is the first rigorous initial evaluation with bespoke data collected on all cases. The longer-term impact on consent rates and donor numbers is unclear. Concerns about a potential backlash and mass opting out were not realised. The move to a soft opt-out system has not resulted in a step change in organ donation behaviour, but can be seen as the first step of a longer journey. Policymakers should not assume that soft opt-out systems by themselves simply need more time to have a meaningful effect. Ongoing interventions to further enhance implementation and the public’s understanding of organ donation are needed to reach the 2020 target of 80% consent rates. Further longitudinal monitoring is required.

Keywords: health policy, organisation of health services

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Bespoke routinely collected data were analysed for all potential organ donor cases.

A large group of patient and public representatives worked with researchers to co-produce the study.

The study is limited to establishing short-term impacts and a longitudinal study with larger numbers is required to determine changes over time.

Introduction

Around 6500 people are waiting for organ transplants in the UK.1 Organ transplantation is cost-effective and improves quality of life for recipients.2 Organ donation consent rates in the UK need to improve to keep up with demand for transplants.3

Under the opt-in system in Wales, consent rates for deceased organ donation ranged between a high of 53.6% to a low of 48.5% between 2013 and 2015.4 In contrast consent rates in some other European countries are much higher. For example, in Spain consent ranges from 80% to 85% in an opt-out system in which all citizens are automatically assumed to consent to organ donation unless they choose to state otherwise.5

The British Medical Association, patient groups and newspapers6 7 have lobbied for the introduction of an opt-out system to replace the current opt-in system in the respective UK nations (England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland). The UK nations have separate, and in the case of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland devolved, responsibilities for health. There are two types of ‘opt-out’ system: a ‘hard’ opt-out where the family are not consulted or a ‘soft’ opt-out where the family are consulted. Opinion is starkly divided as to the benefits of introducing either form of opt-out system of organ donation compared with reorganisation of the current opt-in system to increase consent rates.8 9 A comparison of the opt-in and soft opt-out default systems can be found in table 1. Table 2 contains key operational definitions.

Table 1.

Comparison of the previous opt-in and new soft out-opt system in Wales

| Decision type | ||||

| Active | Passive | Geographical reach | Role of family | |

| Former opt-in system | Expressed decision Register to opt-in on the organ donor register Verbally tell a relative or friend you want or do not want to be a donor Write telling a relative or friend you want or do not want to be a donor Nominate a representative to make the decision for you (nowhere to record this decision) |

Do nothing and remain a non-donor | UK wide | To give consent for organ donation |

| New opt-out system in Wales | Expressed decision Register to opt-in on the organ donor register Verbally tell a relative or friend you want to be a donor Write telling a relative or friend you want or do not want to be a donor Register to opt-out on the organ donor register Appoint a patient representative on the organ donor register to make the decision for you |

Do nothing and remain as a donor (deemed consent) |

Wales only Welsh citizens have to die in Wales for the soft opt-out to apply. If they die in England the opt-in system applies |

To support the donation decision of their relative made in life, but family members can still not support the donation decision if specific evidence requirements are met. |

Table 2.

Additional key terms and operational definitions

| Key term | Definition |

| Opt-in organ donation system | The default is to be a non-donor unless an individual actively registers or expresses to be an organ donor |

| Opt-out organ donation system | The default is presumed consent (called deemed consent in Wales) to organ donation, unless an individual actively opts-out |

| Hard opt-out organ donation system | The family are not consulted |

| Soft opt-out organ donation system | The family are consulted |

| Soft opt-out eligibility criteria Wales | Over 18 years, voluntarily resident in Wales, mental capacity, die in Wales |

| Expressed decision | A person may register their decision on the organ donor register or convey it verbally or in writing to family members (see table 1 for options available under the different systems) |

| Organ donor register | Under the former opt-in system individuals could only opt-in to be a donor on the register. With the introduction of the soft opt-out system in Wales the register was amended so that individuals can opt-in or opt-out of organ donation on the register, and appoint a representative to convey the decision for them |

| Presumed/deemed consent | The terms are interchangeable, but in Wales the term used is deemed consent. A person* who has not actively expressed their organ donation decision during life is considered to have no objection to organ donation and their consent can be deemed |

| Known donation decision | The potential organ donor has made their decision known during their life-time by either registering it on the organ donation register or conveying it verbally or in writing to family members/close friends |

| Family consent in the soft opt-out system | Family consent is for children under 18 years, and for potential organ donors who do not meet residency criteria or lack mental capacity |

| Organ donation decision overrides | Under the new soft opt-out system, family members are expected to support the organ donation decision of their relative made in life. To override their relative’s decision family members should provide witnessed written evidence or a witnessed conversation that the potential organ donor had changed their mind and opted for a different donation decision (the last known decision) |

*Eligibility criteria apply.

Following an extensive public consultation, the Human Transplantation (Wales) Act 2013 introduced a soft opt-out system of organ donation, which was fully enacted on 1 December 2015.10 The purpose of the Act is to make it easier for people to donate their organs to benefit patients. The primary aim is to increase consent rates. In the Welsh soft opt-out system unless the deceased person has expressed a decision in life (either for or against being be an organ donor) it will be assumed that they have no objection to organ donation and their consent can be deemed. Family members are expected to support the donation decision made by their relative in life.

How the intervention is intended to work

A detailed description of the components and how the intervention is intended to work can be found in the study protocol.4 In summary, the Act, media campaign and implementation strategy were conceptualised as a complex behaviour change intervention. The Act changed the principles of consent to deceased organ donation from an opt-in to a soft opt-out system for adults 18 years or over; voluntarily resident for 12 months or more in Wales; who have not made an expressed decision regarding organ donation; and is competent to understand the notion of deemed consent. The individual must also die in Wales for the Act to apply. In addition to the public media campaign, there was an accompanying implementation strategy for National Health Service (NHS) and NHS Blood and Transplant (NHSBT) staff, which required amending clinical protocols and procedures and retraining large numbers of staff and all Specialist Nurses in Organ Donation (SNODs) covering Wales. The success of the Act depended on behaviour change of the public and professionals. The theory is that the neutral media campaigns supporting implementation will facilitate the behaviours in Welsh citizens outlined in box 1.

Box 1. Intended behaviours of the citizens of Wales under the soft opt-out system.4 .

Opt-in or opt-out on the organ donor register (registered decision), with the option of appointing a patient representative.

Discuss opt-in or opt-out donation decision with families and friends (express decision).

Do nothing and it will be assumed that the person does not object to organ donation (deemed consent).

Families will put aside their own views on donation and respect the decision of the deceased person made in life.

There are few examples where soft opt-out systems have been implemented in the context of rigorous research and no examples of process evaluations with family members who were approached about organ donation when a change to a soft opt-out system has been implemented. The aim of this study was to determine the short-term impact of the introduction of a soft opt-out system of organ donation on consent rates and organ donor numbers. Elsewhere we report the process evaluation findings of the nurse-led implementation of the soft opt-out system that help contextualise and explain the initial impacts.

Methods

We worked with NHSBT to analyse a bespoke dataset of routinely collected data (including the Potential Donor Audit) on all potential organ donor cases, and organ donor registration activity for 18 months after the 1 December 2015 when the soft opt-out was implemented in Wales, compared with up to 3 years pre implementation.4 Welsh Government shared comparative figures on numbers of deceased donors for 21 months before and after implementation.11 For the purposes of his study a potential organ donor was defined as a patient who is eligible for organ donation and whose family is approached for a formal organ donation discussion.

Primary and secondary outcomes

Consent rates and numbers of organ donors compared with previous years. Changes in organ donor register activity post implementation for 18 months.

Participants

All 205 potential organ donor cases in Wales were included.

Data collection and analysis

NHSBT bespoke routinely collected data on each case

Retrospective data on consent rates, donor numbers and transplant numbers are routinely collected for each financial year (12 months). We worked with NHSBT to analyse bespoke prospective data for 18 months post implementation on 1 December 2018. These data covered one full financial year and a period of months from two further financial years. NHSBT statisticians compiled summary reports of descriptive statistics for the 18-month post implementation period and provided reports of comparative retrospective data, and statistical significance. A χ2 test was used to determine whether there was a statistical difference in overall consent rates between the 3 years prior to the introduction of the soft opt-out and deemed consent compared with the 18 months following the introduction of the soft opt-out and deemed consent (table 3).12 Rest of the UK national trends in consent rates were also used as a comparative context. Data were grouped by mode of consent (expressed and registered opt-in and opt-out; deemed, and family consent), and total numbers of families approached. Data on proceeding donors and transplants were also compared. In addition, Welsh Government shared their analysis of numbers of organ donors for 21 months pre implementation and post implementation.

Table 3.

Before and after results

| Families approached by subsequent mode of consent: deceased organ donation Wales | Retrospective before | Prospective after implementation of the soft opt-out on 1 December 2015 | |||||

| April 2012–March 2013 12 months |

April 2013–March 2014 12 months |

April 2014–March 2015 12 months |

December 2015–March 2015 4 months |

April 2016–March 2017 12 months |

April 2017–May 2017 2 months |

Total December 2015–May 2017 18 months |

|

| Total families approached: number of cases | 161 | 169 | 153 | 54 | 141 | 10 | 205 |

|

Total cases that met the criteria for a known decision or having their consent deemed.

Excludes family consent (child, not Welsh resident, lacks mental capacity) |

N/A | N/A | N/A | 51/54 (94.4%) | 124/141 (87.9%) | 7/10 (70.0%) | 182/205 (88.8%) |

| Expressed consent | 56/161 (34.8%) Registered opt-in on ODR 48/56 (85.7%) Verbally expressed opt-in 7/56 (12.5%) Other 1/56 (1.8%) |

62/169 (36.7%) Registered opt-in on ODR 52/62 (83.9%) Verbally expressed opt-in 10/56 (17.8%) |

48/153 (31.4%) Registered opt-in on ODR 43/48 (89.6%) Verbally expressed opt-in 5/48 (10.4%) |

21/51 (41.2%) | 76/124 (61.3%) | 5/7 (71.4%) | 102/205 (49.7%) Registered opt-in on ODR 73/102 (71.6%) Verbally expressed opt-in 29/102 (28.4%) |

| Deemed consent | N/A | N/A | N/A | 13/51 (25.5%) | 31/124 (25.0%) | 2/7 (28.6%) | 46/205 (22.4%) |

| Family consent | 105/161 (65.2%) | 107/169 (63.3%) | 105/153 (68.6%) | 3/51 (5.9%) | 17/124 (13.7%) | 3/10 (30.0%) | 23/205 (11.2%) |

| Total patient opt-outs | N/A | N/A | N/A | 17/51 (33.3%) | 17/124 (13.7%) | 0 | 34/205 (16.5%) |

| Registered opt-out on ODR | N/A | N/A | N/A | 3/17 (17.6%) | 5/124 (4.03%) | 0 | 8/34 (23.5%) |

| Verbally expressed opt-out | N/A | N/A | N/A | 14/17 (82.3%) | 12/124 (9.7%) | 0 | 26/34 (76.5%) |

| Mode of consent ascertained (consent rate) | |||||||

| Total consent ascertained* | 81/161 (50.3%) | 91/169 (53.8%) | 70/153 (45.8%) | 29/54 (53.7%) | 90/141 (63.8%) | 6/10 (60.0%) | 125/205 (61.0%) |

| Total consent for cases that met the criteria for a known decision or having their consent deemed | N/A | N/A | N/A | 27/51 (52.9%) | 85/124 (68.5%) | 5/7 (71.4%) | 117/182 (64.2%) |

| Expressed consent | 48/56 (85.7%) | 53/62 (85.5%) | 37/48 (77.1%) | 18/21 (85.7%) | 66/76 (86.8%) | 5/5 (100%) | 89/102 (87.2%) |

| Deemed consent | N/A | N/A | N/A | 9/13 (69.2%) | 19/31 (61.2%)) | 0 | 28/46 (60.8%) |

| Family consent | 33/105 (31.4%) | 38/107 (35.5%) | 33/105 (31.4%) | 2/3 (66.6%) | 5/17 (29.4%) | 1/3 (33.3%) | 8/23 (34.7%) |

| Overrides by family members | |||||||

| Total overrides by family members | 8/161 (5%) | 9/169 (5.3%) | 11/153 (7.2%) | 7/54 (12.9%) | 22/141 (29.1%) | 2/10 (20%) | 31/205 (15.1%) |

| ODR overrides | 8/48 (16.7%) | 7/52 (13.5%) | 10/43 (23.3%) | 12/73 (16.4%) | |||

| Other expressed overrides | 0 | 2/10 (20%) | 1/5 (20%) | 1/29 (3.4%) | |||

| Deemed consent | N/A | N/A | N/A | 18/46 (39.1%) | |||

| Proceeding donors by mode of consent | |||||||

| Expressed consent: verbal or ODR registration | 26/48 (51.4%) | 33/53 (62.2%) | 28/37 (75.7%) | 13/18 (72.2%) | 43/66 (65.1%) | 4/5 (80.0%) | 60/89 (67.4%) |

| Deemed consent | N/A | N/A | N/A | 9/9 (100%) | 11/19 (57.9%) | 0 | 20/28 (71.4%) |

| Family consent | 24/33 (72.3%) | 21/38 (55.3%) | 26/33 (78.8%) | 2/2 (100%) | 4/5 (80.0%) | 1/1 (100%) | 7/8 (87.5%) |

| Total | 52/81 (64.2%) | 54/91 (59.3%) | 60/70 (85.7%) | 24/29 (82.7%) | 58/90 (64.4%) | 5/6 (83.3%) | 87/125 (69.6%) |

| Organs donated by mode of consent | |||||||

| Expressed consent: verbal or ODR registration | 89 | 108 | 100 | 44 | 136 | 17 | 197 |

| Deemed consent | N/A | N/A | N/A | 31 | 39 | 0 | 70 |

| Family consent | 88 | 69 | 78 | 12 | 10 | 4 | 26 |

| Total | 177 | 177 | 178 | 87 | 185 | 21 | 293 |

| Organs transplanted by mode of consent | |||||||

| Expressed consent: verbal or ODR registration | 83 | 97 | 87 | 36 | 116 | 15 | 167 |

| Deemed consent | N/A | N/A | N/A | 26 | 33 | 0 | 59 |

| Family consent | 82 | 63 | 62 | 12 | 9 | 2 | 23 |

| Total | 165 | 160 | 149 | 74 | 158 | 17 | 249 |

| Comparative total consent ascertained rate for England | 57.9% | 59.6% | 58.5% | 62.5% | |||

| Comparative donor numbers Figures shared by Welsh Government for 21 months pre and post8 | 21 months pre—101 | 21 months post—104 | |||||

*Before and after change in consent rates was statistically sifnificant but could not be attributed to the new Welsh soft opt-out system when rest of the UK increases in organ donation consent rates over the same time period are factored in.

Patient and public involvement

This was a co-productive study with extensive patient and public involvement of over 50 people and organisations in the design, analysis and interpretation of data. A 2-day residential meeting and an end of study event were convened to discuss and interpret findings. Patient and public involvement was most evident in the design and conduct of the associated process evaluation. A detailed report evaluating the impact of the co-productive approach and the contribution of patient and public representatives is published elsewhere.

Results

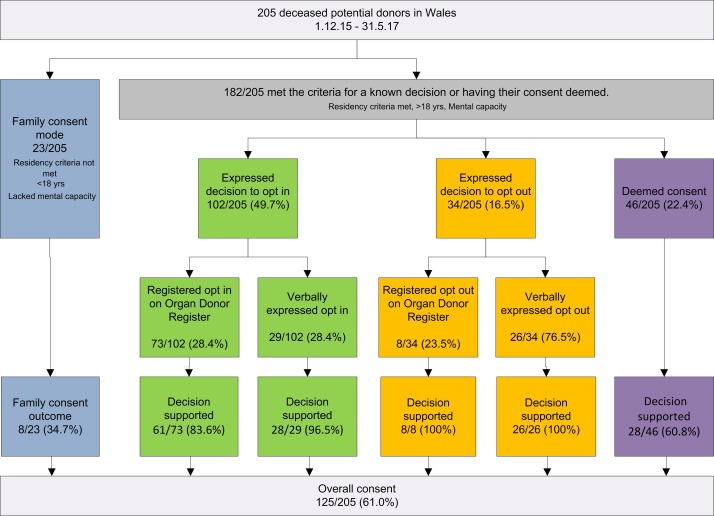

There were 205 deceased donors in Wales of which 88.7% (182/205) met the criteria for a known decision [ie, they expressed a decision in life (either for or against being be an organ donor) or having their consent deemed (figure 1 and table 3)]. The remaining 11.2% (23/205) cases met the criteria for the ‘family’ mode of consent as the deceased person was a child, lacked mental capacity or did not meet residency criteria. The consent rate for all modes of consent was 61.0% (125/205), showing a recovery from the dip to 45.8% in 2014/2015. Compared with the consent rates in the 3 full financial years prior to the introduction of deemed consent in Wales there was a significant difference in the consent rates (χ2 p value=0.009). Over the same time period consent rates in the rest of the UK nations also significantly increased from 58.6% (5256/8969) to 63.1% (2913/4614) (χ2 p value<0.0001), therefore while the observed increase in consent in Wales is positive, the increase cannot be attributed to the change in legislation in Wales.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of post implementation consent decisions.

When family consent was excluded, the consent rate for 182/205 cases that met the criteria for a known decision or deemed consent was 64.2%. Just over 22% (46/182) of cases were deemed consented donors with a consent rate 60.8% (28/46).

Seventy-nine per cent (162/205) had registered or expressed a decision, of which 62.4% (128/205) of cases had registered or expressed their decision to opt-in. Fifty-seven per cent (73/128) registered to opt-in on the organ donor register, and 22.6% (29/128) verbally expressed to opt-in with their families during their lifetime. Just over 16.5% (34/205) opted-out: 8/34 opted-out on the organ donor register and 26/34 expressed to their families that they wanted to opt-out.

Family members still overrode 15.1% (31/205) opt-in decisions to donate, including 16.4% (12/73) organ donor registered opt-in decisions; 3.4% (1/29) verbally expressed opt-in decisions, and 39.1% (18/46) deemed consents.

Of the 125/205 cases where consent to deceased donation was supported by family members, 69.6% (87/125) proceeded to donation. The number of deceased donors remained relatively static (101 compared with 104 21 months pre implementation and post implementation).11 The number of potential donors however fell over this period, so although the overall donor numbers stayed roughly the same, this was in the context of fewer potential donors. Finally, organ donation registration increased from 34% to 38%. As of June 2017, 1 181 709 people in Wales had opted-in and 176 011 opted-out, which is 6% of the population and less than the Government anticipated would opt-out.

Discussion

While the observed increase in consent rates in Wales is positive, it is too early to tell if the soft opt-out system will be successful in further increasing consent rates compared with the rest of the UK nations. It is clear from the analysis that the move to a soft opt-out system has not resulted in a step change in organ donation behaviour, but is the first step of a longer journey.

Although there was general support for the soft opt-out system, decisions made by the citizens of Wales during life were not consistently supported as intended by family members in death. The success of the soft opt-out system is dependent on family members supporting their relative’s donation decision made in life. Consent rates would have been higher if family members had consistently supported their relative’s opt-in decision, although this would apply to both opt-in and opt-out systems. While acknowledging that numbers are too small at this stage to undertake a more sophisticated statistical analysis, and the introduction of new modes of consent (with new potential opportunity to override) make direct comparisons difficult to interpret, there was an observed upward trend in family overrides following introduction of the soft opt-out system (table 3). For the 3 years prior to implementation family overrides ranged from 5% to 7.2%. Post implementation it was 15.1% over 18 months, and 29.1% in 2016/2017. Some of the increase can be explained by the introduction of deemed consent, which provided a new opportunity to override that did not exist before. The reasons why family members still override their relative’s opt-in decision are numerous and complex and our process evaluation published elsewhere provides a detailed explanation to contextualise the findings reported here. Importantly, process evaluation findings show that SNODs were not able to establish the required standard of evidence to override an opt-in donation decision made in life. They accepted a lesser standard of evidence and donation did not proceed.

Assuming that the potential donor had not changed their decision from opt-in to opt-out, it appears that some family members were not able to put their own negative views on organ donation aside. Similarly, Shaw describes scenarios whereby family members objected to organ donation and deemed consent specifically.13 We found that family members have yet to accept ‘doing nothing’ (deemed consent) as a positive decision in support of organ donation. The fact that the consent rate obtained via deemed consent is the same as the overall consent rate is an important and reassuring finding. There was some support for Shaw’s assumption that families are more likely to overrule a consent that is merely presumed (the equivalent of deemed consent in Wales) in that post implementation family support for an expressed decision made in life (87.2% 89/102) was higher than for a deemed decision (60.8% 28/46).14 Nonetheless, post implementation, overall consent rates were brought down by the low rate of family consent for children, and potential donors who did not have mental capacity or meet residency criteria (34.7% 8/23).

The Act contains provision whereby a person can appoint a representative on the organ donor register to convey their donation decision when they die. Only 33 people had appointed a representative during the timeframe of the study (now risen to 35) and none were called on during the first 18 months. If people are concerned that their relatives may not honour their donation decision, then appointing a representative may mitigate this relatively common situation. There is no appetite in Wales to introduce a hard opt-out system that removes the family from the decision-making process. Family members may however benefit from additional education to further clarify that it is not their decision to make and that their role is to support the donation decision made in life by their relative. Families do however have the right to override their relative’s donation decision in a soft opt-out system. The rate of family overrides needs monitoring in the long-term to determine if the observed upward trend is a cause for concern that requires further investigation.

At an individual potential donor level it has been made easier to convey a decision to donate organs. Sixty per cent of cases were either registered on the organ donor register or had discussed their donation decision with family member(s), and as of March 2018, 39% of the population are registered to opt-in to donate on the organ donor register. Any fears that introducing an opt-out system would cause a backlash by somehow changing the concept of the ‘gift’ of organ donation has not been realised. Only a relatively small number of people have thus far opted out (6%) on the organ donor register, and people are still opting in more than previously.

We performed a robust evaluation of initial impact based on bespoke routinely collected data on all cases. A more complex analysis was not performed given the small numbers involved in the first 18 months following introduction of the soft opt-out system and deemed consent in Wales. Small numbers, year on year fluctuations in potential deceased donors and consent rates, and health systems issues help explain why it has been difficult historically to establish if an opt-out system is the right option to introduce, and why increased consent rates have not yet translated into increased donor numbers. In Spain, it took 10 years following introduction of a soft opt-out system and further reorganisation to achieve 80% consent rates and increased donor numbers.4–6 As a trial was not feasible, it was not possible to determine with certainty if the 60.8% (28/46) of families who supported deemed consent under the soft opt-out system would have given their consent anyway under the former opt-in system. Nor do we know for sure why overall consent rates dropped by 5% to 48.5% immediately prior to implementation of the Act. Nonetheless, since its introduction there has been a sustained recovery and a 12.5% improvement since 2013/2014. One explanation is that there was a high profile coroner’s case in Wales in December 2014, which received international attention.15 Donor numbers across the UK fell following the news coverage (the only year on year fall in donor numbers in the UK in the last decade). One additional hypothesis is that introducing a soft opt-out system created harm that caused the pre implementation drop. McCartney writing in the BMJ 9 suggested that ‘some or many of those opting out may have been willing to donate freely but not under uncertain legislation’. This was a view supported by patient and public representatives who co-produced the current study. In a separate analysis of media coverage,16 we found a change to a more positive and supportive tone after 1 December 2015 when the soft opt-out was fully implemented that aligns with a general trend in improvements to consent rates.

Discounted over 10 years, the costs were approximately £7.5 million to set up and maintain the infrastructure required to operate a soft opt-out system of organ donation, including business and system changes, the processing of opt-out requests, public communications and evaluation. An increase of one donor per year with associated increases in organ transplantations, would generate sufficient benefits for a soft opt-out system to more than pay for itself.17 With this in mind, further attention needs to be given to reducing the number of consented donors who do not proceed to donation. During the 18 months post implementation around 30% of consented donors did not proceed. Our process evaluation sheds more light on the issues that prevent donation proceeding, some of which are amenable to intervention to reduce this figure.

Our findings have important implications for other nations including the Netherlands, Scotland and England who have signalled an intention or decision to implement a soft opt-out system.18–21 Our process evaluation makes clear that there are many different issues that impact on whether or not a family supports their relative’s organ donation decision, which could be addressed. A longitudinal study is required to see if consent rates are maintained, continue to improve and subsequently reach the national UK target of 80% by 2020,22 and to monitor what happens to donor numbers. Having accumulated more data since the conclusion of this study, other NHSBT studies are underway which are looking into this. We also need to know and understand the specific reasons why 6% of people have opted out on the organ donor register.

Conclusion

We found that introduction of the soft opt-out reversed a decline and subsequently improved consent rates for deceased organ donation in Wales that were similar to other improvements in consent rates in the rest of the UK nations who had not implemented a soft opt-out system; and had no impact on donor numbers. While the soft opt-out system in Wales has been most successful in getting potential organ donors to register or verbally express their decision, or do nothing and have their consent deemed, it was primarily family member overrides and health systems issues that prevented support for their relative’s opt-in donation decision and successful donation.

Given the growing worldwide interest in introducing opt-out systems and the unclear long-term impact on consent and donation rates these findings should be considered by policymakers who may assume that soft opt-out systems by themselves simply need more time to have a meaningful effect on donation numbers.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Fiona Wellington: Head of Operations NHSBT for supporting the study. Christian Brailsford: NHSBT provided advice and support to agree a mutual data sharing agreement and negotiate NHS ethics and NHSBT RINTAG and NHSBT R&D processes. Pat Vernon (Policy Lead Welsh Government), Ian Jones (Research and Evaluation Lead), Caroline Lewis (Organ Donation Policy Manager) provided a government perspective and shared research carried out prior to implementation of the Act. Donald Fraser: Lead of the Wales Kidney Research Unit supported development of the funding application and served as independent Chair of the steering group. Carol Williams for undertaking Welsh language and some English interviews. Jo Mitchell for providing administrative support and transcription. Barbara Neukirchinger (intern), Natalie Roberts (intern). North West NHSBT Team: Kathryn Alletson, Ben Armstrong, Adam Barley, Helen Bullock, Angela Campion-Sheen, Laura Ellis-Morgan, Rebecca Gallagher, Sharon Hallam, Phil Jones, Andrew Mawson, Abi Roberts, Tracey Rhodes, Jane Monks, Emma Thirlwall, Dawn Lee, Nicky Hargreaves, Sue Duncalf. South Wales NHSBT Team: Lucy Barnes, Susie Cambray, Angharad Griffiths, Charlotte Goodwin, Guy Heathcote, Gail Melvin, Lisa Morgan, Nicola Newbound, Michelle Powell, Stephen Regan, Fiona Rogers, Kathy Rumbelow, Michael Tobin, Janet Woodley, Louise Colson, Sarah Beale, Bethan Moss. NHS staff: Sian Griffin (Consultant Nephrologist, Department of Nephrology and Transplantation), Katja Empson, Sam Sandow, Carl Stephenson (Clinical Leads Organ Donation), Francesca Stevens (Tissue Services NHSBT), Maggie Stratton (PR Officer NHSBT). Patient and public representatives: Jeanette Bourne and CRUSE Bereavement Care Cymru, who provided leaflets signposting bereavement support for participants. Sarah Thomas Centre for Sight and Sound, Janet Thickpenny Big Lottery, Gethin Rhys Churches Together in Wales, Michael Rhys, Janet Williams and Gloria Owen. Maria Mesa Women Connect First, Roon Adams Race Equality First, Michael and Jess Houlston Donor Family Network, Maria Battle Chair of Cardiff and Vale University Health Board, Anna Bates Believe, Llanelli Multicultural Network, Rita’s Café. Bethan Moss Team Manager for reviewing the NHSBT anonymised database and supporting data analysis. Lisa Welsh, team leader, Donor Records Department for ensuring packs, envelopes and consent forms were included in donor packs for the duration of the study. Keeping the research team updated and following up with postal follow ups. Gill Drisma, Manager Donor Records Department (DRD), NHSBT for helping set up the data collection process and ensuring support staff were kept up to date of the study. Lynne Woolcocks, Regional Office Manager, South Wales and South West Organ Donation and Transplantation for supporting the postal follow ups and coordinating with DRD to ensure all families had opportunity to participate in the study. A special thanks to all the families. Thank you for agreeing to share your stories so that we could learn from your experiences.

Footnotes

Contributors: JN: Chief Investigator conceptualised the idea, put the team together, designed the study and procedures and drafted manuscript. MS: Consultant Transplant and Organ Retrieval Surgeon, Clinical Lead for Transplantation, Cardiff and Vale Health Board—advised on key research team members and stakeholders to bring into the research team, proposed changes in the law and key research questions to address. KM: Formerly Regional Manager South Wales and South West, NHSBT and now Major Health Conditions Policy Team, Directorate of Health Policy, Health and Social Services Group, Welsh Government—advised on key changes to policy and practice, study design and processes, data collection tools and implementation of the study. PW: Regional Manager South Wales NHSBT advised on changes to policy and practice, study design and processes, data collection tools, and implementation and analysis of the study. AR: Specialist Nurse in Organ Donation NHSBT advised on the role of the Specialist Nurse in Organ Donation, study design and processes, data collection tools and implementation and analysis of the study. Leah Mclaughlin: Research Officer—finalised study procedures and data collection processes, designed the study documentation and logos and supported production of applications to the NHS REC and NHSBT R&D committees, undertook fieldwork and analysed data. SM and RC: Statisticians at NHSBT—undertook the statistical analysis. All authors contributed to drafting and agreed the final submitted manuscript.

Funding: The study was funded by Health and Care Research Wales. Project Reference 1129.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The protocol was approved on 23 October 2015 by NHSBT Research, Innovation and Technology Advisory Group (RINTAG). This approval included agreement to share anonymised NHSBT data. The study was approved by the Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 NHS Research Ethics Committee (IRAS number 190066; Rec Reference 15/WA/0414 on 25 November 2015) and the NHSBT Research and Development Committee (NHSBT ID: AP-15-02 on 24 November 2015).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Additional unpublished data are not publicly available.

Author note: Original Protocol: JN, KM, PW, AR, LM, MS. Family attitudes, actions, decisions and experiences following implementation of deemed consent and the Human Transplantation (Wales) Act 2013: mixed-method study protocol. BMJ Open. 2017 Oct 12;7(10):e017287. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017287.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. https://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/what-we-do/transplantation-services/organ-donation-and-transplantation/ (Accessed 10th Apr 2018).

- 2. NHS Blood and Transfusion (2014) Cost-Effectiveness of Transplantation. http://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/newsroom/fact_sheets/cost_effectiveness_of_transplantation.asp (Accessed 11th Apr 017).

- 3. Welsh Government. Taking Organ Transplantation to 2020 – Wales Action Plan A plan up to 2020 for NHS Wales and its Partners Ensuring every organ donation counts. http://gov.wales/docs/dhss/publications/140107organactionen.pdf (Accessed 10 th Apr 2018).

- 4. Noyes J, Morgan K, Walton P, et al. Family attitudes, actions, decisions and experiences following implementation of deemed consent and the Human Transplantation (Wales) Act 2013: mixed-method study protocol. BMJ Open 2017;7:e017287 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Palmer M. Opt-out systems of organ donation: International evidence review. Social research Number: 44/2012 Welsh Government, Cardiff. 2012. http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/Documents/773/Organ%20Donation%20consultation%201doc%20-%20English.pdf.

- 6. https://www.bma.org.uk/collective-voice/policy-and-research/ethics/organ-donation Accessed 10th Apl 2018.

- 7. https://www.mirror.co.uk/lifestyle/health/two-thirds-back-mirrors-call-9930752 Accessed 10th Apl 2018.

- 8. Bramhall S. Presumed consent for organ donation: a case against. The Annals of The Royal College of Surgeons of England 2011;93:270–2. 10.1308/rcsann.2011.93.4.270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McCartney M. Margaret McCartney: When organ donation isn’t a donation. BMJ 2017;356:j1028 10.1136/bmj.j1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Human Transplantation Act. Wales. 2013. http://www.legislation.gov.uk/anaw/2013/5/contents/enacted (Accessed 10th Apr 2018).

- 11. Young V. Sarah McHugh and Richard Glendinning and Professor Roy Carr-Hill. Evaluation of the Human Transplantation (Wales) Act: Impact Evaluation Report. Cardiff, Wales: Welsh Government; SOCIAL RESEARCH NUMBER: 71/2017 PUBLICATION DATE: 30/11/2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12. IBM SPSS Statistics V22.0. 2018. Accessed https://ibm-spss-statistics-base.en.uptodown.com/windows.

- 13. Shaw D. Presumed consent to organ donation and the family overrule. J Intensive Care Soc 2017;18:96–7. 10.1177/1751143717694916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shaw D. Presumed evidence in deemed consent to organ donation. J Intensive Care Soc 2018;19:2–3. 10.1177/1751143717734694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kidney deaths inquest: No criticism over transplant deaths. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-south-east-wales-30323602 (Accessed 28th Apr 2018).

- 16. Dallimore DJ, McLaughlin L, Williams C, et al. Media content analysis of the introduction of a "soft opt-out" system of organ donation in Wales 2015-17. Health Expect 2019. 10.1111/hex.12872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Human Transplantation (Wales) Bill. Explanatory Memorandum incorporating the Regulatory Impact Assessment and Explanatory Notes (Costs and benefits: Costs of a soft opt-out System page 41). http://www.assembly.wales/laid%20documents/pri-ld9121-em-r%20%20revised%20explanatory%20memorandum%20human%20transplantation%20(wales)%20bill-25062013-247379/pri-ld9121-em-r-e-english.pdf (Accessed 30th Apr 2018).

- 18. https://www.bmj.com/content/360/bmj.k768.short?utm_source=trendmd&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=tbmj&utm_content=consumer&utm_term=0-A (Accessed 10th Apr 2018).

- 19. https://www.holyrood.com/articles/news/soft-opt-out-organ-donation-scheme-be-introduced-scotland (Accessed 10th Apr 2018).

- 20. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/dec/12/jeremy-hunt-launches-opt-out-organ-donation-plans-in-england-and-wales (Accessed 10th Apr 2018).

- 21. https://www.bmj.com/content/360/bmj.k768 (Accessed 10th April 2018).

- 22. NHSBT. Taking Organ Transplantation to 2020. http://www.nhsbt.nhs.uk/to2020/resources/nhsbt_organ_donor_strategy_long.pdf (Accessed 10th Apr 2018).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.