Abstract

Introduction

The purpose of this study is to assess the efficacy of electroacupuncture (EA) to relieve pain and promote functional rehabilitation after total knee surgery.

Methods and analysis

We propose a single-blinded, randomised placebo-controlled trial to evaluate the efficacy of EA. Patients with osteoarthritis (aged 55–80 years) undergoing unilateral total knee arthroplasty (TKA) will be included in the trial. They will be randomised to receive either EA or sham-EA. A total of 110 patients will receive EA and sham-EA for 3 days after TKA. Postoperative pain will be measured using visual analogue score, and the need for an additional dose of opioid and analgesics will be recorded as the primary outcome. Secondary outcomes include knee function and swelling, postoperative anxiety, postoperative nausea and vomiting among other complications.

Ethics and dissemination

This study has been approved by the ethics committee, and subsequent modifications of the protocol will be reported and approved by it. Written informed consent will be obtained from all of the participants or their authorised agents.

Trial registration number

ChiCTR1800016200; Pre-results.

Keywords: electroacupuncture, postoperative pain, total knee arthroplasty, the study protocol

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study is the first single-blinded, randomised placebo-controlled trial in China to assess the efficacy of electroacupuncture (EA) to relieve pain and promote functional rehabilitation after total knee surgery.

The study will use an efficient sham-EA method that makes it hard for patients with EA treatment experience to distinguish between both treatments.

The study is rigorously designed, which includes adequate sample size, proper randomisation and allocation concealment, and prospective trial registration to reduce selection and confounding bias.

There is still bias in the implementation of blind method due to the unblinded acupuncturists.

Introduction

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) is the most frequently performed surgical procedure for end-stage osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Moderate to severe postoperative pain is a major complaint in most patients. Acute and subacute postoperative pain is highly associated with persistent postsurgical pain (PPSP), especially when the acute pain is not treated with effective analgesia.1 A recent study showed that 10%–34% and 7%–23% of patients reported severe pain after TKA and total hip arthroplasty, respectively, which indicates that TKA patients are more likely to develop PPSP.2 Multimodal analgesia has been used for 20 years and it is considered to be the most effective strategy for PPSP. Abuse of analgesic drugs has increased exposure of the public to the side effects of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and opioids.3 4 Drug-free interventions to reduce pain or opioid consumption are more consistent with the principles of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS).

Clinical trials and systematic reviews have shown that the efficacy of electroacupuncture (EA) or acupuncture analgesia is controversial.5–8 Electrotherapy and acupuncture have been proved to be potentially beneficial for postoperative pain after TKA.9 Studies on the mechanism of EA analgesia indicated that it activates many bioactive chemicals through peripheral, spinal and supraspinal mechanisms.10 The supraspinal mechanisms showed EA analgesia is highly associated with descending pain regulation of the periaqueductal grey (PAG) and the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM).10 11 The PAG–RVM system is recognised as the central site of action of analgesic agents including opioids, cyclooxygenase inhibitors and cannabinoids.12 13 We hypothesise that EA may exert an analgesic effect by activating the PAG–RVM system. Because the mechanism of EA analgesia is not clear, there are also opinions that pain relief may be due to expectation or placebo effects.8 Besides, placebo analgesia is highly associated with both areas of the brain.14–16 Strict blinding and placebo-controlled are required to rule out the effects of the placebo effect on outcomes.

The purpose of this study is to assess the efficacy of EA on pain relief and promoting functional rehabilitation after total knee surgery. We will use a large sample size and a reliable blind method of EA to ensure a credible conclusion.

Methods and analysis

Study context

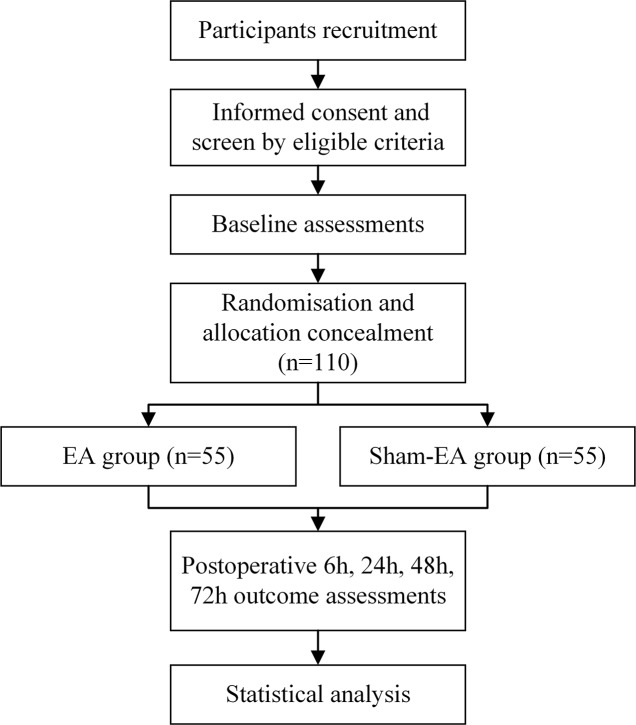

This study will be a single-blinded, randomised placebo-controlled trial performed at the inpatient ward of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Guanghua Hospital, Shanghai, China. The annual surgical number of TKA for osteoarthritis was about 600 in 2017. We planned to begin recruiting patients from June 2018 and patients preparing for unilateral TKA will be recruited. In this study, there will be seven investigators, including a chief orthopaedic surgeon (L-bX) with 20 years of clinical experience, two orthopaedic physicians (JX and SZ), two Chinese medicine acupuncturists (HH and Y-lC) and two outcome assessors (LZ and X-lS). SZ and HH will recruit patients who meet the inclusion criteria in the hospital and introduce the patient to the trial process, possible benefits and risks to obtain their informed consent. ERAS programme (table 1) will be performed by trained nurses and physiotherapists at the inpatient ward. The ERAS programme is routinely applied, but EA has been added to analgesia. The schedule and the study flow diagram are shown in table 2 and figure 1.

Table 1.

Enhanced recovery after surgery programme

| Preoperative | |

| 1 | Preoperative education |

| 2 | Carbohydrate loading preoperatively and avoidance of prolonged starving |

| 3 | Use of preoperative probiotics |

| 4 | No mechanical bowel preparation |

| 5 | No premedication |

| 6 | Pre-emptive analgesia |

| Intraoperative | |

| 7 | Maintenance of normothermia |

| 8 | Goal-directed perioperative fluid administration |

| 9 | Minimally invasive incision |

| 10 | Avoidance of nasogastric tubes and deep vein catheterisation |

| 11 | Avoidance of bladder catheters, if necessary early removal of bladder catheters |

| 12 | Use of tranexamic acid |

| 13 | Periarticular local injection analgesia |

| Postoperative | |

| 14 | Multimodal analgesia: PCA analgesia and NSAIDs; avoidance of opioid analgesia |

| 15 | Use of postoperative antiemetic and laxatives |

| 16 | Enforced early mobilisation |

| 17 | Enforced early postoperative oral feeding |

NSAIDs, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia.

Table 2.

The schedule of trial enrolment, interventions and assessments

| Enrolment | Intervention period | ||||

| Pre-OP | 6 hours | 24 hours | 48 hours | 72 hours | |

| Enrolment | |||||

| Informed consent | ● | ||||

| Assessment of eligibility | ● | ||||

| Randomisation | ● | ||||

| Interventions | |||||

| EA | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Sham-EA | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| Assessments | |||||

| VAS | ● | ● | ● | ● | ● |

| Additional dose released by PCA | ● | ||||

| HSS scale | ● | ● | |||

| HAMA score | ● | ● | |||

| PONV | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

| COK | ● | ● | |||

| Additional use of analgesics | ● | ● | |||

| Postoperative complications and adverse events | ● | ● | ● | ● | |

COK, circumference of knee; EA, electroacupuncture; HAMA, Hamilton Anxiety Scale; HSS, Hospital for Special Surgery; OP, operation; PCA, patient-controlled analgesia; PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; VAS, visual analogue score.

Figure 1.

The study flow diagram, including participants' recruitment, eligibility, screening, randomisation, allocation concealment and outcome assessments. EA, electroacupuncture.

Sample size calculation

In a previous meta-analysis study in which pain relief was compared between EA groups and controls, the minimal mean difference of the two groups based on the visual analogue score (VAS) (on a scale of 0–10) was −1.14 (95% CI −1.90 to −0.38), and the SD was estimated to be 2.9 Considering a dropout rate of 10%, 110 patients are required to yield a power of 80% with a significance level of 0.05.17

Randomisation and allocation concealment

One hundred and ten patients will be divided into EA and Sham-EA groups with a ratio of 1:1. An independent biostatistician will generate a random sequence using the R V.3.4.4. A sequence of numbers will be prepared and sealed in an opaque envelope. Only the acupuncturist will be allowed to open the envelope to obtain the grouping code.

Single-blinding

The acupuncturist will be blinded to the grouping information in advance, and the treatment method according to the grouping information contained in envelopes. All participants, orthopaedic surgeons and relevant healthcare staff will be blinded to the study. The outcome assessor will not be aware of the treatment that patients received and will only instruct the patient to fill in the scales. The independent biostatistician will also be blinded when performing the statistical analyses. To maximise the blinding of patients, an effective sham-EA method will be applied with adhesive pads, a dull-tipped placebo needle and a sham electrical stimulation device. Details of the sham operation design are described in the part of study interventions.

Eligibility criteria

Eligible

(1) Aged 55–80 years; (2) meet the 1995 American College of Rheumatology diagnostic criteria for osteoarthritis; (3) undergoing unilateral TKA under general anaesthesia without surgical contraindications and (4) American Society of Anesthesiologists grade I or II.

Ineligible

(1) The area of acupuncture points has skin damage and cannot perform acupuncture; (2) preoperative deep venous thrombosis or swelling of the lower extremities; (3) severe arrhythmia, heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, epilepsy and mental disease and (4) received treatment of acupuncture in past 1 month.

Study interventions

EA group

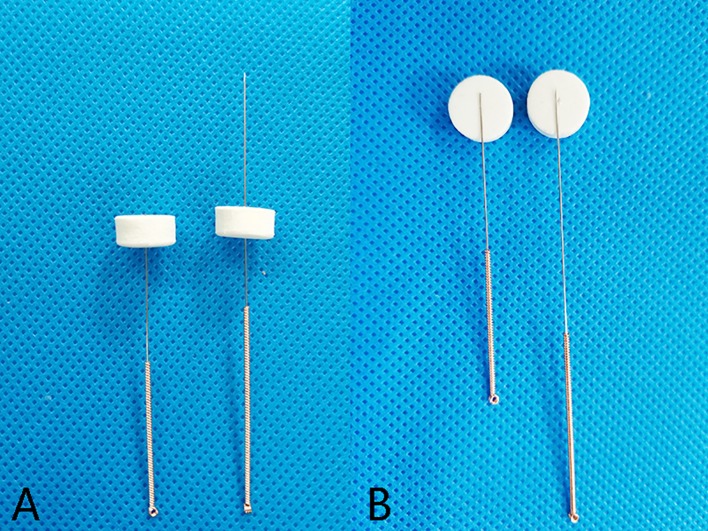

Patients will receive early acupuncture analgesia once a day from 24 to 72 hours after surgery. The first session of acupuncture treatment will be performed at 24 hours postoperatively. First, the adhesive pads will be put on the acupoints of bilateral Futu (Stomach 32, ST32), Zusanli (Stomach 36, ST36), Yanglingquan (Gall Bladder 34, GB34) and Yinlingquan (Spleen 9, SP9). The 1.5 cun acupuncture needles (0.25×40 mm, Huatuo Inc.) will be manually inserted into the skin through the adhesive pads (figure 2). When De-qi sensation is achieved, subsequent electrical stimulation with a frequency of 2 Hz, a continuous wave and tolerable intensity by the patient will be applied to the four acupoints (GB 34 to ST32 and ST36 to SP9) using a Hwato SDZ-V electrical stimulation device (Suzhou Medical Appliance Factory, Suzhou, China). Needles with electrical stimulation will be retained for 20 min in each session. The patients will receive a total of three treatments, which were given once a day.

Figure 2.

The difference between the acupuncture needle and placebo. (A) The placebo needle (left) to be inserted into the adhesive pads and the tip can irritate the skin. The acupuncture needle (right) to be inserted into the skin through the adhesive pads. (B) The tip of the placebo needle (left) is blunt.

Sham-EA group

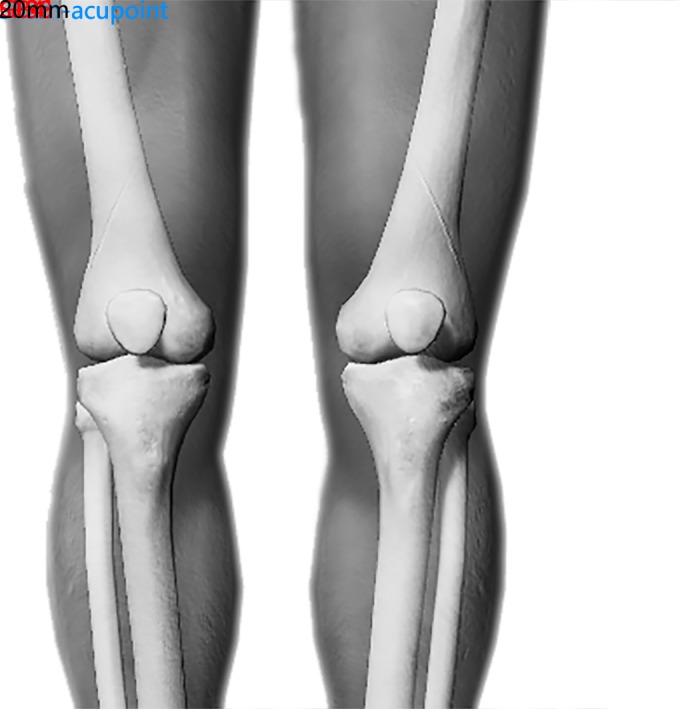

Similar to the EA group, three sessions of acupuncture will be provided at the same time. An adhesive pad will be put on the sham-acupoint, which is 20 mm distal to the real acupoint (figure 3). The placebo needle has a blunt-tip and it will be manually inserted into the adhesive pads but without skin penetration to provide participant-blinding effects (figure 2). The sham electrical stimulation device will have a connecting cord with a broken inner wire with no actual current output. Needles will also be retained for 20 min in each session. The patients will receive a total of three sham treatments, which were given once a day. This Sham-EA method was proved to be effective in a previous study.18

Figure 3.

Location of acupoints for the electroacupuncture and sham-electroacupuncture groups. GB4, gall bladder 34; SP9, spleen 9; ST32, stomach 32; ST36, stomach 36.

Postoperative analgesia

All patients will receive the same analgesic procedure. Fentanyl patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) will be used at a continuous infusion rate of 0.25 µg/(kg hour) and a bolus of 0.15 µg/kg with a 10 min lockout time. Patients will be allowed to use Celebrex 200 mg per day. Besides, additional rescue doses of analgesics will be provided on demand for patients with a VAS above 60.

Discontinuing criteria

(1) Acupuncture cannot be tolerated after surgery or patients that cannot be implemented according to the protocol; (2) severe physiological and pathological changes were found during surgery and it is not appropriate to receive acupuncture treatment, such as anaesthesia accidents, cardiac-cerebrovascular accidents and nerve or vascular injury during surgery; (3) patients in which the trial arrangement cannot be completed or the safety judgement is affected due to surgical factors after the test and (4) severe adverse reactions and severe complications, such as deep vein thrombosis, pulmonary embolism and severe allergic reactions.

Outcome

Primary outcome

Pain

When the patients are discharged from the operating room, this will be recorded as 0 hours. Patients will put a mark on a 100 mm visual analogue scale to assess the pain of their knee (from no pain to very severe) at 6, 24, 48 and 72 hours after surgery, then assessors record it. Additional PCA dose requirement will be evaluated in this study to reflect the degree of pain. Patients will be trained to adjust the PCA to obtain an additional dose of analgesia depending on the degree of pain. This will be recorded 48 hours after surgery. Patients will be given an additional dose of analgesia on demand if the VAS is above 60. The additional use of analgesics within 2 weeks after surgery will be recorded in the case report forms.

Secondary outcome

Knee function and swelling

Knee function will be measured based on Hospital for Special Surgery knee-rating scale19 (HSS scale) (online supplementary file) at 1 day before surgery and 3 days after surgery. All patients will first be educated about the HSS scale by a trained researcher until they fully understand the questionnaire, then asked to complete the form according to their actual conditions. At 24 hours after surgery, the outcome assessor will remove the elastic bandage and measure the circumference of the knee at the superior patellar pole. A second measurement will be performed 72 hours after surgery.

bmjopen-2018-026084supp001.pdf (372.6KB, pdf)

Perioperative anxiety

Perioperative anxiety will be measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA)20 (online supplementary file) at 1 day before surgery and 3 days after surgery. HAMA has 14 levels to assess the severity of a patient’s anxiety, and it divides anxiety into physical (7–13) and spiritual (1–6 and 14).

Postoperative nausea and vomiting

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) will be measured according to vomiting symptoms scores in four-time points, including on the day of surgery and 1, 2 and 3 days after surgery.21 Functional Living Index-Emesis22 (online supplementary file) is used to evaluate the effect of PONV on the quality of life, and it will be measured 3 days after surgery.

Postoperative complications and adverse events

All expected and unexpected adverse events will be measured during the allocated intervention process and during the entire study period. Acupuncture-related adverse events are haematoma and syncope during acupuncture. Other postoperative complications including incision infection, urinary retention, deep vein thrombosis and postoperative persistent pain will be recorded 6 weeks after surgery. All serious adverse events will be reported immediately to the sponsor to allow further investigations into their causes.

Data management

Data entry will be conducted by two independent trained research assistants using paper case report forms (CRFs) to record the research data after completion of final data collection. As acupuncture has known minimal risks, a formal data monitoring committee will not be required.8 23 Independent investigators of the hospital staff will monitor and audit the data periodically.

Statistical analysis

According to the intention-to-treat principle, full analysis set and per-protocol set will be used for primary analysis. Safety set will not be required since acupuncture has minimal risks.8 23 Sensitivity analysis will be performed to determine the impact of incomplete records on results. Missing data will not be imputed. Statistical analysis will be performed using R V.3.4.4. The difference between the two groups will be calculated and compared using the t-test if the Shapiro-Wilk test showed that the data is normally distributed, otherwise the Mann-Whitney U test will be used. A Pearson χ2 or Fisher’s exact test will be used to calculate the differences in the count data. Mixed effects models will be used to analyse the trend of changes in VAS with two factors of groups and time.24

Ethics and dissemination

Written inform consent will be obtained from all participants or their authorised agents. All EA treatments will be free and the research data will be strictly confidential. The result of the trial will be presented on the website of the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry and published in peer-reviewed journals.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design of this study. The participants will be informed of the result of this study during the follow-up visit. Besides, we will enlist their help in disseminating the research findings.

Discussion

Drug-free interventions, especially EA, have been proven effective in pain relief and promoting functional rehabilitation,25 26 and they will have good prospects for relieving opioid abuse or overuse of NSAIDs. However, the effect and mechanism of acupuncture analgesia are not clear, and the placebo effect is considered to play an important role.8 This study has enough samples to obtain reliable results and we have improved the implementation of blinding to adequately characterise the placebo effect. We hope that the results of the study will provide new evidence for EA treatment of postoperative pain in TKA. Another question is to determine if the statistical difference between the two groups is clinically relevant. The minimal clinically important difference (MCID) is a measure that is used to evaluate the clinical significance of an intervention. In the case of standardised multimodal analgesia, the MCID for VAS of postoperative pain after TKA is −22.6 (on a scale of 0–100), and the MCID can be also used to evaluate the difference of EA and sham.27

Multiple evidence-based ERAS strategies for TKA have been shown to reduce postoperative complications and improve prognosis and patient satisfaction. Postoperative analgesia is an important part of ERAS. This study is based on add-on design, EA and sham are applied to two groups of patients who used standard multimodal analgesia to evaluate the benefits of EA on postoperative pain in TKA. We recommend EA and more non-drug therapies as a routine treatment in ERAS programme of TKA if the results indicate effectiveness over placebo.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: SZ and L-bX conceived the study, while HH, JX, LZ and X-lS designed the study. The study protocol was drafted by SZ and L-bX, and was revised by Y-lC. All authors approved the final manuscript of this study protocol.

Funding: This work will be supported by the Project of Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine Grant (Y201812).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: This study has been approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai Guanghua Hospital of Integrated Chinese and Western Medicine (approval number AF13v2-2), and any modification of the protocol will be reported and approved by it.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Veal FC, Bereznicki LR, Thompson AJ, et al. Subacute pain as a predictor of long-term pain following orthopedic surgery: an Australian Prospective 12 Month Observational Cohort Study. Medicine 2015;94:e1498 10.1097/MD.0000000000001498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Beswick AD, Wylde V, Gooberman-Hill R, et al. What proportion of patients report long-term pain after total hip or knee replacement for osteoarthritis? A systematic review of prospective studies in unselected patients. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000435 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Han C, Li X-dan, Jiang H-qiang, et al. The use of gabapentin in the management of postoperative pain after total knee arthroplasty. Medicine 2016;95:e3883 10.1097/MD.0000000000003883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Katz J, Buis T, Cohen L. Locked out and still knocking: predictors of excessive demands for postoperative intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Can J Anaesth 2008;55:88–99. 10.1007/BF03016320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li X, Wang R, Xing X, et al. Acupuncture for Myofascial Pain Syndrome: A Network Meta-Analysis of 33 Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Physician 2017;20:E883–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Peng L, Zhang C, Zhou L, et al. Traditional manual acupuncture combined with rehabilitation therapy for shoulder hand syndrome after stroke within the Chinese healthcare system: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehabil 2018;32:429–39. 10.1177/0269215517729528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ju ZY, Wang K, Cui HS, et al. Acupuncture for neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;12:CD012057 10.1002/14651858.CD012057.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2010:CD001977 10.1002/14651858.CD001977.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tedesco D, Gori D, Desai KR, et al. Drug-Free Interventions to Reduce Pain or Opioid Consumption After Total Knee Arthroplasty. JAMA Surg 2017;152:e172872 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.2872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhang R, Lao L, Ren K, et al. Mechanisms of acupuncture-electroacupuncture on persistent pain. Anesthesiology 2014;120:482–503. 10.1097/ALN.0000000000000101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhao ZQ. Neural mechanism underlying acupuncture analgesia. Prog Neurobiol 2008;85:355–75. 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2008.05.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pogatzki-Zahn EM, Segelcke D, Schug SA. Postoperative pain-from mechanisms to treatment. Pain Rep 2017;2:e588 10.1097/PR9.0000000000000588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Leith JL, Wilson AW, Donaldson LF, et al. Cyclooxygenase-1-derived prostaglandins in the periaqueductal gray differentially control C- versus A-fiber-evoked spinal nociception. J Neurosci 2007;27:11296–305. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2586-07.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Tinnermann A, Geuter S, Sprenger C, et al. Interactions between brain and spinal cord mediate value effects in nocebo hyperalgesia. Science 2017;358:105–8. 10.1126/science.aan1221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grahl A, Onat S, Büchel C. The periaqueductal gray and Bayesian integration in placebo analgesia. Elife 2018;7 10.7554/eLife.32930 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Eippert F, Bingel U, Schoell ED, et al. Activation of the opioidergic descending pain control system underlies placebo analgesia. Neuron 2009;63:533–43. 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chow SC, Wang H, Shao J. Sample size calculations in clinical research. Second Edition: Taylor & Francis, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu Z, Liu Y, Xu H, et al. Effect of electroacupuncture on urinary leakage among women with stress urinary incontinence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2017;317:2493 10.1001/jama.2017.7220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bach CM, Nogler M, Steingruber IE, et al. Scoring systems in total knee arthroplasty, 2002:184–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol 1959;32:50–5. 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hesketh PJ, Kris MG, Grunberg SM, et al. Proposal for classifying the acute emetogenicity of cancer chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:103–9. 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.1.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lindley CM, Hirsch JD, O’Neill C V, et al. Quality of life consequences of emesis. Qual Life Res 1992;1:331–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Witt CM, Pach D, Brinkhaus B, et al. Safety of acupuncture: results of a prospective observational study with 229,230 patients and introduction of a medical information and consent form. Forsch Komplementmed 2009;16:91–7. 10.1159/000209315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Detry MA, Ma Y. Analyzing repeated measurements using mixed models. JAMA 2016;315:407–8. 10.1001/jama.2015.19394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chen G, Gu RX, Xu DD. [The application of electroacupuncture to postoperative rehabilitation of total knee replacement]. Zhongguo Zhen Jiu 2012;32:309–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yue C, Zhang X, Zhu Y, et al. Systematic review of three electrical stimulation techniques for rehabilitation after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2018;33:2330–7. 10.1016/j.arth.2018.01.070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Danoff JR, Goel R, Sutton R, et al. How Much Pain Is Significant? Defining the Minimal Clinically Important Difference for the Visual Analog Scale for Pain After Total Joint Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2018;33:S71–S75.e2. 10.1016/j.arth.2018.02.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026084supp001.pdf (372.6KB, pdf)