Abstract

Background and objectives

Many donors and recipients report an improved bond posttransplantation; however, unexpected conflicts and tension may also occur. Insights into the lived experiences of the donor–recipient relationship can inform strategies for interventions and support. We aimed to describe donor and recipient expectations and experiences of their relationship before and after living kidney donor transplantation.

Design, setting and participants

Semistructured interviews were conducted with 16 donor–recipient pairs before the transplant and 11–14 months post-transplant. Transcripts were analysed thematically.

Results

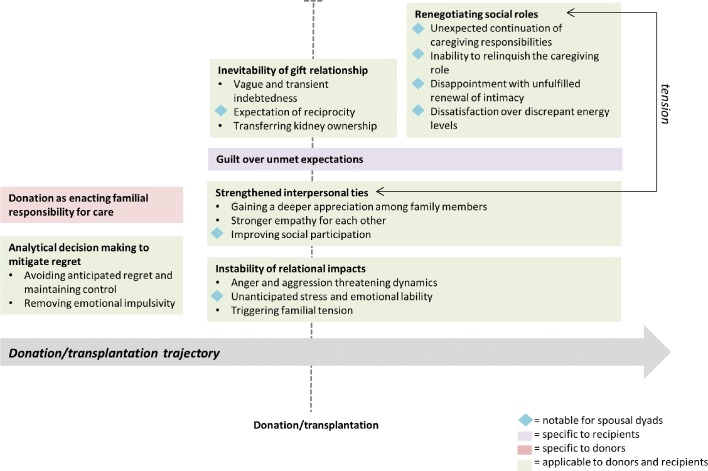

We identified seven themes (with respective subthemes): donation as enacting familial responsibility for care; analytical decision making to mitigate regret (avoiding anticipated regret and maintaining control, removing emotional impulsivity); strengthened interpersonal ties (gaining a deeper appreciation among family members, stronger empathy for each other, improving social participation); instability of relational impacts (anger and aggression threatening dynamics, unanticipated stress and emotional lability, triggering familial tension); renegotiating social roles (unexpected continuation of caregiving responsibilities, inability to relinquish the caregiving role, disappointment with unfulfilled renewal of intimacy, dissatisfaction over discrepant energy levels); guilt over unmet expectations and inevitability of the gift relationship (vague and transient indebtedness, expectation of reciprocity, transferring kidney ownership).

Conclusions

Donor–recipient relationships may be improved through increased empathy, appreciation, and ability to participate in life together; however, unfulfilled expectations and behavioural and emotional changes in recipients (a side effect related to immunosuppression) remain unresolved consequences of living kidney donor transplantation. Education and counselling to help donors and recipients adjust to potential changes in relationship dynamics may help protect and foster relational stability postdonation.

Keywords: qualitative research, kidney donation, renal transplantation

Strengths and limitations of this study.

We conducted longitudinal interviews with the same donor–recipient dyads prior to donation/transplantation and then 1 year later, and this provided access to changes in perspectives and experiences of the donor–recipient relationship in ‘real-time’.

We used thematic analysis to identify seven themes (and respective subthemes) and discuss their interrelationship.

All participants were English-speaking, aged ≥18 years and the majority had attained a tertiary level of education; thus, transferability of these findings to other contexts remains unclear.

Introduction

Living kidney donor transplantation confers superior survival and quality-of-life benefits for most patients with end-stage kidney disease compared with dialysis.1 Rates of living kidney donor transplantation have risen worldwide, comprising approximately 30%–50% of all kidney transplants in high-income countries, with the majority of donors being parents, spouses or siblings.2–5 While quality of life can improve for many recipients,6–8 donors and recipients have to renegotiate their social roles, identity and relationships.8 9

Living kidney donation can strengthen the donor–recipient relationship, characterised by greater perceived emotional support and a unique emotional connection.8 10 However, some donor–recipient dyads have reported donation-related conflict and tension, marked by feelings of rivalry, abandonment, guilt, disappointment, anger and jealousy.10–13 Poor family dynamics are associated with posttransplant depression and decreased social functioning in recipients of a living kidney donor transplant, to a greater extent than in recipients of deceased donation.14 In a recent study,15 living kidney donors prioritised the donor–recipient relationship as the fifth most important outcome of donation (out of 35 identified outcomes), even above overall life satisfaction, mortality, pain and kidney failure. Yet, there are limited data on the donor–recipient relationship.

Clinicians regard evaluating the donor–recipient relationship as ethically necessary to minimise the risk of undue coercion.16 The donor–recipient relationship after donation is variable across dyads8 12 17; however, little is known regarding the mechanisms underlying such differences, and how dyads perceive pathways to relationship outcomes. Most studies have focused on living kidney donor perspectives postdonation8 17–19; insight into the lived experience of the donor–recipient relationship from their perspective before and after donation is limited. We aimed to collect longitudinal data on donor and recipient expectations and perspectives of their relationship in living kidney donor transplantation, which may inform strategies to mitigate risks of relationship tension and conflict and support relationship resilience, thereby contributing to improved outcomes in living kidney donor transplantation.

Materials and methods

Participant selection

Living kidney donors and their recipients were recruited by transplant coordinators and nephrologists from three transplant units in Sydney, Australia. They were purposively selected to ensure a range of demographic (including age, gender, donor relationship) and clinical (including dialysis modality, comorbidities) characteristics. Participant pairs were eligible if they comprised a spousal, sibling, or parent living kidney donor (as approximately 70% of live donations in the USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand are from spouses or biologically related donors2 4 20) and a recipient with a confirmed transplant date. All participants had to be English speaking, >18 years of age, and able to give written informed consent. Western Sydney Local Health District (LHD), Sydney LHD and South-Eastern Sydney LHD approved the study.

Data collection

The interview guide was developed based on a systematic review of donor–recipient perspectives10 and investigator input (online Supplementary File 1). One author (AFR) contacted consenting participants via phone (up to three attempts) and/or email to schedule an interview. AFR conducted two longitudinal, individual semistructured interviews with each participant individually, during the month prior to their donation/transplant, and 11–14 months postdonation/transplant. The interviews were conducted face-to-face in their home, office or dialysis unit, or via telephone if this was not possible. AFR was not previously known to participants, not involved in their clinical care. Participant recruitment ceased when theoretical saturation was reached (ie, no new concepts were raised in subsequent interviews). Interviews averaged 30 min in duration and were audio-taped and transcribed.

bmjopen-2018-026629supp001.pdf (58.1KB, pdf)

Analysis

Using the principles of grounded theory21 and thematic analysis,22 AFR read through the transcripts and inductively identified preliminary concepts. The transcripts were entered into data management software HyperRESEARCH V.3.7.3 (ResearchWare Inc, Randolph, Massachusetts, USA), where AFR reviewed the transcripts line-by-line (by dyads) and coded emerging concepts. AFR and AT met frequently to refine the coding structure. The emergent findings across all dyads were compared. Similar concepts were grouped into themes, and patterns between themes and subthemes were identified and mapped into a thematic schema. As a form of investigator triangulation, authors TG, CSH and AJ also read the transcripts and reviewed the themes to ensure that the findings reflect the full range and depth of the data and enhance the analytical framework.

Patient and public involvement

The donor–recipient relationship has been identified as a research priority by patients23; however, patients were not involved in the design of this study. On publication of this manuscript, a summary of the study results will be disseminated back to the participants.

Results

Of the 28 donor–recipient pairs approached, 16 pairs participated. Reasons for non-participation included lack of time and avoiding the risk of jeopardising the stability of their relationship prior to the transplant. From October 2014 to June 2017, we conducted 32 pretransplant interviews (16 donors, 16 recipients) and 29 posttransplant interviews (14 donors, 15 recipients). One pair was excluded from the postdonation interviews as the recipient received a deceased donor kidney, and one donor could not be contacted for the second interview. The characteristics of participants are shown in tables 1 and 2. Nine (56%) donors and 11 (69%) recipients were male. Eight (50%) were spousal dyads in which four donors were female, five (31%) were sibling pairs, and three (19%) were parent–child dyads. On average, each interview was 30 min in duration, and 53 (87%) interviews were conducted in-person.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the participants (total n=32)

| Characteristics | Donors, n (%) | Recipients, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 9 (56) | 11 (69) | 20 (64) |

| Female | 7 (44) | 5 (32) | 12 (38) |

| Country of origin | |||

| Australia | 12 (75) | 14 (88) | 26 (81) |

| Other* | 4 (25) | 2 (13) | 6 (19) |

| Age (years) | |||

| 20–39 | 1 (6) | 2 (12) | 3 (9) |

| 40–49 | 4 (25) | 5 (31) | 9 (28) |

| 50–59 | 5 (32) | 3 (19) | 8 (25) |

| 60–69 | 3 (19) | 5 (32) | 8 (25) |

| 70–79 | 3 (19) | 1 (6) | 4 (13) |

| Ethnicity | |||

| Anglo Celtic | 13 (81) | 13 (81) | 26 (81) |

| Other European | 2 (13) | 2 (13) | 4 (13) |

| Aboriginal | 1 (6) | 1 (6) | 2 (6) |

| Highest level of education | |||

| Secondary | 4 (25) | 6 (38) | 10 (31) |

| Tertiary—certificate/diploma | 3 (19) | 3 (19) | 6 (19) |

| Tertiary—undergraduate degree | 6 (38) | 4 (25) | 10 (31) |

| Tertiary—postgraduate degree | 3 (19) | 3 (19) | 6 (19) |

| Religion | |||

| Christianity | 8 (50) | 12 (75) | 20 (63) |

| No religion | 7 (44) | 3 (19) | 10 (31) |

| Buddhism | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 1 (3) |

| Other | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Employment status† | |||

| Full time | 5 (32) | 9 (57) | 14 (44) |

| Part time/casual | 4 (25) | 1 (6) | 5 (16) |

| Retired/pensioner | 6 (38) | 4 (25) | 10 (31) |

| Not employed | 0 (0) | 2 (13) | 2 (6) |

| Marital status | |||

| Married/de-facto relationship | 13 (81) | 12 (75) | 25 (78) |

| Divorced/separated | 2 (13) | 2 (13) | 4 (13) |

| Single | 1 (6) | 2 (13) | 3 (9) |

*Other includes: Greece, New Zealand, The Netherlands, Zambia, Zimbabwe.

N =31 as one participant did not provide data.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the recipients (n=16)

| Characteristics | n (%) |

| Relationship to donor | |

| Wife/female spouse | 4 (25) |

| Husband/male spouse | 4 (25) |

| Son/son-in-law | 3 (19) |

| Brother | 3 (19) |

| Sister | 2 (13) |

| Time since diagnosis of kidney disease (years)* | |

| 1–9 | 2 (13) |

| 10–19 | 6 (38) |

| 20–29 | 5 (31) |

| 30–39 | 3 (19) |

| Comorbidities* | |

| Hypertension | 12 (75) |

| Diabetes | 2 (13) |

| Infections | 1 (6) |

| Cancer | 1 (6) |

| Other† | 5 (31) |

| Length of time on dialysis (all types) (years)* | |

| <1 | 4 (25) |

| 1–2 | 3 (19) |

| 3–5 | 3 (19) |

| >5 | 2 (13) |

| Not on dialysis (pre-emptive transplant) | 4 (25) |

| Dialysis modality (n=12)* | |

| In-centre haemodialysis | 6 (50) |

| Home haemodialysis | 3 (25) |

| Peritoneal dialysis | 3 (25) |

| Length of time on deceased donor waiting list (n=12) (years)* | |

| <1 | 1 (6) |

| 1–2 | 2 (13) |

| 3–5 | 1 (6) |

| >5 | 1 (6) |

| Not on list | 7 (44) |

| Received a previous kidney transplant | |

| Yes (deceased donor) | 1 (6) |

| No | 15 (94) |

*Self-reported at time of first interview.

†Other: bone disease, monoclonal gammopathy of unknown significance, osteoarthritis, wet macular degeneration, irritable bowel syndrome.

We identified seven themes: donation as enacting familial responsibility for care, analytical decision making to mitigate regret, strengthened interpersonal ties, instability of relational impact, renegotiating social roles, guilt over unmet expectations and inevitability of the gift relationship. The subthemes are described below, and quotations to illustrate each theme are provided in table 3. Figure 1 depicts a conceptual schema of the relationships among themes.

Table 3.

Selected illustrative quotations

| Theme | Illustrative quotations |

| Donation as enacting familial responsibility for care | |

| ‘It’s a continuation of the nurturing process… I just can’t let him down. I really don’t want to do it, to be honest, I really wish I didn’t have to do it…. You can’t let children die.’ (Female; Parent donor; T1) ‘I just can’t do nothing and just sit back and watch, no. I mean that’s the dynamics of my family as I like to see them… I thought, well, I’ve got to live with myself and if I don’t offer and turn out to be able to then I’d feel less of a human being in a way.’ (Male; Sibling donor; T1) ‘[The doctor] came to me and went absolute ballistic. Why did I bring somebody on a cruise ship who had renal failure? He must have had this for years. I must have known about it. What was I doing?’ (Female; Spousal donor; T1) | |

| Analytical decision making to mitigate regret | |

| Avoiding anticipated regret and maintaining control | ‘[X] who is the black sheep of the family, he’s also likely to go on dialysis shortly. I don’t think I’d ever do it [donate] for him, and that’s because he doesn’t look after himself in other ways… He’s not the sort of person I would trust to—certainly not as much as [recipient]—would trust to look after such a gift.’ (Male; Parent donor; T1) ‘My husband was willing to be tested, and seriously I ran a mile from that situation. Not because he’s not a wonderful man, not because I don’t love him, but my fear was, imagine having a fight with your partner and he would always be able to throw back, ‘But I gave you my kidney.’ You can never win that argument, so I always had this hesitancy.’ (Female; Sibling recipient; T1) ‘I think if my husband gave me his kidney… I would imagine that every time if I had one glass of champagne too many or I’m carrying too much weight, he would be like, ‘Oh, for God’s sake, I gave you a kidney so the least you can do is look after it.’' (Female; Sibling recipient T2) |

| Removing emotional impulsivity | ‘It was almost certain to go ahead if they [recipient and spouse] wanted it. But then I did it [offered to donate] by email, I sent them both an email at the same time, so I wanted them to have a chance to think about it, and come to get over their initial shock… I didn’t want to put them under pressure of being face-to-face, and I wanted them to have a chance to talk about it between themselves.’ (Male; Parent donor; T2) ‘I’m always concerned about how she’s [the donor] going to come out of the operation…and I’m concerned if it all goes through and it all happens and it’s all wonderful and then for some reason, the kidney fails, how she’d feel about that. I’ve spoken to her about it. She’s comfortable with it.’ (Male; Sibling recipient; T1) |

| Strengthened interpersonal ties | |

| Gaining a deeper appreciation among family members | ‘It’s actually made it [our relationship] stronger. It could have been really difficult but because we’ve done it together and everything we’ve done, we’ve done together. So all the doctors’ appointments, and there have been lots, all the testing, all the information sessions everything we’ve done together.’ (Female; Spousal donor; T2) ‘I suppose we’ve got closer in a sense, where we communicate much more than we would’ve in the past. It has been generalised to other things [than the transplant]. And they see me as part of their family now, a closer family kind of thing.’ (Female; Sibling donor; T2) |

| Stronger empathy for each other | ‘I look out for her health a bit more; what she eats and things like that; I don’t really say anything, but I monitor a bit. (Male, Child recipient; T2) ‘She has been sick for so long, and so when I was having all the tests done… it was such a tiny scrape on what she’s done her whole life, and it really made me appreciate what she has been going through. And I like I say it was a scratch.’ (Female; Sibling donor; T1) ‘I think it’s made us very sensitive that we’re very significant to each other and I think it’s made me treasure her a lot more.’ (Male; Spousal donor; T2) |

| Improving social participation | ‘It’s a selfish act as well, in a way… it’s giving her a better quality of life, but it’s giving us a better quality of life as well, together. And we can go on normal holidays, and travel or do whatever, without any problems.’ (Male; Spousal donor; T1) ‘I think [post-donation] we could experience some more shared interests, like I like to walk, and I’d like to be able to walk with him, but it’s a snail’s pace at the moment, so I accept that that’s the way it is, so I do those on my own… but I would like us to have a fitter and well-balanced life.’ (Female; Spousal donor; T1) ‘I hope to get back to being more active [post-donation]. And doing more work walking and bike riding, going on holidays, and going to visit my grandchildren. And just having more energy… Take up in life where we left off really, in a way.’ (Female; Spousal recipient; T1) |

| Instability of relational impacts | |

| Anger and aggression threatening to dynamics | ‘I can’t understand why he will explode about the fact that a tablet dropped on the floor and it’s about the fact that he’s shaking, and he can’t control certain things anymore when he used to be able to control them so that’s just really hard to adjust to.’ (Female; Spousal donor; T2) ‘If his personality is maybe a bit different because of the drugs that he’s on, if he ends up too difficult to live with, I could leave. Well when he got sick he was on a high dosage of prednisone and he was pretty difficult then.’ (Female; Spousal donor; T1) |

| Unanticipated stress and emotional lability | ‘You’d think we were an unhappy married couple who are constantly fighting. That’s how she’s been probably for the last year due to [the transplant]. Before that, we never fought. It’s got her uptight and panicking and worrying about she’d say things like she’s worried she’ll die on the operating table. She’s a panicker, a worrier.’ (Male; Spousal donor; T1) ‘We’ve had a few of those [arguments]… It has tested our relationship, but he’s never said, ‘Well I don’t want to do this,’ but I have said, ‘Stop it. Ring them up and tell them I don’t want it. I’m not doing it.’' (Female; Spousal recipient; T1) ‘I’ve actually found that’s one of the consequences of the operation. I’ve become more emotional… Just been getting chocked up. I nearly got chocked up then just talking to you about [my donor].' (Male; Sibling recipient; T2) |

| Triggering familial tension | ‘[My other Son], he just refused [to donate]. And that caused a lot of disharmony between us at the time. And I’ll really never forget it. It’s etched there indelibly because I remembered how he refused, and [the recipient], even though he’s over it now, he will never forget that fact. [The recipient] was bitterly hurt by it all.’ (Female; Parent donor; T2) ‘With my sister the other day…apparently I was being selfish, and I just lost it. I got very mad, and I had to leave…. The emotions involved, all the what-ifs? What if it fails after a week just wasted a bloody good kidney? Dad could have had that for another 40 years?’ It was just a lot of pressure.’ (Male; Recipient; T1) |

| Renegotiating social roles | |

| Unexpected continuation of caregiving responsibilities | ‘I think the fact that the recovery is not always 100% and it can still be a roller coaster ride as far as health goes. It has its emotional dimension and because of that it can still put strains on a relationship.’ (Male; Spousal donor; T2) ‘I’ve had to take the lead on that [the drug regime] because I think it all became too much for him at times. He’s a little bit more confused than he was before…I don’t know how he’d go if he had to do that on his own.’ (Female; Spousal donor; T2) |

| Inability to relinquish the caregiving role | ‘He insisted on driving me and I said, ‘Oh no, I can drive myself.’ It takes a real effort to do it [say ‘no’] without being hurtful. He’s was my carer while I was having dialysis because I didn’t feel well enough to drive home. He’s had this role of carer and I guess it’s maybe hard to give up.’ (Female; Spousal recipient; T2) ‘He [the recipient] suddenly was better one day and so he said, ‘Well, I’m off now. I’m going out for the day, and I’ll be gone,’ and I’ll just leave you there. Well, I was a bit miffed, but at the same time…I realised that was a good thing for me, but miffed, because you go, well, you just get up and go and leave me there now.’ (Female; Spousal donor; T2) |

| Disappointment with unfulfilled renewal of intimacy | ‘My relationship with [recipient], well, in some cases we do have a rather difficult relationship, but I’m aware of the problems because he’s become more of a carer, and that’s the—it’s a bit of a pity, because there’s no romance. No romance or love making.’ (Female; Spousal recipient; T2) ‘As far as sex goes, I am frightened to have sex because I’m on the immunosuppressants, every time I have sex I get a urinary tract infection. And I just don’t want them there, they’re too horrible and so I always decline it.’ (Female; Spousal recipient; T2) ‘’That [sexual problems] is so normal with what he’s got, so don’t worry about it,’ and she [the clinician] was actually the one to say as well, she goes, ‘Watch out when you do get your kidney, because then he’ll be like little teenager again,’ and oh yeah good. Let’s hurry this thing up now.’ (Female; Spousal donor; T1) |

| Dissatisfaction over discrepant energy levels | ‘I have got a whole big long list of interests there but he [recipient] doesn’t seem to have as many interests, he’s happier just to stay at home and do the gardening… I want to get out and about and be with people because I find it very stimulating and whereas he is not.’ (Female; Spousal donor; T2) ‘He’s become more of a carer…where he is happy to stay home, he’d be happy to stay home the rest of his life and not go anywhere, that’s what he’s like. But I don’t want to do that. I want to get out and about and involved in things. It is difficult when one person wants to go out more and have fun and the other person doesn’t. It’s a very difficult thing in a relationship.’ (Female; Spousal recipient; T2) |

| Guilt over unmet expectations | |

| ‘But if it went wrong and you think to yourself, oh shit, she’s given me her kidney and it’s all gone pear shaped. She’s out a kidney and nothing’s been achieved. I’ve stuffed it up, my body’s stuffed it up.’ (Male; Spousal recipient; T1) ‘Imagine the worst-case scenario he died on the table tomorrow. Imagine how I would feel and then having them [my family] blame me for the rest of my life.’ (Male; Child recipient; T1) ‘He’s [the recipient’s] extremely depressed, with the medication. He hasn’t got a job; therefore he’s depressed. I’m disappointed for him, but whilst my donation has nothing to do with that. I’m please I gave it to him, but I think it’s going to take a little longer for him to get up on his feet, but he feels guilty about taking my kidney.’ (Male; Parent donor; T2) | |

| Inevitability of the gift relationship | |

| Vague and transient indebtedness | ‘Can you put a monetary figure on it? And then if you do, what is it? Is it too much? Is it not enough? Is it a servitude thing? I don’t know. I’ve written an email to [recipient] and the family to tell them what I think of her and what I think of her gift.’ (Male; Sibling recipient; T1) ‘I think maybe I just do a few extra things [around the house] because I am a bit indebted. I feel that I have to be more careful with my health, because you’re carrying something precious. It’s not a really conscious thing, but it’s kind of a subconscious thing that’s there in the background. I don’t go I’m going to vacuum the whole house and do this and that, but I know I do try and help a bit more and do things.’ (Male; Spousal recipient; T2) ‘It’s obviously a gift but there’s still you still have thoughts that you still are beholden to your brother. Not that he’s ever said it but you get that feeling. You can’t not have those thoughts can you when someone in the family has given you such a massive gift. There’s no sort of real issue but obviously you still think about it.’ (Male; Sibling recipient; T2) |

| Expectation of reciprocity | ‘But I guess there’s implicitly, there’s always a sense of, understanding of what a gift implies from an obligation point of view, and I’ve tried to make that clear, from the time that we made the offer, it was understood it was an offer without any obligations. A concern I had at the time was that it might have affected our relationship, and I didn’t want it to do so, so I didn’t want any sense of obligation to be felt by the others.’ (Male; Parent donor; T2) ‘I thought it the other day, there was something that happened, and I thought well, you know I’m giving him a kidney, so he really should pay for this and now I thought to myself, I shouldn’t be thinking like this but I am.’ (Female; Spousal donor; T2) |

| Transferring kidney ownership | ‘It’s a gift. It’s his. I have no sense of it as my kidney… it’s totally his. If he decided to go binge drinking every night, I might be a little bit concerned, but I would anyway. So, yeah, that’s totally his business.’ (Female; Spousal donor; T2) ‘I just feel really strongly that I gave the kidney for him so that he can live his life, whatever that means. He’s like ‘I don’t want to ride my motorbike because I might crash and it’s a waste of your kidney’, I’m like, ‘It’s a waste of your kidney if you don’t do that’, it’s not my kidney anymore.’ (Female; Spousal donor) ‘I’ve been really careful to make sure that [the recipient] knows that I don’t want her to have any guilt associated with it at all. I’ve been letting her know that it’s okay to be her after the operation…if she actually wants to have a glass of wine, or if she wants to have, you know, lead a normal life.’ (Female; Sibling donor; T1) |

T1, predonation/transplantation interview; T2, postdonation/transplantation interview.

Figure 1.

Thematic schema. Donors and recipients both expected and experienced a strengthened emotional connection and an improved ‘combined’ quality of life. However, at the same time, some dyads were confronted with relationship conflict and tension, which were triggered or exacerbated by disappointment with unfulfilled expectations of posttransplantation life, and behavioural and emotional changes. Some donors and recipients were aware of the potential relationship strains such as anticipated guilt and indebtedness of the recipient prior to the transplant; however, some dyads were still confronted by these challenges of the one-sided ‘gift relationship’ postdonation, which affected their relationship.

Analytical decision making to mitigate regret

Avoiding anticipated regret and maintaining control

Some participants took into account tension, decisional regret and feelings of guilt when making decisions about donating or accepting a kidney. Recipients refused to accept donations from family members who they anticipated would use it against them in the future to ‘control situations’ such as to win arguments, to make them change behaviours (eg, drinking alcohol) or in a potential divorce settlement. Some donors did not want to regret donating and therefore did not want to donate to recipients who they perceived had either ‘contributed to [their] own kidney problems’ (eg, through excessive drinking) or had disappointed or hurt them as they did not ‘trust them to look after such a gift’.

Removing emotional impulsivity

To preserve the stability of their relationship, some participants approached their decision pragmatically. Some donor–recipient pairs communicated about all possible relationship consequences, including divorce, to ensure they were able to accept these risks. One donor completed his work-up without the knowledge of the recipient and then communicated his offer of donation via email to allow the recipient ‘a chance to absorb it’ so they would not feel obligated to respond immediately. The donor outlined a logical case for why he should be the donor and emphasised that the offer was ‘without strings’ to minimise potential disruption to their relationship.

Donation as enacting familial responsibility for care

Some donors viewed donation as a ‘continuation of the nurturing process’ for their family member, and this was intensified in mothers and wives. Some felt somewhat at fault for their recipient’s illness and felt compelled to donate. One mother felt ‘a little bit responsible [for her son’s kidney disease] that we didn’t have him checked out.’ Another donor reported that their clinician went ‘absolutely ballistic’ at her for not knowing that her spouse had kidney failure (prior to diagnosis). Some donors believed they would endure unbearable guilt if they did not take care of their family by donating a kidney.

Strengthened interpersonal ties

Gaining a deeper appreciation among family members

While some participants believed their relationship did not change posttransplant, others felt they developed an intangible ‘special bond’ and became closer through increased contact. Spousal dyads felt they had ‘seen the worst and best bits’ of each other through the ‘difficult process’ of donation and become stronger and more honest with each other. Some spousal dyads viewed the commitment of donation akin to marriage and became more aware of how their partner ‘treasured them’. Some donors felt that their recipient’s family members displayed a ‘warmer attitude’ and gratitude towards them.

Stronger empathy for each other

Some donors and recipients became more focused on each other’s well-being than their own. For some donors, the clinical workup was their first experience of undergoing medical tests and waiting in hospitals and they gained a newfound appreciation of the discomfort, uncertainty and inconvenience their recipient had experienced in hospital. Recipients viewed their donor as ‘brave’ but held concerns about their donor’s health (eg, kidney function, fatigue and potential cancers).

Improving social participation

Spousal pairs anticipated that recipients would have increased energy to participate in activities after transplant, giving them ‘a better life together’. They looked forward to being able to do activities together including travelling, walking, bike riding, going to the beach and dancing. For some pairs, these expectations were realised and they felt ‘happier’ and ‘stronger’ as a couple.

Instability of relational impacts

Anger and aggression threatening dynamics

Both donors and recipients worried about the potential impact of steroid medication (in particular, prednisone) on the recipient’s ‘personality’ and how this could affect their relationship. Recipients were concerned that they ‘would not be the same person’ on medication, and they may become angry, depressed, ‘grumpy and moody’ towards their partner. One spousal donor was worried that she may leave her recipient if ‘he ends up too difficult to live with’. After the transplant, donors felt stressed in having to cope with the anger and irritability experienced by their recipient—‘like waiting for a ticking time bomb to go off’.

Unanticipated stress and emotional lability

The upcoming transplant was a priority and consumed the time and energy of some spousal pairs who experienced increased tension and arguments, which they attributed to the stress of the donation process (eg, uncertainty regarding donor eligibility and waiting for transplant confirmation) and upcoming surgery. After donation, some recipients experienced exaggerated changes in mood and/or a reoccurrence of previous mental health disorders (including depression and bipolar disorders), which they believed were due to the stress, adjustment and steroids, and which affected their relationship.

Triggering familial tension

For some, in particular parent-to-child dyads, the donation became a source of stress in their relationships with other family members. Recipients experienced ‘snide comments’ from and arguments with other family members (eg, sibling, other parent or parent-in-law) who did not agree or were concerned for the donor. Such recipients felt this compounded their feelings of guilt and worry about the transplant. Donors and recipients also noted friction in their relationships with other family members who did not offer to donate. Some donors believed the donation triggered arguments within the extended family who challenged the donor’s motives and instigated family discussion of the Will of the recipient, especially in blended families.

Renegotiating social roles

Unexpected continuation of caregiving responsibilities

Spousal donors expected their role as a ‘caregiver’ to diminish posttransplant. For some donors whose recipient had complications and side effects (eg, BK virus, diabetes), they were disappointed in having to still bear caregiving responsibilities. They described recovery as a ‘rollercoaster’ which required them to exercise tolerance and patience towards their recipient.

Inability to relinquish the caregiving role

Some spousal recipients felt their donors wanted to continue caring for them posttransplant and were worried about hurting their donor’s feelings by informing them that they no longer required their assistance such as being driven to attend follow-up clinic. One spousal donor was offended when their recipient began to do activities alone (eg, shopping and exercise), which they had normally done together.

Disappointment with unfulfilled renewal of intimacy

Some spousal pairs eagerly anticipated improved physical affection and intimacy posttransplant, with one donor citing this as the primary reason for her donation. Recipients reported that clinicians advised them that increased libido was a side effect of steroid medication. However, some recipients were afraid to have intercourse while on immunosuppressants as this could result in urinary tract infections. For other recipients, intercourse was painful, or they did not experience increased libido. Some recipients did experience an increased libido but became frustrated when this was not matched by a similar change in their spousal donor. Recipients were reluctant to discuss their sexual concerns with their clinicians as they believed this would be regarded as peripheral to the primary focus on their health.

Dissatisfaction over discrepant energy levels

In some spousal pairs, the recipient’s vitality increased and surpassed that of their donor, shifting the relationship dynamic and causing relationship tension as the recipient wanted to engage in activities (eg, running, dancing and socialising) they had enjoyed prior to becoming unwell and to lead a more fast-paced and active lifestyle than their partner. Conversely, when recipients did not experience their expected ‘boost’ in vigour, donors felt disappointed and frustrated that they were unable to engage in their desired shared lifestyle.

Guilt over unmet expectations

Before the transplant, recipients worried that if their desired physical, psychological and social improvements were not achieved after the operation, they may feel regret and be blamed by others for accepting the kidney donation. Some recipients, despite having a successful transplant, did not feel ‘stronger and better’, often due to comorbidities, for example, diabetes. Such recipients felt they had failed their donors, were ‘wasting’ their donor’s kidney and efforts, and worried they would be blamed by their donor or other family members.

Inevitability of the gift relationship

Vague and transient indebtedness

Recipients were ‘eternally grateful’ to their donor and felt indebted to them; however, this was ‘a subconscious thing’ and ‘not a real issue’ and diminished over time. They believed the best way to show their appreciation was to look after their health and verbally thank the donor.

Expectation of reciprocity

Some spousal donors felt disgruntled that their recipient was not more openly appreciative of them. This mainly occurred when the donor was frustrated with their recipient, for example, for not supporting them in a family argument, not paying for something, or if they believed they were not making an effort in their relationship. However, donors felt uneasy and guilty about having such thoughts.

Transferring kidney ownership

Donors were conscious that the imbalance of the one-way gift had the potential to cause unease in their relationship and did not want their recipient to feel guilty. They conceptualised the kidney as a gift and were careful about how they discussed the kidney in front of the recipient and encouraged their recipient to participate in physical activities and not to be overly cautious. Donors and recipients recalled being told by clinicians ‘once it’s out of you it’s not yours anymore’. While some donors were initially anxious about the recipient’s health and wanted to ‘wrap them in cotton wool’, this lessened over time; they emphasised they had donated so their recipient could live life to the full.

Discussion

For donors and recipients, improved and strengthened relationships after living kidney donor transplantation were marked by increased closeness and appreciation of each other, stronger empathy, more frequent contact and enhanced quality of life as a pair. At the same time, some dyads were confronted with conflict and tension triggered or exacerbated by behavioural and emotional changes (anger, aggression, alterations in mood in recipients related to steroid use), and disappointment with unfulfilled expectations of recovery of health, re-establishing roles and renewal of intimacy. Some donors and recipients were aware of potential relational strains such as anticipated guilt and indebtedness of the recipient and changes in relationship dynamics because of the one-sided ‘gift relationship’, and donors emphasised that recipients should not feel any obligation or be overly cautious.

There were differences in the expectations and experiences of spousal dyads when compared with parent–child and sibling pairs. Spousal pairs expected that the donation/transplant would enhance overall quality of life as a couple, which is in accordance with previous research9 11 24 and reflected by the recent trend in donor assessment moving away from solely considering the risks to the donor and benefits to the recipient at an individual level, towards a decision-making model that combines risks and benefits for ‘interdependent donors’ (donors residing in the same household as their recipient).25 For some donors, enhanced combined quality of life was a key motivation for donating a kidney, which may explain why spousal couples in our study were focused on psychosocial impacts of living kidney donor transplantation. This finding is in accordance with previous research whereby related donors prioritised psychosocial outcomes, namely the donor–recipient relationship and family life.15 Any unmet expectations of retaining a caregiver role (for donors), improved social life and increased intimacy caused disappointment and frustration in the donor–recipient relationship. Spousal pairs also reported increased tension and arguments prior to the transplant. The donor in the spousal dyad has multiple and simultaneous roles in the relationship —caregiver, spouse and kidney donor—and we speculate that this comprised an additional stressor on the donor–recipient relationship. Further, spousal donor candidates have reported feeling more responsible for the recipient’s health postdonation, again likely due to their multiple roles.26 With the spousal donor and recipient undergoing workup for transplant together, this process became a priority in their life and led to increased tension and disruption. Previous research has found that spousal donors (when compared with genetically related donors) expect longer recovery times, more psychological problems and more pain and discomfort associated with surgery and recovery,26 possibly compounding the experienced predonation stress. However, some spousal dyads felt that going through the donation process bolstered resilience in their relationship.

Sibling pairs, when compared with spousal and parent–child dyads, seemed to be more analytical in their approach to decision making regarding donation with an acute awareness of the imbalance in the power dynamics due to the one-way gift. All sibling recipients in our study were either married and/or resided in another state to their donor; thus, unlike spousal and parent donors, the donor was less present in the recipient’s day-to-day life and did not hold a caregiving role. This finding provides a more nuanced picture and extends previous research that has found that related donors with close relationships to their recipients give less consideration to the risks of donation and their long-term health outcomes than those with more distant relationships.27

Donor–recipient pairs felt unprepared and unable to manage side effects of immunosuppression, in particular, irritability and aggression. While the adverse effects of immunosuppressants (particularly steroids) on behaviour and mood have been well established,28 29 little attention has been paid to behavioural strategies to assist patients and their families with such effects. In severe cases, recipients may be prescribed mood altering and stabilising medications (eg, antidepressants, antipsychotics and antianxiety medication)30; however, evidence for this is limited to case studies and pilot studies.31–33 Donors and recipients were also reluctant to discuss problems with their mood and sexual difficulties with their clinical team as they believed they did not have enough time to talk about issues secondary to the kidney. However, sexual problems have been reported in over 60% of renal transplant recipients34 35 and have been strongly correlated with decreased quality of life up to 5 years posttransplant.34

Studies have shown that unrealised expectations of donors and/or recipients of life posttransplantation contributed to difficulties in their relationship.10 For example, donors and/or recipients were disappointed that transplantation had not led to the desired level of improvement in physical and emotional participation in family life. While our study confirms this previous finding, we also found that in some spousal couples, functioning (eg, energy levels, libido and level of independence) improved in recipients, and surpassed that of their donor, which led to tension in the donor–recipient relationship. In spousal dyads, it is common that the illness has become completely embedded in their relationship and identities, with an enforced imbalance of power and lack of independence in relational roles due to the illness.36 Successful transplantation represents a milestone where both patient and spouse must communicate effectively and re-establish healthy boundaries and identities.

We conducted longitudinal interviews with the same dyads prior to donation/transplantation and then 1 year later and this provided access to changes in perspectives and experiences in ‘real-time,’ potentially allowing more accurate recall of events and reflections.37 This also enabled stronger rapport, and thus participants may have been more willing to disclose their perspectives more openly. We used purposive sampling to capture a relatively diverse cross-section of donor–recipient dyads.

However, there are potential study limitations. Some donors/recipients refused to participate to avoid the risk of disturbing the stability of their relationship prior to the transplant, thus transferability of these findings to those with such insecurities about their relationship remains unclear. All participants were English speaking, >18 years of age and the majority had attained a tertiary level of education. While this reflects the majority of the donor population in Australia, the transferability of these findings to other populations and contexts is uncertain. Additionally, donor–recipient dyads where the recipient is <18 years of age may have unique experiences not captured in this study. Of note, in Australia, donors must be of legal age (18 years) to be a living donor. We suggest that future research includes other donor–recipient relationships (eg, parents and non-adult children, friends, aunts, uncles) given the rise of other types of donor–recipient relationships in countries such as the USA (Organ procurement and Transplantation Network, 2018 #505).

Our study draws attention to the need for interventions and support for donors and recipients to manage mood changes of recipients, tensions arising from the gift relationship and adjustment of the identity and roles posttransplant. We recommend incorporating education on strategies to cope with emotional lability for both recipients and family members prior to transplantation. Additionally, this should be included in the postdonation psychosocial review in the first year posttransplant for both recipients and donors with referral to a psychiatrist, if indicated.38 Psychological services can assist both recipients and donors with coping with recipient’s emotional lability through acceptance strategies, normalisation, behavioural strategies, improved communication and problem-solving abilities.39 Education both pretransplant and posttransplant regarding the nature of the one-way gift relationship may help donors and recipients have a functional conceptualisation of the gift and ensure recipients are not overwhelmed by feelings of guilt.40 Facilitating access to relationship counselling in the first year posttransplant may assist spousal couples struggling with unmet expectations and adjustment in relational roles and identity posttransplantation.36

While living kidney donor guidelines41–47 recommend assessment of the donor–recipient relationship and posttransplant expectations, guidelines for transplant recipients do not explicitly address this. Guidelines recommend psychosocial follow-up of both donors and recipients, however, the donor–recipient relationship is not specifically addressed. While some transplant centres administer quality-of-life measures (eg, Short Form 36) to review the psychosocial health and well-being in postdonation follow-up care,48 49 many of these measures do not contain questions pertaining to sexual functioning and/or satisfaction and recipient mood changes, which were highly important to donors and recipients, who were hesitant to discuss these with clinicians. This calls for a need to include these domains in patient/donor-reported outcome measures.

In summary, living kidney donation can strengthen donor–recipient relationships, but for some pairs, may also trigger unexpected conflict and tension and disappointment with unfulfilled expectations. Interventions to address potential relationship difficulties are needed. In terms of posttransplant follow-up, assessment of the donor–recipient relationship requires discussion about adjustment in relational roles and relationship dynamics, changes in emotional lability and sexual functioning and donors/recipients should have access to psychological services when required. A more comprehensive focus on protecting and supporting donor–recipient relationships may contribute to overall improved psychosocial outcomes and satisfaction in living kidney donor transplantation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to all the living kidney donors and recipients who generously gave their time to share their insights and perspectives.

Footnotes

Contributors: AFR participated in the research design, data collection, data analysis and drafted the manuscript. AT participated in the research design, data analysis and drafted the manuscript. AJ, CSH and TG participated in the research design, data analysis and contributed to manuscript writing. GW, SJC, GL, PB and JCC participated in the research design and provided intellectual input on the manuscript and contributed to manuscript writing.

Funding: This project is supported by Australian Research Council (DE120101710). AFR and AT are supported by National Health and Medical Research Council (AFR: GNT1093101; AT: NHMRC1106716).

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Schena FP. Epidemiology of end-stage renal disease: International comparisons of renal replacement therapy. Kidney Int 2000;57:S39–S45. 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07407.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2. ANZDATA. 39th Annual Report. Registry Report. Adelaide, Australia: Australian and New Zealand Dialysis and Transplant Registry, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 3. UNOS. United Network for Organ Sharing. Data 2018;2018 http://www.unos.org. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Canadian Institute for Health Information. e-Statistics On Organ Transplants. Waiting Lists And Donors 2017. https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/donor_section_v0.1_en_2017.xlsx2017. [Google Scholar]

- 5. NHS Blood and Transplant.. Activity Report 2016-2017: NHS Blood and Transplant, 2018.. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shetty AA, Wertheim JA, Butt Z. Chapter 50 - Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes After Kidney Transplantation A2 - Orlando, Giuseppe In: Remuzzi G, Williams DF, eds Kidney Transplantation, Bioengineering and Regeneration: Academic Press, 2017:699-–708. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lumsdaine JA, Wray A, Power MJ, et al. Higher quality of life in living donor kidney transplantation: prospective cohort study. Transpl Int 2005;18:975–80. 10.1111/j.1432-2277.2005.00175.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clemens KK, Thiessen-Philbrook H, Parikh CR, et al. Donor Nephrectomy Outcomes Research (DONOR) Network. Psychosocial health of living kidney donors: a systematic review. Am J Transplant 2006;6:2965–77. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tong A, Chapman JR, Wong G, et al. The motivations and experiences of living kidney donors: a thematic synthesis. Am J Kidney Dis 2012;60:15–26. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.11.043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ralph AF, Butow P, Hanson CS, et al. Donor and Recipient Views on Their Relationship in Living Kidney Donation: Thematic Synthesis of Qualitative Studies. Am J Kidney Dis 2017;69:602–16. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.09.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Groot IB, Schipper K, van Dijk S, et al. Decision making around living and deceased donor kidney transplantation: a qualitative study exploring the importance of expected relationship changes. BMC Nephrol 2012;13:103 10.1186/1471-2369-13-103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Franklin PM, Crombie AK. Live related renal transplantation: psychological, social, and cultural issues. Transplantation 2003;76:1247–52. 10.1097/01.TP.0000087833.48999.3D [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Smith MD, Kappell DF, Province MA, et al. Living-related kidney donors: a multicenter study of donor education, socioeconomic adjustment, and rehabilitation. Am J Kidney Dis 1986;8:223–33. 10.1016/S0272-6386(86)80030-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Christensen AJ, Raichle K, Ehlers SL, et al. Effect of family environment and donor source on patient quality of life following renal transplantation. Health Psychol 2002;21:468–76. 10.1037/0278-6133.21.5.468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hanson C, Chapman J, Gill J, et al. Identifying outcomes that are important to living kidney donors: a nominal group technique study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;13:916–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ralph AF, Butow P, Craig JC, et al. Clinicians’ attitudes and approaches to evaluating the potential living kidney donor-recipient relationship: an interview study. Nephrology 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sajjad I, Baines LS, Salifu M, et al. The dynamics of recipient-donor relationships in living kidney transplantation. Am J Kidney Dis 2007;50:834–54. 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ummel D, Achille M, Mekkelholt J. Donors and recipients of living kidney donation: a qualitative metasummary of their experiences. J Transplant 2011;2011:1–11. 10.1155/2011/626501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shaw RM, Webb R. Multiple meanings of "gift" and its value for organ donation. Qual Health Res 2015;25:600–11. 10.1177/1049732314553853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. OPTN.. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network - Data US Department of Health and Human Services: Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network;. 2017. https://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/ (accessed 14 August 2017).

- 21. Corbin J, Strauss A. Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 2008. California: Sage Publications, Inc, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hanson CS, Chapman JR, Gill JS, et al. Identifying Outcomes that Are Important to Living Kidney Donors: A Nominal Group Technique Study. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2018;13:912–26. 10.2215/CJN.13441217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lennerling A, Forsberg A, Meyer K, et al. Motives for becoming a living kidney donor. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:1600–5. 10.1093/ndt/gfh138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Van Pilsum Rasmussen SE, Henderson ML, Kahn J, et al. Considering Tangible Benefit for Interdependent Donors: Extending a Risk-Benefit Framework in Donor Selection. Am J Transplant 2017;17:2567–71. 10.1111/ajt.14319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rodrigue JR, Widows MR, Guenther R, et al. The expectancies of living kidney donors: do they differ as a function of relational status and gender? Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006;21:1682–8. 10.1093/ndt/gfl024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hanson CS, Ralph AF, Manera KE, et al. The Lived Experience of "Being Evaluated" for Organ Donation: Focus Groups with Living Kidney Donors. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2017;12:1852–61. 10.2215/CJN.03550417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Stanbury RM, Graham EM. Systemic corticosteroid therapy--side effects and their management. Br J Ophthalmol 1998;82:704–8. 10.1136/bjo.82.6.704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carpenter WT, Gruen PH. Cortisol’s effects on human mental functioning. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1982;2:91???101–101. 10.1097/00004714-198204000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zarifian A. Symptom occurrence, symptom distress, and quality of life in renal transplant recipients. Nephrol Nurs J 2006;33:609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brown ES, Chamberlain W, Dhanani N, et al. An open-label trial of olanzapine for corticosteroid-induced mood symptoms. J Affect Disord 2004;83:277–81. 10.1016/j.jad.2004.07.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brown ES, Frol A, Bobadilla L, et al. Effect of lamotrigine on mood and cognition in patients receiving chronic exogenous corticosteroids. Psychosomatics 2003;44:204–8. 10.1176/appi.psy.44.3.204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hochhauser CJ, Lewis M, Kamen BA, et al. Steroid-induced alterations of mood and behavior in children during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Support Care Cancer 2005;13:967–74. 10.1007/s00520-005-0882-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Matas AJ, Halbert RJ, Barr ML, et al. Life satisfaction and adverse effects in renal transplant recipients: a longitudinal analysis. Clin Transplant 2002;16:113–21. 10.1034/j.1399-0012.2002.1o126.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Diemont WL, Vruggink PA, Meuleman EJ, et al. Sexual dysfunction after renal replacement therapy. Am J Kidney Dis 2000;35:845–51. 10.1016/S0272-6386(00)70254-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rolland JS. IN SICKNESS AND IN HEALTH: THE IMPACT OF ILLNESS ON COUPLES' RELATIONSHIPS. J Marital Fam Ther 1994;20:327–47. 10.1111/j.1752-0606.1994.tb00125.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Thomson R, Holland J. Hindsight, foresight and insight: The challenges of longitudinal qualitative research. Int J Soc Res Methodol 2003;6:233–44. 10.1080/1364557032000091833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Patten SB, Neutel CI. Corticosteroid-Induced Adverse Psychiatric Effects. Drug Saf 2000;22:111–22. 10.2165/00002018-200022020-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. McGrath P, Patton MA, James S. "I was never like that": Australian findings on the psychological and psychiatric sequelae of corticosteroids in haematology treatments. Support Care Cancer 2009;17:339–47. 10.1007/s00520-008-0464-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sque M, Payne SA. Gift Exchange Theory: a critique in relation to organ transplantation. J Adv Nurs 1994;19:45–51. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.1994.tb01049.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lentine KL, Kasiske BL, Levey AS, et al. KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline on the Evaluation and Care of Living Kidney Donors. Transplantation 2017;101:S7–S105. 10.1097/TP.0000000000001769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. CCDT. Enhancing living donation: A Canadian forum. Report and recommendations. Vancouver, British Columbia: The Canadian Council for Donation and Transplantation, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 43. NHMRC. Organ and tissue donation by living donors. Guidelines for ethical practice for health professionals. Canberra, Australia: Australian Government. National Health and Medical Research Council, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 44. OPTN. OPTN Policy 14: Living Donation. In: Organ procurement and Transplantation Network, ed, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 45. OPTN. OPTN Evaluation Plan. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Transplant Work Group. KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2009;9 Suppl 3:S1–S155. 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02834.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Campbell S, Pilmore H, Gracey D, et al. KHA-CARI guideline: recipient assessment for transplantation. Nephrology 2013;18:455–62. 10.1111/nep.12068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Thiel GT, Nolte C, Tsinalis D. Prospective Swiss cohort study of living-kidney donors: study protocol. BMJ Open 2011;1:e000202 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Manyalich M, Menjívar A, Yucetin L, et al. Living donor psychosocial assesment/follow-up practices in the partners' countries of the ELIPSY project. Transplant Proc 2012;44:2246–9. 10.1016/j.transproceed.2012.07.106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026629supp001.pdf (58.1KB, pdf)