Abstract

Hearing loss (≥26 dB threshold in the better ear), as a common chronic condition in humans, is increasingly gaining attention. Relevant research in China is relatively scarce, so we conduct a population-based study to investigate the prevalence of hearing loss among age groups, genders and ears in Zhejiang province, China, from September 2016 to June 2018.

Study design

Population-based cross-sectional study

Participants

A total of 3754 participants aged 18–98 years and living in Zhejiang province, China.

Outcome measures

Pure-tone audiometric thresholds were measured at frequencies of 0.125–8 kHz for each subject. All participants were asked to complete a structured questionnaire, in the presence of a healthcare official.

Results

The prevalence of speech-frequency and high-frequency hearing loss was 27.9% and 42.9%, respectively, in Zhejiang. There were significant differences in auditory thresholds at most frequencies among the age groups, genders (male vs female: 31.6%vs24.1% at speech frequency; 48.9% vs 36.8% at high frequency) and ears. In addition to the common factors affecting both types of hearing loss, a significant correlation was found between personal income and speech-frequency hearing loss (OR=0.69, 95% CI 0.52 to 0.92), and between hyperlipidaemia and high-frequency hearing loss (OR=1.45, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.07).

Conclusion

The prevalence of hearing loss was high among people living in Zhejiang, particularly males, and in the left ear. Moreover, hearing thresholds increased with age. Several lifestyle and environment factors, which can be influenced by awareness and education, were significantly associated with hearing loss.

Keywords: hearing loss, hearing thresholds, lifestyle factors, environmental factors

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to be conducted in Zhejiang, China, involving a large population, with data from a wide band of hearing frequencies.

The study investigated whether several lifestyle and environment factors, which can be influenced by awareness and education, were related to hearing loss, and this could provide some ideas for future intervention studies.

The specific values of medical-related indicators (such as systolic blood pressure, triglyceride and fasting blood-glucose) were not analysed as these data were not collected completely; hence, medical covariates were collected only based on self-reported diagnosis (as dichotomous variable, ie, yes or no).

Introduction

Hearing loss, the most common sensory deficit in humans,1 is increasingly gaining attention; WHO estimated that the prevalence of hearing loss increased from 42 million in 1985 to 360 million in 2011.2 According to a US study, more than 36 million people (16%–17% adolescents) suffered from varying degrees of hearing loss.3 Moreover, Twardella et al reported that the prevalence of hearing loss among adolescents in Germany was approximately 2.4%.4 Although the literature on hearing loss has gradually increased, these studies were either conducted in countries other than China, or the number of participants was small.5 In addition, the hearing test did not cover a wide band of frequencies.6

As a common chronic condition in humans, hearing loss affects communication and can, therefore, affect the quality of life of the individual. Furthermore, it has substantial direct and indirect societal costs.7 Moreover, in the 25-year Global Burden of Disease Study, hearing loss was the second most common non-fatal disease affecting the quality of life of Chinese individuals.8 However, the exact mechanisms of hearing loss remain unclear. Thus, there is an urgent need to study the prevalence of hearing loss and its related risk factors. Several studies have reported that hearing function is associated with age, sex, heredity and environmental factors (such as noise exposure and heavy metal exposure),9 10 but similar research in China is still relatively scarce.

Hence, in the present study, data of audiometric measurements and responses to structured questionnaires were collected to investigate the prevalence of hearing loss in adults in Zhejiang, China, while other Chinese studies were conducted elsewhere, this is the first study to be conducted in Zhejiang with a large sample size and wide band of frequencies (0.125–8 kHz). What’s more, Zhejiang is a typical representative of the eastern coastal provinces of China. It has a relatively developed economy, a large population and is one of the larger provinces in China. An epidemiological study can well describe the hearing threshold levels and hearing loss in the Chinese population, and provide some data that can be used to develop interventions for preventing early hearing loss as well as for further investigation.

Methods

Study areas and participants

A study using a multistage stratified cluster random sampling method was conducted in the Zhejiang province from September 2016 to June 2018. Five healthcare centres were selected as follows: one in Jiangshan, one in Jiaxing and three in Hangzhou (Tonglu county, Baiyang community and Sijiqing community). Complete audiometric examination data and questionnaire data of 3754 participants (1900 males and 1854 females) (18–98 years old) were analysed. The participants were divided into three age groups: the young group (18–44 years old, mean age=34.19±6.35 [mean±SD]), the middle group (45–59 years old, mean age=51.82±4.34) and the old group (60–98 years old, mean age=68.07±7.14).11

Patient and public involvement

The role of subjects (including patients) in this study was as participants. All subjects did not participate in the design, recruitment and other research work. After the completion of the study, we had called participants to elaborate on the results of this study in detail (if they indicated that they needed the results at the time of data collection).

Audiometry test

First, the otoscopic examination was performed for each participant by an otolaryngologist to detect any ear pathology potentially affecting hearing function. A total of 631 participants (14.39% [631/4385]) who had an ear disease (such as otitis externa, otitis media or cerumen impaction) or abnormal ear structure were excluded from the analysis. All pure-tone air conduction hearing thresholds were measured by trained researchers using audiometers (AT235; Interacoustics AS, Assens, Denmark) with standard headphones (TDH-39; Telephonics Corporation, Farmingdale, New York, USA). Each subject was specifically instructed to press a handheld response key as soon as they heard a tone of a frequency between 0.125 and 8 kHz (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz) over an intensity range of −10 to 110 dB in a soundproof booth with background noise of less than 20 dB(A). All facilities were calibrated before use, and similar to the study conducted by Wang et al,5 we conducted the testing by beginning at 1 kHz, continuing to higher test frequencies and then returning to 1 kHz, followed by testing lower frequencies.5 We computed the pure-tone average (PTA) at speech frequencies (0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz; speech-PTA) and high frequencies (3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz; high-PTA).12 Hearing loss was defined as speech-PTA of ≥26 dB in the better ear,9 which is consistent with the WHO definition of clinically significant hearing loss,13 and this can identify patients with bilateral hearing loss and related functional impairments.14

Covariates

All participants were asked to complete a structured questionnaire, in the presence of a healthcare official, covering demographic variables, audiometric information, lifestyle and environmental factors, as well as issues related to various risk factors and diseases. Education level was categorised as elementary school or less, middle school graduation, high school graduation and college or more. Average monthly income was classified into three categories (low: ≤¥4000; middle: ¥4001–6000 and high: ≥¥6001). On the basis of the history of cigarette smoking status, participants were categorised as follows: self-reported non-smokers (smoking less than one cigarette a day on average for less than 1 year), former smokers (cessation of smoking since the past 6 months or more) and current smokers (smoking at least one cigarette a day for more than 1 year). On the basis of the drinking history, participants were also categorised as follows: self-reported non-drinkers (less than once per week), former drinkers (abstinence for more than 6 months) and current drinkers (alcohol consumption at least once a week for more than 6 months). If a participant indicated an exposure to loud noise in the workplace at least once a week, then the participant was considered to experience occupational noise exposure. If the participant had been exposed to loud noise outside of work (eg, loud music or power tools) at least once a week, then the participant was considered to be exposed to recreational noise. To emphasise an important point, the volume of the noise is the subjective feeling of the participant, so if a participant felt that the sound was too loud to feel uncomfortable, then he/she was considered to be exposed to loud noise. Self-reported medical information, mainly about hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia, was also collected.

Statistical analysis

The study used Epidata V.3.1 (The Epidata Association, Odense, Denmark) for survey data entry and check and error correction (double entry and validation). SPSS V.19.0 for Windows was used to conduct all statistical analyses, and the results were graphed using the SigmaPlot V.12.0 software package (Systat Software International, Chicago, Illinois, USA). A Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test was performed to examine the distribution of each variable. Data were presented as proportions, mean±SD or median (IQR), according to the original data distribution. The Student’s t-test and χ2 test were used to compare differences between the groups. In addition, the differences between the left and right ear were analysed using the paired t-test, and the Bonferroni correction for pairwise comparisons. Logistic regression was used to estimate the association between hearing loss (as binary variable, which could better represent the OR of different factors in the two populations) and the variables (as categorical variables), after adjustment for age and gender. All reported probability values were two-tailed, and a p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of hearing thresholds among different populations

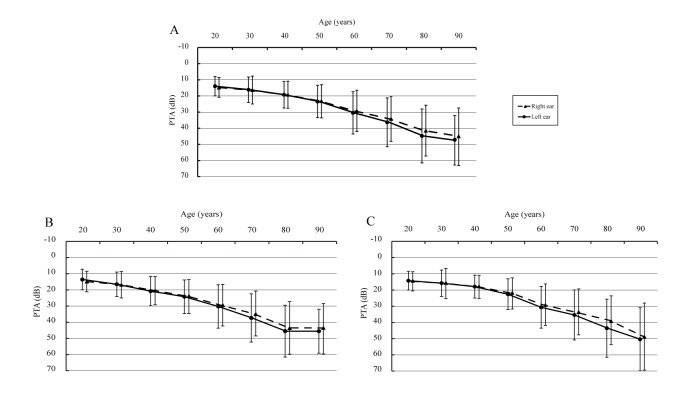

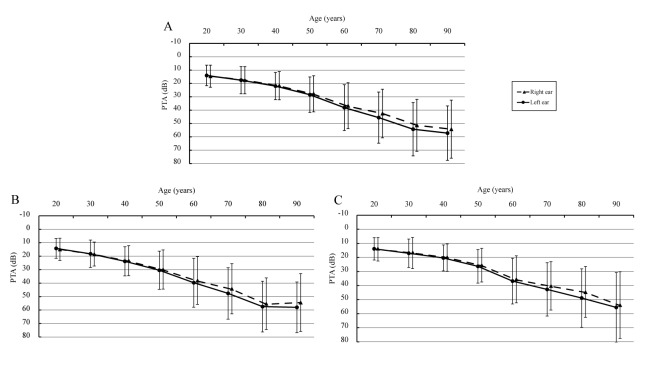

The PTA for all age groups at speech frequency and high frequency is shown in figure 1 and figure 2, respectively. There were statistically significant differences between the left and right ear (when age was over 60 years, p<0.05) with respect to PTA, both in speech frequency (33.91 dB vs 32.21 dB [total participants, age was over 60 years]) and high frequency (42.32 dB vs 40.18 dB), and the hearing loss was more prevalent in the left ear.

Figure 1.

Pure-tone average for all ages at speech frequencies (0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz) (A: total participants; B: male participants and C: female participants). The full lines indicate the hearing thresholds of left ears, and the dotted lines indicate the hearing thresholds of right ears. Bars indicate ±1 SD. ‘20 years’ old represents people aged 18–25 years old, ‘30 years’ old represents people aged 26–35 years old, ‘40 years’ old range is 36–45 years old, ‘50 years’ old range is 46–55 years old, ‘60 years’ old range is 56–65 years old, ‘70 years’ old range is 66–75 years old, ‘80 years’ old range is 76–85 years old and ‘90 years’ old range is 86–98 years old. PTA, pure-tone average.

Figure 2.

Pure-tone average for all ages at high frequencies (3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz) (A: total participants; B: male participants and C: female participants). The full lines indicate the hearing thresholds of left ears, and the dotted lines indicate the hearing thresholds of right ears. Bars indicate ±1 SD. ‘20 years’ old represents people aged 18–25 years old, ‘30 years’ old represents people aged 26–35 years old, ‘40 years’ old range is 36–45 years old, ‘50 years’ old range is 46–55 years old, ‘60 years’ old range is 56–65 years old, ‘70 years’ old range is 66–75 years old, ‘80 years’ old range is 76–85 years old and ‘90 years’ old range is 86–98 years old. PTA, pure-tone average.

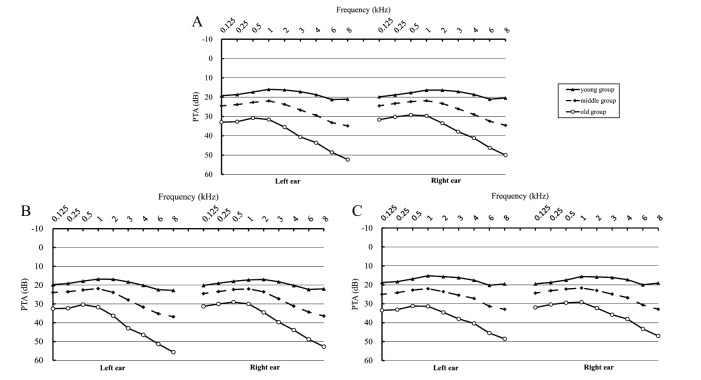

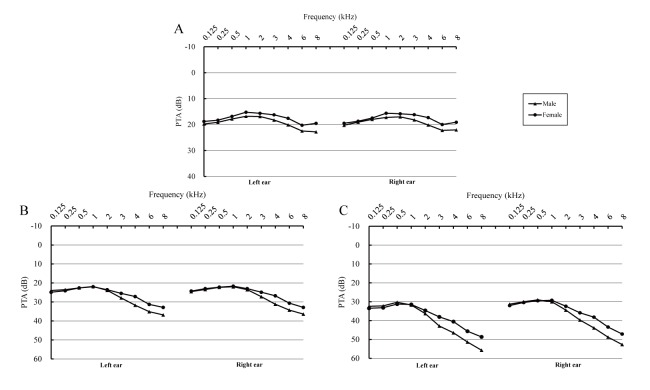

There were significant differences between the male and female participants in the young, middle and old group (especially at 3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz, p<0.05, data not shown) (figure 3). In general, compared with men, women had better hearing (male vs female: 31.6% vs 24.1% at speech frequency; 48.9% vs 36.8% at high frequency [table 1]). Meanwhile, table 1 and online supplementary table S1 (comprising original PTA data) show that significant differences in hearing loss were found among the three selected areas. The prevalence of hearing loss in Hangzhou was the highest (33.3% for speech-frequency, and 53.9% for high-frequency hearing loss). Moreover, figure 4 shows the PTA at the examined frequencies (0.125–8 kHz) among men and women in the different age groups. There were significant differences among age groups for both ears (p<0.05) at all frequencies. PTA was the highest in the old group and lowest in the young group.

Figure 3.

Pure-tone average (PTA) of different age groups (A: total participants; B: male participants and C: female participants). The left parts of the figures indicate the PTA of the left ears, and the right parts indicate the PTA of the right ears.

Table 1.

Hearing loss in different areas stratified by gender and age

| Gender | Age | Speech-frequency hearing loss≥26 dB | High-frequency hearing loss≥26 dB | ||||||

| Jiangshan, % | Jiaxing, % | Hangzhou, % | P value* | Jiangshan, % | Jiaxing, % | Hangzhou, % | P value* | ||

| Male | Young | 5.2 (13/249) | 14.2 (27/190) | 7.8 (18/230) | 0.003 | 13.3 (33/249) | 18.4 (35/190) | 18.7 (43/230) | 0.202 |

| Middle | 27.0 (65/241) | 24.6 (44/179) | 30.8 (60/195) | 0.398 | 52.3 (126/241) | 33.5 (60/179) | 67.7 (132/195) | <0.001 | |

| Old | 65.2 (131/201) | 51.2 (84/164) | 62.9 (158/251) | 0.015 | 88.6 (178/201) | 61.0 (100/164) | 88.4 (222/251) | <0.001 | |

| Female | Young | 3.9 (10/256) | 4.8 (12/248) | 5.3 (14/265) | 0.751 | 7.8 (20/256) | 12.1 (30/248) | 14.7 (39/265) | 0.046 |

| Middle | 18.8 (38/202) | 21.9 (34/155) | 26.8 (59/220) | 0.141 | 29.2 (59/202) | 34.8 (54/155) | 50.0 (110/220) | <0.001 | |

| Old | 48.0 (47/98) | 45.4 (69/152) | 63.2 (163/258) | 0.001 | 71.4 (70/98) | 53.9 (82/152) | 84.9 (219/258) | <0.001 | |

| Total | 24.4 (304/1247) | 24.8 (270/1088) | 33.3 (472/1419) | <0.001 | 39.0 (486/1247) | 33.2 (361/1088) | 53.9 (765/1419) | <0.001 | |

*Χ2 test. P<0.05 indicated a significant difference in the prevalence of hearing loss among the three selected areas stratified by gender and age.

Figure 4.

Pure-tone average (PTA) of different genders (A: young group; B: middle group and C: old group). The left parts of the figures indicate the PTA of the left ears, and the right parts indicate the PTA of the right ears.

bmjopen-2018-027152supp001.pdf (35.7KB, pdf)

The correlation between hearing loss and covariates

Of the 3754 eligible participants, a total of 1046 (27.9%) had speech-frequency hearing loss, and 1612 (42.9%) had high-frequency hearing loss. Table 2 presents the results of the comparison of the sociodemographic characteristics of the participants affected by hearing loss at speech frequency and high frequency. Participants with hearing loss group were on average 17 years older than those without hearing loss. Furthermore, there was a higher proportion of men in the hearing-loss group than in the normal-hearing group (speech frequency, 57.4% vs 48.0%, p<0.001; high frequency, 57.6% vs 45.3%, p<0.001). In addition, education, personal income, noise exposure (online supplementary table S2), smoking status and drinking status were significantly associated with both types of hearing loss (all p<0.001). As for medical covariate data, there was a significant correlation between hearing loss and presence of hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, diabetes and hypercholesterolaemia (all p<0.001, for speech-frequency and high-frequency hearing loss).

Table 2.

Characteristics of study participants

| Speech-frequency hearing loss≥26 dB | High-frequency hearing loss≥26 dB | |||||

| No | Yes | P value | No | Yes | P value | |

| Number | 2708 | 1046 | 2142 | 1612 | ||

| Age, years | 45.28±13.56 | 61.97±12.38 | <0.001 | 42.83±12.92 | 59.37±12.68 | <0.001 |

| Gender, % (males) | 48.0 | 57.4 | <0.001 | 45.3 | 57.6 | <0.001 |

| Education, % | ||||||

| ≤Elementary school | 7.2 | 23.9 | 5.5 | 20.3 | ||

| Middle school | 20.6 | 28.9 | 17.5 | 30.1 | ||

| High school | 27.4 | 26.5 | 28.0 | 26.0 | ||

| ≥College | 44.8 | 20.7 | <0.001 | 49.1 | 23.5 | <0.001 |

| Income: low/middle/high, % | 37.1/44.7/18.2 | 55.2/32.2/12.6 | <0.001 | 34.9/46.9/18.2 | 51.7/33.7/14.6 | <0.001 |

| Smoking: non/former/current, % | 79.0/4.6/16.4 | 62.2/11.8/26.0 | <0.001 | 83.1/3.5/13.4 | 62.6/10.7/26.7 | <0.001 |

| Drinking: non/former/current, % | 83.9/1.4/14.7 | 69.1/2.6/28.3 | <0.001 | 86.5/1.4/12.1 | 70.9/2.1/27.0 | <0.001 |

| Occupational noise exposure, % | 36.5 | 46.7 | <0.001 | 35.7 | 44.2 | <0.001 |

| Recreational noise exposure, % | 21.4 | 31.3 | <0.001 | 20.5 | 28.9 | <0.001 |

| Hypertension, % | 13.7 | 43.7 | <0.001 | 10.2 | 37.8 | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia, % | 4.9 | 13.6 | <0.001 | 3.3 | 12.7 | <0.001 |

| Diabetes, % | 3.2 | 12.4 | <0.001 | 1.8 | 11.0 | <0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, % | 2.0 | 5.2 | <0.001 | 1.7 | 4.4 | <0.001 |

P values based on Student’s t-test for continuous variables and χ2 test for categorical variables, and p<0.05 indicated that the independent variables were statistically different between the two groups.

bmjopen-2018-027152supp002.pdf (32.7KB, pdf)

After adjustment for age and gender, a logistic regression analysis was performed to estimate the correlation between hearing loss and independent variables (table 3). The correlation between education and speech-frequency hearing was not significant (p=0.064), although the risk of hearing loss decreased as the level of education increased. High personal income was found to have a significant negative correlation with hearing loss (OR=0.69, 95% CIs 0.52 to 0.92, p=0.025). The adjusted ORs for the comparison of current smokers and non-smokers and current drinkers and non-drinkers were 1.43 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.85) (p for trend=0.007) and 1.44 (95% CI 1.15 to 1.82) (p for trend=0.004), respectively. The results showed that both types of noise exposures were risk factors for hearing loss. As for common chronic diseases, no significant association was found between presence of hyperlipidaemia or hypercholesterolaemia and hearing loss (for hyperlipidaemia, OR=1.03, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.41, p=0.848; for hypercholesterolemia, OR=1.31, 95% CI 0.81 to 2.12, p=0.275). Hearing loss was associated with diabetes with borderline significance (OR=1.39, 95% CI 0.99 to 1.95, p=0.061), and hypertension was found to be significantly associated with hearing loss (OR=2.28, 95% CI 1.87 to 2.79, p<0.001).

Table 3.

Logistic regression analysis of all the correlations of hearing loss

| Speech-frequency hearing loss≥26 dB | High-frequency hearing loss≥26 dB | |||||

| Yes/total | ORs (95% CIs) | P trend | Yes/total | OR (95% CI) | P trend | |

| Education | ||||||

| ≤Elementary school | 250/445 | 1 (reference) | 328/445 | 1 (reference) | ||

| Middle school | 302/860 | 0.75 (0.57 to 0.98) | 486/860 | 0.93 (0.70 to 1.25) | ||

| High school | 277/1018 | 0.73 (0.55 to 0.97) | 419/1018 | 0.65 (0.48 to 0.87) | ||

| ≥College | 217/1431 | 0.66 (0.48 to 0.90) | 0.064 | 379/1431 | 0.60 (0.43 to 0.82) | <0.001 |

| Income | ||||||

| Low | 577/1581 | 1 (reference) | 834/1581 | 1 (reference) | ||

| Middle | 337/1547 | 0.80 (0.65 to 0.99) | 543/1547 | 0.82 (0.67 to 0.99) | ||

| High | 132/626 | 0.69 (0.52 to 0.92) | 0.025 | 235/626 | 0.89 (0.69 to 1.16) | 0.129 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| Non-smokers | 651/2789 | 1 (reference) | 1009/2789 | 1 (reference) | ||

| Former-smokers | 123/248 | 1.50 (1.07 to 2.11) | 173/248 | 1.85 (1.30 to 2.64) | ||

| Current-smokers | 272/717 | 1.43 (1.11 to 1.85) | 0.007 | 430/717 | 2.08 (1.63 to 2.65) | <0.001 |

| Drinking | ||||||

| Non-drinkers | 723/2995 | 1 (reference) | 1143/2995 | 1 (reference) | ||

| Former-drinkers | 27/65 | 1.64 (0.87 to 3.09) | 34/65 | 1.13 (0.60 to 2.13) | ||

| Current-drinkers | 296/694 | 1.44 (1.15 to 1.82) | 0.004 | 435/694 | 1.38 (1.10 to 1.74) | 0.022 |

| Occupational noise | ||||||

| No | 557/2277 | 1 (reference) | 899/2277 | 1 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 489/1477 | 1.35 (1.12 to 1.62) | 0.001 | 713/1477 | 1.29 (1.08 to 1.54) | 0.004 |

| Recreational noise | ||||||

| No | 719/2848 | 1 (reference) | 1134/2825 | 1 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 327/906 | 1.39 (1.13 to 1.70) | 0.002 | 461/896 | 1.39 (1.14 to 1.70) | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | ||||||

| No | 589/2926 | 1 (reference) | 1003/2926 | 1 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 457/828 | 2.28 (1.87 to 2.79) | <0.001 | 609/828 | 2.17 (1.76 to 2.68) | <0.001 |

| Hyperlipidaemia | ||||||

| No | 904/3479 | 1 (reference) | 1407/3479 | 1 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 142/275 | 1.03 (0.75 to 1.41) | 0.848 | 205/275 | 1.45 (1.02 to 2.07) | 0.039 |

| Diabetes | ||||||

| No | 916/3538 | 1 (reference) | 1435/3538 | 1 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 130/216 | 1.39 (0.99 to 1.95) | 0.061 | 177/216 | 1.82 (1.21 to 2.75) | 0.004 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | ||||||

| No | 992/3647 | 1 (reference) | 1541/3647 | 1 (reference) | ||

| Yes | 54/107 | 1.31 (0.81 to 2.12) | 0.275 | 71/107 | 1.01 (0.60 to 1.69) | 0.983 |

Analysis was adjusted for gender and age. Age was represented by categorical variables.

Moreover, smoking, drinking, occupational noise, recreational noise, hypertension and diabetes were risk factors for high-frequency hearing loss, whereas a high education level was a protective factor. In contrast with speech-frequency hearing loss, hyperlipidaemia was positively associated with hearing loss (OR=1.45, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.07, p=0.039), while no significant association was found between income and hearing loss. The effects of smoking and hypertension on hearing loss were the greatest (for smoking, OR=2.08, 95% CI 1.63 to 2.65; for hypertension, OR=2.17, 95% CI 1.76 to 2.68).

Discussion

This cross-sectional study, conducted in a large population and based on a cohort of local individuals in the Zhejiang province, provides information about the hearing threshold levels and prevalence of hearing loss among the people in Zhejiang, China. On the basis of the standard definition (speech-PTA [ie, the average of 0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz hearing threshold] of ≥26 dB in the better ear), we estimated that 27.9% of the participants had speech-frequency hearing loss, which is different from the prevalence reported in other Chinese studies, that is, those conducted by Bu et al 15 and Gong et al 6 (11.7% and 58.85%). Differences in education, economics and industrialisation level due to geographical distribution of the population surveyed may be one of the reasons. On the other hand, the study by Gong et al was conducted among older adults (≥60 years); surprisingly, the prevalence of hearing loss in the elderly in our study was calculated as 58.23%, which was very close to that of Gong. Consistent with other studies,5 16 17 women often had a lower PTA than men, at most frequencies (from 1 to 8 kHz), in both the left and right ear. Among these examined frequencies, significant differences were found between the young, middle and old groups for PTA (p<0.001), confirming that the hearing threshold increases with age, both in males and females.18 Furthermore, Sommer et al reported that a 1-year increase in age would raise the risk of hearing loss by 15%.14

Right ear dominance for PTA was identified in this study. Especially in participants older than 60 years, the right ear had better hearing ability than the left, which can be explained from the perspective of neurology. The ascending auditory projections pass through the brainstem and end in the cerebral cortex of the ipsilateral and contralateral hemispheres, with a predominant representation on the side opposite to the ear.19 In brief, the sound collected through the right ear is formed in the left hemisphere, and vice versa. Therefore, based on the anatomical characteristics of the human brain, right ear input is directly transferred to the speech perception areas in the left hemisphere, whereas stimuli to the left ear have to be transferred initially to the right hemisphere, from which it is transferred to the left hemisphere through the corpus callosum.19 Some studies have also identified the right ear dominance in certain populations,20–22 which, in turn, supports the above theoretical basis. In contrast, another study in Switzerland suggested that PTA has no significant differences between both ears.23

Hangzhou had the highest prevalence of hearing loss among the three selected areas. As a modern city with a highly developed economy, Hangzhou is filled with industrial noise, whereas the other two regions have a slightly less-developed economy, with less industrial noise. This is similar to inferences made by Wang et al.5 Meanwhile, consistent with previous studies, noise exposures (including occupational noise and recreational noise) were found to be risk factors for hearing loss,6 24 25 while education (for high-frequency hearing loss) and personal income (for speech-frequency hearing loss) were protective factors. Highly educated people have a better knowledge of health, and people with high personal income can prevent hearing loss by using low-noise devices or by avoiding high-noise workplaces.

Our results support the evidence that smoking and drinking have associations with the risk of hearing loss.26 27 Cruickshanks et al 28 estimated that current smokers were 1.69 times more likely to have hearing loss than non-smokers (95% CI 1.31 to 2.17), which is similar to the results obtained in our study (1.66-fold, 95% CI 1.24 to 2.22). Similarly, a multicentre study conducted by Fransen et al 29 reported that smoking significantly increased high-frequency hearing loss in a dose-dependent fashion.

Among the factors evaluated in the present study, hypertension had the strongest effect. The risk of hearing loss was two times higher in people with hypertension than in those without hypertension. Similar results were also found in other studies.30 31 Our study only found borderline association between diabetes and hearing loss, similar to the equivocal results from other studies.32 33 A likely explanation for these inconsistent results is that hearing loss is only weakly associated with diabetes, whose effects may be masked by other strong factors (eg, age6). Another explanation is that the number of participants with diabetes is small in this study.

The limitations of this study should be considered. First, owing to the cross-sectional study nature, a causal relationship could not be established. Second, medical covariates were collected based on self-reported diagnosis, and specific values were not analysed as these data were not collected completely. Third, similar to the study conducted by Choi and Park,34 we cannot rule out potential residual confounding by the presence of a noisy environment that were not captured by the binary variables of occupational and recreational noise (refer to exposure at the time of data collection). Fourth, the burden of hearing loss may be underestimated due to the exclusion of patients with ear diseases.

In conclusion, the differences based on age and gender in hearing threshold levels and hearing loss were identified. Older men living in modern cities filled with industrial noise should pay more attention to their hearing status. We found right ear dominance throughout all audiometric parameters. Harmful habits, such as smoking and drinking, and ambient noise (including occupational and recreational noise) are associated with hearing loss. Educating and advising individuals to maintain good general health and fitness would have benefits for hearing preservation.26 Furthermore, we found evidence that among several common chronic diseases, hypertension is the most closely related to hearing loss, which requires special attention to the hearing of patients with hypertension. Hearing loss is a multifactorial condition that is a result of multiple intrinsic and extrinsic factors acting on the ears, and further prospective studies, with a multicentre approach and wider ranges of exposure, are required to confirm the related risk factors.

We hope that our data can provide information on hearing loss for the development of national public health policies, and can help to identify some related factors for early intervention. As a developing country, society is more concerned about various fatal diseases, economy and ecology, so that our country attaches lesser importance to hearing loss than other developed countries, and we simultaneously hope to arouse the government’s attention to this condition.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

DW and HZ contributed equally.

Contributors: DW and HZ are joint first authors. DW edited the article, and oversaw data analysis and preparation of supplementary files. HZ conducted the statistical analysis and interpretation, and drafted the article. HM and LZ contributed by collecting prevalence estimates and preparation of supplementary files. LY and LX originated the study and designed the analysis, and both of them are co-investigators and approved the final version of the article.

Funding: This work was supported by the Zhejiang Key Research and Development Program (grant number 2015C03050) and the Major Science and Technology Innovation Project of Hangzhou (grant number 20152013A01).

Competing interests: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form at http://www.icmje.org/coi_disclosure.pdf and declare that LY and LX had financial support from the Zhejiang Key Research and Development Program and the Major Science and Technology Innovation Project of Hangzhou for the submitted work; no financial relationships with any organisations that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Hangzhou Normal University Ethics Committee and the study had been performed in accordance with the ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments and local government policies.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

References

- 1. Bowl MR, Simon MM, Ingham NJ, et al. A large scale hearing loss screen reveals an extensive unexplored genetic landscape for auditory dysfunction. Nat Commun 2017;8:886 10.1038/s41467-017-00595-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Olusanya BO, Neumann KJ, Saunders JE. The global burden of disabling hearing impairment: a call to action. Bull World Health Organ 2014;92:367–73. 10.2471/BLT.13.128728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Schiller JS, Lucas JW, Ward BW, et al. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: national health interview survey, 2010. Vital Health Stat 2012;10:1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Twardella D, Perez-Alvarez C, Steffens T, et al. The prevalence of audiometric notches in adolescents in Germany: the ohrkan-study. Noise Health 2013;15:412–9. 10.4103/1463-1741.121241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang J, Qian X, Chen J, et al. A cross-sectional study on the hearing threshold levels among people in qinling, qinghai, and Nanjing, China. Am J Audiol 2018;27:147–55. 10.1044/2017_AJA-16-0053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gong R, Hu X, Gong C, et al. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in China. Int J Audiol 2018;57:354–9. 10.1080/14992027.2017.1423404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dalton DS, Cruickshanks KJ, Klein BE, et al. The impact of hearing loss on quality of life in older adults. Gerontologist 2003;43:661–8. 10.1093/geront/43.5.661 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. GDaIIaPC GBD. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet 2017;390:1211–59. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Agrawal Y, Platz EA, Niparko JK. Prevalence of hearing loss and differences by demographic characteristics among US adults: data from the national health and nutrition examination survey, 1999-2004. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:1522–30. 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Helzner EP, Cauley JA, Pratt SR, et al. Race and sex differences in age-related hearing loss: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2005;53:2119–27. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00525.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Truelsen T, Begg S, Mathers C. The global burden of cerebrovascular: WHO Int, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Choi YH, Hu H, Tak S, et al. Occupational noise exposure assessment using O*NET and its application to a study of hearing loss in the US general population. Occup Environ Med 2012;69:176–83. 10.1136/oem.2011.064758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vaughan G. Deafness and hearing loss. 2018. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss

- 14. Sommer J, Brennan-Jones CG, Eikelboom RH, et al. A population-based study of the association between dysglycaemia and hearing loss in middle age. Diabet Med 2017;34:683–90. 10.1111/dme.13320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bu X, Liu C, Xing G, et al. WHO ear and hearing disorders survey in four provinces in China. Audiol Med 2011;9:141–6. 10.3109/1651386X.2011.631285 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brant LJ, Gordon-Salant S, Pearson JD, et al. Risk factors related to age-associated hearing loss in the speech frequencies. J Am Acad Audiol 1996;7:152–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim JS. Prevalence and factors associated with hearing loss and hearing aid use in korean elders. Iran J Public Health 2015;44:308–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu H, Luo H, Yang T, et al. Association of leukocyte telomere length and the risk of age-related hearing impairment in Chinese Hans. Sci Rep 2017;7:10106 10.1038/s41598-017-10680-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Westerhausen R, Hugdahl K. The corpus callosum in dichotic listening studies of hemispheric asymmetry: a review of clinical and experimental evidence. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2008;32:1044–54. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Budenz CL, Cosetti MK, Coelho DH, et al. The effects of cochlear implantation on speech perception in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:446–53. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Keefe DH, Gorga MP, Jesteadt W, et al. Ear asymmetries in middle-ear, cochlear, and brainstem responses in human infants. J Acoust Soc Am 2008;123:1504–12. 10.1121/1.2832615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Sharpe RA, Camposeo EL, Muzaffar WK, et al. Effects of age and implanted ear on speech recognition in adults with unilateral cochlear implants. Audiol Neurootol 2016;21:223–30. 10.1159/000446390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wettstein VG, Probst R. Right ear advantage of speech audiometry in single-sided deafness. Otol Neurotol 2018;39:417–21. 10.1097/MAO.0000000000001756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Degeest S, Clays E, Corthals P, et al. Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Leisure Noise-Induced Hearing Damage in Flemish Young Adults. Noise Health 2017;19:10–19. 10.4103/1463-1741.199241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Smalt CJ, Lacirignola J, Davis SK, et al. Noise dosimetry for tactical environments. Hear Res 2017;349:42–54. 10.1016/j.heares.2016.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin YY, Wu LW, Kao TW, et al. Secondhand smoke is associated with hearing threshold shifts in obese adults. Sci Rep 2016;6:33071 10.1038/srep33071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Shimokata H. Why are individual differences in the hearing ability so great in the elderly? Relationship of hearing with systemic aging.:Relationship of hearing with systemic aging. Audiology 2010;51:177–84. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cruickshanks KJ, Klein R, Klein BE, et al. Cigarette smoking and hearing loss: the epidemiology of hearing loss study. JAMA 1998;279:1715–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fransen E, Topsakal V, Hendrickx JJ, et al. Occupational noise, smoking, and a high body mass index are risk factors for age-related hearing impairment and moderate alcohol consumption is protective: a European population-based multicenter study. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol 2008;9:264–76. 10.1007/s10162-008-0123-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fang Q, Wang Z, Zhan Y, et al. Hearing loss is associated with increased CHD risk and unfavorable CHD-related biomarkers in the Dongfeng-Tongji cohort. Atherosclerosis 2018;271:70–6. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2018.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Üçler R, Turan M, Garça F, et al. The association of obesity with hearing thresholds in women aged 18-40 years. Endocrine 2016;52:46–53. 10.1007/s12020-015-0755-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Jung DJ, Lee JH, Kim T, et al. Association between hearing impairment and albuminuria with or without diabetes mellitus. Clin Exp Otorhinolaryngol 2017;10:221–7. 10.21053/ceo.2016.00787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Passamonti SM, Di Berardino F, Bucciarelli P, et al. Risk factors for idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss and their association with clinical outcome. Thromb Res 2015;135:508–12. 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Choi YH, Park SK. Environmental exposures to lead, mercury, and cadmium and hearing loss in adults and adolescents: KNHANES 2010-2012. Environ Health Perspect 2017;125:067003 10.1289/EHP565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-027152supp001.pdf (35.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-027152supp002.pdf (32.7KB, pdf)