INTRODUCTION

The global burden of oral disease and the negative social and economic effect associated with it, are a growing problem worldwide.1

The widespread use of water fluoridation and fluoride-containing oral products produced significant decreases in the prevalence and severity of dental caries over the last 70 years.2,3 However, the benefits of these prevention interventions have not materialized in all segments of society in most countries. Free sugars and processed carbohydrates as a component of diet have increased in many countries, both developed and developing alike. As Thompson and colleagues4 have shown, lower income groups are particularly vulnerable to high dietary sugar intake. The result has been a disparity in caries experience across socioeconomic groups. In the United States and other high-income countries, untreated dental decay in children is strongly patterned by income and ethnicity, mainly owing to cost and limited availability and/ or access to services.5 In lower income groups, much of the caries goes untreated, resulting in severe disease levels that leads to pain, expense, and a decreased quality of life for the affected children and their families.6

Even when dental services are accessible, traditional restorative treatment can be difficult to deliver to young children with severe disease and those with special management considerations.7 To address this difficulty, advanced forms of behavior management like sedation and/or general anesthesia are often used, which increase the cost and the risk for the patient and the dentist.8 Elderly patients often face similar challenges, because increasing rates of untreated decay can severely affect their quality of life, and the difficulties of receiving dental care are accentuated by limitations with mobility and other comorbidities.9

When it comes to prevention, epidemiologic studies indicate that when the bacterial challenge is high or the salivary components are lacking, natural remineralization or that aided by fluoride products is insufficient to prevent or arrest the caries process. Thus, there is an urgent need to find ways to beneficially modify the biofilm and to enhance the remineralization process to decrease caries experience and attain improved outcomes of oral health.10 This situation calls for a paradigm change in caries prevention and management. Specifically, we need more effective, affordable, accessible, and safe treatments that are easy to implement in different settings, and are available to the most vulnerable populations.11

Silver diamine fluoride (SDF), a clear liquid that combines the antibacterial effects of silver and the remineralizing effects of fluoride, is a promising therapeutic agent for managing caries lesions in young children and those with special care needs that has only recently become available in the United States. Multiple in vitro studies document its effectiveness in reducing specific cariogenic bacteria12 and its remineralizing potential on enamel and dentin.13,14 Its in vivo mechanism(s) of action are a subject of ongoing research. What is currently understood is that the fluoride component strengthens the tooth structure under attack by the acid byproducts of bacterial metabolism,15 decreasing its solubility, but SDF may also interfere with the biofilm, killing bacteria that cause the local environmental imbalance that demineralizes dental tissues.16 Thus, SDF becomes one of the tools available to address caries by modifying the bacterial actions on the tissue while enhancing remineralization.

Numerous systematic reviews substantiate SDF’s efficacy for caries arrest in primary teeth, and arrest and prevention of new root caries lesions. It meets the US Institute of Medicine’s 6 quality aims of being7:

Safe—clinical trials that have used it in more than 3800 individuals have reported no serious adverse events7,17;

Effective—arrests approximately 80% of treated lesions18;

Efficient—can be applied by health professionals in different health and community settings with minimal preparation in less than 1 minute;

Timely—its ease of application can allow its use as an intervention agent as soon as the problem is diagnosed;

Patient centered—is minimally invasive and painless, meeting the immediate needs of a child or adult in 1 treatment session; and

Equitable—its application is equally effective and affordable; with the medicament costing less than $1 per application, it is a viable treatment for lower income groups.

The only apparent drawback is that as the caries lesions become arrested, the precipitation of silver byproducts in the dental tissues stain the lesions black, which can be a deterrent for its use in visible areas (Figs. 1–4).

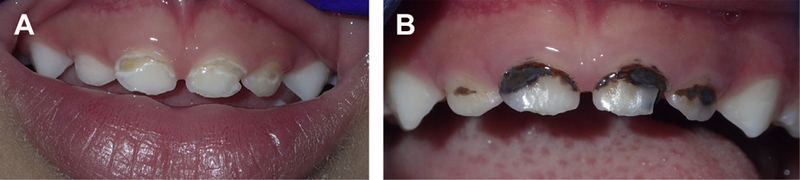

Fig. 1.

(A) Enamel and dentin caries lesions in primary anterior teeth. (B) Same lesions showing staining after SDF treatment.

Fig. 4.

Staining on non-cavitated and partially-cavitated enamel lesions.

Systematic syntheses of clinical trials’ findings constitute the highest level of evidence and are essential to inform evidence-based guidelines and set the standard of care in all settings of dental practice. This article presents and discusses the findings of systematic reviews and metaanalysis of SDF as a treatment for caries arrest and prevention.

BACKGROUND

Silver compounds, especially silver nitrate, have been used in medicine to control infections for more than a century.19 In dentistry, reports of use of silver nitrate are well-documented for caries inhibition20 and, before the twentieth century, silver nitrate was firmly entrenched in the profession as a remedy for “hypersensitivity of dentin, erosion and pyorrhea, and as a sterilizing agent and caries inhibitor in deciduous as well as in permanent teeth.”21 Howe’s solution (ammoniacal silver nitrate, 1917), was reported to disinfect caries lesions22 and continued to be used for nearly one-half of a century as a sterilizing and disclosing agent for bacterial invasion of dentin23,24 to avoid direct pulp exposures, to detect incipient lesions, and to disclose leftover carious dentin.25

The relationship of fluorides and caries prevention had been well-established through epidemiologic observations, chemical studies, animal experiments, and clinical trials beginning in the early decades of the twentieth century. It is now well-known that, when fluoride combines with enamel or dentin, it greatly reduces their solubility in acid, promotes remineralization, and results in a reduction of caries.26

The use of ammoniacal silver fluoride for the arrest of dental caries was pioneered by Drs Nishino and Yamaga in Japan,27 who developed it to combine the actions of F— and Ag+ and led to the approval of the first SDF product, Saforide (Bee Brand Medico Dental Co, Ltd, Osaka, Japan) in 1970.28 Each milliliter of product contains 380 mg (38 w/v%) of Ag(NH3)2F. They described its effects for prevention and arrest of dental caries in children, prevention of secondary caries after restorations, and desensitization of hypersensitive dentin. They reported that it penetrated 20 μm into sound enamel. In dentin, reported penetration of F‒ was up to 50 to 100 μm and Ag+ went deeper than that, getting close to the pulp chamber.28 They warned that because the agent stains the decalcified soft dentin black, its application should be confined to posterior teeth and gave specific instructions for its application.

Other similar products then became commercially available in other regions, like Silver Fluoride 40% in Australia (SCreighton Pharmaceuticals, Sydney),29 Argentina (SDF 38% several brands), and Brazil (several SDF concentrations and brands).30

Since 2002,31 the search for innovative approaches to address the caries pandemic resulted in the publication of many clinical trials of SDF efficacy (through comparison with no treatment), and its comparative effectiveness with other chemopreventive agents (eg, fluoride varnish [FV]), as well as other treatment interventions (eg, atraumatic restorative treatment [ART]). The results of these studies established the effectiveness of SDF as a caries arresting agent. In 2014, the US Food and Drug Administration approved SDF as a device for dentin desensitization in adults and, in 2015, the first commercial product became available in the United States: Advantage Arrest. Advantage Arrest (Elevate Oral Care, LLC, West Palm Beach, FL) is a 38% SDF solution (Box 1).

Box 1. Manufacturer production description of silver-diamine fluoride 38%.

| Silver-Diamine Fluoride 38% Desensitizing ingredient32 |

Professional tooth desensitizer Aqueous silver diamine fluoride, 38.3%–43.2% w/v |

| Presentation32,33 | Light-sensitive liquid with ammonia odor and blue coloring 8 mL dropper-vials contain: approximately 250 drops; enough to treat 125 sites; a site is defined as up to 5 teeth; the unit-dose ampule contains 0.1 mL per ampule |

| Specific gravity34 | 1.25 |

| Composition34 | 24%–27% silver 7.5%–11.0% ammonia 5%–6% fluoride (approximately 44,800 ppm) <1% blue coloring ≤62.5% deionized water |

| Data from Refs.32–34 |

Manufacturer’s instructions are limited to its approved use as a dentin desensitizer in adults. However, results from clinical trials conducted in many different countries on more than 3900 children have led investigators to develop recommendations for its use as a caries arrest medicament in children.7,35

In 2017, the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry published a Guideline for the “Use of Silver Diamine Fluoride for Dental Caries Management in Children and Adolescents, Including Those with Special Health Care Needs.”36 This document encouraged the off-label adoption of this therapy for caries arrest, much as FV is used for caries prevention. In November 2016,37 the US Food and Drug Administration granted SDF a breakthrough therapy status, which facilitates clinical trials of SDF for caries arrest to be carried out in the United States. Studies are currently underway that may result in the change of its labeling in the near future.38

Since 2009,39 systematic reviews report on SDF’s ability to arrest or prevent caries lesions. For this article, we reviewed systematic reviews reported in English and published or accepted for publication through March 2018. We identified 6 systematic reviews that met most of the PRISMA guidelines.40 Their details can be found in Table 1. The outcomes reported in these reviews include efficacy (ability to arrest or prevent\ caries lesions) and comparative effectiveness (eg, equivalence or superiority when compared with other modalities such as ART and FV). Included reviews report on the primary and permanent dentitions of children and the permanent teeth on elderly populations. We consider each endpoint separately herein.

Table 1.

Systematic reviews/metaanalysis on silver diamine fluoride trials

| Author, Year | Outcome Measures | Studies Included and Max Follow-up Time Analyzeda | Dentitions Included/ Frequency of SDF Applicationb | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosenblatt et al,39 2009 | Caries arrest and caries prevention | Systematic review Chu,31 2002 30 Llodra,46 2005 |

30 mo 36 mo |

Primary max ant/q 12 mo Primary post teeth and First permanent molars/q 6 mo |

SDF prevented fraction: caries arrest 5 96.1%; caries prevention 5 70.3% |

| Horst et al,35 2016 | Caries arrest and/or prevention | Systematic review Chu,31 2002 30 Llodra,46 2005 |

30 mo 36 mo |

Primary max ant/q 12 mo Primary post teeth and First permanent molars/q 6 mo |

Descriptive for each of the studies |

| Zhi,45 2012 | 24 mo | Primary ant and post/q 6 and q 12 mo | |||

| Yee,64 2009 | 24 mo | Primary ant and post/1 app only | |||

| Liu,48 2012 | 24 mo | Permanent first molars/q 12 mo | |||

| Monse,50 2012 | 18 mo | Permanent first molars/1 app only | |||

| Dos Santos,65 2014 | 12 mo | Primary ant and post/1 app only | |||

| Zhang,66 2013 | 24 mo | Root caries on elders/q 12 and q 24 mo | |||

| Tan,67 2010 | 36 mo | Root caries on elders/q 12 mo | |||

| Gao et al,18 2016 | Caries arrest in children | Metaanalysis included only SDF 38% at different time periods | Caries arrest rate of SDF 38% was | ||

| Chu,31 2002 | 30 mo | Primary max ant/q 12 mo | |||

| Llodra,46 2005 | 36 mo | Primary post teeth and First permanent molars/q 6 mo | 86% at 6 mo 81% at 12 mo | ||

| Zhi,45 2012 | 24 mo | Primary ant and post/q 6 and q 12 mo | 78% at 18 mo 71% at 30 mo or > | ||

| Yee,64 2009 | 24 mo | Primary ant and post/1 app only | |||

| Wang, 1964 Chinese | 18 mo | Primary ant and post/q 3 and q 4 mo | Overall arrest was 81% (95% CI, 68%–89%; P<.001) | ||

| Yang, 2002 Chinese | 6 mo | Primary teeth/1 app only | |||

| Ye, 1994 Chinese | 12 mo | Primary teeth/1 app only | |||

| Fukumoto, 1997 Japanese | 48 mo | Primary teeth/1app only | |||

| Chibinski et al,51 2017 | Control of caries progression in children after 12 mo follow-up | Metaanalysis included only studies with “low risk” of bias Evaluated at 12 mo results only (regardless of follow-up time) SDF vs control materials | Caries arrest was 89% higher than using active materials/placebo at 12 mo | ||

| Duangthip,43 2016 | 12 mo | Primary ant and post/1 app/year or 3 app weekly at baseline | |||

| Zhi,45 2012 | 24 mo | Primary ant and post/q 6 and q 12 mo | |||

| NSP or SDF vs placebo Dos Santos,65 2014 | Primary ant and post/1 app only | ||||

| NSP | 12 mo | ||||

| Seberol and Okte,68 2013 | Primary max ants only/1 app only | ||||

| SDF (unpublished) | 12 mo | ||||

| Oliveira et al,49 2018 | Prevention of new caries lesions in primary teeth | Metaanalysis included comparable studies evaluated at _24 mo SDF vs placebo | SDF applications reduce | ||

| Chu,31 2002 | 30 mo | Primary max ant/q 12 mo | development of dentin lesions in treated and untreated primary teeth | ||

| Llodra,46 2005 | 36 mo | Primary post teeth and First permanent molars/q 6 mo | PF: 77.5%; 95% CI, 67.8%–87.2% | ||

| SDF vs GIC Dos Santos,55 2012 | 12 mo | Primary ant and post/1 app only | |||

| Hendre et al,53 2017 | Caries arrest and prevention in older adults | Systematic review only | Prevention: | ||

| Tan,67 2010 n = 203 | 36 mo | Root caries on elders/q 12 mo | PF of SDF vs placebo 5 71% in 36- mo study | ||

| Zhang,66 2013 n = 227 | 24 mo | Root caries on elders/q 12 and q 24 mo | 21% in a 24-mo study | ||

| Li,58 2016 n =67 | 30 mo | Root caries on elders/q 12 and q 24 mo | Arrest: PF of SDF vs placebo 5 725% greater in 24-mo study 100% greater in 30 mo study | ||

Abbreviations: ant, anterior; app, reapplication; CI, confidence interval; NSP, nano-silver particles; PF, preventive fraction; post, posterior; SDF, silver-diamine fluoride.

Number of subjects in published studies for SDF in children are included in Table 2 n 5 listed in this table corresponds with the number of subjects in the study quoted not included in Table 2.

q × mos refers to frequency of reapplication in months.

CURRENT EVIDENCE ON THE EFFICACY OF SILVER DIAMINE FLUORIDE FOR CARIES ARREST AND PREVENTION

In this section, we evaluate the results for SDF’s efficacy for caries arrest as reported by the systematic reviews and metaanalysis included in Table 1. These systematic reviews used different perspectives to evaluate 17 prospective, parallel design, randomized, controlled clinical trials with a clearly defined outcome. As a result, and apparent from Table 1, many of the systematic reviews included refer to the same body of clinical trials, just updating results as additional studies became available. Details of each of the included clinical trials conducted on children and published in English are included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Description and clinical details of randomized control trials on children

| Chu et al,31 2002 | Yee et al,64 2009 | Zhi et al,45 2012 | Dos Santos et al,55 2012 | Duangthip et al,442018 | Fung et al,42 2018 | Llodra et al,462005 | Braga et al,47 2009 | Liu et al,482012 | Monse et al,502012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | China | Nepal | China | Brazil | Hong Kong | China | Cuba | Brazil | China | Philippines |

| Dentition studied | Primary anterior only | Primary | Primary anterior And posterior | Primary | Primary anterior And posterior | Primary anterior and posterior | Primary cuspids, Molars and permanent first molars | Permanent first molars | Permanent First molars | Permanent first molars |

| Caries effect studied | Arrest | Arrest | Arrest | Arrest | Arrest | Arrest | Arrest and prevention | Arrest | Prevention | Prevention |

| Groups compared | 1. SDF (38%) 1 × /y with caries removal | 1. SDF (38%) 1 × followed by tannic acid as reducing agent | 1. SDF (38%) 1 × /y | 1. SDF(30%) 1 × | 1. SDF (30%) 1 × /y | 1. SDF (38%) 2 × /y | 1. SDF (38%) 2 × /y | 1. SDF (10%) 3 × at 1-wkinterval | 1. SDF (38%) 1 × /y | 1. SDF 38%) 1 × on Sound and cavitated molars |

| 2. SDF (38%) 1_ × /y without caries removal | 2. SDF (38%) 1 × alone | 2. SDF (38%) 2 × /y | 2. ITR (Fuji IX) w/conditioner 1 × | 2. SDF (30%) 1_/week for 3 wk at baseline | 2. SDF (38%) 1 × /y | 2. No treatment | 2. GI (Fuji III) sealant 1 × | 2. Resin sealant | 2. ART (highviscosity Ketac molar) on sound And cavitated molars | |

| 3. FV 5% 4 × y with caries removal | 3. SDF (12%) 1 × alone | 3. GI (Fuji VII) w/conditioner 1 × /y | 3. FV (5% 1 × /wk for 3 wk at baseline | 3. SDF (12%) 2 × /y | 3. Cross Toothbrushing Noncavitated Caries lesions On each child 1 molar was assigned to each group | 3. 5% NaF varnish 2 × y | 3. NT Some Schools had Tooth brushing programs And some did not | |||

| 4. FV 5% 4 × y without caries removal | 4. No treatment | 4. SDF (12%) 1 × /y | 4. Yearly placebo Deep fissures or noncavitated early lesions Each child got same treatment in all molars | |||||||

| 5. Water control | ||||||||||

| Main findings | 1. SDF was more Effective than FV or control (65% arrested lesions for SDF groups vs 41% for FV groups vs 34% for control) | 1. SDF was more effective than controls (31% arrested lesions for SDF groups vs 22% for SDF 12% vs 15% for control) | 1. SDF and GI are equally effective (91% Arrested lesions for SDF 2× _/y vs 79% SDF 1× /y, vs82% GI 1× /y) | 1. SDF was More effective than ITR (67% arrested lesions in SDF group vs 39% in control) | 1. SDF 1 × /y was more effective than SDF or FV 3 weekly applications at baseline (arrest of cavitated lesions: 48% SDF 1x/y vs 33% in group 2% and 34% with FV; for arrest of moderate lesions the 3 protocols were equally effective: 45% SDF 1 × /y vs44% in group 2% and 51% with FV)c | 1. SDF 38% 2 × /y was more effective than SDF 38% 1 × /y, SDF 12% 2_/y or 1 × /y (77% arrested lesions vs 67%, 59% and 55%, respectively) | 1. SDF 2 × /y was more effective for caries arrest Than controls (85% arrested lesions with SDF vs 62% in control) | 1. SDF was more effective Than toothbrushing or GI at 3 and 6 mo | 1. The 3 active Treatments are effective in caries prevention (progression of caries into dentin was 2.2% for SDF, 1.6% for sealant, 2.4% for FV vs 4.6% for control) | 1. ART sealants were more Effective than a single Application of SDF (caries Increment in the brushing group was: 0.08 for NT; 0.09 for SDF; 0.01 For sealants. In nonbrushing group: 0.17 for NT; 0.12 for SDF; 0.06 for sealants) |

| 2. Caries removal had no effect | 2. Tannic acid had no effect | 2. Increasing frequency of SDF (2 × /y) increases caries arrest | 2. SDF was Effective for caries reduction in both Primary and permanent Teeth (0.29 surfaces with new caries in SDF group vs 1.43 in control in primary teeth and 0.37 vs 1.06 in permanent molars) | 2. All equally effective in controlling initial (noncavitated) occlusal caries at 30 mo | 2. Control group Developed more Dentin caries than treatment groups | 2. Caries increment was lower in toothbrushing group | ||||

| 3. Control group developed more new caries than treatment groups | 3. Arrest benefit decreases over time | 3. Anterior teeth and buccal/ lingual surfaces are more likely to become arrested | ||||||||

| Additional findings | 1. Arrested lesions Looked black Without changing Parental satisfaction (93% of Parents did not mention a difference) | 1. Single SDF Application prevented one-half of arrested surfaces at 6 mo from reverting to active lesions Again over 24 mo | 1. GI provides a more esthetic outcome | 1. 43% of GIC fillings were lost a 6 mo and dentin was soft. | 1. Lesions in anterior teeth, buccal/ Lingual surfaces and Lesions with no plaque had a Higher chance to become arrested | 1. Lesion site was significant with lower anteriors having the Highest rates of arrest Followed by upper anteriors, lower posterior, and upper posterior | 1. SDF showed more Efficacy to arrest decay in deciduous teeth than permanent teeth | 1. Retention rates for GI sealants were 32% at 6 mo and 9% at 30 mo | 1. Teeth with Early caries at baseline were More likely to develop dentin caries after 24 mo | 1. Retention rate for sealants was 58% after 18 mo |

| 2. No complaints From parents or children to SDF | 2. Only 3.5% Retention of GI after 24 mo still Provides caries arrest | 2. Higher rate of failure when GIC Involved multiple surfaces. | 2. Lesions with visible plaque and large lesions had lower chance of becoming arrested | 2. GI sealants were more Time consuming that SDF application | 2. 46% sealant retention | |||||

| 3. 45% of parents in all groups were Satisfied with appearance | ||||||||||

| SDF Clinical Application Protocol | aTwo treated groups had caries removal and 2 did not | aNo caries removal | aMinor excavation | aNo caries removal | a No caries removal | a Does not specify SDF amount used, time of exposure, or kind of isolation | aMinor decay excavation on permanent molars only | a No caries removal | a Does not specify SDF amount used, time of exposure, or whether it was rinsed or not | a Does not specify SDF amount used, SDF rubbed for 1 min followed by tannic acid, dried with cotton pellet, and coveredwith petroleum jelly |

| aDoes not specify SDF amount used or time of exposure | aOne drop of SDF applied for 2 min to carious surfaces and dried with cotton pellet | aDoes not specify SDF amount used or time of exposure | aDoes not specify SDF amount used | aDoes not specify SDF amount used or kind of isolation | a Does not specify SDF amount used | aDoes not specify SDF amount used | a Cotton roll isolation | a Cotton roll isolation | ||

| aNo food or drink for 1 h after | aNo food or drink for 30 min after | aCotton roll isolation, petroleum jelly on gingiva, SDF applied for 3 min and rinse and spit | a SDF rubbed for 10 s _ No food or drink for 30 min | a Cotton roll isolation, SDF applied for 3 min and wash for 30 s | a Cotton roll isolation and petroleum jelly on gingiva, SDF applied for 3 min, and wash for 30 s | a No food or drink for 30 min | ||||

| aNo food or drink for 1 h | a No food or drink for 1 h | |||||||||

| Adverse effects | None | None | None | None | None | None | 0.1% Gingival irritation | None | None | None |

| Duration of study (mo) | 30 | 24 | 24 | 12 | 30 | 30 | 36 | 30 | 24 | 18 |

| Baseline caries | 3.92 dmfs (active Anterior lesions) | 6.8 dmfs (active lesions) | 5.1 dmft (3 random teeth/child) | 3.8 dmft | 4.4 dmft 6.7 dmfs | 3.84 dmft 5.15 dmfs | 3.2 dmft | Noncavitated Molar occlusal | No cavitated lesions | At least 1 sound permanent molar |

| Background F exposure | Low F exposure reported use of F toothpaste | Low F exposure Provided F toothpaste | Low F exposure low access to F toothpaste | Low F Exposure access to F toothpaste | F water F toothpaste | Low F exposure F toothpaste | Low F exposure 1 0.2% NaF rinse in school every other week | Low F Exposure Provided F toothpaste | Low F Exposure Provided F toothpaste | Low F exposure Provided F toothpaste |

| No. of subjects at baseline | 375 | 976 | 212 | 91 | 371b | 888 | 425 | 22 children, 66 molars | 501 | 1016 |

| No. of subjects at endpoint | 308 | 634 | 181 | ? | 309b | 799 | 373 | ? | 485 | 704 |

| Examinations after baseline | × 6 mo | 1, 12, and 24 mo | × 6 mo | × 6 mo | × 6 mo | × 6 mo | × 6 mo | 3, 6, 12, 18 and 30 mo plus radiographs at 6, 12 and 30 mo | × 6 mo | 18 mo |

Abbreviations: ART, atraumatic restorative treatment; dmfs, decayed/missing/filled surface; dmft, decayed/missing/filled teeth; FV, fluoride varnish; GI, glass ionomer; GIC, glass ionomer cements; NT, no treatment; SDF, silver diamine fluoride.

Low F exposure = low F in the water, no other professionally applied fluorides or fluoride supplements.

Number of subjects at baseline and endpoint reported on 30-mo results is different that numbers reported on 18-mo results.

Cavitated lesions were International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) 5 or 6; moderate lesions had no visible dentine and were ICDAS 3 or 4.

Modified from Crystal YO, Niederman R. Silver diamine fluoride treatment considerations in children’s caries management. Pediatr Dent 2016;38(7):467–8; with permission.

Taken together, the underlying clinical trials and systematic reviews indicate that SDF arrests caries in primary teeth and root caries in elders. and may prevent formation of new caries. Details on each of the outcomes measured on different dentitions and age groups are described in the following sections.

Caries Arrest on Primary Teeth in Children

All studies reach a similar conclusion supporting SDF’s efficacy in arresting decay in primary teeth compared with no treatment and several other treatment modalities. Based on the Gao 2016 metaanalysis,18 the proportion of caries arrest on primary teeth treated with different application protocols (1 application, annual, and biannual), and followed from 6 to 30 months, was 81% (95% confidence interval, 68%–89% p<.001). Chibinski and colleagues (2017)51 reported that the caries arrest at 12 months promoted by SDF was 66% higher (41%–91%) than by other active material, but it was 154% higher (67%–85%) than by no treatment. Chibinski and associated51 also reported a risk ratio of 1.66 (95% confidence interval, 1.41–1.96) when comparing SDF with active treatments, and a risk ratio of 2.54 (95% confidence interval, 1.67–3.85) when comparing SDF with no treatment.

It is apparent that the range of caries arrest is very wide, indicating that a proportion (that varies depending on the study) of the lesions receiving treatment will not become arrested. Several trials have stressed that in their results, anterior teeth have much higher rates of arrest than posterior teeth41–45 As an example, one of the trials not included in the reviews, because it just published its 30-month results,42 reports caries arrest by type of primary tooth using SDF 38% semiannually (Box 2).

Box 2. Caries arrest by type of primary tooth using SDF 38% semiannually.

| Overall arrest at 30 mo all teeth | 75.0% |

| Lower anterior teeth | 91.7% |

| Upper anterior teeth | 85.6% |

| Lower posterior teeth | 62.4% |

| Upper posterior teeth | 57.0% |

| Data from Fung MHT, Duangthip D, Wong MCM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of 12% and 38% silver diamine fluoride treatment. J Dent Res 2018;97(2):171–8. | |

In addition, this study, as have others,44,45 found that lesions with visible plaque and large lesions had a lesser likelihood of arrest. The difference in arrest rates in children receiving applications twice per year versus once per year was small between 24 and 30 months in all teeth, but among children who received annual application, those with visible plaque had a lesser likelihood of having their lesions arrested. Fung and colleagues42 conclude that, for children with poor oral hygiene, caries arrest rate can be increased by increasing the frequency of application from annually to semiannually.

Caries Arrest on Permanent Teeth in Children

The Rosenblatt review is the only one that addresses caries arrest in permanent teeth, and it is based on only 1 trial (Llodra and colleagues [2006]46). They calculate a preventive fraction of 100% and number needed to treat of 1, basing their calculations on the mean number of arrested lesions was 0.1 in the SDF group and 0.2 in the control group. Llodra and associates (2006)46 report that around 77% of treated caries that was active at baseline became inactive during the study, both in primary and in first permanent molars. Another small trial (on 22 children) studied caries arrest in permanent molars47 (see Table 2) and found that SDF was more effective than tooth-brushing or glass ionomer at 3 and 6 months, but they were all equally effective in controlling noncavitated lesions at 30 months No other systematic reviews were able to reach conclusions on caries arrest on permanent teeth in children owing to lack of solid evidence.

Caries Prevention in Children

The review undertaken by Rosenblatt and associates39 evaluated SDF’s potential for prevention using data from 2 trials. The trial from Llodra and colleagues (2006)46 included primary and permanent molars and found that new caries lesion development (as a marker of caries prevention) in permanent teeth was significantly lower in the SDF group (0.4 new lesions) that in the water control group (1.1 new lesions) over 36 months. In primary teeth, the SDF groups averaged 0.3 new lesions versus 1.4 in the water control group. A trial conducted by Chu and associates (2002)31 using only maxillary anterior teeth in preschool children found the mean number of new lesions over a period of 30 months in the SDF group was 0.47 versus 0.7 new lesions per year with 4 yearly applications of FV, versus 1.58 new lesions in the water control group. The review concludes that the preventive fraction for SDF was 70.3% (>60% on permanent teeth and >70% on primary teeth). Only 2 other clinical trials have studied caries preventive effect of SDF on permanent teeth. Liu and coworkers (2012)48 found that proportions of pit/fissure sites with increased dentin caries treated with sealant, VF, and SDF were not significantly different at 24 months and they were all more effective than water control. Monse and associates (2012)50 found that atraumatic treatment restorations sealants were more effective than a single application of SDF after 18 months. These 4 studies of permanent teeth have not been combined in a metaanalysis because they reported outcomes using different measures (number of teeth with new caries lesions or active lesions, in all surfaces vs only pit and fissure, and provide the data in different units of measurement [means and standard deviation vs number of events]).51 No solid conclusions can be reached with such a small number of studies on permanent teeth in children.

In their recent systematic review and metaanalysis, Oliveira and colleagues49 evaluated caries prevention for primary teeth and concluded that, when compared with placebo at 24 months or more, SDF decreased the development of dentin caries lesions in treated and untreated primary teeth with a preventive fraction of 77.5%. Comparisons between SDF and FV concluded that SDF performed significantly better than FV at 18 and 30 months, and comparison between SDF and glass ionomer cements (GIC) showed that GIC was better than SDF at 12 months (not statistically significant). Both of these comparisons are weak because they are based on only 1 trial each.31,55

Because the trial from Llodra and associates46 included only primary posterior teeth and newly erupted first molars, noncavitated lesions in pit and fissures may have been difficult to code and, therefore, may have been missed. In contrast, the trial from Chu and colleagues (2002)31 studied only maxillary anterior teeth, where detection of new lesions would have been easier. Another problem making statements about the preventive effect of SDF on the whole dentition is that the trials included have reported new caries in only the teeth studied and not the whole dentition. Llodra and associates did not include any data on anterior teeth and the study by Chu and coworkers did not include any data on posterior teeth, even though they report that children had lesions and treatment in teeth not included in their study. Direct comparisons with the preventive effect of other modalities of fluoride applications are problematic, because those trials (on toothpaste of FV as an example) always report new caries in the whole dentition.

Caries Arrest and Prevention in the Elderly

In the only systematic review of SDF on adults, Hendre and colleagues53 (2017) found no studies on coronal caries, but included 3 studies on root caries arrest and prevention. They found a preventive fraction for SDF of 24% in a 24-month study and 71% over a 36-month study. The preventive fraction for caries progression was 725% greater in a 24-month study and 100% greater than placebo in a 30-month study. From these findings, the investigators recommend the use of SDF for seniors who present increased root caries risk, used alone or in conjunction with oral hygiene education and other treatments. They go on to recommend SDF use to manage dentin sensitivity, based on a 7-day trial conducted on adults that was not included in their review.52

Only 1 other systematic review and metaanalysis included SDF in their study of noninvasive treatment of root caries lesions,56 concluding that weak evidence indicates that SDF varnishes seem to be efficacious to decrease initiation of root caries. They based this conclusion on 2 studies (Tan 201067 and Zhang 201366). However, because there seem to be some discrepancies in their methodology for the metaanalysis, we did not include their data in Table 1.

Side Effects and Toxicity

None of the reviews or trials report any acute side effects of the SDF used in the conditions of the individual trials on either children or adults. Minor side effects have been described as transient gingival irritation and metallic taste in a small number of participants. Only 1 published study on adults had an as aim to study gingival erythema 24 hours and 7 days after SDF application and found that, even when there was a very small number of participants who presented mild gingival erythema at 24 hours, there was no difference from baseline at 7 days.52 This finding suggests that minor gingival irritations heal within a couple of days. A recent report from a clinical trial on young children17 states that the prevalence of tooth and gum pain reported by parents was 6.6% 1 week after application, whereas gum swelling and gum bleaching were reported by 2.8% and 4.7%, respectively. SDF should not be used on lesions that are suspected of pulpal involvement because it will not prevent further progression of the infection into surrounding tissues50 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Large lesion with cellulitis.

The main side effect of the use of SDF is the dark staining of the carious tooth tissue, which has raised concerns of parental satisfaction (see Figs. 3 and 4).54 This study, which included 799 children in 37 kindergartens in Hong Kong,17 reported that, although blackening of carious lesions was common with 38% SDF (66% to 76%), parental satisfaction with their children’s dental appearance after 30 months was 71% to 62%. A US web-based survey that used photographs of carious teeth before and after SDF treatment found that parents considered staining on posterior teeth significantly more acceptable than on anterior teeth. However, even among those who found anterior staining unsightly, a significant number of parents would accept SDF treatment to avoid advanced behavioral techniques (like sedation or general anesthesia).57 Most studies go on to recommend an appropriate informed consent so parents can understand the benefits and compromises of this therapy.36

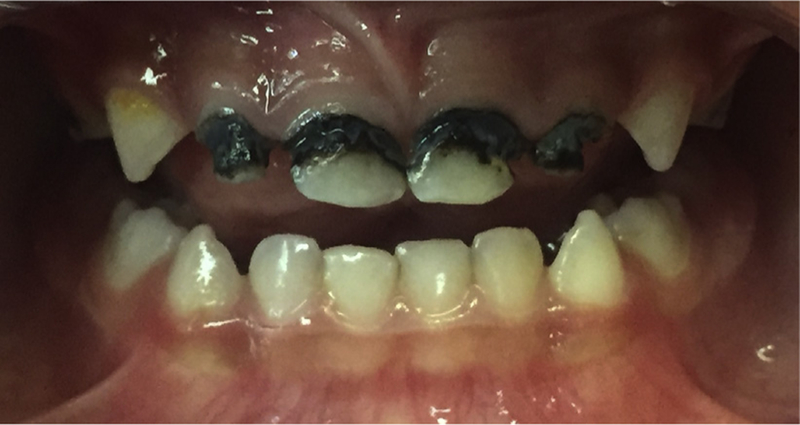

Fig. 3.

Stained arrested caries lesions on primary anterior teeth.

SDF also temporarily stains skin and gingiva, requiring them to be handled so as to avoid contact with these tissues.

Many studies have suggested the use of potassium iodide applied after SDF application to control or reverse the staining. Some commercial products with both products are available (Riva Star, SDI, Baywater, Victoria, Australia). However, one of the trials for adults58 reported that potassium iodide application had no effect in reducing the black stain on root caries, especially in the long term.

Although there has been no reported acute toxicity with SDF when used as recommended, the high concentration of fluoride has raised some concern,59 especially with repeated applications on very young children. High concentrations of silver, a heavy metal, have raised similar concerns. Investigators who have conducted many of the clinical trials cited herein60 have recommended that, although the amount of SDF applied is minute, precautions should be taken and multiple and frequent applications on young children should be avoided. The only study that reported on the pharmacokinetics of SDF after oral application61 was done on only 6 adults over a period of 4 hours using 6 mL (about one-fifth of a drop) to treat 3 teeth on each subject. Their conclusion was that serum concentrations of fluoride and silver should pose little toxicity risk when used only occasionally in adults.

To date, there are no studies that have evaluated the long-term in vivo effects of silver on the oral microbiome or the total gastrointestinal microbiome. We do not know whether there are measurable traces of silver in saliva or plasma after SDF application and whether there could be long-term cumulative effects of silver in other organs.

Conclusions

SDF promises to be a therapy that could benefit many patients. In addition of the guideline for its use published by the American Academy of Pediatric Dentistry, the World Health Organization’s 2016 report on Public Health Interventions against Early Childhood Caries, concluded that SDF can arrest dentine caries in primary teeth and prevent recurrence after treatment (very low evidence).62 It recommends its use as an alternative procedure for tertiary prevention to reduce the negative impact of established disease (cavity) by restoring function and reducing disease-related complications and to improve the quality of life for children with early childhood caries.

Limitations of Current Research

Most of the systematic reviews and metaanalysis included for this article face the obstacles of having to compile data from clinical trials that have substantial differences in treatment protocols (1 application, yearly, or twice a year applications), concentration of SDF used, dentition studied, follow-up time, outcome measured (arrest or prevention), and the way they report their findings. Their reported figures differ depending on the number of studies included and how they group the studies to make their comparisons, which may affect the generalizability of their results.

It is also important to point out that all the clinical trials cited took place in school or community settings. Extrapolating recommendations from their results to clinical practice should take into consideration the availability of the patient for follow-up. Although SDF halts the caries process and desensitizes the decayed teeth, allowing for the implementation of better home care regimes, it does not restore form and function. As patient circumstances change, SDF-treated teeth may be restored as part of a comprehensive caries management plan.36 SDF seems to be compatible with GIC and its effect on the bond strength of composite to treated dentin is still under study.53 Laboratory observations report that SDF may also increase resistance of GIC and composite restorations to secondary caries.63 Long-term clinical studies are required to recommend solid treatment protocols.

Future Research

The current reviews point to the need for studies that address the frequency and intensity of SDF used in conjunction with adjunctive preventive agents (eg, SDF with or without FV), the timing of application (eg, 1–4 times per year), and follow on restorative care (eg, glass ionomer or resin fillings). There may be differences in each of the foregoing strategies when comparing primary and permanent teeth, as well as anterior and posterior teeth. The longevity of arrest and prevention are unknown. Is SDF an agent that can be used, for example, 4 times per year, then terminated? Patient-centered outcomes also need to be addressed. The combination of clinical and patient centered outcomes will facilitate cost–benefit analysis and, thus, payment system improvement. Underlying all of this are generic biological questions, including the following: What is the impact on the oral microbiome? How does the interaction of the oral microbiome, the human genome, and SDF interact to affect caries? And finally, there is a clear need for the continued evolution of well-designed, randomized, clinical trials to produce studies with a low risk of bias during the planning, execution, and reporting of results. Standardization in the presentation of data between studies,18,51 whether they focus on arrest or prevention, is imperative to be able to combine and translate the data into strong clinical guidelines. As indicated, clinicians need to know how to manage arrested lesions for longer periods, which is important for very young children and imperative for permanent teeth.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS

From the current evidence available we can summarize that:

38% SDF solution is more effective than lower concentrations18,42;

Twice a year application is more effective than yearly applications18,42,45,51;

Over longer periods (30 months), annual applications of SDF are more effective than 3 weekly applications at baseline44;

Application times ranging from 10 seconds44 to 3 minutes47,55 achieved various degrees of success that do not seem to be time dependent;

Anterior teeth have higher rates of arrest than posterior teeth41,42,44,45;

Large lesions, occlusal lesions and those with visible plaque have less chances of arrest41,42,44 (Figs. 6 and 7);

Its use should be avoided in teeth with suspected pulpal involvement50 (see Fig. 5); and

Annual application of SDF seems to be effective for arrest and prevention of root caries on older adults who are capable of self-care. Multiple applications may benefit a more dependent and at-risk older population.53

Fig. 6.

Posterior arrest.

Fig. 7.

Posterior partial arrest.

With all age groups, clinicians should use their clinical judgment about application frequency based on individual caries risk factors, fluoride exposure, patient needs, and taking into consideration individual social determinants of health.

Clinical application is simple: the lips are protected with petroleum jelly (Vaseline) or lip balm, the tooth is isolated with cotton rolls, the lesion is cleaned of food debris and dried, and SDF is painted onto the clean lesion and allowed to air dry (Fig. 8 and https://youtu.be/p9Tazwitcao). Rinsing after application does not seem to be necessary.

Fig. 8.

Silver diamine fluoride application.

INDICATIONS

At the tooth level, SDF therapy for caries arrest is indicated for cavitated lesions on coronal or root surfaces that are not suspected to have pulpal involvement, are not symptomatic, and are cleansable. Ideally, these conditions should be verified by radiographic evaluation.

PATIENT SELECTION AND MANAGEMENT

Patients who do not have immediate access to traditional restorative care can benefit from SDF therapy to arrest existing dentin caries lesions. This therapy is contraindicated on patients who report a silver allergy. Patients should be monitored closely to verify arrest of all lesions on a periodic basis based on risk factors; this is especially important when applied to permanent teeth. Follow-up should ideally include radiographic examination and the caries management plan should include plaque control, dietary counseling, combination of other fluoride modalities for caries prevention (like F varnish, fluoride gels, fluoride rinses and fluoride toothpaste) and sealants, depending on patient’s age and individual situation. Follow-up on large lesions or lesions in hard-to-clean areas can be combined with the use of glass ionomer restorations or traditional restorative treatment, as patient circumstances allows.

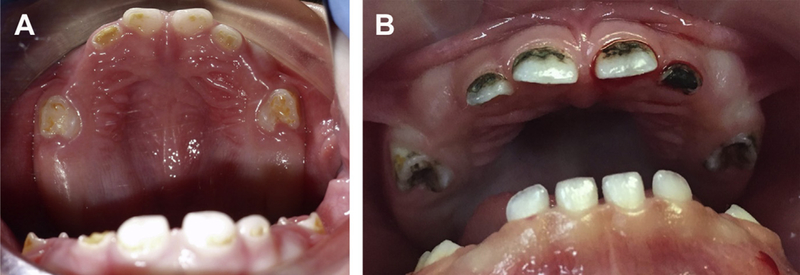

Fig. 2.

(A) Caries lesions on enamel and dentin on young primary teeth. (B) Same lesions showing staining after SDF treatment.

KEY POINTS.

Silver diamine fluoride incorporates the antibacterial effects of silver and the remineralizing actions of a high-concentration fluoride. It effectively arrests the disease process on most lesions treated.

Systematic reviews of clinical trials confirm the effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride as a caries-arresting agent for primary teeth and root caries and its ease of use, low cost, and relative safety.

No caries removal is necessary to arrest the caries process, so the use of silver diamine fluoride is appropriate when other forms of caries control are not available or feasible.

A sign of arrest is the dark staining of the lesions and affected tooth structures. That could be a deterrent for patients who have esthetic concerns. A thorough informed consent is recommended to ensure high patient satisfaction.

Silver diamine fluoride use for caries control is recommended as part of a comprehensive caries management program, where individual needs and risks are considered.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure: Research reported in this work was partially funded by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities of the National Institutes of Health under Awards Numbers R01MD011526 and a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) award (PCS-1609–36824). The views presented in this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sheiham A, Williams DM, Weyant RJ, et al. Billions with oral disease: a global health crisis–a call to action. J Am Dent Assoc 2015;146(12):861–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen PE, Lennon MA. Effective use of fluorides for the prevention of dental caries in the 21st century: the WHO approach. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2004;32(5):319–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Petersen PE, Ogawa H. Prevention of dental caries through the use of fluoride– the WHO approach. Community Dent Health 2016;33(2):66–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thompson FE, McNeel TS, Dowling EC, et al. Interrelationships of added sugars intake, socioeconomic status, and race/ethnicity in adults in the United States: National Health Interview Survey, 2005. J Am Diet Assoc 2009;109(8):1376–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bagramian RA, Garcia-Godoy F, Volpe AR. The global increase in dental caries. A pending public health crisis. Am J Dent 2009;22(1):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaffee BW, Rodrigues PH, Kramer PF, et al. Oral health-related quality-of-life scores differ by socioeconomic status and caries experience. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2017;45(3):216–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crystal YO, Niederman R. Silver diamine fluoride treatment considerations in children’s caries management. Pediatr Dent 2016;38(7):466–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horst JA. Silver fluoride as a treatment for dental caries. Adv Dent Res 2018; 29(1):135–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregory D, Hyde S. Root caries in older adults. J Calif Dent Assoc 2015;43(8): 439–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Featherstone JDB. Remineralization, the natural caries repair process–the need for new approaches. Adv Dent Res 2009;21:4–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Niederman R, Feres M, Ogunbodede E. Dentistry. In: Debas HT, Donkor P, Gawande A, et al. , editors. Essential surgery: disease control priorities Washington, DC: The 2015 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; 2015. p. 173–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mei ML, Li QL, Chu CH, et al. Antibacterial effects of silver diamine fluoride on multi-species cariogenic biofilm on caries. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 2013; 12:4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mei ML, Ito L, Cao Y, et al. Inhibitory effect of silver diamine fluoride on dentine demineralisation and collagen degradation. J Dent 2013;41(9):809–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chu CH, Lo EC. Microhardness of dentine in primary teeth after topical fluoride applications. J Dent 2008;36(6):387–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mei ML, Nudelman F, Marzec B, et al. Formation of fluorohydroxyapatite with silver diamine fluoride. J Dent Res 2017;96(10):1122–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mei ML, Chu CH, Low KH, et al. Caries arresting effect of silver diamine fluoride on dentine carious lesion with S. mutans and L. acidophilus dual-species cariogenic biofilm. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal 2013;18(6):e824–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Duangthip D, Fung MHT, Wong MCM, et al. Adverse effects of silver diamine fluoride treatment among preschool children. J Dent Res 2018;97(4):395–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao SS, Zhao IS, Hiraishi N, et al. Clinical trials of silver diamine fluoride in arresting caries among children: a systematic review. JDR Clin Transl Res 2016;1(3):201–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Higginbottom J On the use of the nitrate of silver in the cure of erysipelas. Prov Med Surg J 1847;11(17):458–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stebbins EA. What value has argenti nitras as a therapeutic agent in dentistry? Int Dent J 1891;12:661–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seltzer S, Werther L. Conservative silver nitrate treatment of borderline cases of deep dental caries. J Am Dent Assoc 1941;28(October):1586–91. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Howe PR. A method of sterilizing and at the same time impregnating with a metal affected dentinal tissue. Dental Cosmos 1917;59(9):891–904. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seltzer S The comparative value of various medicaments in cavity sterilization. J Am Dent Assoc 1941;28(November):1844–52. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Seltzer S Medication and pulp protection for the deep cavity in a child’s tooth. J Am Dent Assoc 1949;39(August):148–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zander HA. Use of silver nitrate in the treatment of caries. J Am Dent Assoc 1941; 28(8):1260–7. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bibby BG. Use of fluorine in the prevention of dental caries. J Am Dent Assoc 1944;31(3):228–36. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishino M, Yoshida S, Sobue S, et al. Effect of topically applied ammoniacal silver fluoride on dental caries in children. J Osaka Univ Dent Sch 1969;9:149–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yamaga R, Nishino M, Yoshida S, et al. Diamine silver fluoride and its clinical application. J Osaka Unic Dent Sch 1972;12(20):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gotjamanos T Pulp response in primary teeth with deep residual caries treated with silver fluoride and glass ionomer cement (‘atraumatic’ technique). Aust Dent J 1996;41(5):328–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mei ML, Chin-Man Lo E, Chu CH. Clinical use of silver diamine fluoride in dental treatment. Compend Contin Educ Dent 2016;37(2):93–8 [quiz: 100]. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chu CH, Lo ECM, Lin HC. Effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride and sodium fluoride varnish in arresting dentin caries in Chinese pre-school children. J Dent Res 2002;81(11):767–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ElevateOralCare. Advantage arrest SDF 38% bottle Available at: http://www.elevateoralcare.com/dentist/AdvantageArrest/Advantage-Arrest-Silver-Diamine-Fluoride-38. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 33.ElevateOralCare. Advantage arrest: SDF 38% product package insert Available at: http://www.elevateoralcare.com/site/images/AA_PI_040715.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 34.ElevateOralCare. Safety data sheet. Advantage arrest SDF 38% Available at: http://www.elevateoralcare.com/site/images/AASDS082415.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2018.

- 35.Horst JA, Ellenikiotis H, Milgrom PL. UCSF protocol for caries arrest using silver diamine fluoride: rationale, indications and consent. J Calif Dent Assoc 2016; 44(1):16–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crystal YO, Marghalani AA, Ureles SD, et al. Use of silver diamine fluoride for dental caries management in children and adolescents, including those with special health care needs. Pediatr Dent 2017;39(5):135–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.ElevateOralCare. The silver bulletin 1 2017. Available at: http://www.elevateoralcare.com/Landing-Pages/silverbulletinv1. Accessed September 16, 2018.

- 38. Phase III RCT of the effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride in arresting cavitated caries lesions NIH report. Project Information; 2017.

- 39.Rosenblatt A, Stamford TC, Niederman R. Silver diamine fluoride: a caries “silver-fluoride bullet”. J Dent Res 2009;88(2):116–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62(10): 1006–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fung MHT, Duangthip D, Wong MCM, et al. Arresting dentine caries with different concentration and periodicity of silver diamine fluoride. JDR Clin Transl Res 2016; 1(2):143–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fung MHT, Duangthip D, Wong MCM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of 12% and 38% silver diamine fluoride treatment. J Dent Res 2018;97(2):171–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Duangthip D, Chu CH, Lo EC. A randomized clinical trial on arresting dentine caries in preschool children by topical fluorides–18 month results. J Dent 2016; 44:57–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Duangthip D, Wong MCM, Chu CH, et al. Caries arrest by topical fluorides in pre-school children: 30-month results. J Dent 2018;70:74–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhi QH, Lo EC, Lin HC. Randomized clinical trial on effectiveness of silver diamine fluoride and glass ionomer in arresting dentine caries in preschool children. J Dent 2012;40(11):962–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Llodra JC, Rodriguez A, Ferrer B, et al. Efficacy of silver diamine fluoride for caries reduction in primary teeth and first permanent molars of schoolchildren: 36-month clinical trial. J Dent Res 2005;84(8):721–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braga MM, Mendes FM, De Benedetto MS, et al. Effect of silver diamine fluoride on incipient caries lesions in erupting permanent first molars: a pilot study. J Dent Child (Chic) 2009;76(1):28–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu BY, Lo EC, Chu CH, et al. Randomized trial on fluorides and sealants for fissure caries prevention. J Dent Res 2012;91(8):753–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Oliveira BRA, Veitz-Keenan A, Niederman R. The effect of silver diamine fluoride in preventing caries in the primary dentition: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res 2018;53(1):24–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monse B, Heinrich-Weltzien R, Mulder J, et al. Caries preventive efficacy of silver diamine fluoride (SDF) and ART sealants in a school-based daily fluoride tooth-brushing program in the Philippines. BMC Oral Health 2012;12:52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chibinski AC, Wambier LM, Feltrin J, et al. Silver diamine fluoride has efficacy in controlling caries progression in primary teeth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res 2017;51(5):527–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Castillo JL, Rivera S, Aparicio T, et al. The short-term effects of diamine silver fluoride on tooth sensitivity: a randomized controlled trial. J Dent Res 2011;90(2): 203–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hendre AD, Taylor GW, Chavez EM, et al. A systematic review of silver diamine fluoride: effectiveness and application in older adults. Gerodontology 2017; 34(4):411–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nelson T, Scott JM, Crystal YO, et al. Silver diamine fluoride in pediatric dentistry training programs: survey of graduate program directors. Pediatr Dent 2016; 38(3):212–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.dos Santos VE Jr, de Vasconcelos FMN, Ribeiro AG, et al. Paradigm shift in the effective treatment of caries in schoolchildren at risk. Int Dent J 2012;62(1):47–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wierichs RJ, Meyer-Lueckel H. Systematic review on noninvasive treatment of root caries lesions. J Dent Res 2015;94(2):261–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Crystal YO, Janal MN, Hamilton DS, et al. Parental perceptions and acceptance of Silver Diamine Fluoride (SDF) staining. J Am Dent Assoc 2017;148(7): 510–8.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li R, Lo EC, Liu BY, et al. Randomized clinical trial on arresting dental root caries through silver diamine fluoride applications in community-dwelling elders. J Dent 2016;51:15–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gotjamanos T Safety issues related to the use of silver fluoride in paediatric dentistry. Aust Dent J 1997;42(3):166–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chu CH, Lo EC. Promoting caries arrest in children with silver diamine fluoride: a review. Oral Health Prev Dent 2008;6(4):315–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vasquez E, Zegarra G, Chirinos E, et al. Short term serum pharmacokinetics of diamine silver fluoride after oral application. BMC Oral Health 2012;12:60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Phantumvanit P, Makino Y, Ogawa H, et al. WHO global consultation on public health intervention against early childhood caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 2018;46(3):280–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mei ML, Zhao IS, Ito L, et al. Prevention of secondary caries by silver diamine fluoride. Int Dent J 2016;66(2):71–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yee R, Holmgren C, Mulder J, et al. Efficacy of silver diamine fluoride for Arresting Caries Treatment. J Dent Res 2009;88(7):644–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.dos Santos VE Jr, Vasconcelos Filho A, Ribeiro Targino AG, et al. A New “Silver-Bullet” to treat caries in children - Nano Silver Fluoride: A randomised clinical trial. Journal of Dentistry 2014;42(8):945–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang W, McGrath C, Lo EC, et al. Silver diamine fluoride and education to prevent and arrest root caries among community-dwelling elders. Caries Res 2013; 47(4):284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tan HP, Lo EC, Dyson JE, et al. A randomized trial on root caries prevention in elders. J Dent Res 2010;89(10):1086–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Seberol EO. Z. Caries arresting effect of silver diamine fluoride on primary teeth. J Dent Res 2013;Vol. 92 (Spec Iss C) abstract 48 (World Congress on Preventive Dentistry). [Google Scholar]