Abstract

Thrombin and activated protein C (APC) are known coagulation factors that exhibit profound effects in brain by acting on the protease activated receptor (PAR). The wild type (WT) proteases appear to impact cell survival powerfully, and therapeutic forms of APC are under development. Engineered recombinant thrombin or APC were designed to separate their procoagulant or anticoagulant effects from their cytoprotective properties. We measured vascular disruption and neuronal degeneration after a standard rodent filament stroke model. For comparison to a robust anticoagulant, we used a GpIIb/IIIa inhibitor, GR144053. During 2 h MCAo both WT murine APC and its mutant, 5A-APC, significantly decreased neuronal death 30 min after reperfusion. During 4 h MCAo, only 5A-APC significantly protected neurons but both WT-APC and 5A-APC exacerbated vascular disruption during 4 h MCAo. Human APC mutants appeared to reduce 24 h neuronal injury significantly when given after 2 h delay after MCAo. In contrast, 24 h vascular damage was worsened by high doses of WT and mutant APCs, although only statistically significantly for high dose 3K3A-APC. Mutated thrombin worsened vascular damage significantly without affecting neuron damage. GR144053 failed to ameliorate vascular disruption or neuronal injury despite significant anticoagulation. Differential effects on neurons and the vasculature were demonstrated using wild-type and mutated proteases. The mutants murine 3K3A-APC and 5A-APC protected neurons in this rodent model but in high doses worsened vascular leakage. Cytoactive effects of plasma proteases may be separated from their coagulation effects. Further studies should explore impact of dose and timing on cytoactive and vasculoactive properties of these drugs.

Keywords: stroke, thrombin, PAR-1, APC, neurovascular unit

1. Introduction

Brain anatomy includes multiple, specialized cell types that function together, a concept named the ‘neurovascular unit’ or NVU(del Zoppo, 2010). Therapies applied to intact brain affect all elements of the NVU at one time without regard to differential vulnerabilities of these elements. A generation of failed clinical stroke trials ignored the NVU, raising the question whether therapy might be more successful if elements of the NVU were specifically targeted(Bai and Lyden, 2015; Lee et al., 2004). Different mechanisms of cytotoxicity proceed over radically different time frames(Dirnagl, 2012) and it is reasonable to hypothesize that cells comprising the NVU might respond to insults—and cytoprotection—differently.

During ischemia, the blood brain barrier (BBB) opens, allowing brain entry of plasma constituents. For decades, damage after cerebral ischemia was attributed to edema, the uncontrolled BBB permeability to water entry. Recently, considerable attention has focussed on potential toxic effects of some of the circulating proteins—notably proteases—entering brain during BBB leakage(Chen et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012). At this time, it is not clear whether these protease cytotoxins in vivo act directly to kill neurons or cause significant vascular injury that then permits other toxic agents to enter brain and kill neurons.

Considerable evidence suggests that plasma proteases, notably thrombin and plasmin, are directly cytotoxic acting via protease-activated receptors (PARs), of which there are four types(Coughlin, 2000; Rajput et al., 2014). In humans and rodents, PAR-1 is found on neurons, endothelial cells and astrocytes. On the surface of the neuron and endothelial cell, activated protein C (APC) acts on PAR-1 in the presence of endothelial protein C receptor, EPCR(Coughlin, 1999; Gorbacheva et al., 2009; Riewald et al., 2002). On neurons, APC acts on PAR-1 in the presence of EPCR and PAR-3(Guo et al., 2004; Sinha et al., 2018). Astrocytes express the PAR-1 receptor as well, and astrocytic PAR-1 has been linked to injury response(Junge et al., 2004; Sweeney et al., 2017). While thrombin acts on PAR-1 to promote inflammation, vascular leakage, and cell killing, APC can act on the same receptor to produce cytoprotection. These divergent signalling effects—termed ‘biased agonism’—result when proteases act at different sites: thrombin cleaves the extracelluar PAR-1 N-terminus only at Arg41 while APC can cleave not only at Arg41 but also at Arg46. These two different cleavages result in different extracellular tethered agonist-ligands that interact intramolecularly with PAR-1 to cause either cytotoxic or cytoprotective signalling, respectively, depending on whether PAR-1’s new N-terminus begins with Ser42 or Asn47 (Mosnier et al., 2012; Sinha et al., 2018).

Both thrombin and APC are blood constituents playing key roles in the coagulation cascade. Prothrombin is converted to thrombin by activated Factor X, after which thrombin cleaves fibrinogen to fibrin and activates platelets as part of a blood clotting response. To halt or limit clotting, protein C is activated by thrombin to form APC, which reduces clotting by proteolysis of clotting factors Va and VIIIa(Griffin et al., 2012). Binding sites on the proteases thrombin and APC involve amino acid sequences that are distinct from the protease’s sites involved in cleaving PAR-1(Mosnier et al., 2012). Thus, variants of thrombin and APC can be created to separate their coagulation effects from their ability to activate PARs(Griffin et al., 2016b; Mosnier et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2016). Some of these mutated APCs as well as WT-APC appear to stabilize BBB and reduce bleeding during thrombolysis(Cheng et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2013b). Using site-directed mutagenesis, APC has been engineered to have much less effect on coagulation than WT-APC while retaining full cytoprotective effects(Griffin et al., 2016a; Griffin et al., 2016b; Mosnier et al., 2007; Mosnier et al., 2009). After changing 3 lysines for 3 alanines in the protein C protease domain, the human 3K3A-APC mutant retains normal PAR-1 activating activity but has less than 10% anticoagulant activity than the WT-APC(Guo et al., 2013). Changing the same 3 lysines plus 2 additional arginines for 5 alanines in the protease domain of murine APC similarly reduces anticoagulant activity in a mutant named murine 5A-APC(Wang et al., 2013a). The thrombin double mutant W215A/E217A—named WE thrombin—shows modestly reduced ability to activate protein C and greatly reduced ability to cleave fibrinogen whereas it consequently exhibits some modest neuroprotective effects in a murine stroke model(Berny-Lang et al., 2011; Feistritzer et al., 2006). WE thrombin does not significantly act on PAR1.

Proteases engineered to lose most of their procoagulant or anticoagulant activities offer the potential to differentiate PAR actions on neurons (neuroprotection) and on endothelial cells (vasculoprotection) from their effects on plasma coagulation pathways. Greater understanding of the effects of proteases on the cells comprising the NVU could influence clinical trials significantly: if neuronal injury is tied directly to vascular disruption then it would be more effective to focus therapy on vascular protection. Alternatively, if proteases act directly on neurons independent of vascular reactions, then therapies directly targeting neuronal protection may be more valuable.

In this proof-of-concept study, we used mutated murine recombinant proteases (WT-APC, 3K3A-APC, 5A-APC, and WE Thrombin) to alter vascular damage or neuronal degeneration. We show independent and differential effects on cells in the NVU at different protease doses, suggesting the possibility that future stroke treatment could be more successful by targeting the individual elements of the NVU.

2. Results

2.1. Protocol Exclusions:

There were 9 animals excluded from the trial due to demise during MCAo surgery and before any treatment randomization. There were 2 animals excluded prior to treatment randomization because they lacked any stroke symptoms during reperfusion; all remaining animals exhibited 2 or 3 neurological signs during reperfusion, indicating adequate ischemia. A final 3 animals were excluded after treatment because they died of severe stroke before the 24 h evaluation: 2 saline and 1 WE thrombin.

2.2. Antiplatelet therapy during ischemia:

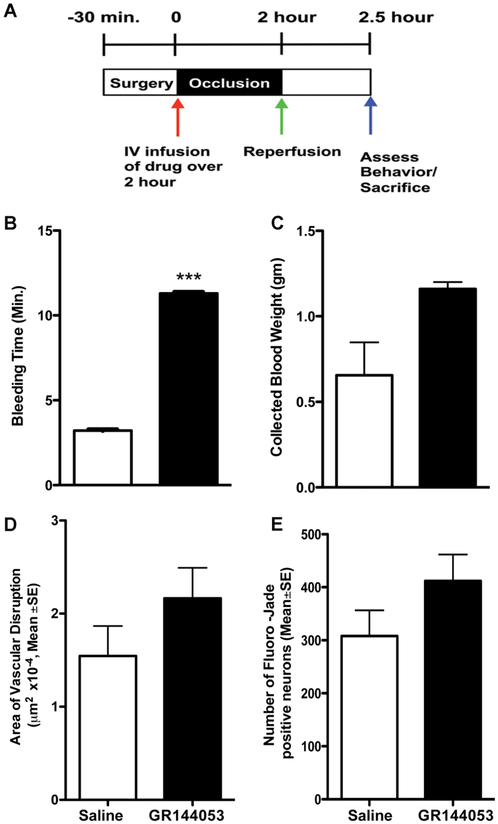

The glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor GR144053 inhibits platelets and thrombosis without affecting PAR-1. The drug was given at onset of 2 h unilateral left MCAo and brains were removed 30 min later (Fig. 1A). We selected a dose of GR144053 that increased bleeding (Figs. 1B and 1C) significantly, confirming anti-thrombotic effects. When given at the onset of 2 h MCAo, we found that this anti-platelet agent failed to reduce 30 min vascular damage, as measured by leakage of 2MDa-dextran conjugated to FITC, in the ischemic area (Fig. 1D). We have published extensive validation data showing that leakage of the very large 2MDa-dextran FITC occurs only in areas of severe BBB disruption(Chen et al., 2009). The drug also had no significant effect on 30 min cell injury (Fig. 1E). These data illustrate that simply inhibiting clotting with an anti-platelet agent does not confer benefit during MCAo in this model, confirming findings that have been shown previously using a variety of anticoagulants(Adams et al., 1999; Adams et al., 2008; Bath et al., 2000).

Figure 1. Antiplatelet therapy provides no protection despite anticoagulation.

The experimental design is illustrated in (A) where time=0 is the onset of the MCAo. Reperfusion is the time the occluding filament is removed, restoring flow into the MCA. In unlesioned animals, n=5, the GpIIb/IIIa inhibitor GR144043 (2mg/kg intravenous over 10 min) significantly increased bleeding time (minutes), shown in (B). The collected blood volumes were increased but not significantly, shown in (C) as the weight of the collection paper in gm. The same dose of GR144043 (n=7) showed no significant effect on vascular damage, as measured using 2 MDa FITC-dextran extravasation in (D). The area of vascular damage is reported in μm2, converted to single digits by multiplying by 10−4. Similarly, there was no effect on the number of Fluoro-Jade C positive degenerating neurons, compared to saline treatment after 2hr MCAo in (E), shown as number per mm2. ***P<0.001, Students t-test for independent samples. All data are shown as mean ±SE.

2.3. PAR-1 targeted therapies during ischemia:

In unlesioned animals (n=4), intravenous infusions of WT-APC (0.2 mg/kg), 5A-APC (0.2 mg/kg) or WE thrombin (low dose 8 μg/kg or high dose 16 μg/kg) showed no significant changes in PT or PTT by 30 min after infusion (Supplemental Figure).

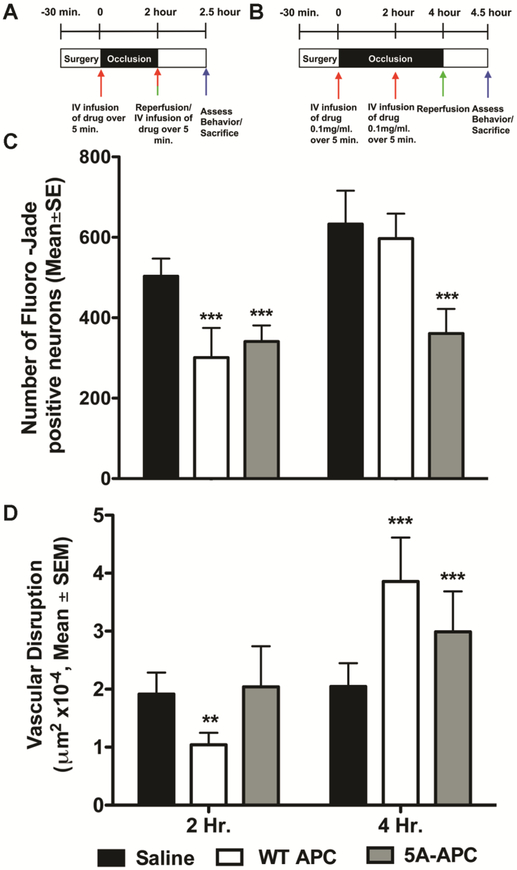

We administered recombinant murine WT-APC (0.2mg/kg) or 5A-APC (0.2mg/kg) intravenously in divided doses, half at the onset of 2 h MCAo (Fig. 2A) or 4 h MCAo (Fig. 2B) and the remainder after 2 hours. At 24 h following unilateral MCAo, the neurological deficit scores ranged between 2 and 3 in all groups, with no significant differences (data not shown). During 2 h unilateral MCAo both WT-APC and 5A-APC significantly decreased neuronal death 30 min after reperfusion but during 4 h MCAo, only 5A-APC significantly protected neurons (Fig. 2C). In contrast, during 2 h MCAo, WT–APC treatment significantly decreased severe 30 min vascular damage compared to saline and 5A-APC while during a longer 4 h MCAo both WT-APC and 5A-APC significantly worsened 30 min vascular disruption (Fig. 2D). These data illustrate that APC impacts the BBB and the neurons differently, depending on dose, timing, duration of ischemia, and whether the WT APC molecule is mutated. Moreover, 5A-APC significantly reduced neuronal injury during either 2 h or 4 h MCAo although it exacerbated vascular disruption during 4 h MCAo (Fig. 2 C and D). Taken together, these data suggest that in this model protease-mediated neuroprotection can proceed independently from an effect on the vasculature, at the doses we studied.

Figure 2. Separable APC effects on neuroprotection compared to vasculoprotection during ischemia.

The experimental scheme is shown in (A) and (B) in which MCAo begins at time=0. WT-APC (0.2mg/kg) or 5A-APC (0.2mg/kg) were given intravenously in divided doses, half at the onset of MCAo and the remainder after 2 h. Reperfusion started at either 2 h (Fig. 1A) or 4 h (Fig. 1B) after MCAo onset. Significant neuronal protection compared to saline treatment — measured as number of Fluoro-Jade C positive cells per mm2—was observed in animals treated with WT-APC or 5A-APC during 2 h MCAo but during 4 h MCAo, only 5A-APC showed neuroprotection, shown in (C). When given during 2 h MCAo in these doses, only WT-APC significantly reduced vascular disruption, but when given during 4 h MCAo, both WT-APC and 5A-APC worsened vascular damage as in (D), reported in μm2, converted to single digits by multiplying by 10−4. In all panels, n=10 per group, data is presented as mean ±SE. ***P<0.001, ** p<0.01, One-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons against saline.

2.4. PAR-1 targeted therapies after ischemia:

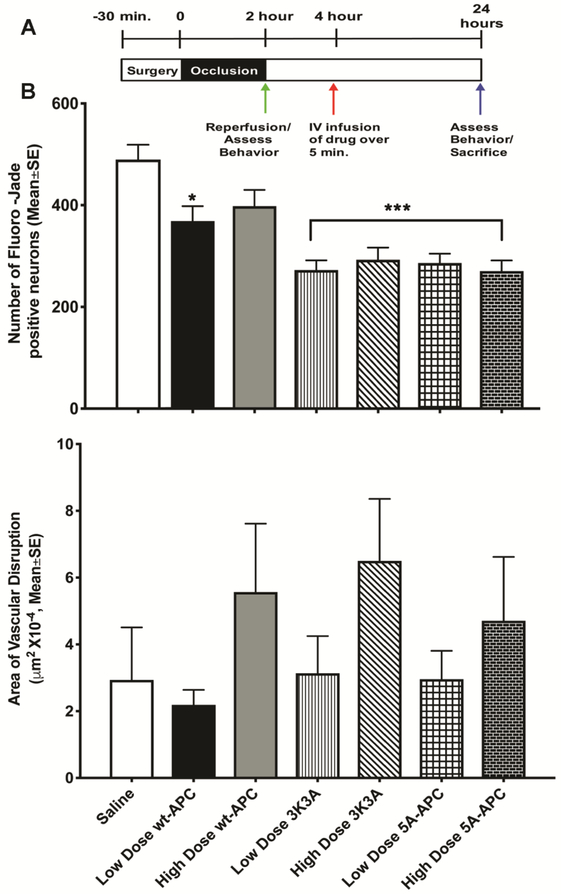

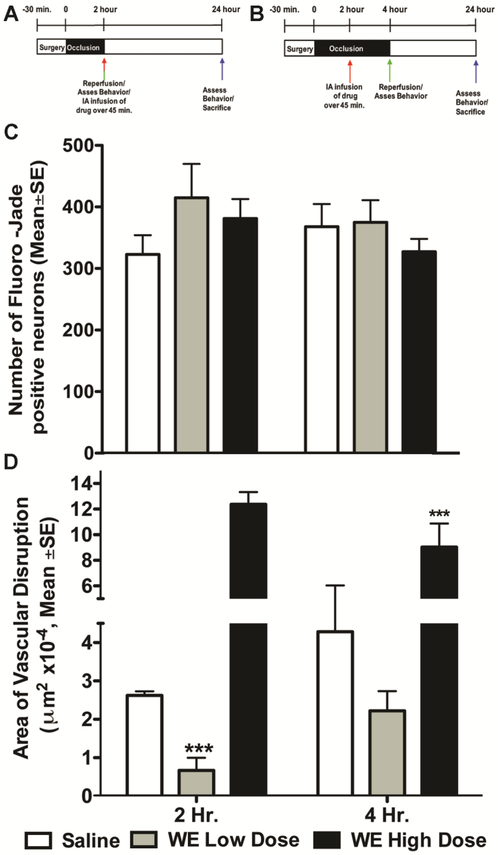

In clinical practice, protective therapies are provided sometime after stroke onset, and often following recanalization therapy; therefore, we administered low (0.2 mg/kg) or high dose (0.4 mg/kg) WT-APC, 5A-APC, or 3K3A-APC after 2 h following the end of a 2 h unilateral left MCAo (Fig. 3A), that is, 4 hours after occlusion. After 24 h all neurological deficit scores were between 2 and 3, with no differences among the groups (data not shown). The two APC mutants reduced 24 h neuronal injury significantly (Fig. 3B). In contrast, 24 h vascular damage was only statistically significantly elevated after treatment with high dose 3K3A-APC (Fig. 3C). These data further support differential effects on neurons compared to the BBB by these drugs, and further emphasize that neuronal protection can be demonstrated independently of vascular disruption. To confirm these observations, we administered a different mutated protease, WE thrombin, 2 h after onset of 2 h or 4 h MCAo (Fig. 4A). This dosing scheme was used to allow comparison to our prior work using WT thrombin(Chen et al., 2012). WE thrombin shows anticoagulant activity and relatively little direct activity on PAR1; however, due to increased generation of endogenous APC, WE thrombin shows cytoprotective actions at some doses(Marino et al., 2010). At the doses we used, WE thrombin did not affect coagulation (Supplemental Figure). After 2 h MCAo, neither dose of WE thrombin changed 24 h neuron injury (Fig. 4C) whereas the low dose reduced—but the high dose worsened—24 h vascular damage (Fig. 4D). These data for WE thrombin contrast markedly with data showing that WT thrombin significantly injures neurons and disrupts vasculature(Chen et al., 2012).

Figure 3. Separable APC effects on neuroprotection compared to vasculoprotection after ischemia.

The experimental scheme is shown in Panel (A): WT-APC, 5A-APC or 3K3A-APC were given intravenously as high dose (0.4mg/kg) or low dose (0.2mg/kg) after 2 h following the end of 2 h MCAo, i.e. after 2 h reperfusion. Significant neuronal protection compared to saline treatment—measured 24 h later as number of Fluoro-Jade C positive cells per mm2—was observed in animals treated with 3K3A-APC and 5A-APC but not with WT-APC, as shown in (B). When given 2 h after a 2 h MCAo in these doses, high doses of 3K3A-APC worsened 24 h vascular disruption, but low doses of all 3 proteins did not, as shown in (C) as μm2, converted to single digits by multiplying by 10−4. In all panels, n=11 per group, data is presented as mean ±SE. *P<0.05, *** p<0.001, one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons against saline.

Figure 4. Separable WE Thrombin effects on neuroprotection compared to vasculoprotection during ischemia.

The experimental scheme is shown in Panel (A) and (B): WE thrombin was infused via a carotid arterial catheter as high dose (16 μg/kg) or low dose (8 μg/kg) over 45m beginning 2 h after occlusion during 2 h or 4 h MCAo. There was no statistically significant effect on 24 h neuronal protection (number of Fluoro-Jade positive neurons per mm2) compared to saline treatment with either of these doses as in (C). When given after a 2 h MCAo, low dose WE thrombin reduced 24 h vascular damage but there was no effect when WE thrombin was given during 4 h MCAo; High dose WE thrombin significantly worsened 24 h vascular damage after 2 h or 4 h MCAo, as shown in (D) as μm2, converted to single digits by multiplying by 10−4. In all panels, n=11 per group, data is presented as mean ±SE. ***P<0.001, one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Dunnett’s test for multiple comparisons against saline.

3. Discussion

3.1. Summary of Results

We illustrated two key and novel observations about the NVU and cytoprotection. First, our data suggest that protease/PAR-1 mediated neuronal protection appears to be separable from effects on vascular damage. We used engineered mutants of thrombin and APC, using different doses and dosing schedules. Multiple measures of outcome showed that protease/PAR mediated suppression of neuronal injury appears to proceed independently of vascular disruption. Second, we showed that anticoagulation provides little to no protection during focal ischemia in rodents, a finding consistent with the failure of large clinical trials of anticoagulants for acute ischemic stroke. These results have clinical implications: agents that protect the BBB after thrombolysis might reduce vascular damage (and potentially hemorrhage), while other agents might be developed to target neuronal protection specifically. While both low and high doses of mutant APC appeared to block neuronal degeneration, high-dose murine 3K3A-APC significantly augmented vascular damage in this rat model (Fig. 3). For human stroke trials, therefore, dose selection and mutant selection of PAR-acting agents must proceed cautiously.

3.2. Neuroprotection can be Separated from Anticoagulation

Recently, considerable attention has been focused on mutant APC as possible treatment for a variety of neurological injuries and neurodegenerative conditions(Griffin et al., 2016a; Griffin et al., 2016b; Zlokovic BV, 2011). In the present study, we used the murine 5A-APC variant with less than 10% of the murine WT-APC anticoagulation property, leaving a molecule that is cytoprotective by anti-apoptotic and anti-inflammatory effects through cell signalling via PAR-1 and other receptors. We also used murine 3K3A-APC, which retains about 20% of the anticoagulant property seen in murine WT-APC and showed effective cytoprotection(Mosnier et al., 2007; Mosnier et al., 2012). In this study, murine APCs were used in rats, so we verified absence of measurable anticoagulant activities (Supplementary Figure) because there are known species-dependent variations(Guo et al., 2009). When given during ischemia, WT-APC effectively decreased vascular damage and provided neuroprotection in animals subjected to 2 h MCAo (Fig. 2C, D); mutated 5A-APC did not significantly reduce 30 min vascular damage (Fig. 2D) but showed a significant neuroprotection in 2 h MCAo subjects (Fig. 2C).

Our data confirm and extend the prediction that beneficial neuroprotection by APC mutants is mediated via cell signalling involving the PAR-1, PAR-3 and other receptors rather than via anticoagulant effects on prothrombotic mechanisms(Bai and Lyden, 2015). Substantial previous literature showed mixed results in experimental animals, but data from human clinical trials suggest that anticoagulation for acute ischemic stroke per se fails to reduce stroke size or improve behavioral outcomes(Adams et al., 1999; Adams et al., 2008; Bath et al., 2000). In prior work, we have shown potent neuroprotection with argatroban, a direct thrombin inhibitor(Chen et al., 2012; Lyden et al., 2014). While the protective effects of argatroban have been definitively linked to a PAR-1 requiring pathway(Rajput et al., 2014), we did seek additional confirmation using an agent to inhibit thrombosis without affecting thrombin directly, the GpIIb/IIIa inhibitor GR144053. Despite prolonged bleeding (Figs. 1B and 1C), this anticoagulant provided no beneficial neuroprotection, and may have worsened the neurovascular damage typical of this MCAo model (Figs. 1C and 1D). On the other hand, molecules with targeted mutations that successfully reduced or eliminated anticoagulation protected neurons after single boluses (Figs. 2C and 2D), and especially when treatment was delayed to a clinically relevant time (Fig. 3). These findings imply that anticoagulant activity may not primarily benefit outcome whereas inhibiting thrombin’s action on PAR-1 as well as promoting APC’s biased agonism of PAR-1 may be beneficial. WT and mutant APCs have no effects on systemic variables in healthy humans(heart rate, blood pressure, temperature, cerebral blood flow) that might confound these studies(Lyden et al., 2013). Our data illustrate the need for further studies in this area.

3.3. Neuroprotection is Separable from Vascular Disruption

3.3.1. Mutations in the APC molecule.

Interestingly, when given in the clinically-relevant time frame of 4 h after stroke onset, and 2 h after reperfusion (Fig. 3A), low dose 3K3A and 5A offered 24 h neuroprotection (Fig. 3B) without any observable deleterious effect on 24 h vascular damage (Fig. 3C). High dose 5A-APC and 3K3A-APC significantly blocked (reduced) 24 h neuronal degeneration (Fig. 3B), with no statistically significant increase in 24 h vascular damage (Fig. 3C). These findings support the inference of differential protective effects in the NVU and further speak to the known dose-dependency of proteases like thrombin: lower doses tend to be protective while higher doses cause harm(Garcia et al., 2015; Krenzlin et al., 2016). That both 5A-APC and 3K3A-APC showed benefit when given as late as 4 h after stroke onset bodes well for potential success in human stroke trials(Lyden et al., 2016). Interestingly, during the longer 4 h MCAo, both WT-APC and 5A-APC worsened 30 min vascular damage, yet 5A-APC protected neurons (Fig. 2C, D), further emphasizing differential effects in the NVU. That robust neuroprotection could be observed simultaneously with augmented vascular damage is surprising, but powerfully supports an inference that neurotoxicity can proceed independently from vascular damage under the conditions used for this MCAo model. One possible explanation is that, depending on the timing and dose of APC, there may be more cleavage in PAR-1 at Arg41 by APC than at Arg46, which actually would then reflect proinflammatory and vaculodisruptive actions by APC. Such appears to be the case in a murine MCAo model when mice carrying a homozygous mutation of Arg46 to Gln were treated with APC: in the presence of PAR-1 but the absence of Arg46, APC appeared to do more harm than good(Sinha et al., 2018).

3.3.2. Mutations in the thrombin molecule.

WE thrombin shows anticoagulant activity and relatively little direct activity on PAR1; however, due to increased generation of APC, WE thrombin shows cytoprotective actions at some doses(Marino et al., 2010). WE thrombin reduced the infarct volume in mice(Berny-Lang et al., 2011). Here we found in rats that WE thrombin showed dose dependent effects on vasculature (Fig. 4D) without the significant neurotoxicity associated with WT thrombin (Fig. 4D)(Chen et al., 2012). Low dose WE thrombin showed decreased 24 h vascular damage in rats subjected to 2 h MCAo but high dose WE thrombin increased 24 h vascular damage, consistent with known dose-related pleiotropic effects of thrombin (Fig. 4D)(Krenzlin et al., 2016). Here, the lack of neurotoxicity in the face of markedly augmented vascular disruption (Figs. 4C and 4D) powerfully confirms that protection from neuronal death during ischemia can proceed independently from reduction of vascular disruption.

3.4. Limitations.

Important limitations of our work should be noted. Considerable species differences affect clotting and the functions of APC, thrombin, and the receptors they interact with. Ideally animal studies would be conducted using homologous recombinant proteases, i.e., recombinant mutants of rat thrombin and APC in rats, but this was not feasible; moreover, the most meaningful results will come from confirmation in patients receiving recombinant human APCs. There may be other receptors activated by APC that are potential contributors to signalling via cross-talk or amplification of the primary APC effect on PAR1 and PAR3 (Cao et al., 2010; Minhas et al., 2010; Sinha et al., 2016). Given the sample sizes we used, there is a possibility of missing smaller treatment effects. Although this study was conducted in accordance with most commonly accepted guidelines for good laboratory practice—including blinding, randomization, and scrupulous accounting of all subjects—no power analysis was conducted prior to beginning, again raising the possibility of a Type II error.

This study was intended only to demonstrate a proof of concept, not to explore the mechanisms of action of these drugs. For demonstrating vascular damage, we chose a method that demarcates areas of profound vascular damage(Chen et al., 2009). Leakage of very large dextrans (2MDa in this case) occurs only in regions of irreversible cell damage (see Figure 5, Chen et al, 2009)(Chen et al., 2009). Other BBB leakage markers would detect more subtle injuries, including loosening of tight junctions and increased pinocytosis(Cipolla et al., 2004). Thus, our data demonstrate a differential protective effect on neurons versus vasculature subject to fatal injury. As a proof-of-concept study, we used a variety of infusion schedules to illustrate drug effects during or after ischemia, as well as a variety of reperfusion times (30 min or 24 h) to explore both immediate and subacute injuries. Further studies will capture detailed descriptions of all these effects at early and late time points comprehensively.

3.5. Conclusions

Protease/PAR mediated neuroprotection is distinct from protease/PAR mediated vasculoprotective effects. Protease-mediated neuronal injury may proceed independently of vascular damage: agents that protect the BBB after thrombolysis might reduce vascular damage (and potentially hemorrhage), while other agents might specifically target neuronal protection and augment the benefits of thrombolysis or thrombectomy. Whether a given protease causes protection or toxicity also depends on dose and time of administration so dose-selection and timing for human stroke trials must proceed very thoughtfully.

4.0. Experimental Procedure

4.1. Reagents and antibodies:

Murine wild type and recombinant mutant activated protein C (WT-APC, 3K3A-APC and 5A-APC) were prepared essentially as published(Mosnier et al., 2007). The GpIIb/IIIa inhibitor GR144053 was purchased from Tocris Bioscience, Cat#1263. Mutant thrombin (W215A/E217A; WE thrombin) was kindly provided by Dr. Enrico Di Cera from St. Louis University(Cantwell and Di Cera, 2000). All other scientific grade reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

4.2. Experimental animals:

All methods used have been published and used extensively in our laboratory(Van Winkle et al., 2013). Male Sprague Dawley rats weighing 290–310g (young adult) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories. Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center approved all animal handling and surgery protocols. All treatments were assigned at random: after each animal was undergoing unilateral middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAo), the surgeon telephoned an off-site assistant and received a treatment code. The assistant then recorded the treatment assignment and the surgeon administered the treatment. All assessments—histological or behavioral—were performed by other investigators blinded to treatment group, as per CAMARADES and ARRIVE guidelines(Macleod et al., 2009). Only after all statistics were completed and all data verified was the treatment grouping revealed.

We occluded the left MCA for 2 h or 4 h using our method as described previously(Chen et al., 2012; Van Winkle et al., 2013). In brief, animals were anesthetized with 4% isoflurane induction and maintained on 1.5–2% isoflurane mixed in oxygen and nitrous oxide (30:70) and received tail-vein injections of 0.3 ml FITC-conjugated 2 MDa dextran in PBS at onset of surgery. A midline neck incision was made exposing the left common carotid artery. The external carotid was ligated with 4–0 silk suture and an incision was made in the wall of the external carotid artery close to the bifurcation point of the external and internal carotid arteries. A 4–0 heat-blunted nylon suture (Ethicon) was used for blocking the middle cerebral artery and inserted and advanced 17.5mm from the bifurcation point into the internal carotid arteries for 2 h or 4 h. After the occlusion, the nylon suture was removed from the carotid artery to allow reperfusion of blood flow into the MCA. To confirm adequate injury, neurological function was quantified by a blinded rater during reperfusion using rodent neurological grading system(Bederson et al., 1986).

4.3. Treatment schedules:

All reagents were suspended in 200 μL normal saline for intravenous infusion over 5 min unless otherwise specified. 1) To assess the effect of anti-thrombotic therapy independently of thrombin, we infused the GpIIb/IIIa inhibitor GR144053 (2 mg/kg) or saline, randomly assigned, via the jugular vein at the start of 2 h MCAo (n=5 per group). These animals were sacrificed 30 min after reperfusion and assessed for vascular damage (FITC-dextran) and neuronal degeneration (Fluoro-Jade). 2) To assess the impact of thrombin/PAR-1 modulation during ischemia, animals (n=10 per group) were randomized to either 2 h or 4 h MCAo and again randomized to saline, WT-APC or 5A-APC, both at 0.2mg/kg, via jugular vein as a 50% bolus at the beginning of MCAo and the remaining 50 % infused 2 h later (Fig. 2A). These animals were sacrificed 30 min after reperfusion and assessed for vascular damage (FITC-dextran) and neuronal degeneration (Fluoro-Jade). 3) To assess thrombin/PAR-1 modulation after ischemia, animals (n=11 per group) underwent 2 h MCAo and were then randomized to saline, WT-APC, 3K3A-APC or 5A-APC (0.2 mg/kg-low dose or 0.4 mg/kg-high dose). These drugs were given intravenously at the time of reperfusion (Fig. 3A). Brains were removed for imaging 24 h later and assessed for vascular damage (FITC-dextran) and neuronal degeneration (Fluoro-Jade). 4) To further assess thrombin/PAR-1 modulation after ischemia using a different approach, animals (2 h or 4 h MCAo, n=11 per group) randomly received saline, WE thrombin (8 μg/kg-Low dose or 16 μg/kg-High dose) via carotid artery infusion over 45 minutes (Fig. 4A). Brains were removed 24 h later for assessment for vascular damage (FITC-dextran) and neuronal degeneration (Fluoro-Jade). 5) To assess the effect of WT-APC, 5A-APC, and WE thrombin on coagulation, 1.5ml blood was drawn for automated prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) (Stago STA-R Evolution Coagulation Analyzer) 30 min after infusion of one of the agents from additional animals (n=4–5 per group) who were not subjected to MCAo. To assess the effect of GR144053 on coagulation, manual bleeding time(Garcia-Manzano et al., 2001) was measured using a template forepaw incision and filter paper; the total volume of blood removed during the bleeding time was estimated by pre- and post-bleeding weights of the filter paper(Berny-Lang et al., 2011).

4.4. FITC and Fluoro-Jade C analysis:

Vascular damage and cellular injury in 50 μm (freezing microtome) brain sections were imaged at low power using epifluorescence microscopy with a highly sensitive CCD camera (Apogee, Alta U32) using our validated methods. The area (in μm2) of FITC-dextran extravasation was quantified using Image-Pro Plus (Media Cybernetics) as described previously(Chen et al., 2009). An operator blind to the subject’s group outlined the ipsilateral striatum and applied semiautomatic thresholding and segmentation to measure the total area of fluorescence on 4 sections within the striatum per animal. Areal measurements were averaged. For quantification of Fluoro-Jade C positive neurons, an operator blinded to the treatment groups used NIH Image J software(Rajput et al., 2014) to convert each captured image to 8-bit format and the pseudo flat field to standardize the fluorescence signal in all sections. The nucleus counter particle analysis plugin was used to count the number of neurons from each brain section automatically. From 3–4 sections per animal, the numbers of positive neurons were averaged over 4 high power fields per section and reported per mm2.

4.5. Statistics:

All data are presented as mean±SE. For cell counting, data are presented as number of neurons/mm2 that stained positive for Fluoro-Jade C; vascular leakage data are presented as areas containing FITC fluorescence in μm2. Area measurements (vascular damage) and number of Fluoro-Jade C positive neurons were compared using 1-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison post-hoc test. R version 3.2.5 or GraphPad Prism 7.0 (San Diego, CA) were used to perform all the statistical analysis.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Protease/PAR neuroprotection is distinct from vasculoprotection.

Whether a protease causes protection or toxicity depends partly on dose and timing

Protease/PAR mediated cytoprotection occurs independently of anticoagulation

Dose-selection and timing for human stroke trials must proceed thoughtfully

Acknowledgements

Supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke R01 NS075930 (PL) and by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute RO1HL142975 (JG).

Mutant thrombin (W215A/E217A; WE thrombin) was kindly provided by Dr. Enrico Di Cera from St. Louis University.

Abbreviations:

- aPTT

activated partial thromboplastin time

- APC

activated protein C

- ANOVA

analysis of Variance

- BBB

blood brain barrier

- CCD

charge coupled device

- EPCR

endothelial protein C receptor

- FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate

- h

hours

- m

minutes

- MDa

mega Dalton

- MCAo

middle cerebral artery occlusion

- NIH

National Institutes of Health

- NVU

neurovascular unit

- PBS

phosphate buffered saline

- PARs

protease-activated receptors

- PT

prothrombin time

- WE

W215A/E217A

- WT

wild type

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures/Conflict of Interest

JG serves as a consultant to ZZ Biotech. PL is the Principal Investigator of the RHAPSODY trial, NCT 02222714, funded by NIH U01NS088312 to study 3K3A-APC in acute ischemic stroke. Scripps Research Institute shares in ownership of the rights to 3K3A-APC and 5A-APC. All other authors have no conflicts to disclose

Supplementary Information

A supplementary figure is available on the Journal website

References

- Adams HP, Bendixen BH, Leira E, Chang KC, Davis PH, Woolson RF, Clarke WR, Hansen MD, 1999. Antithrombotic treatment of ischemic stroke among patients with occlusion or severe stenosis of the internal carotid artery: A report of the Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) Neurology. 53, 122–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams HP Jr., Effron MB, Torner J, Davalos A, Frayne J, Teal P, Leclerc J, Oemar B, Padgett L, Barnathan ES, Hacke W, 2008. Emergency administration of abciximab for treatment of patients with acute ischemic stroke: results of an international phase III trial: Abciximab in Emergency Treatment of Stroke Trial (AbESTT-II). Stroke. 39, 87–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J, Lyden PD, 2015. Revisiting cerebral postischemic reperfusion injury: new insights in understanding reperfusion failure, hemorrhage, and edema. Int J Stroke. 10, 143–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bath PM, Iddenden R, Bath FJ, 2000. Low-molecular-weight heparins and heparinoids in acute ischemic stroke : a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Stroke. 31, 1770–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bederson JB, Pitts LH, Tsuji M, Nishimura MC, Davis RL, Bartkowski H, 1986. Rat Middle Cerebral-Artery Occlusion - Evaluation of the Model and Development of A Neurologic Examination. Stroke. 17, 472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berny-Lang MA, Hurst S, Tucker EI, Pelc LA, Wang RK, Hurn PD, Di Cera E, McCarty OJ, Gruber A, 2011. Thrombin mutant W215A/E217A treatment improves neurological outcome and reduces cerebral infarct size in a mouse model of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 42, 1736–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantwell AM, Di Cera E, 2000. Rational design of a potent anticoagulant thrombin. J Biol Chem. 275, 39827–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao C, Gao Y, Li Y, Antalis TM, Castellino FJ, Zhang L, 2010. The efficacy of activated protein C in murine endotoxemia is dependent on integrin CD11b. J Clin Invest. 120, 1971–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Friedman B, Cheng Q, Tsai P, Schim E, Kleinfeld D, Lyden PD, 2009. Severe blood-brain barrier disruption and surrounding tissue injury. Stroke. 40, e666–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Cheng Q, Yang K, Lyden PD, 2010. Thrombin mediates severe neurovascular injury during ischemia. Stroke. 41, 2348–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Friedman B, Whitney MA, Winkle JA, Lei IF, Olson ES, Cheng Q, Pereira B, Zhao L, Tsien RY, Lyden PD, 2012. Thrombin activity associated with neuronal damage during acute focal ischemia. J Neurosci. 32, 7622–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng T, Petraglia AL, Li Z, Thiyagarajan M, Zhong Z, Wu Z, Liu D, Maggirwar SB, Deane R, Fernandez JA, LaRue B, Griffin JH, Chopp M, Zlokovic BV, 2006. Activated protein C inhibits tissue plasminogen activator-induced brain hemorrhage. Nat Med. 12, 1278–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cipolla MJ, Crete R, Vitullo L, Rix RD, 2004. Transcellular transport as a mechanism of blood-brain barrier disruption during stroke. Front Biosci. 9, 777–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SR, 1999. How the protease thrombin talks to cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 96, 11023–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin SR, 2000. Thrombin signalling and protease-activated receptors. Nature. 407, 258–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- del Zoppo GJ, 2010. The neurovascular unit in the setting of stroke. J Intern Med. 267, 156–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dirnagl U, 2012. Pathobiology of injury after stroke: the neurovascular unit and beyond. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1268, 21–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feistritzer C, Schuepbach RA, Mosnier LO, Bush LA, Di Cera E, Griffin JH, Riewald M, 2006. Protective signaling by activated protein C is mechanistically linked to protein C activation on endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 281, 20077–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Manzano A, Gonzalez-Llaven J, Lemini C, Rubio-Poo C, 2001. Standardization of rat blood clotting tests with reagents used for humans. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 44, 153–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia PS, Ciavatta VT, Fidler JA, Woodbury A, Levy JH, Tyor WR, 2015. Concentration-dependent dual role of thrombin in protection of cultured rat cortical neurons. Neurochem Res. 40, 2220–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorbacheva L, Davidova O, Sokolova E, Ishiwata S, Pinelis V, Strukova S, Reiser G, 2009. Endothelial protein C receptor is expressed in rat cortical and hippocampal neurons and is necessary for protective effect of activated protein C at glutamate excitotoxicity. J Neurochem. 111, 967–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JH, Zlokovic BV, Mosnier LO, 2012. Protein C anticoagulant and cytoprotective pathways. Int J Hematol. 95, 333–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JH, Fernandez JA, Lyden PD, Zlokovic BV, 2016a. Activated protein C promotes neuroprotection: mechanisms and translation to the clinic. Thromb Res. 141 Suppl 2, S62–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin JH, Mosnier LO, Fernandez JA, Zlokovic BV, 2016b. 2016 Scientific Sessions Sol Sherry Distinguished Lecturer in Thrombosis: Thrombotic Stroke: Neuroprotective Therapy by Recombinant-Activated Protein C. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 36, 2143–2151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Liu D, Gelbard H, Cheng T, Insalaco R, Fernandez JA, Griffin JH, Zlokovic BV, 2004. Activated protein C prevents neuronal apoptosis via protease activated receptors 1 and 3. Neuron. 41, 563–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo H, Singh I, Wang Y, Deane R, Barrett T, Fernandez JA, Chow N, Griffin JH, Zlokovic BV, 2009. Neuroprotective activities of activated protein C mutant with reduced anticoagulant activity. Eur J Neurosci. 29, 1119–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Guo H, Zhao Z, Yang Q, Wang M, Bell RD, Wang S, Chow N, Davis TP, Griffin JH, Goldman SA, Zlokovic BV, 2013. An activated protein C analog stimulates neuronal production by human neural progenitor cells via a PAR1-PAR3-S1PR1-Akt pathway. J Neurosci. 33, 6181–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junge CE, Lee CJ, Hubbard KB, Zhang Z, Olson JJ, Hepler JR, Brat DJ, Traynelis SF, 2004. Protease-activated receptor-1 in human brain: localization and functional expression in astrocytes. Exp Neurol. 188, 94–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krenzlin H, Lorenz V, Danckwardt S, Kempski O, Alessandri B, 2016. The importance of thrombin in cerebral injury and disease. Int J Mol Sci. 17, 84–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SR, Wang X, Tsuji K, Lo EH, 2004. Extracellular proteolytic pathophysiology in the neurovascular unit after stroke. Neurol Res. 26, 854–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Cheng T, Guo H, Fernandez JA, Griffin JH, Song X, Zlokovic BV, 2004. Tissue plasminogen activator neurovascular toxicity is controlled by activated protein C. Nat Med. 10, 1379–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyden P, Levy H, Weymer S, Pryor K, Kramer W, Griffin JH, Davis TP, Zlokovic B, 2013. Phase 1 safety, tolerability and pharmacokinetics of 3K3A-APC in healthy adult volunteers. Curr Pharm Des. 19, 7479–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyden P, Pereira B, Chen B, Zhao L, Lamb J, Lei IF, Rajput P, 2014. Direct thrombin inhibitor argatroban reduces stroke damage in 2 different models. Stroke. 45, 896–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyden P, Weymer S, Coffey C, Cudkowicz M, Berg S, O’Brien S, Fisher M, Haley EC, Khatri P, Saver J, Levine S, Levy H, Rymer M, Wechsler L, Jadhav A, McNeil E, Waddy S, Pryor K, 2016. Selecting patients for intra-arterial therapy in the context of a clinical trial for neuroprotection. Stroke. 47, 2979–2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macleod MR, Fisher M, O’Collins V, Sena ES, Dirnagl U, Bath PM, Buchan A, van der Worp HB, Traystman RJ, Minematsu K, Donnan GA, Howells DW, 2009. Reprint: Good laboratory practice: preventing introduction of bias at the bench. Int J Stroke. 4, 3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino F, Pelc LA, Vogt A, Gandhi PS, Di Cera E, 2010. Engineering thrombin for selective specificity toward protein C and PAR1. J Biol Chem. 285, 19145–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minhas N, Xue M, Fukudome K, Jackson CJ, 2010. Activated protein C utilizes the angiopoietin/Tie2 axis to promote endothelial barrier function. FASEB J. 24, 873–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosnier LO, Yang XV, Griffin JH, 2007. Activated protein C mutant with minimal anticoagulant activity, normal cytoprotective activity, and preservation of thrombin activable fibrinolysis inhibitor-dependent cytoprotective functions. J Biol Chem. 282, 33022–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosnier LO, Zampolli A, Kerschen EJ, Schuepbach RA, Banerjee Y, Fernandez JA, Yang XV, Riewald M, Weiler H, Ruggeri ZM, Griffin JH, 2009. Hyperantithrombotic, noncytoprotective Glu149Ala-activated protein C mutant. Blood. 113, 5970–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosnier LO, Sinha RK, Burnier L, Bouwens EA, Griffin JH, 2012. Biased agonism of protease-activated receptor 1 by activated protein C caused by noncanonical cleavage at Arg46. Blood. 120, 5237–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajput PS, Lyden PD, Chen B, Lamb JA, Pereira B, Lamb A, Zhao L, Lei IF, Bai J, 2014. Protease activated receptor-1 mediates cytotoxicity during ischemia using in vivo and in vitro models. Neuroscience. 281C, 229–240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riewald M, Petrovan RJ, Donner A, Mueller BM, Ruf W, 2002. Activation of endothelial cell protease activated receptor 1 by the protein C pathway. Science. 296, 1880–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha RK, Yang XV, Fernandez JA, Xu X, Mosnier LO, Griffin JH, 2016. Apolipoprotein E receptor 2 mediates activated protein C-induced endothelial Akt activation and endothelial barrier stabilization. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 36, 518–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha RK, Wang Y, Zhao Z, Xu X, Burnier L, Gupta N, Fernandez JA, Martin G, Kupriyanov S, Mosnier LO, Zlokovic BV, Griffin JH, 2018. PAR1 Biased Signaling is Required for Activated Protein C In Vivo Benefits in Sepsis and Stroke. Blood. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney AM, Fleming KE, McCauley JP, Rodriguez MF, Martin ET, Sousa AA, Leapman RD, Scimemi A, 2017. PAR1 activation induces rapid changes in glutamate uptake and astrocyte morphology. Sci Rep. 7, 43606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Winkle JA, Chen B, Lei IF, Pereira B, Rajput PS, Lyden PD, 2013. Concurrent middle cerebral artery occlusion and intra-arterial drug infusion via ipsilateral common carotid artery catheter in the rat. J Neurosci Methods. 213, 63–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhang Z, Chow N, Davis TP, Griffin JH, Chopp M, Zlokovic BV, 2012. An activated protein C analog with reduced anticoagulant activity extends the therapeutic window of tissue plasminogen activator for ischemic stroke in rodents. Stroke. 43, 2444–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Sinha RK, Mosnier LO, Griffin JH, Zlokovic BV, 2013a. Neurotoxicity of the anticoagulant-selective E149A-activated protein C variant after focal ischemic stroke in mice. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 51, 104–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhao Z, Chow N, Rajput PS, Griffin JH, Lyden PD, Zlokovic BV, 2013b. Activated protein C analog protects from ischemic stroke and extends the therapeutic window of tissue-type plasminogen activator in aged female mice and hypertensive rats. Stroke. 44, 3529–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Zhao Z, Rege SV, Wang M, Si G, Zhou Y, Wang S, Griffin JH, Goldman SA, Zlokovic BV, 2016. 3K3A-activated protein C stimulates postischemic neuronal repair by human neural stem cells in mice. Nat Med. 22, 1050–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokovic BV GJ, 2011. Cytoprotective protein C pathways and implications for stroke and neurological disorders. Trends Neurosci. 34, 198–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.