Abstract

Objectives

The aim was to assess coronary atherosclerosis, plaque morphology and associations to cardiovascular risk factors and epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) in patients with long duration of type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM).

Materials and methods

Eighty-eight patients with ≥ 45 year T1DM duration and 60 controls underwent coronary CT angiography (CCTA) for evaluation of coronary artery plaque volume (total, calcified or mixed/soft), coronary artery calcification score (CAC) and EAT.

Results

Plaques were detected in 75 (85%) T1DM patients and 28 (47%) controls, p < 0.01. Median (interquartile range) plaque volume (mm3) in T1DM vs. controls was: 21.0 (1.0–66.0) vs. 0.2 (0.0–7.1), p < 0.01 for calcified, 0.0 (0.0–8.7) vs. 0.0 (0.0–0.0), p < 0.01 for soft/mixed and 29.5 (3.9–95.8) vs. 0.4 (0.0–7.4), p < 0.01 for total plaque volume. Median CAC was 128 (13–671) vs. 1 (0.0–39.0), p < 0.01 in T1DM vs. controls. Median EAT volume did not differ between the groups; 52.3 (36.1–65.5) cm3 vs. 55 (38.3–79.6), p = 0.20. No association between CAC or plaque volumes and EAT were observed. Low time-weighted LDL-cholesterol and HbA1c for 30 years were associated with having plaque volume < 25th percentile, OR (95% CI) 0.18 (0.05–0.70), p = 0.01 and 0.45 (0.20–1.00), p < 0.05, respectively. Time-weighted LDL-c was linearly associated with CAC (beta 0.82 (95% CI 0.03–1.62), p = 0.04) and total plaque volume (beta 0.77 (95% CI 0.19–1.36), p = 0.01).

Conclusion

Long-term survivors of T1DM have a higher prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis compared to controls. Low LDL-cholesterol and HbA1c over time have a protective effect on coronary atherosclerosis. EAT volume was not associated with coronary atherosclerosis in T1DM patients.

Keywords: Diabetes type 1, Atherosclerosis, Epicardial adipose tissue, Computed tomography

Introduction

Patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) have an increased risk of cardiac events, and coronary atherosclerosis increases the risk substantially [1]. Assessment of plaque morphology is important since non-calcified plaques are more likely to result in acute coronary syndrome than the more stable calcified plaques [2]. Plaque morphology has been shown to predict coronary events in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) [3]. Due to different pathogenesis between T1DM and T2DM, similar studies should also be conducted in patients with T1DM. Furthermore, epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) has gained increased interest due to reported associations with coronary atherosclerosis [4], and suggested linked to inflammation and early development of atherosclerosis [5].

Coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) has evolved as a non-invasive imaging technique for evaluation of stenoses in the coronary arteries, but it is also widely used in quantitative plaque assessments [6]. Evaluation of EAT volumes can also be performed on the same images [7]. Unenhanced coronary artery calcification (CAC) score has a prognostic value for cardiac events in asymptomatic individuals [8], but additional contrast-enhanced CCTA has shown to improve the risk-stratification in asymptomatic patients with both T1DM and T2DM [9].

We have previously reported on a higher prevalence of undiagnosed coronary heart disease among patients with a very long duration of T1DM compared to sex- and age-matched controls [10]. However, there is limited evidence on the morphology, extent and severity of the coronary plaques in T1DM patients versus persons without diabetes [11]. In the present study we have included a population of patients with a long duration of T1DM (> 45 years) in order to identify factors associated with coronary atherosclerosis in a group of long-term survivors. This information may widen the understanding of the possible impact of long-term glycemic control on the morphology of coronary atherosclerosis, and the improved understanding of survival may be important in the management of these patients. Furthermore, a lack of association between CAC and EAT has earlier been reported in T1DM patients [12]. Due to diverse evidence regarding EAT [13], there is a need for complementary evaluation of possible associations with the atherosclerotic characteristics.

The aims of the present study were therefore to (i) assess the morphological characteristics of coronary atherosclerosis by CCTA, (ii) to evaluate the associations between CCTA variables with risk factors for coronary atherosclerosis and (iii) to evaluate differences in epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) volumes and associations with coronary atherosclerosis in patients with long-term T1DM compared to controls.

Materials and methods

Patients and study design

The cross-sectional Dialong study of long-term survivors of T1DM was conducted in 2015/2016. As previously described, a chart review of the diabetes participants from the previous 2–4 decades was performed, resulting in long-term longitudinal weighted variables of glycated hemoglobin (wHbA1c), low density lipoprotein cholesterol (wLDL-c) and systolic blood pressure (wSBP) [10]. These measurements were available from 1980, and were calculated as previously described [10, 14]. All the patients with T1DM diagnosed ≤ 1970 attending a state-funded specialised T1DM clinic; the Norwegian Diabetics’ Centre (NDC) in Oslo, Norway were invited. Hundred-and-three patients joined the coronary artery disease substudy. Participants without earlier diagnosed coronary heart disease and eGFR > 45 were referred to CCTA, resulting in 88 participants with T1DM for ≥ 45 years completing the CCTA. The sex and age matched control group undergoing CCTA (n = 60) consisted of healthy, invited spouses/friends of the participants with T1DM. The regional ethics committee approved the study (project no. 2014/851) and all participants signed an informed consent.

Image acquisition

All examinations were performed on a 128-slice Dual Source Somatom Definition FLASH CT-scanner (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). An unenhanced scan was conducted for the evaluation of coronary artery calcification (CAC). If tolerated, beta blockage (5–20 mg metoprolol, Seloken®, Astra Zeneca) was used to reduce the heart rhythm and Nitroglycerin 0.4 mg (Nitrolingual®, Pohl-Boskamp, Hohenlockstedt, Germany) was administered sublingually. The scan protocol for the CCTA was chosen in concordance with the achieved heart rate as previously described [10]. The contrast media Omnipaque™ 350 mg/mL (GE Healthcare, Princeton, New Jersey) was used for all examinations.

Image analyses

Image analyses were performed on a Philips Workstation (Intellispace v5, Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, Ohio, USA) with dedicated software (Comprehensive Cardiac, Plaque Analysis, Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, Ohio, USA). Images were assessed using a modified 17-segment American Heart Association model [15]. All segments with a diameter > 1.5 mm and subjectively sufficient image quality were included in the analyses. CAD was defined as presence of any plaque. CAC was calculated with the Agatston method [16]. The plaque volume (mm3) was calculated for each plaque differentiated on plaque morphology. Plaques were categorized as calcified when ≥ 90% and soft when ≤ 10% of the volume had a density of > 130 Hounsfield units (HU). All other plaques were defined as mixed plaques [17]. The total plaque volume, total calcified volume and total mixed/soft plaque volume were calculated for each patient. The soft and mixed plaque volume was calculated together for statistical purposes due to small amounts of soft plaques.

The extent and severity of CAD was assessed by the segment involvement score (SIS) and the segment stenosis score (SSS). SIS was calculated for assessment of extent as the number of segments with plaque involvement (range 1–17). SSS was calculated for assessment of the severity of the stenosis. Each segment was scored (grading 1–4) according to the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography’s recommended stenosis grading, based on luminal narrowing; Grade 1: 1–29% stenosis; Grade 2: 30–49% stenosis; Grade 3: 50–69% stenosis and Grade 4: 70–100% stenosis, with a total possible SSS of 0–68 [18].

EAT was evaluated from the unenhanced CT images using SliceOmatic5.0 (TomoVision, Magog, Canada). All tissue with a density between − 190 and − 30 Hounsfield units’ values within the pericardial sac was defined as EAT. All 2.5 mm axial slices were assessed, with the upper limit starting at the right coronary artery and bottom limit at the apex of the heart. Two independent readers analyzed a 30% random selection of the T1DM examinations, and similar for evaluation of intrarater variability.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive data are presented with numbers (%) for dichotomized variables and mean ± SD for normally distributed characteristics or median, interquartile range (IQR) if not normally distributed. Independent samples t-test or X2 was used to compare variables among groups. Non-normally distributed variables were log-transformed before conducting the analyses.

Correlation between CCTA measurements and clinical variables was assessed by Spearman’s rho. Linear regression was used to adjust for confounders. Variables with not normally distributed residuals were natural log (ln)-transformed. To solve problem of zero values we added one to each measure before transformation (log (X + 1)). Variables with a correlation of ≥ 0.2 or of special clinical relevance were included in the model, and a backwards approach was chosen. Tested variables included: age, sex, family history of coronary heart disease, smoking, hyperlipidemia, use of statins, retinopathy, persistent albuminuria, angina, waist circumference, systolic BP, diastolic BP, pulse pressure, wHba1c, wLDL-c, HDL-c, triglycerides, SR, CRP, troponins and proBNP. Models were checked by plots of residuals vs. predicted values. The 25th percentile of the total plaque volume was evaluated in a logistic regression analysis for the assessment of associations to a low plaque burden. All regression analyses were performed separately of the T1DM group and the controls due to lack of longitudinal variables in the control group. Inter-and intrarater variability were determined by the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC). All statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.

Results

Table 1 shows the clinical characteristics which partly have been published [10]. Briefly, age and sex were comparable between the groups. The T1DM-patients had higher heart rates, systolic blood pressure, pro-BNP, HDL-c, lower LDL-c and a higher use of statins compared with controls. Other traditional risk factors such as hyperlipidemia and smoking were equally distributed between the groups.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| T1DM-patients (n = 88) |

Controls (n = 60) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 61.3 ± 7.1 | 62.3 ± 6.8 | 0.38 |

| Female, n% | 47 (53.4) | 34 (56.7) | 0.70 |

| Body mass index (kg/m3) | 25.8 ± 3.9 | 25.5 ± 4.2 | 0.69 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 90.3 ± 13.2 | 89.1 ± 12.2 | 0.55 |

| Previous CVD, n% | 6 (6.8) | 2 (3.3) | 0.36 |

| Angina, typical | 2 (2.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.49 |

| Angina, atypical | 21 (24.1) | 14 (23.3) | |

| No angina | 64 (73.6) | 46 (76.7) | |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 146 ± 19.8 | 137 ± 19.3 | < 0.01 |

| wSystolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 130 ± 10.6 | ||

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 75.3 ± 8.4 | 81.7 ± 9.7 | < 0.01 |

| Pulse pressure | 71.6 ± 16.1 | 55.0 ± 14.1 | < 0.01 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 68 ± 10.3 | 62 ± 9.3 | < 0.01 |

| Hypertensiona, n% | 23 (26.4) | 11 (18.3) | 0.25 |

| Hyperlipidemiab, n% | 27 (31.0) | 12 (20.0) | 0.17 |

| Family history of CVD, n% | 10 (11.5) | 13 (21.7) | 0.05 |

| Daily smokers, n% | 5 (5.7) | 6 (10) | 0.62 |

| Ex-smokers, n% | 34 (38.6) | 22 (36.7) | |

| pro-BNP (ng/L) | 104.9 ± 110.1 | 67.4 ± 51.3 | < 0.01 |

| eGFR | 85 ± 19.2 | 82 ± 12.8 | 0.18 |

| Statin use, n% | 40 (45.5) | 6 (10.0) | < 0.01 |

| HDL-c (mmol/L) | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 1.8 ± 0.5 | < 0.01 |

| Statin years | 2.8 ± 4.3 | ||

| LDL-c (mmol/L) | 2.8 ± 0.8 | 3.9 ± 1.0 | < 0.01 |

| wLDL-c (mmol/L) | 2.9 ± 0.6 | ||

| Triglycerides (mmol/L), median (IQR) | 0.77 (0.39–2.85) | 0.93 (0.52–2.96) | < 0.01 |

| HbA1c (mmol/mol) | 7.4 ± 0.81 | 5.4 ± 0.28 | < 0.01 |

| wHbA1c (mmol/mol) | 7.9 ± 0.83 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD unless otherwise stated

T1DM type 1 diabetes mellitus, CVD cardiovascular disease, NT-proBNP N terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, HDL-c high density lipoprotein-cholesterol, LDL-c low density lipoprotein cholesterol, wLDL-c weighted low density lipoprotein cholesterol, HbA1c glycated hemoglobin, wHbA1c weighted glycated hemoglobin

* Independent samples t-test

aHypertension: previous documented hypertension in the chart or from relevant discharge letters, based on readings with sBP > 140 and/or dBP > 90

bHyperlipidemia: documented hyperlipidemia or a previous total cholesterol reading of > 6.2 or LDL > 4.9 mmol/L

All the CCTA-measurements were significantly higher in the T1DM-group compared to the controls, except mean EAT volume which did not differ between the groups (p = 0.20) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Coronary plaques, calcification and epicardial adipose tissue in T1DM patients and controls

| Type 1 diabetes (n = 88) |

Controls (n = 60) |

p-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Any plaque, n (%) | 75 (85) | 28 (47) | < 0.01 |

| CAC, Agatston units | 124 (13–671) | 1 (0–3) | < 0.01 |

| Calcified plaque volume (mm3) | 21.0 (1.0–66.0) | 0.2 (0.0–7.1) | < 0.01 |

| Mixed/soft plaque volume (mm3) | 0.0 (0.0–8.7) | 0.0 (0.0–0.0) | < 0.01 |

| Total plaque volume (mm3) | 29.5 (3.9–95.8) | 0.4 (0.0–7.4) | < 0.01 |

| Segment involvement score | 3 (1–6) | 1 (0–2) | 0.01a |

| Segment stenosis score | 4 (1–8) | 1 (0–3) | < 0.01a |

| Epicardial adipose tissue (cm3) | 52.3 (36.1–65.5) | 55 (38.3–79.6) | 0.20a |

| Mean EAT attenuation (HU) | − 73.0 (− 76.0 to − 68.8) | − 76 (− 79.4 to − 70.9) | 0.01a |

Presented as median (IQR) unless otherwise stated

CAC coronary artery calcification, SD standard deviation, SIS segment involvement score, SSS segment stenosis score, EAT epicardial adipose tissue, HU Hounsfield units

* Mann–Whitney-U test

aIndependent samples t-test

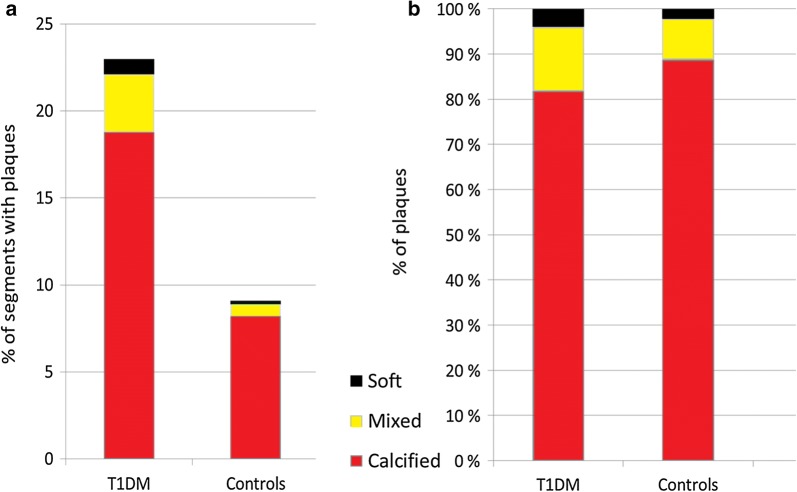

We detected 23% (324 out of 1408) segments with plaques in the T1DM group; 265 (82%) calcified, 46 (14%) mixed and 13 (4%) soft plaques. In the control group we detected 9.2% (88 out of 960) segments with plaques; 79 (90%) calcified, 7 (8%) mixed and 2 (2%) soft. The distribution of the plaque types are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

a The number of plaques between T1DM and controls. In the T1DM-group, plaques were detected in 23% (324 out of 1408) of the segments, compared to 9.2% (88 out of 960) in the control group (p < 0.01). b The distribution of plaque types between T1DM and controls: calcified; 82% vs. 90%, mixed; 14% vs. 8% and soft; 4% vs. 2%, respectively

In a linear multivariable regression analysis with total plaque volume as dependent variable (Table 3), wLDL-c was the only associated variable after adjusting for sex and age with beta (95% CI) 0.77 (0.19–1.36), p = 0.01.

Table 3.

Associations between total plaque volume and risk factors for CAD in the diabetes group

| Univariable | Multivariable | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | p-value | β (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age | 0.06 (0.00–0.19) | 0.05 | 0.09 (0.00–0.14) | < 0.01 |

| Female sex | − 1.63 (− 2.34 to − 0.91) | < 0.01 | − 1.13 (− 1.83 to − 0.43) | < 0.01 |

| wLDL-c | 1.00 (0.35–1.64) | < 0.01 | 0.77 (0.19–1.36) | 0.01 |

| wHbA1c | 0.44 (− 0.04 to 0.92) | 0.07 | ||

| wSBP | 0.06 (0.02–0.09) | < 0.01 | ||

| Waist circumference | 0.03 (0.00–0.06) | 0.04 | ||

In a multivariable logistic regression analysis with the 25th percentile (n = 21) as dependent variable, the OR (95% CI) were; wLDL-c: 0.18 (0.05–0.70), p = 0.01, wHbA1c: 0.45 (0.20–1.00), p < 0.05, and HDL-c: 0.15 (0.04–0.65), p = 0.01 in an age and sex-adjusted model.

In a sex and age adjusted linear, multivariable regression analysis with log-transformed CAC as dependent variable associated variables were: wLDL-c (beta (95% CI) 0.87 (0.10–1.64), p = 0.03 and pro-BNP (beta (95% CI) 0.005 (0.001–0.010), p < 0.02). In the control group, the only significantly associated variables were female sex and age with beta: − 2.358 (− 3.305 to − 1.412), p < 0.01 and 0.113 (0.044–0.182), p < 0.01, respectively.

The CAC and calcified plaque volume correlated with r = 0.90, p < 0.01.

EAT volume

The inter- and intraobserver variability of EAT volume was evaluated with an ICC of 0.87 and 0.91, respectively.

No correlations between EAT and CCTA measurements were detected; CAC; r = − 0.04, p = 0.74, calcified plaque volume; r = 0.03, p = 0.77, mixed/soft plaque volume; r = 0.07, p = 0.54, total plaque volume; r = 0.07, p = 0.54 and SIS; r = 0.06, p = 0.59 and SSS; r = 0.08, p = 0.48.

Table 4 shows univariable and multivariable associations between EAT and risk factors for CAD. The only significant association found in the control group was between EAT and waist circumference.

Table 4.

Associations between epicardial adipose tissue and risk factors for CAD in the diabetes group

| Univariable | Age and sex-adjusteda | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β (95% CI) | p-value | β (95% CI) | p-value | β (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age | 0.20 (− 0.63 to 1.02) | 0.635 | 0.21 (− 0.62 to 1.03) | 0.614 | 0.9 (0.3–1.5) | 0.004 |

| Female sex | − 6.15 (− 17.63 to 5.33) | 0.290 | − 6.23 (− 17.77 to 5.30) | 0.286 | 19.4 (9.4–29.4) | 0.000 |

| HDL-c | − 16.06 (− 26.29 to − 5.83) | 0.002 | − 17.10 (− 28.31 to − 5.89) | 0.003 | − 9.3 (− 18.1 to − 0.5) | 0.038 |

| TG | 19.15 (4.97–33.32) | 0.009 | 12.80 (− 0.11 to 25.72) | 0.052 | − 14.6 (− 27.2 to − 2.0) | 0.024 |

| Waist circumference | 1.27 (0.93–1.61) | < 0.001 | 1.54 (0.97–2.11) | < 0.001 | 1.8 (1.3–2.3) | 0.000 |

| wHbA1c | 9.14 (2.52–15.77) | 0.007 | 9.12 (2.34–15.89) | 0.009 | ||

| wLDL-c | 7.68 (− 1.66 to 17.01) | 0.106 | ||||

| wSBP | 0.083 (− 0.46 to 0.63) | 0.763 | ||||

| Systolic BP | 0.18 (− 0.11 to 0.48) | 0.214 | ||||

| Diastolic BP | 0.24 (− 0.44 to 0.95) | 0.469 | ||||

| Pulse pressure | 0.21 (− 0.15 to 0.57) | 0.249 | ||||

HDL-c high density lipoprotein cholesterol, TG triglycerides, wHbA1c weighted glycated hemoglobin, wLDL-c weighted low density lipoprotein cholesterol, BP; blood pressure, wSBP weighted systolic blood pressure

aMinimally multivariable model (only adjusted for age and sex)

Discussion

In this study of patients who have survived more than 45 years with T1DM without a previous diagnosis of coronary heart disease, we found a greater extent and severity of coronary atherosclerosis compared to controls. Plaque volumes, segment involvement score, segment stenosis score and CAC were significantly greater in the T1DM group, but morphological assessments showed mostly calcified plaques (82%). Elevated LDL-c over time was associated with increased plaque volume and CAC. Low LDL-c level and HbA1 over time, in addition to present HDL-c level, was associated with having a more favorable plaque volume (below the 25th percentile ≤ 3.6 mm3). The EAT volume did not differ between T1DM and controls. We found no associations between coronary atherosclerosis and EAT volume.

Our study shows a large variation in magnitude of atherosclerotic extent. Interestingly, after more than 45 years of diabetes, 15% have no plaques. As previously reported, 11 (13%) patients were revascularized with PCI or CABG compared to 2 (5%) in the control group [10]. The CAC score also varied substantially between the individuals. We excluded patients with prior cardiac events or known coronary heart disease in order to explore the coronary artery status among asymptomatic long-term T1DM survivors. Therefore, the results are only representative to asymptomatic T1DM patients, without established coronary heart disease. The total burden and characteristic of coronary atherosclerosis in T1DM patient is probably different than in our selected patients, but our study was not designed to investigate it.

In our study, 82% of the plaques were calcified. Soft/mixed plaques have been shown in the MESA-study to be associated with worse outcomes than the more stable calcified plaques [19]. Shemesh et al. investigated the degree of CAC in relation to cardiac events in asymptomatic subjects with and without diabetes [20]. They found that acute events did not occur in subjects with extensive CAC (> 600), but were more likely to occur in subjects with mild or moderate CAC [20]. These results were comparable to findings in the MESA-study; subjects with high CAC (> 400) and very high CAC (> 1000) had equal risk for experiencing cardiac events [21]. Our findings may thereby confirm that calcified plaques represent more stable and long standing atherosclerosis. As shown in a study by Djaberi et al. there are morphologically large differences in plaques between T1DM and T2DM [11]. They found 27% non-calcified plaques in their T1DM-group compared to 65% in the T2DM group. Our participants have a more favorable plaque composition as only 18% of the plaques were defined as mixed/soft plaques. The CAC score in our study was also lower. The patients in the study of Djaberi et al. had shorter diabetes duration (mean of 23 years) compared to ≥ 45 years in our study. The inclusion of long-term survivors of T1DM in our study might explain the discrepancy. Other traditional risk factors were less frequent in our study, which might also contribute to their survival.

The DCCT/EDIC-study described mean HbA1c through 27 years as the strongest risk factor for cardiac events in addition to age in patients with T1DM [22]. In our study, chronic hyperglycemia based on high HbA1c measurements over more than 30 years was associated only with having a low amount of plaque volume (< 25th percentile), while wLDL-c was additionally linearly associated with CAC and total plaque volume. This discrepancy might be due to a higher median HbA1c and a lower median LDL-c level in the DCCT/EDIC-study compared to ours. Patients in the DCCT/ECIT-study were patients with a prior cardiac event, patients that were excluded in our study. The lower HbA1c in our participants may also be a contributing factor for their survival. However, the associations to having the lowest amount of plaque volume suggest that keeping both the LDL-c and HbA1c low over time may have a preventive effect on the development of coronary atherosclerosis. Also, similar plaque characteristics has been described for patients with and without diabetes with elevated HbA1c [23], adding evidence to a role for HbA1c in plaque development. Raised HbA1c is associated with a higher coronary atherosclerotic burden in patients without diabetes [24]. Therefore, we still believe that HbA1c, most likely, plays an important role in plaque development in T1DM-patients. Tinsley et al. also describes a 10 year survival dependent on glycemic control in T1DM patients with > 50 years duration, which further gives evidence to the importance of HbA1c in T1DM patients [25]. A comparison to T1DM patients with a previous cardiac event would be clarifying.

Reducing the LDL-c is the most effective prevention for atherosclerosis in the general population [26]. Statin-use has shown to affect plaque development, observed as cell-death within the lipid cores in addition to the induction of micro-calcifications [27, 28]. These effects are described as plaque-stabilizing, and an inverse linear relationship of plaque density and coronary events are described [29]. Initiation of lipid-lowering treatment is guideline-recommended after 40 years of age in patients with T2DM, but in T1DM statins is recommended only in the presence of microalbuminuria or renal disease [1]. Patients with both type 1 and 2 DM have been shown to be undertreated with statins [30]. In our study, 46% of the T1DM-group reported statin-use, but with a short duration of statin-treatment (2.8 ± 4.3 years). Several publications have shown that high-intensity treatment (LDL-c level target < 1.8 mmol/mL) is required to achieve plaque regression in patients with DM [31, 32]. A higher CAC score has been reported after initiation of statin-treatment due to the conversion in plaque composition [33]. From this one would expect statin-use to have increased the CAC-score in our T1DM group. However, the duration of statin-use is short and the statin-effect cannot be fully evaluated in this cross-sectional study. The low LDL-c-levels and variations in our cohort may be a result of statin-use and accordingly, the findings of non-significant associations to CAC and plaque volume may be explained by a type II error.

Associations between EAT and coronary atherosclerosis are reported by multiple studies [34], suggesting that EAT have a role in the development of coronary atherosclerosis. We did not observe a difference in EAT volume between T1DM-patients and controls, despite a significant difference in coronary atherosclerosis. To our knowledge, EAT has not previously been associated with coronary atherosclerosis in T1DM patients, although associations of coronary atherosclerosis and EAT in patients with T2DM has been revealed [35, 36]. The inconsistent findings between T1DM and T2DM may imply that EAT potentially plays a different role between the types of DM. In T2DM metabolic syndrome, not commonly present in T1DM, has been associated with increased EAT volumes [37]. We did however reveal a strong association between EAT and waist circumference, which implies that visceral fat and fat within the pericardial sac are related. This is consistent with Darabian et al. [12], who found associations of EAT with greater BMI and waist to hip ratio. EAT has been suggested as a new image marker for atherosclerosis, and a lack of association in some patient groups may be important in this discussion. We cannot exclude that the negative associations in our study are a result of a type II error, due to the low amount of mixed/soft plaques.

The influence of glycemic control on EAT volume is unexplored. We did not find associations between EAT and HbA1c. Darabian et al. reported on a significant association between EAT and HbA1c in an age- and sex adjusted statistical model [12]. However, in their study the participants were younger, had a shorter duration of T1DM and a higher BMI compared to our participants. Also, the statistical significance was no longer present after BMI-adjustment. This is similar to our finding, when including waist circumference in the statistical model, the association between EAT and HbA1c was no longer significant.

The use of CCTA in high-risk, asymptomatic patients is debated. Although the radiation hazard and the technical challenge in presence of large calcified plaques are diminished after introduction of newer generation scanners, there is a lack of evidence whether CCTA improves outcomes in asymptomatic patients with diabetes. Muhlestein et al. found no reduction in acute events in their randomized trial [38]. This was also found in the DIAD-study, were patients with T2DM were randomized to myocardial perfusion imaging or not [39]. The identification of patients in the need for further cardiac evaluation is difficult in the absence of symptoms, and other potential selection criteria are warranted. The large variation of presence and extent of coronary atherosclerosis in patients with a long duration of T1DM found in our study supports further evaluation of selection based on other predictors in order to select the right patients for CCTA.

Our study is limited by a small sample size and a cross-sectional design. The control group is also small, and consists of spouses and friends of the patients. Living with a person with diabetes may influence diet and lifestyle, and we cannot exclude that this has affected our results. However, our results are in line with the DanRisk-study of only healthy individuals [40]. The reproducibility of plaque volume is a limitation in CCTA. In our study, most of the plaques detected were calcified, and plaque assessments were performed with a software previously shown to have a high degree of inter-observer variability on calcified and mixed lesions [17]. CAC, however; is an established method with a high degree of reproducibility [41], and our plaque volume score correlated well with CAC.

Conclusion

In conclusion, patients with a long duration of T1DM have a more extensive and severe atherosclerotic condition, consisting mainly of calcified plaques compared to controls. Maintaining low LDL-c and HbA1c level over time may have a preventive effect on atherosclerotic plaque development, while long-time LDL-c seems to be important for the plaque acceleration in these patients. We found no associations between EAT and coronary atherosclerosis. Larger studies with longitudinal designs are warranted to evaluate the effect of extent and differences of plaque morphology on cardiovascular events in patients with T1DM.

Authors’ contributions

TJB and KBH designed the study and enrolled patients. All authors were responsible for the data acquisition; MS, YH and NEK were responsible for all the CCTA measurements and KBH and TJB for all the clinical variables. MS, KBH, YH, and TJB analyzed the data. MS wrote the first draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lena Korsmo Karterud (Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, Oslo University Hospital, Oslo, Norway) for performing EAT-analyses in regards of interobserver variability, Catrine Brunborg (University of Oslo, Center for biostatistics and epidemiology) for statistical assistance, and Anne Karin Molvær (Norwegian Diabetics’ Center) for clinical data collection. We are also grateful to all the study participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The data are available from the corresponding author on request.

Consent for publication

All participants provided written informed consent before enrollment in this study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Norwegian South-East regional ethics committee approved the study (Project No. 2014/851), and all participants signed an informed consent.

Funding

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- BP

blood pressure

- CAC

coronary artery calcifications

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CCTA

coronary computed tomography angiography

- CVD

cardiovascular disease

- EAT

epicardial adipose tissue

- eGFR

estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HbA1c

glycated hemoglobin

- HDL-c

high density lipoprotein-cholesterol

- HU

Hounsfield units

- LDL-c

low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- NT-proBNP

N terminal-pro B-type natriuretic peptide

- SD

standard deviation

- SIS

segment involvement score

- SSS

segment stenosis score

- T1DM

type 1 diabetes mellitus

- T2DM

type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TG

triglycerides

- wLDL-c

weighted low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- wHbA1c

weighted glycated hemoglobin

- wSBP

weighted systolic blood pressure

Contributor Information

Mona Svanteson, Email: monasvanteson@gmail.com.

Kristine Bech Holte, Email: k.b.holte@medisin.uio.no.

Ylva Haig, Email: haigylva@gmail.com.

Nils Einar Kløw, Email: n.e.klow@medisin.uio.no.

Tore Julsrud Berg, Email: t.j.berg@medisin.uio.no.

References

- 1.Catapano AL, Graham I, De Backer G, Wiklund O, Chapman MJ, Drexel H, et al. 2016 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. Eur Heart J. 2016;37:2999–3058. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motoyama S, Sarai M, Harigaya H, Anno H, Inoue K, Hara T, et al. Computed tomographic angiography characteristics of atherosclerotic plaques subsequently resulting in acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halon DA, Lavi I, Barnett-Griness O, Rubinshtein R, Zafrir B, Azencot M, et al. Plaque morphology as predictor of late plaque events in patients with asymptomatic type 2 diabetes: a long-term observational study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2018.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marwan M, Achenbach S. Quantification of epicardial fat by computed tomography: why, when and how? J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2013;7:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2013.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goeller M, Achenbach S, Marwan M, Doris MK, Cadet S, Commandeur F, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue density and volume are related to subclinical atherosclerosis, inflammation and major adverse cardiac events in asymptomatic subjects. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2018;12:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2017.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kolossvary M, Szilveszter B, Merkely B, Maurovich-Horvat P. Plaque imaging with CT—a comprehensive review on coronary CT angiography based risk assessment. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2017;7:489–506. doi: 10.21037/cdt.2016.11.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dey D, Nakazato R, Li D, Berman DS. Epicardial and thoracic fat—noninvasive measurement and clinical implications. Cardiovasc Diagn Ther. 2012;2:85–93. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2223-3652.2012.04.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaMonte MJ, FitzGerald SJ, Church TS, Barlow CE, Radford NB, Levine BD, et al. Coronary artery calcium score and coronary heart disease events in a large cohort of asymptomatic men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:421–429. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Min JK, Labounty TM, Gomez MJ, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, et al. Incremental prognostic value of coronary computed tomographic angiography over coronary artery calcium score for risk prediction of major adverse cardiac events in asymptomatic diabetic individuals. Atherosclerosis. 2014;232:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2013.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Holte KB, Svanteson M, Hanssen KF, Haig Y, Solheim S, Berg TJ. Undiagnosed coronary artery disease in long-term type 1 diabetes. The Dialong study. J Diabetes Complicat. 2019;33:383–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2019.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Djaberi R, Schuijf JD, Boersma E, Kroft LJ, Pereira AM, Romijn JA, et al. Differences in atherosclerotic plaque burden and morphology between type 1 and 2 diabetes as assessed by multislice computed tomography. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1507–1512. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darabian S, Backlund JY, Cleary PA, Sheidaee N, Bebu I, Lachin JM, et al. Significance of epicardial and intrathoracic adipose tissue volume among type 1 diabetes patients in the DCCT/EDIC: a pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0159958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tanami Y, Jinzaki M, Kishi S, Matheson M, Vavere AL, Rochitte CE, et al. Lack of association between epicardial fat volume and extent of coronary artery calcification, severity of coronary artery disease, or presence of myocardial perfusion abnormalities in a diverse, symptomatic patient population: results from the CORE320 multicenter study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:e002676. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.002676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holte KB, Juel NG, Brox JI, Hanssen KF, Fosmark DS, Sell DR, et al. Hand, shoulder and back stiffness in long-term type 1 diabetes; cross-sectional association with skin collagen advanced glycation end-products. The Dialong study. J Diabetes Complicat. 2017;31:1408–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2017.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini GG, Gott VL, Griffith LS, et al. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1975;51:5–40. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.51.4.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte JM, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klass O, Kleinhans S, Walker MJ, Olszewski M, Feuerlein S, Juchems M, et al. Coronary plaque imaging with 256-slice multidetector computed tomography: interobserver variability of volumetric lesion parameters with semiautomatic plaque analysis software. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;26:711–720. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9614-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raff GL, Chinnaiyan KM, Cury RC, Garcia MT, Hecht HS, Hollander JE, et al. SCCT guidelines on the use of coronary computed tomographic angiography for patients presenting with acute chest pain to the emergency department: a report of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2014;8:254–271. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Budoff MJ, Young R, Lopez VA, Kronmal RA, Nasir K, Blumenthal RS, et al. Progression of coronary calcium and incident coronary heart disease events: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1231–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shemesh J, Tenenbaum A, Fisman EZ, Koren-Morag N, Grossman E. Coronary calcium in patients with and without diabetes: first manifestation of acute or chronic coronary events is characterized by different calcification patterns. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2013;12:161. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-12-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coylewright M, Rice K, Budoff MJ, Blumenthal RS, Greenland P, Kronmal R, et al. Differentiation of severe coronary artery calcification in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:616–622. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DCCT/EDIC Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2016;65:1370–1379. doi: 10.2337/db15-1517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang S, Dai J, Jia H, Hu S, Du H, Li N, et al. Non-culprit plaque characteristics in acute coronary syndrome patients with raised hemoglobinA1c: an intravascular optical coherence tomography study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17:90. doi: 10.1186/s12933-018-0729-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Scicali R, Giral P, Gallo A, Di Pino A, Rabuazzo AM, Purrello F, et al. HbA1c increase is associated with higher coronary and peripheral atherosclerotic burden in non diabetic patients. Atherosclerosis. 2016;255:102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2016.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tinsley LJ, Kupelian V, D’Eon SA, Pober D, Sun JK, King GL, et al. Association of glycemic control with reduced risk for large-vessel disease after more than 50 years of type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:3704–3711. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-00589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabas I, Williams KJ, Boren J. Subendothelial lipoprotein retention as the initiating process in atherosclerosis: update and therapeutic implications. Circulation. 2007;116:1832–1844. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.676890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Puri R, Nicholls SJ, Shao M, Kataoka Y, Uno K, Kapadia SR, et al. Impact of statins on serial coronary calcification during atheroma progression and regression. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65:1273–1282. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zheng G, Li Y, Huang H, Wang J, Hirayama A, Lin J. The effect of statin therapy on coronary plaque composition using virtual histology intravascular ultrasound: a meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0133433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Criqui MH, Denenberg JO, Ix JH, McClelland RL, Wassel CL, Rifkin DE, et al. Calcium density of coronary artery plaque and risk of incident cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2014;311:271–278. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Breuker C, Clement F, Mura T, Macioce V, Castet-Nicolas A, Audurier Y, et al. Non-achievement of LDL-cholesterol targets in patients with diabetes at very-high cardiovascular risk receiving statin treatment: incidence and risk factors. Int J Cardiol. 2018;268:195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nicholls SJ, Tuzcu EM, Kalidindi S, Wolski K, Moon KW, Sipahi I, et al. Effect of diabetes on progression of coronary atherosclerosis and arterial remodeling: a pooled analysis of 5 intravascular ultrasound trials. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.03.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stegman B, Puri R, Cho L, Shao M, Ballantyne CM, Barter PJ, et al. High-intensity statin therapy alters the natural history of diabetic coronary atherosclerosis: insights from SATURN. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:3114–3120. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Henein M, Granasen G, Wiklund U, Schmermund A, Guerci A, Erbel R, et al. High dose and long-term statin therapy accelerate coronary artery calcification. Int J Cardiol. 2015;184:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.02.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nerlekar N, Brown AJ, Muthalaly RG, Talman A, Hettige T, Cameron JD, et al. Association of epicardial adipose tissue and high-risk plaque characteristics: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.006379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mohar DS, Salcedo J, Hoang KC, Kumar S, Saremi F, Erande AS, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue volume as a marker of coronary artery disease severity in patients with diabetes independent of coronary artery calcium: findings from the CTRAD study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;106:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2014.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Versteylen MO, Takx RA, Joosen IA, Nelemans PJ, Das M, Crijns HJ, et al. Epicardial adipose tissue volume as a predictor for coronary artery disease in diabetic, impaired fasting glucose, and non-diabetic patients presenting with chest pain. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13:517–523. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jes024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang CP, Hsu HL, Hung WC, Yu TH, Chen YH, Chiu CA, et al. Increased epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) volume in type 2 diabetes mellitus and association with metabolic syndrome and severity of coronary atherosclerosis. Clin Endocrinol. 2009;70:876–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2008.03411.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Muhlestein JB, Lappe DL, Lima JA, Rosen BD, May HT, Knight S, et al. Effect of screening for coronary artery disease using CT angiography on mortality and cardiac events in high-risk patients with diabetes: the FACTOR-64 randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312:2234–2243. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.15825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wackers FJ, Young LH, Inzucchi SE, Chyun DA, Davey JA, Barrett EJ, et al. Detection of silent myocardial ischemia in asymptomatic diabetic subjects: the DIAD study. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1954–1961. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.8.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lambrechtsen J, Gerke O, Egstrup K, Sand NP, Norgaard BL, Petersen H, et al. The relation between coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic subjects and both traditional risk factors and living in the city centre: a DanRisk substudy. J Intern Med. 2012;271:444–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sabour S, Rutten A, van der Schouw YT, Atsma F, Grobbee DE, Mali WP, et al. Inter-scan reproducibility of coronary calcium measurement using Multi Detector-Row Computed Tomography (MDCT) Eur J Epidemiol. 2007;22:235–243. doi: 10.1007/s10654-007-9123-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the corresponding author on request.