Abstract

Background

The prevalence of overweight/obesity in adults is raised to 39%, which is nearly tripled more than 1975. The alteration of the gut microbiome has been widely accepted as one of the main causal factors. To find an effective strategy for the prevention and treatment of overweight/obesity, a systematic review and meta-analysis were designed.

Methods

In this study, we systematically reviewed the article published from January 2008 to July 2018 and conducted a meta-analysis to examine the effects of probiotics on body weight control, lipid profile, and glycemic control in healthy adults with overweight or obesity. The primary outcomes were body weight, body mass index (BMI), waist circumference, fat mass, fat percentages, plasma lipid profiles, and glucose metabolic parameters.

Results

We systematically searched PubMed, Embase, and the Web of Science and identified 1248 articles, and 7 articles which were manually searched by the references of included studies and previously systematic reviews. Twelve randomized controlled trials (RCTs), including 821 participants, were included in the meta-analysis via full-text screening. Probiotics supplementation resulted in a statistical reduction in body weight (WMD [95% CI]; -0.55 [-0.91, -0.19] kg), BMI (WMD [95% CI]; -0.30 [-0.43, -0.18] kg m−2), waist circumference (WMD [95% CI]; -1.20 [-2.21, -0.19] cm), fat mass (WMD [95% CI]; -0.91 [-1.19, -0.63] kg), and fat percentage (WMD [95% CI]; -0.92 [-1.27, -0.56] %) compared with control groups. As expected, the metabolic parameters were improved significantly, with a pooled standardized mean difference in TC (SMD [95% CI]; -0.43 [-0.80, -0.07]), LDL-C (SMD [95% CI]; -0.41 [-0.77, -0.04]), FPG (SMD [95% CI]; -0.35 [-0.67, -0.02]), insulin (SMD [95% CI]; -0.44 [-0.84, -0.03]), and HOMA-IR (SMD [95% CI]; -0.51 [-0.96, -0.05]), respectively. The changes in TG (SMD [95% CI]; 0.14 [-0.23, 0.50]), HDL-C (SMD [95% CI]; -0.31 [-0.70, 0.07]), and HbA1c (SMD [95% CI]; -0.23 [-0.46, 0.01]) were not significant.

Conclusion

This study suggests that the probiotics supplementation could potentially reduce the weight gain and improve some of the associated metabolic parameters, which may become an effective strategy for the prevention and treatment of obesity in adult individuals.

1. Introduction

Overweight/obesity is one of the most widespread chronic diseases around the world with the character of excessive energy intake and insufficient energy expenditure [1, 2] and with an elevated risk of several chronic diseases, including type 2 diabetes, hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and cancer [3–5]. Recent studies revealed that the occurrence of obesity is associated with the gut microbial dysbiosis, which might induce the alteration of the host's energy absorption and influence intestinal permeability, and the fasting-induced adipose factor [3, 4, 6, 7].

Interestingly, emerging evidence suggests that the probiotics are the organic component of the gut microflora and could meliorate the gut microbiota [3, 4]. As a kind of active microorganism, the probiotics regulate the intestinal microecosystem, improve the gut microecosystem and the host energy metabolism, and reduce the chronic inflammation and oxidative stress [4, 8, 9]. These studies indicate that probiotics may play a role in the prevention and treatment of obesity by regulating the gut microbiota [4, 10, 11]. Overweight/obesity, which is associated with the loss of glycemic control and dyslipidemia, could seriously affect the patients' life quality and increase their economic burden [1, 9, 12]. However, the effect of probiotics to control the body weight and related clinical indicators in healthy adults with obesity are remaining unclear. Several randomized controlled studies evaluated the effects of probiotics on body weight control, lipid profiles, and glycemic control and gave conflicting results; several studies suggest that probiotics play an important role in the prevention of obesity [13–19], while other studies hold different views [20–22]. Studies indicated that overweight/obesity is usually associated with elevated levels of plasma lipid profiles concomitant with impaired glucose metabolism [23, 24]. However, no previous review has assessed the effect of probiotics on plasma lipid profiles and glycemic parameters. According to previous studies, multiple factors could influence the effects of probiotics [23, 25, 26]. To evaluate the obesity controlling effect of probiotics, we conducted the systematic review and meta-analysis on the correlation of probiotics and plasma lipid profiles, glucose metabolic parameters.

2. Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

Two reviewers independently executed a systematic literature search on 16 July 2018 from the databases of PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science. The search was limited to the clinical randomized controlled trials (RCTs). For search strategies designed for PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science, we used the controlled vocabulary terms for each concept (e.g., MeSH) and keyword synonyms (see Table S1 for exact search strategies). We also manually searched the references of included studies and previously systematic reviews to identify further relevant studies.

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Studies were selected on the basis of the following criteria: (1) overweight and obesity were defined by body mass index (BMI); only the studies with individuals with a BMI > 25 kg m−2 were included; (2) only the studies with general healthy individuals were included; (3) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of adults (≥18 years old) were included; (4) changes in weight-loss in adults between pre- and postintervention by probiotics consumption were the primary outcomes, and the lipid profiles and glucose metabolic parameters were considered as the secondary outcomes. In the event when there were multiple intervention groups (multiple strains or multiple dosages of probiotics) in one study, only the largest number of strains or dosage of probiotics group and placebo group were included [27].

The exclusion criteria were (1) studies with breast-breeding or pregnant patients; (2) patients with diabetes, hypertension, chronic immunologic diseases, thyroid diseases, gastrointestinal surgery, or other chronic disease; (3) the trials with participants who consumed prebiotics, synbiotics, herb, and other supplements (such as micronutrients or other dietary constituents).

2.3. Data Extraction

Two investigators independently executed the literature search, data extraction, and quality assessment based on the eligibility criteria. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between data collectors alone with a third investigator. Data on year, country, study design, population, types of probiotics administration, duration of treatment, and clinical outcomes were extracted from the included studies.

2.4. Risk of Bias with Individual Studies

The risk of bias within randomized controlled trials was independently evaluated by two investigators. The risk of selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, and other biases of the included trials was assessed as high, low, or unclear, using the Cochrane Collaboration tool [28].

2.5. Statistical Analysis

The differences in the mean change from baseline in body weight/BMI/waist circumference/fat mass/fat percentage/glycaemic factors/lipid profiles comprised the primary measure of treatment effect. The meta-analysis was conducted via Review Manager 5.3. It was a significant result when the P value was less than 0.05. The changes between baseline and after intervention on weight-loss (e.g., body weight, BMI, waist circumference, fat mass, and fat percentage) were analyzed by the weighted mean difference (WMD). While the changes in lipid and glucose metabolic parameters were analyzed by the standardized mean difference (SMD), the results of lipid and glucose metabolic parameters were measured in a variety of ways [29]. The mean change (standard deviation) in weight-loss and lipid and glucose metabolic parameters from baseline was used to calculate the mean difference (95% confidence interval [CI]) between intervention groups and control groups. When not provided by the authors, we calculated the standard deviation (SD) of the mean change using the correlation coefficient formula in the succeeding text [29]. Imputation of the SD includes three steps: (1) calculate the correlation coefficient (Corr) between the baseline and final values for each intervention group and control group from the included trials; (2) take the average of these Corrs as the imputed Corr; (3) impute the SD of mean change with the imputed Corr [29].

| (1) |

Results from all the RCTs were used to calculate the WMD or SMD using a random effects model. Heterogeneity among the included studies was evaluated by Cochrane Q-test and I square (I2). I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered as low, moderate, and high level of heterogeneity [30]. Subgroup analyses and sensitivity analyses were conducted based on probiotics dosage, numbers of probiotics species, and forms of probiotics, except that the included studies were less than 7. Sensitivity analyses were also conducted by omitting one trial at a time from the included studies, thereby assessing its effect on the WMD or SMD. The funnel plot and Egger's regression test were conducted by STATA/IC 15.0 to assess the possible publication bias of the included studies. There was no publication bias if the P value was more than 0.1 in Egger's regression test.

3. Results

3.1. Search Results and the General Characteristics of Included Studies

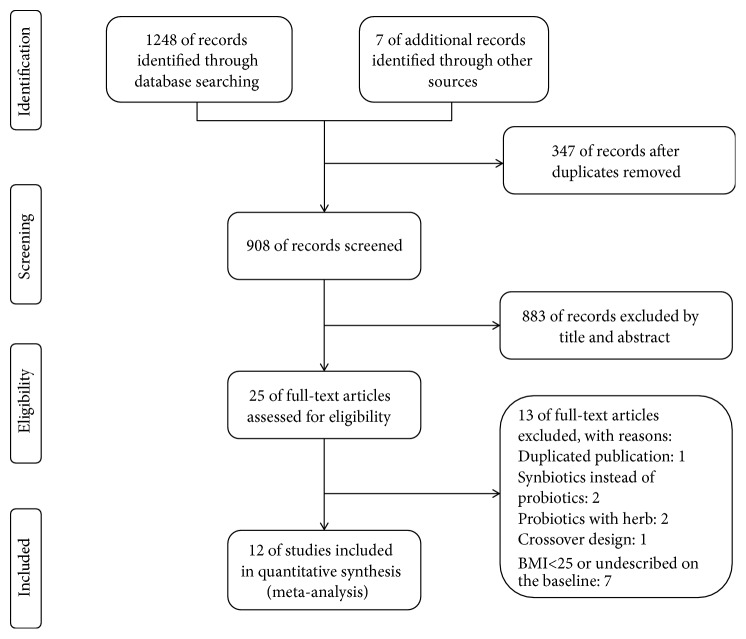

A total of 1255 literatures (191 from PubMed, 719 from Embase, 338 from Web of Science, and 7 from references) were identified using the search strategy previously described in the method part, from which 347 were excluded after duplicate deletion (Figure 1). Two investigators independently identified 25 articles by screening the title and abstract using the eligibility criteria as described previously. Of the 25 studies, 13 studies did not match the eligibility criteria; 12 RCTs including 11 randomized, double-blinded, controlled trials and 1 randomized, single-blinded, controlled trial were included in the meta-analysis.

Figure 1.

Study flow diagram for study selection.

The general characteristics of the 12 included studies are presented in Table 1, of which 7 studies included participants who consumed two or multiple strains of probiotics, and 5 studies included participants who consumed a single strain of probiotics. 7 studies investigated a high dosage of probiotics (>1010 CFU) and 5 studies investigated lower dosage of probiotics (<1010 CFU). Among the 12 included studies that comprised a total of 821 subjects, 416 participants were given placebo and 405 participants were given probiotics. Probiotics were administered in different forms, including sachet, capsule, powder, kefir, yogurt, and fermented milk. Duration of the probiotics supplementation ranged from 8 to 24 weeks.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies.

| Studies | Country | No. of participants (P/C) | Trial Number | ITT | Study design | Form of probiotics | Probiotics strains | Daily dose (CFU) |

Duration (Weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Szulińska 2018[31] | Poland | 47 (24/23) | NCT03100162 | No | DB, PC | Sachet | Multi (Bifidobacterium bifidum W23, Bifidobacterium lactis W51, Bifidobacterium lactis W52, Lactobacillus acidophilus W37, Lactobacillus brevis W63, Lactobacillus casei W56, Lactobacillus salivarius W24, Lactococcus lactis W19, and Lactococcus lactis W58) | 1×1010 | 12 |

|

| |||||||||

| Kim 2018[13] | Korea | 60 (30/30) | KCT0000756 | Yes | DB, PC | Capsule | Single (Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17) | 1×1010 | 12 |

|

| |||||||||

| Gomes 2017[14] | Brazil | 43 (22/21) | U1111-1137-4566 | No | DB, PC | Sachet | Multi (Lactobacillus acidophilus LA - 14, Lactobacillus casei LC - 11, Lactococcus lactis LL - 23, Bifidobacterium bifidum BB - 06, and Bifidobacterium lactis BL - 4) | 2×1010 | 8 |

|

| |||||||||

| Kim 2017[15] | Korea | 66 (34/32) | NCT02492698 | No | DB, PC | Powder | Multi (Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 and Lactobacillus plantarum KY1032) | 5×109 | 12 |

|

| |||||||||

| Stenman 2016[20] | Finland | 104 (56/48) | NCT01978691 | ITT | DB, PC | Sachet | Single (Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis 420) | 1×1010 | 26∗ |

|

| |||||||||

| Higashikawa 2016[32] | Japan | 41 (20/21) | / | ITT | DB, PC | Powder | Single (Pediococcus pentosaceus LP28) | 1×1011 | 12 |

|

| |||||||||

| Chung 2016[16] | Korea | 37 (19/18) | KCT0000452 | No | DB, PC | Capsule | Single (Lactobacillus JBD301) | 1×109 | 12 |

|

| |||||||||

| Fathi 2016[21] | Iran | 50 (25/25) | IRCT2013061313661N1 | ITT | DB, PC | Kefir | / | / | 8 |

|

| |||||||||

| Madjd 2016[22] | Iran | 89 (45/44) | IRCT201402177754N8 | ITT | SB, PC | Yogurt | Multi (Lactobacillus acidophilus LA5, Bifidobacterium lactis BB12) | 1×107 | 12 |

|

| |||||||||

| Jung 2015[17] | Korea | 95 (46/49) | / | No | DB, PC | Powder | Multi (Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 and Lactobacillus plantarum KY1032) | 1×1010 | 12 |

|

| |||||||||

| Zarrati 2014[18] | Iran | 50 (25/25) | / | ITT | DB, PC | Yogurt | Multi (Lactobacillus acidophilus La5, Bifidobacterium BB12, and Lactobacillus casei DN001) | 6×109 | 8 |

|

| |||||||||

| Kadooka 2013[19] | Japan | 139 (70/69) | / | ITT | DB, PC | Fermented milk | Single (Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055) | 2×1011 | 12 |

P/C, probiotic group/control group; ITT/PP, Intention-To-Treat/Per-Protocol; DB, double blinded; PC, placebo controlled; SB, single blinded; CFU, colony-forming units; ∗ 6 months.

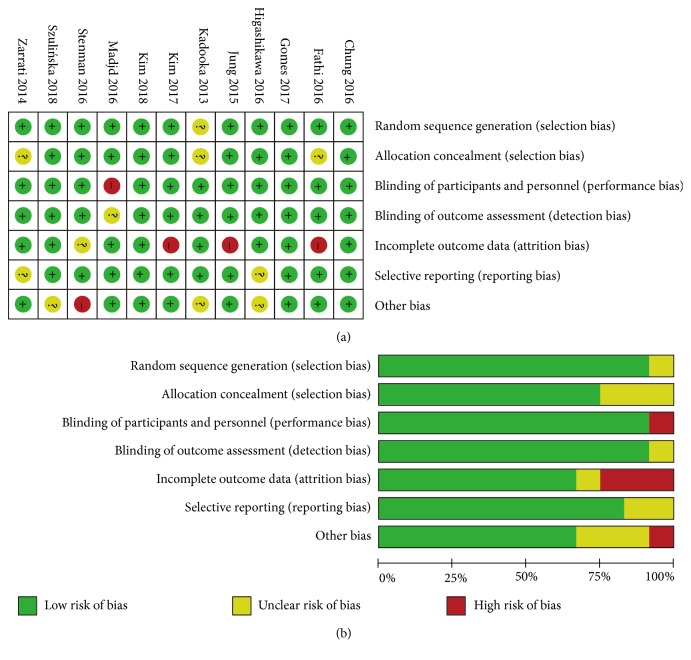

3.2. Risk of Bias with Individual Studies

The Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessment of randomized controlled trials was independently carried out to assess the risk of bias among the included studies by two authors. There was no significant selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, or other biases detected among the included trials (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Risk of bias assessment: (a) details of included studies; (b) overall summary.

3.3. Effects of Probiotics on Weight-Loss and Associated Metabolic Parameters

3.3.1. Probiotics and Weight-Loss (Body Weight, BMI, Waist Circumference, Fat Mass, and Fat Percentage)

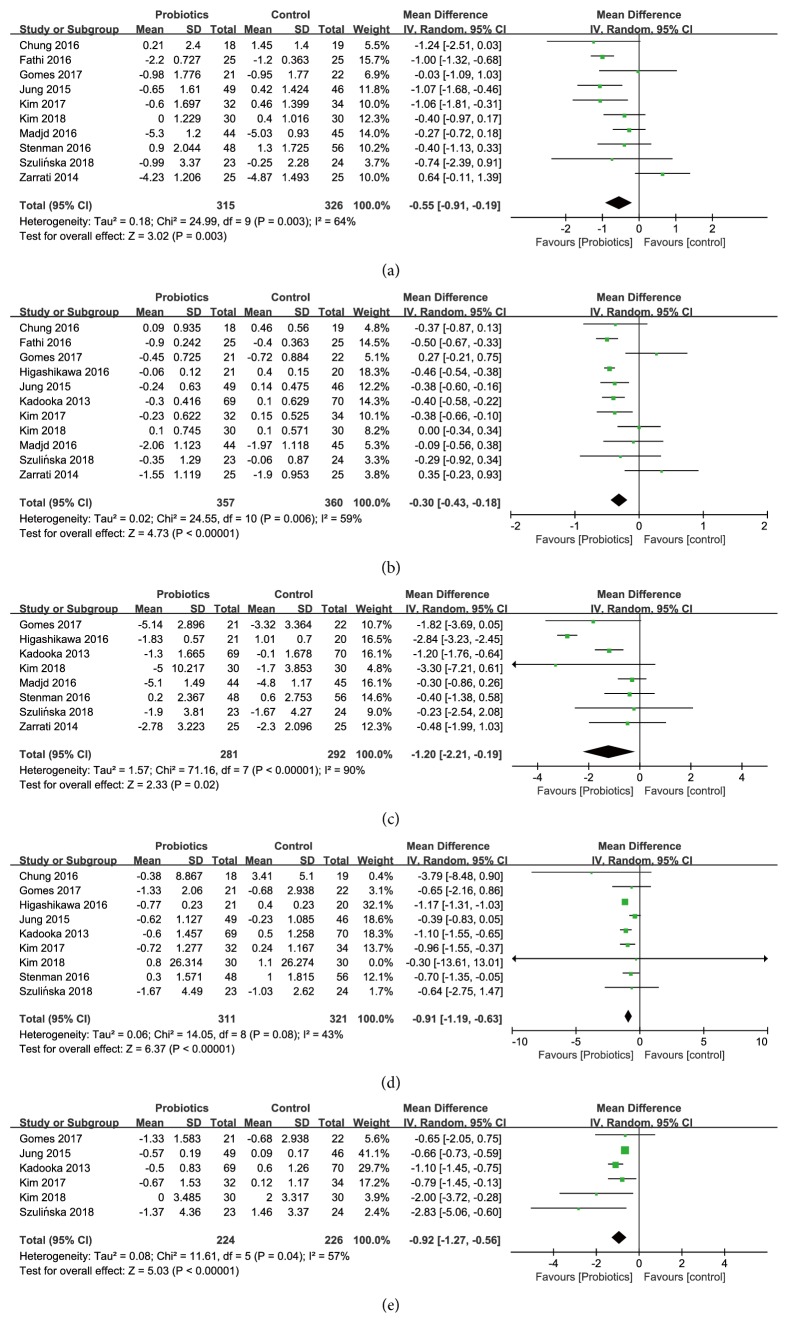

Effects on Body Weight. The overall estimates of the 10 studies among 641 participants (315 consuming probiotics, 326 not consuming probiotics) with changes in body weight showed a statistically significant body weight reduction (WMD [95% CI]; -0.55 [-0.91, -0.19] kg, P = 0.003) in the probiotics group, comparing with the control group (Figure 3(a)), and there was a moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 64%, P =0.003). Subgroup analyses (Table 2) stratified by probiotics dosage, the number of probiotics strains, or forms of probiotics showed the effects of probiotics supplementation on body weight were significantly reduced in trials with high dose of probiotics (-0.58 [-0.92, -0.23] kg), a single strain of probiotics (-0.49 [-0.92, -0.07] kg), and the capsule or powder of probiotics (-0.55 [-0.84, -0.26] kg). Sensitivity analyses revealed that no particular studies significantly affected the summary effects of body weight.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of effect of probiotics on (a) body weight; (b) BMI; (c) waist circumference; (d) fat mass; (e) fat percentage.

Table 2.

Subgroup analyses for the effects of probiotics on body weight.

| Subgroup | Number of trials | Number of participants | I 2 | Weighted mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | |||

| Probiotics dosage | ||||

| ≥ 1010 CFU | 5 | 171 | 3.8 | -0.58 (-0.92, -0.23) |

| < 1010 CFU | 4 | 119 | 75.0 | -0.41(-1.15, 0.34) |

| Number of probiotics species | ||||

| Single | 3 | 96 | 0 | -0.49 (-0.92, -0.07) |

| Multiple | 6 | 194 | 68.5 | -0.41 (-0.97, 0.14) |

| Form of probiotics | ||||

| Capsule or powder | 7 | 247 | 19.4 | -0.55(-0.84, -0.26) |

| Food | 3 | 68 | 87.5 | -0.50(-1.68, 0.67) |

There was no significant publication bias analyzed by Egger's test for the effect of probiotics on body weight (P = 0.446), and the funnel plot was presented in Figure S1.

Effects on Body Mass Index (BMI). 11 studies, among 717 participants (357 consuming probiotics, 360 not consuming probiotics), reported the effect of probiotics supplementation on BMI (Figure 3(b)). Comparing with the control group, the reduction of BMI was statistically significant with a pooled weighted mean difference of -0.30 kg m−2 (WMD [95% CI]; [-0.43, -0.18], P < 0.00001) in the intervention group with a moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 59%, P = 0.006) between the studies.

Subgroup analyses (Table 3) stratified by probiotics dosage, the number of probiotics strains, or forms of probiotics showed the effects of probiotics supplementation on BMI were significantly reduced with the high dose (-0.29 [-0.46, -0.12] kg m−2) and single strain of probiotics (-0.36 [-0.52, -0.20] kg m−2). However, the reduction was not significantly associated with two subgroups stratified by the forms of probiotics. Sensitivity analyses revealed that no particular studies significantly affected the summary effects of BMI.

Table 3.

Subgroup analyses for the effects of probiotics on BMI.

| Subgroup | Number of trials | Number of participants | I 2 | Weighted mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | |||

| Probiotics dosage | ||||

| ≥ 1010 CFU | 6 | 213 | 66.6 | -0.29 (-0.46, -0.12) |

| < 1010 CFU | 4 | 119 | 46.9 | -0.18 (-0.48, 0.12) |

| Number of probiotics species | ||||

| Single | 4 | 138 | 56.8 | -0.36 (-0.52, -0.20) |

| Multiple | 6 | 194 | 55.5 | -0.15 (-0.39, 0.10) |

| Form of probiotics | ||||

| Capsule or powder | 7 | 220 | 64.1 | -0.25(-0.43, -0.07) |

| Food | 4 | 137 | 61.4 | -0.34(-0.57, -0.12) |

The risk of publication bias analyzed by Egger's test for the effect of probiotics on BMI (Egger's test P=0.006) was high, and the funnel plot was presented in Figure S1. To identify and correct the publication bias, five hypothetical negative unpublished trials were conservatively imputed to mirror the positive trials that caused funnel plot asymmetry via the “trim and fill” method. The reduction of BMI incorporating the hypothetical trials continued to be statistically significant with a pooled weighted mean difference of -0.44 kg m−2 (WMD [95% CI]; [-0.57, -0.30], P < 0.0001) in the intervention group. The funnel plot produced by imputed trials was presented in Figure S1.

Effects on Waist Circumference. Eight studies, among 573 participants (281 consuming probiotics, 292 not consuming probiotics), reported the effect of probiotics supplementation on waist circumference (Figure 3(c)). The reduction of waist circumference was statistically significant with a pooled weighted mean difference of -1.20 cm (WMD [95% CI]; [-2.21, -0.19], P = 0.02) in the intervention group compared with the control group, with a high level of heterogeneity (I2 = 90%, P < 0.00001) between the studies. Subgroup analyses (Table 4) stratified by probiotics dosage, the number of probiotics strains, or forms of probiotics indicated the effects of probiotics supplementation on waist circumference were significantly reduced in trials with high dose of probiotics (-1.53 [-2.64, -0.41] cm), a single strain of probiotics (-1.69 [-3.04, -0.33] cm), and the food form of probiotics (-1.11 [-1.64, -0.59] cm). Sensitivity analyses revealed that no particular studies significantly affected the summary effects of waist circumference.

Table 4.

Subgroup analyses for the effects of probiotics on waist circumference.

| Subgroup | Number of trials | Number of participants | I 2 | Weighted mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | |||

| Probiotics dosage | ||||

| ≥ 1010 CFU | 6 | 212 | 86.9 | -1.53 (-2.64, -0.41) |

| < 1010 CFU | 2 | 69 | 0 | -0.32 (-0.84, 0.20) |

| Number of probiotics species | ||||

| Single | 4 | 168 | 91.6 | -1.69 (-3.04, -0.33) |

| Multiple | 4 | 113 | 0 | -0.42 (-0.91, 0.07) |

| Form of probiotics | ||||

| Capsule or powder | 6 | 187 | 92.3 | -1.34 (-2.76, 0.08) |

| Food | 2 | 94 | 0 | -1.11 (-1.64, -0.59) |

There was no sign of publication bias detected by Egger's test for the effect of probiotics on waist circumference (P = 0.403), and the funnel plot was presented in Figure S1.

Effects on Fat Mass and Fat Percentage. A total of 9 studies including 632 participants (311 consuming probiotics, 321 not consuming probiotics) evaluated the effect of probiotics supplementation on fat mass (Figure 3(d)), and 6 studies with 450 participants (224 consuming probiotics, 226 not consuming probiotics) reported changes in fat percentage (Figure 3(e)). Probiotics significantly reduced the fat mass (WMD [95% CI]; -0.91 [-1.19, -0.63] kg, P < 0.00001) in the intervention group with a moderate level of heterogeneity (I2 = 43%, P = 0.08). A pooled effect of fat percentage in the intervention group was also significant (WMD [95% CI]; -0.92 [-1.27, -0.56] %, P < 0.00001) with a moderate level of heterogeneity (I2 =57%, P =0.04).

Subgroup analyses stratified by probiotics dosage, the number of probiotics strains, and forms of probiotics indicated that the effect of probiotics supplementation on fat mass was significantly reduced (Table 5), showing a greater decrease in fat mass with high dosage probiotics (-1.08 [-1.21, -0.95] kg) compared to low dosage probiotics (-1.00 [-1.59, -0.42] kg), a greater decrease with single strain probiotics (-1.15 [-1.28, -1.02] kg) compared to multiple strain probiotics (-0.60 [-0.94, -0.26] kg), and a greater decrease with administration probiotics in the form of food (-1.13 [-1.58, -0.67] kg) compared to in the forms of capsule or powder (-1.07 [-1.20, -0.94] kg). Due to the fact that few trials reported the effect of probiotics on fat percentage, subgroup analyses were not performed to investigate the source of heterogeneity. No particular study significantly affected the pooled effect of probiotics on fat mass and fat percentage by sensitivity analyses.

Table 5.

Subgroup analyses for the effects of probiotics on fat mass.

| Subgroup | Number of trials | Number of participants | I 2 | Weighted mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | |||

| Probiotics dosage | ||||

| ≥ 1010 CFU | 7 | 261 | 52.5 | -1.08 [-1.21, -0.95] |

| < 1010 CFU | 2 | 50 | 27.2 | -1.00 [-1.59, -0.42] |

| Number of probiotics species | ||||

| Single | 5 | 186 | 0 | -1.15 [-1.28, -1.02] |

| Multiple | 3 | 125 | 0 | -0.60 [-0.94, -0.26] |

| Form of probiotics | ||||

| Capsule or powder | 6 | 224 | 53.0 | -1.07 [-1.20, -0.94] |

| Food | 2 | 87 | 20.0 | -1.13 [-1.58, -0.67] |

There was no sign of publication bias on the effect of probiotics to fat mass (Egger's test P = 0.335) and fat percentage (Egger's test P = 0.068). The funnel plots were presented in Figure S1.

3.3.2. Probiotics and Lipid Profiles (TC, TG, LDL-C, and HDL-C Level)

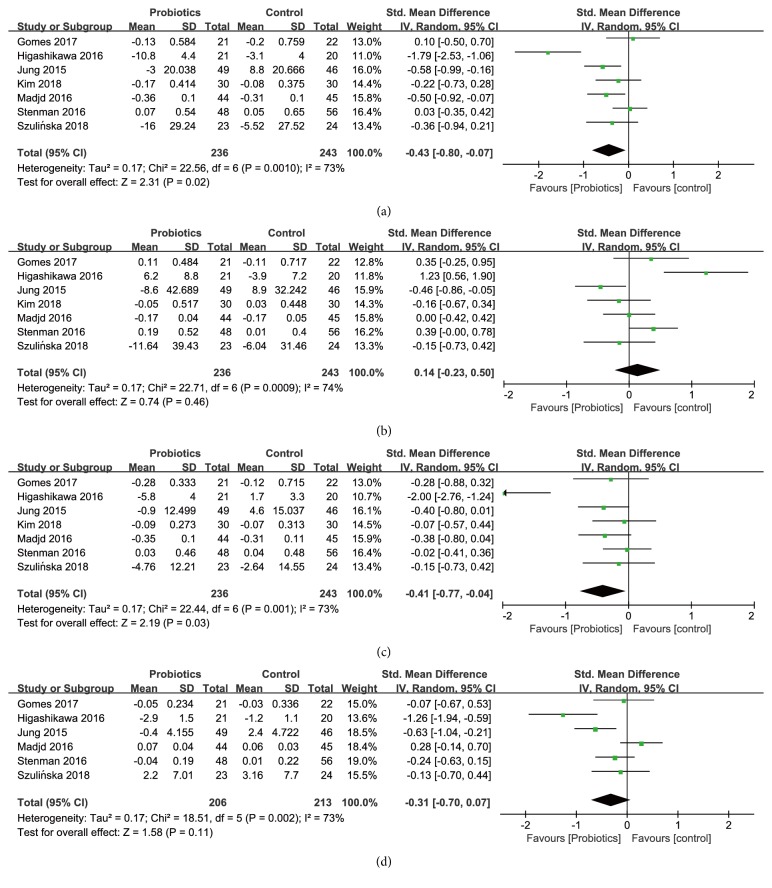

Effects on Total Cholesterol (TC). Seven studies, among 479 participants (236 consuming probiotics, 243 not consuming probiotics), reported the effect of probiotics supplementation on TC (Figure 4(a)). There was a statistically significant reduction in the intervention group with a pooled standardized mean difference of -0.43 (SMD [95% CI]; [-0.80, -0.07], P = 0.02) with a moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 73%, P = 0.001) between the studies.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of effect of probiotics on (a) TC; (b) TG; (c) LDL-C; (d) HDL-C.

Because there were no studies that reported the effect of probiotics on TC in the form of food, subgroup analyses (Table 6) only stratified by probiotics dosage and the number of probiotics strains indicated the effects of probiotics supplementation on TC were significantly reduced in trials with single strain probiotics (-0.61 [-1.54, -0.32]), compared to multiple strain probiotics (-0.39 [-0.66, -0.13]). Sensitivity analyses revealed that no particular studies significantly affected the summary effects of TC.

Table 6.

Subgroup analyses for the effects of probiotics on TC.

| Subgroup | Number of trials | Number of participants | I 2 | Standardized mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | |||

| Probiotics dosage | ||||

| ≥ 1010 CFU | 6 | 192 | 77.4 | -0.43 [-0.87, 0.01] |

| < 1010 CFU | 1 | 44 | / | -0.50 [-0.92, -0.07] |

| Number of probiotics species | ||||

| Single | 3 | 99 | 89.3 | -0.61 [-1.54, -0.32] |

| Multiple | 4 | 137 | 16.8 | -0.39 [-0.66, -0.13] |

There was no sign of publication bias analyzed by Egger's test for the effect of probiotics on TC (P = 0.276), and the funnel plot was presented in Figure S2.

Effects on Triglyceride (TG). A total of 7 studies including 479 participants (236 consuming probiotics, 243 not consuming probiotics) evaluated the effect of probiotics supplementation on TG. There was no statistically significant reduction in TG levels (Figure 4(b)) with a pooled standardized mean difference of 0.14 (SMD [95% CI]; [-0.23, 0.50], P=0.46) and a moderate heterogeneity (I2=74%, P=0.0009).

Subgroup analyses (Table 7) stratified by probiotics dosage and the number of probiotics strains indicated the effects of probiotics supplementation on TG were not significantly reduced in subgroup analyses. Sensitivity analyses revealed that no particular studies significantly affected the summary effects of TG.

Table 7.

Subgroup analyses for the effects of probiotics on TG.

| Subgroup | Number of trials | Number of participants | I 2 | Standardized mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | |||

| Probiotics dosage | ||||

| ≥ 1010 CFU | 6 | 192 | 77.8 | 0.17 [-0.27, 0.61] |

| < 1010 CFU | 1 | 44 | / | 0.00 [-0.42, -0.42] |

| Number of probiotics species | ||||

| Single | 3 | 99 | 81.0 | 0.45 [-0.23, 1.13] |

| Multiple | 4 | 137 | 43.4 | -0.10 [-0.43, 0.22] |

There was no sign of publication bias of the effect of probiotics on TG (Egger's test P = 0.300), and the funnel plot was presented in Figure S2.

Effects on Low Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C). Seven studies among 479 participants (236 consuming probiotics, 243 not consuming probiotics) reported the changes of LDL-C (Figure 4(c)). Comparing with the control group the pooled standardized mean difference showed a statistically significant reduction in LDL-C in probiotics group (SMD [95% CI]; -0.41 [-0.77, -0.04], P = 0.03) with a moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 73%, P = 0.001).

Subgroup analyses (Table 8) stratified by probiotics dosage and the number of probiotics strains indicated the effects of probiotics supplementation on LDL-C were significantly reduced in trials with multiple strain probiotics (-0.33 [-0.57, -0.09]). Sensitivity analyses revealed that no particular studies significantly affected the summary effects of LDL-C.

Table 8.

Subgroup analyses for the effects of probiotics on LDL-C.

| Subgroup | Number of trials | Number of participants | I 2 | Standardized mean difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (95% CI) | |||

| Probiotics dosage | ||||

| ≥ 1010 CFU | 6 | 192 | 77.6 | -0.43 [-0.87, 0.02] |

| < 1010 CFU | 1 | 44 | / | -0.38 [-0.80, 0.04] |

| Number of probiotics species | ||||

| Single | 3 | 99 | 90.9 | -0. 64 [-1.66, 0.37] |

| Multiple | 4 | 137 | 73.3 | -0.33 [-0.57, -0.09] |

There was no sign of publication bias of the effect of probiotics on LDL-C (Egger's test P = 0.124), and the funnel plot was presented in Figure S2.

Effects on High Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (HDL-C). A total of 6 studies including 419 participants (206 consuming probiotics, 213 not consuming probiotics) evaluated the effect of probiotics supplementation on HDL-C. Effect of probiotics on TG levels showed weak significance (Figure 4(d)) with a pooled standardized mean difference of -0.31 (SMD [95% CI]; [-0.70, 0.07], P=0.11) and a moderate level of heterogeneity (I2=73%, P=0.002). Due to no more than 7 studies reported on the effects of probiotics on HDL-C, subgroup analyses were not conducted. No particular study significantly affected the pooled effect of probiotics on HDL-C by sensitivity analyses.

There was no sign of publication bias analyzed by Egger's test for the effect of probiotics on HDL-C (P = 0.484).

3.3.3. Probiotics and Glucose Metabolism (Fasting Plasma Glucose, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR)

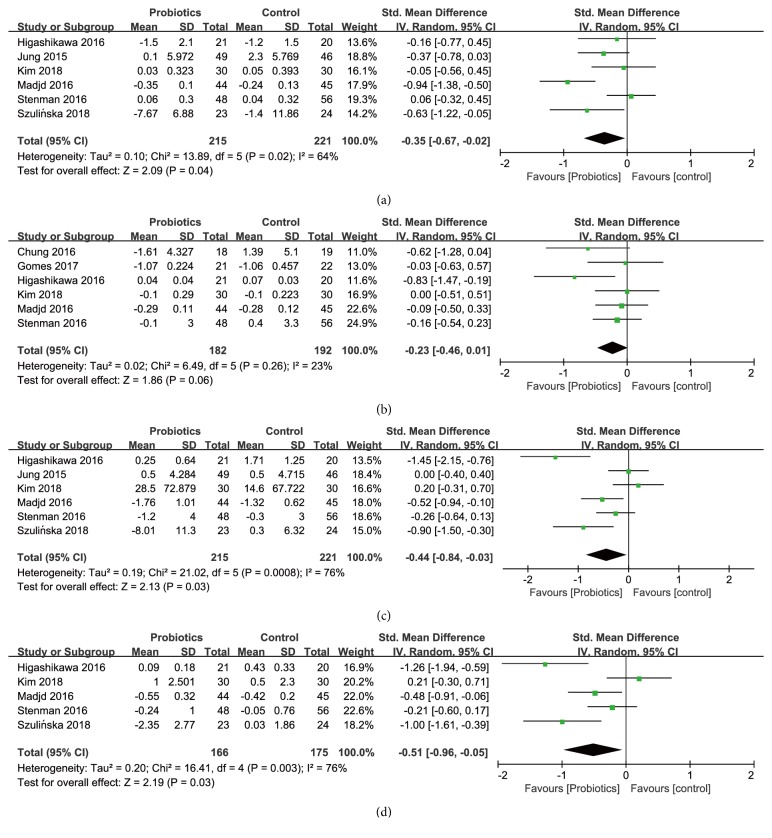

Effects on Fasting Plasma Glucose (FPG). Six studies among 436 participants (215 consuming probiotics, 221 not consuming probiotics) reported on changes in fasting plasma glucose (Figure 5(a)), and the pooled standardized mean difference showed a statistically significant reduction in fasting plasma glucose in probiotics group (SMD [95% CI]; -0.35 [-0.67, -0.02], P = 0.04) compared with the control group, with a moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 64%, P = 0.02).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of effect of probiotics on (a) fasting plasma glucose; (b) HbA1c; (c) insulin; (d) HOMA-IR.

There was no sign of publication bias analyzed by Egger's test for the effect of probiotics on FPG (Egger's test P = 0.791).

Effects on Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). Six studies including 374 participants (182 consuming probiotics, 192 not consuming probiotics) reported on changes in HbA1c (Figure 5(b)), and the pooled standardized mean difference showed a weak trend toward significance in HbA1c in probiotics group (SMD [95% CI]; -0.23 [-0.46, 0.01], P = 0.06) compared with the control group, with a low level of heterogeneity (I2 = 23%, P = 0.26).

There was no sign of publication bias analyzed by Egger's test for the effect of probiotics on HbA1c (Egger's test P = 0.190).

Effects on Insulin. A total of 6 studies including 436 participants (215 consuming probiotics, 221 not consuming probiotics) evaluated the effect of probiotics supplementation on insulin (Figure 5(c)). In comparison with the control group after treatment, the reduction of insulin was statistically significant with a pooled standardized mean difference of -0.44 (SMD [95% CI]; [-0.84, -0.03], P = 0.03) in the probiotics group, with a high level of heterogeneity (I2 = 76%, P = 0.0008) between the studies.

There was no sign of publication bias analyzed by Egger's test for the effect of probiotics on insulin (Egger's test P = 0.133).

Effects on Homeostasis Model of Assessment for Insulin Resistance Index (HOMA-IR). A total of 5 studies, with 341 participants (166 consuming probiotics, 175 not consuming probiotics), evaluated the effect of probiotics supplementation on HOMA-IR (Figure 5(d)). Effect of probiotics on HOMA-IR level was shown to be statistically significant, with a pooled standardized mean difference of -0.51 (SMD [95% CI]; [-0.96, -0.05], P=0.03) and a high level of heterogeneity (I2=76%, P=0.003).

There was no sign of publication bias analyzed by Egger's test for the effect of probiotics on HOMA-IR (Egger's test P = 0.244).

Subgroup Analyses and Sensitivity Analyses. Due to no more than 7 studies reported on the effects of probiotics on fasting plasma glucose, HbAlc, insulin, and HOMA-IR, subgroup analyses were not conducted based on probiotics dosage, numbers of probiotics species, and forms of probiotics. No particular study significantly affected the pooled effect of probiotics on glucose metabolic parameters (fasting plasma glucose, HbA1c, and HOMA-IR) by sensitivity analyses.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Our Study

In this study, we performed a systematic review and meta-analysis to examine the effects of probiotics supplementation in healthy adults with overweight/obesity. The results suggest that probiotics have positive effects on weight-loss in parallel with the improvement of the plasma lipid profile and glucose metabolism.

In regard to probiotics and weight-loss, 12 randomized controlled trials were included in the meta-analysis, of which 10 studies reported the changes in body weight, 11 studies reported the changes in BMI, 8 studies reported the changes in waist circumference, 9 studies reported the changes in fat mass, and 6 studies reported the changes in fat percentage. As expected, the body weight reduction was significant in probiotics group with a pooled mean difference (WMD [95% CI]; -0.55 [-0.91, -0.19] kg), BMI (WMD [95% CI]; -0.30 [-0.43, -0.18] kg m−2), waist circumference (WMD [95% CI]; -1.20 [-2.21, -0.19] cm), fat mass (WMD [95% CI]; -0.91 [-1.19, -0.63] kg), and fat percentage (WMD [95% CI]; -0.92 [-1.27, -0.56] %). Different from studies on patients with diabetes or other metabolism syndromes [27], there was also a significant reduction in fat mass and fat percentage in healthy adults.

To characterize the effects of probiotics on plasma lipid profiles, 7 randomized controlled trials were included in the meta-analysis, of which 7 studies reported the changes in TC, TG, or LDL-C, respectively, and 6 studies reported the changes in HDL-C. Similar to the previous study on patients with diabetes or other metabolism syndromes [23, 33], probiotics supplementation also significantly reduced TC (SMD [95% CI]; -0.43 [-0.80, -0.07]) and LDL-C (SMD [95% CI]; -0.41 [-0.77, -0.04]); however, the changes in TG (SMD [95% CI]; 0.14 [-0.23, 0.50]) and HDL-C (SMD [95% CI]; -0.31 [-0.70, 0.07]) were not significant.

Regarding the changes in glucose metabolism, 8 randomized controlled trials were included in the meta-analysis, of which 6 studies reported the changes in PFG, HbA1c, and insulin, respectively. 5 studies reported changes in HOMA-IR. Our findings support the probiotics supplementation could improve the glucose metabolism, which was similar to previous reports in patients with diabetes [33, 34]. Statistically significant reduction was found on FPG (SMD [95% CI]; -0.35 [-0.67, -0.02]), insulin (SMD [95% CI]; -0.44 [-0.84, -0.03]), and HOMA-IR (SMD [95% CI]; -0.51 [-0.96, -0.05]), respectively. However, there was no statistically significant reduction in HbA1c levels with a pooled standardized mean difference of HbA1c (SMD [95% CI]; -0.23 [-0.46, 0.01]).

4.2. The Possible Mechanism

One of the potential mechanisms that has been proposed to explain the results is that through the gut microbiota altered by the probiotics [3]. The probiotics supplementation might increase the short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) producing bacteria, decrease the abundance of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) producers, and relieve the tissue and organic inflammation induced by LPS [3, 8, 35, 36]. The probiotics might also reduce the opportunistic pathogens and their metabolites, such as trimethylamine (TMA), LPS, and indole [37]. Probiotics also could reduce the fat accumulation, downregulate inflammation levels, and improve the insulin sensitivity accompanied by the increase of the neuropeptides and gastrointestinal peptides and the abundance of several beneficial bacteria [4, 8, 9, 38, 39]. As a result, metabolic homeostasis would be improved to keep healthy.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations

To the best of our knowledge, no previous study has systematically reviewed and analyzed the effects of probiotics on weight-loss in healthy adults with a BMI > 25 kg m−2. This study firstly assessed the effects of probiotics on obesity and the associated clinical indicators, such as plasma lipid profiles and glycaemic parameters. In order to get an accurate result, the studies in which participants consumed prebiotics, synbiotics, herb, and other supplements (such as micronutrients or other dietary constituents) were excluded as the effects of probiotics supplementation from those supplementations could not be distinguished; also the possible interaction between probiotics supplementation and those supplementations was excluded.

There are also some limitations in this study. The majority of the included trials were of small size, and four clinical trials were not registered in a clinical trial registry, which may have a risk of reporting bias. One study did not report the species and dose of probiotics supplementation. Besides, the survivability and stability of probiotics, influenced by the manufacturers, could also affect the clinical outcomes. Due to the limited number of included trials, the effects of probiotics supplementation in the prevention and treatment of overweight/obesity still need more intensive work.

5. Conclusions

In summary, our work suggests that probiotics supplementation could reduce the body weight and fat mass and improve some of the lipid and glucose metabolism parameters, although some of the effects were small. Probiotics may become a new potential strategy for the prevention and treatment of overweight/obesity in adult individuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Professor Qiang Feng from Shandong University for revising and correcting the manuscript. This study was supported by the grant from the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2017YL009), Key Research and Development Program of Shandong Province (2018YYSP030), and the Innovation Project of Shandong Academy of Medical Sciences.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

Body mass index

- WMD:

Weighted mean difference

- SMD:

Standardized mean difference

- TC:

Total cholesterol

- TG:

Triglyceride

- HDL-C:

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- LDL-C:

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- FPG:

Fasting plasma glucose

- HbA1c:

Hemoglobin A1c

- HOMA-IR:

Homeostasis model of assessment for insulin resistance index.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

All authors were involved in the conduct of the study, in interpreting the results, and in revising and correcting the manuscript. Shan-Shan Xin and Li-Na Ding individually searched the eligible datasets suitable for meta-analysis. Shan-Shan Xin, Li-Na Ding, and Wen-Yu Ding reviewed and extracted the data from articles. Zhi-Bin Wang, Yan-Li Hou, and Chang-Qing Liu planned and conducted the analysis. Zhi-Bin Wang, Shan-Shan Xin, and Xian-Dang Zhang wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: the search strategy.

Figure S1: the funnel plots of effect of probiotics on (A) body weight; (B) BMI; (C) BMI modified by the “trim and fill” method; (D) waist circumference; (E) fat mass; (F) fat percentage.

Figure S2: the funnel plots of effect of probiotics on (A) total cholesterol; (B) triglyceride; (C) lipoprotein cholesterol.

References

- 1.Gonzalez-Muniesa P., Mártinez-González M., Hu F. B., et al. Obesity. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2017;3:p. 17034. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hill J. O., Wyatt H. R., Peters J. C. Energy balance and obesity. Circulation. 2012;126(1):126–132. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.087213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchesi J. R., Adams D. H., Fava F., et al. The gut microbiota and host health: a new clinical frontier. Gut. 2016;65(2):330–339. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cani P. D., Delzenne N. M. The role of the gut microbiota in energy metabolism and metabolic disease. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2009;15(13):1546–1558. doi: 10.2174/138161209788168164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jung U. J., Choi M. S. Obesity and its metabolic complications: the role of adipokines and the relationship between obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2014;15(4):6184–6223. doi: 10.3390/ijms15046184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henao-Mejia J., Elinav E., Jin C., et al. Inflammasome-mediated dysbiosis regulates progression of NAFLD and obesity. Nature. 2012;482(7384):167–179. doi: 10.1038/nature10809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dongarrà M. L., Rizzello V., Muccio L., et al. Mucosal immunology and probiotics. Current Allergy and Asthma Reports. 2013;13(1):19–26. doi: 10.1007/s11882-012-0313-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun L., Ma L., Ma Y., Zhang F., Zhao C., Nie Y. Insights into the role of gut microbiota in obesity: pathogenesis, mechanisms, and therapeutic perspectives. Protein & Cell. 2018;9(5):397–403. doi: 10.1007/s13238-018-0546-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reilly S. M., Saltiel A. R. Adapting to obesity with adipose tissue inflammation. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2017;13(11):633–643. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2017.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brunkwall L., Orho-Melander M. The gut microbiome as a target for prevention and treatment of hyperglycaemia in type 2 diabetes: from current human evidence to future possibilities. Diabetologia. 2017;60(6):943–951. doi: 10.1007/s00125-017-4278-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Delzenne N. M., Neyrinck A. M., Bäckhed F., Cani P. D. Targeting gut microbiota in obesity: effects of prebiotics and probiotics. Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 2011;7(11):639–646. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2011.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cho I., Yamanishi S., Cox L., et al. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature. 2012;488(7413):621–626. doi: 10.1038/nature11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim J., Yun J. M., Kim M. K., Kwon O., Cho B. Lactobacillus gasseri BNR17 supplementation reduces the visceral fat accumulation and waist circumference in obese adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Medicinal Food. 2018;21(5):454–461. doi: 10.1089/jmf.2017.3937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomes A. C., de Sousa R. G. M., Botelho P. B., Gomes T. L. N., Prada P. O., Mota J. F. The additional effects of a probiotic mix on abdominal adiposity and antioxidant Status: a double-blind, randomized trial. Obesity. 2017;25(1):30–38. doi: 10.1002/oby.21671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim M., Kim M., Kang M., et al. Effects of weight loss using supplementation with Lactobacillus strains on body fat and medium-chain acylcarnitines in overweight individuals. Food & Function. 2017;8(1):250–261. doi: 10.1039/c6fo00993j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung H.-J., Yu J. G., Lee I.-A., et al. Intestinal removal of free fatty acids from hosts by Lactobacilli for the treatment of obesity. FEBS Open Bio. 2016;6(1):64–76. doi: 10.1002/2211-5463.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jung S., Lee Y. J., Kim M., et al. Supplementation with two probiotic strains, Lactobacillus curvatus HY7601 and Lactobacillus plantarum KY1032, reduced body adiposity and Lp-PLA2 activity in overweight subjects. Journal of Functional Foods. 2015;19:744–752. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2015.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarrati M., Salehi E., Nourijelyani K., et al. Effects of probiotic yogurt on fat distribution and gene expression of proinflammatory factors in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in overweight and obese people with or without weight-loss diet. Journal of the American College of Nutrition. 2014;33(6):417–425. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2013.874937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadooka Y., Sato M., Ogawa A., et al. Effect of Lactobacillus gasseri SBT2055 in fermented milk on abdominal adiposity in adults in a randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Nutrition. 2013;110(9):1696–1703. doi: 10.1017/S0007114513001037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stenman L. K., Lehtinen M. J., Meland N., et al. Probiotic with or without fiber controls body fat mass, associated with serum zonulin, in overweight and obese adults—randomized controlled trial. EBioMedicine. 2016;13:190–200. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fathi Y., Faghih S., Zibaeenezhad M. J., Tabatabaei S. H. R. Kefir drink leads to a similar weight loss, compared with milk, in a dairy-rich non-energy-restricted diet in overweight or obese premenopausal women: a randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Nutrition. 2016;55(1):295–304. doi: 10.1007/s00394-015-0846-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madjd A., Taylor M. A., Mousavi N., et al. Comparison of the effect of daily consumption of probiotic compared with low-fat conventional yogurt on weight loss in healthy obese women following an energy-restricted diet: a randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016;103(2):323–329. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.120170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hendijani F., Akbari V. Probiotic supplementation for management of cardiovascular risk factors in adults with type II diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Nutrition. 2018;37(2):532–541. doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Serena C., Ceperuelo-Mallafré V., Keiran N., et al. Elevated circulating levels of succinate in human obesity are linked to specific gut microbiota. The ISME Journal. 2018;12(7):1642–1657. doi: 10.1038/s41396-018-0068-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.John G. K., Wang L., Nanavati J., Twose C., Singh R., Mullin G. Dietary alteration of the gut microbiome and its impact on weight and fat mass: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gene. 2018;9(3):p. 167. doi: 10.3390/genes9030167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabrizi R., Moosazadeh M., Lankarani K. B., et al. The effects of synbiotic supplementation on glucose metabolism and lipid profiles in patients with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Probiotics and Antimicrobial Proteins. 2018;10(2):329–342. doi: 10.1007/s12602-017-9299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borgeraas H., Johnson L. K., Skattebu J., Hertel J. K., Hjelmesæth J. Effects of probiotics on body weight, body mass index, fat mass and fat percentage in subjects with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obesity Reviews. 2018;19(2):219–232. doi: 10.1111/obr.12626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Higgins J. P. T., Altman D. G., Gøtzsche P. C., et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. British Medical Journal. 2011;343(7829) doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928.d5928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins J. P., Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higgins J. P. T., Thompson S. G., Deeks J. J., Altman D. G. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Szulińska M., Łoniewski I., van Hemert S., Sobieska M., Bogdański P. Dose-dependent effects of multispecies probiotic supplementation on the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) level and cardiometabolic profile in obese postmenopausal women: a 12-week randomized clinical trial. Nutrients. 2018;10(6):p. 773. doi: 10.3390/nu10060773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Higashikawa F., Noda M., Awaya T., et al. Antiobesity effect of Pediococcus pentosaceus LP28 on overweight subjects: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2016;70(5):582–587. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2016.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X., Juan Q. F., He Y. W., Zhuang L., Fang Y. Y., Wang Y. H. Multiple effects of probiotics on different types of diabetes: A systematic review & meta-analysis of randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2017;30(6):611–622. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2016-0230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun J., Buys N. Effects of probiotics consumption on lowering lipids and CVD risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Annals of Medicine. 2015;47(6):430–440. doi: 10.3109/07853890.2015.1071872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sherwin E., Dinan T. G., Cryan J. F. Recent developments in understanding the role of the gut microbiota in brain health and disease. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2018;1420(1):5–25. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jayashree B., Bibin Y. S., Prabhu D., et al. Increased circulatory levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and zonulin signify novel biomarkers of proinflammation in patients with type 2 diabetes. Molecular and Cellular Biochemistry. 2014;388(1-2):203–210. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1911-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roager H. M., Licht T. R. Microbial tryptophan catabolites in health and disease. Nature Communications. 2018;9(1):p. 3294. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05470-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rizzetto L., Fava F., Tuohy K. M., Selmi C. Connecting the immune system, systemic chronic inflammation and the gut microbiome: the role of sex. Journal of Autoimmunity. 2018;92:12–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2018.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mulders R. J., de Git K. C. G., Schéle E., Dickson S. L., Sanz Y., Adan R. A. H. Microbiota in obesity: interactions with enteroendocrine, immune and central nervous systems. Obesity Reviews. 2018;19(4):435–451. doi: 10.1111/obr.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1: the search strategy.

Figure S1: the funnel plots of effect of probiotics on (A) body weight; (B) BMI; (C) BMI modified by the “trim and fill” method; (D) waist circumference; (E) fat mass; (F) fat percentage.

Figure S2: the funnel plots of effect of probiotics on (A) total cholesterol; (B) triglyceride; (C) lipoprotein cholesterol.