Abstract

Trading of herbal medicines generates economic opportunities for vulnerable groups living in periurban, rural, and marginalized areas. This study was aimed at identifying medicinal plant species traded in the Limpopo province in South Africa, including traded plant parts, conservation statutes of the species, and harvesting methods used to collect the species. Semistructured questionnaire supplemented by field observation was used to collect data from owners of 35 informal herbal medicine markets in the Limpopo province. A total of 150 medicinal plant products representing at least 79 plant species belonging to 45 botanical families, mainly the Fabaceae (11.4%), Asteraceae (7.6%), and Hyacinthaceae (6.3%), were traded in the study area. Roots (50.0%), bulbs (19.0%), and bark (16.0%) were the most frequently sold plant parts. Some of the traded species which include Alepidea amatymbica, Bowiea volubilis, Brackenridgea zanguebarica, Clivia caulescens, Dioscorea sylvatica, Elaeodendron transvaalense, Encephalartos woodii, Eucomis pallidiflora subsp. pole-evansii, Merwilla plumbea, Mondia whitei, Prunus africana, Siphonochilus aethiopicus, Synaptolepis oliveriana, and Warburgia salutaris are of conservation concern and listed on the South African Red Data List. Findings of this study call for effective law enforcement to curb illegal removal of wild plants especially those species that are at the verge of extinction.

1. Introduction

Research by Olsen [2] and Djordjevic [3] estimated that 70% to 80% of the people in developing countries use raw medicinal plants to meet their primary health care needs. This high percentage is attributed to several factors including limited accessibility, availability, and affordability of modern medicines [4, 5]. Generally, the number of African plant species with therapeutic uses is estimated to be close to 6000 [6]. Therefore, it is not surprising that trading of medicinal plant species through informal herbal medicine markets in Africa has significant socioeconomic importance in various countries, as this enable millions of people to generate incomes [7–17]. Quiroz et al. [16] argued that herbal medicines generate economic opportunities for vulnerable groups living in periurban, rural, and marginalized areas especially women and farmers facing decreasing agricultural incomes. Meke et al. [18] argued that 90% of herbal traders in southern and central Malawi derived more than 50% of their households' income from selling medicinal plants. Similarly, over 61 000 kilograms of nonpowdered medicines valued US$344,882 are traded in informal herbal medicine markets of Tanzania per year [19]. In Morocco, annual revenues generated from export of medicinal plants were US$55.9 million in 2015 [20] and US$174, 227,384 in Egypt [21]. According to van Andel et al. [15], approximately 951 tonnes of crude herbal medicines with an estimated total value of US$7.8 million was traded in Ghana's herbal markets in 2010. Findings from all these aforesaid studies show that trading in medicinal plants play an important socioeconomic role in several Africans countries.

Similarly, trading in medicinal plants also serves as a valuable source of income for several households in different provinces of South Africa. Mander et al. [13] argued that the trade in herbal medicines in South Africa is estimated to generate an income value at about R2.9 billion per year, representing about 5.6% of the National Health budget. For example, in KwaZulu, Natal province, between 20000 and 30000 people, mainly woman make a living from trading over 4000 tonnes of medicinal plant materials valued at R60 million per year [9]. Dold and Cocks [10] found that a total of 166 medicinal plant species estimated to be 525 tonnes and valued about R27 million are traded in the Eastern Cape province annually. In the Limpopo province, research by Botha et al. [22] showed that 70 plant species were traded in Sibasa and Thohoyandou in Vhembe district, Giyani, and Malamulele in Mopani district. Moeng [23] found that each medicinal plant trader in the Limpopo province generated more than R5000 per month. There are concerns that the trade in traditional medicines threatens the wild populations of the utilized species as a result of harvesting pressure [8, 9, 13, 17, 24].

The trade in herbal medicines in South Africa is on a scale that is a cause for concern among researchers, conservation organizations, and traditional healers as the harvesting methods employed are unsustainable [9, 13, 17, 23, 25–31]. The harvesting methods employed by medicinal plant gatherers involve uprooting of whole plants, collection of roots, bulbs, removal of the bark, and cutting of stems and leaves. These harvesting methods are aimed at collecting large quantities of medicinal plants including those that are of conservation concern and in some cases illegally collecting plant materials in protected areas and critically endangered ecosystems. Consequently, the population numbers of these targeted medicinal plants are declining rapidly and some of them are now on the verge of extinction leaving their therapeutic potential unfulfilled. The current study was, therefore, aimed at documenting medicinal plants traded in the Limpopo province, including traded plant parts, conservation statutes of the species, and harvesting methods used to collect the species. This information will provide the insight into commercial trade of medicinal plants in the Limpopo province, information on targeted species, the economic value, and possible ecological impacts of the species.

2. Research Methods

2.1. Study Area and Markets Survey

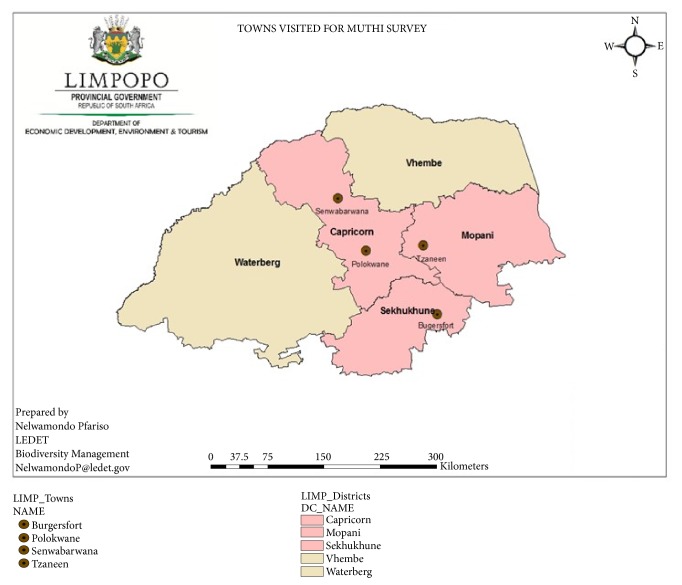

The present study was conducted in all five districts (Capricorn, Mopani, Sekhukhune, Waterberg and Vhembe) of the Limpopo Province of South Africa (Figure 1). In each district, seven informal herbal medicine shops were sampled, resulting in 35 shops visited in the study area. The shop owners who were directly involved in marketing medicinal plants in these shops were interviewed. The participants were informed about the aim and objectives of the study before being requested to sign the consent form. The researchers adhered to the ethical guidelines outlined by the International Society of Ethnobiology (http://www.ethnobiology.net/what-we-do/core-programs/ise-ethics-program/code-of-ethics/). The ethical clearance to conduct this study was obtained from the Limpopo Department of Economic Development, Environment, and Tourism (LEDET) and the survey was conducted from January 2016 to March 2018. Data was gathered using a semistructured interview, which was supplemented by market observations and field visits to determine harvesting methods and habitats of the traded plant species. The latter activity was conducted together with the participants. Other documented information included sociodemographic profiles of the participants, plant parts used, sources of traded plants, and conservation statutes of the documented species.

Figure 1.

Map of the study area indicating surveyed informal herbal medicine shops and districts.

2.2. Plant Specimen Collection and Data Analysis

Dold and Cocks [10] argued that the use of vernacular names to identify taxa traded in informal herbal medicine markets is unreliable as they vary considerably from place to place and even between traders within the same market. Therefore, to positively identify the plant material traded in the sampled herbal medicine markets, we requested traders to accompany us to the field. In this regard, the traders initially identified the plants using their vernacular names and during field trips the voucher specimens of these species were collected and their identities authenticated at the University of Limpopo's Larry-Leach Herbarium. Botanical names and the plant families of the documented species were confirmed using the ‘The Plant List' created by the Missouri Botanical Gardens and the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (http://www.theplantlist.org/).

Information gathered from the interview schedules and field observations was collated and analyzed using Microsoft Excel 2000 and the Statistical Package for the Social Science (SPSS) version 16.0 programme. Descriptive statistics such as percentages frequencies were used. The conservation statutes of traded medicinal plant species were categorized following the IUCN Red List Criteria Version 3.1 (2001). Species can be classified into one of the three categories of threat, that is, Critically Endangered (CR), Endangered (EN), or Vulnerable (VU), or they are placed into Near Threatened (NT), Data Deficient (DD), Extinct (EX), or Extinct in the Wild (EW). If a species does not meet any of these criteria, it is classified as Least Concern (LC). A species classified as LC can additionally be flagged as being of conservation concern either as Rare, Critically Rare, or Declining [32, 33].

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sociodemographic Profiles of Participants

The majority (n=33, 94.2%) of medicinal plants traders interviewed in this study were men, and females constituted 5.7% (n=2). The predominance of men in trading herbal medicines is common in Malawi [18], South Africa [22], and Tanzania [19]. However, Mander et al. [13] found that the majority of medicinal plant traders in the Gauteng, Mpumalanga and KwaZulu-Natal provinces of South Africa were women. Ndawonde et al. [34] found that 77% of the 63 plant traders interviewed in KwaZulu-Natal province were women. Results of the current study revealed that the male participants were the custodians of the species traded in the province and the associated indigenous knowledge, innovations, and practices. These findings corroborate the observation made by Cunningham [7] that the commercially sold medicinal plants are an important feature of the cultural, medicinal, economical, and ecological component of every city in the world.

Close to three quarters of the participants (n = 24, 68.5%) were between 31 and 40 years and 20% (n = 7) were between 21 and 30 years while 11.4% (n = 4) were between 41 and 50 years. Therefore, increasing trade in the medicinal plants is expected in the Limpopo province in the future as the majority of the participants were within the very active age group. More than half of the participants (n = 22, 62.8%) were educated up to secondary education, while 22.8% (n = 8) and 14.2% (n = 5) had attained tertiary and primary education, respectively. The importance of medicinal plants and the need to trade them in the Limpopo province were ubiquitously perceived, with all participants claiming to generate adequate profit to meet their basic livelihood needs and being optimistic about the future of the medicinal plants trade in the province. More than three quarters of the participants (n = 27, 77.1%) earned monthly incomes of between R3000 and R4000.00. The rest of the participants earned monthly incomes of less than R3000 (n = 5, 14.2%) or more than R5 000 (n = 3, 8.5%). The findings of this study emphasize the contribution of herbal medicines trade towards participants' livelihood needs, source of primary health care products, and cultural heritage corroborating research by Mander et al. [13] who argued that trade in herbal medicines in South Africa is a large and growing industry which is important to the national economy.

3.2. Diversity of Traded Medicinal Plants

A total of 150 medicinal plant products representing at least 79 plant species were recorded in the surveyed informal herbal medicine shops in the Limpopo province (Table 1). A total of 79 species belonging to 45 botanical families, mainly the Fabaceae (n = 9 spp., 11.4%), Asteraceae (n = 6 spp., 7.6%), Hyacinthaceae (n = 5 spp., 6.3%), Amaryllidaceae (n = 4 spp., 5.1%), Celastraceae, Ebenaceae, and Gentianaceae (n = 3 spp., 3.8% each) were positively identified and, therefore, further analyses were based on these species. The rest of the medicinal plant products were excluded in the current study because they were not positively identified due to lack of diagnostic features such as leaves and fruiting material such as flowers and fruits. Previous studies showed that plant species belonging to Fabaceae (13.0%), Apocynaceae (5.7%), Phyllanthaceae (4.9%), and Rubiaceae (4.1%) were the most traded species in Malawi [18], while Fabaceae (7.4%), Asteraceae (6.7%), and Euphorbiaceae (5.5%) were the most traded taxa in South Africa [27] while Asteraceae and Fabaceae (10.6% each), Euphorbiaceae (8.5%) and Cucurbitaceae (6.4%) were the most traded taxa in Botswana [14]. Plant families Apocynaceae, Asteraceae, Cucurbitaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Fabaceae, Phyllanthaceae, and Rubiaceae have the highest number of traded species as herbal medicines probably because these are large families characterized by several species, at least 989 species each (http://www.theplantlist.org/).

Table 1.

List of plants recorded in informal herbal medicine markets in the Limpopo province, South Africa.

| Family | Scientific name | Habit | Conservation status | Part used | Medicinal uses | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acanthaceae | Sclerochiton ilicifolius A. Meeuse | Tree | LC | Roots | Hypertension and malaria | 28.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Amaryllidaceae | Clivia caulescens R.A. Dyer | Herb | NT | Roots | Police evasion | 54.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Amaryllidaceae | Boophone disticha (L.f.) Herb. | Herb | LC | Bulb | Cancer, diabetes mellitus and kidney problem | 25.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Amaryllidaceae | Ammocharis coranica (Ker Gawl.) Herb. | Herb | LC | Bulb | Hypertension and blood cancer | 25.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Amaryllidaceae | Clivia miniata var. citrina | Herb | DDT | Bulb | Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), arthritis, skin disorder and tuberculosis | 22.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Anacampserotaceae | Talinum caffrum (Thunb.) Eckl. & Zeyh | Herb | LC | Roots | Eye disorder | 14.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Anacampserotaceae | Talinum crispatulum Dinter | Herb | LC | Roots | Kidney and womb problem | 25.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Anacardiaceae | Protorhus longifolia (Bernh.) Engl | Tree | LC | Bark | Tooth decay and bad breath, laxative and poison/kill people | 22.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Anacardiaceae | Lannea schweinfurthii (Engl) Engl var. stuhlmannii (Engl) | Tree | LC | Roots | Cause memory loss and increase milk production in pregnant woman | 25.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Annonaceae | Annona senegalensis Pers. | Tree | LC | Roots | Chlamydia and malaria | 8.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Apiaceae | Alepidea amatymbica Eckl. & Zeyh. | Herb | EN | Roots and whole plant | To attract customers and protection from theft, flu and colds and diabetes | 100.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Apocynaceae | Acokanthera rotundata (Codd) Kupicha | Tree | LC | Bark | Headache and sinusitis | 11.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Apocynaceae | Mondia whitei (Hook.f.) Skeels | Herb | EN | Roots and fruits | Stamina and diabetes | 5.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Araceae | Stylochaeton natalensis Schott | Herb | LC | Roots | Waist pain in men | 25.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Araceae | Zantedeschia aethiopica (L.) Spreng. | Herb | LC | Roots | Chlamydia and measles | 5.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Asparagaceae | Asparagus aethiopicus L. | Herb | LC | Roots | Attract customers and skin protection for people living with albinism | 22.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Asteraceae | Callilepis salicifolia Oliv. | Herb | LC | Roots | Flu, cough and stomach ache | 2.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Asteraceae | Callilepsis laureola DC. | Herb | LC | Tuber | Tuberculosis and asthma | 54.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Asteraceae | Dicoma anomala Sond. | Herb | LC | Tuber | Tuberculosis and flu | 8.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Asteraceae | Helichrysum cymosum (L.) D. Don subsp. calvum Hilliard | Shrub | LC | Whole plant | Asthma, call ancestors, cough and tuberculosis | 5.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Asteraceae | Senecio gregatus Hilliard | Shrub | LC | Leaves | Body cleansing | 22.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Asteraceae | Senecio serratuloides DC. | Shrub | LC | Leaves | Body cleansing and HIV symptoms | 22.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Brassicaceae | Capparis sepiaria L. var. subglabra (Oliv) DeWolf | Shrub | LC | Roots | Protection from lightning and nose bleed | 2.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Canellaceae | Warburgia salutaris (G.Bertol.) Chiov. | Tree | EN | Bark | Asthma, blood disorders, impotency, skin disorders, sores and tuberculosis | 100.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Capparaceae | Capparis tomentosa Lam. | Shrub | LC | Bark | Home protection | 11.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Caryophyllacea | Dianthus basuticus Burtt | Herb | LC | Roots | Win court cases | 22.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Celastraceae | Catha edulis (Vahl) Forssk ex Endl | Tree | LC | Leaves | Energy booster and stamina | 14.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Celastraceae | Elaeodendron transvaalense (Burtt) R H Archer | Tree | NT | Bark | Tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections (STI) | 2.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Celastraceae | Pleurostylia capensis (Turcz.) Loes. | Tree | LC | Roots | Eyes disorders and mental illnesses | 28.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Clusiaceae | Garcinia gerrardii Harv. ex Sim | Tree | LC | Roots | Lack of appetite | 20.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Combretaceae | Combretum molle R.Br. ex G.Don | Tree | LC | Roots | Skin disorders and tuberculosis | 8.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Commelinaceae | Commelina subulata Roth | Herb | LC | Seeds | Cause memory loss | 5.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Dioscoreaceae | Dioscorea sylvatica Eckl. | Herb | VU | Bulb | Foot disorder and body pains | 54.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Dioscoreaceae | Dioscorea dregeana (Kunth) T Durand & Schinz | Herb | LC | Tuber | Foot disorder, body pains, malaria and to oppress opponents | 54.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Dipsacaceae | Scabiosa columbaria L. | Herb | LC | Roots | Assist people to stop drinking alcohol, quench thirst and oral infections | 20.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Ebenaceae | Diospyros lycioides Desf subsp sericea (Bernh) De Winter | Tree | LC | Roots | Cancer, chest pains and STI | 11.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Ebenaceae | Euclea crispa (Thunb.) Gürke subsp. crispa | Tree | LC | Roots | Stomach ailments | 22.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Ebenaceae | Diospyros galpinii (Hiern) De Winter | Shrub | LC | Roots | Body cleansing and laxative | 2.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Fabaceae | Vigna frutescens A Rich subsp frutescens var. frutescens | Herb | LC | Roots | Stomach ailments and diarrhoea | 20.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Fabaceae | Pterocarpus angolensis DC. | Tree | LC | Bark | Used to cause harm/death | 22.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Fabaceae | Erythrina lysistemon Hutch. | Tree | LC | Bark | Cancer, cough, malaria, tuberculosis and skin rash | 5.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Fabaceae | Peltophorum africanum Sond. | Tree | LC | Bark | Cleanse body, treat bad luck and HIV symptoms | 20.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Fabaceae | Mundulea sericea (Willd.) A. Chev. | Tree | LC | Bark | Tuberculosis and menstrual disorders | 20.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Fabaceae | Albizia adianthifolia (Shumach.) W. Wight | Tree | LC | Bark | Mental illnesses, sores and malaria | 11.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Fabaceae | Elephantorrhiza elephantina (Burch.) Skeels | Shrub | LC | Roots | Blood disorders, diarrhoea, HIV symptoms and purgative | 17.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Gentianaceae | Enicostema axillare (Lam.) A.Raynal subsp. Axillare | Herb | LC | Whole plant | Diabetes | 100.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Geraniaceae | Pelargonium capitatum (L.) L'Hér. | Herb | LC | Roots | Menstrual pains and labour pains | 17.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Geraniaceae | Monsonia angustifolia Sond. | Herb | LC | Whole plant | Diabetes, hypertension, body cleansing, impotency and increase appetite | 100.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Hyacinthaceae | Drimia elata Jacq. | Herb | DDT | Bulb | Blood related ailments, periods pains and womb problem | 100.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Hyacinthaceae | Merwilla plumbea (Lindl.) Speta | Shrub | NT | Bulb | Body cleansing, skin rash in babies and promote vomiting of impure milk in babies | 14.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Hyacinthaceae | Urginea sanguinea Shinz | Herb | LC | Bulb | Hypertension, diabetes, blood clotting, body pains and STI | 20.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Hyacinthaceae | Eucomis autumnalis (Mill.) Chitt | Herb | LC | Bulb | Body pains, hypertension and STI | 100.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Hyacinthaceae | Eucomis pallidiflora Baker subsp pole-evansii (N E Br) Reyneke ex J C Manning | Herb | NT | Bulb | Body pains, hypertension, malaria, STI and tuberculosis | 17.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Hypoxidaceae | Hypoxis obtusa Burch. ex Ker Gawl. | Herb | LC | Bulb | Blood disorders, diabetes, hypertension and infertility | 34.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Hypoxidaceae | Hypoxis hemerocallidea Fisch, C A Mey & Avé-Lall | Herb | LC | Tuber | Cancer, diabetes, energy booster, hypertension, tuberculosis, infertility and HIV | 100.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Icacinaceae | Pyrenacantha grandiflora Baill. | Shrub | LC | Roots | Eye disorders and body pains | 20.0 |

|

| ||||||

| Kirkiaceae | Kirkia wilmsii Engl | Tree | LC | Bulb | Arthritis, diabetes, hypertension and quench thirst | 11.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Liliaceae | Bowiea volubilis Harv. ex Hook.f. | Herb | VU | Bulb | Blood disorder, cancer and good luck | 54.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Malvaceae | Dombeya rotundifolia Hochst. | Tree | LC | Roots | Diarrhoea and stomach ailments | 8.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Malvaceae | Adansonia digitata L. | Tree | LC | Bark | Stamina, infertility, impotency and respiratory infections | 14.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Meliaceae | Ekebergia capensis Sparrm. | Tree | LC | Roots | Blood cancer and STI | 11.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Meliaceae | Trichilia emetica Vahl subsp. Emetic | Tree | LC | Roots | Body cleansing | 5.7 |

|

| ||||||

| Molluginaceae | Psammotropha marginata (Thunb.) Druce | Herb | DDT | Roots | Eyes disorders and body pains | 17.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Moraceae | Ficus ingens (Miq.) Miq. | Tree | LC | Bark | Sores and stomach disorders | 14.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Myrsinaceae | Rapanea melanophloeos (L.) Mez | Tree | LC | Roots | Cancer, wounds and womb problem | 8.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Olacaceae | Ximenia caffra Sond var. caffra | Tree | LC | Roots | Stomach disorders | 17.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Oleaceae | Olea europaea L subsp. africana (Mill) P S Green | Tree | LC | Roots | Facilitate birth, cough and tuberculosis | 8.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Passifloraceae | Adenia spinosa Burtt Davy | Shrub | LC | Bulb | Bath a baby to promote weight gain | 14.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Polygalaceae | Securidaca longepedunculata Fresen. | Tree | LC | Roots | Cough, flu, improve men's fertility and impotency | 57.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Rhamnaceae | Ziziphus mucronata Willd. subsp. mucronata | Tree | LC | Roots | Cough, STI, sores, tuberculosis and wounds | 14.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Rosaceae | Prunus africana (Hook.f.) Kalkman | Tree | VU | Bark | Colds, cough, flu, HIV, stomach complaints and tuberculosis | 11.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Rutaceae | Zanthoxylum capense (Thunb.) Harv. | Tree | LC | Roots | Asthma, colds, cough, fix bad situations, flu, sores and tuberculosis | 62.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Rutaceae | Brackenridgea zanguebarica Oliv. | Tree | CR | Roots | Reverse bad luck, protect household and protection from evil spirits | 57.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Santalaceae | Osyris lanceolata Hochst. & Steud. | Tree | LC | Roots | Attract a woman/man, cause harm/death to people, strengthen a household, reproductive problems and malaria | 28.6 |

|

| ||||||

| Thymelaeacea | Lasiosiphon caffer Meisn. | Herb | LC | Roots | Asthma, colds, cough and tuberculosis | 14.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Thymelaeaceae | Synaptolepis oliveriana Gilg | Shrub | NT | Roots | Good luck | 14.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Vitaceae | Rhoicissus tomentosa (Lam) Wild & R B Drummund | Herb | LC | Roots | Cancer, cough and tuberculosis | 17.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Zamiaceae | Encephalartos woodii Sander | Tree | EW | Bulb | Protection against harm | 2.9 |

|

| ||||||

| Zingiberaceae | Siphonochilus aethiopicus (Schweinf.) B.L.Burtt | Herb | CR | Bulb | Asthma, colds, cough, body pains, flu, HIV symptoms and good luck | 100.0 |

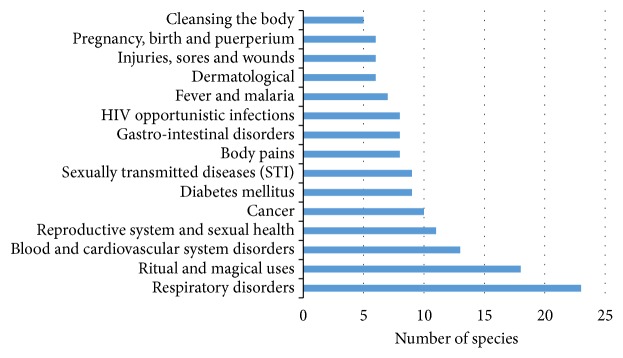

Analysis of traded plant species showed that herbs and trees (n = 34, 43% each) and shrubs (n = 11, 13.9%) were the most traded growth forms. Previous research in the Limpopo province carried out by Botha et al. [22] showed that trees, shrubs, herbs, climbers, and geophytes were the most traded growth forms in the province. More than half of the traded species (n = 67, 84.8%) were prescribed for more than one ailment and just 15.1% (n = 12) were sold as herbal medicine for a single ailment (Table 1). Previous studies conducted in the Limpopo [23, 35], Kwa-Zulu Natal [34], and the Northern Cape [36] provinces in South Africa also found that informal herbal medicine traders mainly sold species with multiple medicinal applications. The medicinal applications of the traded species were classified into 15 major medical categories following the Economic Botany Data Collection Standard [1] with some changes proposed by Macía et al. [37] and Gruca et al. [38]. These categories included respiratory disorders, ritual and magical uses, blood and cardiovascular system disorders, reproductive system and sexual health disorders, cancer, diabetes, sexually transmitted infections (STI), body pains, gastrointestinal system disorders, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) opportunistic infections, fever and malaria, dermatological problems, injuries, sores and wounds, pregnancy, birth and puerperium, and cleansing of the body (Figure 2). The species traded in the Limpopo province are used as herbal medicine against several diseases categorized by Stats SA [39] as the top killer diseases in South Africa in 2016 which include tuberculosis, heart diseases, HIV diseases, influenza, diabetes mellitus, and other viral diseases. Over the years, there have been numerous studies that have validated the traditional uses of some of the traded medicinal plants against the top killer diseases.

Figure 2.

Medicinal categories of traded medicinal plants in the Limpopo province following the Economic Botany Data Collection Standard [1].

3.3. Highly Traded Species

The most frequently traded plant species, recorded in 28.6% of the informal herbal medicine shops, included the following (in ascending order of importance): Osyris lanceolata Hochst. and Steud., Pleurostylia capensis (Turcz.) Loes., Sclerochiton ilicifolius A. Meeuse, Hypoxis obtusa Burch. ex Ker Gawl., Bowiea volubilis Harv. ex Hook.f., Callilepsis laureola DC., Clivia caulescens R.A. Dyer, Dioscorea sylvatica Eckl., Dioscorea dregeana (Kunth) T Durand and Schinz, Brackenridgea zanguebarica Oliv., Securidaca longepedunculata Fresen., Zanthoxylum capense (Thunb.) Harv., Alepidea amatymbica Eckl. and Zeyh., Drimia elata Jacq., Enicostema axillare (Lam) A Raynal subsp. axillare, Eucomis autumnalis (Mill) Chitt., Hypoxis hemerocallidea Fisch, C A Mey and Avé-Lall, Monsonia angustifolia Sond., Siphonochilus aethiopicus (Schweinf) B L Burtt, and Warburgia salutaris (G Bertol) Chiov (Tables 1 and 2). More than half of the participants indicated that the following species were in high demand but not readily available in the wild or rare or their populations declining (Table 2): Bowiea volubilis, Clivia caulescens, Dioscorea sylvatica, Dioscorea dregeana, Brackenridgea zanguebarica, Alepidea amatymbica, Eucomis autumnalis, Siphonochilus aethiopicus, and Warburgia salutaris. With the exception of Dioscorea dregeana and Eucomis autumnalis these species are listed on the South African Red Data List as threatened plant species (Table 1), with Brackenridgea zanguebarica and Siphonochilus aethiopicus listed as Critically Endangered, Alepidea amatymbica and Warburgia salutaris listed as Endangered, and Bowiea volubilis and Dioscorea sylvatica listed as Vulnerable while Clivia caulescens is listed as Near Threatened [40]. Six other plant species that are traded in the study area but not categorized as high in demand by the participants which are of conservation concern in South Africa and listed on the South African Red Data List include the following (Table 1): Encephalartos woodii Sander which is listed as Extinct in the Wild; Mondia whitei (Hook.f.) Skeels is listed as Endangered; Prunus africana (Hook.f.) Kalkman is listed as Vulnerable while Elaeodendron transvaalense (Burtt) R H Archer, Merwilla plumbea (Lindl.) Speta, Eucomis pallidiflora Baker subsp. pole-evansii (N E Br) Reyneke ex J C Manning, and Synaptolepis oliveriana Gilg are listed as Near Threatened [40]. Interviews with participants revealed that Alepidea amatymbica, Bowiea volubilis, Brackenridgea zanguebarica, Clivia caulescens, Dioscorea sylvatica, Dioscorea dregeana, Eucomis autumnalis, Sclerochiton ilicifolius, Siphonochilus aethiopicus, and Warburgia salutaris which were regarded as popular and harvested from the wild were becoming locally extinct and these species fetched high prices (Table 2). All these 14 species that are traded in the Limpopo province but listed on the South African Red Data List are in general overcollected as herbal medicines and extracted at unsustainable rate throughout their distributional ranges [40].

Table 2.

The most frequently traded medicinal plants in the Limpopo province.

| Species name | Availability in herbal medicine shops during survey | Demand | Availability in the wild | Price range ZAR (USD)/kg∗ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alepidea amatymbica | Yes (n = 15, 42.9%) | High (n = 35, 100.0%) | Not available (n = 22, 62.9%) | 30.00 (2.30) |

| Out of stock (n = 20, 57.1%) | Rare (n = 8, 22.9%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Enicostema axillare | Yes (n = 35, 100.0%) | High (n = 35, 100.0%) | Abundant (n = 35, 100.0%) | 15.00 (1.15) |

|

| ||||

| Eucomis autumnalis | Yes (n = 29, 82.9%) | High (n = 35, 100.0%) | Declining (n = 22, 62.9%) | 27.50 (2.12) |

| Out of stock (n = 6, 17.1%) | Rare (n = 9, 25.7%) | |||

| Not available (n = 1, 2.9%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Hypoxis hemerocallidea | Yes (n = 21, 60.0%) | High (n = 35, 100.0%) | Abundant (n = 33, 94.3%) | 15.00 (1.15) |

| Out of stock (n = 14, 40.0%) | Declining (n = 2, 5.7%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Monsonia angustifolia | Yes (n = 30, 85.7%) | High (n = 35, 100.0%) | Abundant (n = 30, 85.7%) | 22.50 (1.73) |

| Out of stock (n = 5, 14.3%) | Declining (n = 5, 14.3%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Drimia elata | Yes (n = 22, 62.9%) | High (n = 35, 100.0%) | Abundant (n = 35, 100.0%) | 12.50 (0.96) |

| Out of stock (n = 13, 37.1%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Siphonochilus aethiopicus | Yes (n = 19, 54.3%) | High (n = 35, 100.0%) | Not available (n = 32, 91.4%) | 8.50 (0.65) |

| Out of stock (n = 16, 45.7%) | Rare (n = 3, 8.6%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Warburgia salutaris | Yes (n = 31, 88.6%) | High (n = 35, 100.0%) | Declining (n = 29, 82.9%) | 27.50 (2.12) |

| Out of stock (n = 4, 11.4%) | Rare (n = 6, 17.1%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Zanthoxylum capense | Yes (n = 11, 31.4%) | High (n = 22, 62.9%) | Abundant (n = 22, 62.9%) | 27.50 (2.12) |

| Out of stock (n = 11, 31.4%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Securidaca longepedunculata | Yes (n = 9, 25.7%) | High (n = 20, 57.1%) | Abundant (n = 19, 54.3%) | 22.50 (1.73) |

| Out of stock (n = 11, 31.4%) | Declining (n = 1, 2.9%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Brackenridgea zanguebarica | Yes (n = 7, 20.0%) | Moderate (n = 13, 37.1%) | Abundant (n = 2, 5.7%) | 27.50 (2.12) |

| Out of stock (n = 13, 37.1%) | High (n = 7, 20.0%) | Not available (n = 18, 51.4%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Callilepsis laureola | Yes (n = 15, 42.9%) | Low (n = 18, 51.4%) | Abundant (n = 18, 51.4%) | 12.50 (0.96) |

| Out of stock (n = 4, 11.4%) | Moderate (n = 1, 2.9%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Bowiea volubilis | Yes (n = 9, 25.7%) | High (n = 16, 45.7%) | Rare (n = 14, 40.0%) | 12.50 (0.96) |

| Out of stock (n = 10, 26.6%) | Moderate (n = 3, 8.6%) | Not available (n = 5, 14.3%) | ||

|

| ||||

| Dioscorea dregeana | Yes (n = 5, 14.3%) | High (n = 11, 31.4%) | Declining (n = 17, 48.6%) | 27.50 (2.12) |

| Out of stock (n = 14, 40.0%) | Moderate (n = 6, 17.1%) | Rare (n = 2, 5.7%) | ||

| Low (n = 2, 5.7%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Dioscorea sylvatica | Yes (n = 6, 17.1%) | High (n = 19, 54.3%) | Rare (n = 11, 31.4%) | 27.50 (2.12) |

| Out of stock (n = 13, 37.1%) | Not availableE (n = 8, 22.9%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Clivia caulescens | Yes (n = 17, 48.6%) | High (n = 9, 25.7%) | Declining (n = 16, 45.7%) | 12.50 (0.96) |

| Out of stock (n = 2, 5.7%) | Moderate (n = 6, 17.1%) | Rare (n = 2, 5.7%) | ||

| Low (n = 4, 11.4%) | Abundant (n = 1, 2.9%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Croton gratissimus | Yes (n = 15, 42.9%) | Low (n = 15, 42.9%) | Abundant (n= 15, 42.9%) | 12.50 (0.96) |

|

| ||||

| Hypoxis obtusa | Yes (n = 11, 31.4%) | High (n = 9, 25.7%) | Abundant (n = 9, 25.7%) | 12.50 (0.96) |

| Out of stock (n = 2, 5.7%) | Moderate (n = 3, 8.6%) | Declining (n = 4, 11.4%) | ||

| Low (n = 1, 2.9%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Osyris lanceolata | Yes (n = 7, 20.0%) | High (n = 1, 2.9%) | Abundant (n = 7, 20.0%) | 12.50 (0.96) |

| Out of stock (n = 3, 8.6%) | Declining (n = 3, 8.6%) | |||

|

| ||||

| Pleurostylia capensis | Yes (n = 1, 2.9%) | High (n = 10, 28.6%) | Abundant (n = 10, 28.6%) | 22.50 (1.73) |

| Out of stock (n = 9, 25.7%) | ||||

|

| ||||

| Sclerochiton ilicifolius | Yes (n = 8, 22.9%) | High (n = 10, 28.6%) | Declining (n = 7, 20.0%) | 22.50 (1.73) |

| Out of stock (n = 2, 5.7%) | Rare (n = 3, 8.6%) | |||

∗An average exchange rate for 2018 of USD1 = ZAR13.00 was used.

About three quarters of the participants (n = 26, 74.2%) did not have plant collecting permits as required by law in South Africa [41]. Only a quarter of the participants (n = 9, 25.7%) were in possession of a general plant collecting permit allowing them to collect any medicinal plants in the wild, without stating the quotas of materials to be harvested, use of sustainable harvesting techniques, and restrictions on the collection of threatened and protected plants. According to Retief et al. [42] a Threatened or Protected Species (TOPS) permit in terms of the National Environmental Management: Biodiversity Act (NEM:BA) of 2004 is required to collect and possess the following species which were traded by the participants and listed on the South African Red Data List: Alepidea amatymbica, Bowiea volubilis, Brackenridgea zanguebarica, Clivia caulescens, Dioscorea sylvatica, Elaeodendron transvaalense, Encephalartos woodii, Eucomis pallidiflora subsp. pole-evansii, Merwilla plumbea, Mondia whitei, Prunus africana, Siphonochilus aethiopicus, Synaptolepis oliveriana, and Warburgia salutaris. None of the participants had a TOPS permit, therefore, these species were being illegally harvested by the participants. Findings of this study call for effective law enforcement to curb illegal removal of wild plants especially those species that are at the verge of extinction.

Interviews with participants revealed that common key factors that were considered in determining the price of the traded species included demand and availability of the species and also whether the plant material being sold is raw material or partially processed (Table 2). Prices of traded species ranged from ZAR8.50 (USD0.65) to ZAR30.00 (USD2.30) (Table 2). Plant species which were sold for more than ZAR26.00 (USD2.00) included the following (in ascending order of importance): Brackenridgea zanguebarica, Dioscorea dregeana, Dioscorea sylvatica, Eucomis autumnalis, Warburgia salutaris, Zanthoxylum capense, and Alepidea amatymbica (Table 2). Prices recorded in the Limpopo province were lower than prices recorded by Dold and Cocks [10] in the Eastern Cape province for Alepidea amatymbica, Bowiea volubilis, and Dioscorea sylvatica with prices ranging from ZAR14.90 (USD1.90) to ZAR82.40 (USD10.30). Mander et al. [13] argued that there is increasing harvesting pressure on traditional supply areas leading to a growing shortage in supply of popular medicinal plant species which are sustaining livelihoods and providing important health care services to local communities.

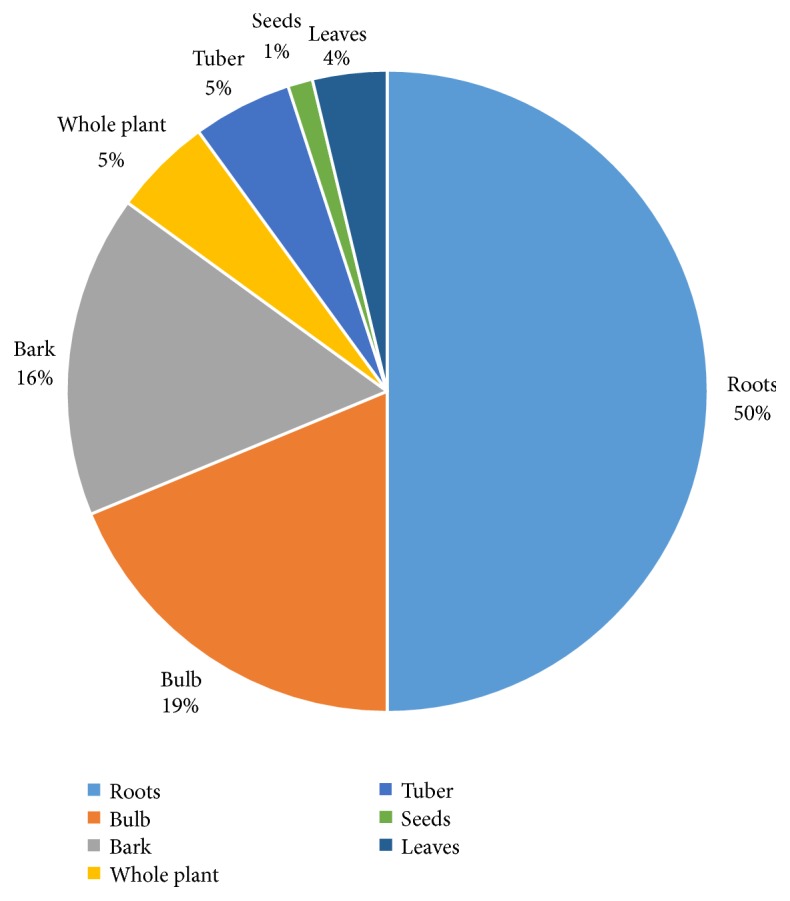

3.4. Traded Plant Parts

The plant parts traded as herbal medicines in the Limpopo provinces were the bark, bulbs, leaves, roots, seeds, tubers, and whole plant. The roots were the most frequently traded (50.0%), followed by bulbs (19.0%), bark (16.0%), tubers and whole plants (5.0% each), leaves (4.0%), and seeds (1.0%) (Figure 3). The bulbs, tubers, and whole plant were mostly from geophytes and herbaceous plant species (Table 1). However, harvesting of roots of herbaceous plants for medicinal purposes, bark, bulbs, and whole plant is not sustainable as it threatens the survival of the plant species used as herbal medicines. It is well recognized by conservationists that medicinal plants primarily valued for their bark, bulbs, roots, stems, and tubers and as whole plants are often overexploited and threatened [24].

Figure 3.

Medicinal plant parts traded in the Limpopo province.

4. Conclusion

Medicinal plants are globally valuable sources of pharmaceutical drugs and other health products, but they are disappearing at an alarming rate [24]. Several plant species used as herbal medicines in the Limpopo province are threatened with extinction from overharvesting due to popularity of the species in the herbal medicine markets. Although this threat has been known for decades, the accelerated loss of species and habitat destruction in the province has increased the risk of extinction of medicinal plants in the country. The illegal acquisition of some plant species especially those listed on the South African Red Data List from wild populations is the principle threat to their persistence. There is need, therefore, to educate local communities on the contemporary environmental legislation, at the same time emphasizing the need to retain traditional knowledge on medicinal plant utilization in the province.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank herbal medicine traders for sharing their knowledge. This study was financially supported by the Limpopo Department of Economic Development, Environment and Tourism (LEDET), National Research Foundation (NRF), South Africa and Govan Mbeki Research and Development Centre (GMRDC), and University of Fort Hare.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cook C. E. M. Economic Botany Data Collection Standard, Prepared for the International Working Group on Taxonomic Databases for Plant Sciences (TDWG) London, UK: Kew Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olsen C. S. The trade in medicinal and aromatic plants from Central Nepal to Northern India. Economic Botany. 1998;52(3):279–292. doi: 10.1007/BF02862147. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djordjevic S. M. From medicinal plant raw material to herbal remedies. In: El-Shemy H. A., editor. Aromatic and Medicinal Plants: Back to Nature, Chapter 16. 2018. pp. 269–288. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasilo O., Trapsida J.-M. Regulation of Traditional Medicine in the WHO African Region. https://www.aho.afro.who.int/en/ahm/issue/13/reports/regulation-traditionalmedicine-who-african-region.

- 5.Shewamene Z., Dune T., Smith C. A. The use of traditional medicine in maternity care among African women in Africa and the diaspora: a systematic review. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2017;17(382) doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1886-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schmelzer G. H., Gurib-Fakim A. Plant Resources of Tropical Africa (PROTA) 11(1): Medicinal Plants 1. Wageningen, Netherlands: PROTA Foundation; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham A. B. African Medicinal Plants: Setting Priorities at the Interface between Conservation and Primary Health Care, People and Plants Working Paper 1. Paris, France: UNESCO; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cunningham A. B. People, Park and Plant Use: Recommendations for Multiple-use Zones and Alternatives Around Bwindi-Impenetrable National Park, Uganda, People and Plants Working Paper 4. Paris, France: UNESCO; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mander M. Marketing of Indigenous Medicinal Plants in South Africa: A Case Study in KwaZulu-Natal. Rome, Italy: FAO; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dold A. P., Cocks M. L. The trade in medicinal plants in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. South African Journal of Science. 2002;98(11-12):589–597. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hamilton A. C. Medicinal plants, conservation and livelihoods. Biodiversity and Conservation. 2004;13(8):1477–1517. doi: 10.1023/b:bioc.0000021333.23413.42. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kepe T. Medicinal plants and rural livelihoods in Pondoland, South Africa: towards an understanding of resource value. International Journal of Biodiversity Science and Management. 2007;3(3):170–183. doi: 10.1080/17451590709618171. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mander M., Ntuli L., Diedrichs N., Mavundla K. Economics of the traditional medicine trade in South Africa. In: Harrison S., Bhana R., Ntuli A., editors. South African Health Review. Durban, South Africa: Health Systems Trust; 2007. pp. 189–200. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Setshogo M. P., Mbereki C. M. Floristic diversity and use of medicinal plants sold by street vendors in Gaborone, Botswana. The African Journal of Plant Science and Biotechnology. 2011;5(1):69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Andel T., Myren B., van Onselen S. Ghana's herbal market. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2012;140(2):368–378. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Quiroz D., Towns A., Legba S. I., et al. Quantifying the domestic market in herbal medicine in Benin, West Africa. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;151(3):1100–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2013.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petersen L. M., Charman A. J. E., Moll E. J., Collins R. J., Hockings M. T. Bush doctors and wild medicine: the scale of trade in Cape Town's informal economy of wild-harvested medicine and traditional healing. Society and Natural Resources: An International Journal. 2014;27(3):315–336. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meke G. S., Mumba R. F. E., Bwanali R. J., Williams V. L. The trade and marketing of traditional medicines in southern and central Malawi. International Journal of Sustainable Development & World Ecology. 2017;24(1):73–87. doi: 10.1080/13504509.2016.1171261. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Posthouwer C. Medicinal Plants of Kariakoo Market, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania [MSc dissertation] Leiden, Netherlands: Leiden University; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Market Insider. Economic Importance of Moroccan Medicinal Plant Exports. 2015, http://www.intracen.org/blog/Economic-importance-of-Moroccan-medicinal-plant-exports/

- 21.Abdel-Azim N. S., Shams K. A., Shahat A. A. A., El Missiry M. M., Ismail S. I., Hammouda F. M. Egyptian herbal drug industry: challenges and future prospects. Research Journal of Medicinal Plant. 2011;5(2):136–144. doi: 10.3923/rjmp.2011.136.144. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Botha J., Witkowski E. T. F., Shackleton C. M. Market profiles and trade in medicinal plants in the Lowveld, South Africa. Environmental Conservation. 2004;31(1):38–46. doi: 10.1017/S0376892904001067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moeng T. E. An Investigation Into the Trade of Medicinal Plants by Muthi Shops and Street Vendors in the Limpopo Province, South Africa [MSc dissertation] Sovenga, South Africa: University of Limpopo; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams V. L., Victor J. E., Crouch N. R. Red listed medicinal plants of South Africa: Status, trends, and assessment challenges. South African Journal of Botany. 2013;86:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2013.01.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cuningham A. B. Imithi isiZulu: The Traditional Medicine Trade in KwaZulu-Natal [MSc dissertation] Pietermaritzburg, South Africa: KwaZulu-Natal, University of Natal; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kowalski B., van Staden J. In vitro culture of two threatened South African medicinal trees: Ocotea bullata and Warburgia salutaris. Plant Growth Regulation. 2001;34(2):223–228. doi: 10.1023/A:1013362615531. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Williams V. L., Balkwill K., Witkowski E. T. F. A lexicon of plants traded in the Witwatersrand umuthi shops, South Africa. Bothalia. 2001;31(1):71–98. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams V. L. Gauteng Directorate of Nature Conservation. Johannesburg, South Africa: Gauteng; 2003. Hawkers of health: an investigation of the faraday street traditional medicine market in johannesburg, gauteng, Technical Report. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loundou P. M. Medicinal plant trade and opportunities for sustainable management in the Cape Peninsula, South Africa [MSc dissertation] Cape Town, South Africa: University of Stellenbosch; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moeng T. E., Potgieter M. J. The trade of medicinal plants by muthi shops and street vendors in the Limpopo Province, South Africa. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2011;5(4):558–564. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Semenya S. S., Potgieter M. J., Erasmus L. J. C. Indigenous plant species used by Bapedi healers to treat sexually transmitted infections: their distribution, harvesting, conservation and threats. South African Journal of Botany. 2013;87:66–75. doi: 10.1016/j.sajb.2013.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Victor J. E., Keith M. The orange list: a safety net for biodiversity in South Africa. South African Journal of Science. 2004;100(3-4):139–141. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Von Staden L., Raimondo D., Foden W. Approach to red list assessments. In: Raimondo D., Von Staden L., Foden W., et al., editors. Red List of South African Plants. Vol. 25. Pretoria, South Africa: Strelitzia, South African National Biodiversity Institute; 2009. pp. 6–16. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ndawonde B. G., Zobolo A. M., Dlamini E. T., Siebert S. J. A survey of plants sold by traders at Zululand muthi markets, with a view to selecting popular plant species for propagation in communal gardens. African Journal of Range & Forage Science. 2007;24(2):103–107. doi: 10.2989/AJRFS.2007.24.2.7.161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tshisikhawe M. P. An Ecological Evaluation of the Sustainability of Bark Harvesting of Medicinal Plant Species in the Venda Region, Limpopo Province, South Africa [PhD thesis] Pretoria, South Africa: University of Pretoria; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Monakisi C. M. Knowledge and Use of Traditional Medicinal Plants by the Setswana-speaking Community of Kimberley, Northern Cape of South Africa [M.S. dissertation] Cape Town, South Africa: Stellenbosch University; 2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Macía M. J., Armesilla P. J., Cámara-Leret R., et al. Palm Uses in Northwestern South America: A Quantitative Review. The Botanical Review. 2011;77(4):462–570. doi: 10.1007/s12229-011-9086-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gruca M., Cámara-Leret R., Macía M. J., Balslev H. New categories for traditional medicine in the economic botany data collection standard. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;155(2):1388–1392. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stats SA. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P03093/P030932016.pdf.

- 40.Raimondo D., von Staden L., Foden W., et al. Red List of South African Plants. Pretoria, South Africa: South African National Biodiversity Institute; 2009. (Strelitzia 25). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Victor J. E., Koekemoer M., Fish L., Smithies S. J., Mossmer M. SABONET Report no. 25. Pretoria: South Africa; 2004. Herbarium Essentials: The Southern African Herbarium User Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Retief K., West A., Pfab M. Are you involved in the illegal cycad trade? Public misconceptions which are detrimental to the survival of South Africa’s cycads. Veld and Flora. 2015;101(1):13–15. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article.