Abstract

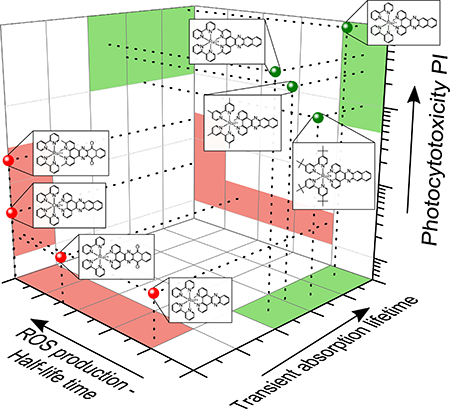

This study investigates the correlation between photocytotoxicity and the prolonged excited state lifetimes exhibited by certain Ru(II) polypyridyl photosensitizers comprised of π-expansive ligands. The eight metal complexes selected for this study differ markedly in their triplet state configurations and lifetimes. Human melanoma SKMEL28 and human leukemia HL60 cells were used as in vitro models to test photocytotoxicity induced by the compounds when activated by either broadband visible or monochromatic red light. The photocytotoxicities of the metal complexes investigated varied over two orders of magnitude and were positively correlated with their excited state lifetimes. The complexes with the longest excited state lifetimes, contributed by low-lying 3IL states, were the most phototoxic toward cancer cells under all conditions.

Keywords: ruthenium, osmium, reactive oxygen species, singlet oxygen, metal-organic dyads, nanosecond time-resolved spectroscopy, transient absorption spectroscopy, photodynamic therapy

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes have been at the forefront of transition metal chemistry for over three decades due to their highly tunable photochemical, photophysical, and electrochemical properties. They continue to be of intense focus in light-based applications such as solar energy conversion,1–6 photocatalysis,7–12 luminescence sensing,13 and more recently photodynamic therapy (PDT)14–18 and photochemotherapy (PCT).19–22 For any of these applications, including PDT, there is the need to identify the most suitable candidates (from virtually unlimited possibilities) using properties that are straightforward to measure. Thus, we became interested in assessing the predictive strength of key fundamental photophysical parameters associated with Ru(II) complexes for in vitro photobiological activity, namely photocytotoxicity as it relates to PDT.

Briefly, PDT is an anticancer modality whereby an otherwise nontoxic photosensitizer (PS), in this case a Ru(II) compound, is activated by light to destroy tumor tissue and vasculature, and to induce an immune response.23–25 The PDT effect is mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS) that include singlet oxygen (1O2), produced via energy exchange between the photoexcited PS and ground-state molecular oxygen (type II). Other ROS, such as those formed in electron transfer reactions (type I), have also been implicated, but 1O2 is considered to be the most important contributor to the PDT effect. Currently, the only FDA-approved PS for cancer therapy is Photofrin, a complex mixture of porphyrin-based oligomers with a number of drawbacks. Transition metal complexes, especially Ru(II) compounds, have emerged as attractive alternatives with the potential to overcome some of the limitations associated with the first-generation PSs such as Photofrin. In fact, one Ru(II) compound, our own TLD1433,26–28 has successfully completed a Phase Ib human clinical trial for treating non-muscle invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) with PDT (ClinicalTrials.gov, identifier NCT03053635) and will now be evaluated in a much larger Phase II study.

A major attraction of Ru(II) compounds as PSs for PDT is that their modular architecture can be changed systematically to create numerous excited state configurations that are accessible using therapeutic wavelengths of light. Examples of such electronic states include: metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT), ligand-to-metal charge transfer (LMCT), metal-centered (MC), intraligand (IL), intraligand charge transfer (ILCT), and metal-to-metal charge transfer (MMCT) (in the case of multimetallic compounds).29 Many of these systems can be prepared in high yield as single compounds, with photophysical properties that depend strongly on the nature of the lowest-lying excited states and their excited state dynamics.30,31 For example, the identities of the ligands and their coordination environments can alter absorption and emission wavelengths, molar extinction coefficients, luminescence quantum yields, 1O2 quantum yields, excited state lifetimes, and photodissociation rates.32–34

Since the generation of ROS (specifically 1O2) is the basis of the PDT mechanism, Ru(II) PSs for PDT should be designed to establish excited state dynamics that maximize 1O2 quantum yields. One strategy involves lengthening intrinsic triplet lifetimes of the PS, which has the desirable effect of improving sensitivity to excited-state quenchers such as oxygen. It has been previously shown that the inclusion of π-expansive ligands (i.e., organic chromophores) into Ru(II) polypyridyl scaffolds26,35–38 can have profound effects on excited state dynamics and lifetimes. Many of the metal-organic dyads that exhibit prolonged triplet state lifetimes do so by lowering the energy of the 3IL excited state with respect to the 3MLCT. This leads to 3MLCT-3IL excited state equilibration (when the two states are in energetic proximity) or to the population of pure 3IL states (when the 3IL state is substantially lower in energy).35,39–47 The 3IL state has significant ππ* character, which is responsible for the reduced rates of intersystem crossing (ISC) and extremely long-lived triplet excited states that are typical for organic chromophores. As PSs, the metal-organic dyads capitalize on the high quantum yields for triplet state formation and visible light absorption afforded by the Ru(II) center, and the extremely long 3IL lifetimes afforded by the organic chromophore, thereby yielding large 1O2 yields with longer wavelengths of light and improved photocytotoxicity.

We have observed that many Ru(II) metal complexes with π-expansive ligands (e.g., TLD1433) exhibit potent in vitro PDT effects.30,31,38,48–50 However, given the sheer number of structural possibilities for Ru(II)-based PSs, being able to reliably predict in vitro PDT effects from structure-activity relationships (SARs) using cell-free methods would accelerate PS discovery. The purpose of the present study was to investigate whether photophysical properties, specifically the excited state lifetime, could be used as a tool for predicting the potential of new Ru(II)-based PSs for photobiological applications such as in vitro PDT. We also wished to examine whether photoactivity, defined here as ROS production, could be correlated to the excited state lifetime and photocytotoxicity and thus predict the magnitude of a PDT effect in vitro.

The establishment of SARs for inorganic compounds lags the field of medicinal chemistry for organic compounds, and the establishment of SARs for inorganic PSs (and their potential as in vitro PDT agents) is even further behind. This study attempts to begin to address this knowledge gap. We systematically evaluated a series of structurally related Ru(II)-based PSs derived from the π-expansive benzo[i]dipyrido[3,2-a:2′,3′-c]phenazine (dppn) ligand (plus one of its Os(II)-based analogs) to develop a predictive approach using cell-free methods to assess the potential of transition metal complexes as in vitro photobiological agents. The robustness of this approach was further challenged by using MeCN as the solvent for spectroscopy measurements to make predictions regarding photobiological activities in aqueous systems. The reason for employing an aprotic organic solvent for the spectroscopy measurements was two-fold: 1O2 emission is quenched by water, and the vast quantity of spectroscopic data collected in MeCN in the literature for Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes.

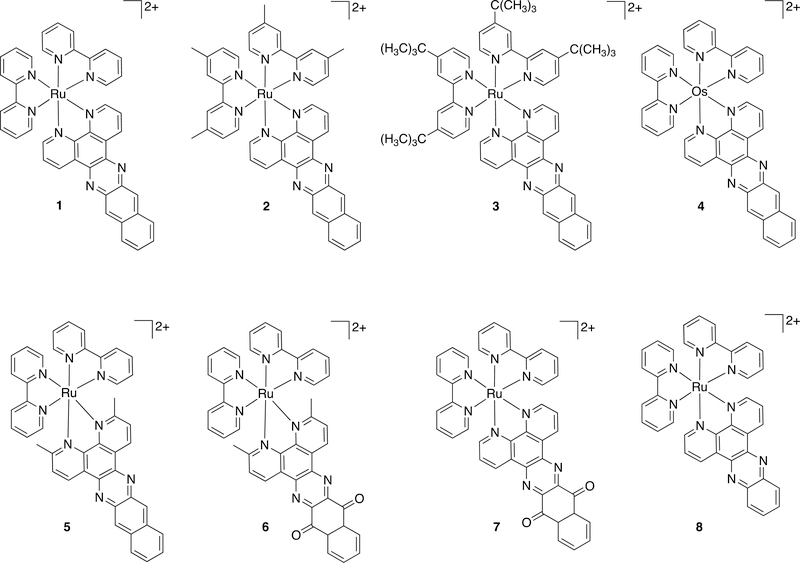

The structures shown in Chart 1 had been previously investigated by us in the HL60 cell line, but the focus of that study was to identify the structural requirements for achieving in vitro PDT effects with red light for compounds with very low molar extinction coefficients in this wavelength range.51 In addition, compound 1 was previously explored for photodynamic inactivation of Escherichia coli by Wang and coworkers.52 In the present study, we investigated (a) cell-free photoactivity (quantified as 1O2 and ROS production) and (b) cell-free excited-state lifetime as primary photophysical parameters, and we correlated these values with photocytotoxicity in two different cell lines (SKMEL28 and HL60 cancer cells). The members of this small library of compounds were strategically chosen: (a) parent 1 for its long 3IL lifetime, (b) 8 for its typical 3MLCT lifetime, (c) 5 for its anticipated extremely short 3MLCT lifetime (due to population of 3MC states) and long 3IL lifetime, (d) 6-7 for their disrupted π-conjugation and anticipated short lifetimes, (e) 4 for its low-energy 3MLCT state and much shorter lifetime (due to its lower 3MLCT energy and increased spin-orbit coupling, SOC) compared to its Ru(II) counterpart 1, and (f) 2-3 for their intact π-conjugation and anticipated long 3IL lifetimes. The rationale was that a range of excited state lifetimes in a set of related compounds would test the predictive strength of this parameter for cell-free photoactivity and ensuing photocytotoxicity (and in vitro PDT effects). In addition, we further assess the predictive strength of cell-free photoactivity for photocytotoxicity (and in vitro PDT effects).

Chart 1.

Molecular Structures of the Compounds Used in this Study.

Experimental Procedures

Synthesis

The synthetic details for 1–8 were described previously.51 The MeCN-soluble (PF6)2 salts of the complexes were used for spectroscopic studies, and the water-soluble Cl2 salts were used for the ROS experiments and in vitro assays.

ROS production

Poly[(N-acryloylmorpholine)50-b-(N-acryloylthio-morpholine)30] micelles were prepared and loaded with Nile red according to an established procedure.53 Aqueous solutions (200 μL) of micelles containing Nile red (0.1 mg mL−1) were treated with 2.8 mL of aqueous metal complex (OD455nm = 0.1) and irradiated with constant stirring using a blue LED (λem = 455 nm) with an irradiance of 510 mW cm−2 at the sample. After each 20-min irradiation period, steady-state emission spectra (λex = 550 nm) were recorded, and the decay of the emission signal from Nile red (λem = 620 nm) was analyzed using a monoexponential fit to obtain a half-life (t½).

Singlet oxygen quantum yields

Singlet oxygen emission (λmax=1268 nm) sensitized by complexes 1–8 (5 μM) was measured in aerated MeCN using a PTI Quantamaster spectrophotometer equipped with a Hamamatsu R5509–42 near-infrared PMT. Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ) were calculated relative to [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2 as the standard (ΦΔs= 0.56 in aerated MeCN)54 according to Eq 1, where I, A, and η are integrated emission intensity, absorbance at the excitation wavelength, and refractive index of the solvent, respectively, and the subscript s denotes the standard. Values for ΦΔ were reproducible to within <5%.

| (1) |

Spectroscopy

Steady-state UV/Vis absorption and emission spectra were recorded in a 1-cm quartz cell on a Jasco V-670 spectrophotometer or a Jasco FP-6200 spectrofluorometer, respectively. The metal complexes were dissolved in MeCN (OD=0.4 at 410 nm), and the freeze-pump-thaw method was used to remove oxygen for nanosecond transient absorption and emission lifetime measurements. Nanosecond transient absorption measurements were performed in a sealed quartz cell with an optical path length of 1 cm. The commercial setup (Pascher Instruments AB) was used as described in literature.49 The solutions were excited with 10-ps pulses centered at 410 nm, while the probe-wavelength was scanned between 500 and 800 nm in steps of 50 nm. Sample integrity was ensured by recording absorption spectra of the samples before and after each spectroscopic experiment. No spectral changes indicative of sample degradation were observed. Quantitative data analysis was based on a global fit of the data.

(Photo)cytotoxicity assays

Stock solutions of the chloride salts of the Ru(II) complexes were prepared at 5 mM in 10% DMSO in water and kept at −20 °C prior to use. Working dilutions were made by diluting the aqueous stock with pH 7.4 Dulbecco’s phosphate buffered saline (DPBS). DPBS is a balanced salt solution of 1.47 mM potassium phosphate monobasic, 8.10 mM sodium phosphate dibasic, 2.68 mM potassium chloride, and 0.137 M sodium chloride (no Ca2+ or Mg2+). DMSO in the assay wells was under 0.1% at the highest complex concentration.

Cell viability experiments were performed in triplicate in 96-well microtiter plates (Corning Costar, Acton, MA), where outer wells along the periphery contained 200 μL pH 7.4 phosphate buffered saline (PBS) with 2.68 mM potassium chloride, 1.47 mM potassium phosphate monobasic, 0.137 M sodium chloride, and 8.10 mM sodium phosphate dibasic to minimize evaporation from sample wells. SKMEL28 and HL60 cells growing in log phase (inoculation density 10,000 and 40,000 cells per well, respectively) were transferred in 50-μL aliquots to inner wells containing warm culture medium (25 μL) and placed in a 37°C, 5% CO2 water-jacketed incubator (Thermo Electron Corp., Forma Series II, model 3110, HEPA class 100) for 1 h to equilibrate. The metal complexes were serially diluted with PBS and pre-warmed before 25 μL aliquots of the appropriate dilutions were added to the cells and incubated at 37 °C under 5% CO2 for a drug-to-light interval of 16 h. Untreated microplates were maintained in a dark incubator while PDT-treated microplates were irradiated in one of the following ways: visible light (400–700 nm, 27.8 mW cm−2) using a 190 W BenQ MS510 overhead projector or red light (625 nm, 28.7 mW cm−2) from a custom-built LED array (PhotoDynamic, Inc.). Irradiation times were approximately 1 h in duration in order to yield light doses of ~100 J cm−2. Both dark and PDT-treated microplates were incubated for another 48 h before adding 10-μL aliquots of Alamar Blue reagent (Life Technologies DAL 1025) to all sample wells and incubating an additional 15–16 h at 37 °C under 5% CO2. Cell viability was assessed based on the ability of the Alamar Blue redox indicator to be metabolically converted to a fluorescent dye by live cells. Fluorescence was quantified with a Cytofluor 4000 fluorescence microplate reader with the excitation filter set at 530 ± 25 nm and emission filter set at 620 ± 40 nm. EC50 values for cytotoxicity and photocytotoxicity were calculated from sigmoidal fits of the dose response curves using Graph Pad Prism 6.0 according to Eq 2. For cells growing in log phase and of the same passage number, EC50 values were reproducible to within ±25% in the submicromolar regime; ± 10% below 10 μM; and ±5% above 10 μM.

| (2) |

Results and Discussion

Steady-state UV-Vis absorption

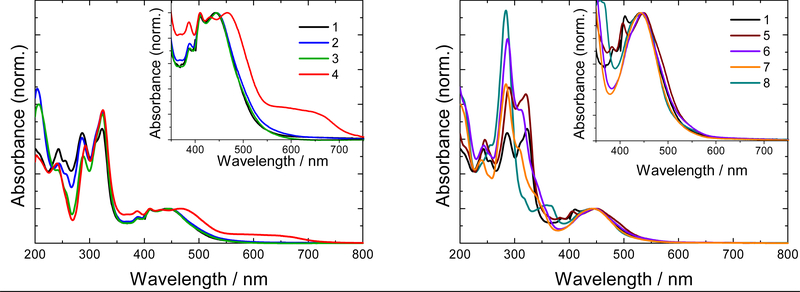

The normalized UV-Vis absorption spectra of the metal complex PSs are shown in Figure 1, and their extinction coefficients at various wavelengths are provided in Table 1. The spectra for the Ru(II) complexes exhibited characteristic ligand-centered 1ππ* transitions involving (a) bpy/phen below 300 nm, (b) intense 1ππ* transitions localized on the phen portion of the more π-expanded ligand near 325 nm, (c) 1ππ* transitions delocalized over the dppn ligand near 390 and 415 nm, and (d) 1MLCT transitions centered around 450 nm. It is the longer-wavelength MLCT transitions in the visible region that are of interest for photobiological applications such as PDT and PCT.55

Figure 1:

UV-Vis absorption spectra of compounds 1–8 with MLCT region highlighted in the inset. Spectra are normalized to OD=0.1 at the MLCT maximum to compare the band shapes.

Table 1:

Electronic Absorption Data for Complexes 1–8.

| cmpd | λmax absorption (log ε), nm |

|---|---|

| 1 | 240 (4.77), 252 (4.71), 284 (4.90), 320 (4.94), 384 (4.18), 406 (4.33), 438 (4.32) |

| 2 | 242 (4.60), 254 (4.59), 282 (4.76), 320 (4.78), 384 (4.07), 406 (4.19), 440 (4.19) |

| 3 | 246 (4.68), 258 (4.69), 286 (4.89), 323 (4.83), 388 (4.14), 411 (4.27), 444 (4.29) |

| 4 | 243 (4.77), 291 (4.95), 324 (4.93), 387 (4.29), 410 (4.32), 430 (4.30), 467 (4.32), 664 (3.57) |

| 5 | 242 (4.79), 286 (4.96), 318 (4.96), 380 (4.17), 402 (4.28), 446 (4.30) |

| 6 | 240 (4.70), 284 (5.02), 308 (4.83), 442 (4.24) |

| 7 | 238 (4.65), 280 (4.97), 302 (4.71), 330 (4.41), 440 (4.24) |

| 8 | 255 (4.59), 284 (4.94), 359 (4.18), 450 (4.14), 462 (4.10) |

There was little effect on this spectral profile with minor changes to the bpy coligand, supported by the observation that spectra for compounds 1–3 and 5 were qualitatively similar. However, changing the metal center or reducing the conjugation on the π-expanded coligand had dramatic effects. For example, compound 4, which is identical to 1 except that Os(II) is the central metal instead of Ru(II), had similar absorption characteristics below 450 nm, but displayed a red-shifted 1MLCT band closer to 500 nm (owing to the higher energy Os(dπ) orbitals) and extended absorption out to 700 nm (due to additional MLCT transitions with triplet character).56–60

Disruption of the π-conjugation of the dppn coligand through oxidation (as in compounds 6 and 7) led to the disappearance of the fine-structure in the 370–430 nm region that was assigned to delocalized 1ππ* transitions characteristic of dppn-containing compounds. Rather, only a single broad 1MLCT band centered at 445 nm was evident for 6 and 7. The absorption spectra of 6 and 7 were remarkably similar to that for 8, which incorporates the less-conjugated dppz ligand. Disruption of π-conjugation through oxidation or a decrease in the number of fused aromatic rings raises the energy of the 1ππ* state, obscuring its identifying signature in the spectra of 6–8. It would be expected that the energy of the 3ππ* state would be similarly affected, making it inaccessible from the 3MLCT state. Such a change has been shown to have profound effects on the excited state dynamics and ensuing photobiological activity (particularly ROS-generating capacity and photocytotoxicity).50 Thus, close scrutiny of the ground-state absorption features of the complexes can reveal important information regarding the expected photophysical and photobiological properties of such systems.

ROS generation

The complexes were assessed for their abilities to photosensitize ROS production using a micelle-based Nile red assay.53 The premise behind the assay is that Nile red is emissive (λex = 550 nm, λem = 620 nm) when it is protected from the polar water exterior (i.e., when the micelles are intact). Oxidative stress (e.g., 1O2 or other ROS), however, leads to degradation of micelle structure, whereby Nile red is exposed to the aqueous surroundings and its emission is quenched. The environmental sensitivity of Nile red emission enables indirect detection of ROS when it is formed by the PSs.

Briefly, the complexes were mixed with polymer micelles containing Nile red53 and irradiated with blue light (455 nm) in 20-minute intervals. After each interval, steady-state emission spectra were collected under conditions where emission from the compounds was negligible. The decrease in Nile red emission with time reflected ROS generation by the compounds when compared to controls: (a) micelles / Nile red without irradiation, (b) micelles / Nile red irradiated without the compound, and (c) micelles / Nile red purged with argon before the irradiation cycles.

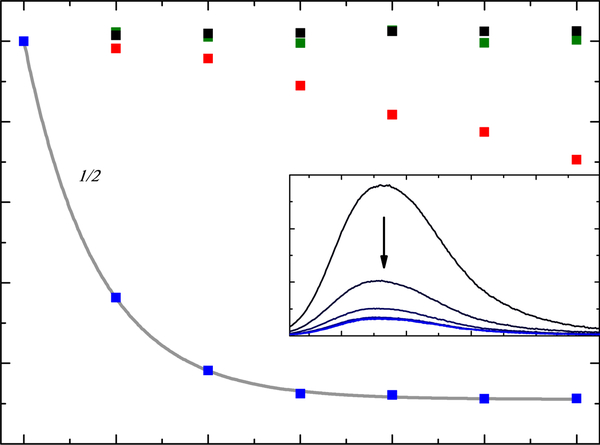

Using compound 8 as a representative example, Figure 2 illustrates the decrease in the steady state emission of Nile red as an indirect probe of ROS production by the compound. Continued irradiation produces additional ROS, which further damage the micelle structure and quench the Nile red fluorescence. Compared to the control experiments, a much more pronounced decay of the emission was observed in the presence of 8. Micelles containing Nile red stored in the dark with no illumination showed no change in emission as expected, whereas only a slight decay was observed for micelles containing Nile red that were irradiated without the compound. This decay was not observed when the solution was purged with argon before irradiation, confirming that the blue light treatment used under these conditions can trigger a low level of micelle degradation in the presence of oxygen. Nevertheless, the emission quenching caused by photosensitizer-mediated ROS production is much larger than the background signal.

Figure 2:

Integrated emission area of micelles / Nile red without PS and stored in the dark (black), without PS and irradiated with LEDs (red), without PS and degassed before irradiated with LEDs (green), and with PS 8 (blue). Inset shows steady state emission spectra (λex = 550 nm) of micelles / Nile red and 8 after each 20 min irradiation with LEDs (λLED = 455 nm, fluence rate = 510 mW cm−2).

The Nile red emission over time for each compound was fit to a monoexponential function to obtain the half-life (t½) of the decay signal, whereby shorter t½ values represent more efficient ROS production. Compound 8, an intermediate ROS producer in the series, gave a t½ value of 11.0 min (Figure 2). Table 2 summarizes t½ values for each compound. ROS generation efficiency (based on the inverse of the t½ values) followed the order: 3, 2, 5, 1 >> 8 >> 7 >> 4, 6. There was very little difference between compounds 1–3 and 5, with t½ values of <10 min. Compounds 4 and 6 caused no substantial decrease in the Nile red emission over the time course of the experiment (120 min), and t½ for 7 was quite long compared to the other compounds.

Table 2.

Photophysical and photobiological data for compounds 1–8. ROS photoactivity (t1/2) quantified by the Nile red assay. Singlet oxygen quantum yields (ΦΔ) measured in MeCN relative to [Ru(bpy)3]2+. Nanosecond emission (τem) and transient absorption (τTA) lifetimes obtained with λex=410 nm. Photocytotoxicity (EC50) determined with broadband visible (400–700 nm) or monochromatic red (625 nm) light treatment. (see SI for PI values).

| Cmpd | t1/2 / min | ΦΔ (λex / nm) | τem / ns a | τTA / μs b | EC50,vis / μM SKMEL28 | EC50,red / μM SKMEL28 | EC50,vis / μM HL60 c | EC50,red / μM HL60 c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | <10 d | 0.75 (438) | 803e | 22.9 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.3 ± 0.02 | 1.25 ± 0.10 |

| 2 | <10 d | 0.78 (440) | 800 | 14.2 | 0.09 ± 0.01 | 0.35 ± 0.01 | 0.4 ± 0.01 | 1.86 ± 0.04 |

| 3 | <10 d | 0.73 (461) | 900 | 17.1 | 0.16 ± 0.01 | 0.27 ± 0.02 | 0.42 ± 0.09 | 1.02 ± 0.01 |

| 4 | n.d.f | 0.01 (470) | 15 | >0.01 | 0.96 ± 0.01 | 92.3 ± 4.5 | 7.4 ± 0.1 | 107 ± 4 |

| 5 | <10 d | 0.95 (446) | 12 | 12.1 | 0.04 ± 0.01 | 0.16 ± 0.03 | 0.21 ± 0.01 | 0.89 ± 0.03 |

| 6 | n.d.f | 0.01 (442) | 25 | 0.1 | 2.26 ± 0.05 | 41.9 ± 0.4 | 1.98 ± 0.10 | 7.1 ± 0.2 |

| 7 | 34 | 0.01 (440) | 15 | 0.1 | 54.2 ± 0.7 | >300 g | 17.6 ± 1.4 | 30.0 ± 2.1 |

| 8 | 11 | 0.53 (462) | 700 | 0.8 | 14.9 ± 0.2 | >300 g | 166 ± 4 | 261 ± 4 |

λobs = 600 nm

analyzed by a global fit routine: λprobe = 500–800 nm

Ref 51

The actual t1/2 values from the fits were 6.2, 4.6, 3.2, and 4.9 min for 1–3 and 5, respectively

Ref 61

τ1/2 was not detectable in the investigated time window

50% cell kill was not obtained over the concentration range tested.

To probe whether singlet oxygen (1O2) was a major contributor to overall ROS production by these compounds, the quantum yields for 1O2 (ΦΔ) were also determined (Table 2) and compared to their ROS-generating abilities. As expected, values for ΦΔ varied dramatically within the series and the general trend positively correlated with ROS production determined by the micelle-based Nile red assay (Figure S1). Yields for 1O2 were largest for 1–3 and 5 (ΦΔ = 73–95%), intermediate for 8 (ΦΔ = 53%), and negligible for 4, 6, and 7 (ΦΔ = 1%). Given the similarities between the trends for ΦΔ and t½ values, 1O2 was inferred to be an important type of ROS for possible photobiological activity.

Large 1O2 quantum yields and efficient ROS production were associated with an intact dppn ligand coordinated to Ru(II) since 1–3 and 5 were superior in comparison to the other compounds. One would expect these photosensitizers to exhibit prolonged triplet lifetimes due to low-energy 3IL states afforded by the π-expansive dppn ligand. Since the trends for ΦΔ and t½ were similar and because it is more general, only the ROS parameter was used for making correlations with excited-state lifetime or photobiological activity.

Alkyl substitution of the bpy coligands of 1 improved ROS generation slightly. 4,4ʹ-substitution of bpy with t-Bu groups (3) was most effective, while 4,4ʹ-substitution of bpy (2) or substitution of dppn with methyl groups (5) was slightly less effective. The Os(II) derivative of 1 and the oxidized dppn cousin of 5 (6) were completely ineffective at ROS generation, and the dppn-oxidized version of 1 (7) was relatively inefficient. Compound 8, based on dppz, yielded more ROS than 4–6 and 7, but much less than the Ru(II) dppn complexes. The major conclusions from these SARs are that (a) disruption of dppn π-conjugation, through oxidation or a reduction in the number of fused aromatic rings, decreases ROS production, (b) oxidation of the dppn ring reduces ROS generation more dramatically than removal of the terminal fused benzene ring, and (c) replacement of Ru(II) with Os(II) quenches ROS production entirely.

Photocytotoxicity

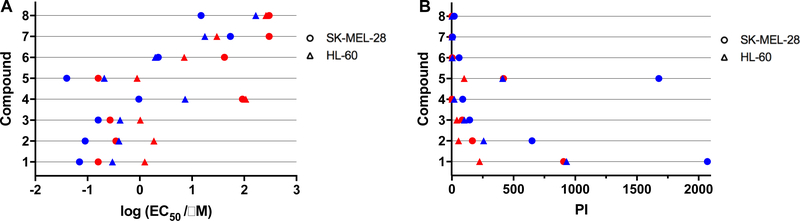

The photocytotoxicities of the compounds toward two different cell lines (SKMEL28 and HL60) cells were quantified as the effective concentration to reduce cell viability to 50% (EC50), where a smaller EC50 value corresponds to a higher photocytotoxicity. These cell lines were chosen to represent two different growth conditions: SKMEL28 melanoma cells form adherent two-dimensional monolayers and HL60 leukemia cells grow in suspension. The EC50 values (Table 2, Figure 3A) were determined for two different light conditions (Figure S2): broadband visible (400–700 nm, 100 J cm−2, 35 mW cm−2) and monochromatic red (625 nm, 100 J cm−2, 28 mW cm−2) light.

Figure 3:

(A) Photocytotoxic activity plot for compounds 1–8 against SKMEL28 melanoma cells (circles) and HL60 cells (triangles) treated with visible (blue symbols) or red light (red symbols). (B) PI activity plot for compounds 1–8 against SKMEL28 melanoma cells (circles) and HL60 cells (triangles) treated with visible (blue symbols) or red light (red symbols).

Photocytotoxicities for the compounds were generally greater toward the adherent SKMEL28 cell line, but trends were qualitatively similar for both cell lines (Figure 3A and Figure S3A). The photocytotoxicies with the visible light treatment for both SKMEL28 and HL60 cells were submicromolar for compounds 1–3 and 5. Under this condition, compounds 7 and 8 were the least potent, and 4 and 6 were intermediate. These EC50 values were larger with red light presumably due to the much lower molar extinction coefficients of the Ru(II) compounds at 625 nm (<100 M−1 cm−1 for 1-3, 5-8), but the potency order for both cell lines was similar between the two light treatments (except for minor differences among the least potent compounds). A two-photon process for in vitro PDT effects with 625-nm light is not likely considering that LEDs emitting with low irradiance were used.

EC50 values for photocytotoxicity may contain some contribution from inherent dark cytotoxicity. Therefore, the dark cytotoxicity of compounds 1–8 toward both cell lines was also quantified as an EC50 value and phototherapeutic indices (PIs) assessed for the two light conditions in each cell line (Tables S1–S2, Figure 3B). The PI is the ratio of the dark to light EC50 values for cytotoxicity. PI values close to 1 indicate that the dark and light EC50 values were similar, and thus there was no amplified effect with light. PIs >> 1, on the other hand, indicate that light enhanced the cytotoxicity of the compound.

For all compounds the visible light treatment gave rise to PI values greater than 1, and these PIs were larger for SKMEL28 cells compared to HL60 cells. The PIs could be divided into two clusters using the arbitrary reference of 100. Half of the compounds gave PIs greater than 100 (1>5>2>3) for both cell lines, and the other half gave PIs below 100 for both cell lines (4>6>8>7). The order of the compound ranking within each cluster was the same for both cell lines. In the cluster where light had a much more pronounced effect, PIs ranged from 144 to 2071 in SKMEL28 cells, and from 101 to 931 in HL60 cells. In the lower PI group, these values ranged from >6 to 89 in SKMEL28 cells and 2–20 in HL60 cells. The PI activity plot in Figure 3B captures these relationships, highlighting that 1, 2, and 5 were the compounds that were best activated by light and that 3, while appearing highly phototoxic, had inherent dark toxicity that contributed to the observed photocytotoxicity. The dark EC50 values for 3 were smaller than those of the rest of the series in both cell lines (i.e., 3 was the most dark cytotoxic).

Only the metal complexes with PIs >100 for visible light (1–3 and 5) gave significant PIs with red light. These PIs ranged from 85 to 906 in SKMEL28 cells and from 41 to 225 in HL60 cells. While attenuated in comparison to visible light (as would be expected with the very low molar extinction coefficients at 625 nm), the values followed the same ranking. Compounds 4 and 6–8 gave PIs near 1 in both cell lines and were therefore considered photobiologically inactive under this condition.

The photocytotoxic EC50 values and the PIs followed the same general trends for photobiological activity (Figure S3B). However, additional factors determine whether the light EC50 or the PI is the better parameter correlate in identifying the best photosensitizer for a photobiological application. For example, photocytotoxicity would be the better parameter for a compound that is highly selectivity for a tumor: both dark and light cytotoxicity could contribute effectively to the antitumor response, and the dark cytotoxicity could contribute in regions where light penetration is suboptimal. On the other hand, a compound with poor tumor selectivity would be better ranked by its PI, since a low dark toxicity would be beneficial to minimize off-site collateral damage to healthy tissue not exposed to light.

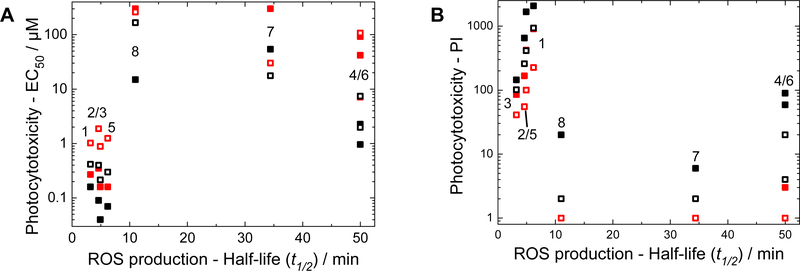

Correlation of cell-free ROS production and photocytotoxicity

The photocytotoxicity trends were highly correlated to ROS production in the cell-free photoactivity experiments; small t½ values determined from the Nile red assays were generally associated with lower EC50 values and larger PIs in the cellular assays (Figure 4). For example, compounds 1–3 and 5 showed the largest ROS production, the most potent photocytotoxicities, and the largest PIs in both cell lines with both light treatments. Compounds 7 and 8, with lower ROS generation, were the least potent in the photocytotoxicity assays, and had the lowest PIs. Compounds 4 and 6, however, were intermediate in potency in the photocytotoxicity assay but were the lowest producers of ROS in the Nile red assay. Therefore, factors other than ROS production may influence photocytotoxicity for some of the compounds. In the case of 4 and 6, the lower PIs indicated that dark cytotoxicity contributed to the apparent photocytotoxicity. In addition, 4 and 6 may exert their photocytotoxicity through ROS-independent mechanisms (or ROS that are not adequately accounted for in the micelle-based Nile red assay). Nevertheless, the correlations between photocytotoxicity (or PI) and ROS production were strong across the family.

Figure 4:

Correlation between the half-life of Nile red fluorescence and EC50 (A) or PI (B) values of the investigated complexes in SKMEL28 (filled) and HL60 cells (open) after irradiation with visible (black) or red (red) light, respectively. No decay was observed for 4 and 6 in the Nile red experiment over this time window, and 1, 2, 3, and 5 gave t½ values <10 min.

Excited state lifetimes

We have previously observed that the intrinsic excited state lifetime appears to be correlated to photobiological activity in a number of metal complex PSs, whereby prolonged triplet state lifetimes (>10 μs) give rise to very potent (i.e., submicromolar) photocytotoxicity.30,31,38,50,62–64 However, the present investigation is our first attempt at quantitatively correlating the excited state lifetimes with photocytotoxicities.

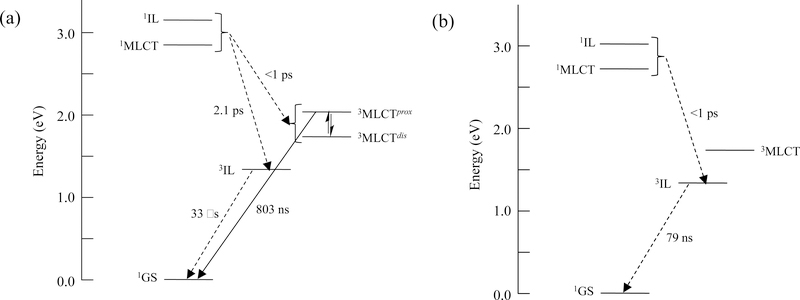

The excited state lifetimes of compounds 1 and 4 have been described elsewhere by Turro and coworkers according to the Jabłonski diagrams shown in Scheme 165 and provide a convenient framework for our photophysical analysis. The excited state dynamics of many Ru(II) polypyridyl complexes related to [Ru(bpy)3]2+ are governed by the triplet MLCT state, with an intrinsic lifetime of ~1 μs, located approximately 2.1 eV above the ground state.66 In cases where one or more ligands are π-extended, the energy of the triplet intraligand (3IL) excited state may drop below that of the 3MLCT, resulting in a situation where the 3IL can be populated, either directly from singlet states or in equilibrium with the 3MLCT state.39 In either case the result is a prolonged intrinsic triplet state lifetime (>>1 μs) that is very sensitive to oxygen and other excited state quenchers (33 μs versus 803 ns in Scheme 1a). The prolonged lifetimes have been attributed to the increased organic character of 3IL states, which reduces SOC and in turn slows ISC. The effect can be reversed when Ru(II) is replaced with Os(II), a heavier atom known to increase SOC and facilitate ISC, whereby the 3IL lifetime is only 79 ns (Scheme 1b).67

Scheme 1:

Jabłonski diagrams of compounds 1 (a) and 4 (b) in MeCN, with lifetimes and energies described by Turro and coworkers.65,67 3MLCTprox and 3MLCTdist in (a) refer to the two low-lying 3MLCT states with electron density proximal and distal to the metal, respectively, that are in equilibrium as shown previously for 8 and related compounds. The equilibrium is also expected for 4 but has not been previously established.

The triplet excited states were probed by nanosecond time-resolved absorption and luminescence spectroscopy, and the transient absorption (τTA) and emission lifetimes (τem) are compiled in Table 2. As expected 2–3 and 8 had emission lifetimes (τem) between 700–900 ns, similar to that reported for 1 (τem=803 ns) and assigned to pure 3MLCT emission.65 Emission lifetimes for compounds 4–7, however, were much shorter. Values for τem were between 12 and 25 ns, which were very close to the instrument response function (10 ns). These shortened emissive lifetimes are related to: (i) the decreased energy of the 3MLCT state and the increased SOC due to the heavier Os(II) atom68 in the case of 4, (ii) steric clash in the Ru(II) coordination sphere, afforded by the methyl groups, providing access to dissociative 3MC excited states for 5 and 6, (iii) and the additional excited state deactivation channels through states of nπ* character for 7 (and possibly for 6 as well).

A long-lived excited state (τTA > 10 μs), that was not apparent from the emission experiments, was observed in the transient absorption signatures of the Ru(II) complexes incorporating the π-extended dppn-based ligands: 1–3 and 5 (Table 2, Figure S4). These compounds also displayed the characteristic TA signature for 3IL states in Ru(II) dppn complexes: a broad and intense excited state absorption (ESA) superimposed on the 3MLCT ground-state bleach.47 Complex 8, derived from the dppz ligand, had a relatively short TA lifetime by comparison and showed the typical negative ΔOD signal associated with strong emission from an 3MLCT state.69 This 820-ns time constant for τTA agreed well with the 700-ns value for τem from the emission measurements. Thus, the state probed by TA experiments for 8 is the luminescent 3MLCT state observed in the emission measurements. However, the TA lifetimes for 1-3 were about twenty times longer than the emission lifetimes, and τTA was >1,000 times longer than τem for 5. Therefore, the 3IL state probed by TA for 1–3 and 5 cannot be the luminescent state observed by emission.65,70

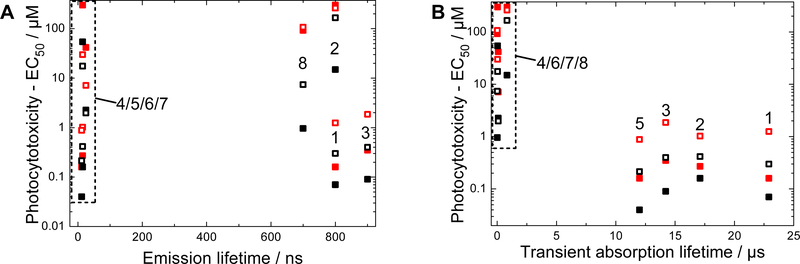

Correlation between excited state lifetimes and photocytotoxicity

Values for τem were compared to the EC50 (Figure 5A) and PI values (Figure S5A) determined from photocytotoxicity experiments across two cell lines (SKMEL28 and HL60) and two different light conditions (broadband visible and monochromatic red), and there were no obvious correlations. The absence of any clear relationship between the 3MLCT emissive lifetime and photocytotoxicity (or PI) suggests that the emitting state does not contribute substantially to the photocytotoxicity of the complexes. Rather, the photocytotoxicity could be controlled by nonradiative state(s) that are silent in the emission experiments.

Figure 5:

(A) Correlation between emission lifetime and the EC50 values of the investigated complexes in SKMEL28 (filled) and HL60 (open) cells after irradiation with visible (black) or red (red) light. Correlation between nanosecond transient absorption lifetime and EC50 values of the investigated complexes in SKMEL28 (filled) and HL60 (open) cells after irradiation visible (black) or red (red) light.

The values for τTA were also compared to EC50 (Figure 5B) and PI (Figure S5B) values determined from photocytotoxicity experiments. In both cell lines and under both irradiation conditions, the long-lived excited states of 3IL configuration corresponded to smaller EC50 values and larger PIs. Two major data clusters appear in Figure 5B: (a) 1–3 and 5 with longer TA lifetimes (>10 μs) and potent photocytotoxicity (submicromolar in many cases), and (b) 4 and 6‒8 with much shorter TA lifetimes (<1 μs) and minimal potency (EC50 > 1 μM). These general trends held across both cell lines despite their different growth properties. Compounds 1–3 and 5 gave relatively small EC50 values and large PIs for both cell lines, while for 4 and 6–8 yielded larger EC50 values and smaller PIs.

Within the clustered areas, there were some deviations in the correlative properties. For example, compound 5 had the shortest TA lifetime of the long-lived cluster, but gave the smallest EC50 values of the potent photocytotoxicity cluster. Close scrutiny also revealed deviations between the two cell lines, with 6 and 7 being more phototoxic toward HL60 cells compared to SKMEL28, and vice versa for 4 and 8. These inconsistencies demonstrate that other factors become important when comparing minor differences in photocytotoxicity and/or triplet state lifetimes. However, the data did unequivocally establish that 3IL states with prolonged lifetimes were much more photocytotoxic than 3MLCT states and that 3IL states were required for photocytotoxicity with the longer-wavelength red light.

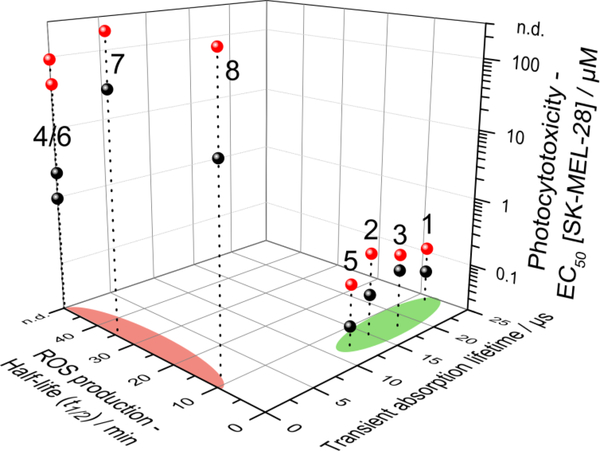

Major determinants of in vitro photobiological activity

Only compounds 1–3 and 5 gave submicromolar (SKMEL28) or low micromolar (HL60) photocytotoxicity with red light (and were more phototoxic with visible light as well), and these were the only compounds that gave TA lifetimes >10 μs with the characteristic transient spectroscopic signature for an 3IL state. These four compounds were also the most potent ROS generators, yielding half-lives <10 min in the Nile red fluorescence quenching experiment. Thus, the Ru(II) complexes with the intact dppn π-expansive ligand were the most photobiologically active compounds of the series.

The predictive strength of the cell-free photoactivity and photophysical measurements for in vitro photobiological activity in this small compound class is shown in Figure 6 for SKMEL28 cells and Figure S6 for HL60 cells. Both the excited state lifetimes and ROS-generating capacities under the cell-free conditions were good predictors of photocytotoxicity and PIs. The results indicate a clear SAR and show that the excited state lifetime, a parameter which is relatively straightforward to assess, presents a suitable metric by which to judge the potential of newly developed Ru(II) PSs for photobiological effects. The photoactivity, another parameter that is easily quantified through the ROS assay or 1O2 quantum yield measurements, suggests that a PDT mechanism may be responsible for the potent phototoxicity in vitro. The photoactivity, another cell-free parameter that is easily quantified through the ROS assay or 1O2 quantum yield measurements, can be used to predict both the likelihood and strength of a PDT mechanism in vitro.

Figure 6:

Correlation between the TA lifetime, half-life from the ROS assay, and in vitro EC50 values for complexes 1–8 in SK-MEL-28 cells after irradiation with or visible (black) or red (red) light. The green and red marked areas show the classification of the compounds as effective or ineffective photobiological agents, respectively. No decay was observed for 4 and 6 in the Nile red experiment over this time window, and 1, 2, 3, and 5 gave t½ values <10 min; for 7 and 8, the red EC50, value was > 300 μM.

Conclusions

In designing next-generation PSs for PDT or PCT, it is important to understand both their photophysical properties and their photobiological effects, and to use this understanding to identify predictive SAR tools that link quantifiable cell-free parameters to in vitro outcomes. For example, compounds that exert their phototoxic effects through ROS generation or through oxygen-independent bimolecular electron- or energy-transfer processes are expected to be particularly potent when their intrinsic excited state lifetimes (i.e., the lifetime in the absence of an excited state quencher) are long. Therefore, the intrinsic lifetime of a photoactive excited state should be a good predictor of in vitro photobiological activity.

This study illustrates this idea with Ru(II) complexes with π-expansive ligands: the long-lived, low-energy 3IL states with increased ππ* character produce excellent in vitro PSs. There was a strong correlation between photobiological activity and ROS production, emphasizing that the excited state lifetime is a reliable predictor of in vitro PDT potency. Indeed, compounds with excited state lifetimes much longer than 1 μs were more efficient ROS producers, had large 1O2 quantum yields, showed potent in vitro photocytotoxicities, and were red-light activated despite small molar extinction coefficients in this wavelength range. In contrast, the compounds with lifetimes around 1 μs or less were considerably less active. Importantly, we found that spectroscopic parameters determined in MeCN were reliable indicators of aqueous photobiological activity, underscoring that it is feasible to use the existing spectroscopic literature (with many lifetimes and 1O2 quantum yields reported in MeCN) to search for promising photobiological agents of this class.

It is worth pointing out that dark toxicity is an important therapeutic variable that is not necessarily connected to the photophysical properties or photoactivity of a compound. Therefore, establishing SARs for photocyctotoxicity and cytotoxicity is key for predicting classes of compounds that should be responsive to light, yet minimally toxic in the dark. Such tools will be powerful predictors in developing new light-responsive inorganic medicinal agents with high PI values. This study demonstrates this as a proof of concept, showing that the excited state lifetime is a suitable correlate to photocytotoxicity in a series of Ru(II) and Os(II) complexes having π-expansive ligands. It also qualitatively substantiates our previous observations that complexes with accessible low-energy 3IL states tend to have long-lived excited states and consequently are among the most potent photosensitizing agents known.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

B.D. and C.R. thank the Deutschen Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, DI1517/18-1, Funktionsbestimmende photoinduzierte Prozesse in Übergangsmetallkomplexen als photoaktivierbare Wirkstoffe in einer zellulären Umgebung) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie (FCI) for support of this work. S.A.M.: Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01CA222227. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. S.A.M. also acknowledges financial support from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Canadian Foundation for Innovation, the Nova Scotia Research and Innovation Trust, and Acadia University. J. B. further thanks the DFG for generous funding in the Emmy-Noether-Program (BR 4905/3-1).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Associated content

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: XXXXX

Correlation plots, spectral profiles of the light devices, kinetic traces for the TA experiments, and tabulated EC50 and PI values

References

- (1).Grätzel M Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Photochem. Photobiol. C 2003, 4, 145–153. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Wang P; Zakeeruddin SM; Moser JE; Nazeeruddin MK; Sekiguchi T; Grätzel M A Stable Quasi-Solid-State Dye-Sensitized Solar Cell with an Amphiphilic Ruthenium Sensitizer and Polymer Gel Electrolyte. Nat. Mater 2003, 2, 402–407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Chen C-Y; Wang M; Li J-Y; Pootrakulchote N; Alibabaei L; Ngoc-le C; Decoppet J-D; Tsai J-H; Grätzel C; Wu C-G; et al. Highly Efficient Light-Harvesting Ruthenium Sensitizer for Thin-Film Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. ACS Nano 2009, 3, 3103–3109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Bräutigam M; Kubel J; Schulz M; Vos JG; Dietzek B Hole Injection Dynamics from Two Structurally Related Ru-Bipyridine Complexes into NiOx Is Determined by the Substitution Pattern of the Ligands. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 2015, 17, 7823–7830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Wahyuono RA; Schulze B; Rusu M; Wächtler M; Dellith J; Seyring M; Rettenmayr M; Plentz J; Ignaszak A; Schubert US; Dietzek B ZnO Nanostructures for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells Using the TEMPO+/TEMPO Redox Mediator and Ruthenium (II). 2016, 3, 1281–1291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Ludin NA; Mahmoud AMA; Bakar A; Amir A; Kadhum H; Sopian K; Shazlinah N; Karim A Review on the Development of Natural Dye Photosensitizer for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev 2014, 31, 386–396. [Google Scholar]

- (7).Welter S; Brunner K; Hofstraat JW; De Cola L Electroluminescent Device with Reversible Switching between Red and Green Emission. Nature 2003, 421, 54–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Mobian P; Kern J-MM; Sauvage J-PP Light-Driven Machine Prototypes Based on Dissociative Excited States: Photoinduced Decoordination and Thermal Recoordination of a Ring in a Ruthenium(II)-Containing [2]Catenane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2004, 43, 2392–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Balzani V; Bergamini G; Marchioni F; Ceroni P Ru(II)-Bipyridine Complexes in Supramolecular Systems, Devices and Machines. Coord. Chem. Rev 2006, 250, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Karnahl M; Kuhnt C; Ma F; Yartsev A; Schmitt M; Dietzek B; Rau S; Popp J Tuning of Photocatalytic Hydrogen Production and Photoinduced Intramolecular Electron Transfer Rates by Regioselective Bridging Ligand Substitution. ChemPhysChem 2011, 12, 2101–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Pfeffer MG; Schäfer B; Smolentsev G; Uhlig J; Nazarenko E; Guthmuller J; Kuhnt C; Wächtler M; Dietzek B; Sundström V; et al. Palladium versus Platinum: The Metal in the Catalytic Center of a Molecular Photocatalyst Determines the Mechanism of the Hydrogen Production with Visible Light. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2015, 54 (17), 5044–5048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Teegardin K; Day JI; Chan J; Weaver J Advances in Photocatalysis: A Microreview of Visible Light Mediated Ruthenium and Iridium Catalyzed Organic Transformations. Org. Process Res. Dev 2016, 20, 1156–1163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Keefe M; Benkstein KD; Hupp JT Luminescent Sensor Molecules Based on Coordinated Metals: A Review of Recent Developments. Coord. Chem. Rev 2000, 205, 201–228. [Google Scholar]

- (14).Velders AH; Kooijman H; Spek AL; Haasnoot JG; de Vos D; Reedijk J Strong Differences in the in Vitro Cytotoxicity of Three Isomeric Dichlorobis(2-Phenylazopyridine)Ruthenium(II) Complexes. Inorg. Chem 2000, 39, 2966–2967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Clarke MJ Ruthenium Metallopharmaceuticals. Coord. Chem. Rev 2003, 236, 209–233. [Google Scholar]

- (16).Szacilowski K; Macyk W; Drzewiecka-Matuszek A; Brindell M; Stochel G Bioinorganic Photochemistry: Frontiers and Mechanisms. Chem. Rev 2005, 105, 2647–2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Crespy D; Landfester K; Schubert US; Schiller A Potential Photoactivated Metallopharmaceuticals: From Active Molecules to Supported Drugs. Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 6651–6662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wachter E; Heidary DK; Howerton BS; Parkin S; Glazer EC Light-Activated Ruthenium Complexes Photobind DNA and Are Cytotoxic in the Photodynamic Therapy Window. Chem. Commun 2012, 48, 9649–9651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Glazer EC Light-Activated Metal Complexes That Covalently Modify DNA. Isr. J. Chem 2013, 53, 391–400. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Knoll JD; Turro C Control and Utilization of Ruthenium and Rhodium Metal Complex Excited States for Photoactivated Cancer Therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev 2015, 282–283, 110–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Poynton FE; Bright SA; Blasco S; Williams DC; Kelly JM; Gunnlaugsson T The Development of Ruthenium(II) Polypyridyl Complexes and Conjugates for in Vitro Cellular and in Vivo Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev 2017, 46, 7706–7756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).White JK; Schmehl RH; Turro C An Overview of Photosubstitution Reactions of Ru(II) Imine Complexes and Their Application in Photobiology and Photodynamic Therapy. Inorg. Chim. Acta 2017, 454, 7–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Dougherty TJ; Gomer CJ; Henderson BW; Jori G; Kessel D; Korbelik M; Moan J; Peng Q Photodynamic Therapy. J. Natl. Cancer Inst 1998, 90, 889–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Macdonald IJ; Dougherty TJ Basic Principles of Photodynamic Therapy. J. Porphyr. Phthalocyanines 2001, 5, 105–129. [Google Scholar]

- (25).Dolmans DEJGJ; Fukumura D; Jain RK Photodynamic Therapy for Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2003, 3, 380–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Shi G; Monro S; Hennigar R; Colpitts J; Fong J; Kasimova K; Yin H; DeCoste R; Spencer C; Chamberlain L; Mandel A; Lilge L; McFarland SA Ru(II) Dyads Derived from α-Oligothiophenes: A New Class of Potent and Versatile Photosensitizers for PDT. Coord. Chem. Rev 2015, 282–283, 127–138. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Fong J; Kasimova K; Arenas Y; Kaspler P; Lazic S; Mandel A; Lilge L A Novel Class of Ruthenium-Based Photosensitizers Effectively Kills in Vitro Cancer Cells and in Vivo Tumors. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci 2015, 14, 2014–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Monro S; Colón KL; Yin H; Roque J; Konda P; Gujar S; Thummel RP; Lilge L; Cameron CG; McFarland SA Transition Metal Complexes and Photodynamic Therapy from a Tumor-Centered Approach: Challenges, Opportunities, and Highlights from the Development of TLD1433. Chem. Rev 2018, DOI: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Farrer NJ; Salassa L; Sadler PJ Photoactivated Chemotherapy (PACT): The Potential of Excited-State d-Block Metals in Medicine. Dalton Trans. 2009, 10660–10701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Reichardt C; Sainuddin T; Wächtler M; Monro S; Kupfer S; Guthmuller J; Gräfe SS; Mcfarland SA; Dietzek B Influence of Protonation State on the Excited State Dynamics of a Photobiologically Active Ru(II) Dyad. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 6379–6388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Reichardt C; Schneider KRA; Sainuddin T; Wächtler M; McFarland SA; Dietzek B Excited State Dynamics of a Photobiologically Active Ru (II) Dyad Are Altered in Biologically Relevant Environments. J. Phys. Chem. A 2017, 121, 5635–5644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Abrahamsson M; Jäger M; Kumar RJ; Tomas Ö; Persson P; Becker H-C; Johansson O; Hammarström L Bistridentate Ruthenium ( II ) Polypyridyl-Type Complexes with Microsecond 3MLCT State Lifetimes: Sensitizers for Rod-Like Molecular Arrays. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2008, 130, 15533–15542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Harriman A; Hissler M; Khatyr A; Ziessel R A Ruthenium(II) Tris (2,2’-Bipyridine) Derivative Possessing a Triplet Lifetime of 42 μs. Chem. Commun 1999, 735–736. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Brown DG; Sanguantrakun N; Schulze B; Schubert US; Berlinguette CP Bis(Tridentate) Ruthenium – Terpyridine Complexes Featuring Microsecond Excited-State Lifetimes. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2012, 134, 12354–12357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Tyson DS; Luman CR; Zhou X; Castellano FN New Ru(II) Chromophores with Extended Excited-State Lifetimes. Inorg. Chem 2001, 40, 4063–4071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).McClenaghan ND; Barigelletti F; Campagna S Towards Ruthenium (II) Polypyridine Complexes with Prolonged and Predetermined Excited State Lifetimes. Chem. Commun 2002, 602–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Ji S; Wu W; Wu W; Guo H; Zhao J Ruthenium(II) Polyimine Complexes with a Long-Lived 3IL Excited State or a 3MLCT/3IL Equilibrium : Efficient Triplet Sensitizers for Low-Power Upconversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 2011, 50, 1626–1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Reichardt C; Pinto M; Wächtler M; Stephenson M; Kupfer S; Sainuddin T; Guthmuller J; McFarland SA; Dietzek B Photophysics of Ru(II) Dyads Derived from Pyrenyl-Substitued Imidazo[4,5-f][1,10]Phenanthroline Ligands. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 3986–3994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Ford WE; Rodgers MAJ Reversible Triplet-Triplet Energy Transfer within a Covalently Linked Bichromophoric Molecule. J. Phys. Chem 1992, 96, 2917–2920. [Google Scholar]

- (40).McClenaghan ND; Leydet Y; Maubert B; Indelli MT; Campagna S Excited-State Equilibration: A Process Leading to Long-Lived Metal-to-Ligand Charge Transfer Luminescence in Supramolecular Systems. Coord. Chem. Rev 2005, 249, 1336–1350. [Google Scholar]

- (41).Goze C; Kozlov DV; Tyson DS; Ziessel R; Castellano FN Synthesis and Photophysics of Ruthenium(II) Complexes with Multiple Pyrenylethynylene Subunits. New J. Chem 2003, 27, 1679–1683. [Google Scholar]

- (42).Simon JA; Curry SL; Schmehl RH; Schatz TR; Piotrowiak P; Jin X; Thummel RP Intramolecular Electronic Energy Transfer in Ruthenium(II) Diimine Donor/Pyrene Acceptor Complexes Linked by a Single C–C Bond. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1997, 119, 11012–11022. [Google Scholar]

- (43).Hissler M; Harriman A; Khatyr A; Ziessel R Intramolecular Triplet Energy Transfer in Pyrene–Metal Polypyridine Dyads: A Strategy for Extending the Triplet Lifetime of the Metal Complex. Chem. Eur. J 1999, 5, 3366–3381. [Google Scholar]

- (44).Tyson DS; Henbest KB; Bialecki J; Castellano FN Excited State Processes in Ruthenium(II)/Pyrenyl Complexes Displaying Extended Lifetimes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2001, 105, 8154–8161. [Google Scholar]

- (45).Tyson DS; Bialecki J; Castellano FN Ruthenium(II) Complex with a Notably Long Excited State Lifetime. Chem. Commun 2000, 2355–2356. [Google Scholar]

- (46).Kozlov DV; Tyson DS; Goze C; Ziessel R; Castellano FN Room Temperature Phosphorescence from Ruthenium(II) Complexes Bearing Conjugated Pyrenylethynylene Subunits. Inorg. Chem 2004, 43, 6083–6092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Harriman A; Hissler M; Ziessel R Photophysical Properties of Pyrene-(2,2′-Bipyridine) Dyads. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys 1999, 1, 4203–4211. [Google Scholar]

- (48).Zhou Q; Lei W; Chen J; Li C; Hou Y; Wang X-S; Zhang B-W A New Heteroleptic Ruthenium (II) Polypyridyl Complex with Long-Wavelength Absorption and High Singlet-Oxygen Quantum Yield. Chem. Eur. J 2010, 16, 3157–3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Pal AK; Hanan GS Design, Synthesis and Excited-State Properties of Mononuclear Ru(II) Complexes of Tridentate Heterocyclic Ligands. Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 6184–6197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Stephenson M; Reichardt C; Pinto M; Wächtler M; Sainuddin T; Shi G; Yin H; Monro S; Sampson E; Dietzek B; McFarland SA Ru (II) Dyads Derived from 2‑(1-Pyrenyl)-1H-Photodynamic Applications. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 10507–10521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Yin H; Stephenson M; Gibson J; Sampson E; Shi G; Sainuddin T; Monro S; McFarland SA In Vitro Multiwavelength PDT with 3IL States: Teaching Old Molecules New Tricks. Inorg. Chem 2014, 53, 4548–4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Lei W; Zhou Q; Jiang G; Zhang B; Wang X Photodynamic Inactivation of Escherichia Coli by Ru(II) Complexes. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci 2011, 10, 887–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Sobotta FH; Hausig F; Harz DO; Hoeppener S; Schubert US; Brendel JC Oxidation-Responsive Micelles by a One-Pot Polymerization-Induced Self-Assembly Approach. Polym. Chem 2018, 9, 1593–1602. [Google Scholar]

- (54).DeRosa MC; Crutchley RJ Photosensitized Singlet Oxygen and Its Applications. Coord. Chem. Rev 2002, 233–234, 351–371. [Google Scholar]

- (55).Durham B; Caspar JV; Nagle JK; Meyer TJ Photochemistry of Ru(bpy)32+. J. Am. Chem. Soc 1982, 104, 4803–4810. [Google Scholar]

- (56).Felix F; Ferguson J; Güdel HU; Ludi A Electronic Spectra of M(bipy)32+ Complexions (M = Fe, Ru and Os). Chem. Phys. Lett 1979, 62, 153–157. [Google Scholar]

- (57).Felix F; Ferguson J; Güdel HU; Ludi A The Electronic Spectrum of Tris(2,2’-Bipyridine)Ruthenium(2+). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 4096–4102. [Google Scholar]

- (58).Decurtins S; Felix F; Ferguson J; Güdel HU; Ludi A The Electronic Spectrum of Tris(2,2’-Bipyridine)Iron(2+) and Tris (2,2’-Bipyridine)Osmium(2+). J. Am. Chem. Soc 1980, 102, 4102–4106. [Google Scholar]

- (59).Imamura Y; Kamiya M; Nakajima T Theoretical Study on Spin-Forbidden Transitions of Osmium Complexes by Two-Component Relativistic Time-Dependent Density Functional Theory. Chem. Phys. Lett 2016, 648, 60–65. [Google Scholar]

- (60).Lazic S; Kaspler P; Shi G; Monro S; Sainuddin T; Forward S; Kasimova K; Hennigar R; Mandel A; McFarland S; Lilge L Novel Osmium-Based Coordination Complexes as Photosensitizers for Panchromatic Photodynamic Therapy. Photochem. Photobiol 2017, 93, 1248–1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Sun Y; Joyce LE; Dickson NM; Turro C Efficient DNA Photocleavage by [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ with Visible Light. Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 2426–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Lincoln R; Kohler L; Monro S; Yin H; Stephenson M; Zong R; Chouai A; Dorsey C; Hennigar R; Thummel RP; McFarland SA Exploitation of Long-Lived 3IL Excited States for Metal–Organic Photodynamic Therapy: Verification in a Metastatic Melanoma Model. J. Am. Chem. Soc 2013, 135, 17161–17175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Ghosh G; Colón KL; Fuller A; Sainuddin T; Bradner E; McCain J; Monro SMA; Yin H; Hetu MW; Cameron CG; McFarland SA Cyclometalated Ruthenium(II) Complexes Derived from α-Oligothiophenes as Highly Selective Cytotoxic or Photocytotoxic Agents. Inorg. Chem 2018, 57, 7694–7712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Wang L; Yin H; Jabed MA; Hetu M; Wang C; Monro S; Zhu X; Kilina S; McFarland SA; Sun W π-Expansive Heteroleptic Ruthenium(II) Complexes as Reverse Saturable Absorbers and Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Inorg. Chem 2017, 56, 3245–3259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Sun Y; Joyce LE; Dickson NM; Turro C Efficient DNA Photocleavage by [Ru(bpy)2(dppn)]2+ with Visible Light. Chem. Commun 2010, 46, 2426–2428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).Juris A; Balzani V; Barigelletti F; Campagna S; Belser P; von Zelewsky A Ru(II) Polypyridine Complexes: Photophysics, Photochemistry, Eletrochemistry, and Chemiluminescence. Coord. Chem. Rev 1988, 84, 85–277. [Google Scholar]

- (67).Sun Y; Joyce LE; Dickson NM; Turro C DNA Photocleavage by an Osmium(II) Complex in the PDT Window. Chem Commun 2010, 46, 6759–6761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Sauvage JP; Collin JP; Chambron JC; Guillerez S; Coudret C; Balzani V; Barigelletti F; De Cola L; Flamigni L Ruthenium(II) and Osmium(II) Bis(Terpyridine) Complexes in Covalently-Linked Multicomponent Systems: Synthesis, Electrochemical Behavior, Absorption Spectra, and Photochemical and Photophysical Properties. Chem. Rev 1994, 94, 993–1019. [Google Scholar]

- (69).Sun Y; Collins SN; Joyce LE; Turro C Unusual Photophysical Properties of a Ruthenium(II) Complex Related to [Ru(bpy)2(dppz)]2+. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 4257–4262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Foxon SP; Alamiry MAH; Walker MG; Meijer AJHM; Sazanovich IV; Weinstein JA; Thomas JA Photophysical Properties and Singlet Oxygen Production by Ruthenium (II) Complexes of Benzo [i] Dipyrido [3,2-a:2′,3′-c] Phenazine : Spectroscopic and TD-DFT Study. 2009, 2, 12754–12762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.