Abstract

Receptor heteromers often display distinct pharmacological and functional properties compared to the individual receptor constituents. In this study, we compared the properties of the DOP-KOP heteromer agonist, 6’-guanidinonaltrindole (6’-GNTI), with agonists for DOP ([D-Pen2,5]-enkephalin [DPDPE]) and KOP (U50488) in peripheral sensory neurons in culture and in vivo. In primary cultures, all three agonists inhibited PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation as well as activated extracellular signal-regulated kinase ½ (ERK) with similar efficacy. ERK activation by U50488 was Gi-protein mediated but that by DPDPE or 6’-GNTI was Gi-protein independent (i.e., pertussis toxin insensitive). Brief pretreatment with DPDPE or U50488 resulted in loss of cAMP signaling, however, no desensitization occurred with 6’-GNTI pretreatment. In vivo, following intraplantar injection, all three agonists reduced thermal nociception. The dose-response curves for DPDPE and 6’-GNTI were monotonic whereas the curve for U50488 was an inverted U-shape. Inhibition of ERK blocked the downward phase and shifted the curve for U50488 to the right. Following intraplantar injection of carrageenan, antinociceptive responses to either DPDPE or U50488 were transient but could be prolonged with inhibitors of 12/15-lipoxgenases (LOX). By contrast, responsiveness to 6’-GNTI remained for a prolonged time in the absence of LOX inhibitors. Further, pretreatment with the 12/15-LOX metabolites, 12- and 15- hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid, abolished responses to U50488 and DPDPE but had no effect on 6’-GNTI-mediated responses either in cultures or in vivo. Overall, these results suggest that DOP-KOP heteromers exhibit unique signaling and functional regulation in peripheral sensory neurons and may be a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of pain.

1. Introduction

It is now generally accepted that G protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) can form and function as homomers or heteromers (oligomers formed between the same or different GPCRs, respectively) (Bouvier, 2001; Milligan and Bouvier, 2005; Pin et al., 2007; Ferre et al., 2014; Gomes et al., 2016). An interesting aspect of receptor heteromers is that they can display pharmacological, functional and regulatory properties that are distinct from those of the individual receptors (Angers et al., 2002; Rozenfeld and Devi, 2011; Ferre et al., 2014; Gomes et al., 2016; Gaitonde and Gonzalez-Maeso, 2017) and therefore can be considered to be unique receptor entities (Pin et al., 2007). For example, agonist occupancy of angiotensin type 1-alpha2C adrenergic receptor heteromers produce receptor conformations that differ from the individual protomers and signal through a unique Gs-cAMP-PKA pathway (Bellot et al., 2015). Similarly, heteromers between mu and delta opioid receptors (MOP and DOP, respectively), constitutively recruit ß-arrestin2, unlike the individual MOP and DOP protomers, resulting in differences in activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase ½ (ERK) in vitro (Rozenfeld and Devi, 2007) and the production of tolerance in vivo (Gomes et al., 2013). As unique pharmacological entities, receptor heteromers could provide for novel targets for pharmacotherapy with the additional benefit of tissue specificity, as heteromers can only form in cells that co-express both receptors.

Although there is abundant evidence for formation of GPCR heteromers in heterologous expression systems, there is comparatively little evidence for a functional role for heteromers in physiologically relevant systems. We recently published compelling evidence for the presence of functional DOP-KOP heteromers in adult rat peripheral sensory neurons in culture and in vivo (Berg et al., 2012; Jacobs et al., 2018). In cultured sensory neurons, DOP and KOP coimmunoprecipitate and a DOP-KOP heteromer-selective antibody augments the antinociceptive efficacy of the DOP agonist [D-Pen2,5]-enkephalin (DPDPE) in vivo (Berg et al., 2012). Further, ligands for DOP allosterically regulate KOP antinociceptive signaling and vice versa. These allosteric effects are abolished by transmembrane peptides or siRNA-induced knockdown or DOP or KOP individually both in cultured neurons as well as in vivo(Jacobs et al., 2018). Interestingly, due to allosteric effects, one ligand, 6’-guanidinonaltrindole (6’- GNTI), is a selective agonist at the DOP-KOP heteromer in adult rat peripheral sensory neurons. 6’-GNTI binds to both DOP and KOP individually without efficacy in rat peripheral sensory neurons, but by binding to DOP in the DOP-KOP heteromer, 6’-GNTI allosterically enhances its own efficacy at KOP, both ex vivo and in vivo (Jacobs et al., 2018).

Opioid receptors expressed by peripheral sensory neurons are regulated differently from their CNS counterparts. Many studies have shown that activation of peripheral opioid receptors does not elicit antinociceptive signaling in the absence of tissue damage or inflammation (Stein and Zollner, 2009; Stein, 2016, 2018). However, under conditions of inflammation or exposure to inflammatory mediators, peripherally-restricted opioid agonists can produce profound antinociceptive responses (Fields et al., 1980; Chen et al., 1997; Obara et al., 2009; Rowan et al., 2009; Berg et al., 2011, 2012; Sullivan et al., 2015a). Similarly, with peripheral sensory neurons in culture, activation of opioid receptors do not activate the Gi-adenylyl cyclase signaling pathway unless cells are first exposed to an inflammatory mediator, such as bradykinin (BK) or arachidonic acid (AA) (Patwardhan et al., 2005; Berg et al., 2007, 2011, 2012; Sullivan et al., 2015a, 2017). Induction of opioid receptor functional competence in peripheral sensory neurons by inflammatory mediators is mediated by cyclooxygenase (COX)-dependent metabolites of AA (Berg et al., 2007, 2011; Sullivan et al., 2015a). In addition, a second AA-mediated signaling pathway regulates the responsiveness of peripheral opioid receptor systems, however in a negative manner (Sullivan et al., 2015a, 2017). Following the initial induction of functional competence via AA signaling, a prolonged period of non-responsiveness ensues during which responsiveness to agonist cannot be re-induced. This non-signaling state is due to production of lipoxygenase (LOX)-dependent AA metabolites, 12-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (HETE) and 15-HETE, and occurs in both cells in culture and in vivo (Sullivan et al., 2015a, 2017). Induction of this LOX-dependent non-responsive state following inflammation limits the utility of peripheral opioid receptors as targets for antinociceptive drug development.

Similar to DOP and KOP individually, DOP-KOP heteromer functional competence also requires an inflammatory condition both ex vivo and in vivo (Berg et al., 2012), however, the sensitivity of the DOP-KOP heteromer to LOX dependent AA metabolites has not yet been determined. In this study we sought to better understand the function and regulation of DOP-KOP heteromers in peripheral pain-sensing neurons under conditions of inflammation in primary cultures of peripheral sensory neurons and in a behavioral model of thermal nociception. We compared responses to the KOP agonist, U50488, the DOP agonist, DPDPE, and the DOP-KOP heteromer agonist, 6’-GNTI, for inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity, stimulation of ERK, and desensitization in cultured sensory neurons and for antinociceptive efficacy in behavioral assays in vivo. Our results indicate that in peripheral pain-sensing neurons, DOP-KOP heteromers display distinct signaling and functional characteristics and are resistant to the long-term inhibitory effects associated with LOX-dependent AA metabolites, suggesting that the DOP-KOP heteromer may be a novel target for development of antinociceptive drugs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

6’-Guanidinonaltrindole (6’-GNTI), U50488, naltrindole, U0126, and λ-Carrageenan were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). [D-Pen2,D-Pen5]Enkephalin (DPDPE), and bradykinin (BK) were purchased from Bachem Americas, Inc. (Torrance, CA). ICI-199441 was purchased from Tocris (Minneapolis, MN). Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2), 12-HETE, 15-HETE, baicalein and luteolin were purchased from Cayman Chemicals (Ann Arbor, MI). SCH772984 was purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX). 125I-cAMP was purchased from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Waltham, MA). Nerve growth factor was from Harlan (Houston, TX). Collagenase was from Worthington (Lakewood, NJ). Hank’s balanced salt solution, feta l bovine serum, Dulbecco’s modified Eagles Medium (DMEM) were purchased from Invitrogen Corp. (Carlsbad, CA). All other drugs and chemical (reagent grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

2.2. Animals

Adult male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington MA) weighing 250–300 g were used in this study. The animal study protocol was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio and conformed to International Association for the Study of Pain and federal guidelines. Animals were housed for 1 week with food and water available ad libitum before behavioral testing or harvesting of sensory neurons.

2.3. Behavioral experiments

Antinociceptive effects of opioid agonists were measured as changes in paw withdrawal latency (PWL) to a thermal stimulus were measured with a plantar test apparatus (Hargreaves et al., 1988) as described previously (Rowan et al., 2009; Berg et al., 2011, 2012; Sullivan et al., 2015a, 2017). The radiant heat stimulus intensity was set to produce baseline PWL of 10 ± 2 s, with a cutoff time of 25 s to prevent tissue damage. Because peripheral opioid receptor-mediated antinociception requires an inflammatory stimulus (Rowan et al., 2009; Berg et al., 2011, 2012; Sullivan et al., 2015a, 2017; Stein, 2018) BK or the polysaccharide carrageenan were used to enhance opioid receptor-mediated antinociception. After baseline PWL was determined, animals were pre-treated (15min) with BK (25 μg) via intraplantar (i.pl.) injection. BK injection produces a transient (< 10min) allodynia such that PWL returns to baseline before opioid administration. Fifteen minutes after the BK injection, rats then received a co-injection (i.pl.) of PGE2 (0.3 μg) with U50488, DPDPE or 6’-GNTI (doses indicated) or vehicle. For experiments using carrageenan to elicit long-lasting thermal allodynia, animals were injected i.pl with 500 μg of carrageenan followed by injection with maximally effective doses of U50488 (0.1 μg), DPDPE (20 μg) or 6’-GNTI (1 μg), 15min, 3h or 24 h later. Measurements of PWL were taken in duplicate at least 30 s apart at 5 min intervals for 20 min after PGE2/opioid (BK pretreatment) or opioid alone (carrageenan pretreatment) injections. Time-course data are expressed as the change (in sec) from individual PWL baseline values and represent mean ± SEM. Drugs were solubilized as follows: BK was solubilized in PBS; U50488 in ddH2O; U0126 and SCH772984, were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (final dilution = 0.1%); PGE2 in ethanol (final dilution = 0.1%). All drugs were administered via i.pl. injection in a volume of 50 μl. None of the drugs at doses tested altered PWL in the contralateral paw, indicating that changes in PWL observed were due to local drug action in the ipsilateral hindpaw. PWL measurements were made by investigators blinded to the treatment allocation.

2.4. Primary cultures of peripheral sensory neurons

Primary cultures derived from rat trigeminal ganglia were prepared as described previously (Berg et al., 2007, 2011, 2012; Jamshidi et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2015a, 2017). Culture media were replaced with fresh DMEM containing 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% GlutaMAX I, 1% mitotic inhibitors (5-fluor-2-deoxyuridine, uridine) and 100 ng nerve growth factor every 48 h and maintained for 5 days. 24 h before experiments, culture media were replaced with DMEM without NGF or serum. All experiments were performed between 5 and 6 days in culture.

2.5. Measurement of cellular cAMP levels

Opioid receptor-mediated inhibition of PGE2-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity was determined by measuring the amount of cellular cAMP accumulated in the presence of the phosphodiesterase inhibitor, rolipram (100 μM), and PGE2 (1 μM) with or without opioid receptor agonists with radioimmunoassay as described previously (Berg et al., 2007, 2011, 2012; Jamshidi et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2015a, 2017). As previously reported, opioid receptors expressed on peripheral sensory neurons require exposure to inflammatory mediators, such as BK or AA, to become functionally competent for inhibition of adenylyl cyclase activity (Patwardhan et al., 2005; Berg et al., 2007, 2011, 2012; Sullivan et al., 2015a, 2015b, 2017). Unless otherwise indicated, cells were pre-treated for 15min with BK (10 μM) before incubation with PGE2 with or without opioid agonist. When tested, ERK inhibitors, and the 12/15-LOX metabolites, 12- and 15-HETE, were administered 15 min before treatment with BK, for a total 30 min incubation before incubation with opioid agonists.

2.6. Measurement of extracellular signal regulated kinase ½ (ERK) activation

Opioid agonist-mediated activation of ERK (15 min, 37 °C) was determined by measuring the levels of phosphorylated ERK (pERK) with the AlphaScreen SureFire Phospho-ERK½ Kit (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences) according to manufacturer’s instructions and a FluoStar microplate reader equipped with AlphaScreen technology (BMG Labtech GMBH, Ortenberg, Germany) (Berg et al., 2011; Jamshidi et al., 2015; Sullivan et al., 2017). For all experiments, cells were pretreated with BK (10 μM) for 15 min before incubation with opioid agonists for the times indicated. We have previously established that phospho-ERK levels return to baseline (vehicle treated) levels within 15 min of incubation with BK (Jamshidi et al., 2015). For experiments assessing Gai-protein mediation, cells were pretreated with pertussis toxin (PTx, 400 ng/ml) for 24 h in serum and growth factor free media.

2.7. Measurement of desensitization of agonist-mediated inhibition of cAMP accumulation

Loss of opioid agonist-mediated inhibition of cAMP accumulation was determined as described previously (Jamshidi et al., 2015). Briefly, cultures were pretreated with BK (10 μM) along with maximal concentrations of U50488, DPDPE, or 6’-GNTI (desensitizing stimulus) or vehicle for 15 min, 37 °C. Cells were washed 3 times with 500 μl of Hank’s balanced salt solution containing 20 mM HEPES and cAMP accumulation in response to PGE2 in the presence of the phosphodiesterase inhibitor, rolipram (100 μM), with maximal concentrations of the opioid receptor agonists (test stimulus) or vehicle was measured as described above. In experiments to block ERK activation, the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase (MEK) inhibitor, U0126 (10 μM), or the ERK½ inhibitor, SCH772984 (1 μM), was applied 15 min before incubation with BK with or without opioid agonist.

2.8. Data analysis

All statistical analysis was done using Prism software (Graphpad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, version 6.0).

For cell culture experiments, concentration-response data were fit to a logistic equation (eq. (1)) using non-linear regression analysis to provide estimates of maximal response (Rmax) and potency (EC50).

| (1) |

where R is the measured response at a given agonist concentration (A), Ro is the response in the absence of agonist, Ri is the response after maximal inhibition by the agonist, and EC50 is the concentration of agonist that produces half-maximal response. Experiments were repeated at least four times, in triplicate, using cells obtained from different groups of rats. Statistical differences in concentration-response curve parameters (EC50 and/or Rmax) between treatment groups with the same agonist were analyzed with a paired t-test. Statistical comparisons of Rmax values between different agonists were done with one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). When only single agonist concentrations were used (e.g., desensitization experiments), statistical significance was assessed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s post test. For ERK experiments, timecourse data were analyzed with two-way ANOVA (time and treatment as factors) followed by Bonferroni’s post test.

For behavior experiments, dose response (dose and treatment as factors) and time course (time and treatment as factors) data were analyzed with two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s post test. In addition, monotonic dose response curves were analyzed with non-linear regression to determine the mean fit ED50 and Rmax parameters. For all behavior experiments, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and data are presented as mean ± SEM of at least 6 animals per group.

3. Results

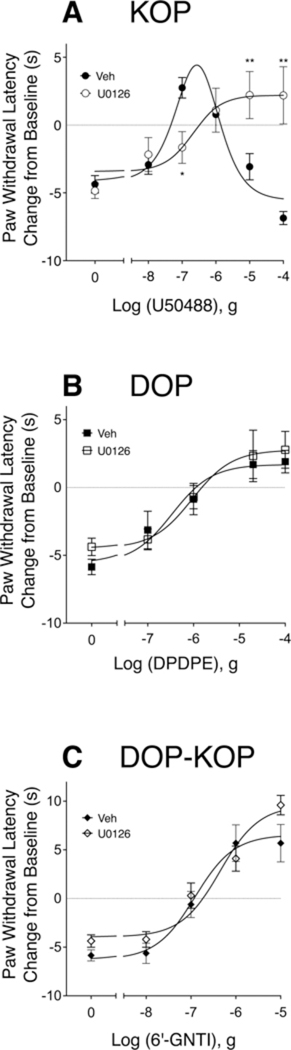

3.1. Dose response curves for U50488, DPDPE, or 6’-GNTI in a behavioral model of thermal nociception

Fig. 1 shows dose-response curves to the KOP agonist, U50488 (Fig. 1A), the DOP agonist, DPDPE (Fig. 1B), and the DOP-KOP heteromer agonist, 6’-GNTI (Fig. 1C) for reduction of PGE2-stimulated thermal allodynia in the adult rat hindpaw following intraplantar injection of BK to induce opioid receptor functional competence (Rowan et al., 2009; Berg et al., 2011, 2012; Sullivan et al., 2015a, 2017). Intraplantar injection of BK produced a transient (10 min) thermal allodynia as evidenced by a reduction in PWL of 6–7 s that returns to baseline before the co-injection of PGE2 and opioid agonist (Suppl. Fig. 1–5). In the absence of an opioid agonist, PGE2 produced a reduction in PWL of 4–5 s (Suppl. Figs. 1–3,5). As we reported previously (Berg et al., 2011; Jamshidi et al., 2015), intraplantar co-injection of U50488 with PGE2 produced a biphasic dose-response curve with a peak dose of 0.1 μg and maximal PWL of +2.75 ± 1 s above pre-injection baseline (Fig. 1A). By contrast, i.pl co-injection of DPDPE or 6’-GNTI produced monotonic dose-response curves (Fig. 1B and C). The maximal PWLs were+2.78 ± 1s and+9.6 ± 1 s above pre-injection baseline PWL, for DPDPE and 6’-GNTI, respectively. We have shown previously that maximal doses of U50488, DPDPE, and 6’-GNTI were peripherally restricted (i.e. effects were local) as they did not produce a change in PWL of the contralateral hindpaw (Rowan et al., 2009; Berg et al., 2011, 2012).

Fig. 1. Dose response curves for the KOP agonist, U50488, the DOP agonist, DPDPE, and the DOP-KOP heteromer agonist, 6’-GNTI, for reduction in PGE2-evoked thermal allodynia in the rat hindpaw.

Animals received intraplantar (i.pl.) injections of BK (25 μg) 15 min before co-injection of PGE2 (0.3 μg) and vehicle or the indicated doses of U50488 (A), DPDPE (B) or 6’-GNTI (C). The MEK inhibitor, U0126 (10 μg) was administered along with BK 15 min prior to co-injection of PGE2 and opioid agonist. PWL was measured in duplicate before injections and at 5 min intervals for 20 min after the last injection. Data shown are expressed as the change (in sec) in PWL from pre-injection baseline at the 10 min timepoint following the last injection. Each data point represents mean ± SEM of 6 animals per group. Baseline PWL averaged 9.66 s ± 0.21. Inhibition of ERK activation with U0126 significantly altered the U50488 dose-response curve (F(1,81) = 6.215, P = 0.0147). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 compared to Vehicle, two-way ANOVA (dose and treatment as factors) with Bonferroni’s post test. Full timecourse data are shown in Supplemental Fig. 1–3.

As shown in Fig. 1A, inhibition of MEK with U0126 (i.pl.), which prevents activation of ERK (English and Cobb, 2002), blocked the descending limb of the dose-response curve for U50488, resulting in a monotonic curve with no change in the maximal antinociceptive effect ( + 2.47 ± 1.7 s). Consistent with the effects of U0126, i.pl. injection of the ERK inhibitor, SCH772984 (1 μg), also blocked the descending limb of the U50488 curve (See Supplemental Fig. 4). In addition to changes in the shape of the dose response curve, inhibition of ERK activation with U0126 reduced the potency of U50488 approximately 10-fold (P < 0.05, see Fig. 1). By contrast, as shown in Fig. 1B and C, the dose-response curves for DPDPE nor for 6’-GNTI were not altered by U0126 (F(1,49) = 0.5039, P = 0.04811 and F(1,40) = 2.692, P = 0.1087, for DPDPE and 6’-GNTI, respectively).

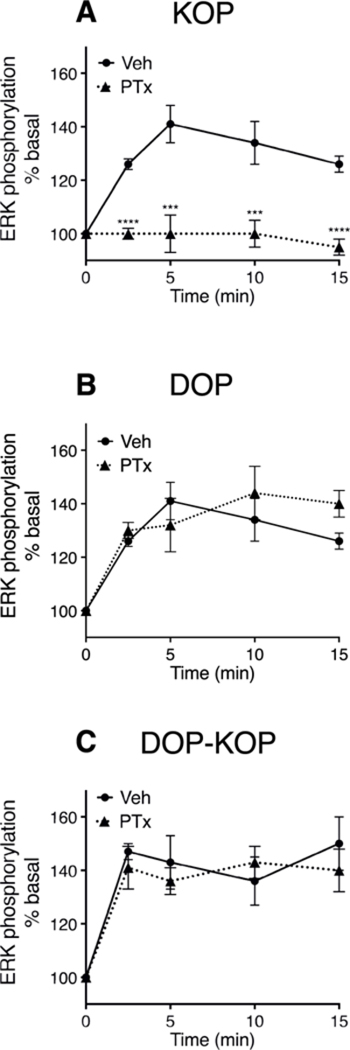

3.2. Agonist-mediated ERK activation

We next compared activation of ERK by U50488, DPDPE, and 6’-GNTI in BK-pretreated primary cultures of peripheral sensory neurons. As shown in Fig. 2 A–C, maximal concentrations of all three agonists increased ERK activation to a similar degree within a similar timeframe (within 2.5 min of administration). There was no difference between the agonists for maximal ERK activation (F (2,12) = 0.519, P = 0.61).

Fig. 2. Timecourse for activation of ERK in response to the KOP agonist, U50488, the DOP agonist, DPDPE, and the DOP-KOP heteromer agonist, 6’-GNTI.

Primary cultures of peripheral sensory were refed with serum free media with or without pertussis toxin (PTx 400 ng/ml) 24 h before experiments. Cells were incubated with BK (10 μM) for 15 min before incubation with either U50488 (100 nM) (A) DPDPE (100 nM) (B) or 6’-GNTI (100 nM) (C) for the times indicated. Phospho-ERK was measured with the AlphaScreen SureFire Phospho-ERK½ kit. Data are expressed as percent of basal (no ligand) activity and represent the mean ± SEM of 4 (DPDPE) or 6 (U50488, 6’-GNTI) experiments. When not visible, error bars are contained within the symbol. Treatment with PTx had no effect on DPDPE- (F(1,30) = 1.003, P = 0.32) or 6’-GNTI- (F(1, 40) = 0.5344, P = 0.47) mediated ERK activation. By contrast, PTx pretreatment completely abolished U50488-mediated ERK activity (F(4,40) = 4.862, P < 0.001). ****P < 0.0001, **P < 0.01, vs Vehicle; two-way ANOVA (time and treatment as factors) with Bonferroni’s post test.

However, the signal transduction mechanism that led to ERK activation differed between the agonists. As shown in Fig. 2A, following treatment of primary cultures with pertussis toxin (PTx) to block receptor activation of Gi/o-proteins, U50488-mediated activation of ERK was abolished. By contrast, neither DPDPE- nor 6’-GNTI-mediated ERK activation was sensitive to PTx treatment, suggesting that these agonists activate ERK by a Gi/o-protein independent transduction mechanism (Fig. 2B and C).

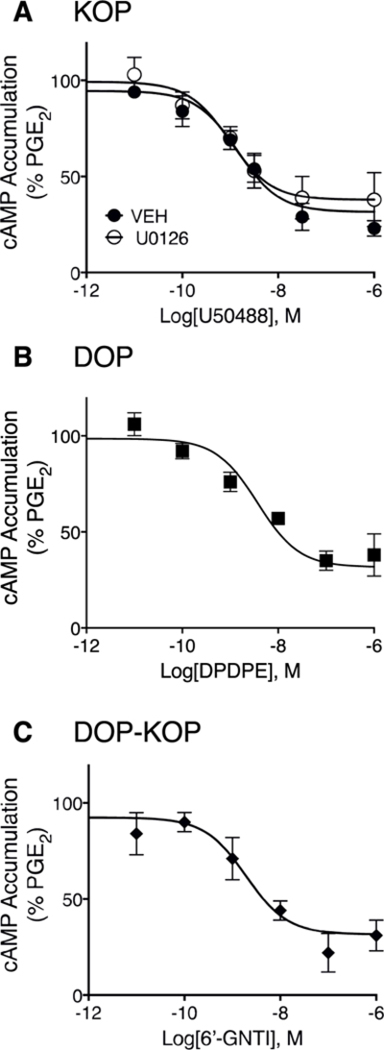

3.3. Agonist-mediated inhibition of cAMP accumulation

Fig. 3 shows concentration-response curves for inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation by U50488, DPDPE, and 6’-GNTI in BK-pre-treated primary cultures of peripheral sensory neurons. Consistent with our previous studies (Patwardhan et al., 2005; Berg et al., 2011, 2012; Jamshidi et al., 2015; Jacobs et al., 2018), all three ligands produced a concentration dependent inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation with similar maximal responses (P = 0.698, one-way ANOVA). Maximal inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP levels were 70% ± 8, 63% ± 6 and 73% ± 2, and the pEC50 values were 8.4 ± 0.41 (4nM), 8.5 ± 0.24 (3nM), and 8.6 ± 0.46 (3nM) for U50488, DPDPE and 6’-GNTI, respectively (mean ± SEM, n = 4). Because the MEK inhibitor, U0126, altered the dose-response curve for U50488-mediated inhibition of PGE2-stimulated thermal allodynia in vivo, we examined the effect of U1026 on the concentration-response curve for U50488-mediated inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation. As shown in Fig. 3A, the curve for U50488 was not altered by U0126. The EC50 and Emax values for U50488-mediated inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation in the presence of U0126 were 2nM (pEC50 = 8.8 ± 0.11) and 63% ±10, mean ± SEM of individual curve fit parameters (n = 4).

Fig. 3. Concentration response curves for U50488-, DPDPE- or 6’-GNTI-mediated inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation in peripheral sensory neuron cultures.

Cells were incubated with BK (10 μM) for 15 min followed by further incubation with the indicated concentrations of either U50488 (A) DPDPE (B), or 6’-GNTI (C) along with PGE2 (1 μM) for 15 min. Cellular cAMP levels were measured with radioimmunoassay. Data are expressed as the percentage of PGE2-stimulated cAMP levels and are the mean ± SEM of 4 separate experiments. When not visible, error bars are contained within the symbol. Concentration-response curves were analyzed with non-linear regression to determine EC50 and Emax values that are provided in the text. As shown in panel A, U50488-mediated inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP levels was not altered in cells pretreated with the MEK inhibitor, U0126 (10 μM); F(1,42) = 1.764, P = 0.19.

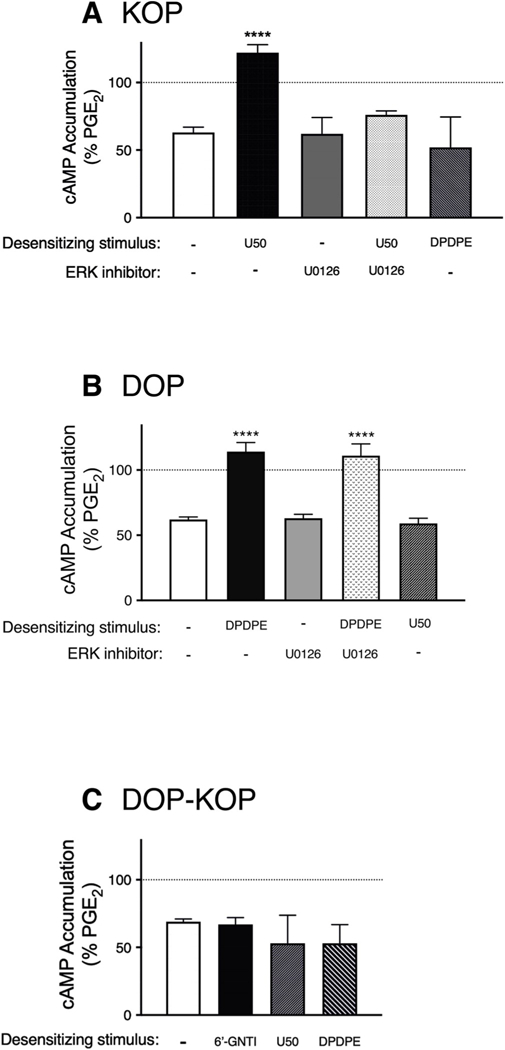

3.4. Homologous desensitization of cAMP signaling

As shown in Fig. 4A, a maximal concentration of U50488 inhibited PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation by approximately 40% in cultures of peripheral sensory neurons. However, when cells were first pretreated with U50488 for 15 min (desensitizing stimulus), the response to the test application of U50488, but not that of DPDPE, was abolished. The desensitizing effect of U50488 pretreatment was blocked by the inhibitor of ERK activation, U0126. Similarly, pretreatment (15 min) with a maximal concentration of the DOP agonist, DPDPE, abolished the test response to DPDPE, but not that of U50488 (Fig. 4B), in a manner that was insensitive to U0126. In contrast to both U50488 and DPDPE, pretreatment with 6’-GNTI did not produce a loss of response to a subsequent test 6’-GNTI application and did not alter test responses to U50488 or DPDPE (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4. Loss of responsiveness for cAMP signaling following acute treatment with U50488 and DPDPE, but not to 6’-GNTI, in primary cultures of peripheral sensory neurons.

Cells were treated with vehicle or the ERK activation inhibitors, U0126 (10 μM) or SCH772984 (10 nM), for 15min before incubation with BK (10 μM) and the indicated opioid (each at 1 μM, i.e. desensitizing stimulus) for 15min. Cells were washed and PGE2-stimulated cAMP levels in the absence or presence of the test opioid (either U50488 (100nM) (A), DPDPE (100nM) (B) or 6’-GNTI (100nM) (C)) were then measured. Data shown represent cAMP levels as a percent of PGE2 and are the mean ± SEM of 3–12 experiments. ****P < 0.0001 vs. Veh as desensitizing stimulus, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post test. As shown in panel C, none of the agonist pretreatments altered responsiveness to a subsequent test challenge to 6’-GNTI (F (3,22) = 2.506, P = 0.09). Neither agonist pretreatment nor ERK inhibitors altered basal (unstimulated) cAMP levels or PGE2-stimulated cAMP levels which were 0.38 pmol/well ± 0.54 and 404% ± 60 above basal, respectively, mean ± SEM, n = 18.

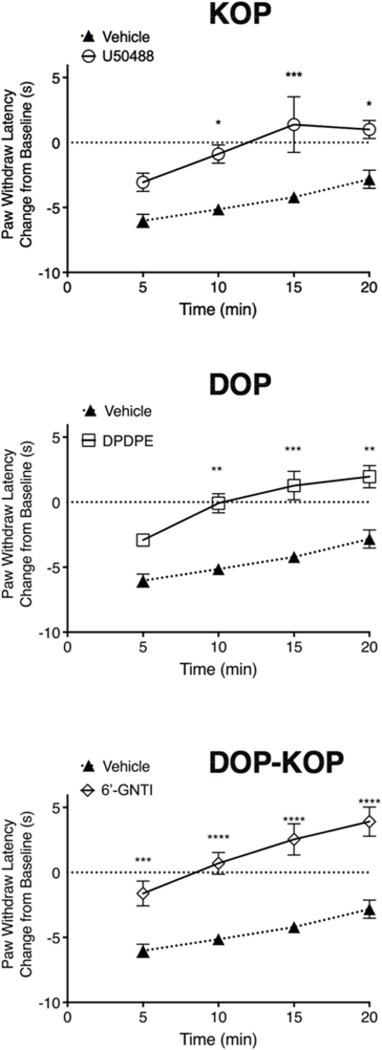

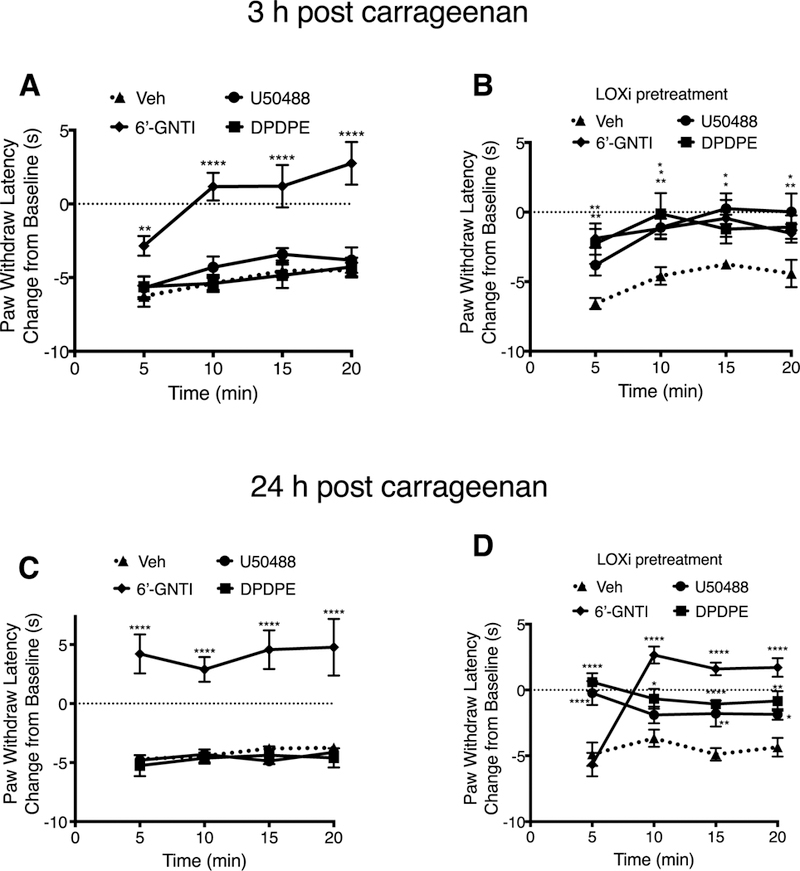

3.5. Agonist-mediated antinociception in a rat model of carrageenan- induced inflammatory pain

Intraplantar injection of carrageenan (500 μg) produced a long-lasting reduction in PWL (Figs. 5–7). Injection (i.pl.) of maximal doses of U50488, DPDPE, or 6’-GNTI, 15 min after carrageenan, each abolished the carrageenan-induced thermal allodynia (Fig. 5). However, when tested 3 and 24 h after carrageenan, both U50488 and DPDPE were ineffective at reducing carrageenan-induced allodynia (Fig. 6A and C). We have previously shown that carrageenan-induced DOP functional competence is transient and that following an initial induction of functional competence, the DOP system subsequently undergoes conversion to a refractory, non-responsive state to agonist due to production of LOX-dependent AA metabolites, 12- and 15-HETE (Sullivan et al., 2015a, 2017). To determine if inhibition of 12/15-LOX could restore KOP, as well as DOP, responsiveness, we injected (i.pl.) a combination of 12- and 15-LOX inhibitors, baicalein and luteolin, 30 min before injection of DPDPE or U50488. As shown in Fig. 6 (B and D), administration of the LOX inhibitors, restored responsiveness to the DOP and KOP agonists at both 3 h (Figs. 6B) and 24 h (Fig. 6D) after injection of carrageenan.

Fig. 5. Inhibition of carrageenan-induced thermal allodynia in the rat hindpaw by the KOP agonist, U50488, the DOP agonist, DPDPE and DOP-KOP agonist, 6’-GNTI, measured 15min after intraplantar injection with carrageenan.

Animals received an injection of 500 μg carrageenan (i.pl.) 15 min before injection (i.pl.) of vehicle or U50488 (0.1 μg), DPDPE (20 μg), or 6’-GNTI (1 μg). PWL was measured in duplicate before and every 5 min for 20 min after injection with agonist. Data are expressed as change (in sec) from individual PWL baselines at each timepoint and represent mean ± SEM of 20 (Veh), 18 (6’-GNTI), or 6 (DPDPE, U50488) animals per group; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001 vs. vehicle, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post test.

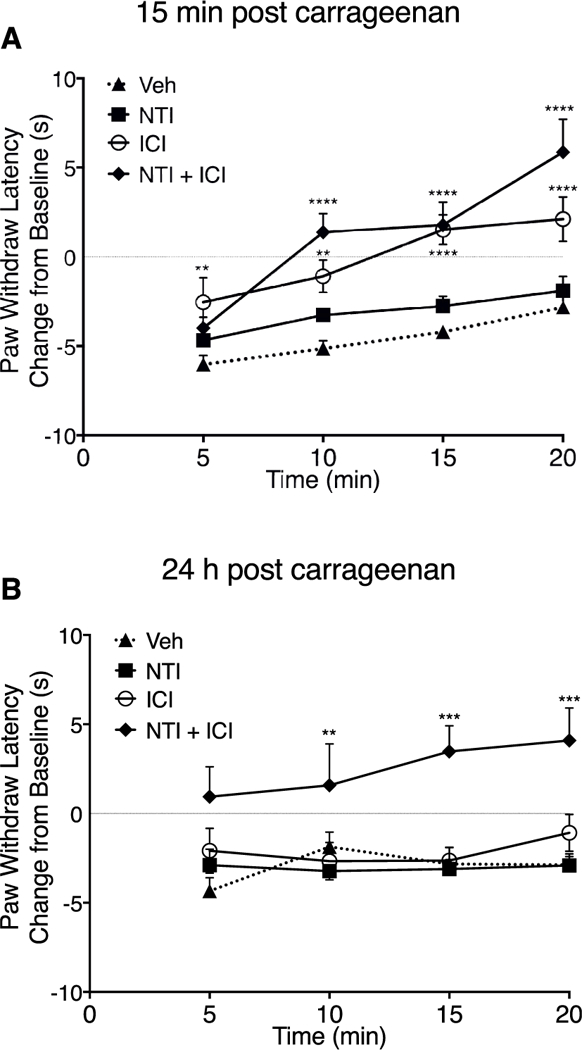

Fig. 7. Inhibition of carrageenan-induced thermal allodynia in the rat hindpaw by the DOP antagonist-KOP agonist allosteric ligand pair, ICI-199441 (ICI) and naltrindole (NTI) measured 15 min (A) and 24 hB) after carrageenan administration.

Rats received injections (i.pl.) of vehicle (Veh), NTI (40 μg), ICI-199441 (0.3 μg) or NTI and ICI-199441 in combination 15 min (A) or 24 h (B) after injection with carrageenan (500 μg, i.pl.). PWL in response to radiant heat applied to the ventral surface of the hindpaw was measured in duplicate before and at 5 min intervals for 20 min after the last injection. Data are expressed as change (in sec) from individual PWL baselines at each timepoint and represent mean ± SEM of 6–12 animals per group. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. vehicle, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post test.

Fig. 6. Inhibition of carrageenan-induced thermal allodynia in the rat hindpaw by the KOP agonist, U50488, the DOP agonist, DPDPE and DOP-KOP agonist, 6’-GNTI, measured 3 and 24 h after intraplantar injection with carrageenan.

PWL was measured after injection (i.pl.) of vehicle or U50488 (0.1 μg), DPDPE (20 μg), 6’-GNTI (1 μg) 3 h (A) or 24 h (C) after injection with carrageenan (500 μg, i.pl.). (B, and D) Opioid agonist antinociceptive responses in the presence of the 12/15-LOX inhibitors, baicalein (3 μg) and luteolin (3 μg), injected (i.pl.) 30 min before injection of opioid agonists. PWL in response to radiant heat applied to the ventral surface of the hindpaw were measured in duplicate before and at 5 min intervals for 20 min after the last injection. Data are expressed as change (in sec) from individual PWL baselines at each timepoint and represent mean ± SEM. In data shown in A, there were 16 (veh), 6 (DPDPE, U50488) or 10 (6’-GNTI) animals per group. For B there were 6 animals per group. For C there were 12 (Veh) or 6 (DPDPE, U50488, 6’-GNTI) animals per group. For D there were 6 (Veh, 6’-GNTI) or 5 (DPDPE, U50488) per group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. vehicle, two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni’s post test.

In contrast to either DPDPE or U50488, responsiveness to the DOP-KOP heteromer agonist, 6’-GNTI, remained for at least 24 h following carrageenan injection (Fig. 6A and B) and was unaffected by inhibition of 12/15-LOX (Fig. 6B and D).

Previously we reported that occupancy of the DOP protomer within the DOP-KOP heteromer with the selective antagonist, naltrindole (NTI), allosterically enhanced the potency of the KOP agonist, ICI-199441, to reduce PGE2-evoked thermal allodynia under BK inflammatory conditions (Jacobs et al., 2018). We next tested this ligand pair for reduction of thermal allodynia 15 min and 24 h after i.pl administration of carrageenan. As shown in Fig. 7A, activation of KOP with ICI-199441 alone completely reduced thermal allodynia when tested 15 min after carrageenan injection, however, as with responsiveness to U50488, ICI-199441 was without effect when tested 24 h after carrageenan. When administered with NTI, which had no effect on its own, antinociceptive responsiveness to ICI-199441 mediated by DOP-KOP heteromer activation remained when tested 24 h after carrageenan (Fig. 7B).

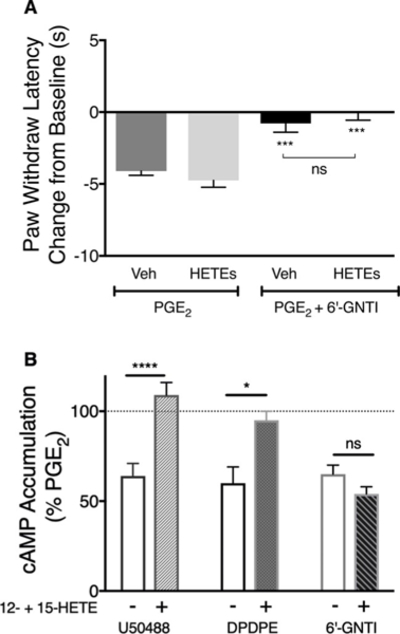

3.6. The effect of 12/15-LOX arachidonic acid metabolites, 12- and 15-HETE, on DOP-KOP heteromer-mediated response

Previously we have shown that exogenous administration of 12- and 15-HETE prevents DOP and KOP agonist-mediated inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation in cultures of sensory neurons and prevents DOP agonist-mediated inhibition of PGE2-stimulated thermal allodynia in vivo (Sullivan et al., 2017). Fig. 8A shows that intraplantar injection of 12-and 15-HETE had no effect on 6’-GNTI-mediated reduction in thermal allodynia. Similarly, in primary cultures, pretreatment with 12- and 15-HETE had no effect on the ability of 6’-GNTI to inhibit PGE2-stimulated cAMP levels but, consistent with our previous results (Sullivan et al., 2017), prevented inhibition of cAMP signaling by U50488 and DPDPE (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8. Effect of 12- and 15-HETE on 6’-GNTI-mediated inhibition of PGE2-evoked thermal allodynia (A) or opioid agonist mediated inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation (B).

A) Rats received injections (i.pl.) of vehicle (Veh), or 12-HETE (0.1 μg) and 15-HETE (0.1 μg) in combination 45 min before injection (i.pl.) with BK (25 μg) to induce functional competence. PGE2 (0.3 μg) was co-injected (i.pl.) with vehicle or 6’-GNTI (1 μg) 15 min later. PWL in response to radiant heat applied to the ventral surface of the hindpaw was measured in duplicate before and at 5 min intervals for 20 min after the last injection. Data are shown as the change from baseline (in sec), measured 10 min following injection of PGE2 with vehicle or 6’-GNTI and represent mean ± SEM of 6 animals per group. ***P < 0.001 vs PGE2 (Veh), one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post test. ns, not significant (B) Primary cultures of peripheral sensory neurons were pretreated with 12-HETE (100 nM) and 15-HETE (100 nM) in combination 30 min before treatment with BK (10 μM) for 15 min. Cells were then incubated with PGE2 (1 μM) with vehicle or maximal concentrations (100nM) of DPDPE, U50488 or 6’-GNTI for 15min, followed by measurement of cAMP accumulation. Pretreatment with the HETEs had no effect on basal or PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation levels which were 0.17 pmol/well ± 0.01 and 561% ± 52% above basal, respectively, n = 8. Data shown represent mean ± SEM of 3 (DPDPE) or 5 (U50488, 6’-GNTI) experiments. Data were evaluated for statistical differences with one-way ANOVA and Bonferroni’s post test. *P < 0.05, ****P < 0.0001 versus control condition (no HETEs). ns, not significant.

4. Discussion

Receptor heteromers have been shown to display novel pharmacological and functional characteristics that are distinct from the individual receptor protomers (Angers et al., 2002; Pin et al., 2007; Rozenfeld and Devi, 2011; Ferre et al., 2014; Gomes et al., 2016; Gaitonde and Gonzalez-Maeso, 2017). In this study, we sought to determine if DOP-KOP heteromers, expressed in peripheral sensory neurons, exhibit distinct signaling and functional properties in comparison with either DOP or KOP individually. In primary cultures of peripheral sensory neurons, we found that mechanisms for desensitization of cAMP signaling differed between the DOP and KOP receptor agonists and importantly, desensitization in response to the DOP-KOP heteromer agonist, 6’-GNTI, did not occur. However, perhaps the most striking result is that, unlike the individual DOP and KOP receptors, DOP-KOP heteromers maintain responsiveness for antinociception under prolonged inflammatory conditions. These results provide the first evidence for distinct signaling and functional properties of DOP-KOP heteromers in peripheral pain-sensing neurons (nociceptors).

In adult rat peripheral sensory neurons in culture and in vivo, 6’-GNTI behaves as a DOP-KOP heteromer-selective agonist (Jacobs et al., 2018). Although 6’-GNTI was originally characterized as a weak agonist for KOP (Sharma et al., 2001) and has been shown to have KOP agonist activity in HEK cells that overexpress KOP (Rives et al., 2012) and in striatal neurons (Schmid et al., 2013), it has no agonist activity in rat peripheral sensory neurons in the absence of DOP (Jacobs et al., 2018). When DOP expression is reduced by siRNA in vivo or in cultured sensory neurons, 6’-GNTI acts as an antagonist at KOP (Jacobs et al., 2018). 6’-GNTI also binds to DOP, but without efficacy, in HEK cells (Waldhoer et al., 2005) or in rat peripheral sensory neurons (Jacobs et al., 2018). Although the KOP agonists, U50488 (Fig. 1A) and Salvinorin-A (Berg et al., 2011;Jamshidi et al., 2015) have inverted U-shaped dose-response curves for antinociception, the curve for 6’-GNTI is monotonic (Fig. 1C). The downward phase of the antinociception dose-response curve for U50488 is mediated by activation of ERK as the downward phase is blocked by inhibition of ERK activation with U0126 or SCH772984 (Fig. 1A, Supplemental Fig. 4 and (Jamshidi et al., 2015)). Inhibition of ERK activation also reduced the antinociceptive potency of U50488 (Fig. 1A). By contrast, U0126 did not alter the antinociception dose-response curve for 6’-GNTI (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that the DOP protomer of the DOP-KOP heteromer may modify the agonist effect at KOP resulting in an ERK-insensitive antinociceptive response.

Similarly, although all three agonists activated ERK (Fig. 2), the mechanisms by which ERK was activated differed. U50488-mediated activation of ERK was blocked by pertussis toxin (Fig. 2A) indicating a KOP-Gi-dependent pathway. By contrast, ERK activation by DPDPE and 6’-GNTI occurred by a pertussis toxin-insensitive pathway (Fig. 2B and C, respectively). It is notable that for both DPDPE and 6’-GNTI the dose-response curves for antinociception were monotonic, suggesting that the mechanism (i.e., G-protein dependence vs G protein independence) by which ERK is activated may play a role in its subsequent effects in peripheral sensory neurons (e.g. the downward phase of the U50488 antinociceptive dose-response curve). Differential effects of ERK that are dependent upon the mechanism of activation have been reported by others (Azzi et al., 2003; Tohgo et al., 2003; Ahn et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2008a, 2010a, 2010b). For example, when ERK is activated by a non-G protein, ß-arrestin-dependent mechanism, activated ERK translocates to the nucleus to regulate gene transcription (Zheng et al., 2008a, 2010a, 2010b), however, when activated by a G protein-dependent pathway, activated ERK remains in the cytoplasm and phosphorylates various cytosolic targets (Yoon and Seger, 2006; Zheng et al., 2008b).

In addition to regulation of various signal transduction mechanisms, some of which lead to antinociceptive effects and therapeutic benefit, opioid receptor systems undergo loss of responsiveness (desensitization) that can limit therapeutic efficacy of analgesic drugs. There are a variety of mechanisms for desensitization that can be effector pathway/response-dependent (i.e. different cellular responses coupled to a receptor can desensitize differentially) (Stout et al., 2002; Gainetdinov et al., 2004; Kelly et al., 2008; Raehal et al., 2011). Although activation of all three receptors (DOP, KOP and DOP-KOP heteromers) produced equivalent levels of inhibition of PGE2-stimulated cAMP accumulation in peripheral sensory neurons in culture (Fig. 3), the receptor systems differed with respect to their ability to undergo desensitization of this signaling pathway. Prior activation of DOP or KOP with U50488 or DPDPE, respectively, abolished inhibition of cAMP accumulation in response to a second test application of the respective agonist (Fig. 4A and B). Consistent with our previous findings (Jamshidi et al., 2015), desensitization of KOP was blocked by inhibition of ERK activation with U0126. In contrast, desensitization of DOP was not altered by ERK inhibition, even though both the DOP agonist and KOP agonist activated ERK similarly in peripheral sensory neurons albeit by different mechanisms. As discussed above, the signal transduction mechanism that leads to ERK activation may dictate the cellular consequences of ERK (Azzi et al., 2003; Tohgo et al., 2003; Ahn et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2008b, 2010a, 2010b). To best of our knowledge, the cytosolic targets for ERK that regulate KOP function are not known, however, our data are consistent with the idea that Gi-protein mediated activation of ERK retains its activity in the cytosol (Zheng et al., 2008b) leading to desensitization of peripheral KOP receptor-mediated antinociceptive signaling in response to U50488.

In contrast to DOP and KOP receptor systems, pretreatment with the DOP-KOP heteromer agonist, 6-GNTI, had no effect on a second test application of 6’-GNTI for inhibition of cAMP signaling, suggesting that the DOP-KOP heteromer system may not undergo desensitization for Gi-protein mediated signaling. Furthermore, there was no cross desensitization produced by either U50488 or DPDPE pretreatment on the response to a subsequent test application of 6’-GNTI. It has been suggested that agonist bias toward Gi-protein signaling over beta-arrestin recruitment may lead to improved antinociceptive efficacy without tolerance and other adverse effects associated with ß-arrestin activation (Bohn et al., 1999; Raehal et al., 2005; Bruchas et al., 2007; White et al., 2014). For MOP-DOP heteromers that form in the CNS, allosteric modulation of the MOP protomer by DOP leads to a reduction in beta arrestin recruitment to the complex that correlates with a reduction in tolerance (Gomes et al., 2013). 6’-GNTI has been shown to have bias for Gi-protein activation over beta-arrestin recruitment for KOP receptors expressed in HEK cells (Rives et al., 2012). Although we have not yet determined the signaling bias of 6’-GNTI in peripheral sensory neurons, its intriguing to speculate that 6’-GNTI-mediated activation of DOP-KOP heteromers may also preferentially activate Gi-protein signaling such that beta-arrestin-mediated desensitization may not readily occur. Importantly, since cellular desensitization may underlie, at least in part, tolerance to analgesics, the apparent lack of 6’-GNTI mediated desensitization of DOP-KOP heteromer Gi signaling suggests that this heteromer may serve as a novel therapeutic target to treat pain that is responsive to inhibition of nociceptor activity.

Carrageenans are polysaccharides isolated from seaweed that produce a prolonged inflammatory response that involves release of a wide variety of inflammatory mediators, including BK and AA (Winter et al., 1962; Lo et al., 1987). When injected intraplantarly into the rat hindpaw, carrageenan sensitizes the paw to a thermal heat stimulus (thermal allodynia) that can persist for a prolonged period of time (days) (Joris et al., 1990). We have used this inflammatory model previously to study regulation of DOP in peripheral sensory neurons (Sullivan et al., 2015b, 2017) and found that, as with BK pretreatment, DOP initially becomes functionally competent to reduce thermal nociception after a brief (15 min) exposure to carrageenan. We have previously shown that functional competence of opioid receptors in peripheral sensory neurons is mediated by a cyclooxygenase (COX)-dependent metabolite of AA (Berg et al., 2007, 2011; Sullivan et al., 2015a). However, following an initial induction of functional competence, DOP systems subsequently become unresponsive to agonist after prolonged (3 h) exposure to carrageenan as a result of AA metabolism by 12/15-LOX (Sullivan et al., 2017). Similar to DOP, the functional competence for KOP was transient under carrageenan-induced inflammatory conditions but restored by 12/15-LOX inhibition (Figs. 5 and 6). Surprisingly, the antinociceptive responsiveness of the DOP-KOP heteromer was not transient, but was maintained for up to 24 h (longest time tested) after carrageenan administration. This long-term functional competence was also observed upon activation of the DOP-KOP heteromer with the KOP agonist/DOP antagonist allosteric ligand pair, ICI-199441 and naltrindole (Fig. 7 and (Jacobs et al., 2018)). Consistent with these results, exogenous administration of 12- and 15-HETEs, which block DOP (Sullivan et al., 2017) and KOP (Fig. 8) function, did not alter the function of the DOP-KOP heteromer in vivo nor in cultured sensory neurons (Fig. 8). These results are exciting as they suggest that, unlike peripheral DOP and KOP, the DOP-KOP heteromer may remain responsive to agonist for antinociceptive signaling under prolonged inflammatory conditions. These findings provide the first foundational support for development of novel, peripherally-restricted analgesics that target DOP-KOP heteromers on peripheral sensory neurons for treatment of inflammatory pain.

Functional selectivity, also known as “biased agonism”, is a term used to describe the ability of drugs, acting at the same receptor subtype, to differentially regulate the activity of each of the multiple signaling cascades coupled to the receptor (Urban et al., 2007; Kenakin, 2017; Berg and Clarke, 2018; Michel and Charlton, 2018). The underlying mechanism for functional selectivity is based upon the formation of ligand-specific receptor conformations that are dependent upon ligand structure and that have differential ability to regulate various cellular signal transduction molecules. Consequently, it should not be expected that all ligands and/or ligand-pairs that preferentially activate DOP-KOP heteromers in peripheral sensory neurons will produce the same signaling repertoire and therefore have the same antinociceptive efficacy. Additional experiments are needed to explore the signaling and behavioral consequences of ligands that act at the DOP-KOP heteromer. In this regard, it is noteworthy that allosteric regulators of GPCRs have been shown to alter the functional selectivity signaling profile of orthosteric ligands (Christopoulos et al., 2014). For receptor heteromers, an orthosteric ligand for one protomer of a heteromer can act as an allosteric regulator of the activity (affinity and/ or efficacy) of the orthosteric ligand for the second protomer (Fuxe et al., 2010; Smith and Milligan, 2010; Jacobs et al., 2018). As mentioned above, the efficacy of 6’-GNTI at DOP-KOP heteromers is due to its occupancy of DOP that allosterically augments its agonist actions at KOP (Jacobs et al., 2018). Similarly, the efficacy of the KOP agonist, ICI-199441 is augmented by occupancy of DOP within the heteromer by naltrindole (Jacobs et al., 2018). Although signaling profiles of various ligands or ligand pairs that act at the DOP-KOP heteromer may be different as a result of inter-protomer allosterism, such differences can be a benefit for drug development as it may allow for fine-tuning of drug effects to maximize therapeutic benefit and minimize adverse effects.

5. Conclusion

In summary, DOP-KOP heteromers in peripheral pain-sensing neurons display distinct signaling and functional characteristics in comparison to DOP or KOP. In contrast to DOP or KOP, activation of DOP-KOP heteromers did not elicit desensitization of cAMP signaling in peripheral sensory neuron cultures. Further, although DOP and KOP antinociceptive efficacy was transient following carrageenan-induced inflammation, DOP-KOP heteromers maintained responsiveness for reduction of thermal nociception for a prolonged period of time. Overall, these results suggest that peripheral DOP-KOP heteromers may serve as novel therapeutic targets for treatment of pain.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

By contrast to peripheral DOP or KOP:

Agonist activation of peripheral DOP-KOP heteromers does not produce desensitization of Gi-protein signaling.

Responsiveness of peripheral DOP-KOP heteromers is maintained under prolonged inflammatory conditions.

Peripheral DOP-KOP heteromers are resistant to inhibitory effects of LOX metabolites.

Peripheral DOP-KOP heteromers may be promising targets for new analgesic drugs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. Lakshmi Devi, Laura Sullivan and Peter LoCoco for helpful discussions.

Funding

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service grants from the National Institutes of Health: The National Institute on General Medicine [R01 GM 106035] and the National Institute on Drug Abuse [R21 DA037572] to WPC and KAB; the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Training Grant [T32DE14318]) to BAJ; and National Institute on Neurological Disorders and Stroke Training Grant [T32NS082145] to MMP. RJJ was supported in part by the Translational Science Training program at UTHSCSA (TST128233).

Abbreviations:

- 6-GNTI

6’-guanidinonaltrindole

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- BK

bradykinin

- CARRA

carrageenan

- DOP

delta opioid receptor

- DPDPE

[D-Pen2,5]-Enkephalin

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- GPCR

G-protein coupled receptor

- HETE

Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid

- i.pl

intraplantar

- KOP

kappa opioid receptor

- LOX

lipoxygenase

- MOP

mu opioid receptor

- NTI

naltrindole

- PGE2

prostaglandin E2

- PWL

paw withdrawal latency

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest with the subject matter or materials in this manuscript.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.02.019.

References

- Ahn S, Shenoy SK, Wei H, Lefkowitz RJ, 2004. Differential kinetic and spatial patterns of beta-arrestin and G protein-mediated ERK activation by the angiotensin II receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 35518–35525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angers S, Salahpour A, Bouvier M, 2002. Dimerization: an emerging concept for G protein-coupled receptor ontogeny and function. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 42, 409–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azzi M, Charest PG, Angers S, Rousseau G, Kohout T, Bouvier M, Pineyro G, 2003. Beta-arrestin-mediated activation of MAPK by inverse agonists reveals distinct active conformations for G protein-coupled receptors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 11406–11411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellot M, Galandrin S, Boularan C, Matthies HJ, Despas F, Denis C, Javitch J, Mazeres S, Sanni SJ, Pons V, Seguelas MH, Hansen JL, Pathak A, Galli A, Senard JM, Gales C, 2015. Dual agonist occupancy of AT1-R-alpha2C-AR heterodimers results in atypical Gs-PKA signaling. Nat. Chem. Biol. 11, 271–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KA, Clarke WP, 2018. Making sense of pharmacology: inverse agonism and functional selectivity. Int. J. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21, 962–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KA, Patwardhan AM, Sanchez TA, Silva YM, Hargreaves KM, Clarke WP, 2007. Rapid modulation of mu-opioid receptor signaling in primary sensory neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 321, 839–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KA, Rowan MP, Gupta A, Sanchez TA, Silva M, Gomes I, McGuire BA, Portoghese PS, Hargreaves KM, Devi LA, Clarke WP, 2012. Allosteric Interactions between delta and kappa opioid receptors in peripheral sensory neurons. Mol. Pharmacol. 81, 264–272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg KA, Rowan MP, Sanchez TA, Silva M, Patwardhan AM, Milam SB, Hargreaves KM, Clarke WP, 2011. Regulation of kappa-opioid receptor signaling in peripheral sensory neurons in vitro and in vivo. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 338, 92–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Gainetdinov RR, Peppel K, Caron MG, Lin FT, 1999. Enhanced morphine analgesia in mice lacking beta-arrestin 2. Science 286, 2495–2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouvier M, 2001. Oligomerization of G-protein-coupled transmitter receptors. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 274–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruchas MR, Land BB, Aita M, Xu M, Barot SK, Li S, Chavkin C, 2007. Stress-induced p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation mediates kappa-opioid-dependent dysphoria. J. Neurosci. 27, 11614–11623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JJ, Dymshitz J, Vasko MR, 1997. Regulation of opioid receptors in rat sensory neurons in culture. Mol. Pharmacol. 51, 666–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopoulos A, Changeux JP, Catterall WA, Fabbro D, Burris TP, Cidlowski JA, Olsen RW, Peters JA, Neubig RR, Pin JP, Sexton PM, Kenakin TP, Ehlert FJ, Spedding M, Langmead CJ, 2014. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. XC. multisite pharmacology: recommendations for the nomenclature of receptor allosterism and allosteric ligands. Pharmacol. Rev. 66, 918–947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English JM, Cobb MH, 2002. Pharmacological inhibitors of MAPK pathways. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 23, 40–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferre S, Casado V, Devi LA, Filizola M, Jockers R, Lohse MJ, Milligan G, Pin JP, Guitart X, 2014. G protein-coupled receptor oligomerization revisited: functional and pharmacological perspectives. Pharmacol. Rev. 66, 413–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fields HL, Emson PC, Leigh BK, Gilbert RF, Iversen LL, 1980. Multiple opiate receptor sites on primary afferent fibres. Nature 284, 351–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxe K, Marcellino D, Borroto-Escuela DO, Frankowska M, Ferraro L, Guidolin D, Ciruela F, Agnati LF, 2010. The changing world of G protein-coupled receptors: from monomers to dimers and receptor mosaics with allosteric receptor-receptor interactions. J. Recept. Signal Transduct. Res. 30, 272–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gainetdinov RR, Premont RT, Bohn LM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG, 2004. Desensitization of G protein-coupled receptors and neuronal functions. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 107–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaitonde SA, Gonzalez-Maeso J, 2017. Contribution of heteromerization to G protein-coupled receptor function. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 32, 23–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes I, Ayoub MA, Fujita W, Jaeger WC, Pfleger KD, Devi LA, 2016. G protein-coupled receptor heteromers. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 56, 403–425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes I, Fujita W, Gupta A, Saldanha SA, Negri A, Pinello CE, Eberhart C, Roberts E, Filizola M, Hodder P, Devi LA, 2013. Identification of a mu-delta opioid receptor heteromer-biased agonist with antinociceptive activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 110, 12072–12077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves K, Dubner R, Brown F, Flores C, Joris J, 1988. A new and sensitive method for measuring thermal nociception in cutaneous hyperalgesia. Pain 32, 77–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs BA, Pando MM, Jennings E, Chavera TA, Clarke WP, Berg KA, 2018. Allosterism within delta opioid-kappa opioid receptor heteromers in peripheral sensory neurons: regulation of kappa opioid agonist efficacy. Mol. Pharmacol. 93, 376–386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidi RJ, Jacobs BA, Sullivan LC, Chavera TA, Saylor RM, Prisinzano TE, Clarke WP, Berg KA, 2015. Functional selectivity of kappa opioid receptor agonists in peripheral sensory neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 355,174–182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joris J, Costello A, Dubner R, Hargreaves KM, 1990. Opiates suppress carrageenan-induced edema and hyperthermia at doses that inhibit hyperalgesia. Pain 43, 95–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly E, Bailey CP, Henderson G, 2008. Agonist-selective mechanisms of GPCR desensitization. Br. J. Pharmacol. 153 (Suppl. 1), S379–S388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenakin T, 2017. Signaling bias in drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 12, 321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo TN, Saul WF, Lau SS, 1987. Carrageenan-stimulated release of arachidonic acid and of lactate dehydrogenase from rat pleural cells. Biochem. Pharmacol. 36, 2405–2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel M, Charlton S, 2018. Biased agonism in drug discovery - is it too soon to choose a path. Mol. Pharmacol. 93, 259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan G, Bouvier M, 2005. Methods to monitor the quaternary structure of G protein-coupled receptors. FEBS J. 272, 2914–2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obara I, Parkitna JR, Korostynski M, Makuch W, Kaminska D, Przewlocka B, Przewlocki R, 2009. Local peripheral opioid effects and expression of opioid genes in the spinal cord and dorsal root ganglia in neuropathic and inflammatory pain. Pain 141, 283–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patwardhan A, Berg K, Akopian A, Jeske N, Gamper N, Clarke W, Hargreaves K, 2005. Bradykinin induces functional competence and trafficking of the Delta opioid receptor in trigeminal nociceptors. J. Neurosci. 25, 8825–8832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pin JP, Neubig R, Bouvier M, Devi L, Filizola M, Javitch JA, Lohse MJ, Milligan G, Palczewski K, Parmentier M, Spedding M, 2007. International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXVII. Recommendations for the recognition and nomenclature of G protein-coupled receptor heteromultimers. Pharmacol. Rev. 59, 5–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raehal KM, Schmid CL, Groer CE, Bohn LM, 2011. Functional selectivity at the mu-opioid receptor: implications for understanding opioid analgesia and tolerance. Pharmacol. Rev. 63, 1001–1019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raehal KM, Walker JK, Bohn LM, 2005. Morphine side effects in beta-arrestin 2 knockout mice. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 314, 1195–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rives ML, Rossillo M, Liu-Chen LY, Javitch JA, 2012. 6’-Guanidinonaltrindole (6’-GNTI) is a G protein-biased kappa-opioid receptor agonist that inhibits arrestin recruitment. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 27050–27054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan MP, Ruparel NB, Patwardhan AM, Berg KA, Clarke WP, Hargreaves KM, 2009. Peripheral delta opioid receptors require priming for functional competence in vivo. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 602, 283–287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozenfeld R, Devi LA, 2007. Receptor heterodimerization leads to a switch in signaling: beta-arrestin2-mediated ERK activation by mu-delta opioid receptor heterodimers FASEB J. 21, 2455–2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozenfeld R, Devi LA, 2011. Exploring a role for heteromerization in GPCR signalling specificity. Biochem. J. 433, 11–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmid CL, Streicher JM, Groer CE, Munro TA, Zhou L, Bohn LM, 2013. Functional selectivity of 6’-guanidinonaltrindole (6’-GNTI) at kappa-opioid receptors in striatal neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 22387–22398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma SK, Jones RM, Metzger TG, Ferguson DM, Portoghese PS, 2001. Transformation of a kappa-opioid receptor antagonist to a kappa-agonist by transfer of a guanidinium group from the 5’- to 6’-position of naltrindole. J. Med. Chem. 44, 2073–2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith NJ, Milligan G, 2010. Allostery at G protein-coupled receptor homo- and heteromers: uncharted pharmacological landscapes. Pharmacol. Rev. 62, 701–725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein C, 2016. Opioid receptors. Annu. Rev. Med. 67, 433–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein C, 2018. New concepts in opioid analgesia. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 27, 765–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein C, Zollner C, 2009. Opioids and sensory nerves. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 495–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stout BD, Clarke WP, Berg KA, 2002. Rapid desensitization of the serotonin(2C) receptor system: effector pathway and agonist dependence. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 302, 957–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LC, Berg KA, Clarke WP, 2015a. Dual regulation of delta-opioid receptor function by arachidonic acid metabolites in rat peripheral sensory neurons. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 353, 44–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LC, Chavera TA, Gao X, Pando MM, Berg KA, 2017. Regulation of delta opioid receptor-mediated signaling and antinociception in peripheral sensory neurons by arachidonic acid-dependent 12/15-lipoxygenase metabolites. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 362, 200–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan LC, Clarke WP, Berg KA, 2015b. Atypical antipsychotics and inverse agonism at 5-HT2 receptors. Curr. Pharmaceut. Des. 21, 3732–3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tohgo A, Choy EW, Gesty-Palmer D, Pierce KL, Laporte S, Oakley RH, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ, Luttrell LM, 2003. The stability of the G protein-coupled receptor-beta-arrestin interaction determines the mechanism and functional consequence of ERK activation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 6258–6267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban JD, Clarke WP, von Zastrow M, Nichols DE, Kobilka B, Weinstein H, Javitch JA, Roth BL, Christopoulos A, Sexton PM, Miller KJ, Spedding M, Mailman RB, 2007. Functional selectivity and classical concepts of quantitative pharmacology. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therapeut. 320, 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldhoer M, Fong J, Jones RM, Lunzer MM, Sharma SK, Kostenis E, Portoghese PS, Whistler JL, 2005. A heterodimer-selective agonist shows in vivo relevance of G protein-coupled receptor dimers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102, 9050–9055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White KL, Scopton AP, Rives ML, Bikbulatov RV, Polepally PR, Brown PJ, Kenakin T, Javitch JA, Zjawiony JK, Roth BL, 2014. Identification of novel functionally selective kappa-opioid receptor scaffolds. Mol. Pharmacol. 85, 83–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter CA, Risley EA, Nuss GW, 1962. Carrageenin-induced edema in hind paw of the rat as an assay for antiiflammatory drugs. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 111, 544–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon S, Seger R, 2006. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase: multiple substrates regulate diverse cellular functions. Growth Factors 24, 21–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Chu J, Qiu Y, Loh HH, Law PY, 2008a. Agonist-selective signaling is determined by the receptor location within the membrane domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 9421–9426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Chu J, Zeng Y, Loh HH, Law PY, 2010a. Yin Yang 1 phosphorylation contributes to the differential effects of mu-opioid receptor agonists on microRNA-190 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 21994–22002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Loh HH, Law PY, 2008b. Beta-arrestin-dependent mu-opioid receptor-activated extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) translocate to nucleus in contrast to G protein-dependent ERK activation. Mol. Pharmacol. 73, 178–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng H, Zeng Y, Zhang X, Chu J, Loh HH, Law PY, 2010b. mu-Opioid receptor agonists differentially regulate the expression of miR-190 and NeuroD. Mol. Pharmacol. 77, 102–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.