Abstract

Social network analysis was used to examine the role of having a mutual biracial friend on cross-race friendship nominations among monoracial sixth grade students (Mage = 10.56 years) in two racially diverse middle schools (n = 385; n = 351). Monoracial youth were most likely to choose same-race peers as friends but more likely to choose biracial than different-race peers as friends, suggesting that racial homophily may operate in an incremental way to influence friendships. Monoracial different-race youth were also more likely to be friends if they had a mutual biracial friend. The findings shed light on the unique role that biracial youth play in diverse friendship networks. Implications for including biracial youth in studies of cross-race friendship are discussed.

Keywords: biracial, cross-race friendship, racial homophily, mutual friends, transitivity, social network analysis

The racial composition of the U.S. population is rapidly changing and schools are becoming more diverse (NCES, 2017). With greater exposure to members of various racial groups comes increasing opportunities for youth to form cross-race friendships. Presumably because of the strong influence of homophily (i.e., similarity), however, friendships are most common among individuals who share the same race (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001). Indeed, a good deal of research indicates that especially during adolescence, youth prefer same-race friends to cross-race friends even when cross-race peers are readily available (e.g., Chen & Graham, 2015; Hamm, Brown, & Heck, 2005; Kao & Joyner, 2004; Munniksma, Scheepers, Stark, & Tolsma, 2017; cf. Bagci, Kumashiro, Smith, Blumberg, & Rutland, 2014).

Despite their relatively low frequency, cross-race friendships are associated with a number of positive social outcomes. For example, monoracial individuals (who belong to one racial or ethnic group) with cross-race friends display less prejudice toward outgroup members (Aboud, Mendelson, & Purdy, 2003; Feddes, Noack, & Rutlland, 2009; Pettigrew, 1997; Turner & Feddes, 2011) and maintain less social distance from members of other racial or ethnic groups (Chen & Graham, 2015). Youth with cross-race friends also demonstrate more social competence (Kawabata & Crick, 2008; Lease & Blake, 2005) and experience less social vulnerability in intergroup contexts (Graham, Munniksma, & Juvonen, 2014; Kawabata & Crick, 2011).

In light of the known benefits of cross-race friendships, the purpose of the present research was to examine factors that might facilitate monoracial adolescents’ willingness to cross racial boundaries in choosing who to befriend. We focused on the role of having a mutual friend (i.e., a friend in common) and hypothesized that biracial mutual friends who share the same race with members of two different racial groups might be in a unique position to facilitate cross-race friendships between monoracial different-race peers. Instead of limiting our analysis to interactions between two peers as in most previous research on cross-race friendships, we used social network analysis to explore the entire set of friendship relations among same- and different-race peers in their school network. Doing so allowed us to take a closer look at not only the individual and dyadic characteristics that predict cross-race friendship but also the structural characteristics of the social networks in which these friendships are embedded that may constrain or foster opportunities for cross-race friendships.

Friendship Selection in Social Networks

Three primary processes govern the selection of friends in social networks. The first process, known as homophily, reflects the tendency for individuals to choose friends who are similar to themselves in socially meaningful ways. According to the literature, homophily is the primary factor in friendship selection, with similarity in gender and race being the most common forms (Hallinan & Williams, 1989; Hamm, 2000; McPherson et al., 2001; Shrum, Cheek, & Hunter, 1988). The theoretical reasons for the strong influence of homophily on friendship include greater ease in communicating, establishing trust, and anticipating behaviors for individuals who are similar to each other compared to individuals who are not (Block, 2015; Hamm, 2000; Werner & Parmelee, 1979).

Because similar individuals can only be chosen as friends to the extent they are available, homophily is often constrained by the next process, propinquity, which asserts that individuals in close proximity to each other are more likely to choose one another as friends (Feld, 1981; McPherson et al., 2001; Wimmer & Lewis, 2010). In the school context, propinquity can be defined as residing in the same school or, more proximally, being in the same classroom. When there is limited availability of similar individuals, homophily and propinquity may operate in the opposite direction to influence friendship selection. For example, the literature has shown that as the availability of different-race peers at school increases (greater propinquity), and the share of one’s own group decreases (less homophily), cross-race friendships increase (Graham et al., 2014; Kao & Joyner, 2004), although the rate of increase does not keep pace with availability (Moody, 2001).

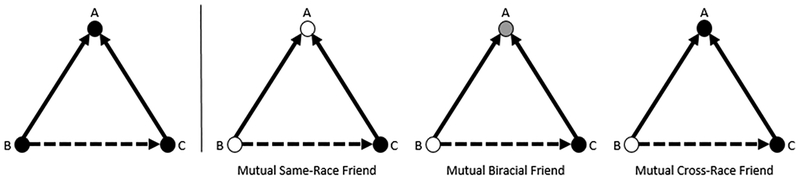

The third process, known as transitivity, reflects the tendency for individuals to choose friends who are the friends of one’s existing friends (Block, 2015; Kossinets & Watts, 2009) and who are therefore more available than others in the network (Mouw & Entwisle, 2006). Transitivity is considered a structural characteristic of a friendship network since the majority of friendships between two individuals appear to be a function of a mutual connection with a third individual (Hallinan, 1974; Louch, 2000). As a network structure, transitivity can be conceptualized as a triangle effect among members of the same social network. The left panel of Figure 1 shows three individuals (represented as circular nodes) in a triangle formation. The solid arrows (edges) B-A and C-A represent friendship nominations given to individual A by individuals B and C. The dashed arrow represents a potential friendship nomination given to C by B who is connected to C by mutual friend A. Transitivity occurs when B nominates C as a friend, in which case A would be considered the mutual friend, connecting two friends in the social network and closing the triangle (Spiro, Acton, & Butts, 2013).

Figure 1.

The role of mutual friends in transitivity in social network structures. Nodes (i.e., endpoints) represent individuals in a social network. Solid arrows (edges) represent existing friendship nominations with the direction of the arrow representing the direction of the nomination. The dashed arrow represents a potential friendship nomination given to an individual who is indirectly connected by a mutual friend. In the right panel of three triangles, the shading of the nodes represents monoracial (white and black) and biracial (gray) individuals. The race of the mutual friend is from the perspective of node B who has a mutual friend A with potential cross-race friend C.

Since the closest way to reach someone else in a network is through a mutual friend, transitivity and propinquity are interrelated network processes. Transitivity also facilitates the spread of homophily since individuals are likely to choose similar others as friends, resulting in the friends of friends being similar to oneself (Goodreau, Kitts, & Morris, 2009; Louch, 2000). For example, two same-race peers with a mutual same-race friend (both displaying racial homophily in their choice of a friend) would likely become friends themselves, increasing the number of racially homophilous ties in the network. On the other hand, two different-race peers might be less likely to have a mutual friend and therefore less likely to become friends themselves (Louch, 2000). The lack of mutual friends could be one reason there are fewer cross-race friendships than expected based on the availability of different-race peers at school.

To summarize, principles of homophily, propinquity, and transitivity operate together to shape friendship choices. Individuals tend to select friends who are similar to themselves (homophily) but always within the constraints of availability (propinquity). Individuals also tend to select friends with whom they share a mutual friend (transitivity), making the friends of friends the most available others in a network.

Biracial Youth as Mutual Friends

Based on recent census reports, biracial and other multiracial individuals are one of the fastest growing racial groups in the United States, with biracial children and youth comprising the largest segment of this group (Humes, Jones, & Ramirez, 2011). In 2013, about 1 in 10 children were born to mixed-race parents (up from 1 in 100 in 1970) and these percentages are expected to triple by 2060 (Pew Research Center, 2015). Despite current and projected increases in population share, however, not much is known about the friendships of biracial youth. The limited empirical research that does exist suggests that biracial youth may be in a structurally advantageous position in their social networks to aid transitivity among cross-race peers.

Using a nationally representative sample of adolescents (Add Health), Doyle and Kao (2007) reported that biracial youth are more likely to choose monoracial than other biracial peers as friends. Friendship patterns of biracial youth also fell somewhere in the middle of friendship patterns of their monoracial counterparts. For example, biracial Black-White youth were more likely than monoracial Black youth but less likely than monoracial White youth to choose a White friend, and they were less likely than monoracial Black youth but more likely than monoracial White youth to choose a Black friend. Using the same sample, Quillian and Redd (2009) reported that biracial youth have more diverse friendship networks than most monoracial youth and often these networks are comprised of the two groups in their racial background. For example, biracial Black-White youth were more likely to have monoracial Black and monoracial White friends than friends from racial or ethnic groups other than Black or White.

Since biracial youth often have friends from both groups that make up their racial background, they are likely to be mutual friends of monoracial different-race peers, increasing the probability of different-race peers becoming friends themselves (Quillian & Redd, 2009). Until now, however, the role of biracial youth in cross-race friendships has not been empirically tested. One reason for this may be the exclusion of biracial youth in much of the interracial friendship literature, presumably due to the lack of consensus about the same- vs. cross-race nature of their friendships with monoracial youth (e.g., Kao & Joyner, 2004; Munniksma & Juvonen, 2012; Quillian & Campbell, 2003). Consider, for example, a biracial Black-White youth with a Black friend. Would this friendship be labeled a same-race friendship since these youth share part of their racial background or would it be labeled a cross-race friendship since they do not share all of their racial background?

In previous research, the categorization of individuals into same- or cross-race friendships has relied on a dichotomous indicator of racial homophily (friends either match or do not match on race). Thus, the confusion about how to classify friendships with biracial youth as same or cross race—when they actually fall somewhere in between—may be the result of a mismatch between the construct being measured and the method being employed to measure it. A more refined measure of racial homophily should be incremental, capturing a range of similarity and dissimilarity in racial background. For example, monoracial friends who matched on race (e.g., two Black friends) would have full racial homophily, and monoracial friends who did not match on race (e.g., one Black friend and one White friend) would have no racial homophily. Friends who shared part of their racial background (e.g., a biracial Black-White youth with a Black or White friend) would have partial racial homophily. Such an incremental measure would provide a way for biracial youth to be included in studies of cross-race friendship and to test hypotheses about their role as mutual friends.

The Present Study

Integrating principles of homophily, propinquity and transitivity in a social network framework, we examined whether having a mutual biracial friend could facilitate cross-race friendships between monoracial peers. We capitalized on a large ethnically diverse middle school sample that included many biracial youth, and we used a new measure of incremental racial homophily that could account for sharing none, part, or all of a potential friend’s race. The presence of friendships between biracial youth and monoracial youth from both groups that made up the biracial youth’s racial background allowed us to examine the influence of having a mutual biracial friend on transitivity among cross-race friends. Our hypotheses were as follows:

Hypothesis 1: Homophily conceptualized as an incremental variable is related to friendships choices. We hypothesized that sharing part of one’s racial background (partial racial homophily) would be more likely to lead to friendship than sharing none of one’s racial background (no racial homophily), and sharing all of one’s racial background (full racial homophily) would be more likely to lead to friendship than sharing part of one’s racial background. In other words, although we expected friendships among monoracial same-race peers to be more likely than friendships among monoracial and biracial peers (who only shared part of their racial background), we expected friendships among monoracial and biracial peers to be more likely than friendships among monoracial different-race peers.

Hypothesis 2: Based on the principle of transitivity, we expected that friendships would be more likely among monoracial different-race peers with any mutual friend than monoracial different-race peers without a mutual friend. More specifically, we further hypothesized that the effect of having a mutual friend would be strongest when the mutual friend was biracial, having partial racial homophily with both monoracial different-race peers.

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a social network analysis of sixth grade students’ friendship nominations in two middle schools that were very racially diverse. In such schools, monoracial youth have opportunities for friendship with peers from a variety of racial groups, including biracial youth. We also examined homophilous predictors of cross-race friendships such as similarity in gender, academic achievement (Chen & Graham, 2015; Hamm et al., 2005), and peer reputation (Echols & Graham, 2013) that were included as covariates in our analysis. Since friendships choices are constrained by availability (propinquity) of potential friends (McPherson et al., 2001) and sharing classes with peers is associated with friendship nominations (Clark & Ayers, 1988; Hallinan & Williams, 1989), we developed a new index of propinquity based on students’ class schedules that measured each participant’s exposure to their sixth grade peers throughout the school day. This allowed us to account for availability in a more dynamic way—unique for every participant—than has been done in previous research (see Echols & Graham, 2016; Juvonen, Kogachi, & Graham, 2018). Lastly, we included other network covariates (e.g., indegree, two-paths, reciprocity; described below) standard in most social network analyses.

We focused on sixth grade students who had recently started middle school for two reasons. First, the middle school transition coincides with the beginning of a developmental period in which both friendships and race take on heightened significance (Brechwald & Prinstein, 2011; Umaña-Taylor et al., 2014). Compared to elementary school, cross-race friendships are less frequent (Aboud et al., 2003); and since they may continue to decline in mid- to late adolescence (see Hallinan & Williams, 1989), understanding factors that promote cross-race friendships in early adolescence may be key in preventing this decline. Second, middle schools are typically much larger and farther away from their neighborhood feeder elementary schools (Juvonen, Le, Kaganoff, Augustine, & Constant, 2004), making this school transition an ideal context for studying early adolescents in the process of forming new friendships.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a larger longitudinal study of ethnic diversity and peer relations across 3 cohorts of approximately 6,000 sixth graders in Northern and Southern California. Students were enrolled in one of 26 schools carefully selected to represent a variety of racial or ethnic compositions, within the constraints of a public school system that is majority Latino. Six schools were diverse such that no single group represented a numerical majority in the population, and members of each of 4 major pan-ethnic groups (i.e., African American, Asian, Latino, and White) were present in the student population. Ten schools had 2 large and relatively equal groups (e.g., Latino and Asian) with very few members of other groups. Ten other schools had a clear racial or ethnic majority group with a smaller number of members from each of the other groups. To reduce confounds of racial or ethnic diversity with socioeconomic status (SES), schools at the extremes of the SES continuum were avoided; only schools within a 20–80% range of free or reduced price lunch eligibility were recruited for the study.

Beginning in the fall of 2009, research assistants visited sixth grade classrooms in participating schools and made a brief presentation before handing out parental consent forms and informational letters explaining the study. To increase participation, students who returned consent forms (either allowing or not allowing study participation) were entered into a raffle for a $50 gift card. Recruitment rates ranged from 63 to 95% (M = 82%) across the 3 cohorts of students beginning in the 2009–2010 school year and continuing into the 2010–2011 and 2011–2012 school years. Participation rates ranged from 74 to 94% (M = 83%). This study was conducted in compliance with all ethical guidelines for research with human subjects and approved by the Institutional Review Board at UCLA (Protocol ID: 11–002066).

Several selection criteria determined our choice of schools (networks) for this study. We wanted to maximize opportunities for monoracial youth to have biracial friends and cross-race friends from various other racial or ethnic groups and for biracial youth to have friends from both groups in their racial background. Therefore, only schools with all four major pan-ethnic groups represented in the student population as well as a biracial student population of at least 10% were selected for this study. In social network analysis, the more informants who report on relations within the network, the more accurately the data reflect the true network structure. Thus, social network analysis relies on a census (not just a sample) of the population, making high participation rates in any given network necessary (Hanneman & Riddle, 2005). Since each school represents a separate population (i.e., network) of students, only schools with recruitment and participation rates both exceeding 80% were selected. Two schools from the larger study met the above criteria.

The racial or ethnic composition of the sample was based on student self-report. Students were asked to select their race or ethnicity from the following options: American Indian, Black/African American, Black/other country of origin, East Asian, Latino, Mexican/Mexican American, Middle Eastern, Pacific Islander (including Filipino), South Asian, Southeast Asian, White/Caucasian, Multiethnic/Biracial, and Other. Students who selected Multiethnic/Biracial or Other were asked to specify their racial or ethnic background. For the present study, some groups were combined (Black/African American and Black/other country of origin, East Asian and Southeast Asian, and Latino and Mexican/Mexican American).

In School 1, the racial or ethnic composition of the sixth grade sample (n = 385) was 36% Latino/Mexican American, 18% White/Caucasian, 16% Black/African American, 7% East/Southeast Asian, 3% South Asian, 2% Middle Eastern, 1% Other, <1% Filipino/Pacific Islander, and 17% Multiethnic/Biracial. In School 2, the racial or ethnic composition of the sixth grade sample (n = 351) was 34% Latino/Mexican American, 19% Black/African American, 13% White/Caucasian, 9% East/Southeast Asian, 3% South Asian, 2% Filipino/Pacific Islander, 2% Middle Eastern, 2% Other, and 16% Multiethnic/Biracial. In both schools, no participants who selected Multiethnic/Biracial specified more than two racial or ethnic groups. Middle schools selected for this study were similar in overall size (NSchool1 = 1,567; NSchool2 = 1,699) and SES based on percent free or reduced lunch (42% and 43%, respectively).

Procedure

Students with signed parental consent completed a questionnaire during a single period in one of their sixth grade classes of the fall semester. Students recorded their answers independently as they followed instructions being read aloud by a graduate research assistant who reminded them of the confidentiality of their responses. A second researcher circulated around the classroom to help students as needed. Students were given an honorarium of $5 for completing the questionnaire.

Measures

Friendship.

As part of a larger peer nomination protocol, students were instructed to record the names of their “good friends” in sixth grade at the same school. Students were allowed to nominate as many friends as they desired (MSchool1 = 3.37, MSchool2 = 2.96). One advantage of social network analysis is its ability to account for all friendship nominations given and received—instead of relying solely on the perspective of the focal actor (nominator), it takes into account whether or not nominations were reciprocated.

All participants were entered into a matrix (every participant by every other participant within the same school). Friendship nominations given to other participants were recorded as a “1” in the matrix, and all remaining values (i.e., no friendship nomination given) were set to “0.” In social network terminology, matrix cells with a value of 1 are referred to as edges and represent the presence of a friendship tie between two members of the network. Since friendship nominations given were not always reciprocated by the nominees, the matrix was not symmetrical, making the corresponding friendship network a directed network.

Racial homophily.

In order to approximate the incremental nature of racial or ethnic homophily, the degree of racial similarity among all dyad partners was measured using a series of dummy variables. First, participants were assigned two categorical values for race. For monoracial participants, these values were the same for both categories. For biracial participants, these values represented the two categories that made up their racial background. Then, participants received a score of “0” or “1” on three separate dummy-coded variables depending on whether each dyad partner (potential friend) shared all the nominator’s race (full racial homophily), half the nominator’s race (partial racial homophily), or none of the nominator’s race (no racial homophily). No racial homophily served as the reference category. To illustrate, a monoracial Black participant paired with another monoracial Black dyad partner would receive a “1” on the “full racial homophily” variable, a “0” on the “partial racial homophily” variable, and a “0” on the “no racial homophily” variable. The same Black participant paired with a biracial Black/White dyad partner would receive a “0” on the “full racial homophily” variable, a “1” on the “partial racial homophily” variable, and a “0” on the “no racial homophily” variable. The same Black participant paired with a monoracial White dyad partner would receive a score of “0” on the “full racial homophily” variable, a “0” on the “partial racial homophily” variable, and a “1” on the “no racial homophily” variable.

Mutual friends.

Since social network models are interpreted from the perspective of the nominator who chooses or does not choose the dyad partner as a friend, we focused on the number of shared friends for each dyad based on nominations given. The race of the dyad partner determined what type of mutual friends dyad partners could have. For monoracial cross-race dyads, mutual friends were divided into four categories. The first three categories are graphically depicted in the three triangles in the right panel of Figure 1: (1) the number of shared friends who matched the race of the nominator but not the nominee, labeled mutual same-race friends (1st triangle); (2) the number of shared friends who matched half the race of the nominator and half the race of the nominee, labeled mutual biracial friends (2nd triangle); (3) the number of shared friends who matched the race of the nominee but not the nominator, labeled mutual cross-race friends (3rd triangle); and (4) all other mutual friends (e.g., shared friends who matched neither the race of the nominator nor nominee). For same-race dyads, the number of shared friends based on nominations given was simply represented by the total number of mutual friends. All mutual friends for all participants were accounted for using these categories.

Dyadic covariates.

Each participant was paired with every other participant—regardless of friendship status—in order for the characteristics of all potential friends to be measured. As such, participants appeared in a list of dyads as both nominators and nominees.

Gender homophily.

Participants received a score of “0” or “1” depending on whether each dyad partner (nominee) matched their self-reported gender.

Academic achievement homophily.

Previous research suggests that similarities in academic achievement between youth from different racial or ethnic groups may promote the development of cross-race friendships (Chen & Graham, 2015; Hamm et al., 2005). To account for this possibility, a homophily score was calculated for all participants and their dyad partners (i.e., potential friends) based on grade-point average (GPA) for participants’ academic courses. Official semester grades were provided by participants’ schools and GPA was computed on a 4.0 scale. To compute the homophily score, absolute value differences in GPA were calculated and transformed by subtracting the difference score from the largest possible absolute value difference. A score of zero represented the largest possible difference in GPA (no homophily) and a score of four represented the largest possible similarity in GPA.

Peer social status and reputation homophily.

Previous research also documents that cross-race friendships are associated with similarities in peer reputations (Echols & Graham, 2013; Hamm, 2000). Thus, as part of the peer nomination procedure for friendships described above, students were asked to nominate the students in their grade who they liked to hang out with (peer acceptance), who they did not like to hang out with (peer rejection), who were picked on by others (peer victimization), and who picked on others (peer aggression). The total nominations received by participants was tallied for each peer reputation category and the difference between participants and each dyad partner was calculated and transformed by subtracting the difference score from the largest absolute value difference in the same school. A score of zero represented the largest possible difference in nominations received. As scores increased, so did homophily in nominations received.

Shared classes.

Although participants in the same network attended the same school, opportunities for friendship may have been influenced by the extent of exposure participants had to each other throughout the school day. For this reason, the number of classes shared by dyad partners was calculated as a measure of availability. Using fall course schedules provided by participants’ schools, a matrix for each period of the school day was created. Dyad partners received a score of “0” if they did not share the same class for a given period and a score of “1” if they did share the same class for that period. Then the values for each dyad across matrices were added. Since matrix values were the same for both members of each dyad, the resulting matrix was symmetrical.

Network characteristics.

A number of network covariates were included in each model to account for the most commonly occurring structural network characteristics that predict friendship.

Indegree.

To control for the possibility that the number of incoming friendship nominations (i.e., nominations received) could influence the number of outgoing friendship nominations made (i.e., nominations given), an indegree score was calculated for each participant to represent the total friendship nominations received. Commonly used as a measure of popularity, indegree reflects a general tendency for participants who receive friendship nominations to give friendship nominations.

Reciprocity.

Often referred to as mutuality, this network effect takes into account the tendency of friendship nominations to be reciprocated. By including this effect, the model estimates the change in likelihood of nominating another member of the network as a friend if a friendship nomination was received by that member.

Two-paths.

This network effect is a prerequisite for transitivity (i.e., triangles in a network) as it calculates the count of network members that are connected to two other (but disconnected) members. Because there is a strong tendency for the friends of friends to become friends themselves (i.e., form a triangle), this effect is often negative.

Results

Using social network analysis, we examined the complex set of network characteristics and friendship relations between monoracial same-race, monoracial cross-race, and biracial youth in two middle schools. Table 1 provides descriptive information for the friendship nominations given to members of each racial or ethnic group in each school network. Numbers in bold on the diagonal represent same-race nominations. Consistent with previous research, monoracial participants gave the majority of friendship nominations to same-race peers in both schools. Biracial participants gave nearly as many or more friendship nominations to monoracial compared to other biracial peers.

Table 1.

Friendship Nominations Given by Racial/Ethnic Group

| School 1 | Racial/Ethnic Group of Nominees | ||||

| Racial/Ethnic Group of Nominators | Af. Amer./Black | E/SE Asian | White | Latino/Mexican | Biracial |

| African American/Black | 72 | 4 | 25 | 36 | 55 |

| East/Southeast Asian | 7 | 24 | 21 | 12 | 19 |

| White | 16 | 19 | 99 | 47 | 51 |

| Latino/Mexican | 58 | 10 | 57 | 223 | 67 |

| Biracial | 45 | 16 | 45 | 50 | 51 |

| School 2 | Racial/Ethnic Group of Nominees | ||||

| Racial/Ethnic Group of Nominators | Af. Amer./Black | E/SE Asian | White | Latino/Mexican | Biracial |

| African American/Black | 68 | 5 | 24 | 41 | 49 |

| East/Southeast Asian | 9 | 32 | 13 | 23 | 11 |

| White | 27 | 11 | 38 | 11 | 23 |

| Latino/Mexican | 44 | 18 | 24 | 162 | 46 |

| Biracial | 51 | 13 | 20 | 48 | 31 |

Note. Numbers in bold represent same-race nominations. Monoracial groups that comprised less than 3% of the school population are not shown here.

Exponential random graph models (ERGMs) were employed using R 3.3.3 (R Core Team, 2017) in order to assess the likelihood of a participant nominating a dyad partner as a friend, resulting in a value of “1” in the friendship nomination matrix. In general, these models are used to define the set of “selection forces” that influence the formation of friendship and other ties in social settings such as schools (Hunter, Handcock, Butts, Goodreau, & Morris, 2008). Within a network analysis framework, ERGMs function much like logistic regression models since the outcome variable is dichotomous (e.g., a friendship nomination given or not). Compared to logistic regression models, however, ERGMs have relaxed assumptions regarding the independence of the data (e.g., individuals have the opportunity to be friends with more than one other member of the network and therefore may appear in more than one dyad). As such, all friendships occurring within the same social network can be observed simultaneously. As is common in the social network literature, a separate but identical analysis was conducted for each school since nominations can only be given or received within (not across) networks (e.g., de la Haye, Robins, Mohr, & Wilson, 2010). In addition, because networks typically vary in size (e.g., the number of students differs from school to school), opportunities for friendship are unique to each network; thus, network measures can only reliably predict friendship nominations for one network at a time.

Network and Dyadic Predictors of Friendship

Table 2 contains the results for the social network analysis performed for each school. All predictors were entered into each model simultaneously and the coefficients in each model represent the log odds likelihood of choosing a dyad partner as a friend holding all other variables constant. Log odds values range from negative to positive infinity, with a value of zero representing a .5 probability (i.e., 50–50 chance). Negative values represent a likelihood smaller than chance (i.e., an unlikely occurrence) while positive values represent a likelihood greater than chance. In large networks, the probability of a friendship nomination between any two randomly chosen individuals is usually small, resulting in a negative log odds. Not surprisingly, in both schools, the friendship (edges) term was large and negative (−7.28 and −7.12 for Schools 1 and 2, respectively) indicating a low probability of choosing a random dyad partner as a friend when all predictors in the model had a value of zero (e.g., dyad partners did not match on sex or race and had no mutual friends).

Table 2.

Log Odds of a Choosing a Friend Based on Racial Homophily and Mutual Friends

| School 1 | School 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | S.E. | Estimate | S.E. | |

| −7.28 | 0.14*** | −7.12 | 0.15*** | |

| Biracial | 0.00 | 0.10 | 0.05 | 0.11 |

| Structural and Dyadic Effects | ||||

| Indegree | 0.19 | 0.01*** | 0.20 | 0.01*** |

| Reciprocity | 3.45 | 0.12*** | 3.21 | 0.14*** |

| Two-paths | −0.26 | 0.02*** | −0.25 | 0.02*** |

| Gender Homophily | 1.99 | 0.11*** | 1.60 | 0.10*** |

| Academic Achievement Homophily | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| Peer Acceptance Homophily | 0.05 | 0.01*** | 0.05 | 0.01*** |

| Peer Rejection Homophily | −0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| Peer Victimization Homophily | −0.01 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| Peer Aggression Homophily | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| Shared Classes | 0.58 | 0.02*** | 0.41 | 0.02*** |

| Racial Homophily | ||||

| Partial Homophily | 0.35 | 0.13** | 0.62 | 0.14*** |

| Full Homophily | 0.74 | 0.08*** | 0.78 | 0.09*** |

| Mutual Friendship Nominations Received | 0.92 | 0.06*** | 0.99 | 0.08*** |

| Mutual Friendship Nominations Given | ||||

| No Racial Homophily (Cross-Race) Dyads | ||||

| Mutual Friends | 1.27 | 0.07*** | 1.42 | 0.09*** |

| Mutual Cross-Race Friends (race matches nominee) | 1.49 | 0.17*** | 1.87 | 0.20*** |

| Mutual Biracial Friends | 1.00 | 0.18*** | 0.92 | 0.20*** |

| Mutual Same-Race Friends (race matches nominator) | 0.77 | 0.19* | 0.50 | 0.23* |

| Partial Racial Homophily (Mono- to Biracial) Dyads | ||||

| Mutual Friends | −0.06 | 0.14 | −0.52 | 0.17** |

| Mutual Biracial Friends | 0.77 | 0.19* | 0.51 | 0.42 |

| Full Racial Homophily (Same-Race) Dyads | ||||

| Mutual Friends | −0.17 | 0.10 | −0.45 | 0.14*** |

Note. S.E. = Standard Error.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001.

Edges term represents the log odds likelihood of choosing a friend when all predictors in the model had a value of zero. In order to interpret the model from the perspective of a monoracial participant as the nominator, a dummy variable for biracial (0=monoracial) was included in the model.

The next set of coefficients in Table 2 display significant network structural and dyadic effects, which were similar across schools. Indegree had a small positive effect, suggesting that receiving nominations was associated with an increased likelihood of giving nominations. Reciprocity had a large positive effect, meaning that being nominated as a friend by a particular dyad partner was associated with an increased likelihood of nominating that same dyad partner as a friend. As predicted, the two-path effect was negative, indicating that dyad partners with mutual friends had a greater likelihood of becoming friends themselves than remaining disconnected (though indirectly connected by a mutual friend). These network effects—included as the standard set of covariates in social network models—simply reflect the structural conditions under which many network ties exist irrespective of other exogenous forces acting on the network.

The effect of gender homophily was large and positive, demonstrating the tendency for same-gender dyads to be friends. Academic achievement homophily did not affect the likelihood of choosing a friend, nor did homophily in peer rejection, victimization, or aggression. However, peer acceptance homophily was associated with a greater likelihood of choosing a dyad partner as a friend. In other words, participants were more likely to choose friends who were similar to them in peer acceptance. The likelihood of choosing a dyad partner as a friend also significantly increased as the number of classes shared by dyad partners increased, suggesting that exposure to peers in classes throughout the day is important for making friends in middle school.

Hypothesis 1: The Incremental Nature of Racial Homophily

The first objective of this study was to examine whether racial homophily operates in an incremental way to influence the likelihood of choosing a friend. In past research on same- and cross-race friendships, racial homophily has been treated as a dichotomous characteristic of friendships, with potential friends (dyad partners) either sharing or not sharing the same race. In the present study, racial homophily was measured using a set of dummy variables representing partial and full racial homophily within each dyad, with no racial homophily serving as the reference category. This allowed for monoracial and biracial participants to be included in our analysis.

Following the network and dyadic effects described above, the next set of coefficients in Table 2 shows the log odds of nominating a dyad partner as a friend based on racial homophily, assuming no mutual friends. By transforming log odds into odds ratios, the results can be interpreted as how much more likely a nominator would be to choose a dyad partner as a friend when the dyad partner shares part or all of the nominator’s race compared to when the dyad partner shares no part of the nominator’s race. In School 1, partial racial homophily (compared to no racial homophily) was associated with an increase of .35 in the log odds of choosing a friend (1.42 times more likely), and full racial homophily was associated with an increase of .74 in the log odds of choosing a friend (2.10 times more likely). In School 2, partial racial homophily was associated with an increase of .62 in the log odds of choosing a friend (1.86 times more likely), and full racial homophily was associated with an increase of .78 in the log odds of choosing a friend (2.18 times more likely). Thus, the findings provide support for our hypothesis that racial homophily operates in an incremental fashion, with some mattering more than none, and all mattering the most.

Hypothesis 2: The Role of Mutual Friends in Cross-Race Friendships

The primary goal of this study was to examine the effect of having a mutual friend on monoracial youth choosing a cross-race dyad partner as a friend and examine whether this effect differed depending on the race of the mutual friend. The relevant coefficients in Table 2 are those for Mutual Friends under No Racial Homophily (Cross-Race) Dyads. Those coefficients show the odds of nominating a dyad partner as a cross-race friend based on having a mutual friend who was same-race (i.e., the race of the nominator; 2nd triangle in Figure 1), biracial (i.e., shared half the race of the nominator and half the race of the dyad partner; 3rd triangle), or cross-race (i.e., the race of the dyad partner, 4th triangle). We hypothesized that the mutual friend effect would be strongest for mutual biracial friends. Our hypothesis was only partly supported. In both schools the mutual friend effect was strongest when the race of the mutual friend matched the race of the dyad partner (mutual cross-race friend), next strongest when the race of the mutual friend matched half the race of the nominator and half the race of the dyad partner (mutual biracial friend; our Hypothesis 2), and weakest when the race of the mutual friend matched the race of the nominator (mutual same-race friend). Based on log odds of 1.49 and 1.87, participants were 4.44 and 6.49 times more likely (respectively) to choose a dyad partner as a friend if they had a mutual cross-race friend; 2.72 and 2.51 times more likely (respectively) to choose a dyad partner as a friend if they had a mutual biracial friend (based on log odds of 1.00 and 0.92); and 2.16 and 1.65 times more likely (respectively) to choose a dyad partner as a friend if they had a mutual same-race friend (based on log odds of 0.77 and 0.50).

Although our goal was to examine the role of mutual friends on cross-race friendship nominations between monoracial different-race peers, we accounted for the influence of mutual friends on all types of friendship nominations. The remaining coefficients in Table 2 show the odds of nominating a dyad partner as a friend based on having a mutual friend when the dyad partner was biracial (in which case the mutual friend shared half of the nominator’s race and all of the dyad partner’s race) and when the dyad partner was the same race (in which case the mutual friend was also the same race).

To summarize, incremental racial homophily was a significant predictor of friendships (Hypothesis 1). While sharing all of one’s race with the dyad partner was associated with the greatest likelihood of a friendship nomination, sharing half of one’s race with the dyad partner was still more likely to result in a friendship nomination than not sharing any of one’s race. Having a mutual friend was also strongly associated with friendships (Hypothesis 2). For cross-race dyads, having a mutual biracial friend who shared half the race of the nominator and half the race of the dyad partner significantly increased the likelihood of choosing the dyad partner as a friend, but having a mutual friend was most likely to result in choosing the dyad partner as a friend when the mutual friend was the same race as the dyad partner.

Discussion

Our study offers new insights into the underlying processes that govern friendship selection among different-race peers in social networks typically dominated by friendships between same-race peers. Until now, the interracial friendship literature has relied on a dichotomous indicator of racial homophily to determine same- or cross-race friendship status, excluding biracial youth from most empirical studies. Our novel measure of racial homophily which accounted for partial homophily allowed us to not only include biracial youth in our sample but also make them a central focus of our analysis. As hypothesized, full racial homophily was more predictive of friendship than partial or no racial homophily, and partial racial homophily was more predictive of friendship than no racial homophily.

Stronger than the homophily effects, however, were the effects of having a mutual friend. Regardless of type (same-race, biracial, cross-race), having a mutual friend was a significant predictor of friendship nomination, particularly for nominations given to different-race peers, demonstrating the importance of including transitivity in research on cross-race friendships. Using the role of partial homophily in transitivity as an example, having a mutual biracial friend was positively associated with cross-race friendship nominations. In other words, a biracial friend increased the likelihood of friendship between two monoracial cross-race friends, each of whom shared part of their biracial friend’s race. This pattern of findings was replicated in two ethnically diverse middle schools. To our knowledge, this study is the first of its kind to examine the role of mutual biracial friends—or any other mutual friends—in cross-race friendship choices.

Beyond the role of partial homophily in transitivity, why might having a mutual biracial friend increase the likelihood of choosing a cross-race peer as a friend? Previous research demonstrates that extended contact (i.e., having a friend with a cross-race friend) may lead to more positive outgroup attitudes which, in turn, leads to direct contact (i.e., having a cross-race friend oneself; Cameron, Rutland, Hossain, & Petley, 2011). Thus, mutual friends may serve as liaisons, spreading important information and attitudes from one group to another (see Spiro et al., 2013). Since biracial youth often have more positive intergroup attitudes than monoracial youth (Kang & Bodenhausen, 2015), extended contact via biracial friends may be especially likely to promote cross-race friendships.

Despite the significant influence of a mutual biracial friend, however, having a mutual cross-race friend from the same racial group as the cross-race dyad partner had a stronger effect on cross-race friendships in our sample. For example, if nominator B (see 4th triangle in right panel of Figure 1) was Asian and potential friend C was White, B would be more likely to befriend C if their mutual friend A was also White. Previous research suggests that homophily is inversely related to social distance, or the number of ties it would take to get to someone else in the network (Marsden, 1988; McPherson et al., 2001). Since racial homophily is so prevalent in friendship networks, same-race peers are likely to be closely connected in the same region of the network, such that the social distance between any two same-race peers would be small. For a monoracial youth (such as nominator B from the example above) who already had one friend from a different racial group (friend A), the social distance between that youth and other cross-race friends from group A (e.g., friend C) would therefore also likely be small. In other words, once a monoracial youth has already crossed the racial boundary to form a cross-race friendship, the distance to the next cross-race friend from that group would be far shorter. This could explain why having a cross-race mutual friend was the strongest predictor of choosing a(nother) cross-race friend from the same racial group. For a monoracial youth with no existing cross-race friends, however, having a mutual biracial friend could be a “shortcut” to reaching a potential cross-race friend in another region of the network. Because of their central position, biracial youth may therefore be critical for first cross-race friendships among their monoracial different-race peers.

Although not the focus of our analysis, we included a number of dyadic covariates as predictors of friendship choices. In addition to gender homophily, another strong predictor of friendship was availability (propinquity) based on the number of classes shared by two youth (dyad partners) in the same school. Most previous research on cross-race friendships has relied on school-level racial or ethnic composition or diversity as the measure of availability. However, these measures may not be sensitive enough to capture the influence of availability of different-race peers on cross-race friendships since racialized tracking may result in substantial differences in racial composition between classrooms in the same school (Hamm, 2000; Oakes, 2005). For middle school youth who rotate classes with a select number of classmates during the school day, our measure of shared classes may represent the true availability of cross-race peers at school. Other innovative measures that capture everyday shared spaces in youth’s peer ecologies may provide additional insight into the role of propinquity in cross-race friendships. For example, Knifsend and Juvonen (2017) measured the availability of cross-race peers in extracurricular activities as predictors of cross-race friendships, whereas Echols, Solomon, and Graham (2014) used observational methods to track availability of cross-race ties in the middle school cafeteria. We recognize there are multiple contexts outside of the traditional classroom where cross-race friendships develop and flourish.

Contrary to previous studies, similarity in academic achievement was not associated with a significant increase in the likelihood of friendship nominations. Why would this effect be less pronounced in the present study? Since transitivity may perpetuate homophily among friends (Goodreau et al., 2009; Louch, 2000), homophily effects may be inflated in studies that do not account for interdependencies in the network. As a result, what appears to be a homophily effect (e.g., choosing friends similar to oneself in academic achievement) is actually a transitivity effect (e.g., choosing friends because they are the friends of existing friends who all happen to be similar). Thus by accounting for transitivity in the present study, some homophily effects may have faded away.

Limitations and Future Directions for Research on Cross-Race Friendships

Although the research reported here makes significant contributions to the interracial friendship literature, we acknowledge several limitations of our approach. First, the measure of racial homophily used in this study accounted for full (100% shared race), partial (50% shared race), or no homophily (0% shared race), but did not account for other variations of racial homophily (e.g., 25%, 75%) that could occur between individuals with more than two groups in their racial background. As the multiracial population continues to grow and diversify, incremental measures of racial homophily will need to be further refined to account for a broader range of racial similarity that could occur between individuals.

In addition, we accounted for the extent of racial homophily within specific dyads, but we did not differentiate between dyads on the basis of their particular racial configuration. For example, we did not investigate whether cross-race friendships were more likely for certain cross-race pairings compared to others or whether the influence of sharing a biracial friend was stronger for some cross-race pairings compared to others. In the interracial friendship literature, it is evident that Whites and Asians are most likely to befriend each other and that African Americans are the least preferred friendship choice among those willing to cross racial boundaries (Chen & Graham, 2015; Hamm et al., 2005; Doyle & Kao, 2007). Thus, the role of biracial youth in cross-race friendships may be more challenging but even more critical for cross-race peers who are least likely to be friends.

Similarly, our focus was on the role of biracial youth in aiding cross-race friendships among monoracial youth, not the friendship choices of biracial youth themselves. We did not take into account how stronger identification with one racial or ethnic group than another or equal identification with both groups might influence the friendship choices of biracial youth and thus their opportunities to play this role for particular pairings of groups. While there is some evidence to suggest that biracial youth may be more likely to identify with their minority (e.g., Black) than majority (e.g., White) status race (Doyle & Kao, 2007), racial identity and identification among biracial youth is a complex issue and appears to be influenced by the racial composition of their social networks (Echols, Ivanich, & Graham, 2018; Rockquemore & Brunsma, 2002). Other research with monoracial youth documents the influence of racial identity on cross-race friendships (Rivas-Drake, Umaña-Taylor, Schaefer & Medina, 2017). Studying cross-race friendships in conjunction with biracial identity processes would result in a more nuanced approach to the role of biracial youth.

We conducted our analyses in two middle schools that were ethnically diverse, in part to maximize the availability of different-race peers. The findings reported here therefore may not generalize to less diverse schools where there are fewer groups or large disparities in size between groups. In such contexts, the dynamics of cross-race friendships may be quite different. For example, when there are two relatively equally sized groups, there may be intergroup competition that reduces opportunities for positive contact between members of different racial or ethnic groups (Goldsmith, 2004). When there is one relatively large group, racial or ethnic groups in the numerical minority may “hunker down” and turn inward to find solidarity with same-race peers, resulting in fewer cross-race friendships than they have the opportunity to form (Putnam, 2007; Quillian & Campbell, 2003; Wilson & Rodkin, 2011). Under these circumstances it is not clear what role biracial youth would play in facilitating cross-race friendships. Multilevel modeling approaches, though still under development for use with social network analysis, may provide some analytic tools for including school-level variability in racial or ethnic composition.

There may be other school-level factors that affect the likelihood of choosing a cross-race peer as a friend that we did not consider here such as the overall racial climate and social norms supporting diversity. Previous research has shown that inclusive norms for cross-race friendships from in-group peers have a uniquely positive effect on one’s own interest in cross-race friendships (Tropp, O’Brien, & Migacheva, 2014). Thus, in-group norms could moderate the association between availability of different-race peers and cross-race friendships over and above the influence of biracial mutual friends. We suspect these norms would be more influential the larger the size of the group (see Bond, 2005).

Finally, with our focus on the role of biracial youth in the selection of cross-race friendships, we did not examine the influence of mutual biracial friends on the formation or maintenance of cross-race friendships over time. Likewise, we did not address the role of biracial youth on the quality of these cross-race ties. There is vigorous debate in the interracial friendship literature on these topics that we believe can be informed by giving more attention to the role of mutual biracial friends. For example, research is inconclusive on whether cross-race friends are of the same quality (e.g., supportive, validating, enduring) as same-race friendships (see review in Graham & Kogachi, in press). However, this research suggests that if cross-race friendships can survive the first few fragile months, they may last just as long as same-race friendships, especially if they are based on socially meaningful dimensions of homophily (McDonald et al., 2013). A question for future research is whether transitivity resulting from mutual friendships with biracial peers can help buffer the early challenges of friendships among their cross-race peers. We do not know of any research that has examined the influence of mutual biracial friends—or mutual friends in general—on the quality and stability of cross-race friendships. This may be a particularly important topic to pursue during the transition to middle school when many new friendships are forming.

The Role of Biracial Youth in Peer Relations

The rapid growth of biracial individuals has caused speculation in the literature about their impact on intergroup relations. Some scholars suggest that as the number of biracial youth continues to increase, racial categories will become less salient (i.e., racial distinctions could become blurred) and intergroup relations could therefore improve; other scholars speculate that because racial boundaries in the United States are so rigid, biracial youth could be rejected by their monoracial peers, be disconnected from others in their peer networks, and have little influence on intergroup relations (see Brown, 1990; Lee & Bean, 2004; Quillian & Redd, 2009). Much of the literature on biracial youth has focused more on the risks associated with the latter hypothesis (e.g., psychological maladjustment and identity confusion); and less on the actual presence and function of biracial youth in their peer networks (Rockquemore, Brunsma, & Delgado, 2009). Our results suggest that biracial youth are well integrated in their social networks, have many monoracial friends, and serve as social bridges for cross-race friendships.

A robust finding in the interracial friendship literature is that cross-race friendships are associated with better attitudes toward the racial groups to which cross-race friends belong (Davies, Tropp, Aron, Pettigrew, & Wright, 2011). Less documented in this literature, however, are studies on the processes, or underlying mechanisms, by which cross-race friendships exert their effects (Turner & Cameron, 2016). Studying biracial youth could provide insight into those mechanisms. For example, Paluck (2011) documented that influential high school peers (social referents) who were trained to confront prejudice at their school were most able to affect the prejudicial behaviors of their peers. Because biracial youth have positive intergroup attitudes and are well-positioned in their social networks with direct access to members of multiple monoracial groups, we propose that they could function as social referents, facilitating the flow of important information (e.g., knowledge, attitudes) between members of different groups.

At a more applied level, biracial youth could also play a role in prejudice reduction programs that, to date, have only indirectly harnessed the power of cross-race friendships (Graham & Kogachi, in press; Turner & Cameron, 2016). Evidence-based strategies to reduce prejudice include cooperative learning, fostering a common ingroup identity, and enhancing perspective taking (Beelman & Heinemann, 2014). All of these strategies are likely to work best when children are receptive to cross-race friendships. Hence there are many identified contexts in which biracial youth could play a critical role, mediating social contact and potentially reducing the anxiety that monoracial different-race peers often experience in intergroup settings (see Brown & Hewstone, 2005).

We would like to see much more research on biracial youth in the friendship literature, especially the unique role that they may play in promoting cross-race friendships and, by implication, improving intergroup attitudes. We hope the social network analysis presented here can provide a useful framework for such research. As a fast growing racial group reflecting the increasing diversity of U.S. society, biracial youth can provide new insights into racial dynamics in this country, including the fluidity versus rigidity of crossing racial boundaries.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and the National Science Foundation to the second author.

Contributor Information

Leslie Echols, Department of Psychology, Missouri State University.

Sandra Graham, Department of Education, University of California, Los Angeles.

References

- Aboud FE, Mendelson MJ, & Purdy KT (2003). Cross-race peer relations and friendship quality. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27, 165–173. doi: 10.1080/01650250244000164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beelmann A, & Heinemann KS (2014). Preventing prejudice and improving intergroup attitudes: A meta-analysis of child and adolescent training programs. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 35, 10–24. doi: 10.1016/j.appdev.2013.11.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bagci SC, Kumashiro M, Smith PK, Blumberg H, & Rutland A (2014). Cross-ethnic friendships: Are they really rare? Evidence from secondary schools around London. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 41, 125–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ijintrel.2014.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Block P (2015). Reciprocity, transitivity, and the mysterious three-cycle. Social Networks, 40, 163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2014.10.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bond R (2005). Group size and conformity: A meta-analysis. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 8, 331–351. doi: 10.1177/1368430205056464 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brechwald W, & Prinstein M (2011). Beyond homophily: A decade of advances in understanding peer influence processes. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 21, 166–179. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00721.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PM (1990). Biracial identity and social marginality. Child and Adolescent Social Work, 7, 319–337. doi: 10.1007/BF00757029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown R, & Hewstone M (2005). An integrative theory of intergroup contact. In Zanna M (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron L, Rutland A, Hossain R, & Hetley R (2011). When and why does extended contact work? The role of high quality direct contact and group norms in the development of positive ethnic intergroup attitudes amongst children. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 14, 193–206. doi: 10.1177/1368430210390535 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, & Graham S (2015). Cross-ethnic friendships and intergroup attitudes among Asian American adolescents. Child Development, 86, 749–764. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies K, Tropp LR, Aron A, Pettigrew TF, & Wright SC (2011). Cross-group friendships and intergroup attitudes a meta-analytic review. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 15, 332–351. doi: 10.1177/1088868311411103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Haye K, Robins G, Mohr P, & Wilson C (2010). Obesity-related behaviors in adolescent friendship networks. Social Networks, 32, 161–167. doi: 10.1111/jora.12045 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle J, & Kao G (2007). Friendship choices of multiracial adolescents: Racial homophily, blending, or amalgamation? Social Science Research, 36, 633–653. doi: 10.2307/2095662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echols L, & Graham S (2013). Birds of a different feather: How do cross-ethnic friends flock together? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 59, 461–488. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2013.0020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Echols L, & Graham S (2016). For Better or Worse: Friendship Choices and Peer Victimization among Ethnically Diverse Youth in the First Year of Middle School. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 1862–1876. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0516-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echols L, Ivanich J, & Graham S (2018). Multiracial in middle school: The influence of classmates and friends on changes in racial self-identification. Child Development. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Echols L, Solomon B, & Graham S (2014). Same spaces, different races: What can cafeteria seating patterns tell us about intergroup contact in middle school? Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20, 611–620. doi: 10.1037/a0036943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feddes A Noack P, & Rutland A (2009). Direct and extended friendship effects on minority and majority children’s interethnic attitudes: A Longitudinal study. Child Development, 80, 377–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01266.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feld SL (1981). The focused organization of social ties. American Journal of Sociology, 86, 1015–1035. doi: 10.1086/227352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith PA (2004). Schools’ role in shaping race relations: Evidence on friendliness and conflict. Social Problems, 51, 587–612. doi: 10.1525/sp.2004.51.4.587 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goodreau SM, Kitts JA, & Morris M (2009). Birds of a feather, or friend of a friend? Using exponential random graph models to investigate adolescent social networks. Demography, 46, 103–125. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, & Kogachi K (in press). Cross race/ethnic friendships in school. In Worrell F & Hughes T (Eds.), Cambridge handbook of applied school psychology. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Graham S, Munniksma A, & Juvonen J (2014). Psychosocial benefits of cross-ethnic friendships in urban middle schools. Child Development, 85, 469–483. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallinan MT (1974). A structural model of sentiment relations. American Journal of Sociology, 80, 364–378. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2777506 [Google Scholar]

- Hallinan MT (1979). Structural effects on children’s friendships and cliques. Social Psychology Quarterly, 42, 43–54. doi: 10.2307/3033872 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hallinan MT, & Williams RA (1989). Interracial friendship choices in secondary schools. American Sociological Review, 54, 67–78. doi: 10.2307/2095662 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm JV (2000). Do birds of a feather flock together? The variable bases for African American, Asian American, and European American adolescents’ selection of similar friends. Developmental Psychology, 36, 209–219. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.36.2.209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamm JV, Brown BB, & Heck DJ (2005). Bridging the ethnic divide: Student and school characteristics in African American, Asian-descent, Latino, and White adolescents’ cross-ethnic friend nominations. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 15, 21–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2005.00085.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanneman RA, & Riddle M (2005). Introduction to social network methods. Riverside, CA: University of California, Riverside. Retrieved from http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/ [Google Scholar]

- Humes KR, Jones NA, & Ramirez RR (2011). Overview of race and Hispanic origin: 2010. 2010 Census Briefs. U.S Department of Commerce. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Hunter DR, Handcock MS, Butts CT, Goodreau SM, & Morris M (2008). ergm: A package to fit, simulate, and diagnose exponential-family models for networks. Journal of Statistical Software, 24, 1–29. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2743438/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J Le VN, Kaganoff T, Augustine C, & Constant L (2004). Focus on the wonder years: Challenges facing the American middle school. Santa Monica, CA: Rand. [Google Scholar]

- Juvonen J, Kogachi K, & Graham S (2018). When and how do students benefit from ethnic diversity in middle school? Child Development, 89, 1269–1282. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang SK, & Bodenhausen GV (2015). Multiple identities in social perception and interaction: Challenges and opportunities. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 547–574. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao G, & Joyner K (2004). Do race and ethnicity matter among friends? Activities among interracial, interethnic, intraethnic adolescent friends. The Sociological Quarterly, 45, 557–573. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2004.tb02303.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y, & Crick NR (2008). The role of cross-racial/ethnic friendships in social adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 44, 1177–1183. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.4.1177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawabata Y, & Crick NR (2011). The significance of cross-racial/ethnic friendships: Associations with peer victimization, peer support, sociometric status, and classroom diversity. Developmental Psychology, 47, 1763–1775. doi: 10.1037/a0025399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knifsend CA, & Juvonen J (2017). Extracurricular activities in multiethnic middle schools: Ideal context for positive intergroup attitudes? Journal of Research on Adolescence, 27, 407–422. doi: 10.1111/jora.12278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossinets G, & Watts DJ (2009). Origins of homophily in an evolving social network. American Journal of Sociology, 115, 405–450. doi: 10.1086/599247 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lease AM, & Blake JJ (2005). A comparison of majority-race children with and without a minority-race friend. Social Development, 14, 20–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2005.00289.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, & Bean FD (2004). America’s changing color lines: Immigration, race/ethnicity, and multiracial identification. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 221–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110519 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Louch H (2000). Personal network integration: Transitivity and homophily in strong-tie relations. Social Networks, 22, 45–64. doi: 10.1016/S0378-8733(00)00015-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marsden PV (1988). Homogeneity in confiding relations. Social Networks, 10, 57–76. doi: 10.1016/0378-8733(88)90010-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald KL, Dashielle-Aje E, Menzer MM, Rubin KH, Oh W, Bowker JC (2013). Contributions of racial and sociobehavioral homophily to friendship stability and quality among same-race and cross-race friends. Journal of Early Adolescence, 33, 897–919. doi: 10.1037/t07310-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McPherson M, Smith-Lovin L, & Cook JM (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moody J (2001). Race, school integration, and friendship segregation in America. American Journal of Sociology, 107, 679–716. doi: 10.1086/338954 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mouw T, & Entwisle B (2006). Residential segregation and interracial friendship in schools. American Journal of Sociology, 112, 394–441. doi: 10.1086/506415 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munniksma A, & Juvonen J (2012). Cross-ethnic friendships and sense of social-emotional safety in a multiethnic middle school: An exploratory study. Merill-Palmer Quarterly, 58, 489–506. doi: 10.1353/mpq.2012.0023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munniksma A, Scheepers P, Stark TH, & Tolsma J (2017). The impact of adolescents’ classroom and neighborhood ethnic diversity on same- and cross-ethnic friendships within classrooms. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 27, 20–33. doi: 10.1111/jora.12248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Education Statistics, U. S. Department of Education (2017, May). Racial/Ethnic Enrollment in Public Schools. Retrieved from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cge.asp

- Oakes J (2005). Keeping track: How schools structure inequality, second edition. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paluck EL (2011). Peer pressure against prejudice: A high school field experiment examining social network change. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 350–358. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2010.11.017 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew TF (1997). Generalised intergroup contact effects on prejudice. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 173–185. doi: 10.1177/0146167297232006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center (2015, June 11). Multiracial in America: Proud, diverse, and growing in numbers. Retrieved from http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2015/06/11/multiracial-in-america/

- Putnam RD (2007). E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century, The 2006 Johann Skytte prize lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies, 30, 137–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9477.2007.00176.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quillian L, & Campbell ME (2003). Beyond black and white: The present and future of multiracial friendship segregation. American Sociological Review, 68, 540–566. doi: 10.2307/1519738 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quillian L, & Redd R (2009). The friendship networks of multiracial adolescents. Social Science Research, 38, 279–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 3.3.3) [Computer software]. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Available from http://www.R-project.org [Google Scholar]

- Rivas-Drake D, Umaña-Taylor A, Schaefer D, & Medina M (2017). Ethnic-racial identity and friendships in early adolescence. Child Development, 88, 710–724. doi: 10.1111/cdev.127790 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockquemore KA, & Brunsma DL (2002). Socially embedded identities: Theories, typologies, and processes of racial identity among Black/White biracials. The Sociological Quarterly, 43, 335–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1533-8525.2002.tb00052.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rockquemore KA, Brunsma DL, & Delgado DJ (2009). Racing to theory or retheorizing race? Understanding the struggle to build a multiracial identity theory. Journal of Social Issues, 65, 13–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.2008.01585.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shrum W, Cheek NH, & Hunter SM (1988). Friendship in school: Gender and racial homophily. Sociology of Education, 61, 227–239. doi: 10.2307/2112441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Spiro ES, Acton RM, & Butts CT (2013). Extended structures of mediation: Re-examining brokerage in dynamic networks. Social Networks, 35, 130–143. doi: 10.1016/j.socnet.2013.02.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tropp LR, O’Brien TC, & Migacheva K (2014). How peer norms of inclusion and exclusion predict children’s interest in cross-ethnic friendships. Journal of Social Issues, 70, 151–166. doi: 10.1111/josi.12052 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner R, & Cameron L (2016). Confidence in contact: A new perspective on promoting cross-group friendship among children and adolescents. Social Issues and Policy Review, 10, 212–246. doi: 10.1111/sipr.12023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Turner R, & Feddes AR (2011). How intergroup friendship works: A longitudinal study of friendship effects on outgroup attitudes. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 914–923. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña‐Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Rivas‐Drake D, Schwartz SJ, …Seaton E (2014). Ethnic and racial identity during adolescence and into young adulthood: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85, 21–39. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner C, & Parmelee P (1979). Similarity of activity preference among friends: Those who play together stay together. Social Psychology Quarterly, 42, 62–66. doi: 10.2307/3033874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson T, & Rodkin P (2011). African American and European American children in diverse elementary classrooms: Social integration, social status, and social behavior. Child Development, 82, 1454–1469. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01634.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimmer A, & Lewis K (2010). Beyond and below racial homophily: ERG models of a friendship network documented on Facebook. American Journal of Sociology, 116, 583–642. doi: 10.1086/653658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]