Abstract

Self-administration of Ethanol (E) and nicotine (N) occurs frequently in tandem orders (i.e., N→E vs. E→N) and thereby produce differing interoceptive profiles of subjective effects in humans. If the interoceptive stimulus characteristics of N→E differ from E→N, it is possible that such differences contribute to their co-dependence. The rationale for the present investigation was to determine if E when preceded or followed by N produces different discriminative stimulus effects in rats. In two experiments, using a one manipulanda operant drug discrimination procedure, rats were trained to discriminate temporal sequential administrations of ethanol (1.0 g/kg) that was followed or preceded by nicotine (0.3 mg/kg). Sessions alternated between food-reinforcement sessions on a variable interval 30 s schedule (i.e., SD) and non-reinforcement sessions (i.e., SΔ). In Exp 1, administrations of E were followed or preceded by a 10 min interval of N. Training sessions took place 10 min following the second drug injection. Four groups of rats were trained to discriminate only one sequence from sequential administrations of saline, and each drug sequence was counterbalanced across groups for their roles as SD or SΔ. There was robust stimulus control. N→E and E→N functioned equally well as SD or SΔ. Exp 2 used two groups of rats. For one group, the E→N sequence functioned as the SD and the N→E sequence functioned as the SΔ. The drug sequences were counterbalanced for the other group. Brief non-reinforcement tests revealed significantly greater responding during the SD sequence compared to the SΔ sequence for both groups. These results suggest that different drug sequences of ethanol followed, or preceded, by nicotine established reliable discriminative stimulus control over operant responding potentially because of characteristic differences in the overlapping pharmacokinetic profiles of the NE compound. The results are discussed in terms of: 1) conditional stimulus control among two interoceptive drug states; and 2) the clinical modulation of human alcohol consumption and tobacco smoking.

Keywords: conditional drug discrimination, drug sequence, ethanol, nicotine, rats

Introduction

Alcohol and tobacco abuse continues to pose a global economic burden. Previous estimates suggest that 60–90% of alcoholics are also heavy smokers (e.g., Kandel, Chen, Warner, Kessler, & Grant, 1997; Pennington, Durazzo, Schmidt, Mon, Abe, & Meyerhoff, 2013). Because alcohol and/or nicotine are self-administered individually and in tandem in humans, different profiles of subjective effects co-occur that also maintain the likelihood of self-administration of both drugs (Troisi, Dooley, & Craig, 2013). The operant drug discrimination paradigm has been an invaluable behavioral pharmacological assay for evaluating receptor mechanisms of action that are hypothesized to mediate specific sensory (i.e., “subjective”) effects for a number of drugs of abuse. Rodents can be trained quickly to respond differentially under the influence of two or more contrasting interoceptive drug states that set the occasion for specific operant response → food-reinforcement or non-reinforcement contingencies that are conditionally in effect.

Individually, the discriminative stimulus functions of nicotine and ethanol have been well documented (e.g., Barry & Krimmer, 1976; Barry, Koepfer, & Lutch, 1965; Gauvin, Youngblood, Goulden, Birscoe, & Holloway, 1994; Schechter & Meehan, 1992; Schechter & Rosecrans, 1972; Stolerman, Garcha, Pratt, & Kumar, 1984; Rosecrans and Villanueva, 1991; Troisi 2003a,b; Troisi, 2006, 2011). However, far less is known about the discriminative stimulus functions of these two drugs in compound (see Troisi et al., 2013 for review; c.f., Ford, Davis, McCracken, and Grant, 2013; Ford, McCracken, Davis, Ryabinin, and Grant, 2012, for reports using mice; and see Randall, Carranan, & Beesher, 2016 for a Pavlovian evaluation).

Previously, this laboratory (Troisi et al., 2013) trained rats to respond differentially among a mixture of ethanol plus nicotine (NE) vs. saline (Exp 1) or NE vs. N vs. E (Exp 2) using the same doses that were previously reported to be equal in salience (Gauvin & Holloway,1993) (i.e., 0.3 mg/kg of nicotine and 1.0 g/kg of EtOH). In one condition, the NE compound (SD) occasioned sessions of food-reinforced nose-poke responses that were maintained on a variable interval 30 s schedule (VI-30”); there were intermixed saline (S) sessions during which nose poking was non-reinforced (i.e., the SΔ). For other rats assigned to the opposite/counterbalanced condition, the NE compound functioned as the SΔ, whereas the non-drug S functioned as the SD. Robust discriminative stimulus control was evident for both groups across separate sets of brief non-reinforcement test sessions carried out separately under the NE and S conditions. N and E individually promoted responding that differed from saline but not the full NE compound. In Exp 2, N and E were individually discriminated from the full NE compound. Thus, the interoceptive stimulus properties of the NE compound qualitatively differs from its elementary N and E parts.

Because individuals self-administer ethanol and nicotine in tandem, the next question to address is whether differing temporal sequences of ethanol when followed or preceded by nicotine have perceptual differences? Ethanol, when followed by nicotine (i.e., E→N), might be expected to produce an interoceptive effect that differs qualitatively from when it is preceded by nicotine (i.e., N→E) because of the different overlapping pharmacokinetic profiles of each drug within each sequence. For instance, ethanol promotes phasic effects over time at different doses, with excitation and sedation at 6 and 30 min post dosing intervals, respectively (Shippenberg & Altshuler, 1985). If one assumes that the combined effects of the two drugs over time produce different types of NE vs. EN compounds as a function of which drug in the sequence occurred first and second, then it seems plausible that each sequence should promote discernable stimulus properties with characteristically different interoceptive effects. Such findings could have important implications for addressing the temporal nexus between alcohol and tobacco co-abuse and its progression. In view of this, the current studies, sought to determine whether two drug→drug sequences, which differed only by the temporal order of ethanol preceding (or following) nicotine, could acquire discriminative stimulus control over operant responding (i.e., E→N vs. N→E) in promoting SD and/or SΔ stimulus effects. This question was investigated using a one manipulanda (nose-poke) appetitive operant drug discrimination procedure with intermixed alternations between food reinforcement (SD) and non-reinforcement (SΔ) sessions (e.g., Troisi, 2003a,b; Troisi 2006, 2011; Troisi, Bryant, & Kane, 2012). In this arrangement, each drug element predicts the reinforcement and non-reinforcement outcomes, but the predictability of each drug element for the outcome-reinforcer, or its absence, is conditional on the order in which it occurs within the sequential compound. With the one-manipulanda procedure, the drugs can be more effectively evaluated for their facilitative SD and suppressive SΔ roles (Troisi, 2013b), by comparison with the more commonly used two-lever choice procedure in which reinforcement is in effect during each session conditional on responses emitted on the correct lever under drug vs. saline (Troisi, 2013). It must be noted here, that the SΔ inhibitory effects of drugs have been evaluated elsewhere; it was demonstrated that the SΔ drug conditions suppressed reinstated responding shown under the SD condition (Troisi, 2003b) and promoted transfer of response suppression to a separately established operant response that shared a common food-reinforcer (Troisi, LeMay, & Jarbe, 2010).

With four groups of rats, Exp 1 evaluated the extent to which each sequence alone could be discriminated from saline as an SD or an SΔ. Exp 2 contrasted each sequence with the other, within two counterbalanced groups. Stimulus control was determined by differences in rates of responding under SD vs. SΔ conditions. It was predicted that stimulus control would be robust in Exp 1 and evident, but less robust, in Exp 2.

Experiment 1

The aim of the first experiment was to determine the extent to which the N→E and E→N sequences could be discriminated individually from non-drug. To that end, four groups of rats were assigned to a different sequence that functioned as an SD and occasioned reinforcement sessions or as an SΔ and occasioned non-reinforcement sessions. Each drug sequence was contrasted with an S→S sequence as counterbalance for the opposing contingency (i.e., non-reinforcement or reinforcement). Hence, the four groups were as follows: 1) N→E+ vs. S→S-; 2) N→E- vs. S→S+; 3) E→N+ vs. S→S-, and 4) E→N- vs. S→S+, where positive and negative signs indicate SD and SΔ, respectively. It was predicted that the SD sequences would promote higher response rates than the SΔ sequences regardless of assignment to N→E, E→N, or S→S conditions, thus showing that each sequence functions equally well as SD and SΔ.

Method

Animals

Sixteen experimentally naïve male Sprague Dawley rats from Harlan Breeders (Indianapolis, IN) were maintained at 80% of their free-feeding weights (300–325 gm) at the start of the study and were three months old. Upon arrival the rats were handled, weights were recorded daily and adjusted for growth (approximately 15 g per week). The rats were housed individually in stainless steel hanging cages with acrylic floors that held wood shaving bedding. Ad libitum water was accessible throughout the duration of the study in the home cages. The light-dark cycle was 7:00 am – 7:00 pm (light phase). Experimental sessions took place during the light phase between 10:00 am and 2:00 pm. The study was conducted in accord with and approval by this institution’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee policies, OLAW, and the NIH Guide for use of laboratory animals.

Apparatus

Sessions took place in eight operant chambers (Med-Associates ENV-01; L 28 × W 21 × H 21 cm), equipped with a food magazine which delivered 45 mg food pellets (BioServe®, Frenchtown, NJ), centrally located on the front panel of the chamber measuring (H 5 × W 5 × D 3 cm) and one nose-poke device (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT model ENV 114 BM) that was located on the acrylic wall, left of the food magazine, in the rear of the chamber. The chambers were placed 2–3 feet apart and located about the perimeter of the sound and light attenuated experimental room designed for undergraduate Psychology courses related to behavioral biology. The room measures (L 16.5 × W 9 feet). A 15-watt light illuminated the room during session-time and was terminated at the end of each session by overhead room-lighting. A white noise source was delivered by an antenna-less and cable-free television, which was turned on at the start of each session and co-terminated with illumination by the overhead lighting, which was also turned on and off manually. Experimental events were programmed with Med-PC Software (Version 2.08) via a DIG interface (Med-Associates, St. Albans, VT) to a PC in an adjacent monitoring room.

Procedure

General procedures and initial acquisition:

Sessions were run Monday through Friday between 10:00 AM and 02:00 PM. Magazine training took place on the first day and consisted of non-contingent food delivery scheduled on a variable time (VT) 1-min schedule. During this one hour session, the nose-poke devices were covered by stainless steel plates. At the end of the session, the food magazines were inspected for remaining food pellets to validate that adequate magazine training had occurred. Rats that did not consume all of the pellets were given additional magazine training on the following day. On the second day, the nose-poke devices were uncovered and 3 pellets were placed in each nose-poke device before the start of the session. Nose-poking was established rapidly and was initially maintained on a fixed ratio of one (FR-1) for the duration of the 30 min session. Over the next eight days, nose-poking was maintained on a variable interval 30 sec (VI-30”) schedule of food-reinforcement. Sessions were 15 min but were later switched to 20 min for the drug discrimination training.

Drugs & Drug Administration.

Ethanol (95% stock) was measured 13.2 ml per 100 ml’s of 10% solution of 10-X phosphate buffered saline (saline), which maintained a constant pH of 7.0 and was delivered in a volume of 10 ml/kg delivering a dose of 1.0 g/10 ml. via 10 ml syringe. The dosage of EtOH was 1.0 g/kg. Nicotine (−)-nicotine hydrogen tartrate (Sigma) (0.3 mg/kg; calculated as base) was dissolved in the saline vehicle and administered in an equivalent volume as EtOH. Approximately twenty minutes prior to each 20-min discrimination training session, or 5-min non-reinforcement test session, rats received intraperitoneal injections of either nicotine, ethanol, or saline. The second administration followed approximately 10 min later, but was the opposite drug state or saline. These doses were selected because they have shown to be equal in salience and have produced reliable discriminative stimulus effects in this lab (e.g.,Troisi et al., 2013) and others (Gauvin & Holloway, 1993). On S→S sessions, 10 ml/kg of saline were administered twice with the same timing intervals as described for the N→E and E→N sequences. Approximately ten minutes following the second drug (or second saline) administration, the rats were transported together as a group of 8 in a white Nalgene® box from the vivarium down the hall to the conditioning lab. Each rat was placed into the randomly-assigned operant chamber, which did not change throughout the course of the study. The nose-poke manipulanda and the food magazines were pre-wiped with a 10% EtOH solution daily and in between squads to eliminate odor cues that can potentially direct behavior (see Extance & Goudie, 1981).

Drug discrimination training.

Drug discrimination training took place over the course of the next 30 sessions, 15 with one sequence assigned to each of the four groups, and 15 with S→S sequences. For one group (n=4) the N→E+ sequence functioned as SD and S→S- functioned as SΔ; the roles of the conditions were the opposite for a second group (n=4) with the N→E- sequence functioning as SΔ and the S→S+ functioning as the SD. For the third group (n=4), the E→N+ sequence functioned as SD and S→S- functioned as the SΔ. Finally, the roles of the conditions were the opposite for the fourth group (n=4) with the E→N- sequence functioning as the SΔ and S→S+ as the SD. Thus, each counterbalanced sequence functioned across the four groups as SD or SΔ. Drug sequence sessions and saline sessions were intermixed with no more than two consecutive sessions of one condition.

Non-reinforcement test sessions.

Next, there were two 5-min non-reinforcement test days with two regular 20-min intervening training sessions conducted under each condition in between the two test days. Eight rats received administrations of one drug sequence (4 with N→E and 4 with E→N) on the first test day and the S→S sequence on the second day (with the roles the drug sequences and saline sequences counterbalanced across days). The other eight rats received the saline sequences on the first test day and the drug sequences on the second test day. The roles of the drug and saline sequences were fully counterbalanced across rats, days, and SD/ SΔ stimulus roles.

Results

Training sessions

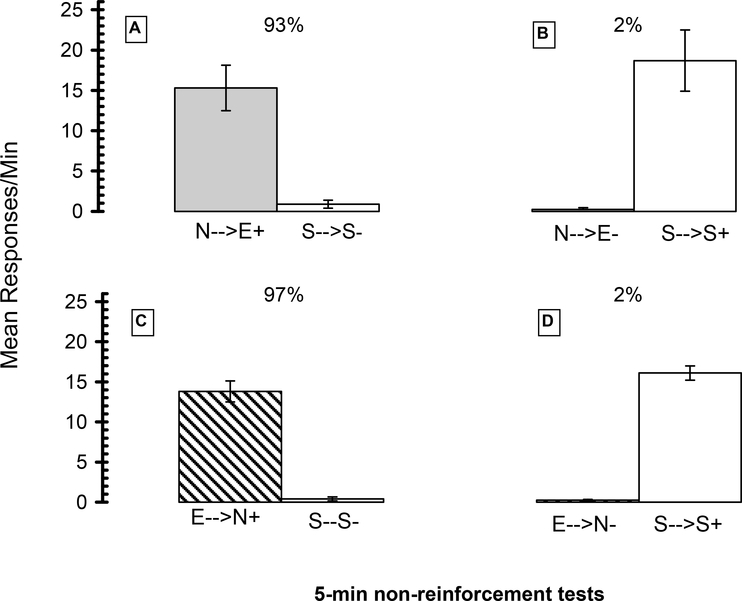

Fig 1 (A through D) displays the results of the 30 20-min discrimination training sessions. As evident, SD rates for all four groups were higher than the SΔ conditions. For each group, a paired samples t-test compared response rates obtained in the SD sequence condition to those in the SΔ sequence conditions. Because a-priori predictions were that SD response rates would be higher than SΔ response rates, one-tailed probability values were justified. Additionally, the paired sampled t-tests (α=.05) were used as planned a-priori comparisons, rather than merely as multiple post-hoc tests. The results for each group were averaged across the last 3 sessions for the SD and SΔ conditions and are summarized in Table 1. For the two groups assigned to the two drug sequences that functioned as the SD (A and C) there was significantly greater responding under the drug sequences compared to the saline SΔ sequences [ts(3) ≥ 5.03; ps≤ .008]. By contrast, the rates of responding under the SΔ drug sequences (B and D) were significantly lower than under the saline SD sequences for the counterbalanced groups [ts(3) ≥ 8.07; ps ≤ .002].

Figure 1.

Exp 1 acquisition training results for 16 rats trained to discriminate sequences of nicotine (N)→EtOH (E) from a saline (S)→saline (S) or sequences of EtOH→nicotine from a saline→saline sequence. For four rats (A) the N→E+ functioned as the SD and occasioned 20-min sessions in which nose poking was food-reinforced on a VI-30” schedule; S→S- functioned as SΔ and occasioned non-reinforcement sessions. The stimulus roles were reversed for the four rats assigned to the opposite condition (B). Four other rats (C) were assigned to the E→N SD and S→S- SΔ condition, and those roles were counterbalanced for the remaining four rats (D).

Table 1.

Summary of last three training sessions

| A | B | ||

| C | D | ||

Mean lever press rates (+/− SEM) averaged over the final 3 training sessions for 4 squads of rats (A - D) (n=4/squad) trained to discriminate one drug sequence consisting of ethanol (E) followed or preceded by nicotine (N) from a saline sequence (S S) in Exp 1. Plus and minus signs indicate the SD and SΔ sequences conditions, respectively.

Test Sessions

Fig 2 (A through D) displays the results of the two 5-min non-reinforcement tests that were conducted under each of the two sequences. For the N→E+/S→S- trained group (A), responding under the N→E+ SD compound sequence was significantly greater than under S→S- SΔ sequence [t(3)=4.54; p = .011]. By contrast, for the N→E-/S→S+ trained group (B), there was significantly less responding under the N→E- SΔ sequence compared to the S→S+ SD sequence [t(3)=4.76; p = .009). N→E functioned effectively as SD and SΔ. Similarly, for the E→N+/S→S- trained group (section C), responding under E→N+ SD compound sequence was significantly greater than responding under S→S- SΔ [t(3)=10.44; p=.001]. By contrast, for the E→N-/S→S+ trained group (section D), responding under the E→N- SΔ sequence was significantly lower than under the S→S+ SD sequence [t(3)=17.77; p≤ .001]. E→N functioned effectively as an SD and SΔ. Discrimination indices [total SD responses/(total SD responses + total SΔ responses) * 100] were calculated and are shown as percentages. As shown, indices for the SD drug sequences were > 90% (A and C), whereas those for the SΔ drug sequences were < 5% (B and D).

Figure 2.

5-min test results for the rats in Exp 1. For four rats (A) the N→E+ functioned as the SD and S→S- functioned as SΔ. The stimulus roles were reversed for four counterbalanced rats (B). Four rats were assigned to the E→N+ SD and S→S- SΔ (C) with four other rats counterbalancing the stimulus roles (D). Discrimination indices (% drug sequence responding) are noted above the drug sequence bars.

Discussion

Experiment 1 sought to determine if administration of a sequence of alcohol followed or preceded by nicotine could establish discriminative control over operant responding. Alternation between the SD and SΔ drug sequences across the training sessions established reliable discriminative control over responding. Within groups, responding under the SD sequences was greater than under the SΔ sequences, and the rates of responding under the SD drug sequences were comparable between the two groups. More crucially, the non-reinforcement tests conducted with the drug sequences provided further validity for evidence of stimulus control by the drug→drug sequences. Therefore, relative to the S→S control conditions, the N→E and E→N sequence compounds functioned effectively as SDs and SΔs, thus, controlling for unconditioned effects on responding.

EXPERIMENT 2

As demonstrated in the first experiment, the N→E and E→N sequences each functioned effectively as either SDs or SΔs when contrasted with saline. Experiment 2 sought to explicate the extent to which, if at all, E→N could be discriminated from N→E, within subjects. Such a contrast among the two sequences was hypothesized to be more difficult in coming under differential stimulus control because of the relative overlapping pharmacodynamics of the two compounds, which might promote stimulus generalization. As in Exp 1, the roles of the two sequences were counterbalanced - but across just two larger groups of rats. For the first group, the N→E sequence functioned as the SD condition, whereas the E→N sequence functioned as the SΔ. For the other group, the roles of the drug sequences set the occasion for the opposite contingencies. As in the first experiment, it was predicted that the SD sequences would evoke greater response rates than the SΔ sequence during training but more critically during the two non-reinforcement tests.

Method

Animals

16 experimentally naïve male Sprague Dawley rats were obtained from Harlan Breeders (Indianapolis, IN). The rats were from the same batch described in Exp 1 and were maintained in exactly the same manner. Weights were equivalent.

Apparatus

Sessions took place in exactly the same eight operant chambers as described in Experiment 1.

Procedure

General procedures and initial acquisition:

The initial training was identical to Exp 1.

Drugs & Drug Administration:

The drugs, doses, means of administration, and inter-dose- intervals were identical to Exp 1, with the exception that saline was not administered, only the two opposing sequences of ethanol and nicotine with the same timing intervals.

Drug discrimination training.

Acquisition sessions took place as described in Experiment 1; the sessions were 20-min in duration, and the reinforcement schedule was a VI-30 sec for the SD sessions. There were 30 training sessions in which SD and SΔ stimulus conditions alternated with no more than two consecutive sessions of any one condition. Eight rats were assigned to the N→E+ SD/E→N- SΔ sequences and 8 rats were assigned to the E→N+ SD/ N→E- SΔ sequences.

Test conditions:

The two test sessions were 5-min in duration and again were conducted without food delivery. Testing took place as described in Experiment 1 with the original SD and SΔ sequences counterbalanced by order and stimulus role over the two test days. On the first test day, 8 rats were administered the N→E sequence (4 rats SD and 4 rats SΔ) and the other 8 were administered the E→N sequence (4 rats SD and 4 rats SΔ). Two 20-min training sessions followed over the next two days, one under each drug sequence. On the second day of testing, the opposite counterbalanced drug sequences were administered to both groups.

Results

Training sessions

The 30-day training session results for the two groups assigned to the two counterbalanced drug sequences are displayed in Fig 3. Inspection of Fig 3 reveals that response rates under the SD sequences for both groups were significantly greater than under the SΔ sequences. Data were averaged across the final three training sessions for SD and SΔ for each group. For the N→E+/E→N- group, the mean rate of responding in the N E+ SD condition (24.78/min; sem=2.29) was significantly higher than the mean rate in the E N- SΔ condition (3.18/min; sem=.44) [t(7)=9.10; p≤ .001]. Similarly, for the E→N+/N→E- group, the mean rate of responding in the E→N+ SD condition (19.86/min; sem=.97) was significantly greater than the mean rate of responding un the N→E- SΔ condition (2.79/min; sem=.31) [t(7)=19.99; p≤ .001].

Figure 3.

Exp 2 acquisition training results for 16 rats trained to discriminate a sequences of nicotine (N)→EtOH (E) from a EtOH→nicotine. For eight rats, the N→E+ sequence functioned as SD signaling 20-min food reinforced sessions and the E→N sequence functioned as the SΔ (top graph). Eight other rats were assigned to the opposite contingencies in which the E→N+ sequence functioned as the SD and the N→E- sequence functioned as the SΔ (bottom graph).

Tests results

The 5-min non-reinforcement results are displayed in Fig 4. Specific one-tailed paired-samples t-tests (α=.05) were made comparing the post-acquisition training results. For the N→E+ SD/E→N- SΔ trained group (left two bars), response rates evoked by the N→E+ SD condition were significantly higher than those evoked by the E→N- SΔ condition [t(7)=1.98; p = .044). For the E→N+ SD/N→E- SΔ trained group (right two bars), the rate of responding evoked by the E→N+ SD compound sequence was significantly greater than that evoked by the N→E- SΔ compound sequence [t(7)=2.55; p=.019). Discrimination indices were modest at 61–62% for the N→E SD and E→N SD conditions, respectively.

Figure 4.

5-min non-reinforcement test results for Exp 2. For eight rats, the N→E+ sequence functioned as SD signaling 20-min food reinforced sessions and the E→N sequence functioned as the SΔ (left bars). Eight other rats were assigned to the opposite contingencies in which the E→N+ sequence functioned as the SD and the N→E- sequence functioned as the SΔ (right bars). Discrimination indices (% SD responses) are displayed above each set of bars.

Discussion

Experiment 2 demonstrated that the E→N and N→E sequences were discriminable from each other. However, the discrimination indices (%SD responses) only averaged 61–62% compared to 93–97% evident in Exp 1. Thus, as predicted, stimulus control was evident but less robust compared to when each sequence was pitted against saline as demonstrated in Exp 1. This is not surprising because there appeared to be a reasonable amount of stimulus generalization across the two sequences. Evidence to support this view was shown by lower SD responding and higher SΔ responding compared to that which was evident in Exp 1. Rates of responding were significantly different in both groups, but discrimination indices were modest in Exp 2. Ordinarily, in a two-lever discrimination procedure, discrimination indices > 50% drug-appropriate-lever responding is considered to be a partial substitution. That SD responding was approximately 62% (or, conversely, 38% SΔ responding under the opposite drug sequence) in the present one-manipulandum procedure further suggests partial generalization across the two sequences, but retention of characteristic discriminability as evidenced by significant differences in response rates across the two groups. The SΔ drug sequences failed to completely suppress (i.e., inhibit), but did not maintain, operant responding promoted by the SD drug sequences.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

In humans, nicotine self-administration (via tobacco smoking) and ethanol consumption occurs in tandem and in varying orders. With rats, the present studies evaluated the discriminative stimulus functions of two different drug sequences: nicotine→ethanol and ethanol→nicotine. Both experiments showed that these sequences attained SD and SΔ functions in setting the occasion for the presence or absence of a biologically relevant outcome (i.e., appetitive reward). When the two sequences were contrasted with the saline sequences (Exp 1), there was more robust stimulus control relative to when each sequence was contrasted with the other, which likely rendered stimulus generalization across the two sequences; hence, the elevation of SΔ responding and diminished SD responding (Exp 2).

It is unclear from the present data what the pharmacological impact of each drug element was on the subsequent drug element within the drug sequence. There is mixed evidence showing modulatory effects of each drug on the discriminative role of the other (Signs & Schechter, 1986; Kim & Brioni, 1995; c.f., Le Foll and Goldberg, 2005). There is also evidence for cross-tolerance for some behavioral effects between nicotine and ethanol (Collins, Burch, DeFiebre, and Marks, 1988), although tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects was not evaluated in that study. Tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine is not readily attained (Shoaib et al. 1997). By comparison, tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of alcohol have been reported by chronic exposure to EtOH (~10 g/day) in rats maintained in the home cage (Emmett-Oglesby, 1990); but it has not been reported to occur due to the normal course of drug discrimination training. In one evaluation, Becker & Baros (2006) initially established stimulus control with EtOH in mice, and later found that chronic ethanol inhalation shifted the dose-response curve to the right, which demonstrated tolerance. Interestingly, nicotine has been shown to potentiate the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol with a two-lever choice drug discrimination procedure (Bienkowski and Kostowski, 1998; Signs and Schechter, 1986). However, in these studies, nicotine was given following acquisition of the already established ethanol discrimination, rather than as a compound mixture during the course of discrimination training – as carried out in the present study. The extent to which nicotine potentiated discriminative effects of ethanol in the present study is unknown. On balance, nicotine has been shown to enhance the conditioned reinforcing effects of cues that predict primary reward (Olausson, Jentsch, & Taylor, 2003, 2004), and suppress responding to cues not-associated with reward, or those that have been extinguished (Troisi, 2011). Thus, nicotine may well have modulated ethanol as an SD and as an SΔ.

The effects of ethanol on the discriminative stimulus functions of nicotine are also noteworthy. Kim and Brioni (1995), and later, Korkosz, Taracha, Plaznik, Wrobel, Kostowski, & Bienkowski (2005), reported that ethanol attenuated the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine (c.f., Le Fol & Goldberg, 2005). However, again, in those studies, the nicotine discrimination was established first and then challenged with EtOH, whereas, in the present investigation, nicotine was always preceded by EtOH during discrimination training. The extent to which EtOH may have attenuated the discriminative effects of nicotine over the course of training are unknown. Nevertheless, Exp 1 demonstrated that the N→E and E→N sequences were equivalently different from saline in terms of their discriminative functions at the doses used here. Of course, the current study did not vary dose to more precisely address this issue. It would be informative to antagonize the nicotine cue with mecamylamine at the time of ethanol presentation (see Stolerman et al, 1999, 2003). It might be equally informative to partially antagonize the EtOH cue with Ro15–4513 (e.g., Gatto & Grant, 1997; Linden, Schmitt, Leppä, Wulff, Wisden, Lüddens, Korpi, 2011) at the time that nicotine is presented. Such methodological approaches might reveal the relative discriminative contribution of each element to the drug sequence. Of course, the mechanisms of the discriminative functions of EtOH are diverse and varied (Grant, 1999; Hodge, Grant, Becker, Besheer, Crissman, Platt, & … Shelton, 2006).

Previously, this lab demonstrated that the combined effects of 1.0 g/kg of EtOH plus 0.3 mg of nicotine (EN) is perceived as a unique cue that is discriminable from the elementary E and N parts (Troisi et al. 2013). In the present experiments, 0.3 mg/kg nicotine was followed by the 1.0 g/kg dose of EtOH. At the time of administration of EtOH (10 minutes later), nicotine was well within its peak temporal parameter for a sufficient discriminative stimulus control (Stolerman & Garcha, 1989). Thus, while EtOH was being absorbed and distributed, nicotine was perhaps at its peak discriminable plasma level. Similarly, on occasions when EtOH preceded nicotine, EtOH was also within the temporal parameter for a sufficient discrimination. For instance, EtOH has been shown to maintain discriminative control 30 minutes following injection (Schechter, 1981), and as noted earlier, the combination of the drugs at the time of the training session (i.e., 20 mins. from the first injection in the sequence) perhaps was a qualitatively different cue (“mixture-like”) compared to when EtOH was followed 10 min. later by nicotine. Thus, the nature of the “mixture-like” compound when EtOH preceded nicotine compared to when nicotine preceded EtOH may have qualitatively differed as a function not only by the nature of pharmacokinetics but also by the precedence of first drug cue. That is, the first drug cue (e.g., nicotine) predicted perhaps one type of “mixture-like” effect, which occasioned a specific operant outcome - food reinforcement. For the same rats, EtOH predicted perhaps a qualitatively different type of “mixture-like” effect which occasioned a different operant outcome – non-reinforcement. In this scenario, both drugs in their respective orders produced different discriminative effects. Thus, it seems that the relative discriminative differences between the sequences were asymmetrical because of their relationships with food reward. There appeared to be both facilitative and inhibitory cross generalizations from N→E to E→N (Fig 4) thus promoting only 61–62% SD responding across doses and experiments. Therefore, it is plausible that the first drug in the sequence occasioned a nicotine-ethanol (NE) or ethanol-nicotine (EN) compound cue, which qualitatively differed as a function of the overlapping pharmacokinetic profiles that emerged over the 20-min interval. IP administration of the nicotine element when followed 10 min later by the ethanol element promoted the emergence of the NE gestalt compound; whereas, ethanol followed by nicotine promoted the emergence of a different gestalt compound EN. The resulting temporal cues, therefore, may actually have been N→NE and E→EN, thus rendering differing stimulus generalization profiles.

That the N→E sequence was discriminable from the E→N sequence, as shown in Exp 2 (Fig 4), may be important when considering the co-abuse of nicotine and ethanol. For instance, a heavy smoker might finally indulge in consumption of several alcoholic beverages at the end of a long work day. Assuming that the individual has been smoking all day, this might represent an N→E effect. Similarly, an occasional light smoker or “chipper” might also indulge in consumption of several alcoholic beverages and then later go on to smoke several cigarettes; this scenario would represent an E→N effect. Light smokers may be likely to progress and become heavy smokers (e.g.,Shiffman & Paty, 2006). As the light smoker gradually increases smoking activity over time, he or she might eventually smoke throughout the day, and then consume EtOH and consequently experience the N→E effect. It could be that the juxtaposition of the N→E and E→N compounds augments the propensity to self-administer ethanol and nicotine alone and in combination, consequently leading to progression. Additionally, if one drug precedes another, an associative relationship is likely to be established rendering conditioning among the two drug cues (Clements, Glautier, Stolerman, White, & Taylor, 1996; Glautier, Clements, White, Taylor, & Stolerman, 1996). Under these conditions, nicotine might function as a motivating operation (Troisi, 2003a;Troisi, 2013a) that temporarily increases the reinforcing value of alcohol (Barret, Tichauer, Leyton, & Pihl, 2006; Perkins, Fonte, & Grobe, 2000; Smith, Horan, Gaskin, & Amit, 1999) and consequently occasions a chain of behaviors that culminates in alcohol consumption. Conversely, alcohol consumption might increase the reinforcing value nicotine (Perkins, Fonte, Blakesley-Ball, Stolinski, & Wilson, 2005), which consequently occasions a sequence of behaviors that culminates in smoking.

In relation to the above, in a hallmark study, Griffiths, Bigelow, and Liebson (1976) and later Henningfield, Chait, & Griffiths (1984) found individual differences in smoking typology (total puffs, and puff durations) in alcoholic and nonalcoholic subjects pre-administered with alcohol. All alcoholic subjects reliably increased smoking behavior when pre-administered with alcohol (see also Mintz, Boyd, Rose, Charuvastra, & Jarvik (1985). This may reflect the differences in the subjective and perhaps discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine when preceded by EtOH, as pentobarbital did not promote this effect (see Le et al, 2000, 2003, 2006, 2010 for animal research regarding bi-directional self-administration). Because nicotine and ethanol are consumed in tandem, an “associative” relationship might emerge that modulates reinforcing effects of each drug. For example, Clements, et al (1996) investigated the CS effects of nicotine for an ethanol US in humans, but found inconclusive results. Thus, in addition to the pharmacokinetic factors that influence cross-tolerance between these two drugs for some behavioral effects (Collins, 1990; Collins et al., 1988), it is plausible that perhaps some functional associative learning relationships may also play a role in the development of tolerance and cross-tolerance. The extent to which such associative effects impacted the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine and ethanol, at these doses and in this methodological arrangement, are unknown. Nonetheless, the sequences promoted discriminative control over responding. The contrast between the rates of responding between the two groups with the N→E sequence (Fig 2 A and C) strongly show that the response rate differences were not directly attributable to unconditioned effects on responding but rather were learned in relation to the primary positive reinforcement and non-reinforcement outcomes.

To be sure, mixtures of nicotine and EtOH are discriminable from their elements (Guavin & Holloway, 1993; Troisi et al 2013). In Experiment 2, the discriminative nature of one drug may have been conditional on the presence of the other drug at the time of the training session. The discriminative role of one interoceptive drug state can be conditional on the presence or absence of some other interoceptive drug state as previously demonstrated by Stolerman & Mariathasan (2003). This notion may be analogous to the manner in which exteroceptive SDs interact conditionally in a Pavlovian feature positive paradigm (Rescorla, 1985) in which a CS predicts the presence of the US only when preceded by some other discrete exteroceptive stimulus event and not in its absence. Bevins, Wilkinson, Palmatier, Siebert, and Wiltgen (2006) and Palmatier & Bevins (2008) have found reasonable evidence that nicotine functions well as a feature positive cue and as a feature negative cue in a Pavlovian drug discrimination procedure. In those studies, a light-CS was paired with liquid sucrose in one drug condition but not in the other. Dipper entry occurred to the CS far more often in one drug condition than in the other drug condition (c.f., Duncan, Phillips, Reints, & Schechter, 1979; Jarbe, Laaksonen, & Svensson, 1983; Parker, Schaal, & Miller, 1994). The Stolerman and Mariathasan (2003) investigation was originally an attempt to carry out feature positive “occasion-setting” between two drug states (Stolerman, Hahn, and Mariathasan, 1999). The method employed entailed a feature-positive training regimen, and stimulus control by midazolam in that study was conditional on the presence vs. absence of nicotine.

Of additional importance, the present data corroborate other reports from this laboratory demonstrating that nicotine and alcohol drug discriminations can be established in a one-lever operant go/no-go procedure by alternating between reinforced and non-reinforced training sessions (Troisi, 2003a,b; Troisi 2006; Troisi, 2011; Troisi et al., 2010; cf. Troisi, 2013b for a more detailed theoretical perspective). This author has spoken at length about the utility of the one-lever drug discrimination paradigm for simulating the manner in which interoceptive states might occasion drug taking behavior (see Troisi 2003b for the earliest report; see also Troisi, 2013c). To date, there is one published paper showing that one drug (phencyclidine) can function as an interoceptive state that occasions EtOH self-administration using drug discrimination methodology. Colpaert (1977) cautioned against the use of this methodology for assessing discriminative stimulus properties of drugs (cf., Colpaert et al., 1976), in noting the potential difficulty in controlling for direct effects of the training drugs on response performance. Counterbalancing the discriminative role of the drugs as SD/SΔ can remedy this problem as previously demonstrated in studies by this author (see Troisi 2013b). Inspection of the training data in the present study (Fig 3) revealed no between-group differences in responding of the four rats in the N→E+ SD condition compared to responding of the four rats in the E→N+ SD condition. The SΔ data showed a similar non-difference in responding. Noted earlier, the test data (Fig 4) revealed that the N→E sequence was equally effective as an SD in facilitating operant responding and as an SΔ in inhibiting responding.

Finally, Colpaert (1977) suggested differentiating state-dependent and discriminative stimulus properties of drugs. Drugs which are paired with differential outcomes (reinforcement and non-reinforcement) may favor state-dependent effects between the drug and its predicted outcome. As discussed previously (Troisi, 2011; Troisi & Akins, 2004; Troisi et al., 2010), with the one-lever paradigm each counterbalanced drug condition predicts either reinforcement or non-reinforcement from session to session. By contrast, with the two-lever paradigm, the stimulus control is exerted over the specific response (left vs. right) and the primary reinforcer is available on every session. The one-lever procedure establishes drug→reinforcer (or non-reinforcer) relationships via the operant response. Whereas the two-lever design establishes specific drug→response relationships because primary reinforcement is always operative if the correct response if emitted by the organism; conditioning is between the drug and the response and not the drug and the reinforcer. Indeed, this author has presented sufficient evidence that the drug→response, and not the drug→reinforcer, relationship is most critical in sustaining operant drug discriminations (Troisi et al 2010; Troisi, 2011). In the one-lever (or nose-poke) paradigm, the SD drug condition occasions a response-reinforcer relationship in addition to a drug-reinforcer relationship. The SΔ drug condition predicts non-reinforcement (extinction) of the same response. This arrangement may be directly related to Pavlovian conditioned inhibition training where the CS predicts the nonoccurrence of the US (e.g., Rescorla, 1985). Both the state-dependent learning and drug-discrimination paradigms however do establish stimulus control over behavior, but not all drugs exert state-dependent effects (Overton, 1984). If the current procedure (one-lever, go/no-go) produced state-dependent learning, it was accomplished by a sequential drug arrangement. Nevertheless, in conclusion, the present data suggest that EtOH and nicotine administered in a temporal sequence function effectively as SDs and SΔs conditional on the order in which they are administered within the sequence; hence, conditional temporal interoceptive stimulus control.

Sequential administrations of ethanol and nicotine vs. nicotine and ethanol functioned reliably as discriminative stimuli in rats.

A one manipulanda drug discrimination procedure established stimulus control.

These results were validated in two studies.

Nicotine→Ethanol and Ethanol→Nicotine function reliably to facilitate and inhibit discriminative responding.

Acknowledgments

This research was made possible thanks to the support of a Saint Anselm College Summer Research Grant and by New Hampshire IDeA Network of Biological Research Excellence (NHINBRE) NIH Grant Number 1P20RR030360–01 from the INBRE Program of the National Center for Research Resources. This paper is dedicated to the sick and suffering alcoholics.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

The author has no conflict of interest, financial of otherwise.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Barret SP, Tichauer M, Leyton M, & Pihl RO (2006). Nicotine increases alcohol selfadministration in non-dependent male smokers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 81, 197–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry HB III, Koepfer E, & Lutch J (1965). Learning to discriminate between alcohol and nondrug condition. Psychological Reports, 16, 1072. [Google Scholar]

- Barry HB III, and Krimmer EC (1976). Discriminable stimuli produced by alcohol and other CNS depressants. Psychopharmacology Communications, 2, 323–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HC, & Baros AM (2006). Effect of duration and pattern of chronic ethanol exposure on tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol in C57BL/6J mice. Journal of Pharmacology & Experimental Therapeutics, 319(2), 871–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bevins RA, Wilkinson JL, Palmatier MI, Siebert HL, & Wiltgen SM (2006). Characterization of nicotine’s ability to serve as a negative feature in a Pavlovian appetitive conditioning task in rats. Psychopharmacology, 184, 470–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bienkowski P and Kostowski W (1998). Discrimination of ethanol in rats: Effects of nicotine, diazepam, CGP 40116, and 1-(m-chlorophenyl)-biguanide. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 60, 61–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements K, Glautier S, Stolerman IP White JA, & Taylor C (1996). Classical conditioning in humans: Nicotine as a CS and alcohol as a US. Human Psychopharmacology, 11, 85–95. [Google Scholar]

- Collins A (1990). Interactions of ethanol and nicotine at the receptor level. Recent Developments in Alcoholism, 8, 221–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins A, Burch JB, DeFiebre CM, and Marks MJ (1988). Tolerance to and cross-tolerance between ethanol and nicotine. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 29, 365–373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert FC (1977). Drug-produced cues and states: Some theoretical and methodological inferences In: Discriminative Stimulus Properties of Drugs. Lal H (Ed). Plenum Press; New York: 5–21. [Google Scholar]

- Colpaert FC, Niemegeers CJE, & Jannssen (1976). Theoretical and methodological considerations on drug discrimination learning. Psychopharmacologia, 46, 169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan PM, Phillips J, Reints J, & Schechter MD (1979). Interaction between discrimination of drug states and external stimuli. Psychopharmacology, 61, 105–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmett-Oglesby MW (1990). Tolerance to the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol. Behavioural Pharmacology, 1(6), 497–503. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199000160-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extance K, & Goudie AJ (1981). Inter-animal olfactory cues in operant drug discrimination procedures in rats. Psychopharmacology, 73(4), 363–371. doi: 10.1007/BF00426467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MM, McCracken AD, Davis NL, Ryabinin AE, & Grant KA (2012). Discrimination of ethanol–nicotine drug mixtures in mice: dual interactive mechanisms of overshadowing and potentiation. Psychopharmacology, 224(4), 537–548. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2781-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford MM, Davis NL, McCracken., & Grant KA (2013). Contribution of the NMDA glutamate receptor and nicotinic acetylcholine receptor mechanisms in the discrimination of ethanol-nicotine mixtures. Behavioural Pharmacology, 24(7), 617–622. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3283654216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto GJ, & Grant KA (1997). Attenuation of the discriminative stimulus effects of ethanol by the benzodiazepine partial inverse agonist Ro 15–4513. Behavioural Pharmacology, 8(2–3), 139–146. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glautier S, Clements K, White JA, Taylor C, & Stolerman IP (1996). Alcohol and the reward value of cigarette smoking. Behavioural Pharmacology, 7, 144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant KA (1999). Strategies for understanding the pharmacological effects of ethanol with drug discrimination procedures. Pharmacology, Biochemistry and Behavior, 64, 261–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths RR, Bigelow GE, & Liebson I (1976). Facilitation of human tobacco self-administration by ethanol: A behavioral analysis. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 25, 279–292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guavin DV, and Holloway FH (1993). The discriminative stimulus properties of an ethanol-nicotine mixture in rats. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 7, 52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guavin DV, Youngblood BD, Goulden KL, Briscoe RJ, and Holloway FA (1994). Multidimensional analyses of an ethanol discriminative cue. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 2, 299–309. [Google Scholar]

- Henningfield JE, Chait LD, and Griffiths RR (1984). Effects of ethanol on cigarette smoking by volunteers without histories of alcoholism. Psychopharmacology, 82, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge CW, Grant KA, Becker HC, Besheer J, Crissman AM, Platt DM, & … Shelton KL (2006). Understanding How the Brain Perceives Alcohol: Neurobiological Basis of Ethanol Discrimination. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 30, 203–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarbe TUC, Laaksonen T, & Svensson R (1983). Influence of exteroceptive contextual conditions upon internal drug stimulus control. Psychopharmacology, 80, 31–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandel D, Chen K, Warner LA, Kessler RC, & Grant B (1997). Prevalence and demographic of symptoms of last year dependence on alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, and cocaine in the U.S. population. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 44, 11–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim DJB, and Brioni JD (1995). Modulation of the discriminative stimulus properties of (−)nicotine by diazepam and ethanol. Drug Development Research, 34, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

- Korkosz A, Taracha E, Plaznik A, Wrobel E, Kostowski W, & Bienkowski P (2005). Extended blockade of the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine with low doses of ethanol. European Journal of Pharmacology, 512,165–172. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.02.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lě AD, Corrigall WA, Watchus J, Harding S, Juzytsch W, & Li TK (2000). Involvement of nicotinic receptors in alcohol self-administration. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 24, 155–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Li ZZ, Funk DD, Shram MM, Li TK, & Shaham YY (2006). Increased Vulnerability to Nicotine Self-Administration and Relapse in Alcohol-Naive Offspring of Rats Selectively Bred for High Alcohol Intake. Journal of Neuroscience, 26, 1872–1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Wang AA, Harding SS, Juzytsch WW, & Shaham YY (2003). Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration and reinstates alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology, 168, 216221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lê AD, Lo S, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Marinelli PW, & Funk D (2010). Coadministration of intravenous nicotine and oral alcohol in rats. Psychopharmacology, 208, 475–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, & Goldberg SR (2005). Ethanol does not affect discriminative-stimulus effects of nicotine in rats. European Journal of Pharmacology, 519, 96–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linden A-M, Schmitt U, Leppa E, Wulff P, Wisden W, Luddens H, & Korpi ER (2011). Ro 154513 antagonizes alcohol-induced sedation in mice through 2-type GABAA receptors. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 5, 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariathasan EA, & Stolerman IP (1992). Drug discrimination studies in rats with caffeine and phenylpropanolamine administered separately and as mixtures. Psychopharmacology, 109, 99–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz J, Boyd G, Rose JE, Charuvastra VC, & Jarvik ME (1985). Alcohol increases cigarette smoking: A laboratory demonstration. Addiction Behavior, 10, 203–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olausson P, Jentsch JD, & Taylor JR (2004). Nicotine enhances responding with conditioned reinforcement, Psychopharmacology, 171, 173–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olausson P, Jentsch JD, & Taylor JR (2003). Repeated nicotine exposure enhances rewardrelated learning in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology, 28, 1264–1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton DA (1982). Comparison of the degree of discriminability of various drugs using the T-maze drug discrimination paradigm. Psychopharmacology, 76, 385–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overton DA (1984). State dependent learning and drug discriminations In Iverson LL, Iversen SD, & Snyder SH (Eds.), Handbook of psychopharmacology (Vol. 18, pp. 59–127). New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Palmatier MI, & Bevins RA (2008). Occasion setting by drug states: Functional equivalence following similar training history. Behavioural Brain Research, 195, 260–270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker BK, Schaal DW, and Miller M (1994) Drug discrimination using a Pavlovian conditional discrimination paradigm in pigeons. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 49, 955–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington DL, Durazzo TC, Schmidt TP, Mon A, Abé C, & Meyerhoff DJ (2013). The effects of chronic cigarette smoking on cognitive recovery during early abstinence from alcohol. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research, 37(7), 1220–1227. doi: 10.1111/acer.12089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Fonte C, Blakesley-Ball R, Stolinski A, & Wilson AS (2005). The influence of alcohol pre-treatment on the discriminative stimulus, subjective, and relative reinforcing effects of nicotine. Behavioural Pharmacology, 16(7), 521–529. doi: 10.1097/01.fbp.0000175255.55774.19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkins KA, Fonte C, & Grobe JE (2000). Sex differences in the acute effects of cigarette smoking on the reinforcing value of alcohol. Behavioural Pharmacology, 11, 63–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall PA, Cannady R, & Besheer J (2016). The nicotine + alcohol interoceptive drug state: Contribution of the components and effects of varenicline in rats. Psychopharmacology, 233, (15–16), 3061–3074. 10.1007/s00213-016-4354-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rescorla RA (1985). Conditioned Inhibition and facilitation In: Miller RR and Speer NS (Eds). Information Processing in Animals: Conditioned Inhibition. 299–236. Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Rosecrans JA, & Villanueva HF (1991), Discriminative stimulus properties of nicotine: Mechanisms of transduction In Glennon RA, Jarbe TUC Frankenheim J (Eds),Drug discrimination: Applications to drug abuse research (NIDA Research Monograph No. 116, 101–115) Rockville, MD: National Institute in Drug Abuse. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter MD (1981). Extended schedule transfer of ethanol discrimination. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 14, 23–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter MD & Rosecrans JA (1972) Nicotine as a discriminative cue in rats: Inability of related drugs to produce a nicotine-like cueing effect. Psychopharmacology, 27, 374–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schechter MD & Meehan SM (1992). Further evidence for the mechanisms that may mediate nicotine discrimination. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 41, 807–812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiffman S & Paty J (2006). Smoking patterns and dependence: Contrasting chippers and heavy smokers. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(3), 509–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippenberg TS, & Altshuler HL (1985). A drug discrimination analysis of ethanol-induced behavioral excitation and sedation: the role of endogenous opiate pathways. Alcohol, 2(2), 197–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shoaib M, Thorndike E, Schindler CW, & Goldberg SR (1997). Discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine and chronic tolerance. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, And Behavior, 56(2), 167–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signs SA & Schechter MD (1986). Nicotine-induced potentiation of ethanol discrimination. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior, 24, 769–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BR, Horan JT, Gaskin S, & Amit Z (1999). Exposure to nicotine enhances acquisition of ethanol drinking by laboratory rats in a limited access paradigm. Psychopharmacology, 142, 408412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolerman IP, & Garcha HL (1989). Temporal factors in drug discrimination: Experiments with nicotine. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 3, 88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolerman IP, Garcha HS, Pratt JA, & Kumar R (1984). Role of training dose in discrimination of nicotine and related compounds by rats. Psychopharmacology, 84, 413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolerman IP, Hahn B, & Mariathasan EA (1999). Occasion-setting in drug discrimination using nicotine to signal the appropriate response to midazolam. Behavioural Pharmacology, 10, S89–S90. [Google Scholar]

- Stolerman IP, & Mariathasan EA (2003). Nicotine trace discrimination in rats with midazolam as a mediating stimulus. Behavioural Pharmacology, 14, 55–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II (2003a). Spontaneous recovery during, but not following, extinction of the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine in rats: Reinstatement of stimulus control. The Psychological Record, 53, 579–592. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II. (2003b). Nicotine vs. ethanol discrimination: Extinction and spontaneous recovery of responding. Integrative Physiological Behavioral Sciences, 38, 104–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II (2006). Pavlovian-Instrumental transfer of the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine and alcohol. The Psychological Record, 56, 499–512. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II (2011). Pavlovian extinction of the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine and ethanol in rats varies as a function of the context. The Psychological Record, 61, 199–212. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JI (2013a). Perhaps more consideration of Pavlovian–operant interaction may improve the clinical efficacy of behaviorally based drug treatment programs. The Psychological Record, 63(4), 863–894. doi: 10.11133/j.tpr.2013.63.4.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II (2013b). The Pavlovian vs. operant interoceptive stimulus effects of EtOH: Commentary on Besheer, Fisher, & Durant (2012), Alcohol, 47 (6) 433–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II (2013c). Acquisition, extinction, recovery, and reversal of different response sequences under conditional control by nicotine in rats, The Journal of General Psychology, 140(3), 187–203. doi: 10.1080/00221309.2013.785929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II, & Akins C (2004). The Discriminative stimulus effects of cocaine in a Pavlovian sexual approach paradigm in male Japanese quail. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology, 12, 237–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II, Bryant E, & Kane J (2012). Extinction of the discriminative stimulus effects of nicotine with a devalued reinforcer: Recovery following revaluation. The Psychological Record, 62(4), 707718. [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II, Dooley TF II, & Craig EM (2013). The discriminative stimulus effects of a nicotineethanol compound in rats: Extinction with the parts differs from the whole. Behavioral Neuroscience, 127(6), 899–912. 10.1037/a0034824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troisi JR II, LeMay B, & Jarbe TUC (2010). Transfer to the discriminative stimulus effects of Δ9-THC and nicotine from one operant to another in rats. Psychopharmacology, 212, 171–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]