Introduction:

In the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), the adjusted prevalence of past 30 day cannabis use in pregnant women aged 18–44 years rose from 2.37% in 2002 to 3.85% in 20141. Another study found a relatively similar increase from 4.2% in 2009 to 7.1% in 20142. Corresponding rates of alcohol use (e.g., 2001–2005:11.2% vs. 2011–2013:10.2%) and cigarette smoking (e.g., 2002: 13.3% vs. 2010: 12.3%) during pregnancy have generally decreased3,4,5. Even though these substances are commonly co-used, these reports encourage more detailed characterization of patterns of substance use during the course of pregnancy.

Method:

We used National Survey of Drug Use and Health data from 2002 to 2016 to identify changes in alcohol, cigarette and cannabis use during pregnancy in women aged 18–44 years and identify demographic groups (i.e., age, race/ethnicity, educational level) and trimesters of pregnancy where changes might be more apparent. Analyses were conducted using generalized linear models with adjustments for survey features in STATA (v15). Bonferroni correction for 27 tests was applied, with significance established at P = .002, using 2-tailed, unpaired testing. The Washington University School of Medicine approved the study with waiver of informed consent.

Results:

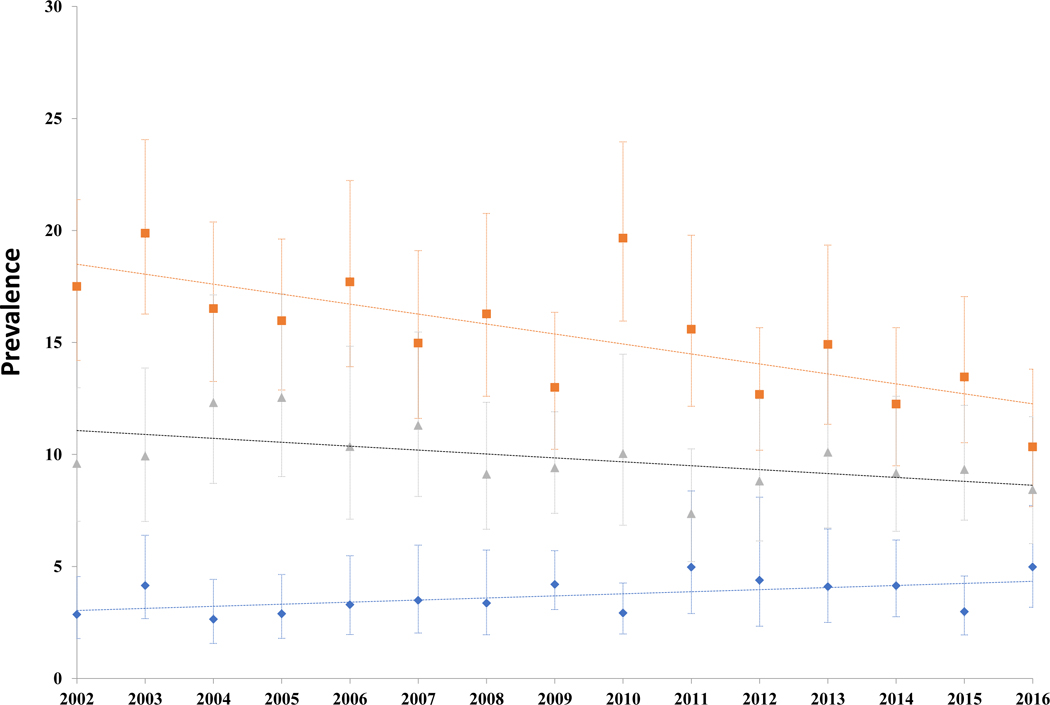

Of 12,988 pregnant women (of n=436,056 women), only those aged 18–25 years (n=8,170) or 26–44 years (n=3,888) were retained in analyses. Of these 12,058 women, 3,554 women reported being in their first trimester of pregnancy. The 2002 survey adjusted prevalence of alcohol, cigarette and cannabis use during pregnancy was 9.59%, 17.5% and 2.85% respectively. By 2016, these adjusted prevalence estimates were 8.43%, 10.34% and 4.98% respectively. A decline in cigarette smoking during pregnancy was noted (Figure 1, Odds Ratio, per year, OR=0.97, p=<.0001). Although not statistically significant, similar decreases in any alcohol use during pregnancy were also noted (OR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.96–1.00; P = .06). In contrast and consistent with a prior National Survey of Drug Use and Health report that used data from 2002 to 2014, a slight increase was noted for cannabis use during the past 30 days in pregnant women (OR, 1.03; 95% CI, 1.00–1.05; P = .048). The prevalences for cannabis use during pregnancy reported here differ slightly from those reported by Brown et al.1 We adjusted our estimates for complex survey features, while Brown and colleagues1 adjusted for a variety of sociodemographic characteristics in a log Poisson setting. There was also a significant decline in co-use of alcohol and cigarettes (OR, 0.94; 95% CI, 0.91–0.97; P = .001).

Figure 1: Trends in past 30-day alcohol use, cigarette smoking, and cannabis use in pregnant women aged 18–44 years (n=12,058).

Gray triangle = alcohol; Orange square = cigarettes; Blue diamond = marijuana; adjusted prevalence (adjustment for survey features only) shown as point estimate, with 95% confidence intervals (vertical bars). Linear trend shown as dotted line.

The prevalences for cannabis use during pregnancy reported here differ slightly from those previously reported by Brown et al., 2017. We adjust our estimates for complex survey features while Brown and colleagues adjusted for a variety of socio-demographic characteristics in a log-Poisson setting.

Results in key demographic groups are reported in the Table. For alcohol use during pregnancy, the decrease was most evident in women aged 18 to 25 years (OR, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.95–1.00]; P = .02). For cigarette smoking during pregnancy, decreases were significant in white women (OR, 0.97 [95% CI, 0.95–0.98]; P < .001), those aged 18 to 25 years (OR, 0.97 [95% CI, 0.95–0.98]; P < .001), and in those reporting high school completion or higher educational levels (OR, 0.97 [95% CI, 0.96–0.99]; P < .001). In contrast, cannabis use showed nominal increases in pregnant women who had completed high school (OR, 1.04 [95% CI, 1.01–1.08]; P = .02). While sample sizes when stratified by trimester were modest, reductions in cigarette smoking were evident in both the first trimester (OR, 0.98 [95% CI, 0.96–0.99]; P = .009) and, significantly, later into pregnancy (OR, 0.97 [95% CI, 0.95–0.99]; P < .001). For alcohol use, reductions were nominally evident in women in their second or third trimester of pregnancy alone (OR, 0.96 [95% CI, 0.93–0.99]; P = .02). For cannabis use, the prevalence showed an increase in the first trimester (OR, 1.04 [95% CI, 1.01–1.08]; P = .02) and was not significant in the second and third trimesters (OR, 1.00 [95% CI, 0.97–1.04]).

Discussion:

Unlike alcohol and cigarettes, prenatal cannabis use has not decreased, especially during the first trimester of pregnancy, a key phase of neural development for the fetus6. Study limitations include underreporting associated with self-report, although some concerns are mitigated by prenatal use being extrapolated from independent items assessing pregnancy status and substance use. Also, some subgroup analyses relied on small sample sizes, although, they provided important insights. For instance, Blacks, those aged 26–44 years, and those with less than a high school education, did not show a significant decrease in prenatal cigarette smoking. Further, and despite the reduced sample size, the significant decrease in prenatal cigarette smoking past the first trimester was highly encouraging as is the general decline in cigarette smoking in non-pregnant women as well. Few subgroup differences were apparent for cannabis. Greater public awareness regarding the consequences of prenatal cannabis exposure on offspring health is necessary.

Table 1.

Odds ratios (OR per year), with their 95% confidence intervals (95% C.I.) indicating strength of the trend in prenatal alcohol, cigarette and cannabis use in 18–44 year old pregnant women in 2002 to 2016 data from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

| Alcohol | Cigarettes | Cannabis | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n=12,058) | 0.982 [0.964 – 1.001] |

0.972**

[0.959 – 0.985] |

1.026*

[1.000 – 1.052] |

| White (n=6,761) | 0.983 [0.961 – 1.005] |

0.968** [0.953 – 0.983] |

1.019 [0.982 – 1.058] |

| Black (n=1,861) | 0.994 [0.956 – 1.032] |

0.990 [0.959 – 1.021] |

1.035 [0.986 – 1.086] |

| Age 18–25 years (n=8,170) | 0.975* [0.954 – 0.996] |

0.966** [0.952 – 0.980] |

1.021 [0.995 – 1.048] |

| Age 26–44 years (n=3,888) | 0.985# [0.960 – 1.011] |

0.987 [0.962 – 1.012] |

1.055 [0.994 – 1.121] |

| Less than a high school education (n=2,597) | 0.977 [0.937 – 1.020] |

0.991 [0.968 – 1.014] |

1.001 [0.949 – 1.057] |

| High school or higher (n=9,461) | 0.981 [0.961 – 1.002] |

0.971** [0.955 – 0.987] |

1.040* [1.005 – 1.076] |

| First trimester (n=3,554) | 0.995 [0.973 – 1.017] |

0.975* [0.956 – 0.994] |

1.044* [1.006 – 1.083] |

| Second or third trimester (n=8,407) | 0.957* [0.927 – 0.990] |

0.969**

[0.952 – 0.986] |

1.001 [0.967 – 1.037] |

p<0.05;

p<0.0019, Bonferroni-corrected for 27 tests (3 substances x 9 tests, i.e., full sample, White, Black, Age 18–25, Age 26–44, Less than high school, High school or higher, first trimester, second or third trimester);

not significant but within 95% C.I. of significant estimate in a related group

Acknowledgements:

Funding: K02DA032573 (AA), U54HD087011 (CNLS); R01DA040411 (AA/RAG), R01DA042195, R21AA025689 (RAG). SL acknowledges the Center for Brain Research in Mood Disorders. Funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

AA and RG conducted analyses. AA had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Footnotes

The authors have no disclosures.

References:

- 1.Brown QL, Sarvet AL, Shmulewitz D, Martins SS, Wall MM, Hasin DS. Trends in Marijuana Use Among Pregnant and Nonpregnant Reproductive-Aged Women, 2002–2014. JAMA. 2017; 317(2):207–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young-Wolff KC, Tucker LY, Alexeeff S, Armstrong MA, Conway A, Weisner C, Goler N. Trends in Self-reported and Biochemically Tested Marijuana Use Among Pregnant Females in California From 2009–2016. JAMA. 2017; 318(24):2490–2491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong VT, Dietz PM, Morrow B, D’Angelo DV, Farr SL, Rockhill KM, England LJ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in smoking before, during, and after pregnancy--Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System, United States, 40 sites, 2000–2010. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2013; 62(6):1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Alcohol use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of childbearing age - United States, 1991–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58(19):529–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tan CH, Denny CH, Cheal NE, Sniezek JE, Kanny D. Alcohol use and binge drinking among women of childbearing age - United States, 2011–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015; 25;64(37):1042–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ouyang M, Dubois J, Yu Q, Mukherjee P, Huang H. Delineation of early brain development from fetuses to infants with diffusion MRI and beyond. Neuroimage. 2018. April 12 pii: S1053–8119(18)30301-X. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]