Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prognostic value of cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) derived mitral annular plane systolic excursion (MAPSE) in a large multicenter population of patients with hypertension.

Background

In patients with hypertension, cardiac abnormalities are powerful predictors of adverse outcomes. Long-axis mitral annular movement plays a fundamental role in cardiac mechanics and is an early marker for a number of pathological processes.

Given the adverse consequences of cardiac involvement in hypertension, we hypothesized that lateral-MAPSE may provide incremental prognostic information in these patients.

Methods

Consecutive patients with hypertension and a clinical indication for CMR at four US medical centers were included in this study (n=1735). Lateral-MAPSE was measured in the 4-chamber cine-view. The primary endpoint was all-cause death. Cox proportional hazards regression modeling was used to examine the association between lateral-MAPSE and death. The incremental prognostic value of lateral-MAPSE was assessed in nested-models.

Results

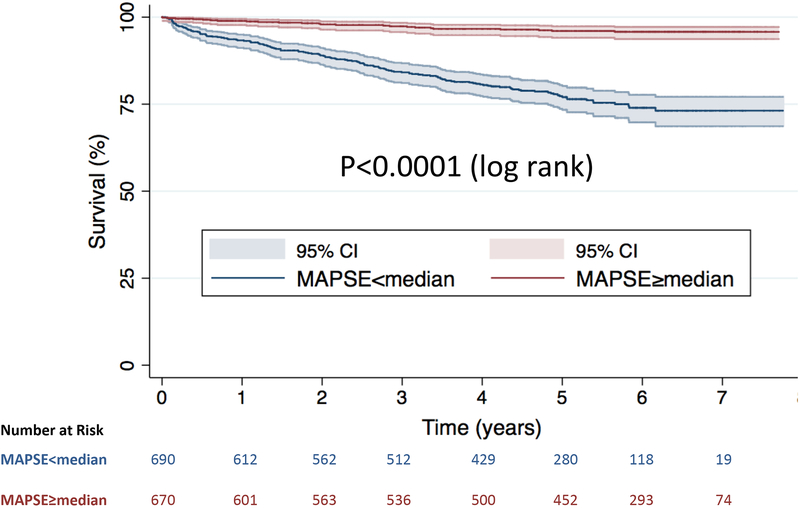

Over a median follow-up of 5.1years, 235 patients died. By Kaplan-Meier-analysis, risk-of-death was significantly higher in patients with lateral-MAPSE<median (10mm)(log-rank p<0.0001). Lateral-MAPSE was associated with risk-of-death after adjustment for clinical and imaging risk factors (HR=1.402 per mm decrease;p<0.001). Addition of lateral-MAPSE in this model resulted in significant-improvement in the C-statistic (0.735 to 0.815;p<0.0001). Continuous-NRI was 0.739(95%CI, 0.601–0.902). Lateral MAPSE remained significantly associated with death even after adjustment for feature tracking global longitudinal strain (HR=1.192 per mm decrease; p<0.001). Lateral-MAPSE was independently associated with death amongst the subgroup of patients with preserved ejection fraction(HR=1.339;p<0.001) and in those without history of myocardial infarction(HR=1.390;p<0.001).

Conclusions

CMR derived lateral-MAPSE is a powerful independent predictor of mortality in patients with hypertension and a clinical indication for CMR, incremental to common clinical and CMR risk factors. These findings may suggest a role for CMR derived lateral-MAPSE in identifying hypertensive patients at highest risk of death.

Keywords: hypertension, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, prognosis, mortality, cardiomyopathy, left ventricular function, mitral annular plane systolic excursion, atrioventricular plane displacement (AVPD), global longitudinal strain

INTRODUCTION

In patients with hypertension, the heart is a major target of end organ damage. Moreover, cardiac abnormalities including left ventricular hypertrophy and dysfunction have been shown to be powerful predictors of adverse outcomes in these individuals(1,2). As a consequence, echocardiographic evaluation of myocardial structure and function is commonly used in the risk assessment of patients with hypertension(2).

Over recent years it has become apparent that long axis mitral valve movement plays a fundamental role in cardiac mechanics and appears to be an early marker for a number of pathological states(3–5). Small single center echocardiographic studies have described abnormalities of longitudinal mitral annular motion and global longitudinal strain in patients with hypertension, which appear to have adverse prognostic significance(6–10). Moreover, we have recently shown that lateral mitral annular plane systolic excursion (MAPSE), measured using cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging is a powerful independent predictor of mortality in patients with both preserved and reduced systolic function, incremental to common clinical and imaging risk factors(11,12). Given the known adverse consequences of myocardial involvement in hypertension, we hypothesized that CMR derived lateral MAPSE may provide incremental prognostic information in these patients.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the prognostic value of CMR derived lateral MAPSE in a large multicenter population of patients with hypertension undergoing CMR at four US medical centers.

METHODS

Study Design

Four geographically diverse medical centers in the United States participated in this observational, multicenter study. The University of Illinois in Chicago served as the data-coordinating center using a cloud-based database (CloudCMR, www.cloudCMR.com) containing de-identified searchable data from consecutive patients with full DICOM datasets from the participating centers. Institutional review board approval was obtained at each center.

Study Population

Consecutive patients with a diagnosis of hypertension (documented in the electronic medical record by the referring physicians) and a clinical indication for CMR who had undergone CMR in 2011 with both cine and late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) imaging formed the study population of 1735 patients. Exclusion criteria included uninterpretable image quality for lateral MAPSE assessment, severe valvular disease, as well as hypertrophic and infiltrative cardiomyopathies. Baseline demographics were obtained by local site investigators at the time of the clinical study.

CMR Acquisition

Images were acquired with phased-array receiver coils according to the routine scan protocol at each site using a variety of scanners from all three major vendors (Siemens, Philips and General Electric) at both 1.5 and 3 Tesla. A typical protocol included steady-state free-precession cine images acquired in multiple short-axis and three long-axis views with short-axis views obtained every 1cm to cover the entire left ventricle. Typical temporal resolution of cine images was <45msec. LGE imaging was performed 10–15 minutes after Gadolinium contrast (0.15 mmol/kg) administration using a 2D segmented gradient echo inversion-recovery sequence in the same views used for cine-CMR. Inversion delay times were typically 280 to 360 ms.

CMR Analysis and Lateral MAPSE Assessment

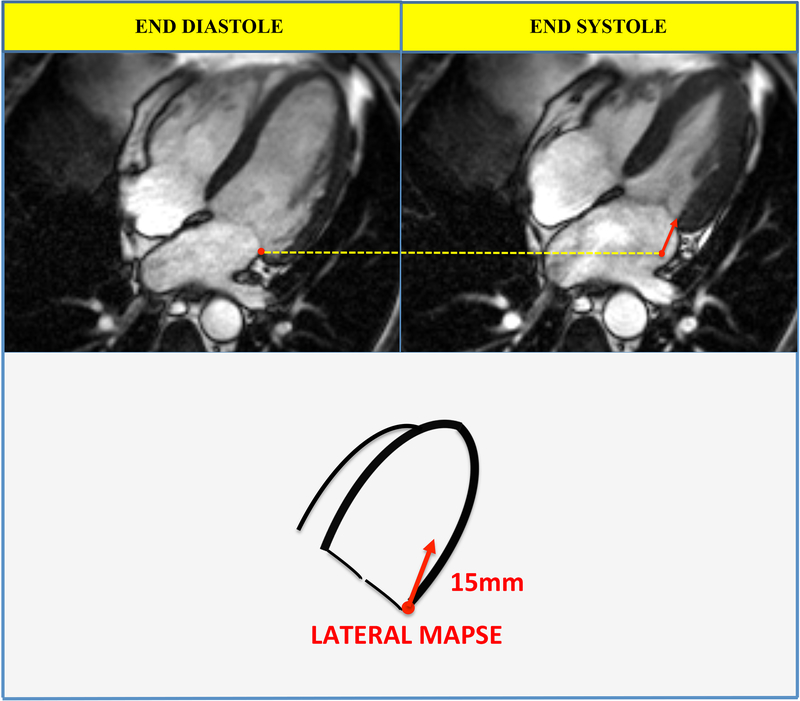

The study site investigators analyzed images on locally available workstations and were blinded to follow-up data. Delayed enhancement and feature tracking global longitudinal strain (GLS) was assessed as described previously(13–18). Lateral MAPSE was measured as previously described(11,12). In brief, the lateral mitral annular position was marked at end-diastole in the 4-chamber view (Figure 1). Images were advanced frame-by-frame to the end of systole (just before opening of the mitral valve) where the lateral mitral annular position was again identified. Lateral MAPSE was defined as the distance between the lateral mitral annular position at the end of diastole to the lateral mitral annular position at the end of systole (Figure 1). Measurements were performed manually by a single physician, who was blinded to patient outcomes and information (S.R.).

Figure 1. Measurement of lateral MAPSE.

The lateral mitral annulus position was recorded in the 4-chamber view at end diastole (upper left panel) and end systole (upper right panel). Lateral MAPSE was defined as the distance between the lateral mitral annulus position at the end of diastole and the lateral mitral annulus position at the end of systole (lower panel, red arrow). In this case lateral MAPSE was 15mm. The yellow dotted line marks the position of the lateral mitral annulus at end diastole.

Follow-up

Patients were followed for the primary outcome of all cause mortality using the United States Social Security Death Index. Time to event was calculated as the period between the CMR study and death. Patients who did not experience the primary outcome were censored at the time of assessment.

Statistical Analysis

Normally distributed data were expressed as mean ± SD. Differences in baseline characteristics were compared with the Student’s t-test for continuous variables and the chi-squared test for dichotomous variables. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to evaluate the relationship between lateral MAPSE and time to the primary outcome of all cause mortality. We used Cox proportional hazards regression modeling to examine the association between lateral MAPSE and all cause mortality. All models were assessed for collinearity and proportional hazards assumption. For the multivariable models, clinical and imaging risk factors which were univariate predictors (at p≤0.10) were considered as covariates and a backward elimination strategy (at p≤0.10 for model retention) was applied. To assess the added prognostic value of lateral MAPSE, the final model was compared with a model in which lateral MAPSE was not included. The change in overall log-likelihood ratio and C-statistic were calculated as well as the integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) (19). Formal risk reclassification analyses were conducted with calculation of continuous net reclassification improvement (NRI)(19). A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using STATA (StataCorp, TX).

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Table 1 summarizes baseline patient characteristics stratified by lateral MAPSE above and below the median (10mm). The mean age of the study population was 62.6(±13.2) years. Fifty-eight percent of patients were male and 34.5% had diabetes mellitus. The mean ejection fraction was 49.3 ± 17.4% and LGE was present in 42.7% of patients. Overall 229 (13.2%) patients had atrial fibrillation. The primary indications for CMR were: coronary artery disease/ischemic heart disease (33%), heart failure/cardiomyopathy (28%), arrhythmias (10%), dyspnea (8%), chest pain (8%), vascular disease (7%), valve disease (4%), others (2%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of whole study population stratified by lateral MAPSE above and below the median (10mm).

| CHARACTERISTICS | Total | MAPSE <10mm |

MAPSE ≥10mm |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (±SD), years | 62.6 (±13.2) | 64.5 (±13.1) | 60.9 (±13.1) | <0.001 |

| Male % | 57.5 | 59.3 | 55.9 | 0.180 |

| BMI (±SD), kg/m2 | 30.0 (±8.8) | 29.7 (±10.6) | 30.4 (±6.6) | 0.073 |

| Diabetes % | 34.5 | 37.7 | 31.5 | 0.007 |

| Hyperlipidemia % | 64.2 | 66.2 | 62.3 | 0.088 |

| Smoking % | 11.4 | 13.3 | 9.8 | 0.023 |

| History of MI % | 21.6 | 25.8 | 18.1 | <0.001 |

| Aspirin % | 62.0 | 67.0 | 57.3 | <0.001 |

| Statin % | 57.3 | 59.9 | 54.9 | 0.038 |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB % | 50.2 | 55.8 | 44.9 | <0.001 |

| Beta Blocker % | 39.0 | 45.2 | 33.2 | <0.001 |

| Diuretic % | 43.6 | 49.5 | 38.0 | <0.001 |

| Heart Rate (±SD), beats/min | 73.4 (±15.0) | 77.3 (±15.7) | 69.7 (±13.2) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP (±SD), mmHg | 131.7(±21.2) | 129.0(±21.1) | 134.2(±21.1) | <0.001 |

| Diastolic BP (±SD), mmHg | 75.0(±13.3) | 75.4(±13.6) | 74.5(±13.1) | 0.210 |

| LVEDV index (±SD), ml/m2 | 75.5 (±31.7) | 83.1 (±35.4) | 68.2 (±25.8) | <0.001 |

| LVESV index (±SD), ml/m2 | 39.4 (±30.1) | 50.6 (±33.8) | 28.7 (±21.3) | <0.001 |

| LV mass index (±SD), g/m2 | 97.4 (±39.8) | 105.4 (±42.2) | 89.9 (±35.9) | <0.001 |

| LGE present % | 42.7 | 55.6 | 30.5 | <0.001 |

| LGE extent (±SD), % | 5.1 (±8.7) | 7.1 (±9.8) | 3.3 (±6.9) | <0.001 |

| LVEF (±SD), % | 49.3 (±17.4) | 41.2 (±17.0) | 57.0 (±13.9) | <0.001 |

| GLS (±SD) | −15.2 (±6.5) | −11.4 (±5.4) | −18.6 (±5.3) | <0.001 |

ACE=Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, ARB=Angiotensin Receptor Blocker, BMI=Body Mass Index, GLS=Global Longitudinal Strain, LGE=Late Gadolinium Enhancement, LVEDV =Left Ventricular End Diastolic Volume Index, LVEF=Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction, LVESV =Left Ventricular End Systolic Volume Index, MAPSE=Mitral Annular Plane Systolic Excursion, MI=Myocardial Infarction, SD=standard deviation.

Primary Outcome

Of the 1735 patients in this study, 235 died during a median follow-up of 5.1years (interquartile range: 3.4–6.1 years).

Outcomes Stratified by lateral MAPSE

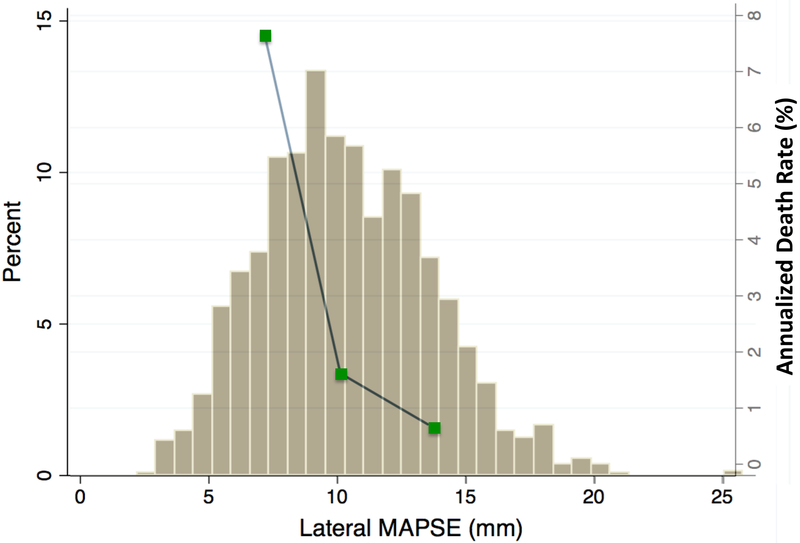

When stratified by the median value of lateral MAPSE (10mm), Kaplan-Meier analysis showed significantly increased risk of death in those with lateral MAPSE<median (log-rank p<0.0001) (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows the population distribution of lateral MAPSE and demonstrates the increasing annualized death rate with decreasing tertiles of lateral MAPSE.

Figure 2. Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

Stratified by lateral MAPSE above and below the median value for the whole population.

Figure 3. Distribution of lateral MAPSE and its relationship with annualized mortality rate.

Histogram showing distribution of lateral MAPSE values amongst the patient population (y axis on the left). Death occurred more frequently in patients with lower lateral MAPSE values. Green boxes represent annualized death rates for tertiles of lateral MAPSE (y axis on the right).

Multivariable Analysis and Incremental Prognostic Value

After multivariate adjustment for clinical and imaging risk factors (excluding GLS), lateral MAPSE as a continuous variable remained a significant independent predictor of death (HR=1.402 per mm decrease; p<0.001) i.e. each 1mm worsening in lateral MAPSE was associated with an 40.2% increase risk of death (Table 2, model 1). Addition of lateral MAPSE into the model with clinical and imaging predictors resulted in significant increase in the C-statistic (from 0.735 to 0.815 p<0.0001) and a significant increase in model Chi square value (from 143.0 to 293.6; p<0.001). This was associated with significant integrated discrimination improvement of 0.114 (95% CI, 0.079–0.156), and a continuous NRI of 0.739 (95% CI, 0.601–0.902). LGE remained a significant independent predictor of death in the final model.

Table 2.

Multivariable model of mortality with lateral MAPSE adjusted to univariate clinical and imaging predictors (at p≤0.10) for the whole population.

| VARIABLES | Univariable | Multivariable Model 1 |

Multivariable Model 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

|

| Age | 1.034 (1.023–1.045) | <0.001 | 1.021 (1.010–1.033) | <0.001 | 1.016 (1.006–1.027) | 0.003 |

| Male | 1.413 (1.073–1.859) | 0.014 | - | - | - | - |

| BMI | 0.983 (0.963–1.003) | 0.095 | - | - | - | - |

| Diabetes | 1.372 (1.057–1.781) | 0.018 | - | - | - | - |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.074(0.819–1.409) | 0.606 | - | - | - | - |

| Smoking | 1.176(0.786–1.758) | 0.430 | - | - | - | - |

| History of MI | 1.394 (1.043–1.863) | 0.025 | - | - | - | - |

| Aspirin | 1.194(0.907–1.571) | 0.205 | - | - | - | - |

| Statin | 0.972 (0.746–1.267) | 0.833 | - | - | - | - |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 0.673 (0.429–1.055) | 0.084 | - | - | - | - |

| Beta Blocker | 1.006(0.762–1.327) | 0.968 | - | - | - | - |

| Diuretic | 1.472 (1.132–1.913) | 0.004 | - | - | - | - |

| Heart Rate | 1.023 (1.016–1.031) | <0.001 | 1.013 (1.004–1.021) | 0.004 | - | - |

| Systolic BP | 0.992 (0.985–0.998) | 0.009 | - | - | 1.012 (1.005–1.020) | 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP | 0.984 (0.974–0.994) | 0.002 | 0.983 (0.973–0.993) | 0.001 | 0.979 (0.967–0.990) | <0.001 |

| LVEDV index | 1.006 (1.002–1.010) | 0.001 | - | - | - | - |

| LVESV index | 1.008 (1.005–1.012) | <0.001 | - | - | - | - |

| LV mass index | 1.004 (1.001–1.007) | 0.005 | - | - | - | - |

| LGE | 2.701 (2.061–3.541) | <0.001 | 1.622 (1.211–2.174) | 0.001 | - | - |

| Lateral MAPSE* | 1.477 (1.403–1.555) | <0.001 | 1.402 (1.323–1.486) | <0.001 | 1.192 (1.113–1.277) | <0.001 |

| LVEF‡ | 1.024 (1.016–1.031) | <0.001 | - | - | - | - |

| GLS | 1.210 (1.180–1.240) | <0.001 | Not in model | - | 1.180 (1.137–1.224) | <0.001 |

Model 1 does not include GLS. Model 2 includes GLS. ACE=Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, ARB=Angiotensin Receptor Blocker, BMI=Body Mass Index, GLS=Global Longitudinal Strain, LGE=Late Gadolinium Enhancement, LVEDV =Left Ventricular End Diastolic Volume Index, LVEF=Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction, LVESV =Left Ventricular End Systolic Volume Index, MAPSE=Mitral Annular Plane Systolic Excursion, MI=Myocardial Infarction, SD=standard deviation.

per mm decrease.

per % decrease.

Lateral MAPSE (as a continuous variable) remained significantly associated with death after multivariate adjustment for clinical and imaging risk factors including GLS (HR=1.192 per mm decrease; p<0.001) (Table 2, model 2). GLS remained a significant predictor of events in the final multivariable model (HR=1.180; p<0.001). Thus both lateral MAPSE and GLS are independently associated with death in this population. Moreover, there was no evidence of problematic strong collinearity between GLS and lateral MAPSE (Variance Inflation Factor was 1.37). Addition of lateral MAPSE into the model with clinical and imaging predictors including GLS led to a borderline increase in the C-statistic (from 0.814 to 0.822 p=0.07) and a significant increase in model Chi square value (from 338.7 to 365.8; p<0.001). This was associated with significant integrated discrimination improvement of 0.022 (95% CI, 0.008–0.046), and a continuous NRI of 0.491 (95% CI, 0.325–0.651).

Prognostic Value of lateral MAPSE in patients with preserved ejection fraction

Seventy-seven deaths occurred amongst the 896 patients with preserved ejection fraction (≥50%). When stratified by the median value of lateral MAPSE (12mm), Kaplan-Meier analysis showed significantly increased risk of death in those with lateral MAPSE<median (log-rank p<0.0001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

Stratified by lateral MAPSE above and below the median value for patients with preserved ejection fraction.

After multivariate adjustment for clinical and imaging risk factors (excluding GLS), every 1mm decrease in lateral MAPSE (as a continuous variable) was associated with a 33.9% increase risk-of-death (HR=1.339; p<0.001) (Table 3, model 1).

Table 3.

Multivariable model of mortality with lateral MAPSE adjusted to univariate clinical and imaging predictors (at p≤0.10) for patients with preserved ejection fraction.

| VARIABLES | Univariable | Multivariable Model 1 |

Multivariable Model 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

|

| Age | 1.049 (1.028–1.071) | <0.001 | 1.040 (1.018–1.064) | <0.001 | 1.035 (1.014–1.056) | 0.001 |

| Male | 1.548 (0.959–2.500) | 0.070 | - | - | - | - |

| BMI | 0.948 (0.912–0.985) | 0.004 | 0.955 (0.917–0.994) | 0.025 | 0.953 (0.914–0.994) | 0.025 |

| Diabetes | 1.378 (0.865–2.197) | 0.185 | - | - | - | - |

| Hyperlipidemia | 0.932 (0.593–1.463) | 0.758 | - | - | - | - |

| Smoking | 0.571 (0.180–1.812) | 0.299 | - | - | - | - |

| History of MI | 0.897 (0.390–2.066) | 0.796 | - | - | - | - |

| Aspirin | 1.010 (0.644–1.584) | 0.966 | - | - | - | - |

| Statin | 1.078 (0.685–1.696) | 0.745 | - | - | - | - |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 0.960(0.604–1.523) | 0.859 | - | - | - | - |

| Beta Blocker | 0.855 (0.499–1.465) | 0.563 | - | - | - | - |

| Diuretic | 1.497(0.948–2.362) | 0.087 | - | - | - | - |

| Heart Rate | 1.025 (1.011–1.040) | <0.001 | 1.025 (1.010–1.040) | 0.001 | - | - |

| Systolic BP | 1.001 (0.990–1.012) | 0.828 | - | - | - | - |

| Diastolic BP | 0.991 (0.973–1.009) | 0.308 | - | - | - | - |

| LVEDV index | 0.993 (0.980–1.005) | 0.250 | - | - | - | - |

| LVESV index | 1.001 (0.981–1.022) | 0.916 | - | - | - | - |

| LV mass index | 1.002 (1.001–1.003) | 0.025 | 1.008 (1.001–1.015) | 0.020 | - | - |

| LGE | 1.955 (1.214–3.151) | 0.008 | - | - | - | - |

| Lateral MAPSE* | 1.417 (1.300–1.545) | <0.001 | 1.339 (1.224–1.465) | <0.001 | 1.190 (1.083–1.306) | <0.001 |

| LVEF‡ | 1.035 (1.000–1.071) | 0.046 | - | - | - | - |

| GLS | 1.269 (1.211–1.330) | <0.001 | Not in model | - | 1.210 (1.147–1.277) | <0.001 |

Model 1 does not include GLS. Model 2 includes GLS. ACE=Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, ARB=Angiotensin Receptor Blocker, BMI=Body Mass Index, GLS=Global Longitudinal Strain, LGE=Late Gadolinium Enhancement, LVEDV =Left Ventricular End Diastolic Volume Index, LVEF=Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction, LVESV =Left Ventricular End Systolic Volume Index, MAPSE=Mitral Annular Plane Systolic Excursion, MI=Myocardial Infarction, SD=standard deviation.]

per mm decrease.

per % decrease.

Lateral MAPSE (as a continuous variable) remained significantly associated with death after multivariate adjustment for clinical and imaging risk factors including GLS (HR=1.190 per mm decrease; p<0.001) (Table 3, model 2). GLS remained a significant predictor of events in the final multivariable model (HR=1.210; p<0.001). Thus both MAPSE and GLS are independently associated with death in this subpopulation.

Prognostic Value of lateral MAPSE in patients without history of myocardial infarction

One hundred and seventy two deaths occurred amongst the 1360 patients without history of myocardial infarction. When stratified by the median value of lateral MAPSE (10.4mm), Kaplan-Meier analysis showed significantly increased risk of death in those with lateral MAPSE<median (log-rank p<0.0001) (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Kaplan-Meier survival curves.

Stratified by lateral MAPSE above and below the median value for patients with no history of myocardial infarction.

After multivariate adjustment for clinical and imaging risk factors (excluding GLS), every 1mm decrease in lateral MAPSE (as a continuous variable) was associated with a 39.0% increase risk-of-death (HR=1.390; p<0.001) (Table 4, model 1). LGE remained a significant independent predictor of death in the final model.

Table 4.

Multivariable model of mortality with lateral MAPSE adjusted to univariate clinical and imaging predictors (at p≤0.10) for patients without history of myocardial infarction.

| VARIABLES | Univariable | Multivariable Model 1 |

Multivariable Model 2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

P Value |

|

| Age | 1.040 (1.027–1.053) | <0.001 | 1.026 (1.013–1.039) | <0.001 | 1.025 (1.013–1.037) | <0.001 |

| Male | 1.467(0.903–2.385) | 0.118 | - | - | - | - |

| BMI | 0.961 (0.937–0.986) | 0.002 | - | - | - | - |

| Diabetes | 1.453 (1.070–1.972) | 0.018 | - | - | - | - |

| Hyperlipidemia | 1.138 (0.836–1.550) | 0.409 | - | - | - | - |

| Smoking | 1.283 (0.766–2.148) | 0.360 | - | - | - | - |

| Aspirin | 1.159 (0.851–1.578) | 0.347 | - | - | - | - |

| Statin | 1.054 (0.776–1.431) | 0.738 | - | - | - | - |

| ACE inhibitor or ARB | 1.123 (0.828–1.522) | 0.457 | - | - | - | - |

| Beta Blocker | 1.099 (0.793–1.522) | 0.572 | - | - | - | - |

| Diuretic | 1.520 (1.118–2.066) | 0.008 | - | - | - | - |

| Heart Rate | 1.022 (1.013–1.031) | <0.001 | 1.012 (1.002–1.022) | 0.018 | - | - |

| Systolic BP | 0.995 (0.987–1.002) | 0.166 | - | - | - | - |

| Diastolic BP | 0.985 (0.973–0.996) | 0.009 | 0.982 (0.971–0.994) | 0.002 | 0.987 (0.975–0.998) | 0.022 |

| LVEDV index | 1.004(1.000–1.009) | 0.070 | - | - | - | - |

| LVESV index | 1.007 (1.003–1.012) | 0.002 | - | - | - | - |

| LV mass index | 1.004 (1.001–1.007) | 0.021 | - | - | - | - |

| LGE | 2.960 (2.187–4.006) | <0.001 | 1.721 (1.236–2.397) | 0.001 | - | - |

| Lateral MAPSE* | 1.477 (1.393–1.567) | <0.001 | 1.390 (1.299–1.486) | <0.001 | 1.178 (1.088–1.275) | <0.001 |

| LVEF‡ | 1.022 (1.031–1.071) | <0.001 | - | - | - | - |

| GLS | 1.211 (1.178–1.245) | <0.001 | Not in model | - | 1.159 (1.112–1.207) | <0.001 |

Model 1 does not include GLS. Model 2 includes GLS. ACE=Angiotensin Converting Enzyme, ARB=Angiotensin Receptor Blocker, BMI=Body Mass Index, GLS=Global Longitudinal Strain, LGE=Late Gadolinium Enhancement, LVEDV =Left Ventricular End Diastolic Volume Index, LVEF=Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction, LVESV =Left Ventricular End Systolic Volume Index, MAPSE=Mitral Annular Plane Systolic Excursion, MI=Myocardial Infarction, SD=standard deviation.

per mm decrease.

per % decrease.

Lateral MAPSE (as a continuous variable) remained significantly associated with death after multivariate adjustment for clinical and imaging risk factors including GLS (HR=1.178 per mm decrease; p<0.001) (Table 4, model 2). GLS remained a significant predictor of events in the final multivariable model (HR=1.159; p<0.001). Thus both MAPSE and GLS are independently associated with death in this subpopulation

DISCUSSION

This study shows that lateral MAPSE measured by CMR is a powerful independent predictor of mortality, in a large multicenter population of patients with hypertension and a clinical indication for CMR. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study to date looking at the role of CMR in hypertension. We have demonstrated that lateral MAPSE provides prognostic information incremental to common clinical and CMR risk factors - including LV mass, ejection fraction and late-gadolinium-enhancement. Moreover, lateral MAPSE remained significantly associated with death even after adjustment for feature tracking GLS. Its measurement requires no specialized pulse sequences, additional scanning time or specialized post processing software. These findings highlight the importance of long-axis function in individuals with hypertension and suggest a role for CMR derived lateral MAPSE in identifying hypertensive patients at highest risk of death.

Long axis function in cardiac mechanics

Long axis function plays a fundamental role in cardiac mechanics - aiding ventricular ejection by reducing long axis LV cavity size as the mitral annulus is pulled towards the apex(3,4) and contributing to radial wall thickening by conservation of mass. The contribution of long axis function to overall stroke volume has been assessed using CMR in normal subjects, elite athletes and patients with dilated cardiomyopathy(5). These studies suggested that as much as 60% of stroke volume could be explained by long axis function. In diastole, the mitral annulus bounces back to its equilibrium position moving around the column of blood passing through the mitral valve, thus significantly contributing to ventricular filling(3,4).

Perhaps because of their subendocardial location, the more longitudinally aligned myocardial fibers appear to be extremely sensitive to disturbance by various pathological processes, as suggested by rapid reduction of mitral annular motion with ischemia induction in experimental models(3).

MAPSE and Prognosis

Long axis function can be assessed by measuring changes in the position of the mitral annulus, since the cardiac apex is fixed with respect to the chest wall (4). Initial studies used M-mode echocardiography to directly follow the position of the mitral annulus and measure MAPSE(20). There is a large and growing body of echocardiographic literature demonstrating the prognostic value of MAPSE in a wide variety of conditions including hypertension, atrial fibrillation, post-myocardial infarction, ischemic cardiomyopathy, heart failure (with reduced or preserved ejection fraction), aortic stenosis, tetralogy of Fallot, amyloidosis, post heart transplantation, and post anthracycline therapy(20).

More recently Rangarajan et al used CMR to show that lateral MAPSE measured from 4-chamber cine images, is independently associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes in an unselected group of 400 consecutive patients undergoing CMR at a single center (12). Subsequently we reported the powerful prognostic value of lateral MAPSE in a large multi-center population of patients with cardiomyopathy and demonstrated good inter and intra-observer variability for its measurement (11). Others have shown analogous findings in patients with non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, using a CMR MAPSE derived parameter of long-axis function to predict a composite outcome of adverse cardiac events (21,22). Gjesdal et al examined the prognostic value of a similarly derived CMR MAPSE parameter of long axis function from 1651 individuals in the MESA cohort who were free of cardiovascular disease(23). After a median of 6.8 years of follow-up, long-axis function was found to be an independent predictor of cardiovascular outcomes(23).

MAPSE in Hypertension

Prior echocardiographic studies have shown that MAPSE is significantly reduced in hypertensive patients even if ejection fraction is preserved(6,10,24). In a small single center study Ballo et al examined the prognostic value of MAPSE in 156 patients with hypertension and preserved ejection fraction(6). Over a mean follow-up of 23 months, 24 patients suffered a composite endpoint of heart failure hospitalization, new-onset angina, nonfatal myocardial infarction, coronary revascularization, transient ischemic attack, stroke, and cardiovascular death(6). MAPSE was found to be an independent predictor of the composite endpoint(6). Using CMR we have extended these preliminary observations to a large multicenter population. Moreover we have shown that lateral MAPSE provides independent prognostic information incremental to clinical and CMR imaging variables. Importantly, we have also demonstrated that lateral MAPSE remains a powerful independent prognostic marker even in hypertensive patients with preserved ejection fraction or without a history of myocardial infarction, potentially allowing early identification of patients at highest risk.

The precise mechanism underlying the association between impaired lateral MAPSE and adverse outcomes is unclear. It has been suggested that the subendocardial myocardial fibers (which are more longitudinally aligned) are extremely sensitive to disturbance because of greater compressive forces and higher oxygen consumption (3,4,20,25). The subendocardial fibers are therefore more vulnerable to increased wall stress and imbalances between oxygen supply and demand which may be seen in early stages of hypertension. Interestingly, in an animal model of hypertension, longitudinal function was shown to progressively deteriorate with time compared to control animals and was associated with histological subendocardial fibrosis(26).

MAPSE and GLS

MAPSE and GLS provide differing measures of left ventricular function. GLS uses specialized software to give a global measure of relative longitudinal change in length by tracking patterns within the myocardium and can also provide segmental information. There is a large body of prognostic literature based on speckle tracking echocardiography with a growing number of outcome studies utilizing CMR feature tracking techniques(17,18,27). By contrast, lateral MAPSE is a simple measure of displacement which incorporates primarily basal longitudinal movement and possibly an element of mitral annular radial contraction(28). It requires no specialized software for its measurement.

Several prior single center echocardiographic studies have described abnormalities of MAPSE and GLS in patients with hypertension, which appear to have adverse prognostic significance(6–10). However, to the best of our knowledge there has been no analysis of the relative prognostic value of these two parameters. In this study we have shown that CMR derived lateral MAPSE and feature tracking GLS are both independently associated with death in patients with hypertension and provide complimentary prognostic information. Lateral MAPSE provides incremental prognostic information to clinical and imaging variables including GLS. Conversely GLS provides incremental prognostic information to clinical and imaging variables including lateral MAPSE (increasing the model Chi square value from 280.1 to 365.8; p<0.001). Given inter-modality and inter-vendor differences in GLS acquisition methods, these findings are not necessarily applicable to echocardiography. Therefore, the relative prognostic value of speckle tracking derived GLS and echo derived MAPSE requires further study both in hypertension and other conditions.

Role of CMR in Hypertension

Echocardiography has a well-established role for assessment of cardiac end organ damage and prognosis in hypertension(1,2). However, CMR is the gold standard for measurement of ventricular volumes, function and mass; and for myocardial tissue characterization with detection of myocardial fibrosis. As such it may play a role in assessment of some patients with hypertension and hypertensive heart disease (29,30). It also allows identification of diseases that may mimic hypertensive LVH(29–31). The presence of focal myocardial fibrosis as detected by LGE is a powerful predictor of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in numerous conditions including hypertension(14,32–35). Krittayaphong et al showed that LGE is a powerful and independent predictor of cardiac death or myocardial infarction in a population of 1644 patients with hypertension followed for a mean of 29 months (33). Likewise LGE was a significant predictor of death in our patient cohort. Given the co-existence of coronary artery disease, LGE maybe seen in a subendocardial pattern as well as in a more patchy non-coronary midmyocardial distribution (29,36,37). Our study suggests that CMR can provide significant incremental prognostic information in patients with hypertension using lateral MAPSE as a marker of longitudinal function. Moreover, measurements of lateral MAPSE can be obtained from conventional cine CMR images without the need for specialized pulse sequences, propriety software, or additional imaging time. Better identification of high-risk hypertensive patients may allow closer follow-up and more directed therapies to be applied. How this information will affect clinical care requires further investigation and future studies are warranted to explore the role of CMR derived lateral MAPSE in clinical decision making. These studies will need to demonstrate that imaging driven patient management improves specific outcomes before such an approach could be advocated.

Limitations

Although this is a multicenter study, the patients in this paper may not be representative of all hypertensive patients in the community and we recommend caution in generalizing our findings to all individuals with hypertension. The study population was comprised of patients with a diagnosis of hypertension and a clinical indication for CMR. Thus this was not an isolated hypertension cohort. Moreover, since this is a CMR study, there is further selection bias related to being able to undergo a CMR exam, resulting in exclusion of patients with large body size, severe renal impairment, severe claustrophobia or those with pacemakers and ICDs. Information regarding specific cardiovascular outcomes such as myocardial infarction, sudden death, transplantation, revascularization, stroke or hospitalization was not available. Follow-up data in this study was limited to the primary endpoint of all cause death and the cause of death was not known. However, many have argued that all–cause mortality is an extremely important and appropriate study endpoint because it is unbiased and clinically relevant, which is often not the case for other cardiac outcomes such as revascularization or hospitalization(38–40). Use of cardiac-death instead of all-cause death as an end point can be problematic for many reasons since data obtained from death certificates or from medical records are limited, biased and often inaccurate. In addition, determination of cause of death is often difficult due to multiple comorbidities, low autopsy rates and poor understanding of complex diseases(40). We therefore believe that all-cause mortality is a highly important and valid primary end-point for this study. T1 mapping techniques were not clinically widely available at the time of CMR image acquisition and therefore could not be performed on these clinical scans across multiple sites with different vendors and field strengths. Thus although diffuse myocardial interstitial fibrosis is known to occur in hypertension, it was not quantified in this study.

Our simple lateral MAPSE measurements did not account for possible translational movements of the mitral annulus or for heart size differences, which may confound assessment of long axis function. More complex methods for assessing mitral annulus long axis motion include use of multiple long axis views, with normalization to body size, or calculation of various changes in apex-to-annulus length expressed as a ratio of end-diastolic measurements(21,23). However, in this study we prospectively decided to measure the simplest possible parameter - lateral MAPSE - which has been shown to have prognostic significance in the echo and CMR literature. We believe that simple rapid techniques are more likely to be utilized in busy clinical laboratories. Moreover, our results stand on their own and clearly demonstrate that this simple lateral MAPSE measurement is an important independent predictor of death, incremental to standard clinical and imaging variables. We did not prospectively look at septal MAPSE in this study because our earlier work suggested that lateral MAPSE was more strongly associated with major adverse events in a small single center study of all comers undergoing CMR (12).

Conclusions

In this large multicenter study, lateral MAPSE measured during routine cine CMR is a significant independent predictor of mortality in patients with hypertension and a clinical indication for CMR – incremental to common clinical and imaging risk factors. Each 1mm reduction in lateral MAPSE was associated with a 40.2% increased risk-of-death after adjustment for clinical and imaging risk factors. Lateral MAPSE remained significantly associated with death even after adjustment for feature tracking GLS. A major strength of these findings is that they were made in a big multicenter group of hypertensive patients with a large number of hard events (n=235), which greatly increases the robustness of our results. Importantly, lateral MAPSE remained an independent predictor of death even in the subgroup of patients with preserved ejection fraction, potentially allowing early identification of patients at highest risk.

Our findings highlight the role of long-axis function in individuals with hypertension and suggest that consideration may be given to measurement of lateral MAPSE in these patients. Future studies are needed to explore the role of CMR derived lateral MAPSE in clinical decision making for individuals with hypertension.

CLINICAL PERSPECTIVES.

Competency in Medical Knowledge: In this multicenter study, lateral MAPSE measured during routine cine CMR is a significant independent predictor of mortality in patients with hypertension and a clinical indication for CMR – incremental to common clinical and imaging risk factors.

Translational Outlook: How this information will affect clinical care requires further investigation and future studies are warranted to explore the role of CMR derived lateral MAPSE in clinical decision making.

Abbreviations:

- CMR

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance

- EF

Ejection Fraction

- LGE

Late Gadolinium Enhancement

- LV

Left Ventricle

- MAPSE

mitral annular plane systolic excursion

- NRI

Net Reclassification Improvement

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. The New England journal of medicine 1990;322:1561–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marwick TH, Gillebert TC, Aurigemma G et al. Recommendations on the use of echocardiography in adult hypertension: a report from the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) and the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE)dagger. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging 2015;16:577–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henein MY, Gibson DG. Long axis function in disease. Heart 1999;81:229–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henein MY, Gibson DG. Normal long axis function. Heart 1999;81:111–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlsson M, Ugander M, Mosen H, Buhre T, Arheden H. Atrioventricular plane displacement is the major contributor to left ventricular pumping in healthy adults, athletes, and patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology 2007;292:H1452–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ballo P, Barone D, Bocelli A, Motto A, Mondillo S. Left ventricular longitudinal systolic dysfunction is an independent marker of cardiovascular risk in patients with hypertension. American journal of hypertension 2008;21:1047–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narayanan A, Aurigemma GP, Chinali M, Hill JC, Meyer TE, Tighe DA. Cardiac mechanics in mild hypertensive heart disease: a speckle-strain imaging study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:382–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmon LC, Reichek N, Yeon SB et al. Intramural myocardial shortening in hypertensive left ventricular hypertrophy with normal pump function. Circulation 1994;89:122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saito M, Khan F, Stoklosa T, Iannaccone A, Negishi K, Marwick TH. Prognostic Implications of LV Strain Risk Score in Asymptomatic Patients With Hypertensive Heart Disease. JACC Cardiovascular imaging 2016;9:911–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao HB, Kaleem S, McCarthy C, Rosen SD. Abnormal regional left ventricular mechanics in treated hypertensive patients with ‘normal left ventricular function’. International journal of cardiology 2006;112:316–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romano S, Judd RM, Kim RJ et al. Left Ventricular Long-Axis Function Assessed with Cardiac Cine MR Imaging Is an Independent Predictor of All-Cause Mortality in Patients with Reduced Ejection Fraction: A Multicenter Study. Radiology 2018;286:452–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rangarajan V, Chacko SJ, Romano S et al. Left ventricular long axis function assessed during cine-cardiovascular magnetic resonance is an independent predictor of adverse cardiac events. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2016;18:35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu E, Judd RM, Vargas JD, Klocke FJ, Bonow RO, Kim RJ. Visualisation of presence, location, and transmural extent of healed Q-wave and non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Lancet 2001;357:21–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim HW, Farzaneh-Far A, Kim RJ. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in patients with myocardial infarction: current and emerging applications. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;55:1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abbasi SA, Ertel A, Shah RV et al. Impact of cardiovascular magnetic resonance on management and clinical decision-making in heart failure patients. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2013;15:89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim RJ, Wu E, Rafael A et al. The use of contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to identify reversible myocardial dysfunction. The New England journal of medicine 2000;343:1445–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Romano S, Judd RM, Kim RJ et al. Association of Feature-Tracking Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging Left Ventricular Global Longitudinal Strain With All-Cause Mortality in Patients With Reduced Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction. Circulation 2017;135:2313–2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Romano S, Judd RM, Kim RJ et al. Feature-Tracking Global Longitudinal Strain Predicts Death in a Multicenter Population of Patients with Ischemic and Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathy Incremental to Ejection Fraction and Late Gadolinium Enhancement. JACC Cardiovascular imaging 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.10.024. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pencina MJ, D’Agostino RB Sr., D’Agostino RB Jr., Vasan RS. Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Statistics in medicine 2008;27:157–72; discussion 207–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu K, Liu D, Herrmann S et al. Clinical implication of mitral annular plane systolic excursion for patients with cardiovascular disease. European heart journal cardiovascular Imaging 2013;14:205–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riffel JH, Keller MG, Rost F et al. Left ventricular long axis strain: a new prognosticator in non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy? Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2016;18:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arenja N, Riffel JH, Fritz T et al. Diagnostic and Prognostic Value of Long-Axis Strain and Myocardial Contraction Fraction Using Standard Cardiovascular MR Imaging in Patients with Nonischemic Dilated Cardiomyopathies. Radiology 2017:161184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gjesdal O, Yoneyama K, Mewton N et al. Reduced long axis strain is associated with heart failure and cardiovascular events in the multi-ethnic study of Atherosclerosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2016;44:178–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ballo P, Quatrini I, Giacomin E, Motto A, Mondillo S. Circumferential versus longitudinal systolic function in patients with hypertension: a nonlinear relation. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography : official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography 2007;20:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chilian WM. Microvascular pressures and resistances in the left ventricular subepicardium and subendocardium. Circulation research 1991;69:561–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishizu T, Seo Y, Kameda Y et al. Left ventricular strain and transmural distribution of structural remodeling in hypertensive heart disease. Hypertension 2014;63:500–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalam K, Otahal P, Marwick TH. Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction. Heart 2014;100:1673–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levack MM, Jassar AS, Shang EK et al. Three-dimensional echocardiographic analysis of mitral annular dynamics: implication for annuloplasty selection. Circulation 2012;126:S183–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maceira AM, Mohiaddin RH. Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in systemic hypertension. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2012;14:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rudolph A, Abdel-Aty H, Bohl S et al. Noninvasive detection of fibrosis applying contrast-enhanced cardiac magnetic resonance in different forms of left ventricular hypertrophy relation to remodeling. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009;53:284–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Germans T, Nijveldt R, Brouwer WP et al. The role of cardiac magnetic resonance imaging in differentiating the underlying causes of left ventricular hypertrophy. Netherlands heart journal : monthly journal of the Netherlands Society of Cardiology and the Netherlands Heart Foundation 2010;18:135–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kwong RY, Farzaneh-Far A. Measuring myocardial scar by CMR. JACC Cardiovascular imaging 2011;4:157–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krittayaphong R, Boonyasirinant T, Chaithiraphan V et al. Prognostic value of late gadolinium enhancement in hypertensive patients with known or suspected coronary artery disease. The international journal of cardiovascular imaging 2010;26 Suppl 1:123–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chan RH, Maron BJ, Olivotto I et al. Prognostic value of quantitative contrast-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance for the evaluation of sudden death risk in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2014;130:484–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parsai C, O’Hanlon R, Prasad SK, Mohiaddin RH. Diagnostic and prognostic value of cardiovascular magnetic resonance in non-ischaemic cardiomyopathies. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance 2012;14:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Andersen K, Hennersdorf M, Cohnen M, Blondin D, Modder U, Poll LW. Myocardial delayed contrast enhancement in patients with arterial hypertension: initial results of cardiac MRI. Eur J Radiol 2009;71:75–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rodrigues JC, Amadu AM, Dastidar AG et al. Comprehensive characterisation of hypertensive heart disease left ventricular phenotypes. Heart 2016;102:1671–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stanton T, Leano R, Marwick TH. Prediction of all-cause mortality from global longitudinal speckle strain: comparison with ejection fraction and wall motion scoring. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2009;2:356–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Klem I, Shah DJ, White RD et al. Prognostic value of routine cardiac magnetic resonance assessment of left ventricular ejection fraction and myocardial damage: an international, multicenter study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 2011;4:610–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lauer MS, Blackstone EH, Young JB, Topol EJ. Cause of death in clinical research: time for a reassessment? J Am Coll Cardiol 1999;34:618–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]