Abstract

Plasma xanthine oxidase (XO) activity was defined as a source

of enhanced vascular superoxide (O ) and

hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production in both

sickle cell disease (SCD) patients and knockout-transgenic SCD mice.

There was a significant increase in the plasma XO activity of SCD

patients that was similarly reflected in the SCD mouse model. Western

blot and enzymatic analysis of liver tissue from SCD mice revealed

decreased XO content. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver tissue of

knockout-transgenic SCD mice indicated extensive hepatocellular injury

that was accompanied by increased plasma content of the liver enzyme

alanine aminotransferase. Immunocytochemical and enzymatic analysis of

XO in thoracic aorta and liver tissue of SCD mice showed increased

vessel wall and decreased liver XO, with XO concentrated on and in

vascular luminal cells. Steady-state rates of vascular

O

) and

hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production in both

sickle cell disease (SCD) patients and knockout-transgenic SCD mice.

There was a significant increase in the plasma XO activity of SCD

patients that was similarly reflected in the SCD mouse model. Western

blot and enzymatic analysis of liver tissue from SCD mice revealed

decreased XO content. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver tissue of

knockout-transgenic SCD mice indicated extensive hepatocellular injury

that was accompanied by increased plasma content of the liver enzyme

alanine aminotransferase. Immunocytochemical and enzymatic analysis of

XO in thoracic aorta and liver tissue of SCD mice showed increased

vessel wall and decreased liver XO, with XO concentrated on and in

vascular luminal cells. Steady-state rates of vascular

O production, as indicated by coelenterazine

chemiluminescence, were significantly increased, and nitric oxide

(⋅NO)-dependent vasorelaxation of aortic ring segments was

severely impaired in SCD mice, implying oxidative inactivation of

⋅NO. Pretreatment of aortic vessels with the superoxide

dismutase mimetic manganese

5,10,15,20-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin

markedly decreased O

production, as indicated by coelenterazine

chemiluminescence, were significantly increased, and nitric oxide

(⋅NO)-dependent vasorelaxation of aortic ring segments was

severely impaired in SCD mice, implying oxidative inactivation of

⋅NO. Pretreatment of aortic vessels with the superoxide

dismutase mimetic manganese

5,10,15,20-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)porphyrin

markedly decreased O levels and significantly

restored acetylcholine-dependent relaxation, whereas catalase had no

effect. These data reveal that episodes of intrahepatic

hypoxia-reoxygenation associated with SCD can induce the release of XO

into the circulation from the liver. This circulating XO can then bind

avidly to vessel luminal cells and impair vascular function by creating

an oxidative milieu and catalytically consuming ⋅NO via

O

levels and significantly

restored acetylcholine-dependent relaxation, whereas catalase had no

effect. These data reveal that episodes of intrahepatic

hypoxia-reoxygenation associated with SCD can induce the release of XO

into the circulation from the liver. This circulating XO can then bind

avidly to vessel luminal cells and impair vascular function by creating

an oxidative milieu and catalytically consuming ⋅NO via

O -dependent mechanisms.

-dependent mechanisms.

The β-globin mutation in sickle cell disease (SCD) is manifested by a glutamic acid to valine substitution and, ultimately, vascular dysfunction. Upon deoxygenation, intracellular polymerization of HbS occurs, and sickle erythrocytes acquire altered rheological properties (1). Even though the capillary transit time of red cells is brief in comparison to the kinetics of HbS polymerization, increased blood cell interactions with vascular endothelium will occur as a consequence of altered red cell membrane properties and increased vessel wall adhesiveness. Incompletely described signaling mechanisms also induce an inflammatory-like activation state in vascular endothelium indicated by elevated endothelial expression of Fc receptor and the integrins ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and P-selectin (2–5). There are also increased plasma levels of leukocytes (6), “activated” circulating endothelial cells, proinflammatory cytokines, platelet-activating factor, C-reactive protein, and angiogenic stimuli (7, 8).

The mechanisms underlying regional blood flow deprivation during sickle cell crises, as well as the associated pain with consequent tissue injury, remain poorly understood. If tissue ischemia in SCD patients resulted solely from Hb polymerization and red cell deformation, occlusion of small blood vessels such as terminal arterioles would predominate. Whereas this phenomenon certainly contributes to tissue injury in the liver, lungs, kidney, and spleen, it is not sufficient to explain large vessel vasculopathies. For example, stroke in SCD patients occurs in large and medium-sized arteries (internal carotid and middle cerebral arteries; refs. 9 and 10). Importantly, the quantity or proportion of sickled or dense red cells in the circulation does not correlate with the incidence of painful episodes or other manifestations of vascular occlusion (11, 12). This implies that much of the morbidity and mortality of SCD is caused by alterations in vascular function that occur secondary to red cell sickling, rather than as a consequence of direct vaso-occlusive actions of sickled red cells.

Multiple features of SCD strongly infer a pathogenic role for impaired

⋅NO-dependent vascular regulation. For example, vascular

production of ⋅NO seems to be chronically activated to maintain

vasodilation, as indicated by low baseline blood pressure (13) and

decreased plasma arginine levels (14). Also, decreased pressor

responses to angiotensin II (15), renal hyperfiltration (16), a

tendency for priapism (17), and elevated plasma nitrite and nitrate

(NO + NO

+ NO ) levels occur in SCD

(18). During vaso-occlusive crisis, an increased metabolic demand for

arginine and an inverse relationship between subjective pain scores and

plasma NO

) levels occur in SCD

(18). During vaso-occlusive crisis, an increased metabolic demand for

arginine and an inverse relationship between subjective pain scores and

plasma NO + NO

+ NO levels has been

reported (18, 19). Finally, therapeutic benefit has been observed in

SCD patients receiving inhaled ⋅NO and hydroxyurea, a drug

frequently used to treat SCD that not only induces fetal Hb levels in

SCD patients but also is metabolized to ⋅NO (20, 21).

levels has been

reported (18, 19). Finally, therapeutic benefit has been observed in

SCD patients receiving inhaled ⋅NO and hydroxyurea, a drug

frequently used to treat SCD that not only induces fetal Hb levels in

SCD patients but also is metabolized to ⋅NO (20, 21).

Another hallmark of SCD, increased tissue rates of production of

reactive oxygen species, may also contribute to impaired NO signaling.

Compared with HbA red cells, HbS red cells have been reported to

generate ≈2-fold greater extents of O ,

H2O2, hydroxyl radical

(⋅OH), and lipid oxidation products (LOOH, LOO⋅) (22,

23). Also, decompartmentalization of redox-active transition metals

such as iron has been observed in HbS red cells (23). Finally, mice

expressing human βS-hemoglobin displayed

indices of increased lipid oxidation and aromatic hydroxylation

reactions and, upon exposure to hypoxia, had ≈10% increase in the

conversion of liver and kidney xanthine oxidoreductase to the

O

,

H2O2, hydroxyl radical

(⋅OH), and lipid oxidation products (LOOH, LOO⋅) (22,

23). Also, decompartmentalization of redox-active transition metals

such as iron has been observed in HbS red cells (23). Finally, mice

expressing human βS-hemoglobin displayed

indices of increased lipid oxidation and aromatic hydroxylation

reactions and, upon exposure to hypoxia, had ≈10% increase in the

conversion of liver and kidney xanthine oxidoreductase to the

O and

H2O2-producing oxidase form

(24). Appreciating that ⋅NO reacts at diffusion-limited rates

with O

and

H2O2-producing oxidase form

(24). Appreciating that ⋅NO reacts at diffusion-limited rates

with O and lipid peroxyl radicals

(LOO⋅) to produce secondary products such as peroxynitrite

(ONOO−) and nitrated lipids

[LNO2, L(O)NO2] (25–27),

it is proposed that the impaired vascular function and inflammatory

activation of SCD vessels could be a consequence of oxygen

radical-dependent consumption of ⋅NO and production of secondary

reactive species (e.g.,

H2O2 or

ONOO−) that can also impair vascular function.

In support of this precept, a combination of clinical and

knockout-transgenic SCD mouse studies are reported herein that show

increased rates of xanthine oxidase (XO)-dependent vessel wall

production of ⋅NO-inactivating O

and lipid peroxyl radicals

(LOO⋅) to produce secondary products such as peroxynitrite

(ONOO−) and nitrated lipids

[LNO2, L(O)NO2] (25–27),

it is proposed that the impaired vascular function and inflammatory

activation of SCD vessels could be a consequence of oxygen

radical-dependent consumption of ⋅NO and production of secondary

reactive species (e.g.,

H2O2 or

ONOO−) that can also impair vascular function.

In support of this precept, a combination of clinical and

knockout-transgenic SCD mouse studies are reported herein that show

increased rates of xanthine oxidase (XO)-dependent vessel wall

production of ⋅NO-inactivating O in

SCD. The increased rates of vessel wall oxidant production caused

impairment of ⋅NO-dependent vascular relaxation in SCD mouse

vessels that were corrected by a catalytic metalloporphyrin

superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic. Finally, multiple lines of evidence

showed that the vessel wall, not red cells, was the primary source of

⋅NO-consuming free radical species in SCD.

in

SCD. The increased rates of vessel wall oxidant production caused

impairment of ⋅NO-dependent vascular relaxation in SCD mouse

vessels that were corrected by a catalytic metalloporphyrin

superoxide dismutase (SOD) mimetic. Finally, multiple lines of evidence

showed that the vessel wall, not red cells, was the primary source of

⋅NO-consuming free radical species in SCD.

Materials and Methods

Erythrocyte Superoxide, Hydrogen Peroxide, and Lipid Hydroperoxide Production.

Blood was collected from healthy HbA adult volunteers and

homozygous HbS patients in anticoagulated (EDTA) vacutainers as

approved by the Institutional Review Board for Human Use at the

University of Alabama at Birmingham. All individuals were evaluated for

cytochrome b5 reductase and

glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase activity, and none were reported

deficient. After centrifugation, plasma and buffy coat was discarded,

and cells were washed and filtered through a cellulose column (Sigma,

type 50 and α cellulose) to remove neutrophils and platelets. Packed

RBCs were diluted to a hematocrit of 2.5% (vol/vol) hemoglobin

concentration determined with Drabkin's reagent at 540 nm (28), and

rates of O release over 2 h were

quantified spectrophotometrically by CuZn SOD-inhibitable (100 units

ml−1, equivalent to ≈33 μg

ml−1 SOD) reduction of cytochrome c

(50 μM) at 550 nm (ɛM = 21

mM−1⋅cm−1). In some

experiments, O

release over 2 h were

quantified spectrophotometrically by CuZn SOD-inhibitable (100 units

ml−1, equivalent to ≈33 μg

ml−1 SOD) reduction of cytochrome c

(50 μM) at 550 nm (ɛM = 21

mM−1⋅cm−1). In some

experiments, O release was measured in cells

pretreated with 2,3-dimethoxy-1-napthoquinone (DMNQ; Oxis, 100 μM),

3hydroxy-1,2-dimethyl-4-pyridone (Aldrich, 0.5 mM), and

4,4-diisothiocyano-2,2 disulfonic acid stilbene (Sigma, 200 μM).

Possible Hb interference in determination of rates of cytochrome

c reduction was evaluated by performing a singular value

decomposition analysis (Matlab, Mathworks, Natick, MA). Intracellular

H2O2 concentrations were

calculated from aminotriazole (AT)-mediated inactivation of catalase

activity as described (29). Red cells were incubated with 10 mM AT at

37°C, and intracellular catalase activity was determined at 1-h

intervals for 4 h. Catalase activity was measured

spectrophotometrically based on the consumption of 10 mM

H2O2 at 240 nm

(ɛM = 43.6

M−1⋅cm−1). For

determining the extent of membrane lipid oxidation, packed RBCs were

lysed in hypotonic phosphate buffer (20 mosM, pH 7.4, 4°C),

centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 20 min, and the

supernatant was discarded. Membrane ghosts were washed eight times to

minimize Hb contamination and stored at −20°C. For use as a stimulus

of lipid oxidation, ONOO− was synthesized as

described (25), and its concentration was determined

spectrophotometrically at 302 nm (ɛM = 1670

M−1⋅cm−1). Lipid

hydroperoxide (LOOH) content was measured via N-benzoyl

leucomethylene blue oxidation and quantitated against a

t-butyl hydroperoxide standard. Protein concentrations were

measured at 595 nm by a modified Bradford assay by using

Coomassie Plus reagent with BSA as a standard.

release was measured in cells

pretreated with 2,3-dimethoxy-1-napthoquinone (DMNQ; Oxis, 100 μM),

3hydroxy-1,2-dimethyl-4-pyridone (Aldrich, 0.5 mM), and

4,4-diisothiocyano-2,2 disulfonic acid stilbene (Sigma, 200 μM).

Possible Hb interference in determination of rates of cytochrome

c reduction was evaluated by performing a singular value

decomposition analysis (Matlab, Mathworks, Natick, MA). Intracellular

H2O2 concentrations were

calculated from aminotriazole (AT)-mediated inactivation of catalase

activity as described (29). Red cells were incubated with 10 mM AT at

37°C, and intracellular catalase activity was determined at 1-h

intervals for 4 h. Catalase activity was measured

spectrophotometrically based on the consumption of 10 mM

H2O2 at 240 nm

(ɛM = 43.6

M−1⋅cm−1). For

determining the extent of membrane lipid oxidation, packed RBCs were

lysed in hypotonic phosphate buffer (20 mosM, pH 7.4, 4°C),

centrifuged at 30,000 × g for 20 min, and the

supernatant was discarded. Membrane ghosts were washed eight times to

minimize Hb contamination and stored at −20°C. For use as a stimulus

of lipid oxidation, ONOO− was synthesized as

described (25), and its concentration was determined

spectrophotometrically at 302 nm (ɛM = 1670

M−1⋅cm−1). Lipid

hydroperoxide (LOOH) content was measured via N-benzoyl

leucomethylene blue oxidation and quantitated against a

t-butyl hydroperoxide standard. Protein concentrations were

measured at 595 nm by a modified Bradford assay by using

Coomassie Plus reagent with BSA as a standard.

NO Consumption.

Anaerobic solutions of 1.9 mM ⋅NO were prepared by equilibrating ⋅NO gas (Matheson) in argon-saturated deionized water. Contaminating nitrogen dioxide (NO2) or nitrous oxide (N2O) was removed by first passing the NO gas through 5 M NaOH. NO (2.5–15 μM) was added to diluted RBCs (Hb = 3 × 10−5 g/ml−1; 0.5 μM), and rates of ⋅NO consumption were measured electrochemically (Iso-NO, WPI Instruments, Waltham, MA) under normoxic and hypoxic (20–40 mmHg O2 tension) conditions in a closed, thermally regulated (37°C) and stirred polarographic cell. Hypoxic conditions were established in the reaction chamber by partially equilibrating buffers with nitrogen gas and quantified by using a Clark model YSI 5300 oxygen electrode (Yellow Springs Instruments).

XO and Alanine Aminotransferase Analysis.

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. Plasma and tissue XO activity was measured by reversed-phase HPLC with electrochemical detection of uric acid as described (30). For biochemical analysis of liver tissue, isolated livers were weighed and homogenized in ice-cold homogenizing buffer (50 mM K2HPO4/80 μM leupeptin/2.1 mM Pefabloc SC/1 mM PMSF/1 μg ml−1 aprotinin, pH 7.4). Homogenates were centrifuged (40,000 × g, 30 min, 4°C), and supernatants were stored at −80°C. Plasma alanine aminotransferase activity was measured on an automated spectrofluorometer (Cobas-Fara II, Roche Diagnostic Systems). A rabbit polyclonal antibody against recombinant human xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) fragment was used (1:1,000 dilution) for immunoblot analysis (32). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:10,000) was used as a secondary antibody, and immunoreactive proteins were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico Substrate, Pierce).

Fluorescence Microscopy.

Frozen aortic sections and paraffin-embedded liver sections from C57BL/6J or knockout-transgenic SCD mouse were processed for immunofluorescence. Primary antibody incubations were carried out for 60 min at 25°C by using a rabbit polyclonal antibody against XO (1:50). The secondary antibody was Alexa-594 conjugated goat anti-rabbit (1:100, Molecular Probes). For control studies, the primary anti-XO was preabsorbed with excess (1 unit ml−1) bovine XO. Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst 33258 (20 μg ml−1, Sigma). Images were acquired through a Leitz Orthoplan microscope and analyzed with ip lab spectrum software (Scanalytics, Billerica, MA).

Vessel Relaxation and Superoxide Production.

Isometric tension was measured in aortic segments from mice as

described (33). Aortic segments were exposed in some cases to various

mediators and inhibitors for 1 h, submaximally contracted with

phenylephrine (10−8–10−7

M), and acetylcholine (ACh; 1 × 10−9 to

3 × 10−6 M) was added in a cumulative

manner to induce relaxation. Vessel O production was monitored in aortic segments by coelenterazine-enhanced

chemiluminescence (34) by using an automated microplate luminescence

reader (Lumistar Galaxy, BMG Lab Technologies). Previous studies have

shown coelenterazine to reflect both tissue O

production was monitored in aortic segments by coelenterazine-enhanced

chemiluminescence (34) by using an automated microplate luminescence

reader (Lumistar Galaxy, BMG Lab Technologies). Previous studies have

shown coelenterazine to reflect both tissue O and ONOO− production, differentiable by

selective use of SOD and NO synthase inhibitors (34). Isolated vessels

were equilibrated in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) for 30 min

at 37°C, and coelenterazine (10 μM, Calbiochem) was added. In some

experiments, O

and ONOO− production, differentiable by

selective use of SOD and NO synthase inhibitors (34). Isolated vessels

were equilibrated in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS) for 30 min

at 37°C, and coelenterazine (10 μM, Calbiochem) was added. In some

experiments, O was measured in vessels that

were pretreated with xanthine (50 μM, Sigma), allopurinol (100 μM,

Sigma), CuZn SOD (30 units ml−1, Oxis),

manganese

5,10,15,20-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)-porphyrin

(MnTE-2-PyP; 50 μM), catalase (20 units ml−1,

Worthington), BOF-4272

[sodium-8-(3-methoxy-4-phenylsulfinylphenyl)pyrazolol(1,5α)-1,3,5-triazine-4-olate-monohydrate]

a gift from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Tokushima, Japan (25 μM),

and DMNQ (100 μM). The assay system was calibrated by using 0.1–0.5

mU XO plus 50 μM xanthine, generating known rates of

O

was measured in vessels that

were pretreated with xanthine (50 μM, Sigma), allopurinol (100 μM,

Sigma), CuZn SOD (30 units ml−1, Oxis),

manganese

5,10,15,20-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)-porphyrin

(MnTE-2-PyP; 50 μM), catalase (20 units ml−1,

Worthington), BOF-4272

[sodium-8-(3-methoxy-4-phenylsulfinylphenyl)pyrazolol(1,5α)-1,3,5-triazine-4-olate-monohydrate]

a gift from Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Tokushima, Japan (25 μM),

and DMNQ (100 μM). The assay system was calibrated by using 0.1–0.5

mU XO plus 50 μM xanthine, generating known rates of

O -dependent cytochrome c reduction.

-dependent cytochrome c reduction.

Results

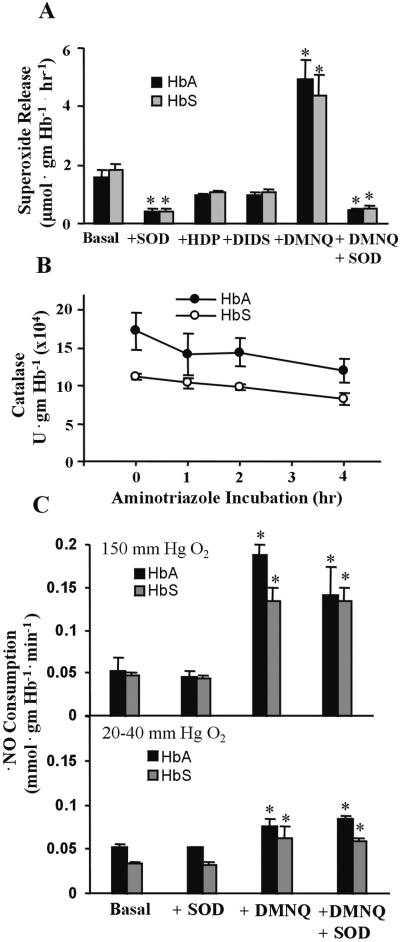

Red Cell Production of Reactive Oxygen Species.

Endogenous rates of O release under

normoxic (150 mmHg O2, pH 7.4) conditions were

not significantly different in human HbA (1.60 ± 0.25 μmol

gmHb−1⋅h−1) vs.

homozygous HbS (1.84 ± 0.2 μmol

gmHb−1⋅h−1) red

cells (Fig. 1A). The mean Hb

content of HbA and HbS red cell preparations was 0.36 and 0.39 gmHb

ml−1 packed cells, respectively. Potential

interference of lysed cell-derived Hb in the analysis of cytochrome

c reduction was ruled out by singular value decomposition

analysis, which separated the spectral components of the reaction

system and identified the elements contributing to the recorded

absorbance. The singular value decomposition analysis of red

cell-dependent cytochrome c reduction showed a

time-dependent increase at 550 nm in the absence of SOD, with only one

significant spectral component, reduced cytochrome c (not

shown). To elucidate the nature of O

release under

normoxic (150 mmHg O2, pH 7.4) conditions were

not significantly different in human HbA (1.60 ± 0.25 μmol

gmHb−1⋅h−1) vs.

homozygous HbS (1.84 ± 0.2 μmol

gmHb−1⋅h−1) red

cells (Fig. 1A). The mean Hb

content of HbA and HbS red cell preparations was 0.36 and 0.39 gmHb

ml−1 packed cells, respectively. Potential

interference of lysed cell-derived Hb in the analysis of cytochrome

c reduction was ruled out by singular value decomposition

analysis, which separated the spectral components of the reaction

system and identified the elements contributing to the recorded

absorbance. The singular value decomposition analysis of red

cell-dependent cytochrome c reduction showed a

time-dependent increase at 550 nm in the absence of SOD, with only one

significant spectral component, reduced cytochrome c (not

shown). To elucidate the nature of O release

and verify the specificity of the assay system, DMNQ (100 μM) was

added to stimulate red cell O

release

and verify the specificity of the assay system, DMNQ (100 μM) was

added to stimulate red cell O production.

Preincubation of cells with the metal chelator

3-hydroxy-1,2-dimethyl-4-pyridone (0.5 mM) induced ≈36% decrease in

O

production.

Preincubation of cells with the metal chelator

3-hydroxy-1,2-dimethyl-4-pyridone (0.5 mM) induced ≈36% decrease in

O , suggesting that cellular Fe-dependent

reactions partially contributed to cell O

, suggesting that cellular Fe-dependent

reactions partially contributed to cell O production. When cells were pretreated with a stilbene sulfonate

chloride-bicarbonate exchange protein inhibitor (4,4-diisothiocyano-2,2

disulfonic acid stilbene, 200 μM), both HbA and HbS red cells showed

≈35% decrease in rates of cytochrome c reduction,

indicating that some extracellular O

production. When cells were pretreated with a stilbene sulfonate

chloride-bicarbonate exchange protein inhibitor (4,4-diisothiocyano-2,2

disulfonic acid stilbene, 200 μM), both HbA and HbS red cells showed

≈35% decrease in rates of cytochrome c reduction,

indicating that some extracellular O was

released through anion channels.

was

released through anion channels.

Figure 1.

Red cell production of reactive oxygen species. (A) Rates of superoxide release by HbA and HbS red cells. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 3–9). Statistical analysis was by two-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. *, P < 0.05. (B) Aminotriazole-mediated catalase inactivation by HbA and HbS red cells. Values at each time point represent mean ± SD with n = 5. (C) Rates of HbA and HbS red cell NO consumption. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 4–14). Statistical analysis was by two-way ANOVA with the Tukey post hoc test. *, P < 0.05 compared with basal.

The similar slopes of the time course of aminotriazole-dependent red

cell catalase inactivation in HbA and HbS red cells revealed that

steady-state H2O2 levels

were not significantly different, with calculated

H2O2 concentrations of

3.11 ± 2.61 pM and 4.9 ± 2.25 pM, respectively, at 150 mmHg

O2, pH 7.4 (Fig. 1B). This occurred

despite the 36% lower catalase specific activity in HbS red cells,

suggesting other compensatory mechanisms for intracellular

H2O2 scavenging, e.g.,

glutathione peroxidase. Accepting that ⋅NO reacts at almost

diffusion-limited rates with O (25), the

relative rates of red cell ⋅NO consumption was determined as

probe for differences in intracellular and extracellular

O

(25), the

relative rates of red cell ⋅NO consumption was determined as

probe for differences in intracellular and extracellular

O production by HbA and HbS red cells. NO

consumption, measured during both normoxic (150 mmHg

O2) and sickling-inducing hypoxic (20–40 mmHg

O2) conditions, was not significantly different

in HbA vs. HbS red cells, with normoxic values of 0.053 ± 0.016

and 0.047 ± 0.003 mmol

gmHb−1⋅min−1,

respectively (Fig. 1C). Addition of extracellular CuZn SOD

(100 units ml−1) did not impact the rate of

⋅NO consumption, whereas stimulation of cell

O

production by HbA and HbS red cells. NO

consumption, measured during both normoxic (150 mmHg

O2) and sickling-inducing hypoxic (20–40 mmHg

O2) conditions, was not significantly different

in HbA vs. HbS red cells, with normoxic values of 0.053 ± 0.016

and 0.047 ± 0.003 mmol

gmHb−1⋅min−1,

respectively (Fig. 1C). Addition of extracellular CuZn SOD

(100 units ml−1) did not impact the rate of

⋅NO consumption, whereas stimulation of cell

O generation by DMNQ (100 μM) added as a

positive control significantly increased rates of red cell ⋅NO

consumption. The presence of endogenous LOOH was

undetectable in both HbA and HbS RBC membranes. When membrane oxidation

was stimulated by the addition of OONO−, HbS red

cell membranes showed greater tendency to undergo lipid peroxidation

(not shown).

generation by DMNQ (100 μM) added as a

positive control significantly increased rates of red cell ⋅NO

consumption. The presence of endogenous LOOH was

undetectable in both HbA and HbS RBC membranes. When membrane oxidation

was stimulated by the addition of OONO−, HbS red

cell membranes showed greater tendency to undergo lipid peroxidation

(not shown).

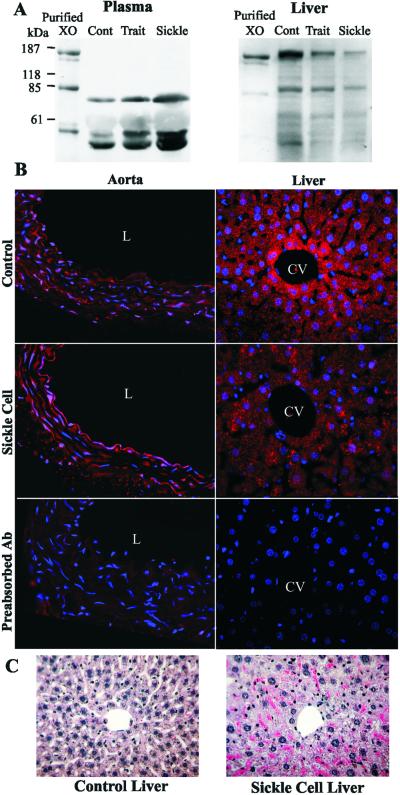

Plasma XO and Alanine Aminotransferase Activities.

The catalytic activity of XO was significantly increased in the plasma of SCD patients vs. controls (Table 1). This also occurred in the plasma of a knockout-transgenic mouse model of SCD that synthesizes exclusively human Hb in the murine RBCs (31). The observed increase in plasma XO activity in the knockout-transgenic SCD mouse was accompanied by a decrease in liver XO activity and an increase in plasma alanine aminotransferase activity (Table 1). Western blot analysis of plasma and liver XOR revealed increased plasma and decreased liver XOR protein content in knockout-transgenic SCD mice compared with control or knockout-transgenic sickle cell trait mice, which synthesize both human βS and βA (Fig. 2A). XOR, which is rapidly converted to the oxidase form (XO) in plasma, revealed immunoreactive 20-kDa, 40-kDa, and 85-kDa proteolytic fragments upon Western blot analysis. Knockout-transgenic sickle cell trait (heterozygous for HbS) mice were also not significantly different from control C57BL/6J mice in plasma and liver XO and plasma alanine aminotransferase activities (not shown). Immunocytochemical localization of XO in aorta and liver (Fig. 2B) of SCD mice showed increased vessel wall and decreased liver XO immunoreactivity, with XO concentrated on and in vascular luminal cells. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver of knockout-transgenic SCD mice revealed extensive hepatocellular injury associated with pericentral necrosis. Sickled erythrocytes were also observed in intrahepatic sinusoids (Fig. 2C) (31).

Table 1.

Activity of XO and ALT in sickle cell disease

| Measurement | Enzyme

activity

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Control | SCD* | |

| Human | ||

| Plasma XO (μU/ml) | 0.89 ± 0.3 (15) | 3.30 ± 0.9 (18) |

| Mouse | ||

| Plasma XO (mU/ml) | 2.2 ± 0.26 (13) | 5.6 ± 1.5 (15) |

| ALT (mU/ml) | 24.2 ± 2.3 (10) | 270.5 ± 24.5 (12) |

| Liver XO (mU/g tissue) | 53.9 ± 7.8 (6) | 18.6 ± 4.4 (6) |

| Aortic XO (mU/mg protein) | 0.29 ± 0.01 (3) | 0.46 ± 0.03 (4) |

, P < 0.05 from control. n for each measurement is italicized in parentheses.

Figure 2.

Immunocytochemical analysis of XOR in C57BL/6J control and sickle cell mouse tissues. (A) Western blot analysis of plasma and liver XO in SCD mice. (B) Descending thoracic aortic segments from knockout-transgenic SC mice display intense immunofluorescent staining for XO (red) that is associated with the endothelium and, to a lesser extent, smooth muscle cells (L, lumen). Liver sections from SC mice show decreased XOR staining in the pericentral hepatocytes when compared with controls (CV, central vein). Nuclei were counterstained with Hoechst in all experiments. (C) Hematoxylin and eosin staining of liver sections from control and sickle cell mouse tissues.

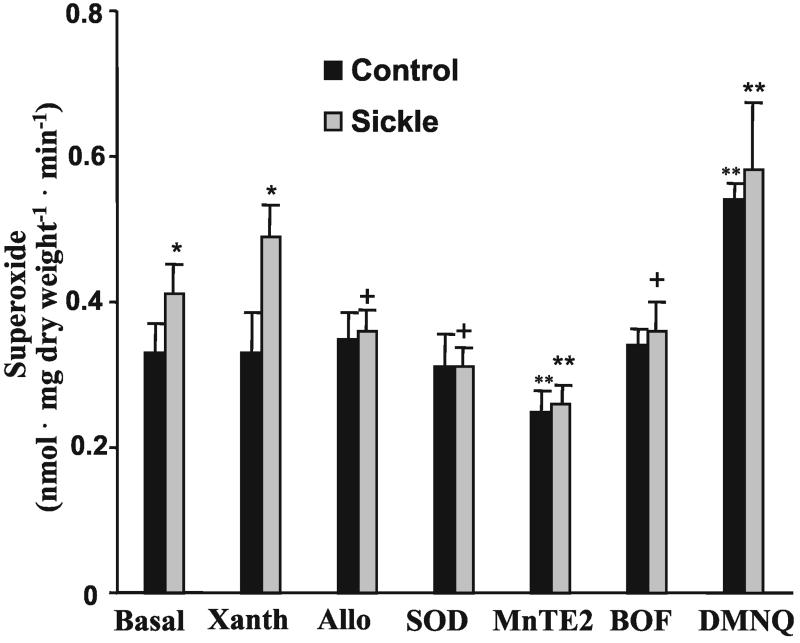

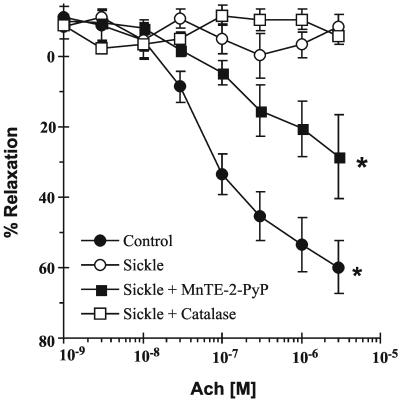

Superoxide Production and Endothelial-Dependent Relaxation of Vessels.

The catalytic activity of XO was significantly increased in the aorta

of SCD mice (Table 1) with a parallel increase in XOR protein observed

by Western blot analysis as well (not shown). Basal rates of

O production were significantly increased in

the aorta of SCD mice vs. controls, with rates of 0.41 ± 0.04 and

0.33 ± 0.04 nmol⋅mg dry

weight−1⋅min−1,

respectively (Fig. 3). In SCD, but not

wild-type mouse vessels, rates of O

production were significantly increased in

the aorta of SCD mice vs. controls, with rates of 0.41 ± 0.04 and

0.33 ± 0.04 nmol⋅mg dry

weight−1⋅min−1,

respectively (Fig. 3). In SCD, but not

wild-type mouse vessels, rates of O production

were enhanced by addition of xanthine and returned to basal rates when

vessels were pretreated with CuZn SOD (30 units

ml−1), allopurinol (100 μM), or the XO

inhibitor BOF-4272 (25 μM). Pretreatment of aorta with the SOD

mimetic MnTE-2-PyP (50 μM) significantly decreased rates of

detectable O

production

were enhanced by addition of xanthine and returned to basal rates when

vessels were pretreated with CuZn SOD (30 units

ml−1), allopurinol (100 μM), or the XO

inhibitor BOF-4272 (25 μM). Pretreatment of aorta with the SOD

mimetic MnTE-2-PyP (50 μM) significantly decreased rates of

detectable O production, whereas DMNQ (100

μM) addition significantly enhanced rates of

O

production, whereas DMNQ (100

μM) addition significantly enhanced rates of

O production by both control and SCD mouse

vessels. NO-dependent vessel relaxation, elicited by ACh,

was severely impaired in SCD mice (Fig.

4). The ⋅NO-dependent stimulus of

smooth muscle cell guanylate cyclase activity, sodium nitroprusside

(100 nM), induced maximal vessel relaxation in SCD mouse vessels,

whereas addition of arginine (3 mM) had no effect (not shown).

Treatment of SCD mouse vessels with the SOD mimetic MnTE-2-PyP (10

μM) significantly restored ACh-dependent relaxation, whereas addition

of catalase had no effect (Fig. 4).

production by both control and SCD mouse

vessels. NO-dependent vessel relaxation, elicited by ACh,

was severely impaired in SCD mice (Fig.

4). The ⋅NO-dependent stimulus of

smooth muscle cell guanylate cyclase activity, sodium nitroprusside

(100 nM), induced maximal vessel relaxation in SCD mouse vessels,

whereas addition of arginine (3 mM) had no effect (not shown).

Treatment of SCD mouse vessels with the SOD mimetic MnTE-2-PyP (10

μM) significantly restored ACh-dependent relaxation, whereas addition

of catalase had no effect (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

Superoxide production by C57BL/6J control and sickle cell mouse vessels. Values represent mean ± SD (n = 4). Statistical analysis was by two-way ANOVA with the Duncan's post hoc test. *, P < 0.05 compared with control. +, P < 0.05 compared with xanthine-treated sickle cell vessels. **, P < 0.05 compared with control and all treated vessel groups.

Figure 4.

ACh-dependent vascular relaxation in C57BL/6J control and sickle cell mouse vessels. Values represent mean ± SEM (n = 4–8). All statistical analyses were by one-way ANOVA with Student–Newman Keuls pairwise multiple comparison. *, P < 0.05 compared with sickle cell mouse vessel response.

Discussion

Insight into the mechanisms underlying impaired vascular

function in SCD is important for guiding the design of more effective

therapies to limit vaso-occlusive crisis, acute chest syndrome, stroke,

and other circulatory manifestations of this hemoglobinopathy. In

contrast to previous reports (22, 23), there is not a significant

difference in rates of O and

H2O2 production and basal

levels of membrane LOOH content in HbA vs. HbS red cells (Fig. 1

A and B). Also, HbA vs. HbS red cells display

similar rates of ⋅NO consumption under both normoxic and

sickling-inducing hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1C). This rules

out the possibility that unique oxidative or free radical metabolic

properties of HbS red cells contribute to enhanced rates of vascular

⋅NO scavenging and in turn initiate pathogenic signal

transduction events in SCD vessels, due to suppression of the

anti-inflammatory properties of ⋅NO. Although the inherent

instability of sickle Hb and the possible impairment of tissue free

radical defense mechanisms in SCD may render red cells more susceptible

to oxidative damage (23, 35), a well-integrated network of oxidant

defense mechanisms evidently prevents HbS red cells from becoming

significant loci of reactive species production and oxygen

radical-dependent inactivation of vascular ⋅NO signaling.

and

H2O2 production and basal

levels of membrane LOOH content in HbA vs. HbS red cells (Fig. 1

A and B). Also, HbA vs. HbS red cells display

similar rates of ⋅NO consumption under both normoxic and

sickling-inducing hypoxic conditions (Fig. 1C). This rules

out the possibility that unique oxidative or free radical metabolic

properties of HbS red cells contribute to enhanced rates of vascular

⋅NO scavenging and in turn initiate pathogenic signal

transduction events in SCD vessels, due to suppression of the

anti-inflammatory properties of ⋅NO. Although the inherent

instability of sickle Hb and the possible impairment of tissue free

radical defense mechanisms in SCD may render red cells more susceptible

to oxidative damage (23, 35), a well-integrated network of oxidant

defense mechanisms evidently prevents HbS red cells from becoming

significant loci of reactive species production and oxygen

radical-dependent inactivation of vascular ⋅NO signaling.

The observation that XO activity is elevated in the plasma of SCD patients is recapitulated in the SCD mouse (Table 1), suggesting that this enzyme may serve as a significant source of reactive oxygen species production in SCD. There is only trace XO activity in the plasma and vascular endothelium of healthy humans (36, 37). During pathological conditions such as hepatocellular damage (38, 39), ischemia-reperfusion (40), atherosclerosis (41), adult respiratory distress syndrome (36), alcoholic liver disease (42), and now SCD, in which organs replete in XOR can release this proinflammatory enzyme into the circulation, plasma XO levels increase. This can lead to an enhancement of vascular oxidant production, often in tissue compartments having minimal defense against oxidative injury.

XOR is found mainly in the splanchnic system, where it exists

predominantly as a dehydrogenase (XDH/XO; EC 1.1.1.204/1.1.3.22)

(43). The hepatic localization of XOR is zonally distributed, with

higher activity in pericentral, compared with periportal, hepatocytes

(44). The zonal distribution of XOR corresponds to regions where

ischemia and hypoxia would be most severe, as oxygen is extracted as

blood flows from the portal triad to the central vein branches. During

ischemia, XOR can be converted to XO by either proteolytic cleavage of

the amino terminus or more rapidly by intramolecular and mixed

disulfide formation (45, 46). Significant irreversible proteolytic

conversion of cellular XOR to XO is slow, requiring 4–6 h of ischemia

(47). However, XOR can be released from ischemic hepatocytes into the

circulation before detectable intracellular XOR to XO conversion (48),

whereupon either proteolytic cleavage or thiol oxidation may occur

rapidly. Repeated interruption of blood flow and the resultant

transient ischemia associated with SCD can thus provide the basis for

ischemic liver injury and elevated plasma XO levels. During

experimental hypoxia, XOR to XO conversion has been shown to be

significantly greater in the liver and kidneys of a sickle cell mice

model that had a mixture of human HbS and murine Hb (24). In the

knockout-transgenic mouse model of SCD used herein, extensive

hepatocellular injury (Fig. 2C), accompanied by increased

plasma alanine aminotransferase levels (Table 1) and decreased liver XO

immunoreactivity (Fig. 2B) and catalytic activity

(Table 1), was observed even under normoxic conditions. Even though

rodents have much greater XOR-specific activities in plasma than humans

(49), release of this enzyme from XOR-replete human splanchnic tissues

can still have potent pathophysiologic effects. Present evidence

supports that not only the extent of XO-dependent tissue

O production, but also its anatomic location,

will determine whether or not vascular ⋅NO-dependent signaling

is adversely affected (50).

production, but also its anatomic location,

will determine whether or not vascular ⋅NO-dependent signaling

is adversely affected (50).

The immunohistochemical localization of increased XO in the vessel wall of SCD mice could be a manifestation of either the binding and uptake of circulating XO by vascular endothelial cells (33, 50, 51) or the increased expression of XOR by activated vascular endothelium (52). Considering the high association constant of XO for binding to vascular endothelium (Kd = 6 nM; ref. 53), the presence of XO in the systemic circulation of both SCD mice and humans with SCD implies that a significant deposition of XO can occur in the vessel wall, even when considering the typically low expression of vascular cell XOR in humans (53).

The ability of endothelial-bound XO to remain catalytically active and

generate O and

H2O2 at anatomic sites

remote from the locus of XO release (50) is consistent with the

increased basal rates of O

and

H2O2 at anatomic sites

remote from the locus of XO release (50) is consistent with the

increased basal rates of O production

quantified in SCD mouse aorta (Fig. 3). Addition of xanthine enhanced

rates of O

production

quantified in SCD mouse aorta (Fig. 3). Addition of xanthine enhanced

rates of O release that were normalized with

the XO inhibitors allopurinol and BOF-4272, confirming the XO-mediated

increase of vascular O

release that were normalized with

the XO inhibitors allopurinol and BOF-4272, confirming the XO-mediated

increase of vascular O and

H2O2 production in sickle

vessels (Fig. 3). The preincubation of control and SCD mouse vessels

with CuZn SOD caused a 10% and 32% reduction in rates of detectable

O

and

H2O2 production in sickle

vessels (Fig. 3). The preincubation of control and SCD mouse vessels

with CuZn SOD caused a 10% and 32% reduction in rates of detectable

O , respectively. The modest inhibition of

detectable rates of O

, respectively. The modest inhibition of

detectable rates of O generation by CuZn SOD

supports the concept that size exclusion and charge repulsion of this

enzyme from the intracellular milieu impedes its ability to scavenge

O

generation by CuZn SOD

supports the concept that size exclusion and charge repulsion of this

enzyme from the intracellular milieu impedes its ability to scavenge

O generated by cell-associated XO (50).

Pretreatment of aortic vessels with the more cell-avid and

membrane-permeable SOD mimetic MnTE-2-PyP (54, 55) had a greater impact

on scavenging O

generated by cell-associated XO (50).

Pretreatment of aortic vessels with the more cell-avid and

membrane-permeable SOD mimetic MnTE-2-PyP (54, 55) had a greater impact

on scavenging O , giving a 33% and 50%

reduction in rates of O

, giving a 33% and 50%

reduction in rates of O release in control and

sickle vessels, respectively.

release in control and

sickle vessels, respectively.

XO-derived O will react with ⋅NO

at diffusion-limited rates to impair ⋅NO signaling and

concomitantly yield secondary oxidizing species, such as

ONOO−, that can further propagate tissue injury

(25, 56, 57). A challenge for the future is the delineation of acute

versus chronic actions of XO on vascular function in SCD. Although no

restorative effects of catalase on vessel relaxation were observed

(Fig. 4), XO-derived H2O2

can serve as a peroxidase substrate (e.g., for neutrophil

myeloperoxidase) that in turn stimulates the catalytic consumption of

⋅NO and the formation of secondary oxidizing and nitrating

species, possibly leading to more chronic forms of vessel injury (58).

A precedent for these phenomena exists in animal models and clinical

studies of atherosclerosis. In a hypercholesterolemic rabbit model of

atherosclerosis, a 2.5-fold increase in plasma XO severely impairs

ACh-mediated relaxation of the thoracic aorta (33, 59). Heparin-induced

dissociation of XO from vessel wall binding sites and

allopurinol-mediated XO inhibition partially restores ACh-dependent

relaxation and decreases vessel O

will react with ⋅NO

at diffusion-limited rates to impair ⋅NO signaling and

concomitantly yield secondary oxidizing species, such as

ONOO−, that can further propagate tissue injury

(25, 56, 57). A challenge for the future is the delineation of acute

versus chronic actions of XO on vascular function in SCD. Although no

restorative effects of catalase on vessel relaxation were observed

(Fig. 4), XO-derived H2O2

can serve as a peroxidase substrate (e.g., for neutrophil

myeloperoxidase) that in turn stimulates the catalytic consumption of

⋅NO and the formation of secondary oxidizing and nitrating

species, possibly leading to more chronic forms of vessel injury (58).

A precedent for these phenomena exists in animal models and clinical

studies of atherosclerosis. In a hypercholesterolemic rabbit model of

atherosclerosis, a 2.5-fold increase in plasma XO severely impairs

ACh-mediated relaxation of the thoracic aorta (33, 59). Heparin-induced

dissociation of XO from vessel wall binding sites and

allopurinol-mediated XO inhibition partially restores ACh-dependent

relaxation and decreases vessel O production

(33). In atherosclerotic and diabetic humans, the XO inhibitors

allopurinol and oxypurinol increase forearm blood flow and decrease

blood pressure (60, 61). Thus, increased circulating and vessel wall XO

in SCD can account for hemodynamic instability and contribute to the

pathogenesis of a broader systemic vascular dysfunction. This is

exemplified by the observation of impaired ⋅NO-dependent

vasorelaxation in SCD mice (Fig. 4) and affirms the blunted vascular

relaxation that occurs in SCD mouse vessels in response to a calcium

ionophore and the ⋅NO donor DEA-NONOate (62). This impaired

vessel relaxation was restored by denudation of endothelium (62),

supporting the presently observed generation of ⋅NO-inactivating

species by the endothelium of SCD vessels. Importantly, the inhibition

of vessel relaxation observed herein was completely restored by sodium

nitroprusside (not shown). Because sodium nitroprusside is metabolized

by smooth muscle cells (63), this excludes the existence of an

end-organ defect in ⋅NO signaling and further confirms that

⋅NO is being consumed by endothelial-derived free radical

reactions in SCD vessels. This impairment of ⋅NO-dependent

vascular relaxation by increased rates of reactive oxygen species

generation was underscored by the observation that the SOD mimetic

MnTE-2-PyP restored ACh-dependent relaxation of SCD mouse vessels.

production

(33). In atherosclerotic and diabetic humans, the XO inhibitors

allopurinol and oxypurinol increase forearm blood flow and decrease

blood pressure (60, 61). Thus, increased circulating and vessel wall XO

in SCD can account for hemodynamic instability and contribute to the

pathogenesis of a broader systemic vascular dysfunction. This is

exemplified by the observation of impaired ⋅NO-dependent

vasorelaxation in SCD mice (Fig. 4) and affirms the blunted vascular

relaxation that occurs in SCD mouse vessels in response to a calcium

ionophore and the ⋅NO donor DEA-NONOate (62). This impaired

vessel relaxation was restored by denudation of endothelium (62),

supporting the presently observed generation of ⋅NO-inactivating

species by the endothelium of SCD vessels. Importantly, the inhibition

of vessel relaxation observed herein was completely restored by sodium

nitroprusside (not shown). Because sodium nitroprusside is metabolized

by smooth muscle cells (63), this excludes the existence of an

end-organ defect in ⋅NO signaling and further confirms that

⋅NO is being consumed by endothelial-derived free radical

reactions in SCD vessels. This impairment of ⋅NO-dependent

vascular relaxation by increased rates of reactive oxygen species

generation was underscored by the observation that the SOD mimetic

MnTE-2-PyP restored ACh-dependent relaxation of SCD mouse vessels.

Plasma uric acid and XO levels are strongly predictive of hypertension in normotensive subjects (64). Although hypertension is not associated with SCD, sickle patients with high blood pressure have an increased risk of stroke and death (65). Systolic blood pressure is not increased in an SCD mouse model compared with the background strain (62); however, a 5-fold greater increase in systolic blood pressure is observed in SCD mice when the NO synthase inhibitor l-NAME is administered, again affirming the concept of enhanced ⋅NO consumption and impaired vascular ⋅NO signaling in SCD.

In summary, episodes of hypoxia-reoxygenation associated with SCD lead

to the release of XO into the circulation from hepatic cells replete in

the activity of this source of O and

H2O2. Increased circulating

XO can then bind avidly to vessel luminal cells and impair vascular

function by creating an oxidative milieu and catalytically consuming

⋅NO via diffusion-limited reaction with

O

and

H2O2. Increased circulating

XO can then bind avidly to vessel luminal cells and impair vascular

function by creating an oxidative milieu and catalytically consuming

⋅NO via diffusion-limited reaction with

O . Considering the critical role of

endothelial ⋅NO production in regulating endothelial adhesion

molecule expression, platelet aggregation, and both basal and

stress-mediated vasodilation, the O

. Considering the critical role of

endothelial ⋅NO production in regulating endothelial adhesion

molecule expression, platelet aggregation, and both basal and

stress-mediated vasodilation, the O -mediated

reduction in ⋅NO bioavailability reported herein can

significantly contribute to the vascular disease that is the hallmark

of sickle cell anemia.

-mediated

reduction in ⋅NO bioavailability reported herein can

significantly contribute to the vascular disease that is the hallmark

of sickle cell anemia.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate insights and assistance provided by Denyse Thornley-Brown, MD, Elizabeth Lowenthal, MD, Phil Chumley, and Scott Sweeney. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants RO1-HL64937, RO1-HL58115, and P6-HL58418 and by Aeolus, Inc.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- DMNQ

2,3-dimethoxy-1-napthoquinone

- MnTE-2-PyP

manganese 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(N-ethylpyridinium-2-yl)-porphyrin

- SCD

sickle cell disease

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- XO

xanthine oxidase

- XOR

xanthine oxidoreductase

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

References

- 1.Embury S H, Mohandas N, Paszty C, Cooper P, Cheung A T. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:915–920. doi: 10.1172/JCI5977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belcher J D, Marker P H, Weber J P, Hebbel R P, Vercellotti G M. Blood. 2000;96:2451–2459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hebbel R P, Visser M R, Goodman J L, Jacob H S, Vercellotti G M. J Clin Invest. 1987;80:1503–1506. doi: 10.1172/JCI113233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shiu Y T, Udden M M, McIntire L V. Blood. 2000;95:3232–3241. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuart M J, Setty B N. Blood. 1999;94:1555–1560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaul D K, Hebbel R P. Clin Invest. 2000;106:411–420. doi: 10.1172/JCI9225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Solovey A A, Solovey A N, Harkness J, Hebbel R P. Blood. 2001;97:1937–1941. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.7.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Solovey A, Gui L, Key N S, Hebbel R P. J Clin Invest. 1998;101:1899–1904. doi: 10.1172/JCI1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stockman J A, Nigro M A, Mishkin M M, Oski F A. N Engl J Med. 1972;287:846–849. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197210262871703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merkel K H, Ginsberg P L, Parker J C, Jr, Post M J. Stroke. 1978;9:45–52. doi: 10.1161/01.str.9.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ballas S K, Larner J, Smith E D, Surrey S, Schwartz E, Rappaport E F. Blood. 1988;72:1216–1223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lande W M, Andrews D L, Clark M R, Braham N V, Black D M, Embury S H, Mentzer W C. Blood. 1988;72:2056–2059. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Johnson C S, Giorgio A J. Arch Intern Med. 1981;141:891–893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enwonwu C O. Med Sci Res. 1989;17:997–998. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hatch F E, Crowe L R, Miles D E, Young J P, Portner M E. Am J Hypertens. 1989;2:2–8. doi: 10.1093/ajh/2.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Allon M. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:501–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mantadakis E, Cavender J D, Rogers Z R, Ewalt D H, Buchanan G R. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1999;21:518–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rees D C, Cervi P, Grimwade D, O'Driscoll A, Hamilton M, Parker N E, Porter J B. Br J Haematol. 1995;91:834–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb05397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morris C R, Kuypers F A, Larkin S, Sweeters N, Simon J, Vichinsky E P, Styles L A. Br J Haematol. 2000;111:498–500. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2000.02403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Atz A M, Wessel D L. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:988–990. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199710000-00037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glover R E, Ivy E D, Orringer E P, Maeda H, Mason R P. Mol Pharmacol. 1999;55:1006–1010. doi: 10.1124/mol.55.6.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hebbel R P, Eaton J W, Balasingam M, Steinberg M H. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:1253–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI110724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuross S A, Hebbel R P. Blood. 1988;72:1278–1285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osarogiagbon U R, Choong S, Belcher J D, Vercellotti G M, Paller M S, Hebbel R P. Blood. 2000;1:314–320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beckman J S, Beckman T W, Chan J, Marshall P S, Freeman B A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:1620–1624. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Radi R, Beckman J S, Bush K M, Freeman B A. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1991;228:481–487. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(91)90224-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubbo H, Radi R, Trujillo M, Telleri R, Kalyanaraman B, Barnes S, Kirk M, Freeman B A. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26066–26075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Beutler E R, editor. Cell Metabolism: A Manual of Biochemical Methods. 3rd Ed. Orlando, FL: Grune & Stratton; 1984. pp. 8–13. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Royall J A, Gwin P D, Parks D A, Freeman B A. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1992;294:686–694. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90742-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan S, Radi R, Gaudier F, Evans R A, Rivera A, Kirk K A, Parks D A. Pediatr Res. 1993;34:303–307. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199309000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ryan T M, Ciavatta D J, Townes T M. Science. 1997;278:873–876. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5339.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parks D. In: Reactive Oxygen Species in Biological Systems. Gilbert D L, Colton C, editors. New York: Plenum; 1998. pp. 397–420. [Google Scholar]

- 33.White R C, Darley-Usmar V, Berrington R W, McAdams M, Gore Z J, Thomson A J, Parks A D, Tarpey M M, Freeman B A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8745–8749. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarpey M M, White C R, Suarez E, Richardson G, Radi R, Freeman B A. Circ Res. 1999;84:1203–1211. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.10.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aslan M, Thornley-Brown D, Freeman B A. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2000;899:375–391. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grum C M, Ragsdale R A, Ketai L H, Simon R H. J Crit Care. 1987;2:22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giler S, Sperling O, Brosh S, Urca I, De Vries A. Clin Chim Acta. 1975;63:37–40. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(75)90375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giler S, Sperling O, Brosh S, Urca I, De Vries A. Isr J Med Sci. 1975;11:1225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolko K, Krawczynski J. Mater Med Pol. 1974;6:95–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parks D A, Granger D N. Am J Physiol. 1983;245:G285–G289. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1983.245.2.G285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohacsi A, Kozlovszky B, Kiss I, Seres I, Fulop T., Jr Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996;1316:210–216. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(96)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parks D A, Skinner K A, Skinner H B, Tan S. Pathophysiology. 1998;5:49–66. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kooij A, Schijns M, Frederiks W M, Van Noorden C J, James J. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol Incl Mol Pathol. 1992;63:17–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02899240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kooij A. Histochem J. 1994;26:889–915. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Enroth C, Eger B T, Okamoto K, Nishino T, Nishino T, Pai E F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10723–10728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.20.10723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Amaya Y, Yamazaki K, Sato M, Noda K, Nishino T. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14170–14175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Engerson T D, McKelvey T G, Rhyne D B, Boggio E B, Snyder S J, Jones H P. J Clin Invest. 1987;6:1564–1570. doi: 10.1172/JCI112990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yokoyama Y, Beckman J S, Beckman T K, Wheat J K, Cash T G, Freeman B A, Parks D A. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:G564–G570. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.258.4.G564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Khalidi A S, Chaglassian T H. Biochem J. 1965;97:318–320. doi: 10.1042/bj0970318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Houston M, Estevez A, Chumley P, Aslan M, Marklund S, Parks D A, Freeman B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4985–4994. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.4985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Radi R, Rubbo H, Bush K, Freeman B A. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1997;339:125–135. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1996.9844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dupont G P, Huecksteadt T P, Marshall B C, Ryan U S, Michael J R, Hoidal J R. J Clin Invest. 1992;1:197–202. doi: 10.1172/JCI115563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Paler-Martinez A, Panus P C, Chumley P H, Ryan U, Hardy M M, Freeman B A. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1994;311:79–85. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1994.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patel M, Day B J. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;9:359–364. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Spasojevic I, Batinic-Haberle I, Fridovich I. Nitric Oxide. 2000;5:526–533. doi: 10.1006/niox.2000.0303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kissner R, Nauser T, Bugnon P, Lye P G, Koppenol W H. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1285–1292. doi: 10.1021/tx970160x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Villa L M, Salas E, Darley-Usmar V M, Radomski M W, Moncada S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12383–12387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van der Vliet A, Eiserich J P, Halliwell B, Cross C E. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7617–7625. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.White C R, Brock T A, Chang L Y, Crapo J, Briscoe P, Ku D, Bradley W A, Gianturco S H, Gore J, Freeman B A, Tarpey M M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1044–1048. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.3.1044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cardillo C, Kilcoyne C M, Cannon R O, III, Quyyumi A A, Panza J A. Hypertension. 1997;30:57–63. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.30.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Butler R, Morris A D, Belch J J, Hill A, Struthers A D. Hypertension. 2000;35:746–751. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.35.3.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nath K A, Shah V, Haggard J J, Croatt A J, Smith L A, Hebbel R P, Katusic Z S. Am J Physiol. 2000;279:R1949–R1955. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.279.6.R1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kowaluk E A, Seth P, Fung H L. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:916–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Newaz M A, Adeeb N N, Muslim N, Razak T A, Htut N N. Clin Exp Hypertens. 1996;8:1035–1050. doi: 10.3109/10641969609081033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pegelow C H, Colangelo L, Steinberg M, Wright E C, Smith J, Phillips G, Vichinsky E. Am J Med. 1997;2:171–177. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00407-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]