Abstract

Background

Procrastination, defined as irrational and voluntary delaying of necessary tasks, is widespread and clinically relevant. Its high prevalence among college students comes with serious consequences for mental health and well-being of those affected. Research for proper treatment is still relatively scarce and treatment of choice seems to be cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). The aim of this study is to evaluate the effectiveness and acceptability of an internet- and mobile-based intervention (IMI) for procrastination based on CBT for college students.

Methods

A two-armed randomized controlled trial with a calculated sample size of N = 120 participants with problematic procrastination behavior will be conducted. Students will be recruited in Germany, Austria and Switzerland via circular emails at 15+ cooperating universities in the framework of StudiCare, a well-established project that provides IMIs to college students for different health related issues. The intervention group will receive the e-coach guided 5-week IMI StudiCare Procrastination. A waitlist-control group will get access to the unguided IMI 12 weeks after randomization. Assessments will take place before as well as 6 and 12 weeks after randomization. Primary outcome is procrastination, measured by the Irrational Procrastination Scale (IPS). Secondary outcomes include susceptibility to temptation, depression, anxiety, wellbeing and self-efficacy as well as acceptability aspects such as intervention satisfaction, adherence and potential side effects. Additionally, several potential moderators as well as the potential mediators self-efficacy and susceptibility to temptation will be examined exploratorily. Data-analysis will be performed on intention-to-treat basis.

Discussion

This study will contribute to the evidence concerning effectiveness and acceptability of an intervention for procrastination delivered via the internet. If it shows to be effective, StudiCare Procrastination could provide a low-threshold, cost-efficient way to help the multitude of students suffering from problems caused by procrastination.

Trial registration: The trial is registered at the WHO International Clinical Trials Registry Platform via the German Clinical Studies Trial Register (DRKS): DRKS00014321 (date of registration: 06.04.2018). In case of important protocol modifications, trial registration will be updated.

Trial status: This is protocol version number 1, 11th December 2019. Recruitment started 9th of April 2018 and was completed 30th of November 2018. Assessment and intervention are still ongoing and will be completed by April 2019.

Keywords: Procrastination, Internet-based intervention, Online intervention, Cognitive behavior therapy, Randomized controlled trial, College students

Highlights

-

•

Procrastination is common among college students and associated with negative consequences on health and academic success.

-

•

The effectiveness of a guided Internet-based intervention for procrastination will be compared to a waitlist control group.

-

•

A range of secondary outcomes like depression, anxiety and stress will be investigated.

-

•

Moderators and mediators as well as potential risks and side-effects will be explored.

1. Introduction

Procrastination is defined as irrationally and voluntarily putting off or delaying tasks despite knowing one is acting against their own best interests (Steel, 2011). Particularly when postponing tasks that need to be done has become a habit and is perceived as stressful, procrastination can be a real struggle (Rozental and Carlbring, 2014). Procrastination represents a failure of self-regulation, creating a discrepancy between intention and behavior (Höcker, Engberding, Haferkamp, & Rist, 2012). When people who procrastinate are faced with working on important deadlines, they often put their attention on short-term distractions like browsing the internet or cleaning one's room that are associated with more immediate reward (Steel, 2007) or the avoidance of negative feelings (Pychyl et al., 2000; Steel, 2007), e.g. self-criticism or boredom.

In a meta-analysis several variables were found to be associated with procrastination behavior, such as task aversiveness, self-efficacy, distractibility, conscientiousness, self-control, impulsiveness, achievement motivation and even genetic components (Steel, 2007). Steel and König's (2006) temporal motivational theory (TMT) integrates many of these variables. Whether a particular person procrastinates a certain task depends on the interaction of four factors, namely the value of the outcome, the expectation of achieving the outcome, the timing of that outcome and the individual ability to delay gratification. As timing is an important variable, smaller short-term benefits might be preferred to larger long-term benefits. Similarly, larger long-term punishments might be accepted in order to avoid short-term punishments, thus providing another explanation why e.g. learning activities might be postponed in favor watching television despite negative long-term consequences (Steel and König, 2006).

Procrastination behavior is a widespread phenomenon. A representative German study explored the prevalence of procrastination and found it ranging between 16% and 32% in the general adult population (Beutel et al., 2016). This corresponds to international studies that found rates of 15–20% (Day et al., 2000; Ferrari et al., 2005). In an academic context, findings indicate about 50–70% of college students show frequent and significant procrastination behavior (Ellis and Knaus, 1977; Mahasneh et al., 2016; Onwuegbuzie, 2004; Özer et al., 2009). It should be noted that these numbers should be interpreted with caution, as no clear diagnostic criteria for the differentiation between severe and “normal” procrastination exist (Steel, 2007).

A German study using a representative community sample found that procrastination is linked to higher stress, more depression, anxiety, fatigue and reduced satisfaction regarding work and income (Beutel et al., 2016). Additionally, college students who are often postponing tasks are more dissatisfied with themselves, show poorer general health and have more problems in social relationships (Höcker et al., 2013; Stead et al., 2010). A longitudinal study reports that at the end of the semester, procrastinators show a higher level of stress and illness susceptibility and score worse in exams (Tice and Baumeister, 1997). Therefore, providing help for procrastination is a prominent issue, especially for the widely affected target group of college students.

Despite the high prevalence rate of procrastination and the negative consequences on health and well-being, there is still no generally accepted standard of care (Glick and Orsillo, 2015). However, several studies already provide some evidence for potentially effective methods. These include time management strategies, such as the setting of deadlines (Ariely and Wertenbroch, 2002), the creation of specific goal setting plans (Gollwitzer and Brandstätter, 1997; Häfner et al., 2014) or the practice of learning strategies (Tuckman and Schouwenburg, 2004). Interventions regarding self-regulation also seem to be effective (Steel, 2007). A recently published meta-analysis comes to the conclusion that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which incorporates many of the aforementioned techniques, is the treatment of choice for procrastination (van Eerde and Klingsieck, 2018). Another meta-analysis by Rozental et al. (2018a) found small benefits for psychological treatments in general (N = 12; g = 0.45, 95% CI [0.11, 0.56]) and moderate effects for CBT (subgroup analysis, N = 3: g = 0.55, 95% CI [0.32, 0.77]). However, given the small number of high-quality studies, significant heterogeneity and often small sample sizes, the authors conclude that there is a great need for high-quality adequately powered RCTs (Rozental et al., 2018a).

Given the high prevalence of procrastination and its negative consequences, developing cost-effective, low-threshold interventions is of great importance. Internet- and mobile-based interventions (IMIs) might offer an excellent way to meet this demand (Glick and Orsillo, 2015). In recent years, a large body of research has evaluated the efficacy of IMIs in general (Andersson et al., 2014). They show comparable effectiveness to traditional face-to-face therapy (Carlbring et al., 2018; Ebert et al., 2018) and have several advantages, such as cost-effective design and the elimination of barriers such as treatment access and waiting times (Paganini et al., 2018). For procrastination specifically, there are also some findings indicating the efficiency of such trainings (Eckert et al., 2018; Gieselmann and Pietrowsky, 2016; Lukas and Berking, 2018; Rozental et al., 2018b; Rozental et al., 2015b). In a randomized-controlled study by Rozental et al., (2015b) the effectiveness of an IMI built on CBT to reduce procrastination was investigated in a total of 150 participants from the general population. Effect sizes ranged between d = 0.50, 95% CI [0.10, 0.90] and d = 0.81, 95% CI [0.40, 1.22] for both the guided and the unguided IMI compared to the waitlist control group. Additionally, they found large within-group effect sizes of d = 1.44–1.64, 95% CI [0.94, 1.97] pre-treatment to 12-months follow-up (Rozental et al., 2017). Eckert et al. (2018) found somewhat smaller effects between d = 0.29, 95% CI [−0.70, 0.06] (without SMS support) and d = 0.57, 95% CI [−0.96, −0.18] (with SMS support) for their unguided 2-week internet-based intervention (Eckert et al., 2018).

In summary, while there is some evidence for the efficacy of CBT-based IMIs for procrastination, there is a need for high-quality, adequately powered RCTs to support these conclusions (Rozental et al., 2018a). The present study aims to replicate and expand existing results for the effectiveness of IMIs for procrastination in a large sample of students from a network of cooperating colleges across Germany, Switzerland and Austria. Since procrastination is associated with various aspects of psychological well-being (Beutel et al., 2016; Steel, 2007; Tice and Baumeister, 1997), we will also look at a range of secondary outcomes like the still understudied variables of depression and anxiety (Rozental et al., 2018a). Finally, we will gather preliminary evidence for a selection of potential moderators and two theoretically derived mediators (Steel and König, 2006). Concerning the latter, we will examine self-efficacy (“expectation of achieving the outcome”) and susceptibility to temptation (“ability to delay gratification”), which have been shown to be important correlates with procrastination behavior (Steel, 2007). The research questions are as follows:

-

1.

Is StudiCare Procrastination effective in reducing problematic procrastination behavior in college students compared to a waitlist control group?

-

2.

What are the effects on the secondary outcomes impulsivity, depression, anxiety, wellbeing and self-efficacy?

-

3.

How acceptable is StudiCare Procrastination in a college student sample concerning intervention satisfaction and adherence?

-

4.

Are there any risks or side-effects?

-

5.

Are there any moderators and mediators of treatment effectiveness?

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

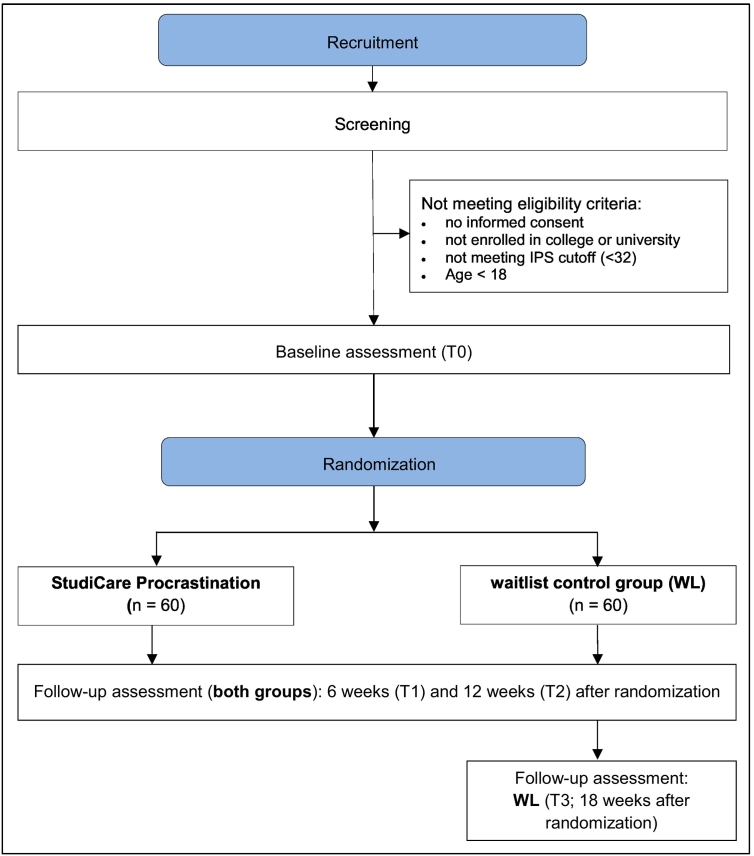

This two-armed, randomized controlled trial of parallel design is comparing the effectiveness of the guided internet-based intervention StudiCare Procrastination to a waitlist control group (WL) receiving no intervention (superiority trial; see Fig. 1 for flow diagram). Participants were recruited from May until November 2018. While all participants have been randomized by now, intervention and assessment are still ongoing. The trial was originally planned as a feasibility trial, but was changed prior to recruitment into a properly powered effectiveness trial due to the growing evidence for the efficacy of procrastination IMIs (Eckert et al., 2018; Lukas and Berking, 2018). The study is conducted within the StudiCare project (www.studicare.com) funded by BARMER. StudiCare offers internet- and mobile-based health promotion interventions to college students with a focus on psychological and behavioral issues, e.g. mindfulness, stress, test anxiety, physical activity, depression or substance use (www.studicare.com) (Ebert et al., 2018; Fleischmann et al., 2018; Harrer et al., 2018). Assessment takes place before (T0) and after the intervention (T1, 6 weeks after randomization) as well as after a follow-up period (T2, 12 weeks after randomization). Since participants in the waiting list control group also have access to the unguided program after completion of the follow-up assessment (T3), there is another assessment for the WL (T4, 18 weeks after randomization) to allow an initial assessment of the effects of the unguided training. The present study is conducted and reported according to the CONSORT 2010 statement (Schulz, Altman, Moher, and CONSORT Group, 2010) and the guidelines for executing and reporting internet intervention research (Proudfoot et al., 2011). The study protocol follows recommendations of the SPIRIT 2013 Checklist for clinical trial protocols (Chan et al., 2013).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

The primary eligibility criterion for participation is based on whether the individuals' self-reported Irrational Procrastination Scale (IPS) score reaches a certain threshold, defined to be 32 or above. Since procrastination is no clinical diagnosis, this cutoff value was determined based on a recent study (Rozental et al., 2015b) to include individuals that are significantly suffering from procrastination. Further requirements for inclusion are a minimum age of 18 years, enrolled in university or college as well as access to the internet and sufficient knowledge of the German language (assessed via capability to proceed through enrollment and screening process). Participants also have to sign an informed consent to be included.

2.3. Setting/recruitment

As mentioned before, recruitment took place from May to November 2018, while assessment and intervention are still ongoing. Participants are self-recruited via various advertisement strategies. The StudiCare project has multiple partner colleges (15+) in Germany, Switzerland and Austria that send out circular emails informing about recruiting StudiCare trials to all their students on a regular basis (for full list of colleges see www.studicare.com). Participants are also recruited via flyers and posters, social media, student unions and student counselling.

2.4. Procedure

All recruitment measures lead to the StudiCare website, where potential participants of all ongoing StudiCare trials can register via a contact form for their intervention of choice. After initial contact they receive an e-mail with a link to a brief eligibility screening. Potential participants meeting inclusion criteria then receive an automated e-mail including detailed participant information as well as an informed consent form. If eligibility criteria are not met, students automatically receive information about alternative support offers and an overview of psychosocial counselling centers. Once informed consent is given (via email or mail), participants are invited to pre-assessment and then randomized and either granted access to the guided version of StudiCare Procrastination immediately (intervention group) or to the unguided version (waitlist control group) after completion of follow-up assessment (after about 12 weeks).

2.5. Randomization

Randomization and allocation are performed by an independent researcher not otherwise involved in the study using an online-based, automated randomization program (www.sealedenvelope.com). Permuted block randomization with an allocation ratio of 1:1 and variable block sizes of 2 and 4 (randomly arranged) is performed.

2.6. Intervention

StudiCare Procrastination is based on a CBT manual for the treatment of pathological procrastination (Höcker et al., 2013). The intervention was originally developed by the Department for Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, Ulm University. An alpha version of the intervention was already evaluated in a small study to support the development process (N = 50; not published). Participant feedback collected in this study was incorporated in the latest version of the intervention used in this RCT. The overall graphic design was revised and designed more persuasive. Furthermore, various interactive design elements such as videos, audio files, pictures and exercises were added.

Intervention content is structured into five modules that are recommended to be worked through on a weekly basis. All modules share one common goal. During the five-week training period, participants learn to recognize the patterns and consequences of their working behaviors and to change them accordingly. This enables them to evaluate their working sessions, study more effectively and connects them with a sense of achievement. The order of modules within the intervention is fixed and activation takes place successively. Characteristic of all modules is their brevity and their behavior-based assessments at the beginning of each session as well as many exercises and homework assignments promoting transfer into everyday life.

The first module's main aim is psychoeducation by teaching participants about their symptoms and underlying processes via self-monitoring, the Rubicon Model of Action Phases (Achtziger and Gollwitzer, 2007) and the ABC Model (Ellis, 1973). The second module teaches participants how to effectively use their time without procrastinating, practicing strategies like goal-setting, prioritization and scheduling. Module 3 focuses on motivation. Participants learn how to classify their personal procrastination pattern according to the Rubicon Model and how to bridge the intention-behavior gap using rewards and rituals. The forth module's goal is to give theoretical knowledge about self-regulation, self-control and their importance for controlling procrastination tendencies. With the help of various exercises and techniques to handle procrastination in everyday life, participants learn how to train their self-regulatory abilities. The module also includes an introduction to relaxation and mindfulness exercises, as those have been shown to improve the regulation of negative affect and executive-function performance (Leyland et al., 2019). The last module summarizes the previous modules and focuses on strategies to prevent a relapse into old behavior patterns of procrastination. For a more detailed overview of module content, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Intervention content.

| Module | Content | Exercises |

|---|---|---|

| 1) Background knowledge | Information on procrastination behavior and the fact that it can be changed; what to expect from the intervention; creating interest and highlighting benefits. | Self-monitoring protocol; identification of personal ABC model; homework: daily self-monitoring |

| 2) Time-management | Introduction to time management; advice on how to effectively set goals and priorities; importance of beginning right on time; creating a realistic timetable with breaks. | Self-monitoring; identification of personal goal with SMART; setting priorities; homework: establish a time schedule |

| 3) Motivation | Effectively using rewards and rituals; learning how to use distractions and concentration in your favor. | Self-monitoring; establishing rituals; setting regular working timeframe; identifying and dealing with personal distractions; homework: check your workplace |

| 4) Self-regulation | Introduction to self-regulation and self-control and how to train these abilities; practicing mindfulness and acceptance. | Self-monitoring; meditation exercise; homework: daily meditation practice |

| 5) Booster session | Repetition of previous modules and “relapse prevention”. | Self-monitoring; repetition of important exercises (e.g. goal setting); contemplation of personal progress; relapse prevention |

The intervention is available to participants on the Minddistrict platform (www.minddistrict.com/de-de), a company specialized in the provision of internet-based health interventions. Participants are able to access the platform via their personal username and password on a 24/7 basis. All transferred data is secured based on ISO27001 and NEN7510 guidelines.

2.6.1. Guidance

Participants in the intervention group receive feedback from trained and supervised (by HB, AK) psychologists (e-coaches) via e-mail and can use the Minddistrict platform to contact their e-coach at any time. This is intended to increase adherence and reduce dropout (Andersson et al., 2009; Brouwer et al., 2011; Mohr et al., 2011). E-coaches respond within two work days and send weekly brief semi-standardized feedback specific to the participants' assignments via Minddistrict. Feedback will include positive reinforcements and encourage participants to continue working with the intervention. E-coaches also send reminder emails if participants do not meet their self-chosen deadline for the next module.

2.7. Control condition

Participants in the waitlist control group have unrestricted access to usual treatment options during the waiting period. They will be informed about alternative support options, e.g. University counselling services, psychotherapy or helplines and encouraged to seek help if needed. WL participants receive the unguided version of the intervention 3 months after randomization and are able to contact the study team via the Minddistrict platform for technical support. Participants of the IG and the WL are all uniformly informed that the intervention involves some kind of support, but do not know about the nature of support the other group receives to prevent potential bias. Otherwise, due to the use of a waitlist control group, participants cannot be blinded to allocation.

2.8. Assessment and outcomes

Assessment takes place via the online survey platform Unipark (www.unipark.de) and does not involve any personal contact between staff and participants. Participants are reminded via email or telephone to complete surveys if they do not respond to invitation emails. All outcomes and time points are listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Outcome assessments and time points.

| Variables | Measurement | Time of measurement |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 (WL) | ||

| Sociodemographics | SR | X | |||

| Procrastination | IPS | X | X | X | X |

| Susceptibility for distractions | STS | X | X | X | X |

| Depression | PHQ-9 | X | X | X | X |

| Anxiety | GAD-7 | X | X | X | X |

| Stress | PSS | X | X | X | X |

| Self-efficacy | SWE, WIRKSTUD | X | X | X | X |

| Well-being | WHO-5 | X | X | X | X |

| Risks and side effects | INEP | X | X (only intervention group) | X | |

| Use of other support offers | SR | X | X | X | X |

| Patient satisfaction | ZUF-8 | X (only intervention group) | X | ||

| Treatment expectations | CEQ | X | |||

| Acceptance and feedback for StudiCare procrastination | SR | X (only intervention group) | X | ||

CEQ = Credibility Expectancy Questionnaire; GAD-7 = Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionaire-9; PSS = Patient Stress Scale; IPS = Irrational Procrastination Scale; SR = self-reported assessment; STS = Susceptibility to Temptation; SWE = General Self-Efficacy; WHO-5 = Well-Being Index-5; WIRKSTUD = Study-Specific Self-Efficacy; ZUF-8 = Questionnaire for Patient Satisfaction-8; WL = Waitlist-control group only.

2.8.1. Primary outcome: Irrational Procrastination Scale (IPS)

To measure the primary outcome, the IPS (Steel, 2010) is used. It measures the degree of irrational delay causing procrastination. The German version of the IPS (Svartdal et al., 2016) consists of nine questions, e.g. “I put things off so long that my well-being or efficiency unnecessarily suffers”. Participants can respond on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = “Very seldom or not true to me” to 5 = “Very often true, or true to me”. The scale has shown to have good internal consistency of α = 0.91 (Steel, 2010).

2.8.2. Secondary outcomes

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002) is used for the assessment of depressive symptoms. It features nine items (e.g. “Little interest or enjoyment of your activities”) on a four-point Likert scale (0 = “Not at all” to 3 = “Nearly every day”). It has excellent internal consistency of α = 0.89 (Kroenke and Spitzer, 2002).

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire-7 (GAD-7) (Spitzer et al., 2006) is a screening instrument for generalized anxiety disorder which consists of seven items (e.g. “Feeling afraid as if something awful might happen”) with a four-point scale (0 = “Not at all” to 4 = “Nearly every day”),. It has excellent internal consistency with Cronbach's α = 0.91 (Spitzer et al., 2006).

The Short Form Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4), derived from the Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen and Williamson, 1988), has four items (e.g. “In the last month, how often have you felt that you were unable to control the important things in your life?”) and a scale ranging from 0 = “Never” to 4 = “Very often”. Psychometric properties of the PSS-4 have been found to be acceptable and reliable across cultures, with an internal consistency of α = 0.77 (Warttig et al., 2013).

To assess subjective psychological well-being, the 5-item World Health Organization Well-Being Index (WHO-5) (World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, and Unit, 1998) is used (e.g. “I have felt cheerful and in good spirits”). The scale ranges from 5 = “all of the time” to 0 = “at no time”. The good diagnostic properties of the WHO-5 as a screening tool for depression and its high clinical validity have been demonstrated in various clinical studies (Topp et al., 2015).

A German short version (ZUF-8) (Schmidt et al., 1989) of the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire (CSQ) (Attkisson and Zwick, 1982) is used to measure intervention satisfaction. The ZUF consists of eight items, e.g. “How would you rate the quality of the treatment you received?” on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Excellent” to 4 = “Poor”. It has excellent internal consistency of α = 0.88–0.92 (Kriz et al., 2008). Number of completed modules is assessed and “per protocol” adherence is operationalized by the percentage of participants that completed at least 4 of the 5 modules 6 weeks after randomization (T1). Additionally, quantitative and qualitative data is collected on intervention acceptance using self-constructed items (e.g. “Which elements did you find particularly helpful?”).

The Inventory for the Assessment of Negative Effects of Psychotherapy (INEP) (Ladwig et al., 2014) assesses any changes experienced during or after the intervention in the personal, social and/or college environment and whether they are attributed to the psychotherapeutic intervention. An adapted subset of 12 items is used (e.g. “Since I attended StudiCare Procrastination I feel better (+3)… worse (−3)”).

2.8.3. Potential mediators

The Susceptibility to Temptation Scale (STS) (Steel, 2010) measures sensitivity to distractions and immediate gratification. This construct can foster procrastination because it can affect the ability to follow through on tasks. It consists of 11 items (e.g. “When a temptation is right before me, the craving can be intense”) and it is scored on a five-point Likert scale (1–5), with higher scores indicating greater difficulties with temptation. The STS correlates with the IPS at r = 0.69 and shows good internal consistency of α = 0.89 (Steel, 2010).

The General Self-Efficacy Scale (SWE) (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995) consists of 10 items to measure perceived self-efficacy (e.g. “I can always manage to solve difficult problems if I try hard enough.”). Items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 = “Not at all true” to 4 = “Exactly true”. The SWE has good internal consistency with Cronbach's α = 0.75–0.91 (Schwarzer, Mueller, & Greenglass, 1999). We also measure academic self-efficacy with the WIRKSTUD. It contains 7 items (e.g. “When I must prepare for exams, I often do not know how to handle the learning material.”) and is rated on a 4-point scale from 1 = “Not at all true” to 4 = “Exactly true”. It has demonstrated good internal consistency with Cronbach's α = 0.87 (Schwarzer, 1986).

2.8.4. Covariates

To investigate potential effect-modifying influences (Ebert et al., 2013), several sociodemographic as well as other variables are assessed: age, gender, nationality, marital status, study course, number of semesters, psychotherapy experience, use of other support offers and whether participants are on semester break or in examination period. The last two variables will also be assessed at T1 and T2.

The Credibility Expectancy Questionnaire (CEQ) (Devilly and Borkovec, 2000) is used to examine the influence of treatment expectations on outcomes. It consists of six items, e.g. “How much do you think your procrastination behavior will have improved at the end of the treatment period?”. Participants can respond on a 9-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “Not at all” to 9 = “Very much”. The CEQ has good internal consistency of α = 0.86 (Devilly and Borkovec, 2000).

2.9. Sample size estimation

The sample size for this RCT was determined a priori using G*Power 3.1.9.2 for the expected increased effectiveness of StudiCare Procrastination compared to WL on the primary outcome procrastination at post-assessment (T1). Empirical evidence suggests a medium to large effect of IMIs for procrastination (Rozental et al., 2015b). However, as this study is a low-threshold intervention for a non-clinical sample, a mean effect of d = 0.6 was expected. With a power of 1-ß = 0.9 and a significance level of α = 0.05 (two-tailed t-test), the sample size was calculated n = 60 subjects per group.

2.10. Statistical analyses

All analyses will be performed on an intention-to-treat basis. Procedures of imputation will be chosen based on patterns and mechanisms of missingness (e.g. by using multiple imputation). Additionally, per protocol analyses will be performed to examine the impact of drop-outs on study results. The significance level for all analyses will be p ≤ .05. To obtain the number of participants achieving reliable improvement in procrastination behavior (IPS), participants will be coded as responders and nonresponders according to the Reliable Change Index (RCI) for T1 and T2 (Jacobson and Truax, 1991). Participants will be defined symptom-free when scoring below the cut-off defined for the screening (<32 on IPS). We will investigate potential negative effects on individual level by calculating the number of participants that display a reliable symptom deterioration from T0 to T1 and T2 also using the RCI. Number needed to treat (NNT) will be calculated in order to determine the number of participants that have to be treated to cause one additional reliable improvement/symptom-free status compared to the control group (Altman, 1998; Cook and Sackett, 1995).

2.10.1. Clinical analysis

To analyze between-group effect sizes, standardized mean differences with 95% confidence intervals will be calculated for T1, T2 and T3. Regression analyses will be performed as primary method, using linear regressions for continuous outcomes and logistic regression for dichotomous outcomes. Based on data structure, regression analysis will be adjusted accordingly.

2.10.2. Moderator and mediator analysis

Analyzed variables will include the covariates and potential mediators described above. Depending on model complexity regression analysis or path models will be used.

3. Discussion

This randomized controlled trial aims to examine the effectiveness of a 5-week internet-based intervention for procrastination in college students compared to waitlist control group concerning the primary outcome procrastination and a number of secondary outcomes like anxiety and depression. It will add important results from a high-quality, adequately powered study to the sparse evidence base for CBT-based procrastination IMIs (Rozental et al., 2018a). We will also look at acceptability aspects such as intervention satisfaction, adherence and possible risks and side effects to further refine our intervention. Finally, we will investigate potential moderating and mediating variables on an exploratory level to gain preliminary insights on how and for whom exactly the intervention works.

A few limitations need to be taken into consideration. First, due to the nature of procrastination as well as due to relatively high dropout rates that are generally found in IMI studies (Christensen et al., 2009; Melville et al., 2010) attrition might become a problem. Potential adherence problems will be reduced by the fact that participants in the intervention group will be guided by e-coaches enhancing engagement and motivation and sending reminders (Baumeister et al., 2014; Fry and Neff, 2009). To further increase adherence, StudiCare Procrastination uses specific characteristics like goal setting and homework (Brouwer et al., 2011) as well as attractive, convincing design (Kelders et al., 2012) according to current insights into the active ingredients of IMIs (Domhardt et al., 2018). Second, within our study design we will not be able to track long term effects as we didn't want the waiting-list control group wait too long for the intervention. However, after post-assessment (6 weeks after randomization) we will have another 3-months follow-up measurement. As only three studies so far (to our knowledge) have had a follow-up period of >8 weeks (Rozental et al., 2018b; Rozental et al., 2017), this will contribute to our still limited knowledge on the stability of effects of procrastination IMIs. Lastly, we decided to use a waitlist control group. It has been argued that passive control groups might lead to overestimation of effects compared to psychological placebo or no treatment (Furukawa et al., 2014). However in our trial, participants in both groups will have access to treatment as usual and receive information on alternative treatment options such as student counselling or helplines. If StudiCare Procrastination proves to be effective compared to a waitlist control group, a future non-inferiority trial with an active control group could confirm and expand evidence for the effectiveness of this IMI.

There are also several strengths of this study, the first one concerning our recruitment strategy. We are able to reach students from many different colleges and study courses in Germany, Austria and Switzerland. The StudiCare framework offers recruitment possibilities at >15 cooperating colleges that send out circular emails to all their students on a regular basis, informing them about the various StudiCare online trainings (usually in the context of their student counselling or health management). In addition, participants will not receive any course credits our financial compensation. This gives us the unique opportunity to observe real-life demand and attractiveness of our interventions. Thinking of future long-term implementation and dissemination of StudiCare as well as generalizability of study results, this is very valuable information. A second strength is our comprehensive assessment. Although procrastination is not classified as a mental disorder, there are studies showing that procrastination can be correlated to generalized anxiety disorder (Stöber and Joormann, 2001) or rumination and depression (Flett et al., 2016). Other studies found procrastination to be linked to further negative outcomes such as higher stress, fatigue, illness susceptibility and worse performance in exams (Beutel et al., 2016; Höcker et al., 2013; Stead et al., 2010; Steel, 2007; Tice and Baumeister, 1997). We therefore deem it important to examine the effects of an intervention against procrastination from more than one angle and have included measures for depression, anxiety, stress and well-being. It has been shown that IMIs can have negative side effects (Boettcher et al., 2014; Rozental et al., 2014; Rozental et al., 2015a), but only one group of researchers have examined such effects for psychological interventions for procrastination so far (Rozental et al., 2018b; Rozental et al., 2015b). In our RCT, we will assess possible risks and side effects and contribute to our knowledge on the safety of such interventions. Finally, we will investigate potential moderators and mediators on an exploratory level. To our knowledge, only one study so far has examined moderators of the intervention effect of procrastination IMIs (Rozental et al., 2017), with no significant results. The knowledge of target groups and mechanisms of change can help enhance intervention effectiveness. Therefore, the results of this trial will contribute to our knowledge on how to treat procrastination. Although we will not be able to determine chronology of change because our design does not allow several assessment points, results will provide important preliminary information for future trials specifically designed for the investigation of mechanisms of change (Kraemer et al., 2002).

4. Conclusions

In this study protocol, we describe the design of a randomized controlled trial that aims to evaluate the acceptability and effectiveness of an internet-based intervention for procrastination specifically designed for college students. Results will contribute to the scarce evidence for CBT-based procrastination interventions delivered via the internet. If it proves to be effective, StudiCare Procrastination could provide a low-threshold, cost-efficient way to help the multitude of students suffering from problems caused by procrastination behavior.

Abbreviations

- CBT

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

- CONSORT

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- DRKS

Deutsches Register Klinischer Studien (German clinical studies trial register)

- IG

intervention group

- IMI

internet- and mobile-based intervention

- ITT

intention-to-treat

- RCT

randomized controlled trial

- WHO

World Health Organization

- WL

waitlist control group

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All study procedures have been approved by the ethics committee of Ulm University (application no. 47/18). Participants will receive written information on study conditions, data security, voluntariness of participation and the right to leave the study at all times. To confirm understanding of the above, written consent is obtained from all participants prior to study entry. Data collection will be pseudonymized and data will only be accessed by authorized study personnel obliged to secrecy. After data collection is completed, personalized information will be deleted and all data will be completely anonymized.

Access to data and availability

All principal investigators will be given full access to the data sets. Data set will be stored on password-protected servers of Ulm University with restricted access. External researches may get access to the final trial dataset on request depending on to be specified data security and data exchange regulation agreements. To ensure confidentiality, data dispersed to any investigator or researcher will be blinded of any identifying participant information.

Dissemination

Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented on international conferences.

Competing interests

AK, PA and HB were involved in the development of StudiCare Procrastination or its predecessor versions. HB reports to have received consultancy fees and fees for lectures/workshops from chambers of psychotherapists and training institutes for psychotherapists in the e-mental-health context. AK has received fees for lectures/workshops from chambers of psychotherapists and health insurance companies. DDE reports to have received consultancy fees/served in the scientific advisory board from several companies such as Minddistrict, Lantern, Schoen Kliniken and German health insurance companies. He is stakeholder of the Institute for health training online (GET.ON), which aims to implement scientific findings related to digital health interventions into routine care.

Funding

The project is funded by BARMER, a major health care insurance company in Germany. BARMER had no role in study design, decision to publish or preparation of this manuscript. BARMER will not be involved in data collection, analyses, decision to publish or preparation of future papers regarding the StudiCare project.

Authors contributions

AK, DDE and HB initiated this study. AK, DDE and HB contributed to the design of this study. PA adapted and enhanced intervention content and design. AK is responsible for recruitment. AK and PA are responsible for the administration of study participants. AK and PA wrote the draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the further writing of the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Elena Flügel, Theresa Mittl, Denise Tempel, Jurij von Randow and Tanja Maier for their contributions to former versions of StudiCare Procrastination. Thanks to Mathias Harrer for taking care of the StudiCare website and to Fanny Kählke for supporting the establishment of the study administration and assessment processes. Moreover we like to thank our study assistants for their support concerning assessment procedures and study administration processes. Special thanks to all cooperating colleges in Germany, Austria and Switzerland for regularly informing their students about the StudiCare interventions.

Contributor Information

Ann-Marie Küchler, Email: ann-marie.kuechler@uni-ulm.de.

Patrick Albus, Email: patrick.albus@uni-ulm.de.

David Daniel Ebert, Email: d.d.ebert@vu.nl.

Harald Baumeister, Email: harald.baumeister@uni-ulm.de.

References

- Achtziger A., Gollwitzer P.M. Rubicon model of action phases. In: Baumeister R.F., Vohs K.D., editors. Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. 2nd ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2007. pp. 769–771. [Google Scholar]

- Altman D.G. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998;317(7168):1309–1312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Carlbring P., Berger T., Almlöv J., Cuijpers P. What makes internet therapy work? Cognitive Behaviour Therapy. 2009;38(sup1):55–60. doi: 10.1080/16506070902916400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson G., Cuijpers P., Carlbring P., Riper H., Hedman E. Guided internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):288–295. doi: 10.1002/wps.20151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariely D., Wertenbroch K. Procrastination, deadlines, and performance: self-control by precommitment. Psychol. Sci. 2002;13(2):219–224. doi: 10.1111/1467-9280.00441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attkisson C.C., Zwick R. The client satisfaction questionnaire. Psychometric properties and correlations with service utilization and psychotherapy outcome. Eval. Program Plann. 1982;5(3):233–237. doi: 10.1016/0149-7189(82)90074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister H., Reichler L., Munzinger M., Lin J. The impact of guidance on internet-based mental health interventions — a systematic review. Internet Interv. 2014;1(4):205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Beutel M.E., Klein E.M., Aufenanger S., Brähler E., Dreier M., Müller K.W.…Wölfling K. Procrastination, distress and life satisfaction across the age range - a German representative community study. PLoS One. 2016;11(2) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher J., Rozental A., Andersson G., Carlbring P. Side effects in internet-based interventions for social anxiety disorder. Internet Interv. 2014;1(1):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer W., Kroeze W., Crutzen R., De Nooijer J., De Vries N.K., Brug J., Oenema A. Which intervention characteristics are related to more exposure to internet-delivered healthy lifestyle promotion interventions? A systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011;13(1):23–41. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlbring P., Andersson G., Cuijpers P., Riper H., Hedman-Lagerlöf E. Internet-based vs. face-to-face cognitive behavior therapy for psychiatric and somatic disorders: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2018;47(1):1–18. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2017.1401115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan A.W., Tetzlaff J.M., Altman D.G., Laupacis A., Gøtzsche P.C., Krleža-Jerić K.…Moher D. SPIRIT 2013 statement: defining standard protocol items for clinical trials. Ann. Intern. Med. 2013;158(3):200–209. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christensen H., Griffiths K.M., Farrer L. Adherence in internet interventions for anxiety and depression. J. Med. Internet Res. 2009;11 doi: 10.2196/jmir.1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S., Williamson G. Perceived stress in a probability sample of the United States. In: Spacapan S., Oskamp S., editors. The Social Psychology of Health. Sage Publications; Newbury Park, CA: 1988. pp. 31–68. [Google Scholar]

- Cook R.J., Sackett D.L. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ. 1995;310(6977):452–454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day V., Mensink D., O'Sullivan M. Patterns of academic procrastination. J. Coll. Read. Learn. 2000;30(2):120–134. [Google Scholar]

- Devilly G.J., Borkovec T.D. Psychometric properties of the credibility/expectancy questionnaire. J. Behav. Ther. Exp. Psychiatry. 2000;31(2):73–86. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7916(00)00012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domhardt M., Geßlein H., von Rezori R.E., Baumeister H. Internet- and mobile-based interventions for anxiety disorders: a meta-analytic review of intervention components. Depress. Anxiety. 2018:1–12. doi: 10.1002/da.22860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D.D., Gollwitzer M., Riper H., Cuijpers P., Baumeister H., Berking M. For whom does it work? Moderators of outcome on the effect of a transdiagnostic internet-based maintenance treatment after inpatient psychotherapy: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15(10):1–17. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert D.D., Franke M., Kählke F., Küchler A.-M., Bruffaerts R., Mortier P.…Baumeister H. Increasing intentions to use mental health services among university students. Results of a pilot randomized controlled trial within the WHO World Mental Health International College Student Initiative (under review) Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2018:e1754. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert M., Ebert D.D., Lehr D., Sieland B., Berking M. Does SMS-support make a difference? Effectiveness of a two-week online-training to overcome procrastination. A randomized controlled trial. Front. Psychol. 2018;9:1–13. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1973. Humanistic Psychotherapy. The Rational-Emotive Approach. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis A., Knaus W.J. Institute for Rational Living; New York: 1977. Overcoming Procrastination: How to Think and Act Rationally in Spite of life's Inevitable Hassles. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari J.R., O'Callaghan J., Newbegin I. Prevalence of procrastination in the United States, United Kingdom, and Australia: arousal and avoidance delays among adults. N. Am. J. Psychol. 2005;7(1):1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Fleischmann R.J., Harrer M., Zarski A.-C., Baumeister H., Lehr D., Ebert D.D. Patients' experiences in a guided internet- and app-based stress intervention for college students: a qualitative study. Internet Interv. 2018;12:130–140. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2017.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flett A.L., Haghbin M., Pychyl T.A. Procrastination and depression from a cognitive perspective: an exploration of the associations among procrastinatory automatic thoughts, rumination, and mindfulness. J. Ration. Emot. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2016;34(3):169–186. [Google Scholar]

- Fry J.P., Neff R.A. Periodic prompts and reminders in health promotion and health behavior interventions: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2009;11(2) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furukawa T.A., Noma H., Caldwell D.M., Honyashiki M., Shinohara K., Imai H.…Churchill R. Waiting list may be a nocebo condition in psychotherapy trials: a contribution from network meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2014;130(3):181–192. doi: 10.1111/acps.12275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gieselmann A., Pietrowsky R. Treating procrastination chat-based versus face-to-face: an RCT evaluating the role of self-disclosure and perceived counselor's characteristics. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2016;54:444–452. [Google Scholar]

- Glick D.M., Orsillo S.M. An investigation of the efficacy of acceptance-based behavioral therapy for academic procrastination. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2015;144(2):400–409. doi: 10.1037/xge0000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollwitzer P.M., Brandstätter V. Implementation intentions and effective goal pursuit. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1997;73(1):186–199. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.5.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häfner A., Oberst V., Stock A. Avoiding procrastination through time management: an experimental intervention study. Educ. Stud. 2014;40(3):352–360. [Google Scholar]

- Harrer M., Adam S.H., Fleischmann R.J., Baumeister H., Auerbach R., Bruffaerts R.…Ebert D.D. Effectiveness of an internet- and app-based intervention for college students with elevated stress: randomized controlled trial. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20(4):1–16. doi: 10.2196/jmir.9293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höcker A., Engberding M., Haferkamp R., Rist F. Wirksamkeit von arbeitszeitrestriktion in der prokrastinationsbehandlung. Verhaltenstherapie. 2012;1:9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Höcker A., Engberding M., Rist F. Hogrefe Verlag; Göttingen: 2013. Prokrastination: Ein Manual zur Behandlung des pathologischen Aufschiebens. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson N.S., Truax P. Clinical significance: a statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 1991;59(1):12–19. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelders S.M., Kok R.N., Ossebaard H.C., Van Gemert-Pijnen J.E.W.C. Persuasive system design does matter: a systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2012;14(6) doi: 10.2196/jmir.2104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H.C., Wilson T., Fairburn C.G., Argas W.S. Mediators and moderators of treatment effects in randomized clinical trials. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2002;59:877–883. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.10.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriz D., Nübling R., Steffanowski A., Rieger J., Schmidt J. Patientenzufriedenheit: Psychometrische Reanalyse des ZUF-8. DRV-Schriften. 2008;77:84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K., Spitzer R.L. The PHQ-9: a new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr. Ann. 2002;32(9):509–515. [Google Scholar]

- Ladwig I., Rief W., Nestoriuc Y. Welche Risiken und Nebenwirkungen hat Psychotherapie? - Entwicklung des Inventars zur Erfassung Negativer Effekte von Psychotherapie (INEP) Verhaltenstherapie. 2014;24(4):252–263. [Google Scholar]

- Leyland A., Rowse G., Emerson L.-M. Experimental effects of mindfulness inductions on self-regulation: systematic review and meta-analysis. Emotion. 2019;19(1):108–122. doi: 10.1037/emo0000425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas C.A., Berking M. Reducing procrastination using a smartphone-based treatment program: a randomized controlled pilot study. Internet Interv. 2018;12(June 2017):83–90. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2017.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahasneh A.M., Bataineh O.T., Al-Zoubi Z.H. The relationship between academic procrastination and parenting styles among Jordanian Undergraduate University students. Open Psychol. J. 2016;9(1):25–34. [Google Scholar]

- Melville K.M., Casey L.M., Kavanagh D.J. Dropout from internet-based treatment for psychological disorders. Br. J. Clin. Psychol. 2010;5 doi: 10.1348/014466509X472138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr D.C., Cuijpers P., Lehman K. Supportive accountability: a model for providing human support to enhance adherence to eHealth interventions. J. Med. Internet Res. 2011;13(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onwuegbuzie A.J. Academic Procastination and statistics anxiety. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 2004;29(1):3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Özer B.U., Demir A., Ferrari J.R. Exploring academic procrastination among Turkish students: possible gender differences in prevalence and reasons. J. Soc. Psychol. 2009;149(2):241–257. doi: 10.3200/SOCP.149.2.241-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paganini S., Teigelkötter W., Buntrock C., Baumeister H. Economic evaluations of internet- and mobile-based interventions for the treatment and prevention of depression: a systematic review. J. Affect. Disord. 2018;225:733–755. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Proudfoot J., Klein B., Barak A., Carlbring P., Cuijpers P., Lange A.…Andersson G. Establishing guidelines for executing and reporting internet intervention research. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2011;40(2):82–97. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2011.573807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pychyl T.A., Lee J.M., Thibodeau R., Blunt A. Five days of emotion: an experience sampling study of undergraduate student procrastination. J. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2000;15:239–254. [Google Scholar]

- Rozental A., Carlbring P. Understanding and treating procrastination: a review of a common self-regulatory failure. Psychology. 2014;5(13):1488–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Rozental A., Andersson G., Boettcher J., Ebert D.D., Cuijpers P., Knaevelsrud C.…Carlbring P. Consensus statement on defining and measuring negative effects of internet interventions. Internet Interv. 2014;1(1):12–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rozental A., Boettcher J., Andersson G., Schmidt B., Carlbring P. Negative effects of internet interventions: a qualitative content analysis of patients' experiences with treatments delivered online. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2015;44:1–14. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2015.1008033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental A., Forsell E., Svensson A., Andersson G. Internet-based cognitive-behavior therapy for procrastination: a randomized controlled trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2015;83(4):808–824. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental A., Forsell E., Svensson A., Andersson G., Carlbring P. Overcoming procrastination: one-year follow-up and predictors of change in a randomized controlled trial of internet-based cognitive behavior therapy. Cogn. Behav. Ther. 2017;46(3):177–195. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2016.1236287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental A., Bennett S., Forsström D., Ebert D.D., Shafran R., Andersson G., Carlbring P. Targeting procrastination using psychological treatments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front. Psychol. 2018;9 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozental A., Forsström D., Lindner P., Nilsson S., Mårtensson L., Rizzo A.…Carlbring P. Treating procrastination using cognitive behavior therapy: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial comparing treatment delivered via the internet or in groups. Behav. Ther. 2018;49(2):180–197. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2017.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt J., Lamprecht F., Wittmann W.W. Zufriedenheit mit der stationären Versorgung. Entwicklung eines Fragebogens und erste Validitätsuntersuchungen [satisfaction with inpatient care: development of a questionnaire and first validity assessments] PPmP: Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik, Medizinische Psychologie. 1989;39(7):248–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R. Zentrale Universitäts-Druckerei; Berlin: 1986. Skalen zur Befindlichkeit und Persönlichkeit. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R., Jerusalem M. Generalized Self-Efficacy scale. In: Weinman J., Wright S., Johnston M., editors. Measures in health psychology: A user’s portfolio. Causal and control beliefs. NFER-Nelson; UK: 1995. pp. 35–37. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer R., Mueller J., Greenglass E. Assessment of perceived general self-efficacy on the internet: data collection in cyberspace. Anxiety, Stress and Coping. 1999;12(2):145–161. [Google Scholar]

- Schulz, K. F., Altman, D. G., Moher, D., & CONSORT Group. (2010). CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), 340. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Spitzer R.L., Kroenke K., Williams J.B., Löwe B. The GAD-7. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch. Intern. Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stead R., Shanahan M.J., Neufeld R.W.J. “I'll go to therapy, eventually”: procrastination, stress and mental health. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010;49(3):175–180. [Google Scholar]

- Steel P. The nature of procrastination: a meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychol. Bull. 2007;133(1):65–94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steel P. Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: do they exist? Personal. Individ. Differ. 2010;48(8):926–934. [Google Scholar]

- Steel P. Allen & Unwin; Australia: 2011. The Procrastination Equation: How to Stop Putting Stuff off and Start Getting Things Done. [Google Scholar]

- Steel P., König C.J. Integrating theories of motivation. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006;31(4):889–913. [Google Scholar]

- Stöber J., Joormann J. Worry, procrastination, and perfectionism: differentiating amount of worry, pathological worry, anxiety, and depression. Cogn. Ther. Res. 2001;25(1):49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Svartdal F., Pfuhl G., Nordby K., Foschi G., Klingsieck K.B., Rozental A.…Rebkowska K. On the measurement of procrastination: comparing two scales in six European countries. Front. Psychol. 2016;7:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tice D.M., Baumeister R.F. Longitudinal study of procrastination, performance, stress, and health: the costs and benefits of dawdling. Psychol. Sci. 1997;8(6):454–458. [Google Scholar]

- Topp C.W., Østergaard S.D., Søndergaard S., Bech P. The WHO-5 well-being index: a systematic review of the literature. Psychother. Psychosom. 2015;84(3):167–176. doi: 10.1159/000376585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuckman B.W., Schouwenburg H.C. Behavioral interventions for reducing procrastination among university students. In: Schouwenburg H.C., Lay C.H., Pychyl T.A., Ferrari J.R., editors. Counseling the Procrastinator in Academic Settings. American Psychological Association; Washington (DC): 2004. pp. 91–103. [Google Scholar]

- van Eerde W., Klingsieck K.B. Overcoming procrastination? A meta-analysis of intervention studies. Educ. Res. Rev. 2018;25:73–85. [Google Scholar]

- Warttig S.L., Forshaw M.J., South J., White A.K. New, normative, English-sample data for the short form perceived stress scale (PSS-4) J. Health Psychol. 2013;18(12):1617–1628. doi: 10.1177/1359105313508346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Regional Office for Europe, P, Unit, R . 1998. World Health Organization Info Package: Mastering Depression in Primary Care. (Frederiksborg) [Google Scholar]