Visual Abstract

Keywords: Plant-based diet indices; vegetarian diet index; chronic kidney disease; kidney function; glomerular filtration rate; Proportional Hazards Models; Follow-Up Studies; Diet, Vegetarian; Diet; Renal Insufficiency, Chronic; kidney; Atherosclerosis

Abstract

Background and objectives

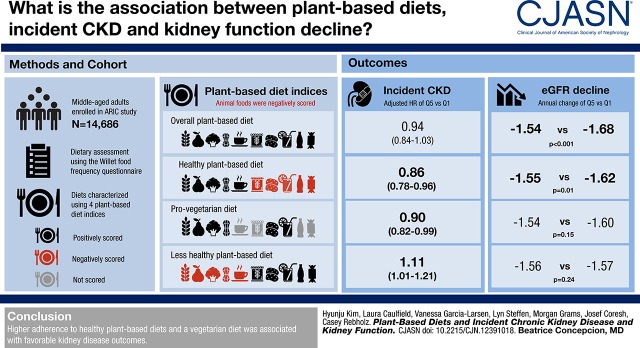

The association between plant-based diets, incident CKD, and kidney function decline has not been examined in the general population. We prospectively investigated this relationship in a population-based study, and evaluated if risk varied by different types of plant-based diets.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Analyses were conducted in a sample of 14,686 middle-aged adults enrolled in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Diets were characterized using four plant-based diet indices. In the overall plant-based diet index, all plant foods were positively scored; in the healthy plant-based diet index, only healthful plant foods were positively scored; in the provegetarian diet, selected plant foods were positively scored. In the less healthy plant-based diet index, only less healthful plant foods were positively scored. All indices negatively scored animal foods. We used Cox proportional hazards models to study the association with incident CKD and linear mixed models to examine decline in eGFR, adjusting for confounders.

Results

During a median follow-up of 24 years, 4343 incident CKD cases occurred. Higher adherence to a healthy plant-based diet (HR comparing quintile 5 versus quintile 1 [HRQ5 versus Q1], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.78 to 0.96; P for trend =0.001) and a provegetarian diet (HRQ5 versus Q1, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82 to 0.99; P for trend =0.03) were associated with a lower risk of CKD, whereas higher adherence to a less healthy plant-based diet (HRQ5 versus Q1, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.21; P for trend =0.04) was associated with an elevated risk. Higher adherence to an overall plant-based diet and a healthy plant-based diet was associated with slower eGFR decline. The proportion of CKD attributable to lower adherence to healthy plant-based diets was 4.1% (95% CI, 0.6% to 8.3%).

Conclusions

Higher adherence to healthy plant-based diets and a vegetarian diet was associated with favorable kidney disease outcomes.

Introduction

Plant-based diets consist of predominantly plant foods and a low intake of animal foods (1,2). Research has shown that plant-based diets are associated with lower risk of obesity, type 2 diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease (3–6).

Emerging evidence suggests that risk of chronic conditions varies by types of plant-based diets. In a study of nurses and health professionals, plant-based diets high in nutrient-dense plant foods and low in animal foods and less healthful plant foods (high in refined carbohydrates) were associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes and coronary heart disease. In contrast, plant-based diets high in less healthful plant foods were associated with a higher risk of these clinical outcomes (7,8).

Studies suggest that plant-rich diets may be associated with a lower risk of CKD. Higher adherence to Mediterranean diets (high in fruits, vegetables, cereals, legumes, and fish) was associated with lower CKD incidence in a multiethnic cohort (9). Similarly, studies of young and middle-aged adults in the United States found that those with higher adherence to the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet (high in fruits, vegetables, legumes, nuts, and low-fat dairy) had a lower risk of incident CKD (10,11). A recent study examining dietary sources of protein and CKD found that, when one serving of red and processed meat was replaced with plant proteins, the risk of CKD was significantly lower (12). However, important questions remain regarding whether an overall plant-based diet is associated with a lower risk of CKD, and if diets high in less healthy plant foods have adverse associations.

In addition to these gaps, long-term follow-up studies assessing the association between plant-based diets and changes in kidney function have been lacking. Previous studies of vegetarian diets and kidney function were conducted in patients with CKD or those who are at risk of developing CKD (hypertension, diabetes), and are limited in that they had relatively short follow-up periods (13–17). There has been a lack of research on healthy dietary patterns and incident CKD.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the associations between plant-based diets and incident CKD, and to examine changes in kidney function over 20 years in a general population. We used four established plant-based diet scores to assess if CKD risk and kidney function decline varied by different types of plant-based diets (7,8,18).

Materials and Methods

Study Design

The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study is a community-based cohort of 15,792 middle-aged adults (45–64 years of age), predominantly black and white men and women (19). Participants were enrolled into the ARIC study from 1987 to 1989 in four United States communities: Washington County, Maryland; Forsyth County, North Carolina; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Jackson, Mississippi. Participants returned for follow-up study visits in 1990–1992 (visit 2), 1993–1995 (visit 3), 1996–1998 (visit 4), 2011–2013 (visit 5), and 2016–2017 (visit 6). The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board at each study site, and all participants provided informed consent.

Study Population

We excluded participants with implausibly low or high total energy intake (women: <500 or >3500 kcal, men: <700 or >4500 kcal, n=192), and missing information on dietary intake (n=24). We then excluded those whose race/ethnicity was other than black or white (n=46), and black in Minnesota (n=32), and black in Washington County (n=22), those with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or missing eGFR measurement at baseline (n=354), and those with missing covariates (n=436). The final analytic sample was 14,686.

Dietary Assessment

At baseline and visit 3, trained interviewers administered a modified semiquantitative Willett food frequency questionnaire to assess participants’ usual intake of foods and beverages (20,21). Details appear in the Supplemental Material.

Plant-Based Diet Scores

We constructed an overall plant-based diet index, a healthy plant-based diet index, a less healthy plant-based diet index, and a provegetarian diet index on the basis of responses on the food frequency questionnaire. Details on differences between these indices, and creation of the scores are in the Supplemental Material and Table 1 (7,8,22).

Table 1.

Classification of food items into food groups for creation of the plant-based diet scoresa

| Food Groups | Food Items | Overall Plant-Based Diet Index | Healthy Plant-Based Diet Index | Less Healthy Plant-Based Diet Index | Provegetarian Diet Index |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant foodsb | |||||

| Whole grains | Cooked cereals such as oatmeal, grits, cream of wheat, dark or whole grain bread | Positive | Positive | Reverse | Positivec |

| Fruits | Apples, pears, oranges, peaches, apricots, plums, bananas, other fruits | Positive | Positive | Reverse | Positive |

| Vegetables | Broccoli, cabbage, cauliflower, brussels sprouts, carrots, corn, spinach, collards, or other greens, dark yellow, winter squash such as acorn, butternut, sweet potatoes, tomatoes | Positive | Positive | Reverse | Positive |

| Nuts | Peanut butter, nuts | Positive | Positive | Reverse | Positive |

| Legumes | String beans, green beans, baked beans or lentils (pinto, blackeye, baked beans), peas or lima beans | Positive | Positive | Reverse | Positive |

| Tea and coffee | Coffee, tea (iced or hot) | Positive | Positive | Reverse | Not scored |

| Refined grains | Biscuits, cornbread, cold breakfast cereal, white bread, pasta, rice | Positive | Reverse | Positive | Positivec |

| Potatoes | Potato or corn chips, French-fried potatoes, mashed potatoes | Positive | Reverse | Positive | Positive |

| Fruit juices | Orange juice, grapefruit juice | Positive | Reverse | Positive | Not scored |

| Sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages | Low-calorie soft drinks (any diet Coke, diet Pepsi), Regular soft drinks (Coke, Pepsi, 7-Up, ginger ale), fruit-flavored punch or noncarbonated beverages | Positive | Reverse | Positive | Not scored |

| Sweets and desserts | Chocolate bars or pieces, candy without chocolate, pie homemade from scratch, pie (ready-made or from mix), donuts, cake or brownie, cookies, Danish pastry, sweet roll, coffee cake, croissant | Positive | Reverse | Positive | Not scored |

| Animal foods | |||||

| Animal fat | Butter added to food or bread, butter used for cooking | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse |

| Dairy | Skim or low-fat milk, whole milk, yogurt, ice cream, cottage cheese or ricotta cheese, other cheese | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse |

| Eggs | Eggs | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse |

| Fish or seafood | Canned tuna; dark meat fish, such as salmon, mackerel, swordfish, sardines, bluefish; other fish, such as cod, perch, catfish, shrimp, lobster, scallops | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse |

| Meat | Chicken or turkey without skin, chicken or turkey with skin, hamburgers, hot dogs, processed meats (sausage, salami, bologna), bacon, beef, pork, or lamb as a sandwich or mixed dish, beef, pork, or lamb as a main dish, steak, roast, ham, liver | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse |

| Miscellaneous animal foods | Home-fried food, such as any meats, poultry, fish, shrimp | Reverse | Reverse | Reverse | Not scored |

Food categorization scheme is similar to previous publications (7,8,22). Positive indicates that higher consumption of this food group received higher scores. Reverse indicates that higher consumption of this food group received lower scores.

In the overall, healthy, and less healthy plant-based diet indices, whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, tea, and coffee were considered “healthy plant foods.” Refined grains, potatoes, fruit juices, sugar-sweetened and artificially sweetened beverages, and sweets and desserts were considered “less healthy plant foods.” The provegetarian diet index did not differentiate plant foods as healthy or less healthy.

In the provegetarian diet index, consumption of whole grains and refined grains was aggregated as the “grains” food group.

For the overall plant-based diet index, higher intake of healthy and less healthy plant foods received higher scores. For the healthy plant-based diet index, higher intake of only the healthy plant foods received higher scores. For the less healthy plant-based diet index, higher intake of only the less healthy plant foods received higher scores. For the provegetarian diet index, higher intake of selected plant foods received higher scores. For all indices, higher intake of animal foods received lower scores. All of the plant-based diet scores were divided into quintiles for analyses.

Outcome Assessment

Details on creatinine measurements are in the Supplemental Material. eGFR was calculated using the 2009 CKD Epidemiology Collaboration equation (23). We used a composite definition to ascertain incident CKD, which was defined as meeting one of the following categories: (1) eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, accompanied by ≥25% eGFR decline at any study visits relative to baseline; (2) kidney-disease related hospitalizations or deaths according to codes from the International Classification of Disease Ninth and Tenth Revisions, identified through annual surveillance and linkage to the National Death Index; and (3) ESKD, defined as either dialysis or transplantation, and identified through linkage to the US Renal Data System registry from baseline to December 31, 2016.

For analyses of changes in kidney function, we imputed an eGFR value of 15 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at the time of ESKD onset to address informative censoring.

Covariate Assessment

Details appear in the Supplemental Material.

Statistical Analyses

We examined the baseline characteristics of the sample and nutritional characteristics of the diet according to quintiles of plant-based diet scores using chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables.

To examine the associations between plant-based diets and incident CKD, we constructed three nested Cox proportional hazards models using length of follow-up time as the time metric. To delineate eGFR trajectories according to quintiles of plant-based diet scores, we used linear mixed models with random intercepts and slopes, using an interaction term between categorical variables of plant-based diet scores and time. For both analyses, we used the same covariates. Model 1 adjusted for total energy intake, age, sex, and a combined term for race and study center. Model 2 additionally adjusted for socioeconomic status and health behaviors. Model 3 additionally adjusted for potential mediators. Details appear in the Supplemental Material. We tested for a linear trend using an ordinal variable of plant-based diet scores by assigning the median value within each quintile. We estimated the population attributable risk percentages of a hypothetical scenario in which all participants changed their diets to the top two quintiles of the four indices (24). Then, we tested for effect modification by sex, race/ethnicity, baseline weight status, and diabetes status.

We considered the main results to be model 2 (without potential mediators). In addition, we included components of plant-based diet scores (quintiles of healthy plant food, less healthy plant food, and animal food intake defined from the overall plant-based diet index; and quintiles of plant food and animal food intake from provegetarian diet index) simultaneously in model 3, instead of the scores. As sensitivity analyses, we (1) modeled individual food components within the plant-based diet indices simultaneously, (2) reclassified string or green beans as vegetables, and (3) considered margarine as part of the scores (vegetable oil) instead of a covariate. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Baseline Characteristics and Nutritional Characteristics

The overall plant-based diet index ranged from 22 to 74, the healthy plant-based diet index ranged from 18 to 75, the less healthy plant-based diet index ranged from 17 to 76, and the provegetarian diet index ranged from 14 to 54. Those in the highest quintiles of overall plant-based diet, healthy plant-based diet, and provegetarian diet were more likely to be women, white, older, high school graduates, and physically active; and less likely to be obese and current smokers than those in the lowest quintiles (all P<0.05; Table 2; Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Those in the highest quintiles of these indices were less likely to have diabetes or hypertension at baseline, but more likely to use lipid-lowering medication and to have lower eGFR (all P<0.05). Those in the highest quintiles of these indices had higher intake of healthy plant foods (9.1–10.4 servings per day), carbohydrates, fiber, and almost all micronutrients, and lower intake of animal foods (3.6–4.2 servings), dietary acid load, saturated fat, and cholesterol (all P<0.05).

Table 2.

Selected baseline characteristics and nutritional characteristics by quintiles of healthy plant-based diet index in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities studya

| Characteristic | Healthy Plant-Based Diet Index, n=14,686 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quintile 1, n=3067 | Quintile 2, n=3214 | Quintile 3, n=2554 | Quintile 4, n=3407 | Quintile 5, n=2444 | |

| Median score (range) | 43 (18–45) | 48 (46–49) | 51 (50–52) | 55 (53–57) | 61 (58–75) |

| Women, %b | 48 | 54 | 57 | 59 | 61 |

| Black, %b | 29 | 28 | 25 | 23 | 19 |

| Age, yrb | 53 (6) | 54 (6) | 54 (6) | 54 (6) | 55 (6) |

| High school graduate, %b | 71 | 75 | 78 | 79 | 84 |

| BMI categoryb | |||||

| Normal weight, <25 kg/m2 | 29 | 30 | 34 | 35 | 40 |

| Overweight, 25–<30 kg/m2 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 40 | 39 |

| Obese, ≥30 kg/m2 | 32 | 30 | 27 | 25 | 22 |

| Current smoker, %b | 29 | 28 | 28 | 23 | 23 |

| Physical activity indexb | 2.3 (0.7) | 2.4 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.5 (0.8) | 2.6 (0.8) |

| Alcohol, g/wk | 39 (86) | 43 (93) | 45 (91) | 44 (101) | 46 (101) |

| Fasting glucose, mg/dlb | 109 (38) | 109 (39) | 108 (37) | 109 (43) | 106 (37) |

| Diabetes, %b | 12 | 12 | 11 | 11 | 10 |

| Hypertension, % | 35 | 36 | 34 | 33 | 30 |

| Lipid-lowering medication, %b | 2 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 mb | 104 (15) | 103 (15) | 103 (14) | 103 (14) | 102 (13) |

| Food and nutrient intake per day | |||||

| Healthy plant foodsb,c | 4.6 (2.4) | 5.7 (2.2) | 6.8 (2.4) | 8.0 (2.5) | 10.4 (2.9) |

| Less healthy plant foodsb,c | 5.9 (2.8) | 5.0 (2.3) | 4.9 (2.5) | 4.8 (2.4) | 4.4 (2.1) |

| Animal foodsb,c | 4.8 (2.3) | 4.3 (2.0) | 4.2 (1.9) | 4.2 (1.9) | 4.2 (1.9) |

| Total energy, kcalb | 1568 (578) | 1524(548) | 1582 (574) | 1661 (552) | 1793 (514) |

| Total protein, % of energyb | 17.7 (3.6) | 18.1 (3.7) | 18.3 (3.8) | 18.4 (3.9) | 18.7 (3.7) |

| Animal protein, % of energyb | 13.9 (3.7) | 13.9 (3.8) | 13.8 (3.9) | 13.7 (4.0) | 13.5 (4.0) |

| Plant protein, % of energyb | 3.9 (0.8) | 4.2 (0.9) | 4.5 (1.0) | 4.7 (1.1) | 5.2 (1.3) |

| Carbohydrates, % of energyb | 46.4 (7.7) | 48.1 (8.3) | 49.0 (8.3) | 50.6 (8.4) | 52.7 (8.5) |

| Total fat, % of energyb | 35.3 (5.3) | 33.3 (5.6) | 32.3 (5.8) | 31.0 (6.0) | 29.2 (6.1) |

| Saturated fat, % of energyb | 13.0 (2.4) | 12.1 (2.5) | 11.6 (2.4) | 11.1 (2.6) | 10.2 (2.5) |

| MUFA, % of energyb | 13.9 (2.3) | 13.0 (2.5) | 12.6 (2.6) | 12.0 (2.7) | 11.2 (2.8) |

| PUFA, % of energyb | 5.1 (1.1) | 4.9 (1.2) | 4.9 (1.2) | 4.8 (1.2) | 4.8 (1.3) |

| Fiber, g/1000 kcalb | 8.4 (2.3) | 9.9 (2.9) | 10.9 (3.1) | 12.1 (3.5) | 14.1 (4.0) |

| Cholesterol, mg/1000 kcalb | 178.1 (56.9) | 163.7 (55.0) | 154.9 (50.7) | 144.6 (46.4) | 129.8 (42.3) |

| Sodium, mg/1000 kcalb | 926.2 (168) | 925.7 (180) | 918.7 (177) | 932.2 (183) | 946.7 (189) |

| Phosphorus, mg/1000 kcalb | 641.5 (143) | 661.6 (144) | 677.1 (144) | 693.3 (148) | 719.7 (143) |

| Calcium, mg/1000 kcalb | 381.4 (153) | 397.7 (154) | 409.5 (164) | 427.3 (163) | 453.8 (169) |

| Potassium, mg/1000 kcalb | 1481 (320) | 1615 (346) | 1698 (362) | 1771 (364) | 1900 (357) |

| Magnesium, mg/1000 kcalb | 136.9 (28.8) | 152.8 (32.2) | 162.8 (32.9) | 171.7 (35.0) | 186.8 (34.7) |

| Iron, mg/1000 kcalb | 6.6 (1.8) | 7.0 (2.1) | 7.2 (2.2) | 7.4 (2.3) | 7.6 (2.1) |

| Vitamin A, IU/1000 kcalb | 4343 (2579) | 5401 (3403) | 6088 (3721) | 6855 (3957) | 8234 (5203) |

| Vitamin C, mg/1000 kcalb | 69.1 (36.9) | 76.0 (39.7) | 79.6 (40.7) | 84.5 (41.9) | 90.7 (42.0) |

| Folate, μg/1000 kcalb | 134.8 (46.0) | 146.1 (49.7) | 153.9 (51.0) | 162.2 (53.3) | 174.3 (52.2) |

| Vitamin B12, μg/1000 kcalb | 4.7 (2.3) | 4.8 (2.3) | 4.7 (2.2) | 4.5 (2.1) | 4.2 (2.0) |

| Zinc, mg/1000 kcalb | 6.7 (1.6) | 6.7 (1.6) | 6.7 (1.5) | 6.7 (1.5) | 6.6 (1.4) |

| PRAL, mEq/db,d | 15.0 (12.3) | 12.1 (12.9) | 11.5 (13.4) | 11.7 (13.6) | 12.0 (14.5) |

| NEAP, mEq/db,e | 55.4 (13.9) | 51.1 (13.9) | 48.5 (12.9) | 46.4 (11.8) | 43.4 (11.2) |

BMI, body mass index; MUFA, monounsaturated fatty acids; NEAP; net endogenous acid production; PRAL, potential renal acid load; PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids.

Values are means (SDs) for continuous variables and % for categorical variables.

Indicates a statistical difference by quintiles of healthy plant-based diet index (P<0.05).

Food intakes are expressed as servings per day.

Potential renal acid load =0.49×protein (g)+0.037× phosphorus (mg)−0.021× potassium (mg)−0.026× magnesium (mg)−0.013× calcium (mg).

Net endogenous acid production= 54.5×(protein [g]/potassium [mEq])–10.2.

In contrast, those in the highest quintile of less healthy plant-based diet were more likely to be men and younger, less likely to be physically active, drank a higher amount of alcohol, and were less likely to have diabetes than those in the lowest quintile (all P<0.05). Those in the highest quintile of less healthy plant-based diet had higher intake of less healthy plant foods (7.2 servings) and carbohydrates, but lower intake of healthy plant foods (5.4 servings), fiber, and micronutrients (all P<0.05; Supplemental Table 3).

Incident CKD

During a median follow-up of 24 years, 4343 incident CKD events occurred. In model 2, those in the highest quintile of healthy plant-based diet had a 14% lower risk of CKD (hazard ratio [HR] comparing quintile 5 [Q5] versus quintile 1 [Q1], 0.86; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 0.78 to 0.96; P for trend =0.001) and those in the highest quintile of provegetarian diet had a 10% lower risk (HR, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.82 to 0.99; P for trend =0.03) compared with those in the lowest quintile (Table 3). These associations were similar in model 3.

Table 3.

Associations of plant-based diet scores with incident CKDa

| Diet Index | Quintiles of Plant-Based Diet Scores | P for Trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall plant-based diet index | Q1 (n=3386) | Q2 (n=2463) | Q3 (n=3680) | Q4 (n=2365) | Q5 (n=2792) | |

| IR per 100,000 PY | 4.0 (3.7 to 4.2) | 3.9 (3.7 to 4.2) | 3.9 (3.7 to 4.1) | 3.5 (3.3 to 3.8) | 3.6 (3.3 to 3.8) | |

| Model 1b | Ref. | 1.01 (0.92 to 1.12) | 0.98 (0.90 to 1.07) | 0.87 (0.80 to 0.96) | 0.90 (0.81 to 0.99) | 0.004 |

| Model 2c | Ref. | 1.03 (0.93 to 1.14) | 0.99 (0.91 to 1.08) | 0.91 (0.83 to 1.02) | 0.94 (0.84 to 1.03) | 0.06 |

| Model 3d | Ref. | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.15) | 0.97 (0.88 to 1.05) | 0.90 (0.82 to 1.00) | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.04) | 0.07 |

| Healthy plant-based diet index | Q1 (n=3067) | Q2 (n=3214) | Q3 (n=2554) | Q4 (n=3407) | Q5 (n=2444) | |

| IR per 100,000 PY | 4.1 (3.8 to 4.3) | 3.9 (3.7 to 4.2) | 3.7 (3.4 to 3.9) | 3.6 (3.5 to 3.9) | 3.5 (3.3 to 3.8) | |

| Model 1b | Ref. | 0.95 (0.87 to 1.03) | 0.88 (0.82 to 0.97) | 0.84 (0.77 to 0.91) | 0.81 (0.73 to 0.88) | 0.001 |

| Model 2c | Ref. | 0.97 (0.88 to 1.06) | 0.92 (0.85 to 1.01) | 0.88 (0.80 to 0.96) | 0.86 (0.78 to 0.96) | 0.001 |

| Model 3d | Ref. | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.07) | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.05) | 0.91 (0.83 to 0.99) | 0.91 (0.82 to 0.99) | 0.02 |

| Less healthy plant-based diet index | Q1 (n=2982) | Q2 (n=3254) | Q3 (n=2631) | Q4 (n=2891) | Q5 (n=2928) | |

| IR per 100,000 PY | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.0) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.1) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.0) | 3.9 (3.6 to 4.2) | |

| Model 1b | Ref. | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.15) | 1.06 (0.97 to 1.17) | 1.09 (0.99 to 1.20) | 1.14 (1.03 to 1.25) | 0.005 |

| Model 2c | Ref. | 1.05 (0.96 to 1.15) | 1.04 (0.96 to 1.16) | 1.07 (0.97 to 1.17) | 1.11 (1.01 to 1.21) | 0.04 |

| Model 3d | Ref. | 1.10 (1.01 to 1.20) | 1.12 (1.02 to 1.24) | 1.13 (1.03 to 1.25) | 1.18 (1.07 to 1.30) | 0.001 |

| Provegetarian diet index | Q1 (n=3607) | Q2 (n=3227) | Q3 (n=2306) | Q4 (n=2768) | Q5 (n=2778) | |

| IR per 100,000 PY | 3.9 (3.7 to 4.1) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.1) | 3.8 (3.6 to 4.1) | 3.7 (3.5 to 4.0) | 3.6 (3.4 to 3.8) | |

| Model 1b | Ref. | 0.96 (0.89 to 1.05) | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.03) | 0.90 (0.83 to 0.99) | 0.85 (0.78 to 0.94) | 0.002 |

| Model 2c | Ref. | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.06) | 0.96 (0.87 to 1.05) | 0.93 (0.85 to 1.01) | 0.90 (0.82 to 0.99) | 0.03 |

| Model 3d | Ref. | 0.97 (0.89 to 1.05) | 0.94 (0.85 to 1.04) | 0.91 (0.83 to 0.99) | 0.91 (0.82 to 0.99) | 0.02 |

Q, quintile; IR, incidence rate; PY, person-years; Ref., reference.

Cell contents are incidence rates or adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for incident CKD.

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race-center, and total energy intake.

Model 2 was adjusted for covariates in model 1 plus education, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and margarine consumption.

Model 3 was adjusted for covariates in model 2 plus baseline total cholesterol, lipid-lowering medication use, kidney function (two linear spline terms with one knot at 90 ml/min per 1.73 m2), hypertension, diabetes, and body mass index.

In contrast, those in the highest quintile of less healthy plant-based diet had an 11% higher risk of CKD (HR, 1.11; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.21; P for trend =0.04) in model 2. This association remained significant in model 3 (P for trend =0.001).

In model 3, the population attributable risk percentages of incident CKD for lower adherence to overall plant-based diet, healthy plant-based diet, and provegetarian diet was 4.1% (95% CI, 0.1% to 8.2%), 4.0% (95% CI, 0.6% to 8.3%), and 4.0% (95% CI, 0.2% to 7.7%), respectively. Incident CKD was not significantly attributable to higher adherence to less healthy plant-based diet (2.3%; 95% CI, −6.7% to 11.2%).

Associations were more often significant among men and black participants for all indices, but there was no significant interaction by sex or race/ethnicity (both P for interaction >0.05; Supplemental Figure 1). There was also no statistical evidence of interaction by diabetes status. Significant interaction by baseline weight status was observed for healthy and less healthy plant-based diet (both P for interaction =0.03). Among participants who were normal weight at baseline, those in the highest quintile of healthy plant-based diet had a 25% lower risk of CKD (P for trend =0.004), whereas those in the highest quintile of less healthy plant-based diet had a 52% higher risk (P for trend =0.001) compared with those in the lowest quintiles. No significant associations were observed for overweight and obese participants.

When components of plant-based diet indices were modeled simultaneously, those in the highest quintile of healthy plant food consumption had a lower risk of CKD (HR, 0.80; 95% CI, 0.72 to 0.89; P for trend <0.001), but no association was observed for less healthy plant food (P for trend =0.49) and animal food consumption (P for trend =0.80; Supplemental Table 4). Similar associations were observed with components of provegetarian diet.

Higher intake of legumes was associated with a lower risk of CKD, whereas higher intake of meats or sugar-sweetened beverages was associated with an elevated risk (all P<0.05; Supplemental Table 5). When we categorized string or green beans as vegetables, the results did not change (Supplemental Table 6). When margarine intake was considered as part of the scores, the associations with healthy plant-based diet (P for trend =0.06) and provegetarian diet (P for trend =0.06) were attenuated.

Annual eGFR Decline

In model 2, slower annual eGFR decline was observed for those in the highest quintiles of overall plant-based diet (Q5: −1.54 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per year; 95% CI, −1.59 to −1.49 versus Q1: −1.68; 95% CI, −1.72 to −1.63; P for trend <0.001) and healthy plant-based diet (Q5: −1.55; 95% CI, −1.60 to −1.49 versus Q1: −1.62; 95% CI, −1.66 to −1.57; P for trend =0.01) compared with those in the lowest quintiles (Table 4). Results did not change in model 3. No significant trend was observed for other indices (P for trend>0.1).

Table 4.

Annual change in eGFR according to quintiles of plant-based diet scores in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities studya

| Diet Index | Annual Change in eGFR (95% CI), ml/min per 1.73 m2 per yr | P for Trend | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall plant-based diet index | Q1 (n=3377) | Q2 (n=2430) | Q3 (n=3596) | Q4 (n=2348) | Q5 (n=2792) | |

| Model 1b | −1.68 (−1.73 to −1.64) | −1.58 (−1.63 to −1.53) | −1.58 (−1.62 to −1.54) | −1.55 (−1.60 to −1.49) | −1.55 (−1.59 to −1.50) | <0.001 |

| Model 2c | −1.68 (−1.72 to −1.63) | −1.58 (−1.62 to −1.53) | −1.57 (−1.62 to −1.52) | −1.55 (−1.60 to −1.50) | −1.54 (−1.59 to −1.49) | <0.001 |

| Model 3d | −1.64 (−1.67 to −1.60) | −1.55 (−1.59 to −1.51) | −1.54 (−1.58 to −1.50) | −1.53 (−1.57 to −1.48) | −1.52 (−1.56 to −1.50) | 0.002 |

| Healthy plant-based diet index | Q1 (n=2917) | Q2 (n=3142) | Q3 (n=3445) | Q4 (n=2684) | Q5 (n=2355) | |

| Model 1b | −1.62 (−1.66 to −1.57) | −1.61 (−1.66 to −1.57) | −1.57 (−1.62 to −1.53) | −1.57 (−1.62 to −1.52) | −1.55 (−1.61 to −1.50) | 0.04 |

| Model 2c | −1.62 (−1.66 to −1.57) | −1.62 (−1.66 to −1.57) | −1.58 (−1.62 to −1.53) | −1.57 (−1.62 to −1.52) | −1.55 (−1.60 to −1.49) | 0.01 |

| Model 3d | −1.58 (−1.62 to −1.54) | −1.58 (−1.62 to −1.54) | −1.55 (−1.57 to −1.50) | −1.54 (−1.60 to −1.51) | −1.52 (−1.57 to −1.48) | 0.04 |

| Less healthy plant-based diet index | Q1 (n=2954) | Q2 (n=3105) | Q3 (n=3378) | Q4 (n=2756) | Q5 (n=2350) | |

| Model 1b | −1.58 (−1.63 to −1.54) | −1.63 (−1.68 to −1.58) | −1.58 (−1.63 to −1.54) | −1.59 (−1.64 to −1.54) | −1.56 (−1.62 to −1.51) | 0.32 |

| Model 2c | −1.57 (−1.63 to −1.52) | −1.63 (−1.67 to −1.58) | −1.58 (−1.62 to −1.54) | −1.58 (−1.63 to −1.54) | −1.56 (−1.61 to −1.51) | 0.24 |

| Model 3d | −1.55 (−1.59 to −1.51) | −1.58 (−1.62 to −1.55) | −1.55 (−1.59 to −1.51) | −1.56 (−1.60 to −1.52) | −1.53 (−1.57 to −1.48) | 0.29 |

| Provegetarian diet index | Q1 (n=3590) | Q2 (n=3106) | Q3 (n=2235) | Q4 (n=2851) | Q5 (n=2761) | |

| Model 1b | −1.61 (−1.65 to −1.56) | −1.61 (−1.65 to −1.56) | −1.57 (−1.62 to −1.51) | −1.61 (−1.66 to −1.56) | −1.55 (−1.59 to −1.50) | 0.15 |

| Model 2c | −1.60 (−1.65 to −1.56) | −1.60 (−1.65 to −1.55) | −1.57 (−1.62 to −1.51) | −1.61 (−1.66 to −1.56) | −1.54 (−1.59 to −1.49) | 0.15 |

| Model 3d | −1.62 (−1.66 to −1.59) | −1.61 (−1.65 to −1.57) | −1.59 (−1.63 to −1.54) | −1.64 (−1.68 to −1.59) | −1.56 (−1.61 to −1.52) | 0.24 |

P for trend was obtained from an interaction term between follow-up time and quintiles of plant-based diet indices as an ordinal variable. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; Q, quintile.

Sample sizes for the analysis of annual change in kidney function differ from the main analyses of incident CKD because we used baseline dietary intakes only to construct the scores (and not the cumulative average of dietary intake assessed at baseline and visit 3).

Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, race-center, and total energy intake.

Model 2 was adjusted for covariates in model 1 plus education, smoking status, physical activity, alcohol consumption, and margarine consumption.

Model 3 was adjusted for covariates in model 2 plus baseline total cholesterol, lipid-lowering medication use, kidney function (two linear spline terms with one knot at 90 ml/min per 1.73 m2), hypertension, diabetes, and body mass index.

When components of plant-based diet indices were modeled simultaneously, those in the highest quintile of healthy plant food consumption had slower annual eGFR decline compared with those in the lowest quintile (Q5: −1.46; 95% CI, −1.50 to −1.43 versus Q1: −1.57; 95% CI, −1.60 to −1.43; P for trend =0.001). No significant association was observed for less healthy plant food (P for trend =0.08) or animal food (P for trend =0.09).

Discussion

In this community-based cohort of United States adults without CKD, higher adherence to a healthy plant-based diet or a provegetarian diet was associated with lower CKD risk, whereas adherence to a less healthy plant-based diet was associated with higher risk, independent of sociodemographic factors and health behaviors. Higher consumption of healthy plant foods (fruits, vegetables, whole grains, nuts, legumes, coffee, tea) was associated with a lower risk and slower eGFR decline.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report associations between plant-based diets and prospective risk of eGFR decline and CKD in the general population. Assuming a causal relationship, we found that a small but statistically significant percentage (4%) of CKD cases could have been avoided with higher adherence to plant-based diets. Our study extends findings from previous studies of dietary patterns and CKD risk, by adding that diets higher in healthful plant foods and lower in animal foods are associated with favorable kidney outcomes, and suggests the potential for using dietary modification for primary prevention of CKD (9–11).

The overall plant-based diet, healthy plant-based diet, and provegetarian diet showed similar results, but a stronger risk reduction was observed for the healthy plant-based diet (14%) compared with overall plant-based diet (6%) and provegetarian diet (10%). This may be because the healthy plant-based diet did not include potatoes and refined grains, two food groups that have been associated with a higher risk of hypertension and type 2 diabetes (25–27). In contrast, reverse scores were used for these foods for the healthy plant-based diet. We observed that the risk of CKD was 11% higher for those in the highest quintile of less healthy plant-based diet, suggesting that replacement of healthy plant foods with fruit juice, refined grains, and sweets may negate their protective benefit. In our comprehensive analysis of all four available and distinct indices of plant-based diets, we were able to provide a more nuanced characterization of plant-based diets in association with CKD risk, and highlight the importance of consuming healthy plant foods.

When stratified by baseline weight status, the associations between healthy and less healthy plant-based diet were significant only among normal weight participants. Those who are overweight or obese may already have precursors for CKD, such as an elevated risk of hypertension and type 2 diabetes, which may compromise the effectiveness of a dietary pattern (28). These results indicate that consuming a healthy plant-based dietary pattern in apparently healthy individuals with a normal weight can be important for CKD prevention.

In this study, higher overall plant-based diet and healthy plant-based diet scores were associated with slower eGFR decline, whereas no associations were observed for other indices. It is unclear why no association was observed for provegetarian diet because animal food intake and macronutrients do not appear to be qualitatively different for those in the highest quintiles of overall plant-based diet, healthy plant-based diet, or provegetarian diet. Previous studies have shown mixed results on plant-rich diets and decline in kidney function. An analysis of older white women reported that the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension diet was inversely associated with rapid eGFR decline (29). However, another study found that Mediterranean diet was not associated with changes in eGFR (9). Direct comparisons between these cohorts are difficult because the two studies had fewer number of visits and had older participants than the ARIC study. We also followed ARIC study participants for 15 years longer. Replication of our findings in different study populations is necessary to determine if diets higher in plant foods and lower in animal foods, such as a provegetarian diet, are associated with slower eGFR decline.

There are several mechanisms through which healthful plant-based diets may be associated with a lower risk of CKD and slower eGFR decline. Those in the highest quintile of healthy plant-based diet had lower dietary acid load and a higher intake of fiber and micronutrients. Higher dietary acid load has been associated with a higher risk of CKD, and modifying dietary acid load by increasing the intake of fruits and vegetables improved markers of kidney injury (17,30). Fiber intake has a direct inverse association with incident CKD, with a recent study reporting 11% lower risk with every 5-g higher fiber intake per day (31). Fiber has been shown to improve glycemic control and insulin secretion, which is associated with a lower risk of microalbuminuria and proteinuria (32). Fiber can also reduce the risk of CKD by attenuating risk factors of CKD, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes (33,34). Furthermore, higher intake of micronutrients can reduce inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction (35).

We found that those in the highest quintile of plant-based diet indices had the highest intake of sodium and phosphorus. However, these data should be interpreted with caution. Urinary sodium excretion is more strongly correlated with actual intake than estimates from dietary assessments, thus urinary sodium excretion is used as a proxy for dietary sodium intake (36,37). We could not examine urinary sodium excretion because the ARIC study did not have these data. For phosphorus, absorption may be low in plant-based diets as phosphorus in plant foods is less bioavailable because of phytate content (38,39).

Strengths of this study include a large sample size, racially diverse study population, long-term follow-up, and the use of a clinically relevant definition of CKD. Several limitations should be considered. First, participants used a food frequency questionnaire to report their dietary intakes, which is subject to measurement error. However, trained interviewers administered food frequency questionnaires using visual aids to reduce the error, and reliability has been quantified in the ARIC study (40). Second, we used sample-based scoring of plant-based diets to estimate adherence to different types of plant-based diets. Diets of those in the highest quintiles of all plant-based diet scores had higher plant food and lower animal food intake relative to other study participants. However, it is unclear whether certain thresholds exist for absolute levels of intake of plant and animal foods with respect to health outcomes. Third, some foods that could have been categorized into different food groups for scoring the plant-based diet indices were asked together on the food frequency questionnaire (e.g., cream of wheat was grouped with other whole grain foods), which may have led to misclassification. Fourth, the food frequency questionnaire had relatively limited assessment of whole grains. In future studies, detailed categorization of food items, and expansion of foods within each food group would be helpful. Fifth, the food frequency questionnaires were conducted several decades ago, and may not reflect the modern food supply or dietary intakes. For example, when margarine intake was included as a component of the scores, the associations were attenuated. These results support our approach and prior studies that excluded margarine from vegetable oil, because margarine may have been high in trans-fats during this time (7,18). However, margarines have been increasingly manufactured with higher unsaturated fatty acids over time (7). Future prospective studies with more recent dietary data are warranted. Sixth, although the ARIC study had two repeated dietary assessments, it may not represent long-term dietary habits. Our findings should be confirmed in cohorts with more dietary assessments. Lastly, a possibility of residual confounding exists.

In conclusion, higher adherence to plant-based diets and a vegetarian diet were associated with favorable kidney disease outcomes.

Disclosures

None.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.12391018/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix. Supplemental methods.

Supplemental Table 1. Selected baseline characteristics and nutritional characteristics by quintiles of overall plant-based diet index in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study.

Supplemental Table 2. Selected baseline characteristics and nutritional characteristics by quintiles of provegetarian diet index in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study.

Supplemental Table 3. Selected baseline characteristics and nutritional characteristics by quintiles of less healthy plant-based diet index in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study.

Supplemental Table 4. Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for incident CKD for highest versus lowest quintiles of healthy plant food, less healthy plant food, and animal food consumption.

Supplemental Table 5. Associations between individual components within plant-based diet scores and incident CKD.

Supplemental Table 6. Sensitivity analyses on the associations between quintiles of plant-based diet scores and incident CKD.

Supplemental Figure 1. Adjusted hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals for incidence CKD for highest versus lowest quintiles of plant-based diet scores according to sex, race/ethnicity, baseline weight status, and baseline diabetes status.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study participants and staff for their contributions. Dr. Kim wrote the manuscript and analyzed the data. Dr. Kim, Dr. Caulfield, and Dr. Rebholz designed the study and interpreted the data. Dr. Garcia-Larsen, Dr. Steffen, Dr. Grams, and Dr. Coresh contributed important intellectual content during drafting or revising the manuscript. Dr. Rebholz was involved in all aspects of the study from analyses to writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The ARIC study was supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health, and Department of Health and Human Services (grants HHSN268201700001I, HHSN268201700002I, HHSN268201700003I, HHSN268201700004I, and HHSN268201700005I). Dr. Rebholz was supported by a Mentored Research Scientist Development Award from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (K01 DK107782) and a grant from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (R21 HL143089).

The funding agencies had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, drafting of the manuscript, or the decision to submit this manuscript for publication. Some of the data reported here have been supplied by the US Renal Data System registry. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as official policy or interpretation of the US Government.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related Patient Voice, “A Nutritional Lie or Lifestyle?,” on pages 643–644.

References

- 1.Freeman AM, Morris PB, Barnard N, Esselstyn CB, Ros E, Agatston A, Devries S, O’Keefe J, Miller M, Ornish D, Williams K, Kris-Etherton P: Trending cardiovascular nutrition controversies. J Am Coll Cardiol 69: 1172–1187, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McMacken M, Shah S: A plant-based diet for the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Geriatr Cardiol 14: 342–354, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marsh K, Zeuschner C, Saunders A: Health implications of a vegetarian diet: A review. Am J Lifestyle Med 6: 250–267, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yokoyama Y, Nishimura K, Barnard ND, Takegami M, Watanabe M, Sekikawa A, Okamura T, Miyamoto Y: Vegetarian diets and blood pressure: A meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 174: 577–587, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dinu M, Abbate R, Gensini GF, Casini A, Sofi F: Vegetarian, vegan diets and multiple health outcomes: A systematic review with meta-analysis of observational studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 57: 3640–3649, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Orlich MJ, Singh PN, Sabaté J, Jaceldo-Siegl K, Fan J, Knutsen S, Beeson WL, Fraser GE: Vegetarian dietary patterns and mortality in Adventist Health Study 2. JAMA Intern Med 173: 1230–1238, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Satija A, Bhupathiraju SN, Rimm EB, Spiegelman D, Chiuve SE, Borgi L, Willett WC, Manson JE, Sun Q, Hu FB: Plant-based dietary patterns and incidence of type 2 diabetes in US men and women: Results from three prospective cohort studies. PLoS Med 13: e1002039, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Satija A, Bhupathiraju SN, Spiegelman D, Chiuve SE, Manson JE, Willett W, Rexrode KM, Rimm EB, Hu FB: Healthful and unhealthful plant-based diets and the risk of coronary heart disease in U.S Adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 70: 411–422, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khatri M, Moon YP, Scarmeas N, Gu Y, Gardener H, Cheung K, Wright CB, Sacco RL, Nickolas TL, Elkind MS: The association between a Mediterranean-style diet and kidney function in the Northern Manhattan Study cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 1868–1875, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rebholz CM, Crews DC, Grams ME, Steffen LM, Levey AS, Miller ER 3rd, Appel LJ, Coresh J: DASH (Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension) diet and risk of subsequent kidney disease. Am J Kidney Dis 68: 853–861, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang A, Van Horn L, Jacobs DR Jr., Liu K, Muntner P, Newsome B, Shoham DA, Durazo-Arvizu R, Bibbins-Domingo K, Reis J, Kramer H: Lifestyle-related factors, obesity, and incident microalbuminuria: The CARDIA (Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults) study. Am J Kidney Dis 62: 267–275, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haring B, Selvin E, Liang M, Coresh J, Grams ME, Petruski-Ivleva N, Steffen LM, Rebholz CM: Dietary protein sources and risk for incident chronic kidney disease: Results from the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. J Ren Nutr 27: 233–242, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobs DR Jr., Gross MD, Steffen L, Steffes MW, Yu X, Svetkey LP, Appel LJ, Vollmer WM, Bray GA, Moore T, Conlin PR, Sacks F: The effects of dietary patterns on urinary albumin excretion: Results of the Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) trial. Am J Kidney Dis 53: 638–646, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kontessis P, Jones S, Dodds R, Trevisan R, Nosadini R, Fioretto P, Borsato M, Sacerdoti D, Viberti G: Renal, metabolic and hormonal responses to ingestion of animal and vegetable proteins. Kidney Int 38: 136–144, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barsotti G, Morelli E, Cupisti A, Meola M, Dani L, Giovannetti S: A low-nitrogen low-phosphorus Vegan diet for patients with chronic renal failure. Nephron 74: 390–394, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garneata L, Stancu A, Dragomir D, Stefan G, Mircescu G: Ketoanalogue-supplemented vegetarian very low-protein diet and CKD progression. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 2164–2176, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goraya N, Simoni J, Jo C, Wesson DE: Dietary acid reduction with fruits and vegetables or bicarbonate attenuates kidney injury in patients with a moderately reduced glomerular filtration rate due to hypertensive nephropathy. Kidney Int 81: 86–93, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martínez-González MA, Sánchez-Tainta A, Corella D, Salas-Salvadó J, Ros E, Arós F, Gómez-Gracia E, Fiol M, Lamuela-Raventós RM, Schröder H, Lapetra J, Serra-Majem L, Pinto X, Ruiz-Gutierrez V, Estruch R; PREDIMED Group : A provegetarian food pattern and reduction in total mortality in the Prevención con Dieta Mediterránea (PREDIMED) study. Am J Clin Nutr 100[Suppl 1]: 320S–328S, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The ARIC Investigators : The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study: Design and objectives. The ARIC investigators. Am J Epidemiol 129: 687–702, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Willett WC, Sampson L, Stampfer MJ, Rosner B, Bain C, Witschi J, Hennekens CH, Speizer FE: Reproducibility and validity of a semiquantitative food frequency questionnaire. Am J Epidemiol 122: 51–65, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimakawa T, Sorlie P, Carpenter MA, Dennis B, Tell GS, Watson R, Williams OD; ARIC Study Investigators : Dietary intake patterns and sociodemographic factors in the atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Prev Med 23: 769–780, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim H, Caulfield LE, Rebholz CM: Healthy plant-based diets are associated with lower risk of all-cause mortality in US adults. J Nutr 148: 624–631, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Eggers P, Van Lente F, Greene T, Coresh J; CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) : A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med 150: 604–612, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spiegelman D, Hertzmark E, Wand HC: Point and interval estimates of partial population attributable risks in cohort studies: Examples and software. Cancer Causes Control 18: 571–579, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu EA, Pan A, Malik V, Sun Q: White rice consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: Meta-analysis and systematic review. BMJ 344: e1454, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muraki I, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Manson JE, Hu FB, Sun Q: Potato consumption and risk of type 2 diabetes: Results from three prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Care 39: 376–384, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borgi L, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Forman JP: Potato intake and incidence of hypertension: Results from three prospective US cohort studies. BMJ 353: i2351, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stenvinkel P, Zoccali C, Ikizler TA: Obesity in CKD--what should nephrologists know? J Am Soc Nephrol 24: 1727–1736, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin J, Fung TT, Hu FB, Curhan GC: Association of dietary patterns with albuminuria and kidney function decline in older white women: A subgroup analysis from the nurses’ health study. Am J Kidney Dis 57: 245–254, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rebholz CM, Coresh J, Grams ME, Steffen LM, Anderson CA, Appel LJ, Crews DC: Dietary acid load and incident chronic kidney disease: Results from the ARIC study. Am J Nephrol 42: 427–435, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mirmiran P, Yuzbashian E, Asghari G, Sarverzadeh S, Azizi F: Dietary fibre intake in relation to the risk of incident chronic kidney disease. Br J Nutr 119: 479–485, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fioretto P, Bruseghin M, Berto I, Gallina P, Manzato E, Mussap M: Renal protection in diabetes: Role of glycemic control. J Am Soc Nephrol 17[Suppl 2]: S86–S89, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Streppel MT, Arends LR, van ’t Veer P, Grobbee DE, Geleijnse JM: Dietary fiber and blood pressure: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Arch Intern Med 165: 150–156, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meyer KA, Kushi LH, Jacobs DR Jr., Slavin J, Sellers TA, Folsom AR: Carbohydrates, dietary fiber, and incident type 2 diabetes in older women. Am J Clin Nutr 71: 921–930, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Farhadnejad H, Asghari G, Mirmiran P, Yuzbashian E, Azizi F: Micronutrient intakes and incidence of chronic kidney disease in adults: Tehran lipid and glucose study. Nutrients 8: 217, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Espeland MA, Kumanyika S, Wilson AC, Reboussin DM, Easter L, Self M, Robertson J, Brown WM, McFarlane M; TONE Cooperative Research Group : Statistical issues in analyzing 24-hour dietary recall and 24-hour urine collection data for sodium and potassium intakes. Am J Epidemiol 153: 996–1006, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.He J, Mills KT, Appel LJ, Yang W, Chen J, Lee BT, Rosas SE, Porter A, Makos G, Weir MR, Hamm LL, Kusek JW; Chronic Renal Insufficiency Cohort Study Investigators : Urinary sodium and potassium excretion and CKD progression. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 1202–1212, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Clarys P, Deliens T, Huybrechts I, Deriemaeker P, Vanaelst B, De Keyzer W, Hebbelinck M, Mullie P: Comparison of nutritional quality of the vegan, vegetarian, semi-vegetarian, pesco-vegetarian and omnivorous diet. Nutrients 6: 1318–1332, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gluba-Brzózka A, Franczyk B, Rysz J: Vegetarian diet in chronic kidney disease-A friend or foe. Nutrients 9: 374, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Stevens J, Metcalf PA, Dennis BH, Tell GS, Shimakawa T, Folsom AR: Reliability of a food frequency questionnaire by ethnicity, gender, age and education. Nutr Res 16: 735–745, 1996 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.