Abstract

Cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids have been used as markers for diagnosis and targets for immunotherapy of malignant tumors. Recent progress in the analysis of their implications in the malignant properties of cancer cells revealed that cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids are not only tumor markers, but also functional molecules regulating various signals introduced by membrane microdomains, lipid rafts. In particular, a novel approach, enzyme‐mediated activation of radical sources combined with mass spectrometry, has enabled us to clarify the mechanisms by which cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids regulate cell signals based on the interaction with membrane molecules and formation of molecular complexes on the cell surface. Novel findings obtained from these approaches are now providing us with insights into the development of new anticancer therapies targeting membrane molecular complexes consisting of cancer‐associated glycolipids and their associated membrane molecules. Thus, a new era of cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids has now begun.

Keywords: cancer marker, cancer‐associated antigen, cluster, enzyme‐mediated activation of radical sources, ganglioside, glycosphingolipid, lipid raft

Abbreviations

- EMARS/MS

enzyme‐mediated activation of radical sources/mass spectrometry

- GD

disialyl ganglioside

- GEM

glycolipid‐enriched microdomain

- GM

monosialyl ganglioside

- GPI

glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- PDGFR

platelet‐derived growth factor receptor

- SCLC

small‐cell lung cancer

1. GLYCOSPHINGOLIPIDS AS FUNCTIONAL MOLECULES ON THE CELL SURFACE

Cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids have been considered as tumor markers,1 and used as diagnostic markers and targets of cancer treatment.2 There have been a number of reports on the specific expression of various glycosphingolipids in individual cancers. These include ganglioside GD3 in melanomas3 and T‐cell lymphoblastic leukemia,4, 5 GD2 in neuroblastomas,6 osteosarcomas,7, 8 small cell lung cancers9, 10 and breast cancers,11 and globotriaosylceramide in Burkitt's lymphomas.12 Sialyl Lewis A has also been used as a tumor marker of pancreatic, gastrointestinal,13 and other epithelial cancers;14 this structure is carried on both glycosphingolipids and mucins.2

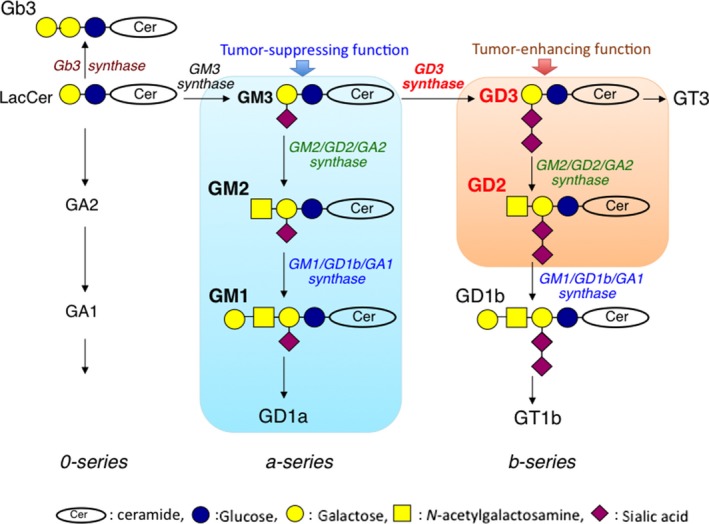

Remodeling of carbohydrate structures on proteins and lipids by artificial manipulation of glycosyltransferase genes has enabled us to further analyze the roles of these cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids in cancer cells in addition to mere cancer markers.15 Generally speaking, disialyl glycosphingolipids confer malignant properties in various cancer systems. In particular, tandem‐repeated sialic acid‐structures such as those in GD3 and GD2 enhanced the malignant properties of cancer cells, such as cell proliferation, cell invasion and migration, cell adhesion, and metastasis.15, 16, 17 In contrast, monosialyl gangliosides, such as GM1, GM3, and GM2 often suppress malignant properties of various cancer cells.18, 19, 20 Therefore, GD3 synthase is a key enzyme determining cell phenotypes based on the expression patterns of gangliosides, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Synthetic pathway of major acidic glycolipids and differential roles of gangliosides in cancers. Disialyl gangliosides (GD3, GD2) and monosialyl gangliosides (GM3, GM2, GM1) exert opposite effects to regulate cancer properties, ie, tumor‐enhancing function and tumor‐suppressing function, respectively. GD3 synthase (ST8SIA1) is a key enzyme determining the main direction of ganglioside synthesis. Cer, ceramide

2. ENIGMA IN THE ACTION MECHANISMS FOR GLYCOSPHINGOLIPIDS HAS BEEN GETTING DISCLOSED

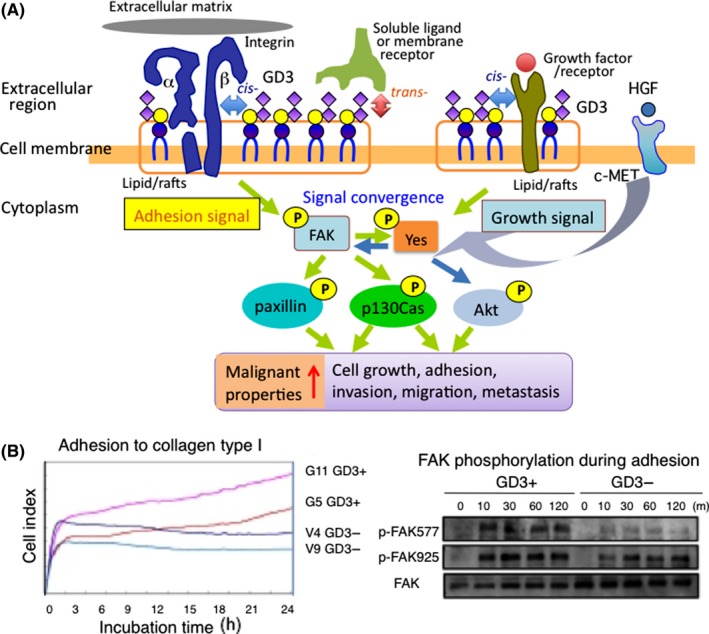

How these glycosphingolipids affect the phenotypes and behaviors of cells in various manners has also been rigorously analyzed, and molecular mechanisms by which glycosphingolipids modify cell signaling based on the interaction with other molecules existing on the same membrane (cis‐binding) or on the different cell surface (trans‐binding) have been reported.21 Although soluble and/or cell surface ligand molecules that gain access from outside cells are important as trans‐interacting molecules with glycosphingolipids,22 knowledge on cis‐interaction on the cell surface has recently advanced. In this group, growth factor receptors and adhesion receptors such as the integrin family are mainly defined as cis‐interacting molecules with glycosphingolipids on the cell surface, leading to the modification of cell signals mediated by those receptors16, 17(Figure 2). In Figure 2A, a representative example of signal convergence in melanomas is presented. Activation signals mediated by growth factor receptors are merged with adhesion signals by integrins, resulting in the convergence of signals, leading to the markedly enhanced promotion of downstream molecules such as AKT, p130Cas, and paxillin, and increased malignant properties of melanoma cells.16, 17

Figure 2.

Regulation of cell signals at lipid rafts by cancer‐associated glycolipids. A, Two main signaling pathways modulated by glycosphingolipids converge to enhance malignant properties of cancer cells. An example of ganglioside GD3 expressed in melanoma cells is shown. Cis‐acting vs trans‐acting molecules with glycosphingolipids on the cell membrane are also shown as well as 2 signaling pathways. B, An example of GD3‐mediated enhancement of adhesion signals in melanoma cells. Increased cell adhesion of GD3+ cells compared with GD3− cells as measured by real‐time cell electronic sensing (left). Increased phosphorylation levels of FAK during cell adhesion to collagen type I (right). Modified from Ohkawa et al17 with permission. HGF, hepatocyte growth factor

Results on increased adhesion signals by the integrin‐FAK axis are presented in Figure 2B.

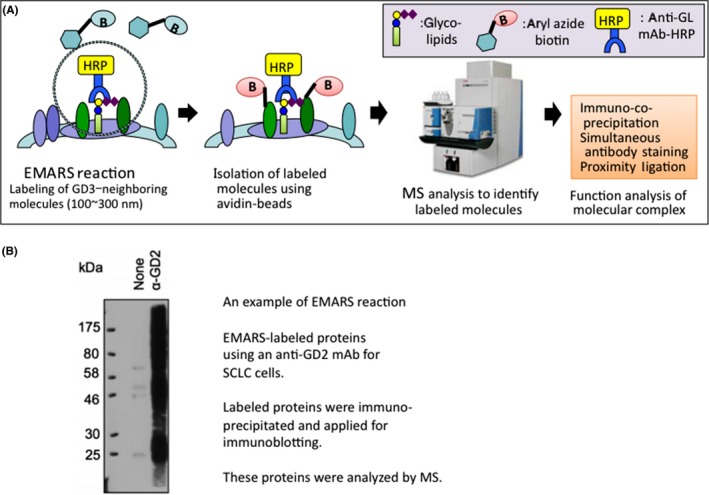

The recent development of a new approach to define interacting molecules with cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids on the surface of living cells has markedly promoted understanding of these interactions, namely EMARS/MS, developed by Honke and Kotani.23 To analyze molecular clustering on the cell surface, co‐immunoprecipitation has been used. Cross‐linking analysis, including photoaffinity labeling, with the aid of chemical cross‐linkers has also been used, leading to partly successful results with a restricted range of clustered molecules. Morphological visualization with fluorescence microscopy or electron microscopy has been used to obtain useful findings. However, all target molecules of these approaches need to be known at the starting points. Compared with these current methods, EMARS is a very powerful approach. The advantages of this approach can be summarized as follows: (a) using living cells to analyze events on the cell surface, corresponding to the size of microdomains; (b) no need for special equipment, and easy to carry out; and (c) applicable for comprehensive analysis of clustering molecules with particular targets, enabling the identification of molecular profiles including those of unknown molecules.24

Using “cancer‐specific” mAbs, we have identified candidate molecules that might physically and functionally interact with cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids on the cell surface within ca. 300 nm, as shown in Figure 3.23,24 Thus, how glycosphingolipids are expressed on the outer layer of the cell membrane and exert their roles in the regulation of cell phenotypes is now being clarified.

Figure 3.

Enzyme‐mediated activation of radical sources/mass spectrometry (EMARS/MS). A, Procedures of EMARS/MS analysis for identification of glycolipid‐associated molecules on the cell surface of living cells are shown (modified from Kotani et al23 with permission). Antibodies specific for particular glycolipids are labeled with HRP directly or indirectly (secondary Ab), and then biotin‐conjugated aryl azide is added, resulting in the biotin labeling of membrane molecules present around target glycolipids (within 200–300 nm). These molecules are applied to MS to identify the proteins and aid functional analysis, such as interaction and cooperation with glycolipid antigens. B, An representative EMARS reaction is shown, in which the reaction was carried out using anti‐ganglioside GD2 mAb for small‐cell lung cancer (SCLC) cells. Labeled proteins were immunoprecipitated and applied for immunoblotting. Only the sample labeled with the anti‐GD2 mAb showed multiple bands.35 These proteins were applied to MS

Consequently, EMARS/MS could be a very powerful approach to identify cooperating molecules with cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids. The features of molecular assembly depending on the changes in cell states can also be defined. Furthermore, we can investigate the roles of molecular complexes consisting of cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids and EMARS‐defined molecules. Downstream molecules activated by these molecular complexes have also been reported, as described in the following section.

3. CANCER‐ASSOCIATED GLYCOSPHINGOLIPIDS PLAY ROLES THROUGH COMPLEX FORMATION WITH MEMBRANE MOLECULES

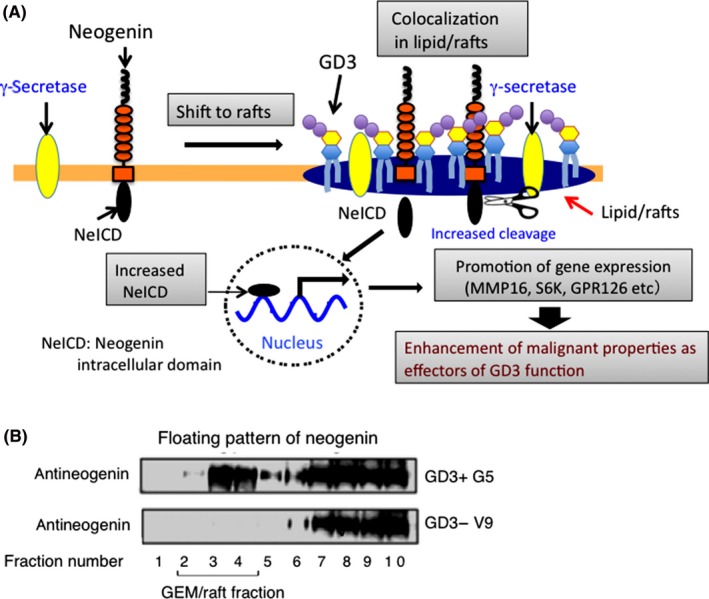

As described above, ganglioside GD3 has been considered as a melanoma‐specific glycolipid antigen,25 and been used as a target of Ab therapy and/or immune cell‐mediated therapy for malignant melanomas.26, 27 Roles of GD3 in melanomas have been reported based on experiments using cells transfected with GD3 synthase cDNA, showing its effects on the activation of signaling molecules located downstream of growth factor receptors28 or adhesion receptors, integrins.17 An EMARS/MS analysis (Figure 3) with melanoma cells using anti‐GD3 mAb revealed various membrane molecules as candidate molecules that associate with GD3.29 Among them, Neogenin‐1 was defined as a GD3‐associating molecule and also as a GEM/raft‐residing molecule exclusively in GD3+ cells.30 Neogenin‐1 was shown to be involved in enhancement of the malignant properties of melanomas such as increased cell growth, invasion, and migration, indicating that Neogenin‐1 might be an effector molecule exerting the effects of melanoma‐specific ganglioside, GD3 (Figure 4A). Consequently, GD3 expression resulted in the shift of Neogenin‐1 (Figure 4B) but also of γ‐secretase to lipid rafts from the nonraft compartment, leading to increased cleavage of the intracytoplasmic domain of Neogenin‐1. Neogenin intracytoplasmic domain promoted expression of multiple genes such as GPR126, STXBP5, MMP16, SPATA31A1, and S6K, as identified by ChIP‐sequencing, possibly playing central roles in enhancing the malignant properties of melanomas30 (Figure 4A).

Figure 4.

Neogenin was defined as a ganglioside GD3‐associating molecule in melanoma cells by enzyme‐mediated activation of radical sources/mass spectrometry. A, Under GD3 expression, Neogenin colocalized with GD3 and γ‐secretase in lipid rafts, resulting in increased generation of Neogenin intracytoplasmic domain (NeICD). Eventually, NeICD promotes the expression of various genes and enhances function of GD3 (modified from Kaneko et al30 with permission). B, Floating pattern (intracellular localization) of Neogenin was analyzed by sucrose density gradient ultracentrifugation of Triton X‐100 extracts from GD3+ (G5) and GD3− (V9) melanoma sublines. A shift of Neogenin to glycolipid‐enriched microdomain (GEM)/rafts was clearly indicated by immunoblotting (ref. 30)

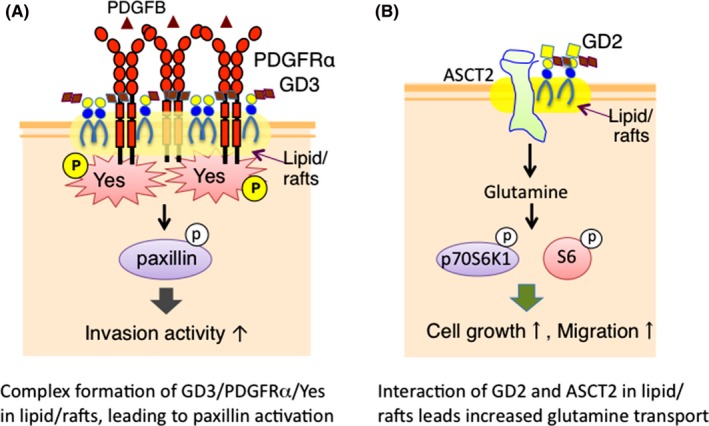

Using a replication‐competent avian leukemia virus splice acceptor system,31 we analyzed murine gliomas with a focus on the expression of gangliosides on the cell surface.32 Astrocytes transfected with PDGFB showed some levels of GD3 expression, and GD3+ and GD3– astrocytes were separated, enabling us to analyze the effects of GD3/GD2 expression on astrocytes. Thus, it was shown that GD3/GD2 expression increased cell growth, invasion, and migration. To clarify the mechanisms by which GD3/GD2 enhance the malignant properties of gliomas, EMARS/MS was carried out, and PDGFRα was defined as a GD3‐associating molecule in murine gliomas.32 Only GD3 formed a molecular complex with PDGFRα, and the Src family Yes was also included in the complex, leading to the formation of a ternary molecular complex adjacent to the cell membrane.32 This complex activated paxillin,32 resulting in the increased invasiveness that is the most notable feature of gliomas33 (Figure 5A).

Figure 5.

Action of ganglioside‐associating molecules defined by enzyme‐mediated activation of radical sources/mass spectrometry (EMARS/MS) analysis in murine gliomas and human small‐cell lung cancer (SCLC) cells. A, Platelet‐derived growth factor receptor‐α (PDGFRα) was defined as a GD3‐associating molecule in murine gliomas by the EMARS/MS approach. Specific association of GD3 with PDGFRα was identified by co‐immunoprecipitation, and activated Yes was also found in the immune complex. Subsequently, it was shown that membrane molecular complexes consisting of GD3, PDGFRα and Yes promote glioma invasiveness by activating paxillin.32 B, By EMARS/MS, a glutamine transporter, ASCT2, was defined as a GD2‐associating molecule in SCLC. ASCT2 cooperates with GD2, resulting in the increased activation levels of mTOR1 downstream molecules such as p70S6K1 and S6 in SCLC cells.35 These signals finally induce increased cell growth and migration

Application of the EMARS/MS approach resulted in the detection of GD3‐associating molecules in human melanoma and murine glioma cells, both of which are membrane receptors that regulate cell growth/differentiation. In contrast, a similar approach led to the detection of an amino acid transporter in SCLC.

Among human lung cancers, SCLC show high frequencies of metastasis and recurrence. Therefore, novel Ab therapy targeting SCLC‐specific antigens has been long expected.34 As a result of EMARS/MS using anti‐GD2 mAb and GD2 synthase‐transfectants of SK‐LC‐17,9 approximately 20 molecules were identified as candidates of GD2‐associating molecules.35 These molecules consisted of CD109, uPAR, EphA2, and CD44. Among them, ASCT2, a glutamine transporter, was most clearly localized in lipid rafts of GD2+ cells. Then we examined roles of ASCT2 in SCLC cells. The expression of ASCT2 in SCLC cells resulted in increased proliferation and invasion. ASCT2 colocalized with GD2 in GEM/rafts, and they were associated with each other, as shown by multiple approaches such as co‐immunoprecipitation and the proximity ligation assay.35 Consequently, ASCT2 co‐operated with GD2 and increased the uptake of glutamine, and increased activation levels of downstream molecules of mTOR1, such as p‐p70 S6K1 and p‐S635 (Figure 5B).

4. GLYCOSPHINGOLIPIDS REGULATE ARCHITECTURE AND FUNCTION OF GEM/RAFTS

The majority of the cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids mentioned above are considered to localize in GEM/rafts. Indeed, many of the EMARS/MS‐defined molecules targeting glycosphingolipids were detected in GEM/rafts.29, 36 Among GEM/raft‐residing molecules, such as cholesterol, sphingomyelin, GPI‐anchored proteins, and glycosphingolipids, the latter 2 are unique as they make up relatively uniform lipids and polymorphic nonlipid portions.36 The polymorphic portions, ie, proteins or carbohydrates, are exposed to the outside of the cell surface, interacting with outward ligands. Glycosphingolipids are particularly unique because they interact with outward ligands, but also with cis‐residing molecules on the same cell membrane, playing roles by forming molecular complexes consisting of assembled glycolipids and membrane molecules.

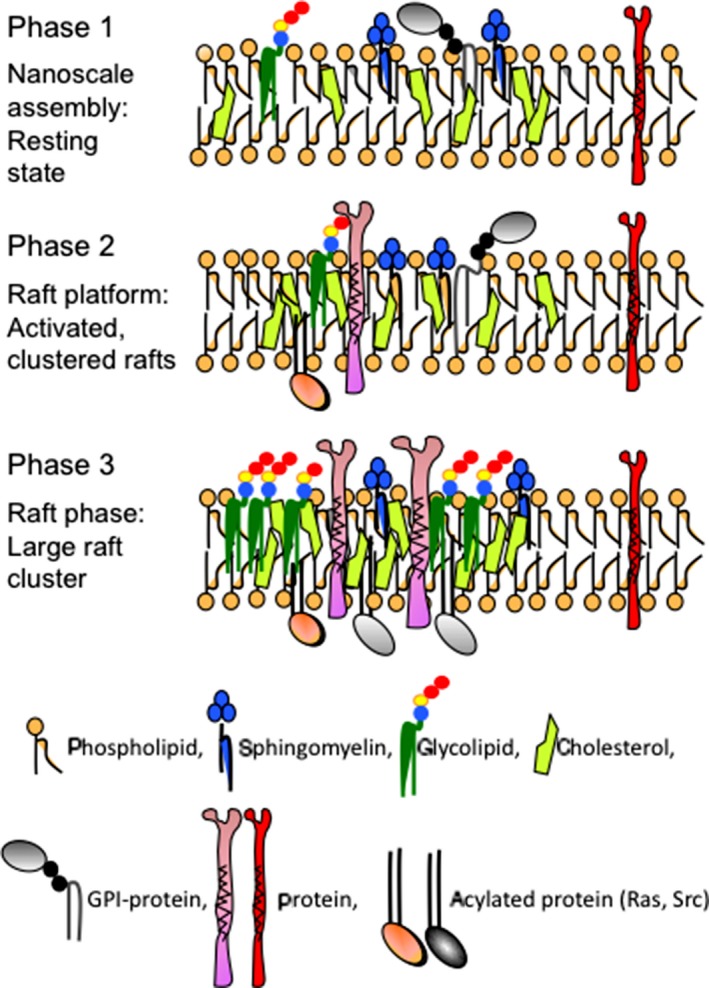

From our experience, alteration of the glycosphingolipid composition in cells and tissues resulted in marked changes in the architecture and function of GEM/rafts in cultured cells,17, 30 and also in experimental animals.37 Neo‐expression of GD3 induced marked changes in the intracellular localization of integrins, Src‐family kinases, and Neogenin in melanoma cells. A lack of gangliosides except GM3 resulted in the dispersion of GPI‐anchored proteins, such as complement regulatory proteins, as well as raft marker proteins from GEM/rafts in mouse brain tissues.37 Thus, expression patterns of glycosphingolipids determine the features of GEM/rafts, ie, profiles of GEM/rafts and properties of GEM/rafts as a platform for signal regulation. Lipid rafts have been considered to take part in the complex protein‐protein interactions for the generation of signal transduction.38 Lipid rafts can change size (from nanoscale to raft “phase”) and composition responding to intra‐ or extracellular stimuli, as shown in Figure 6.39 Therefore, how altered carbohydrates in cancer cells regulate the composition and function of GEM/rafts and cell signals, and whether individual cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids form distinct molecular clusters and exert unique signaling, remain to be clarified in the future.

Figure 6.

Three phases of lipid raft formation. Lipid rafts in phase 1 are in a resting state forming a nanoscale assembly consisting of cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)‐anchored proteins. The majority of glycosphingolipids are also present. Phase 2 rafts represent activated, clustered states forming a raft platform. Phase 3 means the raft phase with large cluster formation containing some trans‐membrane molecules. The size of phase 3 rafts is large enough for them to be detected by current methods, ie, microscale rafts (modified from Lingwood et al39 with permission)

5. DEVELOPMENT OF NOVEL TECHNOLOGY ENABLES US TO FURTHER UNDERSTAND GLYCOSPHINGOLIPIDS

In addition to the EMARS/MS approach, development of novel technologies has brought about a new era of cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids. Single molecule imaging with high resolution (millisecond scale) has made it possible to observe the spatiotemporal dynamics of molecular clustering on cell surfaces.40 It has become possible to observe processes of actual formation of molecular complexes on the cell surface.40 The results of these imaging experiments have been markedly changing the concept of GEM/rafts. Minimal units of nanoscale GEM/rafts might be dimer formation of glycosphingolipids with the same structure,41 whereas GPI‐anchored proteins should play central roles in the solid and microscale membrane domains.42 Analysis of interactions between cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids and interacting molecules with high‐resolution single molecule imaging would reveal new mechanisms for the generation of “cancer‐associated glyco‐signals”.43 One more novel technique that has supported single molecule imaging is that of chemical synthesis technology of fluorescence‐labeled glycosphingolipids.44 A new method to label glycosphingolipids developed by Komura et al is based on the incorporation of fluorescent dye in the carbohydrate portion of glycosphingolipids by maintaining their primary natures. This point is markedly different from the fluorescent ceramide analogue that was widely used in the trafficking, transfer, intracellular localization, and metabolism of glycosphingolipids.45 Modification of the ceramide moiety might generate confusing data, as lipid portions are essential for the intracellular trafficking and localization of glycosphingolipids. The new method has enabled us to obtain reasonable results concerning the dynamics of glycosphingolipids.

For a long time, glycosphingolipids have been considered to be regulatory molecules, particularly in the nervous system, mainly because of their abundant expression in neuronal cells.46 However, it was reported that fine structures of glycosphingolipids are not essential for the existence of bio‐organisms, but they are pivotal regulators of various cells and organs based on the regulation of cell signals in GEM/rafts.47 What should be emphasized here is that the cluster formation of glycosphingolipids with homopolymer mode could be critical for recognition by ligand molecules. Recently, heteropolymers have also been reported to sometimes be essential for interactions with cis‐ and trans‐acting ligands such as lectins.48, 49, 50 These molecular clusters in GEM/rafts should affect the assembly/dispersion of other membrane molecules in/from GEM/rafts,51 leading to the functional regulation of those membrane molecules.51, 52, 53 Furthermore, molecular complex formation in a vertical direction through the cell membrane is also crucial for the determination of cell fates.

Now, glycosphingolipids are emerging as regulators of membrane environments and cancer microenvironments, not just markers of cell differentiation and malignant transformation.

Based on novel findings on the functions and modes of action of cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids, novel therapeutic trials have been carried out, or considered.54 For example, when a novel signaling pathway activated by cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids is found, key molecules in the pathway could be targets of therapy. In fact, p130Cas and paxillin, which are activated in GD3+ melanomas, were examined as possible target molecules for siRNA therapy.55 Membrane proteins that are identified as partners of cancer‐associated glycolipids might be better targets for treatment. Downstream signal molecules of these partner membrane molecules could be more specific for cancer cells. Furthermore, identification of new epitopes formed by molecular complexes consisting of cancer‐associated glycolipids and their partners might be expected as new targets. If particular molecules in glycosylation machineries are considered to be cancer‐specific, and to play key roles, they could also be new targets of cancer therapy.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflict of interest for this article.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Drs. Honke and Kotani for valuable discussion and help with the EMARS approach. We also thank K Kaneko, N Esaki, T Mizuno, Y Nakayasu, S Yamamoto, and Y Kitaura for excellent technical assistance.

Furukawa K, Ohmi Y, Ohkawa Y, et al. New era of research on cancer‐associated glycosphingolipids. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:1544–1551. 10.1111/cas.14005

REFERENCES

- 1. Old LJ. Cancer immunology: the search for specificity–G. H. A. Clowes Memorial lecture. Cancer Res. 1981;41:361‐375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Lloyd KO. Humoral immune responses to tumor‐associated carbohydrate antigens. Semin Cancer Biol. 1991;2:421‐431. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pukel CS, Lloyd KO, Travassos LR, Dippold WG, Oettgen HF, Old LJ. GD3, a prominent ganglioside of human melanoma. Detection and characterisation by mouse monoclonal antibody. J Exp Med. 1982;155:1133‐1147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Merritt WD, Casper JT, Lauer SJ, Reaman GH. Expression of GD3 ganglioside in childhood T‐cell lymphoblastic malignancies. Cancer Res. 1987;47:1724‐1730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Okada M, Furukawa K, Yamashiro S, et al. High expression of ganglioside GD3 synthase gene in adult T cell leukemia cells unrelated to the gene expression of human T lymphotropic virus type I. Cancer Res. 1996;56:2844‐2848. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Saito M, Yu RK, Cheung NK. Ganglioside GD2 specificity of monoclonal antibodies to human neuroblastoma cell. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;127:1544‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Azuma K, Tanaka M, Uekita T, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation of paxillin affects the metastatic potential of human osteosarcoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:4754‐4764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shibuya H, Hamamura K, Hotta H, et al. Enhancement of malignant properties of human osteosarcoma cells with disialyl gangliosides GD2/GD3. Cancer Sci. 2012;103:1656‐1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yoshida S, Fukumoto S, Kawaguchi H, Sato S, Ueda D, Furukawa K. Ganglioside GD2 in small cell lung cancer cell lines: enhancement of cell proliferation and mediation of apoptosis. Cancer Res. 2001;61:4244‐4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cheresh DA, Rosenberg J, Mujoo K, Hirschowitz L, Reisfeld RA. Biosynthesis and expression of the disialoganglioside GD2, a relevant target antigen on small cell lung carcinoma for monoclonal antibody‐mediated cytolysis. Cancer Res. 1986;46:5112‐5118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cazet A, Bobowski M, Rombouts Y, et al. The ganglioside G(D2) induces the constitutive activation of c‐Met in MDA‐MB‐231 breast cancer cells expressing the G(D3) synthase. Glycobiology. 2012;22:806‐816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wiels J, Fellous M, Tursz T. Monoclonal antibody against a Burkitt lymphoma‐ associated antigen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1981;78:6485‐6488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jalanko H, Kuusela P, Roberts P, Sipponen P, Haglund CA, Mäkelä O. Comparison of a new tumour marker, CA 19‐9, with alpha‐fetoprotein and carcinoembryonic antigen in patients with upper gastrointestinal diseases. J Clin Pathol. 1984;37:218‐222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ichikawa D, Kitamura K, Tani N, et al. Molecular detection of disseminated cancer cells in the peripheral blood and expression of sialylated antigens in colon cancers. J Surg Oncol. 2000;75:98‐102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Furukawa K, Ohkawa Y, Yamauchi Y, Hamamura K, Ohmi Y. Fine tuning of cell signals by glycosylation. Biochem. 2012;151:573‐578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hamamura K, Furukawa K, Hayashi T, et al. Ganglioside GD3 promotes cell growth and invasion through p130Cas and paxillin in malignant melanoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:11041‐11046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ohkawa Y, Miyazaki S, Hamamura K, et al. Ganglioside GD3 enhances adhesion signals and augments malignant properties of melanoma cells by recruiting integrins to glycolipid‐enriched microdomains. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:27213‐27223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yoon SJ, Nakayama K, Hikita T, Handa K, Hakomori SI. Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase is modulated by GM3 interaction with N‐linked GlcNAc termini of the receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18987‐18991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Dong Y, Ikeda K, Hamamura K, et al. GM1/GD1b/GA1 synthase expression results in the reduced cancer phenotypes with modulation of composition and raft‐localization of gangliosides in a melanoma cell line. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2039‐2047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tsurifune T, Ito T, Li XJ, et al. Alteration of tumor phenotypes of B16 melanoma after genetic remodeling of the ganglioside profile. Int J Oncol. 2000;17:159‐165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Schnaar RL. Gangliosides of the Vertebrate Nervous System. J Mol Biol. 2016;428:3325‐3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nicoll G, Avril T, Lock K, Furukawa K, Bovin N, Crocker PR. Ganglioside GD3 expression on target cells can modulate NK cell cytotoxicity via siglec‐7‐dependent and –independent mechanisms. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:1642‐1648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kotani N, Gu J, Isaji T, Udaka K, Taniguchi N, Honke K. Biochemical visualization of cell surface molecular clustering in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:7405‐7409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Honke K, Kotani N. The enzyme‐mediated activation of radical source reaction: a new approach to identify partners of a given molecule in membrane microdomains. J Neurochem. 2011;116:690‐695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dippold WG, Lloyd KO, Li LT, Ikeda H, Oettgen HF, Old LJ. Cell surface antigens of human malignant melanoma: definition of six antigenic systems with mouse monoclonal antibodies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:6114‐6118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Houghton AN, Mintzer D, Cordon CC, et al. Mouse monoclonal IgG3 antibody detecting GD3 ganglioside: a phase I trial in patients with malignant melanoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:1242‐1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Scott AM, Lee FT, Hopkins W, et al. Specific targeting, biodistribution, and lack of immunogenicity of chimeric anti‐GD3monoclonal antibody KM871 in patients with metastatic melanoma: results of a phase I trial. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:3976‐3987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Furukawa K, Kambe M, Miyata M, Ohkawa Y, Tajima O, Furukawa K. Ganglioside GD3 induces convergence and synergism of adhesion and hepatocyte growth factor/Met‐signals in melanomas. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:52‐63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hashimoto N, Hamamura K, Kotani N, et al. Proteomic analysis of ganglioside‐associated membrane molecules: Substantial basis for molecular clustering. Proteomics. 2012;12:3154‐3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kaneko K, Ohkawa Y, Hashimoto N, et al. Neogenin defined as a GD3‐associated molecule by enzyme‐mediated activation of radical sources confers malignant properties via intra‐cytoplasmic domain in melanoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:16630‐16643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Huse JT, Holland EC. Genetically engineered mouse models of brain cancer and the promise of preclinical testing. Brain Pathol Zurich Switz. 2009;19:132‐143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ohkawa Y, Momota H, Kato A, et al. Ganglioside GD3 enhances invasiveness via Yes activation by forming a complex of GD3/PDGFRα/Yes in gliomas. J Biol Chem. 2015;290:16043‐16058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chen B, Xia L, Xu CS, Xiao F, Wang YF. Paxillin functions as an oncogene in human gliomas by promoting cell migration and invasion. Onco Targets Ther. 2016;9:6935‐6943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hamilton G, Rath B. Mesenchymal‐epithelial transition and circulating tumor Cells in small cell lung cancer. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;994:229‐245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Esaki N, Ohkawa Y, Hashimoto N, et al. ASCT2 defined by enzyme‐mediated activation of radical sources enhances malignancy of GD2‐plus small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:141‐153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Furukawa K, Ohmi Y, Kondo Y, et al. Lipid Rafts: The role of glycosphingolipids in lipid rafts: lessons from knockout mice In: Sillence D, ed. Properties, controversies and roles in signal transduction. London: Nova Science Publishers; 2014:1544‐20. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ohmi Y, Tajima O, Ohkawa Y, et al. Gangliosides play pivotal roles in the regulation of complement systems and in the maintenance of integrity in nerve tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:22405‐22410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Simons K, Toomre D. Lipid rafts and signal transduction. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2000;1:31‐39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lingwood D, Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane‐organizing principle. Science. 2010;327:46‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Komura N, Suzuki KG, Ando H, et al. New fluorescent ganglioside analogues reveal raft‐based ganglioside interactions with a GPI‐anchored receptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2016;12:402‐410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Suzuki KG, Kasai RS, Hirosawa KM, et al. Transient GPI‐anchored protein homodimers are units for raft organization and function. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:774‐783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Suzuki KG, Ando H, Komura N, Fujiwara TK, Kiso M, Kusumi A. Development of new ganglioside probes and unraveling of raft domain structure by single‐molecule imaging. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2017;1861:2494‐2506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Furukawa K, Ohkawa Y, Matsumoto Y, Ohmi Y, Hashimoto N, Furukawa K. Regulatory mechanisms for malignant properties of cancer cells with Disialyl and Monosialyl Gangliosides In: Furukawa K, Fukuda M, eds. Glyco‐signals in Cancer. Tokyo: Springer; 2016:57‐76. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Komura N, Suzuki KGN, Ando H, et al. Syntheses of fluorescent gangliosides for the studies of raft domains. Methods Enzymol. 2017;597:239‐263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cheng ZJ, Singh RD, Marks DL, Pagano RE. Membrane microdomains, caveolae, and caveolar endocytosis of sphingolipids. Mol Membr Biol. 2006;23:101‐110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wiegandt H. Gangliosides In: Wiegandt H, ed. Glycolipids, vol. 10 Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1985:199‐260. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Furukawa K, Ohmi Y, Ohkawa Y, Tajima O, Furukawa K. Glycosphingolipids in the regulation of the nervous system. Adv Neurobiol. 2014;9:307‐320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kusunoki S, Kaida K. Antibodies against ganglioside complexes in Guillain‐Barré syndrome and related disorders. J Neurochem. 2011;116:828‐832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mauri L, Casellato R, Ciampa MG, et al. Anti‐GM1/GD1a complex antibodies in GBS sera specifically recognize the hybrid dimer GM1‐GD1a. Glycobiology. 2012;22:352‐360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Greenshields KN, Halstead SK, Zitman FM, et al. The neuropathic potential of anti‐GM1 autoantibodies is regulated by the local glycolipid environment in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:595‐610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hakomori SI. The glycosynapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002. 99:225‐232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Simons K, Gerl MJ. Revitalizing membrane rafts: new tools and insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:688‐699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mollinedo F, Gajate C. Lipid rafts as major platforms for signaling regulation in cancer. Adv Biol Regul. 2015;57:130‐146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Furukawa K, Hamamura K, Aixinjueluo W, Furukawa K. Biosignals modulated by tumor‐associated carbohydrate antigens: novel targets for cancer therapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2006;1086:185‐198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Makino Y, Hamamura K, Takei Y, et al. A therapeutic trial of human melanomas with combined small interfering RNAs targeting adaptor molecules p130Cas and paxillin activated under expression of ganglioside GD3. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2016;1860:1753‐1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]