Abstract

Dittrichia viscosa which belongs to the Asteraceae family is frequently used to treat hematomas and skin disorders in Mediterranean herbal medicine. This study aims to validate its antioxidant effects and its potential on healing wounds. The ethanolic extract of D. viscosa leaves was formulated as 2.5% and 5% (w/w) in ointment bases on the beeswax and sesame oil. During this study, the ethanolic D. viscosa extract, ointments containing 2.5% and 5% of D. viscosa extract, and the vehiculum were assessed for their total phenol content (TPC), caffeoylquinic acid content (CQC), and antioxidant activities using complementary methods (TAC, the DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and the BCB). The effects on wound healing of obtained ointments were evaluated by excision of the wound in a mice model for 12 days. Subsequently, the excised wound areas were measured at the 3rd, 9th, and 12th days. The skin tissues were isolated for histological studies. The ointments containing D. viscosa extract (2.5%, 5%) possessed a considerable TPC, CQC, radical scavenging potential, and antioxidant activities compared to the vehiculum. Treated animals with ointments containing D. viscosa extract at 2.5% and 5% showed almost and totally healed wounds compared to the vehiculum and control groups, evidenced by good skin regeneration and reepithelialization. The present work showed the role of D. viscosa antioxidants exerted by its polyphenolic compounds, in particular, caffeoylquinic acids, in enhancing wound healing.

1. Introduction

The research to ensure a good quality of wound closure and scarless healing remains a health preoccupation until today [1, 2]. Recent investigation in wound healing mechanisms has evidenced that reactive oxygen species (i.e., hydroxyl OH−, peroxyl radicals ROO−, and superoxide anion O2−) act as mediator molecules between lymphoid cells and the wound sites as well as defensive molecules against pathogenic microorganisms in the wound area [3, 4]. In fact, basal level of reactive oxygen species (ROS) is necessary to regularize the inflammatory response, construction, and relaxation of blood vessels around wound areas [3, 4]. However, an excess of ROS level causes an imbalance between cellular production of free radicals (oxidants), and antioxidant defenses mechanisms, augmentation in inflammatory response, and inhibition of the wound repair [5, 6].

Indeed, antioxidants are scavengers molecules which are indispensable for neutralization of free radicals and for remediation of ROS damage during healing process [3, 6]. In this sense, plants extracts are emerging as a rich source of active compounds (i.e., triterpenes, flavonoids, polyphenolic, and tannins) for their pertinent properties to prevent from (i) accumulation of free radicals, (ii) oxidation of lipid, and (iii) inhibition of inflammatory disease. The use of several medicinal plants was strongly associated to their antioxidant properties. In particular, Asteraceae species plants were frequently used in wound healing treatment due to their high amount of phenolic compounds [7].

Among them, Dittrichia viscosa belonging to the genus of Dittrichia produced typical secondary metabolites such as phenolic compounds with antioxidant properties [7–10]. The D. viscosa was investigated against some free radicals (i.e., DPPH and ABTS). Then, some isolated flavonoids from this plant (i.e., sakuranetin, 7-O-methylaromadendrin, and 3-acetyl-7-O-methylaromadendrin) have been studied for their anti-inflammatory properties by subcutaneous injection of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) into mouse paws. However, to the best of our knowledge, the data about the antioxidant activities of crude extracts is scanty and there are no previous studies about the wound healing activity of D. viscosa ethanolic extract. The high use of this plant in traditional medicine in Mediterranean area explains our interest to suggest the usefulness of the extract of D. viscosa as wound healing ointment. The aims of the present study are to investigate in vitro the antiradical and antioxidant properties of ointments based on ethanolic D. viscosa extract and then to evaluate the potential of these ointments in wound healing in vivo.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Extraction and Identification of Major Constituents

Fresh leaves of D. viscosa were collected from a remote area in Sidi Thabet, province of Ariana, North West of Tunisia. The plant was botanically identified in the Laboratory of Botany and Ornamental Plants, National Institute of Agronomic Research of Tunis. Leaves were air dried and then ground (0.5 mm) using blender mill. The powdered leaf was macerated in ethanol (10:100, w/v (g/ml)) during 48 h. After filtration, the solvent of extract was removed in rotary evaporator (Schwabach, Germany). The dried ethanolic extract was used for all experiments. The constituents of Dittrichia viscosa extract were identified using HPLC-DAD-ESI/MS as previously reported [11], and 20 μL of extract at the concentration of 5 mg/mL was used for high performance liquid chromatography analysis (HPLC) using a chromatograph Alliance e2695 (waters, Bedford, MA, USA) equipped with photodiode array detector (PDA), interfaced with a triple quadruple mass spectrometer (MSD 3100, Waters) and an ESI ion source. The separation was carried out on an RP-xTerra MS column (150 × 4.6 mm. i.d., 3.5 μm particles sizes). The phase mobile composed of water (A) and acetonitrile (B), both containing formic acid 0.1% with flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The following gradient elution was used as follows: 0-40 min, 86 A%; 40-60 min, 85% A; 60-75 min, 100% A; 75-80 min, 86 % A. The mass spectra were acquired over m/z 100-1000 amu. The PDA acquisition wavelength was set in 200-800 nm, and the ionization conditions were performed as follows: electrospray voltage on negative mode of the ion source 25 V and a capillary temperature of 380°C. Mass Lynx v.4.1 software was used for data acquisition and processing. Identification of the constituents was based on their retention times, UV absorption spectra, and mass spectra data, as well as by comparison with authentic standards if available or literature data.

2.2. Ointment Preparation

2.2.1. Formulation of Topical Preparation

Two concentrations of D. viscosa ethanolic extract (2.5% and 5% (w:w)) were used to formulate ointments according to the method of Alkafafy et al. [12] with a slight modification. Black sesame oil was heated to 100°C and ethanolic extract was added and homogenized for 3 min using an Ultra-Turrax homogenizer (T25, IKA Works, Wilmington, NC). Then, the liquefied beewax (10% of ointment) was added into the mixture and dispersed for 2 min using Ultra-Turrax homogenizer. Finally, obtained ointments were transferred to cool in ambient temperature and stored for all subsequent studies.

In order to evaluate the total phenol content, the caffeoylquinic acid content, and the antiradical and antioxidant potential of samples, ethanolic extract of D. viscosa was solubilized in methanol at a concentration of 1 mg/mL, while ointments containing D. viscosa (2.5% and 5%) and ointment base (vehiculum) were solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) at concentration of 10 mg/mL.

2.2.2. Total Phenol Content (TPC)

The TPC was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu assay according to the method of Meda et al. [13]. Briefly, 500 μL of each dissolved sample (extract, or ointment) was added to 2.5 mL of 10-fold diluted Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. Then, the 2 mL of saturated sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) solution (7.5%) was added to the mixture. The reaction mixtures were kept in the dark for 2 h. After the incubation, the samples absorbance was measured at 760 nm against the blank (methanol for extract and DMSO for ointments). All assays were conducted in triplicate and the results were averaged. The gallic acid (GAE) was used as the standard and the results were expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalent per gram of sample (extract or ointment) (mg GAE/g sample).

2.2.3. Caffeoylquinic Acid Content (CQC)

The CQC in all samples was determined with the molybdate colorimetric assay according to the method of Chan et al. [14]. Briefly, 0.3 mL of appropriate sample solution was added to 2.7 mL of the molybdate reagent (1.65 g sodium molybdate, 0.8 g dipotassium hydrogen phosphate, and 0.79 g potassium dihydrogen phosphate in 100 mL of deionized water). The reaction mixture was incubated for 10 min, and its absorbance was measured at 370 nm against a blank sample. The chlorogenic acid (ChlA) was used as the standard and the results were expressed as milligram of ChlA equivalent per gram of sample (extract or ointment) (mg ChlA/g sample).

2.3. Antiradical and Antioxidant Properties

2.3.1. Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) Method

The total antioxidant capacities of extract and ointments were evaluated using the phosphomolybdenum method described by Prieto et al. [15] with slight modifications. An aliquot of 0.25 mL sample solution (with concentration that ranged from 0.01 to 1mg/mL for extract and from 1mg to 10 mg/mL for ointments and vehiculum) was mixed with 0.75 mL of reagent solution (2.4 M of sulfuric acid, 112 mM of sodium phosphate, and 16 mM of ammonium molybdate). Methanol was used as blank. The tubes were capped and incubated in a boiling water bath at 95°C for 90 min. After the samples had cooled in room temperature, the absorbance of each sample was measured in spectrophotometer (Milton Roy, New York, USA) at 695 nm. Total antioxidant capacity was expressed as equivalents of ascorbic acid per gram of sample (extract or ointment) (mg AAE/g of sample).

2.3.2. Diphenyl-1-Picrylhydrazyl (DPPH•) Method

The radical scavenging activity of the extracts against DPPH• free radical was determined by the method of Molyneux et al. [16] with some adjustments. 1 mL of sample solution (with concentration that ranged from 0.01 to 1mg/mL for extract and from 1mg to 10 mg/mL for ointments and vehiculum) was combined with methanol DPPH• solution (0.1 mM). The obtained samples were mixed vigorously and kept in the dark for 60 min.

Subsequently, the absorbance of each sample was measured at 517 nm. The scavenging activity was measured as the decrease in absorbance of the samples versus DPPH• standard solution. BHT synthetic antioxidant was used as positive control. Results were expressed as radical scavenging activity percentage (%) of the DPPH• according to the following equation:

| (1) |

where Abs0 represents absorbance value of the control and Abss represents absorbance value of sample.

The DPPH radical scavenging activity is shown as EC50 (μg sample/mL) which is the concentration necessary to 50% reduction of DPPH• radical.

2.3.3. 2-Azino-Bis-3-Ethylbenzothiazoline-6-Sulfonic Acid (ABTS) Method

The ABTS method is used according to Thaipong et al. [17] for investigating the radical scavenging capacity of each extract. The ABTS• solution was prepared by the dissolving of 7 mM ABTS• in deionized water with potassium persulfate (2.45 mM). The mixture was stranded in the dark at room temperature for 12-16 hours before use. The ABTS• solution was diluted in methanol to an absorbance of 0.7 at 734 nm. For each analysis, a 0.15 mL aliquot of sample solution (with concentration that ranged from 0.01 to 1 mg/mL for extract and from 1mg to 10 mg/mL for ointments and vehiculum) was added to 2.875 mL of ABTS• solution. The samples mixed were incubated for 15 min in the dark, and the absorbance was measured at 734 nm. BHT was used as standard.

Results were expressed in terms of EC50 (μg sample/mL), which is the concentration necessary to 50% reduction of ABTS• radical.

2.3.4. Ferric Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Method

The FRAP assay was performed as described by the method of Gouveia et al. [18]. The stock solutions included 300 mM of acetate buffer (3.1 g of C2H3NaO23H2O and 16 mL of C2H4O2, at pH 3.6, 10 mM of 2, 4, 6-tripyridyl-s-triazine (TPTZ) solution in 10 mM HCl, and 20 mM FeCl3 6H2O solution). The FRAP solution was prepared by mixing acetate buffer, TPTZ solution, and FeCl3 6H2O (10:1:1), and it was then warmed at 37°C before using. For each analysis, 0.15 mL of sample solution with concentration that ranged from 0.01 to 1mg/mL for extract and from 1mg to 10 mg/mL for ointments and vehiculum was added to 2,85 mL of the FRAP solution. The absorbance of the reaction mixture was measured at 593 nm after 30 min against methanol as blank. Results were expressed as micromole of Trolox equivalent per gram of sample (μmol TE/g of sample).

2.3.5. ß-Carotene Linoleic Acid (BCB) Method

The ß-carotene bleaching test was determined according to the method described by Velioglu et al. [19]. This assay based on the measure of the discoloration of ß-carotene during the oxidation of linoleic acid at 50°C of temperature. 0.2 mg of ß-carotene, 20 mg of linoleic acid, and 200 mg of tween 40 were dissolved in 0.5 mL of chloroform. After removing chloroform, 100 mL of oxygenated water was added to the final mixture and mixed until homogenization of the emulsion.

4 mL of the prepared mixture was added to 0.2 mL of sample solution (at concentration of 1mg/mL for extract and 10 mg/mL for ointments and vehicle) incubated for 2 h at 50°C in water bath. The BHT was used as a standard. The absorbance of all samples was measured at 470 nm at two times (t = 0 h and t = 2 h). The antioxidant power of sample was evaluated in terms of bleaching of ß-carotene using the following equation:

| (2) |

where Abs0 (t=0) represents absorbance value of control at zero time, Abs0 represents absorbance value of control after 2 h of incubation, Abst (t=0) represents absorbance value of sample at zero time, and Abst represents absorbance value of sample after 2 h of incubation.

2.4. Wound Healing Experimental Design

Forty Swiss Webster mice weighing about 20-25g were purchased from the Pasteur Institute of Tunis, Tunisia. Animals were fed with standard pellet diet and were maintained under the following conditions: temperature (25 ± 3°C), humidity (60 ± 5%), and 24-h light/dark cycle. All experiments were performed with respect to the Institutional Animal Ethical Committee. Hair was shaved on the dorsal back of mice and disinfected with ethanol (70 %). Skin wounds of 10 mm diameter circular full-thickness were made on back of mice using a skin biopsy punch. Animals were randomly allocated into four groups (n=10 each): Group 1: negative control; the group had not received any healing creams/ointments. Group 2: the wounded area was treated with the ointment base (vehiculum). Group 3: the wounded area was treated with ointment of D. viscosa extract 2.5%. Group 4: the wounded area was treated with ointment of D. viscosa extract 5%. Ointments and vehiculum were applied daily during 12 post-wounding days [12]. At 3, 9, and 12 days of wound healing period, the wound area was measured and the percentage wound contraction was calculated according to the following equation:

| (3) |

2.5. Histological Studies

On the 3rd, 9th, and 12th days, three mice were randomly taken from each group for the histological examination. The isolated wound tissues from mice skin were formalin fixed and paraffin blocked. Then, 5 μm thick transverse incisions were made by means of a microtome fixed blade. Finally, sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) and examined by light microscope (Olympus BX51) and photomicrographed using light microscope (Olympus BX51).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Results were statistically analysed by using one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test. Significant differences were set at p<0.05. The IBM SPSS 22 was used to perform statistical analysis.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. HPLC-DAD-MS Analysis of D. viscosa Ethanolic Extract

Based on mass spectrum, UV spectra, and retention time of each peak of HPLC-PDA-ESI-MS/MS data, 29 phenolics were identified in ethanol extract of D. viscosa (Table 1).

Table 1.

Retention time, UV and mass spectral data, and tentative identification of the phenolic components in ethanolic leaves extractof D. viscosa.

| Peak n | Tr (min) | λ max max | [M-H]− (m/z) | Fragments ions (m/z) | Tentative of identification | Ref/std |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7.969 | 325 | 353 | 191 (100)-161(10) | Chlorogenic acid | std |

| 2 | 8.231 | 260-324 | 375 | 375(20)-191(100) | 3-o-Caffeoylquinic acid | std |

| 3 | 9.153 | 293-324- | 543 | 387(50)-191(100) | 1,3-O-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | std |

| 4 | 11.405 | 260 | 599 | 467(100) | Ganoderic acid C6 | [20] |

| 5 | 11.694 | 260 | 599 | 467(100) | Ganoderic acid C6 | [20] |

| 6 | 12.243 | 280 | 583 | 467(100)-329(50) | Ganoderic acid D | [20] |

| 7 | 18.712 | 284sh | 609 | 429(60)-341(20)-301(100)-151(60) | Quercetin-galactosylrhamnoside | [21] |

| 8 | 19.609 | 260-284sh | 741 | 509(50)- 301(100)- 241(60) | Rutin-O-pentoside | [22] |

| 9 | 20.751 | 260-331 | 463 | 301(100)-179(20)-151(30) | Quercetin-3-O-glucoside | [23] |

| 10 | 21.158 | 260-332 | 591 | 301(100)-179(20)-151(30) | Rutin | std |

| 11 | 22.791 | 326 sh | 741 | 301(100)-241(20)-151(30) | Quercetin-7-O-xyloside-3-O-rutinoside | [23] |

| 12 | 23.350 | 327 | 515 | 315(70)-191(40)-179(100) | 3,4-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | std |

| 13 | 25.543 | 327 | 515 | 353 (33)-191 (100)- 179(30) | 3,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | std |

| 14 | 26.253 | 327 | 677 | 515(15)-353(15)-191(100)-179(40)-135(20) | Dicaffeoylquinic acid glucoside | [24] |

| 15 | 27.015 | 326 | 653 | 515(15)-353(15)-191(100)-179(40)-135(20 | 3, 4,5-Tricaffeoylquinic acid | std |

| 16 | 28.901 | 327 | 515 | 353(30)-191(50)-179(100)-135(40) | 1,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | std |

| 17 | 29.180 | 327 | 515 | 353(30)-191(50)-179(100)-135(40) | 3,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | std |

| 18 | 30.525 | 324 | 591 | 509(30)-191(70)-179(100) | 4,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid | std |

| 19 | 32.022 | 326 | 790 | 591- 405(80)-241(100)-191(60) | Dehydrodimers of caffeic acid | [25] |

| 20 | 33.291 | 260-327 | 489 | 241(100) | Isoorientin | [26] |

| 21 | 35.414 | 281-327 | 489 | 241(100) | Isoorientin | [26] |

| 22 | 36.108 | 292-323 | 303 | 241(60), 151(100) | Dihydroquercetin | [21] |

| 23 | 39.280 | 280-328 | 567 | 413(100) | Apigenin-glucoside | [26] |

| 24 | 41.792 | 288 | 493 | 493(100) | Myricetin-O-glucuronide | [27] |

| 25 | 44.651 | 332-288 | 495 | 493(100) | Dihydromyricetin-O-glucuronide | [28] |

| 26 | 46.004 | 260-297-330 | 493 | 493(75)-315(100)-300 (50)-271 (80) | Isorhamnetin-O-glucuronopyranoside | [29] |

| 27 | 47.815 | 260-290-331 | 533 | 515(100), 353 (80) | Dicaffeoylquinic derivatives | std |

| 28 | 51.130 | 260-327 | 757 | 553(25), 323 (20), 203(100), 165 (50), 133 (30) | Caffeoyl-N-tryptophan | [26] |

| 29 | 52.061 | 260-330 | 553 | 265(70), 203(100), 163(40) | Caffeoyl-N-tryptophan-rhamnoside | [26] |

The dicaffeoylquinic isomers (i.e., chlorogenic acid, 1, 3-O-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 3, 4 dicaffeoylquinic acid, 3, 5-dicaffeoylquinic acid, 1, 5-Di-caffeoylquinic acid, and 4, 5-dicaffeoylquinic acid) and quercetin derivatives (i.e., quercetin-galactosylrhamnoside, rutin-O-pentoside, quercetin-3-O-glucoside, rutin, and dihydroquercetin) were the major phenolic compounds. Others minor compounds (i.e., isoorientin, apigenin-glucoside, myricetin, and isorhamnetin-O-glucuronopyranoside) were also found.

To the best of our knowledge the triterpenoid ganoderic acids were identified for the first time in D. viscosa ethanolic extract. In this context, the comparison of our finding with previous results evidenced that the main representative compounds were unchangeable contrary to other minor compounds which are dependent on environmental factors (i.e., territory, temperature, and period of plant collection) and methods of extraction (materials, solvent, and extraction time) [11, 30].

3.2. Contents of Total Phenolics and Caffeoylquinic Acid

The TPC and CQC of D. viscosa ethanolic extract leaves, ointment base, and ointments containing 5% and 2.5% of extract have been reported in Table 2.

Table 2.

Total phenol content (TPC), caffeoylquinic acid content (CQC) of D. viscosa ethanolic extract, ointment base, and ointment containing 5% and 2.5% of extract.

| Ethanolic extract [11] | Ointment containing 2.5% of extract | Ointment containing 5% of extract | Ointment base (vehiculum) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPC (mg GAE/g of sample) | 117.58 ± 1.29 | 4.70 ± 0.19 | 11.27 ± 0.121 | 0.94 ± 0.05 |

| CQC (mg ChlA/g of sample) | 71.85 ± 0.35 | 1.85 ± 0.06 | 4.77 ± 0.02 | 0.00±0.00 |

The TPC and CQC of D. viscosa ethanolic extract leaves were comparable to leaves of Asteraceae family plant (i.e., Cynara scolymus L. and Cynara cardunculus) [31–33]. The TPC and CQC values of ointment containing 2.5% and 5% of D. viscosa ethanolic extract showed that there is no considerable loss in amount of both phenolic and caffeoylquinic acid compounds during the formulation of ointments. In this sense, it has been reported that the CQC are slightly modifiable after heating at temperature of 100°C for 5 min [34].

3.3. Antiradical and Antioxidant Properties

The TAC, The DPPH, ABTS, FRAP, and the BCB of D. viscosa ethanolic extract, ointment base, and ointment containing 5% and 2.5% of extract have been represented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Total antioxidant capacity, free radical scavenging (DPPH; ABTS), ferric reducing power, linoleic acid inhibition of D. viscosa ethanolic extract, ointment base, and ointment containing 5% and 2.5% of extract.

| TAC (mg AAE/g of sample) | EC 50 DPPH (μg/ml) | EC 50 ABTS (μg/ml) | FRAP (mg TE/g of sample) | ß-carotene linoleic acid | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanolic extract | 133.02 ± 3.1 | 56.25 ± 1.2 | 147.26 ± 1.5 | 296.425 ± 3.3 | 54.01± 1.4 |

| (%I for 1 mg/mL) | |||||

| Ointment base (Vehiculum) | 1.61± 0.1 | 7977.00 ± 225.0 | 12550 ± 132 | 4.37 ±0.3 | 10.85 ± 1.1 (%I for 10 mg/mL) |

| Ointment containing 2.5% of extract | 3.41 ±0.2 | 3073.70±138.8 | 6290± 183.9 | 11.69 ± 0.2 | 36.22 ± 0.9 |

| (%I for 10 mg/mL) | |||||

| Ointment containing 5% of extract | 7.46 ± 0.7 | 1360.50±90.6 | 3473.7± 217.5 | 19.85 ± 0.4 | 48.05± 1.8 |

| (%I for 10 mg/mL) | |||||

| BHT | - | 26.92 ± 1.22 | 42.64 ± 0.12 | - | 62.18 ± 1.6 |

| (% I for 1 mg/mL) |

Values expressed are means ± S.D.

The results of antiradical and antioxidants screening of D. viscosa leaves showed that our findings were comparable to other plants of Asteraceae family. In fact, the TAC, EC50 (DPPH), EC50 (ABTS), FRAP, and BCB values were in the range of other Asteraceae plants from different country where the TAC ranged from 110.03 to 194.64 mg AAE/g extract [35, 36], and EC50 (DPPH) values ranged from 100 to 250 μg/mL [37]. EC50 (ABTS) ranged from 180 to 200 μg/mL. FRAP values were ranging from 12.083 to 626.783 mg TE/g extract [38] and BCB percentage ranged from 34.8 to 75.20% [36, 39].

To the best of our knowledge there is no data on FRAP and BCB method of D. viscosa extracts. However, the TAC, EC50 (DPPH), and EC50 (ABTS) are in good agreement with those of Morocco D. viscosa leaves extracts [40]. Based on those findings the ethanolic D. viscosa exhibited a strong antioxidant activity explained by the high phenolic content, particularly by the highest caffeoylquinic acid content as indicated in Table 2. Previous investigation on plant of Asteraceae family was in relation to the role of polyphenols such as hydroxycinnamic acids (ferulic acid, p-coumaric acid, chlorogenic acid, and caffeic acid) on the antioxidant activity [41, 42]. Other studies confirmed the implication of dicaffeoylquinic derivatives in antioxidant activity and other biological activities [41, 43, 44].

In particular, the high contribution of caffeoyl derivatives in the antioxidant activities of D. viscosa was confirmed by Danino et al. [45] who proved that the isolated compound 1, 3-diCQA from D. viscosa has the greatest scavenging activity DPPH (EC50=40μM) and ABTS (EC50 =12±0.4 μM) than the trolox standard.

As shown in Table 3, 10 mg of ointments based on D. viscosa extract (2.5 and 5%) that exhibited excellent antiradical and antioxidant capacity values was comparable to 1 mg of BHT. The antioxidants, ointment samples showed dependence on to the concentration used. The ointment of D. viscosa extract (5%) possessed the high and the total antioxidant capacity comparing to ointment of D. viscosa extract (2.5%) and the base ointment, evidenced by its strongest radical scavenging activities, ferric reducing as well as BCB inhibition. These findings suggested that the formulation at temperature of 100°C did not affect significantly the phenolic composition and did not significantly change the antioxidant activities. Our findings were in agreement with previous studies that proved that phenolic acids (i.e., gallic, gentisic, protocatechuic, and caffeic acids) in pork lard showed a significant antioxidant activity at 150°C [46]. In another study, the addition of antioxidant (i.e., caffeic acid and tyrosol) into refined camellia oil before heating at temperature up to 120°C has been protecting the oil from oxidation and molecular changing [47].

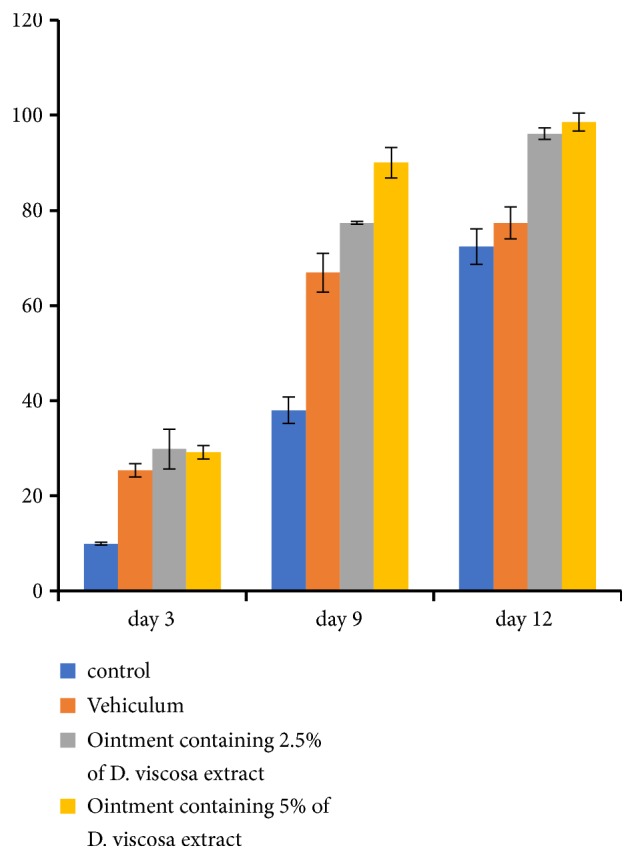

3.4. Wound Contraction Ratio

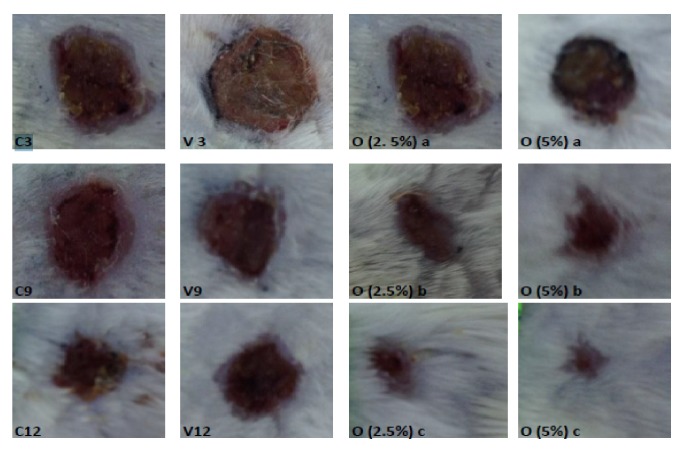

Comparing the three animal groups treated with ointments to the negative control, the wound area decreased significantly (p<0.05) by the twelfth day. The wound contraction ratio depends on the concentration of extract present in the ointment. In particular, on the 3, 9, and 12 days, the ointment containing D. viscosa 5% presented the highest wound contraction ratio to animals (Figures 1 and 2).

Figure 1.

Percentage of wound contraction rate of mice treated with D. viscosa (2.5%, 5%) ointments, positive control (vehicle) and negative control on in vivo wound model.

Figure 2.

Morphological representation on wound contraction of different groups after 3, 9, and 12 days of topical application: ∗C3: control day 3; ∗C9: control day 9; ∗C12: control day 12; ∗V3: control day 3; ∗V9: control day 9; ∗V12: control day 12; O (2.5%) a: ointment containing D. viscosa (2.5%) day 3; O (2.5%) b: ointment containing D. viscosa (2.5%) day 9; O (2.5%) a: ointment containing D. viscosa (2.5%) day 12; O (2.5%) a: ointment containing D. viscosa (5%) day 3; O (2.5%) b: ointment containing D. viscosa (5%) day 9; O (2.5%) a: ointment containing D. viscosa (5%) day 12.

After 12 days, mice treated with ointments containing D. viscosa at 2.5% and 5% were totally healed while the vehicle showed a 57 % healing rate (Figure 2). A correlation between the antioxidant activities and wound contraction ratio of animals was observed. Thus, we suggest that antioxidant properties of D. viscosa enhanced the wound healing.

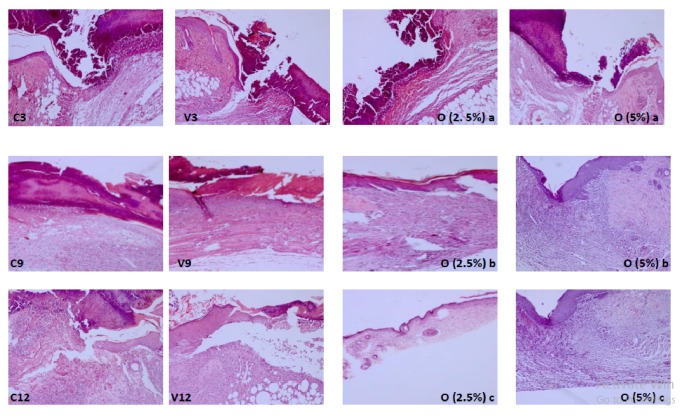

3.5. Histological Study

Over 3 days, the tissue sections of all mice groups showed incomplete healing in wound site without significant difference between the groups; this was manifested by the large area of scab tissue. The inflammatory cells and fibrin were accumulated in granulation tissue and fibroblasts were dispersed (Figure 3: C3, V3, O (2.5%) a, and O (5%) a).

Figure 3.

Histological sections of mice of different groups after 3, 9, and 12 days of topical application C3, V3, O (2.5%) a, and O (5%) a: complete destruction acute of epiderm, presence of inflammatory cells, and fibrin. C9, C12, V9, and V12: acute inflammation and destruction of epiderm. O (2.5%) b: proliferation of collagens fibers, inflammatory discreet infiltrate, and reepithelization. O (5%) b: proliferation of collagens fibers and inflammatory discreet infiltrate more important than those observed in O (2.5%) b. O (2.5%) c: Complete reepithelization. O (5%) c: reepithelization and crosslinking of collagen fibers.

After 9 days, the tissue sections showed obvious difference between groups, though the number of inflammation cells decreased in all groups. Scab area tissue was observed only in the control group and vehicle group. On the other hand, there was great epithelial and collagen fibers organization, remarkable reduction in inflammation cell, and high distribution of fibroplasias. Groups treated with ointments containing D. viscosa (5%, 2.5%) showed greater healing quality compared with other groups manifested by tissue remodeling, the deposition of collagen in the wound and vessels regression, and mostly restored and keratinized epidermis after 9 days (Figure 3: O (5%) b and O (2.5%) b). With 5 % of D. viscosa extract, proliferation of collagens fibers was observed and inflammatory infiltrate was more important than those observed in group treated with 2.5% of D. viscosa extract (Figure 3: O (5%) b).

On day 12, the tissue section showed difference between untreated group (negative control, vehicle) and treated ones with ointments containing D. viscosa. Untreated group showed incomplete healing skin (Figure 3: C9, C12, V9, and V12), while group treated with ointment containing 2.5% revealed quasi-complete healing with maturated granulation tissue and hair follicles as well as highly organized collagen and high distribution of fibroblast cells (Figure 3: O (2.5%) c). Concerning the group treated with ointment containing 5% it showed complete healing and full reepithelialization where the numbers of cells and blood vessels were decreased significantly and the collagen fibers had been cross linked (Figure 3: O (5%) c).

In general, our findings are in agreement with previous observations that natural antioxidants promote the wound healing [12, 48, 49]. The wound healing is a dynamic interaction between epidermal and dermal cells and extracellular cells, which occurs in three successive phases: inflammation, proliferation, and maturation. In fact, during the inflammatory process the antioxidant altered the migration of the neutrophil to wound area and modulated neutrophil and macrophages influx (i.e., hydrolytic enzymes, reactive oxygen species, and reactive nitrogen species) [50], thus scavenging free radicals and preventing them from damage during proliferation and maturation process. The antioxidants stimulate synthesis of collagen, enhance cell proliferation and the angiogenesis, and promote the reepithelization of the wound [51]. In this context, some individual phenolic compounds (i.e., protocatechuic acid and caffeic acid) have a potential role in cytokines release in wound site, i.e., vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-b) which are involved in remodeling the damaged tissue and accelerate the reepithelization [51, 52].

4. Conclusions

Our findings suggest that Tunisian D. viscosa could be a consistent source of antioxidant compounds particularly the caffeoylquinic, being able to scavenge free radicals and to prevent from oxidative damage. Subsequently, the investigation on properties of ointment containing D. viscosa leaves showed the potential antioxidant and wound healing effect. Thus, we suggest the role of phenolic compounds in antioxidant and healing wound activities. Hence, this study scientifically opens the perspective to the usefulness of D. viscosa as new pharmaceuticals product for oxidative stress and wound healing. However, further in vivo tests should be carried out.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Tunisian Ministry of High Education and Scientific Research.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Supplementary Materials

Graphic summary description: the ethanolic extract of D. viscosa leaves was leaves chemically characterized with HPLC-DAD-MS and it was used to formulate ointments (5% and 2.5% (w/w)) for healing wound test. Then, the antioxidants and the healing activities of those ointments were evaluated. The results obtained from this study revealed the excellent antioxidant potential of ointments base on ethanolic extract of D. viscosa and evidence their role in improving the rate and the quality of wound contraction samples.

References

- 1.Takeo M., Lee W., Ito M. Wound healing and skin regeneration. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2015;5(1) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a023267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yates C. C., Hebda P., Wells A. Skin wound healing and scarring: fetal wounds and regenerative restitution. Birth Defects Research Part C - Embryo Today: Reviews. 2012;96(4):325–333. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunnill C., Patton T., Brennan J., et al. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) and wound healing: the functional role of ROS and emerging ROS-modulating technologies for augmentation of the healing process. International Wound Journal. 2015;12(6):1–8. doi: 10.1111/iwj.12557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mittal M., Siddiqui M. R., Tran K., Reddy S. P., Malik A. B. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxidants & Redox Signaling. 2014;20(7):1126–1167. doi: 10.1089/ars.2012.5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rahal A., Kumar A., Singh V., et al. Oxidative stress, prooxidants, and antioxidants: the interplay. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:19. doi: 10.1155/2014/761264.761264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pham-Huy L. A., He H., Pham-Huy C. Free radicals, antioxidants in disease and health. International Journal of Biomedical Science. 2008;4(2):89–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bessada S. M. F., Barreira J. C. M., Oliveira M. B. P. P. Asteraceae species with most prominent bioactivity and their potential applications: a review. Industrial Crops and Products. 2015;76:604–615. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.07.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castells E., Mulder P. P. J., Pérez-Trujillo M. Diversity of pyrrolizidine alkaloids in native and invasive Senecio pterophorus (Asteraceae): implications for toxicity. Phytochemistry. 2014;108:137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jallali I., Zaouali Y., Missaoui I., Smeoui A., Abdelly C., Ksouri R. Variability of antioxidant and antibacterial effects of essential oils and acetonic extracts of two edible halophytes: Crithmum maritimum L. and Inula crithmoïdes L. Food Chemistry. 2014;145:1031–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.09.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zidorn C. Altitudinal variation of secondary metabolites in flowering heads of the Asteraceae: trends and causes. Phytochemistry Reviews. 2010;9(2):197–203. doi: 10.1007/s11101-009-9143-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhimi W., Ben Salem I., Immediato D., Saidi M., Boulila A., Cafarchia C. Chemical composition, antibacterial and antifungal activities of crude Dittrichia viscosa (L.) greuter leaf extracts. Molecules. 2017;22(7, article 942) doi: 10.3390/molecules22070942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alkafafy M., Montaser M., El-Shazly S. A., Bazid S., Ahmed M. M. Ethanolic extract of sharah, Plectranthus aegyptiacus, enhances healing of skin wound in rats. Acta Histochemica. 2014;116(4):627–638. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2013.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meda A., Lamien C. E., Romito M., Millogo J., Nacoulma O. G. Determination of the total phenolic, flavonoid and proline contents in Burkina Fasan honey, as well as their radical scavenging activity. Food Chemistry. 2005;91(3):571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chan E. W. C., Lim Y. Y., Ling S. K., Tan S. P., Lim K. K., Khoo M. G. H. Caffeoylquinic acids from leaves of Etlingera species (Zingiberaceae) LWT- Food Science and Technology. 2009;42(5):1026–1030. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2009.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prieto P., Pineda M., Aguilar M. Spectrophotometric quantitation of antioxidant capacity through the formation of a phosphomolybdenum complex: specific application to the determination of vitamin E. Analytical Biochemistry. 1999;269(2):337–341. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Molyneux P. The use of the stable radical diphenylpicrylhydrazyl (DPPH) for estimating antioxidant activity. Songklanakarin Journal of Science and Technology. 2004;26(2):211–219. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thaipong K., Boonprakob U., Crosby K., Cisneros-Zevallos L., Hawkins B. D. Comparison of ABTS, DPPH, FRAP, and ORAC assays for estimating antioxidant activity from guava fruit extracts. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis. 2006;19(6-7):669–675. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2006.01.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gouveia S., Gonçalves J., Castilho P. C. Characterization of phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of ethanolic extracts from flowers of Andryala glandulosa ssp. varia (Lowe ex DC.) R.Fern., an endemic species of Macaronesia region. Industrial Crops and Products. 2013;42(1):573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2012.06.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Velioglu Y. S., Mazza G., Gao L., Oomah B. D. Antioxidant activity and total phenolics in selected fruits, vegetables, and grain products. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 1998;46(10):4113–4117. doi: 10.1021/jf9801973. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang C. S., Lambert J. D., Ju J., Lu G., Sang S. Tea and cancer prevention: Molecular mechanisms and human relevance. Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology. 2007;224(3):265–273. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mullen W., Yokota T., Lean M. E. J., Crozier A. Analysis of ellagitannins and conjugates of ellagic acid and quercetin in raspberry fruits by LC-MSn. Phytochemistry. 2003;64(2):617–624. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(03)00281-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vallverdú-Queralt A., Jáuregui O., Di Lecce G., Andrés-Lacueva C., Lamuela-Raventós R. M. Screening of the polyphenol content of tomato-based products through accurate-mass spectrometry (HPLC-ESI-QTOF) Food Chemistry. 2011;129(3):877–883. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simirgiotis M. J., Benites J., Areche C., Sepu B. Antioxidant capacities and analysis of phenolic compounds in three endemic nolana species by HPLC-PDA-ESI-MS. Molecules. 2015;20(6):11490–11507. doi: 10.3390/molecules200611490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin L.-Z., Harnly J. M. Identification of the phenolic components of chrysanthemum flower (Chrysanthemum morifolium Ramat) Food Chemistry. 2010;120(1):319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.09.083. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang J.-G., Uchiyama T. Dehydrodimers of caffeic acid in the cell walls of suspension-cultured mentha. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry. 2000;64(4):862–864. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Llorent-Martínez E. J., Spínola V., Gouveia S., Castilho P. C. HPLC-ESI-MSn characterization of phenolic compounds, terpenoid saponins, and other minor compounds in Bituminaria bituminosa. Industrial Crops and Products. 2015;69:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.02.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stalmach A., Edwards C. A., Wightman J. D., Crozier A. Identification of (Poly)phenolic compounds in concord grape juice and their metabolites in human plasma and urine after juice consumption. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2011;59(17):9512–9522. doi: 10.1021/jf2015039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barros L., Pereira E., Calhelha R. C., et al. Bioactivity and chemical characterization in hydrophilic and lipophilic compounds of Chenopodium ambrosioides L. Journal of Functional Foods. 2013;5(4):1732–1740. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2013.07.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marczak Ł., Znajdek-Awizeń P., Bylka W. The use of mass spectrometric techniques to differentiate isobaric and isomeric flavonoid conjugates from Axyris amaranthoides. Molecules. 2016;21(9):p. 1229. doi: 10.3390/molecules21091229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Trimech I., Weiss E. K., Chedea V. S., et al. Evaluation of anti-oxidant and acetylcholinesterase activity and identification of polyphenolics of the invasive weed dittrichia viscosa. Phytochemical Analysis. 2014;25(5):421–428. doi: 10.1002/pca.2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kollia E., Markaki P., Zoumpoulakis P., Proestos C. Αntioxidant activity of Cynara scolymus L. and Cynara cardunculus L. extracts obtained by different extraction techniques. Natural Product Research (Formerly Natural Product Letters) 2017;31(10):1163–1167. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2016.1219864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pinelli P., Agostini F., Comino C., Lanteri S., Portis E., Romani A. Simultaneous quantification of caffeoyl esters and flavonoids in wild and cultivated cardoon leaves. Food Chemistry. 2007;105(4):1695–1701. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.05.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang M., Simon J. E., Aviles I. F., He K., Zheng Q.-Y., Tadmor Y. Analysis of antioxidative phenolic compounds in artichoke (Cynara scolymus L.) Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2003;51(3):601–608. doi: 10.1021/jf020792b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dawidowicz A. L., Typek R. Thermal stability of 5-o-caffeoylquinic acid in aqueous solutions at different heating conditions. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2010;58(24):12578–12584. doi: 10.1021/jf103373t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Albayrak S., Aksoy A., Sagdic O., Hamzaoglu E. Compositions, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of Helichrysum (Asteraceae) species collected from Turkey. Food Chemistry. 2010;119(1):114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2009.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Albayrak S., Aksoy A., Albayrak S., Sagdic O. In vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of some Lamiaceae species. Iranian Journal of Science & Technology. 2013;37(1):1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Özgen U., Mavi A., Terzi Z., Coflkun M., Ali Y. Antioxidant activities and total phenolic compounds amount of some asteraceae species. Turkish Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2004;1:203–216. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kenny O., Smyth T. J., Walsh D., Kelleher C. T., Hewage C. M., Brunton N. P. Investigating the potential of under-utilised plants from the Asteraceae family as a source of natural antimicrobial and antioxidant extracts. Food Chemistry. 2014;161:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akrout A., Gonzalez L. A., El Jani H., Madrid P. C. Antioxidant and antitumor activities of Artemisia campestris and Thymelaea hirsuta from southern Tunisia. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 2011;49(2):342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chahmi N., Anissi J., Jennan S., Farah A., Sendide K., El Hassouni M. Antioxidant activities and total phenol content of Inula viscosa extracts selected from three regions of Morocco. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2015;5(3):228–233. doi: 10.1016/s2221-1691(15)30010-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaiswal R., Kiprotich J., Kuhnert N. Determination of the hydroxycinnamate profile of 12 members of the Asteraceae family. Phytochemistry. 2011;72(8):781–790. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Silva D. B., Okano L. T., Lopes N. P., De Oliveira D. C. R. Flavanone glycosides from Bidens gardneri Bak. (Asteraceae) Phytochemistry. 2013;96:418–422. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2013.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fraisse D., Felgines C., Texier O., Lamaison L. J. Caffeoyl derivatives: major antioxidant compounds of some wild herbs of the Asteraceae family. Journal of Food and Nutrition Sciences. 2011;2(3):181–192. doi: 10.4236/fns.2011.230025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zidorn C., Ellmerer E. P., Sturm S., Stuppner H. Tyrolobibenzyls E and F from Scorzonera humilis and distribution of caffeic acid derivatives, lignans and tyrolobibenzyls in European taxa of the subtribe Scorzonerinae (Lactuceae, Asteraceae) Phytochemistry. 2003;63(1):61–67. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(02)00714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Danino O., Gottlieb H. E., Grossman S., Bergman M. Antioxidant activity of 1,3-dicaffeoylquinic acid isolated from Inula viscosa. Food Research International. 2009;42(9):1273–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2009.03.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Réblová Z. Effect of temperature on the antioxidant activity of phenolic acids. Czech Journal of Food Sciences. 2012;30(2):171–177. doi: 10.17221/57/2011-CJFS. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haiyan Z., Bedgood D. R., Jr., Bishop A. G., Prenzler P. D., Robards K. Effect of added caffeic acid and tyrosol on the fatty acid and volatile profiles of camellia oil following heating. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2006;54(25):9551–9558. doi: 10.1021/jf061974z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rawat S., Singh R., Thakur P., Kaur S., Semwal A. Wound healing agents from medicinal plants: a review. Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine. 2012;2(3):S1910–S1917. doi: 10.1016/s2221-1691(12)60520-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Song Y., Zeng R., Hu L., Maffucci K. G., Ren X., Qu Y. In vivo wound healing and in vitro antioxidant activities of Bletilla striata phenolic extracts. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2017;93:451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.06.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Infante J., Rosalen P. L., Lazarini J. G., Franchin M., De Alencar S. M. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of unexplored Brazilian native fruits. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(4, article e0152974) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agar O. T., Dikmen M., Ozturk N., Yilmaz M. A., Temel H., Turkmenoglu F. P. Comparative studies on phenolic composition, antioxidant, wound healing and cytotoxic activities of selected achillea L. species growing in Turkey. Molecules. 2015;20(10):17976–18000. doi: 10.3390/molecules201017976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Geronikaki A. A., Gavalas A. M. Antioxidants and inflammatory disease: synthetic and natural antioxidants with anti-inflammatory activity. Combinatorial Chemistry & High Throughput Screening. 2006;9(6):425–442. doi: 10.2174/138620706777698481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Graphic summary description: the ethanolic extract of D. viscosa leaves was leaves chemically characterized with HPLC-DAD-MS and it was used to formulate ointments (5% and 2.5% (w/w)) for healing wound test. Then, the antioxidants and the healing activities of those ointments were evaluated. The results obtained from this study revealed the excellent antioxidant potential of ointments base on ethanolic extract of D. viscosa and evidence their role in improving the rate and the quality of wound contraction samples.

Data Availability Statement

The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.