Abstract

Worldwide, people with mental disorders are detained within the justice system at higher rates than the general population and often suffer human rights abuses. This review sought to understand the state of knowledge on the mental health of people detained in the justice system in Africa, including epidemiology, conditions of detention, and interventions. We included all primary research studies examining mental disorders or mental health policy related to detention within the justice system in Africa. 80 met inclusion criteria. 67% were prevalence studies and meta-analysis of these studies revealed pooled prevalence as follows: substance use 38% (95% CI 26–50%), mood disorders 22% (95% CI 16–28%), and psychotic disorders 33% (95% CI 28–37%). There were only three studies of interventions. Studies examined prisons (46%), forensic hospital settings (37%), youth institutions (13%), or the health system (4%). In 36% of studies, the majority of participants had not been convicted of a crime. Given the high heterogeneity in subpopulations identified in this review, future research should examine context and population-specific interventions for people with mental disorders.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1186/s13033-019-0273-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Investments in mental health care and research are critical: globally, psychiatric and neurological disorders comprise approximately 13% of the disability-adjusted life years and nearly one-third of years lived with disability [1]. The prevalence of mental illness is higher among people detained within the justice system (PDJS) compared to the general population [2–9]. In this review, PDJS are defined as people detained or incarcerated in prisons, jails, youth institutions, or forensic inpatient units of hospitals. In accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO)’s definition, a forensic inpatient unit is “exclusively maintained for the evaluation or treatment of people with mental disorders who are involved with the justice system. These units can be located in mental hospitals, general hospitals, or elsewhere.” [10]. This review uses an inclusive definition of detention to respond to the scarcity of research on PDJS’s mental health in Africa, particularly for people detained outside of prisons. International systematic reviews on the mental health of PDJS show that populations in prisons are multiple times more likely to have several major mental disorders [2, 4, 5, 9] and have a three to sixfold higher risk of death by suicide [3]. More than 10 million people are held in penal institutions worldwide [11], and have increased risk of adverse outcomes such as all-cause mortality, suicide, self-harm, violence, and victimization [3]. The prevalence of mental disorders in African countries is of particular concern due to resource constraints for mental health and expansion of the movement to shift resources from institutions to community-based care in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) [12, 13]. In 2017, there were 2.5 total mental health beds per 100,000 population in African countries as a whole, 80% of which were in psychiatric hospitals [10], illustrating a contrast between where most existing mental health resources go (hospitals) and where services may be needed and, in reality, delivered (the community). There is, however, an international movement, including in Africa, to shift resources from a country’s psychiatric hospital or hospitals to other forms of mental health services [14, 15]. This movement recognizes that most people in low-resource settings have been receiving care in the community (if at all). However, in contexts with inadequate community health care, people previously in institutions may face increased risk of diversion to the justice system [15–18]. As health resources shift to better support mental health care in primary care and outpatient services in some African countries, research is needed on mental health interventions for justice-involved populations with elevated prevalence rates.

However, there has been minimal attention to the mental health of PDJS in international data collection and guidelines [19]. We surveyed United Nations (UN) and WHO guidelines on mental health and detained populations from the past 15 years (Table 1) and found that the mental health of PDJS has not been present in the majority of publications. The exclusion of the justice system from research or policy priorities contrasts to consensus in international prison literature which explicitly requires extensive mental health care services (see Table 1).

Table 1.

International guidelines on mental health and people detained within the justice system

| Document title, year of publication | Purpose | How does the document discuss mental health and detention? |

|---|---|---|

| WHO mental health action plan 2013–2020 (2013) [72] | An action plan for Member States which outlines ways to promote mental health, prevent mental disorders, protect human rights of persons affected by mental health conditions and to reduce mortality, morbidity and disability for people with mental disorders | Mental health: Large focus on four objectives: strengthening leadership and governance for mental health; expanding service coverage for mental disorders; implementing strategies for promotion and prevention in mental health, and strengthening the evidence base for mental health research |

| Detention: Mentions that inappropriate detention is more common for people with mental disorders and encourages collaboration with judicial sectors in all four objectives. Little is said about addressing the mental health of those that are specifically detained | ||

| Time to deliver, report of the who independent high-level commission on noncommunicable diseases (2018) [73] | Report aims to facilitate the implementation of Sustainable Development Goal 3.4, ‘reducing premature mortality from NCDs’, as progress so far has been inadequate | Mental health: Recognizes the global impact of mental disorders and specifically discusses mental health in each of its recommendations |

| Detention: No mention of people detained within the justice system | ||

| World Health Organization assessment instrument for mental health systems (AIMS 2.2) (2005) [74] | Document provides guidance on data collection for WHO AIMS 2.2, a tool for collecting information on key components of a mental health system | Mental health: Assessment tool assesses the following: policy and legislation, mental health services, mental health in primary health care, human resources, public education and links with other sectors, and monitoring and research |

| Detention: Includes the assessment of prison mental health services and forensic inpatient units | ||

| WHO mental health and development: targeting people with mental health conditions as a vulnerable group (2010) [75] | Report presents evidence showing that people with mental health conditions comprise a vulnerable group and provides recommendations for the implementation of policies that aim to protect this marginalized group | Mental health: Highlights the need for development programs to pay more attention to people with mental health conditions as they are among the most marginalized and vulnerable groups in society but are often overlooked |

| Detention: Recognizes that there is a significant problem to be addressed—people with mental health conditions are directed towards prisons, where they often do not have access to adequate mental health provisions and services | ||

| WHO checklist for evaluating a mental health policy (2005) [76] | A checklist for evaluating mental health policies | Mental health: Evaluates the process of policy development and the policy’s contents. Emphasizes a multisectoral, human-rights approach to developing policies |

| Detention: Suggests consulting with the justice system when developing policies but otherwise does not consider the mental health of detained people | ||

| UN General Assembly, Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for human rights: mental health and human rights (2017) [77] | To identify some of the main challenges faced by people with mental health conditions or psychosocial disabilities and recommends policies which would support the full realization of human rights of this population | Mental health: Emphasizes that human rights of persons with mental illnesses are vastly neglected in society. It stresses the importance of changing policies and law to protect the human rights of this vulnerable population |

| Detention: No mention of people detained within the justice system | ||

| UNOPS technical guidance on prison planning (2016) [78] | A guide to prison infrastructure development based on a human rights approach | Mental health: Recognizes that people detained in prisons with mental health conditions constitute a vulnerable group that may require separate accommodation |

| Health in prisons: Recognizes that there is a lack of practical guidance on prison infrastructure development which takes into consideration the Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners | ||

| UNODC handbook on prisoners with special needs (2009) [79] | Outlines the special needs of eight groups of adults in prisons which have a particularly vulnerable status and provides recommendations for policymakers | Mental health: Thoroughly describes the needs of people in prisons with mental health conditions and recognizes them as a vulnerable group. Highlights that promotion of mental well-being should be a key element of prison management and policies |

| Health in prisons: Recognizes that imprisonment is a disproportionately harsh punishment for many people in vulnerable groups. Suggests that their special needs are better addressed away from prisons, as the harsh prison environment would likely exacerbate any existing problems | ||

| United Nations expert group meeting on mental well-being, disability and disaster risk reduction (2014) [80] | Provides guidelines for countries’ Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) policies so that they include mental health and disability as a priority | Mental health: States the need to include mental well-being and mental disabilities in all DRR frameworks, as it optimizes resilience to disasters |

| Detention: No mention of people detained within the justice system | ||

| United Nations standard minimum rules for the treatment of prisoners (the Nelson Mandela Rules) (2015) [81] | Revised version of rules that set out the minimum standards for the treatment of people detained in prisons | Mental health: Highlights that all individuals with mental conditions in prisons should have access to the same care they would have in the community and should be transferred to a hospital if required |

| Health in prisons: Reaffirms that the punishment caused by imprisonment is by depriving individuals of liberty, so prison systems should not aggravate their suffering further |

Despite the burden of mental disorders among PDJS in Africa, research in this area is sparse [3, 19]. Existing international systematic reviews on the mental health of PDJS have either included studies in only one African country, Nigeria [2], or none at all [4, 5, 20, 21]. Moreover, these reviews do not report methodological bias or ethics procedures data of included studies, and the search criteria of most do not include institutions that detain justice-involved youth or inpatients in forensic psychiatry units [2, 4, 5, 21], even though this is where many people with mental illness may be detained and are similar to prisons in some countries [22]. A recent systematic review on the influence of prison climate on mental health resulted in studies from only high-income countries [21]. Similarly, a review of psychological therapies for PDJS internationally did not result in studies from LMIC countries other than India, Iran, and China [20]. Importantly, however, its search criteria included youth and participants in secure hospitals, while the other systematic reviews include only those in prisons and jails [2, 4, 5, 21].

Given the paucity of research focused on Africa and the resource constraints of these countries, this review aims to understand the scope of knowledge on the mental health of PDJS in Africa and to identify gaps in the literature, in order to inform future research, interventions, harm reduction, efforts, and policy. Given our study aims, we did not limit our search and selection to a single study design or outcome measure. In contrast to previous reviews investigating only prevalence, specific study types, or restricted to prisons, the broad scope of this review responds to the scarcity of research in African contexts and the systems-wide nature of detention and issues surrounding the mental health of PDJS.

Methods

The review followed guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) [23], and the meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) [24], both of which are found in Additional file 1: Appendices S1 and S2. The protocol was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO). The Registration Number is CRD42018098852.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched PubMed, PsycINFO, Embase, Web of Science, and Africa Index Medicus for studies dating from the inception of the database to 16 November 2017, and published in English or French, major research languages on the African continent. Because the inception of databases are constantly updated as new articles are digitized, searches were run without date limits. These databases represent major features of this paper: international health databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science), a psychiatry-specific database (PsycINFO), and an Africa-specific database (African Index Medicus). Africa Index Medicus is managed by the WHO, and is one of two major African health databases. The other is African Journals Online, which is not health specific. Our search strategy included terms related to the following ideas: (1) Africa (defined as the WHO Africa Region [25]), (2) detention or incarceration, and (3) mental health. Search syntax and controlled vocabulary words were modified for each database. Complete search terms for each database are in Additional file 1: Appendix S3.

Only primary research studies published in peer reviewed journals in English or French that met the following PICOS criteria were included. Participants included any people detained by the state, regardless of whether they had been sentenced to a crime. We excluded people formerly detained if data was collected after their release, and excluded people detained for immigration (similar to prior research on detained populations) [3]. We included studies that related to a mental illness as defined according to the DSM-V, but included studies that used other diagnostic criteria. Due to the scarcity of systematic research in this area, we included both qualitative and quantitative studies, including systematically collected data on policy, health systems, and conditions of detention, such as availability of physical or human resources, services, and the legal process. We included studies in the WHO Africa Region [25] and in any setting in which people were involuntarily held by the government for being accused or convicted of committing a crime. We excluded the settings of house arrest or non-forensic psychiatric hospitals in which people are involuntarily committed for disease alone.

Data collection

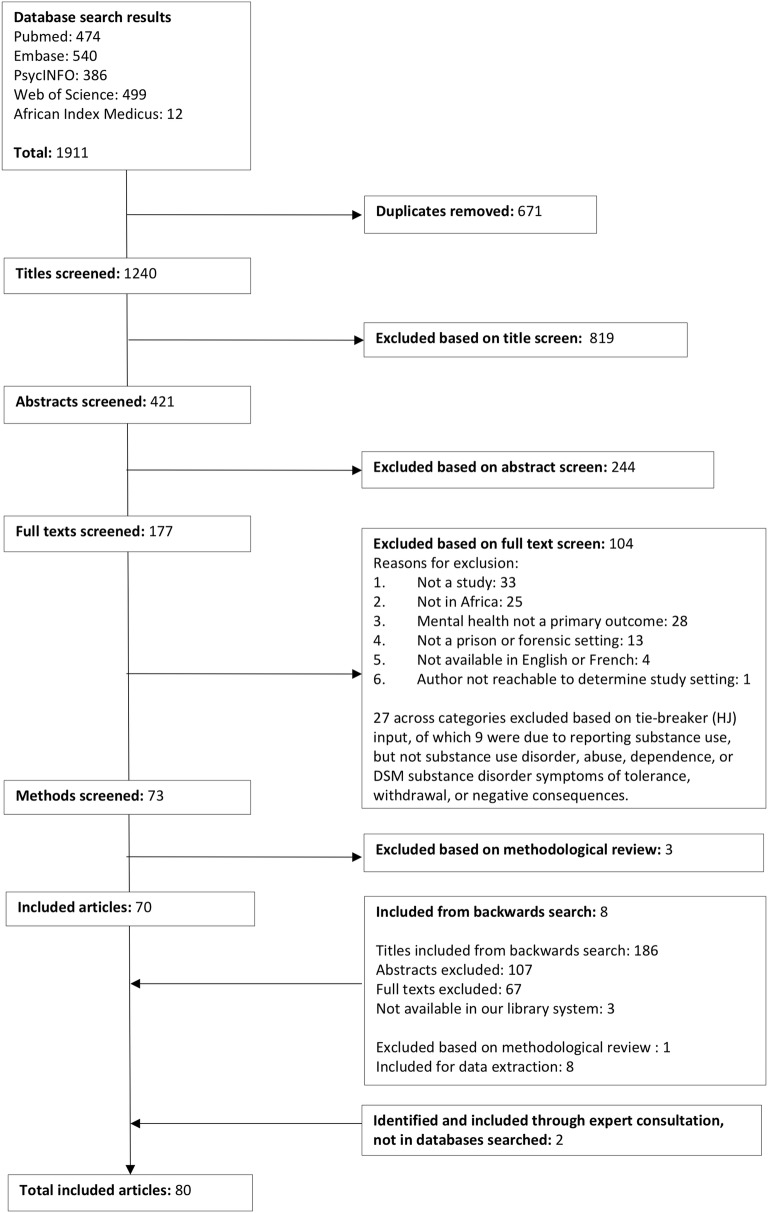

After the search was conducted and duplicates removed, two researchers (AL, HK—trained undergraduate students) separately screened the titles, abstracts, and full texts of studies to assess whether they met the inclusion criteria, reconciling differences between each step through discussion. A third reviewer (HJ) acted as a tie breaker if the other screeners could not come to consensus. Following the full text screen, a backward search was conducted on all articles selected for inclusion. The results of the backward search were screened for inclusion following the same protocol as the initial search results (Fig. 1). If a paper identified could not be located using multiple university library systems, we attempted to contact the study author. If the author could not be contacted, we excluded this paper as it was not possible to access the full text. We did not contact authors to obtain missing data or details on methods.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias was assessed using the following separate tools for each study type. Pre-post studies: Quality assessment tool for quantitative studies [26]; RCTs: Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias [27]; qualitative: Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) Checklist for Qualitative Studies [28]; prevalence: Prevalence Critical Appraisal Checklist [29]. We did not assess risk of bias for validation studies or structured reviews of health systems. The small number of these studies included in the review and the methodologic heterogeneity of structured reviews or descriptions of health systems make them difficult to compare with a single tool. We did not report a single overall risk of bias score for each study, as these scores typically involve arbitrarily weighting different domains of risk of bias [30]. Rather, we reported grouped studies into categories of high, medium, and low risk of bias based on the overall assessment generated by the methods assessment instruments. The methodological assessment was used to exclude studies that had either (1) insufficient information on methods or (2) a clear methodological flaw or inconsistency.

Data extraction

Data on study characteristics, sample characteristics, and study outcomes were extracted from each study (Tables 2, 3). Systematic reviews have the potential to elevate studies with poor ethics standards [31]; therefore, we extracted data on the presence or absence of documentation of an ethics committee review and informed consent procedures. If institution conditions or the laws or policy of the health or justice system were described, we extracted these descriptions and categorized the data into common findings (Additional file 1: Appendix S9).

Table 2.

Prevalence studies

| Reference *If same sample as another study in list | Study design | Study setting | Country setting | Comparison [If yes (Y), describe; no (N)] | Strategy, whether sample size calculation was reported for non-census strategies | Ethics reporting (documented ethics committee approval; described informed consent procedure) | Participants characteristics (sample size, mean age, percent male) *Indicates gender as inclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria (excluding age criteria) | Trial status category (C = over 50% convicted; NC = over 50% not convicted; NC/A = over 50% “awaiting trial”; JI = over 50% youth justice-involved; U = unclear; NA = not applicable; NS = not stated) | Assessment instruments (diagnostic or screening tool) | Primary outcomes (p-value listed if provided in study) | Methods risk of bias score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdulmalik et al. 2014 [82] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Census | Yes, Yes | 725, 31.1, 98.7% | Awaiting trial and remanded; GHQ-12 ≥ 5 for phase 2 | NC/A *Awaiting trial | GHQ-12 (S), MINI (D) | 56.6% prevalence of mental illness (MINI), assessed after scoring ≥ 5 GHQ-12. Depression 20.8%; alcohol dependence 20.6%; substance dependence 20.1%; suicidality 19.8%; antisocial personality disorder 18%; panic disorder 8.3%; OCD 8.3%; PTSD 3.3%; GAD 2.8%; psychosis 1.1% | Low |

| Agbahowe et al. 1998 [83] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Census | No, No | 100, 31.4, 93% | Convicted; GHQ-30 > 4 for phase 2 | C *Convicted and no other classification (81%), convicted but detained (6%); convicted and condemned to death (13%) | GHQ-30 (S), Psychiatric Assessment Schedule (PAS) (D), SCAN (D) | 34% ≥ 4 score on GHQ-30; 100% of GHQ-30 ≥ 4 cases had DSM IIIR Axis I diagnosis | Low |

| Agboola et al. 2017 [84] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Random, N | Yes, Yes | 94, 28.5, 100%* | Male | NS, awaiting trial and convicted | GHQ-28 (S), Present State Examination (PSE) (D), PULSES (S) | 39% prevalence of psychiatric morbidity (PSE). As measured by PSE, 20.2% of total participants diagnosed with depression; 14.8% anxiety; 3.2% schizophrenia; 1.1% mania; 1.1% OCD. 57.4% participants scored ≥ 5 on the GHQ-28. Of participants with psychiatric diagnosis, 39.7% with co-morbid physical illness (PULSES) | Low |

| Akkinawo 1993 [85] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Random, NS | No, No | 136, NS, 93.4% | NA | NS | API (S), BDI (S) | 20.86% depression (BDI); 35.29% general mood disorder; 30.15% general psychopathology; 26.47% sleep disorder (API) | Medium |

| *Armiya’u et al. 2013 “Prevalence of…” [86] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | NS | No, No | 608, 32.1, 100%* | Males (though unclear); NA for phase 1, > 4 GHQ-28 for phase 2 | NC/A *60% awaiting trial, 40% convicted | GHQ-28 (S), CIDI (D) | 57% psychiatric morbidity (CIDI), administered to those with GHQ-28 score ≥ 4 | Medium |

| *Armiya’u et al. 2013 “A study of…” [87] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | NS | Yes, No | 608, 32.1, 100%* | Males (though unclear); NA for phase 1, > 4 GHQ-28 for phase 2 | NC/A *60% awaiting trial, 40% convicted | GHQ-28 (S), PULSES (S), CIDI (D) | 57% psychiatric morbidity (CIDI), administered to those with GHQ-28 score ≥ 4. 18% prevalence of co-morbid physical illness (comorbid illness indicated by PULSES) | Medium |

| *Beyen et al. 2017 [88] | Prevalence | Prison | Ethiopia | N | Random, Y | Yes, Yes | 649, 27.8, 89.8% | NA | NS | GAD-7 (S), K10 (S), PHQ-9, (S) OSS (S), questionnaire (S) | 83.4% psychological distress (K10); 43.8% signs of depression (PHQ-9); 36.1% anxiety (GAD-7); 45.1% without social support (OSS). 17% suicidal ideation; 16.6% already planned to commit suicide; 11.9% at least one suicide attempt while in prison (questionnaire) | Low |

| *Dachew et al. 2015 [89] (same sample as Beyen) | Prevalence | Prison | Ethiopia | N | Random, Y | Yes, Yes | 649, 27.8, 89.8% | NA | NS | K10 (S), questionnaire (S), MSPSS (S) | 83.4% psychological distress (K10). 43.6% of the respondents feel that they had been discriminated by their families, friends and significant others because of their imprisonment (questionnaire or MPSS, source not stated). 64.7% “yes” reported social support; 35.3 “no” (MPSS) | Low |

| *Dadi et al. 2016 [90] (same sample as Beyen) | Prevalence | Prison | Ethiopia | N | Random, Y | Yes, Yes | 649, 27.8, 89.8% | NA | NS | GAD-7 (S) | 36.1% anxiety (GAD-7) | Low |

| Fatoye et al. 2006 [91] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Census | No, Yes | 303, 31.2, 96.4% | NA | NC/A *81.3% awaiting trial, 18.7% sentenced | GHQ-30 (S), HADS (S) | 87.8% possible psychiatric morbidity (GHQ-30 ≥ 5). 85.3% HADS ≥ 8 significant depressive symptoms | Low |

| Ibrahim et al. 2015 [92] | Prevalence | Prison | Ghana | N | Random and census, NS | Yes, Yes | 100, 37, 89% | NA | NS | K10 (S) | 64% K10 scores ≥ 25 indicating moderate to severe mental distress | Low |

| Kanyanya 2007 [93] | Prevalence | Prison | Kenya | N | Census | No, Yes | 76, 33.5, 100%* | Males, convicted of sex offense | C | SCID (D), IPDE (D) | 35.5% DSM-IV Axis 1 disorder (SCID). 34% prevalence of DSM-IV Axis 2 disorders (SCID and IPDE) | Medium |

| *Mafullul 2000 [94] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Census | No, No | 118, 33.9, 96% | Convicted of homicide | C | Psychiatric record (D) | Psychotic disorders and substance use disorders, including alcohol intoxication, suggested to be held to accountable for 39.8% persons’ offenses. 45% of participants had positive histories of substance use disorders | High |

| *Mafullul et al. 2001 [95] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Census | Yes, No | 118, 33.9, 96% | Convicted of homicide | C | Psychiatric record (D) | 68% of the accused referred for pre-trial psychiatric assessment had killed victims as a result of psychotic motives. Court recognized that alcohol intoxication and psychotic motives accounted for the offenses of 24% of the accused. Study indicates that substance use disorders may have accounted for offenses of 45% of accused | High |

| Majekodunmi et al. 2017 [96] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Random, Y | Yes, Yes | 196, 32.8, 100%* | Male, those with no past treatment for mental illness, no debilitating physical illness | NC/A, 69.4% awaiting trial, 30.6% convicted | SCID-IV (D), Montgomery–Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (S),, Medical history questionnaire (S) | 30.1% depression; mean total MADRS score 23.9 among awaiting trial participants. 35.0% depression; mean total MADRS score 25.5 among awaiting trial participants. From medical history questionnaire, resence of physical complaints (p = 0.014) and chronic illness (p = 0.023) associated with depression among awaiting trial participants; family history of psychiatric illness associated with depression among convicted participants (p = 0.046) | Low |

| Mela et al. 2014 [97] | Prevalence | Prison | Ethiopia | N | Census | Yes, Yes | 546, NS, 94.3% | Convicted of homicide | C | SRQ-20 (S) SCID-IV (D) | 35.5% SRQ-indicated psychological distress. Among 316 participants who agreed to undergo a psychiatric interview for Axis I diagnosis (SCID-IV), 41.8% history of substance use disorder; 25% depression; 10.1% adjustment disorder; 7.6% anxiety disorder; 0.6% PTSD; 0.6% psychotic disorder; 1.6% psychotic disorder due to medical condition; 15.8% personality disorder (SCID) | Low |

| Naidoo and Mkize 2012 [98] | Prevalence | Prison | South Africa | N | Random, Y | Yes, Yes | 193, 30.5, 95.8% | NA | C *62% convicted, 38% awaiting trial | MINI (D) | 55.4% Axis 1 disorder from MINI | Medium |

| Nseluke and Siziya 2011 [99] | Prevalence | Prison | Zambia | N | Random, Y | Yes, Yes | 206, 33.7, 83% | NA | NC/A *74.3% awaiting trial, 23.3% sentenced, 1.9% probation violation, 0.5% parole violation | SRQ (S) | 63.1% mental illness as indicated by SRQ | Low |

| Osasona and Koleoso 2015 [100] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Random and census, NS | Yes, Yes | 252, 33.7, 90.9% | NA | C *57.1% sentenced, 42.9% awaiting trial | SRQ-20 (S), HADS (S) | 84.5% of the respondents had at least one type of psychiatric morbidity (SRQ and HADS combined). Prevalence of general psychiatric morbidity, SRQ-20 score ≥ 5, 80.6%. 72.6% and 77.8% were found to be positive for depression and anxiety symptoms respectively on the HADS | Low |

| Schaal et al. 2012 [101] | Prevalence | Prison | Rwanda | Y (genocide survivors) | Random, NS | Yes, Yes | 269, 48.5, 65.8% (genocide perpetrators); 114, 46.6, 36.3% (survivors) | Perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide, over 18 years in 1994 | C *89.6% convicted, 10.4% not sentenced | PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview (PSS-I) (D), PDS Event Scale (S), Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25 (HSCL-25) (S), suicidality scale from the MINI (S) | Diagnostic criteria for PTSD met by 13.5% perpetrators and 46.4% of interviewed survivors (p < 0.001) (PSS-I). Clinically significant anxiety prevalence 35.8% among perpetrators (HSCL-25); 58.9% among survivors (p < .001). Depression in both groups (46% survivors vs. 41% perpetrators) (HSCL-25). 18.6% perpetrators and 19.3% survivors had suicide risk (MINI). Perpetrators with more severe depression symptoms (HSCL-25) reported high levels of trauma confrontation (PDS) and had not participated in killings | Low |

| *Uche and Princewill 2015 “Clinical factors…” [102] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Random, Y | Yes, Yes | 400, 33.8, 98% | Awaiting trial; BDI-screen positive for phase 2 | NC/A* awaiting trial | BDI (S), SCAN Depression Component (D) | 42% BDI > 10 screen fulfilling the criteria for current depressive disorder. 42% fulfilled SCAN criteria for current depression disorder diagnosis | Low |

| *Uche and Princewill 2015 “Prevalence…” [103] | Prevalence | Prison | Nigeria | N | Random, Y | Yes, Yes | 400, 33.8, 98% | Awaiting trial; BDI-screen positive for phase 2 | NC/A *89% awaiting trial, 5% convicted, 0.1% assigned legal category of “lunatics,” death row condemned 5%, serving life imprisonment jail terms 0.5% | BDI (S), SCAN depression component (D) | 42% BDI > 10 screen fulfilling the criteria for current depressive disorder. 42% fulfilled SCAN criteria for current depression disorder diagnosis | Low |

| Barrett et al. 2007 [52] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | Yes, No | 71, NS, 94.4% | Psychiatric referrals | NC *Detained “state patients” accused but found unfit to stand trial or not responsible, referred to forensic ward | Psychiatric record (D) | Schizophrenia (35.2%), mental retardation (22.5%) and psychoses other than schizophrenia (11.3%) most prevalent, followed by bipolar disorder (5.6%). 84.5% not able to stand trial and not accountable; 7% not fit to stand trial and accountable; 8.5% not accountable and fit to stand trial | Medium |

| Buchan 1976 [104] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Zimbabwe | N | Census | No, No | 256, NS, NS | Psychiatric referrals | U *Referrals to hospital | Psychiatric record (D) | Prevalence of schizophrenia 44%; epilepsy 22% | High |

| Calitz et al. 2006 [105] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | Yes, No | 514, 30 (median), 94.6% | Psychiatric referrals | NC/A *Awaiting trial, referrals to hospital | Psychiatric record (D) | 46% psychiatric prevalence. | Medium |

| du Plessis et al. 2017 [106] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | Yes, No | 505, NA, 94% | Awaiting trial; psychiatric referrals | NC/A *Awaiting trial, referrals to hospital | Psychiatric record (D) | Those not accountable significantly more likely to have mental illness (p = 0.0001) and be diagnosed with schizophrenia (p = 0.0001), intellectual disability (p = 0.0001), and substance-induced psychotic disorder (p = 0.02) than those not accountable. 98% of those found not accountable had mental illness. 66% total sample had known history of substance abuse | Low |

| Hayward et al. 2010 [107] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Malawi | N | Census | No, No | 283, 30.4, 91.5% | Psychiatric referrals | U *Detained in hospital | Psychiatric record (D) | Prevalence of schizophrenia 35.5%; substance misuse 32.5%; 19.8% alcohol and 23% illicit substance; depression 3%; mania or personality disorder 0%; epilepsy 8.1% | Medium |

| Hemphill and Fisher 1980 [108] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | No, No | 604, NS, 100%* | Males (though unclear); psychiatric referrals | NC *Pre-trial referrals to hospital | Psychiatric record (D) | 52% substance abuse of drugs, alcohol, or both. Prevalence of psychosis (53%), severe psychopathy without psychosis (21%), and non-psychotic conditions including neurosis, mild personality disorder, eplepsy and mental retardation (26%). More than 70% of patients with psychopathy screened positive for substance abuse of alcohol, drugs or both | High |

| Khoele et al. 2016 [109] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | Yes, No | 32, 29.8, 0% | Women; charged with murder or attempted murder, psychiatric referrals | NC *Pre-trial referrals to hospital | Psychiatric record (D) | 59% psychiatric diagnosis; 28% psychotic; 25% mood disorders; 6% substance disorders; 19% attempted suicide | Medium |

| Marais and Subramaney 2015 [53] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | Yes, Yes | 114, 32, 87% | Psychiatric referrals | NC *Detained “state patients” accused but found unfit to stand trial or not responsible, referred to forensic ward | Psychiatric record (D) | Past psychiatric history (59%); substance abuse history (71%). 69% psychotic disorders; 44% schizophrenia. Bipolar mania 4%; major depressive disorder 4%; epilepsy 4%. Alcohol the most frequently abused substance (57%); cannabis 47%. 37% reported a history of polysubstance abuse | Medium |

| Matete 1991 [110] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Kenya | N | Census | No, No | 51, 28.8, 90.2% | Psychiatric referrals | NC *Detained in hospital: court referrals to hospital, referred to as “criminal remands” | Psychiatric record (D) | 86.3% mental illness | Medium |

| Mbassa 2009 [111] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Cameroon | N | Random, NS | No, No | 12, 18.3, 66.7% | Convicted of homicide | C *Convicted, detained in hospital | Psychiatric record, ICD-10 criteria (D) | 41.7% schizophrenia; delirium 25%; personality disorder 8.3% | High |

| Menezes 2010 [112] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Zimbabwe | N | Census | Yes, Yes | 39, 35.0, 87.2 | Homicide offense, psychiatric referrals | NC *Detained in hospital: court referrals to hospital, referred to as “criminal remands” | Psychiatric record (D), questionnaire (S) | 84.61% schizophrenia or psychosis; 2.56% personality disorder; 12.82% epilepsy | Medium |

| Menezes et al. 2007 [113] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Zimbabwe, England, Wales | Y (referral patients in England and Wales) | Census | Yes, Yes | 367, 36.0, 91.8% (Zimbabwe); 1966, 29.7, 83.6% (England/Wales) | Psychiatric referrals | U *Referrals to hospital | Psychiatric record, ICD-9 criteria (D), questionnaire (S) | 78.7% of patients in Zimbabwe had a mental disorder diagnosis compared with 51.5% in England and Wales (p < 0.001). 6.3% had personality disorder diagnosis in Zimbabwe; 36.6% in England and Wales | Medium |

| Odejide 1981 [114] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Nigeria | N | Census | No, No | 53, 38.7, 83% | Psychiatric referrals | U *Referrals to hospital | PSP (D) | 75.5% schizophrenia; 5.7% drug-induced psychosis; 18.9% epilepsy (PSP) | Medium |

| Offen et al. 1986 [115] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | No, No | 162, 20–40, 0% | Psychiatric referrals | U *Referrals to hospital | Psychiatric record (D) | 82% had psychiatric abnormality, including 34% of total sample with significant psychiatric findings, but these were not considered of a critical enough nature to warrant the label “mental illness.” | Medium |

| Ogunlesi et al. 1988 [116] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Nigeria | N | Census | No, No | 146, 34.5, 98% | Psychiatric referrals | NC *Pre-trial referrals to hospital. Not convicted at time of diagnosis, but later conviction data provided | Psychiatric record (D) | 45% schizophrenia; 4% mania; 3.3% depression; 0.7% paranoid state; 19.5% total drug abuse/dependence; 16.8% cannabis abuse; 2.7% alcoholism; 6.7% epilepsy. 75% had a previous history of psychiatric disorder; 45% admitted a previous history of drug abuse. 48% judged “criminal lunatics” either not guilty by reason of insanity or guilty but insane. 30% discharged by courts; 1 sentenced to death; 1 sentenced to a prison term. 46.3% of offenders absconded from the institution | Medium |

| Prinsloo and Hesselink 2014 [117] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Purposive, NS | No, No | 91, NS, 100% | Psychiatric referrals | NC *Pre-trial referrals to hospital | Psychiatric record (D) | 83.5% at least one mental health disorder | Medium |

| Strydom et al. 2011 [54] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | Yes, No | 120, 32.5, 95.8% | Psychiatric referrals | NC *Detained “state patients” accused but found unfit to stand trial or not responsible, referred to forensic ward | Psychiatric record (D) | Most had a history of abusing substances such as alcohol (74%), cannabis (66.7%), tobacco (29.6%) and glue (6.2%). 55.5% diagnosed with schizophrenia; 9.2% bipolar mood disorder; 5.9% psychosis due to general medical condition; 4.2% psychosis due to epilepsy; 3.4% psychosis due to substance abuse; 1.7% delirium; 10% other disorder | Medium |

| Touari et al. 1993 [118] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Algeria | N | Census | No, No | 2882, 30.1, 94.3% | Psychiatric referrals | NC *Pre-trial | Psychiatric record (D) | 11.1% diagnosis of psychosis. 1.4% diagnosis of manic depression | Medium |

| Turkson and Asante 1997 [55] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Ghana | N | Census | No, No | 130, NS, 94.6% | Psychiatric referrals and state patients | NC *Detained in hospital: Pre-trial, convicted, or found unfit to stand trial. Participants were “predominantly patients who had been found guilty but insane or those found unfit to proceed with their trial” due to “insanity” | Psychiatric record (D) and clinical observation by author (S) | 81.6% had a psychiatric diagnosis as indicated by clinical records. At the time of the study, 70.9% of total patients exhibited no florid psychotic symptoms, all patients with a diagnosis of harmful drug use were free from symptoms; 93.8% diagnosed with drug-induced psychosis were fully recovered | Medium |

| Verster and Van Rensburg 1999 [119] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | Yes, No | 126, NS, 98.4% | Have homicide offense and psychiatric referrals | NC *Pre-trial referrals to hospital | Psychiatric record (D) | 42.1% had a psychiatric diagnosis | Medium |

| Yusuf and Nuhu 2009 [120] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | Nigeria | N | Census | No, No | 19. 28.9, 73.7% | Psychiatric referrals | NS | Psychiatric record (D) | Schizophrenia was the most common psychiatric disorder (68.4%), co-morbid substance use present in 57.9% | Medium |

| Zabow 1989 [121] | Prevalence | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | No, No | 202, NS, 90% | Homicide convicts | NC *Pre-trial referrals to hospital | Psychiatric record (D) | 15.8% prevalence of “significant psychiatric findings.” Alcohol and drugs were contributory to the criminal behavior in 50% of cases. The number of murders committed increased by 25.2% in 1977–1984 compared to an increase of 115.8% in the number of psychiatric referrals during the same period. Following hospital assessment, 60.4% had no psychiatric diagnosis | Medium |

| Atilola et al. 2014 [7] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | Y (school-going adolescents, age matched but school-going youth slightly younger. Detained youth 18.7 ± 2.4 years old [Range 16–20 years] vs. school kids 18.2 ± 2.5 [Range 15–19 years]) | Census | Yes, No | 144, 18.7, 100% (participants in Borstal home); 144, 18.2, 100% (school-going youth) | NA | JI *Detained in borstal institution in juvenile justice system: classified 52.1% juvenile offenders; 47.9% youth beyond parental control (no offense) | K-SADS-PL (D) | 90% of the justice-involved youth in borstal home reported exposure to at least one lifetime traumatic event, compared with 60% of the comparison group (p = 0.001). Justice-involved youth also had a higher mean number of incident lifetime traumatic events (p < 0.001), and higher prevalence rate of current and lifetime PTSD than the comparison group (p < 0.05). Justice-involved more likely to be victims of violent crime (p < 0.001), have experienced physical abuse (p < 0.001), and be perpetrators of a violent crime (p = 0.002) (K-SADS-PL) | Low |

| Atilola 2012 “Different points…” [122] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | Y (within-institution comparison of youth on criminal code vs. youth in care of state/neglected youth) | Census | Yes, Yes | 158, 17.5, 96. % (criminal code group); 53, 12.5, 74% (in care of state) | NA | JI *75% criminal code or beyond parental control, 25% due to maltreatment/neglect | K-SADS (D) | Conduct/behavior disorders had 63% prevalence among “criminal code” youth vs. 39%, among neglect group (p < 0.001). Prevalence of multiple traumatic events 27% among criminal code youth; 26%, neglect group (p = 0.43). PTSD prevalence 13% among criminal code youth; 22% among neglect group (p = 0.12). Substance use prevalence was 61% among those on criminal code compared to 11% youth detained due to neglect/maltreatment (p = 0.003) (all K-SADS) | Medium |

| Atilola 2012 “Prevalence and correlates…” [6] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | Y (school-going adolescents, age and gender matched, randomly selecter) | Census | Yes, Yes | 60 (in remand home), 60 (school-going), 12.5* (pooled), 66.6%* (pooled) *Only pooled statistics given |

NA | NC *77% in home due to maltreatment/neglect, 10% classified as “offenders,” 13% beyond parental control | K-SADS-PL (D) | 63% remanded participants had at least one lifetime psychiatric disorder compared to 23% control (p < .001); 22% had at least one current psychiatric disorder compared to 3% control (p < .004) (K-SADS-PL) | Medium |

| Atilola et al. 2016 [50] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | Y (within-institution comparison of “criminal code” vs. other groups) | Random, NS | Yes, Yes | 178, 15.19, 61.8% (total participants, pooled) | NA | NC *19.1% classified “young offenders,” 73.6% care and protection of state, 7.3% beyond parental control | K-SADS (D) | Lifetime prevalence rate of abuse of/dependence on any substance was 22.5%. 12.3% alcohol abuse/dependence; 17.9% other substance abuse/dependence. Higher proportion of participants who were remanded under the ‘young offender’ category met criteria for lifetime substance use disorder compared with those under the care and protection and beyond-parental-control category (p = 0.004). Length of staying on the streets or by self was associated with problematic use (abuse or dependence) (p = 0.007) (K-SADS) | Low |

| *Atilola et al. 2017 “Correlations…” [123] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | N | Random, NS | Yes, Yes | 165, 14.3, 75% | NA | NS *Remanded youth: criminal code, neglected/in care of state, or beyond parental control | SDQ (S), PedsQo (S) | 18% abnormal SDQ score suggesting presence of psychiatric disorder; 27% had ‘highly probable’ psychopathology (SDQ). Negative correlation (p < 0.001) between total SDQ scores and overall self-reported quality of life (PedsQo) | Low |

| *Atilola et al. 2017 “Status…” [124] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | N | Random, NS | Yes, Yes | 165, 14.3, 75.2% | NA | NS *Remanded youth: criminal code, neglected/in care of state, or beyond parental control | SDQ (S), CRAFFT (S), questionnaire (S), Audit Protocol (S) | 18.2% general psychiatric morbidity by SDQ ≥ 17; 44.6% prevalence SDQ ≥ 15; 15.8% alcohol/substance use disorder (CRAFFT > 2). 34.3% of the operational staff at the institutions had educational backgrounds relevant to psychosocial services for children/adolescents. Less than a quarter (22.4%) ever received any training in child mental health services (questionnaire and Audit protocol) | Low |

| *Adegunloye et al. 2010 [125] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | N | Census | No, No | 53, 17.3, 100% | NA | JI * Detained in borstal institution in juvenile justice system | GHQ-12 (S), MINI-KID (D) | 67.9% current psychiatric disorder (MINI-KID). GHQ scores not reported | Low |

| *Ajiboye et al. 2009 (same sample as Adegunloye) [126] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | N | Census | No, Yes | 53, 17.3, 100% | NA | JI * Detained in borstal institution in juvenile justice system | GHQ-12 (S), MINI-KID (D) | 67.9% current psychiatric disorder (MINI-KID). GHQ scores not reported | Low |

| *Issa et al. 2009 (same sample as Adegunloye) [127] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | N | Census | Yes, Yes | 53, 17.3, 100% | NA | JI * Detained in borstal institution in juvenile justice system: classified “juvenile offenders” or those “in need of correction” | GHQ-12 (S) | 49.1% GHQ-positive (> 3 on GHQ-12), indicating possible psychiatric morbidity | Medium |

| *Yusuf et al. 2011 (same sample as Adegunloye) [128] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | N | Census | No, Yes | 53, 17.3, 100% | NA | JI * I Detained in borstal institution in juvenile justice system | GHQ-12 (S), MINI-KID (D) | 50.9% had MINI-KID lifetime psychiatric diagnoses. Majority (62.3%) had psychiatric problems in the past 12 months. When all lifetime and current psychiatric diagnoses were collapsed, 98.1% had ‘any psychiatric disorder. 49.1% GHQ-12 > 3, indicating possible psychiatric morbidity | Low |

| Bella et al. 2010 [51] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | N | NS | No, Yes | 59, 11.7, 60% | NA | NC *90% under care and protection of state, 7% beyond parental control, 3% criminal code/“youth offenders” | K-SADS (D) | 100% had significant psychosocial needs presenting as difficulty with their primary support, social environment, or education systems. 97% demonstrated some form of psychopathy | Medium |

| *Olashore et al. 2016 [129] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | N | Census | Yes, Yes | 148, 17.1, 100% | NA | JI * Detained in borstal institution under criminal code or beyond parental control; 40.8% detained for “non-delinquent reason” | MINI-KID (D) | 56.5% met the criteria for conduct disorder (MINI-KID). Number of siblings (p = 0.010) and previous history of detention (p = 0.043) were independent predictors of CD | Low |

| *Olashore et al. 2017 [130] | Prevalence | Youth Institution | Nigeria | N | Census | Yes, Yes | 148, 17.1, 100% | NA | JI * Detained in borstal institution under criminal code or beyond parental control; 40.8% detained for “non-delinquent reason” | MINI-KID (D) | 56.5% met the criteria for conduct disorder (MINI-KID). Substance use, depression, or oppositional defiant disorder not significantly associated with “offender” status. CD is associated (p < .001) with “offender” status | Low |

Table 3.

All other study designs

| Reference *If same sample as another study in list | Study design | Study Setting | Country setting | Comparison [If yes (Y), describe; no (N)] | Strategy, Whether sample size calculation was reported for non-census strategies | Ethics reporting (documented ethics committee approval; described informed consent procedure) | Participants characteristics (sample size, mean age, percent male) *Indicates gender as inclusion criteria | Inclusion criteria (excluding age criteria) | Trial status category (*1) (C = over 50% convicted; NC = over 50% not convicted; NC/A = over 50% “awaiting trial”; JI = over 50% youth justice-involved; U = unclear; NA = not applicable; NS = not stated) | Assessment instruments (diagnostic or screening tool) | Primary outcomes (p-value listed if provided in study) | Methods risk of bias score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eseadi et al. 2017 [42] | Pre-post | Prison | Nigeria | Y (15 treatment, 15 control group not receiving intervention) | Census | Yes, Yes | 15, NS, 100% (treatment); 15, NS, 100% (control) | BDI score ≥ 29 | NS *But 84% awaiting trial in the prison population from which the sample was selected | BDI (S) | Significant treatment by time interaction effect for cognitive behavioral coaching program on depression as measured by BDI (p = 0.000). Significant decrease from pre to post-test BDI score (p = 0.000) for the CBC group compared to control | Low |

| Onyechi et al. 2017 [43] | Pre-post | Prison | Nigeria | Y (10 treatment, 10 control group not receiving intervention) | Census | Yes, Yes | 10, NS, 100% (treatment); 10, NS, 100% (control) | High scorers on CDS-12 | NS | CDS-12 (S) | After the cognitive behavioral intervention, prisoners in the treatment group has significantly lower post-intervention CDS-12 scores than the control group’s post-intervention scores (p = 0.00) | Medium |

| Martyns-Yellowe 1993 [44] | RCT | Prison | Nigeria | Y (18 participants each in treatment groups receiving Flupenthixol or Clopenthixol injections) | Census | No, No | 18, NS, 100%* (Flupenthixol treatment); 18, NS, 100%* (Clopenthixol treatment) | Males; schizophrenia diagnosis; vagrant people removed from public places by law enforcement | U *Detained in prison asylum after “removed from streets” | BPRS (Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale) (S) | 57.1% drop in BPRS symptoms in the Flupenthixol group (p < 0.001) and 43.4% drop in the Clopenthixol group (p < 0.01). Flupenthixol group had better symptom reducation respsone than the Clopenthixol group (p < 0.01) | Medium |

| Balogun and Olawoye 2013 [40] | Cross-sectional | Prison | Nigeria | Y (within institution comparison of high/low self-esteem and high/low emotional intelligence) | NS | No, No | 233, 31.3, 86.27% (total participants) | NA | NS | SDS Self-Rating Depression Scale (S), TMMS Trait Meta-Mood Scale (S), Rosenberg self-esteem scale (S) | Both emotional intelligence (p < 0.05) and self-esteem (p < 0.05) had a significant influence on depression | Low |

| Idemudia 1998 [131] | Cross-sectional | Prison | Nigeria | N | Random, NS | No, No | 150, 27.8, 61.3% | NA | NS | API (S), MSQ/CCEI (S) | Long-term detained persons had higher mean scores of psychopathy symptoms (API), (p < 0.001), and neurotic symptoms (MSQ/CCEI), (p < 0.001), than those serving medium and short terms | Medium |

| Idemudia 2007 [132] | Cross-sectional | Prison | Nigeria | Y (college students, matched for gender, youth characteristic, and age*) *However, we note that statistics show that college students have noticeably older mean age |

Random, NS | No, No | 100, 17.2, 83% (detained participants); 100, 25.2, 81% (college students) | Homeless on street before prison | NS | PDS (S), MAACL-H (S) | Higher scores on the Psychopathic Deviate Scale (p < .05) and the Multiple Affect Adjective Checklist hostility subscale (p < .0001) among the imprisoned homeless group than the non-prison and never homeless group | Medium |

| Ineme and Osinowo 2016 [133] | Cross-sectional | Prison | Nigeria | N | Random, NS | Yes, Yes | 212, 34.4, 86.3% | NA | NS | HADS (S), IS-HUS (S), questionnaire (S) | Participants who used psychoactive substances (questionnaire) before detention reported higher self-harm urges (IS-HUS) than those who did not use (p < .01). Participants with higher depressive symptoms (HADS) reported higher self-harm urges than those with low depressive symptoms (p < .01}. Significant interaction of prior substance use and depression (< .01) | Low |

| Stephens et al. 2006 [38] | Cross-sectional | Prison | South Africa | N | Census | Yes, Yes | 357, NS, 100%* | Males; pre-release; scheduled to be released from prison within three months after receiving intervention in parent study | U *all participants have pre-release status | Questionnaire (S) | Participants who used psychoactive substances (questionnaire) before detention reported higher self-harm urges (IS-HUS) than those who did not use (p < .01). Participants with higher depressive symptoms (HADS) reported higher self-harm urges than those with low depressive symptoms (p < .01}. Significant interaction of prior substance use and depression (< .01) | Medium |

| Weierstall et al. 2011 [37] | Cross-sectional | Prison | Rwanda | N | Random, NS | Yes, Yes | 269, 33, 66% | Perpetrators of the Rwandan genocide | C *82% convicted, 18% awaiting trial | PTSD Symptom Scale-Interview (PSS-I) (D), PDS Event Scale (S), Appetitive Aggression Scale (AAS) (S) | Dose–response effect via path analysis between the exposure to traumatic events and the PTSD symptom severity (p < .001). Participants who had reported that they committed more types of crimes demonstrated a higher AAS score (p < .01), and higher AAS scores predicted lower PTSD symptom severity scores (p < .05). | Low |

| Odejide 1979 [134] | Cross-sectional | Forensic ward | Nigeria | N | Census | No, No | 2158, NS, 95.9% | Psychiatric referrals | U *Referrals to hospital | Court records (NA) | 32.4% of 81 individuals with murder charges were referred for psychiatric opinion. No individuals with charges in categories of crime, including three individuals with charges of attempted suicide, was sent for psychiatric examination. Absence of mental illness in 66.6% of subjects referred for psychiatric opinion | Low |

| Sukeri et al. 2016 [135] | Cross-sectional | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | No, No | NA | NA | NA | Questionnaire (S) | No nurses with advanced training in forensic psychiatry. Lack of sufficient human resources. The nurse/patient ratio was 1:4. For 403 patients, 1.6 psychiatrists (1 full time),1 social worker, 1 occupational therapist, 0 occupational therapist assistants. There are 22 psychologists in all correctional centers in South Africa. None of the correctional centers have an onsite psychiatric unit | Low |

| Ononye and Morakinyo 1994 [39] | Cross-sectional | Youth Institution | Nigeria | Y (50 school going children, matched for sex, age, ethnicity and educational level) | Census | No, No | 50, 14.1, 86% (youth in remand home); 50, 14.1, 86% (school-going youth) | NA | NS *Remanded youth | Carlson Psychological Survey (CPS) (S) | Thought disturbance significantly higher in youth in remand home compared to school-going youth. Antisocial tendency and self-depreciation higher among youth in remand home but not significantly. Substance abuse not significantly different between groups. (all indicated by CPS) | Medium |

| Large and Nielssen 2009 [41] | Cross-sectional | Health system | International | Y (LMIC and HIC countries) | Census | No, No | NA | NA | NS | Published records in the literature (NA) | Correlation between per capita psychiatric hospital beds and prisoner numbers in the 158 countries (p < 0.01) and the subgroup of 120 LAMI countries (p < 0.01). No significant correlation within the 38 HI countries | Low |

| Gaum et al. 2006 [45] | Qualitative | Prison | South Africa | N | Convenience, N | No, Yes | 10, 37.6, 50% (interviews); 18, NS, 100% (in focus groups) | Recidivists; psychological services clients | C | Interviews and focus groups | Interviews reveal a shortage of medical personnel in the prison psychiatry/psychology service. Also suggested from interviews: overpopulation in prisons may be due to rapid and dramatic political and economic changes in South Africa, coupled with the belief that crime pays and that being in prison is preferable to being jobless and homeless outside | Low |

| Pretorius and Bester 2009 [47] | Qualitative | Prison | South Africa | N | Purposive, N | Yes, Yes | 3, 35–42, 0% | Women convicted of homicide of their intimate partner | C | Interview | All three participants’ interviews were indicative of PTSD and substance misuse | Low |

| Topp et al. 2016 [46] | Qualitative | Prison | Zambia | N | Purposive and Random, N | Yes, Yes | 79, 35.6, 100%* (detained); 32, NS, 50% (prison staff) | Detained men | C *70–100% convicted depending on facility | Interviews and focus groups | A majority of participants in prison, as well as facility-based officers reported anxiety linked to over-crowding, sanitation, infectious disease transmission, nutrition and coercion. Interviewees associated overcrowding with negative effects on both participants in prison and officers’ physical and mental health. Limited access to healthcare | Low |

| Kaliski et al. 1997 [48] | Qualitative | Forensic ward | South Africa | N | Census | No, Yes | 88, 30.4, 100% | Defendants undergoing psychiatric referral | NC *Pre-trial defendants for psychiatric observation | Psychiatric record (D) | 30.7% ultimately declared mentally ill. Only 25% knew that they were to be psychiatrically examined during the 30-day period. 44.3% did not know what was to happen to them after the completion of the observation period | Low |

| Dube-Mawerewere 2015 [49] | Structured health system review | Health system | Zimbabwe | N | Purposive, N | No, No | 32, NA, NA | Forensic psychiatry system stakeholders | NS | Interview | Special psychiatric institutions housed within prisons, resulting in prison-like living conditions. Lack of staff in special institutions and forensic psychiatry settings with psychiatric training. Revolving door between civil psychiatric institutions in the prison, forensic hospital, and prison | Not assessed due to study design |

| Kidia, et al. 2017 [22] | Structured health system review | Health system | Zimbabwe | N | Purposive, N | No, No | 30, NA, NA | Mental health system stakeholders, excluding patients | NA | Interviews, Emerald national-level needs assessment methods | Forensic facilities were substantially under-resourced, especially shortages of psychotropic medicines and human resources. Patients lived in overcrowded holding cells with unhygienic living conditions, with high prevalence of sexual assault and HIV transmission, minimal access to psychotropic medications and psychiatric care, and little food | Not assessed due to study design |

| Liddicoat et al. 1972 [136] | Tool validation | Prison | South Africa | Y (99 participants with psychopathy diagnosis and 99 without psychopathy diagnosis matched for age and IQ) | Purposive, NS | No, No | 198, NS, 100% (total participants, pooled) | Participants with and without psychopathy diagnosis | C | Questionnaire (S) | 64/150 items on the questionnaire discriminated significantly between participants with and without psychopathy diagnosis | Not assessed due to study design |

| Prinsloo and Ladikos 2007 [137] | Tool validation | Prison | South Africa | Y (231 those with offense designated “high-risk” compared to 38 segregated due to history of maladjustment, disciplinary problems and other institutional infractions) | Purposive, NS | No, Yes | 269, 31.8, 100%* (total participants, pooled) | Men with offense; those designated “high-risk” | NS | SAQ (S) | The overall alpha score of the SAQ, inclusive of all the interactive subscales, is (.904) | Not assessed due to study design |

| Prinsloo 2013 [138] | Tool validation | Prison | South Africa | N | NS | No, Yes | 236, 34, 100% | NA | C | Psychiatric record (D), SAQ (S) | Logistic regression model of the behavioral characteristics assessed with the Self-Appraisal Questionnaire (SAQ) shows that modeling the behavioral characteristics accounts for 61% of the variation in the dependent variable mental illness. Subscales of anger, criminal tendencies and anti-social personality have significantly higher (p < 0.05) mean scores for mentally ill respondents | Not assessed due to study design |

| Bunnting et al. 1996 [139] | Tool validation | Forensic ward | South Africa | Y (50 patients designated “malingering” and 50 state patients with mental disorder or sick (State President’s Detainees) | Purposive, N | No, No | 100, NS, NS (total participants, pooled) | Psychiatric referrals and state patients | NS *Pre-trial, convicted, and referrals | Questionnaire (S) | 17/20 items on the questionnaire statistically significant based on the study sample | Not assessed due to study design |

Data analysis

Because of the heterogeneity of the study designs and outcomes, we conducted narrative analysis, as an overall meta-analysis was not possible. To facilitate comparison between like studies, we structured our presentation of results by study design.

Meta-analysis

The large number of prevalence studies enabled us to conduct a meta-analysis of the prevalence of mental disorders. Notably, this analysis was added post hoc, as we did not anticipate sufficient study design homogeneity for meta-analysis at the outset of the study. We generated pooled prevalence estimates with 95% confidence intervals [32] for key disease categories: mental ill health (including measures of psychological distress or an unspecified mental disorder, often assessed using a screening tool, such as the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) [33], but excluding results of disorder-specific instruments), mood disorders, psychotic disorders, and substance use. Heterogeneity between studies within each category was assessed using Chi squared and I2 (> 50% is considered heterogeneous [34]). A random effects model was used to estimate the pooled prevalence, as all groups demonstrated significant heterogeneity. The random effects model weights included studies to account for both sample size and between-study variance with the between-study variance term dominating the weighting when studies are heterogeneous [35], as it assumes that studies come from different distributions. In order to identify sources of heterogeneity, we conducted subgroup analysis, grouping according to youth and adults; then, within studies of adults, location (prison or forensic ward) and data collection method (instrument or clinical record). In the subgroup analysis, we determined the pooled prevalence for each subgroup and its heterogeneity. Statistical analysis was done using STATA/SE 15.0 [36]. Additional details of the data extraction and statistical analysis are shown in Additional file 1: Appendices S4, S6 and S7.

Results

Search results

After removing duplicates, our search yielded 1240 results in the initial database search, of which 73 met inclusion criteria. We excluded three studies based on the methods screen results and added eight from a backward search. We were not able to access the texts or abstracts of three studies from the backward search title results because they were not available for loan from multiple university library systems. A third researcher (HJ) reviewed 39 full texts about which the other two reviewers could not reach agreement and chose to include 12 of them (31%). We added two articles identified through expert consultation. This yielded 80 papers for data extraction (Fig. 1), including 17 papers that were written on the same sample and as part of the same study as another paper in our dataset, but with different methods details or outcomes reported. In this review, the terms “independent studies” or “samples” refer to the number of independent studies, and the term “papers” refers to all papers in the dataset. There were 70 independent studies in our data. All papers are described in Tables 2 and 3.

Study characteristics

Prevalence was the dominant study type (67%), with small numbers of other study types including ten non-prevalence cross-sectional studies, four qualitative studies, four tool validations, two structured health systems reviews, two pre-post studies, and one randomized control trial. The majority of studies took place in either Nigeria (30; 43%) or South Africa (21; 30%). Only five of 23 non-prevalence studies took place outside of Nigeria or South Africa: two health systems studies in Zimbabwe, one qualitative study in Zambia, one cross-sectional study in Rwanda, and one international comparative study. Sixty-nine percent of studies collected primary data, or data resulting from diagnostic or screening tools, and 37% collected secondary data, defined as data extracted from available records. Four studies collected both primary and secondary data. Thirty-two studies (46%) examined prison settings, of which all but one study collected primary data. Twenty-six studies (37%) examined forensic hospital settings (included only if they were settings in which a justice-involved population was detained). Among these, 88% were based on secondary data, and the majority took place in either South Africa (54%), Nigeria (15%), or Zimbabwe (12%). Nine studies (13%) examined youth institutions, of which all were conducted in Nigeria. Three studies (4%), two conducted in Zimbabwe and one international, examined the mental health system.

Risk of bias

Most of the papers assessed fell into the low (36; 49%) or medium (33; 45%) methods risk of bias categories. A number of medium risk papers were given this judgement based on lack of detail in methods reporting, meaning that it was unclear if the studies had high risk of bias or if methods were not reported well. About half of the medium risk papers reported diagnoses from secondary psychiatric records (17), for which it was often unclear how the diagnoses were made, who made them, or if they were based on standard criteria, such as the ICD. Of the 57 psychiatric prevalence papers, 44% (25) fell into low risk, 47% (27) fell into medium, and 9% (5) fell into high risk of bias categories. All “high risk” studies were prevalence papers. See Additional file 1: Appendix S5 for results of the methodologic review of prevalence studies, which includes evaluation of sampling technique using the Prevalence Critical Appraisal Checklist.

Data collection method

Most studies used a census sampling strategy (42; 60%), followed by random (18; 26%), purposive (8; 11%), not stated (4; 5.7%), mixed sampling (3; 4.3%), and convenience sampling (1, 1.4%). Of all psychiatric prevalence papers, 60% used validated instruments for primary data collection, while the rest extracted data from secondary psychiatric records.

Participants

In 69% of samples, more than 85% of participants were male. In 10 samples, “male” was an inclusion criterion. The mean age of participants among samples listing mean age was 28.8, and there was a broad distribution of sample size, from 18% of participant samples with 50 people or less (including all three interventions), to 13% with over 400 participants. In 36% of samples, the majority of participants had not been convicted of any crime (the majority of participants were either awaiting trial or detained without trial). In another 41% of samples, trial status was not stated or unclear, or participants were justice-involved youth (in which trial status was ambiguous). In only 20% of samples, the majority of participants had been convicted.

Ethics characteristics

Of all papers, 35% neither documented ethics committee approval nor described an informed consent procedure, and 41% described both. Ten percent reported ethics committee approval but not informed consent, and 14% reported informed consent but not ethics committee approval.

Outcomes

To facilitate comparison between like outcomes, we have presented study outcomes by study design: prevalence, non-prevalence cross-sectional, intervention testing, qualitative, structured health system review, and tool validation. Of the 57 prevalence papers reporting mental health diagnoses or screening results, 44 (77%) reported diagnoses of psychiatric conditions, of which 14 papers also used instruments designed to screen for psychiatric morbidity but not diagnose. Thirteen papers (23%) reported outcomes obtained with screening tools alone, not diagnostic instruments. Reported factors associated with a psychiatric outcome and secondary outcomes are displayed in Additional file 1: Appendices S10 and S11.

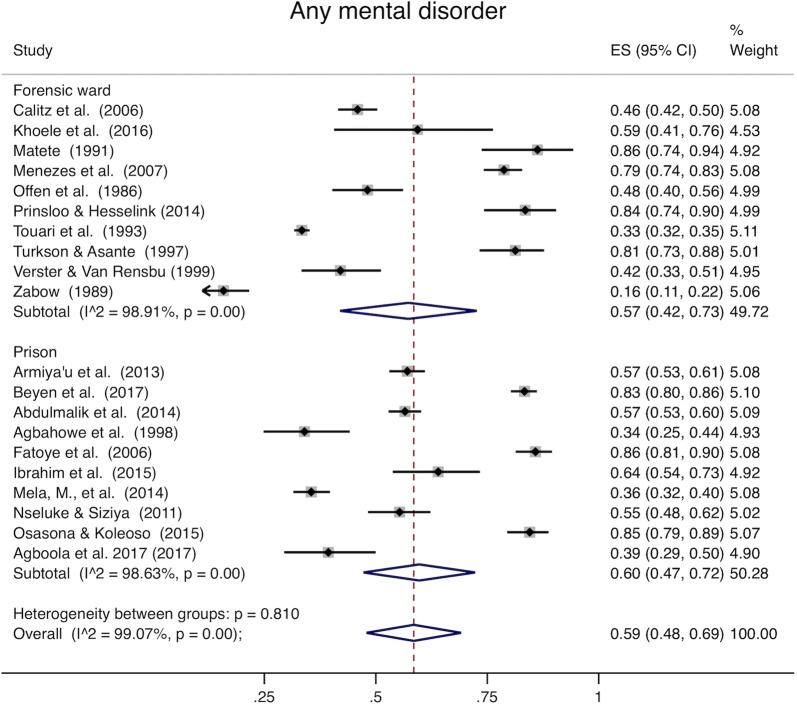

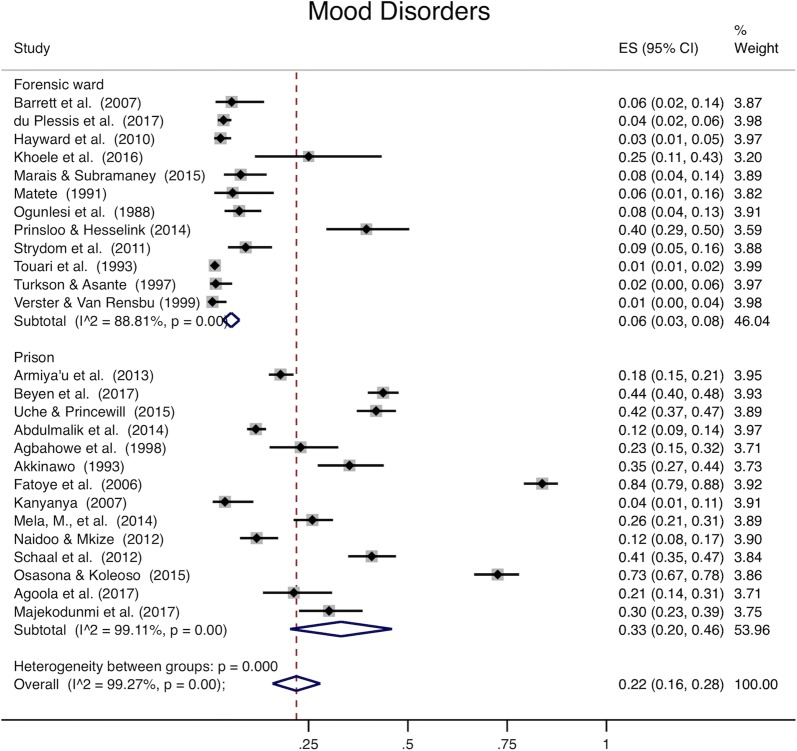

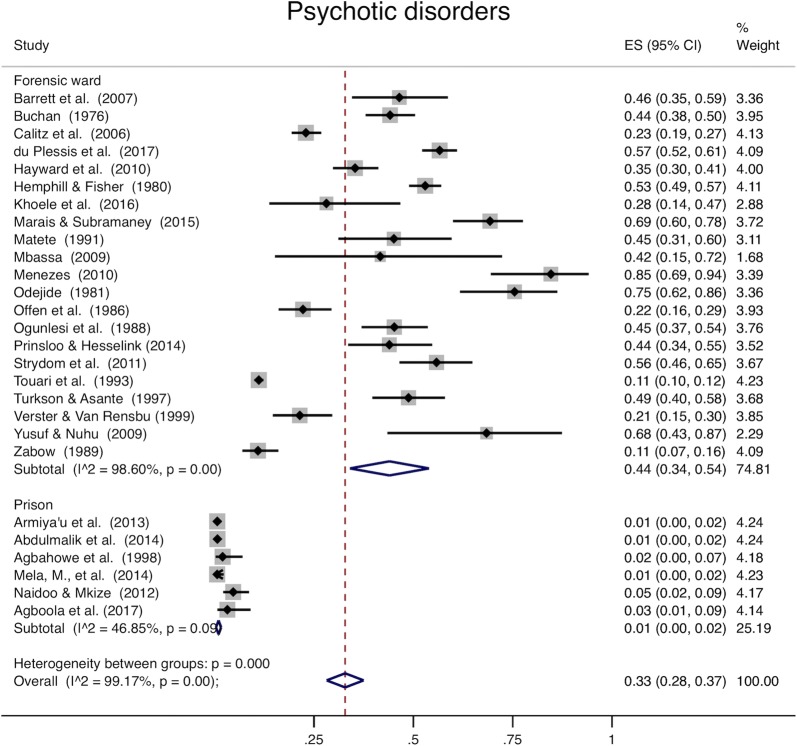

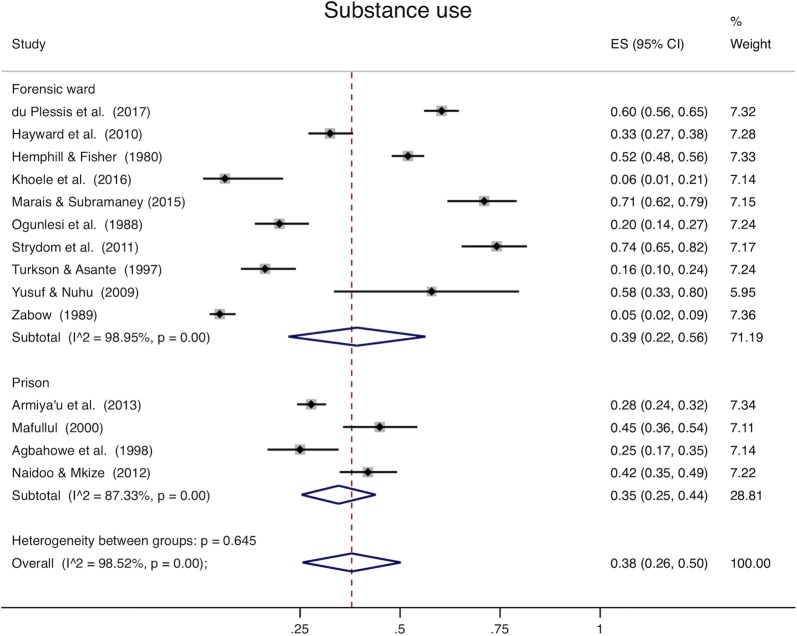

Prevalence studies

Analysis of all studies combined (Table 4) was heterogeneous (I2 > 98% for all disease categories). When youth and adults were examined separately, pooled prevalence among adults was 59% for mental ill health (95% CI 48–69%, Fig. 2), 22% for mood disorders (95% CI 16–28%, Fig. 3), 33% for psychotic disorders (95% CI 28–37%, Fig. 4), and 38% for substance use (95% CI 26–50%, Fig. 5). Among youth (Table 5), prevalence of mental ill health was 61% (95% CI 17–100%), mood disorder was 24% (95% CI 14–25%), and substance use was 22% (95% CI 8–36%). Heterogeneity analysis revealed statistically significant heterogeneity for all disease categories and subgroup by institution (Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5) (I2 > 50%). The one exception was psychotic disorders in prisons, which because of their very low prevalence, were less heterogeneous (I2 = 46.85%). The prevalence of psychotic disorders among inpatients in forensic wards was 44% (95% CI 34–54%), while in prisons the prevalence was 1% (95% CI 0–2%). Subgroup analysis by data collection method (clinical record or diagnostic/screening instrument) was not presented separately; all of the studies conducted in prisons use instruments to collect data, and all but one of those conducted in forensic institutions use clinical records. Thus, there is so much confounding that we cannot meaningfully separate the effects of data collection method from institution type. Robustness analysis (Additional file 1: Appendix S6) showed that the point prevalence estimates were similar regardless of how the subgrouping was done. Additionally, to examine if there was heterogeneity based on sampling technique, we conducted a sensitivity analysis including studies using census sampling only (the most homogenous sampling technique; randomization can vary substantially based on the method used to randomize, and the randomization method was not stated in most included studies) (Additional file 1: Appendix S7). Prevalence estimates of this subgrouping had as much heterogeneity as estimates from pooling different sampling methods (census, random, not stated) and were similar to overall estimates.

Table 4.

Overall prevalence of mental disorders

| Mental ill health | Mood disorder | Substance use | Psychotic disorders | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled prevalence (95% CI) | 0.59 (0.49–0.69) | 0.22 (0.16–0.28) | 0.34 (0.24–0.44) | 0.32 (0.27–0.36) |

| Heterogeneity chi2 | 2513.79 (p<0.001) | 3447.07 (p<0.001) | 1025.05 (p<0.001) | 3133.52 (p<0.001) |

| I2 | 99.09% | 99.19% | 98.24% | 99.14% |

| Number of studies | 24 | 29 | 19 | 28 |

Fig. 2.

Mental ill health. The x-axis in each plot displays prevalence (0–1). The far right column displays the prevalence within each study, pooled prevalence for each subgroup, and overall pooled prevalence with their respective weights. Armiya’u et al. [86] and Armiya’u et al. [87] describe the same study and sample and report the same prevalence. Only one point prevalence from this sample was included from these articles in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5

Fig. 3.

Mood disorders. The x-axis in each plot displays prevalence (0–1). The far right column displays the prevalence within each study, pooled prevalence for each subgroup, and overall pooled prevalence with their respective weights. Uche and Princewell “Prevalence…” (2015) [103] and Uche and Princewell “Clinical factors…” (2015) [102] describe the same study and sample and report the same prevalence. Only one point prevalence from this sample was included from these articles

Fig. 4.

Psychotic disorders. The x-axis in each plot displays prevalence (0–1). The far right column displays the prevalence within each study, pooled prevalence for each subgroup, and overall pooled prevalence with their respective weights

Fig. 5.

Substance use. The x-axis in each plot displays prevalence (0–1). The far right column displays the prevalence within each study, pooled prevalence for each subgroup, and overall pooled prevalence with their respective weights

Table 5.

Prevalence of mental disorders among youth

| Mental ill health | Mood disorder | Substance use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled prevalence (95% CI) | 0.61 (0.17–1.00*) | 0.24 (0.14–0.35) | 0.22 (0.08–0.36) |

| Heterogeneity chi2 | 422.59 (p<0.001) | 4.93 (p=0.08) | 95.75 (p<0.001) |

| I2 | 99.29% | 59.46% | 95.82% |

| Number of studies | 4 | 3 | 5 |

Psychotic disorders were not included in this table, as only one youth study measured this outcome (Atilola 2012 “Prevalence and correlates…” [6])

*For clarity, this confidence interval is truncated at 1.00 as its upper bound

Cross-sectional studies

Nine cross-sectional studies did not collect psychiatric prevalence data, but investigated variables associated with mental health conditions, or justice or health system qualities. These studies examined associations between mental health-related variables (for instance, PTSD symptom severity [37]; substance misuse [38, 39]) and other factors (crimes committed [37]; prevalence of sexually transmitted infections [38]; emotional intelligence [40]). Alternatively, large and Nielssen found a positive correlation between per capita prison populations and per capita psychiatric hospital beds among LMICs and a combined pool of 158 countries, but no significant correlation among high-income countries [41].

Interventions

The intervention studies included two pre-post group-focused cognitive behavioral interventions in prisons, one for cigarette smoking dependence and one for depression, both yielding significant improvements in the treatment group compared to the control group (p < 0.001) [42, 43]. The single randomized control trial demonstrated significant decreases in schizophrenia symptoms following injections of two different neuroleptics in separate treatment arms (each neuroleptic treatment group resulted in a p < 0.01 decrease in the combined schizophrenia symptom score compared to the pre-injection score, and the Flupenthixol group showed a larger decrease than the Clopnethixol group (p < 0.01)) [44]. Additional details of the intervention studies are listed in Additional file 1: Appendix S8.

Qualitative studies

The outcomes of the four qualitative studies included a shortage of medical personnel in prison mental health services in South Africa [45], poor prison conditions linked to mental health problems in a Zambian prison [46], psychiatric findings among women in prison for homicide [47], and gaps in awareness of the legal process and other legal characteristics of participants referred for psychiatric observation [48].

Structured health systems reviews

The two structured health systems reviews, both in Zimbabwe, each interviewed around 30 participants. One used an exploratory qualitative design, including interviews with people detained in the justice system, and proposed a model for transforming the medico-judicial system that involves multiple stages of mental health screening and diversion from the justice system [49]. The other used a structured needs assessment and interviews with policy makers, administrators, providers, and researchers to examine the national mental health system and found that many stakeholders called attention to the forensic mental health system although the researchers did not specifically ask about forensic mental health [22].

Descriptions of conditions of detention, policy, law, and health systems

We collected descriptions of mental health policy, laws, and systems if systematically collected and reported in any study type. Thirteen papers described conditions of detention in institutions, laws, or policy, including eight prevalence studies, three qualitative studies, and two structured health systems reviews. While it was not always clear whether the methodology used to report such outcomes was rigorous, we collected this data because of the scarcity of existing literature on this topic and report common findings thematically in Additional file 1: Appendix S9. The most common findings were insufficient human resources for health; lack of psychosocial services; lack of timely psychiatric assessment; and limited rehabilitation, recreational, vocational, or community re-integration services. Other common themes included insufficient physical resources, food, or psychiatric medicines; delays in trials, case-processing, or release; and lack of communication between medical and justice systems.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to investigate the mental health of PDJS in Africa exclusively. Results reflect that existing studies on this topic are predominantly prevalence studies that show a high pooled prevalence of mental illness, consistent with previous findings on mental illness in detained populations globally. Notably, many people detained within the justice system in non-prison locations, such as youth institutions or forensic hospitals, were detained with no charge [6, 7, 50–55]. The neglect of these populations in the literature is especially alarming in the context of pressures to deinstitutionalize mental healthcare in LMICs [15, 56–59].

A number of key populations were missing from our results. There were very few women included in the included studies, reflective of the small proportion of women found in prisons worldwide, particularly Africa, where only 3% of the total prison population are female, much lower than elsewhere [60]. Reasons for this may be that worldwide, likely due to distinct social roles, women commit fewer crimes [61] and that women are less likely to be convicted of crimes and sent to prison by courts [62]. The studies were also concentrated in a small number of African countries (73% of studies were in South Africa or Nigeria), and we found no studies in 36 of the 47 WHO-defined African countries. While more research is needed on translations of interventions across low-resource settings, we urgently need ground-work research in local contexts. Surprisingly, the general population detained in prisons was poorly represented in our sample, as prison studies were concentrated around people with particular psychiatric or forensic variables such as type of crime or trial status.

Our meta-analysis of prevalence studies revealed high pooled prevalence of mental disorders and substance use among PDJS in Africa, which underscores the urgency of addressing the mental health of detained people in Africa within the global mental health movement. However, the studies were heterogeneous. While we attempted to explore and explain the heterogeneity using subgroup analysis, nearly all subgroups were also heterogeneous. The most valid finding of the meta-analysis is that we have statistically shown that the studies were conducted on distinct populations. This is not surprising given that the populations are from across Africa and are detained in a variety of different types of institutions and under distinct penal policies. Accordingly, it is important to interpret the meta-analysis findings cautiously as the heterogeneity may limit the validity of providing a single point estimate for distinct populations. Notably, the level of heterogeneity we found was consistent with prior systematic reviews on the prevalence of mental disorders in prison settings [2]. All of this underscores the need for more research on mental health in prison settings and better standardization of the tools used to assess mental and substance use disorders.