Abstract

Fitness interactions between mutations can influence a population’s evolution in many different ways. While epistatic effects are difficult to measure precisely, important information is captured by the mean and variance of log fitnesses for individuals carrying different numbers of mutations. We derive predictions for these quantities from a class of simple fitness landscapes, based on models of optimizing selection on quantitative traits. We also explore extensions to the models, including modular pleiotropy, variable effect sizes, mutational bias and maladaptation of the wild type. We illustrate our approach by reanalysing a large dataset of mutant effects in a yeast snoRNA (small nucleolar RNA). Though characterized by some large epistatic effects, these data give a good overall fit to the non-epistatic null model, suggesting that epistasis might have limited influence on the evolutionary dynamics in this system. We also show how the amount of epistasis depends on both the underlying fitness landscape and the distribution of mutations, and so is expected to vary in consistent ways between new mutations, standing variation and fixed mutations.

Keywords: fitness landscapes, genetic interactions, Fisher’s geometric model, Saccharomyces cerevisiae

1. Introduction

Fitness epistasis occurs when allelic variation at one locus affects allelic fitness differences at other loci. Epistatic interactions can be used to uncover functional interactions [1], but for other questions, the most important quantity is the complete distribution of epistatic effects. The shape of this distribution can affect a population’s ability to adapt, its genetic load, the outcomes of hybridization, and the evolution of recombination rate or investment in sexual reproduction [2–13].

To investigate such questions, most research has focused on the mean level of epistasis. This can be estimated from the rate at which mean log fitness declines with the number of mutations carried [7,14–17], which is simple to model [2,4,9,18,19]. But variation around this mean can also affect the evolutionary dynamics [6,7,17].

To understand the complete distribution of effects, one approach is to use Fisher’s geometric model [20], a simple model of optimizing selection on quantitative traits [10,12,21,22]. This is a toy model, but it approximates a broad class of systems biology models, involving metabolic networks [21]. Furthermore, it naturally generates fitness epistasis; and the overall level of epistasis can be ‘tuned’ by adjusting the curvature of the fitness function, that is, the rate at which fitness declines with distance from the optimum [10–12,23–28].

Because it generates a rich spectrum of effects with few parameters, Fisher’s geometric model is particularly suitable for data analysis [24,29–31], including data on fitness epistasis [32–36]. Perhaps most impressively, Martin et al. [32] used the model to successfully predict several properties of the distribution of epistatic effects in the microbes Escherichia coli and vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) [15,37]. However, these authors did not directly study the effects of varying the curvature of the fitness landscape, nor other possible variants of the model [25,38–41]. Here, following [32], we study properties of fitness epistasis under Fisher’s geometric model. We extend previous results by examining a wider class of fitness landscapes and also compare the predictions with a recent, large-scale dataset of yeast mutants [1].

2. Models and analysis

(i). Basic notation and a null model without epistasis

Let us denote as ln wd, the log relative fitness of an individual carrying d mutations. Across many individuals, its scaled mean and variance are

| 1 |

| 2 |

where, by definition, m(0) = v(0) = 0 and m(1) = v(1) = 1. These equations use a log scale, because deviations from additivity on a log scale influence the evolutionary dynamics [7].

We can immediately give results for a null model with no epistatic effects. In this case, mutations will contribute identically to the mean and variance in fitness, regardless of how many other mutations are carried. So, a collection of individuals carrying two random mutations is expected to have twice the decline in log fitness, and twice the variance in log fitness, compared with a collection of individuals carrying one mutation. This implies that

| 3 |

| 4 |

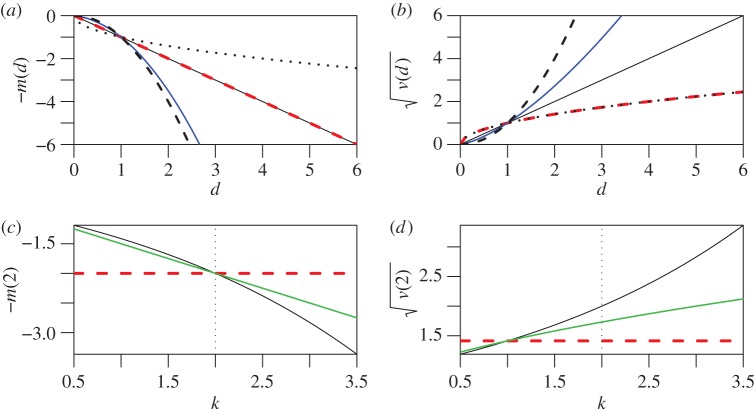

where the subscript 0 indicates the non-epistatic null model. These predictions are illustrated by red dashed lines in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Predictions for mean log fitness (a,c) or the standard deviation in log fitness (b,d). (a,b) show predictions for individuals carrying different numbers of mutations, d. (c,d) shows results for double mutants (d = 2), varying the curvature of the fitness landscape, k. Results for the null model, with no epistasis, are shown as red dashed lines. In this case, the mean and variance in log fitness both change linearly with d (equations (3) and (4)). Results for simple phenotypic models are shown as black lines. The upper panels show results with no epistasis on average (solid lines, k = 2), negative epistasis on average (dashed lines, k = 4) or positive epistasis on average (dotted lines, k = 1). Blue lines show results for a model with strongly biased mutations (β = 3, k = 2; electronic supplementary material, equations (48) and (50)). Green lines show results where the mutations on each trait are drawn from a leptokurtic reflected exponential distribution (electronic supplementary material, equation (43)). (Online version in colour.)

To measure epistasis directly, we could measure the pairwise interaction between two mutations, denoted ‘a’ and ‘b’:

| 5 |

Here, w(a) denotes the relative fitness of the genome carrying the mutation ‘a’ and so on. Though widely used, ɛ can be difficult to work with. For example, if the same mutation appears in multiple double mutants, then the complete distribution of ɛ will entail using the same fitness measurements multiple times, creating complications from pseudoreplication or correlated errors. Furthermore, for a complete picture of epistasis, we would also have to consider higher-order interactions between three or four mutations. For these reasons, we focus on equations (1) and (2), and give some equivalent results for ɛ in electronic supplementary material, appendix A. The quantities are also closely related. For example, equation (3) implies that there is no epistasis on average (i.e. that positive effects exactly match negative effects, such that E(ɛ) = 0), while equation (4) implies that all epistatic effects are the same, such that Var(ɛ) = 0 (see electronic supplementary material, appendix A). Together, then, equations (3) and (4) imply that there is no epistasis at all.

(ii). Additive phenotypic models

Under Fisher’s geometric model, an individual’s fitness depends on its values of n quantitative traits: z = {z1, z2, …, zn}. Fitness depends on the deviation of the phenotype from a single optimal value. A suitable fitness function of this kind is

| 6 |

where [25,26]. An alternative, which does not assume identical selection on all traits, is

| 7 |

where λi determines the strength of selection on trait i [23,24]. These two fitness functions often give similar results (electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2), but they are identical only when k = 2 and all λi are equal.

The simplest models then further assume (1) that the wild type is phenotypically optimal; (2) that mutations are additive with respect to the phenotype; and (3) that the mutant effects on each trait are drawn, independently, from a standard normal distribution.

In electronic supplementary material, appendix A, we show that these assumptions yield the following results, as illustrated by the black lines in figure 1:

| 8 |

| 9 |

Equations (8) and (9) show how k affects the level of fitness epistasis [23,26]. When k = 2, we have no epistasis on average, as with equation (3) (solid black lines in figure 1a,b). Setting k > 2 leads to negative epistasis on average (dashed black lines in figure 1a,b), and k < 2 leads to positive epistasis on average (dotted black lines in figure 1a,b). Note also that equation (9) will never agree with equation (4), because these simple phenotypic models always generate fitness epistasis.

Confronted with data from real quantitative traits [42], many aspects of the models above appear grossly unrealistic. In electronic supplementary material, appendix A, we explore several variants of the model, designed to relax its simplifying assumptions. We show that altering the distribution of single mutation effects can have a major effect on results, greatly altering the relationship between m(d) and k. However, in each case, we also show that this leaves a signature in the variance, such that

| 10 |

This is illustrated by the blue and green lines in figure 1.

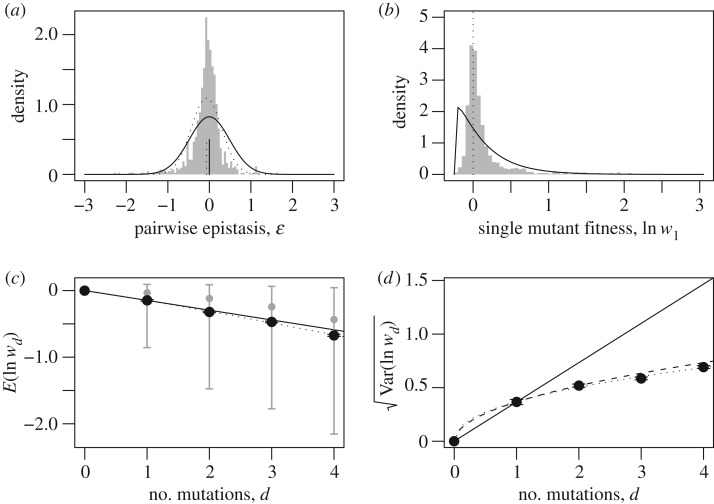

3. Reanalysis of data from a yeast snoRNA

To illustrate the above approach and compare different measures of epistasis, we now reanalyse the data of Puchta et al. [1], who used saturation mutagenesis of the U3 snoRNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (see electronic supplementary material, appendix B for full details). Figure 2a confirms that pairwise epistatic interactions are present in these data [1]. Nevertheless, figure 2c,d shows that, considered as a whole, the data give a very good fit to the non-epistatic null model (equations (3) and (4)).

Figure 2.

Reanalysis of mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae U3 snoRNA (small nucleolar RNA) [1]. (a) Distribution of pairwise epistatic effects (equation (5)), compared with the predictions of the simplest phenotypic model with k = 2: ɛ ∼ N(0, 2Var(ln w1)) (black line; [32]; electronic supplementary material, appendix A), and a normal distribution with matching mean and variance (dotted line). (b) Distribution of single-mutant log fitnesses, and the best-fit shifted gamma distribution, as predicted by the simplest phenotypic models [29]. (c) Mean of the log fitnesses of individuals carrying d mutations (black points with barely visible standard error bars); the median and 90% quantiles (grey points and bars); the analytical prediction, which applies to both the null model and the phenotypic model with k = 2 (solid line; equations (3) and (8)); and the best-fit regression for ln m(d) ∼ ln d (dotted line, which has a slope implying ). (d) Standard deviation in the log fitnesses of individuals carrying d mutations (black points with barely visible standard error bars); analytical predictions from the null model, equation (4) (dashed line), or the phenotypic model with k = 2, equation (9) (solid line); and the best-fit regression of ln v(d) ∼ ln d (dotted line, which has slope 0.89).

Some of this apparent discrepancy can be attributed to the greater robustness of our statistics to measurement error. For example, we show in electronic supplementary material, figures S4 and S5 that the inferred variance in epistatic effects decreases with the amount of replication, while patterns in m(d) and v(d) are little changed. Furthermore, some reduction in epistasis could have been predicted from other aspects of the data, which violate the assumptions behind equations (8) and (9) (see supplementary material, appendices for full details). For example, the distribution of single-mutant fitnesses (figure 2b) is inconsistent with the assumption of normal effects, and the presence of beneficial mutations (346/965 mutations increase growth rate) is inconsistent with the assumption of an optimal wild type. Nevertheless, we argue in electronic supplementary material, appendix A that the phenotypic models—even in modified form—overestimate the true amount of fitness epistasis in these data. This implies that simple models of independent effects might be sufficient to understand several aspects of the evolutionary dynamics in this system, despite the clear presence of some fitness interactions [1].

4. Discussion

We have used simple summary statistics to describe levels of fitness epistasis. These statistics are relevant to evolutionary questions [7], and are less sensitive to measurement error than are estimates of individual epistatic effects.

We then developed analytical predictions for these statistics under simple models of quantitative traits selected towards a single optimum. The simplest such model assumes that mutant effects on each trait are independent and identically distributed normal, and considered as a model of quantitative traits, this seems unrealistic [39,42–44]. Nevertheless, considered as a fitness landscape, the same model has been shown to give a good fit to fitness data from E. coli and VSV [15,32,37]. Our results go further and show that only this simple model would have fitted those data; increasing the realism of the quantitative traits (e.g. by introducing leptokurtic effects), would have underpredicted the amount of epistasis. This reinforces the argument of [21] that the ‘traits’ in Fisher’s geometric model, when considered as a fitness landscape, should not be equated with standard quantitative traits. On a related point, the good fit to the fitness data was obtained by assuming that k = 2 [15], and we have shown that no other value of k could have given a comparable fit. This has implications for the evolution of epistasis, because multiple authors have shown that models with no epistasis on average (i.e. with k = 2) are vulnerable to invasion by modifiers [26,45,46]. As such, the good fit of k = 2 implies that global modifiers of fitness epistasis do not arise in these systems.

Of course, we cannot assume that identical patterns of epistasis will characterize all datasets [47,48], and we have offered two further reasons to doubt this. First, empirically, we have shown that the data of Puchta et al. [1] give a good overall fit to a non-epistatic null model, despite the likely presence of some fitness interactions ([1]; figure 2). Second, theoretically, we have shown how the observed level of epistasis will depend on both the underlying fitness landscape and the distribution of mutation effects. For example, a landscape with a high level of curvature (i.e. k > 2) might still generate a linear decline in mean log fitness (such that m(d) ≈ d) if the distribution of mutant effect sizes is highly leptokurtic (see electronic supplementary material, appendix A); but, this effect should be evident in the reduced levels of variance (equation (10)). Finally, if mutations of very large or very small effect are less likely to contribute to adaptation, then the fixation process acts to restrict the distribution towards mutations of medium size [38]. As such, the levels of observed epistasis should increase steadily for new mutations, standing variation and differences that are fixed between populations.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors are very grateful to Grzegorz Kudla, Anna Puchta, Elena Kuzmin, Santiago Elena and Rafael Sanjuan for providing their data and helpful clarifications. We are also grateful to Guillaume Martin, Denis Roze, Nicolas Bierne, Chris Illingworth and Fyodor Kondrashov for their useful discussions. The authors thank the editors and two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on the article.

Data accessibility

Simulation code is provided as electronic supplementary material. The yeast data are available in reference [1].

Authors' contributions

Both authors designed the study, analysed the data and wrote the manuscript. J.J.W. carried out the modelling. Both authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be held accountable for the content therein.

Competing interests

We declare no competing interests.

Funding

C.F. is supported by an IST fellowship (Marie Sklodowska-Curie Co-Funding European programme).

References

- 1.Puchta O, Cseke B, Czaja H, Tollervey D, Sanguinetti G, Kudla G. 2016. Network of epistatic interactions within a yeast snoRNA Science 352, 840–844. ( 10.1126/science.aaf0965) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimura M, Maruyama T. 1966. The mutational load with epistatic gene interactions in fitness. Genetics 54, 1337–1351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lewontin RC. 1974. The genetic basis of evolutionary change. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kondrashov AS. 1988. Deleterious mutations and the evolution of sexual reproduction. Nature 336, 435–440. ( 10.1038/336435a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kondrashov AS. 1995. Contamination of the genome by very slightly deleterious mutations: why have we not died 100 times over? J. Theor. Biol. 175, 583–594. ( 10.1006/jtbi.1995.0167) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otto SP, Feldman MW. 1997. Deleterious mutations, variable epistatic interactions, and the evolution of recombination. Theor. Popul. Biol. 51, 134–147. ( 10.1006/tpbi.1997.1301) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips PC, Otto SP, Whitlock MC. 2000. Beyond the average: the evolutionary importance of gene interactions and variability of epistatic effects. In Epistasis and the evolutionary process (eds Wolf JB, Brodie ED III, Wade MJ), pp. 20–38. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kouyos RD, Silander OK, Bonhoeffer S. 2007. Epistasis between deleterious mutations and the evolution of recombination. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 308–315. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2007.02.014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Peck JR, Waxman D, Welch JJ. 2012. Hidden epistatic interactions can favour the evolution of sex and recombination. PLoS ONE 7, e48382 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0048382) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charlesworth B. 2013. Why we are not dead one hundred times over. Evolution 67, 3354–3361. ( 10.1111/evo.12195) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fraïsse C, Gunnarsson PA, Roze D, Bierne N, Welch JJ. 2016. The genetics of speciation: insights from Fisher’s geometric model. Evolution 70, 1450–1464 ( 10.1111/evo.12968) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barton NH. 2017. How does epistasis influence the response to selection? Heredity 118, 96–109. ( 10.1038/hdy.2016.109) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simon A, Bierne N, Welch JJ. 2018. Coadapted genomes and selection on hybrids: Fisher’s geometric model explains a variety of empirical patterns. Evol. Lett. 2, 472–498. ( 10.1002/evl3.66) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mukai T. 1969. The genetic structure of natural populations of Drosophila melanogaster. VII. Synergistic interaction of spontaneous mutant polygenes controlling viability. Genetics 61, 749–761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elena SF, Lenski RE. 1997. Test of synergistic interactions among deleterious mutations in bacteria. Nature 390, 395–398. ( 10.1038/37108) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.West SA, Peters AD, Barton NH. 1998. Testing for epistasis between deleterious mutations. Genetics 149, 435–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Halligan DL, Keightley PD. 2009. Spontaneous mutation accumulation studies in evolutionary genetics. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 40, 151–172. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.39.110707.173437) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlesworth B. 1990. Mutation-selection balance and the evolutionary advantage of sex and recombination. Genet. Res. 55, 199–221. ( 10.1017/s0016672300025532) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilke CO, Adami C. 2001. Interaction between directional epistasis and average mutational effects. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 268, 1469–1474. ( 10.1098/rspb.2001.1690) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fisher R. 1930. The genetical theory of natural selection. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martin G. 2014. Fisher’s geometrical model emerges as a property of complex integrated phenotypic networks. Genetics 197, 237–255. ( 10.1534/genetics.113.160325) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lande R. 1980. The genetic covariance between characters maintained by pleiotropic mutations. Genetics 94, 203–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peck JR, Barreau G, Heath S. 1997. Imperfect genes, Fisherian mutation and the evolution of sex. Genetics 145, 1171–1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin G, Lenormand T. 2006. The fitness effect of mutations across environments: a survey in light of fitness landscape models. Evolution 60, 2413–2427. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01878.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tenaillon O, Silander OK, Uzan JP, Chao L. 2007. Quantifying organismal complexity using a population genetic approach. PLoS ONE 2, e217 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0000217) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gros PA, Nagard HL, Tenaillon O. 2009. The evolution of epistasis and its links with genetic robustness, complexity and drift in a phenotypic model of adaptation. Genetics 182, 277–293. ( 10.1534/genetics.108.099127) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Blanquart F, Achaz G, Bataillon T, Tenaillon O. 2014. Properties of selected mutations and genotypic landscapes under Fisher’s geometric model. Evolution 68, 3537–3554 ( 10.1111/evo.12545) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roze D, Blanckaert A. 2014. Epistasis, pleiotropy, and the mutation load in sexual and asexual populations. Evolution 68, 137–149. ( 10.1111/evo.12232) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin G, Lenormand T. 2006. A general multivariate extension of Fisher’s geometrical model and the distribution of mutation fitness effects across species. Evolution 60, 893–907. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01169.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manna F, Martin G, Lenormand T. 2011. Fitness landscapes: an alternative theory for the dominance of mutation. Genetics 189, 923–937. ( 10.1534/genetics.111.132944) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sousa A, Magalhães S, Gordo I. 2011. Cost of antibiotic resistance and the geometry of adaptation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1417–1428 ( 10.1093/molbev/msr302) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin G, Elena SF, Lenormand T. 2007. Distributions of epistasis in microbes fit predictions from a fitness landscape model. Nat. Genet. 39, 555–560. ( 10.1038/ng1998) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maclean RC, Perron GG, Gardner A. 2010. Diminishing returns from beneficial mutations and pervasive epistasis shape the fitness landscape for rifampicin resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Genetics 186, 1345–1354. ( 10.1534/genetics.110.123083) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Perfeito L, Sousa A, Bataillon T, Gordo I. 2013. Rates of fitness decline and rebound suggest pervasive epistasis. Evolution 68, 150–162 ( 10.1111/evo.12234) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinreich DM, Knies JL. 2013. Fisher’s geometric model of adaptation meets the functional synthesis: data on pairwise epistasis for fitness yields insights into the shape and size of phenotype space. Evolution 67, 2957–2972. ( 10.1111/evo.12156) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blanquart F, Bataillon T. 2016. Epistasis and the structure of fitness landscapes: are experimental fitness landscapes compatible with Fisher’s model? Genetics 203, 847–862. ( 10.1534/genetics.115.182691) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanjuán R, Moya A, Elena SF. 2004. The contribution of epistasis to the architecture of fitness in an RNA virus. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 15 376–15 379. ( 10.1073/pnas.0404125101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Orr HA. 1998. The population genetics of adaptation: the distribution of factors fixed during adaptive evolution. Evolution 52, 935–949. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1998.tb01823.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Welch JJ, Waxman D. 2003. Modularity and the cost of complexity. Evolution 57, 1723–1734. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2003.tb00581.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chevin LM, Martin G, Lenormand T. 2010. Fisher’s model and the genomics of adaptation: restricted pleiotropy, heterogenous mutation, and parallel evolution. Evolution 64, 3213–3231 ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01058.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lourenço J, Galtier N, Glémin S. 2011. Complexity, pleiotropy, and the fitness effect of mutations. Evolution 65, 1559–1571. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01237.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lynch M, Walsh B. 1998. Genetics and analysis of quantitative traits. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Orr HA. 2000. Adaptation and the cost of complexity. Evolution 54, 13–20. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00002.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wingreen NS, Miller J, Cox EC. 2003. Scaling of mutational effects in models for pleiotropy. Genetics 164, 1221–1228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liberman U, Feldman MW. 2006. Evolutionary theory for modifiers of epistasis using a general symmetric model. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 19 402–19 406. ( 10.1073/pnas.0608569103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desai MM, Weissman D, Feldman MW. 2007. Evolution can favor antagonistic epistasis. Genetics 177, 1001–1010. ( 10.1534/genetics.107.075812) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sanjuán R, Elena SF. 2006. Epistasis correlates to genomic complexity. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 14 402–14 405. ( 10.1073/pnas.0604543103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Belshaw R, Gardner A, Rambaut A, Pybus OG. 2008. Pacing a small cage: mutation and RNA viruses. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 188–193 ( 10.1016/j.tree.2007.11.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Simulation code is provided as electronic supplementary material. The yeast data are available in reference [1].