Abstract

Background

The overlap between eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) has not been extensively examined. We aimed to assess the prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia in patients with IBD.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study using diagnostic codes to identify adults with EoE and IBD between 2008 and 2016 at a tertiary care center. Electronic medical records were reviewed to extract clinical, endoscopic, and treatment data. Patients with esophageal eosinophilia and IBD were compared to EoE cases without IBD.

Results

Of 621 EoE patients and 4,814 IBD patients identified, 35 had a code for both diseases and 12 were confirmed to have overlapping IBD and esophageal eosinophilia. The prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia in IBD was 12/4814 (0.25%), and the prevalence of confirmed EoE in IBD was 5/4,814 (0.10%). There were no substantial clinical, endoscopic, or histologic differences between EoE patients with and without IBD. IBD was diagnosed before esophageal eosinophilia 92% of the time, with an average time between diagnoses of 9.6 years. Of the IBD patients, 71% were started on biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor-α therapy an average of 7.6 years prior to developing esophageal eosinophilia.

Conclusions

The prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia in IBD is 5 times higher than expected in the general population (0.25 vs. 0.05%) and EoE in IBD is 2 times higher than expected (0.10 vs. 0.05%). Upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms in patients with IBD should merit evaluation not only for upper GI Crohn's disease, but also for esophageal eosinophilia.

Keywords: Eosinophilic esophagitis, Inflammatory bowel disease, Prevalence, Epidemiology

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an immune/antigen-mediated disease characterized by symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and an eosinophil-predominant infiltration of the esophagus [1]. Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), including both Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC), are conditions characterized by dysregulation of the mucosal immune system in response to bacteria in the intestines [2, 3]. In this context, both EoE and IBD can be considered chronic inflammatory conditions, although EoE is limited to the esophagus while IBD can affect many areas of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract [4, 5]. Whereas EoE is a “young” disease which was only recognized as a distinct clinical diagnosis in the early 1990s with the first diagnostic guidelines published 2007 [6, 7], IBD has been diagnosed since the early 20th century [6, 8, 9, 10].

There are a number of parallels between EoE and IBD beyond GI tract inflammation [4]. These include similar potential mechanisms (a genetic susceptibility in the setting of an environmental exposure), evolving epidemiology (increasing incidence; more common in developed countries; more common in younger patients), inflammatory and fibrotic phenotypes, and general therapeutic principles (induce and then maintain remission) [4]. Despite this, the extent of overlap between EoE and IBD in individual patients has not been well characterized. In preliminary data presented by Bhatia et al. [11], there was an increased prevalence of IBD in pediatric and adolescent EoE patients, and similar data for adults was reported in a large pathology database, but these data have yet to be confirmed [12].

Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia in patients with IBD and better elucidate similarities and differences between EoE patients with and without IBD. We hypothesized that EoE in IBD would be more prevalent than EoE in the general population.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Hospitals from 2008 to 2016. To identify subjects in a comprehensive fashion, the International Classification of Disease (ICD)-9 and 10 diagnostic codes were used to search a central data repository for adults with diagnoses of EoE (530.13; K20.0) and IBD (555.x and 556.x; K50.x, K51.x) between 2008 (the first year for which there was an administrative code for EoE) and 2016. In addition, so that we could confirm the diagnosis of EoE, all patients had to have an endoscopy performed at a UNC Hospital. After the identification of potential qualifying subjects, cases of EoE were included if they were confirmed to have been diagnosed as per 2007, 2011, or 2013 guidelines [1, 6, 10]. We also included cases of esophageal eosinophilia and clinically suspected EoE. Cases of IBD were included if they had clinical symptoms, endoscopic abnormalities, and histologic changes consistent with either CD or UC, as well as a diagnosis of CD or UC in the chart. Electronic medical records were reviewed using a standardized electronic form to extract clinical, endoscopic, histologic, and, for patients with EoE/IBD overlap, IBD-specific treatment data. Additional data of interest included demographics, primary symptoms, and EoE endoscopic phenotype (inflammatory, with exudates, furrows, or edema; fibrostenotic, with rings or strictures; or mixed, with both features). This study was approved by the UNC institutional review board.

For analysis, descriptive statistics were used to characterize the cohort. For patients identified with esophageal eosinophilia, we assessed whether the diagnosis of EoE was confirmed, whether the eosinophilia was isolated to the esophagus, or whether there was also a more diffuse eosinophilic GI disease such as eosinophilic gastroenteritis or colitis. We then compared the clinical characteristics of EoE cases without IBD to those with isolated esophageal eosinophilia and IBD to determine differences in demographics, symptoms, baseline EGD findings, EoE endoscopic phenotype, and baseline eosinophil counts. Categorical variables were compared with χ2 and continuous variables were compared with a two-sample t test. All data analysis was performed using Stata 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Study Subjects

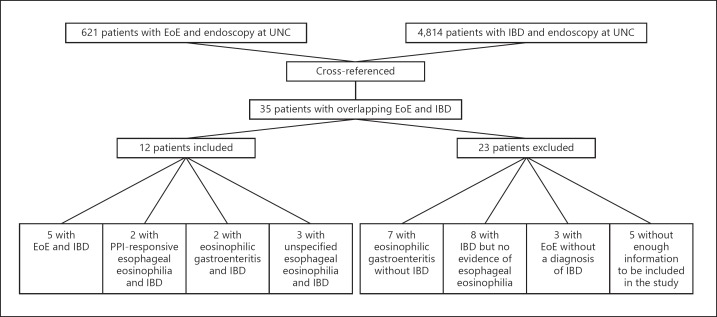

A total of 621 EoE patients and 4,814 IBD patients met the initial inclusion criteria, and 35 had codes for both EoE and IBD (Fig. 1). Of these, 23 were excluded after chart review for either not having a confirmed diagnosis of IBD (n = 10), not having esophageal eosinophilia (n = 8), or not having enough information to make a determination (n = 5). There were 12 patients with overlapping IBD and esophageal eosinophilia. For the patients with IBD, 7 had CD, 4 had UC, and 1 had indeterminate colitis. For the patients with esophageal eosinophilia, 5 had EoE defined as a non-response to a PPI trial (mean age 25 ± 6 years, 60% male, 100% white, peak eosinophil count of 57 ± 31 eosinophils per high power field [eos/hpf]), 2 had PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia (mean age 50 ± 14 years, 100% male, 100% white, peak of 57 ± 23 eos/hpf prior to the PPI trial), 3 had unspecified esophageal eosinophilia where there was no follow-up so the response to PPI could not be assessed (mean age 27 ± 12 years, 67% male, 100% white, 35 ± 22 eos/hpf), and 2 had eosinophilic gastroenteritis with esophageal involvement (mean age 26 ± 2 years, 50% male, 100% white, peak esophageal eosinophil count of 45 eos/hpf).

Fig. 1.

Patient sources and flow through the study, showing identification of overlap of esophageal eosinophilia and IBD. After identifying potential overlapping esophageal eosinophilia and IBD cases (n = 35), cases and overlap were confirmed and classified after chart review.

Prevalence of EoE in IBD

Overall, the prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia in IBD was 12/4,814 (0.25%) and the prevalence of confirmed EoE in IBD was 5/4,814 (0.10%). The prevalence of IBD in esophageal eosinophilia was 12/621 (1.9%), and the prevalence of IBD in confirmed EoE was 5/621 (0.81%).

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

There were no substantial clinical, endoscopic, or histologic differences between EoE patients without IBD and those with overlapping isolated esophageal eosinophilia and IBD (Table 1); patients with eosinophilic gastroenteritis were not included in this analysis. Age at diagnosis was similar for EoE patients without IBD and in those with isolated esophageal eosinophilia with IBD (26.1 ± 18.4 vs. 30.5 ± 13.2 years; p = 0.45). The majority of patients were male in both groups. Even though the esophageal eosinophilia with IBD group was 100% white, this was not significantly different from the EoE without IBD group (87%; p = 0.22). The most common symptoms in those with EoE without IBD and overlapping esophageal eosinophilia and IBD were dysphagia, heartburn, and abdominal pain. Both patient groups had a similar length of symptoms prior to diagnosis, with 7.3 ± 8.6 years for EoE without IBD, and 8.3 ± 11.1 years for isolated esophageal eosinophilia with IBD (p = 0.73). A substantial portion of the patients in both groups had atopy. On baseline endoscopy, there was a trend towards a higher percentage of strictures (22 vs. 0%, p = 0.13) and dilations performed (23 vs. 0%, p = 0.12) in the EoE without IBD group. However, baseline eosinophil counts were similar, with a peak of 65.4 ± 44.7 eos/hpf for EoE without IBD and 50.9 ± 26.7 for isolated esophageal eosinophilia with IBD.

Table 1.

Characteristics of EoE cases without IBD compared with isolated esophageal eosinophilia cases with IBD

| EoE with no IBD (n = 616) | Isolated esophageal eosinophilia with IBD (n = 10) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 26.1±18.4 | 30.5±13.2 | 0.45 |

| Male | 461 (75) | 7 (70) | 0.93 |

| White Symptoms |

536 (87) | 10 (100) | 0.22 |

| Dysphagia | 472 (77) | 6 (60) | 0.45 |

| Heartburn | 250 (41) | 4 (44) | 0.72 |

| Abdominal pain | 143 (23) | 2 (20) | 0.88 |

| Symptom length prior to diagnosis, years Atopy | 7.3±8.6 | 8.3±11.1 | 0.73 |

| Rhinitis/sinusitis | 260 (42) | 3 (30) | 0.50 |

| Asthma | 162 (26) | 1 (10) | 0.27 |

| Food allergy Baseline EGD findings1 | 177 (29) | 1 (10) | 0.18 |

| Rings | 301 (49) | 4 (44) | 0.97 |

| Stricture | 137 (22) | 0 (0) | 0.13 |

| Narrowing | 96 (16) | 1 (11) | 0.78 |

| Furrows | 379 (62) | 4 (44) | 0.75 |

| Exudates/white plaques | 232 (38) | 2 (22) | 0.43 |

| Edema/decreased vascularity | 202 (33) | 3 (33) | 0.84 |

| Dilation performed | 143 (23) | 0 (0) | 0.12 |

| EoE phenotype | 0.93 | ||

| Inflammatory | 241 (39) | 3 (33) | |

| Mixed | 330 (54) | 5 (55) | |

| Fibrostenotic | 95 (15) | 1 (11) | |

| Baseline eosinophil counts, eos/hpf | 65.4±44.7 | 50.9±26.7 | 0.31 |

Data are presented as the mean ± SD or n (%). IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis.1n = 9 for the esophageal eosinophilia/IBD overlap group as data for endoscopic findings from 1 EGD was missing.

IBD Diagnosis and Treatments

IBD was diagnosed before esophageal eosinophilia 92% of the time with an average time between diagnoses of 9.6 years (Table 2); 58% of patients had CD, and 33% of patients had UC; 8.3% had a mixed IBD phenotype. A total of 57% of CD patients had an EoE inflammatory phenotype and 29% had an EoE stricturing phenotype. The CD location included the upper GI tract in 14%, terminal ileum in 43%, colon in 14%, and ileocolonic in 43%. There was a high rate (57%) of perianal disease in this group of CD patients. Three patients with CD had extraintestinal manifestations, including 2 with arthritis and 1 with rosacea. No patients had pyoderma gangrenosum, erythema nodosum, primary sclerosing cholangitis, oral involvement, or ocular involvement. A total of 33% of CD patients had a history of prior bowel resection. None of the UC patients were ever on biologic anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) therapy compared to 86% of the CD patients. Of the patients prescribed an anti-TNF, 71% started prior to developing esophageal eosinophilia, with an average of 7.6 years prior to diagnosis. Prior to the diagnosis of esophageal eosinophilia, 33% of IBD patients had a prior EGD with esophageal biopsy (75% for symptoms and 25% for CD staging), all of which were normal.

Table 2.

Characteristics of IBD cases diagnosed with esophageal eosinophilia

| Esophageal | EoE | PPI-responsive | Eosinophilic | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eosinophilia | (n = 5) | esophageal | gastroenteritis | (n = 12) | |

| unspecified | eosinophilia | (n = 2) | |||

| (n = 3) | (n = 2) | ||||

| IBD type | |||||

| CD | 3 (100) | 1 (20) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 7 (58) |

| UC | 0 (0) | 4 (80) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 4 (33) |

| Mixed | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 1 (8) |

| IBD diagnosed before EoE,n (%; average years) Family history | 3 (100; 13) | 5 (100; 5.8) | 2 (100; 11) | 1 (50; 14.3) | 11 (98; 9.6) |

| EoE | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| IBD | 1 (33) | 1 (20) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 4 (33) |

| CD location | |||||

| Terminal ileum | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 3 (43) |

| Colonic | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) |

| Ileocolonic | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 3 (43) |

| CD upper GI involvement CD phenotype | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) |

| Inflammatory | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (100) | 4 (57) |

| Stricturing | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 2 (29) |

| Penetrating | 0 (0) | 1 (100) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (14) |

| CD with perianal disease Anti-TNF use ever | 2 (67) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 4 (57) |

| CD | 2 (67) | 1 (100) | 2 (100) | 1 (100) | 6 (86) |

| Ulcerative colitis | – | 0 (0) | – | – | 0 (0) |

| Mixed | – | – | 1 (100) | – | 1 (100) |

| Prior bowel resection | 1 (33) | 1 (20) | 1 (50) | 0 (0) | 3 (33) |

| Prior perianal procedure | 1 (33) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (50) | 2 (17) |

Data are presented as n (%), or as indicated. IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; CD, Crohn's disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

Discussion

While the pathogenesis of EoE and IBD are thought to be distinct, the two diseases share a number of similar features from the standpoint of gene-environment interaction, evolving epidemiology, potential discordance between symptoms and endoscopic or histologic findings, and treatment paradigms [4, 13, 14]. However, the clinical overlap between these conditions is not well described. In this study examining the overlap between EoE and IBD, several of our findings were notable. First, we found that the prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia in IBD is about 5 times higher than would be expected in the general population (0.25 vs. 0.05%), and that the prevalence of EoE in IBD is about 2 times higher than expected (0.10 vs. 0.05%) [7, 15, 16]. Likewise, the prevalence of IBD in esophageal eosinophilia (1.9 vs. 0.4%) and in EoE (0.8 vs. 0.4%) was higher than the general population [17]. Differentiating by IBD subtype, CD and UC had a prevalence rate of 0.15 and 0.08% in EoE, respectively. Our study shows lower prevalence rates than preliminary data detailed in previous studies. In those studies, Bhatia et al. [11] cited a prevalence rate of IBD in EoE of 4.2%, and McIntire et al. [12] described a prevalence rate of UC in esophageal eosinophilia of 1.7–2.9% (compared to 1% of UC in controls) and CD in esophageal eosinophilia of 0.4–1.9% (compared to 0.5% of CD in controls). Similarly, Capucilli et al. [18] showed that the rate of IBD in children was found to be 0.7% in EoE patients, and 0.2% in non-EoE patients.

Another notable finding from our study was that, in general, patients with esophageal eosinophilia and IBD were very similar across a range of clinical, endoscopic, and histologic features as compared to EoE cases without IBD. However, we did find a trend towards the increased likelihood of strictures and dilation in EoE without IBD compared to isolated eosinophilia with IBD. This could suggest that the inflammatory form of EoE is more likely to be associated with IBD, but this would have to be confirmed in future studies. This is intriguing as IBD has been described to start with an inflammatory phenotype which, untreated, can progress to a fibrotic phenotype, and there are now strong data in EoE to suggest that the inflammatory phenotype of EoE progresses to fibrostenosis with diagnostic delay or lack of treatment [7, 19, 20, 21]. Data from the abstracts published by Bhatia et al. [11] and McIntire et al. [12] did not delineate specific clinical or endoscopic features beyond disease diagnoses. McIntire et al. [12] did describe an increase in the prevalence of IBD in patients with higher numbers of eosinophils (> 60 eos/hpf compared to 15–60 eos/hpf).

We also found that IBD was diagnosed earlier than esophageal eosinophilia or EoE in patients with both conditions, rather than EoE being diagnosed prior to IBD. Interestingly, when EGD was performed on IBD patients prior to the diagnosis of esophageal eosinophilia, there were no eosinophils seen on biopsy, showing that the EoE was not present at the time of IBD diagnosis, but developed later in the disease course. This raises the question of whether this increase is a consequence of IBD or the medications used to treat IBD. Several links between IBD and EoE already exist. For instance, studies show a relationship between EoE and autoimmune diseases [22, 23]. In a study performed by Jensen et al. [23], it was shown that EoE patients had a 35% higher chance of having more than one autoimmune diagnosis, when compared to non-EoE patients (OR 1.35, 95% CI 1.25–1.47). Peterson et al. [22] demonstrated that first-degree relatives of patients with EoE had higher risks of autoimmune conditions including CD and UC. In addition, previous studies show an increase in the number of serum and mucosal eosinophils in IBD [24, 25]. Click et al. [24] demonstrated that peripheral blood eosinophilia is present in approximately 20% of adult IBD patients and is associated with worsened clinical outcomes in patients with IBD. Similar findings were reproduced in children [26]. In theory, this could mean that IBD patients with peripheral blood eosinophilia represent a unique phenotype that is associated with comorbidities such as asthma and allergies, the same atopic presentation seen in EoE patients. Likewise, EoE is also known to have high levels of peripheral eosinophilia, and the eosinophils seen in UC and EoE have been shown to have similar markers such as diminished expression of CCR3 and CD44 [27]. Click et al. [24] also showed that peripheral eosinophilia was associated with elevated levels of CRP, which could suggest an increased level of inflammation in IBD patients with peripheral eosinophilia. Other studies demonstrate that there are increased eosinophils in the histologic staining of mucosa collected from patients with active IBD [25, 28]. While further research is required to answer the question of exactly how IBD is associated with EoE, our results suggest that upper GI symptoms in patients with IBD should merit evaluation not only for upper GI CD, but also for esophageal eosinophilia. Moreover, biologic anti-TNFs are already well-known IBD treatments but have not been previously shown to be effective for treating EoE, though some novel disease-specific EoE biologic treatments are under development [29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36].

The limitations to the present study include it being based on a single tertiary center experience, where referrals to specialists in EoE and IBD might cause bias that could limit the study's generalizability. The study is also retrospective, with the usual associated limitations including missing data. Indeed, we identified 5 patients with overlapping EoE and IBD ICD codes who had to be eliminated from inclusion in the data analysis due to lack of adequate information. However, this study leveraged a large patient database, identified all possible subjects with EoE and IBD in our health system, and utilized rigorous data extraction protocols and strict criteria to categorize patients and confirm case status.

In conclusion, we identified overlap between EoE and IBD. The prevalence of esophageal eosinophilia in IBD is 5 times higher than expected in the general population, and EoE in IBD is 2 times higher than expected. While the reasons for this observation are not currently known, it is intriguing that our identified cases did not have esophageal eosinophilia or EoE at the time of IBD diagnosis. Therefore, clinicians should have a low threshold based upon clinical findings to perform EGDs in patients with IBD, particularly if symptoms develop after IBD diagnosis, and similarly to perform colonoscopies in patients with EoE if lower GI symptoms develop.

Statement of Ethics

This study was approved by the UNC institutional review board.

Disclosure Statement

Dr. Dellon is a consultant for Adare, Alivio, Allakos, Banner, Calypso, Enumeral, EsoCap, GSK, Receptos/Celegene, Regeneron, Robarts, and Shire, receives research funding from Adare, Allakos, Meritage, Miraca, Nutricia, Receptos/Celgene, Regeneron, and Shire, and has received an educational grant from Banner and Holoclara.

Dr. Long is a consultant for AbbVie, Takeda, UCB, Janssen, Pfizer, and Target Pharmasolutions. She has grant support from Pfizer and Takeda.

None of the other authors report any potential conflicts of interest with this study.

Funding Sources

This study was funded in part by NIH award T32 DK007634 (B.K., D.A.).

References

- 1.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:3–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.040. e6; quiz 21-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schultsz C, Van Den Berg FM, Ten Kate FW, Tytgat GN, Dankert J. The intestinal mucus layer from patients with inflammatory bowel disease harbors high numbers of bacteria compared with controls. Gastroenterology. 1999 Nov;117((5)):1089–97. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70393-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sheehan D, Moran C, Shanahan F. The microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol. 2015 May;50((5)):495–507. doi: 10.1007/s00535-015-1064-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Molina-Infante J, Schoepfer AM, Lucendo AJ, Dellon ES. Eosinophilic esophagitis: what can we learn from Crohn's disease? United European Gastroenterol J. 2017 Oct;5((6)):762–72. doi: 10.1177/2050640616672953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Straumann A, Bauer M, Fischer B, Blaser K, Simon HU. Idiopathic eosinophilic esophagitis is associated with a T(H)2-type allergic inflammatory response. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001 Dec;108((6)):954–61. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.119917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, et al. First International Gastrointestinal Eosinophil Research Symposium (FIGERS) Subcommittees Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology. 2007 Oct;133((4)):1342–63. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and Natural History of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:319–332. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.06.067. e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirsner JB. Historical aspects of inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1988 Jun;10((3)):286–97. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198806000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulder DJ, Noble AJ, Justinich CJ, Duffin JM. A tale of two diseases: the history of inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohn's Colitis. 2014 May;8((5)):341–8. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA, American College of Gastroenterology ACG clinical guideline: evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) Am J Gastroenterol. 2013 May;108((5)):679–92. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhatia EG, Cass AL, Markowitz JE. CAL, Markowitz J.E. Mo1871 Markedly Increased Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease Among Pediatric and Adolescent Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146((5 Supplement 1)):S-677. [Google Scholar]

- 12.McIntire M SH, Genta RM. Eosinophilic Esophagitis Is Associated with an Increased Prevalence of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108((Suppl 1)) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulder DJ, Hookey LC, Hurlbut DJ, Justinich CJ. Impact of Crohn disease on eosinophilic esophagitis: evidence for an altered T(H)1-T(H)2 immune response. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2011 Aug;53((2)):213–5. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318213bf79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suttor VP, Chow C, Turner I. Eosinophilic esophagitis with Crohn's disease: a new association or overlapping immune-mediated enteropathy? Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Mar;104((3)):794–5. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:589–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.008. e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mansoor E, Cooper GS. The 2010-2015 Prevalence of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in the USA: A Population-Based Study. Dig Dis Sci. 2016 Oct;61((10)):2928–34. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Kleinman K, Ollendorf D, Bousvaros A, Grand RJ, et al. The prevalence and geographic distribution of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Dec;5((12)):1424–9. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Capucilli P, Cianferoni A, Grundmeier RW, Spergel JM. Comparison of comorbid diagnoses in children with and without eosinophilic esophagitis in a large population. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018 Dec;121((6)):711–6. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schoepfer AM, Safroneeva E, Bussmann C, Kuchen T, Portmann S, Simon HU, et al. Delay in diagnosis of eosinophilic esophagitis increases risk for stricture formation in a time-dependent manner. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1230–1236. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.08.015. e145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, Rybnicek DA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:577–85. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.10.027. e79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lipka S, Kumar A, Richter JE. Impact of Diagnostic Delay and Other Risk Factors on Eosinophilic Esophagitis Phenotype and Esophageal Diameter. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016 Feb;50((2)):134–40. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peterson K, Firszt R, Fang J, Wong J, Smith KR, Brady KA. Risk of Autoimmunity in EoE and Families: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016 Jul;111((7)):926–32. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD, Dellon ES. High prevalence of co-existing autoimmune conditions among patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144((5)):S491. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Click B, Anderson AM, Koutroubakis IE, Rivers CR, Babichenko D, Machicado JD, et al. Peripheral Eosinophilia in Patients With Inflammatory Bowel Disease Defines an Aggressive Disease Phenotype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017 Dec;112((12)):1849–58. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2017.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wedemeyer J, Vosskuhl K. Role of gastrointestinal eosinophils in inflammatory bowel disease and intestinal tumours. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;22((3)):537–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sadi G, Yang Q, Dufault B, Stefanovici C, Stoffman J, El-Matary W. Prevalence of Peripheral Eosinophilia at Diagnosis in Children With Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016 Apr;62((4)):573–6. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Johnsson M, Bove M, Bergquist H, Olsson M, Fornwall S, Hassel K, et al. Distinctive blood eosinophilic phenotypes and cytokine patterns in eosinophilic esophagitis, inflammatory bowel disease and airway allergy. J Innate Immun. 2011;3((6)):594–604. doi: 10.1159/000331326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mehta P, Furuta GT. Eosinophils in Gastrointestinal Disorders: Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Diseases, Celiac Disease, Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, and Parasitic Infections. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2015 Aug;35((3)):413–37. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eskian M, Khorasanizadeh M, Assa'ad AH, Rezaei N. Monoclonal Antibodies for Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017 doi: 10.1007/s12016-017-8659-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Straumann A, Bussmann C, Conus S, Beglinger C, Simon HU. Anti-TNF-alpha (infliximab) therapy for severe adult eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008 Aug;122((2)):425–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Netzer P, Gschossmann JM, Straumann A, Sendensky A, Weimann R, Schoepfer AM. Corticosteroid-dependent eosinophilic oesophagitis: azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine can induce and maintain long-term remission. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007 Oct;19((10)):865–9. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32825a6ab4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Straumann A, Conus S, Grzonka P, Kita H, Kephart G, Bussmann C, et al. Anti-interleukin-5 antibody treatment (mepolizumab) in active eosinophilic oesophagitis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gut. 2010 Jan;59((1)):21–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.178558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Assa'ad AH, Gupta SK, Collins MH, Thomson M, Heath AT, Smith DA, et al. An antibody against IL-5 reduces numbers of esophageal intraepithelial eosinophils in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011 Nov;141((5)):1593–604. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spergel JM, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, Furuta GT, Markowitz JE, Fuchs G, 3rd, et al. Reslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:456–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.11.044. 463 e1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hirano I, Dellon ES, Hamilton JD, et al. Dupilumab Efficacy and Safety in Adult Patients With Active Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Randomized Double-Blind Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 Trial. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112:AB 20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hirano I, Collins MH, Assouline-Dayan Y, Evans L, Gupta S, Schoepfer AM, et al. RPC4046, a Monoclonal Antibody Against IL13, Reduces Histologic and Endoscopic Activity in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology Epub Nov 2, 2018 doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]