Abstract

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito-transmitted flavivirus and was first linked with congenital microcephaly due to a large outbreak in Northeastern Brazil. An intense scientific investigation then ensued to understand this new teratogenic virus and the spectrum of effects observed in the fetal brain. Initially, attention was focused on the diagnosis of microcephaly and structural brain anomalies in the fetus, because these represented the most overt signs of injury. However, reports now indicate that the spectrum of fetal brain and other anomalies associated with ZIKV exposure is broader and more complex than microcephaly alone and includes subtle fetal brain and ocular injuries; thus, the ability to prenatally diagnose fetal injury associated with ZIKV infection remains limited. New studies indicate that ZIKV imparts disproportionate effects on fetal growth with an unusual femur-sparing profile, potentially providing a new approach to identify viral injury to the fetus. Studies to determine the limitations of prenatal and postnatal testing for detection of ZIKV-associated birth defects and long-term neurocognitive deficits are needed to better guide counseling for women with a possible infectious exposure. It is also imperative that we investigate why ZIKV is so adept at infecting the placenta and the fetal brain to better predict other viruses with similar capabilities that may give rise to new epidemics. The efficiency with which ZIKV evades the early immune response to enable infection of the mother, placenta and fetus is likely critical for understanding why the infection may either be fulminant or limited. As long as we lack a ZIKV vaccine, pregnancies in women not previously immune will be at risk in large parts of the world. Although the decline in the epidemic in the Americas is encouraging, ZIKV outbreaks continue and now include countries in West Africa with limited surveillance for ZIKV and pregnancy outcomes. Further, studies suggest that several emerging viruses may also cause birth defects, including West Nile virus, which is endemic in many parts of the United States. With mosquito-borne diseases increasing worldwide, there remains an urgent need to better understand the pathogenesis of ZIKV and related viruses to protect pregnancies and child health.

Keywords: Congenital Zika syndrome, Zika virus, microcephaly, pregnancy, birth defect

Condensation

This review presents new insights into Zika virus infections, the expanding spectrum of birth defects beyond microcephaly, and how the virus injures the fetus.

Introduction

Zika virus (ZIKV) is a mosquito-transmitted flavivirus that was recently recognized to cause fetal brain injury when an outbreak in Brazil became associated with a surge in microcephaly. The World Health Organization (WHO) rapidly declared the ensuing ZIKV epidemic a global public health emergency. The term Congenital Zika Syndrome (CZS) was coined to describe an array of birth defects associated with ZIKV infection including microcephaly, complex brain malformations and ocular injury.(1–3) Clinical recognition of the CZS is straightforward, which often involves identification of microcephaly.(3–6) Evidence is now accumulating that subtle, but important brain and ocular injuries can also occur in infants with a normal head size at birth. The expanding range of anomalies may be difficult or impossible to diagnose prenatally, and we remain uncertain as to the long-term neurocognitive effects of ZIKV exposure.

Although the initial emergence of ZIKV in the Americas was geographically limited, mosquito-borne infections are increasing globally and in the United States wherein cyclical epidemics are now expected. In addition to ZIKV, several related viruses can also infect the placenta and may pose a threat to pregnancies if a large outbreak or epidemic occurs. It is critical to understand why ZIKV is so adept as a teratogen to predict which emerging viruses may have a similar profile of fetal injury and also to develop antiviral therapeutics that are safe in pregnancy. One major factor in enabling teratogenesis is the ability of the virus to evade the early (innate) immune response, which allows the virus to replicate and infect multiple cells in the human placenta and fetal brain including immature neural stem and progenitor cells.(7–11) Herein, we summarize recent observations on the broadening clinical spectrum of ZIKV-associated injury and how the virus escapes the immune response to silently injure the fetus.

Congenital Zika Syndrome and Diagnostic Challenges

The initial descriptions of radiologic findings associated with the CZS were restricted to case series of infants with extensive fetal brain injury and severe microcephaly.(3, 12–15) Classic features include a massive reduction in the parenchymal volume of the brain with ventriculomegaly and abnormalities of the corpus callosum and cortical migration. Ventriculomegaly may be symmetric or asymmetric; if asymmetric, the occipital horns are typically dilated out of proportion to the frontal horns with an associated loss of the parieto-occipital gray and white matter. Intracranial calcifications are most common at the gray-white matter junction, but can also involve periventricular white matter, the basal ganglia and/or thalami. Asymmetry and abnormalities of the gyral patterns may meet diagnostic criteria for polymicrogyria, lissencephaly or pachygyria. The cerebellum is often abnormal and may be absent, atrophic or underdeveloped. Craniofacial disproportion with a sloping forehead, due to frontal lobe hypoplasia, is typical in severe cases and may occur in the absence of microcephaly.(16) In severe cases, skull collapse may be evident with overlapping sutures and redundancy of skin folds. Arthrogryposis, or congenital contractures, may also occur in association with brain stem hypoplasia and thinning of the entire spinal cord.(17) In summary, the extreme phenotype of the CZS is well described and clinically straightforward to diagnose using antenatal ultrasound and/or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and clinical examination.

Although microcephaly is a central feature of the CZS, no single definition for microcephaly captures all infants with ZIKV-associated anomalies or injuries.(18, 19) The Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine recommended defining microcephaly by a fetal head circumference (HC) less than 3 standard deviations (SD) below the mean, when no other anomalies associated with ZIKV are seen.(20) This definition was consistent with standards for diagnosing microcephaly outside of ZIKV exposure and designed to minimize the chance that a fetus with a constitutionally small head would be labeled as microcephalic.(21) A less conservative definition was adopted by the WHO and the International Society for Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, which chose to define ZIKV-associated microcephaly as a HC less than 2 standard deviations (SD) below the mean (Z-score ≤ −2 SD).(22) The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC, USA) similarly defined ZIKV-associated microcephaly as a fetal or neonatal HC less than 2 SD below the mean or the 3rd centile for gestational age.(18) Although these definitions are less conservative, use of a threshold at the 3rd centile may still fail to capture fetuses or neonates with less dramatic reductions in brain parenchyma or excessive intracranial fluid (e.g. ventriculomegaly, evolving hydrocephalus) that compensates for volume loss of the brain.(16, 23) Although one study reported an 83% sensitivity to identify definite or probable CZS(19) using a HC threshold less than 2 SD below the mean (Intergrowth 21st sonographic standards(24)), this cohort was selected based on a clinical suspicion for microcephaly and, thus, this may be an overestimate.(25) Others reported a 10% rate of a normal HC in the context of significant brain anomalies.(21, 26) Note that a sex-independent threshold for microcephaly (single cutoff for neonatal HC by the Integrowth-21st sonographic standard), is more likely to label female infants as microcephalic, because girls tend to have smaller heads than boys.(27)

Diagnosis of CZS or a possible ZIKV-associated anomaly is best made in the context of definitive laboratory evidence of infection, but in many cases it is not possible to be certain that infection occurred.(28) First, populations at risk for ZIKV infections are often in low- and middle-income countries with serious public health challenges for maternal and neonatal care and inadequate resources to allow for widespread ZIKV testing. Even in the United States, a high loss-to-follow-up for pregnant women at risk for travel-acquired ZIKV infections has been documented in several studies.(29, 30) Second, ZIKV infections are often asymptomatic and when symptoms occur, they may be vague (headache, conjunctivitis) and insufficient to trigger contact with a health care provider. Furthermore, other viruses co-circulating with ZIKV (e.g. dengue and Chikungunya viruses) may also present similarly and serologic tests for ZIKV may cross-react with antibodies from past infections with related flaviviruses(31, 32), leading to equivocal results. The limited time window for detecting ZIKV nucleic acids also makes it difficult to detect ZIKV RNA if maternal testing did not occur at the right time. ZIKV IgM is now known to persist longer than 12 weeks, which complicates determining whether an infection occurred during or prior to pregnancy. Finally, ZIKV RNA may be undetectable in the neonate at delivery if exposure occurred early in the pregnancy.(33) Limitations related to diagnostic testing are important factors driving the uncertainty with which birth defects may be attributed to ZIKV infection.

Broadening Spectrum of ZIKV-Associated Fetal Injury

Recent studies have begun to describe a range of more subtle anomalies that are not captured by the original diagnosis of CZS, which poses a clinical challenge to obstetrical providers for women with ZIKV exposure.(34) The CDC has defined a spectrum of birth defects thought to be potentially related to ZIKV infection for the purposes of birth defects surveillance (Box 1).(18) In many cases, the findings are similar to the CZS, but subtle and challenging to detect without access to prenatal or postnatal MRI imaging(34); the sensitivity of antenatal ultrasound may simply be insufficient to detect some fetal injuries. For example, sight-threatening ocular injuries have been described in infants without microcephaly (i.e. optic nerve hypoplasia) that cannot be detected by ultrasound.(16, 35) Even though intracranial calcifications should be easily detected by antenatal ultrasound, there are reports of calcifications first being detected using postnatal cranial ultrasound.(29) It is also possible that neurologic injury, which began with fetal exposure to ZIKV, may continue to evolve in the first year of life and become more obvious over time. Postnatal microcephaly and hydrocephalus are examples of this type of slowly evolving injury that may not be detected at the time of a pregnancy ultrasound or at birth.(16, 23, 36, 37) Although ultrasound is an important tool to detect fetal structural brain anomalies, a normal scan cannot be taken as evidence that the fetus has escaped viral injury. Postnatal testing, as recommended by the CDC, is more likely to detect lesser viral injuries through cranial ultrasound imaging (and/or MRI, if feasible), eye examination, auditory screening (i.e. automated auditory brainstem response), longitudinal developmental assessments and close monitoring of growth.(38)

Box 1. Birth Defects Potentially Related to Zika Virus Infection.

Brain Abnormalities with and without Microcephaly

Congenital microcephaly: HC <3rd centile for gestational age and sex

Intracranial calcifications

Cerebral atrophy

Abnormal cortical formation (lissencephaly, polymicrogyria, pachygyria, schizencephaly, and gray matter heterotopia)

Corpus callosum abnormalities

Cerebellar abnormalities

Porencephaly

Hydranencephaly

Ventriculomegaly* or hydrocephaly*

Fetal brain disruption sequence (severe microcephaly, collapsed skull, overlapping sutures, scalp redundancy)

Other major brain abnormalities (thalamus, hypothalamus, pituitary, basal ganglia or brainstem)

Neural Tube Defects and Other Early Brain Malformations**

Anencephaly or acrania

Encephalocele

Spina bifida without anencephaly

Holoprosencephaly or arhinencephaly

Eye Abnormalities

Microphthalmia or anopthalmia

Coloboma

Congenital cataract

Intraocular calcifications

Chorioretinal anomalies (e.g. atrophy, scarring, macular pallor, retinal hemorrhage and gross pigmentary changes excluding retinopathy of prematurity)

Optic nerve atrophy, pallor and other optic nerve abnormalities

Consequences of Central Nervous System Dysfunction

Congenital contractures (e.g. arthrogryposis, club foot, congenital hip dysplasia) with associated brain abnormalities

Congenital sensorineural hearing loss documented by postnatal testing

Box adapted from the US Centers for Disease Control standard case definition for birth defects potentially associated with ZIKV infection.(18)

*Excludes isolated mild ventriculomegaly without other brain abnormalities or hydrocephalus due to hemorrhage

**Evidence for a link between ZIKV infections and neural tube defects is weaker than for other listed anomalies.

A maternal ZIKV infection is estimated to result in birth defects in 5–13% of cases, with higher rates of anomalies when infection occurs earlier in pregnancy;(39, 40) however, this should be taken only as an estimate given the clinical difficulty in detection of lesser injuries and the large number of asymptomatic infections. Although the incidence of ocular and subtle brain injuries first detected after birth is unknown, it can be inferred from large case series.(16, 29, 41) In a Brazilian cohort of 116 pregnant women with laboratory evidence of ZIKV infection and a rash, 42% of fetuses had abnormal clinical or brain imaging findings.(42) The variety of neurologic findings included epilepsy, dysphagia with feeding difficulties, visual and hearing deficits, spasticity and hypertonicity.(42) In addition, 21% of infants had eye abnormalities; nearly half of these infants were not microcephalic and one-third had no abnormalities identified within the central nervous system at all.(35) In a U.S. cohort of 86 pregnancies from Miami-Dade county with laboratory evidence of ZIKV infection, there was a 9% rate of microcephaly and an even greater frequency of abnormalities on postnatal cranial ultrasound (17%) and eye examination (13%).(29) In both case series, ocular injuries and abnormal postnatal imaging were approximately twice as common as the outcome of microcephaly, which underscores the complexity of congenital ZIKV infections.

A few case studies derived from a case series of ZIKV infections in pregnancy(29) may be informative for the types of abnormalities that might be detected in the non-microcephalic fetus with congenital ZIKV exposure. In the first case, ZIKV infection occurred in the first trimester resulting in maternal fever, rash, myalgias and conjunctivitis. Laboratory testing was positive for a maternal serum ZIKV IgM and plaque reduction neutralization test. The HC of the fetus and neonate was consistent with a normal head size prenatally and at birth; the fetal HC Z-score was 0.2 at 33 weeks, −0.5 at 37 weeks, and 0.1 at birth respectively, according to the Intergrowth 21st standard.(24) Postnatal testing revealed brain volume loss, abnormally smooth frontal and temporal lobes, atrophy of one cerebellar peduncle and a hypopigmented retinal lesion (Fig. 1). Postnatal testing in a second neonate revealed abnormally smooth frontal and temporal lobes with intracranial calcifications (Fig 2A-E). A third infant, with a large HC at birth (96th centile, Z-score 1.8) and no other anomalies, was found to have increased extra-axial fluid collections indicative of evolving hydrocephalus (Figure 2F-G). These cases demonstrate that neonates with a normal head size may have sustained significant fetal brain injuries not captured by the current diagnostic criteria for congenital microcephaly.

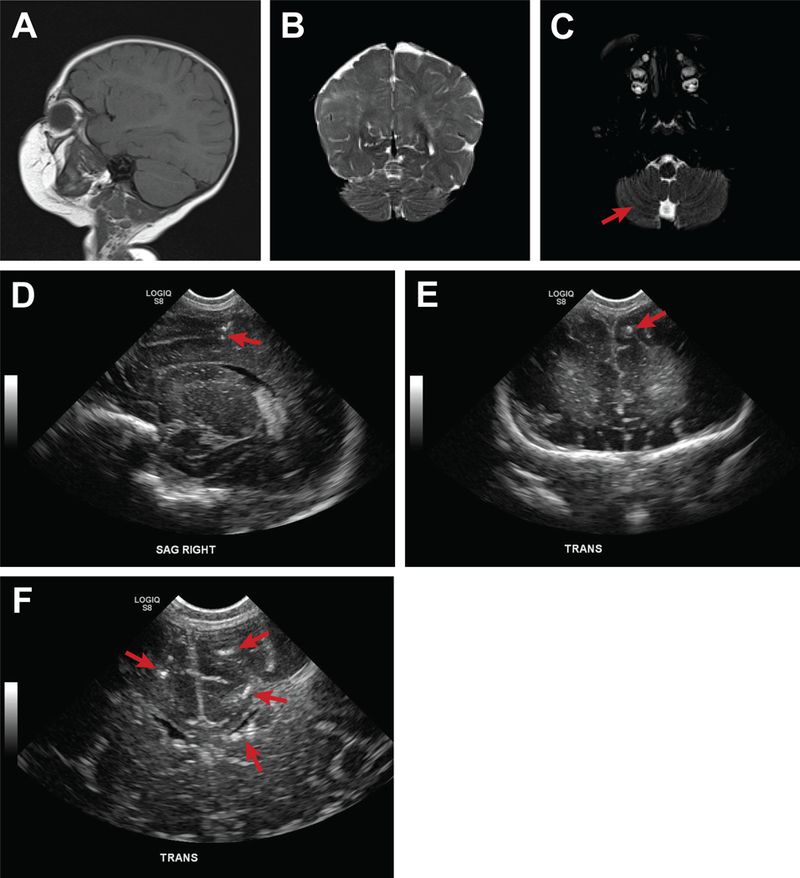

Figure 1.

Multiple brain abnormalities in a non-microcephalic neonate exposed to ZIKV. This figure depicts multiple brain anomalies in a neonate exposed to ZIKV in the first trimester with a normal head size at birth. A postnatal MRI demonstrated: (A) global decrease in cerebral volume, more pronounced on the right, (B) a smooth appearance of the right frontal and anterior temporal lobes suggested a neuronal migration anomaly, and, (C) right cerebellar peduncle atrophy. Diffuse, coarse calcifications throughout the white matter were also observed on postnatal cranial ultrasound (D, E, F, G). At birth, the infant was found to have a left eye hypopigmented retinal lesion (not shown).

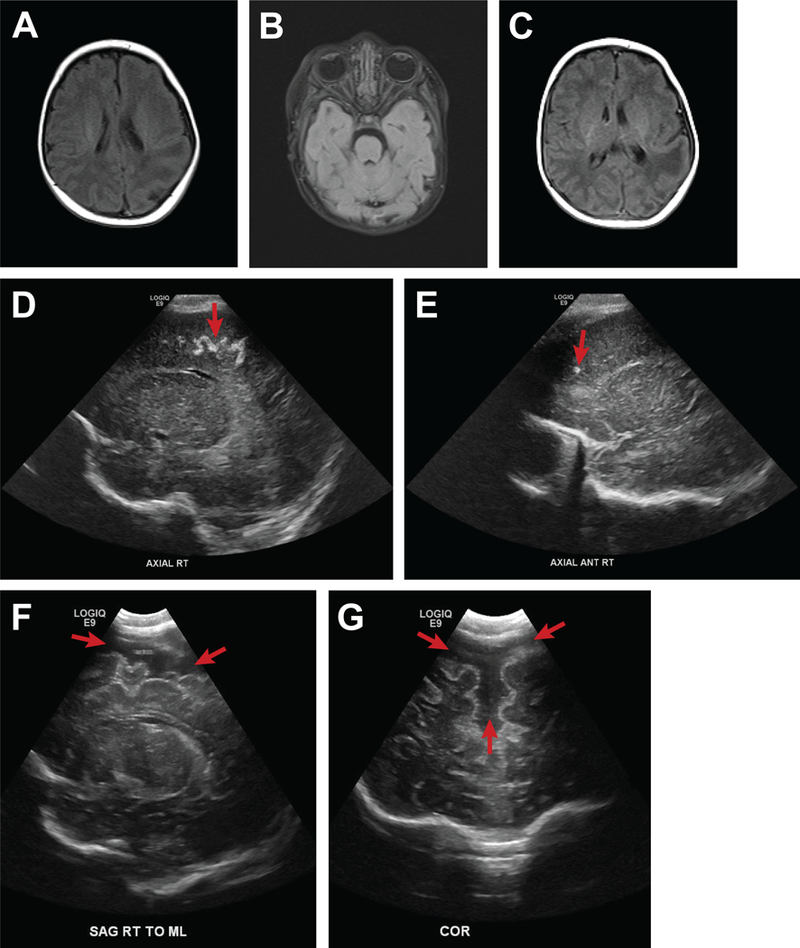

Figure 2.

Other brain abnormalities associated with ZIKV infection. This figure demonstrates the spectrum of ZIKV-associated birth defects beyond the diagnosis of congenital microcephaly. For the first neonate, a postnatal MRI revealed abnormalities of the gyri (A-C; polymicrogyria and loss of gyri) and intracranial serpiginous calcifications (D, E). A second infant exposed to ZIKV in utero with a relatively large head at birth (HC, 96th centile) was noted to have prominent axial fluid collections concerning for impending hydrocephalus (F, G).

Even in the absence of abnormalities identified by postnatal testing, the potential for long-term neurocognitive deficits remains. A recent study in a nonhuman primate model of congenital ZIKV infection revealed injury and loss to neural stem and progenitor cells in the hippocampus, which are highly vulnerable to ZIKV injury, regardless of the time that infection occurred in gestation.(6) These specialized populations of neural progenitors in the hippocampus normally continue to make new neurons at least through late adolescence and possibly into adulthood, which are thought to regulate learning, memory, cognition and emotion/stress response.(43–47) While this particular type of brain injury could not be detected even with prenatal MRI, it would be expected to correlate with the reported early onset of seizures/epilepsy in human infants, perturbations to later learning and memory development, and potentially even later onset depression and age-related cognitive decline.(48–50) A recent study in infant nonhuman primates also correlated ZIKV infection with hippocampal growth arrest, dysfunctional connectivity by functional MRI, and abnormal socioemotional processing.(51) Longitudinal studies are needed to understand the implications of ZIKV-associated injury to neurogenic cells in the fetus or young children and whether this injury might result in a predisposition to learning disorders, developmental delay or mental illness in childhood and adolescence.

Intrauterine Growth Restriction and Stillbirth

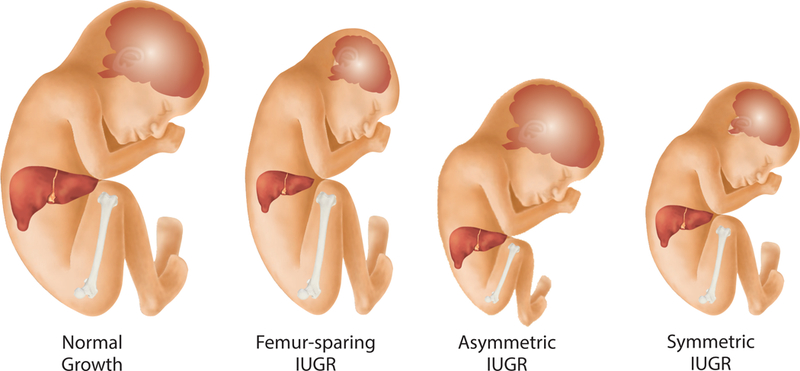

Emerging evidence suggests that ZIKV infection in pregnancy impacts fetal growth and increases the risk of stillbirth. Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a hallmark feature ZIKV infection in rodent models and human pregnancy.(42, 52–55) Two large Brazilian case series of pregnant women with ZIKV infections have reported a profile of “disproportionate” fetal growth, which described a small head in relation to a longer body.(42, 55) Other case series in Brazil(56) and the Caribbean(36) have also reported abnormal growth of the fetal head in the context of a normally growing femur. A similar pattern of growth in early childhood among infants exposed to ZIKV during fetal life revealed a disproportionately small head (65% with HC ≤-3 SD) compared to growth of the skeleton (14% with birth length ≤-3 SD).(14) This profile of “femur-sparing” growth restriction was also observed in nonhuman primate fetuses experimentally infected with ZIKV and was most dramatic when growth of the fetal head arrested (due to brain injury), but femur growth continued normally.(6, 57) The pathogenesis underlying development of a femur-sparing profile of IUGR is unknown, but may occur if ZIKV selectively injures the brain and not the skeleton (Fig. 3). An initial study to determine if a femur-sparing profile of IUGR could be detected in association with ZIKV infection was recently performed in a cohort of 56 pregnant women in New York City, who acquired ZIKV infections through travel.(58) For this study, fetal body ratios with respect to femur length (FL) were calculated [HC:FL or abdominal circumference (AC):FL] based on Intergrowth-21st standards.(58) A femur-sparing pattern of IUGR was detected in 52% of pregnancies based on either a HC:FL or AC:FL less than the 10th centile. Whether aberrant fetal growth or a femur-sparing profile of IUGR is associated with neurologic or ocular injuries is unknown, but future studies should evaluate whether fetal body ratios with respect to FL might provide a biomarker for a broader spectrum of ZIKV-associated fetal injury.

Figure 3.

ZIKV-associated femur-sparing profile of fetal growth restriction. This figure illustrates how a femur-sparing profile of growth restriction, thought to be associated with ZIKV infection, compares to normal fetal growth and other aberrant patterns of growth restriction. A few studies indicate that growth of the femur is often spared in ZIKV infections, which may represent an internal standard to compare growth of the head or abdomen for possible ZIKV-associated viral injury of the fetus.

Recently, several human and animal studies indicate that ZIKV infections can cause spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, which also occur in association with other teratogenic infections.(40, 42, 59–62) Rates of ZIKV-associated pregnancy loss after 20 weeks have been reported to range between 7 and 13%(40, 42); in contrast, background rates of pregnancy loss in women are typically much lower (~0.1%).(63) The mechanism for stillbirth is unknown, but evidence from a nonhuman primate study suggests that placental injury and infarctions may compromise fetal oxygenation.(64) Furthermore, a new study suggests that type I interferon, a key antiviral defensive modulator, can alter placental development and trigger fetal death in the context of ZIKV infection in a mouse model.(65) The overall contribution of ZIKV infection to spontaneous abortion and stillbirth is difficult to estimate due to the absence of reliable data related to lack of data collection and poor recording of data.(66)

How ZIKV Escapes the Immune Response and Emerging Viruses with Similar Potential

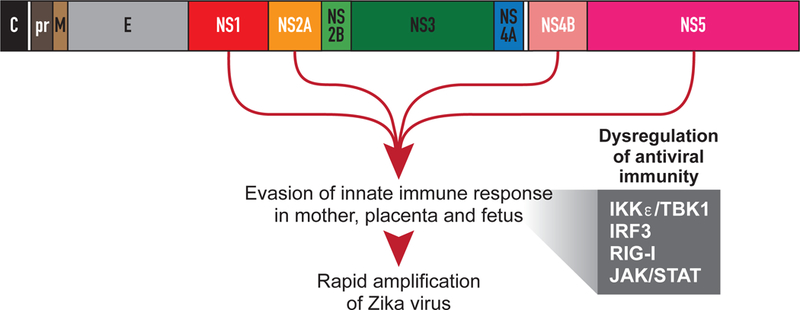

Molecular mechanisms of ZIKV pathogenesis and microcephaly remain poorly understood and particularly, how the virus evades innate immunity to mediate vertical transmission and fetal brain injury.(67) ZIKV, like many flaviviruses, is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected mosquito. In most human infections, there is an acute course with rapid amplification of virus in specific tissues, followed by clearance through the host immune response. ZIKV is unusual among flaviviruses because it can mediate a persistent infection and is detected in genital-mucosal tissues and other sites in the body for weeks to months after initial exposure.(68–72) To facilitate viral replication and spread within the infected host, ZIKV and other flaviviruses antagonize and/or evade the innate immune response, thus bypassing host defenses within the infected cells to promote unchecked viral replication (Fig. 4). The innate immune response plays an essential role in programming a proper adaptive immune response that clears the flavivirus infection.(73, 74) Improperly programmed immunity can lead to a disease state, owing in part to ZIKV dysregulation of the innate immune response. Flavivirus strains that are the most effective disruptors of the innate immune response are associated with an increased virulence and outbreak potential compared with less antagonistic, mildly pathogenic strains. Thus, it is important to understand the mechanisms that flaviviruses use to dysregulate host innate immunity as these directly contribute to human disease outcome.(75, 76)

Figure 4.

Zika virus proteins associated with evasion of the early immune response. This schematic illustrates the protein-coding regions of the ZIKV genome and specific nonstructural (NS) proteins that have been implicated in inhibition of the innate immune response. Abbreviations: C, capsid; pr, precursor; M, membrane; E, envelope; IKKε, Inhibitor of kappa-B kinase subunit epsilon; TBK1, TANK-binding kinase 1; IRF3, Interferon regulatory factor 3; RIG-I, retinoic acid inducible gene I; JAK, Janus kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription.

In the infected cell, flaviviruses sequester their genomic RNA within membranous intracellular compartments(77, 78) as well as modify their RNA to mimic endogenous 5ʹ-cap methylation.(79) These evasion strategies prevent host cell recognition of the viral pathogen-associated molecular pattern, allowing viral replication to continue undetected. Phosphatidylserine incorporation into the virion envelope allows engagement of TAM (Tyro3, Axl and Mer) receptors to promote flavivirus entry and inhibit antiviral signaling via SOCS1 (suppressor of cytokine signaling 1) induction.(80, 81) Additionally, flavivirus non-structural (NS) proteins and subgenomic flavivirus RNA (sfRNA) can directly interfere with host antiviral signaling pathways to suppress immunity.(82–88) For ZIKV, the viral proteins NS1, NS2A, and NS4B have been demonstrated to antagonize the innate immune response at the level of IKKε/TBK1 (Inhibitor of kappa B kinase epsilon/TANK-binding kinase 1) activation(87, 88); whereas, NS5 has been shown to act downstream by binding IRF3 (interferon regulatory factor 3, Fig. 4).(87) ZIKV sfRNA also prevents interferon induction in response to RIG-I-like receptor stimulation by an unresolved mechanism.(82) ZIKV further inhibits innate immunity via disruption of the JAK/STAT (janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription) signaling cascade that is required to direct the expression of any antiviral genes induced by interferon. This antagonism is mediated by the viral protease NS2B/3-stimulated degradation of JAK1(88) while NS5 binds and degrades human STAT2.(84, 86) Other mechanisms of flavivirus innate immune antagonism include induction of major histocompatibility expression (MHC-I) on the surface of infected cells to evade natural killer cell-mediated lysis.(89, 90) The viral NS1 protein can also dysregulate the humoral complement system, thus allowing the virus to evade both direct destruction and destruction of infected cells.(91, 92) Thus, flaviviruses excel at evading the innate immune response by preventing host cell recognition of viral pathogen-associated molecular patterns and inhibiting antiviral signaling pathways.

In support of these in vitro findings, an attenuated (or absent) inflammatory response associated with ZIKV infection in the fetal brain has been reported in pathologic series from both human infants and fetuses(93) and nonhuman primates(6, 57). This pathologic profile contrasts sharply with the cytopathic viral effects and robust inflammatory response, which is more typical for cytomegalovirus, herpes and rubella viruses.(94, 95) The absence of an inflammatory signature may have obscured the viral etiology of fatal cases associated with ZIKV infection before the epidemic in the Americas brought the congenital disease manifestations to light. It is possible that other viruses and related flaviviruses may similarly exert a “silent” profile of fetal injury, which would require a high index of clinical suspicion for detection. Indeed, the pathogenic flavivirus, Japanese encephalitis virus, has been documented to trans-placentally infect developing human fetuses, leading to miscarriage(96, 97), and other related members of the family Flaviviridae are well characterized to vertically transmit in vertebrates.(98, 99) A recent study suggests that several other emerging and ZIKV-related viruses may also infect the placenta and cause fetal demise.(100) Human maternal and fetal tissue explants were highly susceptible to West Nile virus (WNV) and Powassan virus infections, with less efficient infection by the alphaviruses, Mayaro virus and Chikungunya virus (CHIKV); WNV could also infect the fetal brain and cause stillbirth or abortion in an immunocompetent mouse model.(100) Further, a case series of WNV infections in human pregnancies reported neurologic injuries similar to the CZS including meningitis, lissencephaly, and microcephaly.(101) Vertical transmission of CHIKV has been reported with documented neonatal encephalitis and long-term adverse outcomes on child neurocognitive function.(102, 103) Active surveillance of pregnant women for emerging viruses and teratogenesis should occur, because fetal exposure to viral infections is not uncommon; vertical transmission has been documented for a number of viruses in 2% of amniotic fluid samples obtained from asymptomatic women undergoing midtrimester amniocentesis.(104) These studies suggest that emerging flaviviruses may share ZIKV’s teratogenic capacity and that pregnancy outcomes in regions at risk for viral infections with unknown risk to the fetus should be monitored for birth defects.(100)

Conclusions

More than 50 years has passed since the rubella epidemic in the United States, which resulted in an estimated 20,000 births with the congenital rubella syndrome. ZIKV is an equivalent and contemporary threat to pregnancies with a widening array of associated anomalies that is not restricted to microcephaly. Subtle fetal injuries, especially ocular abnormalities, may be impossible to detect prenatally. An unusual femur-sparing profile of growth restriction has been associated with ZIKV infection and may serve as a biomarker for fetal injury in the absence of microcephaly and structural brain anomalies. Additional research to determine the spectrum of fetal injuries and long-term neurocognitive deficits in non-microcephalic neonates is imperative to better understand how to counsel pregnant women with possible ZIKV exposure. In addition, we must also investigate emerging viruses for their teratogenic potential, which may in part reflect their ability to evade the maternal-fetal immune response. The recent demonstration that other viruses, some related to ZIKV, can infect the placenta and invade the brain, suggest that we need to expand our knowledge of teratogenic viruses. Although mosquito-borne diseases continue to increase globally, we remain unprepared to protect pregnancies from ZIKV and other teratogenic viral threats.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Jan Hamanishi for technical assistance with preparation of the figures.

This work was supported by the University of Washington Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, the Keck Foundation (B.R.N) and the National Institutes of Health Grant # AI100989 and AI33976 (L.R and K. A. W), AI083019 (M.G. Jr.), AI104002 (M.G. Jr.), and OD023838 (B.R.N). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or other funders. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Christie L. WALKER, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Marie-Térèse LITTLE, 4th Dimension Biomedical & Research Consulting, Victoria, British Columbia, CANADA.

Justin A. ROBY, Center for Innate Immunity and Immune Disease, Department of Immunology, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Blair ARMISTEAD, Department of Global Health, University of Washington; Center for Global Infectious Disease Research, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, WA.

Michael GALE, Jr., Center for Innate Immunity and Immune Disease, Departments of Immunology, Microbiology and Global Health, University of Washington, Seattle, WA.

Lakshmi RAJAGOPAL, Center for Innate Immunity and Immune Disease, Department of Pediatrics, University of Washington; Center for Global Infectious Disease Research, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, WA.

Branden R. NELSON, Center for Integrative Brain Research, Seattle Children’s Research Institute, Seattle, Washington, United States of America, Seattle, WA.

Noah EHINGER, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States of America.

Brittney MASON, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States of America.

Unzila NAYERI, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States of America.

Christine L. CURRY, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States of America.

Kristina M. ADAMS WALDORF, Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Global Health, Center for Innate Immunity and Immune Disease, University of Washington; Sahlgrenska Academy, Gothenburg University, Sweden, Seattle, WA.

References

- 1.Kleber de Oliveira W, Cortez-Escalante J, De Oliveira WT, do Carmo GM, Henriques CM, Coelho GE, et al. Increase in Reported Prevalence of Microcephaly in Infants Born to Women Living in Areas with Confirmed Zika Virus Transmission During the First Trimester of Pregnancy - Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(9):242–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gulland A Zika virus is a global public health emergency, declares WHO. BMJ 2016;352:i657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Melo AS, Aguiar RS, Amorim MM, Arruda MB, Melo FO, Ribeiro ST, et al. Congenital Zika Virus Infection: Beyond Neonatal Microcephaly. JAMA Neurol 2016;73(12):1407–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mlakar J, Korva M, Tul N, Popovic M, Poljsak-Prijatelj M, Mraz J, et al. Zika Virus Associated with Microcephaly. N Engl J Med 2016. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Petersen LR, Jamieson DJ, Powers AM, Honein MA. Zika Virus. N Engl J Med 2016;374(16):1552–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adams Waldorf KM, Nelson BR, Stencel-Baerenwald JE, Studholme C, Kapur RP, Armistead B, et al. Congenital Zika virus infection as a silent pathology with loss of neurogenic output in the fetal brain. Nat Med 2018;24(3):368–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qian X, Nguyen HN, Song MM, Hadiono C, Ogden SC, Hammack C, et al. Brain-Region-Specific Organoids Using Mini-bioreactors for Modeling ZIKV Exposure. Cell 2016;165(5):1238–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tang H, Hammack C, Ogden SC, Wen Z, Qian X, Li Y, et al. Zika Virus Infects Human Cortical Neural Progenitors and Attenuates Their Growth. Cell Stem Cell 2016;18(5):587–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tabata T, Petitt M, Puerta-Guardo H, Michlmayr D, Wang C, Fang-Hoover J, et al. Zika Virus Targets Different Primary Human Placental Cells, Suggesting Two Routes for Vertical Transmission. Cell Host Microbe 2016;20(2):155–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.El Costa H, Gouilly J, Mansuy JM, Chen Q, Levy C, Cartron G, et al. ZIKA virus reveals broad tissue and cell tropism during the first trimester of pregnancy. Sci Rep 2016;6:35296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jurado KA, Simoni MK, Tang Z, Uraki R, Hwang J, Householder S, et al. Zika virus productively infects primary human placenta-specific macrophages. JCI Insight 2016;1(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soares de Oliveira-Szejnfeld P, Levine D, Melo AS, Amorim MM, Batista AG, Chimelli L, et al. Congenital Brain Abnormalities and Zika Virus: What the Radiologist Can Expect to See Prenatally and Postnatally. Radiology 2016;281(1):203–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schuler-Faccini L, Ribeiro EM, Feitosa IM, Horovitz DD, Cavalcanti DP, Pessoa A, et al. Possible Association Between Zika Virus Infection and Microcephaly - Brazil, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(3):59–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moura da Silva AA, Ganz JS, Sousa PD, Doriqui MJ, Ribeiro MR, Branco MD, et al. Early Growth and Neurologic Outcomes of Infants with Probable Congenital Zika Virus Syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis 2016;22(11):1953–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Fatima Vasco Aragao M, van der Linden V, Brainer-Lima AM, Coeli RR, Rocha MA, Sobral da Silva P, et al. Clinical features and neuroimaging (CT and MRI) findings in presumed Zika virus related congenital infection and microcephaly: retrospective case series study. BMJ 2016;353:i1901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van der Linden V, Pessoa A, Dobyns W, Barkovich AJ, Junior HV, Filho EL, et al. Description of 13 Infants Born During October 2015-January 2016 With Congenital Zika Virus Infection Without Microcephaly at Birth - Brazil. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016;65(47):1343–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aragao M, Brainer-Lima AM, Holanda AC, van der Linden V, Vasco Aragao L, Silva Junior MLM, et al. Spectrum of Spinal Cord, Spinal Root, and Brain MRI Abnormalities in Congenital Zika Syndrome with and without Arthrogryposis. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38(5):1045–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Zika Virus 2018. [Available from: www.cdc.gov/zika.

- 19.Franca GVA, Schuler-Faccini L, Oliveira WK, Henriques CMP, Carmo EH, Pedi VD, et al. Congenital Zika virus syndrome in Brazil: a case series of the first 1501 livebirths with complete investigation. Lancet 2016;388(10047):891–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Committee SfM-FMSP. Ultrasound screening for fetal microcephaly following Zika virus exposure. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016;214(6):B2–B4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanz Cortes M, Rivera AM, Yepez M, Guimaraes CV, Diaz Yunes I, Zarutskie A, et al. Clinical Assessment and Brain Findings in a Cohort of Mothers, Fetuses and Infants Infected with Zika Virus. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Papageorghiou AT, Thilaganathan B, Bilardo CM, Ngu A, Malinger G, Herrera M, et al. ISUOG Interim Guidance on ultrasound for Zika virus infection in pregnancy: information for healthcare professionals. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;47(4):530–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Juca E, Pessoa A, Ribeiro E, Menezes R, Kerbage S, Lopes T, et al. Hydrocephalus associated to congenital Zika syndrome: does shunting improve clinical features? Childs Nerv Syst 2018;34(1):101–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papageorghiou AT, Ohuma EO, Altman DG, Todros T, Cheikh Ismail L, Lambert A, et al. International standards for fetal growth based on serial ultrasound measurements: the Fetal Growth Longitudinal Study of the INTERGROWTH-21st Project. Lancet 2014;384(9946):869–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heukelbach J, Werneck GL. Surveillance of Zika virus infection and microcephaly in Brazil. Lancet 2016;388(10047):846–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hazin AN, Poretti A, Turchi Martelli CM, Huisman TA, Microcephaly Epidemic Research G, Di Cavalcanti Souza Cruz D, et al. Computed Tomographic Findings in Microcephaly Associated with Zika Virus. N Engl J Med 2016;374(22):2193–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Victora CG, Schuler-Faccini L, Matijasevich A, Ribeiro E, Pessoa A, Barros FC. Microcephaly in Brazil: how to interpret reported numbers? Lancet 2016;387(10019):621–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Eppes C, Rac M, Dunn J, Versalovic J, Murray KO, Suter MA, et al. Testing for Zika virus infection in pregnancy: key concepts to deal with an emerging epidemic. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;216(3):209–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shiu C, Starker R, Kwal J, Bartlett M, Crane A, Greissman S, et al. Zika Virus Testing and Outcomes during Pregnancy, Florida, USA, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hall NB, Broussard K, Evert N, Canfield M. Notes from the Field: Zika Virus-Associated Neonatal Birth Defects Surveillance - Texas, January 2016-July 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(31):835–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Granger D, Hilgart H, Misner L, Christensen J, Bistodeau S, Palm J, et al. Serologic Testing for Zika Virus: Comparison of Three Zika Virus IgM-Screening Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assays and Initial Laboratory Experiences. Journal of clinical microbiology 2017;55(7):2127–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felix AC, Souza NCS, Figueiredo WM, Costa AA, Inenami M, da Silva RMG, et al. Cross reactivity of commercial anti-dengue immunoassays in patients with acute Zika virus infection. J Med Virol 2017;89(8):1477–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Reynolds MR, Jones AM, Petersen EE, Lee EH, Rice ME, Bingham A, et al. Vital Signs: Update on Zika Virus-Associated Birth Defects and Evaluation of All U.S. Infants with Congenital Zika Virus Exposure - U.S. Zika Pregnancy Registry, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(13):366–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aragao M, Holanda AC, Brainer-Lima AM, Petribu NCL, Castillo M, van der Linden V, et al. Nonmicrocephalic Infants with Congenital Zika Syndrome Suspected Only after Neuroimaging Evaluation Compared with Those with Microcephaly at Birth and Postnatally: How Large Is the Zika Virus “Iceberg”? AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2017;38(7):1427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zin AA, Tsui I, Rossetto J, Vasconcelos Z, Adachi K, Valderramos S, et al. Screening Criteria for Ophthalmic Manifestations of Congenital Zika Virus Infection. JAMA Pediatr 2017;171(9):847–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sohan K, Cyrus CA. Ultrasonographic observations of the fetal brain in the first 100 pregnant women with Zika virus infection in Trinidad and Tobago. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2017;139(3):278–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petribu NCL, Aragao MFV, van der Linden V, Parizel P, Jungmann P, Araujo L, et al. Follow-up brain imaging of 37 children with congenital Zika syndrome: case series study. BMJ 2017;359:j4188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Adebanjo T, Godfred-Cato S, Viens L, Fischer M, Staples JE, Kuhnert-Tallman W, et al. Update: Interim Guidance for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Management of Infants with Possible Congenital Zika Virus Infection - United States, October 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(41):1089–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Rice ME, Galang RR, Fulton AC, VanMaldeghem K, Prado MV, et al. Pregnancy Outcomes After Maternal Zika Virus Infection During Pregnancy - U.S. Territories, January 1, 2016-April 25, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(23):615–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoen B, Schaub B, Funk AL, Ardillon V, Boullard M, Cabie A, et al. Pregnancy Outcomes after ZIKV Infection in French Territories in the Americas. N Engl J Med 2018;378(11):985–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Felix A, Hallet E, Favre A, Kom-Tchameni R, Defo A, Flechelles O, et al. Cerebral injuries associated with Zika virus in utero exposure in children without birth defects in French Guiana: Case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(51):e9178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brasil P, Pereira JP Jr., Moreira ME, Ribeiro Nogueira RM, Damasceno L, Wakimoto M, et al. Zika Virus Infection in Pregnant Women in Rio de Janeiro. N Engl J Med 2016;375(24):2321–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Spalding KL, Bergmann O, Alkass K, Bernard S, Salehpour M, Huttner HB, et al. Dynamics of hippocampal neurogenesis in adult humans. Cell 2013;153(6):1219–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorrells SF, Paredes MF, Cebrian-Silla A, Sandoval K, Qi D, Kelley KW, et al. Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature 2018;555(7696):377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Boldrini M, Fulmore CA, Tartt AN, Simeon LR, Pavlova I, Poposka V, et al. Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis Persists throughout Aging. Cell Stem Cell 2018;22(4):589–99 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kempermann G, Gage FH, Aigner L, Song H, Curtis MA, Thuret S, et al. Human Adult Neurogenesis: Evidence and Remaining Questions. Cell Stem Cell 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Goncalves JT, Schafer ST, Gage FH. Adult Neurogenesis in the Hippocampus: From Stem Cells to Behavior. Cell 2016;167(4):897–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Toda T, Parylak SL, Linker SB, Gage FH. The role of adult hippocampal neurogenesis in brain health and disease. Mol Psychiatry 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 49.Satterfield-Nash A, Kotzky K, Allen J, Bertolli J, Moore CA, Pereira IO, et al. Health and Development at Age 19–24 Months of 19 Children Who Were Born with Microcephaly and Laboratory Evidence of Congenital Zika Virus Infection During the 2015 Zika Virus Outbreak - Brazil, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017;66(49):1347–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oliveira-Filho J, Felzemburgh R, Costa F, Nery N, Mattos A, Henriques DF, et al. Seizures as a Complication of Congenital Zika Syndrome in Early Infancy. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Mavigner M, Raper J, Kovacs-Balint Z, Gumber S, O’Neal JT, Bhaumik SK, et al. Postnatal Zika virus infection is associated with persistent abnormalities in brain structure, function, and behavior in infant macaques. Sci Transl Med 2018;10(435):DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao6975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miner JJ, Cao B, Govero J, Smith AM, Fernandez E, Cabrera OH, et al. Zika Virus Infection during Pregnancy in Mice Causes Placental Damage and Fetal Demise. Cell 2016;165(5):1081–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cugola FR, Fernandes IR, Russo FB, Freitas BC, Dias JL, Guimaraes KP, et al. The Brazilian Zika virus strain causes birth defects in experimental models. Nature 2016;534(7606):267–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Uraki R, Jurado KA, Hwang J, Szigeti-Buck K, Horvath TL, Iwasaki A, et al. Fetal Growth Restriction Caused by Sexual Transmission of Zika Virus in Mice. The Journal of infectious diseases 2017;215(11):1720–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Silva AA, Barbieri MA, Alves MT, Carvalho CA, Batista RF, Ribeiro MR, et al. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Microcephaly at Birth in Brazil in 2010. Pediatrics 2018;141(2). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oliveira Melo AS, Malinger G, Ximenes R, Szejnfeld PO, Alves Sampaio S, Bispo de Filippis AM. Zika virus intrauterine infection causes fetal brain abnormality and microcephaly: tip of the iceberg? Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2016;47(1):6–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Adams Waldorf KM, Stencel-Baerenwald JE, Kapur RP, Studholme C, Boldenow E, Vornhagen J, et al. Fetal brain lesions after subcutaneous inoculation of Zika virus in a pregnant nonhuman primate. Nat Med 2016;22(11):1256–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walker CL, Merriam AA, Ohuma EO, Dighe MK, Gale M Jr., Rajagopal L, et al. Femur-Sparing Pattern of Abnormal Fetal Growth in Pregnant Women from New York City After Maternal Zika Virus Infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.van der Eijk AA, van Genderen PJ, Verdijk RM, Reusken CB, Mogling R, van Kampen JJ, et al. Miscarriage Associated with Zika Virus Infection. N Engl J Med 2016;375(10):1002–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Schaub B, Monthieux A, Najihoullah F, Harte C, Cesaire R, Jolivet E, et al. Late miscarriage: another Zika concern? Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2016;207:240–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Magnani DM, Rogers TF, Maness NJ, Grubaugh ND, Beutler N, Bailey VK, et al. Fetal demise and failed antibody therapy during Zika virus infection of pregnant macaques. Nat Commun 2018;9(1):1624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Seferovic M, Martin CS, Tardif SD, Rutherford J, Castro ECC, Li T, et al. Experimental Zika Virus Infection in the Pregnant Common Marmoset Induces Spontaneous Fetal Loss and Neurodevelopmental Abnormalities. Sci Rep 2018;8(1):6851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF, Baird DD, Schlatterer JP, Canfield RE, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1988;319(4):189–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirsch AJ, Roberts VHJ, Grigsby PL, Haese N, Schabel MC, Wang X, et al. Zika virus infection in pregnant rhesus macaques causes placental dysfunction and immunopathology. Nat Commun 2018;9(1):263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yockey LJ, Jurado KA, Arora N, Millet A, Rakib T, Milano KM, et al. Type I interferons instigate fetal demise after Zika virus infection. Sci Immunol 2018;3(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Jassir FB, Say L, Chou D, Mathers C, et al. National, regional, and worldwide estimates of stillbirth rates in 2015, with trends from 2000: a systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4(2):e98–e108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lucchese G, Kanduc D. Zika virus and autoimmunity: From microcephaly to Guillain-Barre syndrome, and beyond. Autoimmun Rev 2016;15(8):801–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barzon L, Pacenti M, Franchin E, Lavezzo E, Trevisan M, Sgarabotto D, et al. Infection dynamics in a traveller with persistent shedding of Zika virus RNA in semen for six months after returning from Haiti to Italy, January 2016. Euro Surveill 2016;21(32). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Aid M, Abbink P, Larocca RA, Boyd M, Nityanandam R, Nanayakkara O, et al. Zika Virus Persistence in the Central Nervous System and Lymph Nodes of Rhesus Monkeys. Cell 2017;169(4):610–20 e14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gaskell KM, Houlihan C, Nastouli E, Checkley AM. Persistent Zika Virus Detection in Semen in a Traveler Returning to the United Kingdom from Brazil, 2016. Emerg Infect Dis 2017;23(1):137–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schaub B, Monthieux A, Najioullah F, Adenet C, Muller F, Cesaire R. Persistent maternal Zika viremia: a marker of fetal infection. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2017;49(5):658–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gonce A, Martinez MJ, Marban-Castro E, Saco A, Soler A, Alvarez-Mora MI, et al. Spontaneous Abortion Associated with Zika Virus Infection and Persistent Viremia. Emerg Infect Dis 2018;24(5):933–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Lindenbach BD, Thiel H-J, Rice CM. Flaviviridae: The Viruses and Their Replication. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields Virology, 5th Edition. 1. 5 ed. Philidelphia: Lippincott-Raven Publishers; 2007. p. 1101–52. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Suthar MS, Diamond MS, Gale M. West Nile virus infection and immunity. Nat Rev Microbiol 2013;11(2):115–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Keller BC, Fredericksen BL, Samuel MA, Mock RE, Mason PW, Diamond MS, et al. Resistance to alpha/beta interferon is a determinant of West Nile virus replication fitness and virulence. Journal of virology 2006;80(19):9424–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu WJ, Wang XJ, Mokhonov VV, Shi PY, Randall R, Khromykh AA. Inhibition of interferon signaling by the New York 99 strain and Kunjin subtype of West Nile virus involves blockage of STAT1 and STAT2 activation by nonstructural proteins. Journal of virology 2005;79(3):1934–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fredericksen BL, Gale M Jr. West Nile virus evades activation of interferon regulatory factor 3 through RIG-I-dependent and -independent pathways without antagonizing host defense signaling. Journal of virology 2006;80(6):2913–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miorin L, Albornoz A, Baba MM, D’Agaro P, Marcello A. Formation of membrane-defined compartments by tick-borne encephalitis virus contributes to the early delay in interferon signaling. Virus Res 2012;163(2):660–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Daffis S, Szretter KJ, Schriewer J, Li JQ, Youn S, Errett J, et al. 2 ‘-O methylation of the viral mRNA cap evades host restriction by IFIT family members. Nature 2010;468(7322):452–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen J, Yang YF, Yang Y, Zou P, He Y, Shui SL, et al. AXL promotes Zika virus infection in astrocytes by antagonizing type I interferon signalling. Nat Microbiol 2018;3(3):302–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Meertens L, Labeau A, Dejarnac O, Cipriani S, Sinigaglia L, Bonnet-Madin L, et al. Axl Mediates ZIKA Virus Entry in Human Glial Cells and Modulates Innate Immune Responses. Cell Rep 2017;18(2):324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Donald CL, Brennan B, Cumberworth SL, Rezelj VV, Clark JJ, Cordeiro MT, et al. Full Genome Sequence and sfRNA Interferon Antagonist Activity of Zika Virus from Recife, Brazil. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016;10(10):e0005048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Best SM. The Many Faces of the Flavivirus NS5 Protein in Antagonism of Type I Interferon Signaling. Journal of virology 2017;91(3). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Grant A, Ponia SS, Tripathi S, Balasubramaniam V, Miorin L, Sourisseau M, et al. Zika Virus Targets Human STAT2 to Inhibit Type I Interferon Signaling. Cell Host Microbe 2016;19(6):882–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hertzog J, Dias Junior AG, Rigby RE, Donald CL, Mayer A, Sezgin E, et al. Infection with a Brazilian isolate of Zika virus generates RIG-I stimulatory RNA and the viral NS5 protein blocks type I IFN induction and signalling. Eur J Immunol 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Kumar A, Hou S, Airo AM, Limonta D, Mancinelli V, Branton W, et al. Zika virus inhibits type-I interferon production and downstream signaling. EMBO Rep 2016;17(12):1766–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Xia H, Luo H, Shan C, Muruato AE, Nunes BTD, Medeiros DBA, et al. An evolutionary NS1 mutation enhances Zika virus evasion of host interferon induction. Nat Commun 2018;9(1):414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wu Y, Liu Q, Zhou J, Xie W, Chen C, Wang Z, et al. Zika virus evades interferon-mediated antiviral response through the co-operation of multiple nonstructural proteins in vitro. Cell Discov 2017;3:17006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Glasner A, Oiknine-Djian E, Weisblum Y, Diab M, Panet A, Wolf DG, et al. Zika Virus Escapes NK Cell Detection by Upregulating Major Histocompatibility Complex Class I Molecules. Journal of virology 2017;91(22). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lobigs M, Mullbacher A, Regner M. MHC class I up-regulation by flaviviruses: Immune interaction with unknown advantage to host or pathogen. Immunol Cell Biol 2003;81(3):217–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Avirutnan P, Mehlhop E, Diamond MS. Complement and its role in protection and pathogenesis of flavivirus infections. Vaccine 2008;26:I100–I7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Muller DA, Young PR. The flavivirus NS1 protein: molecular and structural biology, immunology, role in pathogenesis and application as a diagnostic biomarker. Antiviral Res 2013;98(2):192–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Martines RB, Bhatnagar J, de Oliveira Ramos AM, Davi HP, Iglezias SD, Kanamura CT, et al. Pathology of congenital Zika syndrome in Brazil: a case series. Lancet 2016;388(10047):898–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Silasi M, Cardenas I, Kwon JY, Racicot K, Aldo P, Mor G. Viral infections during pregnancy. American journal of reproductive immunology (New York, NY : 1989) 2015;73(3):199–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Singer DB, Rudolph AJ, Rosenberg HS, Rawls WE, Boniuk M. Pathology of the congenital rubella syndrome. J Pediatr 1967;71(5):665–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mathur A, Tandon HO, Mathur KR, Sarkari NB, Singh UK, Chaturvedi UC. Japanese encephalitis virus infection during pregnancy. Indian J Med Res 1985;81:9–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chaturvedi UC, Mathur A, Chandra A, Das SK, Tandon HO, Singh UK. Transplacental infection with Japanese encephalitis virus. The Journal of infectious diseases 1980;141(6):712–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhang Y, Li X, Chen H, Ti J, Yang G, Zhang L, et al. Evidence of possible vertical transmission of Tembusu virus in ducks. Vet Microbiol 2015;179(3–4):149–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kim K, Shresta S. Neuroteratogenic Viruses and Lessons for Zika Virus Models. Trends Microbiol 2016;24(8):622–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Platt DJ, Smith AM, Arora N, Diamond MS, Coyne CB, Miner JJ. Zika virus-related neurotropic flaviviruses infect human placental explants and cause fetal demise in mice. Sci Transl Med 2018;10(426). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.O’Leary DR, Kuhn S, Kniss KL, Hinckley AF, Rasmussen SA, Pape WJ, et al. Birth outcomes following West Nile Virus infection of pregnant women in the United States: 2003–2004. Pediatrics 2006;117(3):e537–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Bandeira AC, Campos GS, Sardi SI, Rocha VF, Rocha GC. Neonatal encephalitis due to Chikungunya vertical transmission: First report in Brazil. IDCases 2016;5:57–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Gerardin P, Samperiz S, Ramful D, Boumahni B, Bintner M, Alessandri JL, et al. Neurocognitive outcome of children exposed to perinatal mother-to-child Chikungunya virus infection: the CHIMERE cohort study on Reunion Island. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2014;8(7):e2996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gervasi MT, Romero R, Bracalente G, Chaiworapongsa T, Erez O, Dong Z, et al. Viral invasion of the amniotic cavity (VIAC) in the midtrimester of pregnancy. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 2012;25(10):2002–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]