Abstract

The goal of this study was to examine, in a nationally representative sample, relationships between various sexual initiation patterns, subsequent sexual partnerships, and related health outcomes from adolescence through early adulthood. Data were from a subset of 6,587 respondents from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health. Bivariate analyses and adjusted logistic and ordinary least squares regression models were used to determine associations between membership in three sexual initiation classes, lifetime sexual partner counts, and multiple health outcomes, including lifetime sexually transmitted infection or disease (STI/STD) diagnosis, lifetime unintended pregnancy, and romantic relationship quality. Broadly, having fewer lifetime sexual partners was associated with lower odds rates of STI/STD diagnosis and unintended pregnancy, and better relationship quality; however, findings also indicated both within and between sexual initiation class differences in the relationship between lifetime sexual partners and all three health outcomes. In particular, results showed little variation in health outcomes by sexual partnering among those who postponed sexual activity, but members of the class characterized by early and atypical sexual initiation patterns who had fewer lifetime partners exhibited better health outcomes than most other initiation groups. These results show that while both sexual initiation and partnering patterns add important information for understanding sexual health from adolescence to early adulthood, partnering may be more relevant to these sexual health outcomes. Findings indicate a need for more comprehensive sexual education focused on sexual risk reduction and promotion of relationship skills among adolescents and adults.

Keywords: Sexual initiation, sexual partnering, sexual health, Add Health, adolescence, early adulthood

INTRODUCTION

Although normative, adolescent and young adult sexual activity has inherent risks. Adolescents and emerging adults aged 15–24 represent only 25% of the sexually active population in the United States, but account for almost half of the 20 million new sexually transmitted infections or diseases (STI/STD) diagnosed each year (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2016). In addition, unintended pregnancy rates among 15–24 year olds are approximately twice that of older women (Finer & Zolna, 2011; Mosher, Jones, & Abma, 2012). Such statistics have driven policies that promote sexual education programs focused on abstinence only until marriage, assuming that delaying sexual intercourse is the only way to avoid negative sexual health outcomes and to improve marital relationship quality. However, these policies ignore the fact that the majority of the U.S. population engages in premarital sex as youth (Halpern & Haydon, 2012; Lerner & Hawkins, 2016; Santelli et al., 2017; The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, 2017).

Research has shown that early timing of first sex is associated with a greater number of recent and lifetime partners, increased risk of both STI/STDs and unintended pregnancy, and variations in romantic relationship quality outcomes (e.g., commitment, intimacy, emotional support) in adulthood (Harden, 2012; Heywood, Patrick, Smith, & Pitts, 2015; O’Donnell et al., 2001; Sandfort, Orr, Hirsch, & Santelli, 2008; Sassler, Addo, & Lichter, 2012; Upchurch, Mason, Kusunoki, & Kriechbaum, 2004; Vasilenko, Kugler, & Rice, 2016). However, the majority of this research has focused only on vaginal sex initiation, neglecting to consider whether other types of sexual behavior, including oral-genital and anal sex, and the sequence and spacing of such behaviors, have implications for later health outcomes. One recent study by Reese et al. (2013) showed that those adolescents who initiated sexual behavior with oral-genital sex and delayed at least one year before vaginal sex, and those who initiated two behaviors within the same year, had lower odds of adolescent pregnancy compared to those who initiated with vaginal sex first, controlling for “exposure” time. Such research suggests the importance of expanding our consideration of sexual initiation to include the timing, sequence, and spacing of various behaviors when considering the health implications of sexual activity over the life course.

Recognizing this gap in the literature, researchers have begun to use latent class analyses (LCA) to capture multiple dimensions of adolescent sexuality. LCA represent a person-centered approach that is well-suited to simultaneously consider multiple facets of adolescent sexual behavior rather than focusing on one behavior in isolation. Within the adolescent sexuality literature, there has been considerable consistency in the classes that have emerged from LCA studies, including those characterized by normative timing and sequencing, postponement, and early initiation of sexual behaviors (Haydon, Herring, Prinstein, & Halpern, 2012b; Hipwell, Stepp, Keenan, Chung, & Loeber, 2011; Vasilenko, Kugler, Butera, & Lanza, 2015; Wesche, Lefkowitz, & Vasilenko, 2017). In one such LCA study, Haydon et al. (2012) derived five latent initiation classes from information regarding lifetime sexual behavior from the Wave IV (young adult) interview of the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health; Harris et al., 2009). Behaviors included were the first type of sexual behavior in which the respondent had ever engaged, the timing of first sexual experience, the number of types of sex in which the respondent had ever engaged, the spacing between the first and second sexual behaviors, and whether the respondent had engaged in anal sex prior to age 18. Five classes were identified, which were labeled Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors, Dual Initiators, Vaginal Initiators/Single Behavior, Postponers, and Early/Atypical Initiators. These classes accounted for 80% of the variance in the Add Health sample (Haydon et al., 2012b). The present study will focus on three of Haydon et al.’s latent classes, which represent the groups that often drive sexuality education discussions in the United States (Santelli et al., 2017; Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the sexual initiation classes for the current analysis

| Class | Proportion of Analytic Sample |

Age of Initiation (mean) |

First Behavior | Spacing (years) |

Total Behaviors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaginal Initiator/Multiple Behaviors | 81.6 | 15.7 | Vaginal | 1+ | 2 |

| Postponers | 9.4 | 22.0 | Vaginal, oral in same year | 0 | 2 |

| Early/Atypical Initiators* | 9.0 | 15.1 | 2+ behaviors in same year | 0 | 3 |

Notes: All Early/Atypical Initiators engaged in anal sex before age 18

Subsequent research using Haydon et al.’s (2012b) sexual initiation classes has documented both similarities and differences in sexual health outcomes and risk behavior across classes. For example, Haydon et al. found no significant differences in STI/STD diagnosis, having concurrent sexual partners, and exchanging sex for money among those who had initiated vaginal sex first and reported other sexual behaviors within two years (Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors; 49.0% of sample; mean age of initiation = 15.7) and those who initiated oral and vaginal sex in the same year (Dual Initiators; 32.0% of sample; mean age of initiation = 16.5). However, differences did emerge for the other three classes. Those who postponed sexual activity for an extended period (Postponers; 5.7% of sample; mean age of initiation = 21.7) had lower odds of all three health outcomes and those who only engaged in vaginal sex (Vaginal Initiators/Single Behavior; 7.6% of sample; mean age of initiation = 17.8) had lower odds of STI/STD diagnosis and concurrent partnerships compared to those in the modal, Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class. Finally, members of the class characterized by early sexual activity and early anal sex (Early/Atypical Initiators; 5.7% of sample; mean age of initiation = 15.0) showed elevated odds of concurrent partnerships compared to the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors group, but, perhaps surprisingly, did not show elevated odds of STI/STD diagnosis or exchanging sex for money. These findings show that the pattern of sexual initiation can, but does not necessarily, inform sexual health outcomes in early adulthood. Rather, they suggest that variation in the associations between patterns of sexual initiation and subsequent sexual behavior (e.g., sexual partnering), may have different implications for later sexual health, thus motivating the analyses in the current study (Haydon, Herring, & Halpern, 2012a).

The linkages between sexual initiation and subsequent sexual partnering, and their combined implications for sexual health, are not well understood because the majority of past research has focused on these two variables as independent predictors of sexual health outcomes (Ashenhurst, Wilhite, Harden, & Fromme, 2017; Harden, 2012; Kaestle, Halpern, Miller, & Ford, 2005). The studies that do consider both sexual initiation and partnering generally focus on the relationship between them, and do not go on to consider whether the particular combinations of sexual initiation and partnering patterns are differentially associated with later health (Harden, 2012; Lanza, Kugler, & Mathur, 2011; Moilanen, Crockett, Raffaelli, & Jones, 2010). This study builds on prior research by examining, in a nationally representative sample, whether associations between adolescent sexual initiation patterns and sexual health outcomes in adulthood vary, depending on the partnering behavior patterns that individuals with a given initiation pattern experience. Outcomes examined are lifetime STI/STD diagnosis, lifetime unintended pregnancy, and romantic relationship quality in early adulthood.

As has been noted (e.g., Heywood et al., 2015), much of the literature examining the implications of sexual initiation timing has been atheoretical, as there are limited theoretical options, some of which do not focus on sexual development per se. Our investigation was generally informed by Life Course Theory, and its postulation that the timing and sequence of experiences (i.e., sexual experiences) matter (Elder & Shanahan, 2006). Our work was further informed by the complementary concepts of equifinality and multifinality, which are drawn from General Systems Theory (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996; von Bertalanffy, 1968). Although originally applied to developmental psychopathology, this framework has been applied to sexual health (Jurich & Myers-Bowman, 1998; Mitchell et al., 2004). Equifinality suggests that the same outcome can result from multiple starting points, while multifinality posits that there can be multiple outcomes from the same starting point. In both concepts, the outcome is dependent on intermediary factors. In the present context, equifinality would suggest that different sexual initiation patterns may lead to similar sexual health outcomes, depending on subsequent behavior and experiences. Conversely, multifinality reflects the circumstance of one initiation pattern resulting in different health outcomes.

Beyond these meta-theoretical constructs, we look to Problem Behavior Theory to inform our hypotheses linking initiation class and indicators of sexual health (Jessor & Jessor, 1977). In doing so, we do not argue that sexual behavior is necessarily problematic, but that like behaviors such as substance use and violence, which clearly do pose health risks, sexual behavior is associated with psychosocial conventionality (Donovan, Jessor, & Costa, 1991). Sexual activity at early ages and with multiple partners is seen as unconventional due to perceived immaturity and beliefs regarding sex before marriage (Donovan et al., 1991; Halpern, 2010). In fact, prior research has shown that initiation class membership is associated with psychosocial conventionality (Haydon et al., 2012b; Reese, Choukas-Bradley, Herring, & Halpern, 2014). However, variation in behavior more proximal to our outcomes, such as partner counts, could modify the link between conventional/unconventional initiation patterns and later outcomes.

We therefore hypothesized that the link between initiation class membership and subsequent health depends on the number of sexual partners one has, such that having more sexual partners will be associated with worse health outcomes, but that this relationship will be stronger among those who initiate sexual activity earlier. That is, it is not just sexual initiation pattern or just more proximal partnering, but rather the combination of these behavioral sets that determine later sexual health.

METHOD

Sample

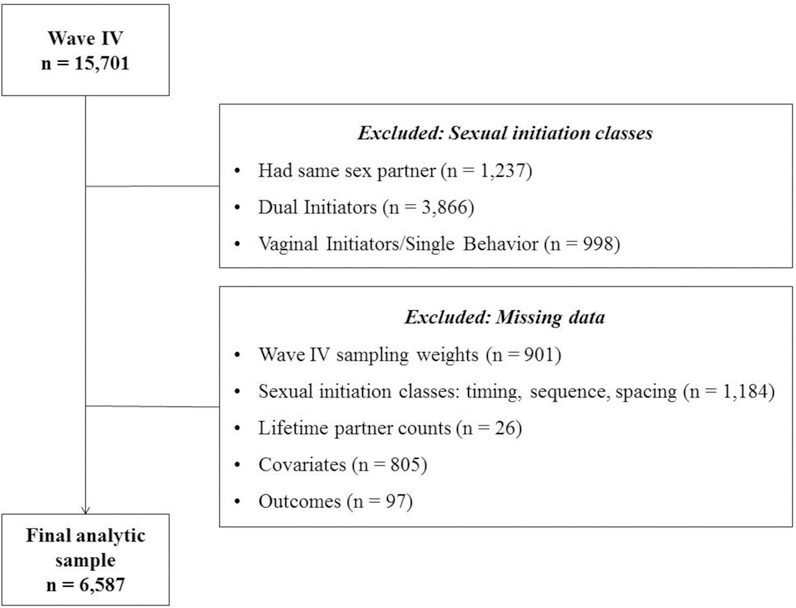

We used data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health), a nationally representative sample of more than 20,745 adolescents in 7th-12th grade during the 1994–1995 school year (Wave I). The Add Health study used a complex, school-based sampling design which has been described elsewhere (Harris et al., 2009). Four waves of in-home data have been collected with the original Add Health sample, which have provided information regarding the health and well-being of a cohort of adolescents well into their adult years. Wave II was completed in 1995–1996 (n = 14,738, ages 12–18; response rate = 88.2%), Wave III was completed in 2001–2002 (n = 15,197, ages 18–26; response rate = 77.4%), and Wave IV was completed in 2008–2009 (n = 15,701, ages 26–32; response rate = 80.3%; Harris, Udry, & Bearman, 2013). We focused on three of Haydon et al.’s (2012b) five initiation classes derived from these data, comparing two distinct classes, and in some sense polar opposites, to the large modal class, and restricted our final analytic sample to the subset of respondents in these three classes who had complete data on all variables of interest (n = 6,587; see Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Exclusion criteria for the analytic sample

Measures

The literature often conceptualizes adolescent sexual activity as a problem behavior; however, more recent research has also considered the positive consequences of sexual activity in this population (Tolman & McClelland, 2011). We therefore chose to focus on both negative (i.e., STI/STD diagnosis, unintended pregnancy) and positive (i.e., romantic relationship quality) health outcomes for this study.

Outcomes: STI/STD diagnosis

The STI/STD variable is a dichotomous self-report about lifetime history of STI/STD diagnosis as of Wave IV. Since some of the STI/STDs queried were biologically sex-specific, we only included those infections or diseases that can affect both sexes and were not caused by other STI/STDs: chlamydia, gonorrhea, trichomoniasis, syphilis, genital herpes, genital warts, hepatitis B, human papilloma virus, or HIV/AIDS.

Unintended pregnancy

The Wave IV interview included a complete pregnancy history. For every pregnancy, respondents were asked, “Thinking back to the time just before this pregnancy with [fill initials], did you want to have a child then?” If the respondent indicated “no” for any reported pregnancy, the respondent was coded as having had an unintended pregnancy (1). If none of the pregnancies was unintended or if the respondent had never been pregnant, the respondent was coded as never having an unintended pregnancy (0).

Romantic relationship quality

The romantic relationship quality variable was the average score of five items from the Supporting Healthy Marriage baseline instrument (Hsueh & Knox, 2014). Respondents received these questions if they reported at least one past or present romantic relationship at Wave IV. Respondents indicated how much they agreed or disagreed with the following five relationship quality items within their current or most recent relationship using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree; α = 0.87):

We (enjoy/enjoyed) doing even ordinary, day-to-day things together;

I (am/was) satisfied with the way we handle our problems and disagreements;

My partner (listens/listened) to me when I need someone to talk to;

My partner (expresses/expressed) love and affection to me;

I (trust/trusted) my partner to be faithful to me.

Main Predictors: Adolescent sexual initiation patterns

We used the class assignments created by Haydon et al. (2012b) as our measure of adolescent sexual initiation patterns. As mentioned previously, five latent classes were derived from sexual behavior variables constructed from the Wave IV questionnaire, including: timing of first sexual experience, first type of sexual behavior, number of sexual behaviors in which the respondent had ever engaged, spacing (in years) from the first to the second sexual behavior, and whether the respondent had engaged in anal sex prior to age 18. Since respondents reported ages for each sexual behavior in whole years, the exact sequence and time between behaviors could not always be determined. For this reason, first behavior was coded as vaginal sex first, oral sex first, vaginal and oral sex at the same age, or anal sex and any other behavior at the same age, and spacing of the first two behaviors was coded as within the same year, one, two, 3–5, six or more years apart, or that the respondent had only engaged in one type of sexual behavior. Since initiation patterns differ among sexual minority respondents (Goldberg & Halpern, 2017), these sexual initiation classes only included those who did not report any same-sex partnerships. More in depth descriptions of all five of the latent classes is available elsewhere (Haydon et al.,2012b).

Based on the concept of conventionality/unconventionality in Problem Behavior Theory, we compared only those respondents who were members of classes on the distinct ends of the distribution (Postponers and Early/Atypical Initiators) to those who were in the modal class (Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors; Donovan, Jessor, & Costa, 1991; Jessor & Jessor, 1977). Table 1 provides detail about the characteristics of each class for the current analysis. Members of the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors (49% of the full Add Health sample; 81.6% of the current analytic sample) class had a mean age of first sex of approximately 16 years, and were more likely to initiate vaginal sex first followed by another behavior (typically oral-genital sex) at least one year later. Members of the Postponers class (5.7% of the full Add Health sample; 9.4% of the analytic sample) had a mean age of first sex of approximately 22 years old, and the majority initiated both vaginal and oral-genital intercourse in the same year. Members of the Early/Atypical Initiators class (5.7% of the full Add Health sample; 9.0% of the analytic sample) initiated sexual activity earlier (15 years old), engaged in two or more behaviors within the same year, and all members reported having anal sex before the age of 18.

Lifetime number of sexual partners

At Wave IV, respondents were asked to report numbers of male and female sexual partners with whom they had ever engaged in any type of sexual activity, which was part of a larger section focused on experiences of vaginal, oral, and anal sex. These responses were used to construct a continuous lifetime partner count variable for each respondent. Given the skew of the distribution and overall improvement in model fit, we used these partner counts to create a categorical variable with three levels based on quartiles, with the top two quartiles combined due to small samples sizes among the Postponers: 1–3, 4–7, and ≥8 partners.

Demographic characteristics

Biological sex was measured at Wave IV. Respondent age at the time of the Wave IV interview was calculated by subtracting the birth date from the interview date. Race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, or Non-Hispanic Other) and family structure (two biological parents, other two-parent family, single parent family, or other family structure) were self-reported at Wave I. The highest level of education of either parent at Wave I was used as a proxy for adolescent socioeconomic status (SES; less than high school [HS], HS diploma/General Educational Development [GED], some college/vocational school, or college graduate).

Other covariates

Consistent with postulates of Problem Behavior Theory and other research on adolescent sexual activity, we selected the following covariates for all analyses (Halpern, Waller, Spriggs,& Hallfors, 2006; Haydon et al., 2012a; Jessor & Jessor, 1977; Reese et al., 2014). All covariates were measured at Wave I unless specified otherwise.

Religiosity was measured using the sum of responses to items regarding the importance of religion, prayer frequency, and attendance at religious services (range: 3–17, α = 0.95). Grade point average was used as a proxy for academic achievement, and was measured using self-reported letter grades in English/language arts, social science/history, mathematics, and science classes during the most recent grading period. Letter grades were then converted to a standard numeric scale (A = 4, B = 3, C = 2, D or lower = 1) and averaged across academic subjects. Our measure of perceived parental attitudes towards sex was the average of respondent reports of both mother’s and father’s (or one parent’s report for single parent households) attitudes towards the respondent having sex and having sex with a steady partner, with higher scores indicating greater disapproval of the respondent’s sexual activity (range, 1–5; α = 0.95). Substance use was a summary measure of both the severity and variety of recent substance use based on self-report. Specifically, respondents received one point if they used a cigarette or tobacco in the last 30 days; two points if they used marijuana in the last 30 days or alcohol in the last 12 months; and three points if they used hard drugs (e.g., cocaine, inhalants, illegal injectable drugs) in the last 30 days (range, 0–8). Finally, based on previous work with the Add Health sample, the parent adolescent relationship quality variable was a summary measure of four questions regarding the respondent’s perceptions of closeness, communication satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, and warmth with each resident parent (range, 1–5; α = 0.95; Resnick et al., 1997). When both parents were present, the higher of the two scores was selected.

We also controlled for experiences of sexual abuse, forced sex, and coerced sex measured at Wave IV, as all have been associated with sexual risk behavior and STI/STD risk (Fergusson, Horwood, & Lynskey, 1997; Noll, Trickett, & Putnam, 2003; Smith & Ford, 2010; Stockman, Campbell, & Celentano, 2010; Wilson & Widom, 2009). A dichotomous measure of sexual abuse (yes, no) by a parent/caregiver was measured using items from the Wave IV interview regarding sexual abuse before age 18. Lifetime experiences of non-parental forced and coerced sex were dichotomous measures (yes, no) derived from items in the Wave IV interview. In romantic relationship quality analyses, we also adjusted for selected characteristics of the described romantic relationship at Wave IV. These were a categorical variable of relationship type (married [ref], cohabiting, pregnancy partner, currently dating, or recently dating), a dichotomous variable indicating whether the relationship was current (yes, no), and a categorical measure of relationship duration based on the quartiles of the distribution (0–15 months, 15 months-4 years, 4–8 years [ref], >8 years).

Finally, we controlled for years sexually active, which was calculated by subtracting the respondent’s age at first sexual experience from the respondent’s age at the time of the Wave IV interview.

Analysis

First, sample characteristics were assessed using frequencies, weighted percentages, means, and standard errors. Next, to determine associations between sexual initiation classes, lifetime sexual partner counts, and each health outcome, we used adjusted logistic regression models for the dichotomous outcomes (i.e., lifetime STI/STD diagnosis, lifetime unintended pregnancy) and adjusted ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models for romantic relationship quality outcome. Both logistic regressions were adjusted for years sexually active at the Wave IV interview to account for differences in exposure time. We first completed a set of two models per outcome that were stratified by sexual initiation class to understand within-class patterns. The first of the two models examined the relationship with sexual partnering as the only predictor; the second model represented the full model with numbers of sexual partners and all other covariates. For all stratified analyses, the 4–7 partners group represented the referent group because this group included the median number. Finally, we repeated our analyses with an interaction between sexual initiation class and sexual partner counts to better understand whether the implications of initiation patterns vary depending on the number of partners. The first model included only the interaction between sexual initiation and partner counts, or initiation-partnering groups, and the second was the full model with the initiation-partnering groups and all other covariates. For this set of regression analyses, the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class with 4–7 lifetime partners was the referent because this represented the modal group. All analyses used sampling weights and adjusted variance estimates for the Add Health complex survey design, and were completed using Stata version 14.1 (StataCorp, 2015).

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

Table 2 shows descriptive statistics for demographic characteristics, sexual partner counts, sexual health outcomes, and all other covariates for the full analytic sample and by sexual initiation class. The analysis sample comprised slightly more females than males (52.1%vs. 47.9%), and the average age of respondents was 28.2 years. The majority of respondents (65.7%) identified as non-Hispanic White, with an additional 11.7% identifying as Hispanic, 16.7% as non-Hispanic Black, and 5.9% as another non-Hispanic race. Over 62% of parents had attended some college or had at least a college degree, and almost 60% of respondents lived with two biological parents during adolescence.

Table 2.

Bivariate statistics of the analytic sample for all variables and controls by sexual initiation class

| Vaginal Initiators/ Multiple Behaviors |

Postponers | Early/Atypical Initiators |

Total | F(df) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 5,396; 81.6%) | (n = 650; 9.4%) | (n = 541; 9.0%) | (N = 6,587) | ||

| Frequencies, n (%) | |||||

| Biological Sex | F(1.9, 243.9) = 26.1** | ||||

| Male | 2,253 (45.3) | 330 (55.0) | 330 (64.7) | 2,913 (47.9) | |

| Female | 3,143 (54.7) | 320 (45.0) | 211 (35.3) | 3,674 (52.1) | |

| Race† | F(5.7, 724.8) = 12.1** | ||||

| Hispanic | 823 (11.2) | 97 (13.9) | 109 (13.9) | 1,029 (11.7) | |

| NH Black | 1,441 (19.1) | 63 (6.7) | 50 (4.7) | 1,554 (16.7) | |

| NH Other | 354 (5.3) | 107 (10.8) | 55 (6.5) | 516 (5.9) | |

| NH White | 2,778 (64.3) | 383 (68.5) | 327 (74.8) | 3,488 (65.7) | |

| Parent Education (SES)† | F(5.4, 689.6) = 3.3** | ||||

| <HS | 609 (10.4) | 67 (10.5) | 65 (11.1) | 741 (10.5) | |

| HS/GED | 1,375 (27.2) | 121 (20.3) | 157 (32.8) | 1,653 (27.0) | |

| Some College | 1,636 (30.9) | 169 (27.4) | 162 (28.1) | 1,967 (30.3) | |

| College Grad | 1,776 (31.5) | 293 (41.8) | 157 (27.9) | 2,226 (32.2) | |

| Family Structure | F(5.6, 722.5) = 5.6** | ||||

| Two biological parents | 2,912 (56.3) | 473 (73.4) | 306 (61.1) | 3,691 (58.4) | |

| Other two parent family | 1,027 (18.2) | 75 (9.8) | 114 (17.5) | 1,216 (17.4) | |

| Single parent | 1,251 (21.8) | 91 (14.6) | 110 (18.2) | 1,452 (20.8) | |

| Other | 206 (3.6) | 11 (2.2) | 11 (3.2) | 228 (3.5) | |

| Coerced Sex | F(2.0, 255.0) = 11.8** | ||||

| No | 4,707 (87.0) | 615 (95.0) | 456 (82.6) | 5,778 (87.3) | |

| Yes | 689 (13.0) | 35 (5.0) | 85 (17.4) | 809 (12.7) | |

| Forced Sex | F(1.9, 248.9) = 6.2** | ||||

| No | 4,964 (91.9) | 631 (97.4) | 488 (89.5) | 6,083 (92.2) | |

| Yes | 432 (8.1) | 19 (2.6) | 53 (10.5) | 504 (7.8) | |

| Sexual Abuse | F(1.96, 250.54) = 0.64 | ||||

| No | 5,140 (95.4) | 629 (96.8) | 518 (95.3) | 6,287 (95.5) | |

| Yes | 256 (4.6) | 21 (3.2) | 23 (4.7) | 300 (4.5) | |

| Lifetime Number of Sexual Partners | F(3.8, 488.0) = 124.4** | ||||

| 1–3 | 1,092 (19.2) | 446 (69.4) | 88 (14.9) | 1,626 (23.5) | |

| 4–7 | 1,604 (29.7) | 128 (20.8) | 137 (23.4) | 1,869 (28.3) | |

| ≥8 | 2,700 (51.1) | 76 (9.8) | 316 (61.7) | 3,092 (48.2) | |

| Lifetime STI/STD Diagnosis | F(1.9, 245.8) = 31.9** | ||||

| No | 3,934 (74.5) | 598 (93.0) | 418 (78.0) | 4,950 (76.6) | |

| Yes | 1,462 (25.5) | 52 (7.0) | 123 (22.0) | 1,637 (23.4) | |

| Lifetime Unintended Pregnancy | F(2.0, 253.8) = 39.6** | ||||

| No | 3,238 (61.4) | 553 (84.6) | 338 (64.3) | 4,129 (63.8) | |

| Yes | 2,158 (38.6) | 97 (15.4) | 203 (35.7) | 2,458 (36.2) | |

| Relationship Type | F(7.1, 907.7) = 2.8** | ||||

| Married | 2,539 (47.8) | 334 (53.6) | 272 (48.4) | 3,145 (48.4) | |

| Cohabiting | 1,443 (27.1) | 112 (19.6) | 137 (26.6) | 1,692 (26.3) | |

| Pregnancy | 160 (2.3) | 10 (0.3) | 11 (1.3) | 181 (2.1) | |

| Currently dating | 863 (15.6) | 111 (15.6) | 84 (17.4) | 1,058 (15.8) | |

| Recently dating | 391 (7.2) | 83 (10.8) | 37 (6.3) | 511 (7.4) | |

| Relationship Duration | F(5.6, 712.0) = 4.5** | ||||

| 0–15 months | 1,163 (21.6) | 166 (25.1) | 129 (25.6) | 1,458 (22.3) | |

| 15 months-4 years | 1,303 (24.2) | 181 (28.5) | 120 (22.8) | 1,604 (24.5) | |

| 4–8 years | 1,533 (28.8) | 217 (32.4) | 120 (23.0) | 1,870 (28.6) | |

| >8 years | 1,397 (25.4) | 86 (14.0) | 172 (28.6) | 1,655 (24.6) | |

| Current Relationship | F(1.9, 247.8) = 1.1 | ||||

| No | 948 (17.6) | 136 (18.9) | 91 (14.3) | 1175 (17.5) | |

| Yes | 4448 (82.4) | 514 (81.1) | 450 (85.7) | 5412 (82.5) | |

| Means (SE) | |||||

| Age (range, 28–34) | 28.2 (0.12) | 28.5 (0.13) | 28.0 (0.19) | 28.2 (0.12) | F(2, 127) = 8.9** |

| Years sexually active | 13.4 (0.13) | 7.6 (0.24) | 13.9 (0.21) | 12.9 (0.12) | F(2, 127) = 344.0** |

| Religiosity (range, 3–17)† | 11.3 (0.16) | 12.3 (0.27) | 10.7 (0.24) | 11.3 (0.14) | F(2, 127) = 11.8** |

| Grade point average (range, 1–4)† | 2.8 (0.02) | 3.1 (0.04) | 2.8 (0.04) | 2.8 (0.02) | F(2, 127) = 23.5** |

| Perceived parent attitude toward sex (range, 1–5)† | 4.2 (0.03) | 4.5 (0.04) | 4.1 (0.06) | 4.2 (0.03) | F(2, 127) = 25.6** |

| Substance use (range, 0–8)† | 1.7 (0.07) | 0.7 (0.08) | 1.8 (0.14) | 1.6 (0.07) | F(2, 127) = 61.5** |

| Parent relationship quality (range, 4–20)† | 17.7 (0.06) | 18.3 (0.11) | 17.8 (0.14) | 17.8 (0.06) | F(2, 127) = 10.7** |

| Romantic relationship quality (range, 1–5) | 4.2 (0.02) | 4.3 (0.04) | 4.2 (0.05) | 4.2 (0.02) | F(2, 127) = 6.5** |

Notes: Percentages and means are weighted to yield national probability estimates; Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding; NH = Non-Hispanic; SES = socioeconomic status; HS = high school; GED = General Educational Development; STI/STD = sexually transmitted infection/disease; F-statistics indicate differences across sexual initiation classes;

p<0.05;

p<0.01;

Measured at Wave I

In bivariate comparisons, classes differed on all included variables except for experiences of sexual abuse and relationship currency. More specifically, there were significantly more males than females in the Early/Atypical Initiators class (64.7% vs. 35.3%). Also, a greater proportion of the Postponers class had three or fewer lifetime partners (69.4%) compared to the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class (19.2%) and the Early/Atypical Initiators class (14.9%), while a greater proportion of the Early/Atypical Initiators had ≥8 lifetime partners (61.7%) compared to the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors (51.1%) and Postponers (9.8%). However, a portion of each class (10% or typically more) fell into each of the partner count categories, confirming variation in subsequent partnering within each initiation class. Regarding health outcomes, overall, 23.4% of the sample had a lifetime STI/STD diagnosis and 36.2% had experienced an unintended pregnancy, though proportionally fewer of the Postponers reported these outcomes (7.0% and 15.4%, respectively). The mean romantic relationship quality was 4.2 out of a possible 5, with only the Postponers reporting a slightly higher mean score (4.3).

Stratified Regression Models

First, we examined associations between partner counts and health outcomes within each sexual initiation class.

Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors

Table 3 shows the results for the stepwise regression models for each outcome among the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class. For the STI/STD diagnosis outcome, results showed that those with 1–3 partners had significantly lower odds and those with ≥8 partners had significantly higher odds of a lifetime STI/STD compared to the odds of those with 4–7 partners. Similar to findings for STI/STDs, those with 1–3 partners had significantly lower odds and those with ≥8 partners had significantly higher odds of unintended pregnancy compared to the odds of Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class members with 4–7 partners. For romantic relationship quality, those with 1–3 partners had significantly better and those with ≥8 partners had significantly worse romantic relationship quality compared to Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors members with 4–7 partners.

Table 3.

Coefficients (and 95% confidence intervals) from adjusted regression analyses examining sexual health outcomes among Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class members

| Vaginal Initiators/ Multiple Behaviors |

Lifetime STI/STD diagnosis aOR (95% CI) |

Lifetime unintended pregnancy aOR (95% CI) |

Romantic relationship quality β (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partners Only | Full Model | Partners Only | Full Model | Partners Only | Full Model | |

| Lifetime Number of Partners (4–7) | ||||||

| 1–3 | 0.56 (0.39, 0.78)** | 0.61 (0.42, 0.87)** | 0.68 (0.54, 0.85)** | 0.75 (0.59, 0.96)* | 0.22 (0.15, 0.29)** | 0.14 (0.07, 0.21)** |

| ≥8 | 2.08 (1.65, 2.62)** | 2.68 (2.11, 3.40)** | 1.33 (1.12, 1.58)** | 1.43 (1.19, 1.73)** | −0.14 (−0.20, −0.07)** | −0.10 (−0.15, −0.04)** |

| Biological Sex (Male) | ||||||

| Female | 3.83 (3.06, 4.79)** | 1.96 (1.64, 2.34)** | −0.03 (−0.08, 0.03) | |||

| Race (NH White) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1.47 (1.08, 1.99)* | 1.35 (0.99, 1.83)+ | −0.14 (−0.22, −0.05)** | |||

| NH Black | 3.24 (2.53, 4.15)** | 2.00 (1.56, 2.58)** | −0.18 (−0.26, −0.10)** | |||

| NH Other | 1.33 (0.83, 2.12) | 1.26 (0.88, 1.80) | −0.08 (−0.20, 0.04) | |||

| Parent Education (SES; College Grad) | ||||||

| <HS | 0.71 (0.48, 1.04)+ | 1.40 (1.01, 1.93)* | −0.12 (−0.21, −0.02)* | |||

| HS/GED | 0.78 (0.59, 1.02)+ | 1.64 (1.29, 2.07)** | −0.10 (−0.17, −0.03)** | |||

| Some College | 0.85 (0.66, 1.11) | 1.38 (1.14, 1.66)** | −0.10 (−0.16, −0.04)** | |||

| Family Structure (Two biological parents) | ||||||

| Other two parent family | 0.91 (0.66, 1.25) | 1.07 (0.85, 1.35) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.06) | |||

| Single parent | 1.04 (0.80, 1.34) | 1.22 (0.98, 1.51)+ | −0.05 (−0.11, 0.02) | |||

| Other | 1.07 (0.67, 1.72) | 1.66 (0.97, 2.84)+ | −0.11 (−0.27, 0.05) | |||

| Coerced Sex (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.21 (0.90, 1.61) | 1.48 (1.12, 1.95)** | −0.12 (−0.21, −0.02)* | |||

| Forced Sex (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.45 (1.01, 2.07)* | 1.00 (0.71, 1.43) | −0.04 (−0.16, 0.09) | |||

| Sexual Abuse (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.98 (0.70, 1.38) | 1.05 (0.71, 1.54) | −0.05 (−0.17, 0.08) | |||

| Years sexually active† | − | − | 0.01 (−0.00, 0.03)+ | |||

| Age | 0.89 (0.84, 0.94)** | 0.93 (0.89, 0.98)** | −0.02 (−0.04, 0.00)+ | |||

| Religiosity | 1.00 (0.98, 1.02) | 1.00 (0.98, 1.03) | 0.01 (−0.00, 0.01)+ | |||

| Grade point average | 0.99 (0.86, 1.14) | 0.73 (0.64, 0.84)** | 0.07 (0.04, 0.11)** | |||

| Parents’ attitudes toward sex | 0.85 (0.76, 0.96)** | 0.96 (0.87, 1.05) | 0.01 (−0.03, 0.05) | |||

| Substance use | 1.01 (0.96, 1.07) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.01) | |||

| Parent relationship quality | 0.97 (0.93, 1.00)+ | 0.94 (0.92, 0.97)** | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04)** | |||

| Relationship Type (Married) | ||||||

| Cohabiting | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.07) | |||||

| Pregnancy | −0.10 (−0.31, 0.10) | |||||

| Currently dating | −0.20 (−0.29, −0.11)** | |||||

| Recently dating | −0.18 (−0.33, −0.02)* | |||||

| Current Relationship (Yes) | ||||||

| No | −0.69 (−0.80, −0.59)** | |||||

| Relationship Duration (4–8 years) | ||||||

| 0–15 months | 0.08 (−0.01, 0.18)+ | |||||

| 15 months-4 years | 0.16 (0.08, 0.24)** | |||||

| >8 years | −0.04 (−0.13, 0.04) | |||||

| R2 | 0.03** | 0.20** | ||||

| Constant | 4.19 (4.13, 4.24)** | 4.02 (3.44, 4.60)** | ||||

Notes: Referent groups for categorical variables are in parentheses next to the variable names; STI/STD = sexually transmitted infection/disease; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; NH = Non-Hispanic; SES = socioeconomic status; HS = high school; GED = General Educational Development;

p <.10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

Lifetime STI/STD diagnosis and lifetime unintended pregnancy analyses are adjusted for years sexually active at the time of the Wave IV interview to account for differences in exposure time

Postponers

Table 4 shows the results of stepwise regression models for each outcome among members of the Postponers class. Overall, there were no significant differences in the odds of STI/STD diagnosis nor in the odds for unintended pregnancy among Postponers with 1–3 or ≥8 partners compared to the odds of those with 4–7 partners. There also were no significant within class differences in romantic relationship quality due to numbers of lifetime sexual partners.

Table 4.

Coefficients (and 95% confidence intervals) from adjusted regression analyses examining sexual health outcomes among Postponers class members

| Postponers | Lifetime STI/STD diagnosis aOR (95% CI) |

Lifetime unintended pregnancy aOR (95% CI) |

Romantic relationship quality β (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partners Only | Full Model | Partners Only | Full Model | Partners Only | Full Model | |

| Lifetime Number of Partners (4–7) | ||||||

| 1–3 | 0.75 (0.28, 2.00) | 0.97 (0.27, 3.49) | 1.24 (0.53, 2.89) | 1.31 (0.57, 3.03) | 0.20 (0.02, 0.38)* | 0.00 (−0.17, 0.17) |

| ≥8 | 1.56 (0.50, 4.88) | 2.17 (0.52, 9.01) | 1.89 (0.66, 5.44) | 2.04 (0.67, 6.26) | −0.19 (−0.49, 0.12) | −0.12 (−0.38, 0.15) |

| Biological Sex (Male) | ||||||

| Female | 4.96 (2.15, 11.41)** | 1.45 (0.76, 2.76) | −0.07 (−0.21, 0.07) | |||

| Race (NH White) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1.89 (0.43, 8.43) | 2.01 (0.82, 4.90) | −0.21 (−0.43, 0.00)+ | |||

| NH Black | 5.15 (1.85, 14.33)** | 2.60 (0.88, 7.66)+ | −0.52 (−0.82, −0.23)** | |||

| NH Other | 0.44 (0.11, 1.80) | 0.76 (0.21, 2.80) | −0.25 (−0.52, 0.01)+ | |||

| Parent Education (SES; College Grad) | ||||||

| <HS | 0.10 (0.01, 0.91)* | 1.68 (0.51, 5.49) | 0.14 (−0.11, 0.38) | |||

| HS/GED | 0.65 (0.24, 1.75) | 1.54 (0.61, 3.91) | 0.06 (−0.12, 0.25) | |||

| Some College | 0.51 (0.18, 1.49) | 1.53 (0.74, 3.17) | 0.01 (−0.13, 0.15) | |||

| Family Structure (Two biological parents) | ||||||

| Other two parent family | 2.93 (0.72, 11.89) | 0.51 (0.12, 2.09) | 0.01 (−0.20, 0.23) | |||

| Single parent | 1.57 (0.55, 4.50) | 1.17 (0.49, 2.79) | −0.01 (−0.17, 0.14) | |||

| Other | 2.46 (0.37, 16.50) | 9.00 (1.07, 75.78)* | 0.23 (−0.10, 0.55) | |||

| Coerced Sex (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 4.90 (1.12, 21.43)* | 0.98 (0.42, 2.28) | 0.04 (−0.27, 0.35) | |||

| Forced Sex (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.45 (0.16, 13.34) | 1.16 (0.17, 8.00) | −0.35 (−0.74, 0.03)+ | |||

| Sexual Abuse (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.58 (0.08, 4.04) | 0.21 (0.02, 2.38) | 0.12 (−0.10, 0.34) | |||

| Years sexually active† | - | - | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.02) | |||

| Age | 1.14 (0.88, 1.48) | 1.06 (0.84, 1.34) | −0.02 (−0.06, 0.02) | |||

| Religiosity | 0.91 (0.83, 1.01)+ | 1.10 (1.02, 1.20)* | 0.01 (−0.00, 0.02) | |||

| Grade point average | 1.40 (0.73, 2.66) | 0.90 (0.63, 1.28) | −0.01 (−0.09, 0.07) | |||

| Parents’ attitudes toward sex | 1.17 (0.57, 2.39) | 0.72 (0.50, 1.03)+ | −0.02 (−0.12, 0.08) | |||

| Substance use | 1.09 (0.66, 1.79) | 1.00 (0.77, 1.30) | −0.00 (−0.05, 0.05) | |||

| Parent relationship quality | 0.92 (0.76, 1.10) | 0.93 (0.82, 1.06) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.05)* | |||

| Relationship Type (Married) | ||||||

| Cohabiting | −0.09 (−0.26, 0.08) | |||||

| Pregnancy | −0.54 (−1.36, 0.27) | |||||

| Currently dating | −0.27 (−0.51, −0.04)* | |||||

| Recently dating | −0.41 (−0.76, −0.05)* | |||||

| Current Relationship (Yes) | ||||||

| No | −0.71 (−0.99, −0.43)** | |||||

| Relationship Duration (4–8 years) | ||||||

| 0–15 months | 0.07 (−0.14, 0.28) | |||||

| 15 months-4 years | 0.01 (−0.11, 0.14) | |||||

| >8 years | 0.05 (−0.12, 0.22) | |||||

| R2 | 0.03** | 0.36** | ||||

| Constant | 4.17 (4.01, 4.34)** | 4.69 (3.09, 6.29)** | ||||

Notes: Referent groups for categorical variables are in parentheses next to the variable names; STI/STD = sexually transmitted infection/disease; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; NH = Non-Hispanic; SES = socioeconomic status; HS = high school; GED = General Educational Development;

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

Lifetime STI/STD diagnosis and lifetime unintended pregnancy analyses are adjusted for years sexually active at the time of the Wave IV interview to account for differences in exposure time

Early/Atypical Initiators

Table 5 presents the results for stepwise regression models for each outcome among members of the Early/Atypical Initiators class. Early/Atypical Initiators with 1–3 lifetime sexual partners had significantly lower odds of lifetime STI/STD diagnosis compared to the odds of those with 4–7 partners. While those with ≥8 partners had higher odds of lifetime STI/STD diagnosis compared to the odds of those with 4–7 partners, this was only marginally significant. Similarly, Early/Atypical Initiators with 1–3 lifetime sexual partners had significantly lower odds of an unintended pregnancy compared to the odds of those with 4–7 partners. Although only marginally significant, Early/Atypical Initiators with ≥8 partners also had lower odds of unintended pregnancy compared to the odds of those with 4–7 partners. For romantic relationship quality, there were no significant within-class differences linked to numbers of sexual partners.

Table 5.

Coefficients (and 95% confidence intervals) from adjusted regression analyses examining sexual health outcomes among Early/Atypical Initiators class members

| Early/Atypical Initiators |

Lifetime STI/STD diagnosis aOR (95% CI) |

Lifetime unintended pregnancy aOR (95% CI) |

Romantic relationship quality β (95% CI) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Partners Only | Full Model | Partners Only | Full Model | Partners Only | Full Model | |

| Lifetime Number of Partners (4–7) | ||||||

| 1–3 | 0.19 (0.04, 0.96)* | 0.18 (0.04, 0.85)* | 0.35 (0.14, 0.85)* | 0.29 (0.11, 0.77)* | 0.22 (0.00, 0.45)* | 0.07 (−0.13, 0.28) |

| ≥8 | 1.37 (0.74, 2.52) | 1.73 (0.98, 3.07)+ | 0.61 (0.36, 1.01)+ | 0.59 (0.33, 1.05)+ | −0.12 (−0.33, 0.09) | −0.17 (−0.40, 0.05) |

| Biological Sex (Male) | ||||||

| Female | 2.93 (1.50, 5.72)** | 1.23 (0.71, 2.15) | −0.13 (−0.33, 0.06) | |||

| Race (NH White) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 2.71 (1.28, 5.74)** | 1.21 (0.57, 2.60) | −0.15 (−0.40, 0.10) | |||

| NH Black | 3.36 (1.15, 9.79)* | 1.37 (0.51, 3.65) | −0.30 (−0.71, 0.11) | |||

| NH Other | 1.08 (0.36, 3.20) | 3.19 (1.33, 7.63)** | −0.04 (−0.32, 0.24) | |||

| Parent Education (SES; College Grad) | ||||||

| <HS | 1.36 (0.46, 4.09) | 1.60 (0.71, 3.65) | −0.03 (−0.32, 0.26) | |||

| HS/GED | 0.72 (0.28, 1.86) | 1.14 (0.59, 2.18) | −0.21 (−0.43, 0.02)+ | |||

| Some College | 0.84 (0.40, 1.78) | 1.75 (0.95, 3.20)+ | −0.20 (−0.40, 0.01)+ | |||

| Family Structure (Two biological parents) | ||||||

| Other two parent family | 1.78 (0.77, 4.14) | 1.57 (0.75, 3.29) | −0.16 (−0.40, 0.07) | |||

| Single parent | 1.31 (0.58, 2.98) | 1.63 (0.85, 3.13) | 0.09 (−0.15, 0.34) | |||

| Other | 0.57 (0.13, 2.54) | 4.15 (0.59, 29.14) | −0.23 (−0.59, 0.13) | |||

| Coerced Sex (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.59 (0.67, 3.79) | 0.70 (0.32, 1.57) | −0.13 (−0.41, 0.16) | |||

| Forced Sex (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.80 (0.30, 2.14) | 1.94 (0.63, 5.97) | −0.03 (−0.39, 0.34) | |||

| Sexual Abuse (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.55 (0.51, 4.67) | 2.85 (0.85, 9.53)+ | 0.44 (0.09, 0.78)* | |||

| Years sexually active† | - | - | −0.03 (−0.07, 0.02) | |||

| Age | 0.89 (0.76, 1.06) | 0.84 (0.73, 0.98)* | 0.07 (−0.01, 0.14)+ | |||

| Religiosity | 0.98 (0.91, 1.06) | 1.05 (0.99, 1.11) | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.03) | |||

| Grade point average | 1.19 (0.79, 1.78) | 0.61 (0.40, 0.91)* | −0.02 (−0.12, 0.09) | |||

| Parents’ attitudes toward sex | 0.90 (0.62, 1.30) | 0.70 (0.48, 1.01)+ | 0.02 (−0.08, 0.11) | |||

| Substance use | 1.08 (0.92, 1.26) | 1.00 (0.88, 1.14) | −0.01 (−0.05, 0.03) | |||

| Parent relationship quality | 1.05 (0.92, 1.19) | 0.98 (0.90, 1.07) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.07)** | |||

| Relationship Type (Married) | ||||||

| Cohabiting | 0.08 (−0.16, 0.33) | |||||

| Pregnancy | 0.17 (−0.37, 0.72) | |||||

| Currently dating | −0.15 (−0.48, 0.18) | |||||

| Recently dating | −0.13 (−0.68, 0.43) | |||||

| Current Relationship (Yes) | ||||||

| No | −0.82 (−1.19, −0.45)** | |||||

| Relationship Duration (4–8 years) | ||||||

| 0–15 months | 0.12 (−0.19, 0.43) | |||||

| 15 months-4 years | 0.27 (−0.02, 0.56)+ | |||||

| >8 years | 0.11 (−0.16, 0.37) | |||||

| R2 | 0.02** | 0.24** | ||||

| Constant | 4.24 (4.06, 4.43)** | 2.25 (0.43, 4.06)* | ||||

Notes: Referent groups for categorical variables are in parentheses next to the variable names; STI/STD = sexually transmitted infection/disease; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; NH = Non-Hispanic; SES = socioeconomic status; HS = high school; GED = General Educational Development;

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

Lifetime STI/STD diagnosis and lifetime unintended pregnancy analyses are adjusted for years sexually active at the time of the Wave IV interview to account for differences in exposure time

Joint Effects of Initiation Class and Partner Counts

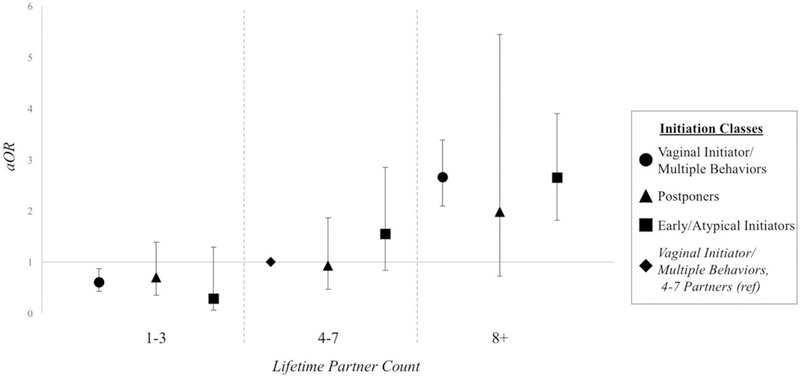

To determine whether the correlates of initiation vary depending on subsequent partnering, we combined variable categories to create initiation-partnering interaction groups. Table 6 includes the adjusted logistic regression models comparing the odds of lifetime STI/STD diagnosis among initiation-partnering groups with members of the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class with 4–7 partners as the referent. Members of the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class with 1–3 lifetime sexual partners had significantly lower odds and Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors with ≥8 lifetime partners had significantly higher odds of lifetime STI/STD diagnosis compared to the odds of the referent group. Early/Atypical Initiators with ≥8 partners had significantly higher odds of lifetime STI/STD diagnosis compared to the odds of the referent group. There were no significant differences for any of the Postponers groups or for Early/Atypical Initiators with fewer than eight partners when compared to the referent. Figure 2 illustrates these results and the emerging trends in the odds of STI/STD diagnosis by initiation- partnering group.

Table 6.

Coefficients (and 95% confidence intervals) from adjusted regression analyses examining all outcomes and selected characteristics

| Lifetime STI/STD diagnosis aOR (95% CI) |

Lifetime unintended pregnancy aOR (95% CI) |

Romantic relationship quality β (95% CI) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiation- Partnering Only |

Full Model | Initiation- Partnering Only |

Full Model | Initiation- Partnering Only |

Full Model | |

| Initiation-Partnering Group (VI/MB, 4–7) | ||||||

| VI/MB, 1–3 | 0.56 (0.39, 0.78)** | 0.61 (0.43, 0.87)** | 0.68 (0.54, 0.85)** | 0.75 (0.59, 0.96)* | 0.22 (0.15, 0.29)** | 0.13 (0.06, 0.20)** |

| VI/MB, ≥8 | 2.08 (1.65, 2.62)** | 2.66 (2.09, 3.38)** | 1.33 (1.12, 1.58)** | 1.42 (1.18, 1.72)** | −0.14 (−0.20, −0.07)** | −0.09 (−0.15, −0.04)** |

| Postponers, 1–3 | 0.46 (0.24, 0.86)* | 0.70 (0.35, 1.39) | 0.56 (0.38, 0.83)** | 0.83 (0.55, 1.23) | 0.19 (0.10, 0.28)** | 0.10 (−0.01, 0.21)+ |

| Postponers, 4–7 | 0.61 (0.30, 1.23) | 0.93 (0.47, 1.86) | 0.45 (0.22, 0.95)* | 0.60 (0.28, 1.26) | −0.01 (−0.19, 0.16) | 0.02 (−0.12, 0.17) |

| Postponers, ≥8 | 0.95 (0.38, 2.35) | 1.98 (0.72, 5.44) | 0.86 (0.41, 1.78) | 1.25 (0.56, 2.79) | −0.20 (−0.46, 0.06) | −0.11 (−0.33, 0.10) |

| Early/Atypical, 1–3 | 0.20 (0.05, 0.83)* | 0.29 (0.06, 1.29) | 0.51 (0.23, 1.10)+ | 0.60 (0.27, 1.36) | 0.28 (0.12, 0.44)** | 0.23 (0.07, 0.38)** |

| Early/Atypical, 4–7 | 1.04 (0.56, 1.92) | 1.55 (0.84, 2.85) | 1.44 (0.93, 2.23)+ | 1.70 (1.08, 2.67)* | 0.06 (−0.14, 0.25) | 0.05 (−0.12, 0.23) |

| Early/Atypical, ≥8 | 1.42 (1.02, 1.98)* | 2.65 (1.81, 3.90)** | 0.88 (0.65, 1.18) | 1.13 (0.83, 1.53) | −0.07 (−0.20, 0.07) | −0.12 (−0.25, 0.01)+ |

| Biological Sex (Male) | ||||||

| Female | 3.69 (3.01, 4.52)** | 1.89 (1.59, 2.23)** | −0.04 (−0.09, 0.01)+ | |||

| Race (NH White) | ||||||

| Hispanic | 1.62 (1.21, 2.17)** | 1.37 (1.03, 1.83)* | −0.14 (−0.22, −0.06)** | |||

| NH Black | 3.36 (2.63, 4.30)** | 1.95 (1.52, 2.48)** | −0.21 (−0.29, −0.14)** | |||

| NH Other | 1.25 (0.83, 1.89) | 1.38 (0.97, 1.95)+ | −0.10 (−0.21, 0.00)+ | |||

| Parent Education (SES; College Grad) | ||||||

| <HS | 0.71 (0.51, 1.01)+ | 1.41 (1.06, 1.88)* | −0.08 (−0.17, 0.01)+ | |||

| HS/GED | 0.76 (0.59, 0.97)* | 1.56 (1.26, 1.94)** | −0.10 (−0.16, −0.03)** | |||

| Some College | 0.85 (0.67, 1.08) | 1.42 (1.20, 1.67)** | −0.09 (−0.15, −0.03)** | |||

| Family Structure (Two biological parents) | ||||||

| Other two parent family | 0.99 (0.72, 1.36) | 1.07 (0.86, 1.33) | −0.03 (−0.09, 0.04) | |||

| Single parent | 1.07 (0.84, 1.36) | 1.24 (1.01, 1.52)* | −0.04 (−0.10, 0.02) | |||

| Other | 1.03 (0.67, 1.60) | 1.89 (1.14, 3.13)* | −0.09 (−0.24, 0.06) | |||

| Coerced Sex (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.30 (0.98, 1.70)+ | 1.37 (1.06, 1.76)* | −0.11 (−0.19, −0.02)* | |||

| Forced Sex (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 1.30 (0.92, 1.85) | 1.01 (0.72, 1.43) | −0.06 (−0.17, 0.06) | |||

| Sexual Abuse (No) | ||||||

| Yes | 0.98 (0.70, 1.37) | 1.09 (0.75, 1.57) | 0.00 (−0.11, 0.11) | |||

| Years sexually active† | - | - | 0.01 (−0.01, 0.02) | |||

| Age | 0.89 (0.85, 0.94)** | 0.94 (0.90, 0.98)** | −0.01 (−0.03, 0.01) | |||

| Religiosity | 0.99 (0.97, 1.02) | 1.01 (0.99, 1.03) | 0.01 (0.00, 0.01)* | |||

| Grade point average | 1.02 (0.90, 1.15) | 0.73 (0.65, 0.82)** | 0.05 (0.02, 0.09)** | |||

| Parents’ attitudes toward sex | 0.87 (0.78, 0.96)** | 0.93 (0.85, 1.01)+ | 0.01 (−0.02, 0.05) | |||

| Substance use | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | −0.01 (−0.02, 0.01) | |||

| Parent relationship quality | 0.97 (0.94, 1.00)+ | 0.95 (0.92, 0.97)** | 0.03 (0.02, 0.04)** | |||

| Relationship Type (Married) | ||||||

| Cohabiting | −0.00 (−0.07, 0.07) | |||||

| Pregnancy | −0.09 (−0.28, 0.10) | |||||

| Currently dating | −0.21 (−0.30, −0.12)** | |||||

| Recently dating | −0.21 (−0.35, −0.06)** | |||||

| Current Relationship (Yes) | ||||||

| No | −0.71 (−0.80, −0.61)** | |||||

| Relationship Duration (4–8 years) | ||||||

| 0–15 months | 0.09 (0.01, 0.18)* | |||||

| 15 months-4 years | 0.16 (0.09, 0.23)** | |||||

| >8 years | −0.02 (−0.10, 0.05) | |||||

| R2 | 0.03** | 0.21** | ||||

| Constant | 4.19 (4.13, 4.24)** | 3.90 (3.35, 4.45)** | ||||

Notes: Referent groups for categorical variables are in parentheses next to the variable names; STI/STD = sexually transmitted infection/disease; aOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; VI/MB = Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors; NH = Non-Hispanic; SES = socioeconomic status; HS = high school; GED = General Educational Development;

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

Lifetime STI/STD diagnosis and lifetime unintended pregnancy analyses are adjusted for years sexually active at the time of the Wave IV interview to account for differences in exposure time

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratios of lifetime STI/STD diagnosis among sexual initiation classes by lifetime sexual partners

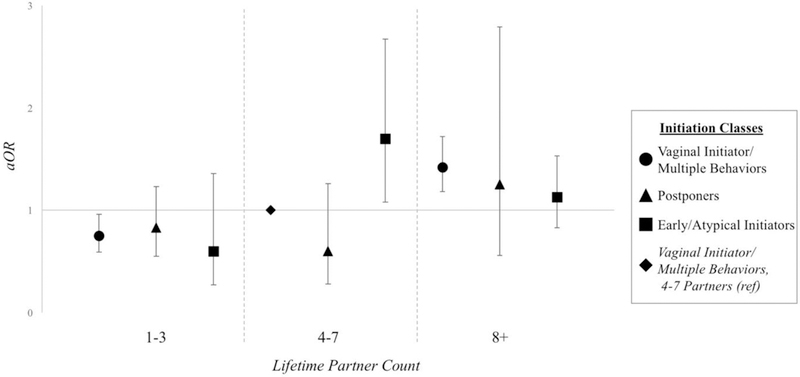

Parallel analyses for unintended pregnancy yielded roughly similar findings. Members of the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class with 1–3 lifetime sexual partners had significantly lower odds and Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors with ≥8 lifetime partners had significantly higher odds of lifetime unintended pregnancy compared to the odds of the referent group. While neither Early/Atypical Initiators with 1–3 partners nor those with ≥8 partners had significantly different odds of unintended pregnancy compared to odds of the referent group, Early/Atypical Initiators with 4–7 partners had significantly higher odds of lifetime experience of an unintended pregnancy compared to the odds of referent. No associations were found for the Postponers (see also Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Adjusted odds ratios of lifetime unintended pregnancy among sexual initiation classes by lifetime sexual partners

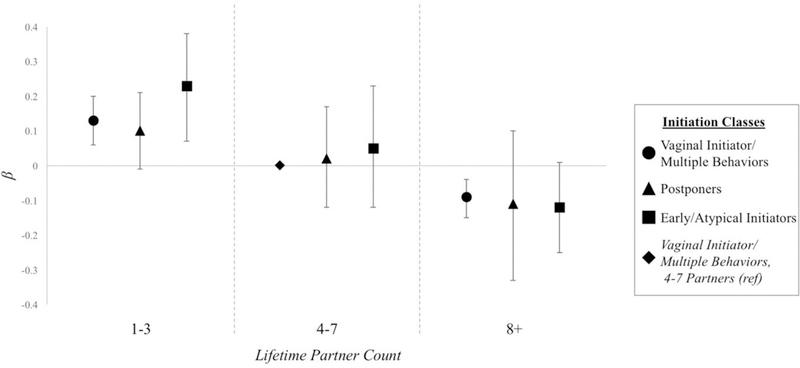

Table 6 also includes the adjusted OLS regression models comparing romantic relationship quality. The full model explained 21% of the variation in romantic relationship quality, with a constant of 3.90. Members of the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class with 1–3 lifetime sexual partners had significantly better and those with ≥8 partners had significantly worse romantic relationship quality compared to those in the referent group. Postponers with 1–3 partners showed better romantic relationship quality than the referent, though this result was only marginally significant. Similarly, Early/Atypical Initiators with 1–3 partners showed significantly better romantic relationship quality than the referent group. Finally, Early/Atypical Initiators with ≥8 partners had lower romantic relationship quality than the referent, though this was not significant at the 0.05 level (see also Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Change in relationship quality among sexual initiation classes by number of lifetime sexual partners

DISCUSSION

Findings in the current study were consistent with previous research demonstrating associations between the timing of first vaginal intercourse and sexual health outcomes.However, our research goes further by considering how variability in sexual partnering within and between sexual initiation classes, classes that consider timing, sequence, variety, and pace of early sexual activity, may affect the association between sexual initiation patterns and later sexual health outcomes.

In stratified analyses within each class, we found that number of partners mattered in different ways, depending on initiation class membership. Within the modal Vaginal Initiator/Multiple Behavior class, number of partners did matter, and number mattered in ways that were consistent with extant literature (Ashenhurst et al., 2017). Having fewer partners was associated with lower odds of STI/STD diagnosis and unintended pregnancy, and with better relationship quality. Having more partners was associated with greater odds of STI/STD diagnosis and unintended pregnancy, and poorer relationship quality. For Postponers, the number of partners one had essentially did not matter: odds of STI/STD diagnosis, unintended pregnancy, and relationship quality did not vary by number of partners. For respondents in the Early/Atypical Initiators class, the role of partner number was more complex. For STI/STDs, members of the Early/Atypical group were like the modal group: having fewer partners was associated with lower odds, and having more partners was associated with greater odds of a lifetime diagnosis. For relationship quality, there was no link with number of partners among members of the Early/Atypical Initiators class. In contrast, for unintended pregnancy, having both fewer and more partners was associated with lower odds compared to having 4–7 partners. One explanation for this may be that the Early/Atypical Initiators group is comprised of more men who could be unaware of a partner’s contraceptive use or pregnancy status, especially in newer partnerships (Garbers et al., 2017; Rendall, Clarke, Peters, Ranjit, & Verropoulou, 1999). Similarly, males with more sexual partners may be less likely to know about a former partner’s pregnancy status. Alternatively, this may indicate more effective contraceptive behavior among those who have more partners, although this conflicts with previous research showing that those who initiate sexual activity earlier or have more sexual partners are less likely to use contraceptive methods at sexual debut and take longer to begin using contraception (Ashenhurst et al., 2017; Finer & Philbin, 2013). Further research is needed to understand how biological sex and contraceptive use may affect unintended pregnancy and/or knowledge about partner pregnancy among youth whose sexual start is similar to that of the Early/Atypical Initiators.

In interaction analyses looking at combinations of number of partners and class membership, we found that there was no statistically significant interaction between number of partners and health outcomes for Postponers (i.e., regardless of number of partners, Postponers’ risk was no different from that of members of the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors class with 4–7 partners). However, comparisons between the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors members with 4–7 partners and members of the Early/Atypical Initiators class did show differences. Early/Atypical Initiators with both the same number of partners (4–7) and with more partners (≥8) had greater odds of a lifetime STI/STD diagnosis than did Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors members with 4–7 partners.1However, Early/Atypical Initiators who had 1–3 partners had better romantic relationship quality. In fact, the Early/Atypical Initiators with 1–3 partners had the greatest difference in romantic relationship quality (β = 0.23) compared to the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors with 4–7 partners, which could be related to having longer-term and more developed romantic relationships due to early initiation and fewer sexual partners.

These complex patterns are consistent with both Life Course Theory and Problem Behavior Theory, and demonstrate the concepts of multifinality and equifinality from General Systems Theory. The pattern of sexual initiation, which captures timing, sequence, and spacing, was associated with subsequent sexual behaviors (i.e., partnering), though initiation pattern did not completely determine the number of sexual partners one has. Within the conventional (Postponers), unconventional (Early/Atypical Initiators), and modal (Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors) initiation class groups, some percentage of members appeared in all partnering categories, and though their initiation pattern was similar, numbers of partners led to different health outcomes (multifinality) for the Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors and Early/Atypical class members, but not for Postponers. However, members of the Postponers and Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors classes were not statistically different in their health outcomes, regardless of partnering behavior (equifinality). Broadly, these results support the hypothesis that both patterns of sexual initiation and partnering have implications for most youth, although the more proximal variable of partnering appears to have stronger implications for the outcomes examined.

Two of our outcomes, namely STI/STDs and unintended pregnancy, were direct consequences of sexual behaviors, while the link between sexual patterns and romantic relationship quality was more complex. Although research has considered the relationship between sexual initiation or sexual partnering and aspects of sexual relationships like sexual satisfaction or sex frequency, little has considered how these variables may affect romantic relationship quality more holistically (Eisenberg, Shindel, Smith, Breyer, & Lipshultz, 2010; Harden, 2012; McGuire & Barber, 2010; O’Donnell et al., 2001; Sandfort et al., 2008). Though not directly related to specific sexual behaviors, our results showed that initiation and partnering have associations with romantic relationship quality that are similar to those with STI/STDs and unintended pregnancy. This is consistent with a holistic view of adolescent sexual and reproductive health, and suggests that physical and sociointerpersonal aspects of relationships should be considered together. It also underscores the importance of including multiple aspects of relationships (e.g., contraception, conflict negotiation) in education curricula (Schalet et al., 2014; The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, 2017).

In this vein, our research has important implications for future sexuality research and education. It is clear that the status quo of abstinence-focused sexuality education programs in the United States is at odds with adolescent experience, and should therefore be adjusted to better meet the needs of youth (Santelli et al., 2017; Schalet et al., 2014; The Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, 2017). Most research has only considered associations between the timing of vaginal sexual initiation and health outcomes, which in turn has affected the design of sexuality education curriculums that promote abstinence until marriage. Our study showed that in addition to how youth start their sexual lives, sexual partnering is key for most youth. Therefore, focusing sex education on safe sexual activity, rather than just abstinence, is a more promising approach to support sexual health, even when the sexual initiation pattern appears to be risky. It also further emphasizes the need to take a more holistic perspective on adolescent sexual and reproductive health. Given that premarital sex is normative, adjusting our focus from abstinence only until marriage and “problem behavior” to risk reduction and positive sexuality in sexual relationships may be particularly effective in improving sexual health outcomes from adolescence to early adulthood (Halpern, 2010; Halpern & Haydon, 2012; Tolman & McClelland, 2011). Future research should continue to incorporate sexual partnering and other such proximal variables, which can help to inform the design of these sexuality education programs.

Strengths and Limitations

One strength of this study was that we used a large, nationally representative sample of youth in the United States. In addition, to our knowledge, this study was the first to examine the importance of lifetime sexual partners in the association between patterns of sexual initiation and related health outcomes. However, the study also had limitations that may affect findings. First, we chose to employ listwise deletion for missing data. While other missing data strategies have been shown to decrease bias (e.g., multiple imputation, maximum likelihood), the literature suggests that the listwise deletion method works well with large samples and a small percentage of missingness, as is the case in Add Health (Basilevsky, Sabourin, Hum, & Anderson, 1985; Kim & Curry, 1977). Another limitation of our analyses was the relatively small size of some our initiation-partnering groups, particularly Postponers with eight or more lifetime sexual partners. This may be a function of the shorter time “at risk” and/or it may reflect other characteristics of Postponer class members that lower the likelihood of high numbers of partners. Wide confidence intervals are likely the result of insufficient statistical power, and future research with upcoming waves of Add Health data when Postponers have been sexually active for longer may help us to understand the relationship between delayed sexual activity, subsequent partnering, and sexual health outcomes. Another limitation of our study was the exclusion of those who reported same sex partners, which prevents the generalizability of our findings to sexual minority populations. Recent research suggests differences in sexual initiation patterns and health disparities among members of this group; thus, future research should consider the unique patterns and related health outcomes for this population (Goldberg & Halpern, 2017).

Conclusion

Within each identified sexual initiation class, there was variation in subsequent partnering, demonstrating that characteristics of sexual initiation do not necessarily determine subsequent behavior. Further, while both sexual initiation patterns and sexual partnering from adolescence to early adulthood each add important information for understanding sexual health, partnering may have more important implications for outcomes such as STI/STD diagnosis, unintended pregnancy, and relationship quality. These results can also inform research, practice, and policies that promote a more comprehensive approach to sexual education focused on the understanding of sexual risk in order to prevent STI/STDs and unintended pregnancy, and to increase romantic relationship quality among adolescents and adults (Schalet et al., 2014).

Acknowledgements

This research uses data from Add Health, a program project designed by J. Richard Udry, Peter S. Bearman, and Kathleen Mullan Harris. Special acknowledgment is due Ronald R. Rindfuss and Barbara Entwisle for assistance in the original design. Persons interested in obtaining Data Files from Add Health should contact Add Health, The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Carolina Population Center, 206 W. Franklin Street, Chapel Hill, NC 27516-2524 (addhealth_contracts@unc.edu).

We are grateful to the Carolina Population Center for general support (P2C HD050924).

Footnotes

Post hoc analyses stratified by partner group showed few differences across sexual initiation classes for each outcome (results available upon request). Among those with 4–7 partners, Early/Atypical Initiators had 1.71 times greater odds of unintended pregnancy compared to the odds of Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors members. Although only marginally significant, members of the Early/Atypical class with ≥8 partners had 0.77 times lower odds of an unintended pregnancy than Vaginal Initiators/Multiple Behaviors members with the same number of partners (p = .059). No such differences emerged for STI/STD diagnosis and romantic relationship quality.

REFERENCES

- Ashenhurst JR, Wilhite ER, Harden KP, & Fromme K (2017). Number of sexual partners and relationship status are associated with unprotected sex across emerging adulthood. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46, 419–432. 10.1007/s10508-016-0692-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basilevsky A, Sabourin D, Hum D, & Anderson A (1985). Missing data estimators in the general linear model: An evaluation of simulated data as an experimental design. Communications in Statistics-Simulation and Computation, 14, 371–394. 10.1080/03610918508812445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2016). Adolescents and young adults: sexually transmitted diseases. Retrieved September 28, 2016, from http://www.cdc.gov/std/life-stages-populations/adolescents-youngadults.htm

- Cicchetti D, & Rogosch FA (1996). Equifinality and multifinality in developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 8, 597–600. 10.1017/S0954579400007318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan JE, Jessor R, & Costa FM (1991). Adolescent health behavior and conventionality-unconventionality: An extension of Problem-Behavior Theory. Health Psychology, 70, 52–61. 10.1037/0278-6133.10.L52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg ML, Shindel AW, Smith JF, Breyer BN, & Lipshultz LI (2010). Socioeconomic, anthropomorphic, and demographic predictors of adult sexual activity in the United States: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7, 50–58. 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01522.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, & Shanahan MJ (2006). The life course and human development. In Damon W & Lerner RM (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology (6th ed., pp. 665–715). Hoboken, NJ; John Wiley and Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, & Lynskey MT (1997). Childhood sexual abuse, adolescent sexual behaviors and sexual revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect, 21, 789–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB, & Philbin JM (2013). Sexual initiation, contraceptive use, and pregnancy among young adolescents. Pediatrics, 131, 886–891. 10.1542/peds.2012-3495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finer LB, & Zolna MR (2011). Unintended pregnancy in the United States: Incidence and disparities, 2006. Contraception, 84, 478–485. http://doi.org/10.1016Zj.contraception.2011.07.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbers S, Scheinmann R, Gold MA, Catallozzi M, House L, Koumans EH, & Bell DL (2017). Males’ ability to report their partner’s contraceptive use at last sex in a nationally representative sample: Implications for unintended pregnancy prevention evaluations. American Journal of Men’s Health, 11, 711–718. 10.1177/1557988316681667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg SK, & Halpern CT (2017). Sexual initiation patterns of sexual minority youth: A latent class analysis. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 49, 55–67. 10.1363/psrh.12020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT (2010). Reframing research on adolescent sexuality: Healthy sexual development as part of the life course. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 42, 6–7. 10.1363/4200610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, & Haydon AA (2012). Sexual timetables for oral-genital, vaginal, and anal intercourse: Sociodemographic comparisons in a nationally representative sample of adolescents. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1221–1228. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halpern CT, Waller MW, Spriggs A, & Hallfors DD (2006). Adolescent predictors of emerging adult sexual patterns. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 926 10.1016/jjadohealth.2006.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP (2012). True love waits? A sibling-comparison study of age at first sexual intercourse and romantic relationships in young adulthood. Psychological Science, 23, 1324–1336. 10.1177/0956797612442550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Halpern CT, Whitsel E, Hussey J, Tabor J, Entzel P, & Udry JR (2009). Add Health Research Design. Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/design [Google Scholar]

- Harris KM, Udry JR, & Bearman PS (2013). The Add Health Study: Design and accomplishments. Chapel Hill, NC. Retrieved from http://www.cpc.unc.edu/projects/addhealth/documentation/guides/DesignPaperWIIV.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Haydon AA, Herring AH, & Halpern CT (2012a). Associations between patterns of emerging sexual behavior and young adult reproductive health. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 44, 218–227. 10.1363/4421812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydon AA, Herring AH, Prinstein MJ, & Halpern CT (2012b). Beyond age at first sex: Patterns of emerging sexual behavior in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health, 50, 456–463. 10.1016/jjadohealth.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heywood W, Patrick K, Smith AMA, & Pitts MK (2015). Associations between early first sexual intercourse and later sexual and reproductive outcomes: A systematic review of population-based data. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44, 531–569. 10.1007/s10508-014-0374-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hipwell AE, Stepp SD, Keenan K, Chung T, & Loeber R (2011). Parsing the heterogeneity of adolescent girls’ sexual behavior: Relationships to individual and interpersonal factors. Journal of Adolescence, 34, 589–592. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsueh J, & Knox V (2014). Supporting healthy marriage evaluation: Eight sites within the United States, 2003–2013 Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. [Google Scholar]

- Jessor R, & Jessor SL (1977). Problem behavior and psychosocial development. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jurich JA, & Myers-Bowman KS (1998). Systems theory and its application to research on human sexuality. Journal of Sex Research, 35, 72–87. 10.1080/00224499809551918 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaestle CE, Halpern CT, Miller WC, & Ford CA (2005). Young age at first sexual intercourse and sexually transmitted infections in adolescents and young adults. American Journal of Epidemiology, 161, 774–780. 10.1093/aje/kwi095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-O, & Curry J (1977). The treatment of missing data in multivariate analysis. Sociological Methods & Research, 6, 215–240. [Google Scholar]

- Lanza ST, Kugler KC, & Mathur C (2011). Differential effects for sexual risk behavior: An application of finite mixture regression. The Open Family Studies Journal, 4(Suppl. 1- MP), 81–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner JE, & Hawkins RL Welfare, liberty, and security for All? U.S. sex education policy and the 1996 Title V Section 510 of the Social Security Act. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45, 1027–1038. 10.1007/s10508-016-0731-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire JK, & Barber BL (2010). A person-centered approach to the multifaceted nature of young adult sexual behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 7, 301–313. 10.1080/00224490903062266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell CM, Kaufman CE, Beals J, Bauduy S, Bell CAE, Crow CB, ... Kaufman B (2004). Equifinality and multifinality as guides for preventive interventions: HIV risk/protection among American Indian young adults. Journal of Primary Prevention, 25, 491–510. 10.1023/B:J0PP.0000048114.49642.b2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moilanen KL, Crockett LJ, Raffaelli M, & Jones BL (2010). Trajectories of sexual risk from middle adolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 114–139. 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00628.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher WD, Jones J, & Abma JC (2012). Intended and unintended births in the United States: 1982–2010 National Health Statistics Reports (Vol. 55). Hyattsville, MD: Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr055.pdf [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll JG, Trickett PK, & Putnam FW (2003). A prospective investigation of the impact of childhood sexual abuse on the development of sexuality. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 575–586. 10.1037/0022-006X.7L3.575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell BL, O’Donnell CR, Stueve A, O’Donnell L, O’Donnell CR, & Stueve A (2001). Early sexual initiation and subsequent sex-related risks among urban minority youth: The Reach for Health Study. Family Planning Perspectives, 33, 268–275. 10.2307/3030194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese BM, Choukas-Bradley S, Herring AH, & Halpern CT (2014). Correlates of adolescent and young adult sexual initiation patterns. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 46, 211–221. http://doi.org/10.136¾6e2214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese BM, Haydon AA, Herring AH, & Halpern CT (2013). The association between sequences of sexual initiation and the likelihood of teenage pregnancy. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 228–233. 10.1016/jjadohealth.2012.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendall MS, Clarke L, Peters HE, Ranjit N, & Verropoulou G (1999). Incomplete reporting of men’s fertility in the United States and Britain: A research note. Demography, 36, 135–144. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2648139 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick MD, Bearman PS, Blum RW, Bauman KE, Harris KM, Jones J, ... Udry JR (1997). Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association, 278, 823–832. 10.1001/jama.1997.03550100049038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort TGM, Orr M, Hirsch JS, & Santelli J (2008). Long-term health correlates of timing of sexual debut: Results from a national US study. American Journal of Public Health, 98, 155–161. 10.2105/AJPH.2006.097444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Kantor LM, Grilo SA, Speizer IS, Lindberg LD, Heitel J, ... Ott MA (2017). Abstinence-only-until-marriage: An updated review of U.S. policies and programs and their impact. Journal of Adolescent Health, 61, 273–280. 10.1016/jjadohealth.2017.05.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassler S, Addo FR, & Lichter DT (2012). The tempo of sexual activity and later relationship quality. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 708–725. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2012.00996.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schalet AT, Santelli JS, Russell ST, Halpern CT, Miller SA, Pickering SS, ... Hoenig JM (2014). Broadening the evidence for adolescent sexual and reproductive health and education in the United States [Invited commentary]. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1595–1610. 10.1007/s10964-014-0178-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]