Abstract

There is now strong evidence that ecosystem properties are influenced by alterations in biodiversity. The consensus that has emerged from over two decades of research is that the form of the biodiversity–functioning relationship follows a saturating curve. However, the foundation from which these conclusions are drawn mostly stems from empirical investigations that have not accounted for post-extinction changes in community composition and structure, or how surviving species respond to new circumstances and modify their contribution to functioning. Here, we use marine sediment-dwelling invertebrate communities to experimentally assess whether post-extinction compensatory mechanisms (simulated by increasing species biomass) have the potential to alter biodiversity–ecosystem function relations. Consistent with recent numerical simulations, we find that the form of the biodiversity–function curve is dependent on whether or not compensatory responses are present, the cause and extent of extinction, and species density. When species losses are combined with the compensatory responses of surviving species, both community composition, dominance structure, and the pool and relative expression of functionally important traits change and affect species interactions and behaviour. These observations emphasize the importance of post-extinction community composition in determining the stability of ecosystem functioning following extinction. Our results caution against the use of the generalized biodiversity–function curve when generating probabilistic estimates of post-extinction ecosystem properties for practical application.

Keywords: evenness, ecosystem function, effect traits, response traits, extinction debt, species response

1. Introduction

Populations can respond to the loss of, or reduction in, the number of individuals or species in a community through various compensatory mechanisms, including numeric [1–3], biomass [4,5] and/or per capita processing rate responses [6], or via mechanisms that effectively absorb disturbances through changes in trophic interactions [7]. Such expressions are often associated with adjustments in the competitive balance between species [8–10], contributing to resource-release and new opportunities [7,11–14] or a change in the prevalence and strength of functionally important species interactions [15] that allow a subset of species to prosper and exhibit compensatory responses to novel circumstances. Intuitively, such fundamental changes in community structure are likely to modify community contributions to functioning and, ultimately, define the long-term legacy of a perturbation. Yet, the effects of compensatory responses on ecosystem functioning are not well understood, despite recognition that there are multiple instances of species compensation in geological records following major perturbation events [16–19], some of which appear to be a part of a global pattern [20]. Many of these events are associated with regime shifts, in which substantive rearrangement in functional trait composition and the use of novel space following species decline takes place and has concomitant effects on ecosystem properties [20]. These effects are not necessarily negative, the realized level of functioning can be conditional on trophic structure and/or the variation within, and covariation between, the response and effect traits of the surviving community [21]. This means that the level of functioning may be maintained, reduced or enhanced relative to the pre-extinction condition. It follows, therefore, that the general form of the positive but decelerating biodiversity–ecosystem functioning curve that emerges from 2 decades of experimentation [22,23] is unrepresentative of the most likely post-disturbance outcome for ecosystem functioning. Many community processes and dynamics that are known to have compensatory attributes [24,25] have not been fully considered within the biodiversity–function experimental framework.

Recent studies have shown that the order in which species are lost can influence ecosystem properties [25–27], and that the potential of the surviving community to compensate for the loss or reduction in functionally important species will be dependent on the level of functional redundancy [28–31] and on realized levels of species richness [32–35]. Evidence suggests that the effects of compensation can increase (over-compensation, [5,36,37]), maintain (complete compensation [1]) or reduce (partial to no compensation [38]) ecosystem functioning, and that the ecosystem consequences of biodiversity loss could be buffered by the presence of a low number of functionally important species [5,39]. While this may be appealing from a management or conservation perspective, such a synthesis ignores other important aspects of post-perturbation community dynamics. In particular, recent numeric simulations [26,27] and field observations [5] suggest that ecosystem responses to perturbation may be dependent on the type of compensation that develops in the surviving community [25], but because these conclusions can take extended time periods to develop [5], they have not been empirically tested and are yet to be incorporated into ecosystem models.

Here, we experimentally explore how the effects of biomass compensation following the loss of sediment-dwelling marine invertebrates may affect sediment mixing and associated levels of nutrient generation in model benthic communities. Specifically, invertebrate communities were assembled to reflect a sequence of species loss that was random or ordered by body size or rarity to represent likely generic sources of extinction risk [40–43]. We simulated post-extinction compensation by introducing additional individuals of the ‘surviving’ species, circumventing the need for lengthy studies that incorporate recruitment and growth over several generations. It was anticipated that functional compensation would be less pronounced in communities in which extinction order is related to body size, as body size is often correlated with benthic ecosystem functioning [26] and is considered a key species trait at the population level [44]. Similarly, given that species which occur at low abundances generally contribute little to the ecosystem function inventory, compensation in response to the loss of rare species was expected to lead to elevated levels of functioning (sensu, the insurance hypothesis [45,46]). Irrespective of extinction scenario, we anticipated that compensatory effects would be more accentuated in communities of high evenness, because traits are more evenly distributed relative to those communities assembled to reflect natural evenness levels where functional dominance is prevalent.

2. Methods

(a). Faunal and sediment collection

Sediment (mean ± s.e., n = 4: D50 = 6.122 ± 0.105 µm; total organic carbon = 11.058 ± 1.087%) and specimens of the gastropod Peringia ulvae were collected from the Hamble Estuary, UK (50°52′22.8″ N 1°18′48.9″ W), while the amphipod Corophium volutator was collected from Hayling Island, UK (50°49′56.9″ N 0°58'36.8″ W) in April 2015. Both P. ulvae and C. volutator were collected by sieving surface sediment (1 mm and 500 µm mesh, respectively). Individuals of the polychaete Hediste diversicolor were collected by hand from Langstone Harbour, Portsmouth (50°50′46.5″ N 1°00′05.3″ W). These three species co-occur at the two sites, but sampling location reflected logistical convenience. The sediment was sieved (500 µm mesh) in a seawater bath to remove macrofauna, allowed to settle (48 h to retain the fine fraction, less than 63 µm), and homogenized by stirring prior to distribution between experimental aquaria.

(b). Experimental design

We assembled replicate (n = 4) transparent acrylic aquaria (12 × 12 cm, 35 cm high; 10 cm sediment overlain by 20 cm seawater, salinity approx. 33) containing all possible permutations of species composition (no macro-invertebrates, species in monoculture and in combinations of two or three species) for three scenarios of species loss, where the probability of extinction was either random (1/n, eight assemblages) or ordered sequentially in proportion to body size (largest species expire first, four assemblages) or relative abundance (rarity, species with lowest abundance expire first; four assemblages). To test the effects of post-extinction biomass compensation, this set of aquaria were duplicated in order to include a set of non-interactive communities that experienced no biomass compensation, i.e. species biomass declined with loss of species; versus a set of interactive communities in which complete biomass compensation was simulated by maintaining the total biomass of each community across the remaining species (electronic supplementary material, tables S1 and S2). This design was repeated across two levels of evenness that represent organism density distributions that are either evenly distributed and typical of most biodiversity–ecosystem function experiments (J1) or that contain a dominance hierarchy more typical of a natural system (J0.67, based on field observations; [47–49]). Hence, the experimental design required a total of 256 aquaria (figure 1), all of which were maintained in a water bath at 12°C under a 12 L : 12 D light : dark regime and continually aerated for 12 days.

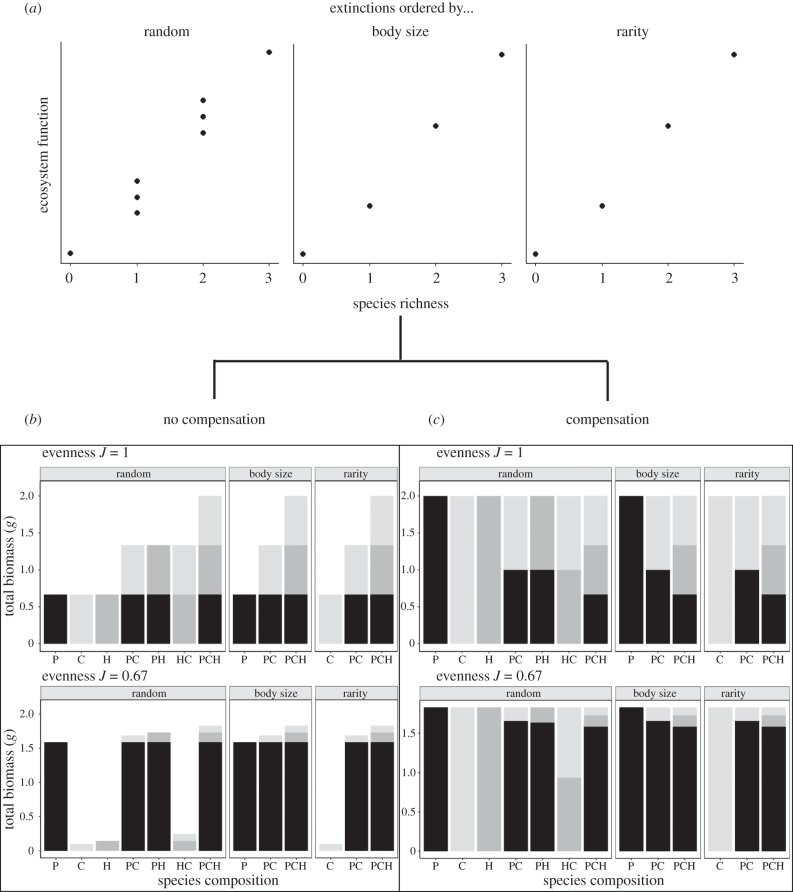

Figure 1.

Summary of the experimental design. Communities were assembled to reflect extinction scenarios that assumed (a) random extinction, representing the full spectrum of possible species combinations, versus trait-based extinctions ordered by body size (i.e. body mass) or relative abundance (rarity). Each scenario of extinction consisted of (b) a set of non-interactive communities that experienced no biomass compensation versus (c) a set of interactive communities that experienced complete biomass compensation in response to declining species richness. The design was repeated across two levels of evenness that represent those typical of experimental (J1) versus natural (J0.67) systems. C, Corophium volutator; H, Hediste diversicolor; P, Peringia ulvae for monoculture and combination of abbreviations for species mixtures. Shading of bars indicates the proportional representation of each species (C, light grey; H, dark grey; P, black).

(c). Measurements of ecosystem process and functioning

Fluorescent sediment profile imaging (f-SPI) was used to quantify the extent of infaunal particle reworking [50]. This technique allows the redistribution of an optically distinct particulate tracer (60 g red coloured sand aquaria−1, fluorescent under ultraviolet light; Brianclegg Ltd, UK) to be quantified from a composite image (Canon 400D, set to 10 s exposure, aperture f5.6 and ISO400; 3888 × 2592 pixel, effective resolution 62.5 µm pixel−1) of the four sides of each aquarium using a custom-made, semi-automated macro within ImageJ (1.47v). From these data, the mean (f-SPILmean, a time-dependent indication of mixing), median (f-SPILmed, the extent of mixing typically encountered over the short term) and maximum (f-SPILmax, the extent of mixing, including infrequent deep mixing events, achieved over the long term) depths of particle redistribution were calculated as an indicator of macro-invertebrate reworking [51]. In addition, surface boundary roughness (SBR, the maximal vertical deviation of the sediment–water interface) was determined as an indication of surficial activity.

Burrow ventilation, a significant transport mechanism in the exchange of solutes between the pore water and overlying water, was estimated on day 12 from changes in the concentration of the inert tracer sodium bromide (Δ[Br−], mg l−1; [52] over a 4 h period (aeration disabled) following the addition of sodium bromide (2.74 g, raising water column concentration of bromide to 9.25 mmol l−1), and quantified using a Tecator flow injection auto-analyser (FIA Star 5010 series).

Water column nutrient concentrations ([NH4–N], [NOx–N] and [PO4–P]) were determined (Tecator flow injection auto-analyser, FIA Star 5010 series) from samples (10 ml, 0.45 µm pre-filtered, day 12) taken from the centre of each aquarium approximately 5 cm above the sediment–water interface.

(d). Statistical analyses

A total of seven statistical models were developed, one for each of the dependent variables (SBR, f-SPILmean, f-SPILmed, f-SPILmax, Δ[Br−], [NH4–N], [NOx–N], [PO4–P]) with species richness, extinction order and compensation as fixed effects. The control treatments were excluded from the statistical analyses, as the focus is to assess the effects of different extinction scenarios and not the presence/absence of macrofauna on ecosystem properties. The initial linear models were assessed visually for normality (Q–Q plot), homogeneity of variance (plotted residual versus fitted values) as well as for influential data points (Cook's distance) [53]. In cases where data exploration indicated heterogeneity of variances, relationships were defined using restricted maximum likelihood and generalized least-squares (GLS) estimation [54]. The use of GLS allows the variance structure to be modelled using appropriate variance functions (here ‘varIdent’ for nominal explanatory variables) rather than transforming the data [53,54]. The model with and without the variance covariate term was compared using Akaike information criterion (AIC, model improvement indicated by a reduction of greater than or equal to 2 units) and by visual inspection, plotting residuals versus fitted values, in order to identify the optimal random effects structure for each response variable [53,55]. The optimal fixed effects model was estimated using maximum-likelihood (ML) estimation and determined using a backward selection procedure informed by AIC [55]. All statistical analysis was performed using the ‘R’ statistical and programming environment [56] and the ‘nlme’ R package (v. 3.1-128, 2016) [57].

3. Results

The analyses confirm that both the sequence in which species are extirpated, the level of species richness and the degree of species evenness are important for both ecosystem process (SBR, f-SPILmean, f-SPILmed, f-SPILmax, Δ[Br−]) and functioning ([NH4–N], [NOx–N], [PO4–P]), and that post-extinction community dynamics are particularly influential in determining ecosystem properties. Indeed, when the total biomass of each community was maintained to simulate biomass compensation, the type and extent of particle reworking dramatically altered and subsequently led to changes in nutrient generation. These compensatory effects were stronger in even communities (J1, figures 2 and 4) relative to those observed for uneven communities (J0.67, figures 3 and 5).

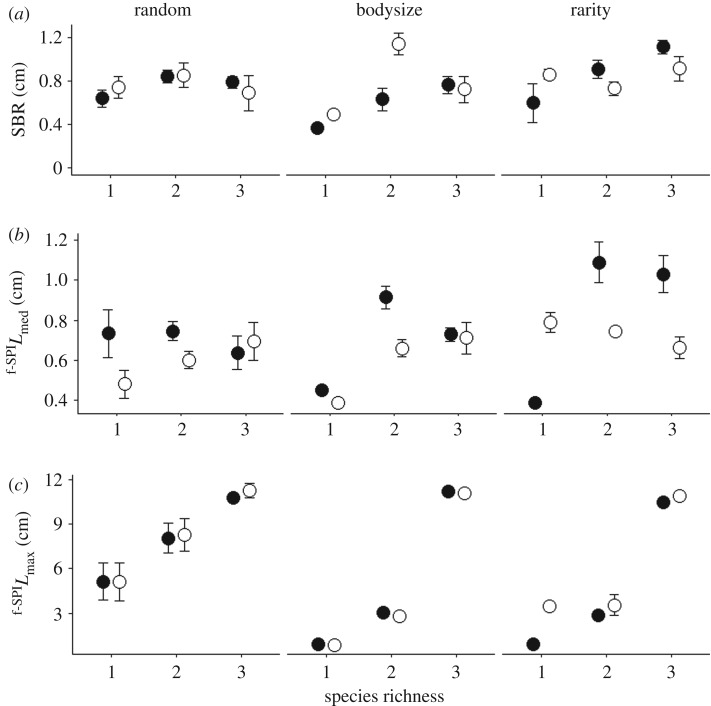

Figure 2.

Interactive effects of extinction scenario (random or ordered by body size or rarity), species richness and biomass compensation (present, closed circle; absent, open circle) on mean (±s.e., n = 4) (a) SBR, (b) median depth of particle reworking (f-SPILmed), and (c) maximum depth of particle reworking (f-SPILmax) for communities with even species distribution (J1). For visual clarity, compensation levels are horizontally offset.

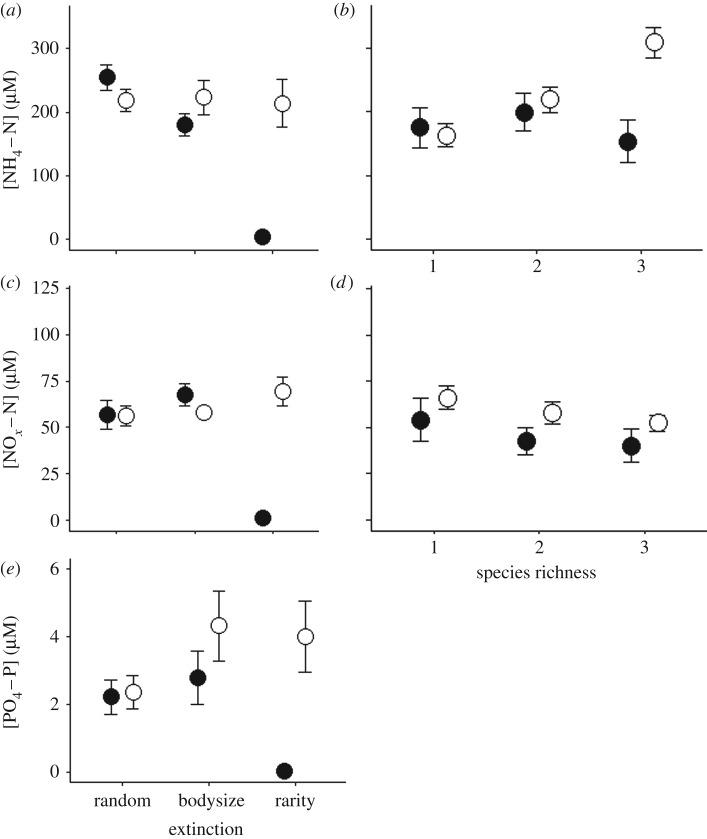

Figure 4.

Effects of (a,c,e) extinction scenario (random, body size, rarity) or (b,d) species richness in the absence (open circle) versus presence (closed circle) of compensation in even (J1) communities on mean (±s.e., n = 4) [NH4–N], [NOx–N] and [PO4–P].

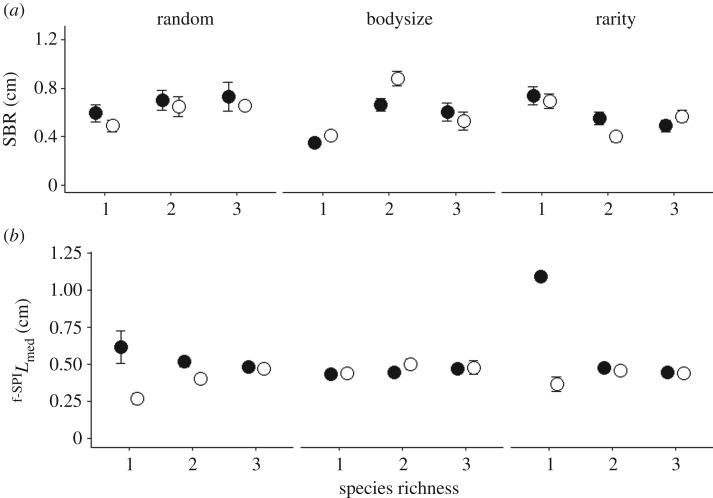

Figure 3.

Interactive effects of extinction scenario (random or ordered by body size or rarity), species richness and biomass compensation (absent, open circle; present, closed circle) on mean (±s.e., n = 4) (a) SBR and (b) maximum depth of particle reworking (f-SPILmax) in uneven communities (J0.67). For clarity, compensation levels are offset horizontally.

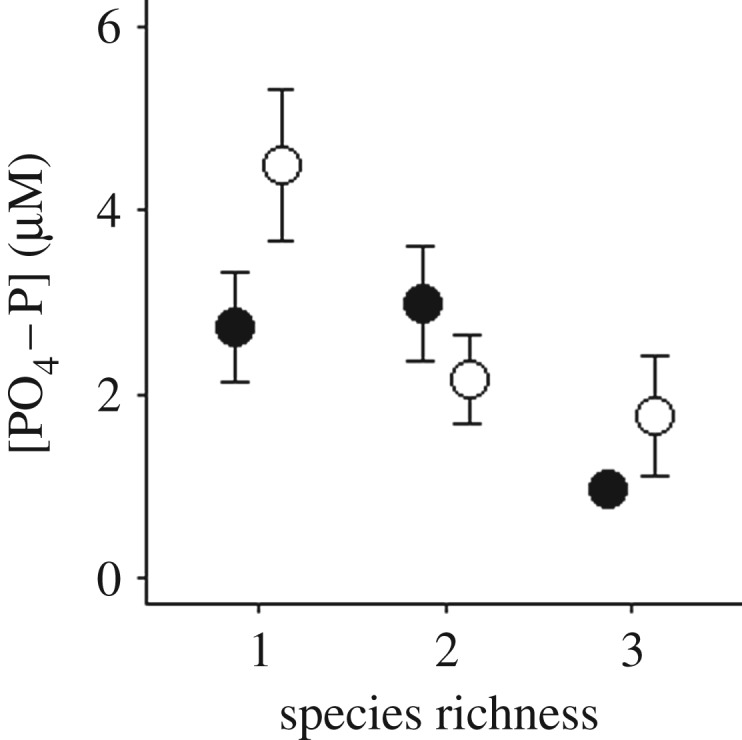

Figure 5.

The interactive effects of species richness and compensatory dynamics (present, closed circle; absent, open circle) for uneven (J0.67) communities on mean (±s.e., n = 4) [PO4–P].

(a). Effects on particle reworking and burrow ventilation

In even communities (J1), SBR was dependent on a three-way interaction between compensatory response × order of extinction × species richness (L-ratio = 12.4925, d.f. = 4, p = 0.014; electronic supplementary material, model S1; figure 2a). Specifically, SBR decreased in non-compensatory communities with decreasing species richness when extinction was ordered by body size or by rarity. In communities with compensatory responses, SBR also decreased with declining species richness when extinction was ordered by body size, but not when extinction was ordered by rarity (figure 2a). However, when extinction was random, there was little change in SBR with species richness in both compensatory and non-compensatory communities (figure 2a), most likely because species that inhabit or otherwise interact with the sediment–water interface form a distinct functional group and were not preferentially removed from the community. The median depth of particle reworking (f-SPILmed) and the maximum mixed depth of particle reworking (f-SPILmax) were dependent on the interactive effects of compensatory response × order of extinction × species richness (f-SPILmed: L-ratio = 32.2030, d.f. = 4, p < 0.0001; electronic supplementary material, model S2; figure 2b; f-SPILmax: L-ratio = 18.9542, d.f. = 4, p = 0.0008; electronic supplementary material, model S3; figure 2c). In communities with compensation, f-SPILmed decreased when extinction occurred randomly and when ordered by body size, but in communities without compensation, f-SPILmed decreased when extinction was ordered by body size or by rarity. Overall, the maximum mixing depth (f-SPILmax) decreased strongly with declining species richness irrespective of extinction scenario, with little difference between communities with and without compensation (figure 2c). Burrow ventilation (Δ[Br−]) significantly reduced with species richness irrespective of extinction or compensation scenario (L-ratio = 6.4222, d.f. = 2, p = 0.0403; electronic supplementary material, model S4, figure S1).

For uneven communities that are representative of natural systems (J0.67), the results revealed that SBR and the median mixed depth of particle reworking was dependent on the interaction compensatory response × order of extinction × species richness (SBR: L-ratio = 12.5304, d.f. = 4, p = 0.0138; electronic supplementary material, model S8; figure 3a; f-SPILmed: L-ratio = 23.8706, d.f. = 4, p = 0.0001; electronic supplementary material, model S9; figure 3b). Patterns for SBR under random extinction showed a small net decline with decreasing species richness, with a slightly greater decrease in the presence of compensation (figure 3a). When extinction was ordered by body size, SBR in both compensatory and non-compensatory communities was highest at intermediate levels of species richness and decreased with species loss (figure 3a). By contrast, when extinction was driven by species rarity (figure 3a), SBR increased with decreasing species richness for both compensatory and non-compensatory communities. When extinction was random or ordered by rarity, the median mixing depth decreased with species richness in communities without compensation but increased in communities with compensation (figure 3b). When extinction was ordered by body size, irrespective of compensatory dynamics, f-SPILmed was maintained as species richness declined (figure 3b). There was no effect of compensation on the maximum mixed depth of particle reworking or on burrow ventilation, both of which were dependent on an interactive effect of species richness × order of extinction (f-SPILmax: L-ratio = 52.8775, d.f. = 4, p < 0.0001; electronic supplementary material, model S10; Δ[Br−]: L-ratio = 16.2130, d.f. = 4, p = 0.0027; electronic supplementary material, model S11, figure S2a,b).

(b). Effects on nutrient generation

In community assemblages with even species distribution, water column nutrient concentrations were affected by the interactive effects of compensatory response × order of extinction ([NH4–N]: L-ratio = 23.3478, d.f. = 2, p < 0.001; electronic supplementary material, model S5; figure 4a); [NOx–N]: L-ratio = 7.4958, d.f. = 2, p = 0.0236; electronic supplementary material, model S6; figure 4c; [PO4–P]: L-ratio = 8.3114, d.f. = 2, p = 0.0157; electronic supplementary material, model S7; figure 4e) as well as compensatory response × species richness ([NH4–N]: L-ratio = 25.4207, d.f. = 2, p < 0.001; electronic supplementary material, model S5; figure 4b; [NOx–N]: L-ratio = 26.2201, d.f. = 2, p < 0.001; electronic supplementary material, model S6; figure 4d). In the presence of compensatory dynamics [NH4–N] and [NOx–N] showed similar patterns to one another, irrespective of extinction scenario (figure 4a,c, respectively); however, in the absence of compensatory dynamics [NH4–N] and [NOx–N] substantively decreased when extinctions were ordered by rarity. For compensatory response × species richness, [NH4–N] decreased with species loss when compensation was present (figure 4b), while [NOx–N] increased with decreasing species richness, irrespective of compensation scenario (figure 4d).

[PO4–P] was highest in communities with compensation when extinction was ordered by body size or rarity, but lowest in the absence of compensatory dynamics when extinction was driven by rarity.

In uneven communities, irrespective of compensation scenario, [NH4–N] and [NOx–N] were dependent on the interactive effects of species richness × order of extinction ([NH4–N]: L-ratio = 24.6755, d.f. = 4, p = 0.0001; electronic supplementary material, model S12, figure S3a; [NOx–N]: L-ratio = 9.78363, d.f. = 2, p = 0.0442; electronic supplementary material, model S13, figure S3a). By contrast, [PO4–P] was dependent on an interaction between compensatory response × species richness (L-ratio = 6.51340, d.f. = 2, p = 0.0385; electronic supplementary material, model S14; figure 5). Overall, [PO4–P] increased with decreasing species richness and was higher in the presence of compensatory dynamics (figure 5).

4. Discussion

Our study provides empirical evidence, consistent with the predictions of recent trait-based simulations of species loss [25], that the ecosystem consequences of extinction can be fundamentally altered by compensatory responses within the surviving community. However, we find that the strength of such a response is contingent on compositional differences that arise from the order of species loss and the number of species remaining in the post-extinction community [26,27,58]. Further, we find that the effects of biomass compensation, although not as strong as anticipated, are less prominent in uneven communities that have a structure typical of natural communities than in communities with an even species distribution, as per the archetypal design of biodiversity–ecosystem function experiments [22]. This distinction is important because a majority of experimental manipulations of biodiversity fall short of allowing community dynamics and compensatory responses to fully develop [59,60], reducing the likelihood of conveying the most likely community response to extinction for a natural setting [61,62]. Recent work has shown that adjustments to community structure in the absence of species loss can have consequential effects on ecosystem functioning that relate to the rank order of species dominance [49], rather than dominant species identity [63,64], and changes in species density and biomass [65–69]. Such transient changes in how dominance and identity are represented as communities respond to forcing over time [70] have important ramifications for the design and analysis of contemporary biodiversity experiments [71,72], as well as the relevance of their findings for practical application [73]. The results also reinforce the role of species trait identity and variability [74] as major determinants of ecosystem functioning [22].

At a broader ecological level, our findings indicate that the ecological consequences of extinction are unlikely to meet expectation (i.e. some form of a positive but decelerating curve [22,23]) when projections are based on pre-extinction community properties and dynamics [75]. This is because the type, timing and severity of extinction generates a legacy that influences the capacity of, and way in which, the surviving community will respond and affect ecosystem properties. The complexities of how species respond to novel circumstances are difficult to anticipate and are yet to be fully explored, even in relation to near-term aspects of climate change [76]. However, understanding variability in species responses to abiotic and biotic change [77], as well as the context-dependent contributions they make to ecosystem functioning over time [59,78,79], will help to refine the likelihood of various ecological outcomes against specific scenarios. Here, biomass compensation had a positive effect on sediment reworking in even communities, especially at intermediate levels of species richness, while incidences of over-compensation were particularly pronounced at high levels of species richness [80]. For uneven communities, functioning was only maintained when extinctions were random or ordered by rarity. However, when extinction was driven by body size in both even and uneven communities, pre-extinction levels of sediment mixing could not be maintained in the surviving community, regardless of the identity and ordering of the compensating species because smaller species contribute little to bioturbation [26,41]. By contrast, where species shared physiological and/or behavioural traits across the species pool, as was the case for SBR, functioning was generally maintained across the species richness gradient. Hence, the presence and expression of species traits dictate how the surviving community moderate ecosystem properties, and explain why ordered species extinctions can result in no change in some functions and large changes in other functions [26,49], but these patterns can be further modified by compensatory adjustments to the assemblage.

Our findings are in broad agreement with previous hypotheses which state that the potential or probability for compensatory dynamics countering the consequences of biodiversity loss will depend on the level of functional redundancy within a system [80,81], but they acknowledge the importance of species that exhibit low or different effect trait values in maintaining ecosystems as circumstances change. Ultimately, the net ecosystem response is a multiple of the role of which species survive and the population response to perturbation, including the sequence of species loss [82]. We find that the effect of extinction order is driven by species-specific differences within a community, and especially the disproportionate effect of H. diversicolor on the depth of particle mixing and the inability of the mud snail P. ulvae to replace the loss of bioturbation activity previously performed by other species [38,51,83]. While this demonstrates that compensatory effects are not always able to buffer the changes in ecosystem processes and functions associated with species loss [84], our data suggest that, on average, compensatory mechanisms will be sufficient to reduce, in whole or in part, the ecological consequences of species loss. Indeed, nutrient release was either maintained or increased in the presence of compensation, even when extinction was driven by body size, and there is some evidence to suggest that other mechanisms may lead to over-compensation prior to the development of community dynamics over the longer term. Higher levels of functional redundancy, for example, will be particularly important as circumstances change and may lessen the likelihood and/or magnitude of unstable fluctuations in ecosystem properties. Although the present study was unable to account for processes that act over longer time scales, such as adaptation [85,86] and evolutionary change [87,88], our findings suggest that an immediate challenge is to determine the circumstances under which species exhibit compensatory responses (e.g. [21]) and whether or not the presence of compensatory processes refine understanding of biodiversity–function relations. In the meantime, we advocate that management efforts should prioritize the conservation of species based on their contribution to maintaining multiple ecosystem processes and functions. In doing so, it will be important to recognize that the compensatory capacity of a community is dynamic and will respond to changes in biological and environmental context [89] that, in turn, are likely to lead to a wider range of ecological outcomes than are presently appreciated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Brochain, S. M. Yunus, D. Wohlgemuth, N. Pratt, M. Beverley-Smith, A. Billen and C. L. Wood (University of Southampton) for laboratory and field assistance and E.M.S Woodward (Plymouth Marine Laboratory) for bromide and nutrient analysis.

Data accessibility

All data are provided in the electronic supplementary material, Data S1.

Authors' contributions

M.S.T., J.A.G. and M.S. conceived the ideas and designed the study. M.S.T. performed the experiments, collected the data and completed all statistical analyses. M.S.T., J.A.G. and M.S. led the writing of the manuscript and all authors contributed critically to subsequent drafts and gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Funding

Supported by a scholarship (awarded to M.S.T., grant reference NE/L002531/1) co-funded by the Southampton Partnership for Innovative Training of Future Investigators Researching the Environment (SPITFIRE, an NERC Doctoral Training Partnership) and the Centre for Environment, Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas, reference DP371C). C.G., S.G.B., R.P., J.A.G. and M.S acknowledge Work Package 2 of the Shelf Sea Biogeochemistry Programme (NE/K001906/1, 2011–2017), jointly funded by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) in the UK.

References

- 1.Ernest SKM, Brown JH. 2001. Homeostasis and compensation: the role of species and resources in ecosystem stability. Ecology 82, 2118–2132. ( 10.2307/2680220) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klug JL, Fischer JM, Ives AR, Dennis B. 2000. Compensatory dynamics in planktonic community responses to pH perturbations. Ecology 81, 387–398. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hector A, et al. 2010. General stabilizing effects of plant diversity on grassland productivity through population asynchrony and overyielding. Ecology 91, 2213–2220. ( 10.1890/09-1162.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bai Y, Han X, Wu J, Chen Z, Li L. 2004. Ecosystem stability and compensatory effects in the inner Mongolia grassland. Nature 431, 181–184. ( 10.1038/nature02850) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pan Q, et al. 2016. Effects of functional diversity loss on ecosystem functions are influenced by compensation. Ecology 97, 2293–2302. ( 10.1002/ecy.1460) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruesink JL, Srivastava DS. 2001. Numerical and per capita responses to species loss: mechanisms maintaining ecosystem function in a community of stream insect detritivores. Oikos 93, 221–234. ( 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2001.930206.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghedini G, Russell BD, Connell SD. 2015. Trophic compensation reinforces resistance: herbivory absorbs the increasing effects of multiple disturbances. Ecol. Lett. 18, 182–187. ( 10.1111/ele.12405) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pickett STA, White PS. 1985. The ecology of natural disturbance and patch dynamics, 472 pp. Orlando, FL: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paine RT, Tegner MJ, Johnson EA. 1998. Compounded perturbations yield ecological surprises. Ecosystems 1, 535–545. ( 10.1007/s100219900049) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Connell SD, Kroeker KJ, Fabricius KE, Kline DI, Russell BD. 2013. The other ocean acidification problem: CO2 as a resource among competitors for ecosystem dominance. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 368, 20120442 ( 10.1098/rstb.2012.0442) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sih A. 2013. Understanding variation in behavioural responses to human-induced rapid environmental change: a conceptual overview. Anim. Behav. 85, 1077–1088. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.02.017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sih A, Ferrari MC, Harris DJ. 2011. Evolution and behavioural responses to human-induced rapid environmental change. Evol. Appl. 4, 367–387. ( 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2010.00166.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuomainen U, Candolin U. 2011. Behavioural responses to human-induced environmental change. Biol. Rev. 86, 640–657. ( 10.1111/j.1469-185X.2010.00164.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Candolin U, Wong BB. 2012. Behavioural responses to a changing world: mechanisms and consequences. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fricke EC, Tewksbury JJ, Rogers HS. 2018. Defaunation leads to interaction deficits, not interaction compensation, in an island seed dispersal network. Global Change Biol. 24, e190–e200. ( 10.1111/gcb.13832) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kiessling W, Aberhan M, Brenneis B, Wagner PJ. 2007. Extinction trajectories of benthic organisms across the Triassic–Jurassic boundary. Palaeogeog. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 244, 201–222. ( 10.1016/j.palaeo.2006.06.029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tu C, Chen ZQ, Harper DA. 2016. Permian–Triassic evolution of the Bivalvia: extinction-recovery patterns linked to ecologic and taxonomic selectivity. Palaeogeog. Palaeoclim. Palaeoecol. 459, 53–62. ( 10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.06.042) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lotze HK, et al. 2006. Depletion, degradation, and recovery potential of estuaries and coastal seas. Science 312, 1806–1809. ( 10.1126/science.1128035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pimiento C, Griffin JN, Clements CF, Silvestro D, Varela S, Uhen MD, Jaramillo C. 2017. The Pliocene marine megafauna extinction and its impact on functional diversity. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 1, 1100–1106. ( 10.1038/s41559-017-0223-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Aberhan M, Kiessling W. 2015. Persistent ecological shifts in marine molluscan assemblages across the end-Cretaceous mass extinction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7207–7212. ( 10.1073/pnas.1422248112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heilpern SA, Weeks BC, Naeem S. 2018. Predicting ecosystem vulnerability to biodiversity loss from community composition. Ecology 99, 1099–1107. ( 10.1002/ecy.2219) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cardinale BJ, et al. 2012. Biodiversity loss and its impact on humanity. Nature 486, 59–67. ( 10.1038/nature11148) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cardinale BJ, Matulich KL, Hooper DU, Byrnes JE, Duffy E, Gamfeldt L, Balvanera P, O'Connor MI, Gonzalez A. 2011. The functional role of producer diversity in ecosystems. Am. J. Bot. 98, 572–592 ( 10.3732/ajb.1000364). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez A, Mouquet N, Loreau M. 2009. Biodiversity as spatial insurance: the effects of habitat fragmentation and dispersal on ecosystem functioning. In Biodiversity, ecosystem functioning, and human wellbeing: an ecological and economic perspective (eds Naeem S, Bunker DE, Hector A, Loreau M, Perrings C), pp. 134–146. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thomsen MS, Garcia C, Bolam SG, Parker R, Godbold JA, Solan M. 2017. Consequences of biodiversity loss diverge from expectation due to post-extinction compensatory responses. Sci. Rep. 7, 43695 ( 10.1038/srep43695) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Solan M, Cardinale BJ, Downing AL, Engelhardt KA, Ruesink JL, Srivastava DS. 2004. Extinction and ecosystem function in the marine benthos. Science 306, 1177–1180. ( 10.1126/science.1103960) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McIntyre PB, Jones LE, Flecker AS, Vanni MJ. 2007. Fish extinctions alter nutrient recycling in tropical freshwaters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 4461–4466. ( 10.1073/pnas.0608148104) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker BH. 1992. Biodiversity and ecological redundancy. Conserv. Biol. 6, 18–23. ( 10.1046/j.1523-1739.1992.610018.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawton JH, Brown VK. 1994. Redundancy in ecosystems. In Biodiversity and ecosystem function (eds. SchulzeD ED, Mooney HA), pp. 255–270. Berlin, Germany: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapin FS, et al. 2000. Consequences of changing biodiversity. Nature 405, 234–242. ( 10.1038/35012241) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bihn JH, Gebauer G, Brandl R. 2010. Loss of functional diversity of ant assemblages in secondary tropical forests. Ecology 91, 782–792. ( 10.1890/08-1276.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naeem S, Li S. 1997. Biodiversity enhances ecosystem reliability. Nature 390, 507–509. ( 10.1038/37348) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yachi S, Loreau M. 1999. Biodiversity and ecosystem productivity in a fluctuating environment: the insurance hypothesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 1463–1468. ( 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blüthgen N, et al. 2016. Land use imperils plant and animal community stability through changes in asynchrony rather than diversity. Nat. Commun. 7, 10697 ( 10.1038/ncomms10697) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Houadria M, Blüthgen N, Salas-Lopez A, Schmitt MI, Arndt J, Schneider E, Orivel J, Menzel F. 2016. The relation between circadian asynchrony, functional redundancy, and trophic performance in tropical ant communities. Ecology 97, 225–235. ( 10.1890/14-2466.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoover DL, Knapp AK, Smith MD. 2014. Resistance and resilience of a grassland ecosystem to climate extremes. Ecology 95, 2646–2656. ( 10.1890/13-2186.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hallett LM, et al. 2014. Biotic mechanisms of community stability shift along a precipitation gradient. Ecology 95, 1693–1700. ( 10.1890/13-0895.1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davies TW, Jenkins SR, Kingham R, Hawkins SJ, Hiddink JG. 2012. Extirpation-resistant species do not always compensate for the decline in ecosystem processes associated with biodiversity loss. J. Ecol. 100, 1475–1481. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2012.02012.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reich PB, Tilman D, Isbell F, Mueller K, Hobbie SE, Flynn DF, Eisenhauer N. 2012. Impacts of biodiversity loss escalate through time as redundancy fades. Science 336, 589–592. ( 10.1126/science.1217909) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Larsen TH, Williams NM, Kremen C. 2005. Extinction order and altered community structure rapidly disrupt ecosystem functioning. Ecol. Lett. 8, 538–547. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00749.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Séguin A, Harvey É, Archambault P, Nozais C, Gravel D. 2014. Body size as a predictor of species loss effect on ecosystem functioning. Sci. Rep. 4, 4616 ( 10.1038/srep04616) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hull P. 2015. Life in the aftermath of mass extinctions. Curr. Biol. 25, R941–R952. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2015.08.053) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Payne JL, Bush AM, Heim NA, Knope ML, McCauley DJ. 2016. Ecological selectivity of the emerging mass extinction in the oceans. Science 353, 1284–1286. ( 10.1126/science.aaf2416) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brose U, Hillebrand H. 2016. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning in dynamic landscapes. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 365, 49–60. ( 10.1098/rstb.2015.0267) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ives AR, Klug JL, Gross K. 2000. Stability and species richness in complex communities. Ecol. Lett. 3, 399–411. ( 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2000.00144.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Loreau M, Mouquet N, Gonzalez A. 2003. Biodiversity as spatial insurance in heterogeneous landscapes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 12 765–12 770. ( 10.1073/pnas.2235465100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Biles CL, Solan M, Isaksson I, Paterson DM, Emes C, Raffaelli DG. 2003. Flow modifies the effect of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning: an in situ study of estuarine sediments. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 285, 165–177. ( 10.1016/S0022-0981(02)00525-7) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamanaka T, Raffaelli D, White PC. 2010. Physical determinants of intertidal communities on dissipative beaches: implications of sea-level rise. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 88, 267–278. ( 10.1016/j.ecss.2010.03.023) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wohlgemuth D, Solan M, Godbold JA. 2016. Specific arrangements of species dominance can be more influential than evenness in maintaining ecosystem process and function. Sci. Rep. 6, 39325 ( 10.1038/srep39325) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Solan M, Wigham BD, Hudson IR, Kennedy R, Coulon CH, Norling K, Nilsson HC, Rosenberg R. 2004. In situ quantification of bioturbation using time lapse fluorescent sediment profile imaging (f SPI), luminophore tracers and model simulation. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 271, 1–12. ( 10.3354/meps271001) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hale R, Mavrogordato MN, Tolhurst TJ, Solan M. 2014. Characterizations of how species mediate ecosystem properties require more comprehensive functional effect descriptors. Sci. Rep. 4, 6463 ( 10.1038/srep06463) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Forster S, Glud RN, Gundersen JK, Huettel M. 1999. In situ study of bromide tracer and oxygen flux in coastal sediments. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 49, 813–827. ( 10.1006/ecss.1999.0557) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Smith GM. 2007. Analysing ecological data. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pinheiro JC, Bates DM. 2000. Mixed-effects models in S and S-plus. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zuur AF, Ieno EN, Walker NJ, Saveliev AA, Smith GM. 2009. Mixed effects models and extensions in ecology with R. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- 56.R Core Team. 2016. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; https://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, Sarkar D, R Core Team. 2017. nlme: Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models (R package version 3.1-128, 2016). http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=nlme.

- 58.Bunker DE, DeClerck F, Bradford JC, Colwell RK, Perfecto I, Phillips OL, Sankaran M, Naeem S. 2005. Species loss and aboveground carbon storage in a tropical forest. Science 310, 1029–1031. ( 10.1126/science.1117682) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Langenheder S, Bulling MT, Solan M, Prosser JI. 2010. Bacterial biodiversity-ecosystem functioning relations are modified by environmental complexity. PLOS ONE 5, e10834 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0010834) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Langenheder S, Bulling MT, Prosser JI, Solan M. 2012. Role of functionally dominant species in varying environmental regimes: evidence for the performance-enhancing effect of biodiversity. BMC Ecol. 12, 14 ( 10.1186/1472-6785-12-14) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vellend M, et al. 2013. Global meta-analysis reveals no net change in local-scale plant biodiversity over time. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 110, 19 456–19 459. ( 10.1073/pnas.1312779110) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vellend M, et al. 2017. Estimates of local biodiversity change over time stand up to scrutiny. Ecology 98, 583–590. ( 10.1002/ecy.1660) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Orwin KH, Ostle N, Wilby A, Bardgett RD. 2014. Effects of species evenness and dominant species identity on multiple ecosystem functions in model grassland communities. Oecologia 174, 979–992. ( 10.1007/s00442-013-2814-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wilsey BJ, Potvin C. 2000. Biodiversity and ecosystem functioning: importance of species evenness in an old field. Ecology 81, 887–892. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ieno EN, Solan M, Batty P, Pierce GJ. 2006. How biodiversity affects ecosystem functioning: roles of infaunal species richness, identity and density in the marine benthos. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 311, 263–272. ( 10.3354/meps311263) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schmitz M, Flynn DF, Mwangi PN, Schmid R, Scherer-Lorenzen M, Weisser WW, Schmid B (2013) Consistent effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning under varying density and evenness. Folia Geobot. 48, 335–353. ( 10.1007/s12224-013-9177-x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.McKie BG, Woodward G, Hladyz S, Nistorescu M, Preda E, Popescu C, Giller PS, Malmqvist B. 2008. Ecosystem functioning in stream assemblages from different regions: contrasting responses to variation in detritivore richness, evenness and density. J. Anim. Ecol. 77, 495–504. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2008.01357.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reiss J, Bailey RA, Perkins DM, Pluchinotta A, Woodward G. 2011. Testing effects of consumer richness, evenness and body size on ecosystem functioning. J. Anim. Ecol. 80, 1145–1154. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01857.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Winfree R, Fox JW, Williams NM, Reilly JR, Cariveau DP. 2015. Abundance of common species, not species richness, drives delivery of a real-world ecosystem service. Ecol. Lett. 18, 626–635. ( 10.1111/ele.12424) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hillebrand H, et al. 2018. Biodiversity change is uncoupled from species richness trends: consequences for conservation and monitoring. J. Appl. Ecol. 55, 169–184. ( 10.1111/1365-2664.12959) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bracken ME, Friberg SE, Gonzalez-Dorantes CA, Williams SL. 2008. Functional consequences of realistic biodiversity changes in a marine ecosystem. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 924–928. ( 10.1073/pnas.0704103105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Naeem S. 2008. Advancing realism in biodiversity research. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 414–416. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2008.05.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Srivastava DS, Vellend M. 2005. Biodiversity-ecosystem function research: is it relevant to conservation? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 36, 267–294. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.102003.152636) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Albert CH, Thuiller W, Yoccoz NG, Soudant A, Boucher F, Saccone P, Lavorel S. 2010. Intraspecific functional variability: extent, structure and sources of variation. J. Ecol. 98, 604–613. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2010.01651.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dunhill AM, Foster WJ, Sciberras J, Twitchett RJ. 2018. Impact of the Late Triassic mass extinction on functional diversity and composition of marine ecosystems. Palaeontology 61, 133–148. ( 10.1111/pala.12332) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nicholls RJ, et al. 2018. Stabilization of global temperature at 1.5°C and 2.0°C: implications for coastal areas. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 376, 20160448 ( 10.1098/rsta.2016.0448) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Godbold JA, Solan M. 2009. Relative importance of biodiversity and the abiotic environment in mediating an ecosystem process. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 396, 273–282. ( 10.3354/meps08401) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Somero GN. 2010. The physiology of climate change: how potentials for acclimatization and genetic adaptation will determine ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. J. Exp. Biol. 213, 912–920. ( 10.1242/jeb.037473) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Godbold JA, Solan M. 2013. Long-term effects of warming and ocean acidification are modified by seasonal variation in species responses and environmental conditions. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 368, 20130186 ( 10.1098/rstb.2013.0186) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lembrechts JJ, De Boeck HJ, Liao J, Milbau A, Nijs I.. 2018. Effects of species evenness can be derived from species richness–ecosystem functioning relationships. Oikos 127, 337–344. ( 10.1111/oik.04786) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Naeem S, Wright JP. 2003. Disentangling biodiversity effects on ecosystem functioning: deriving solutions to a seemingly insurmountable problem. Ecol. Lett. 6, 567–579. ( 10.1046/j.1461-0248.2003.00471.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Loreau M, Mazancourt C. 2013. Biodiversity and ecosystem stability: a synthesis of underlying mechanisms. Ecol. Lett. 16, 106–115. ( 10.1111/ele.12073) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Huijbers CM, Schlacher TA, Schoeman DS, Olds AD, Weston MA, Connolly RM. 2015. Limited functional redundancy in vertebrate scavenger guilds fails to compensate for the loss of raptors from urbanized sandy beaches. Divers. Distrib. 21, 55–63. ( 10.1111/ddi.12282) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hale R, Godbold JA, Sciberras M, Dwight J, Wood C, Hiddink JG, Solan M. 2017. Mediation of macronutrients and carbon by post-disturbance shelf sea sediment communities. Biogeochemistry 135, 121–133. ( 10.1007/s10533-017-0350-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Torres-Dowdall J, Handelsman CA, Ruell EW, Auer SK, Reznick DN, Ghalambor CK. 2012. Fine-scale local adaptation in life histories along a continuous environmental gradient in Trinidadian guppies. Funct. Ecol. 26, 616–627. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2012.01980.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wong B, Candolin U. 2015. Behavioral responses to changing environments. Behav. Ecol. 26, 665–673. ( 10.1093/beheco/aru183) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pfennig DW, Wund MA, Snell-Rood EC, Cruickshank T, Schlichting CD, Moczek AP. 2010. Phenotypic plasticity's impacts on diversification and speciation. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25, 459–467. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2010.05.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.West-Eberhard MJ. 2005. Developmental plasticity and the origin of species differences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102(Suppl. 1), 6543–6549. ( 10.1073/pnas.0501844102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fetzer I, Johst K, Schäwe R, Banitz T, Harms H, Chatzinotas A. 2015. The extent of functional redundancy changes as species' roles shift in different environments. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 14 888–14 893. ( 10.1073/pnas.1505587112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are provided in the electronic supplementary material, Data S1.