Abstract

To promote uniformity in measuring adherence to the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement, a reporting guideline for diagnostic and prognostic prediction model studies, and thereby facilitate comparability of future studies assessing its impact, we transformed the original 22 TRIPOD items into an adherence assessment form and defined adherence scoring rules. TRIPOD specific challenges encountered were the existence of different types of prediction model studies and possible combinations of these within publications. More general issues included dealing with multiple reporting elements, reference to information in another publication, and non-applicability of items. We recommend our adherence assessment form to be used by anyone (eg, researchers, reviewers, editors) evaluating adherence to TRIPOD, to make these assessments comparable. In general, when developing a form to assess adherence to a reporting guideline, we recommend formulating specific adherence elements (if needed multiple per reporting guideline item) using unambiguous wording and the consideration of issues of applicability in advance.

Keywords: reporting guideline, tripod, prediction model, adherence, risk score

Article summary.

The original 22 items of the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement were transformed into a systematic and transparent adherence assessment form including scoring rules, for use by anyone evaluating adherence to TRIPOD.

During the development, the adherence assessment form was extensively discussed, piloted and refined.

Recommendations for developing and using a standardised form for measuring adherence to a reporting guideline were formulated based on challenges encountered.

Background

Incomplete reporting of research is considered to be a form of research waste.1 2 To eventually implement research results in clinical guidelines and daily practice, one needs sufficient details regarding the research to critically appraise the methods and interpret study results in the context of existing evidence.3–6

To improve the reporting of health research, many reporting guidelines have been developed for various types of studies, such as the CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement, STAndards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) statement, Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement, STrengthening the Reporting of OBservational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement, REporting recommendations for tumour MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK) and the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement.7–15 A large number of reporting guidelines can be found on the website of the Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research (EQUATOR) Network, an international collaboration that supports the development and dissemination of reporting guidelines in order to achieve accurate, complete and transparent health research reporting (www.equator-network.org).4 5

Publishing a reporting guideline followed by some form of recommendation or journal endorsement is not enough for researchers to adhere to reporting guidelines - a more active implementation is usually required.5 In their guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines, Moher and colleagues proposed 18 steps to be taken in the development of a reporting guideline, including several post-publication activities.6 One of these activities is to evaluate the actual adherence and thus use of a reporting guideline over time, as has been carried out for CONSORT, STARD and PRISMA.16–23 In multiple evaluations of the same guideline, different approaches to extract, score and record adherence to items of the guideline were seen, making comparisons difficult.17 21–23 For example, a systematic review of studies assessing adherence to STARD found that the number of items assessed was inconsistent and the criteria required for considering the reporting of an item to be complete differed between adherence evaluations. In addition, not all studies performed quantitative scoring, preventing an objective comparison of adherence between studies.17 A systematic adherence-scoring-system is needed to enhance objectivity and to ensure consistent measurement of adherence to a reporting guideline. A unique assessment form for adherence evaluations would reduce variation in the number of items being evaluated, how multicomponent items are being handled, and the scoring rules applied (on item level and overall adherence), and thereby facilitate comparison of reporting between different fields and over time.

As the TRIPOD statement was only recently published (2015), its impact has not been assessed yet. However, recently a baseline measurement was performed to evaluate the extent to which prediction model studies before the introduction of TRIPOD reported each of the TRIPOD items.24 Based on this, the TRIPOD steering committee aimed to develop a systematic and transparent adherence-scoring-system to be used by other researchers to facilitate and ensure uniformity in measuring adherence to TRIPOD in future studies. We also provide general recommendations on developing an adherence assessment form for other reporting guidelines.

Developing the TRIPOD adherence assessment form

Our adherence assessment form contains all 22 main items of the original TRIPOD statement. Ten of these TRIPOD items actually comprise two (items 3, 4, 6, 7, 14, 15 and 19), three (items 5 and 13) or five (item 10) sub items (denoted by a, b, c, etc; see box 1).15 25 For our TRIPOD adherence assessment form, we further specified these original TRIPOD items (main or sub items, hereafter referred to as items) into so-called adherence elements. When a TRIPOD item contains multiple elements to report, multiple adherence elements were used. For example, for TRIPOD item 5a ‘Specify key elements of the study setting (eg, primary care, secondary care, general population) including number and location of centres.’ we defined three adherence elements to record information regarding (1) setting, (2) number and (3) location of centres.

Box 1. Items of the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement.

Title and abstract

Title (D; V): identify the study as developing and/or validating a multivariable prediction model, the target population and the outcome to be predicted.

Abstract (D; V): provide a summary of objectives, study design, setting, participants, sample size, predictors, outcome, statistical analysis, results and conclusions.

Introduction

-

Background and objectives:

(D; V) Explain the medical context (including whether diagnostic or prognostic) and rationale for developing or validating the multivariable prediction model, including references to existing models.

(D; V) Specify the objectives, including whether the study describes the development or validation of the model or both.

Methods

-

Source of data:

(D; V) Describe the study design or source of data (eg, randomised trial, cohort or registry data), separately for the development and validation data sets, if applicable.

(D; V) Specify the key study dates, including start of accrual, end of accrual and if applicable, end of follow-up.

-

Participants:

(D; V) Specify key elements of the study setting (eg, primary care, secondary care or general population) including number and location of centres.

(D; V) Describe eligibility criteria for participants.

(D; V) Give details of treatments received, if relevant.

-

Outcome:

(D; V) Clearly define the outcome that is predicted by the prediction model, including how and when assessed.

(D; V) Report any actions to blind assessment of the outcome to be predicted.

-

Predictors:

(D; V) Clearly define all predictors used in developing or validating the multivariable prediction model, including how and when they were measured.

(D; V) Report any actions to blind assessment of predictors for the outcome and other predictors.

Sample size (D; V): explain how the study size was arrived at.

Missing data (D; V): describe how missing data were handled (eg, complete-case analysis, single imputation or multiple imputation) with details of any imputation method.

-

Statistical analysis methods:

(D) Describe how predictors were handled in the analyses.

(D) Specify type of model, all model-building procedures (including any predictor selection) and method for internal validation.

(V) For validation, describe how the predictions were calculated.

(D; V) Specify all measures used to assess model performance and, if relevant, to compare multiple models.

(V) Describe any model updating (eg, recalibration) arising from the validation, if done.

Risk groups (D; V): provide details on how risk groups were created, if done.

Development vs. validation (V): for validation, identify any differences from the development data in setting, eligibility criteria, outcome and predictors.

Results

-

Participants:

(D; V) Describe the flow of participants through the study, including the number of participants with and without the outcome and, if applicable, a summary of the follow-up time. A diagram may be helpful.

(D; V) Describe the characteristics of the participants (basic demographics, clinical features and available predictors), including the number of participants with missing data for predictors and outcome.

(V) For validation, show a comparison with the development data of the distribution of important variables (demographics, predictors and outcome).

-

Model development:

(D) Specify the number of participants and outcome events in each analysis.

(D) If done, report the unadjusted association between each candidate predictor and outcome.

-

Model specification:

(D) Present the full prediction model to allow predictions for individuals (ie, all regression coefficients and model intercept or baseline survival at a given time point).

(D) Explain how to use the prediction model.

Model performance (D; V): report performance measures (with CIs) for the prediction model.

Model-updating (V): if done, report the results from any model updating (ie, model specification and model performance).

Discussion

Limitations (D; V): discuss any limitations of the study (such as non-representative sample, few events per predictor, missing data).

-

Interpretation:

(V) For validation, discuss the results with reference to performance in the development data and any other validation data.

(D; V) Give an overall interpretation of the results, considering objectives, limitations, results from similar studies and other relevant evidence.

Implications (D; V): discuss the potential clinical use of the model and implications for future research.

Other information

Supplementary information (D; V): provide information about the availability of supplementary resources, such as study protocol, Web calculator and data sets.

Funding (D; V): give the source of funding and the role of the funders for the present study.

D; V: item relevant to both development and external validation; D: item only relevant to development; V: item only relevant to external validation

We further distinguished four types of prediction model studies: model development, external validation, incremental value of adding one or more predictor(s) to an existing model, or a combination of development and external validation of the same model. Six TRIPOD items only apply to development of a prediction model (10a, 10b, 14a, 14b, 15a and 15b) and six only to external validation (10 c, 10e, 12, 13 c, 17 and 19a) (box 1).15 25 All TRIPOD items, except for TRIPOD item 17, were considered applicable to incremental value reports. As not all TRIPOD items apply to all four types of prediction model studies, we defined four versions of the adherence assessment form, depending on whether a report described model development, external validation, a combination of these, or incremental value. If a report addressed both the development and external validation of the same prediction model, the reporting of either was assessed separately and subsequently combined for each adherence element.

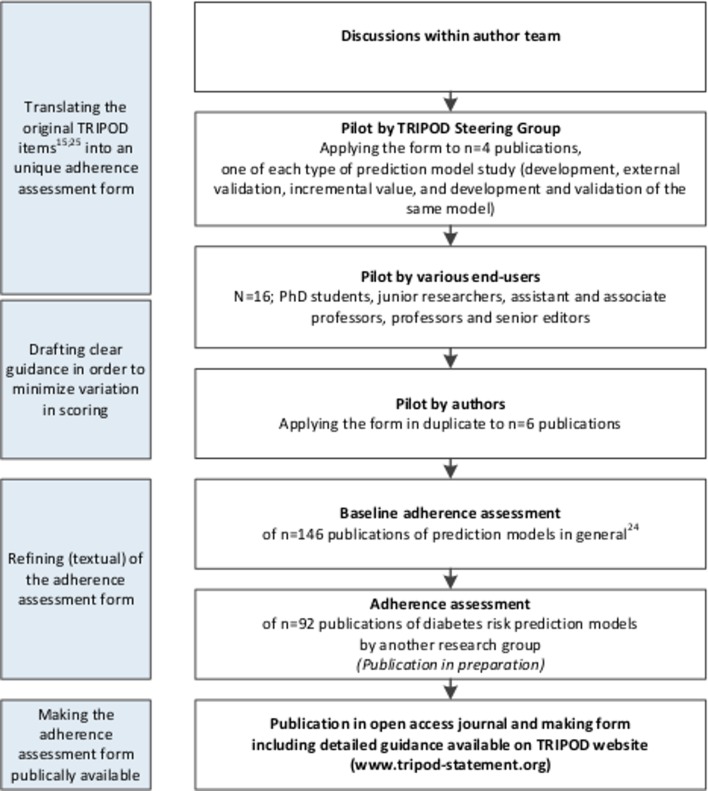

There were several stages in the process of developing the adherence assessment form (figure 1). All authors commented on the first version of the form. A revised version was then piloted by four authors representing the TRIPOD steering committee (JBR, GSC, DGA and KGMM). Based on their experiences adaptations to the form were made, mainly in the number and wording of the adherence assessment elements. Subsequently, the form was piloted by a group of various end-users consisting of PhD students, junior researchers, assistant and associate professors, professors and senior editors (n=16). Thereafter, three other authors (PH, JAAGD and RP) used the next version of the form when assessing six studies in duplicate. Items that led to disagreement or uncertainty more than once (items 2, 4b, 5a, 5c, 6a, 6b, 7b, 8, 10a, 10b, 10d, 11, 13a, 13b, 19 and 20) were discussed within the entire author team, leading to the final version of the form that was used to assess adherence to TRIPOD in a set of 146 publications.24 The form was also used by another group assessing adherence to TRIPOD in prognostic models for diabetes (publication in preparation). Challenges encountered and discussions held in this stage, only led to textual refinements to the form. Our final adherence assessment form, including considerations and guidance regarding scoring and calculations, is summarised in online supplementary file 1. It can also be found on the website of the TRIPOD statement (www.tripod-statement.org).

Figure 1.

Process of developing the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) adherence assessment form with the aim of reducing unnecessary variation in scoring quality of reporting of prediction model studies based on TRIPOD.

bmjopen-2018-025611supp001.pdf (710.4KB, pdf)

Using the TRIPOD adherence assessment form

Scoring adherence per TRIPOD item

First, one has to judge for each adherence element whether the requested information is available in a report. The elements are formulated as statements that can be answered with ‘yes ‘or ‘no’ (see online supplementary file 1). For some elements it may be acceptable if authors in their report make explicit reference to another publication (ie, explicitly mention that the information of that adherence element is described somewhere else). This is denoted by the answer option ‘referenced’. For adherence elements that do not apply to a specific situation (for example reporting of follow-up (item 4b) might be not relevant in a diagnostic prediction model study), there is the answer option ‘not applicable’.

The next step is to determine the adherence of a report per TRIPOD item. In general, if the answer to all adherence elements of a particular TRIPOD item is scored ‘yes’ or ‘not applicable’, the TRIPOD item is considered as adhered. In some situations a different scoring rule is used, which is described in the adherence assessment form for the corresponding items.

Overall adherence to TRIPOD

A report’s overall TRIPOD adherence score is calculated by dividing the sum of the adhered TRIPOD items by the total number of applicable TRIPOD items. Since some TRIPOD items are not applicable to all four types of prediction model studies, this total varies. The total number of applicable TRIPOD items for development is 30, for external validation 30, for incremental value 35 and for development and external validation of the same model 36. In addition, five TRIPOD items (5c, 10e, 11, 14b and 17) might not be applicable for specific reports (online supplementary file 1).

If one reviews multiple prediction model studies on their adherence to TRIPOD, overall adherence per TRIPOD item can be calculated by dividing the number of studies that adhered to a specific TRIPOD item by the number of studies in which the specific TRIPOD item was applicable.

Recommendations for developing and using a standardised form for assessing adherence to a reporting guideline

As described earlier, during the process of designing this adherence assessment form we extensively discussed, piloted and refined our methods. One issue specific to TRIPOD we discussed, were the different types of prediction model studies (development, external validation and incremental value) that can be found in various combinations within publications. As not all TRIPOD items apply to all types of prediction model studies, overall adherence scores need to be calculated per type of prediction model study.

A more general issue is how to deal with items containing several reporting elements. For TRIPOD we decided to determine adherence to a specific item by requiring complete information on all elements of that item. Hence, we created multiple adherence elements per TRIPOD item, as necessary.

Another issue with regard to scoring adherence is how to handle (elements of) TRIPOD items that were not applicable for a specific prediction model study. This not only concerns the judgements at the level of adherence elements, but also the calculations of adherence per TRIPOD item and of the overall adherence. Overall adherence, in the form of a percentage of items adhered to, requires a clear denominator of total number of items one can adhere to. One has to decide whether to take items that are considered not applicable into account in the numerator as well as in the denominator. Determining applicability is subjective and requires interpretation. In our experience, items for which interpretation was needed, sometimes indicated by phrases like ‘if relevant’ or ‘if applicable’, were the most difficult ones to score and these items are a potential threat to inter-assessor agreement.

We present our recommendations for developing and using a standardised form for measuring adherence to a reporting guideline in box 2.

Box 2. Recommendations for developing and using a standardised form for measuring adherence to a reporting guideline.

Decide which items are applicable to the set of publications of which you are going to measure adherence to the reporting guideline.

Split items of a reporting guideline that consist of several sub items and elements into separate adherence elements to enable more detailed judgement of reporting.

Pay attention on explicit wording of adherence elements, to make them as objective as possible.

Determine for which items reference to information in another publication (instead of explicit reporting of that information) is acceptable for adherence.

-

Define how to handle items that are not applicable to a specific report:

Agree on which items this may concern and in what specific situations an adherence element or item could be considered as not applicable.

Decide how to incorporate the ‘not applicable’ scores’ in determining adherence, per item as well as overall.

-

Provide the final tailored adherence assessment form with clear guidance about the procedure and pilot the document in a small number of studies with several assessors:

If there is poor agreement, discuss and refine the document.

With good agreement, complete the assessment for all publications.

Abstract and document information separately for each adherence element. This creates flexibility, as one is able to decide post hoc which elements to incorporate in calculating adherence per item, and thus overall adherence.

Concluding remarks

Evaluation of the impact of a reporting guideline should be as standardised and uniform as possible. However, this is not straightforward as reporting guidelines are usually not developed as an instrument to measure completeness of reporting. We present an adherence assessment form that facilitates uniformity in measuring adherence to TRIPOD. The form is provided in online supplementary file 1 and on the website of the TRIPOD statement (www.tripod-statement.org). Although, when developing the form, we had researchers evaluating quality of reporting in mind as target users, it can also be used by others interested in assessing adherence to TRIPOD, like authors, journal reviewers and editors. We would like to emphasise that our form should be used for assessing adherence to TRIPOD and not for assessing quality of prediction model studies (for which the Prediction model study Risk Of Bias Assessment Tool (PROBAST) was developed; www.probast.org).

We did not perform formal user testing or reliability assessments, however we refined our adherence assessment form based on extensive discussions and pilot assessments within the author team, as well as by other potential users.

We advise developers of reporting guidelines to consider adherence issues and impact evaluation early in the process of guideline development, as also recommended by Moher and colleagues.6 More specifically, attention should be paid to explicit wording of items, to make them as objective as possible and facilitate the interpretation of applicability and relevance.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors were involved in designing, discussing and piloting the adherence assessment form. PH wrote the first draft of the manuscript, which was revised by KGMM and LH. Subsequently, JAAGD, RP, RJPMS, JBR, and GSC provided feedback on the draft. All authors approved the final version of the submitted manuscript, except for DGA, who deceased on 3 June 2018, before reading the final version.

Funding: GSC was supported by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, Oxford. KGMM received a grant from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (ZONMW 918.10.615 and 91208004).

Competing interests: DGA, JBR, GSC, and KGMM are members of the TRIPOD Group.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The adherence assessment form that was developed is available at the TRIPOD website (www.tripod-statement.org).

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Avoidable waste in the production and reporting of research evidence. Lancet 2009;374:86–9. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60329-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Glasziou P, Altman DG, Bossuyt P, et al. Reducing waste from incomplete or unusable reports of biomedical research. Lancet 2014;383:267–76. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62228-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Glasziou P, Meats E, Heneghan C, et al. What is missing from descriptions of treatment in trials and reviews? BMJ 2008;336:1472–4. 10.1136/bmj.39590.732037.47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simera I, Altman DG, Moher D, et al. Guidelines for reporting health research: the EQUATOR network’s survey of guideline authors. PLoS Med 2008;5:e139 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Simera I, Moher D, Hirst A, et al. Transparent and accurate reporting increases reliability, utility, and impact of your research: reporting guidelines and the EQUATOR Network. BMC Med 2010;8:24 10.1186/1741-7015-8-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Moher D, Schulz KF, Simera I, et al. Guidance for developers of health research reporting guidelines. PLoS Med 2010;7:e1000217 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Begg C, Cho M, Eastwood S, et al. Improving the quality of reporting of randomised controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA 1996;276:637–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG. The CONSORT statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomised trials. Lancet 2001;357:1191–4. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04337-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Schulz KF. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. Ann Intern Med 2010;152:726–32. 10.7326/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ 2015;351:h5527 10.1136/bmj.h5527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: The STARD Initiative. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:40–4. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 2009;6:e1000097 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:573–7. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, et al. REporting recommendations for tumour MARKer prognostic studies (REMARK). Br J Cancer 2005;93:387–91. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, et al. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:55–63. 10.7326/M14-0697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smidt N, Rutjes AW, van der Windt DA, et al. The quality of diagnostic accuracy studies since the STARD statement: has it improved? Neurology 2006;67:792–7. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000238386.41398.30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Korevaar DA, van Enst WA, Spijker R, et al. Reporting quality of diagnostic accuracy studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis of investigations on adherence to STARD. Evid Based Med 2014;19:47–54. 10.1136/eb-2013-101637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Korevaar DA, Wang J, van Enst WA, et al. Reporting diagnostic accuracy studies: some improvements after 10 years of STARD. Radiology 2015;274:781–9. 10.1148/radiol.14141160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kane RL, Wang J, Garrard J. Reporting in randomised clinical trials improved after adoption of the CONSORT statement. J Clin Epidemiol 2007;60:241–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hopewell S, Dutton S, Yu LM, et al. The quality of reports of randomised trials in 2000 and 2006: comparative study of articles indexed in PubMed. BMJ 2010;340:c723 10.1136/bmj.c723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Turner L, Shamseer L, Altman DG, et al. Consolidated standards of reporting trials (CONSORT) and the completeness of reporting of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) published in medical journals. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;11:Mr000030 10.1002/14651858.MR000030.pub2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Samaan Z, Mbuagbaw L, Kosa D, et al. A systematic scoping review of adherence to reporting guidelines in health care literature. J Multidiscip Healthc 2013;6:169–88. 10.2147/JMDH.S43952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pussegoda K, Turner L, Garritty C, et al. Systematic review adherence to methodological or reporting quality. Syst Rev 2017;6:131 10.1186/s13643-017-0527-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Heus P, Damen J, Pajouheshnia R, et al. Poor reporting of multivariable prediction model studies: towards a targeted implementation strategy of the TRIPOD statement. BMC Med 2018;16:120 10.1186/s12916-018-1099-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, et al. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med 2015;162:W1–73. 10.7326/M14-0698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-025611supp001.pdf (710.4KB, pdf)