Abstract

Objective

A retrospective case–control study was conducted to evaluate whether frequent binge drinking between the age of 18 and 25 years was a risk factor for alcohol dependence in adulthood.

Setting

The Department of Addictive Medicine and the Clinical Investigation Center of a university hospital in France.

Participants

Cases were alcohol-dependent patients between 25 and 45 years and diagnosed by a psychiatrist. Consecutive patients referred to the Department of Addictive Medicine of a university hospital between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2017 for alcohol dependence were included in the study. Controls were non-alcohol-dependent adults, defined according to an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test score of less than 8, and were matched on age and sex with cases. Data on sociodemographics, behaviour and alcohol consumption were retrospectively collected for three life periods: before the age of 18 years; between the age of 18 and 25 years; and between the age of 25 and 45 years. Frequency of binge drinking between 18 and 25 years was categorised as frequent if more than twice a month, occasional if once a month and never if no binge drinking.

Results

166 adults between 25 and 45 years were included: 83 were alcohol-dependent and 83 were non-alcohol-dependent. The mean age was 34.6 years (SD: 5.1). Frequent binge drinking between 18 and 25 years occurred in 75.9% of cases and 41.0% of controls (p<0.0001). After multivariate analysis, frequent binge drinking between 18 and 25 years was a risk factor for alcohol dependence between 25 and 45 years: adjusted OR=2.83, 95% CI 1.10 to 7.25.

Conclusions

Frequent binge drinking between 18 and 25 years appears to be a risk factor for alcohol dependence in adulthood. Prevention measures for binge drinking during preadulthood, especially frequent binge drinking, should be implemented to prevent acute consequences as injury and death and long-term consequences as alcohol dependence.

Trial registration number

NCT03204214; Results.

Keywords: epidemiology, mental health, substance misuse, public health

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study has high power due to the high number of cases clinically diagnosed by a specialised physician.

The effects of binge drinking were measured up to two decades after the initial period.

Analysis with the major confounding factors of alcohol dependence strengthens our result.

There is potential memory bias with regard to the reporting of binge drinking between 18 and 25 years.

Introduction

Daily alcohol consumption has decreased regularly in France since the 1990s, from 36% in men and 12% in women in 1992, to 15% and 5% in 2014, respectively. Conversely, alcohol consumption has increased in young people in France.1 Binge drinking (BD) or heavy episodic drinking is a common pattern of alcohol consumption among young people.2 It is characterised by the intake of a large amount of alcohol within a short period with the main purpose of getting drunk easily. It is typically defined by the consumption of five or more drinks for men or four or more drinks for women on a single occasion.3 This pattern peaks during late adolescence, generally in the early 20s, coinciding with university years.4 However, some individuals appear to maintain the BD pattern into adulthood.5 6

Notably, BD has become part of young adult culture in many Western countries, and its practice is now widespread among students in higher education.7 8 The prevalence of BD among university students and those aged 18–24 years old is approximately 30%–40%9–11 and 25%, respectively, and is especially high in France.12–14 BD in young people could be related to work stressors and a belief in the tension reduction properties of alcohol,15 16 but also to having fun, being happy, gaining confidence and being accepted by their peers.17 18 According to Oei and Morawska,19 the fact that young people may not fully understand the consequences of alcohol use and abuse may be linked to the acceptance of alcohol in Western culture and society.

The short-term effects associated with BD have been widely analysed. When consumed in large quantities on a single occasion, like a binge episode, alcohol can cause death directly by suppressing the brainstem nuclei that control vital reflexes; it can generate inflammation and transient damage to health.7 20 Moreover, alcohol consumption is directly related to coma episodes and other cognitive impairments, acute pancreatitis episodes, hypertension, increased risk of addiction, and suicide.7 21 22 Binge drinkers may perform actions that they will regret, experience memory blackout, have unplanned and unsafe sex, and drive after drinking.23 24 Evidence based on the long-term consequences of alcohol consumption in adolescence has not been as extensive nor as compelling as it could be as reported in a systematic review,25 although some studies have reported the impact of adolescent drinking on adult drinking disorders.26–28

The rates of alcohol dependence, linked to a loose control over its consumption, poor tolerance of side effects and withdrawal symptoms, vary from 1.5% in women to 7.8% in men.29 Well-known risk factors of alcohol dependence are mainly related to genetic factors,30 age at onset of alcohol,31 favourable parental attitudes towards alcohol use, parental drinking and poor parent–child relationship.32

Studies carried out in animal models have found an increased risk of alcohol dependence in adult rats exposed to heavy alcohol consumption in adolescence.33 Enhanced ethanol consumption has been associated with reduced aversive and rewarding properties of ethanol and with enduring neuroadaptations in the nucleus accumbens, which plays a significant role in addiction.34 The impact of BD behaviour during early adulthood on alcohol dependence later on has been poorly studied and only up to the age of 30 years.35–38 Authors have suggested that the prevalence of alcohol dependence may increase with the frequency of BD.28

Therefore the purpose of this study was to evaluate whether frequent BD, between the age of 18 and 25 years, was a risk factor for alcohol dependence in adults up to the age of 45 years.

Methods

Design

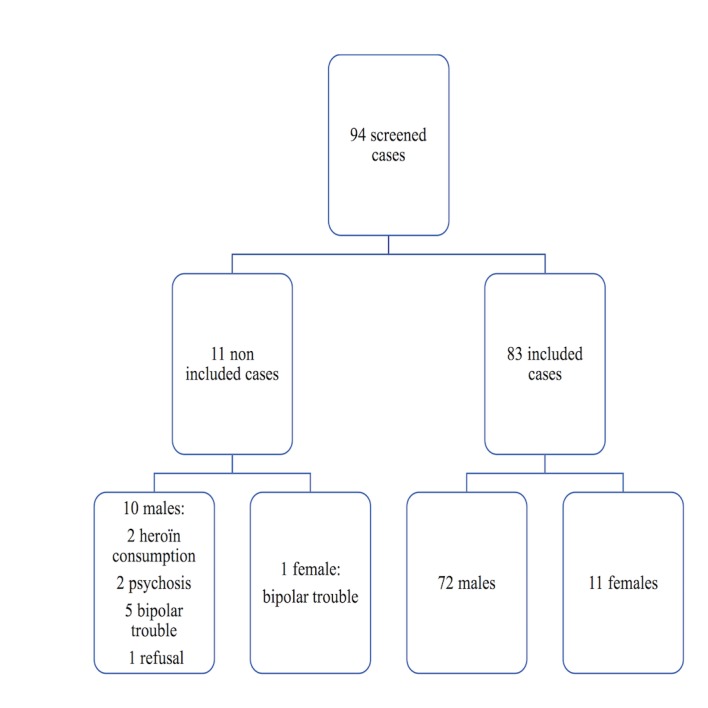

A retrospective, matched, case–control study was performed. Cases were alcohol-dependent (AD) according to the International Classification of Diseases-10 (WHO 1992). The criteria for alcohol dependence were behavioural, cognitive and physiological phenomena that develop after repeated alcohol use, and that typically include a strong desire to consume alcohol, difficulties in controlling its use, persisting in its use despite harmful consequences, a higher priority given to alcohol use than to other activities and obligations, increased tolerance, and sometimes a physiological state of withdrawal. Cases were aged 25–45 years old. Exclusion criteria were history or current heroin consumption, mood disorder (bipolar disorder) and psychosis (figure 1). Consecutive patients referred to the Department of Addictive Medicine of a university hospital between 1 January 2017 and 31 December 2017 for alcohol dependence were included in the study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of alcohol-dependent cases.

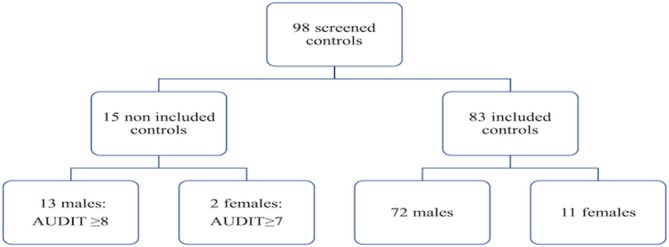

AD cases were compared with a matched group of non-AD controls (one case and one control). Matching was based on age and gender. Controls were randomly recruited from the volunteer registry of the Clinical Investigation Center of the same university hospital. Controls filled out an anonymous self-administered questionnaire. Alcohol abuse was assessed using the French version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) questionnaire designed to identify hazardous drinkers, harmful drinkers and those with risk of AD. A score below 8 for men or 7 for women indicates no problems with alcohol, a score between 8 and 12 for men or between 7 and 11 for women indicates hazardous drinking, and a score above 12 for men or 11 for women indicates risk of addiction. Cronbach’s α test was 0.83.39 Exclusion criteria were alcohol disorders evaluated by an AUDIT score of 8 or more for men and 7 or more for women (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Flow chart of non-alcohol-dependent controls. AUDIT, Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Patient and public involvement

No patients were involved in setting the research question or the outcome measures, nor were they involved in developing plans for the design or implementation of the study. Controls were healthy volunteers participating in medical research protocols and registered in the database of the Clinical Investigation Center with data on their gender, date of birth and contacts. The main results of the study will be displayed on the Clinical Investigation Center website.

Data collection

Data were collected using structured interview with one psychiatrist for the AD cases and using a self-reported online survey for the non-AD controls. Data were retrospectively collected for three life periods: period 1, before the age of 18 years; period 2, between the age of 18 and 25 years; and period 3, between the age of 25 and 45 years.

Period 1

Data collected were father’s and mother’s history of alcoholism, school year repeated, high school diplomas, age of first alcoholic drink and first episode of drunkenness.

Period 2

To enhance the accuracy of these retrospective data, two subperiods were defined: between 18 and 21 years and between 22 and 25 years.

Data collected were student status, living at parents’ home, relationship with parents, living in a couple, doing sport, smoking and cannabis use. A single variable was obtained from the data of the two subperiods: a ‘yes’ response for one or both subperiods was recorded as ‘yes’ for the entire period. For smoking, cannabis use and sport, the cumulated month of use for each subperiod was also collected and added to make the total cumulative month of use.

Data were collected on alcohol consumption during this period. BD, defined as consumption of five or more alcoholic drinks (four or more for female students),40 was categorised as frequent if more than twice a month, occasional if once a month or less and never if no BD8 (table 1). For logistic regression, the two categories, ‘never BD’ and ‘occasional BD’, are presented as a single category.

Table 1.

Classification of binge drinking (BD) during the period 18–25 years according to frequency during the periods 18–21 years and 22–25 years (n=166)

| 22–25 years | |||

| 18–21 years | Never | Occasional | Frequent |

| Never | Never (19) | Occasional (6) | Frequent (0) |

| Occasional | Occasional (0) | Occasional (43) | Frequent (6) |

| Frequent | Frequent (1) | Frequent (16) | Frequent (75) |

For example, six participants who had occasional BD during the period 18–21 years and frequent BD during the period 22–25 years were categorised as frequent BD during the period 18–25 years.

Data were collected on the pattern of BD and alcohol consumption (during meals or not) and frequency in the company of friends, family or alone (frequent, occasional and never).

Period 3

Data were collected on employment status: university student, blue-collar worker, employee, mid-level activity, managers/intellectual profession and no professional activity, current smoking status, and BD.

Statistical analysis

Univariate analysis

Qualitative variables were described as percentages and compared using Fisher’s exact test. Continuous variables were described by their mean and SD and were compared using Student’s test.

Multivariate analysis

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to investigate the associations between frequent BD between the age of 18 and 25 years and AD between the age of 25 and 45 years. Two models of logistic regression were performed with AD as a dependent variable: model 1 with period 1 confounders and BD between the age of 18 and 25 years as independent variables; model 2 with period 2 confounders and BD between the age of 18 and 25 years as independent variables. All possible confounders of period 1 and period 2 with a p value below 0.20 in univariate analysis were included in model 1 and in model 2, respectively. Adjusted ORs (AORs) and their 95% CIs were calculated. Associations were considered statistically significant when p<0.05. The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was performed for the logistic regression models. The analysis was conducted using XLSTAT-Biomed V.19.5 (2017).

Results

Characteristics of AD cases and non-AD controls

A total of 166 adults between the age of 25 and 45 years were included, comprising 83 AD cases, 72 men and 11 women, and 83 non-AD controls, 72 men and 11 women. The mean age was 34.6 years (SD: 5.1). The characteristics of cases and controls during the three periods (before 18 years, 18–25 years and 25–45 years) are presented in table 2. AD cases had significantly more family history of (father and mother) alcoholism than non-AD controls. There was no difference between cases and controls with regard to the age of first alcoholic drink (p=0.76) or episode of drunkenness (p=0.23). For the period 18–25 years, AD cases had a bad relationship with parents (27.7%) more frequently than non-AD controls (8.4%), did less sport, and were more frequent smokers and cannabis users than non-AD controls. For the period 25–45 years, AD cases were more often smokers (91.6% vs 31.3%; p<0.0001) and without professional activity than non-AD controls (25.3% vs 3.6%; p<0.0001).

Table 2.

Characteristics of AD cases and non-AD controls in the three periods: before 18 years, 18–25 years and 25–45 years (n=166)

| Non-AD controls (n=83) | AD cases (n=83) | P value | |

| Period 1: before 18 years | |||

| Father’s history of alcoholism (%) | 18.9 | 42.2 | <0.001 |

| Mother’s history of alcoholism (%) | 2.9 | 25.4 | 0.005 |

| Repeating a school year (%) | 45.8 | 72.3 | 0.001 |

| High school diploma (%) | 91.6 | 45.8 | <0.0001 |

| Age of first alcoholic drink, mean (SD) | 15.1 (1.8) | 15.0 (3.9) | 0.76 |

| Age of first episode of drunkenness, mean (SD) | 17.3 (3.1) | 16.6 (3.7) | 0.23 |

| Period 2: 18–25 years | |||

| University students (%) | 85.4 | 37.4 | <0.0001 |

| Living in parents’ home (%) | 71.1 | 53.0 | 0.01 |

| Relationship with parents (%) | 0.005 | ||

| Good | 49.4 | 38.6 | |

| Medium | 42.2 | 33.7 | |

| Bad | 8.4 | 27.7 | |

| Living in a couple (%) | 60.2 | 62.6 | 0.75 |

| Doing sport (%) | 71.1 | 57.8 | 0.007 |

| Cumulated month of sport, mean (SD) | 38.3 (35.6) | 50.6 (46.6) | 0.06 |

| Smoking (%) | 48.2 | 97.6 | <0.0001 |

| Cumulated month of smoking, mean (SD) | 27.9 (36.1) | 91.9 (18.0) | <0.0001 |

| Cannabis use (%) | 26.5 | 65.0 | <0.0001 |

| Cumulated month of cannabis use, mean (SD) | 1.6 (5.5) | 15.7 (14.8) | <0.0001 |

| Frequency of alcohol consumption (except BD) (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Never | 13.3 | 27.7 | |

| Occasional | 81.9 | 35.0 | |

| Frequent | 4.8 | 37.3 | |

| Period 3: 25–45 years | |||

| Current professional status (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Without professional activity | 3.6 | 25.3 | |

| University student | 4.8 | 0.0 | |

| Blue-collar worker | 1.2 | 25.3 | |

| Employee | 27.7 | 16.9 | |

| Mid-level activity | 18.1 | 19.2 | |

| Manager/Intellectual profession | 44.6 | 13.3 | |

| Current smoking status (%) | <0.0001 | ||

| Never smoker | 45.8 | 0.0 | |

| Former smoker | 22.9 | 8.4 | |

| Current smoker | 31.3 | 91.6 |

AD, alcohol-dependent; SD, Standard Deviation; BD, binge drinking.

BD between the age of 18 and 25 years and alcohol dependence between the age of 25 and 45 years

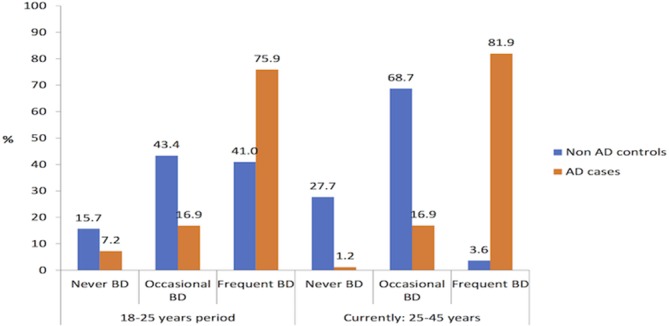

Figure 3 shows the prevalence of BD between the age of 18 and 25 years and between the age of 25 and 45 years. Frequent BD between the age of 18 and 25 years occurred in 75.9% of AD cases and 41.0% of non-AD controls (p<0.0001). A decrease was observed in the prevalence of frequent BD among non-AD controls, from 41.0.1% between the age of 18 and 25 years to 3.6% between the age of 25 and 45 years (p=0.006), but not for AD cases, from 75.9% to 81.9% (p=0.20). In univariate analysis, frequent BD between the age of 18 and 25 years was associated with AD between 25 and 45 years: crude OR=4.32, 95% CI 2.22 to 8.40 (p<0.0001).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of BD between the age of 18 and 25 years and 25 and 45 years among AD cases and non-AD controls (n=166). AD, alcohol-dependent; BD, binge drinking.

After multivariate analysis, frequent BD between the age of 18 and 25 years was a risk factor for AD between 25 and 45 years: AOR=2.83, 95% CI 1.10 to 7.25 with model 1, and AOR=2.93, 95% CI 1.33 to 6.35 with model 2 (table 3). The Hosmer-Lemeshow goodness-of-fit tests were, respectively, 0.61 and 0.69. Other factor positively significantly associated with AD was a father with history of alcoholism, and factors negatively associated were being a university student and living with parents between the age of 18 and 25 years.

Table 3.

Factors associated with alcohol dependence according to factors before the age of 18 years (model 1) and between the age of 18 and 25 years (model 2), multivariate analysis (n=166)

| AOR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Model 1 | ||

| Binge drinking (18–25 years) | ||

| Never or occasional | Ref | 0.03 |

| Frequent | 2.83 (1.10 to 7.25) | |

| Characteristics of period 1 | ||

| Father’s history of alcoholism | 2.93 (1.21 to 7.11) | 0.02 |

| Mother’s history of alcoholism | 1.99 (0.47 to 8.45) | 0.34 |

| Repeating a school year | 1.76 (0.77 to 4.00) | 0.17 |

| High school diploma | 0.14 (0.05 to 0.38) | <0.0001 |

| Model 2 | ||

| Binge drinking (18–25 years) | ||

| Never or occasional | Ref | 0.007 |

| Frequent | 2.93 (1.33 to 6.35) | |

| Characteristics of period 2 | ||

| University student | 0.09 (0.04 to 0.24) | <0.0001 |

| Living in parents’ home | 0.35 (0.14 to 0.88) | 0.03 |

| Relationship with parents | ||

| Good | Ref | |

| Medium | 0.65 (0.25 to 1.69) | 0.38 |

| Bad | 3.04 (0.78 to 11.77) | 0.11 |

| Frequency of alcohol consumption (except binge drinking) | ||

| Never | Ref | |

| Occasional | 0.15 (0.05 to 0.46) | 0.001 |

| Frequent | 1.10 (0.21 to 5.70) | 0.91 |

Period 1: before 18 years.

Period 2: between 18 and 25 years.

Frequent alcohol consumption between the age of 18 and 25 years (except BD) occurred in 37.3% of AD cases and in 4.3% of non-AD controls (p<0.0001). Table 4 shows the pattern of alcohol consumption and of BD between the age of 18 and 25 years. BD alone and with friends was more frequently observed among AD cases than among non-AD controls: 12.0% vs 1.6% (p=0.01) and 83.1% vs 33.7% (p<0.0001), respectively.

Table 4.

Pattern of binge drinking and alcohol consumption between the age of 18 and 25 years among AD cases and non-AD controls (n=166)

| Non-AD controls (n=83) | AD cases (n=83) | P value | |

| Occasions of binge drinking (%) | |||

| Often with friends | 33.7 | 83.1 | <0.0001 |

| Often with family | 2.4 | 9.6 | 0.10 |

| Often alone | 1.2 | 12.0 | 0.01 |

| Occasions of alcohol consumption during meals (%) | |||

| Often with friends | 27.7 | 68.7 | <0.0001 |

| Often with family | 15.6 | 25.3 | 0.17 |

| Often alone | 1.2 | 8.4 | 0.07 |

| Occasions of alcohol consumption not during meals (%) | |||

| Often with friends | 18.1 | 75.9 | <0.0001 |

| Often with family | 2.5 | 18.1 | 0.02 |

| Often alone | 0.0 | 12.0 | 0.03 |

AD, alcohol-dependent.

Discussion

In this study, frequent BD between the age of 18 and 25 years was found a potential predictive factor for alcohol dependence between the age of 25 and 45 years with a threefold increased risk regardless of the risk factors of alcoholism. The two models with the risk factors before 18 years or during the period 18–25 years found the same risk of alcohol dependence with frequent BD, respectively (AOR=2.83 and AOR=2.93), which strengthens our results. Our findings confirm previous results found in animal studies and in young adult populations.34 36 37

In our study, three-quarters of future AD adults had been frequent binge drinkers between the age of 18 and 25 years, mainly in the company of friends. Mattick et al 41 reported that drinking alone and with the family occurred more often among future AD adults. We observed a decrease in the prevalence of frequent BD between the ages of 18–25 years and 25–45 years among non-AD adults. This could be to comply with the expectations and obligations of adult social roles such as marriage, childbearing and employment.42 Among AD adults frequent BD increased between the ages of 18–25 years and 25–45 years. This increase could be explained by an imbalance between poor cognitive control and greater alcohol bias, which may contribute to the persistence of BD into adulthood.36

Adolescence and young adulthood are specific periods during development when both genetic-driven and environmental processes interact to establish functional characteristics, as selective attention, working memory or problem solving.43 Indeed, synaptic pruning, myelination and grey matter changes are very effective over the first three decades of life, involving improved function, suggesting implications for the entire adult stage of life. Among environmental experiences contributing to structural changes in the brain during this critical period of cortical development, alcohol consumption, especially BD, is known to disrupt cortical development.44

Although previous studies showed that BD seems to be more common among university students than non-students,4 45 we found that being a university student between the age of 18 and 25 years was negatively associated with AD in adulthood, representing a protective factor. Wellman et al 46 reported that continuing BD was more likely associated with no university education. Continued parental involvement and communication may serve to protect against high-risk drinking and prevent harm even at this stage of emerging adulthood.5 47 In our study, the age of the first alcoholic drink or episode of drunkenness was not found as a predictive factor of AD contrary to previous reports.48 49 However, these studies did not consider BD as a confounding factor: indeed, consumption of alcohol during adolescence is correlated with frequent BD. As expected we found history of family alcoholism as a significant risk factor of alcoholism.35 37

Our results showed that smoking and cannabis use between the age of 18 and 25 years were prevalent among the population of future AD adults as previously reported,14 and current AD adults were also smokers.34 Unemployment has already been reported to be more prevalent among AD adults than in the general population (8.9%),50 and AD adults are more often less qualified.12

Strengths and limitations

The main strength of our study is the high number of cases clinically diagnosed by a physician specialised in addictive medicine, leading to significant results. The effects of BD were measured up to two decades after the initial BD period, representing potential confounding factors of both alcohol dependence and BD. However, our study provides information for individuals who were young adults in the 1990s and 2000s, not for the young adults of today. There may have been a selection bias for the control population, but this was likely minimised by the 96% sensitivity of the AUDIT test.51 In addition, our findings on the prevalence of BD, age of first drink and first episode of drunkenness between the age of 18 and 25 years in controls are similar to those reported in the literature.52 There may have been a memory bias with regard to the reporting of BD frequency between the age of 18 and 25 years; however, this period was divided into two subperiods for data collection allowing greater accuracy. BD has been related to memory loss, representing a higher risk of memory bias for AD, and the OR could be underestimated. The external environment could change over that time, however could equally affect the cases and the controls. Our definition of BD is standardised that our results could be transferable to the current context. The fact that the self-questionnaire was anonymous likely limited any under-reporting of alcohol consumption of the non-AD controls. If, during the medical consultation with the psychiatrist, the AD cases had under-reported their BD between the age of 18 and 25 years, the AOR found would have been higher.

Conclusions and future implications

Our study highlights the extreme importance of addressing the public health issue of BD in young adults and alcohol dependence in adulthood. Prevention measures for BD during preadulthood, especially frequent BD, should be implemented to prevent acute consequences as injury and death, and also long-term consequences as alcohol dependence. Reducing BD among adults remains a major health concern in healthy people.53 Psychosocial rather than pharmacological interventions could be recommended as first-line treatment for BD, while pharmacological treatments should be preferred for alcohol dependence.54

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Nikki Sabourin-Gibbs, Rouen University Hospital, for her help in editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: Designed the research (project conception, development of overall research plan and study oversight): M-PT, AB, JL, PD. Conducted the research (hands-on conduct of the experiments and data collection): M-PT, AB, DC, QB. Analysed the data or performed statistical analysis: M-PT. Wrote the paper (only authors who made a major contribution): M-PT, AB. Had primary responsibility for final content: M-PT.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study design has been approved by the ’Commission Nationale de l’Informatique et des Libertes' (the French Electronic Data Protection Authority) (declaration number 1945778) and Rouen University Hospital’s Institutional Review Board without mandatory informed consent.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: All available data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. L’état de santé de la population en France 2017. Santé publique France. http://drees.social-sante.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/esp2017.pdf (avaiable 15 May 2018).

- 2. Kuntsche E, Kuntsche S, Thrul J, et al. Binge drinking: Health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol Health 2017;32:976–1017. 10.1080/08870446.2017.1325889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Mokdad A, et al. Binge drinking among US adults. JAMA 2003;289:70–5. 10.1001/jama.289.1.70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Merrill JE, Carey KB. Drinking over the lifespan: Focus on college ages. Alcohol Res 2016;38:103–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Moure-Rodríguez L, Piñeiro M, Corral Varela M, et al. Identifying predictors and prevalence of alcohol consumption among university students: Nine years of follow-up. PLoS One 2016;11:e0165514–5. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jefferis BJ, Power C, Manor O. Adolescent drinking level and adult binge drinking in a national birth cohort. Addiction 2005;100:543–9. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01034.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl 2009:12–20. 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tavolacci MP, Boerg E, Richard L, et al. Prevalence of binge drinking and associated behaviours among 3286 college students in France. BMC Public Health 2016;16:178 10.1186/s12889-016-2863-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, et al. Trends in college binge drinking during a period of increased prevention efforts. Findings from 4 Harvard School of Public Health College Alcohol Study surveys: 1993-2001. J Am Coll Health 2002;50:203–17. 10.1080/07448480209595713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. D’Alessio M, Baiocco R, Laghi F. The problem of binge drinking among Italian university students: a preliminary investigation. Addict Behav 2006;31:2328–33. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kwan MY, Faulkner GE, Arbour-Nicitopoulos KP, et al. Prevalence of health-risk behaviours among Canadian post-secondary students: descriptive results from the national college health assessment. BMC Public Health 2013;13:548 10.1186/1471-2458-13-548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kanny D, Naimi TD, Liu Y, et al. Annual total binge drinks consumed by U.S. adults. Am J Prev Med 2018;4:486–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health—2014. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 2014. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112736/1/9789240692763_eng.pdf (Accessed 18 Aug 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 14. Peacock A, Leung J, Larney S, et al. Global statistics on alcohol, tobacco and illicit drug use: 2017 status report. Addiction 2018;113:1905–26. 10.1111/add.14234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gilles DM, Turk CL, Fresco DM. Social anxiety, alcohol expectancies, and self-efficacy as predictors of heavy drinking in college students. Addict Behav 2006;31:388–98. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.05.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Butler AB, Dodge KD, Faurote EJ. College student employment and drinking: a daily study of work stressors, alcohol expectancies, and alcohol consumption. J Occup Health Psychol 2010;15:291–303. 10.1037/a0019822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ridout B, Campbell A, Ellis L. ‘Off your Face(book)’: alcohol in online social identity construction and its relation to problem drinking in university students. Drug Alcohol Rev 2012;31:20–6. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00277.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dolcini MM. A new window into adolescents' worlds: the impact of online social interaction on risk behavior. J Adolesc Health 2014;54:497–8. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.02.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Oei TP, Morawska A. A cognitive model of binge drinking: the influence of alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy. Addict Behav 2004;29:159–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zagrosek A, Messroghli D, Schulz O, et al. Effect of binge drinking on the heart as assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. JAMA 2010;304:1328–30. 10.1001/jama.2010.1343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Guérin S, Laplanche A, Dunant A, et al. Alcohol-attributable mortality in France. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:588–93. 10.1093/eurpub/ckt015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Bartoli F, Carretta D, Crocamo C, et al. Prevalence and correlates of binge drinking among young adults using alcohol: a cross-sectional survey. Biomed Res Int 2014;2014:1–7. 10.1155/2014/930795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wechsler H, Lee JE, Kuo M, et al. College binge drinking in the 1990s: a continuing problem. Results of the Harvard School of Public Health 1999 College Alcohol Study. J Am Coll Health 2000;48:199–210. 10.1080/07448480009599305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. White A, Hingson R. The burden of alcohol use: excessive alcohol consumption and related consequences among college students. Alcohol Res 2013;35:201–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCambridge J, McAlaney J, Rowe R. Adult consequences of late adolescent alcohol consumption: a systematic review of cohort studies. PLoS Med 2011;8:e1000413 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Englund MM, Egeland B, Oliva EM, et al. Childhood and adolescent predictors of heavy drinking and alcohol use disorders in early adulthood: a longitudinal developmental analysis. Addiction 2008;103 Suppl 1:23–35. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02174.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Merline A, Jager J, Schulenberg JE. Adolescent risk factors for adult alcohol use and abuse: stability and change of predictive value across early and middle adulthood. Addiction 2008;103 Suppl 1:84–99. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02178.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Degenhardt L, O’Loughlin C, Swift W, et al. The persistence of adolescent binge drinking into adulthood: findings from a 15-year prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2013;3:e003015 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-003015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gowing LR, Ali RL, Allsop S, et al. Global statistics on addictive behaviours: 2014 status report. Addiction 2015;110:904–19. 10.1111/add.12899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Prom-Wormley EC, Ebejer J, Dick DM, et al. The genetic epidemiology of substance use disorder: A review. Drug Alcohol Depend 2017;180:241–59. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.06.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abuse 1997;9:103–10. 10.1016/S0899-3289(97)90009-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yap MBH, Cheong TWK, Zaravinos-Tsakos F, et al. Modifiable parenting factors associated with adolescent alcohol misuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Addiction 2017;112:1142–62. 10.1111/add.13785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vargas WM, Bengston L, Gilpin NW, et al. Alcohol binge drinking during adolescence or dependence during adulthood reduces prefrontal myelin in male rats. J Neurosci 2014;34:14777–82. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3189-13.2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Alaux-Cantin S, Warnault V, Legastelois R, et al. Alcohol intoxications during adolescence increase motivation for alcohol in adult rats and induce neuroadaptations in the nucleus accumbens. Neuropharmacology 2013;67:521–31. 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2012.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bingham CR, Shope JT, Tang X. Drinking behavior from high school to young adulthood: differences by college education. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29:2170–80. 10.1097/01.alc.0000191763.56873.c4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Carbia C, Corral M, Doallo S, et al. The dual-process model in young adults with a consistent binge drinking trajectory into adulthood. Drug Alcohol Depend 2018;186:113–9. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.01.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Olsson CA, Romaniuk H, Salinger J. Drinking patterns of adolescents who develop alcohol use disorders: results from the Victorian Adolescent Health Cohort Study. BMJ Open 2015. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Viner RM, Taylor B. Adult outcomes of binge drinking in adolescence: findings from a UK national birth cohort. J Epidemiol Community Health 2007;61:902–7. 10.1136/jech.2005.038117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Gache P, Michaud P, Landry U, et al. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) as a screening tool for excessive drinking in primary care: reliability and validity of a French version. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2005;29:2001–7. 10.1097/01.alc.0000187034.58955.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheng H, Furnham A. Correlates of adult binge drinking: evidence from a British cohort. PLoS One 2013;8:e78838 10.1371/journal.pone.0078838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mattick RP, Clare PJ, Aiken A, et al. McBride N7, Kypri K, Vogl L, Degenhardt L. Association of parental supply of alcohol with adolescent drinking, alcohol-related harms, and alcohol use disorder symptoms: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2018;2:e64–e71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Winograd RP, Littlefield AK, Sher KJ. Do people who "mature out" of drinking see themselves as more mature? Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2012;36:1212–8. 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01724.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dawson G, Ashman SB, Carver LJ. The role of early experience in shaping behavioral and brain development and its implications for social policy. Dev Psychopathol 2000;12:695–712. 10.1017/S0954579400004089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Blakemore SJ, Choudhury S. Development of the adolescent brain: implications for executive function and social cognition. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2006;47:296–312. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01611.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kypri K, Cronin M, Wright CS. Do university students drink more hazardously than their non-student peers? Addiction 2005;100:713–4. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01116.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wellman RJ, Contreras GA, Dugas EN, et al. Determinants of sustained binge drinking in young adults. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2014;38:1409–15. 10.1111/acer.12365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Turrisi R, Ray AE. Sustained parenting and college drinking in first-year students. Dev Psychobiol 2010;52:n/a–294. 10.1002/dev.20434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, et al. Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2000;157:745–50. 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.5.745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Silins E, Horwood LJ, Najman JM, et al. Adverse adult consequences of different alcohol use patterns in adolescence: an integrative analysis of data to age 30 years from four Australasian cohorts. Addiction 2018;113 10.1111/add.14263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Institut National de la Statistique et des études économiques. https://www.insee.fr/fr/statistiques/3326105 (Accessed 16 May 2018).

- 51. Isaacson JH, Butler R, Zacharek M, et al. Screening with the alcohol use disorders identification Test (AUDIT) in an inner-city population. J Gen Intern Med 1994;9:550–3. 10.1007/BF02599279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kraus L, Hakan L, Vicente J, et al. Results from the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs. Luxembourg: EMCDDA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 53. SA–14.3 Reduce the proportion of persons engaging in binge drinking during the past 30 days—adults aged 18 years and older. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Substance abuse. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/substance-abuse/objectives#5205 (Accessed 30 Apr 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 54. Rolland B, Naassila M. Binge drinking: current diagnostic and therapeutic issues. CNS Drugs 2017;31:181–6. 10.1007/s40263-017-0413-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.