Abstract

Objectives

Government spending on social care in England reduced substantially in real terms following the economic crisis in 2008, meanwhile emergency admissions to hospitals have increased. We aimed to assess the extent to which reductions in social care spend on older people have led to increases in emergency hospital admissions.

Design

We used negative binomial regression for panel data to assess the relationship between emergency hospital admissions and government spend on social care for older people. We adjusted for population size and for levels of deprivation and health.

Setting

Hospitals and adult social care services in England between April 2005 and March 2016.

Participants

People aged 65 years and over resident in 132 local councils.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome variable—emergency hospital admissions of adults aged 65 years and over. Secondary outcome measure—emergency hospital admissions for ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) of adults aged 65 years and over.

Results

We found no significant relationship between the changes in the rate of government spend (£’000 s) on social care for older people within councils and our primary outcome variable, emergency hospital admissions (Incidence rate ratio (IRR) 1.009, 95% CI 0.965 to 1.056) or our secondary outcome measure, admissions for ACSCs (IRR 0.975, 95% CI 0.917 to 1.038).

Conclusions

We found no evidence to support the view that reductions in government spend on social care since 2008 have led to increases in emergency hospital admissions in older people. Policy makers may wish to review schemes, such as the Better Care Fund, which are predicated on a relationship between social care provision and emergency hospital admissions of older people.

Keywords: social care, emergency hospital admissions, older people, government spending

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study explores the relationship between government spending on social care and emergency hospital admissions across a large area (132 councils) and a long period (10 years).

The study includes a period of time when reductions in government spending on social care were large on average and variable between councils, increasing the opportunity to detect an impact on emergency hospital admissions.

The study used panel data methods which help reduce the risk of omitted variable bias.

Changes in the way councils record expenditure may have obscured the relationship with emergency hospital admissions.

Sensitivity analysis was used to explore the possibility that the results are a function of the influential outliers or the choice of analytical method.

Introduction

The economic crisis beginning in 2008 caused many countries to cut public sector expenditure on healthcare. Successive governments in England have sought to maintain health spending by imposing a ‘ring fence’. However, central government grants to local councils, who are responsible for funding social care have been reduced.1 The term ‘social care’ is used to describe a range of support services which help people carry out daily living tasks and therefore live independently. This can include help with washing, dressing, cooking, cleaning, getting in and out of bed as well as fitting adaptations such as stairlifts, handrails and bath seats. Social care can be delivered within an individual’s private residence or as part of a placement in a care home or supported living scheme. Unlike healthcare, which is largely provided free at the point of use, social care for older people in England is means-tested and the majority of recipients will be expected to contribute towards the cost of their care. The numbers of older people receiving government-funded social care fell by 40% between March 2008 and March 2014 while the population aged 65+ years increased by 15%.2 3 While some people who are no longer supported by the state might choose to pay for care privately or to rely on informal care, others may have to just make do with less social care support.

Meanwhile, demand for urgent and emergency care is rising. The number of people aged 65+ years attending accident and emergency departments in England rose by 64% between 2008 and 2015.4 Looking forward, the number of people aged 65+ years is excepted to grow from 9.9 million in 2016 to over 12 million by 2028.5 There is growing concern that undersupply of social care is increasing pressures on urgent and emergency care by leaving older people at greater risk of hospital admission and delaying their discharge from hospital. Nearly 9 out of 10 National Health Service (NHS) hospital finance directors believe that funding pressures on councils have had a negative impact on the performance of health services in their local area.6

Much of the evidence supporting this claim, however, is anecdotal. The effect of reductions in social care on the health and well-being of older people, and in particular their use of emergency healthcare services has not been quantified.7 A small number of studies in European countries have found evidence of a trade-off between the number of hospital beds and the level of social care provision.8–10 The reported effect, however, was relatively small; and the research mostly focused on long-term residential care and/or hospital length of stay, and predates the most significant reductions in social care expenditure.

Many health systems are exploring the benefits of greater integration between health and care services.11 In England, the current government’s policy is predicated on the view that closer working between health and social care will ease pressure on emergency services. For example, the Better Care Fund, worth a minimum of £3.9 billion in 2016–2017, is for joint projects between local government and the NHS.12 The broad intention is to shift resources from the NHS into social care and community services by keeping patients out of hospitals, but much of the required investment will only become available if savings can be made from avoiding unplanned admissions to hospital or reducing length of stay.

The aim of this study is to determine the extent to which reductions in government spending on social care for older adults, following the economic crisis, have led to increases in emergency admissions to hospitals.

Methods

Setting and study population

Our analysis focused on local government councils with responsibility for providing adult social care services in England between 2005–2006 and 2015–2016. In 2015–2016, there were 152 English councils with responsibility for providing adult social care services. Nine of these councils were only established following structural changes to local government in April 2009. These areas were excluded from all analyses. A further three councils were missing spend data for at least 1 year, these areas were also excluded. The City of London, the Isles of Scilly and Rutland were excluded because we expected their small populations would cause instability. We excluded a further five councils that reported a year-on-year change in emergency hospital admissions for older people of >50% in one or more years between 2005/2006 and 2015/2016 on the basis that these jumps are implausible and are more likely to represent data errors. This left a balanced panel dataset of 1452 observations (n=132, T=11). The list of the councils excluded from the analysis is provided in online supplementary file 1.

bmjopen-2018-024577supp001.pdf (55.4KB, pdf)

Data sources

The data used in this study were collected from a number of national information systems. The main outcome variable in our analysis is counts of emergency admissions to hospitals (admissions that happen at short notice because of perceived clinical need) by people aged 65 years and over in each council area. We obtained this information from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) dataset. HES contains records of all admissions for patients admitted to NHS hospitals, and includes information on method of admission (eg, emergency), diagnosis codes recording the primary reason the patient is being treated and any secondary diagnoses relevant to their care.13 We hypothesised that some types of admission are more likely to be avoidable by timely access to social care. Ambulatory care sensitive conditions (ACSCs) are a well-defined set of conditions where effective community care and case management can help prevent the need for hospital admission.14 Counts of emergency hospital admissions of people aged 65 years and over for ACSC conditions were derived from HES and used as a secondary outcome measure.

Our main exposure variable was government spending on social care. We obtained financial data relating to publicly funded social care for older people (those aged 65+ years) from administrative returns provided to central government by the social services departments of councils providing adult social care services in England. Publicly funded social care in England is targeted at those with the highest needs and lowest incomes. Older people who meet needs-based eligibility criteria but whose income and assets are above a set amount are required to contribute a proportion of the cost themselves, and some with needs receive no financial support. We calculated a series for councils’ net expenditure by subtracting contributions paid by service users for their care from councils’ gross total expenditure on services for older people. These expenditure levels include income from the NHS through schemes such as the Better Care Fund.

In 2014–2015, there were changes to the financial reporting framework used by councils to collect these data that meant we needed to ‘map’ categories of council income across the two frameworks to obtain a consistent series on councils’ income from client contributions. Bridging files were published by NHS Digital to facilitate mapping exercises of this type.15

We adjusted net total expenditure, by each council in each year, to 2015–2016 prices using the Gross Domestic Product Price Deflator.16 To account for differences in population size, we used population estimates from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to calculate a rate of expenditure per head of population aged 65 years or over per year for each council area.17

In the UK and other countries, admission rates are significantly correlated with measures of social deprivation.18 To control for socioeconomic deprivation, we used data from the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2015, the official area-based measure of relative deprivation in England. We used the Income Deprivation Affecting Older People Index (IDAOPI), a supplementary index to the overall income domain that measures the proportion of adults aged 60 years or over living in income deprived households in each council area.19 We grouped council-level IDAOPI scores into fifths, with the first quintile group representing the least deprived.

Counts of deaths by age group, gender and local authority were supplied by the ONS. Mortality rates for people aged 65 years and over were calculated by dividing the number of deaths by the population for each council and year.

Statistical analyses

We initially investigated the unadjusted trends in the rates of emergency hospital admissions and government social care spend, in total and by council.

We used multivariable regression analysis for panel data to assess the relation between emergency hospital admissions (response variable), and net spend on government-funded social care for older people (predictor variable). We used negative binomial regression models as these are appropriate when the outcome is a count variable.20 To adjust for differences in population sizes of older people, we included the size of the population aged 65 years and over as an exposure variable. Panel data models were used to help reduce the risk of omitted variable bias. Given that we were interested in the population-averaged effect, we used general estimating equations to estimate the model coefficients. Decisions relating to selecting variables and the model correlation structure were made using the quasi-likelihood under the independence model criterion (QIC).21

For each council, we decomposed the variable representing government spending on social care into two new variables: a time-invariant average spend and a time-varying difference from average spend. This allowed us to assess the influence on our outcome of variation in social care spend ‘within’ councils (eg, over time) and ‘between’ councils.

Mortality rates among people aged 65 years and over and deprivation levels (IDAOPI quintiles) were used to control for differences in levels of population need.

To adjust for the long-term trend in emergency hospital admissions and to control for unobserved in-year effects, we included dummy variables for each year. We used robust SEs to reflect the fact that populations were not sampled independently and to ensure that SEs were robust to serial correlation in the data.

Models were prepared for two outcome variables: all emergency admissions for people aged 65 years and over (our primary outcome variable) and the subset of these which were for ACSCs.

Regression analyses were performed with Stata IC V.15.1. Data preparation was done using R Statistical Software V.3.3.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Sensitivity analyses

We performed several analyses to test the sensitivity of model results to outlier values and to elements of the model specification. To test the effect of outliers on the model coefficients, we calculated dfbeta values for each council for the variable representing government spend on social care and reran the model removing those councils with the highest dfbeta values. To test the sensitivity of the results on the choice of a population-averaged modelling approach, we recreated the model using a random-effects approach. To test the sensitivity of the results to lagged or leading effects of the time-varying independent variables, we reran the model lagging by 1 year the government spend on social care (on the basis that the impact of a change in social care spend may have a delayed impact on emergency admissions), and leading by 1 year the mortality rate variable (given that emergency admissions are known to rise exponentially for several years prior to death).22 Based on QIC values, our model incorporates year as a series of 10 (T-1) dummy variables, rather than as a single linear covariate. However, to assess whether the treatment of time in our model influenced the relationship between our outcome variable and our variable of interest, we produced a version of the model which incorporated time as a linear covariate. Finally, we tested the sensitivity of the model results to the specification of an independent within-group correlation structure.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and member of the public were not involved in the design of this study.

Results

Descriptive analysis

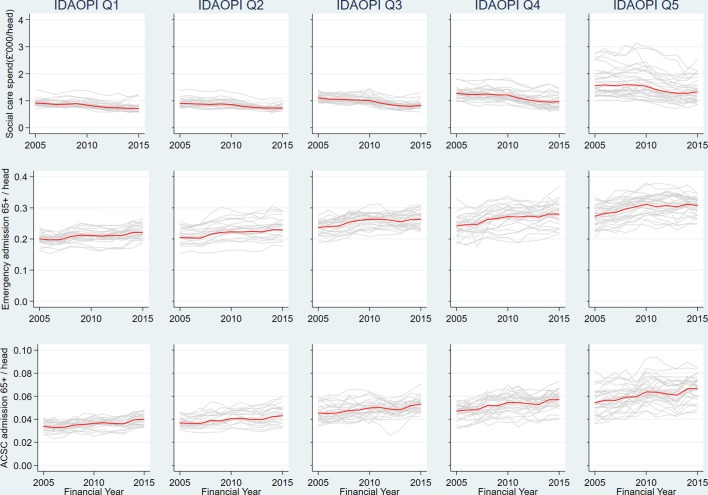

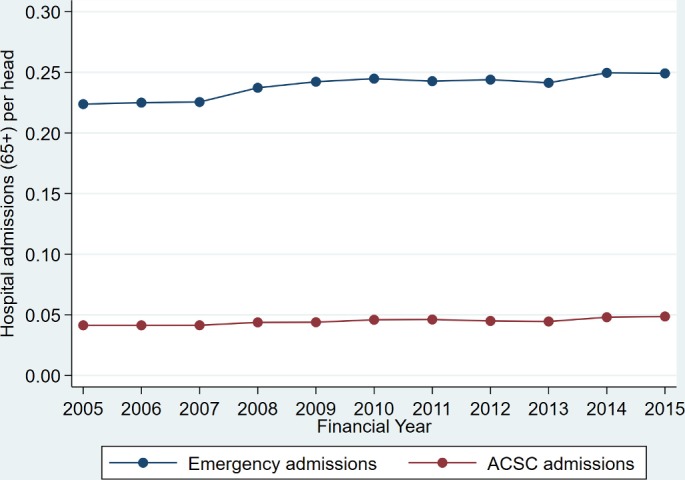

Between 2005/2006 and 2015/2016, the population aged 65 years and over grew on average by 1.9% per annum from 7.0 million to 8.4 million (see table 1). Over the same period, emergency hospital admissions of patients aged 65 years and over rose by 3.0% per annum (see figure 1). Government spend on social care for this age group reduced by 0.6% per annum after adjusting for inflation (see figure 2).

Table 1.

Trends in admissions, spend and population 2005/2006 to 2015/2016

| Financial year | Emergency admissions 65+ years | Emergency ACSC admissions 65+ years | Nominal government net spend on social care 65+ years £’000 s |

Real government net spend on social care 65+ years £’000 s |

Population 65+ years |

| 2005/2006 | 1 567 224 | 289 869 | 6 343 870 | 7 614 136 | 7 003 820 |

| 2006/2007 | 1 582 563 | 290 864 | 6 431 484 | 7 492 147 | 7 033 496 |

| 2007/2008 | 1 601 874 | 294 160 | 6 532 431 | 7 429 803 | 7 102 647 |

| 2008/2009 | 1 711 155 | 315 962 | 6 822 653 | 7 554 620 | 7 212 610 |

| 2009/2010 | 1 778 569 | 322 447 | 7 037 350 | 7 686 557 | 7 341 814 |

| 2010/2011 | 1 830 922 | 343 736 | 7 088 728 | 7 603 647 | 7 480 386 |

| 2011/2012 | 1 858 048 | 353 325 | 6 780 726 | 7 173 625 | 7 655 402 |

| 2012/2013 | 1 931 868 | 356 201 | 6 745 162 | 6 989 226 | 7 918 734 |

| 2013/2014 | 1 961 560 | 361 803 | 6 772 647 | 6 903 890 | 8 127 137 |

| 2014/2015 | 2 074 679 | 399 288 | 6 914 530 | 6 945 018 | 8 312 128 |

| 2015/2016 | 2 098 280 | 409 775 | 7 142 173 | 7 142 173 | 8 422 502 |

| Compound annual growth rate (%) | +3.0 | +3.5 | +1.2 | −0.6 | +1.9 |

ACSC, ambulatory care sensitive conditions.

Figure 1.

Emergency hospital admissions aged 65+ years per head of population aged 65+ years. ACSC, ambulatory care sensitive condition.

Figure 2.

Nominal and real (inflation adjusted) government net spend on social care for people aged 65+ years (£’000 s) per head of population aged 65+ years.

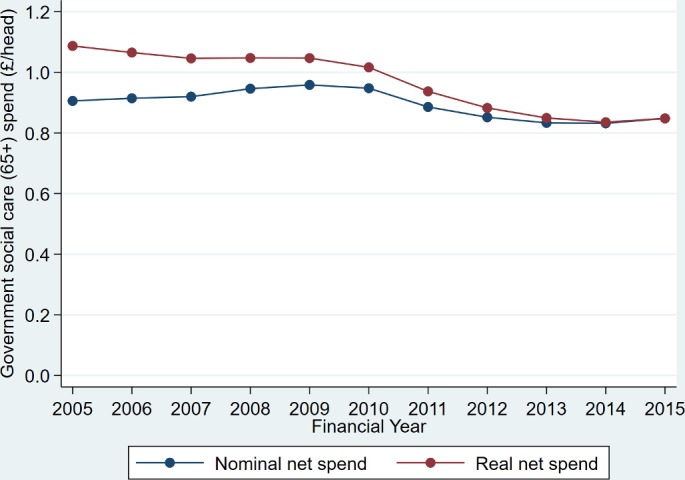

There is considerable variation between councils in the levels of spend on social care and emergency admissions per head of population (see figure 3). Rate of social care spend and emergency admissions are notably higher in the most deprived quintile.

Figure 3.

Government spend on social care (£’000 s), emergency and ACSC admissions per head of population (65+ years) by council and IDAOPI (deprivation) quintile. ACSC, ambulatory care sensitive condition; IDAOPI, Income Deprivation Affecting Older People Index.

Model results

Having adjusted for the other model covariates, we found no statistically significant relationship between the rate of government spend on social care within a council and our primary outcome variable, emergency hospital admissions (IRR 1.009, 95% CI 0.965 to 1.056)—see table 2. Likewise, we found no significant relationship with our secondary outcome, ambulatory care sensitive admissions (IRR 0.975, 95% CI 0.917 to 1.038)—see table 3.

Table 2.

Model results (outcome: emergency hospital admissions 65+ years, exposure: population aged 65+ years)

| Covariate | IRR | P>|z| | 95% CI | ||

| Time-varying effects | Real net spend on social care (within effect)*† | 1.009 | 0.410 | 0.965 to 1.056 | |

| Deaths‡ | 1.010 | <0.001 | 1.007 to 1.014 | ||

| Time invariant effects | Real net spend on social care (between effect)†§ | 1.138 | <0.001 | 1.079 to 1.200 | |

| Deprivation (IDAOPI) | Quintile 1 (ref) | 1.000 | – | – | |

| Quintile 2 | 1.059 | 0.048 | 1.000 to 1.121 | ||

| Quintile 3 | 1.145 | <0.001 | 1.099 to 1.193 | ||

| Quintile 4 | 1.156 | <0.001 | 1.088 to 1.228 | ||

| Quintile 5 | 1.226 | <0.001 | 1.148 to 1.310 | ||

| Year | 2005/2006 (ref) | 1.000 | – | – | |

| 2006/2007 | 1.024 | <0.001 | 1.012 to 1.037 | ||

| 2007/2008 | 1.034 | <0.001 | 1.021 to 1.047 | ||

| 2008/2009 | 1.090 | <0.001 | 1.076 to 1.105 | ||

| 2009/2010 | 1.143 | <0.001 | 1.121 to 1.165 | ||

| 2010/2011 | 1.167 | <0.001 | 1.141 to 1.194 | ||

| 2011/2012 | 1.179 | <0.001 | 1.148 to 1.212 | ||

| 2012/2013 | 1.183 | <0.001 | 1.152 to 1.216 | ||

| 2013/2014 | 1.175 | <0.001 | 1.139 to 1.211 | ||

| 2014/2015 | 1.230 | <0.001 | 1.189 to 1.273 | ||

| 2015/2016 | 1.203 | <0.001 | 1.168 to 1.240 | ||

| Constant | 0.107 | <0.001 | 0.089 to 0.130 | ||

*In-year difference from average spend in the local authority between 2005/2006 and 2015/2016.

†Per head population aged 65+ years.

‡Per 1000 population aged 65+ years.

§Average spend in the local authority between 2005/2006 and 2015/2016.

IDAOPI, Income Deprivation Affecting Older People Index.

Table 3.

Model results (outcome: ACS hospital admissions 65+ years, exposure: population aged 65+ years)

| Covariate | IRR | P>|z| | 95% CI | ||

| Time-varying effects | Real net spend on social care (within effect)*† | 0.975 | 0.790 | 0.917 to 1.038 | |

| Deaths‡ | 1.014 | <0.001 | 1.008 to 1.019 | ||

| Time invariant effects | Real net spend on social care (between effect)†§ | 1.230 | <0.001 | 1.138 to 1.330 | |

| Deprivation (IDAOPI) | Quintile 1 (ref) | 1.000 | – | – | |

| Quintile 2 | 1.100 | 0.001 | 1.038 to 1.165 | ||

| Quintile 3 | 1.234 | <0.001 | 1.169 to 1.303 | ||

| Quintile 4 | 1.269 | <0.001 | 1.188 to 1.356 | ||

| Quintile 5 | 1.352 | <0.001 | 1.226 to 1.491 | ||

| Year | 2005/2006 (ref) | 1.000 | – | – | |

| 2006/2007 | 1.018 | 0.019 | 1.003 to 1.033 | ||

| 2007/2008 | 1.031 | 0.001 | 1.013 to 1.050 | ||

| 2008/2009 | 1.090 | <0.001 | 1.069 to 1.112 | ||

| 2009/2010 | 1.138 | <0.001 | 1.102 to 1.174 | ||

| 2010/2011 | 1.202 | <0.001 | 1.159 to 1.247 | ||

| 2011/2012 | 1.235 | <0.001 | 1.182 to 1.290 | ||

| 2012/2013 | 1.197 | <0.001 | 1.145 to 1.252 | ||

| 2013/2014 | 1.188 | <0.001 | 1.133 to 1.244 | ||

| 2014/2015 | 1.302 | <0.001 | 1.237 to 1.371 | ||

| 2015/2016 | 1.281 | <0.001 | 1.226 to 1.337 | ||

| Constant | 0.015 | <0.001 | 0.011 to 0.020 | ||

*In-year difference from average spend in the local authority between 2005/2006 and 2015/2016.

†Per head population aged 65+ years.

‡Per 1000 population aged 65+ years.

§Average spend in the local authority between 2005/2006 and 2015/2016.

IDAOPI, Income Deprivation Affecting Older People Index.

Sensitivity analyses

We reproduced the models excluding the nine councils with the highest dfbeta values (>2 SD from 0) for the variable representing government spend on social care within councils. This did not alter the significance of the incident risk ratio for social care spend.

Similarly, reproducing the model with a random-effects formulation did not the alter significance of the incident risk ratio for social care spend.

Lagging the variable representing government spend on social care (within councils) and leading the variable representing mortality rate by one time unit did not alter the significance of the incident risk ratio for social care spend.

When we incorporated year as a linear covariate (rather than as a set of dummy variables), the incident risk ratio increased marginally and became statistically significant.

The incidence risk ratio for social care spend was not materially altered when alternative within-group correlation structures (exchangeable, unstructured and autoregressive order 1) were specified.

Online supplementary file 2 contains the model coefficient and 95% CI for our variable of interest in each of the sensitivity analyses described above.

bmjopen-2018-024577supp002.pdf (53.7KB, pdf)

Discussion

Key findings

Across our study population, government spend on social care for people aged 65 years and over fell by £472 m (6.2%) in real terms between 2005/2006 and 2015/2016. We conclude that this was not associated with an increase in emergency hospital admissions. This finding is at odds with both intuition and the perceptions of those working in acute hospitals. We will explore a range of potential (and interrelated) explanations for this effect.

The prima-facie explanation for the observed results is that social care provision is not an effective means of preventing emergency hospital admissions for older people. It is likely that individuals who have been affected by reductions in social care spend to date are those whose need levels are close to eligibility thresholds and therefore have the lowest ability to benefit. It does not necessarily follow therefore that further reductions in social care spend will not result in increases in emergency hospital admissions. Moreover, our finding should not be taken as evidence of the ineffectiveness of social care in more general respects. The effectiveness of social care with respect to quality of life, for example, has been studied elsewhere and while this evidence base remains limited, on balance it suggests that the provision of social care leads to quality of life benefits.23

Another explanation for the findings is that social care provision may avoid hospital admissions by improving the health status of older people but that these gains are offset as social workers and social care professionals identify unmet need and trigger a healthcare intervention leading to hospital admission. This could arise, for example, if a social care professional notices a deterioration in a patient’s health status, referring the patient to a general practitioner (GP) or emergency department. While the UK has a strong primary healthcare system and might be expected to manage clinical risks in these circumstances, GP services are under pressure and access to primary care remains a problem. These direct and countervailing effects may be reduced in tandem as social care spend is reduced. This mechanism has been proposed for other interventions that aimed, but failed to reduce emergency admissions in older people.24

A third explanation focuses on the effect of substituting government funded social care for privately funded social care and informal care. While substitution may not occur in all cases, privately funded social care and informal care may be allocated more efficiently than government-funded social care, offsetting the losses associated with those individuals who now receive no care. However, the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing suggests that the use of privately funded social care fell between 2004/2005 and 2014/2015 for those reporting problems with activities of daily living (eg, walking, bathing, dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (eg, cooking, shopping).25 While public and private provision have been falling informal care has increased substantially. A survey conducted by Department of Work and Pensions estimates that 8% (4.9 million) of people were informal carers in England in 2016.26 Since 2004 the average daily minutes of adult care provided by those aged 8 years or over has risen year on year.27 The gross value added of informal adult care in the UK increased by 45.8% between 2005 and 2014, from £39.0 billion to £56.9 billion.28 These figures demonstrate a substantial and sustained shift from public to informal care provision over the period of this study.

While healthcare services have been spared the severe funding cuts seen in other public services, healthcare services nonetheless report significant funding pressures. Many initiatives have sought to manage demand for emergency hospital admissions and a recent study demonstrated that thresholds for admission via emergency departments increased over the period from 2009/2010 to 2014/2015.29 These supply constraints and changes in clinical behaviour may explain why reductions in social care spend have not resulted in increases in emergency hospital admissions.

Finally, we consider the impact of substantial funding constraints on the efficiency of social care services. To accommodate cuts in funding, many social services departments have tightened need-based access criteria for services and have introduced reablement and preventative services to reduce long-term demand for care. This may have increased the efficiency of social care, improving the health status of service users and offsetting the losses to those who no longer receive government funded care. Local authorities facing the largest cuts may have undertaken the most radical redesign of services and achieved the greatest efficiency gains.

Limitations

Ecological studies of this type are susceptible to a number of forms of bias. However, our conservative modelling approach and the study’s statistical power imply that it is extremely unlikely that reductions in social care spend resulted in material increases in emergency admissions at a population level. None of the sensitivity analyses provided contrary evidence.

As with all observational studies, we must consider the possibility that our observed result can be explained by the omission of a key explanatory variable. Given the use of panel data, any influential omitted variable must be a time-varying effect operating within councils, which is strongly associated with our dependant variable and our variable of interest. One candidate is household income. However, income inequality in retired households has grown since 2009/2010 and over the same period councils with higher levels of deprivation have seen larger reductions in social care spend.30 We would expect these changes to amplify rather than obscure or repress any relationship between social care spend and emergency admissions.

Given the ecological nature of our study, we should consider the possibility that reductions in social care spend have indeed resulted in increases in emergency admissions, but that equivalent reductions in emergency hospital admissions have occurred in other groups of older people. We can think of no clear mechanism that might correspond to this theory.

In 2014/2015, the financial reporting framework used to collect data from councils on government spend on social care was substantially redesigned. The mapping of categories required to create consistent time series introduces the potential for error. However, our sensitivity analyses did not indicate that the results were substantially affected by the presence of outliers. A small number of councils were excluded from our analysis. While the rationale for the exclusions are clear and explicitly described, this process may have introduced bias.

While this study did not explicitly control for changes in the age profile or morbidity levels of the study population, the use of mortality rates as an independent variable adjusts for these factors indirectly.

Relation to existing literature

Unlike our study, the small number of previous studies which have explored the relationship between social spend or provision and healthcare use has found evidence of a substitution effect. A cross-sectional analysis using small area data in England found the cost effects of a transfer of resources from hospitals to care homes were broadly neutral, but this study predates the recent significant reductions in social care expenditure.8 A later study using panel data found delayed discharges from hospitals in England responded, if only weakly, to increases in the supply of care home beds.9 A Norwegian study, using patient level data, reported that after controlling for casemix, hospital and time fixed effects, higher levels of social care capacity were associated with reduced hospital length of stay.10 A 2012 study demonstrated interactions in the use of hospital care and social care for older people in England and that residents of care homes tended to use hospitals less frequently than people receiving home care.31 A working paper published by the Institute of Fiscal Studies concluded that cuts in government spending on social care had led to increases in attendances at English accident and emergency departments, but not to subsequent hospital admissions.32

Implications for policy and research

We recommend further work on this subject to verify or rebut our results, to test the credibility of the mechanisms we have proposed to explain our results or to identify and test alternative mechanisms. We have made the panel dataset available with this paper to allow others to replicate the study’s methods and explore alternative approaches to test the relationship between emergency hospital admissions and spend on social care.

Observational studies that operate at the patient level may provide insights into the relationship between social care spend and hospital admissions that cannot be obtained via ecological studies. Qualitative research could be used to explore the mechanisms by which social care influences healthcare use.

Policy makers should review schemes, such as the Better Care Fund, which are predicated on the belief that emergency hospital admissions can be reduced by increasing social care provision. Our analysis suggests that this approach is unlikely to succeed. Given the scale of the Better Care Fund, a comprehensive evaluation is warranted. Healthcare commissioners should consider alternative, evidence-based methods of moderating demand for emergency hospital care.

We note that the NHS’s latest social care funding initiative, the Improved Better Care Fund, aims to reduce hospital length of stay and delayed transfers of care rather than prevent emergency admissions. Further research should be carried out to test the limited evidence supporting this approach.

Conclusion

We found no evidence to support the view that reductions in government spend on social care since 2008 have led to increases in emergency hospital admissions in older people.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: PS, SB and SW conceived the research. PS assembled the data. PS and SW conducted the analysis and drafted the manuscript. PM and MAM offered advice on the selection of statistical model and reviewed the analysis. SB framed the analysis within a policy context. All authors reviewed and commented on the draft manuscripts.

Funding: NHS Midlands and Lancashire Commissioning Support Unit received payment from NHS Coventry and Rugby Clinical Commissioning Group to conduct the initial analysis that led to this paper.

Competing interests: SB is employed by NHS Walsall CCG which jointly commissions social care services for older people through the Better Care Fund. SB was previously employed by Coventry City Council, a commissioner and provider of social care for older people.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data can be accessed via the Dryad data repository at http://datadryad.org/ with the doi: 10.5061/dryad.30qp564.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Institute of Fiscal Studies & Nuffield Foundation. Central Cuts, Local Decision-Making: Changes in Local Government Spending and Revenues in England, 2009-10 to 2014-15. 2015. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/bns/BN166.pdf.

- 2. NHS Digital. Community Care Statistics, Referrals, assessments and packages of care for adults - England, 2007-2008, National summary. https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB01519 (18 Dec 2008).

- 3. NHS Digital. Community Care Statistics, Social Services Activity, England - 2013-14, Final release. https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB16133

- 4. NHS Digital. Hospital Accident and Emergency Activity 2016-17. https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB30112 (October 2017).

- 5. Office of National Statistics. National Population Projections 2016. 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationprojections/bulletins/nationalpopulationprojections/2016basedstatisticalbulletin

- 6. Kings Fund. Quarterly Monitoring Report 1. https://qmr.kingsfund.org.uk/2015/17/ (Oct 2015).

- 7. Thorlby R. Fact of Fiction? Social care cuts are to blame for the ’crisis' in hospital emergency departments, Nuffield Trust comment. (29 Jan 2015).

- 8. Forder J. Long-term care and hospital utilisation by older people: an analysis of substitution rates. Health Econ 2009;18:1322–38. 10.1002/hec.1438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gaughan J, Gravelle H, Siciliani L. Testing the bed-blocking hypothesis: does nursing and care home supply reduce delayed hospital discharges? Health Econ 2015;24:32–44. 10.1002/hec.3150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Holmås TH, Islam MK, Kjerstad E. Interdependency between social care and hospital care: the case of hospital length of stay. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:927–33. 10.1093/eurpub/cks171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Curry N, Ham C. Clinical and service integration. 2010. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/Clinical-and-service-integration-Natasha-Curry-Chris-Ham-22-November-2010.pdf

- 12. Department of Communities and Local Government & Department of Health. Integration and Better Care Fund planning requirements for 2017-19. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/integration-better-care-fund-planning-requirements.pdf

- 13. NHS Digital. HES Data Dictionary – Admitted Patient Care. 2017. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/media/25188/DD-APC-V10/pdf/DD-APC-V10.pdf

- 14. Purdy S, Griffin T, Salisbury C, et al. Ambulatory care sensitive conditions: terminology and disease coding need to be more specific to aid policy makers and clinicians. Public Health 2009;123:169–73. 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.11.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. NHS Digital. Adult Social Care Finance Return (ASC-FR) Guidance For the collection period. http://content.digital.nhs.uk/media/16585/ASC-FR-Guidance-201516/pdf/ASC-FR_Guidance_2015-16_v1.1.pdf

- 16. HM Treasury. GDP deflators at market prices and money GDP. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/gdp-deflators-at-market-prices-and-money-gdp-november-2017-autumn-budget-2017 (28 November 2017).

- 17. Office of National Statistics. Lower Super Output Area Mid-Year Population Estimates. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/lowersuperoutputareamidyearpopulationestimates (26 Oct 2017).

- 18. Majeed A, Bardsley M, Morgan D, et al. Cross sectional study of primary care groups in London: association of measures of socioeconomic and health status with hospital admission rates. BMJ 2000;321:1057–60. 10.1136/bmj.321.7268.1057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Department of Communities and Local Government. English Indices of Deprivation. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/english-indices-of-deprivation-2015 (30 September 2015).

- 20. Hilbe JM. Negatuve Binomial regression: Cambridge University Press, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cui J. QIC Program and Model Selection in GEE Analyses. Stata J 2007;7:209–20. 10.1177/1536867X0700700205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Seshamani M, Gray AM. A longitudinal study of the effects of age and time to death on hospital costs. J Health Econ 2004;23:217–35. 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2003.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sutcliffe K, Rees R, Dickson K, et al. The adult social care outcomes framework: A systematic review of systematic reviews to support its use and development. 2012. https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/Portals/0/PDF%20reviews%20and%20summaries/ASCOF%202012Sutcliffe%20report.pdf?ver=2013-11-14-144947-670

- 24. Steventon A, Bardsley M, Billings J, et al. An evaluation of the impact of community-based interventions on hospital use. 2011. https://www.nuffieldtrust.org.uk/research/an-evaluation-of-the-impact-of-community-based-interventions-on-hospital-use

- 25. English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. https://www.elsa-project.ac.uk/about-ELSA

- 26. Department for Work & Pensions. Family Resources Survey. 2017. https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/family-resources-survey-2

- 27. Office for National Statistics. Changes in the value and division of unpaid volunteering in the UK: 2000 to 2015. 2017. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/satelliteaccounts/articles/changesinthevalueanddivisionofunpaidcareworkintheuk/2000to2015#changes-in-the-division-of-unpaid-care-between-2000-and-2015-part-2-adult-care

- 28. Office for National Statistics. Household satellite accounts: 2005 to 2014, Chapter 3. 2016. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/nationalaccounts/satelliteaccounts/compendium/householdsatelliteaccounts/2005to2014/chapter3homeproducedadultcareservices#gross-value-added-of-informal-adult-care

- 29. Wyatt S, Child K, Hood A, et al. Changes in admission thresholds in English emergency departments. Emerg Med J 2017;34:773–9. 10.1136/emermed-2016-206213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Office of National statistics. Household disposable income and inequality in the UK: financial year ending 2016. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/incomeandwealth/bulletins/householddisposableincomeandinequality/financialyearending2016 (10 Jan 2017).

- 31. Bardsley M, Georghiou T, Chassin L, et al. Overlap of hospital use and social care in older people in England. J Health Serv Res Policy 2012;17:133–9. 10.1258/JHSRP.2011.010171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Crawford R, Stoye G, Zaranka B. The impact of cuts to social care spending on the use of Accident and Emergency departments in England, IFS Working Paper W18/15. 2018. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/wps/WP201815.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-024577supp001.pdf (55.4KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2018-024577supp002.pdf (53.7KB, pdf)