Abstract

Objectives

The ways patients cope with advanced cancer can influence their health-related quality of life (HRQoL). This study aims to examine the mediating role of positive and negative mood in the relationship between coping and HRQoL in patients with advanced lung cancer.

Methods

A consecutive sample of 261 patients (mean age: 59.99±9.53) diagnosed with stage III or IV lung cancer was recruited from the inpatient unit in a hospital that specialises in chest-related disease in Shanghai, China. Participants completed measurements including Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire, Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, and 5-level EuroQol 5-dimension instrument.

Results

Although the total effects of confrontation on HRQoL were not significant, competing indirect effects via mood were identified: (1) positive indirect effects through positive mood were found for confrontation on mobility, usual activities, pain/discomfort and overall utility index (indirect effect=0.01, 95% CI 0.003 to 0.03); (2) negative indirect effects through negative mood were found for confrontation on mobility, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression and overall utility index (indirect effect=−0.01, 95% CI −0.03 to −0.001). Resigned acceptance was negatively associated with HRQoL, and indirect effects via mood were identified: (1) negative indirect effects through positive mood were found for resigned acceptance on mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and overall utility index (indirect effect=−0.01, 95% CI −0.03 to −0.003); (2) negative indirect effects through negative mood were found for resigned acceptance on domains of HRQoL and overall utility index (indirect effect=−0.04, 95% CI −0.06 to −0.02).

Conclusions

Confronting advanced lung cancer can fuel ambivalent emotional experiences. Nevertheless, accepting the illness in a resigned way can be maladaptive for health outcomes. The findings suggest interventions that facilitate adaptive coping, reduce negative mood and enhance positive mood, as this could help to improve or maintain HRQoL in patients with advanced lung cancer.

Keywords: coping, quality of life, lung cancer, mood

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The study addressed health-related quality of life (HRQoL), an important health outcome of treatment for advanced lung cancer, and examined the psychological factors associated with HRQoL.

The study examined the mediating role of positive and negative mood in the relationship between coping and a range of health outcomes (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression, overall HRQoL), which identifies the potential pathways between coping and HRQoL in patients with advanced lung cancer.

Consecutive sampling could compromise the generalisability of the findings.

Cross-sectional design.

Introduction

During the past decade, lung cancer has become the most common incident cancer and the leading cause of cancer mortality in China and in many other countries.1 2 The diagnosis of lung cancer can result in enormous stress for patients and their families, such as symptom burden,3 decisions about treatment options4 and financial concerns.5 The quality of life is significantly affected in patients with an advanced lung cancer.6 The curative treatments are limited for advanced lung cancer, and the 5-year survival rate of lung cancer is 16.1% in China.7 Improving or maintaining quality of life is the main focus of treatment. The prognostic value of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with lung cancer is supported by a range of studies.8 9

Previous research has investigated sociodemographic, clinical and psychosocial correlates of HRQoL in cancer patients.10 Common risk factors identified from previous studies included older age, being female, financial burden and advanced stage.11 Specifically, coping strategy is indicated to contribute to HRQoL in patients with advanced cancer.12 13 The manner in which patients cope with the life-threatening illness may affect patients’ emotional state, perceptions of illness and health behaviours, which can have an impact on the treatment course and ultimately health outcomes.14 Two coping strategies, confrontation and acceptance, have received considerable attention in patients with a life-threatening illness.14–17

Confrontation is defined as a set of coping strategies that involves seeking information and advice from various sources, seeking support from family and friends and engaging in decision making.15 It is actively oriented, which is indicated to be adaptive for cancer patients and associated with lower negative mood18–20 and better quality of life.16 17 However, other studies found insignificant associations between confrontation and health outcomes among cancer patients.14 21 22 For instance, Nipp et al 14 studied 350 patients with incurable lung or gastrointestinal cancer, and found that using active coping was not associated with psychological distress or quality of life. It is suggested that confrontation could direct one’s attention to the disease and its side effects, making it less effective in coping with cancer.15 17

Acceptance is regarded as a strategy to cope with unchangeable or uncontrollable negative events.23 Resigned acceptance is a form of acceptance, specifically, a passive form of acceptance, in which individuals accept the stressful situation and give up endeavours or hope to deal with it.23 24 It is different from the concept of acceptance in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, which is a form of active acceptance and characterised by active embracing of thoughts and feelings without unnecessary attempts to alter them.25 Research shows that resigned acceptance could be maladaptive, which was associated with less favourable outcomes, such as negative mood and lower quality of life, in cancer patients and survivors.21 26 27

Confrontation and resigned acceptance may be associated with cultural views of illness in the Chinese cancer population. Confucianism and Taoism are two dominant philosophical tenets in Chinese culture.28 Confucian beliefs emphasise the importance of life, and death is a taboo and perceived as a negative event.29 Consistent with this, the majority of patients and their families in China would choose to continue curative treatments to sustain and prolong life until the end of life.30 On the other hand, cancer and other illness are believed to be an act of Ming (also known as fate) in the Taoist belief system.28 The fatalistic attitude towards cancer may lead to resigned acceptance, which may affect health outcomes during the illness trajectory.28

Although research shows that coping is associated with HRQoL in cancer patients, the mechanism of the link between coping and HRQoL remains largely unexamined in cancer patients. Preliminary exploration suggests that mood may be a potential pathway between coping and health outcomes.31–35 Folkman and Greer developed a model of stress and coping for serious illness, and Roberts et al revised the model based on studies among patients with advanced cancer.36 37 The models highlight the association between coping and emotional outcomes in the face of cancer, as the way patients cope with the stressors can influence the emotional outcomes, leading to positive and/or negative emotion.36 37 On the other hand, studies indicate that mood is linked to health outcomes (eg, HRQoL) in cancer patients and survivors.27 38 39 Negative and positive mood involves different physiological responses (eg, nervous, endocrine and immune system functioning), which can influence overall physical health.40 41 Additionally, the broaden-and-build theory of positive mood indicates that positive mood can broaden one’s attention scope and thought-action repertoires, which could be beneficial for physical health. In contrast, negative mood can fuel a narrowed, socially isolating thought-action tendencies, which could result in poor health outcomes.42 43 Given that coping strategies are related to mood, and that mood is related to HRQoL, it is possible that mood may be a mediational pathway between coping and HRQoL. In a prospective study among HIV caregivers, higher social coping predicted an increase in positive affect, which decreased levels of physical symptoms, whereas higher cognitive avoidance predicted enhanced negative affect, which resulted in higher levels of physical symptoms.33 However, in the context of advanced cancer, to our knowledge, no study has examined the pathways between coping and HRQoL through mood. Since patients with advanced cancer can encounter numerous stresses, understanding the effect of coping on health and identifying the pathways through which patients maintain health and quality of life can provide important insights for clinical practice and interventions.

In summary, the current study addresses the relationships between coping, mood and HRQoL among patients with advanced lung cancer. Specifically, we examined the effect of confrontation and resigned acceptance coping on positive mood, negative mood and HRQoL. We also tested the mediating role of positive and negative mood in the relationship between coping and HRQoL among Chinese patients with advanced lung cancer.

Method

Study setting and participants

Participants were recruited from the inpatient unit of the department of chest-oncology medicine at a public hospital that specialises in chest-related disease in Shanghai, China. The hospital is well recognised for its expertise, resources and treatments for chest-related disease. A large number of patients with lung cancer in east China come to this hospital and receive treatment there. Patients were eligible for the study if they (1) were ≥18 years, (2) had been diagnosed with lung cancer, (3) had an expected survival time >3 months, (4) had no significant cognitive impairment and (5) were able to communicate with interviewers. Studies show that cancer patients may experience a steep decline in HRQoL during the last 3 months of life.44 Therefore, we purposefully included only those with an expected survival time of at least 3 months. Those who could not understand the questions were excluded from the sample. Between June 2016 and July 2016, 328 patients met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study.

Data collection was conducted by trained undergraduate students majoring in medicine and public health. Doctors and nurses in the inpatient unit of the department of chest-oncology medicine screened the eligible patients based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and researchers approached them and introduced the study. Those who agreed to participate in the study provided informed consent. Face-to-face interviews were then conducted. Disease and treatment information was extracted from medical records. In accordance with our study aim, we focused on 267 patients with advanced-stage lung cancer (stage III or IV), and the 261 participants who provided full information on the main study variables (coping, mood and HRQoL) were included in the data analysis. A flowchart of the sample selection procedure is presented in online supplementary figure 1.

bmjopen-2018-023672supp001.pdf (111.5KB, pdf)

Participant and public involvement

The participants were not involved in the design or recruitment process of this study. However, the patients in department of oncology who worked with the second author (an oncologist) provided insights for the development of the research question. Permission to conduct the study was obtained from relevant hospital authorities and participants.

Measures

Health-related quality of life

The 5-level EuroQol 5-dimension (EQ-5D-5L) was used to measure HRQoL in this study.45 It contained five questions to assess five health dimensions, as experienced in the recent days, namely mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. Respondents rated the severity on five levels ranging from 1 (no) to 5 (very severe). In the current study, EQ-5D-5L domain scores and overall utility index were calculated. Domain scores were recoded reversely based on the original levels of each domain, with higher scores indicating better quality in the domain. EQ-5D-5L utility index was calculated based on value sets developed by the EuroQol Group. To our knowledge, no value sets have been developed in a Chinese representative sample for the calculation of utility index, so in this study, utility index was calculated based on value sets weighted from a representative sample of the English general population.46 The EQ-5D-5L utility index ranged from −1 to 1, with 1 representing full health, 0 representing a state of death and negative values representing a state worse than death.

Coping

Two subscales of the Chinese version of the Medical Coping Modes Questionnaire (MCMQ) were used to measure confrontation and resigned acceptance coping strategies for lung cancer. MCMQ was developed by Feifel et al 15 among patients with a variety of life-threatening and chronic illnesses, and it is widely used for assessing coping strategies in patients in China.17 47 Acceptance-resignation subscale had five items, and confrontation subscale had nine items.15 Sample items in acceptance-resignation subscale were as follows: ‘there is nothing you can do about your illness’, ‘you don’t care what happens to you’ and ‘feel there is really no hope for your recovery.’ Sample items in confrontation subscale were as follows: ‘obtained information through books, magazines, and newspapers in the past several months’, ‘try to talk about your illness with friends or relatives’ and ‘be involved in decisions regarding your treatment.’ In addition to original confrontation subscale with eight items, we added one item assessing how often participants ‘obtained information through the Internet and new media in the past several months, as the Internet and new media have become important sources of information that supplement books, magazines and newspaper. All the items were rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (very often). The mean score of each coping strategy was calculated, with a higher score indicating a higher probability of using that particular coping strategy. The Cronbach’s α coefficients of confrontation and resigned acceptance in this study were 0.72 and 0.71, respectively.

Mood

Mood was measured using the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS).48 The PANAS contained items to describe 10 positive affects (eg, inspired, excited and determined) and 10 negative affects (eg, afraid, upset and distressed). Respondents rated their experiences of each affect during the past 2 weeks on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very slightly) to 5 (extremely). The mean scores of items on the two subscales were calculated for positive mood and negative mood, respectively. In the current study, the Cronbach’s α coefficients of negative mood and positive mood were 0.91 and 0.86, respectively.

Covariates

Sociodemographic factors included age, gender, education (elementary school or lower, middle school, high school, college or higher) and marital status (married, single, divorced, widowed). Perceived cancer-related financial burden was assessed by the question, ‘Have your disease and treatment caused you and your family financial difficulty?’ and participants answered on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (No) to 4 (Very much). Clinical factors included time of diagnosis, cancer stage, lung cancer type (adenocarcinoma, squamous, poorly differentiated, small cell, not otherwise specified) and treatment history (surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, targeted therapy).

Data analysis

First, descriptive statistics were presented for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, and main study variables. Mean and SD, or frequency and percentage, were computed for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Independent t test, analysis of variance and post-hoc comparison were conducted to analyse the effect of sociodemographic and clinical factors on positive mood, negative mood and HRQoL (see online supplementary table 1). Correlational analyses were performed to examine the associations between the continuous variables.

Second, hierarchical, multiple, linear regression analyses were employed to examine the relationships among coping, mood and HRQoL. The hierarchical regressions with HRQoL (domain scores and EQ-5D utility index) as a dependent variable involved three steps: in step one, gender, age, cancer stage and covariates that were significantly correlated with mood and HRQoL (ie, financial burden, lung cancer type, a history of radiotherapy) were entered; in step two, confrontation and resigned acceptance were entered; in step three, positive and negative mood were entered.

Third, the mediating effects of positive and negative mood in the relationship between coping and HRQoL were tested using the MEDIATE macro for SPSS developed by Preacher and Hayes.49 Bootstrapping techniques using 5000 samples were used for the analysis, which was regarded as providing a more reliable estimate for the small sample size. Significant indirect effect was indicated by a 95% CI of indirect effect without including zero. Power analyses indicated that in a model with two parallel mediators, a sample of 260 has 80% power to detect a 95% CI of indirect effect, assuming correlations of r=0.20 between independent variable, the dependent variable and the mediators. Schoemann et al suggest that this power analytic method is an appropriate approach for determining power and sample size in mediation models.50 All tests were two-tailed, and a p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the samples are shown in table 1. A total sample of 261 participants had a mean age of 59.99 years (SD=9.53). Males represented 70.1% of the samples. Most participants were married (94.6%) and perceived a slight to very severe cancer-related financial burden (85.8%). More than half of the participants had been diagnosed in the past 6 months (55.2%). More than 90% of the participants had ever received chemotherapy (96.6%), whereas a certain proportion had ever received surgery (23.4%), radiotherapy (23.4%) or targeted therapy (14.6%).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics

| Variables | M(SD)/n (%) |

| Age (years) | 59.99 (9.53) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 183 (70.1%) |

| Female | 78 (29.9%) |

| Education | |

| Elementary school or lower | 55 (21.1%) |

| Middle school | 91 (34.9%) |

| High school | 66 (25.3%) |

| College or higher | 49 (18.8%) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 247 (94.6%) |

| Single/divorced/widowed | 14 (5.4%) |

| Perceived cancer-related financial burden | |

| None | 37 (14.2%) |

| Slight | 100 (38.3%) |

| Moderate | 63 (24.1%) |

| Severe | 36 (13.8%) |

| Very severe | 25 (9.6%) |

| Time since diagnosis* | |

| <6 months | 144 (55.2%) |

| 6–12 months | 32 (12.3%) |

| 12–24 months | 31 (11.9%) |

| >24 months | 46 (17.6%) |

| Stage | |

| III | 82 (31.4%) |

| IV | 179 (68.6%) |

| Lung cancer type | |

| NSC—adenocarcinoma | 140 (53.6%) |

| NSC—squamous | 47 (18.0%) |

| NSC—poorly differentiated | 24 (9.2%) |

| NSC—others | 7 (2.7%) |

| Small cell | 43 (16.5%) |

| Treatment history | |

| Received surgery | |

| Yes | 61 (23.4%) |

| No | 200 (76.6%) |

| Received chemotherapy | |

| Yes | 252 (96.6%) |

| No | 9 (3.4%) |

| Received radiotherapy | |

| Yes | 61 (23.4%) |

| No | 200 (76.6%) |

| Received targeted therapy | |

| Yes | 38 (14.6%) |

| No | 223 (85.4%) |

*For time since diagnosis, the sum of number is not 261 due to missing data.

NSC, non-small cell.

Coping, mood and HRQoL

Pearson correlation analysis was performed to examine the relationships between coping, mood and HRQoL (see table 2). A small and positive correlation was observed between confrontation coping and positive mood (r=0.21). Resigned acceptance was moderately and positively correlated with negative mood (r=0.46), but moderately and inversely correlated with positive mood (r=−0.27). Use of resigned acceptance was correlated with more difficulties in mobility (r=−0.21), self-care (r=−0.19), usual activities (r=−0.19), pain/discomfort (r=−0.19), anxiety/depression (r=−0.41) and lower EQ-5D utility index (r=−0.28).

Table 2.

Correlation among coping, affect and HRQOL

| M (SD) | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

| 1. Confrontation | 2.37 (0.49) | 1 | ||||||||

| 2. Resigned acceptance | 1.92 (0.62) | −0.03 | 1 | |||||||

| 3. Positive mood | 2.40 (0.76) | 0.21** | −0.27** | 1 | ||||||

| 4. Negative mood | 1.84 (0.76) | 0.11 | 0.46** | −0.11 | 1 | |||||

| 5. Mobility | 4.32 (0.99) | −0.05 | −0.21** | 0.19** | −0.28** | 1 | ||||

| 6. Self-care | 4.58 (0.86) | −0.06 | −0.19** | 0.15* | −0.28** | 0.78** | 1 | |||

| 7. Usual activities | 4.24 (0.97) | −0.10 | −0.19** | 0.16* | −0.27** | 0.78** | 0.73** | 1 | ||

| 8. Pain/discomfort | 3.98 (0.87) | −0.08 | −0.19** | 0.14* | −0.28** | 0.45** | 0.43** | 0.46** | 1 | |

| 9. Anxiety/depression | 4.22 (0.73) | −0.03 | −0.41** | 0.19** | −0.50** | 0.21** | 0.21** | 0.25** | 0.27** | 1 |

| 10. EQ-5D utility index | 0.80 (0.19) | −0.10 | −0.28** | 0.20** | −0.38** | 0.84** | 0.82** | 0.84** | 0.69** | 0.45** |

*p<0.05, **p<0.01.

Scale range: confrontation, resigned acceptance: 1 (never) to 4 (very often); positive mood, negative mood: 1 (very slightly) to 5 (extremely); mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression: 1 (very severe) to 5 (no); EQ-5D utility index: −1 (worse than death) to 1 (full health).

HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

Hierarchical regression analyses were used to examine the relationship of confrontation and resigned acceptance coping with positive mood, negative mood and HRQoL (see table 3). Age, gender, cancer stage and significant correlates of mood and/or HRQoL (p<0.05), including perceived cancer-related financial burden, a history of radiotherapy and lung cancer type (poorly differentiated non-small cell, small cell, other non-small cell), were controlled in the hierarchical regression analyses. Regarding positive mood, in addition to covariates, confrontation and resigned acceptance were found to be significant factors, as confrontation was associated with higher positive mood (β=0.19, p=0.002), whereas resigned acceptance was associated with lower positive mood (β=−0.25, p<0.001). Regarding negative mood, in addition to covariates, confrontation and resigned acceptance were significant factors, as use of confrontation (β=0.11, p=0.040) and resigned acceptance (β=0.44, p<0.001) was associated with higher negative mood.

Table 3.

Multiple regression results for predictors of mood and HRQOL

| Positive mood | Negative mood | Mobility | Self-care | Usual activities | Pain/discomfort | Anxiety/depression | EQ-5D utility index | |||||||||

| β* | P value | β* | P value | β* | P value | β* | P value | β* | P value | β* | P value | β* | P value | β* | P value | |

| Step 1 | ||||||||||||||||

| Age | −0.15 | 0.021 | −0.04 | 0.53 | −0.13 | 0.040 | −0.13 | 0.046 | −0.06 | 0.31 | −0.07 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.91 | −0.10 | 0.09 |

| Gender† | −0.07 | 0.32 | 0.05 | 0.40 | −0.07 | 0.29 | −0.06 | 0.35 | −0.09 | 0.15 | −0.01 | 0.85 | 0.02 | 0.76 | −0.03 | 0.68 |

| Financial burden‡ | −0.14 | 0.032 | 0.30 | <0.001 | −0.16 | 0.010 | −0.15 | 0.017 | −0.20 | 0.002 | −0.15 | 0.018 | −0.25 | <0.001 | −0.22 | 0.001 |

| Cancer stage§ | −0.09 | 0.16 | −0.07 | 0.22 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 0.05 | 0.46 | 0.03 | 0.67 | 0.04 | 0.58 | 0.04 | 0.51 | 0.04 | 0.53 |

| Cancer type-other non-small cell (Reference) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||||||

| Cancer type- undifferentiated¶ | 0.01 | 0.93 | −0.03 | 0.58 | −0.07 | 0.26 | −0.08 | 0.19 | −0.12 | 0.053 | −0.08 | 0.19 | −0.04 | 0.51 | −0.14 | 0.027 |

| Cancer type-small cell¶ | −0.08 | 0.21 | −0.01 | 0.85 | 0.05 | 0.44 | 0.03 | 0.66 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.025 | 0.07 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 0.12 |

| Received radiotherapy** | −0.03 | 0.63 | 0.16 | 0.009 | −0.17 | 0.006 | −0.19 | 0.003 | −0.14 | 0.026 | −0.20 | 0.002 | −0.07 | 0.24 | −0.20 | 0.001 |

| ΔR2 | 0.054 | 0.141 | 0.079 | 0.081 | 0.097 | 0.094 | 0.080 | 0.124 | ||||||||

| Step 2 | ||||||||||||||||

| Confrontation | 0.19 | 0.002 | 0.11 | 0.040 | −0.05 | 0.40 | −0.05 | 0.39 | −0.07 | 0.25 | −0.07 | 0.29 | −0.01 | 0.81 | −0.08 | 0.17 |

| Resigned acceptance | −0.25 | <0.001 | 0.44 | <0.001 | −0.16 | 0.013 | −0.15 | 0.019 | −0.16 | 0.012 | −0.14 | 0.029 | −0.41 | <0.001 | −0.22 | <0.001 |

| ΔR2 | 0.098 | 0.191 | 0.025 | 0.023 | 0.027 | 0.021 | 0.155 | 0.053 | ||||||||

| Step 3 | ||||||||||||||||

| Positive mood | 0.16 | 0.013 | 0.12 | 0.078 | 0.14 | 0.026 | 0.14 | 0.029 | 0.10 | 0.076 | 0.17 | 0.005 | ||||

| Negative mood | −0.22 | 0.003 | −0.20 | 0.006 | −0.17 | 0.020 | −0.20 | 0.005 | −0.36 | <0.001 | −0.28 | <0.001 | ||||

| ΔR2 | 0.053 | 0.039 | 0.036 | 0.044 | 0.093 | 0.076 | ||||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.120 | 0.307 | 0.118 | 0.103 | 0.122 | 0.121 | 0.298 | 0.218 | ||||||||

The bold values indicate the significance of β.

*Standardised coefficients.

†0, Male; 1, Female.

‡Range: 1 (no difficulty) to 5 (very much).

§1, stage III; 2, stage IV.

¶Other non-small cell lung cancers was the reference group.

**0, No; 1, Yes.

HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

Regarding the EQ-5D domain scores, after controlling sociodemographic and clinical covariates, confrontation was not associated with the domain scores, whereas resigned acceptance was inversely associated with all domains. Positive mood was associated with less difficulty in mobility, usual activities, pain/discomfort, but not associated with self-care and anxiety/depression. Negative mood was associated with more difficulty in all domains of HRQOL.

Regarding EQ-5D utility index, after controlling sociodemographic and clinical covariates, resigned acceptance was inversely associated with EQ-5D utility index (β=−0.22, p<0.001), whereas confrontation was not associated with EQ-5D utility index. Moreover, the effects of mood on EQ-5D utility index were significant, as positive mood was associated with higher EQ-5D utility index (β=0.17, p=0.005), whereas negative mood was associated with lower EQ-5D utility index (β=−0.28, p<0.001).

Mediating effect of mood on the association between coping and HRQoL

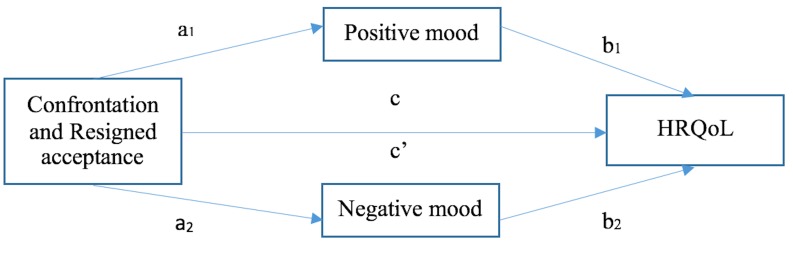

The MEDIATE macro was used to examine the mediating effect of mood in the relationship between coping and HRQoL, controlling for age, gender, cancer stage, perceived cancer-related financial burden, history of radiotherapy and lung cancer type (poorly differentiated non-small cell, small cell, other non-small cell). The indirect effect (ab) was estimated as the product of regression coefficients predicting mood from each coping strategy (a), and HRQoL from mood (b) (see figure 1). Bootstrapping techniques using 5000 samples revealed significant indirect effects for confrontation and resigned acceptance on HRQoL through positive and negative mood, respectively. The results are presented in table 4.

Figure 1.

Positive and negative mood as mediators of the association between coping and HRQoL. HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

Table 4.

Mediation model testing the direct and indirect effects of coping on HRQOL via mood

| Outcome | Predictor | Mediator | Path a | Path b | Path ab: indirect effect of coping on HRQOL | Path c’: Direct effect of coping on HRQOL | Path c: Total effect of coping on HRQOL | |

| Coef (SE) | Coef (SE) | Coef (SE) | 95% CI | Coef (SE) | Coef (SE) | |||

| HRQOL | Confrontation | Positive mood | 0.30** (0.09) | 0.04** (0.01) | 0.01 (0.01) | (0.003 to 0.03) | −0.03 (0.02) | −0.03 (0.02) |

| Negative mood | 0.17* (0.08) | −0.07*** (0.02) | −0.01 (0.01) | (−0.03 to 0.001) | ||||

| Resigned acceptance | Positive mood | −0.31*** (0.08) | −0.01 (0.01) | (−0.03 to 0.003) | −0.02 (0.02) | −0.07*** (0.02) | ||

| Negative mood | 0.54*** (0.07) | −0.04 (0.01) | (−0.06 to 0.02) | |||||

| Mobility | Confrontation | Positive mood | 0.30** (0.09) | 0.21* (0.08) | 0.06 (0.03) | (0.01 to 0.13) | −0.12 (0.13) | −0.10 (0.12) |

| Negative mood | 0.17* (0.08) | −0.28** (0.09) | −0.05 (0.03) | (−0.12 to 0.002) | ||||

| Resigned acceptance | Positive mood | −0.31*** (0.08) | −0.06 (0.03) | (−0.13 to 0.01) | −0.03 (0.11) | −0.25* (0.10) | ||

| Negative mood | 0.54*** (0.07) | −0.15 (0.06) | (−0.27 to 0.05) | |||||

| Self-care | Confrontation | Positive mood | 0.30** (0.09) | 0.13 (0.07) | 0.04 (0.03) | (−0.003 to 0.10) | −0.09 (0.11) | −0.09 (0.11) |

| Negative mood | 0.17* (0.08) | −0.23** (0.08) | −0.04 (0.03) | (−0.10 to 0.002) | ||||

| Resigned acceptance | Positive mood | −0.31*** (0.08) | −0.04 (0.03) | (−0.10 to 0.003) | −0.04 (0.10) | −0.21* (0.09) | ||

| Negative mood | 0.54*** (0.07) | −0.14 (0.05) | (−0.24 to 0.05) | |||||

| Usual activities | Confrontation | Positive mood | 0.30** (0.09) | 0.18* (0.08) | 0.05 (0.03) | (0.01 to 0.12) | −0.16 (0.12) | −0.14 (0.12) |

| Negative mood | 0.17* (0.08) | −0.22* (0.09) | −0.04 (0.02) | (−0.09 to 0.001) | ||||

| Resigned acceptance | Positive mood | −0.31*** (0.08) | −0.06 (0.03) | (−0.12 to 0.01) | −0.07 (0.11) | −0.25* (0.10) | ||

| Negative mood | 0.54*** (0.07) | −0.12 (0.05) | (−0.22 to 0.02) | |||||

| Pain/Discomfort | Confrontation | Positive mood | 0.30** (0.09) | 0.16* (0.07) | 0.05 (0.03) | (0.004 to 0.11) | −0.12 (0.11) | −0.12 (0.11) |

| Negative mood | 0.17* (0.08) | −0.23** (0.08) | −0.04 (0.02) | (−0.10 to 0.001) | ||||

| Resigned acceptance | Positive mood | −0.31*** (0.08) | −0.05 (0.03) | (−0.11 to 0.005) | −0.02 (0.10) | −0.19* (0.09) | ||

| Negative mood | 0.54*** (0.07) | −0.13 (0.05) | (−0.23 to 0.04) | |||||

| Anxiety / Depression | Confrontation | Positive mood | 0.30** (0.09) | 0.10 (0.05) | 0.03 (0.02) | (−0.003 to 0.74) | 0.01 (0.08) | −0.02 (0.08) |

| Negative mood | 0.17* (0.08) | −0.34*** (0.06) | −0.06 (0.03) | (−0.13 to 0.003) | ||||

| Resigned acceptance | Positive mood | −0.31*** (0.08) | −0.03 (0.02) | (−0.07 to 0.003) | −0.26** (0.07) | −0.48*** (0.07) | ||

| Negative mood | 0.54*** (0.07) | −0.18 (0.04) | (−0.27 to to 0.11) | |||||

Age, gender, financial burden, disease stage, lung cancer type and history of radiotherapy were controlled in the mediation model. All coefficients (a, b, c’, c) were unstandardised coefficients.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, *** p<0.001.

HRQoL, health-related quality of life.

Although the total effects of confrontation on EQ-5D domains scores and utility index were not significant, competing indirect effects via mood were identified. On one hand, positive indirect effects were found for confrontation on mobility (point estimate=0.06, SE=0.03, 95% CI [0.01 to 0.13]), usual activities (point estimate=0.05, SE=0.03, 95% CI [0.01 to 0.12]), pain/discomfort (point estimate=0.05, SE=0.03, 95% CI [0.004 to 0.11]) and overall utility index (point estimate=0.01, SE=0.01, 95% CI [0.003 to 0.03]) through positive mood. On the other hand, negative indirect effects were found for confrontation on mobility (point estimate=−0.05, SE=0.03, 95% CI [−0.12 to –0.002]), pain/discomfort (point estimate=−0.04, SE=0.02, 95% CI [−0.10 to –0.001]), anxiety/depression (point estimate=−0.06, SE=0.03, 95% CI [−0.13 to –0.003]) and overall utility index (point estimate=−0.01, SE=0.01, 95% CI [−0.03 to –0.001]) through negative mood. The direct effects of confrontation on EQ-5D domains scores and utility index were not significant.

Resigned acceptance has a significant negative total effect on EQ-5D domains scores and utility index. Furthermore, indirect effects of resigned acceptance on HRQoL via positive and negative mood were identified. Use of resigned acceptance was associated with decrease in positive mood and increase in negative mood, which could lead to more difficulty in mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort, anxiety/depression and overall utility index (indirect effect via positive mood: point estimate=−0.01, SE=0.01, 95% CI [−0.03 to –0.003]; indirect effect via negative mood: point estimate=−0.04, SE=0.01, 95% CI [−0.06 to –0.02]).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the relationship between coping, positive and negative mood and HRQoL, and the mediating role of mood in the relationship between coping and HRQoL among patients with advanced cancer. The findings of this study indicate that examining the pathway via positive and negative mood can generate a new understanding of the effect of coping on HRQoL among patients with advanced lung cancer, regardless of sociodemographic and clinical factors. The confrontation coping strategy was not directly associated with domains of HRQoL or overall HRQoL, but two significant indirect pathways via mood were identified. On one hand, confrontation had positive indirect effects on mobility, usual activities, pain and overall HRQoL via positive mood; on the other hand, confrontation had negative indirect effects on mobility, pain, anxiety and overall HRQoL via negative mood; positive and negative indirect effects could counteract, resulting in a nonsignificant total effect. In contrast, use of resigned acceptance coping was associated with an increase in negative mood and a decrease in positive mood, which could in turn result in more difficulty in mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and poor overall HRQoL. On the whole, this is a unique finding that indicates the ambivalence of confrontation and the maladaptive nature of resigned acceptance among patients with advanced lung cancer.

The mean EQ-5D utility index in the current study was found to be 0.80, which was comparable to a study among patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer in China with a utility index of 0.81.51 Consistent with previous studies, patients perceiving higher financial burden were more likely to report poor HRQoL compared with those perceiving lower financial burden related to cancer.11 52 Financial burden may restrict access to some drugs and treatment,52 and it may also lead to a sense of guilt for relying on families,29 which may affect health outcomes.

The current findings support the theory of stress and coping in the context of advanced cancer by indicating that coping can play a role in adapting to the experience of lung cancer, which could in turn influence emotional and health outcomes.36 37 The current study is in line with previous studies indicating that resigned acceptance was associated with less favourable outcomes.21 26 Resigned acceptance is related to the fatalistic attitude towards illness in traditional Taoist beliefs.28 Giving up control in the actual situation, or even other aspects of life, and holding negative expectations about the future could be associated with low levels of positive mood, and increase negative mood, which contributes to poor health outcomes in patients with advanced cancer.

Confrontation was found to be associated with increased positive and negative mood. In the current study, confrontation was characterised by attempts such as seeking information and support from various sources and being involved in decision making. Through such efforts, patients may regain a sense of control and redirect energy to constructive actions during treatment and daily living, which might facilitate the occurrence of positive mood. However, it is also possible that individuals could encounter various stressful decisions and pieces of information when they actively confront the advanced disease, which might lead to negative mood.

Our findings are in line with other studies reporting a nonsignificant association between confrontation and HRQoL among cancer patients.14 21 22 Particularly, the findings on the mediating role of mood can help clarify the mechanisms underlying the nonsignificant association. The coexisting positive and negative indirect effect via mood could counteract one another, resulting in a null, or weak, total effect of confrontation on HRQoL. The ambivalence of confrontation may also reflect the effect of fighting attitude towards life-threatening illness in Chinese population, in which the patients and their families would seek, try and continue available curative treatments to sustain and prolong life. Even though actively confronting the advanced cancer may have some benefits (eg, sense of control, constructive actions and skills), it may also remind patients of the potential incurable nature of advanced cancer and increase distress.

This study indicated that mood can be a pathway between coping and health outcomes. One explanation is related to physiology of mood,53 as positive and negative mood are associated with physiological levels in different directions, which can lead to different health outcomes. The second explanation is related to thought-action repertoires.43 Negative mood is suggested to narrow the thought-action repertoires and increase unhealthy lifestyle and social isolation,43 54 which could result in poor health outcomes. In contrast, positive affect is suggested to broaden the scope of attention and thought-action repertoires and build up personal and social resources,43 which could be beneficial to health outcomes. The third explanation is related to attributional interpretation.33 HRQoL refers to a self-perceived health status, and it is possible that participants in a negative mood tend to perceive lower health status (more difficulties in daily living and symptoms) than those in a positive mood.

This study has some limitations. First, causality on the relationships between coping, mood and HRQoL could not be drawn out from this cross-sectional study. Second, although MCMQ measured three coping strategies (ie, confrontation, acceptance-resignation and avoidance), reliability of avoidance, indicated by Cronbach’ α coefficient, was low in the current study. This restricted us from analysing the effect of the avoidance strategy. Third, the PANAS mostly measured the high-activated positive and negative affect.55 Further study is suggested to investigate the relationship between resigned acceptance and low-activated mood (eg, peace and calm). Fourth, although EuroQol 5-dimension was used to measure HRQoL among patients with advanced cancer in a range of studies,51 56 the measurement properties of the instrument is needed to be examined further in patients with advanced cancer.57 Finally, the sample was recruited from one hospital in China, which could compromise the generalisability of the findings.

Our finding that coping strategies is associated with mood and quality of life suggest that oncology providers need to pay attention to how patients are coping with the advanced cancer. Despite fostering realistic expectation for treatment and prognosis, oncology providers should watch for resigned acceptance and help the patients to learn what they can still do to regain a sense of control. On the other hand, when patients are engaging in excessive information-seeking or treatment-seeking behaviours (ie, part of confrontation), oncology providers should be aware that if it might be a signal of underlying anxiety and make sure patients have appropriate mental healthcare and support. Mental health providers may help to address coping, mood and quality of life through evidence-based interventions for advanced cancer patients. For instance, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy is indicated to reduce emotional distress and improve quality of life by facilitating the active acceptance of unpleasant thoughts and feelings in cancer patients,58 59 which may be a worthwhile approach. Finally, early palliative care is a comprehensive, multidisciplinary, evidence-based approach for improving quality of life, which may be integrated into standard oncology care for patients with advanced cancer.60

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the participants for their involvement, and all healthcare workers for their kind support in the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: YH, HJ, VWQL and JC designed the study. YH, HJ, MY, JZ and GL collected data. YH and JC analysed the data and drafted the manuscript. YH, HJ, MY, JZ, GL, VWQL and JC revised the manuscript.

Funding: The study is supported by Shanghai Municipal Health Bureau Foundation (No. 201740116), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 71874111), School of Medicine of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Core Education Project (No. ZD150603), The Fourth Round of Three-year Action Plan on Public Health Discipline and Talent Program: Evidence-based Public Health and Health Economics (No.15GWZK0901).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Shanghai Chest Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (No. KS1353).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:115–32. 10.3322/caac.21338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stewart B, Wild CP. World cancer report 2014. Health 2017.

- 3. Ma Y, Yang Y, Huang Y, et al. An investigation of symptom burden and quality of life in Chinese chemo-naïve advanced lung cancer patients by using the Instrument-Cloud QOL System. Lung Cancer 2014;84:301–6. 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schmidt K, Damm K, Prenzler A, et al. Preferences of lung cancer patients for treatment and decision-making: a systematic literature review. Eur J Cancer Care 2016;25:580–91. 10.1111/ecc.12425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang H-Y, Shi J-F, Guo L-W, et al. Expenditure and financial burden for common cancers in China: a hospital-based multicentre cross-sectional study. The Lancet 2016;388:S10 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31937-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chouaid C, Agulnik J, Goker E, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life and Utility in Patients with Advanced Non–Small-Cell Lung Cancer: A Prospective Cross-Sectional Patient Survey in a Real-World Setting. Journal of Thoracic Oncology 2013;8:997–1003. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318299243b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Zeng H, Zheng R, Guo Y, et al. Cancer survival in China, 2003-2005: a population-based study. Int J Cancer 2015;136:1921–30. 10.1002/ijc.29227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gupta D, Braun DP, Staren ED. Association between changes in quality of life scores and survival in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care 2012;21:614–22. 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2012.01332.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maione P, Perrone F, Gallo C, et al. Pretreatment quality of life and functional status assessment significantly predict survival of elderly patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer receiving chemotherapy: a prognostic analysis of the multicenter Italian lung cancer in the elderly study. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:6865–72. 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.527 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Polanski J, Jankowska-Polanska B, Rosinczuk J, et al. Quality of life of patients with lung cancer. Onco Targets Ther 2016;9:1023–8. 10.2147/OTT.S100685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chen JE, Lou VW, Jian H, et al. Objective and subjective financial burden and its associations with health-related quality of life among lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:1265–72. 10.1007/s00520-017-3949-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Mosher CE, Ott MA, Hanna N, et al. Coping with physical and psychological symptoms: a qualitative study of advanced lung cancer patients and their family caregivers. Support Care Cancer 2015;23:2053–60. 10.1007/s00520-014-2566-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nipp RD, Greer JA, El-Jawahri A, et al. Coping and Prognostic Awareness in Patients With Advanced Cancer. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2551–7. 10.1200/JCO.2016.71.3404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nipp RD, El-Jawahri A, Fishbein JN, et al. The relationship between coping strategies, quality of life, and mood in patients with incurable cancer. Cancer 2016;122:2110–6. 10.1002/cncr.30025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feifel H, Strack S, Nagy VT. Coping strategies and associated features of medically ill patients. Psychosom Med 1987;49:616–25. 10.1097/00006842-198711000-00007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ma YM, Ba CF, Wang YB. Analysis of factors affecting the life quality of the patients with late stomach cancer. J Clin Nurs 2014;23:1257–62. 10.1111/jocn.12311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu XD, Qin HY, Zhang JE, et al. The prevalence and correlates of symptom distress and quality of life in Chinese oesophageal cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy after radical oesophagectomy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2015;19:502–8. 10.1016/j.ejon.2015.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hong JF, Wei ZZ, Wang WL, et al. coping and quality of life in Chinese patients with newly diagnosed gastric cancer. Journal of Clinical Nursing 2015;24:2439–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Laarhoven HW, Schilderman J, Bleijenberg G, et al. Coping, quality of life, depression, and hopelessness in cancer patients in a curative and palliative, end-of-life care setting. Cancer Nurs 2011;34:302–14. 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181f9a040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sorato DB, Osório FL, Coping OFL. Coping, psychopathology, and quality of life in cancer patients under palliative care. Palliat Support Care 2015;13:517–25. 10.1017/S1478951514000339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu L, Pan Q, Lin R. Prevalence rate and influencing factors of preoperative anxiety and depression in gastric cancer patients in China: Preliminary study. J Int Med Res 2016;44:377–88. 10.1177/0300060515616722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. He G, Liu S. Quality of life and coping styles in Chinese nasopharyngeal cancer patients after hospitalization. Cancer Nurs 2005;28:179–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Nakamura YM, Orth U. Acceptance as a Coping Reaction: Adaptive or not? Swiss Journal of Psychology 2005;64:281–92. 10.1024/1421-0185.64.4.281 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Feifel H, Strack S, Nagy VT. Degree of life-threat and differential use of coping modes. J Psychosom Res 1987;31:91–9. 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90103-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther 2006;44:1–25. 10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hack TF, Degner LF. Coping responses following breast cancer diagnosis predict psychological adjustment three years later. Psychooncology 2004;13:235–47. 10.1002/pon.739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yeung NC, Lu Q. Affect mediates the association between mental adjustment styles and quality of life among Chinese cancer survivors. J Health Psychol 2014;19:1420–9. 10.1177/1359105313493647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Goss PE, Strasser-Weippl K, Lee-Bychkovsky BL, et al. Challenges to effective cancer control in China, India, and Russia. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:489–538. 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70029-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen H, Komaromy C, Valentine C. From hope to hope: the experience of older Chinese people with advanced cancer. Health 2015;19:154–71. 10.1177/1363459314555238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bai Q, Zhang Z, Lu X, Xq L, et al. Attitudes towards palliative care among patients and health professionals in Henan, China. Prog Palliat Care 2010;18:341–5. 10.1179/1743291X10Y.0000000006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Park CL, Iacocca MO. A stress and coping perspective on health behaviors: theoretical and methodological considerations. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping. 2014;27:123–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Drach-Zahavy A, Somech A. Coping with health problems: the distinctive relationships of Hope sub-scales with constructive thinking and resource allocation. Pers Individ Dif 2002;33:103–17. 10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00138-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Billings DW, Folkman S, Acree M, et al. Coping and physical health during caregiving: the roles of positive and negative affect. J Pers Soc Psychol 2000;79:131–42. 10.1037/0022-3514.79.1.131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Katter JK, Greenglass E. The influence of mood on the relation between proactive coping and rehabilitation outcomes. Can J Aging 2013;32:13–20. 10.1017/S071498081200044X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rueda B, Pérez-García AM, strategies C. Coping strategies, depressive symptoms and quality of life in hypertensive patients: mediational and prospective relations. Psychol Health 2013;28:1152–70. 10.1080/08870446.2013.795223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Folkman S, Greer S. Promoting psychological well-being in the face of serious illness: when theory, research and practice inform each other. Psychooncology 2000;9:11–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Roberts D, Calman L, Large P, et al. A revised model for coping with advanced cancer. Mapping concepts from a longitudinal qualitative study of patients and carers coping with advanced cancer onto Folkman and Greer’s theoretical model of appraisal and coping. Psychooncology 2018;27:229–35. 10.1002/pon.4497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Hirsch JK, Floyd AR, Duberstein PR. Perceived health in lung cancer patients: the role of positive and negative affect. Qual Life Res 2012;21:187–94. 10.1007/s11136-011-9933-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Weitzner MA, Meyers CA, Stuebing KK, et al. Relationship between quality of life and mood in long-term survivors of breast cancer treated with mastectomy. Support Care Cancer 1997;5:241–8. 10.1007/s005200050067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stellar JE, John-Henderson N, Anderson CL, et al. Positive affect and markers of inflammation: discrete positive emotions predict lower levels of inflammatory cytokines. Emotion 2015;15:129–33. 10.1037/emo0000033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Messay B, Lim A, Marsland AL. Current understanding of the bi-directional relationship of major depression with inflammation. Biol Mood Anxiety Disord 2012;2:4 10.1186/2045-5380-2-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fredrickson BL. The broaden–and–build theory of positive emotions. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2004;359:1367–77. 10.1098/rstb.2004.1512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Garland EL, Fredrickson B, Kring AM, et al. Upward spirals of positive emotions counter downward spirals of negativity: insights from the broaden-and-build theory and affective neuroscience on the treatment of emotion dysfunctions and deficits in psychopathology. Clin Psychol Rev 2010;30:849–64. 10.1016/j.cpr.2010.03.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Raijmakers NJH, Zijlstra M, van Roij J, et al. Health-related quality of life among cancer patients in their last year of life: results from the PROFILES registry. Support Care Cancer 2018;26:3397–404. 10.1007/s00520-018-4181-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Luo N, Li M, Liu GG, et al. Developing the Chinese version of the new 5-level EQ-5D descriptive system: the response scaling approach. Qual Life Res 2013;22:885–90. 10.1007/s11136-012-0200-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Feng Y, Devlin N, Shah K, et al. ; New methods for modelling EQ-5D-5L value sets: an application to English data, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Deng M, Lan Y, Luo S. Quality of life estimate in stomach, colon, and rectal cancer patients in a hospital in China. Tumour Biol 2013;34:2809–15. 10.1007/s13277-013-0839-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063–70. 10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods 2008;40:879–91. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Schoemann AM, Boulton AJ, Short SD. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 2017;8:379–86. 10.1177/1948550617715068 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shen Y, Wu B, Wang X, et al. Health state utilities in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer in China. J Comp Eff Res 2018;7:443–52. 10.2217/cer-2017-0069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Perrone F, Jommi C, Di Maio M, et al. The association of financial difficulties with clinical outcomes in cancer patients: secondary analysis of 16 academic prospective clinical trials conducted in Italy. Ann Oncol 2016;27:2224–9. 10.1093/annonc/mdw433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Qureshi F, Appleton AA, et al. A healthy mix of emotions: underlying biological pathways linking emotions to physical health. Curr Opin Behav Sci 2017;15:16–21. 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.05.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Walker MS, Larsen RJ, Zona DM, et al. Smoking urges and relapse among lung cancer patients: findings from a preliminary retrospective study. Prev Med 2004;39:449–57. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Russell JA. A circumplex model of affect. J Pers Soc Psychol 1980;39:1161–78. 10.1037/h0077714 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chouaid C, Agulnik J, Goker E, et al. Health-related quality of life and utility in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: a prospective cross-sectional patient survey in a real-world setting. J Thorac Oncol 2013;8:997–1003. 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318299243b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. van Roij J, Fransen H, van de Poll-Franse L, et al. Measuring health-related quality of life in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review of self-administered measurement instruments. Qual Life Res 2018;27:1937–55. 10.1007/s11136-018-1809-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Rost AD, Wilson K, Buchanan E, et al. Improving Psychological Adjustment Among Late-Stage Ovarian Cancer Patients: Examining the Role of Avoidance in Treatment. Cogn Behav Pract 2012;19:508–17. 10.1016/j.cbpra.2012.01.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Feros DL, Lane L, Ciarrochi J, et al. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) for improving the lives of cancer patients: a preliminary study. Psychooncology 2013;22:459–64. 10.1002/pon.2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Greer JA, Jacobs JM, El-Jawahri A, et al. Role of Patient Coping Strategies in Understanding the Effects of Early Palliative Care on Quality of Life and Mood. J Clin Oncol 2018;36:53–60. 10.1200/JCO.2017.73.7221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023672supp001.pdf (111.5KB, pdf)