Abstract

Objective

The treatment outcome of direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) in chronic hepatitis C patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is controversial. The current study aimed to address the treatment efficacy and safety of DAAs in patients with curative or active HCC, compared with those of patients without HCC.

Design

A prospective cohort study

Setting

A medical centre and two regional hospitals in Taiwan

Participants

A total of 713 Taiwanese patients (601 non-HCC, 74 curative HCC and 38 active HCC patients) who received standard-of-care DAAs were consecutively enrolled in the study.

Main outcome measurement

The primary objective was to determine treatment efficacy, defined as undetectable hepatitis C virus RNA throughout 12 weeks of the post-treatment follow-up period (sustained virological response 12 [SVR12]).

Results

The overall SVR12 rate was 96.9%. The SVR12 rate was similar between the patients with HCC and those without HCC (95.5% vs 97.2%, p=0.37). The HCC patients were divided into two groups, those with curative HCC and those with viable HCC; a substantially but not significantly lower SVR rate, 92.1% (35/38), was observed in the patients with viable HCC compared with the SVR rate, 97.3% (72/74), in those with curative HCC (p=0.33). Compared with the patients with curative HCC, the patients with viable HCC had a significantly higher proportion of serious adverse events (10.5% vs 1.0%, p=0.002), early treatment discontinuation (10.5% vs 2.8%, p=0.03) and mortality (5.3% vs 0.1%, p=0.008).

Conclusions

An equivalently high SVR rate was observed in patients with either past or active HCC compared with those without HCC. The safety concerns in the HCC patients did not compromise treatment efficacy.

Keywords: DAA, HCV, HCC, SVR

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Includes a representative chronic hepatitis C patient cohort in regard to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) status considered prior to allocating to direct-acting antiviral treatment group.

Discusses the safety profile, which has rarely been explored by other studies beyond the issue of treatment efficacy.

Included relatively fewer patients with severe liver disease, for whom evidence of HCC with liver decompensation is limited.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality.1 2 Approximately, 71 million individuals are chronically infected with hepatitis C virus (HCV) worldwide,3 accounting for one-third of the HCC patient population worldwide.1 HCV eradication by antiviral therapy greatly reduces the risk for HCC.4–6

From another perspective, it is unknown if the presence of HCC affects antiviral treatment efficacy in chronic hepatitis C (CHC). Given the only modest treatment efficacy and the unfavourable safety profiles for cancer patients, the issue of the possible effect of HCC on antiviral treatment efficacy has rarely been touched on in the interferon era.7 All oral direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) have replaced interferon-based therapy as the standard treatment of CHC. The novel therapy gives hopes to CHC patients who possess more progressive liver diseases including HCC. Some studies have disclosed potentially suboptimal antiviral treatment efficacy in HCC patients receiving DAA.8–11 It is postulated that impairment of the bioavailability of DAAs may account for the inferior treatment response.12 However, this has not always been the case across studies.13–15 The divergent results may be attributed to different patient profiles and regimens10 11 or unclear cancer status at the time of launching DAA treatment.9 14 Furthermore, the topic has been less discussed in reference to Asian ethnicities. In this study, we aimed to explore the issue by recruiting a well-characterised Taiwanese patient cohort. The HCC status of either curative or active was well-clarified before the administration of antivirals, and the treatment efficacy and safety were judged among patient groups.

Methods

CHC patients with prior history of HCC who received all oral DAAs were consecutively enrolled at a medical centre and two regional hospitals from January 2015 to December 2017. Another set of CHC patients without HCC who underwent DAAs treatment during the same period were enrolled as controls. The National Health Insurance Administration (NHIA) of Taiwan began to reimburse certain DAAs in January 2017. The treatment regimens and strategies conformed to the regional guidelines16 and to the regulation of the Health and Welfare Department of Taiwan.17 HCC was confirmed by histological or clinical diagnosis based on the guidelines of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases18 and the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver.19 Patients with curative HCC were defined as those with HCC who were subjected to surgical resection, local alcohol injection, radiofrequency ablation or liver transplantation and who were without imaging evidence of recurrence within 6 months prior to initiating DAA treatment.

The primary objective of the study was to determine the treatment efficacy, which was defined as undetectable HCV RNA throughout 12 weeks of the post-treatment follow-up period (sustained virological response 12 [SVR12]). HCV RNA and genotypes were measured using real-time PCR assay (RealTime HCV; Abbott Molecular, Des Plaines, IL, USA; detection limit: 12 IU/mL).20 It is mandatory for all of the treating physicians to input SVR12 data into the national registry system, which is requested by the NHIA of Taiwan. Patients who terminated therapy early and failed to provide complete SVR12 data were regarded as being non-SVR. Liver cirrhosis was defined by histology,21 fibroscan (>12 kPa), acoustic radiation force impulse (>1.8 m/s) or clinical judgement by the treating physicians.

Patient and public involvement

No patient or member of the public was involved in setting the research question and outcome measures or planning the design of the study.

Statistical analyses

Frequency was compared between groups using the χ2 test with the Yates correction or Fisher’s exact test. Group means (presented as the mean SD) were compared using analysis of variance and Student’s t-test or the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test when appropriate. Stepwise logistic regression analysis was performed to determine factors associated with SVR12 by analysing the covariates with a p value <0.1 in the univariate analysis. The statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS V.12.0 statistical package. All statistical analyses were based on two-sided hypothesis tests with a significance level of p<0.05.

Results

Patients

A total of 713 patients were enrolled in the current study. The basic demographical, virological and clinical features and treatment regimens of the patients were presented in table 1. The mean age of the patients was 62.2 years. Males accounted for 40.8% of the population. The mean HCV RNA level was 5.78 log IU/mL. HCV genotype-1 accounted for 86.7% of the population. Three hundred and sixty-eight patients (51.6%) had liver cirrhosis, and 284 (39.8%) failed to respond to a previous interferon-based regimen. One hundred and twelve patients (15.7%) had a history of HCC before treatment. Compared with patients without HCC, those with HCC were older and had higher pretreatment aspartate aminotransferase and bilirubin levels, a lower albumin level and platelet counts, a higher proportion of liver cirrhosis, prior liver transplantation and interferon-experienced history. Of the 112 patients with HCC, 74 had curative HCC, whereas the remaining 38 had viable HCC at the time of treatment. Compared with the patients with curative HCC, those with viable HCC had lower albumin levels and HCV RNA levels (table 2). Treatment regimens did not differ between patients with HCC and those without HCC.

Table 1.

Basic characteristics and treatment regimens of the patients with or without hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

| All patients (n=713) |

Non-HCC (n=601) |

HCC (n=112) |

P value | |

| Male, n (%) | 291 (40.8) | 240 (39.9) | 51 (45.5) | 0.27 |

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 62.2±11.3 | 61.2±11.4 | 67.6±9.0 | <0.001 |

| Body weight, kg (mean±SD) | 64.0±12.5 | 64.3±12.8 | 62.4±10.6 | 0.15 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 163 (22.9) | 137 (22.8) | 26 (23.2) | 0.92 |

| Platelet count, ×1000/10/L (mean±SD) | 161±70 | 166±70 | 133±73 | <0.001 |

| AST, IU/L (mean±SD) | 73.9±48.7 | 71.6±46.3 | 86.7±58.5 | 0.003 |

| ALT, IU/L (mean±SD) | 83.2±60.2 | 83.5±61.0 | 81.9±56.2 | 0.79 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL (mean±SD) | 4.2±0.4 | 4.3±0.4 | 4.0±0.5 | <0.001 |

| Serum bilirubin, mg/dL (mean±SD) | 0.97+0.51 | 0.94±0.50 | 1.14+0.56 | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (mean±SD) | 1.00±1.14 | 0.97±1.11 | 1.12±1.31 | 0.27 |

| HCV RNA, log IU/mL | 5.78±0.92 | 5.81±0.92 | 5.62±0.92 | 0.05 |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | ||||

| 1 | 618 (86.7) | 520 (86.5) | 98 (87.5) | 0.78 |

| 2 | 95 (13.3) | 81 (13.5) | 14 (12.5) | |

| Liver cirrhosis, n (%) | 368 (51.6) | 276 (45.9) | 92 (82.1) | <0.001 |

| Child-Pugh A/B, n (%) | 339 (47.5)/29 (4.1) | 256 (42.6)/20 (3.3) | 83 (74.1)/9 (8.0) | 0.43 |

| Prior treatment experienced*, n (%) | 284 (39.8) | 227 (37.8) | 57 (50.9) | 0.009 |

| Post liver transplantation, n (%) | 13 (1.8) | 7 (1.2) | 6 (5.4) | 0.009 |

| Regimen, n (%) | 0.74 | |||

| PrOD±RBV | 463 (64.9) | 393 (65.4) | 70 (62.5) | |

| DCV/ASV | 91 (12.8) | 76 (12.6) | 15 (13.4) | |

| SOF/RBV | 41 (5.8) | 37 (6.2) | 4 (3.6) | |

| SOF/LDV±RBV | 58 (8.1) | 47 (7.8) | 11 (9.8) | |

| SOF/DCV±RBV | 47 (6.6) | 37 (6.2) | 10 (8.9) | |

| EBR/GZR | 10 (1.4) | 8 (1.3) | 2 (1.8) | |

| SOF/VEL | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) |

*All interferon-based therapy.

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ASV, asunaprevir; DCV, daclatasvir; EBR, elbasvir; GZR, grazoprevir; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LDV, ledipasvir; PrOD, paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir; RBV, ribavirin; SOF, sofosbuvir; VEL, velpatasvir.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the HCC patients with or without residual tumour

| Curative HCC (n=74) |

Active HCC (n=38) |

P value | |

| Male, n (%) | 32 (43.2) | 19 (50.0) | 0.50 |

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 66.6±8.8 | 69.6±9.2 | 0.1 |

| Body weight, kg (mean±SD) | 63.1±9.7 | 61.1±12.1 | 0.39 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 16 (21.6) | 10 (26.3) | 0.58 |

| Platelet count, ×1000/mm3 (mean±SD) | 140±65 | 117±57 | 0.06 |

| AST, IU/L (mean±SD) | 90.3±64.9 | 79.6±43.2 | 0.31 |

| ALT, IU/L (mean±SD) | 86.8±62.2 | 72.1±40.7 | 0.14 |

| Serum albumin, g/dL (mean±SD) | 4.1±0.4 | 3.8±0.5 | 0.002 |

| Serum bilirubin, mg/dL (mean±SD) | 1.13±0.57 | 1.16+0.55 | 0.78 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (mean±SD) | 1.01±0.98 | 1.34±1.80 | 0.22 |

| HCV RNA, log IU/mL | 5.79±0.86 | 5.30±0.96 | 0.01 |

| HCV genotype, n (%) | |||

| 1 | 66 (89.2) | 32 (84.2) | 0.55 |

| 2 | 8 (10.8) | 6 (15.8) | |

| Liver cirrhosis, n (%) | 60 (81.1) | 32 (84.2) | 0.68 |

| Child-Pugh A/B, n (%) | 56 (93.3)/4 (6.7) | 27 (84.4)/5 (15.6) | 0.43 |

| Prior treatment experienced, n (%) | 42 (56.8) | 15 (39.5) | 0.08 |

| Post liver transplantation, n (%) | 6 (8.1) | 0 (0) | 0.09 |

| Regimen, n (%) | 0.78 | ||

| PrOD±RBV | 48 (64.9) | 22 (57.9) | |

| DCV/ASV | 10 (13.5) | 5 (13.2) | |

| SOF/RBV | 2 (2.7) | 2 (5.3) | |

| SOF/LDV±RBV | 6 (8.1) | 5 (13.2) | |

| SOF/DCV±RBV | 6 (8.1) | 4 (10.5) | |

| EBR/GZR | 2 (2.7) | 0 (0) |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ASV, asunaprevir; DCV, daclatasvir; EBR, elbasvir; GZR, grazoprevir; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LDV, ledipasvir; PrOD, paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir; RBV, ribavirin; SOF, sofosbuvir.

Treatment responses

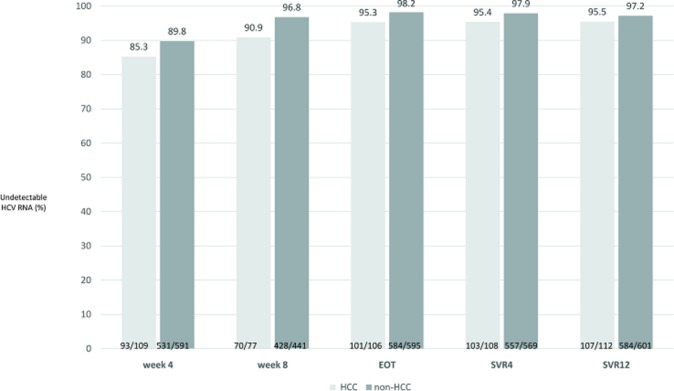

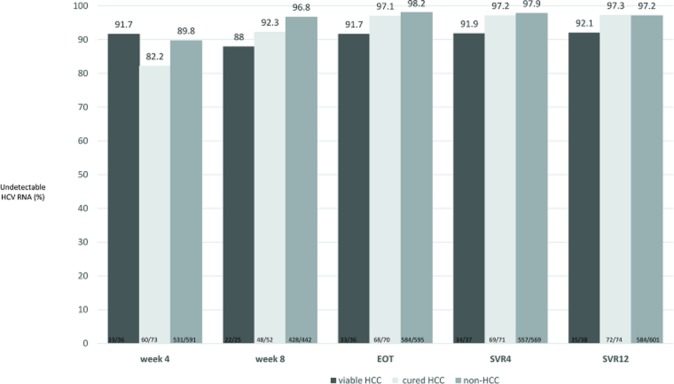

The rates of undetectable HCV RNA at treatment week 4, treatment week 8, end-of-treatment and 4 weeks after end-of-treatment (SVR4) were 89.1%, 96.0%, 97.7% and 97.5%, respectively. The overall SVR12 rate was 96.9%, and the overall relapse rate was 1.3%. As shown in figure 1, the on-treatment responses did not differ between the patients with a history of HCC and those without a history of HCC. Additionally, the SVR12 rates in the two groups were similar (95.5% vs 97.2%, p=0.37). While the HCC patients were divided into two groups, those with curative HCC and those with viable HCC, a substantially lower SVR12 rate, 92.1% (35/38), was observed in the patients with viable HCC than in those with curative HCC, 97.3% (72/74). However, this difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.33) (figure 2). Subgroup analysis revealed that patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis (82.8% vs 97.5%, p=0.001) and HCV genotype-2 infection (92.6% vs 97.6%, p=0.02) had a lower SVR12 rate (table 3). Logistic regression revealed that decompensated liver cirrhosis was the only factor independently associated with treatment failure (OR/95% CIs 8.67/2.93 to 25.63, p<0.001). The SVR rate did not differ between patients with viable HCC with those with curative HCC/without HCC (92.1% vs 97.2%, p=0.11). The characteristics of the patients with treatment failure were listed in table 4.

Figure 1.

On-treatment responses and final treatment outcome in patients with or without a history of HCC. The grey bar represents patients with HCC. The brown bar represents patients without HCC. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; EOT, end-of-treatment; LC, liver cirrhosis; C-P A, Child-Pugh A; C-P B, Child-Pugh B.

Figure 2.

On-treatment responses and final treatment outcome in patients with or without HCC. The dark brown bar represents patients with viable HCC. The grey bar represents patients with curative HCC. The brown bar represents patients without HCC. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

Table 3.

Subgroup analysis of the SVR rate

| Variable | % (95% CI) | P value |

| Age (years) | ||

| <65 | 98.0 (96.6 to 99.4) | 0.06 |

| >65 | 95.6 (93.3 to 97.9) | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 97.6 (95.8 to 99.4) | 0.38 |

| Female | 96.4 (95.8 to 99.4) | |

| HCV viral loads | ||

| <800 000 IU/mL | 97.8 (96.3 to 99.3) | 0.18 |

| >800 000 IU/mL | 96.0 (94.0 to 98.0) | |

| HCV genotype | ||

| HCV-1 | 97.6 (96.4 to 98.8) | 0.02 |

| HCV-non-1 | 92.6 (87.3 to 97.9) | |

| LC | ||

| No | 97.7 (96.1 to 99.3) | 0.25 |

| Yes | 96.2 (94.2 to 98.2) | |

| Decompensation | ||

| No | 97.5 (96.3 to 98.7) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 82.8 (69.1 to 96.5) | |

| Treatment history | ||

| Naive | 96.5 (94.8 to 98.2) | 0.44 |

| Experienced | 97.5 (95.7 to 99.3) | |

| HCC | ||

| No or cured | 97.2 (96.0 to 98.4) | 0.11 |

| Viable | 92.1 (83.5 to 100) | |

| Regimen | ||

| PrOD+RBV | 98.3 (97.1 to 99.5) | 0.06 |

| DCV/ASV | 95.6 (91.4 to 99.8) | |

| SOF+RBV | 90.2 (81.1 to 99.3) | |

| SOF/LDV+RBV | 94.8 (89.1 to 100) | |

| SOF+DCV | 95.7 (89.9 to 100) | |

| EBR/GZR | 90.0 (71.4 to 100) | |

| SOF/VEL | 100 (100 to 100) |

ASV, asunaprevir; DCV, daclatasvir; EBR, elbasvir; GZR, grazoprevir; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; LDV, ledipasvir; PrOD, paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir; RBV, ribavirin; SOF, sofosbuvir; SVR, sustained virological response; VEL, velpatasvir.

Table 4.

Characteristics of the patients with treatment failure

| Case number | Age (years) | Sex | HCV genotype | HCV viral loads (log IU/mL) | Treatment history | Regimen | Cirrhosis | Early discontinuation |

| Viable HCC | ||||||||

| IF-473 | 76 | F | 1b | 5.88 | IFN-exp. | PrOD | LC, C-P A | Yes |

| IF-566 | 73 | M | 1b | 5.44 | Naive | ProD | LC, C-P A | Yes |

| IF-900 | 65 | M | 1b | 4.33 | Naive | SOF/LDV+RBV | LC, C-P B | Yes |

| Curative HCC | ||||||||

| IF-386 | 81 | M | 1b | 6.24 | Naive | PrOD | LC, C-P A | Yes |

| IF-814 | 60 | F | 1b | 5.70 | Naive | SOF/LDV+RBV | LC, C-P B | Yes |

| Non-HCC | ||||||||

| IF-024 | 65 | F | 1b | 6.91 | IFN-exp. | DCV/ASV | LC, C-P A | No |

| IF-042 | 75 | F | 1b | 6.20 | Naive | DCV/ASV | Non-LC | No |

| IF-084 | 57 | M | 2 | 4.68 | IFN-exp. | SOF+RBV | LC, C-P B | No |

| IF-219 | 68 | F | 2 | 4.63 | Naive | SOF/DCV+RBV | LC, C-P A | No |

| IF-221 | 66 | F | 2 | 4.29 | Naive | SOF/DCV+RBV | LC, C-P B | Yes |

| IF-276 | 66 | F | 1b | 3.56 | IFN-exp. | PrOD | LC, C-P A | Yes |

| IF-501 | 73 | F | 1b | 4.42 | IFN-exp. | PrOD | Non-LC | Yes |

| IF-530 | 58 | F | 1b | 6.25 | Naive | DCV/ASV | Non-LC | No |

| IF-585 | 48 | M | 1b | 6.79 | Naive | EBR/GZR | Non-LC | Yes |

| IF-595 | 75 | F | 1a | 6.12 | Naive | PrOD+RBV | LC, C-P A | Yes |

| IF-765 | 71 | F | 1b | 5.90 | Naive | PrOD | Non-LC | No |

| IF-784 | 76 | F | 1b | 5.83 | IFN-exp. | DCV/ASV | Non-LC | No |

| IF-863 | 44 | M | 2 | 4.77 | Naive | SOF+RBV | LC, C-P A | Yes |

| IF-951 | 54 | F | 1b | 6.55 | IFN-exp. | SOF/LDV | Non-LC | No |

| IF-1116 | 61 | M | 2 | 5.81 | Naive | SOF+RBV | LC, C-P A | No |

| IF-1147 | 81 | F | 2 | 6.88 | Naive | SOF+RBV | LC, C-P B | Yes |

| IF-1471 | 51 | F | 2 | 5.81 | Naive | SOF+RBV | Non-LC | Yes |

ASV, asunaprevir; DCV, daclatasvir; EBR, elbasvir; F, female; GZR, grazoprevir; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; IFN exp., interferon experienced; LDV, ledipasvir; M, male; PrOD, paritaprevir/ritonavir/ombitasvir/dasabuvir; RBV, ribavirin; SOF, sofosbuvir.

Safety profile in patients with or without viable HCC

A total of 243 (34.1%) of the patients experienced at least one adverse event (AE), the incidence of which did not differ between the patients with viable HCC and those without viable HCC (p=0.99). Eleven (1.5%) patients experienced serious AEs (SAEs). Twenty-three (3.2%) patients discontinued treatment or follow-up, whereas three (0.4%) patients died (two HCC patients, one with septic shock and one with liver failure; one non-HCC patient with variceal bleeding) before the end of follow-up. None of the mortalities was treatment regimen-related. Patients with viable HCC had a significantly higher incidence of SAEs (10.5% vs 1.0%, p=0.002), early treatment discontinuation (10.5% vs 2.8%, p=0.03) and mortality (5.3% vs 0.1%, p=0.008) than those without viable HCC (table 5). Of the four patients with viable HCC who terminated therapy early, two terminated therapy due to mortality, one due to herpes zoster and weakness, and one due to severe vomiting and headache. The rate of SAEs did not differ between the patients with ribavirin (RBV) and those without RBV (2.4% vs 1.3%, p=0.29). In contrast, patients with RBV use had a higher rate of early discontinuation than those without its use (6.6% vs 2.2%, p=0.005). However, patients with viable HCC did not have a higher rate of RBV use than those without non-viable HCC (18.4% vs 23.6%, p=0.47), indicating that RBV may not be the main reason for the higher rate of early discontinuation in the population. For the DAA regimens, the rate of SAEs (1.2% vs 2.7%, p=0.25) and the rate of early treatment termination (2.7% vs 5.4%, p=0.12) did not differ between the patients using protease inhibitors (asunaprevir, paritaprevir or grazoprevir) and those not. The SAEs are presented in online supplementary table 1.

Table 5.

Safety profile of the patients with or without viable HCC

| HCC (+) (n=38) |

HCC (−) (n=675) |

P value | |

| Drug discontinuation, n (%) | 4 (10.5) | 19 (2.8) | 0.03 |

| Mortality, n (%) | 2 (5.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0.008 |

| Serious adverse event, n (%) | 4 (10.5) | 7 (1.0) | 0.002 |

| Adverse event, n (%) | 13 (34.2) | 230 (34.1) | 0.99 |

| Fatigue, n (%) | 7 (18.4) | 80 (11.9) | 0.21 |

| Nausea/vomiting, n (%) | 0 (0) | 12 (1.8) | 1 |

| Headache, n (%) | 1 (2.6) | 47 (7.0) | 0.51 |

| Pruritus, n (%) | 5 (13.2) | 106 (15.7) | 0.82 |

| Rash, n (%) | 2 (5.3) | 39 (5.8) | 1 |

| Insomnia, n (%) | 5 (13.2) | 100 (14.8) | 1 |

| Dyspnoea, n (%) | 4 (10.5) | 23 (3.4) | 0.05 |

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

bmjopen-2018-026703supp001.pdf (20.4KB, pdf)

Discussion

In the current study, we demonstrated that all oral DAAs were highly effective and safe in Taiwanese CHC patients. Compared with non-HCC patients, HCC patients were characterised by having more advanced liver disease and more safety concerns during antiviral treatment. However, these disadvantages did not compromise the treatment efficacy of the DAAs in these patients. An equivalently high SVR rate was observed in patients with either past or current HCC as that observed in the non-HCC patients.

Due to the difficult and prolonged treatment course and uncertain long-term benefit of interferon-based treatment, cancer patients enrolled in therapy during the interferon era exclusively represented the curative HCC status in early studies.7 Because HCC patients were always excluded in clinical trials, the limited data on the clinical development of DAA was produced from a phase 2 study that included 61 HCC patients on the waiting list for liver transplantation. It turned out that only half of the patients who received sofosbuvir/RBV achieved SVR12 after liver transplantation.22 Later, more data emerged with the wide application of DAAs in the real world. Some preliminary reports have suggested a suboptimal treatment efficacy among HCC patients.10 11 Recently, 421 cirrhotic patients including one-third active or curative HCC were analysed by Prenner et al. The treatment response in patients with curative HCC was similar to that of patients without HCC history. However, active HCC patients had an eight-fold increased risk of failing HCV therapy compared with those without HCC.8 A large real-world data from the Veterans Affairs healthcare system in the USA has also demonstrated a higher SVR12 rate in non-HCC patients than those with HCC.9

The potential mechanism for the suboptimal antiviral effect on HCC remains elusive. Ineffective blood delivery to the target site12 and incapability of drug binding has been postulated.23 24 Poor cancer immunity has also been linked to the impaired viral clearance during DAA treatment.25 However, we did not observe an inferior treatment response in cancer patients in the current study, which aligns with the observations of some other studies.13 15 The SVR rate of 97% was similar between patients without HCC and those with curative HCC, although the SVR rate was substantially lower in active HCC patients. The interpretation of the discordant results should be reviewed in greater detail. The poor treatment response of the study population may be attributed to a variety of regimens, some of which were suboptimal.10 11 Imperatively, the disease severities, being the major determinant of SVR, of HCC patients were not equally distributed across studies. Half of the treated patients in the current cohort had liver cirrhosis. However, only a minority had a decompensated status, which may also account for the optimistic result of this study. Meanwhile, patients with HCC, either curative or active, at the time of DAA treatment were not clearly defined in some reports.9 14 Taken collectively, further studies using the most potent regimens26 to treat patients with comparable disease severities and well-defined HCC status may help to answer the question.

The safety issues in treating a catastrophic population have been rarely mentioned previously. In the current study, we demonstrated that patients with viable HCC seemed to have more safety concerns. However, thanks to the high efficacy and short treatment course of DAAs, the adverse impact did not compromise treatment efficacy.

Our findings should be interpreted with consideration of the caveat in which the number of viable HCC patients was not large enough for a definite conclusion to be drawn. In conclusion, DAAs are highly effective and safe in treating Taiwanese CHC patients, regardless of HCC status. Further studies enrolling larger sample size and more advanced liver disease are warranted to validate the finding.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: Conception and design: M-LY. Acquisition of data: M-LY, C-IH, P-CL, Y-HL, M-YH, Y-JW, Z-YL, S-CC, J-FH, C-YD and W-LC. Data analysis and interpretation: C-FH and M-LY. Manuscript drafting and critical revision: C-FH and M-LY. All authors had full access to all study data and, read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by grants from the Kaohsiung Medical University (MOST107-2314-B-037-025-MY2) and the Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital (KMUH106-6M02, KMUH105-5R05 and KMUH103-3R05).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Institutional Review Board of Kaohsiung MedicalUniversity Hospital—KMUH-IRB-F(I)-20170053—approved the protocols, whichfollowed the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation forGood Clinical Practice.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: The authors declare that all data supporting the findings are available within the article and there are no additional unpublished data.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. Akinyemiju T, Abera S, Ahmed M, et al. Global Burden of Disease Liver Cancer Collaboration. The burden of primary liver cancer and underlying etiologies from 1990 to 2015 at the global, regional, and national level: results from the global burden of disease study 2015. JAMA Oncol 2017;3:1683–91. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.3055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. European Association for the Study of the Liver. Electronic address: easloffice@easloffice.eu European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2018;69:182–236. 10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Polaris Observatory HCV Collaborators. Global prevalence and genotype distribution of hepatitis C virus infection in 2015: a modelling study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;2:161–76. 10.1016/S2468-1253(16)30181-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yu ML, Huang CF, Yeh ML, et al. Time-degenerative factors and the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma after antiviral therapy among hepatitis c virus patients: a model for prioritization of treatment. Clin Cancer Res 2017;23:1690–7. 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-0921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Huang CF, Yeh ML, Tsai PC, et al. Baseline gamma-glutamyl transferase levels strongly correlate with hepatocellular carcinoma development in non-cirrhotic patients with successful hepatitis C virus eradication. J Hepatol 2014;61:67–74. 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.02.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ioannou GN, Green PK, Berry K. HCV eradication induced by direct-acting antiviral agents reduces the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.08.030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang JF, Yu ML, Huang CF, et al. The efficacy and safety of pegylated interferon plus ribavirin combination therapy in chronic hepatitis c patients with hepatocellular carcinoma post curative therapies - a multicenter prospective trial. J Hepatol 2011;54:219–26. 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Prenner SB, VanWagner LB, Flamm SL, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma decreases the chance of successful hepatitis C virus therapy with direct-acting antivirals. J Hepatol 2017;66:1173–81. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.01.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Beste LA, Green PK, Berry K, et al. Effectiveness of hepatitis C antiviral treatment in a USA cohort of veteran patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2017;67:32–9. 10.1016/j.jhep.2017.02.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Saberi B, Dadabhai AS, Durand CM, et al. Challenges in treatment of hepatitis C among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2017;66:661–3. 10.1002/hep.29126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Soria A, Fabbiani M, Lapadula G, et al. Unexpected viral relapses in hepatitis C virus-infected patients diagnosed with hepatocellular carcinoma during treatment with direct-acting antivirals. Hepatology 2017;66:992–4. 10.1002/hep.29181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Konjeti VR, John BV. Interaction between hepatocellular carcinoma and hepatitis c eradication with direct-acting antiviral therapy. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol 2018;16:203–14. 10.1007/s11938-018-0178-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chang CY, Nguyen P, Le A, et al. Real-world experience with interferon-free, direct acting antiviral therapies in Asian Americans with chronic hepatitis C and advanced liver disease. Medicine 2017;96:e6128 10.1097/MD.0000000000006128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ji F, Wei B, Yeo YH, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: effectiveness and tolerability of interferon-free direct-acting antiviral regimens for chronic hepatitis C genotype 1 in routine clinical practice in Asia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2018;47:550–62. 10.1111/apt.14507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wei B, Ji F, Yeo YH, et al. Real-world effectiveness of sofosbuvir plus ribavirin for chronic hepatitis C genotype 2 in Asia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open Gastroenterol 2018;5:e000207 10.1136/bmjgast-2018-000207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Omata M, Kanda T, Wei L, et al. APASL consensus statements and recommendation on treatment of hepatitis C. Hepatol Int 2016;10:702–26. 10.1007/s12072-016-9717-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hepatitis C. Hepatitis C full oral new drug area. https://www.nhi.gov.tw/Content_List.aspx?n=A4EFF6CD1C4891CA&topn=3FC7D09599D25979 (Accessed 08th Apr 2018).

- 18. Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2018;67:358–80. 10.1002/hep.29086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Omata M, Cheng AL, Kokudo N, et al. Asia-Pacific clinical practice guidelines on the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: a 2017 update. Hepatol Int 2017;11:317–70. 10.1007/s12072-017-9799-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vermehren J, Yu ML, Monto A, et al. Multi-center evaluation of the Abbott RealTime HCV assay for monitoring patients undergoing antiviral therapy for chronic hepatitis C. J Clin Virol 2011;52:133–7. 10.1016/j.jcv.2011.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Scheuer PJ. Classification of chronic viral hepatitis: a need for reassessment. J Hepatol 1991;13:372–4. 10.1016/0168-8278(91)90084-O [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Curry MP, Forns X, Chung RT, et al. Sofosbuvir and ribavirin prevent recurrence of HCV infection after liver transplantation: an open-label study. Gastroenterology 2015;148:100–7. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.09.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Furihata T, Matsumoto S, Fu Z, et al. Different interaction profiles of direct-acting anti-hepatitis C virus agents with human organic anion transporting polypeptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014;58:4555–64. 10.1128/AAC.02724-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wlcek K, Svoboda M, Riha J, et al. The analysis of organic anion transporting polypeptide (OATP) mRNA and protein patterns in primary and metastatic liver cancer. Cancer Biol Ther 2011;11:801–11. 10.4161/cbt.11.9.15176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sachdeva M, Chawla YK, Arora SK. Immunology of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Hepatol 2015;7:2080–90. 10.4254/wjh.v7.i17.2080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. EASL. Recommendations on treatment of hepatitis C. Journal of hepatology 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026703supp001.pdf (20.4KB, pdf)