Abstract

Objectives

Prevention of hearing impairment (HI) is important because recovery of hearing is typically difficult. Epidemiological studies have examined the risk factors for HI. However, the association between hypertension and HI remains unclear. We aimed to clarify the association between hypertension and HI.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

Japanese workers in an information and communication technologies company.

Participants

Of 24 823 employees of the same company, we recruited 13 475 participants who underwent hearing testing by audiometry in annual health check-ups and did not have missing data regarding body measurement, blood test results and drinking/smoking status (mean age: 49.4 years; males: 86.4%).

Primary outcomes

Hearing tests were performed at two frequencies (1 kHz, 4 kHz). We defined the inability of participants to respond to 30 dB at 1 kHz and/or 40 dB at 4 kHz as overall moderate HI. We also defined moderate HI at 1 or 4 kHz as an abnormal finding at 1 or 4 kHz. We defined hypertension as ≥140 mm Hg systolic blood pressure and/or ≥90 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure and/or taking medication for hypertension. We examined the association between hypertension and HI after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index, smoking/drinking status, diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidaemia and proteinuria.

Results

Moderate HI was identified in 980 participants (7.3%). Of these, 441 participants (3.3%) exhibited moderate HI at 1 kHz, and 787 participants (5.8%) exhibited moderate HI at 4 kHz. Subjects with hypertension showed a higher prevalence of any HI. The prevalence of overall moderate HI, moderate HI at 1 kHz and moderate HI at 4 kHz among subjects with hypertension was 8.7%, 4.3% and 6.8%, while those among subjects without hypertension was 6.9%, 3.0% and 5.6% (p<0.01, p<0.01 and p=0.01, respectively).

Conclusions

Hypertension was associated with moderate HI in Japanese workers.

Keywords: epidemiology, cross-sectional study, hypertension, hearing impairment

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study was based on annual health check-ups which were conducted according to Japanese law; therefore, study participants comprised both healthy and unhealthy individuals.

Our research was unable to use precise information on hearing tests compared with tests conducted in hospitals because this study is based on health check-ups that are mandated by law.

We were unable to adjust family history of hearing impairment because it was not included in ascertained family history of illness.

Introduction

Hearing impairment (HI) is a common condition among older people. The Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that HI is one of eight chronic diseases and injuries affecting more than 10% of the world’s population.1 According to the WHO fact sheet published in March 2018, almost one-third of people aged 65 years or older have HI.2

Prevention of HI is an important public health issue not only because HI makes communication difficult, but also because it is associated with death, depression and dementia.3–7 A recent review reported that HI in midlife (aged 45–65 years) is associated with the risk of dementia in future.8

Recovery from HI is typically difficult, and several epidemiological studies have been conducted in an attempt to identify the risk factors for HI. Many risk factors for HI have been identified, including ageing, exposure to loud noise and medication. Of these, many previous studies have examined the associations between cardiovascular risk factors and HI. A meta-analysis of 13 cross-sectional studies revealed that, compared with persons without a diabetic condition, a higher prevalence of HI was observed in persons with diabetes mellitus.9 For serum lipids, compared with male participants who had a lower high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol concentration, hearing levels at high frequencies were significantly better among male participants with a higher HDL cholesterol concentration.10 In relation to proteinuria, we previously examined a relationship between degree of dipstick proteinuria and prevalence of HI in another Japanese worker group and found that subjects with severe dipstick proteinuria had higher prevalence of HI compared with subject without proteinuria.11 A recent study in Australia reported that current smoking, obesity, high serum triglycerides and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity were positively associated with hearing loss in addition to diabetic condition and serum HDL cholesterol levels.12 Regarding hypertension, several epidemiological studies examined the association between hypertension and HI. However, the results of these studies were inconsistent.12–17 Cross-sectional studies reported a positive association between hypertension and HI in Korea and in Indian workers in the iron and steel industries.13 14 The same association was observed in a case-control study in Brazil, which also reported a positive association between hypertension and hearing loss.15 A preliminary study in Mexico reported that hypertensive participants exhibited HI in relation to an 8-kHz pure tone sound, compared with participants without hypertension.16 The Australian study mentioned above also reported that systolic and diastolic blood pressure level were positively associated with hearing thresholds of the best ear, especially for low frequency sounds.12 However, a cross-sectional study of Hispanic/Latino participants in the USA found no such association.17

Therefore, we aimed to examine the association between hypertension and HI in Japan. The prevalence of high blood pressure in Japan is equal to or higher than that in the UK and the USA.18 If hypertension is positively associated with HI, early intervention for hypertension may be beneficial for preventing HI. We hypothesised that hypertension would be positively associated with HI. To test this hypothesis, we conducted an association study among Japanese workers.

Methods

Participants

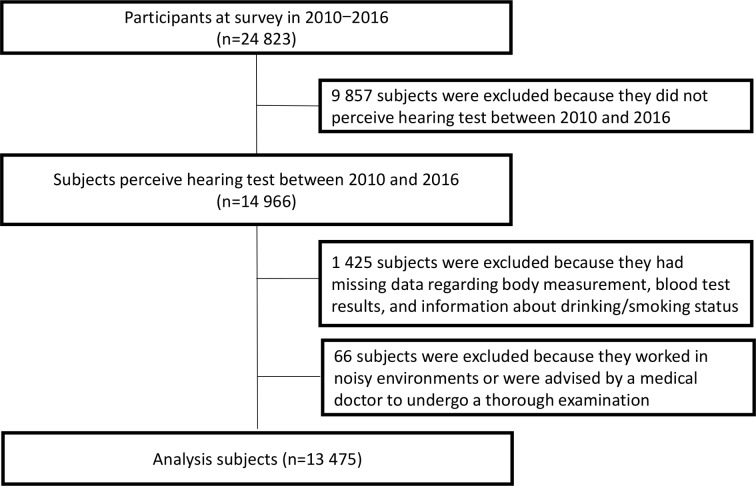

Participants were aged 18–81 years employees of Fujitsu Limited, an information and communication technologies company. We recruited a total of 24 823 participants (20 732 men and 4091 women) who underwent annual health check-ups between 2010 and 2016. For participants who had undergone annual health check-ups twice or more, we analysed the most recent data. We excluded 9857 participants who did not undergo hearing tests using audiometry from the analysis. In addition, we excluded 1425 participants who had missing data regarding body measurement, blood test results and information about drinking/smoking status. We also excluded 66 participants who worked in noisy environments or who were advised by a medical doctor to undergo a thorough examination, because they were presumed to be likely to exhibit a higher prevalence of HI. In Japan’s guideline, 85 dB is a value to be recognised as noisy work environment. Consequently, we included data from 13 475 participants (11 636 males and 1839 females) in the final analyses (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study subjects.

We used anonymised data with the permission of Fujitsu Limited.

Risk factor survey

The annual health check-up was conducted as required by the Industrial Safety and Health Act under Japanese law. The check-up consisted of body height and weight measurement with light clothing, ascertaining medical history including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, serum lipid abnormality, high serum uric acid and liver dysfunction, drinking/smoking status, a hearing test, a vision test, blood pressure measurement, blood test including serum lipids, hepatic enzymes, serum glucose, haemoglobin A1c, uric acid and blood count, and the dipstick urine test. Family history of illness such as cancer, stroke, coronary heart disease, hypertension and diabetes mellitus was ascertained. Participants had their blood pressure levels measured by automated sphygmomanometers on the arm. If the blood pressure level was high, the measurement was repeated. The hearing test was performed using audiometry. In accordance with Japanese law, two categories of hearing tests were applied at 1 and 4 kHz for each ear. Inability to respond to 30 dB at 1 kHz and/or 40 dB at 4 kHz was defined as the threshold for ‘abnormal’. In addition, 11 709 of 13 475 participants tested their hearing thresholds every 5 dB between −10 and 90 dB in 1 and 4 kHz, respectively. We calculated the mean hearing threshold as a mean of 1 and 4 kHz in both ears. For HbA1c, the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) value was used.

Definition of variables

We defined hypertension as ≥140 mm Hg systolic blood pressure and/or ≥90 mm Hg diastolic blood pressure and/or taking medication for hypertension. For HI, we defined a participant as having overall moderate HI (overall moderate HI), if there was an abnormal finding in any one category. Likewise, we defined moderate HI at 1 kHz (4 kHz) as an abnormal finding at 1 kHz (4 kHz). Also, we defined mean mild HI as a mean hearing threshold of >25 and ≤40 dB, and defined mean moderate to severe HI as a mean hearing threshold more than 40 dB.19 For other variables, we defined diabetes mellitus as ≥6.5% HbA1c and/or taking medication for diabetes mellitus, high serum cholesterol level as ≥220 mg/dL and/or taking medication for hypercholesterolaemia, and proteinuria as dipstick proteinuria 1+or more in a urine test. Body mass index (BMI) values were calculated as follows: weight in kilograms divided by height in metres squared.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the characteristics of participants according to the presence of hypertension. The characteristics included variables as age, sex, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, blood test, dipstick proteinuria, current smoking, current drinking, and medication for hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia and diabetes mellitus. Blood test included HbA1c level and serum lipid level. We calculated age and sex-adjusted prevalence of overall moderate HI and moderate HI at 1 and 4 kHz according to the presence of hypertension (model 1). In addition, we calculated the multivariable-adjusted prevalence of HI. We used confounding variables for adjustment, including age, sex, BMI (kg/m2), current drinker (yes or no), current smoker (yes or no), diabetes mellitus (yes or no), hypercholesterolaemia (yes or no) and proteinuria (yes or no) (model 2). We also examined the association between hypertension and mean mild or moderate to severe HI. We tested for sex interaction in each analysis and found no significant interactions.

We used SAS V.9.4 software for all analyses. P values <0.05 were regarded as statistically significant.

Patient and public involvement

The Ethics Committee of Dokkyo Medical University involved community views. Patients were not involved in the design or planning of the study.

Results

Among 13 475 participants in the current study, 980 (7.3%) exhibited overall moderate HI. A total of 441 participants (3.3%) exhibited moderate HI at 1 kHz, and 787 participants (5.8%) exhibited moderate HI at 4 kHz. A total of 248 participants (1.8%) exhibited HI at both 1 and 4 kHz. Among 11 709 participants in which the mean hearing threshold was calculated, 862 participants (7.4%) exhibited mean mild HI and 153 participants (1.3%) exhibited mean moderate to severe HI.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants according to the presence of hypertension. Compared with participants who did not have hypertension, participants with hypertension were older, with higher BMI values, higher blood pressure levels and higher HbA1c levels. In addition, hypertensive participants were more likely to be male, more likely to take medication for diabetes mellitus and hypercholesterolaemia, and less likely to have proteinuria.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects according to hypertension status

| Subjects without hypertension |

Subjects with hypertension |

P for difference |

|

| N | 10 437 | 3038 | |

| Age (years)* | 48.7±5.6 | 51.6±5.1 | <0.01 |

| Men (%) | 84.2 | 93.7 | <0.01 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2)†‡ | 23.2±0.0 | 25.7±0.1 | <0.01 |

| Systolic blood pressure (mm Hg)†‡ | 115.8±0.1 | 132.0±0.2 | <0.01 |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg)†‡ | 72.2±0.1 | 85.5±0.2 | <0.01 |

| Medication for hypertension (%) | – | 63.4 | – |

| HbA1c (%)†‡ | 5.6±0.0 | 5.8±0.0 | <0.01 |

| Medication for diabetes mellitus (%)† | 3.0 | 10.4 | <0.01 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL)†‡ | 207.0±0.3 | 205.4±0.6 | 0.03 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL)†‡ | 115.9±1.1 | 146.7±2.1 | <0.01 |

| Medication for dislipidaemia (%)† | 7.3 | 18.8 | <0.01 |

| Proteinuria (%)† | 3.6 | 2.7 | 0.02 |

| Current drinker (%)† | 74.9 | 78.3 | <0.01 |

| Current smoker (%)† | 22.0 | 20.3 | 0.06 |

| Total hearing impairment (%) | 6.2 | 10.9 | <0.01 |

| Hearing impairment in 1 kHz (%) | 2.7 | 5.2 | <0.01 |

| Hearing impairment in 4 kHz (%) | 5.0 | 8.7 | <0.01 |

*Means±SD.

†Age, sex-adjusted.

‡Means±SE.

Table 2 shows the prevalence of moderate HI according to the presence of hypertension. Compared with participants who did not have hypertension, participants with hypertension showed a higher prevalence of overall moderate HI and its subtypes. The prevalence of overall moderate HI among hypertensive participants was 8.7%, while that among participants who did not have hypertension was 6.9% (p values for difference <0.01). The prevalence rates of moderate HI at 1 and 4 kHz among hypertensive participants were 4.3% and 6.8%, respectively, while those among participants who did not have hypertension were 3.0% and 5.6% (p values for differences were <0.01 and 0.01).

Table 2.

Relationships between hypertension and hearing impairment

| Subjects without hypertension |

Subjects with hypertension |

P for difference |

|

| Total hearing impairment | |||

| N | 10 437 | 3038 | |

| Cases | 650 | 330 | |

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Model 1 (age, sex-adjusted) | 6.8% | 9.0% | <0.01 |

| Model 2 (multivariable-adjusted*) | 6.9% | 8.7% | <0.01 |

| Hearing impairment in 1 kHz | |||

| N | 10 437 | 3038 | |

| Cases | 284 | 157 | |

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Model 1 (age, sex-adjusted) | 2.9% | 4.5% | <0.01 |

| Model 2 (multivariable-adjusted*) | 3.0% | 4.3% | <0.01 |

| Hearing impairment in 4 kHz | |||

| N | 10 437 | 3038 | |

| Cases | 524 | 263 | |

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Model 1 (age, sex-adjusted) | 5.5% | 7.1% | <0.01 |

| Model 2 (multivariable-adjusted*) | 5.6% | 6.8% | 0.01 |

*Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, current drinking (yes or no), current smoking (yes or no), diabetes mellitus (yes or no), hyperlipidaemia (yes or no) and proteinuria (yes or no).

Table 3 shows the associations between hypertension and severity of HI, as mean mild HI and mean moderate to severe HI, among participants for whom the mean hearing threshold was calculated. After adjustment for confounding variables, the prevalence rates of mean mild HI and mean moderate to severe HI were 8.7% and 1.4% among participants with hypertension, while the prevalence rates were 7.0% and 1.3% among participants without hypertension (p values for difference were <0.01 and 0.50). In addition, we examined the association between severity of hypertension and severity of HI. However, there was no significant association between them.

Table 3.

Relationships between hypertension and hearing impairment according to mean values

| Subjects without hypertension |

Subjects with hypertension |

P for difference |

|

| Mean mild hearing impairment (mean hearing threshold >25 and ≤40 dB) | |||

| N | 9048 | 2661 | |

| Cases | 568 | 294 | |

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Model 1 (age, sex-adjusted) | 6.9% | 9.1% | <0.01 |

| Model 2 (multivariable-adjusted*) | 7.0% | 8.7% | <0.01 |

| Mean moderate to severe hearing impairment (mean hearing threshold >40 dB) | |||

| N | 9048 | 2661 | |

| Cases | 101 | 52 | |

| Prevalence (%) | |||

| Model 1 (age, sex-adjusted) | 1.2% | 1.6% | 0.14 |

| Model 2 (multivariable-adjusted*) | 1.3% | 1.4% | 0.50 |

*Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, current drinking (yes or no), current smoking (yes or no), diabetes mellitus (yes or no), hyperlipidaemia (yes or no) and proteinuria (yes or no).

We also examined the association between hypertension and HI according to the number of ears with overall moderate HI. Participants with hypertension showed significantly higher prevalence of bilateral overall moderate HI, but not unilateral overall moderate HI, compared with participants without hypertension. The prevalence rates of bilateral overall moderate HI were 3.2% for hypertensive participants and 2.2% for non-hypertensive participants (p value for the difference was <0.01), while those for unilateral overall moderate HI were 5.5% and 4.7%, respectively (p value for difference=0.09).

Discussion

The current study revealed that participants with hypertension exhibited significantly higher prevalence of HI in all ranges, at both 1 and 4 kHz, compared with participants without hypertension. In addition, participants with hypertension exhibited a higher prevalence of mean mild HI compared with participants without hypertension. However, no association was found between hypertension and mean moderate to severe HI.

A previous cross-sectional study in Korea revealed that hypertension was positively associated with the prevalence of HI.13 Compared with participants without hypertension, ORs and 95% CIs of participants with hypertension were 1.24 (1.10–1.42) for low/mid frequency mild HI, defined as an unaided pure tone hearing level for the superior ear of 26–40 dB in 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 kHz conditions, and 1.29 (1.16–1.45) for high frequency mild HI, defined in the same way in the 3.0, 4.0 and 6.0 kHz conditions. In addition, a previous study in Korea reported that ORs and 95% CIs of participants with hypertension were 1.19 (1.02–1.39) for low/mid frequency moderate-to-profound HI defined as an unaided pure tone hearing level for the superior ear of 41 dB or more in 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 kHz conditions, and 1.20 (1.07–1.35) for high frequency moderate-to-profound HI, defined in the same way in 3.0, 4.0 and 6.0 kHz conditions. In the present study, the results revealed that participants with hypertension had a higher prevalence of HI for both 1 and 4 kHz stimuli. We found a positive association between hypertension and the prevalence of mild HI. However, the association between hypertension and the prevalence of moderate to severe HI was not significant. We speculate that the smaller number of cases of moderate to severe HI, based on the lower proportion of older subjects, was likely to have caused the difference between the present study and the previous study in Korea. A cross-sectional study of Hispanic/Latino participants in the USA reported that the association between hypertension and total HI was not significant, whereas the association between hypertension and bilateral HI was significant.17 In the present study, participants with hypertension showed significantly higher prevalence of bilateral HI, but not unilateral HI.

Consideration of the difference between low frequency and high frequency HI in the current findings may be valuable. The present study and the previous study in Korea indicated that subjects with hypertension had higher prevalence of both lower and higher frequency HI, compared with subjects without hypertension.13 However, the study in Mexico reported an association between hypertension and higher hearing thresholds in 8 kHz, but not for lower frequencies.16 The study in Australia reported an association between hypertension and the best ear low-frequency average, but not the high-frequency average.12 Although the number of previous studies is limited, it is possible that a clear relationship between hypertension and HI exists in Asian populations.

The recent cross-sectional study in Australia revealed that Framingham risk scores were positively associated with both best ear low-frequency average and high-frequency average values.12 We also examined the association between Framingham risk score and prevalence of HI, and found that prevalence of total HI, HI in 1 kHz, HI in 4 kHz, mean mild HI and mean moderate to severe HI was significantly higher in the high-scoring group (5 or more points) compared with the low-scoring group (−15 to 1 point) (data not shown).

The mechanism underlying the association between hypertension and HI is uncertain, but our findings and those of previous studies imply that micro-vessel damage may lead to HI. Hypertension is one of the major risk factors of peripheral arterial disease.20–22 The inner ear depends on the supply of oxygen and nutrition in the labyrinthine artery. This artery is a thin branch of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery. Therefore, micro-vessel atherosclerosis caused by hypertension may be associated with a reduction in the level of oxygen and the nutrition supply for the inner ear. In a previous study using an animal model, organ blood flow was found to be lower in spontaneously hypertensive rats compared with normotensive rats.23 In addition, hypertension may be associated with brain damage. In the present study, the effect of hypertension on HI was clear for bilateral HI. We assumed that hypertension may damage not only the inner ear but also the primary auditory cortex.

The present study had several limitations that should be considered. First, the cross-sectional design of the present study did not allow us to establish a causal relationship. Second, we were unable to evaluate the association between hypertension and hearing thresholds other than 1 and 4 kHz, because this study was based on annual health check-ups, whose items were prescribed by Japanese law. In addition, we were unable to conduct a survey with unified measurement protocols, including the type of audiometer and automated sphygmomanometer, because the surveys were conducted in multiple centres over several years and the accuracy management of survey is left to each health check-up agency in Japan. Moreover, we were unable to evaluate the impact of family history of HI, because it was not included in the survey. Third, we were unable to evaluate the precise history of noise exposure because the data were anonymous and did not contain a precise history of noise exposure before 2010. Therefore, the present study design did not enable us to comprehensively evaluate the effects of noise exposure. In addition, we were unable to adjust for work-related factors because of anonymity. Finally, because the current study was based on the results of annual health check-ups in a single company which mainly consisted of male staff, the generalisability of the current findings is unclear.

The present study showed that hypertensive subjects had higher prevalence of HI. Even in clinical practice, by recognising the association stated above, it may be beneficial to detect subjects with HI at the early stage.

In conclusion, the current findings revealed that hypertension was positively associated with the prevalence of HI in Japanese workers. The association was evident for mild HI and bilateral HI. Further studies will be necessary to confirm this finding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Benjamin Knight, MSc, from Edanz Group (www.edanzediting.com/ac) for editing a draft of this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: MU and GK designed this study. MU and GK obtained the dataset. MU, TS, YH, MN and GK analysed the data. MU wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TS, YH, MN and GK commented on the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by JSPS Grant Number JP17K18051.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The study protocol of the present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Dokkyo Medical University (Univ-28018).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: We used data of annual health check-ups between 2010 and 2016 with the permission of Fujitsu Limited. We cannot share the data because of contract with Fujitsu Limited. The raw data of the present study is managed in the Department of Public Health, Dokkyo Medical University.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

References

- 1. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1545–602. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO. Fact sheets (15 March 2018), Deafness and hearing loss. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss (Accessed 26 Jan 2019).

- 3. Lin FR, Metter EJ, O’Brien RJ, et al. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol 2011;68:214–20. 10.1001/archneurol.2010.362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Davies HR, Cadar D, Herbert A, et al. Hearing impairment and incident dementia: findings from the english longitudinal study of ageing. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:2074–81. 10.1111/jgs.14986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deal JA, Betz J, Yaffe K, et al. Hearing impairment and incident dementia and cognitive decline in older adults: the Health ABC Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2017;72:703–9. 10.1093/gerona/glw069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Contrera KJ, Betz J, Genther DJ, et al. Association of hearing impairment and mortality in the national health and nutrition examination survey. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;141:1–946. 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.1762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li CM, Zhang X, Hoffman HJ, et al. Hearing impairment associated with depression in US adults, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005-2010. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014;140:293–302. 10.1001/jamaoto.2014.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, et al. Dementia prevention, intervention, and care. The Lancet 2017;390:2673–734. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Horikawa C, Kodama S, Tanaka S, et al. Diabetes and risk of hearing impairment in adults: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013;98:51–8. 10.1210/jc.2012-2119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Suzuki K, Kaneko M, Murai K. Influence of serum lipids on auditory function. Laryngoscope 2000;110:1736–8. 10.1097/00005537-200010000-00033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Umesawa M, Hara M, Sairenchi T, et al. Association between dipstick proteinuria and hearing impairment in health check-ups among Japanese workers: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e021427 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-021427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tan HE, Lan NSR, Knuiman MW, et al. Associations between cardiovascular disease and its risk factors with hearing loss-A cross-sectional analysis. Clin Otolaryngol 2018;43:172–81. 10.1111/coa.12936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hong JW, Jeon JH, Ku CR, et al. The prevalence and factors associated with hearing impairment in the Korean adults: the 2010-2012 Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (observational study). Medicine 2015;94:e611 10.1097/MD.0000000000000611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Narlawar UW, Surjuse BG, Thakre SS. Hypertension and hearing impairment in workers of iron and steel industry. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol 2006;50:60–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. de Moraes Marchiori LL, de Almeida Rego Filho E, Matsuo T. Hypertension as a factor associated with hearing loss. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol 2006;72:533–40. 10.1016/S1808-8694(15)31001-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Esparza CM, Jáuregui-Renaud K, Morelos CMC, et al. Systemic high blood pressure and inner ear dysfunction: a preliminary study. Clin Otolaryngol 2007;32:173–8. 10.1111/j.1365-2273.2007.01442.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cruickshanks KJ, Dhar S, Dinces E, et al. Hearing impairment prevalence and associated risk factors in the hispanic community health study/study of latinos. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2015;141:641–8. 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.0889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Mills KT, Bundy JD, Kelly TN, et al. Global disparities of hypertension prevalence and control: a systematic analysis of population-based studies from 90 countries. Circulation 2016;134:441–50. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.018912 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Alford RL, Arnos KS, Fox M, et al. American college of medical genetics and genomics guideline for the clinical evaluation and etiologic diagnosis of hearing loss. Genet Med 2014;16:347–55. 10.1038/gim.2014.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kitamura A, Iso H, Imano H, et al. Prevalence and correlates of carotid atherosclerosis among elderly Japanese men. Atherosclerosis 2004;172:353–9. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Matsunaga M, Yatsuya H, Iso H, et al. Similarities and differences between coronary heart disease and stroke in the associations with cardiovascular risk factors: The Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. Atherosclerosis 2017;261:124–30. 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Emdin CA, Anderson SG, Callender T, et al. Usual blood pressure, peripheral arterial disease, and vascular risk: cohort study of 4.2 million adults. BMJ 2015;351:h4865 10.1136/bmj.h4865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Sugiyama M, Ohashi K, Sasaki T, et al. The effect of blood pressure on inner ear blood flow. Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1984;239:197–203. 10.1007/BF00464244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.